1. Introduction

This paper examines the economic viability of the exposed human warfighter under contemporary conditions of sustained attrition. It does not argue for the elimination of soldiers, the displacement of human command authority, or the abandonment of ethical or legal constraints in warfare. Rather, the analysis is confined to the cost structure governing exposure at the highest risk layer of combat and the conditions under which that exposure is allocated. The focus is strictly economic, how replacement speed, sustainment burden, and loss under attrition shape operational viability. Claims of effectiveness in this paper refer to cost efficient dominance under sustained loss, not tactical superiority, doctrinal preference, or moral valuation.

The central thesis of this paper is as follows. The exposed human warfighter is economically non-viable under conditions where low cost, rapidly replaceable systems achieve equivalent or superior effects at a fraction of the cost. This claim is not contingent on technological novelty, doctrinal innovation, or changes in human capability, but on replacement arithmetic under sustained loss. It arises from the arithmetic of replacement, sustainment, and loss. Human warfighters require prolonged training, continuous logistical support, and incur political and strategic cost when lost. By contrast, machine systems at the exposure layer are designed for disposability, incur minimal idle cost, and can be replaced at industrial speed. When a system costing hundreds of dollars can reliably destroy assets costing millions, or neutralize trained personnel whose replacement requires months or years, the governing variable is no longer skill, bravery, or platform sophistication, but cost curves under attrition. Doctrine cannot override this asymmetry. Valor cannot compensate for it. The mathematics of replacement governs regardless of intent.

This paper develops that argument through an economic analysis of attrition and replacement, grounded in observable battlefield evidence from the ongoing war in Ukraine. The objective is not prediction, but recognition of an already emergent structural shift in how military effectiveness is determined under sustained conflict. This analysis does not treat Ukraine as an exceptional case due to unique technology, doctrine, or national characteristics. Rather, Ukraine represents the first sustained, industrial scale conflict conducted under conditions of persistent surveillance, precision strike, and rapid unmanned system regeneration. These conditions are not unique to the Ukrainian theater; they are structural features of contemporary peer and near-peer conflict environments. The relevance of Ukraine lies not in its specificity, but in its role as the first observable instance in which cost, replacement speed, and attrition economics dominate exposure allocation at scale.

2. Cost Asymmetry

Once unmanned systems operate as a primary attrition mechanism, the governing variable of force viability shifts from platform survivability to exchange arithmetic under sustained loss. The relevant question is no longer whether a system can survive engagement, but whether it can be replaced at a rate that preserves operational capacity once contact occurs.

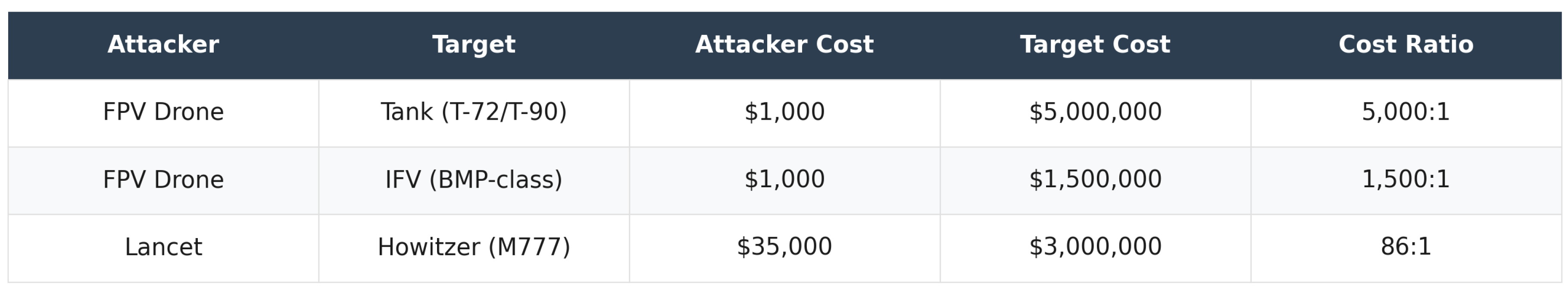

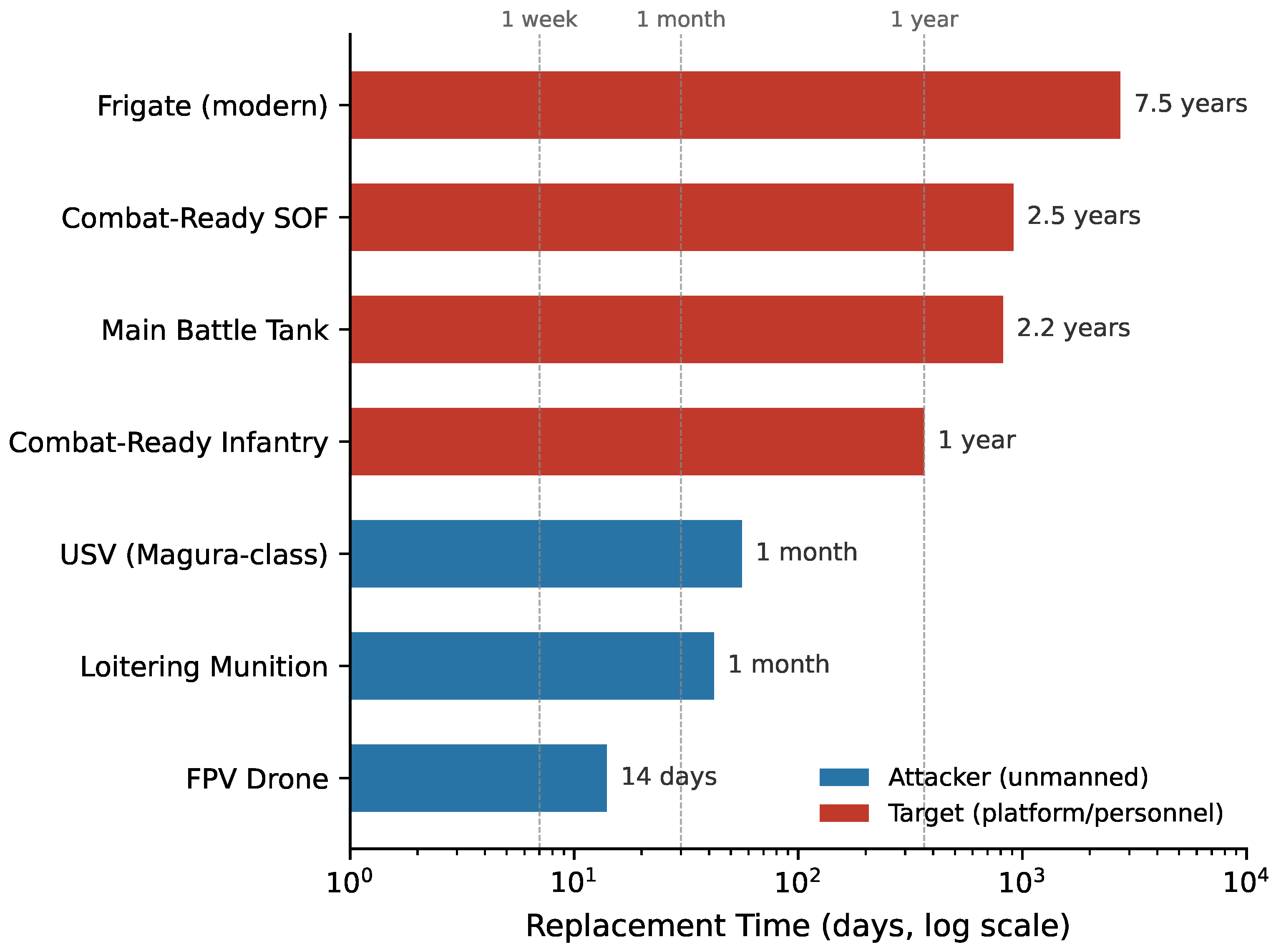

Figure 1 illustrates representative attacker-target relationships observed in contemporary land warfare within the Ukraine theater. The figure isolates the economic structure of exposure at the point of contact, comparing systems designed for disposability against platforms designed for preservation. The relationships shown do not assume perfect effectiveness, uninterrupted access, or uncontested conditions. They instead describe the relative cost structure governing loss once engagement occurs.

As shown in

Figure 1, a first person view (FPV) drone with an upper bound cost estimate of approximately

$1,000 can destroy or mission kill armored platforms valued between

$1.5 million and

$5 million, yielding exchange ratios ranging from 1,500:1 to 5,000:1. Higher end loitering munitions exhibit lower but still attacker favored ratios, approximately 86:1 against modern artillery systems. These ratios remain decisive even under conservative assumptions. High failure rates, interception, electronic countermeasures, or premature losses do not negate the underlying arithmetic. An attacking system that succeeds only a small fraction of the time preserves economic advantage so long as the cost of failure remains negligible relative to the cost of defender loss. Systems designed for disposability tolerate failure without compounding strategic penalty. By contrast, defended platforms embed costs beyond the loss of hardware. Destruction or mission kill of armored vehicles and artillery systems compounds the loss of trained crews, maintenance capacity, and replacement timelines measured in months or years. As a result, defenders are forced into a cost escalation loop in which increasingly expensive protective measures are deployed to counter systems whose defining advantage is that they do not require survival to remain effective.

