Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Framework

3. Methodology

4. Findings & Analysis

4.1. Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT)

4.2. De Meyers’ Innovation Ecosystem Implications in the FinTech Sector

4.3. Value Chain Theory Implications/Mapping in the FinTech Sector

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion and Contribution

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IDT | Innovation Diffusion Theory |

| ESG | Environmental, Social and Governance |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| MSE | Micro and Small Enterprises |

| NFC | Near-field communication |

| IT-Data-KYC | Information Technology – Data – Know Your Customer |

| QCA | Qualitative Content Analysis |

| B2B | Business-to-Business. |

| AML | Anti-Money Laundering. |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| SLA | Service Level Agreement |

| EU | European Union |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Stakeholder Questionnaire – FinTechs BOD

- What is your professional background, and how did you become a board member of this FinTech?

- How do you relate to the mission and vision of your FinTech company?

- What innovations does your firm offer that improve on traditional financial services?

- How do your products or platforms align with customer values and market needs? (Fit between the innovation and the target users’ lifestyles or expectations)

- What are the paramount usability or adoption challenges you’ve (or your users have) encountered?

- How do you allow customers to test or pilot your products before full use?

- What mechanisms help demonstrate the impact of your offerings (e.g., case studies, testimonials)?

- Who are the most critical partners in your business ecosystem (e.g., enablers, regulators, adopters)?

- What barriers have you encountered in navigating ecosystem relationships (e.g., with regulators or banks)?

- How do you foster trust, co-creation, or collaborative development with other ecosystem players? (Mutual development of innovation with partners)

- How does your firm contribute to or benefit from knowledge-sharing environments (events, consortia)?

- How has your role evolved—from a niche innovator to a keystone or Orchestrator (if applicable)? (Lifecycle progression within the ecosystem)

- How has your value proposition evolved since the company’s inception?

- What operational functions are handled in-house vs. outsourced, and why? (Internal capability vs. third-party reliance)

- How do you structure your company to ensure scalability while staying compliant?

- Do you track specific KPIs to evaluate business model performance?

- How does your business model align with national or EU-level goals for FinTech?

- What advice would you give to future FinTech board members or founders entering this space?

- Can you share an anecdote or memorable board discussion about innovation or transformation?

- How do you see your firm’s role evolving within the Latvian FinTech landscape in the next 5 years?

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Emerging Concepts from the QCA of the Interviews

References

- E. M. Rogers, Diffusion of innovations, Fifth edition. New York London Toronto Sydney: Free Press, 2003.

- P. J. Williamson and A. De Meyer, ‘Ecosystem Advantage: How to Successfully Harness the Power of Partners’, California Management Review, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 24–46, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Teece, ‘Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation’, Long Range Planning, vol. 43, no. 2–3, pp. 172–194, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Clauss, ‘Measuring business model innovation: conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance’, R & D Management, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 385–403, June 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. M. Shaikh and H. Amin, ‘Influence of innovation diffusion factors on non-users’ adoption of digital banking services in the banking 4.0 era’, IDD, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 12–21, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Koranteng and K. You, ‘Fintech and financial stability: Evidence from spatial analysis for 25 countries’, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, vol. 93, p. 102002, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Yáñez-Valdés and M. Guerrero, ‘Assessing the organizational and ecosystem factors driving the impact of transformative FinTech platforms in emerging economies’, International Journal of Information Management, vol. 73, p. 102689, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Siddiqui and C. A. Rivera, ‘MAPPING FINTECH LANDSCAPE IN LATVIA: TAXONOMY-BASED CLASSIFICATION AND ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS’, PJMS, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 304–319, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen and Q. Guo, ‘Fintech and MSEs Innovation: an Empirical Analysis’, 2024, arXiv. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Takahashi, J. C. B. D. Figueiredo, and E. Scornavacca, ‘Investigating the diffusion of innovation: A comprehensive study of successive diffusion processes through analysis of search trends, patent records, and academic publications’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 198, p. 122991, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Cornelli, J. Frost, L. Gambacorta, and J. Jagtiani, ‘The impact of fintech lending on credit access for U.S. small businesses’, Journal of Financial Stability, vol. 73, p. 101290, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan, N. Sun, S. J. Wu, and Y. Sun, ‘Supply Chain Finance, Fintech Development, and Financing Efficiency of SMEs in China’, Administrative Sciences, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 86, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Rupeika-Apoga and S. Wendt, ‘FinTech in Latvia: Status Quo, Current Developments, and Challenges Ahead’, Risks, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 181, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Kapoor, Y. K. Dwivedi, and M. D. Williams, ‘Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Attributes: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Existing Research’, Information Systems Management, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 74–91, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Tarhini, N. A. G. Arachchilage, R. Masa’deh, and M. S. Abbasi, ‘A Critical Review of Theories and Models of Technology Adoption and Acceptance in Information System Research’:, International Journal of Technology Diffusion, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 58–77, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Kaur, A. Dhir, R. Bodhi, T. Singh, and M. Almotairi, ‘Why do people use and recommend m-wallets?’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 56, p. 102091, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Kapoor, Y. K. Dwivedi, and M. D. Williams, ‘Empirical Examination of the Role of Three Sets of Innovation Attributes for Determining Adoption of IRCTC Mobile Ticketing Service’, Information Systems Management, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 153–173, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J.-P. Tsai and C.-F. Ho, ‘Does design matter? Affordance perspective on smartphone usage’, Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 113, no. 9, pp. 1248–1269, Sept. 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, ‘Frugal innovation and the digital divide: Developing an extended model of the diffusion of innovations’, International Journal of Innovation Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 53–64, June 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Weerakkody, Z. Irani, K. Kapoor, U. Sivarajah, and Y. K. Dwivedi, ‘Open data and its usability: an empirical view from the Citizen’s perspective’, Inf Syst Front, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 285–300, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Sikandar, Y. Vaicondam, N. Khan, M. I. Qureshi, and A. Ullah, ‘Scientific Mapping of Industry 4.0 Research: A Bibliometric Analysis’, Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol., vol. 15, no. 18, pp. 129–147, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. MINÀ and G. B. DAGNINO, ‘Competition and cooperation in entrepreneurial ecosystems: a lifecycle analysis of a Canadian ICT ecosystem’, in Innovation, Alliances, and Networks in High-Tech Environments, 1st edn, Routledge, 2015, pp. 65–81.

- D. B. Audretsch, J. A. Cunningham, D. F. Kuratko, E. E. Lehmann, and M. Menter, ‘Entrepreneurial ecosystems: economic, technological, and societal impacts’, J Technol Transf, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 313–325, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Colombo, G. B. Dagnino, E. E. Lehmann, and M. Salmador, ‘The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems’, Small Bus Econ, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 419–428, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Reynolds and Y. Uygun, ‘Strengthening advanced manufacturing innovation ecosystems: The case of Massachusetts’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 136, pp. 178–191, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Talmar, B. Walrave, K. S. Podoynitsyna, J. Holmström, and A. G. L. Romme, ‘Mapping, analyzing and designing innovation ecosystems: The Ecosystem Pie Model’, Long Range Planning, vol. 53, no. 4, p. 101850, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Etzkowitz and L. Leydesdorff, ‘The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations’, Research Policy, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 109–123, Feb. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Cunningham, M. Menter, and C. O’Kane, ‘Value creation in the quadruple helix: a micro level conceptual model of principal investigators as value creators’, R & D Management, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 136–147, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Ritala, V. Agouridas, D. Assimakopoulos, and O. Gies, ‘Value creation and capture mechanisms in innovation ecosystems: A comparative case study’, Int. J. of Technology Management, vol. 63, no. 3–4, pp. 244–267, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Tansley, ‘The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms’, Ecology, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 284–307, July 1935. [CrossRef]

- J. Moore, ‘Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition’, Harvard business review, vol. 71, pp. 75–86, May 1999.

