1. Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is a holistic approach designed to improve the quality of life of patients and their families who face health challenges associated with life-threatening illnesses. It focuses on the prevention and alleviation of suffering through addressing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs. [

1]. While initially developed for patients with terminal cancer, the principles and applications of PC have expanded to encompass a broader range of chronic and life-threatening conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), heart failure, and other progressive illnesses [

2,

3,

4]. Such populations are commonly described in the literature as patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions [

5,

6,

7].

Globally, the need for PC has increased significantly: it is now estimated that approximately 73.5 million people experience severe health-related suffering that could be alleviated with adequate care [

8]. Despite this increase, actual coverage of needs remains limited — only about 14% of people who need PC receive such services [

9]. It is important to note that the majority of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions require PC, as these diseases account for more than half of the total population in need of PC worldwide [

1]. Although advanced non-malignant chronic conditions may affect adults across the lifespan, the burden of disease and the need for PC are disproportionately concentrated among older adults. Population ageing, multimorbidity, and functional decline have been consistently identified as key drivers of PC demand, resulting in substantially higher needs among elderly populations compared to younger adults [

1,

6]. Moreover, in contrast to cancer populations—where PC services are more systematically integrated—older adults with non-malignant chronic conditions remain significantly underserved [

3,

6,

7].

At the same time, younger patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions (e.g., neurological or end-stage organ diseases) often experience prolonged and unpredictable disease trajectories accompanied by considerable symptom burden, yet are less likely to be referred to specialist PC services [

5,

6].The demographic shift toward an aging population and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases have significantly amplified the demand for PC services. By 2040, it is projected that deaths from chronic illnesses will rise dramatically, particularly among older age groups, further underscoring the critical need for integrated age-sensitive, and diagnosis-inclusive PC services for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions [

10].

According to recent comparative evidence reported by Alnajar et al. [

11] PC services remain largely structured around cancer populations and oncology-driven referral pathways, and therefore often fail to adequately address the unique, heterogeneous, and prolonged needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. Studies indicate that patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions experience similar burdens of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual symptoms as patients with cancer, but are significantly less likely to access PC services [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, particularly those with cardiopulmonary failure, are at higher risk of intensive care hospitalizations and receiving life-sustaining treatments compared to patients with cancer [

15,

16,

17]. This discrepancy stems from limited awareness and understanding of the PC needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions among healthcare providers and systems [

3].

Despite the recognition of these disparities, much of the existing literature has focused primarily on the physical aspects of care, neglecting a comprehensive, integrated understanding of the multidimensional needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions [

18,

19,

20]. Given the diverse trajectories and symptom burdens experienced by patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, it is essential to develop tailored PC models that holistically address their unique challenges and improve their quality of life [

17,

21].

Caregivers play a pivotal role in PC, particularly for patients with chronic illnesses who require long-term support at home. Caregivers are responsible for a wide array of tasks, including monitoring treatment, managing symptoms, and providing emotional, financial, and spiritual support [

22]. However, caregiving responsibilities can impose significant physical, psychological, and social burdens, often exacerbated by insufficient preparation and limited access to resources [

23]. Studies have highlighted that caregivers frequently feel unprepared to fulfill their roles, lacking adequate knowledge about the disease, caregiving techniques, and available resources [

24,

25]. This lack of preparedness not only compromises the quality of care provided to patients but also negatively affects caregivers’ well-being, leading to stress, fatigue, and deterioration in their physical and mental health [

24,

26]. Addressing these challenges through targeted education, support systems, and healthcare integration is critical to enhancing caregiver readiness and reducing their care burden.

PC in Greece, remains underdeveloped compared to other high-income European Union countries. Although a relevant legislative framework was established with the enactment of the 2022 law on palliative care and the subsequent establishment of a National Palliative Care Committee by ministerial decision in 2023, service provision has not yet translated into substantial expansion in practice [

27]. Currently, only three specialized PC programs continue to operate nationwide, serving approximately 600 patients annually. Additionally, some general PC services are provided through oncology and pain clinics in hospitals. However, the estimated need for PC in Greece far exceeds the available resources, with approximately 120,000 to 135,000 patients and their families requiring support each year [

27]. The majority of patients requiring PC in Greece are patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions (63%), with conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, COPD, diabetes, kidney disease, and dementias accounting for a significant portion of the demand. Despite the preference of many patients to receive care and die at home—a setting associated with better quality of life—the lack of sufficient home care teams and inpatient facilities poses substantial challenges to meeting this need [

27].

Despite these systemic limitations, both patients and caregivers often demonstrate remarkable psychological endurance and adaptive capacities in managing the challenges of advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. Their ability to draw strength from family bonds, faith, and community ties represents a crucial — yet underexplored — aspect of PC experiences. Recognizing and understanding these sources of resilience and support is essential, not only to address unmet needs but also to reinforce the existing coping mechanisms that sustain patients and families in the community [

21,

28,

29].

To bridge this gap, it is essential to prioritize the development of community-based PC services, particularly those tailored to the needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers. Such services should emphasize early integration of PC into the disease trajectory, enabling better symptom management, improved quality of life, and reduced healthcare utilization. [

28,

29,

30]. Given the substantial unmet needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and the significant burden on their caregivers, this study aims to explore patients’ PC needs from a qualitative perspective. By examining the experiences and challenges of both patients and caregivers, this study seeks to:

Identify the specific physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions.

Explore caregivers’ preparedness and support requirements in their role as providers of care, as these relate to the identification and management of patients’ PC needs.

Inform the development of tailored PC models that address the unique characteristics of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers.

Furthermore, by investigating their needs, we hope to generate valuable insights that can be used later to develop a new tool to assess the needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions in PC services. This tool will be accessible and usable by all stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. By addressing these objectives, this study hopes to contribute to the growing body of evidence advocating for equitable and holistic PC services for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their families.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection and Study Procedures

Sampling Strategy

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit information-rich cases relevant to the study aims. Specifically, maximum variation purposive sampling was used to capture a heterogeneous range of experiences across key characteristics, including age, type of advanced non-malignant chronic condition, functional status, and caregiving context.

