Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Dementia and Diabetes

Dementia, Diabetes and Physical Activity (DDPA)

DDPA in Global Majority Groups

Rationale of this Narrative Review

Research Aim

Research Objective

Research Question

Methodological Approach: Meta-Narrative Review

- Planning: Defining the research scope and assembling a multidisciplinary team to guide the review.

- Searching: An iterative process of searching electronic databases. An initial strategy focused narrowly on the intersection of all three topics within Global Majority groups. However, due to the limited literature, the search was broadened to capture key research within each “storyline” separately, which could then be synthesised. Key search terms included combinations of (“dementia” OR “Alzheimer’s disease”), (“diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”), and (“physical inactivity” OR “sedentary behaviour”). Databases included CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, AMED, ASSIA, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Seminal works and grey literature (e.g., reports from public health bodies) were also included.

- Mapping: Identifying the key meta-narratives or research traditions apparent in the literature. For this review, these included: (a) the biomedical/epidemiological narrative, (b) the public health/preventive medicine narrative, (c) the health disparities/sociological narrative, (d) the behavioural science narrative, and (e) the intervention science narrative.

- Appraisal: Critically appraising the literature within each tradition, not to exclude studies based on a rigid quality hierarchy, but to understand the strengths, limitations, and underlying assumptions of each body of work.

- Synthesis: The core of the review, involving the construction of a coherent overarching narrative that explains the findings of the different traditions. This involved identifying points of convergence, explaining points of tension or conflict, and building a rich, integrated account of the topic.

- Recommendations: Drawing conclusions and formulating recommendations for policy, practice, and future research based on the synthesised narrative.