- R. C. Basole and J. Karla, ‘On the Evolution of Mobile Platform Ecosystem Structure and Strategy’, Bus Inf Syst Eng, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 313–322, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- O. Granstrand and M. Holgersson, ‘Innovation ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition’, Technovation, vol. 90–91, p. 102098, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Stefanelli, F. Manta, and P. Toma, ‘Digital financial services and open banking innovation: are banks becoming invisible?’, 2022, arXiv. [CrossRef]

- J. Kálmán, ‘The Role of Regulatory Sandboxes in FinTech Innovation: A Comparative Case Study of the UK, Singapore, and Hungary’, FinTech, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 26, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Zott and R. Amit, ‘Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective’, Long Range Planning, vol. 43, no. 2–3, pp. 216–226, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Adner, ‘Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy’, Journal of Management, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 39–58, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Gomber, R. J. Kauffman, C. Parker, and B. W. Weber, ‘On the Fintech Revolution: Interpreting the Forces of Innovation, Disruption, and Transformation in Financial Services’, Journal of Management Information Systems, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 220–265, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- I. Lee and Y. J. Shin, ‘Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges’, Business Horizons, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 35–46, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Morris, M. Schindehutte, and J. Allen, ‘The entrepreneur’s business model: toward a unified perspective’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 726–735, June 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Johnson, C. M. Christensen, and H. Kagermann, ‘Reinventing Your Business Model’, vol. 87, no. 12, pp. 52–60, 2008.

- A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur, Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. New York: Wiley&Sons, 2013.

- R. K. Yin, Case study research and applications: design and methods, Sixth edition. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: SAGE, 2018.

- P. Mayring, ‘Qualitative Content Analysis’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal]. https://qualitative-research.net/fqs/fqs-e/2-00inhalt-e.htm, vol. 1, no. 2, June 2000.

- M. Schreier, Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice, vol. 1. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012. [CrossRef]

- V. Sharma, R. Rupeika-Apoga, T. Singh, and M. Gupta, ‘Sustainable Investments in the Blue Economy: Leveraging Fintech and Adoption Theories’, JRFM, vol. 18, no. 7, p. 368, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, Y. Fang, City University of Hong Kong, H. Zou, and City University of Hong Kong, ‘Choosing a Fit Technology: Understanding Mindfulness in Technology Adoption and Continuance’, JAIS, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 377–412, June 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Zolkepli and Y. Kamarulzaman, ‘Social media adoption: The role of media needs and innovation characteristics’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 43, pp. 189–209, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Thakur and M. Srivastava, ‘Adoption readiness, personal innovativeness, perceived risk and usage intention across customer groups for mobile payment services in India’, Internet Research, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 369–392, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Fenwick, E. P. M. Vermeulen, and M. Corrales, ‘Business and Regulatory Responses to Artificial Intelligence: Dynamic Regulation, Innovation Ecosystems and the Strategic Management of Disruptive Technology’, in Robotics, AI and the Future of Law, M. Corrales, M. Fenwick, and N. Forgó, Eds, in Perspectives in Law, Business and Innovation. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2018, pp. 81–103. [CrossRef]

- R. Adner, ‘Match Your Innovation Strategy to Your Innovation Ecosystem’, HBR Spotlight, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 98–107, 2006.

- S. Sangwa, S. Ndahimana, and F. Dusengumuremyi, ‘Diffusion of Innovation vs. Dependence Theory: FinTech Inclusion in the AfCFTA Era’, SSRN Journal, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 45–107, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Jangid, D. P. Bal, and N. V. M. Rao, ‘Role of FinTech and technological innovation towards energy, growth, and environment nexus in G20 economies’, Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 20057, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Yong, M. Yusliza, T. Ramayah, C. J. Chiappetta Jabbour, S. Sehnem, and V. Mani, ‘Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management’, Bus Strat Env, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 212–228, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. W. F. Kouam, ‘The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Fintech Innovation and Financial Inclusion: A Global Perspective’, Nov. 15, 2024, In Review. [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders’ Initial codes | FinTech Initial codes | Stakeholders sub-theme | FinTech sub-theme | Stakeholder Grand theme | FinTech Grand theme | |

| Total codes | 183 | 177 | 81 | 78 | 42 | 41 |

| Max | 21 | 25 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| Min | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Average | 12 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