Participants were recruited from two groups: patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers. Recruitment and eligibility criteria were designed to ensure the inclusion of participants able to provide rich and meaningful qualitative data rather than statistical representativeness. The eligibility criteria for both groups are summarized in

Table 1. Patients with neurological diseases (e.g., ALS, MS) were eligible for inclusion, provided their communication abilities were sufficiently preserved to allow participation in in-depth interviews. Patients with neurological or psychiatric conditions were excluded only when communication impairments prevented meaningful contribution to the interview process.

Through the “Help at Home” program of the Municipality of Katerini, sponsored by the Department of Social Policy and Public Health, Division of Elderly Care, participants were recruited. The staff assisted in identifying and establishing the primary contact for eligible people. Prospective participants were provided with written and verbal information on the goals, procedures, and requirements of the study. A standard screening procedure was adopted to ascertain adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in advance. The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics and Bioethics Committee of the International Hellenic University (Approval Ref. No. 18/22.12.2022). In addition, permission to recruit participants through the “Help at Home” program was granted by the Municipality of Katerini, Department of Social Policy and Public Health (Approval Ref. No. [7803/30.01.2025]). Both approvals were obtained before data collection commenced. Recruitment and data collection were conducted between January and March 2025.

All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study. Data were gathered through qualitative interviews to ascertain the physical, emotional, and social aspects of PC needs. The interviews took place at the patients’ homes to accommodate individual needs and preferences. Given the possibility that a few participants might experience mobility issues, great care was taken to ensure their full participation without the added burden of travel. Being interviewed in their usual environment might have been very comforting and reassuring to participants, allowing them to relax and open up for genuine responses. At the same time, the home atmosphere enabled participants to express themselves endearingly, as they could easily relate their expressions to their day-to-day lives and culture, adding depth and relevance to the data being collected. The design of the study maintained an accessible and inclusive spirit to obtain a sample representative of diverse social, age, and health profiles. With this approach, the study endeavored to comprehensively capture the PC needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers. Communication ability was assessed during the screening process by the research team in collaboration with ‘Help at Home’ staff, ensuring that participants could engage with open-ended interview questions.

2.2. Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative interviews in a semi-structured format were conducted with a sample group of individuals who met the eligibility criteria. Study participants comprised patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their primary informal caregivers admitted to the “Help at Home” program of the Municipality of Katerini. The recruitment and enrollment process was conducted between January and March 2025; of the 15 patients and 16 caregivers approached, eight patients and nine caregivers provided consent to participate. Reasons provided by people who refused to be interviewed were poor health prognosis (physical/emotional) (5), lack of interest or time (4), or inability to agree on a convenient time due to logistical or family constraints (5). Purposive sampling ensured variation in participants’ caregiving experience, types of chronic illness, and levels of support needed. The objective was to encompass multiple perspectives, including older and younger populations, men and women, and those from urban and rural areas of Katerini. The recruitment process was completed when thematic saturation was observed, as no new codes or themes emerged in the last two interviews. Considering the relatively focused research question, the homogeneity of the participants, and the richness of the data collected, the sample size was deemed adequate according to the principle of “information power” [

31].

The principal investigator (CK) interviewed participants in their homes to create a comfortable, familiar environment conducive to open discussion. All interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (CK), who has prior training in qualitative research methods and experience in the care of patients with chronic illnesses. The interviewer had no prior professional or personal relationship with the study participants, thereby minimizing the risk of role conflict or biased responses. Reflexive field notes were kept after each interview to acknowledge and bracket potential preconceptions. In addition, continuous dialogue with a second senior researcher (TB) was used to enhance critical reflection and reduce interviewer bias. The interviews varied in duration from 40 to 85 minutes. Field notes were taken immediately after each session to record nonverbal behavior, contextual details, and emerging analytical thoughts. The interview guides for patients and caregivers were developed collaboratively by the research team before ethical approval. The interview guides contain open-ended questions addressing several domains: physical symptoms and impact of the disease, psychological distress, social limitations, spiritual concerns, and unmet needs in the healthcare and support services. Central emphasis was on the perceived adequacy of current home-care services, how these services may be improved, and on perceived essential interdisciplinary roles that currently do not exist (e.g., physiotherapist, psychologist, counselor).

Patients were invited to describe the evolution of their symptoms and support needs, the day-to-day challenges they encounter, and broader thoughts on quality of life related to having a chronic illness. Caregivers were asked to reflect on the needs of the patients they care for, as these are experienced and managed in everyday caregiving, including patients’ physical, psychological, social, and practical needs. In addition, caregivers were invited to discuss their caregiving responsibilities, emotional strain, and perceived support from formal services, insofar as these factors influenced their ability to recognize and respond to patients’ PC needs. The interview guide was developed as a skeleton to allow flexibility during data collection; however, it was iteratively modified as new themes emerged [

32].

In addition to exploring unmet needs, the interview framework also encouraged participants (patients and caregivers) to reflect on how they cope with daily challenges and where they draw emotional or practical strength. This approach was grounded in the holistic philosophy of PC, aiming to capture not only suffering but also the adaptive resources, such as family ties, spirituality, and community support, that enable patients and caregivers to endure and find meaning in the illness experience [

21,

28,

29].

2.3. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was the most suited approach to analyzing the qualitative data in the present study because the method maintains a theoretical flexibility while providing a structured approach to identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns themes within qualitative data [

32]. Whereas grounded theory is employed to develop formal theoretical models, thematic analysis is particularly geared towards investigations such as our own, which are meant to examine participant experiences and perspectives in specified health and care contexts [

33,

34]. Our objective was to provide finer detail and deeper insight into the physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and care-related needs of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers.

The interviews were all audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the principal investigator, with the original data anonymized. To further protect confidentiality, the presentation order of patients and caregivers in the Supplementary material is for reporting purposes only and does not indicate fixed dyadic linkage; this approach was adopted to prevent any potential identification of participants or inference of relationships between individuals. The transcriptions were read several times to gain deep familiarity with the data. Two trained researchers would independently perform a thematic analysis of the data by following Braun and Clarke’s [

32] structured multi-step procedure:

Familiarising with data: Researchers read and re-read every single transcript, writing down some initial ad hoc remarks in the margins about points of potential interest.

Generating initial codes: Open coding was used regarding the transcript, aiming at labeling meaningful features of the data. The code generation was inductive and, where possible, the participants’ very language was used.

Searching for themes: Codes were combined into a few broader categories, which were found to be similar in their subject matter and relevant to their conceptual implementation. These were then grouped under umbrella themes.

