Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling Sites

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Isolation and Identification of E. coli

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.5. Genotypic Detection of Resistance Genes Using PCR

2.6. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation and Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.7. Bioinformatics and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

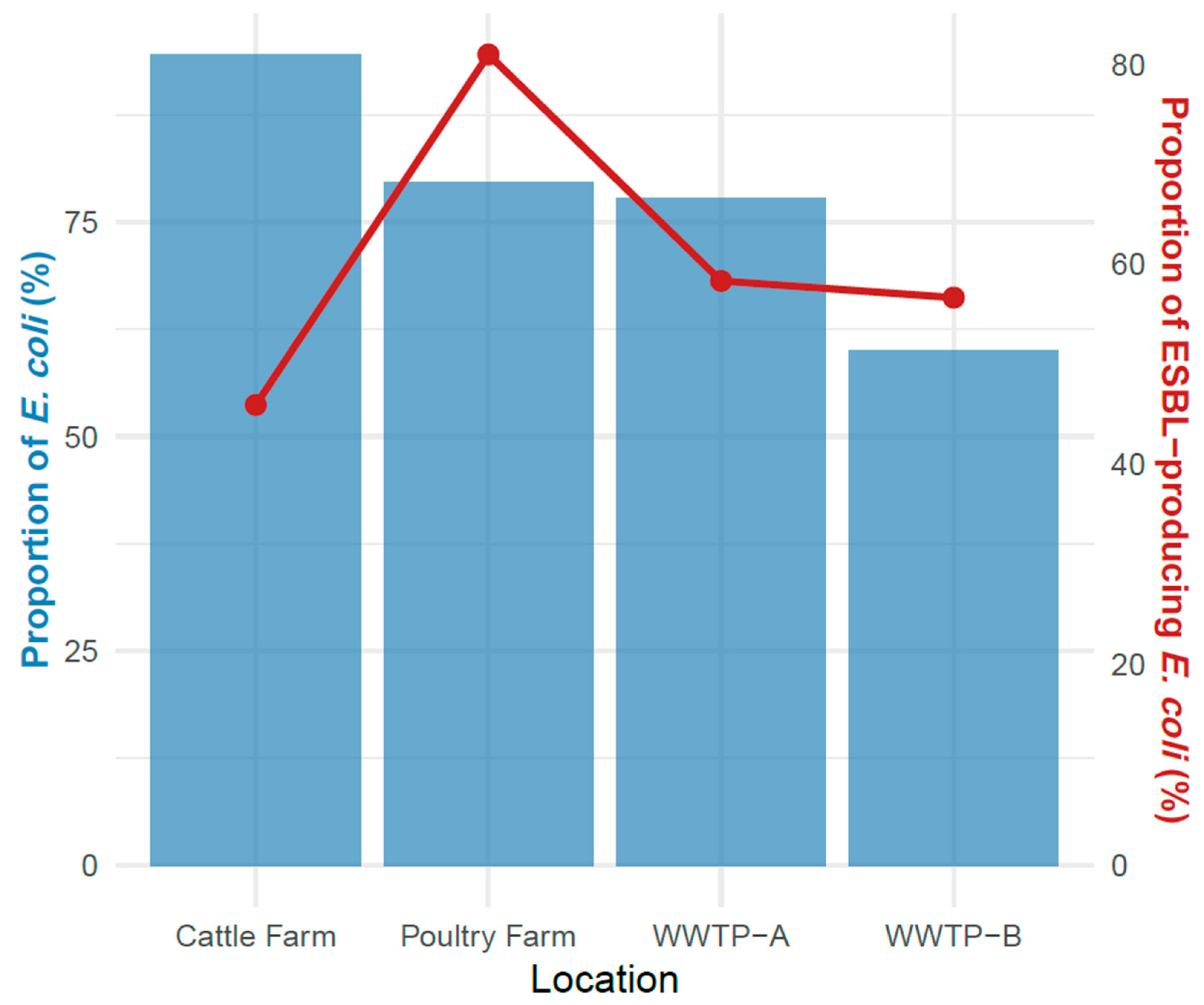

3.1. Prevalence of E. coli in Wastewater, Poultry, Cattle and Farm Environment

3.2. Detection of ESBL-EC Isolates

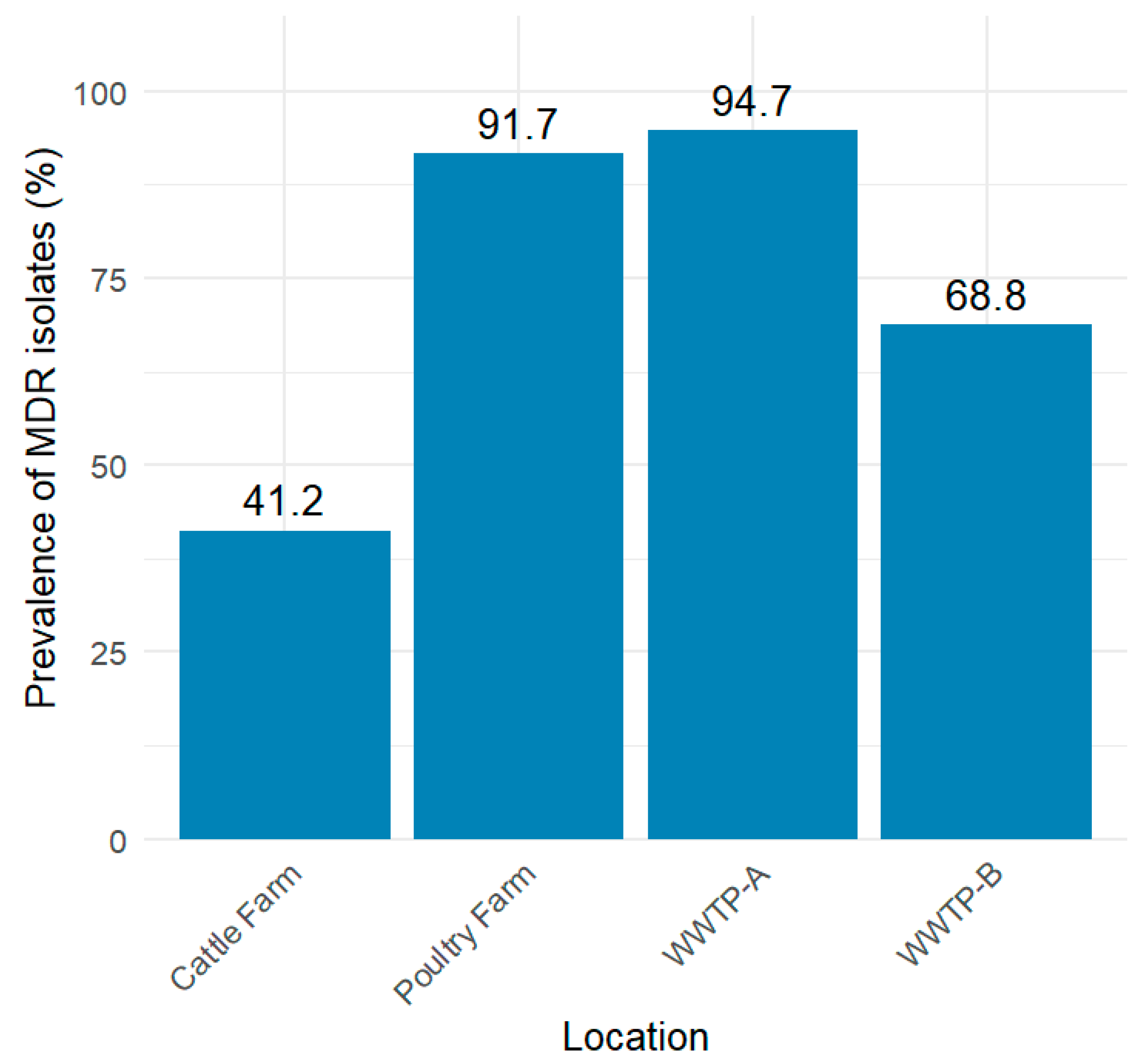

3.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of ESBL-EC Isolates

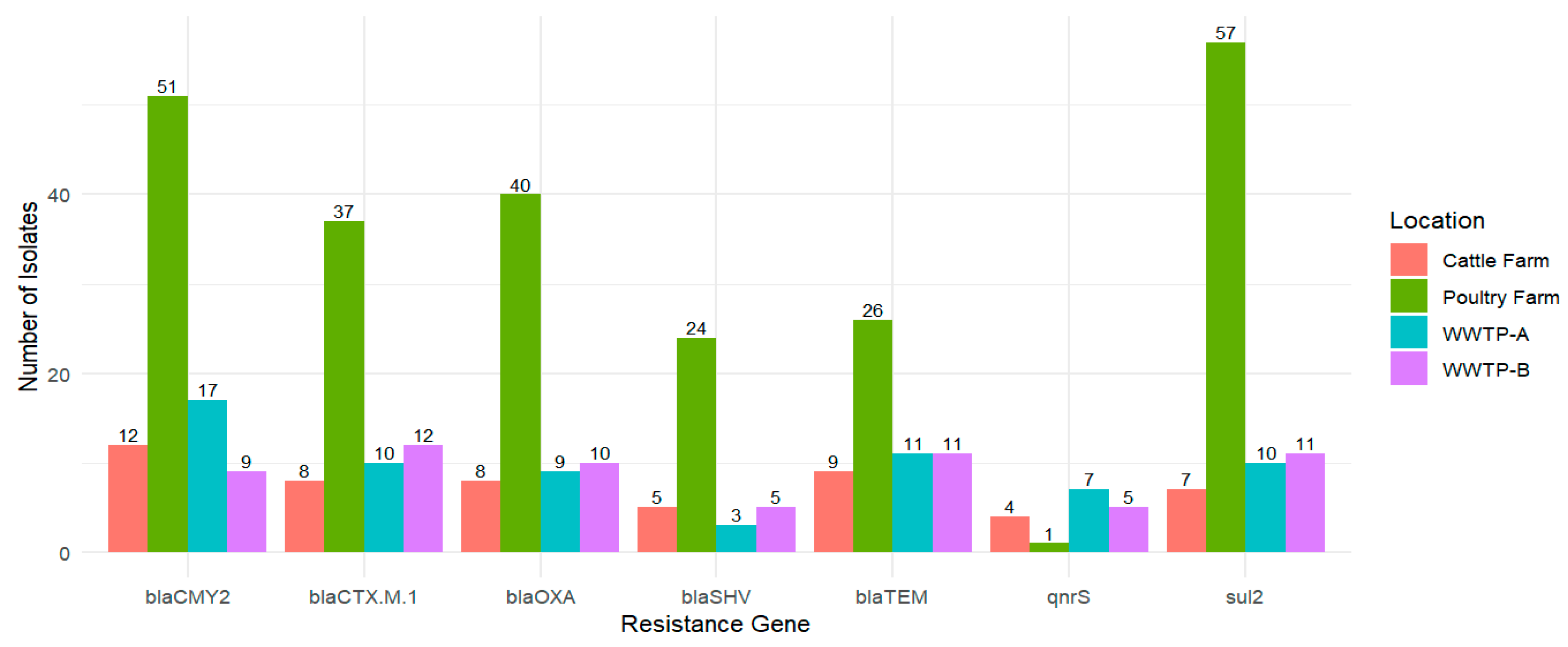

3.4. PCR-Based Detection of Resistance Genes