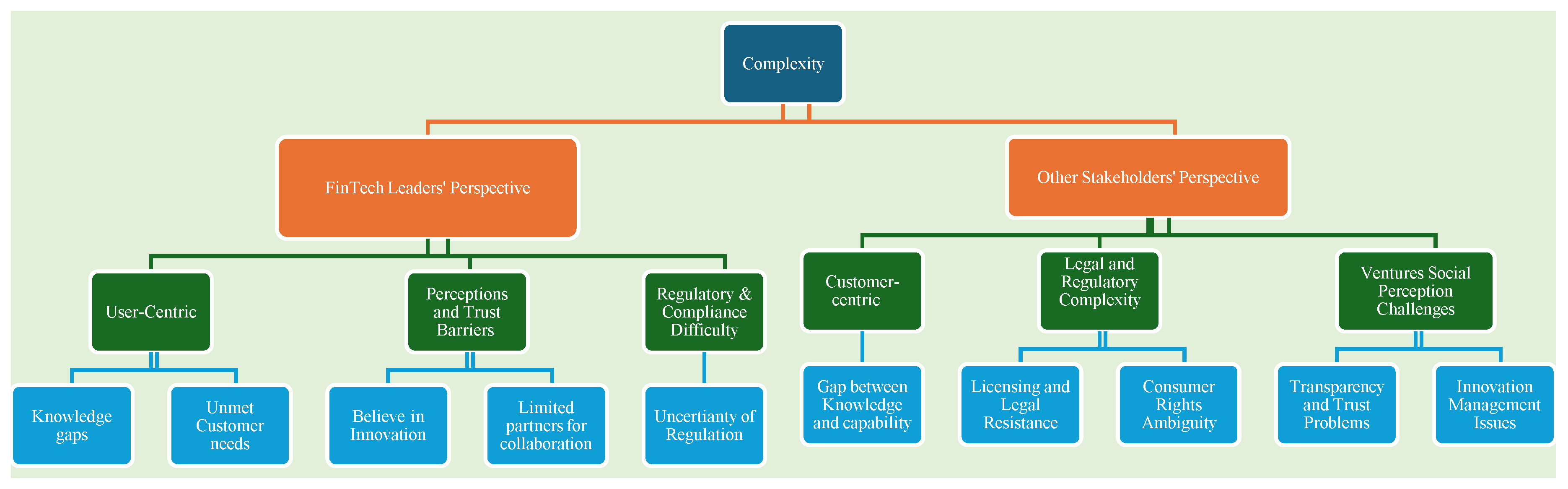

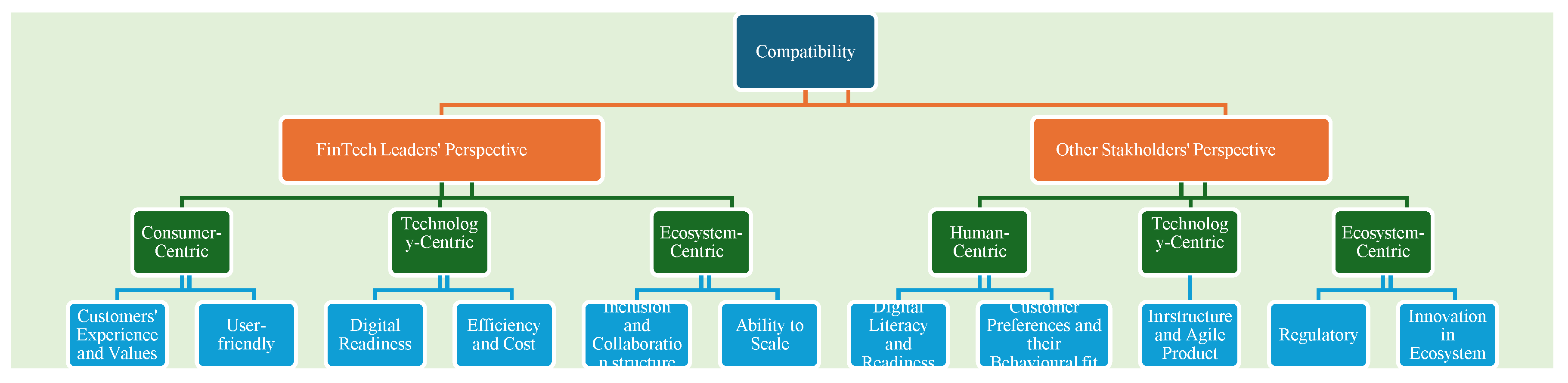

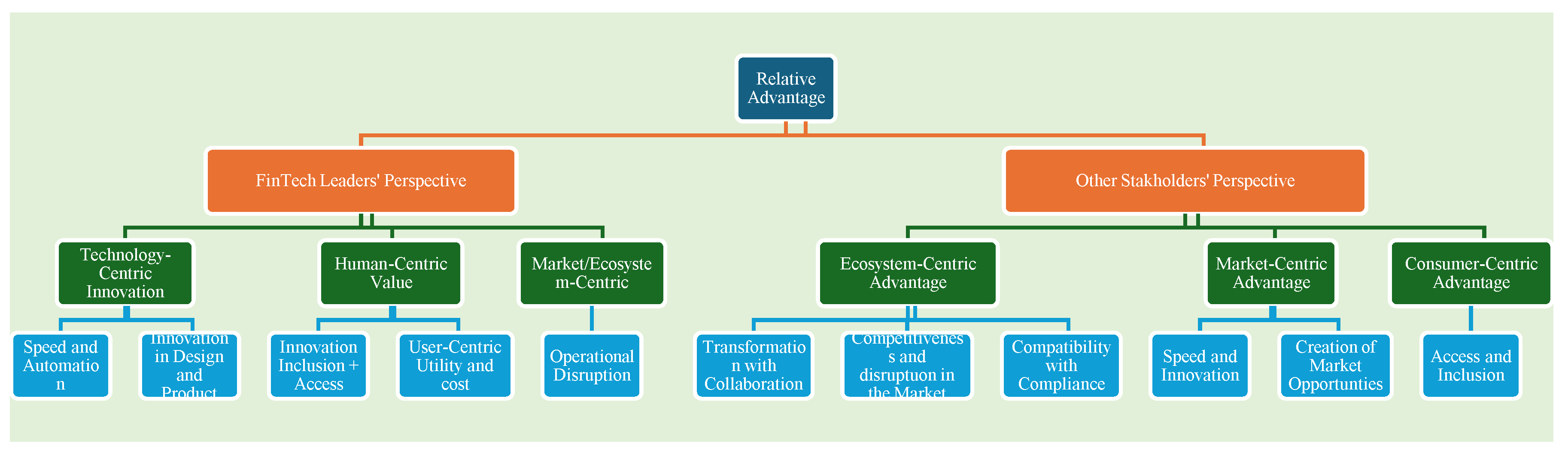

| IDT Attribute | FinTech Key Responses | Non-FinTech Key Responses |

| Relative Advantage | • Technology-centric reasons: speed, automation, and product innovativeness. • Human-centric reasons: FinTech solutions serve underserved customers, increase end-user empowerment, provide digital platforms for accessibility, reduce costs through intermediary reduction, and supplement banks’ services. • Market-centric reasons: bring operational disruption through white-label strategy and new B2B models such as Platform as a Service (PaaS). |

• Ecosystem-centric advantage: transformation within collaboration. • Market-centric advantage: speed and innovation. • Consumer-centric advantage: access and inclusion. • Compliance with regulations is identified as a major concern, causing tension between regulators and FinTechs. |

| Compatibility | • Technology-centric reasons: FinTech services complement the digital readiness of its audience, requiring automated solutions and digital onboarding. • Human-centric reasons: FinTech services are customized to meet customers’ needs (individual and business, banked or unbanked). • Market-centric reasons: FinTech services serve the need for scalability of businesses. |

• Human-centric reasons: The Latvian market is prepared for digitalized financial services, but digital disparity persists across regions. • Technology-centric reasons: banks develop iterative and agile digital products to improve competitiveness. • Regulatory reasons: FinTechs must educate the public and businesses about innovation and digital security. |

| Complexity | • Technology-centric reasons: users prefer hybrid solutions combining new and familiar methods. • Human-centric reasons: tech-knowledge gaps among demographic groups create demand for simpler solutions. • Market-centric reasons: limited trust and regulatory uncertainty hinder collaboration. |

• Technology-centric reasons: strict regulations and licensing justified for consumer protection. • Human-centric reasons: lack of transparency leads to trust deficit and risk aversion. • Market-centric reasons: negative social responsibility perceptions reinforce risk aversion. |

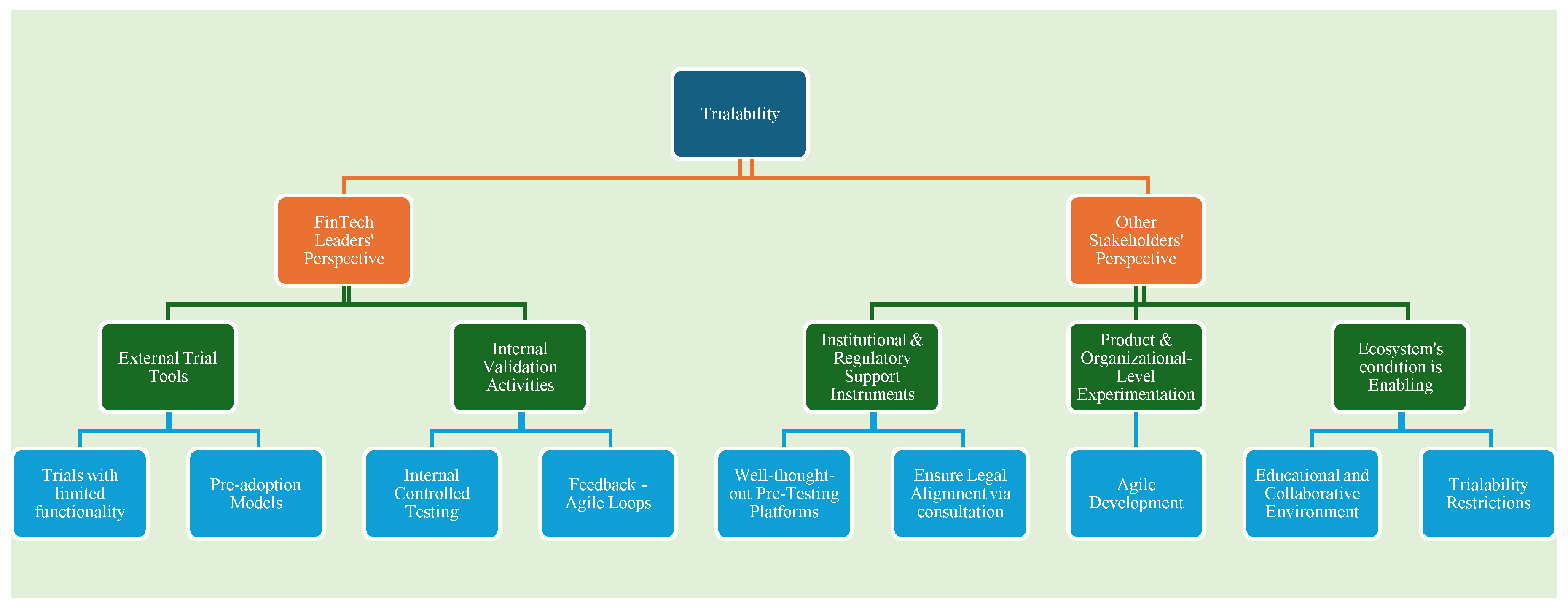

| Trialability | • Technology-centric reasons: FinTech develops services in agile form based on user feedback to meet market needs. • Human-centric reasons: users test services internally and externally via freemium and pre-adoption models. • Market-centric reasons: bottom-up trialability reduces risk and increases adaptability. |