Reviewing themes: The potential themes were tested against all the data for credibility and, in doing so, their boundaries were either entrenched or made more explicit.

Defining and naming themes: Themes were defined and named, supported by representative quotations extracted from the transcripts, including, where relevant, cross-cutting patterns of resilience and sources of support that emerged inductively from the data.

Producing the report: The report was written based on these finalized themes focused on interviewees’ experiences, namely, the commonalities and diversities among experiential accounts of participants.

While performing analysis, constant iteration allowed for new insights to be incorporated into the unfolding analysis, along with continuous ongoing comparisons across and among interviews to verify internal coherence and thematic integrity [

35]. They ensured accuracy through triangulation, since the data were analyzed independently and cross-validated by two members of the research team. Differences in coding or interpretation were discussed until both reached consensus on a single interpretation. The two researchers who undertook the coding had different but complementary scientific backgrounds. The first (CK), a member of the Department of Elderly Care of the Directorate of Social Policy and Public Health of the Municipality of Katerini, has clinical experience in the care of chronically ill patients and specializes in the psychological dimensions of healthcare. The second (TB), a professor with research and teaching experience in qualitative and mixed-methods research and in the quality of life of patients with chronic or life-threatening diseases, contributed to the research process through methodological and theoretical guidance. In instances where the two primary coders were unable to reach consensus through discussion, two additional senior researchers were available to ensure methodological triangulation and adjudication. Specifically, CP (Assistant Professor in Clinical Psychology with expertise in qualitative methodology) and EM (Professor of Nursing with expertise in the quality of life of older adults) could be consulted to provide an independent perspective on contested codes. Their involvement was planned solely for cases in which consensus could not be achieved between the primary coders. Coding was performed using NVivo 14, which facilitated data organization and theme development. The analysis followed an inductive approach, without a predetermined theoretical framework, with an emphasis on semantic themes, although elements of latent meaning were also identified in some narratives. For transparency, a sample of the codebook (6–8 main codes with definitions and indicative excerpts) is provided as Supplementary Material (

Table S1).

Given the interpretive nature of thematic analysis, much consideration was given to retaining each participant’s authentic voice while also seeking common ground across the interviews. Researchers remained mindful of the difficulty introduced by converging individual stories into broader themes, an issue frequently referenced in the literature [

32].To diminish interpretive bias, the findings present examples of outliers and contradictory ones where suitable. The final thematic structure was derived through a rigorous, systematic, and transparent analysis. Each step of the data analysis was conducted according to well-established qualitative research practices [

33,

36] To achieve analytic depth, validity, and interpretive clarity. The analysis was conducted in Greek, the language of the interviews, to preserve cultural and linguistic authenticity. Any part of a quotation presented during the results section was translated into English with close attention to the meaning and context.

Translation process: All interviews were conducted and transcribed in Greek. The quotations included in this paper were translated into English by the principal investigator, who is fluent in both languages and has research experience in qualitative methods. To ensure accuracy, the translated excerpts were reviewed by a second bilingual researcher (TB), and minor adjustments were made to preserve cultural and contextual meaning. Although no formal back-translation procedure was performed, careful comparison of the original transcripts and the translated excerpts was undertaken to safeguard fidelity. For transparency, a selection of original Greek quotations is provided in the Supplementary Material (

Table S2).

3. Results

Table 2 depicts the demographic and clinical features of the sample. The study sample includes eight patients and nine caregivers. The median age of patients is 87 years, with a range of 53 to 92 years, whereas caregivers are comparatively younger, with a median age of 64 and a range of 49 to 84. Clearly, the majority of the patients are women (87.5%), whereas there seems to be an almost equal distribution between males (44.4%) and females (55.6%) among the caregivers. When considering marital status, most of the patients are widowed (62.5%), whereas most of the caregivers are married or cohabitating with a common-law partner (66.7%). When looking at parenthood, more are in the category of patients with three or more children (62.5%), while caregivers are less clear-cut, with 44.4% also having three or more children. Regarding educational level, 100% of both groups report a level below high school. Most patients are retired (87.5%), while caregivers are mostly retired as well (55.6%); others work (22.2%) or are unemployed (11.1%).

Regarding annual household income, most patients earn between €10,000 and €19,999 (50%), while caregivers are split evenly between less than €10,000-€19,999 (44.4%) and €20,000-€29,999 (44.4%). The most prevalent chronic conditions for patients include heart failure (62.5%), neurological disease such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease (50%), and diabetes mellitus (37.5%). Caregivers’ relationships with patients are primarily with other family members (55.6%), followed by spouses/partners (22.2%) and sons/daughters (22.2%). Regarding years of caregiving experience, the majority of caregivers (44.4%) provided care for 4-6 years, while others provided care for 1-3 years (22.2%) or more than 10 years (22.2%).