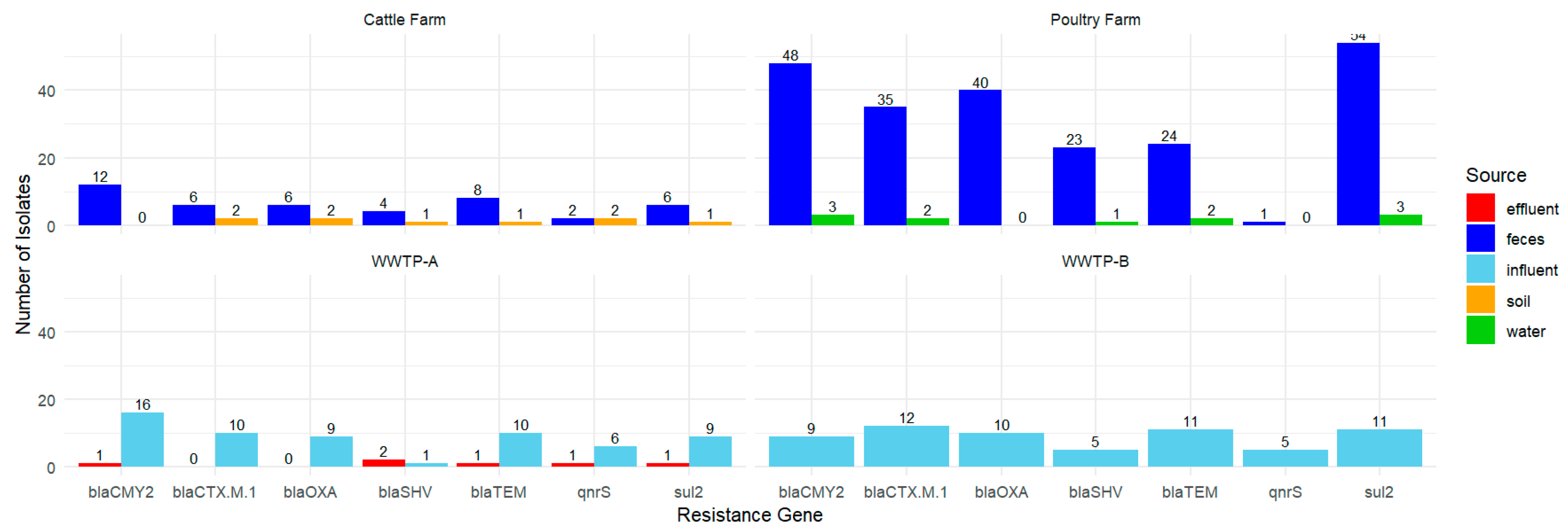

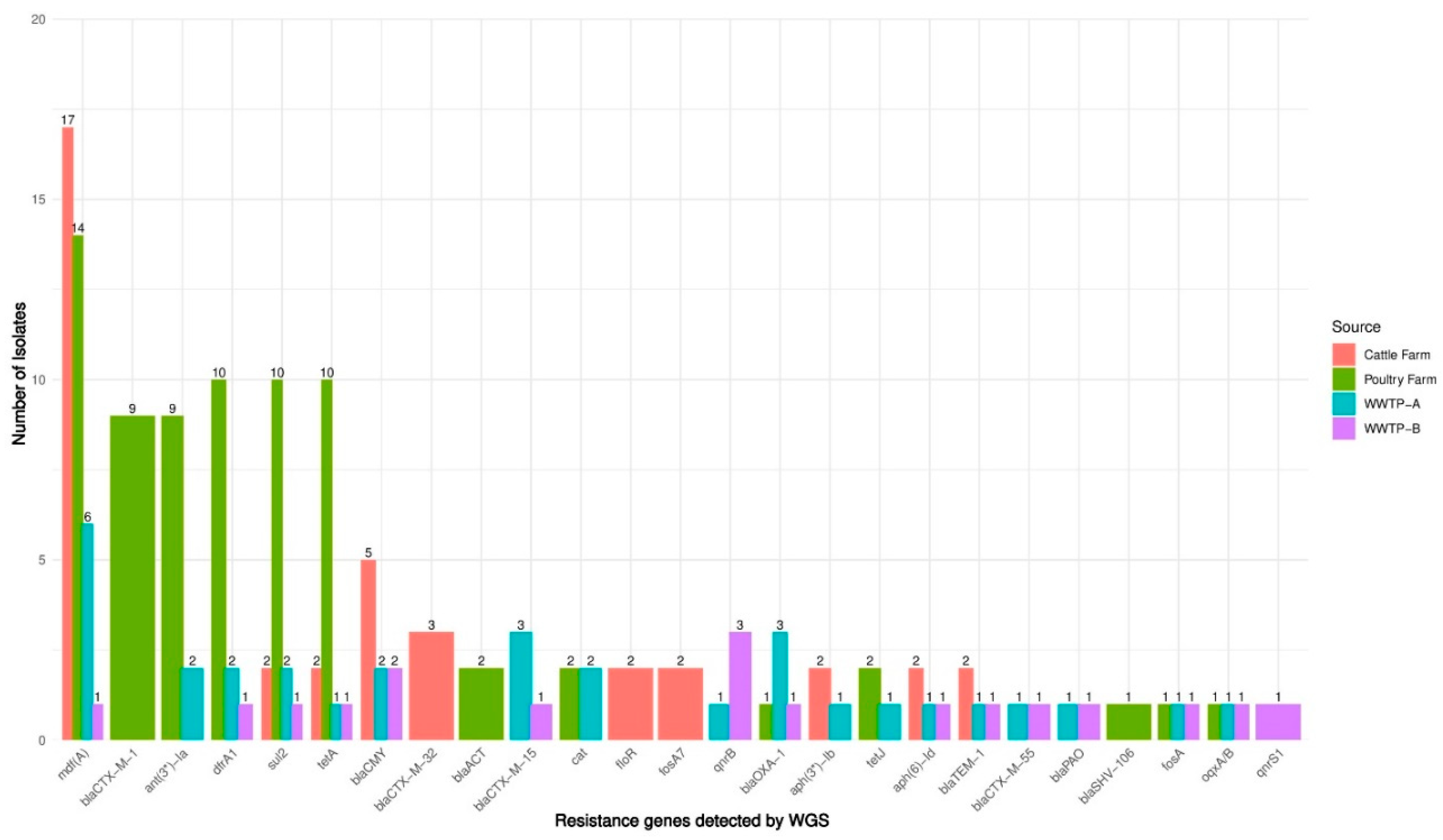

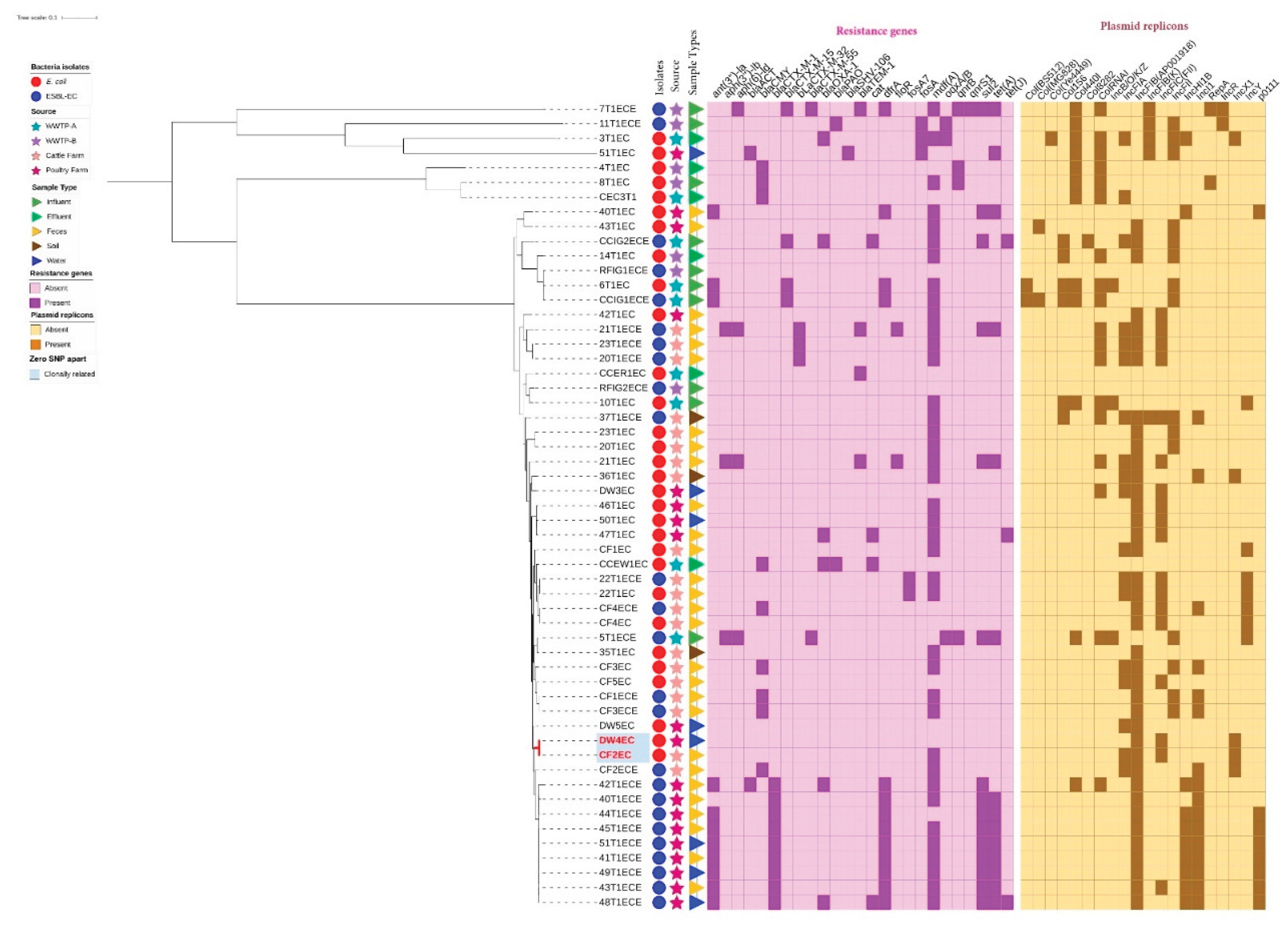

3.5. WGS-Based Detection of Resistance Genes

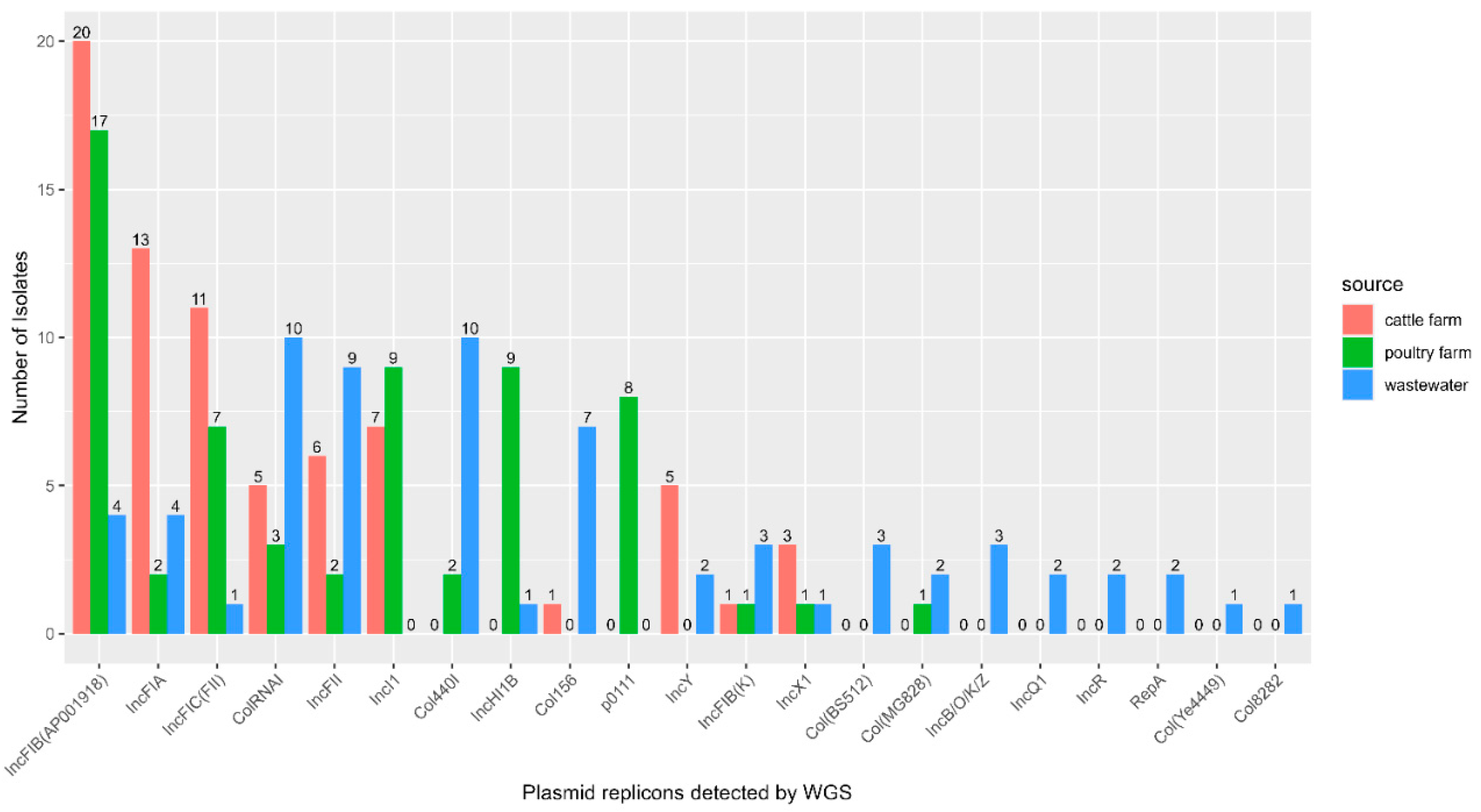

3.6. Plasmid Replicons Detected in E. coli Isolates

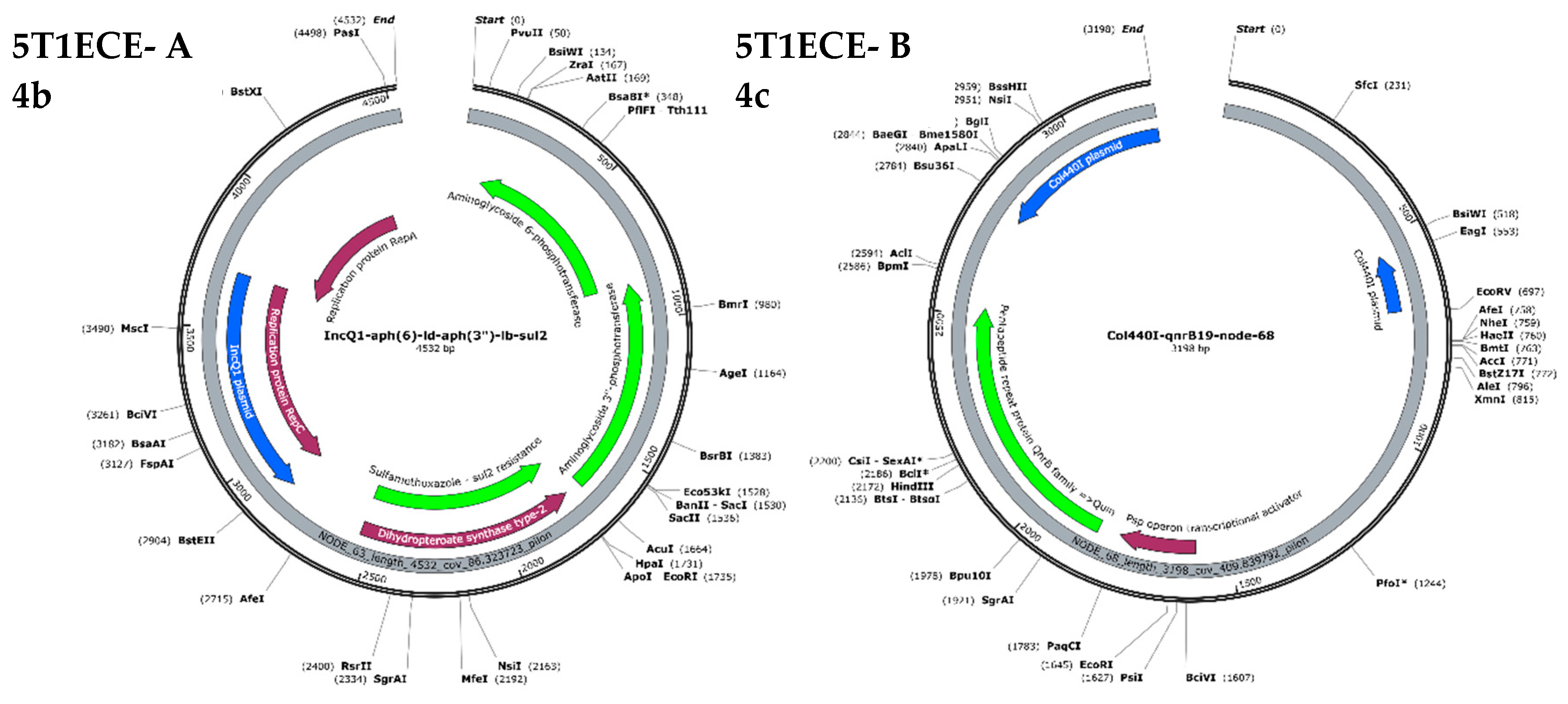

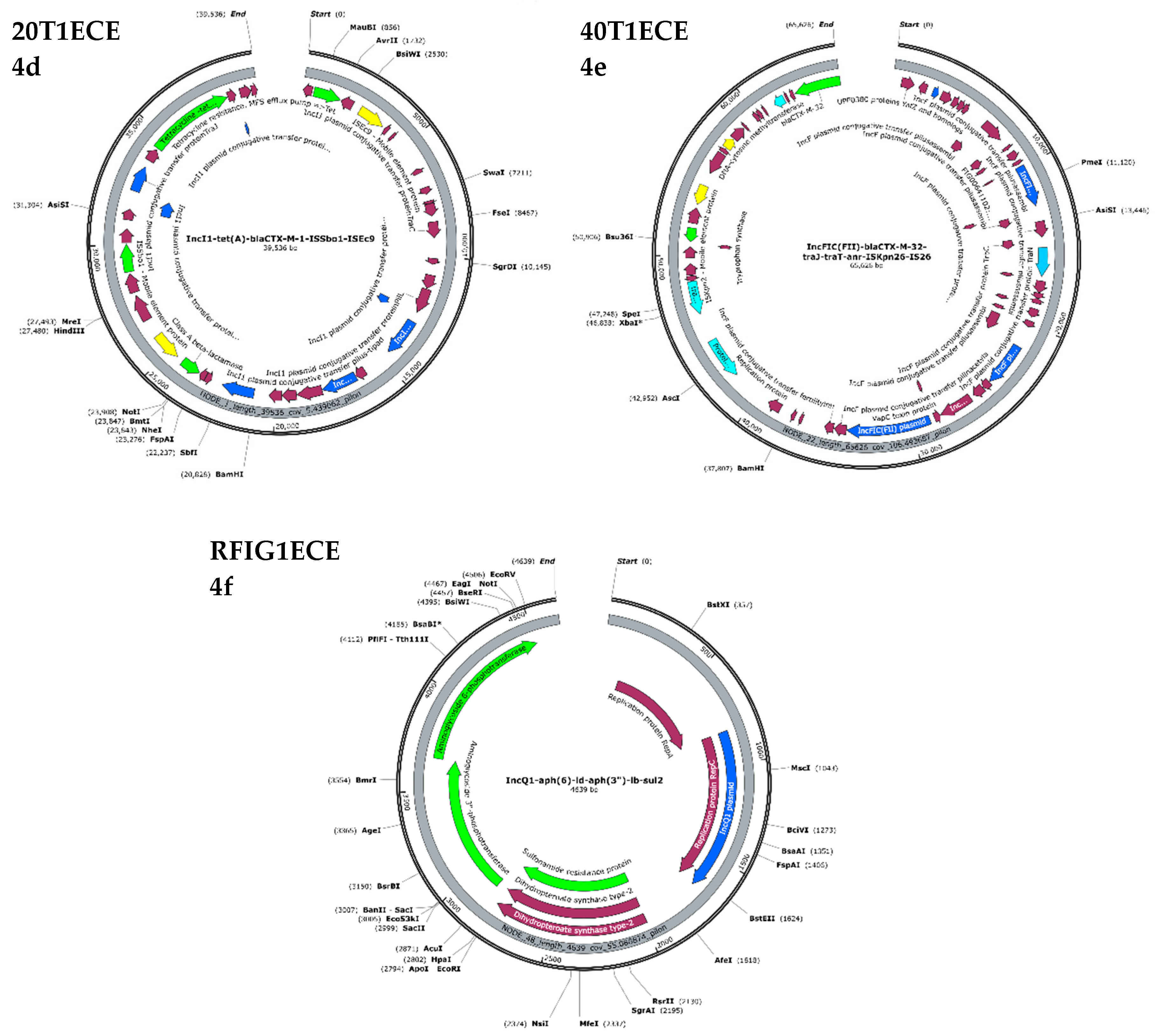

3.7. Plasmid-Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance

3.8. Multi-Locus Sequence Typing of E. coli Isolates

3.9. Phylogenetic Analysis of E. coli and ESBL-EC Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braz, S; Melchior, K; Moreira, CG; Farfan, MJ; Toro, CS. Escherichia coli as a Multifaceted Pathogenic and Versatile Bacterium. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S; Silva, V; de Lurdes Enes Dapkevicius, M; Caniça, M; Tejedor-Junco, MT; Igrejas, G; et