Under sustained attrition, this exchange structure renders human centered exposure at the highest risk layer economically misallocated. The issue is not the elimination of human involvement in warfare, but the reassignment of human roles away from positions where loss rates are governed by replacement arithmetic rather than tactical skill.

Figure 1 therefore does not predict outcomes; it explains why, once unmanned systems dominate the attrition layer, their primacy becomes structurally persistent. Cost asymmetry establishes the economic efficiency of unmanned systems relative to their targets; however, efficiency alone does not determine battlefield impact. For economic asymmetry to translate into operational effect, the attacking platform must account for a substantial share of realized losses. Confirmed platform destruction data from the Ukraine theater provide an empirical basis for evaluating whether this condition is met.

Publicly available loss databases based on visual confirmation provide a conservative lower bound on equipment destruction. The Oryx project, which requires photographic or video evidence for each recorded loss, has documented more than 23,500 pieces of Russian military equipment destroyed, damaged, abandoned, or captured since February 2022 (Oryx, 2022). This total includes over 4,200 tanks, approximately 9,400 additional armored fighting vehicles, and more than 2,000 artillery systems (Mykhailenko, 2025). These figures intentionally undercount actual losses, as they exclude any destruction not captured on visual media; however, they are widely cited by defense institutions due to their transparency and methodological consistency.

Independent defense analyses indicate that unmanned aerial systems account for a majority of these confirmed losses. The Royal United Services Institute, synthesizing field interviews conducted in November 2024 and January 2025, reports that tactical UAVs, particularly FPV drones and loitering munitions, currently account for approximately 60-70% of damaged and destroyed Russian systems (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). This assessment is corroborated by a leaked Russian Armed Forces manual on FPV countermeasures, which attributes up to 70% of Russian personnel and equipment losses on all fronts to Ukrainian kamikaze drones. A separate analysis by the OSW Centre for Eastern Studies places the figure higher, estimating that drones are responsible for nearly 85% of enemy military targets destroyed along active front line sectors (Nieczypor and Matuszak, 2025). When combined with the cost relationships presented earlier, these attribution figures permit an illustrative calculation of aggregate exchange asymmetry. If 4,000 confirmed tank losses are attributed conservatively at 65% to drone systems, approximately 2,600 tanks were destroyed by unmanned platforms. At an average replacement cost of $4.5 million per T-90M and a conservative FPV expenditure of $1,000 per successful strike, the implied exchange exceeds $11 billion in destroyed armor against less than $3 million in drone expenditure, assuming one drone per kill. In practice, multiple drones are often expended per successful destruction; however, even at an order of magnitude increase in drone usage, the exchange remains decisively asymmetric. Even with reported FPV failure rates of 60-80 percent due to electronic warfare and operator skill variance (Watling & Reynolds, 2025), the volume and low cost of drone attacks make them remain the dominant source of Russian equipment attrition.

These figures do not imply exclusivity of effect. Artillery, anti-tank guided missiles, and manned aviation continue to contribute to equipment destruction, and RUSI analysts emphasize that UAVs are most effective when integrated with traditional fires (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). The data instead establish that unmanned systems now constitute the dominant single mechanism of platform attrition within the land domain. Once this dominance is established empirically, the cost asymmetries described earlier cease to be hypothetical and become operationally decisive. The cost differentials summarized in

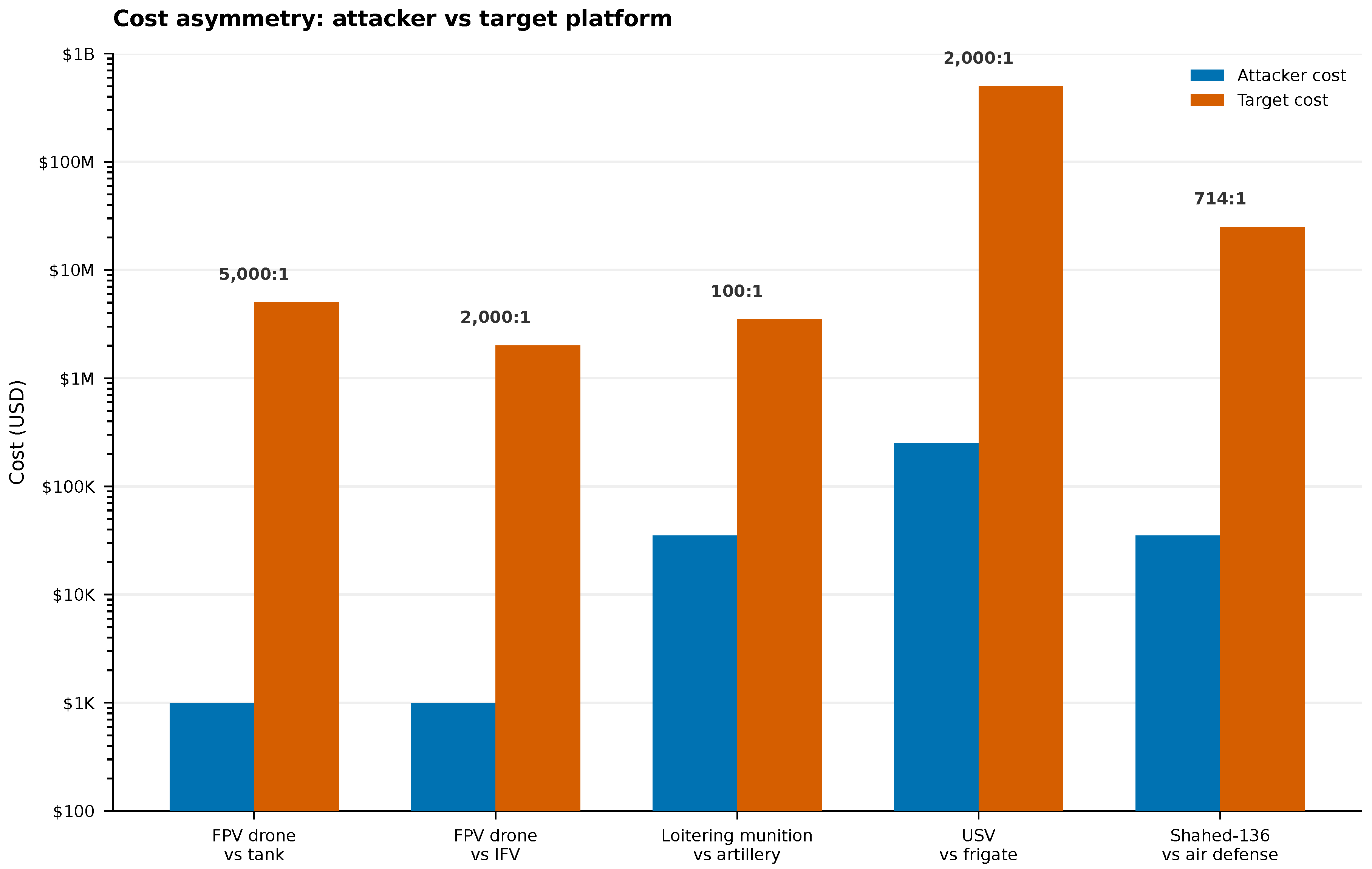

Figure 1 span multiple orders of magnitude, a scale that resists intuition when presented in tabular form.

