Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Tat Transport Cannot Occur Through a Central Pore Generated by a TatB3C3 Complex

All Substrate-Binding Sites Can Be Equally Functional

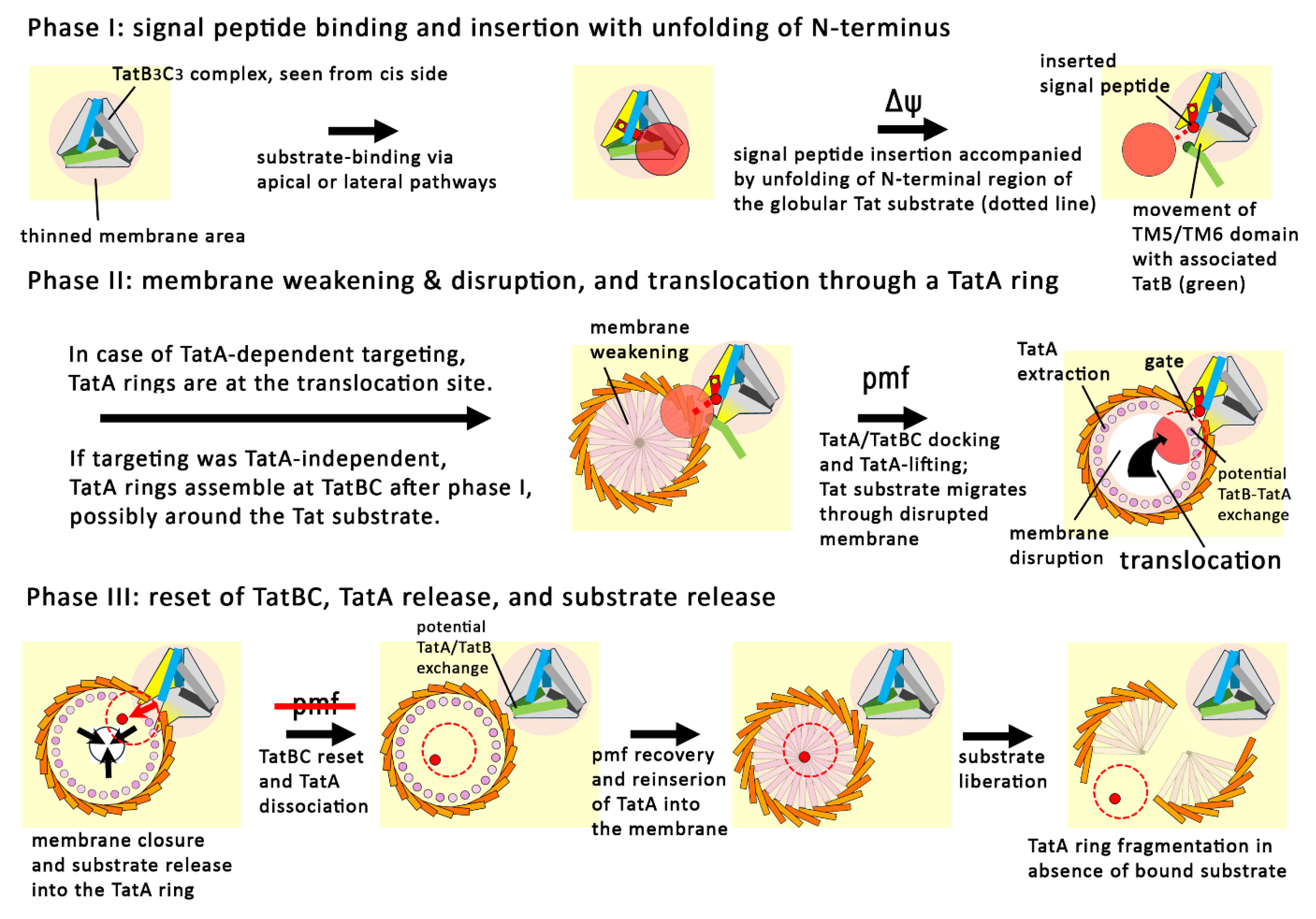

Phase I of Tat Transport: Signal Peptide Insertion by TatBC Complexes

Previously Unanswered Key Questions That Helped to Uncover the TatBC Complex Mechanism

- -

- How can TatC catalyze the insertion of signal peptides without transport of the mature domain, and why does TatB prevent this insertase activity, as observed by Fröbel et al. [33]?

