Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methodology

Materials

Methodology

Animals and Ethics Statement

Experimental Design and Animal Dossing

Biochemical Studies

Histological Analysis

Immunohistochemical Studies

Lipid Accumulation Studies

Gut Microbiome Studies

Gene Expression Analysis

miRNA Expression Analysis

Protein Expression Analysis

Results

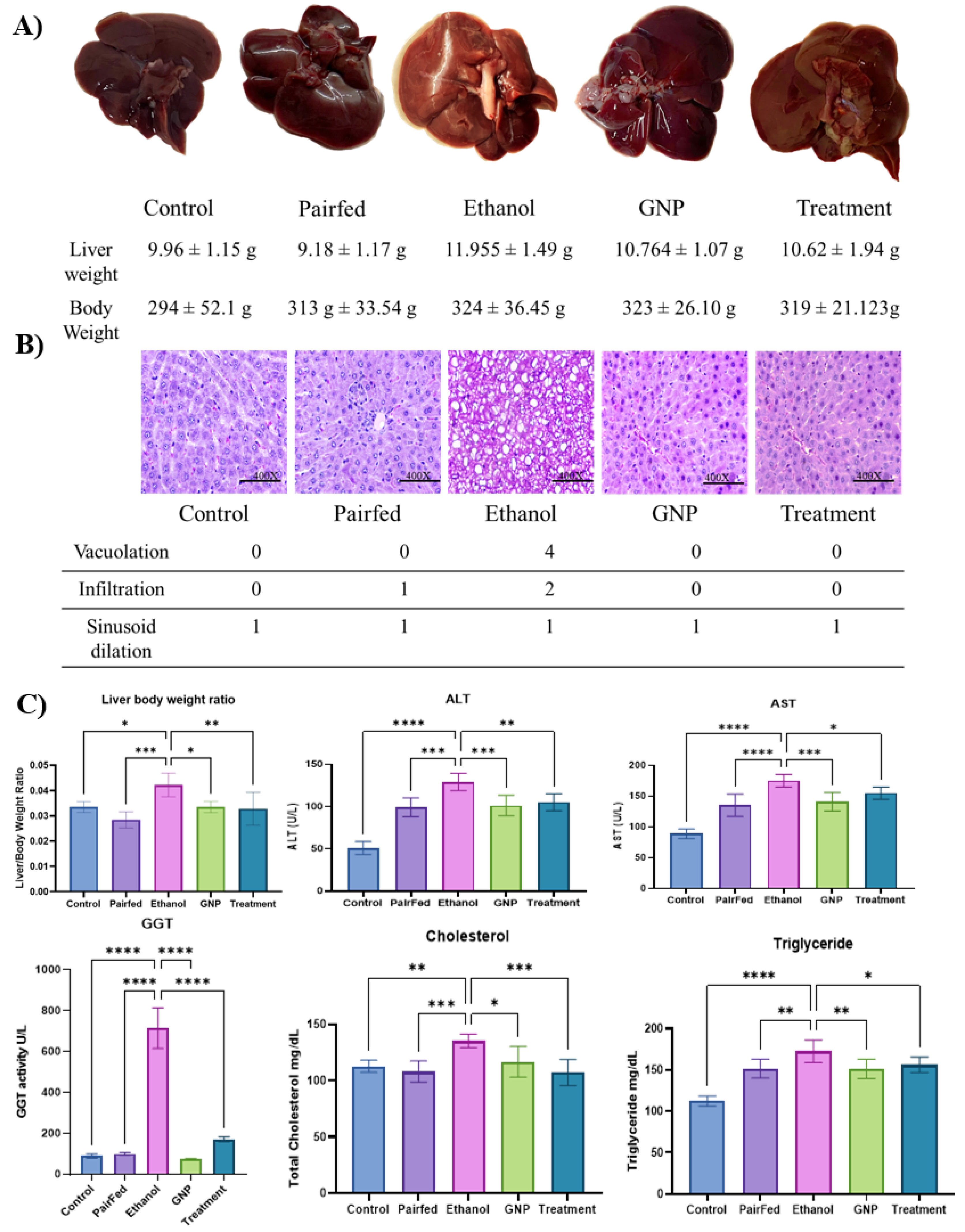

Liver Histology and Biochemical Parameters

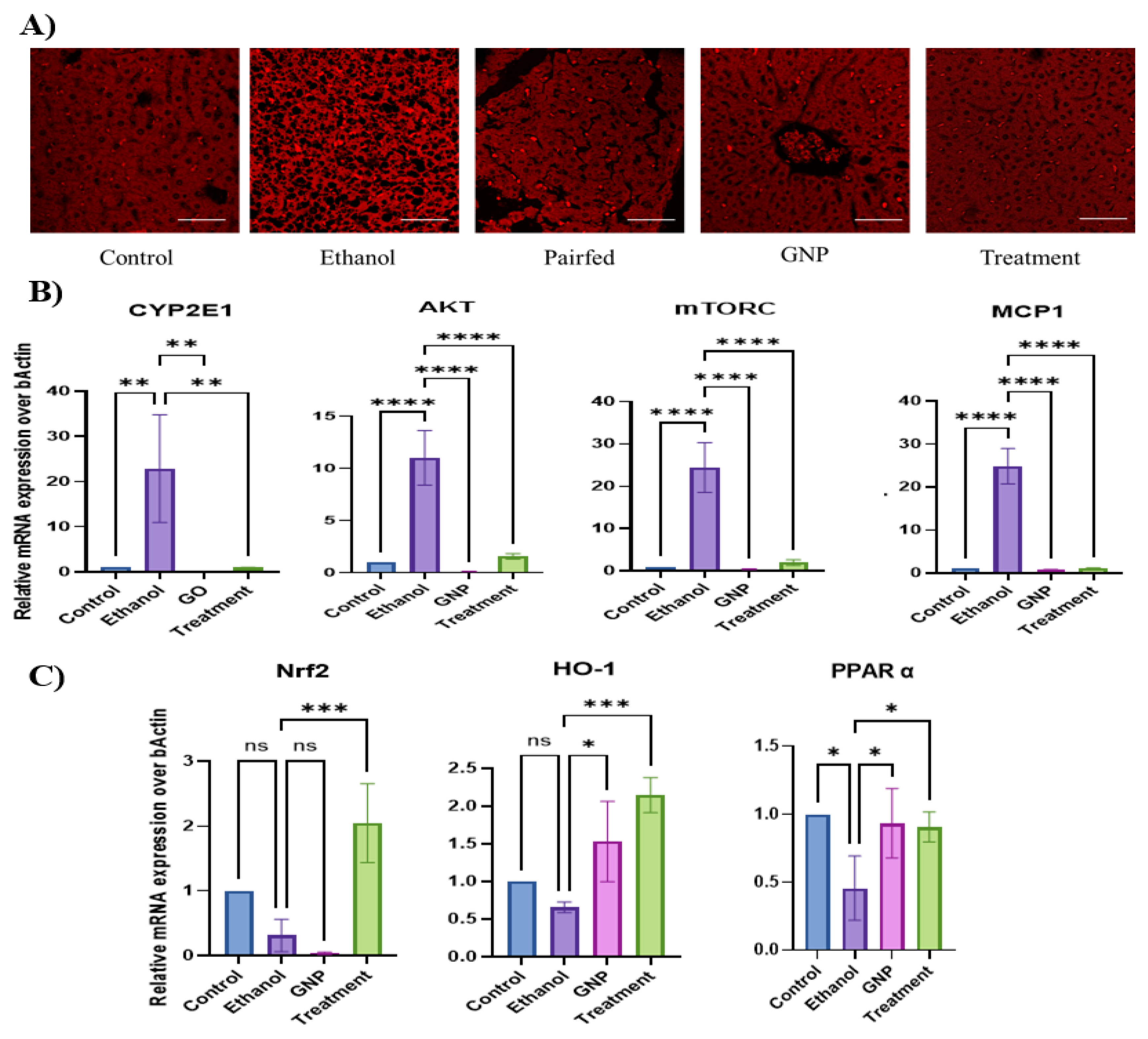

GNPs Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Dysregulation of Lipid-Associated Genes