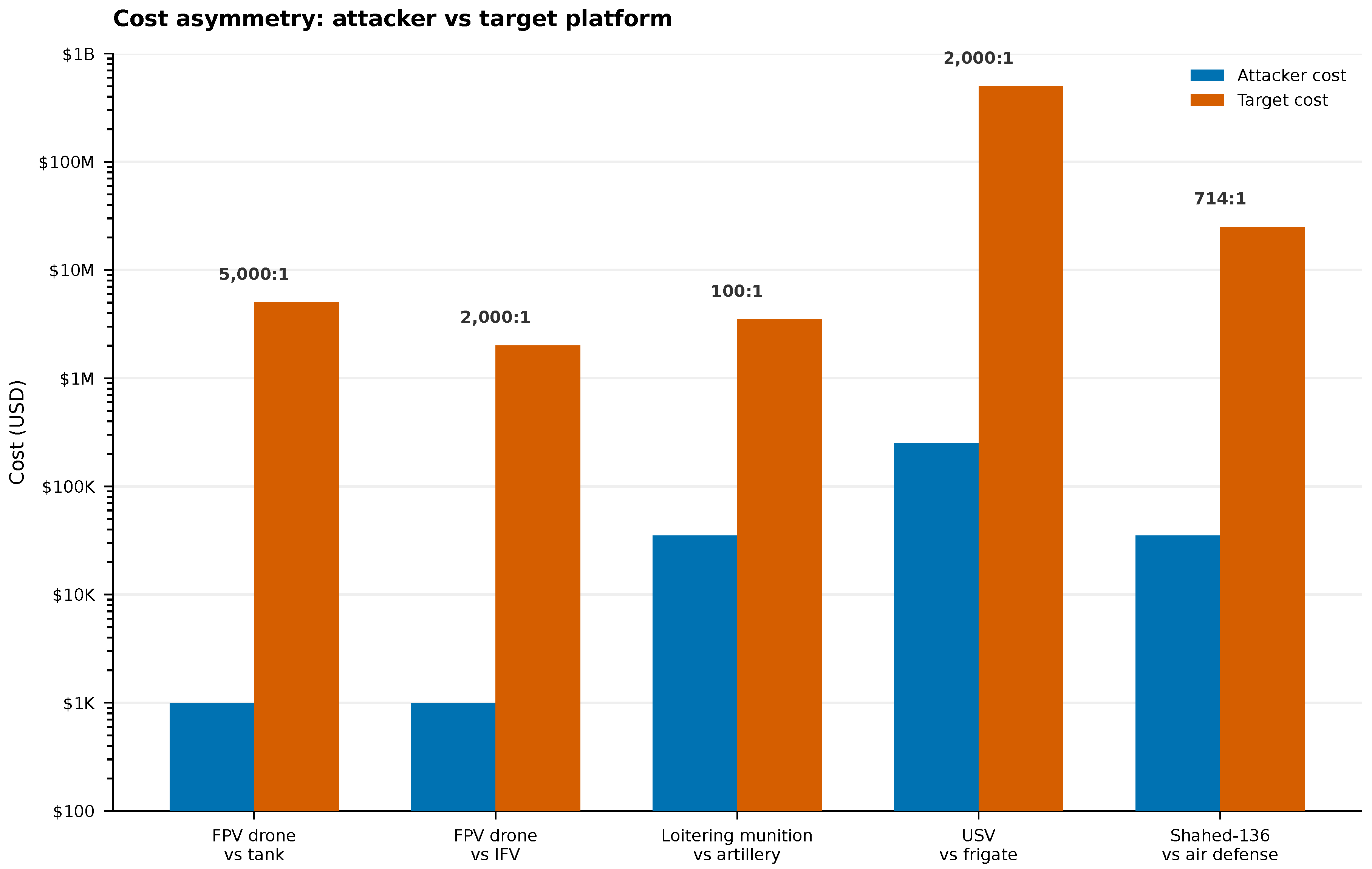

Figure 2 visualizes these asymmetries on a logarithmic scale, illustrating the structural disparity between attacker expenditure and target replacement cost across land, maritime, and air defense domains. The ratios shown represent static cost relationships prior to any consideration of effectiveness or attribution. Whether such asymmetries translate into battlefield advantage depends on demonstrated lethality, which the following section evaluates using verified loss data.

The cost ratios illustrated in

Figure 2 have implications that extend beyond procurement efficiency. A single T-90M tank, valued at approximately

$4.5 million, represents the same capital expenditure as more than 4,500 FPV drones at

$1000 per unit. A Bradley M2A4 infantry fighting vehicle, at approximately

$4.35 million, corresponds to a similar quantity. These relationships do not reflect incremental savings or marginal optimization; they reflect order of magnitude asymmetries that fundamentally alter the structure of attrition. A state that deploys a single armored platform concentrates financial capital, trained personnel, and operational risk into one target. A state that deploys thousands of expendable machine systems distributes that risk across a population of assets whose individual loss carries negligible strategic consequence. Under such conditions, battlefield dominance no longer requires the preservation of platforms or the protection of crews at the point of contact. Equivalent resources may instead be converted into large inventories of low cost systems capable of saturating defensive coverage, exhausting countermeasures, and imposing cumulative losses through repeated contact. The loss of hundreds or even thousands of drones does not degrade combat power in the same manner as the loss of a single crewed platform. Exposure is absorbed by material rather than personnel, and replacement occurs at industrial rather than human timescales. In this configuration, the removal of the warfighter from the highest-attrition layer is not a doctrinal preference or an ethical concession; simply a consequence of arithmetic. Once cost exchange favors quantity over survivability, crewed platforms at the forward edge transition from force multipliers to liabilities.

The cost asymmetries observed in land warfare do not diminish in the maritime domain; they intensify. Naval platforms concentrate capital, trained personnel, and strategic value into individual hulls whose loss cannot be rapidly absorbed or replaced. When low cost unmanned systems are capable of reaching and disabling these platforms, the same arithmetic that governs armored attrition on land reappears at sea with amplified consequences. The Black Sea theater provides a direct empirical example of this dynamic, where a force without a conventional navy imposed decisive losses on a modern fleet through systems designed for disposability rather than survivability. Ukraine entered the 2022 conflict with no meaningful surface fleet, having lost the majority of its naval vessels during the 2014 annexation of Crimea. Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, by contrast, comprised approximately 74 warships at the outset of hostilities, including the flagship Moskva, a Slava-class guided missile cruiser valued at approximately $750 million (Forbes Ukraine, 2022; Landen, 2022). By March 2024, Ukrainian forces had destroyed or disabled roughly one third of this fleet using a combination of domestically produced Neptune anti-ship missiles and Magura V5 unmanned surface vehicles (Shapps, 2024; Dickinson, 2024). The sinking of the Moskva on April 14, 2022, required only two R-360 Neptune missiles, each costing approximately $1.5 million, yielding a cost-exchange ratio on the order of 250:1 (Tuzov, 2023; Interesting Engineering, 2025). The patrol ship Sergey Kotov, valued at approximately $65 million, was sunk by five Magura V5 unmanned surface vehicles at an estimated unit cost of $250,000, producing a ratio exceeding 50:1 (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2024; Newsweek, 2024). The missile corvette Ivanovets, valued at $60-70 million, was destroyed by six Magura drones at a total expenditure of approximately $1.5 million, a ratio exceeding 40:1 (Jackson, 2024). These exchanges are not anomalous; they reflect a recurring pattern in which low cost, expendable systems neutralize capital intensive platforms through saturation and persistence rather than parity.

The strategic consequences extend beyond vessel counts. By June 2024, Ukrainian forces had executed at least 42 effective strikes against Russian warships using missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles, and unmanned surface vehicles, destroying 22 ships and boats while damaging an additional 20 (Black Sea Institute, 2024). The British Ministry of Defence assessed the Black Sea Fleet as functionally inactive by March 2024, prompting the relocation of remaining operational vessels from Sevastopol to Novorossiysk to reduce exposure (Shapps, 2024). Ukraine, a nation without a conventional navy, achieved sea denial against a major naval power, reopened commercial shipping corridors for agricultural exports, and eliminated the credible threat of amphibious assault against Odesa. The instruments of this outcome were not destroyers or submarines but subsonic cruise missiles costing under $2 million per unit and explosive-laden drone boats costing under $300,000 each. The Montreux Convention prevents Russia from reinforcing its Black Sea Fleet through the Turkish Straits, rendering these losses effectively irreplaceable for the duration of hostilities (Legion Magazine, 2024). The decisive factor is not tactical ingenuity but regeneration asymmetry. A state capable of producing unmanned naval strike systems in weeks holds a structural advantage over a state that requires years to replace a single surface combatant.

3. Human Warfighter Economics

The economic viability of the exposed human warfighter is constrained not by tactical performance but by regeneration limits imposed by training, sustainment, and replacement. Unlike platforms or unmanned systems, human combatants represent a non-manufacturable asset whose availability is bounded by biological, institutional, and political constraints. These constraints define the upper limit of force regeneration under sustained attrition, and they explain why the exposed warfighter has become the limiting factor in modern combat operations.

The cost of producing a combat ready soldier begins with recruitment and initial training. Peer reviewed analysis places the cost to recruit, train, and move a U.S. Army soldier to first operational assignment at approximately $60,000 per soldier, excluding downstream sustainment and equipment costs (Niebuhr et al., 2013). This figure covers only the pipeline from civilian to basic assignment; it does not account for the additional investment required to produce a functioning member of a combat unit. When total system costs are calculated, including pay, benefits, retirement accrual, training, equipment, and support personnel allocation, the annual cost per light infantry soldier rises to approximately $138,000 per year (Kirejczyk and St. Jean, 1993). A 2015 Congressional Budget Office analysis found that the total annualized cost to the federal government per uniformed servicemember, including deferred compensation and benefits, was approximately $135,200 (CBO, 2015). These figures establish that even a basic infantry soldier represents a six figure annual investment before any combat deployment occurs.