• Technology-centric reasons: sandboxes and innovation hubs enable pilot testing. • Human-centric reasons: regulators use experiments to educate and increase readiness. • Market-centric reasons: trialability is seen as a top-down mechanism, contrasting the FinTech approach. |

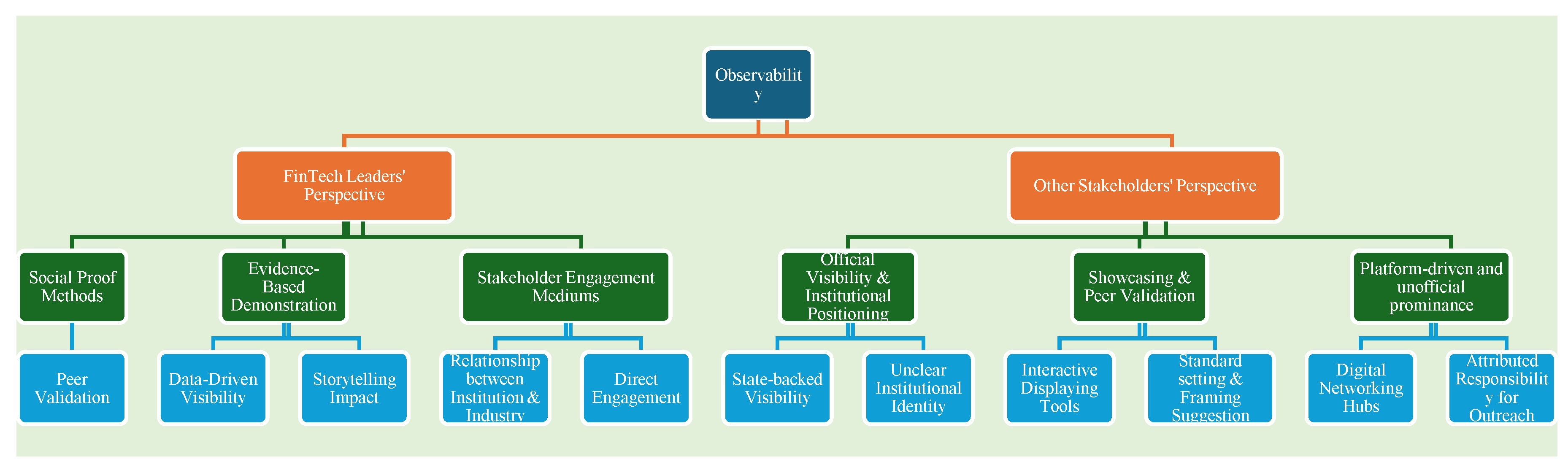

| Observability | • Technology-centric reasons: sandbox initiatives enhance visibility and trust. • Human-centric reasons: FinTech users are often unaware of the term “FinTech” despite using innovative services. • Market-centric reasons: FinTechs publish reports and share success stories to build relationships with businesses and regulators. |

• Technology-centric reasons: licensed public registries and documentation provide visibility. • Human-centric reasons: associations and events give FinTechs exposure. • Market-centric reasons: cross-stakeholder collaboration increases observability and credibility. |

|

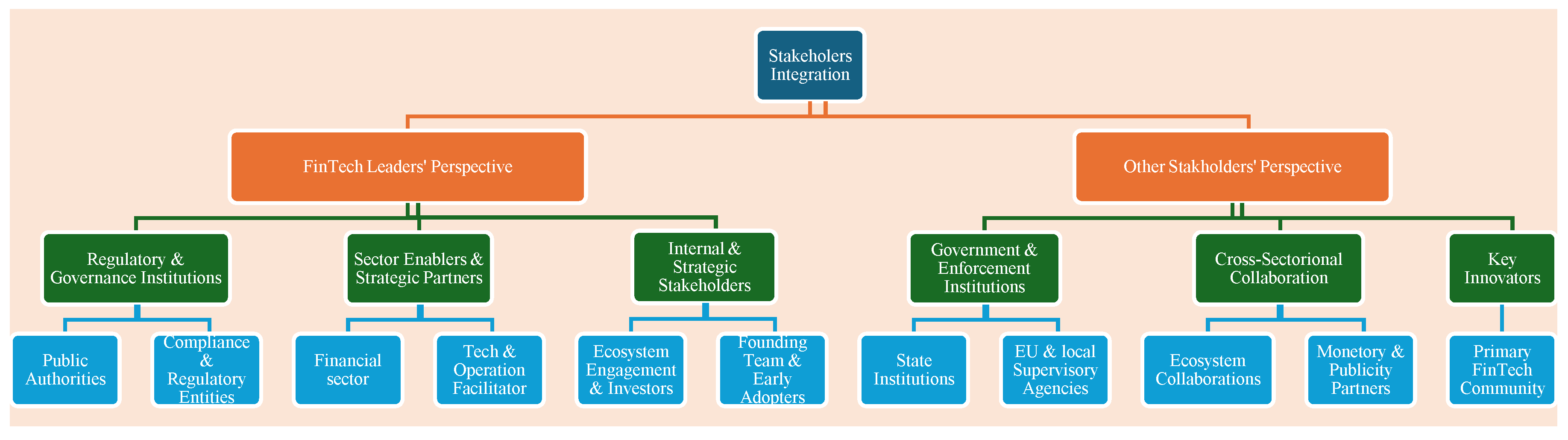

Ecosystem Component |

FinTech Key Responses | Non-FinTech Key Responses |

| Stakeholder Integration | • Regulators are the most fundamental stakeholders for the guidelines structure and compliance testing. • In infrastructure development, traditional banks are perceived as both competitors and partners. • Friction continues on compliance interpretation. • Investors, boards and associations facilitate ecosystem growth. • Sustained FinTechs act as orchestrators via partnerships and co-creation. |

• Regulators are crucial in both the working groups and the coordination at the EU level. • Although the banks and Associations support FinTech integration, they remain transactional. • Slow collaboration is due to stricter bank rules. • Integration among stakeholders is limited to shallow operational links. • Focus on compliance is greater than co-creation. |