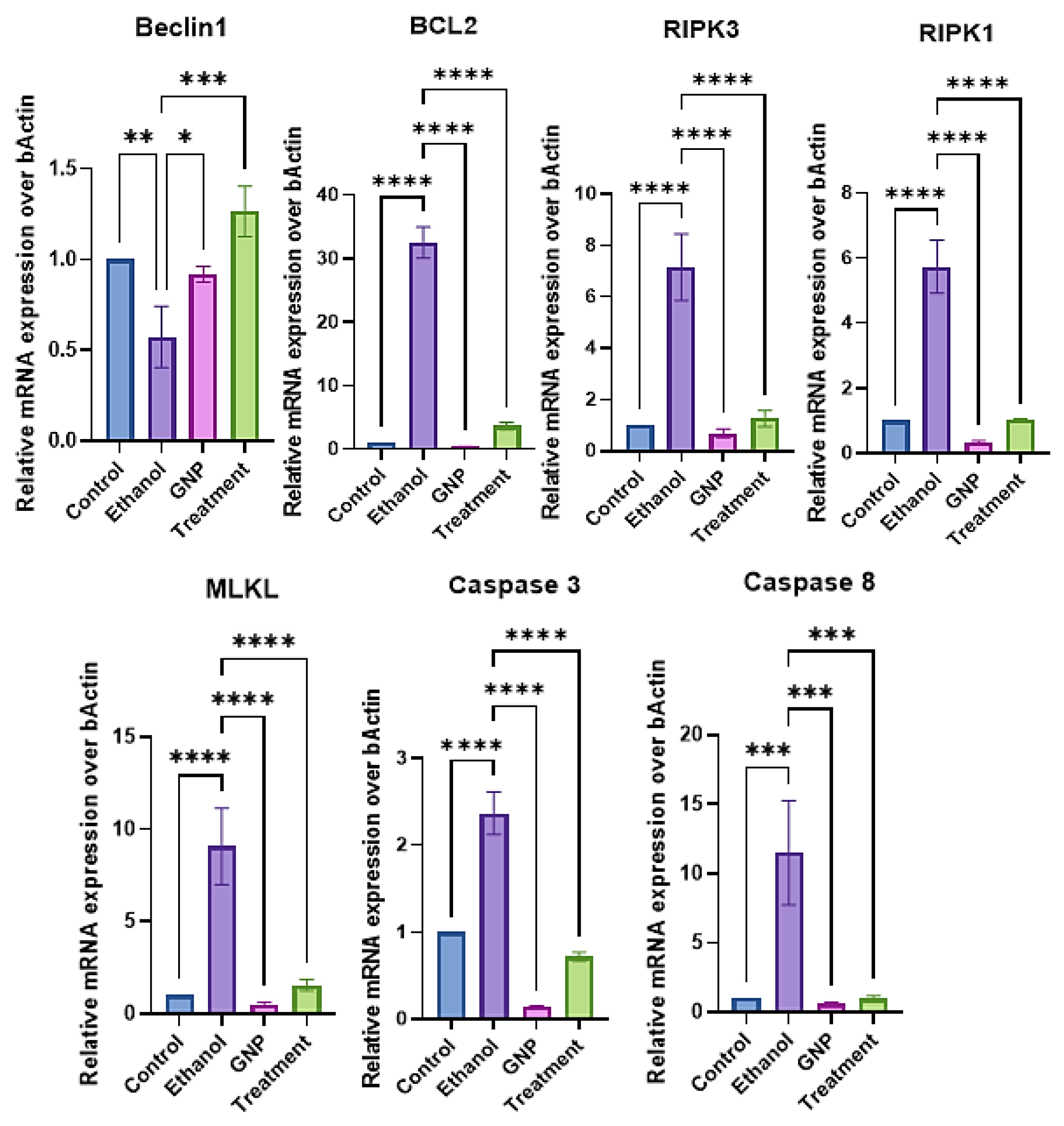

GNPs Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Apoptotic and Necroptotic Signalling

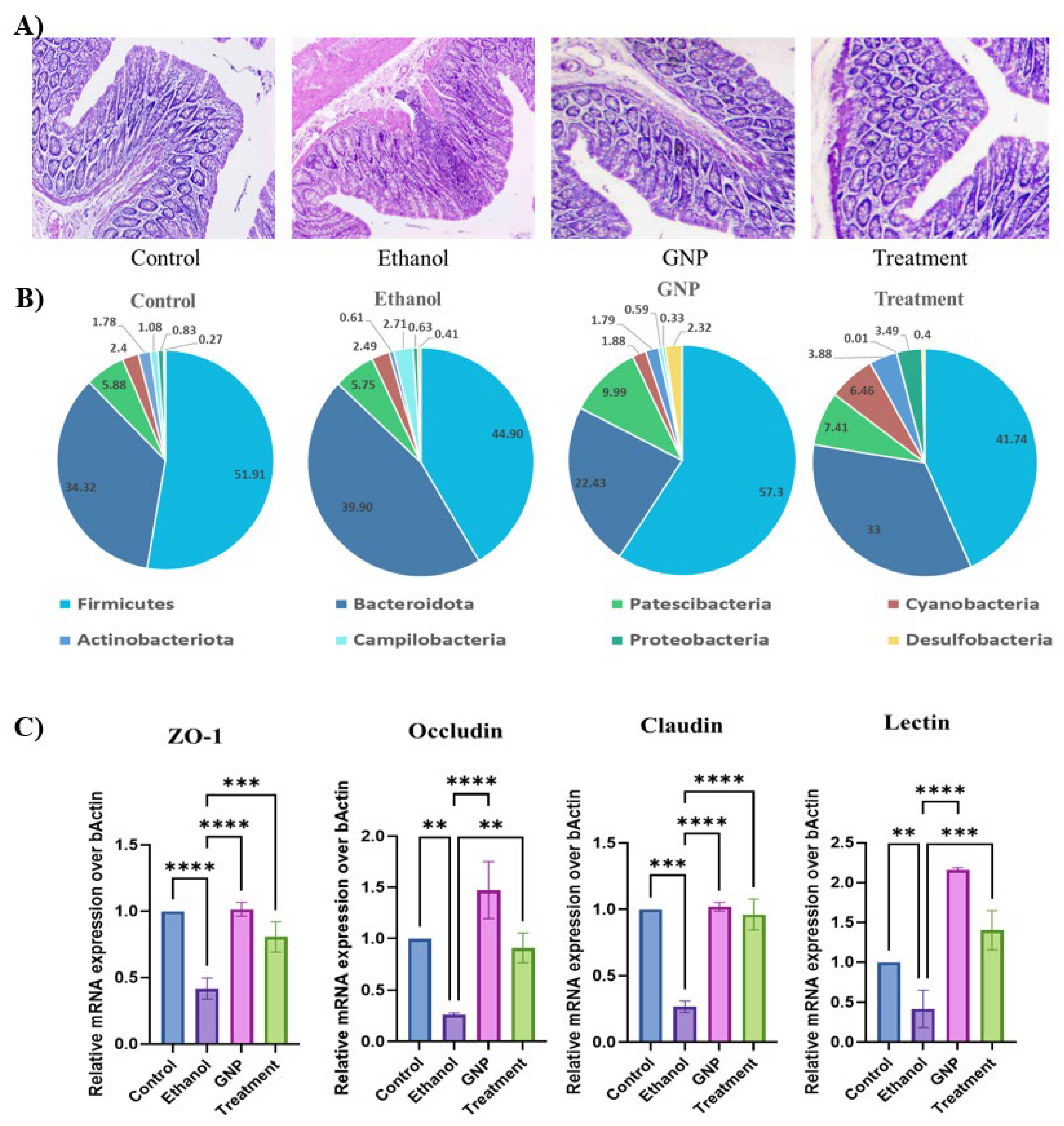

GNPs Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Intestinal Injury and Modulate Gut–Liver Axis–Associated TLR4 Signalling and miRNA Expression