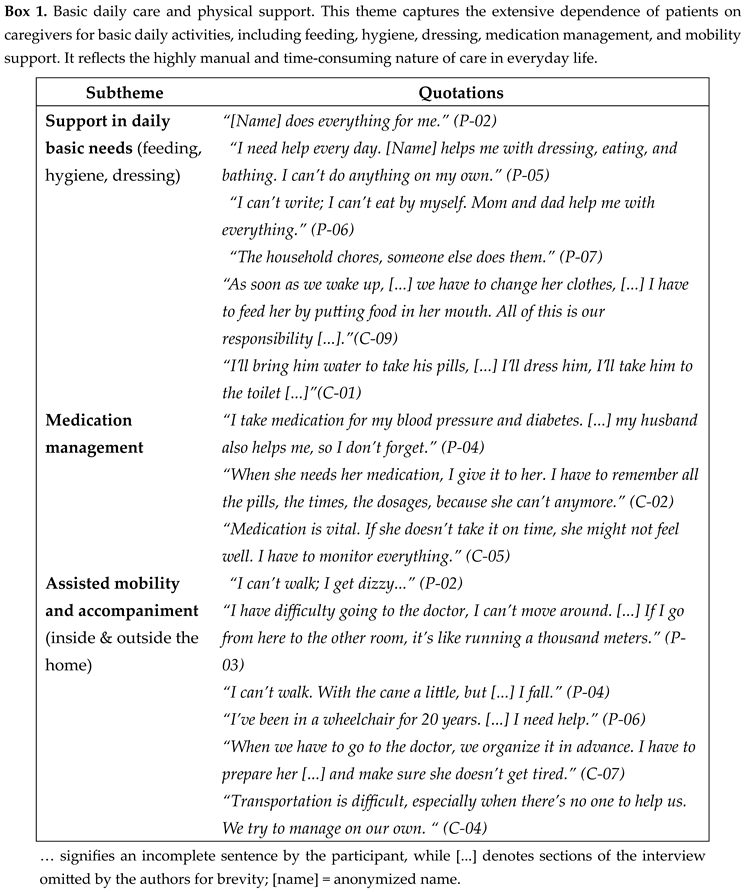

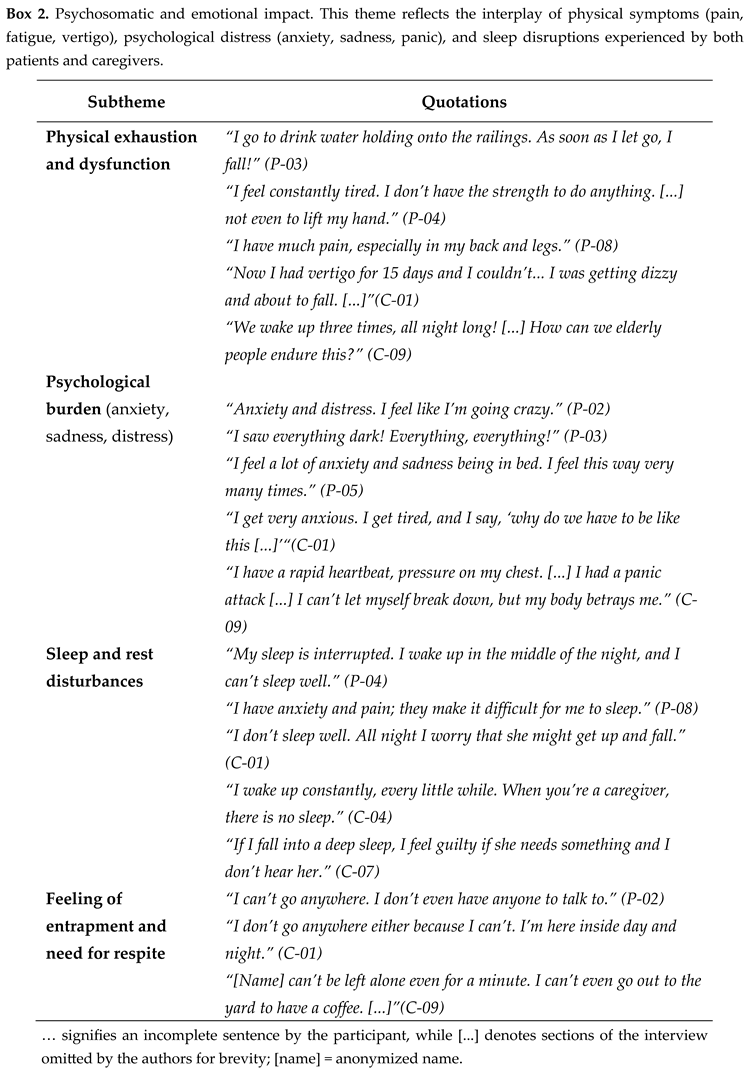

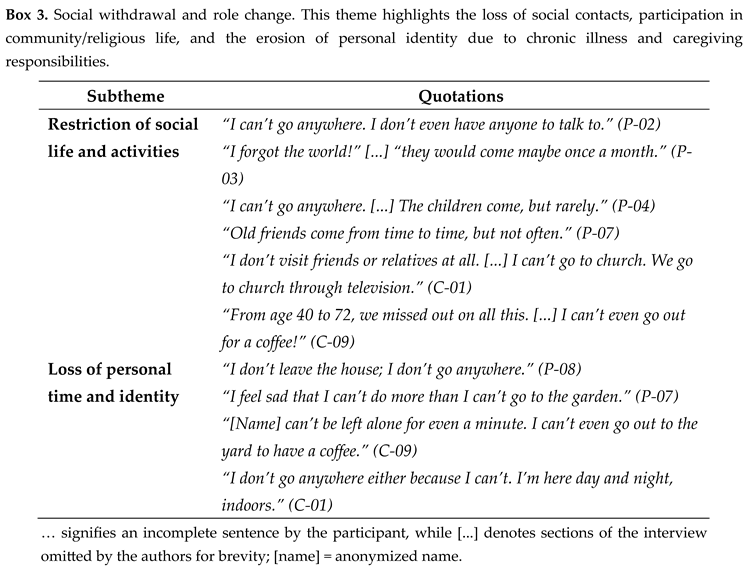

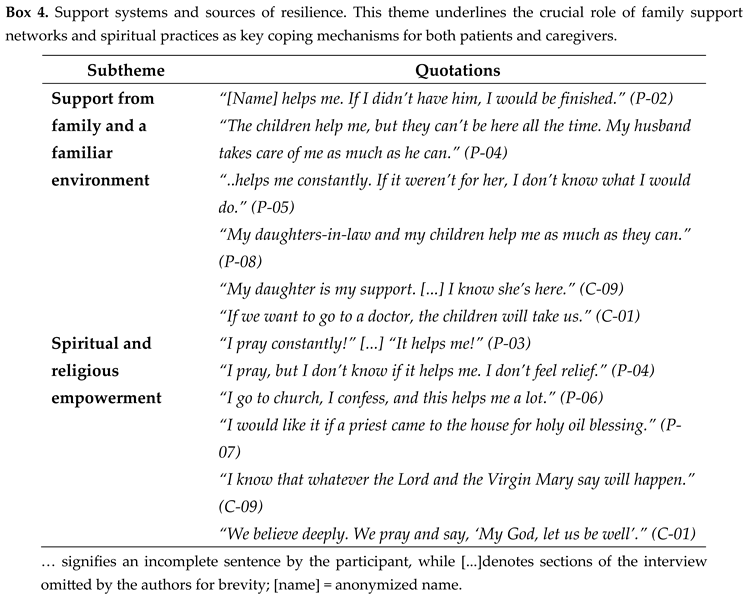

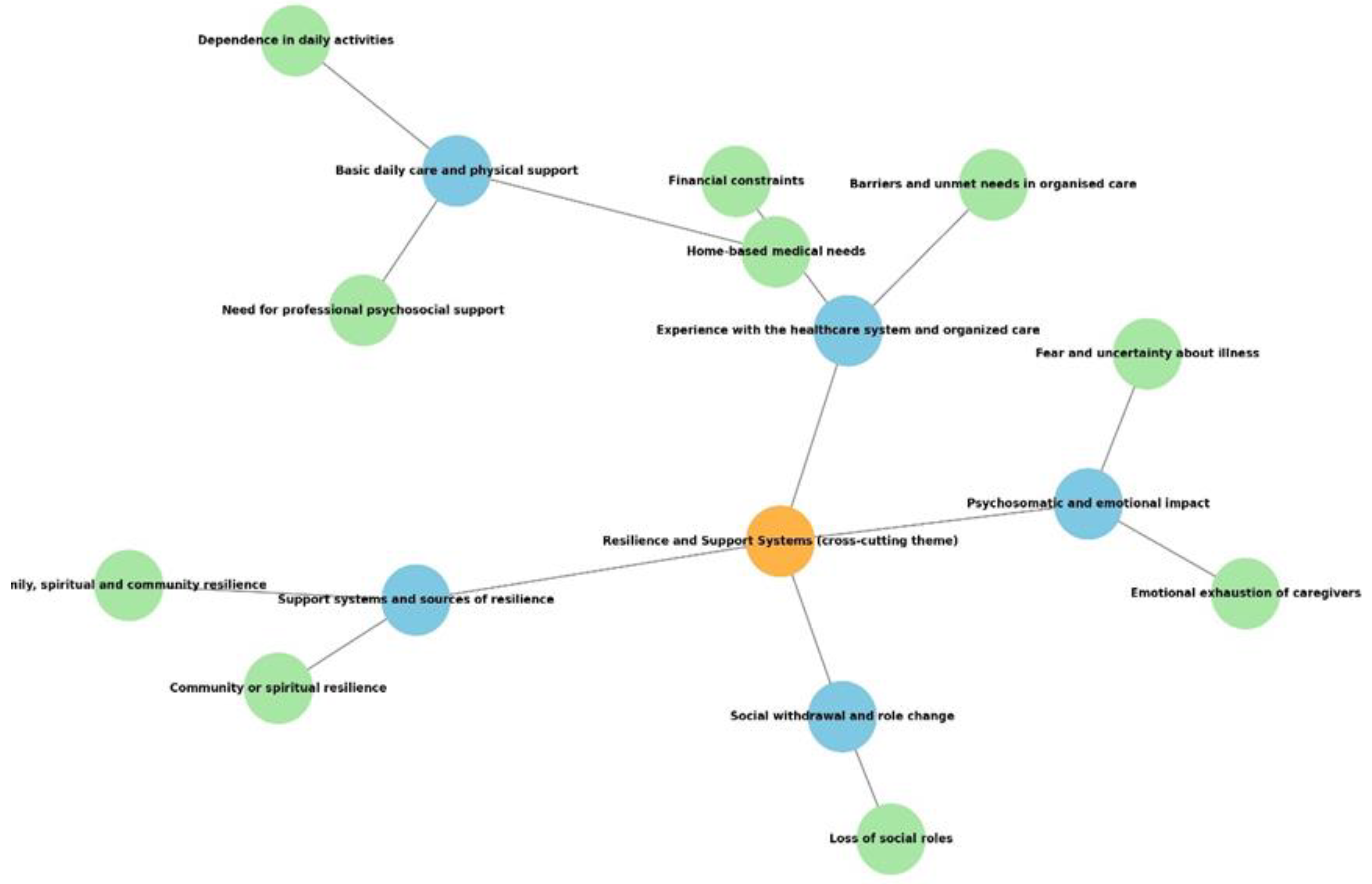

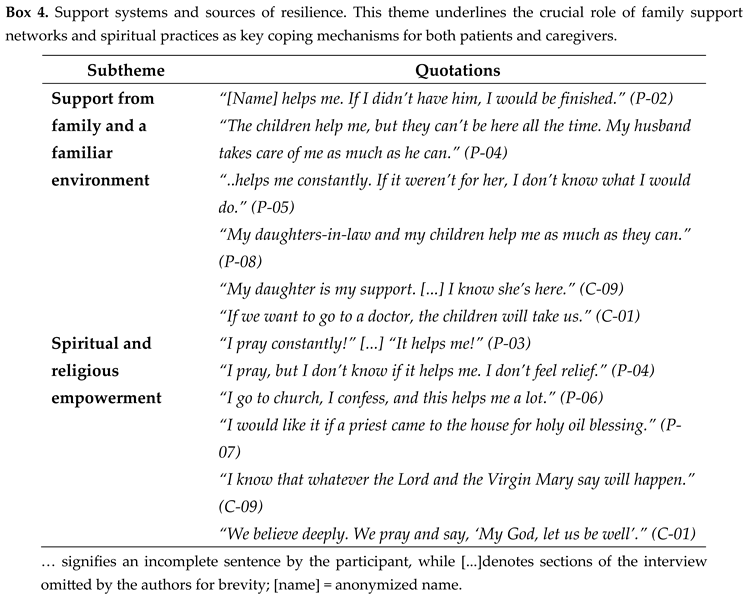

The analysis revealed five key themes: (1) Basic daily care and physical support; (2) Psychosomatic and emotional impact; (3) Social withdrawal and role change; (4) Support systems and sources of resilience; and (5) Experience with the healthcare system and organized care. Representative quotations for these themes and their subcategories are provided in Boxes 1–5, showcasing both common perspectives and the range of experiences among participants. Notably, the fourth theme, Support systems and sources of resilience, captured not only the participants’ reliance on external networks—such as family, friends, and community—but also their inner adaptive capacities, including hope, faith, and personal strength that facilitated coping with chronic illness. This theme emerged as a cross-cutting dimension interwoven through the physical, emotional, and social domains, highlighting resilience as an integral aspect of the lived experience of both patients and caregivers. [

21,

28,

29]. The participant quotations presented below are illustrative examples, selected to reflect the breadth and depth of responses rather than to represent all individuals who expressed each subtheme. The relative distribution of themes and subthemes is available in the Supplementary Material (

Table S3). To provide an overview of the analytic process and the interrelation between codes and themes,

Figure 1 presents a thematic map summarizing the five overarching themes and their corresponding codes.