al. Escherichia coli as commensal and pathogenic bacteria among food-producing animals: Health implications of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production. Animals 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, MK; Ekeng, E; Nilsson, P; Egyir, B; Owusu-Nyantakyi, C; Hendriksen, RS. Extended-Spectrum ß-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Among Humans, Beef Cattle, and Abattoir Environments in Nigeria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B; Allahyari, S; Amani, Z; Brück, WM; Mahmoudi, R. Prevalence, Phylogroups and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Isolates from Food Products. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefipour, M; Rezatofighi, SE; Ardakani, MR. Detection and characterization of hybrid uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains among E. coli isolates causing community-acquired urinary tract infection. J Med Microbiol. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, A; Saber, M; Gadow, S; Awad, F. Biological indicators for pollution detection in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2020, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruch, L; Paruch, AM. An Overview of Microbial Source Tracking Using Host-Specific Genetic Markers to Identify Origins of Fecal Contamination in Different Water Environments. Water 2022, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi, J; Ojewole, CO; Ojewole, AE. Antimicrobial Resistance Development Pathways in Surface Waters and Public Health Implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D; Ryu, K; Zhi, S; Otto, SJG; Neumann, NF. Naturalized Escherichia coli in Wastewater and the Co-evolution of Bacterial Resistance to Water Treatment and Antibiotics. Front Microbiol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, JP; Amato, HK; Mendizabal-Cabrera, R; Alvarez, D; Ramay, BM. Waterborne urinary tract infections: Have we overlooked an important source of exposure? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021, 105, 12–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, MF; Schmitt, H; Bo, S; Stehling, EG; Boerlin, P; Topp, E; et al. The potential of using E. coli as an indicator for the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the environment. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2021, 62, 152–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mkilima, T. Wastewater as a Sentinel for Emerging Antimicrobial Resistance Threats: A Review. Environ Qual Manag. 2025, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gregova, G; Kmet, V; Szaboova, T. New Insight on Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence of Escherichia coli from Municipal and Animal Wastewater. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, MK; Kwaga, J; Hendriksen, R; Okolocha, E; Thakur, S. Genetic relatedness of multidrug resistant Escherichia coli isolated from humans, chickens and poultry environments. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fatokun, O; Selvaraja, M; Anuar, H; Zetty, T; Tengku, M. Antimicrobial resistance at the human – animal – environment interface: A focus on antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli transmission dynamics, clinical implications, and future directions. Int J One Heal 2024, 10, 161–71. [Google Scholar]