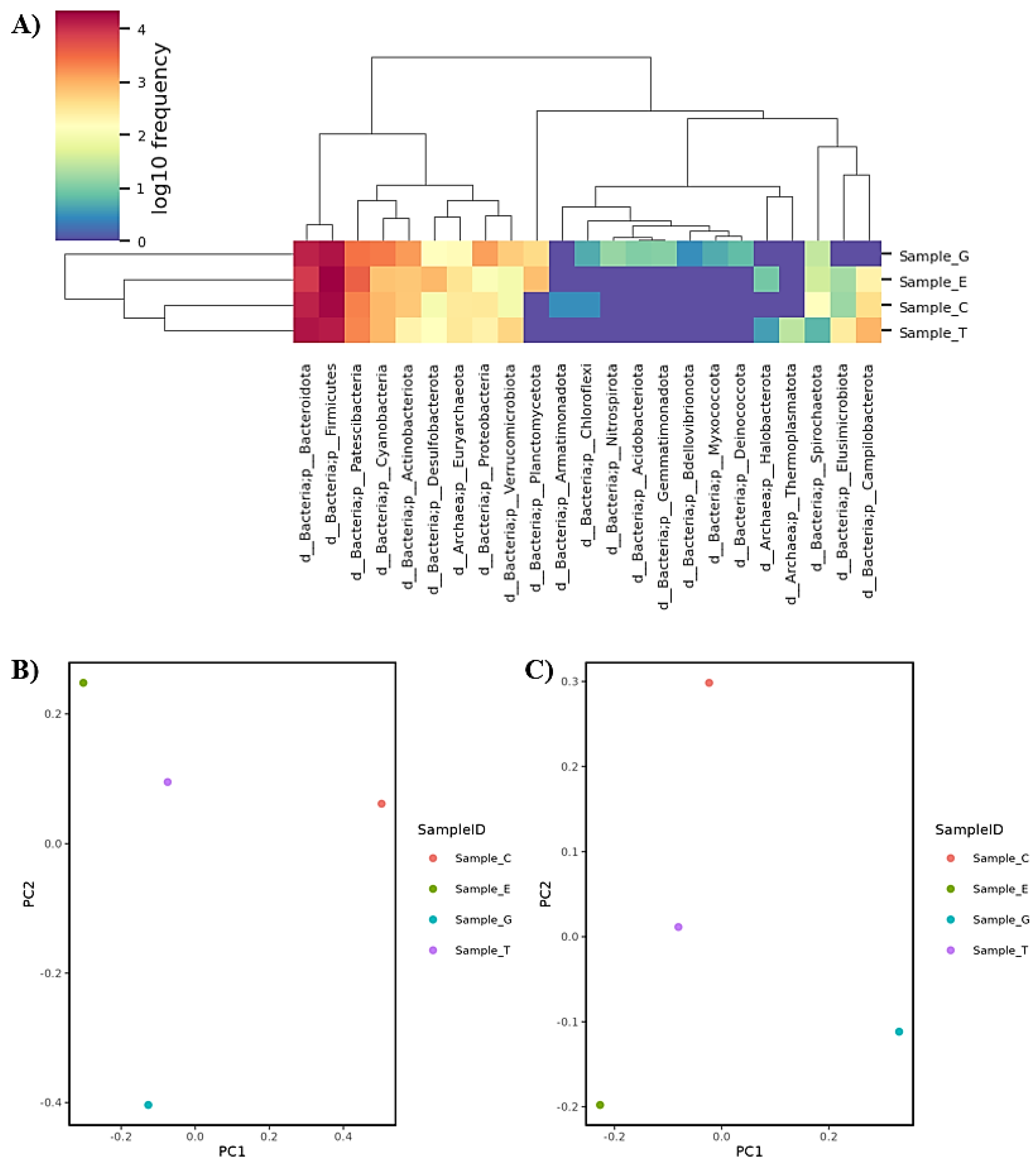

GNPs Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Intestinal Injury and Gut Dysbiosis