The findings summarized in Boxes 1–5 are presented in more detail below. Each section follows the structure “summary — characteristic excerpts — interpretation/implications” to clearly convey the meaning of participants’ statements and the practical needs that emerge from them. All quotations are attributed using pseudonyms (P-xx for patients and C-xx for caregivers) to ensure anonymity; individual demographic and clinical profiles are provided in

Supplementary Table S4.

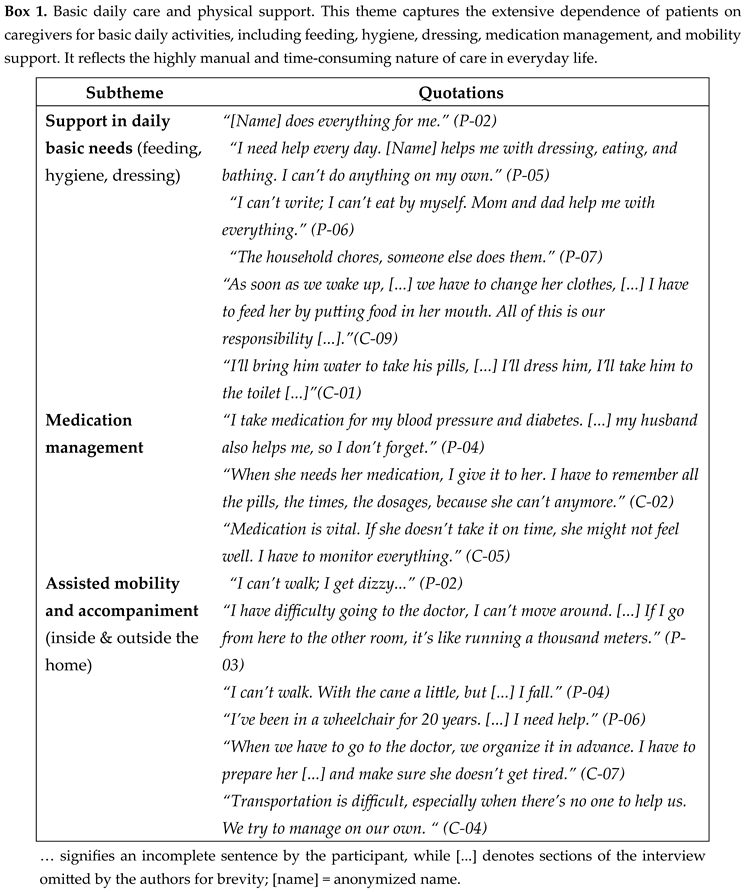

Basic Daily Care and Physical Support

Participants describe extensive dependence in daily activities (eating, personal hygiene, and dressing) and a clear burden in managing medication and mobility. Statements indicate that many basic actions considered “simple” have become entirely dependent on the caregiver: “[Name] does everything for me.” (P-02), “I need help every day... he/she dresses me, feeds me, bathes me—I can’t do anything on my own.” (P-05). Medication management emerged as a daily, critical responsibility for caregivers: “When medication is needed, I give it to him/her — I have to remember all the doses and times.” (C-02). Mobility problems and difficulty moving around (falls, dizziness, and prolonged sedentary lifestyle) accompany and complicate the process of accessing healthcare services (e.g., appointments): “I can’t walk, I get dizzy... when we have to go to the doctor, we plan it well in advance.” (P-03 / C-07).

The data indicate a need for targeted interventions in the home, including nursing care visits, medication management support, mobility aids, and transportation services. The daily, highly manual nature of care places a burden on the caregiver and increases the risk of treatment errors.

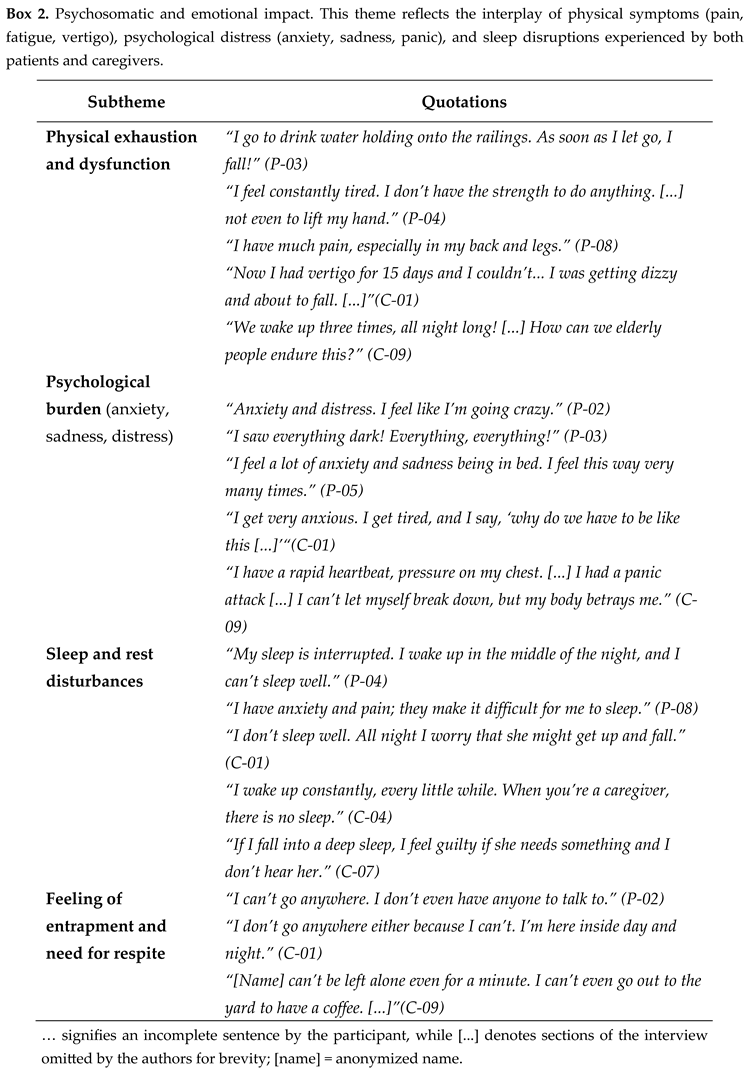

Psychosomatic and Emotional Impact

Participants often report a combination of physical symptoms (pain, fatigue, dizziness) with intense psychological distress (anxiety, sadness, panic attacks) and severe sleep disturbances. Examples: “I go to drink water holding onto the railings—if I let go, I fall!” (P-03), “I have much pain in my back and legs.” (P-08), “I feel anxious and sad—many times I feel like I’m going crazy.” (P-02). Caregivers also describe constant alertness and guilt when sleeping, which disrupts their rest: “If I sleep deeply, I feel guilty that she might need me and I won’t hear her.” (C-07).