- -

- If this insertase activity is important for the mechanism, how can the signal peptide insertion be catalyzed without liberating the twin-arginine motif from its initial binding site, as observed by Gerard et al. [34]?

- -

- How can signal peptide-binding to TatBC complexes alone already cause the association of TatA clusters, as observed by Dabney-Smith et al. [15]?

TatB N-Terminal Helices Block Access to the Signal Peptide h-Region-Binding Site in TatC

Biochemical and Structural Evidence for a Signal Peptide-Induced Domain Movement in TatBC

The Domain Movement Requires Membrane Energetization

Upon Signal Peptide Insertion, the Globular Domain Relocates to the Translocation Site

Phase II of Tat Transport: Docking of TatA, Membrane-Disruption and Directional Translocation

Previously Unanswered Key Questions That Helped to Understand TatA-Dependent Translocation:

- -

- -

- What are the structural characteristics of the ordered cluster of at least 16 TatA protomers that is generated at TatBC upon RR-dependent binding of the signal peptide to TatBC, as observed by Carole Dabney Smith et al. [15]?

- -

- -

- Why does substrate-interaction with TatA quantitatively protect a specific region of the TatA in a TatBC-dependent way, as shown by us [21]?

- -

- Why do large TatA assemblies diffuse either slowly, as expected for membrane-integral proteins, or rapidly, as expected for membrane-associated proteins without transmembrane helix, as shown by Yves Bollen et al. [54]?

- -

- What is the energy-demanding step in phase II of Tat transport [46]?

A Simple Pulling of the Folded Protein Through a Disordered TatA Assembly Cannot Explain Tat Transport

TatA Must form a More Defined Structure to Permit Tat Transport

TatA Forms Rings that Could Allow a Controlled TatBC-Dependent Membrane Perforation

AlphaFold 3 Predicts TatA Rings that Explain so Far Not Understood Findings

The Predicted TatA Rings Suggest a Membrane Disruption Mechanism That Is Experimentally Supported

The Membrane Disruption Mechanism Explains the TatBC Dependence and the 2nd Energy Requirement

Experimental Evidence for a Transient Lifting of TatA Rings onto the Membrane Surface

Priming of TatA Rings by Bound Substrate, and TatBC-Dependent Membrane Disruption by TatA

Phase III: Closing of the Catalytic Cycle and Resetting of the System

Release of the Signal Peptide Into the Membrane, and Reset of the TatBC Complex

Reset of the TatA Rings to Membrane-Inserted Clusters That Can Interact with Tat Substrates

The Tat System Requires a Functional Asymmetry

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Natale, P., Brüser, T., and Driessen, A. J. M. (2008) Sec- and Tat-mediated protein secretion across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane - distinct translocases and mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778, 1735–1756. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, M.-R., Tseng, Y.-H., Nguyen, E. H., Wu, L.-F., and Saier, M. H. (2002) Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of the twin-arginine targeting (Tat) protein export system. Arch Microbiol 177, 441–450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P. A., Buchanan, G., Stanley, N. R., Berks, B. C., and Palmer, T. (2002) Truncation analysis of TatA and TatB defines the minimal functional units required for protein translocation. J Bacteriol 184, 5871–5879. [CrossRef]

- Warren, G., Oates, J., Robinson, C., and Dixon, A. M. (2009) Contributions of the transmembrane domain and a key acidic motif to assembly and function of the TatA complex. J Mol Biol 388, 122–132.

- Barnett, J. P., Eijlander, R. T., Kuipers, O. P., and Robinson, C. (2008) A minimal Tat system from a gram-positive organism: a bifunctional TatA subunit participates in discrete TatAC and TatA complexes. J Biol Chem 283, 2534–2542. [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed, J. D., van der Ploeg, R., and van Dijl, J. M. (2006) Bifunctional TatA subunits in minimal Tat protein translocases. Trends Microbiol 14, 2–4. [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed, J. D. H., Grieger, U., Antelmann, H., Hecker, M., Nijland, R., Bron, S., and van Dijl, J. M. (2004) Two minimal Tat translocases in Bacillus. Mol Microbiol 54, 1319–1325. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z., and Sazanov, L. A. (2025) Structure of E. coli Twin-arginine translocase (Tat) complex with bound cargo. BioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Deme, J. C., Bryant, O. j., Batista, M., Stansfeld, P. J., Berks, B. C., and Lea, S. M. (2025) Structure and substrate recognition by the Twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway core complex. BioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Alami, M., Lüke, I., Deitermann, S., Eisner, G., Koch, H. G., Brunner, J., and Müller, M. (2003) Differential interactions between a twin-arginine signal peptide and its translocase in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell 12, 937–946. [CrossRef]