Results

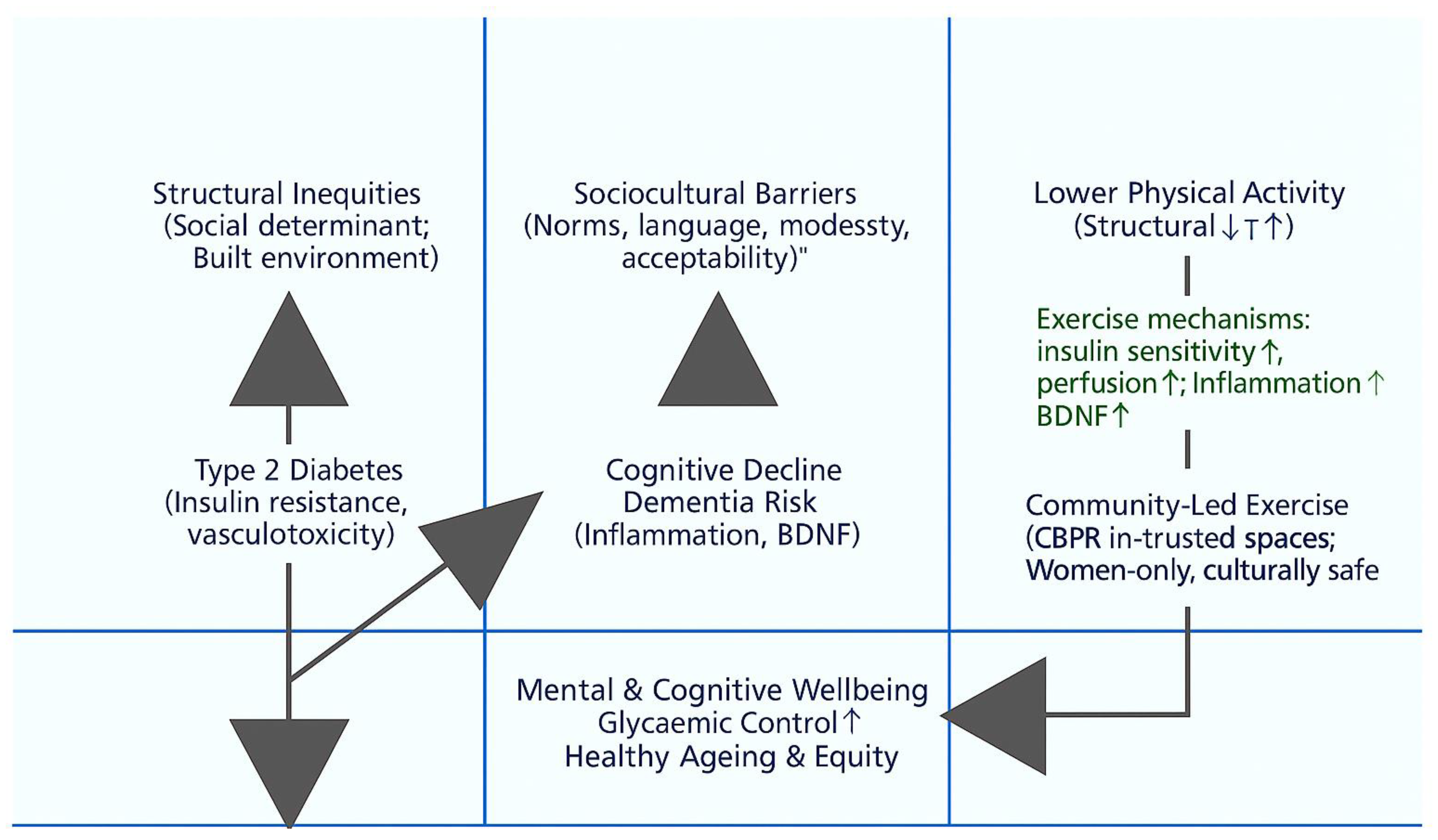

Meta-Narrative 1: The Biomedical and Epidemiological Narrative – A Triad of Risk

Meta-Narrative 2: The Public Health Narrative – Physical Inactivity as a Central, Modifiable Factor

Meta-Narrative 3: The Health Disparities Narrative – A Syndemic of Inequity

- Heightened Initial Risk: Populations of South Asian descent exhibit a unique biological susceptibility to T2D, developing the condition at a lower BMI and a younger age (Gujral et al., 2013).

- Amplified Behavioural Risk: This biological vulnerability is dangerously amplified by higher rates of physical inactivity. For example, a UK public health assessment in Walsall found that only 36% of Asian adults met PA guidelines, compared to 57% of their White British counterparts (Public Health Walsall, 2015). Furthermore, Safi et al. (2023) condcuted a cross-sectional study exploring the PA levels of British South Asian specifically focusing on youth from Afghan, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Indian groups and found that 88.5% Afghans, 80% Bangladeshi, 78.6% Indians and 63% Pakistani reported engaging in less than 30 minutes of PA per day. Furthermore, Safi et al. (2025A) condcuted a cross-sectional study exploring the sitting time of the same population and found that Afghan heritage had a median of sitting time of 150 minutes (MAD =222.390), Bangladeshi heritage 300 minutes (MAD =333.585), Indian heritage 465 minutes (MAD =229.803), and Pakistani heritage 390 minutes (MAD =400.302). While the group with Indian heritage had the highest median sitting time duration and Afghans the lowest. This aligns with previous findings suggesting lower activity levels among many Global Majority groups (Yates et al., 2010).

- Compounded Risk Post-Diagnosis: The disparity continues even after a diabetes diagnosis. A large, 10-year study of over 22,000 older adults with T2D found that, even after adjusting for numerous clinical and demographic factors, African Americans and Native Americans had a 40-60% higher risk of subsequently developing dementia compared to Asian Americans, who had the lowest risk (Whitmer et al., 2012). This reveals a compounded disadvantage, where the progression from one chronic disease to the next is itself shaped by factors linked to race and ethnicity.

- Exacerbated Future Burden: Projections indicate a dramatic future escalation of this disparity, with the number of people from ethnic minority communities in the UK living with dementia expected to increase seven-fold by 2051 (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia, 2013).

Meta-Narrative 4: The Sociocultural and Behavioural Narrative – Understanding Inaction

- Attitudes: Negative attitudes toward PA are often shaped by experiences of chronic pain, fatigue, and a perception that exercise is inappropriate or unsafe for older people (Horne & Tierney, 2012). Furthermore, Safi and Myers (2021) condcuted explored the barriers to PA of Afghans in the UK compared to those living in Afghanistan and found that Lack of time and being too tired were barriers for both populations but were rated higher by those living in Afghanistan as was a lack of confidence and being uncomfortable with exercise clothing.

- Subjective Norms: Powerful social and cultural pressures can discourage PA. For women, this may include expectations to prioritize domestic duties and caregiving roles over self-care. For both men and women, community norms around food and hospitality can conflict with healthy lifestyle advice (Begum et al., 2009; Horne & Tierney, 2012).