Training timelines compound the cost constraint. U.S. Army Basic Combat Training requires ten weeks, followed by Advanced Individual Training ranging from four weeks to over six months depending on occupational specialty (TRADOC, 2025). A soldier assigned to a combat unit is not operationally ready upon completion of initial training; integration into a functioning squad or platoon requires additional months of collective training, field exercises, and certification cycles. The total time from enlistment to combat ready status for a conventional infantryman is approximately 6 to 12 months. For specialized roles, the timeline extends significantly. U.S. Army Special Forces candidates require 18 to 24 months to complete the full qualification pipeline, including language training, specialty courses, and culmination exercises (Military.com, 2012). SOF members receive lengthy and costly training, making retention of qualified personnel a high priority; these investments are not recoverable upon loss (Asch et al., 2019).

Once trained, the human warfighter incurs continuous sustainment costs that persist regardless of combat activity. Annual personnel expenditures include base pay, housing allowance, subsistence allowance, healthcare, retirement accrual, and support infrastructure. For a mid-career enlisted soldier (E-5 with four years of service), annual compensation exceeds $66,000 before accounting for deployment allowances, special pays, or indirect support costs (DFAS, 2024). When institutional overhead is included, the Department of Defense expends approximately $14 billion annually on training alone, distributed across a force of approximately 1.3 million active duty personnel (Winkler & Steinberg, 1999). These costs are recurrent and scale linearly with force size. Unlike unmanned systems, which incur minimal cost while idle and no cost after loss, the human warfighter generates continuous expenditure from enlistment through separation or retirement.

Human replacement is fundamentally rate limited. Soldiers cannot be manufactured, stockpiled, or rapidly regenerated. Approximately 30% of U.S. Army personnel leave the service before completing their initial contract, with the highest-attrition rates occurring among infantry personnel (Marrone, 2020). Each early departure represents a total loss of training investment with no residual capability transfer. Replacement throughput is constrained by recruiting capacity, training pipeline bandwidth, instructor availability, and political consent for mobilization. Losses therefore compound across time rather than resetting through production. The training pipeline cannot be surged without degrading output quality, and quality degradation in combat personnel produces downstream costs in casualties, mission failure, and unit cohesion collapse. By contrast, FPV drones and similar unmanned systems can be produced in days or weeks, stored indefinitely, and replaced without political or social constraint. Ukrainian industry increased monthly FPV production from 20,000 units in January 2024 to over 200,000 units by December 2024, a tenfold increase in twelve months (Harper, 2025). Ukraine plans to produce up to five million drones in 2025, equivalent to more than 400,000 units per month (Bondar, 2025). This rate of production is structurally impossible for human combatants. No nation can produce 400,000 trained soldiers per month. The regeneration asymmetry is absolute.

Human casualties carry political costs that unmanned system losses do not. Research on casualty sensitivity demonstrates that public support for military operations is shaped by the intersection of perceived mission value and human cost (Gelpi, Feaver, & Reifler, 2009). Democratic governments face electoral constraints when casualty rates exceed public tolerance thresholds, and these thresholds have declined over time. Contemporary warfare has been characterized as “post-heroic,” reflecting reduced societal acceptance of battlefield deaths compared to earlier eras (Luttwak, 1995; Shaw, 2005). This political cost functions as an operational constraint; commanders cannot sustain operations that produce casualties at rates exceeding domestic political tolerance, regardless of tactical or strategic necessity. Unmanned systems impose no such constraint. The loss of a $1000 drone generates no political cost, no casualty notification, no media coverage, and no electoral consequence.

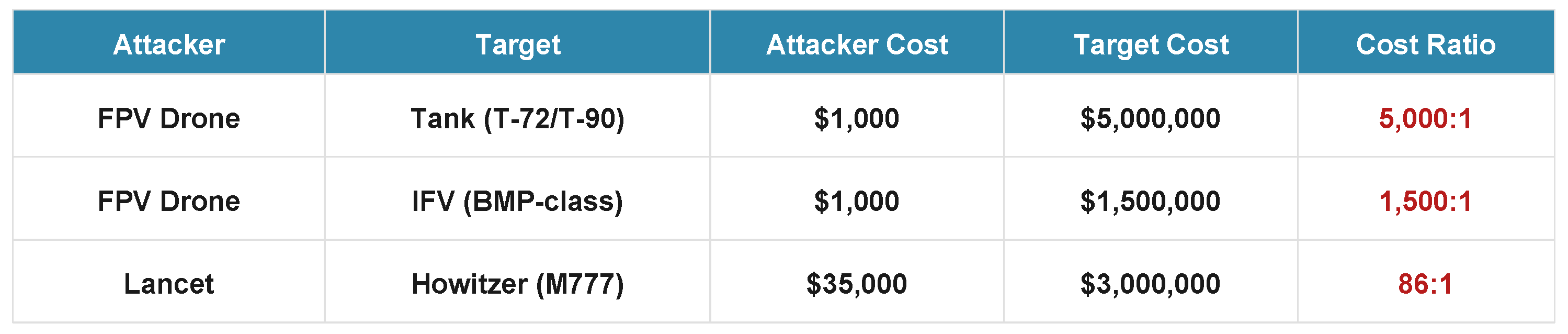

Figure 3 summarizes the conservative cost asymmetry between an exposed infantry soldier and a low cost FPV drone operating in the same exposure layer.

At the exposure layer, a single infantry loss represents the irreversible expenditure of 6 to 12 months of training investment, continuous sustainment cost, and political capital. The loss of an FPV drone represents a marginal material expense with no downstream obligations and no political consequence. Under sustained attrition, force regeneration is governed by the slowest and most constrained asset. In modern combat environments characterized by persistent surveillance and precision strike, that asset is the exposed human warfighter. The cost asymmetry is not theoretical. By early 2025, tactical drones accounted for 60-70% of all Russian equipment destruction in Ukraine, compared to 30-40% from all other weapon systems combined (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). Captured Russian soldiers report that they “haven’t seen the soldiers of the other side at all on the front line”, only drones (Bondar, 2025). The battlefield has become an environment where exposure equals destruction, and the entity most vulnerable to exposure is the human being. A $1000 drone can eliminate a $100,000 soldier. A thousand drones cost $1,000,000 and can be fielded in weeks. A thousand soldiers cost over $100 million and require years to train. The arithmetic is decisive, for the cost of fielding 1,000 infantry soldiers, a force can produce and deploy 100,000 FPV drones. The exposed warfighter cannot compete at these ratios.