- Addae-nuku, DS; Kotey, FCN; Dayie, NTKD; Osei, M; Tette, EMA; Debrah, P; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in Hospital Wastewater of the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, Ghana. Environ Health Insights 2022, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Husna, A; Rahman, MM; Badruzzaman, ATM; Sikder, MH; Islam, MR; Rahman, MT; et al. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL): Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mandujano-hern, A; Ver, A; Paz-gonz, AD; Herrera-mayorga, V; Mario, S; Lara-ram, EE; et al. The Global Rise of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in the Livestock Sector: A Five-Year Overview. Animals 2024, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, N; Karlsson, M; Reses, HE; Daniels, J; Stanton, RA; Janelle, SJ; et al. Epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales in five US sites participating in the Emerging Infections Program, 2017. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022, 43, 1586–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, C; Johnson, JD; Marie, JPS; Gacosta, KYM; Drumm, NBD; Jones, GD. coli and metagenomic analysis of source wastewater samples. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A; Kurittu, P; Al-Mustapha, AI; Heljanko, V; Johansson, V; Thakali, O; et al. Wastewater surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens: A systematic review. Front Microbiol 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, MK; Thakur, S; Gensler, C; Harrell, E; Harden, L; Fedorka-Cray, PJ; et al. Characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from retail meat products in North Carolina. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0294099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H; Gao, M; Wang, X; Qiu, T; Guo, Y; Zhang, L. Animal farms are hot spots for airborne antimicrobial resistance. Sci Total Environ 2022, 158050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, MC; Maugeri, A; Favara, G; La Mastra, C; Magnano San Lio, R; Barchitta, M; et al. The Impact of Wastewater on Antimicrobial Resistance: A Scoping Review of Transmission Pathways and Contributing Factors. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T; Nickerson, R; Zhang, W; Peng, X; Shang, Y; Zhou, Y; et al. The impacts of animal agriculture on One Health—Bacterial zoonosis, antimicrobial resistance, and beyond. One Heal 2024, 18, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khalaifah, H; Rahman, MH. A One-Health Perspective of Antimicrobial Resistance ( AMR ): Human, Animals and Environmental Health. Life 2025, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, M; Dubey, SK. Antimicrobial Resistance Transmission in Environmental Matrices: Current Prospects and Future Directions. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2025, 263, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, SP; Jarocki, VM; Seemann, T; Cummins, ML; Watt, AE; Drigo, B; et al. Genomic surveillance for antimicrobial resistance — a One Health perspective. Nat Rev Genet. 2024, 25, 142–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appling, KC; Sobsey, MD; Durso, LM; Fisher, MB. Environmental monitoring of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in North Carolina water and wastewater using the WHO Tricycle protocol in combination with membrane filtration and compartment bag test methods for detecting and quantifying ESBL E. coli. PLOS Water 2023, 2, e0000117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, N; Papafotis, D; Miller, S; Lee, B; Theologidis, I; Luna, B. Environmental Spread of Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D; Paco, J; Wojnarowski, K; Cholewi, P. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Food Animal Production: Environmental Implications and One Health Challenges. Environments 2025, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. M100, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2022.

- Ogutu, JO; Zhang, Q; Huang, Y; Yan, H; Su, L; Gao, B; et al. Development of a multiplex PCR system and its application in detection of blaSHV, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-9 and blaOXA-1 group genes in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli strains. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2015, 68, 725–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A; Nurk, S; Antipov, D; Gurevich, AA; Dvorkin, M; Kulikov, AS; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012, 19, 455–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, AM; Darriba, D; Flouri, T; Morel, B; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. M100, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2022.