- Kreutzenbeck, P., Kroger, C., Lausberg, F., Blaudeck, N., Sprenger, G. A., and Freudl, R. (2007) Escherichia coli twin arginine (Tat) mutant translocases possessing relaxed signal peptide recognition specificities. J Biol Chem 282, 7903–7911. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lausberg, F., Fleckenstein, S., Kreutzenbeck, P., Frobel, J., Rose, P., Muller, M., and Freudl, R. (2012) Genetic evidence for a tight cooperation of TatB and TatC during productive recognition of twin-arginine (Tat) signal peptides in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 7, e39867. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X., and Cline, K. (2013) Mapping the signal peptide binding and oligomer contact sites of the core subunit of the pea twin arginine protein translocase. Plant Cell 25, 999–1015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauch, E. M., and Georgiou, G. (2007) Escherichia coli tatC mutations that suppress defective twin-arginine transporter signal peptides. J Mol Biol 374, 283–291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabney-Smith, C., and Cline, K. (2009) Clustering of C-terminal stromal domains of Tha4 homo-oligomers during translocation by the Tat protein transport system. Mol Biol Cell. [CrossRef]

- Lüke, I., Handford, J. I., Palmer, T., and Sargent, F. (2009) Proteolytic processing of Escherichia coli twin-arginine signal peptides by LepB. Arch Microbiol 191, 919–925. [CrossRef]

- Hatzixanthis, K., Palmer, T., and Sargent, F. (2003) A subset of bacterial inner membrane proteins integrated by the twin-arginine translocase. Mol Microbiol 49, 1377–1390.

- Goosens, V. J., Monteferrante, C. G., and van Dijl, J. M. (2014) Co-factor insertion and disulfide bond requirements for twin-arginine translocase-dependent export of the Bacillus subtilis Rieske protein QcrA. J Biol Chem 289, 13124–13131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A., Buchanan, G., and Palmer, T. (2014) Role of the twin arginine protein transport pathway in the assembly of the Streptomyces coelicolor cytochrome bc1 complex. J Bacteriol 196, 50–59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüser, T., and Sanders, C. (2003) An alternative model of the twin arginine translocation system. Microbiol Res 158, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B., Heidrich, E. S., Mehner-Breitfeld, D., and Brüser, T. (2018) The TatA component of the twin-arginine translocation system locally weakens the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli upon protein substrate binding. J Biol Chem 293, 7592–7605. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, A. H., and Theg, S. M. (2021) Electrochromic shift supports the membrane destabilization model of Tat-mediated transport and shows ion leakage during Sec transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeilage, R., Ganesan, I., Keilman, J., and Theg, S. M. (2023) Cell-penetrating peptides stimulate protein transport on the Twin-arginine translocation pathway: evidence for a membrane thinning and toroidal pore mechanism. BioRxiv 2023.07.08.548235. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F., Rouse, S. L., Tait, C. E., Harmer, J., Riso, A. de, Timmel, C. R., Sansom, M. S., Berks, B. C., and Schnell, J. R. (2013) Structural model for the protein-translocating element of the twin-arginine transport system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E1092-101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehner-Breitfeld, D., Ringel, M. T., Tichy, D. A., Endter, L. J., Stroh, K. S., Lünsdorf, H., Risselada, H. J., and Brüser, T. (2022) TatA and TatB generate a hydrophobic mismatch important for the function and assembly of the Tat translocon in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 298, 102236. [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, A., Mathers, J. E., Thomas, J. D., Barrett, C. M., and Robinson, C. (2001) TatB and TatC form a functional and structural unit of the twin-arginine translocase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 276, 20213–20219. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, J., and Brüser, T. (2014) The TatBC complex of the Tat protein translocase in Escherichia coli and its transition to the substrate-bound TatABC complex. Biochemistry 53, 2344–2354. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, C., Ma, X., Gerard, F., and Cline, K. (2014) Substrate-gated docking of pore subunit Tha4 in the TatC cavity initiates Tat translocase assembly. J Cell Biol 205, 51–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habersetzer, J., Moore, K., Cherry, J., Buchanan, G., Stansfeld, P. J., and Palmer, T. (2017) Substrate-triggered position switching of TatA and TatB during Tat transport in Escherichia coli. Open Biol 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, M.-H., Mehner-Breitfeld, D., and Brüser, T. (2024) A larger TatBC complex associates with TatA clusters for transport of folded proteins across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Sci Rep 14, 13754. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, C. M., Mangels, D., and Robinson, C. (2005) Mutations in subunits of the Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocase block function via differing effects on translocation activity or Tat complex structure. J Mol Biol 347, 453–463. [CrossRef]