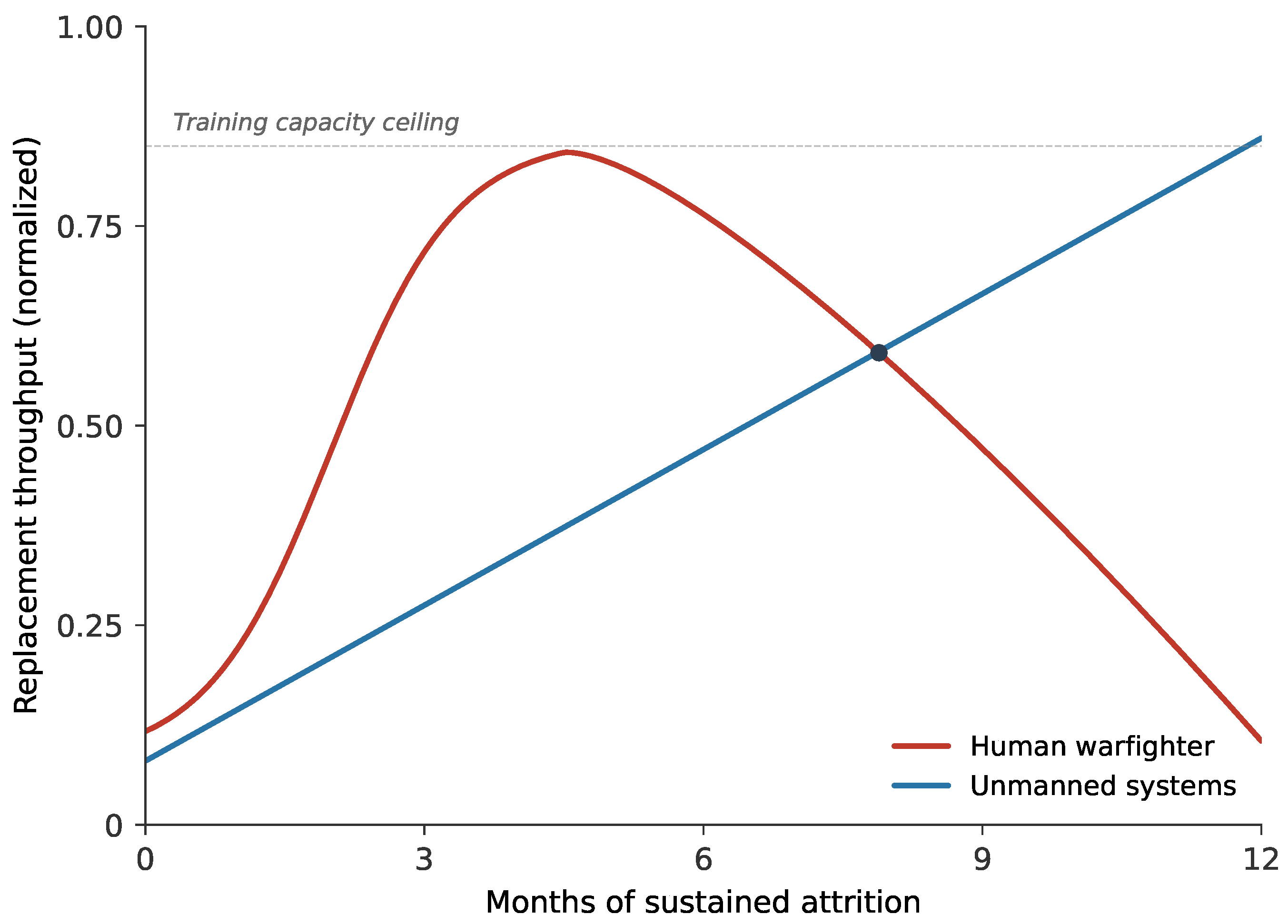

Attrition driven conflict is governed not by peak capability but by regeneration speed. When losses are sustained over time, the decisive variable becomes the rate at which a force can replace destroyed assets without degrading effectiveness. In this dimension, the exposed human warfighter is structurally disadvantaged. Unlike platforms or unmanned systems, human combatants are subject to biological, institutional, and political constraints that impose hard upper bounds on replacement throughput. These constraints cannot be relaxed without inducing secondary failure modes that compound attrition rather than offset it. Manufactured systems scale through capital investment, industrial capacity, and supply chain optimization. Production can be accelerated by adding shifts, subcontracting components, or simplifying designs. Human regeneration follows a fundamentally different process. Combat effectiveness requires a minimum threshold of physical conditioning, technical training, psychological screening, and collective integration. These requirements are not compressible beyond a lower bound without measurable degradation in survivability and unit performance. Accelerated training pipelines produce personnel with reduced tactical proficiency, increased casualty rates, and higher attrition (Dupuy, 1987). The regeneration curve for humans is therefore discontinuous, output quality collapses when throughput exceeds institutional capacity.

The ongoing war in Ukraine illustrates this constraint in real time. Russian mobilization efforts since late 2022 have repeatedly exceeded training and command capacity, producing formations characterized by limited cohesion, inadequate combined arms integration, and elevated loss rates. The UK Ministry of Defense assessed in November 2022 that newly mobilized Russian conscripts "likely have minimal training or no training at all," noting that Russia was "already stretched" in providing training for the estimated 300,000 personnel called up in the partial mobilization (Kyiv Post, 2022). The Institute for the Study of War reached similar conclusions, finding that Russian reserves “are poorly trained to begin with and receive no refresher training once their conscription period is completed,” and that the mobilization would “not generate significant usable Russian combat power for months” (Institute for the Study of War, 2022). By late 2025, ISW assessed that Russia remained “unable to build large enough reserves to be able to flood a sector of the front” without weakening other areas, despite meeting its 2025 recruitment targets (Institute for the Study of War, 2025).

Ukraine faces analogous constraints despite superior force quality, relying on extended training periods abroad and selective rotation policies to preserve combat effectiveness. Over 51,000 Ukrainian personnel have been trained through the UK-led Operation Interflex program, while the EU Military Assistance Mission has trained additional thousands across member states (Mills, 2025). Yet the pace of war compresses these timelines, most EU-based courses run for only one month, far shorter than the multiple months Western militaries devote to similar training, and collective training for squads, platoons, and companies runs for just one week each (Freedberg, 2024). Ukrainian officers have acknowledged that troops trained abroad arrive “less prepared” for actual combat conditions, with the Royal United Services Institute noting that this approach “shifts the risk from things going wrong at the training stage to things going wrong during live operations” (Koshiw, 2023). In both cases, manpower regeneration is rate limited by training infrastructure rather than population size.

Political tolerance further constrains human regeneration. Casualty sensitivity imposes an external ceiling on acceptable loss rates, particularly in democratic or semi-democratic systems. Empirical studies of public opinion demonstrate that support for military operations declines as human costs accumulate, even when strategic objectives remain unchanged (Gelpi, Feaver, and Reifler, 2009). This constraint operates independently of battlefield necessity. Commanders may possess the material means to continue operations, yet remain unable to do so due to domestic political pressure generated by sustained casualties (Luttwak, 1995). No equivalent constraint applies to unmanned systems, the loss of equipment does not trigger electoral backlash, morale collapse, or strategic retrenchment.

Historical precedent reinforces this logic. In the later phases of the First World War, multiple belligerents experienced manpower exhaustion prior to material exhaustion, forcing strategic retreat despite continued industrial output. French forces faced “shortages of manpower and morale” while British land forces were “exhausted and shrinking in numbers” by 1918, even as industrial production continued (Stevenson, 2011). Germany’s Spring Offensive ultimately failed not from lack of material but because “the defeat of the spring offensives of 1918 and the mass arrivals of American troops collectively broke the morale and manpower of the German army” (Stevenson, 2011). Replacement capacity, not battlefield valor or technological parity, determined operational endurance. Modern persistent surveillance environments intensify this dynamic. When exposure reliably produces destruction, attrition accelerates until the slowest regenerating asset governs the tempo of conflict.

Unmanned systems invert this relationship. FPV drones, loitering munitions, and unmanned surface vehicles can be produced at scale, stockpiled, and replaced on timelines measured in days or weeks. Their loss imposes no biological, political, or social cost. A February 2025 RUSI assessment found that tactical UAVs now account for 60-70% of damaged and destroyed Russian military systems, demonstrating the battlefield dominance of mass produced expendable platforms (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). Under sustained attrition, forces optimized around expendable unmanned systems retain operational elasticity, while forces dependent on exposed human warfighters accumulate irreversible losses. The result is not a contest of tactics but a contest of regeneration curves, and humans lose that contest by construction. This regeneration constraint can be visualized by comparing the replacement throughput of exposed human warfighters and unmanned systems under sustained attrition, as shown in

Figure 4.

4. Production Asymmetry

Attrition warfare is ultimately governed by regeneration speed. When losses are sustained over time, the decisive variable is not the marginal effectiveness of individual platforms, but the rate at which destroyed assets can be replaced without degrading force quality. Systems measured in days defeat systems measured in years under sustained attrition. This asymmetry is structural rather than tactical. No doctrine, training refinement, or battlefield adaptation can overcome a regeneration gap imposed by production timelines. Production timelines across modern military domains differ by multiple orders of magnitude. Main battle tanks require complex industrial inputs, specialized metallurgy, engine manufacturing, and trained crews. Even under accelerated wartime conditions, replacement timelines for armored vehicles are measured in eighteen to thirty six months (CIT, 2025; Frontelligence Insight, 2024). Modern surface combatants require substantially longer lead times, frigate-class warships demand specialized shipyards, long integration cycles, and extensive sea trials, producing replacement timelines measured in five to ten years (CRS, 2024; CBO, 2025). These timelines are not compressible without structural degradation to quality and safety.

Human regeneration is slower still. Combat ready infantry require six to twelve months from recruitment to effective deployment, while specialized forces require two to three years of continuous training. Replacement throughput is constrained by instructor availability, training infrastructure, selection attrition, and political consent for mobilization. These constraints impose a hard ceiling on regeneration capacity that cannot be scaled through capital investment alone (ISW, 2022; UK MoD, 2022). Once losses exceed training throughput, combat power declines irreversibly. By contrast, unmanned systems are governed by industrial rather than biological constraints. First person view (FPV) can be produced using distributed manufacturing, commercial components, and parallel assembly processes. Ukraine demonstrated a tenfold increase in monthly FPV drone production from approximately 20,000 units in early 2024 to over 200,000 units by the end of the year, with stated targets exceeding 4 million units annually (Harper, 2025; Havryliuk, 2025). Loitering munitions and unmanned surface vehicles exhibit similar scaling characteristics, with replacement timelines measured in weeks rather than years. The consequence of this asymmetry is compounding, each month of sustained attrition widens the regeneration gap between forces optimized for loss and forces dependent on slow regenerating assets. Tank fleets can be rebuilt over several years; naval fleets over decades; trained human expertise cannot be replaced at scale once losses exceed pipeline capacity. Under these conditions, operational tempo is governed by the slowest regenerating asset in the system. In contemporary conflict environments characterized by persistent surveillance and precision strike, that asset is the exposed human warfighter.