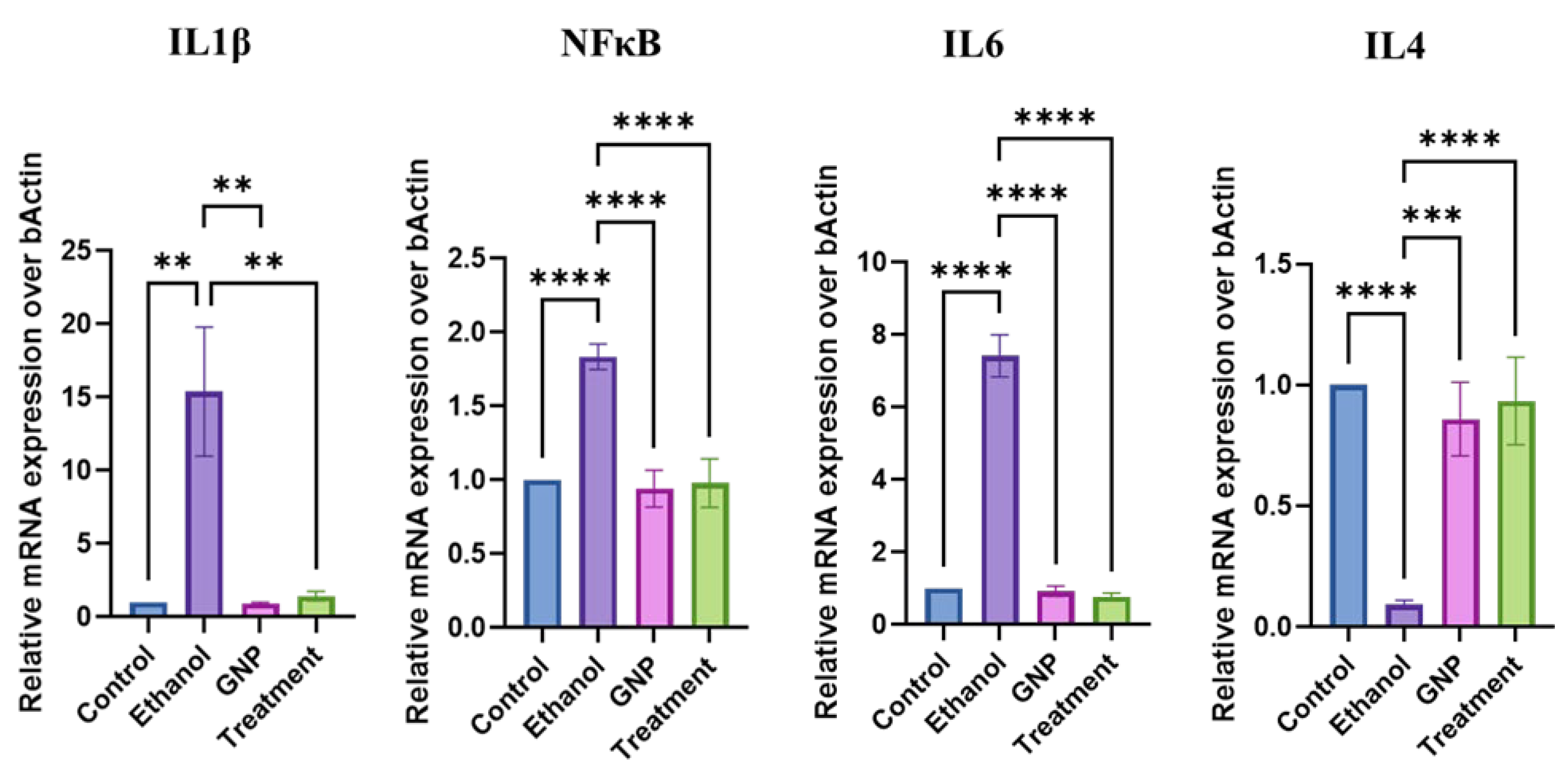

GNPs Suppress Ethanol-Induced Intestinal Inflammatory Responses

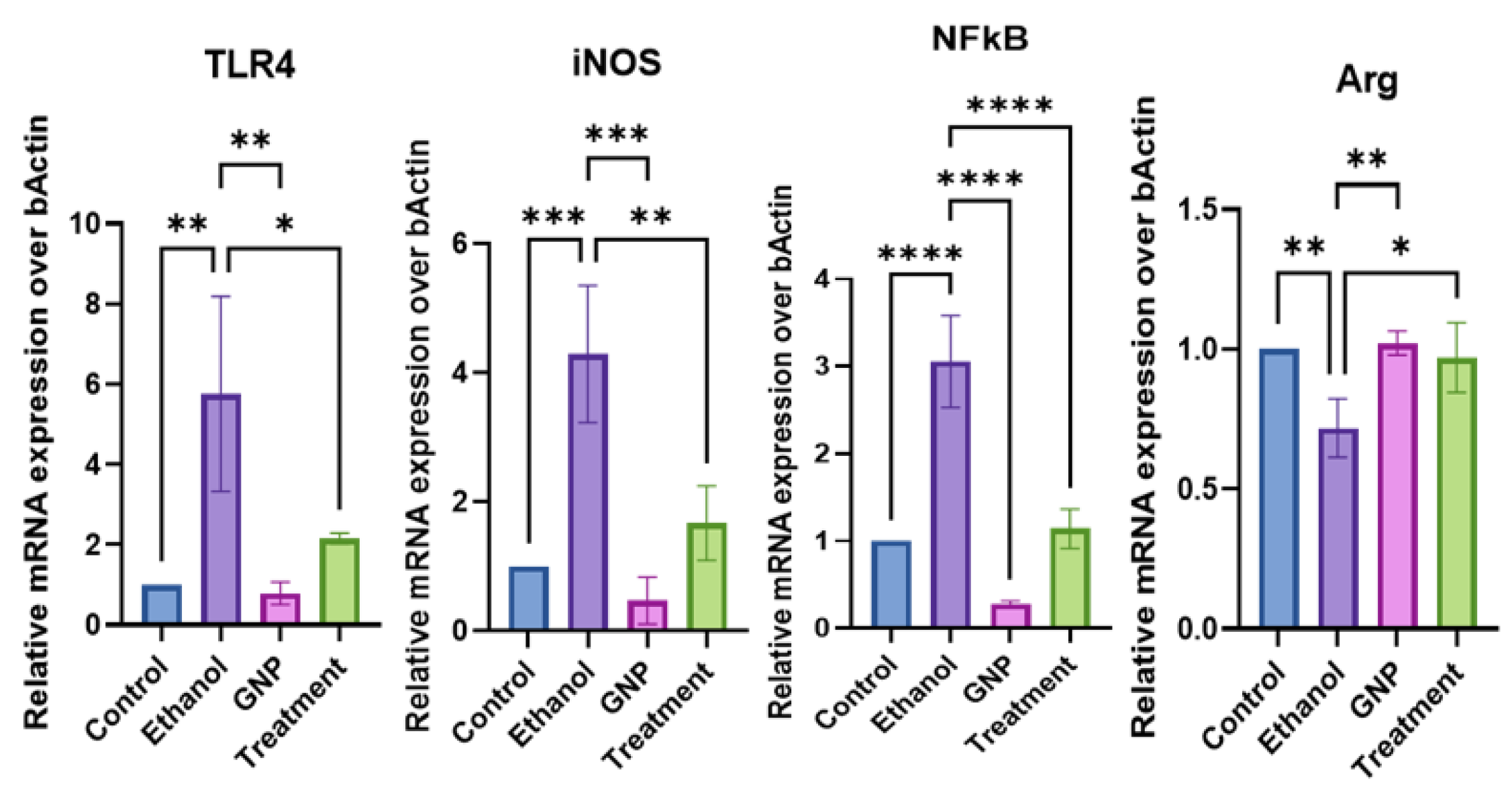

GNPs Modulate Hepatic TLR4-Associated Inflammatory Signalling

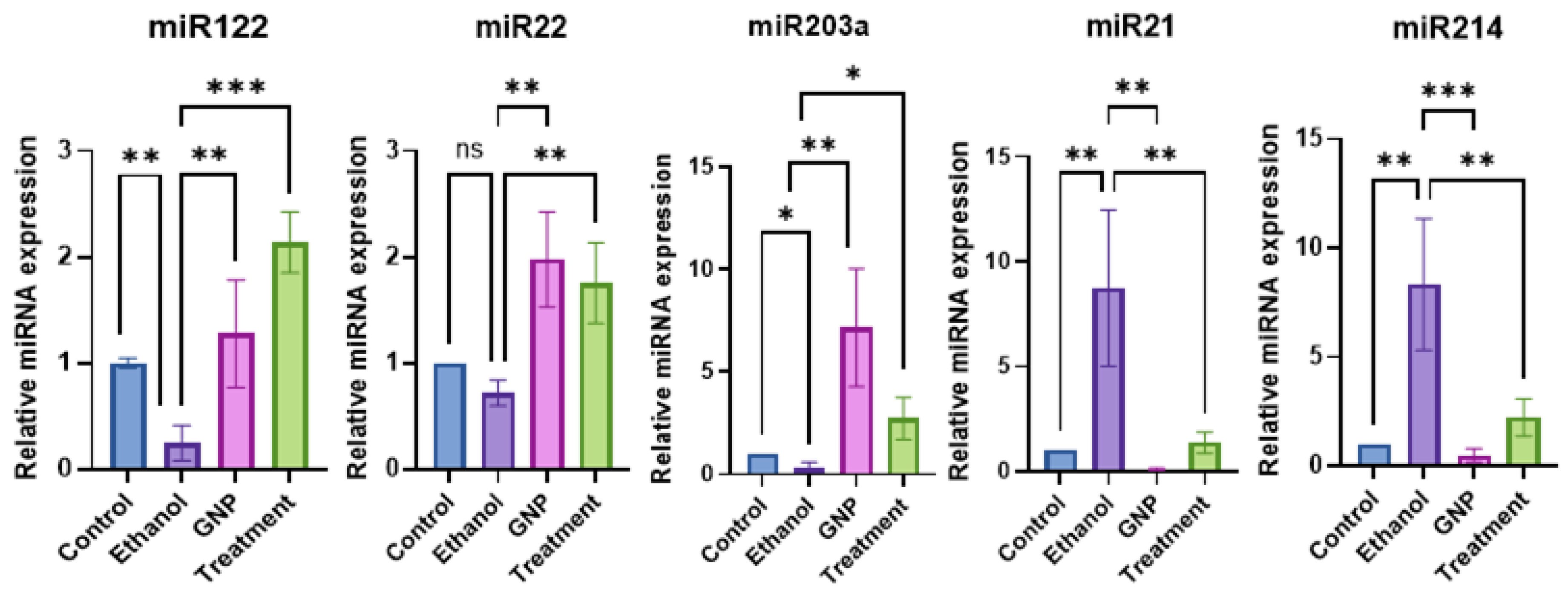

GNPs Regulate miRNA Expression Linked to Gut–Liver Axis Signalling