- Celedon, J. M., and Cline, K. (2012) Stoichiometry for binding and transport by the twin arginine translocation system. J Cell Biol 197, 523–534. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröbel, J., Rose, P., Lausberg, F., Blümmel, A.-S., Freudl, R., and Müller, M. (2012) Transmembrane insertion of twin-arginine signal peptides is driven by TatC and regulated by TatB. Nat Commun 3, 1311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, F., and Cline, K. (2006) Efficient twin arginine translocation (Tat) Pathway transport of a precursor protein covalently anchored to its initial cpTatC binding site. J Biol Chem 281, 6130–6135. [CrossRef]

- Bageshwar, U. K., Whitaker, N., Liang, F. C., and Musser, S. M. (2009) Interconvertibility of lipid- and translocon-bound forms of the bacterial Tat precursor pre-SufI. Mol Microbiol 74, 209–226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, S., Abrol, R., Suloway, C. J. M., and Clemons, W. M. (2013) The glove-like structure of the conserved membrane protein TatC provides insight into signal sequence recognition in twin-arginine translocation. Structure 21, 777–788. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubert, J., Hou, B., Risselada, H. J., Mehner, D., Lünsdorf, H., Grubmüller, H., and Brüser, T. (2015) TatBC-independent TatA/Tat substrate interactions contribute to transport efficiency. PLoS ONE 10, e0119761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, C., Schlösser, A. S., Schiller, J., Bogdanov, M., and Brüser, T. (2017) Tat transport in Escherichia coli requires zwitterionic phosphatidylethanolamine but no specific negatively charged phospholipid. FEBS Lett 591, 2848–2858. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröbel, J., Rose, P., and Müller, M. (2011) Early contacts between substrate proteins and TatA translocase component in twin-arginine translocation. J Biol Chem 286, 43679–43689. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaudeck, N., Kreutzenbeck, P., Müller, M., Sprenger, G. A., and Freudl, R. (2005) Isolation and characterization of bifunctional Escherichia coli TatA mutant proteins that allow efficient Tat-dependent protein translocation in the absence of TatB. J Biol Chem 280, 3426–3432. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubert, J., and Brüser, T. (2014) Twin-arginine translocation-arresting protein regions contact TatA and TatB. Biol Chem 395, 827–836. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klösgen, R. B., Brock, I. W., Herrmann, R. G., and Robinson, C. (1992) Proton gradient-driven import of the 16 kDa oxygen-evolving complex protein as the full precursor protein by isolated thylakoids. Plant Mol Biol 18, 1031–1034. [CrossRef]

- Cline, K., Ettinger, W. F., and Theg, S. M. (1992) Protein-specific energy requirements for protein transport across or into thylakoid membranes. Two lumenal proteins are transported in the absence of ATP. J Biol Chem 267, 2688–2696. [PubMed]

- Braun, N. A., Davis, A. W., and Theg, S. M. (2007) The chloroplast Tat pathway utilizes the transmembrane electric potential as an energy source. Biophys J 93, 1993–1998. [CrossRef]

- Theg, S. M., Cline, K., Finazzi, G., and Wollman, F. A. (2005) The energetics of the chloroplast Tat protein transport pathway revisited. Trends Plant Sci 10, 153–154. [CrossRef]

- Bageshwar, U. K., and Musser, S. M. (2007) Two electrical potential-dependent steps are required for transport by the Escherichia coli Tat machinery. J Cell Biol 179, 87–99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, G., Leeuw, E., Stanley, N. R., Wexler, M., Berks, B. C., Sargent, F., and Palmer, T. (2002) Functional complexity of the twin-arginine translocase TatC component revealed by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 43, 1457–1470. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, C., Panahandeh, S., Jungkamp, A.-C., Moser, M., and Müller, M. (2010) TatB Functions as an Oligomeric Binding Site for Folded Tat Precursor Proteins. Mol Biol Cell 21, 4151–4161.