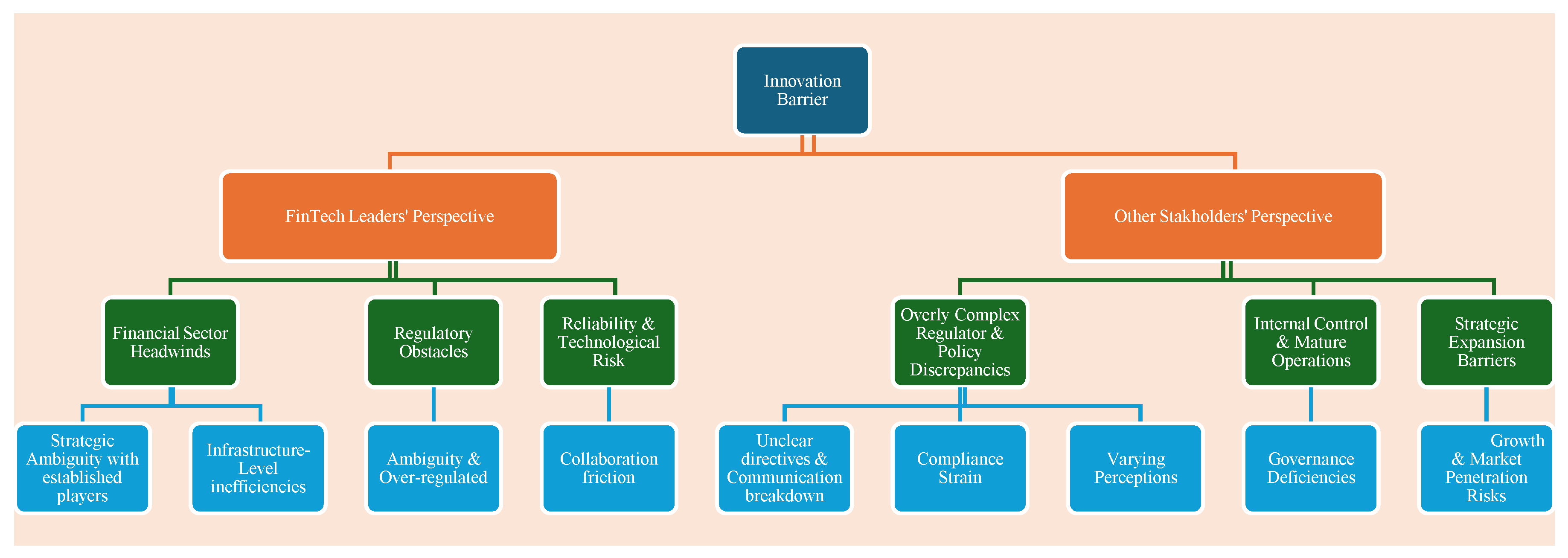

| Innovation Barrier | • Unclear relationships of FinTech with traditional businesses limit scaling. • Ambiguous regulations and their high integration costs result in slow innovation. • Regulatory ambiguity limits cross-border growth. • Lack of trust influences FinTech partnerships and reputation. • Compliance burden hinders new FinTech market entrants. |

• Uncertain and varying rules and their communication are highlighted by regulators. • Risk-averse approach of the regulators creates friction. • Compliance is perceived as expensive, time-consuming, and overwhelming. • Need for specialized compliance staff in FinTech increases costs. • Regulatory ambiguity is the prime barrier. |

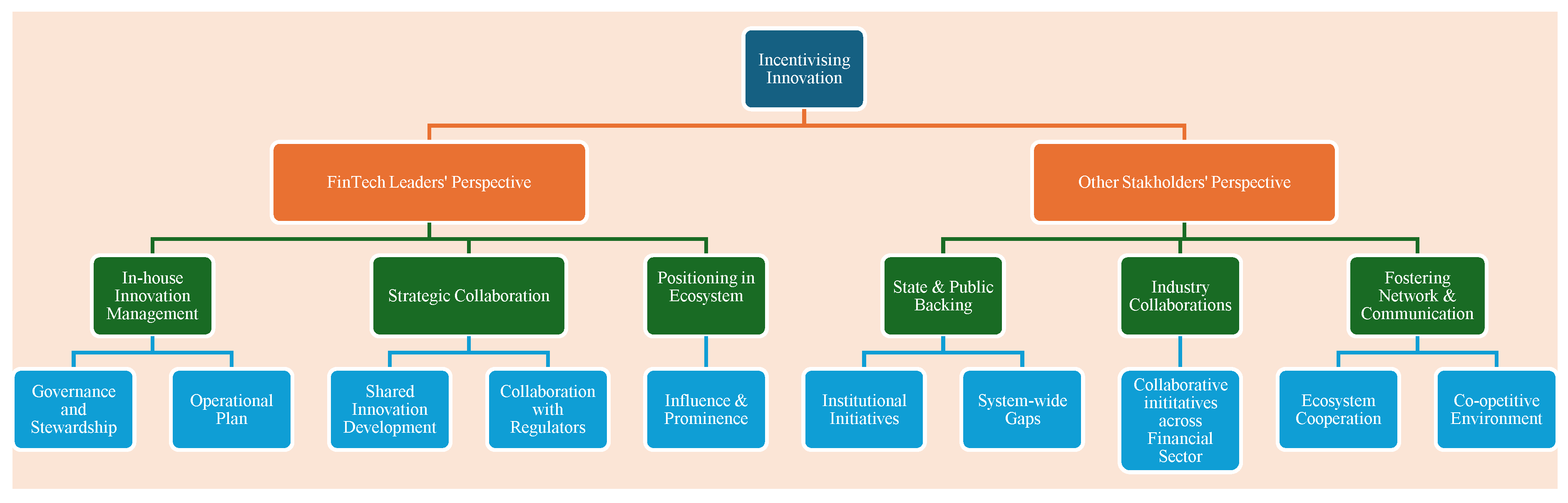

| Incentivizing Innovation | • Most functions are maintained in-house to maintain speed and compliance. • External partnership restricted because of low trust in regulation. • Regulatory support, though, exists; nevertheless, it is slow and inflexible. • Industry recognition encourages continuity. • Mature FinTechs switch from niche innovators to the leaders of the ecosystem. |

• Collaborations are not enough to incentivize innovation. • Sandboxes tend to be more reactive rather than collaborative. • Supervisory focus confines co-creation. • Regulatory instruments are also reactive, not proactive. • Need for deeper industry partnerships. |

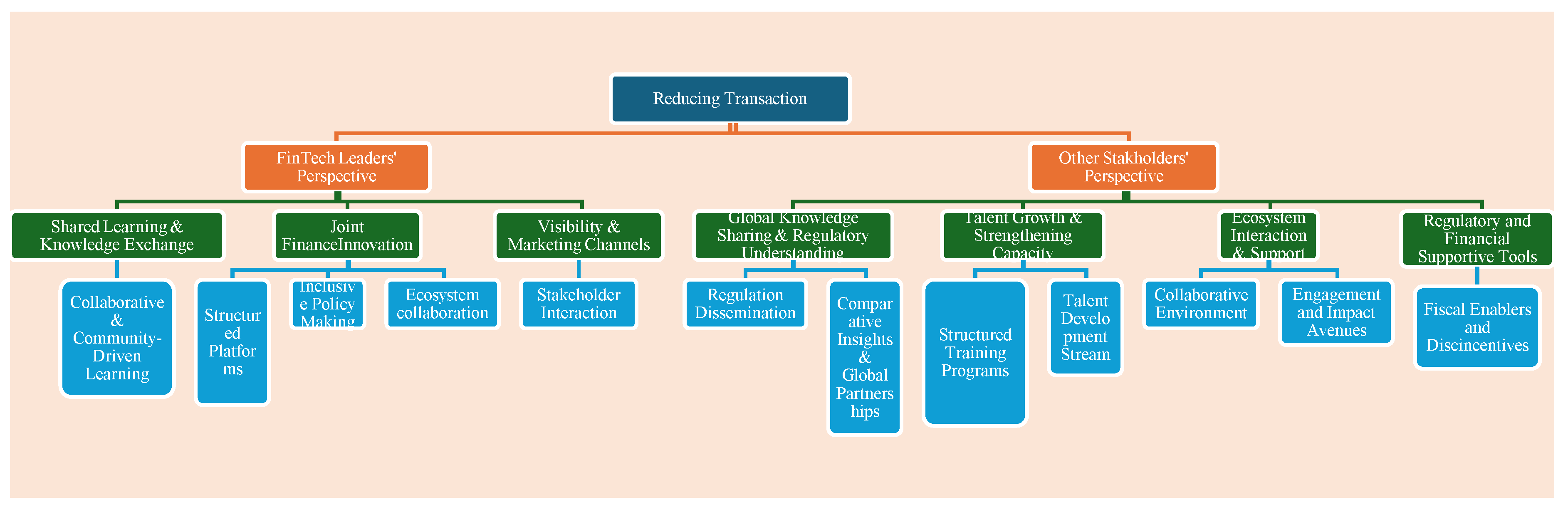

| Reducing Transaction Cost | • Shared systems are essential with banks and regulators to improve and synchronize AML / KYC functions. • Repetition and blurred rules waste resources. • FinTechs creäte joint templates and checklists to shorten onboarding processes. • Cross-institution co-operation helps in reducing duplication. • Efficiency leads to cost reduction. |