Production asymmetry therefore operates independently of tactical outcomes. Even forces that achieve local battlefield success incur long term disadvantage if losses are incurred in assets that cannot be regenerated at competitive speed. The asymmetry is not temporary, and it does not converge. It compounds until the slowest regenerating asset governs the pace and outcome of the conflict.

Figure 5 illustrates this asymmetry on a logarithmic scale. Under sustained drone mediated attrition, the side whose force structure relies on slow, politically constrained, or biologically limited assets will lose operational elasticity first.

5. The New Contact Layer

Traditional land warfare doctrine positions the infantry soldier as the first point of contact with the enemy. Reconnaissance patrols, probing attacks, and initial engagements historically required human exposure in order to locate opposing forces, fix their positions, and enable follow-on fires. Fire and maneuver doctrine assumed that exposure at the contact layer was an acceptable and unavoidable risk, justified by the necessity of human presence to observe, decide, and initiate combat. The infantry soldier absorbed first contact because no alternative system existed that could reliably perform these functions under contested conditions. In ISR-dense, peer-level battlespaces, this assumption no longer holds. Persistent surveillance from unmanned aerial systems, coupled with networked fires and rapid kill chains, has eliminated concealment as a stable condition for exposed movement. In these environments, the first contact is no longer established by human patrols but by unmanned systems conducting continuous reconnaissance, target acquisition, and initial engagement. Contact is no longer episodic or preparatory; it is persistent. The drone now occupies the exposure layer, detecting movement, fixing positions, and initiating fires before human elements can safely maneuver. Under these conditions, exposed movement without prior drone saturation produces predictable attrition rather than tactical advantage.

Operational testimony from both Ukrainian and Russian personnel confirms this shift. Captured soldiers have repeatedly reported that they no longer encounter enemy infantry at the front line, only drones operating overhead and at ground level, a pattern documented in field interviews conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (Bondar, 2025). These accounts align with institutional assessments by the Royal United Services Institute, which characterize the modern battlefield as one of continuous observation where any detectable movement is rapidly engaged (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). CSIS field reporting describes tactical adaptation in which vehicle movement within fifteen kilometers of the front line is difficult to impossible, forcing infantry to march to positions under persistent drone observation rather than conduct traditional mounted maneuver (Jensen, 2025). The doctrinal implication is not the removal of humans from warfare but their repositioning, the exposed human warfighter is no longer the tip of the spear; the drone swarm occupies that role. Human functions shift rearward to command, judgment, accountability, coordination of fires, and remote operation. This is not a model of humans supported by drones, but drones supported by humans. Infantry doctrine built on fire and maneuver presumes a contact layer that no longer exists under conditions of persistent ISR and precision strike. Forces that continue to position humans at the exposure layer will experience accelerated attrition without compensating operational benefit. In modern combat, presence does not require exposure, and exposure without unmanned dominance is a liability rather than a necessity.

The cost and regeneration asymmetries documented above are not confined to a single domain. Unmanned systems achieve favorable exchange ratios against infantry, armor, and naval assets simultaneously, a pattern without precedent in modern military history. Traditional weapons development produced platforms optimized against specific target classes: anti-tank missiles threatened armor, surface to air systems threatened aircraft, and torpedoes threatened naval vessels. Each capability required dedicated investment, training pipelines, and logistical infrastructure, and each imposed costs proportional to the complexity of the target. Unmanned systems invert this structure. A single FPV drone costing approximately one thousand dollars can destroy a combat infantryman representing over one hundred thousand dollars in training and equipment, a main battle tank valued between five and ten million dollars, or contribute to coordinated strikes against surface combatants valued in the hundreds of millions. Unmanned surface vessels costing two hundred thousand dollars have successfully engaged naval platforms exceeding that figure by three orders of magnitude. The implication is that no traditional asset class retains structural immunity from low cost attrition. Infantry, armor, and naval forces are all vulnerable to systems that can be manufactured faster, replaced cheaper, and deployed without the political and biological constraints that govern human centric force generation.

Figure 6 illustrates this convergence, unmanned systems do not favor one domain over another, instead achieving comparable cost-exchange advantages against infantry, armored, and maritime assets under sustained attrition.

6. Discussion

The preceding analysis invites several objections that warrant direct response. Anticipating these challenges clarifies the scope of the argument and distinguishes structural claims from overreach. The most common objection holds that humans remain essential to warfare and cannot be replaced by unmanned systems; this objection is correct but misdirected. The argument presented here does not claim that humans are unnecessary; it claims that humans are non-viable at the exposure layer, the zone of initial detection, targeting, and first contact, under conditions of persistent surveillance and precision strike. Command, judgment, accountability, coordination of fires, and remote operation remain human functions. The repositioning of human roles from the contact layer to command and oversight does not diminish their importance; it reflects an adaptation to conditions under which exposed presence produces predictable attrition without compensating tactical benefit. The ethical implication follows directly from the operational conclusion. If unmanned systems can perform the exposure function at lower cost and without loss of life, continued reliance on human forward doctrine imposes casualties that are no longer operationally necessary. Protecting warfighters by repositioning them behind the drone layer is not a concession to technology but an obligation that follows from the availability of effective alternatives.

A second objection holds that electronic warfare will restore balance by degrading drone effectiveness at scale. Electronic warfare imposes friction on unmanned operations; however, friction is not negation. The relevant calculation is not whether drones can be jammed or spoofed but whether jamming rates exceed production and deployment rates. If ten thousand drones are launched monthly and ninety percent are neutralized, one thousand still reach targets. At a unit cost of approximately one thousand dollars, the attacker retains favorable cost exchange even under severe attrition. Empirical adaptation supports this assessment. Ukrainian and Russian forces have responded to electronic warfare by developing fiber optic guided drones that are immune to radio frequency jamming, and AI-enabled terminal guidance systems that reduce operator dependence during the final approach (Watling & Reynolds, 2025). Electronic warfare shifts the attrition curve; it does not invert it. Crucially, unmanned systems do not require high per-unit effectiveness to remain operationally decisive. Attrition tolerance is a defining feature of disposable systems. When the cost of failure is negligible and replacement timelines are measured in days or weeks, effectiveness thresholds collapse from precision to sufficiency. A system that succeeds infrequently can still dominate attrition so long as loss rates remain economically absorbable and production exceeds neutralization. Electronic warfare therefore modifies the slope of the attrition curve but does not alter its governing structure.

A third objection notes that drones cannot hold territory, and therefore cannot achieve strategic objectives that require physical occupation. This objection conflates two separable phases of conflict. Combat and occupation are not identical; drones attrit defending forces during the combat phase, and human infantry occupy cleared terrain during the consolidation phase. The inability to occupy does not imply inability to dominate the engagement that precedes occupation. Ukraine’s control of Black Sea approaches illustrates this distinction. Without a surface fleet, Ukraine has denied Russia operational use of the western Black Sea through unmanned surface vessels and coastal defense systems, achieving strategic denial without territorial possession (Kaushal, 2024). The significance of this example lies not in Ukraine’s geography or force structure but in the demonstrated ability of unmanned systems to impose denial effects without platform parity. The relevant metric is not whether drones can plant a flag but whether they can render the battlespace untenable for opposing forces.

A fourth objection observes that Ukraine continues to lose ground despite fielding large numbers of unmanned systems, suggesting that drone warfare has not delivered strategic success. This objection conflates territorial metrics with sustainability metrics. Russia has gained ground while hemorrhaging equipment and trained personnel at rates that exceed regeneration capacity. Documented losses include thousands of armored vehicles, hundreds of aircraft, and casualty figures that have compelled repeated mobilization efforts under conditions of declining manpower quality (CSIS, 2025). Winning the map while losing the ledger is not a stable condition. The relevant strategic question is not who holds terrain on a given date but who can sustain attrition longer without exhausting the personnel and equipment pipelines that enable continued operations. The side that depletes its slow regenerating assets first loses operational flexibility regardless of territorial position.

A fifth objection holds that technology always produces countermeasures, and therefore the current asymmetry will be neutralized by defensive adaptation. This objection is historically accurate but does not support the inference that cost parity will be restored. Reactive armor, slat armor, cage modifications, active protection systems, and electronic warfare suites all represent countermeasures to drone threats; however, each adds cost and complexity to the defended platform without eliminating the threat. A main battle tank fitted with drone defense modifications remains vulnerable to saturation attacks, costs more to produce and maintain, and still faces an attacker whose losses are replaceable in days rather than years. Countermeasures narrow the asymmetry at the margin; they do not invert the structural advantage that expendability confers on the attacker. The history of armor-antiarmor competition supports this pattern. Reactive armor did not render antitank missiles obsolete, and active protection systems have not eliminated the threat from precision munitions. Each cycle raises costs on both sides while preserving the attacker’s advantage in replaceability.