Physical symptoms and psychological distress feed into each other — inadequate pain control and sleep disturbances increase anxiety and reduce caregiving resilience. A holistic approach is needed that combines analgesic/symptomatic management with psychological support, as well as respite structures to reduce the ongoing burden.

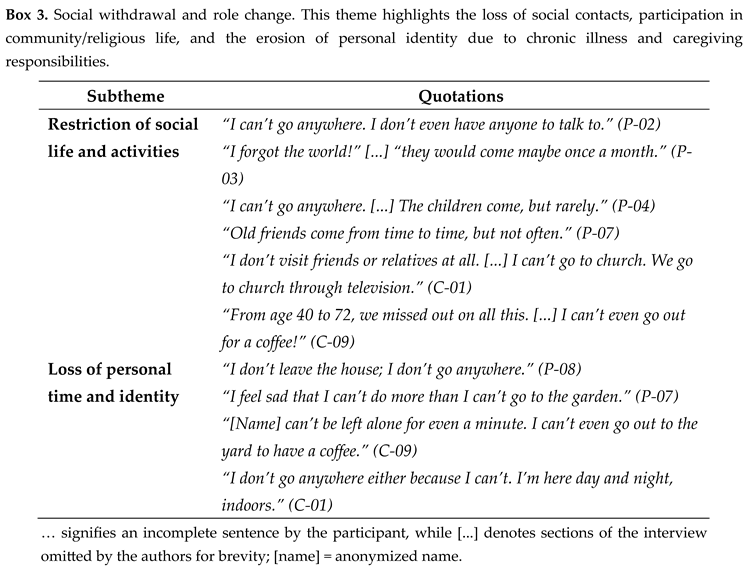

Social Withdrawal and Role Change

The data show significant social isolation and loss of personal time and identity, both for patients and caregivers. Excerpts describe “forgetting the world” and loss of participation in social and religious activities: “I’ve forgotten the world—they come maybe once a month.” (P-03), “I don’t go to church — we go to church on TV.” (C-01). Caregivers report that caregiving has taken over their personal time (“I can’t even go out for a coffee.” C-09).

The gradual weakening of social relationships and changing roles (e.g., the spouse becomes the sole caregiver) undermines mental health and feelings of autonomy. The findings support the need for social reintegration programs, support groups, and semi-autonomous care structures (e.g., day centers) that protect the identity and social network of those involved.

Support Systems and Sources of Resilience

Family and close friends emerge as the primary source of support: “Sotiris helps me—if I didn’t have him, I would be finished” (P-02), “My daughters/children help as much as they can” (P-08). At the same time, religiosity and spiritual practice serve as coping strategies: “I pray constantly—it helps me.” (P-03), “I would like a priest to come to my home.” (P-07).

Family networks and spiritual beliefs offer essential emotional and practical support — but reliance on private assistance and religious comfort does not replace the need for systematic professional support. Interventions should incorporate family education, recognition of caregivers’ roles, and, where requested, spiritual care as part of the care plan.

Experience with the Healthcare System and Organized Care

Participants report repeated difficulties in accessing services (waiting times, lack of transportation, inability to find a doctor to write a prescription) and financial burden: “We can’t find a doctor to prescribe medication...” (P-03), “The pension is not even enough to cover the medication.” (P-08). There is an apparent demand for home-based services—physiotherapy, nursing support, personal assistants—and for organized care structures: “It would help if a physiotherapist came to the house.” (P-02), “There is no training for caregivers — we learn on our own.” (C-09 / C-08). Many also express a desire for psychological support but say they do not have the time or means to seek it.

The findings describe gaps in frontline and community care structures and services — the lack of adequate accessibility and information affects both patients’ health and the sustainability of care provided by the informal network. Urgent needs that arise include establishing home-based services (physiotherapy, nursing), organizing caregiver training programs, implementing financial relief mechanisms, and establishing respite care structures.

Boxes 1–5 show a consistent pattern: high dependence on basic activities and medication management, intense psychosomatic stress, social isolation, significant intra-family support, but also institutional gaps in services and caregiver training. The findings show that interventions that simultaneously target symptom relief, support caregivers, and strengthen community- and home-based services are likely to yield the most significant benefit for the quality of life of both patients and their families.

Cross-Cutting Dimension: Resilience and Sources of Support

Beyond the five major themes, the qualitative data revealed an overarching, cross-cutting dimension that permeated participants’ experiences — that of resilience and sources of support. While dependence, emotional strain, and institutional barriers were recurrent, many participants demonstrated active coping and adaptive strategies that allowed them to maintain a sense of purpose, hope, and continuity within chronic adversity.

As patients and caregivers narrated their daily realities, resilience emerged not as an absence of suffering but as the ability to adapt through relationships, faith, and small acts of endurance. Several participants described how emotional strength stemmed from their close family bonds — for instance, one patient explained, “If I didn’t have my husband, I’d be lost” (P-02). At the same time, a caregiver reflected that “even when I’m tired, I think, ‘I can do this because she needs me’” (C-07). Others drew comfort and stability from their spirituality, emphasizing prayer as a daily anchor: “We pray and say, ‘My God, let us be well’” (C-01). The reassurance of family presence also played a vital role, as another caregiver shared, “My daughter supports me… I know she’s here” (C-09).

These narratives illustrate how both internal and external resources — psychological endurance, family ties, and spiritual belief — served as mechanisms of adjustment that buffered psychosomatic and social strain. The coexistence of vulnerability and perseverance suggests that resilience functions as an integral psychosocial resource that cuts across all domains identified: mitigating emotional burden (Box 2), counteracting social withdrawal (Box 3), reinforcing familial and spiritual support (Box 4), and compensating for structural deficiencies in healthcare services (Box 5).