• to reduce errors, Clear rules, improved infrastructure and staff training are essential • Emphasis on clarity over cutting costs. • For smooth implementation, hiring expert staff is fundamental • Tax breaks reassure low-cost models. • Policy simplification is reviewed often at the institutional level. |

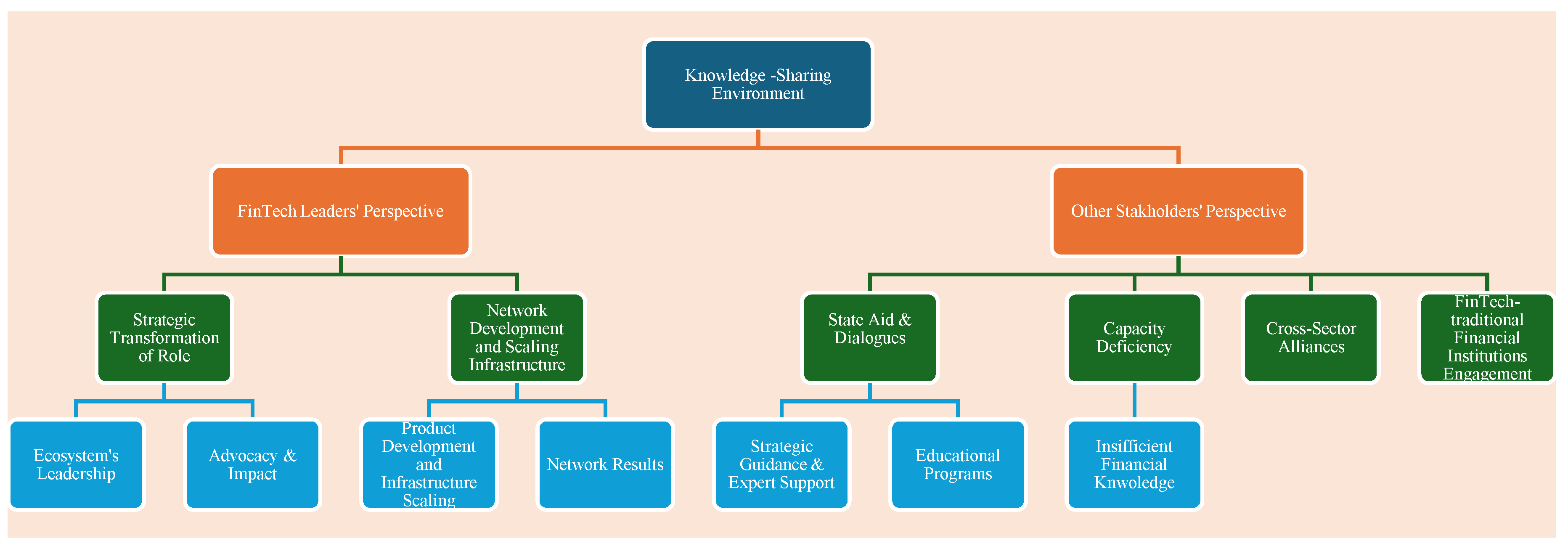

| Knowledge-Sharing Environment | • Knowledge exchange is largely informal and partner-driven; therefore, it has limited impact. • Systematic learning and institutional follow-up are limited. • Though events increase visibility, they do not increase infrastructure capacity. • Gaps exist in consistent learning platforms for FinTech. • Co-learning is essential with regulators. |

• Forums and working groups provide feedback and updates. • Institutions conduct the training in-house. • Sector-specific education programs are unavailable despite public education programs. • The sharing of Policy-driven knowledge is mostly top-down. • Iterative feedback loops are limited. |

| Value Chain Component | FinTech Key Responses | Non-FinTech Key Responses |

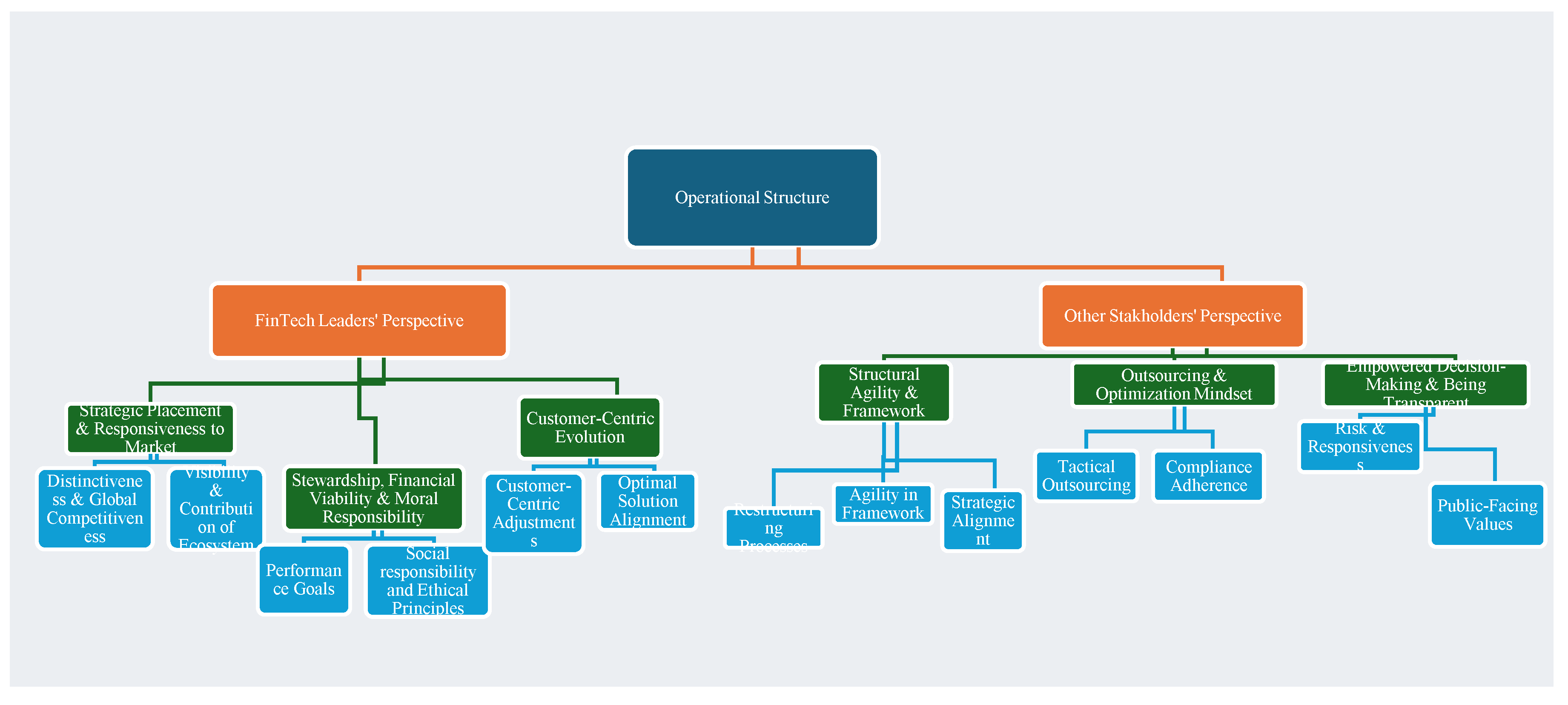

| Operational Structure | • Expand and diversify platforms for both global and local. • Trust and visibility are built by using awards and recognition. • The Main Aim is to increase profits and scalability, along with reducing costs. • Respect community-centric and ethical stewardship. • Emphasis on agility, which is customer-centric. |