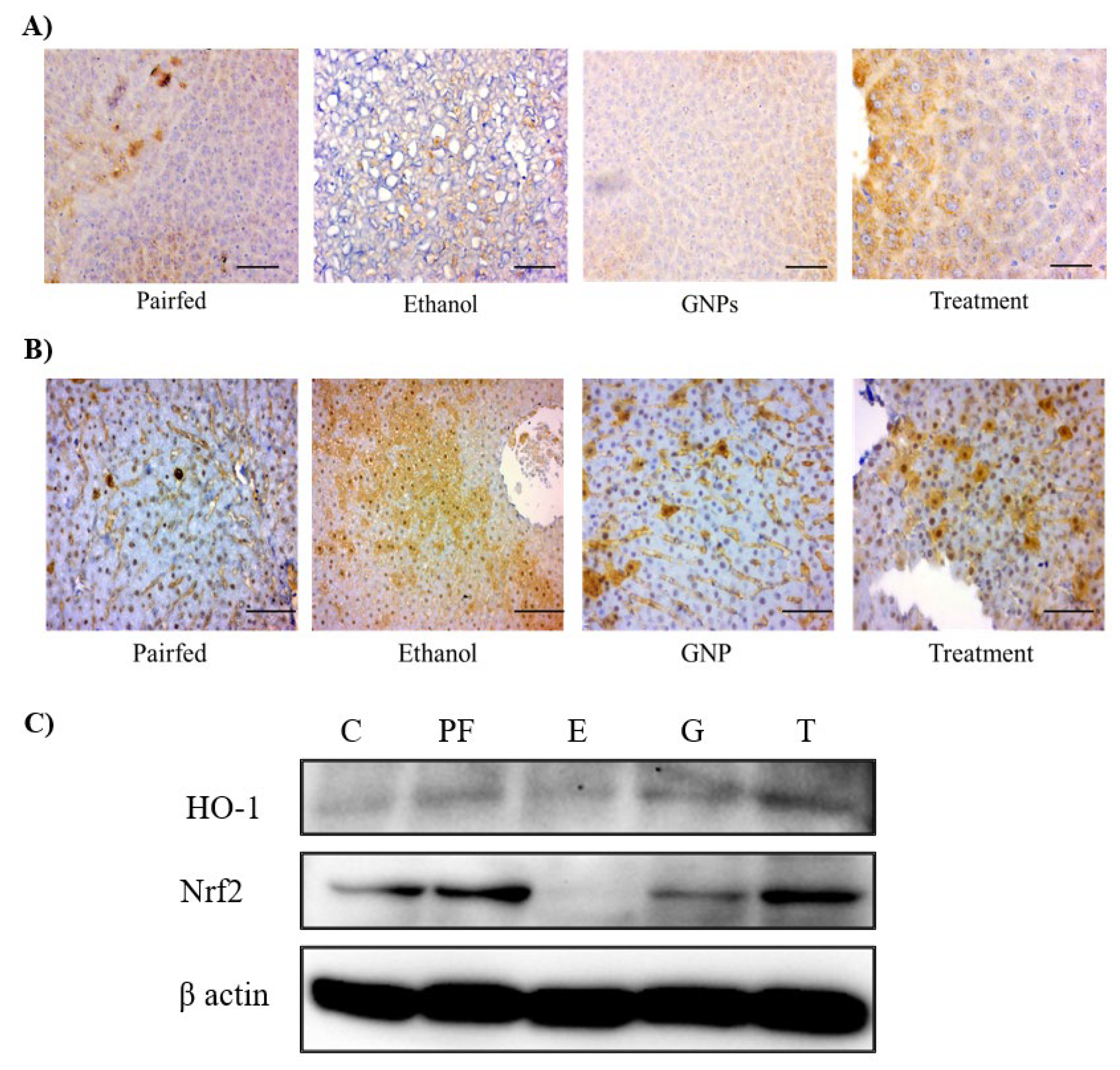

GNPs Modulate Ethanol-Induced Stress–Related Protein Expression

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALD | Alcohol-associated liver disease |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| Arg | Arginase |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome P450 2E1 |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GNPs | Graphene oxide nanoparticles |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| mTORC | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex |

| MCP1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| RIPK1 | Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 |