This emergent understanding aligns with the conceptualization of resilience as a dynamic and relational process [

34,

36] and informed the development of a new dimension — “Resilience and Sources of Support” — in the subsequent adaptation of the needs-assessment framework. Recognizing resilience as a cross-domain construct emphasizes not only the challenges but also the adaptive capacities that shape the lived experience of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers.

4. Discussion

The findings of this qualitative study demonstrate a multidimensional framework of needs and experiences for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers, as revealed through thematic analysis. Specifically, the five central themes are: (1)

basic daily care and physical support, (2)

psychosomatic and emotional impact, (3)

social withdrawal and role change, (4)

support systems and sources of resilience, and (5)

experience with the healthcare system and organized care. These results align with and add nuance to previous findings on the needs of patients [

12,

13,

14] and caregivers in the field of PC [

37,

38].

Participants’ reports of caring for basic needs (feeding, personal hygiene, mobility, medication management) underscore the extent of physical dependence and daily burdens borne by caregivers. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing a high symptom burden and functional dependence in patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, comparable to or even higher than those with cancer. [

12,

17,

21]. The findings from our sample suggest a possible need for personalised home services—for example, home physical therapy or medication management support—which is also supported in the literature as a potentially critical factor in maintaining quality of life and reducing hospitalisation. [

28,

29,

39].

The psychological and emotional impact described by patients and caregivers—

anxiety, sadness, sleep disturbances, and feelings of entrapment—is consistent with the literature on the heavy psychological burden of caring for chronically ill patients and their caregivers [

23]. The sleep disruption and constant vigilance of caregivers highlighted in the research are linked to impacts on health and the ability to continue caregiving; our findings point to the potential value of relief interventions and respite care structures, a strategy that has been described as effective, which have been described as effective support strategies [

40].

The third theme—social withdrawal and role change—reflects the role changes and shrinking social network that often accompany chronic illness. Such changes take a toll on both patients’ mental health and family dynamics, and have been described in previous studies as key indicators of reduced quality of life [

28,

30,

41]. The importance of the social void also highlights the role that community services and reintegration or social support programs can play. In contrast, the theme of support networks shows that family ties, religious practice, and a familiar environment serve as sources of resilience alongside formal care systems. This finding is consistent with the literature describing the protective role of social connection and spiritual/religious resources in coping with chronic illness [

11,

13] These themes were consistently observed across interviews, supporting the adequacy of the sample in achieving thematic saturation. However, dependence on private assistance and family care also highlights the unequal distribution of resources and the need for formal support to prevent excessive burden on families.

Moreover, the emergence of

resilience and sources of support as a cross-cutting element in participants’ narratives extends beyond the traditional focus on burden and suffering. Patients and caregivers demonstrated an active process of adaptation, drawing emotional strength from relationships, spirituality, and inner determination. This dynamic understanding of resilience is consistent with prior conceptualizations as a relational and context-dependent process [

34,

36], highlights the need for PC approaches that not only alleviate distress but also strengthen existing psychosocial resources. Integrating resilience-building strategies — such as family counseling, spiritual care, and peer-support networks — could enhance both coping capacity and overall quality of life for patients and caregivers.

Beyond the interpersonal and emotional domains, participants also described structural barriers. Experiences of difficulty accessing medical services, financial burden, and lack of training/information for caregivers were consistently reported by both patients and caregivers, constituting critical findings with significant policy implications. In Greece, where specialized PC services are limited, patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions and their caregivers confirm the need to strengthen community structures and “home help” programs [

2,

27]. The lack of caregiver training is consistent with international evidence that caregiver education and training are critical interventions for improving the quality of care and caregivers’ well-being. [

25,

42].

The study has some strong points: collecting data in the participants’ familiar environment gave depth and authenticity to the narratives; the thematic analysis was conducted with the rigor recommended by theoretical approaches [

32] and the analysis was conducted in Greek, preserving cultural and linguistic accuracy. At the same time, the study’s limitations stem from the sample’s contextual specificity, which may limit the transferability of the findings to other settings. Limitations affecting generalizability include a small sample size and a geographic concentration in one municipal service. Although a purposive sampling strategy with maximum variation was employed, the range of participant characteristics was shaped by the specific service context, resulting in a sample that was predominantly older adults and had lower educational levels. These characteristics reflect the population served rather than a lack of sampling variation, and should be considered when interpreting the transferability of the findings, as is commonly acknowledged in qualitative research [

36,

43]. In addition, there may be a selective bias, as individuals with severe problems or objections to the care provided may not have responded. Furthermore, patients at an end-of-life stage were not systematically included; this reflects the structure of available services and recruitment pathways rather than an explicit exclusion criterion and may have limited the representation of experiences closer to the end of life.

To enhance methodological rigour and transparency, the study was designed and reported in accordance with established qualitative research quality criteria, including the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ;

Table S5) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP;

Table S6) checklist. Credibility was supported through in-depth interviews, iterative data analysis, and the consistent recurrence of themes across participants, indicating adequate information power. Dependability and confirmability were strengthened through systematic coding procedures, reflexive discussions among the research team, and careful documentation of analytic decisions. The inclusion of both patient and caregiver perspectives further enriched and strengthened the findings by enabling triangulation of perspectives on patients’ palliative care needs. While the study is context-specific, the detailed description of the setting, participants, and analytic process supports the transferability of findings to similar community-based palliative care contexts. Overall, the study provides a robust qualitative foundation for informing future research and the development of patient-centred needs assessment tools within PC services.

Practical and policy implications: findings from this study are consistent with proposals to strengthen community PC services tailored to patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions [

17,

21,

29]. It is recommended to develop: (a) home-based physiotherapy and nursing support programs, (b) temporary respite care structures for caregivers, (c) systematic education and information for caregivers/patients [

25] and (d) financial/administrative support mechanisms for service access. In addition, strengthening cooperation among primary, secondary, and community services can improve continuity of care and reduce service fragmentation that burdens patients and their families.

Suggestions for future research: The current findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations, and further qualitative research with larger, more diverse populations is essential to confirm their transferability in similar populations. Larger, multicenter quantitative studies are needed to evaluate the impact of specific interventions (e.g., caregiver education programs, home-based physical therapy services) on quality of life, health service utilization, and caregiver burden [

10]. The development and validation of needs assessment tools specifically for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, as suggested by the study’s design, will contribute to standardizing referral criteria and monitoring service effectiveness [

12].