• Adopting agile methods and AI tools to remain aligned with FinTech models. • To remain efficient and compliant, outsource non-core functions to FinTechs. • Cultural change in regards to customer focus. • Faster adoption is possible with reduced bureaucracy. • Encourage collaborative agility. |

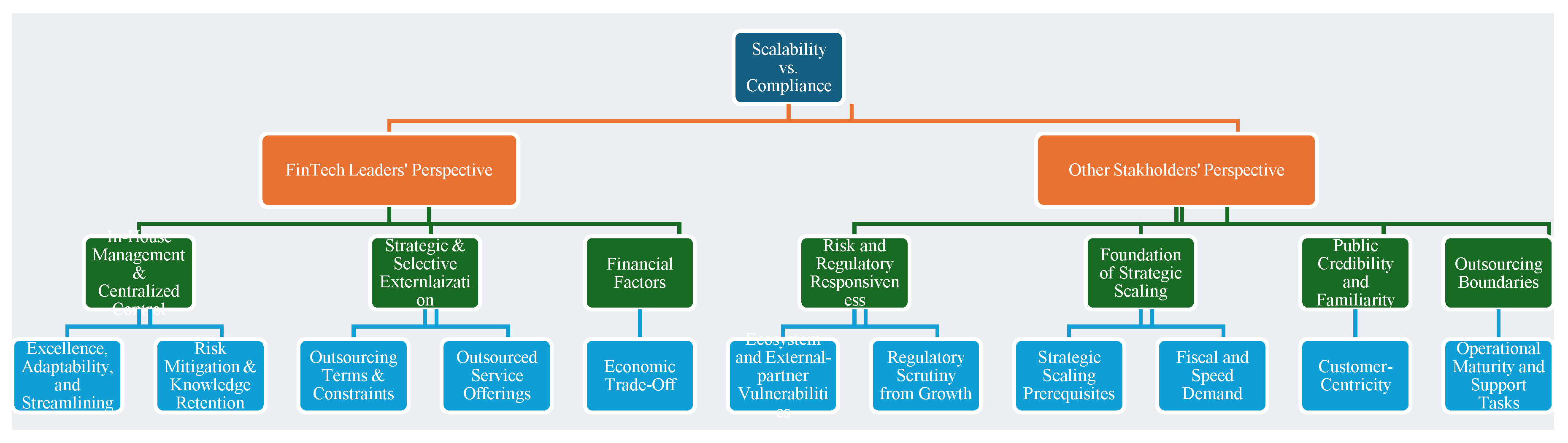

| Scalability vs Compliance | • Core operations in-house to maintain control and efficiency. • Outsource specific tasks (like legal documentation) whilst preserving integrity. • Restrict over-dependence on third parties to restrict regulatory exposure. • Selective outsourcing maintains responsiveness. • Compliance rooted in growth strategy. |

• Unease regarding third-party risk and negative reputational exposure. • Regulators tightly supervise FinTech growth to ensure user protection. • FinTech maturity enhances trust and alignment. • Outsourcing oversaw for systemic risk. • Require a balance involving innovation and security. |

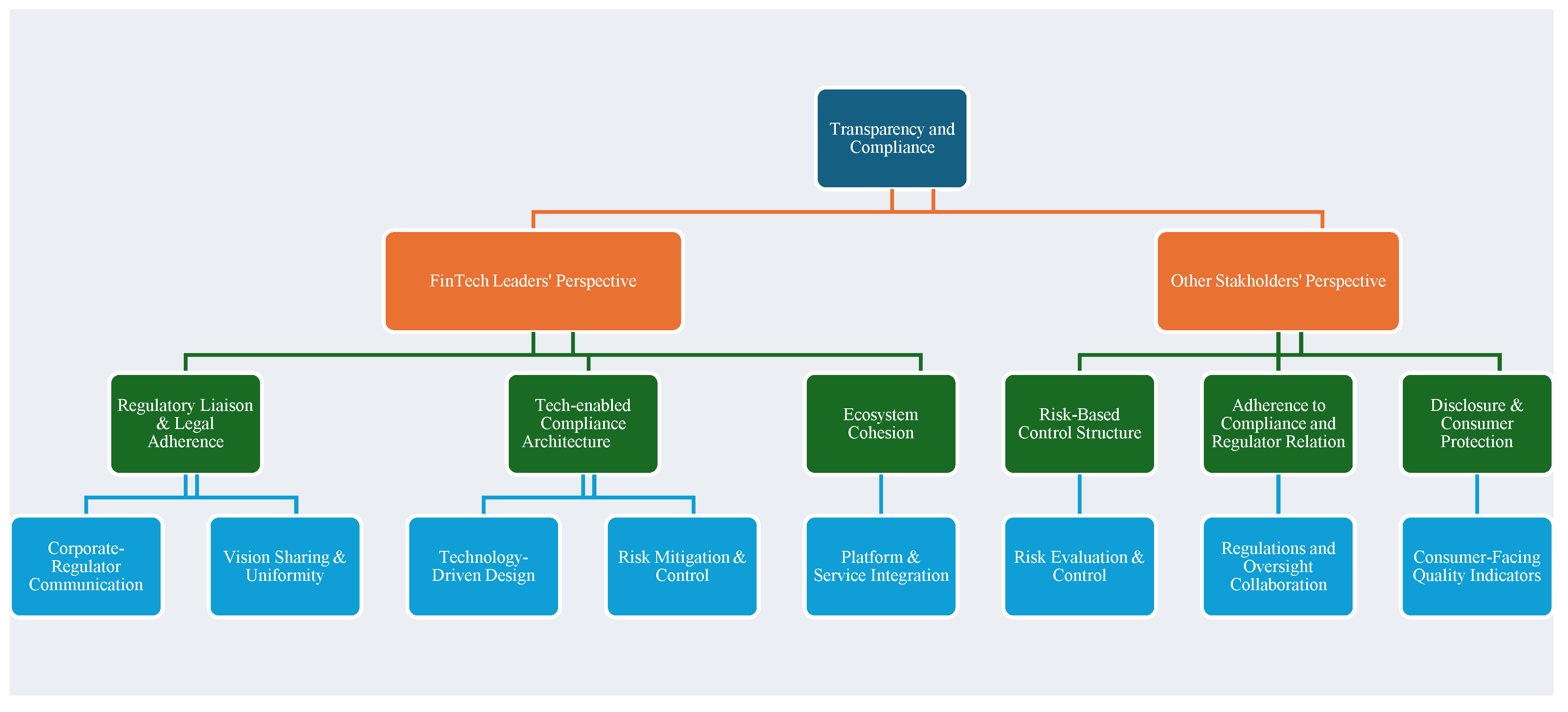

| Transparency & Compliance | • Compliance is a fundamental characteristic of FinTech products. • FinTechs use automation and architecture to internalize regulatory demands • adaptive governance supported by Internal audits and ecosystem co-operation. • Automation and AI enrich oversight efficiency. • Transparency enhances trust of the regulators in FinTech. |

• AI is designed for risk assessment and oversight Broader governance framework. • Associations observe inconsistent levels of compliance. • Emphasis on consumer protection and risk evaluation. • Mutual responsibility across institutions. • Culture of “doing things right.” i.e., risk-averse environment. |