-

Perceived Behavioural Control: This is arguably the most significant area of barriers. For instance, Safi and Myers (2021) found that Afghan females perceived a lack of single-sex facilities, not being able to participate in PA with males, and having to be fully covered outside of the home as important barriers to their PA, but these were more of a barrier for those residing in the UK compared to those in Afghanistan. Furthermore, some other barriers include:

- Systemic Barriers: Lack of access to safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate facilities (e.g., women-only gym sessions, prayer facilities).

- Environmental Barriers: Living in deprived areas with poorly maintained green spaces or concerns about personal safety.

- Communication Barriers: Language barriers with healthcare providers, leading to a poor understanding of health advice (Yeowell, 2010).

- Cultural Barriers: A sense of fatalism or the belief that health outcomes are predetermined (“in God’s hands”), reducing self-efficacy. Stigma surrounding dementia can also prevent families from seeking help or engaging with preventive health services (Alzheimer’s Society, 2023; Hossain & Khan, 2019).

Meta-Narrative 5: The Intervention Science Narrative – Pathways to Equity

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Research Implications and Recommendations for Future Study

- Implication: Future research on health interventions in Global Majority communities should be built on a CBPR framework. This involves equitably involving community members, leaders, and organizations in all phases of the research process, from defining the research question to designing the intervention and disseminating the findings (Shalowitz et al., 2009). This approach shifts power dynamics, builds trust, and ensures that interventions are grounded in the lived reality of the community.

- Recommendation: Funding bodies should create specific grant streams for CBPR projects and require evidence of genuine community partnership in applications for funding aimed at reducing health disparities. Research institutions should invest in training and supporting researchers to develop the skills needed for effective community engagement, moving beyond tokenistic consultation to true co-creation.

- Implication: The success of the pilot mosque-based programme (Banerjee et al., 2016) provides a model that should be adapted and expanded. Interventions need to be brought to where people are, both physically and culturally.

- Recommendation: Public health commissioners should work with community organizations to co-design and fund a diverse portfolio of PA programmes delivered in trusted community settings, such as gurdwaras, temples, churches, and community centres. These programmes should be tailored to address specific cultural needs, such as providing women-only sessions, ensuring modesty, incorporating culturally familiar activities (e.g., dance), and being sensitive to religious calendars and obligations. Employing “community health champions” or “cultural brokers” from within the community can further enhance trust and engagement.

- Implication: The trust placed in GPs (Horne et al., 2012) represents a powerful opportunity. However, this trust can be eroded if patients feel their cultural context is not understood or respected.

- Recommendation: Medical and nursing school curricula, as well as continuing professional development programmes, must include mandatory training on cultural competency. This should go beyond superficial awareness to provide practical skills in: (a) understanding the syndemic of risk in diverse populations; (b) using tools like the Theory of Planned Behaviour to sensitively inquire about sociocultural barriers to health behaviours; and (c) “social prescribing,” where clinicians can connect patients to specific, culturally appropriate community-based programmes and resources. Health systems must also ensure adequate access to interpreters and support for longer consultation times when needed.

- Implication: The high rates of physical inactivity in many Global Majority communities are linked to the socioeconomic and environmental conditions of the areas where they are more likely to live.

- Recommendation: Public health leaders must advocate for policies that address the social determinants of health. This includes equitable investment in safe, well-lit, and well-maintained public parks and green spaces in deprived neighbourhoods; policies that promote active transport (walking and cycling); and ensuring that new housing developments include accessible recreational facilities. This shifts the focus from solely blaming individuals for their inactivity to creating environments where the healthy choice is the easy choice for everyone.

- Recommendation:

- Conduct large-scale, longitudinal cohort studies within specific UK-based Global Majority populations to more accurately quantify the population-attributable fraction of dementia risk from factors like diabetes and physical inactivity.

- Expand qualitative research beyond the South Asian community to better understand the unique barriers and facilitators to physical activity among Black African, African Caribbean, Eastern European, and other diverse groups.

- Conduct implementation science research to understand the best strategies for scaling up successful pilot interventions (like the mosque-based programme) to a regional or national level, while maintaining fidelity and community engagement.

- Develop and validate culturally-adapted assessment tools for dementia and cognitive decline, as existing tools may not be appropriate for linguistically and culturally diverse populations, leading to under-diagnosis.