- Berghöfer, J., and Klösgen, R. B. (1999) Two distinct translocation intermediates can be distinguished during protein transport by the TAT (Dph) pathway across the thylakoid membrane. FEBS Lett 460, 328–332.

- Gerard, F., and Cline, K. (2007) The thylakoid proton gradient promotes an advanced stage of signal peptide binding deep within the Tat pathway receptor complex. J Biol Chem.

- Lindenstrauss, U., and Brüser, T. (2009) Tat transport of linker-containing proteins in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 295, 135–140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, K., and McCaffery, M. (2007) Evidence for a dynamic and transient pathway through the TAT protein transport machinery. EMBO J. 26, 3039–3049.

- Aldridge, C., Storm, A., Cline, K., and Dabney-Smith, C. (2012) The chloroplast twin arginine transport (Tat) component, Tha4, undergoes conformational changes leading to Tat protein transport. J Biol Chem 287, 34752–34763. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadarajan, A., Oswald, F., Lill, H., Peterman, E. J., and Bollen, Y. J. M. (2020) Rapid diffusion of large TatA complexes detected using single particle tracking microscopy. BioRxiv, 2020.05.14.095463. [CrossRef]

- Hao, B., Zhou, W., and Theg, S. M. (2022) Hydrophobic mismatch is a key factor in protein transport across lipid bilayer membranes via the Tat pathway. J Biol Chem 298, 101991. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, E., Jakob, M., and Klösgen, R. B. (2010) One signal is enough: Stepwise transport of two distinct passenger proteins by the Tat pathway across the thylakoid membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398, 438–443. [CrossRef]

- Dabney-Smith, C., Mori, H., and Cline, K. (2006) Oligomers of Tha4 organize at the thylakoid Tat translocase during protein transport. J Biol Chem 281, 5476–5483. [CrossRef]

- Gohlke, U., Pullan, L., McDevitt, C. A., Porcelli, I., Leeuw, E. de, Palmer, T., Saibil, H. R., and Berks, B. C. (2005) The TatA component of the twin-arginine protein transport system forms channel complexes of variable diameter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 10482–10486. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelmann, F., Mehner, D., Richter, S., Lindenstrauss, U., Lünsdorf, H., Hause, G., and Brüser, T. (2008) Recombinant expression of tatABC and tatAC results in the formation of interacting cytoplasmic TatA tubes in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 283, 25281–25289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jormakka, M., Törnroth, S., Byrne, B., and Iwata, S. (2002) Molecular basis of proton motive force generation: structure of formate dehydrogenase-N. Science 295, 1863–1868. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., Ronneberger, O., Willmore, L., Ballard, A. J., Bambrick, J., Bodenstein, S. W., Evans, D. A., Hung, C.-C., O'Neill, M., Reiman, D., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Wu, Z., Žemgulytė, A., Arvaniti, E., Beattie, C., Bertolli, O., Bridgland, A., Cherepanov, A., Congreve, M., Cowen-Rivers, A. I., Cowie, A., Figurnov, M., Fuchs, F. B., Gladman, H., Jain, R., Khan, Y. A., Low, C. M. R., Perlin, K., Potapenko, A., Savy, P., Singh, S., Stecula, A., Thillaisundaram, A., Tong, C., Yakneen, S., Zhong, E. D., Zielinski, M., Žídek, A., Bapst, V., Kohli, P., Jaderberg, M., Hassabis, D., and Jumper, J. M. (2024) Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, B., and Brüser, T. (2011) The Tat-dependent protein translocation pathway. Biomol Concepts 2, 507–523. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, M. G., Leeuw, E. de, Porcelli, I., Buchanan, G., Berks, B. C., and Palmer, T. (2003) The Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocase: conserved residues of TatA and TatB family components involved in protein transport. FEBS Lett 539, 61–67. [CrossRef]