The structural argument developed throughout this paper carries an ethical dimension that warrants explicit statement. If unmanned systems can saturate a contested zone, attrit defending forces, and clear fields of fire before human soldiers advance, then the continued deployment of exposed infantry into direct fire engagements is no longer a tactical necessity but a policy choice. That choice carries moral weight. The men and women who serve in uniform accept risk in defense of their nations; however, the obligation runs in both directions. States bear a corresponding responsibility to ensure that warfighters are not exposed to avoidable harm when effective alternatives exist. The cost required to saturate a battlespace with expendable unmanned systems and suppress targets prior to human movement is negligible when compared to the strategic, human, and institutional cost of a single servicemember killed or permanently wounded.This calculus has shifted further under contemporary conditions. Exposed human warfighters no longer face only rifles, artillery, and sporadic indirect fire; they now operate under persistent aerial surveillance and precision strike, where concealment provides no reliable protection. Under these conditions, doctrine that positions humans at the contact layer does not preserve combat effectiveness; it converts personnel into the slowest regenerating and most vulnerable asset in the battlespace. Such doctrine does not honor service through necessity. It expends lives in roles that machines can now perform. The dead cannot be regenerated, retrained, or replaced at scale. The question is not whether adaptation is desirable, but whether institutions will adapt before attrition forces the conclusion.

Reflection: If technology permits the saturation and clearance of contested zones without human exposure, what ethical framework justifies continued doctrine that places warfighters in direct fire when machines can absorb that risk instead?

7. Conclusion

The analysis presented in this paper demonstrates that the exposed human warfighter has become economically non-viable under conditions of sustained drone attrition. Across land, maritime, and air defense domains, cost asymmetries between unmanned systems and conventional forces now exceed 100:1, while regeneration timelines diverge by an order of magnitude or more. Manufactured systems can be replaced in days or weeks; trained human combatants require months or years. Political tolerance, biological limits, and institutional training capacity impose hard ceilings on human replacement that do not apply to unmanned platforms. Under these conditions, exposure at the contact layer becomes a liability rather than an asset.

The evidence supporting this conclusion is empirical rather than speculative. Since 2022, Ukraine has demonstrated the operational consequences of cost and production asymmetry at industrial scale. Tactical drones account for approximately 60-70 percent of confirmed Russian equipment losses. Ukrainian FPV production scaled from approximately 20,000 units per month to over 200,000 units per month within a single year. In the maritime domain, Ukraine degraded roughly one third of the Russian Black Sea Fleet without fielding a conventional navy, using unmanned surface vehicles and coastal strike systems measured in hundreds of thousands of dollars against platforms valued in the hundreds of millions. These outcomes are not projections or war gaming scenarios; they are observed results. The doctrinal implication follows directly. The exposure model must invert. Machines move forward; humans move back. Infantry doctrine built around fire and maneuver assumes concealment, limited surveillance, and tolerable exposure risk, conditions that no longer exist in a battlespace defined by persistent ISR and precision strike. The drone has become the first contact layer, responsible for reconnaissance, targeting, and initial engagement. Humans operate behind this saturation barrier, providing command, judgment, coordination, and accountability. Forces that continue to place humans at the exposure layer will experience accelerated attrition without compensating operational advantage.

The traditional warfighter role, as historically structured around direct exposure at the point of first contact, is no longer economically or operationally viable under contemporary conditions of sustained attrition. The human role in warfare remains essential. Command, judgment, moral accountability, and strategic decision making are irreducibly human functions and cannot be delegated to machines. What has changed is the allocation of risk at the contact layer. Where low cost unmanned systems can absorb exposure at scale, the continued placement of human bodies in that role no longer reflects operational necessity. The cost asymmetry is structural, the supporting evidence is empirical, and forces that fail to adapt their exposure models risk progressive loss of operational resilience under sustained conflict.

This analysis is not an argument against military service, sacrifice, or the individuals who serve, nor does it diminish the skill, courage, or necessity of human warfighters within historical or current doctrine. The empirical evidence and cost figures used throughout are drawn primarily from open-source reporting and institutional assessments related to the ongoing war in Ukraine, and the analysis is therefore scoped to domains in which sustained attrition, persistent surveillance, and unmanned system saturation are empirically observable at scale. It is not intended to address short-duration raids, punitive strikes, or limited-scope operations designed to achieve rapid tactical or political effects without entering a sustained attrition regime. It does not attempt to exhaustively model all aspects of warfare, including strategic air operations, nuclear deterrence, cyber conflict, or domains in which human presence remains structurally indispensable. The argument advanced here is structural and economic rather than moral or political. It evaluates how exposure at the point of contact is allocated under sustained attrition, and why, under contemporary conditions observed in Ukraine, replacement arithmetic and regeneration constraints now govern viability at that layer. Human warfighters remain essential to combat operations, command, judgment, coordination, and occupation; what is evaluated is not the relevance of the human role, but the economic and operational viability of placing human bodies at the highest-attrition exposure layer when effective machine alternatives exist. All percentage attributions represent conservative estimates derived from open source visual confirmation and institutional field reporting rather than comprehensive battlefield accounting.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No original datasets were generated for this study. All data referenced are drawn from publicly available open-source reporting and institutional assessments cited in the references.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spangle, R. On the Front Lines with Ukraine’s Night Bombers; Esquire, 16 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weichert, Brandon J. Russia’s T-90M tank nightmare

. In The National Interest.; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Artem, K. Lancet 3: Russia’s Spear in the Sky

. In Grey Dynamics; 1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Military Leak. US Army awarded BAE Systems $162 million contract for new M777 howitzer structures. MilitaryLeak.com. 11 May 2025.

- Oryx. Attack on Europe: Documenting Russian equipment losses. Oryx Blog. Accessed. 2022. (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Mykhailenko, D. Russia Has Lost Over 4,000 Tanks in Ukraine, Oryx Confirms With Visual Evidence; United24 Media, 29 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, J.; Reynolds, N. Tactical developments during the third year of the Russo-Ukrainian war; Royal United Services Institute, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nieczypor, K.; Matuszak, S. Game of drones: the production and use of Ukrainian battlefield unmanned aerial vehicles

. OSW Commentary 2025, no. 694. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. How cheap drones are transforming warfare in Ukraine

. In The Economist; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kudrytski, A.; Rudnitsky, J.; Safronova, O. How Ukraine’s drone arsenal shocked Russia and changed modern warfare

. Bloomberg 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Kyiv. Ukrainians capture Russia’s multi-million dollar T-90 tank in eastern sector

. Kyiv Post 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Minton, S. US Army equips first unit with modernized Bradley

. U.S. Army News 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, E. Russia Using Experimental ’Lancet’ Drones With New Guidance Systems: ISW

. Newsweek 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Lancet: The Russian kamikaze drone blunting Ukraine’s counteroffensive; RFE/RL, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, E. Ukraine’s Magura Naval Drones: Black Sea Equalizers

. Proceedings 2025, vol. 151(no. 9). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. Ukraine’s Drones Sinking Russian Warships; Newsweek, 6 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, J. India signs contracts to purchase 4 Admiral Grigorovich-class frigates from Russia

. The Defense Post, 20 November; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van Brugen, I. Russia Loses Five Air Defense Systems Worth $350M in a Day; Newsweek, 6 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Kyiv. Multimillion-Dollar Pantsir-S1 Missile Systems Guarding Police Department in Russian St. Petersburg, Guerrillas Say

. Kyiv Post, 27 August; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes Ukraine. Destroyed Russian navy missile cruiser Moskva worth $750 million; Forbes Ukraine, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Landen, X. Moskva warship’s sinking a $750 million loss for Russian military: Report

. Newsweek 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shapps, G. Defence Secretary oral statement for the second anniversary of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine

. In UK Government; 22 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, P. Russia’s retreat from Crimea makes a mockery of the West’s escalation fears; Atlantic Council, 16 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzov, B. How Neptune hit the Moskva. Kyiv Post, 23 April; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Interesting Engineering. The future of cruise missiles: What you need to know. In Interesting Engineering; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Russian patrol vessel sunk off the coast of occupied Crimea, Ukraine military claims; RFE/RL, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies. The Black Sea report: Losses of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea in 2022–2024; BlackSeaNews, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shapps, G.; @grantshapps. Putin’s continued illegal occupation of Ukraine is exacting a massive cost on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet which is now functionally inactive. X. 24 March 2024. Available online: https://x.com/grantshapps/status/1771868590318240021.