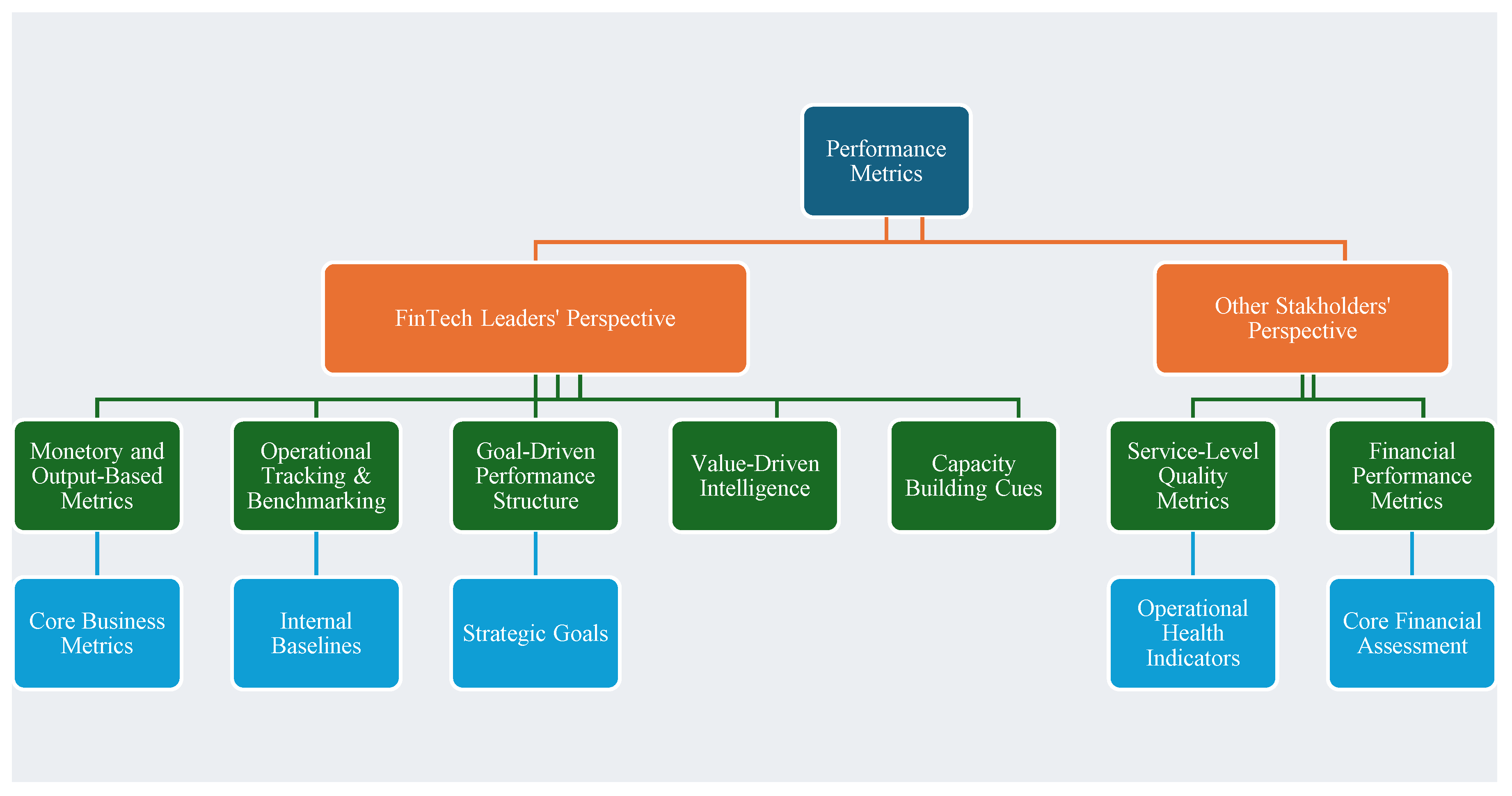

| Performance Metrics | • Track volume and revenue regularly to evaluate health. • Non-financial metrics (For instance, testing, client acquisition) are linked to infrastructure needs and behaviour. • Strategic goals are data-driven and adaptable. • KPIs apprise partnership feasibility and trust. • Metrics indicate sustainability and maturity. |

• For partnership and governance, KPIs and SLAs are used. • Performance transparency builds trust. • Metrics demonstrate sustainability to partners and associations. • Indicators help to evaluate the health of the ecosystem. • It is encouraged to have shared benchmarking. |

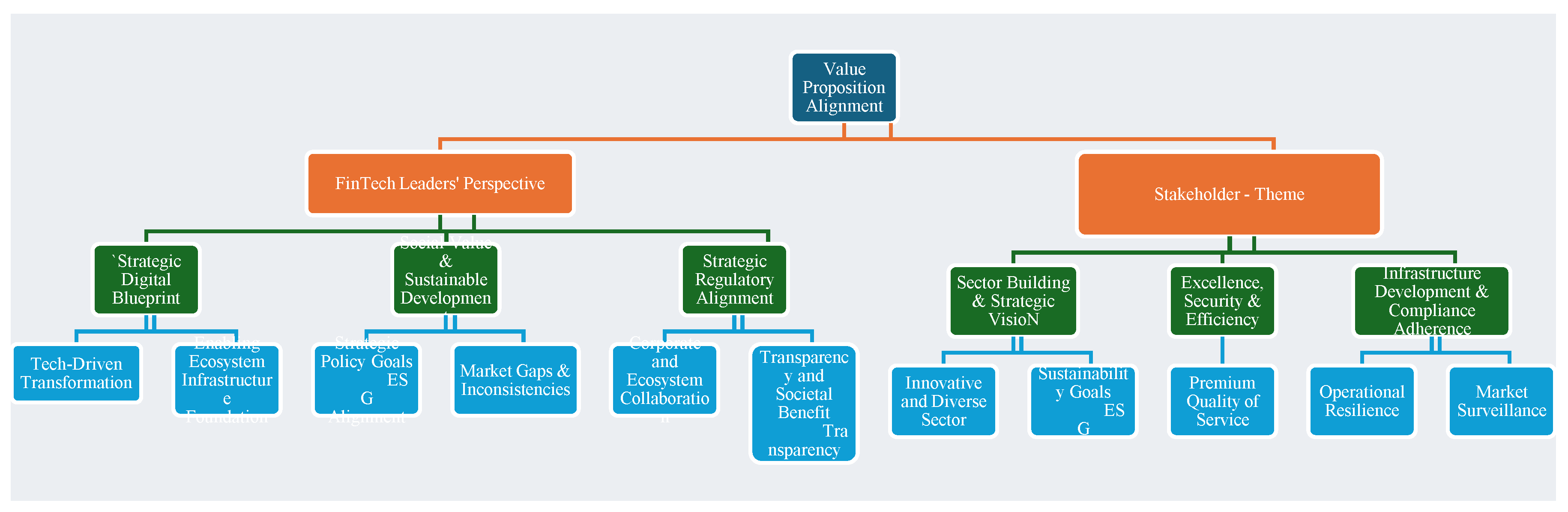

| Value Proposition Alignment | • For modularity and quick market response, Digital strategies are embedded in core models. • Cloud-based structures, which are scalable, line up with ESG goals. • Co-operation with policymakers guarantees recognition along with compliance. • Alignment supports scalability and resilience. • Flexibility persists as a core differentiator. |

• For Digital Euro development and Open Finance, Operational infrastructure is prioritized. • Stability comes with policy alignment with policy and ESG frameworks. • Social fit and regulatory trust are vital for scaling. • FinTechs are presumed to be partners in the implementation of the policy. • Market access barriers lead to misalignment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.