- Walther, T. H., Grage, S. L., Roth, N., and Ulrich, A. S. (2010) Membrane alignment of the pore-forming component TatA(d) of the twin-arginine translocase from Bacillus subtilis resolved by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 132, 15945–15956. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwald, E. R., Steger, L. M. E., Vollmer, S., Gottselig, C., Grage, S. L., Bürck, J., Afonin, S., Fröbel, J., Blümmel, A.-S., Setzler, J., Wenzel, W., Walther, T. H., and Ulrich, A. S. (2022) Length matters: Functional flip of the short TatA transmembrane helix. Biophys J 122, 2125–2146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, S., Lindenstrauss, U., Lücke, C., Bayliss, R., and Brüser, T. (2007) Functional Tat transport of unstructured, small, hydrophilic proteins. J Biol Chem 282, 33257–33264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alder, N. N., and Theg, S. M. (2003) Energetics of protein transport across biological membranes. a study of the thylakoid ΔpH-dependent/cpTat pathway. Cell 112, 231–242. [CrossRef]

- Fincher, V., McCaffery, M., and Cline, K. (1998) Evidence for a loop mechanism of protein transport by the thylakoid ΔpH pathway. FEBS Lett 423, 66–70. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B., Frielingsdorf, S., and Klösgen, R. B. (2006) Unassisted membrane insertion as the initial step in ΔpH/Tat-dependent protein transport. J Mol Biol 355, 957–967. [CrossRef]

- Richter, S., and Brüser, T. (2005) Targeting of unfolded PhoA to the TAT translocon of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 280, 42723–42730. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cola, A., and Robinson, C. (2005) Large-scale translocation reversal within the thylakoid Tat system in vivo. J Cell Biol 171, 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, N., Bageshwar, U. K., and Musser, S. M. (2012) Kinetics of precursor interactions with the bacterial Tat translocase detected by real-time FRET. J Biol Chem 287, 11252–11260. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, F., Baker, M. A. B., Greene, N. P., Palmer, T., Wallace, M. I., and Berks, B. C. (2013) Live cell imaging shows reversible assembly of the TatA component of the twin-arginine protein transport system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E3650-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugham, A., Wong Fong Sang, H. W., Bollen, Y. J., and Lill, H. (2006) Membrane binding of twin arginine preproteins as an early step in translocation. Biochemistry 45, 2243–2249. [CrossRef]

- Pop, O. I., Westermann, M., Volkmer-Engert, R., Schulz, D., Lemke, C., Schreiber, S., Gerlach, R., Wetzker, R., and Müller, J. P. (2003) Sequence-specific binding of prePhoD to soluble TatAd indicates protein-mediated targeting of the Tat export in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem 278, 38428–38436. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S., Stengel, R., Westermann, M., Volkmer-Engert, R., Pop, O. I., and Müller, J. P. (2006) Affinity of TatCd for TatAd elucidates its receptor function in the Bacillus subtilis Tat translocase system. J Biol Chem 281, 19977–19984. [CrossRef]

- Keersmaeker, S. de, van Mellaert, L., Lammertyn, E., Vrancken, K., Anne, J., and Geukens, N. (2005) Functional analysis of TatA and TatB in Streptomyces lividans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 335, 973–982. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilks, K., Gimenez, M. I., and Pohlschröder, M. (2005) Genetic and biochemical analysis of the twin-arginine translocation pathway in halophilic archaea. J Bacteriol 187, 8104–8113. [CrossRef]

- Frielingsdorf, S., Jakob, M., and Klösgen, R. B. (2008) A stromal pool of TatA promotes Tat-dependent protein transport across the thylakoid membrane. J Biol Chem 283, 33838–33845. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, P., Patrick, J., Jakob, M., Jacobs, M., Klösgen, R. B., Wennmalm, S., and Mäler, L. (2021) Soluble TatA forms oligomers that interact with membranes: Structure and insertion studies of a versatile protein transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 183529. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keersmaeker, S. de, van Mellaert, L., Schaerlaekens, K., van Dessel, W., Vrancken, K., Lammertyn, E., Anne, J., and Geukens, N. (2005) Structural organization of the twin-arginine translocation system in Streptomyces lividans. FEBS Lett 579, 797–802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J. R., and Bolhuis, A. (2006) The tatC gene cluster is essential for viability in halophilic archaea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 256, 44–49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Meng, E. C., Pettersen, E. F., Couch, G. S., Morris, J. H., and Ferrin, T. E. (2018) UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci 27, 14–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).