- Thorne, S. J. Russia’s Black Sea fleet falls back amid staggering losses

. Legion Magazine 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr, D. W.; Page, W. F.; Cowan, D. N.; Urban, N.; Gubata, M. E.; Richard, P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the U.S. Army Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS) program

. Military Medicine 2013, 178(10), 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defense Technical Information Center. Analysis of current light infantry soldier system costs; U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center, 1993; p. ADA265173. [Google Scholar]

- Kirejczyk, H. J.; St. Jean, D. Technical Report NATICK/TR-93/032; Analysis of current light infantry soldier system costs. U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center, 1993.

- Congressional Budget Office. CBO Publication 51012; Replacing military personnel in support positions with civilian employees. 2015.

- U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. TRADOC Pamphlet 600-4: The Soldier’s Green Book; Fort Eustis, VA, 26 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Military.com. Army Special Forces training. Military.com 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, B. J.; Mattock, M. G.; Hosek, J.; Nataraj, S. Assessing retention and special and incentive pays for Army and Navy commissioned officers in the Special Operations Forces; RAND Corporation, 2019; p. RR-1796-OSD. [Google Scholar]

- DFAS. 2024 military pay tables; Defense Finance and Accounting Service, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, J. D.; Steinberg, P. S. Making military education more effective and affordable; RAND Corporation, 1999; pp. Research Brief RB–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, J. V. Predicting 36-month attrition in the U.S. military; RAND Corporation, 2020; p. RR-4258-OSD. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S. Factory-to-frontline pipeline: How Ukraine’s 2025 drone surge is reshaping the battlefield. War Quants 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, G. C.; Bondar, K.; Bendett, S. The Russia-Ukraine drone war: Innovation on the frontlines and beyond [Event transcript]; Center for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, 28 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gelpi, C.; Feaver, P. D.; Reifler, J. Paying the human costs of war; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luttwak, E. N. Toward post-heroic warfare

. Foreign Affairs 1995, 74(3), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M. The new Western way of war; Polity Press: Cambridge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, T. N. Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat; Paragon House Publishers: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Kyiv. British defence intelligence update Ukraine. Kyiv Post, 5 November 2022; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for the Study of War. Russian offensive campaign assessment; Institute for the Study of War, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for the Study of War. Russian offensive campaign assessment; Institute for the Study of War, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C. Military assistance to Ukraine (February 2022 to January 2025); House of Commons Library, 2025; pp. Research Briefing CBP–9477. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, S. J. Pace of war shortens EU-based training for Ukrainian troops

. Defense One, 6 November; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koshiw, I. NATO training leaves Ukrainian troops underprepared for war; openDemocracy, 8 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, D. With our backs to the wall; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Conflict Intelligence Team. Russia capable of producing up to 300 T-90M tanks per year

. Militarnyi 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Insight, Frontelligence. Inside Russia’s 2024 military-industrial complex

. In European Security and Defence; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Research Service. CRS Report R44972; Navy Constellation (FFG-62) class frigate program. 2024.

- Congressional Budget Office. CBO Publication 60732; An analysis of the Navy’s 2025 shipbuilding plan. 2025.

- Havryliuk, I. Statement on Ukrainian drone production capacity

. In Ukrainian Ministry of Defense; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, B. Seven contemporary insights on the state of the Ukraine war

. In Center for Strategic and International Studies; 17 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal, S. Lessons for the Royal Navy’s future operations from the Black and Red Sea; Royal United Services Institute: Commentary, 26 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. G.; McCabe, R. Russia’s battlefield woes in Ukraine

. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 3 June; 2025. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Land platform cost asymmetry observed in the Ukraine theater. FPV drone costs reflect conservative upper bound estimates; median production costs are substantially lower (Spangle, 2024). Armored vehicle, loitering munition, and artillery costs are based on publicly available procurement and trade data (Weichert, 2024; Artem, 2024; Military Leak, 2025). All ratios are calculated using attacker-unfavorable assumptions.

Figure 1.

Land platform cost asymmetry observed in the Ukraine theater. FPV drone costs reflect conservative upper bound estimates; median production costs are substantially lower (Spangle, 2024). Armored vehicle, loitering munition, and artillery costs are based on publicly available procurement and trade data (Weichert, 2024; Artem, 2024; Military Leak, 2025). All ratios are calculated using attacker-unfavorable assumptions.

Figure 2.

Cost asymmetry between low cost machine systems and conventional military platforms. Ratio annotations represent rounded conservative midpoints across reported cost ranges rather than exact bar-derived quotients. FPV drone costs reflect Ukrainian procurement at approximately $300-$1000 per unit (The Economist, 2025; Kudrytski et al., 2025). Tank values represent T-90M acquisition at approximately $4.5 million (Kyiv Post, 2024; Weichert, 2024). IFV costs reflect Bradley M2A4 procurement at $4.35 million (Minton, 2022). Loitering munition costs represent Lancet-3 at approximately $35,000 (Cook, 2023; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2023). Artillery values reflect M777 howitzer costs at $2-$4 million (Military Leak, 2025). USV costs represent Magura V5 estimates at $250,000-$300,000 (Wertheim, 2025; Jackson, 2024). Frigate values reflect Admiral Grigorovich-class acquisition at $450-$500 million (Stocker, 2018). Air defense costs represent Pantsir-S1 systems at $13-$15 million (Kyiv Post, 2024; van Brugen, 2025). All ratios indicate cost-exchange advantage on a logarithmic scale prior to any consideration of effectiveness or attribution.

Figure 2.

Cost asymmetry between low cost machine systems and conventional military platforms. Ratio annotations represent rounded conservative midpoints across reported cost ranges rather than exact bar-derived quotients. FPV drone costs reflect Ukrainian procurement at approximately $300-$1000 per unit (The Economist, 2025; Kudrytski et al., 2025). Tank values represent T-90M acquisition at approximately $4.5 million (Kyiv Post, 2024; Weichert, 2024). IFV costs reflect Bradley M2A4 procurement at $4.35 million (Minton, 2022). Loitering munition costs represent Lancet-3 at approximately $35,000 (Cook, 2023; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2023). Artillery values reflect M777 howitzer costs at $2-$4 million (Military Leak, 2025). USV costs represent Magura V5 estimates at $250,000-$300,000 (Wertheim, 2025; Jackson, 2024). Frigate values reflect Admiral Grigorovich-class acquisition at $450-$500 million (Stocker, 2018). Air defense costs represent Pantsir-S1 systems at $13-$15 million (Kyiv Post, 2024; van Brugen, 2025). All ratios indicate cost-exchange advantage on a logarithmic scale prior to any consideration of effectiveness or attribution.

Figure 3.

Cost comparison between FPV drones, loitering munitions, and exposed conventional military platforms. Costs reflect representative upper bound attacker estimates and conservative target replacement values observed in the Ukraine theater.

Figure 3.

Cost comparison between FPV drones, loitering munitions, and exposed conventional military platforms. Costs reflect representative upper bound attacker estimates and conservative target replacement values observed in the Ukraine theater.

Figure 4.

Regeneration curves under sustained attrition. Human warfighter throughput (red) rises to a training capacity ceiling before declining as quality degrades under accelerated replacement demands. Unmanned systems throughput (blue) scales linearly with industrial investment. The crossover point (dot) marks the regeneration advantage inversion.

Figure 4.

Regeneration curves under sustained attrition. Human warfighter throughput (red) rises to a training capacity ceiling before declining as quality degrades under accelerated replacement demands. Unmanned systems throughput (blue) scales linearly with industrial investment. The crossover point (dot) marks the regeneration advantage inversion.

Figure 5.

Replacement timelines across military domains. Unmanned systems (blue) are measured in days to weeks; platforms and personnel (red) are measured in months to years. The logarithmic scale reveals a structural gap of one to two orders of magnitude between attacker and target regeneration speed. Replacement timelines are approximate and represent high end observed or reported regeneration intervals under wartime conditions. Values are conservative and illustrative of structural differences rather than precise procurement schedules.

Figure 5.

Replacement timelines across military domains. Unmanned systems (blue) are measured in days to weeks; platforms and personnel (red) are measured in months to years. The logarithmic scale reveals a structural gap of one to two orders of magnitude between attacker and target regeneration speed. Replacement timelines are approximate and represent high end observed or reported regeneration intervals under wartime conditions. Values are conservative and illustrative of structural differences rather than precise procurement schedules.

Figure 6.

Illustrative cost-exchange relationships between low cost unmanned systems and conventional military assets across land, maritime, and personnel domains. Values represent conservative estimated cost ranges and approximate exchange ratios observed under conditions of persistent surveillance and precision attrition, rather than exact battlefield accounting.

Figure 6.

Illustrative cost-exchange relationships between low cost unmanned systems and conventional military assets across land, maritime, and personnel domains. Values represent conservative estimated cost ranges and approximate exchange ratios observed under conditions of persistent surveillance and precision attrition, rather than exact battlefield accounting.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).