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 1991, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia. Dementia does not discriminate: The experiences of black, Asian and minority ethnic communities; The Alzheimer’s Society, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19(4), 1598–1695. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society. Left to Cope Alone: The unmet support needs of people with dementia from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Annear, M. J.; Toye, C.; McInerney, F. What should we be recommending to older people in relation to the prevention of dementia? A narrative synthesis of the evidence from international guidelines. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2015, 15(7), 811–819. [Google Scholar]

- Ashra, N. B.; Spong, R.; Carter, P.; Gujral, J. S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of a real-world lifestyle intervention programme for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open 2015, 5(9), e007174. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R. R. Promoting physical activity and nutrition in people with stroke. Stroke 2020, 51(2), 691–693. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A. T.; Kin, C.; Strachan, P. H.; Boyle, M. H. A mosque-based physical activity intervention for South Asian Muslim women: a pilot and feasibility study. Women’s Health 2016, 12(4), 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, S.; Williams, J.; Adamson, A. J. ‘I want to be a little bit lighter but I don’t want to be skinny’: a qualitative study of the diet and physical activity views and preferences of Bangladeshi women living in Newcastle upon Tyne. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2009, 22(6), 529–537. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, S.; Brixius, K.; Brinkmann, C. “Physical exercise and dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”. Authors’ reply. Endocrine 2016, 54, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N. H.; Shaw, J. E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J. D.; Ohlrogge, A. W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2018, 54, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J. H.; Vinberg, M.; Fotopoulou, A. The impact of type 2 diabetes on the risk of dementia. Diabetologia 2007, 50(7), 1364–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Australia. Physical activity; Retrieved from Dementia Australia website; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O.; Peacock, R. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: a meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social science & medicine 2005, 61(2), 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Gronek, P.; Balko, S.; Gronek, J.; Zajac, A.; Maszczyk, A.; Celka, R.; Yu, F. Physical activity and Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Aging and disease 2019, 10(6), 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujral, U. P.; Pradeepa, R.; Weber, M. B.; Narayan, K. M.; Mohan, V. Type 2 diabetes in South Asians: similarities and differences with white Caucasian and other populations. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2013, 1281(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J. The double dilemma: the rising prevalence of diabetes and dementia. British Journal of Community Nursing 2019, 24(12), 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, M.; Tierney, S. What are the barriers and facilitators to exercise and physical activity uptake and adherence among South Asian older adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Preventive medicine 2012, 55(4), 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Z.; Khan, H. T. A. Dementia in the Bangladeshi diaspora in England: A qualitative study of the myths and stigmas about dementia. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 2019.

- Johnson, A. Risk of type 2 diabetes for people from Black African, African Caribbean and South Asian backgrounds; Diabetes UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M. R.; Perales-Puchalt, J. Applying a syndemic framework to understand and address health disparities. JAMA 2023, 329(17), 1455–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Lascar, N.; Brown, J.; Pattison, H.; Barnett, A. H.; Bailey, C. J.; Bellary, S. Type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2018, 6(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneilly, G. S.; Tessier, D.; Knip, A. Diabetes in elderly adults. The Lancet 2016, 387(10028), 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, S.; Matthews, F. E.; Barnes, D. E.; Yaffe, K.; Brayne, C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. The Lancet Neurology 2014, 13(8), 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing, Times. Life expectancy rises but years in good health falls; Retrieved from Nursing Times website; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Piras, A.; Raffi, M. A narrative literature review on the role of exercise training in managing type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Healthcare 2023, 11(22), 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsall, Public Health. Healthy Weight and Physical Activity Needs Assessment; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, A.; Hossain, M.; Myers, T. Faith, health and well-being: a qualitative study exploring Islamic perspectives on physical activity and the role of Imams (scholars). Discover Social Science and Health 2025, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalowitz, M. U.; Isacco, A.; Barquin, N.; Clark-Kauffman, E.; Delger, P.; Nelson, D.; Wagenaar, K. Community-based participatory research: a review of the literature with strategies for community engagement. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP 2009, 30(4), 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Physical inactivity in Black and Asian people; Public Health England, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.; Liolitsa, D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, cognitive impairment and dementia. Diabetic Medicine 1999, 16(2), 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmer, R. A.; Karter, A. J.; Yaffe, K.; Quesenberry, C. P., Jr.; Selby, J. V. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2009, 301(15), 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Physical Inactivity; World Health Organisation, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and health; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, T.; Davies, M. J.; Khunti, K. Physical activity and ethnic minorities. Postgraduate medical journal 2010, 86(1011), 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yeowell, G. The health-care experiences of British-Pakistani women with osteo-arthritis of the knee. Disability and rehabilitation 2010, 32(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).