- Letunic, I; Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, MK; Kwaga, J; Okolocha, E; Harden, L; Hull, D; Hendriksen, RS; et al. Extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among humans, chickens and poultry environments in Abuja, Nigeria. One Heal Outlook 2020, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martak, D; Henriot, CP; Hocquet, D. Environment, animals, and food as reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for humans: One health or more? Infect Dis Now 2024, 54, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkov, M; Proux, C; Rasolofoarison, TL; Rakotomalala, FA; Rasoanandrasana, S; Rahajamanana, VL; et al. Implementation of the WHO Tricycle protocol for surveillance of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in humans, chickens, and the environment in Madagascar: a prospective genomic epidemiology study. The Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, MA; Saqlain, M; Waheed, U; Ehtisham-ul-Haque, S; Khan, AU; Rehman A ur; et al. Cross-Sectional Study for Detection and Risk Factor Analysis of ESBL-Producing Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Associated with Backyard Chickens in Pakistan. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, AB; Jalila, A; Saleha, AA; Zunita, Z. ESBL Producing E. coli in Chickens and Poultry Farms Environment in Selangor, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study on Their Occurrence and Associated Risk Factors With Environment and Public Health Importance. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 962–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, A; Khairullah, AR; Effendi, MH; Moses, IB; Agustin, ALD. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from poultry: A review. Vet World 2024, 17, 2017–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonggrijp, MA; Velthuis, AGJ; Heuvelink, AE; van den Heuvel, KWH; ter Bogt-Kappert, CC; Buter, GJ; et al. Prevalence of extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in young calves on Dutch dairy farms. J Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 4257–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelalcha, BD; Gelgie, AE; Kerro Dego, O. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in East Tennessee dairy farms. Front Vet Sci 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-salazar, A; Martínez-Vázquez, A; Aguilera-arreola, G; De Luna-santillana, EDJ; Escobedo-bonilla, CM; Lara-ram, E; et al. Prevalence of ESKAPE Bacteria in Surface Water and Wastewater Sources: Multidrug Resistance and Molecular Characterization, an Updated Review. Water 2023, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutescu, LG; Popa, M; Gheorghe-Barbu, I; Barbu, IC; Rodríguez-Molina, D; Berglund, F; et al. Wastewater treatment plants, an “escape gate” for ESCAPE pathogens. Front Microbiol 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawangpa, A; Lertwatcharasarakul, P; Ramasoota, P; Boonsoongnern, A; Ratanavanichrojn, N; Sanguankiat, A; et al. Genotypic and phenotypic situation of antimicrobial drug resistance of Escherichia coli in water and manure between biogas and non-biogas swine farms in central Thailand. J Environ Manage 2021;279 July 2020, 111659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, JPR; Stehling, EG. Multiple sequence types, virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance genes in multidrug- and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli from agricultural and non-agricultural soils. Environ Pollut 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, TM; Martin, NA; Reynolds, LJ; Sala-Comorera, L; O’Hare, GMP; O’Sullivan, JJ; et al. Agricultural and urban practices are correlated to changes in the resistome of riverine systems. Sci Total Environ 2024, 172261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Hurtado, MS; Fernández-Fernández, R; Rubio-Tomás, L; Marañón-Clemente, I; Álvarez-Gómez, T; García-Mora, DJ; et al. Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant and ESBL-Producing Enterobacterales in Wastewater and Sludge Environments from Northern Spain. Appl Sci. 2025, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickin, SK; Schuster-Wallace, CJ; Qadir, M; Pizzacalla, K. A review of health risks and pathways for exposure to wastewater Use in Agriculture. Environ Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 900–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F; Wang, X; Mahmood, MQ; Juliette, OK. Assessing human health risks associated with wastewater flooding. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2025, 108031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, MK; Kwaga, JKP; Hendriksen, RS; Okolocha, EC; Harrell, E; Thakur, S. Quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli at the interface between humans, poultry and their shared environment- a potential public health risk. One Heal Outlook 2023, 5. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO | WHO list of Critically Important Antimicrobials (CIA). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kanokudom, S; Assawakongkarat, T; Akeda, Y; Ratthawongjirakul, P; Chuanchuen, R; Chaichanawongsaroj, Id N. Rapid detection of extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli isolated from fresh pork meat and pig cecum samples using multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification and lateral flow strip analysis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahim, A; Harrell, E; Fedorka-Cray, PJ; Jacob, M; Thakur, S. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterizations of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates from Diverse Retail Meat Samples in North Carolina During 2018-2019. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2024, 21, 211–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surleac, M; Barbu, IC; Paraschiv, S; Popa, LI; Gheorghe, I; Marutescu, L; et al. Whole genome sequencing snapshot of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from hospitals and receiving wastewater treatment plants in Southern Romania. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, K; Tayh, G; Maamar, E; Mosbah, A; Abbes, O; Fliss, I; et al. Genotypic Characterisation and Risk Assessment of Virulent ESBL-Producing E. coli in Chicken Meat in Tunisia: Insights from Multi-Omics Machine Learning Perspective. Microbiol Res (Pavia) 2025, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, AKMZ; Chowdhury, AMMA. Understanding the Evolution and Transmission Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistance Genes: A Comprehensive Review. J Basic Microbiol 2024, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S; Yang, J; Abbas, M; Yang, Q; Li, Q; Liu, M; et al. Threats across boundaries: the spread of ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae bacteria and its challenge to the “one health” concept. Front Microbiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, SA; Asencio-Egea, MÁ; Huertas-Vaquero, M; Cardona-Cabrera, T; Zarazaga, M; Höfle, U; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of ESBL- and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales in a Spanish Hospital: Exploring the Clinical–Environmental Interface. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, A; Yahara, K; Mitsuhashi, S; Nakagawa, S; Imanishi, T; Ha, VTT; et al. Plasmid analysis of NDM metallo-β-lactamaseproducing Enterobacterales isolated in Vietnam. PLoS One 2021, 16 7 July, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gelalcha, BD; Mohammed, RI; Gelgie, AE; Kerro Dego, O. Molecular epidemiology and pathogenomics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing- Escherichia coli and - Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from bulk tank milk in Tennessee, USA. Front Microbiol 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraschek, K; Malekzadah, J; Malorny, B; Käsbohrer, A; Schwarz, S; Meemken, D; et al. Characterization of qnrB-carrying plasmids from ESBL- and non-ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufu, IA; Ahmed, OA; Aremu, A; Ameh, JA; Timme, RE; Hendriksen, RS; et al. Antimicrobial and Genomic Characterization of Salmonella Nigeria from Pigs and Poultry in Ilorin, North-central, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries 2021, 15, 1899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levent, G; Schlochtermeier, A; Ives, SE; Norman, KN; Lawhon, SD; Loneragan, GH; et al. High-Resolution Genomic Comparisons within Salmonella enterica Serotypes Derived from Beef Feedlot Cattle: Parsing the Roles of Cattle Source, Pen, Animal, Sample Type, and Production Period. Appl Environ Microbiol 2021, 87, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalazen, G; Fuentes-Castillo, D; Pedroso, LG; Fontana, H; Sano, E; Cardoso, B; et al. CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli ST602 carrying a wide resistome in South American wild birds: Another pandemic clone of One Health concern. One Heal 2023, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, CA; Tarlton, NJ; Riley, LW. Escherichia coli from Commercial Broiler and Backyard Chickens Share Sequence Types, Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles, and Resistance Genes with Human Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019, 16, 813–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojer-Usoz, E; González, D; Vitas, AI. Clonal diversity of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from environmental, human and food samples. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 10–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Roza, FT; Couto, N; Carneiro, C; Cunha, E; Rosa, T; Magalhães, M; et al. Commonality of Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST348 Isolates in Horses and Humans in Portugal. Front Microbiol 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Drug Class |

Antimicrobial drugs |

Resistance breakpoint (mm) |

Total (n = 124; %) |

Cattle Farm (n = 17; %) |

Poultry Farm (n = 68; %) |

WWTP-A (n = 22; %) |

WWTP-B (n = 17; %) |

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline (30 µg) | ≤11 | 84 (67.7) | 3 (17.6) | 61 (89.7) | 11 (50.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| Folate pathway antagonists |

Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (5 µg /300 µg) | ≤15 | 43 (34.7) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (35.3) | 10 (45.5) | 9 (52.9) |

| Penicillins | Ampicillin (10 µg) | ≤13 | 119 (96.0) | 16 (94.1) | 65 (95.6) | 21 (95.5) | 17 (100.0) |

| Penicillin (10 µg) | ≤ 14 | 121 (97.6) | 17 (100.0) | 65 (95.6) | 22 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) | ≤21 | 31 (25.0) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (4.4) | 14 (63.6) | 10 (58.8) |

| Aminoglycosides | Streptomycin (10 µg) | ≤11 | 42 (33.9) | 1 (5.9) | 24 (35.3) | 10 (45.5) | 7 (41.2) |

| Phenicols | Chloramphenicol (30 µg) | ≤12 | 19 (15.3) | 2 (11.8) | 5 (7.4) | 8 (36.4) | 4 (23.5) |

| Cephalosporins | Cefotaxime (30 µg) | ≤22 | 119 (96.0) | 16 (94.1) | 65 (95.6) | 21 (95.5) | 17 (100.0) |

| Ceftazidime (30 µg) | ≤17 | 73 (58.9) | 13 (76.5) | 35 (51.4) | 16 (72.7) | 9 (52.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).