| RIPK3 | Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 |

| MLKL | Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

References

- Danpanichkul, P; Suparan, K; Ng, CH; Dejvajara, D; Kongarin, S; Panpradist, N; et al. Global and regional burden of alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder in the elderly. JHEP Reports 2024, 6(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghara, H; Chadha, P; Zala, D; Mandal, P. Stress mechanism involved in the progression of alcoholic liver disease and the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, CH; El-Omar, E; Kao, CY; Lin, JT; Wu, CY. Compositional and Metabolomic Shifts of the Gut Microbiome in Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2025, 40(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A; de Gottardi, A; Rescigno, M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol. 2020, 72(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, JS. Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16(4), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghara, H; Patel, M; Chadha, P; Parwani, K; Chaturvedi, R; Mandal, P. Unraveling the Gut–Liver–Brain Axis: Microbiome, Inflammation, and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches. Mediators Inflamm. 2025, 2025(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, MM; Rosman, AS; Mazlan, NS; Ahmad, MF; Halin, DSC; Mohamed, R; et al. Cell viability and electrical response of breast cancer cell treated in aqueous graphene oxide solution deposition on interdigitated electrode. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghara, H; Chadha, P; Mandal, P. Mitigative Effect of Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles in Maintaining Gut–Liver Homeostasis against Alcohol Injury. Gastroenterol Insights 2024, 15(3), 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H; Meng, W; Zhao, D; Ma, Z; Zhang, W; Chen, Z; et al. Study on mechanism of action of total flavonoids from Cortex Juglandis Mandshuricae against alcoholic liver disease based on gut-liver axis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M; Yin, D; Chen, J; Qu, X. Activating the interleukin-6-Gp130-STAT3 pathway ameliorates ventricular electrical stability in myocardial infarction rats by modulating neurotransmitters in the paraventricular nucleus. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020, 20(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, P; Aghara, H; Solanki, H; Patel, M; Sharma, D; Thiruvenkatam, V; et al. Modulation of TNFα-driven neuroinflammation by Gardenin A: insights from in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies. Front Pharmacol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sata, TN; Ismail, M; Sah, AK; Venugopal, SK. Production of Functional miRNA Mimics Using In Vitro Transcription. Curr Protoc. 2025, 5(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, S; Mohanty, S; Mukherjee, S; Basu, S; Mishra, M. Graphene and graphene oxide as nanomaterials for medicine and biology application. J Nanostructure Chem. 2018, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigpelat, E; Ignés-Mullol, J; Sagués, F; Reigada, R. Interaction of Graphene Nanoparticles and Lipid Membranes Displaying Different Liquid Orderings: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Langmuir 2019, 35(50). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B; Hu, J; Wu, F. Cholesterols Induced Distinctive Entry of the Graphene Nanosheet into the Cell Membrane. ACS Omega 2024, 9(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Frutos, S; Griera, M; Lavín-López, M; del, P; Martínez-Rovira, M; Martínez-Rovira, JA; Rodríguez-Puyol, M; et al. A new graphene-based nanomaterial increases lipolysis and reduces body weight gain through integrin linked kinase (ILK). Biomater Sci. 2023, 11(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbigeri, MB; Thokchom, B; Singh, SR; Bhavi, SM; Harini, BP; Yarajarla, RB. Antioxidant and anti-diabetic potential of the green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Martynia annua L. root extract. Nano TransMed 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukhrib, M; Tamegart, L; Assafi, A; Hejji, L; Azzouz, A; Villarejo, LP; et al. Effects of graphene oxide nanoparticles administration against reserpine-induced neurobehavioral damage and oxidative stress in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2023, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaoli, F; Yaqing, Z; Ruhui, L; Xuan, L; Aijie, C; Yanli, Z; et al. Graphene oxide disrupted mitochondrial homeostasis through inducing intracellular redox deviation and autophagy-lysosomal network dysfunction in SH-SY5Y cells. J Hazard Mater 2021, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S; Xu, A; Gao, Y; Xie, Y; Liu, Z; Sun, M; et al. Graphene oxide exacerbates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis via ROS/AMPK/p53 signaling to mediate apoptosis. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, D; Sánchez-Moreno, P; Del Rio Castillo, AE; Bonaccorso, F; Gatto, F; Bardi, G; et al. Biotransformation and Biological Interaction of Graphene and Graphene Oxide during Simulated Oral Ingestion. Small 2018, 14(24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, V; Deleye, L; Podestà, A; Jaho, E; Loiacono, F; Debellis, D; et al. Interactions of Graphene Oxide and Few-Layer Graphene with the Blood-Brain Barrier. Nano Lett. 2023, 23(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G; Sinkko, HM; Alenius, H; Lozano, N; Kostarelos, K; Bräutigam, L; et al. Graphene oxide elicits microbiome-dependent type 2 immune responses via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Nanotechnol 2023, 18(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J; Yang, S; Yu, J; Cui, R; Liu, R; Lei, R; et al. Lipid- and gut microbiota-modulating effects of graphene oxide nanoparticles in high-fat diet-induced hyperlipidemic mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8(55). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, O; Costabile, A; Kujawska, M. The gut microbiome meets nanomaterials: exposure and interplay with graphene nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J; Dong, J; Zhao, J; Ye, T; Gong, L; Wang, H; et al. The effects of the oral administration of graphene oxide on the gut microbiota and ultrastructure of the colon of mice. Ann Transl Med. 2022, 10(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couvillion, SP; Danczak, RE; Cao, X; Yang, Q; Keerthisinghe, TP; McClure, RS; et al. Graphene oxide exposure alters gut microbial community composition and metabolism in an in vitro human model. NanoImpact 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C; Yan, J; Du, K; Liu, S; Wang, J; Wang, Q; et al. Intestinal microbiome dysbiosis in alcohol-dependent patients and its effect on rat behaviors. mBio 2023, 14(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, GY; Chen, CL; Tuan, HY; Yuan, PX; Li, KC; Yang, HJ; et al. Graphene oxide triggers toll-like receptors/autophagy responses in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014, 3(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonticoli, L; Diomede, F; Nanci, A; Fontana, A; Della Rocca, Y; Guadarrama Bello, D; et al. Enriched Graphene Oxide-Polypropylene Suture Threads Buttons Modulate the Inflammatory Pathway Induced by Escherichia coli Lipopolysaccharide. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J; Kim, YS; Lim, MY; Kim, HY; Kong, S; Kang, M; et al. Dual Roles of Graphene Oxide to Attenuate Inflammation and Elicit Timely Polarization of Macrophage Phenotypes for Cardiac Repair. ACS Nano 2018, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouve, M; Carpentier, R; Kraiem, S; Legrand, N; Sobolewski, C. MiRNAs in Alcohol-Related Liver Diseases and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Step toward New Therapeutic Approaches? Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, JL; Novo-Veleiro, I; Manzanedo, L; Suárez, LA; MacÍas, R; Laso, FJ; et al. Role of microRNAs in alcohol-induced liver disorders and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018, 24(36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, CJ; Schmidt, S; Özkul, D; Gaiser, C; Terracciano, L; Krähenbühl, S; et al. Identification of mir-199a-5p, mir-214-3p and mir-99b-5p as fibrosis-specific extracellular biomarkers and promoters of hsc activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J; Gao, Y; Duan, L; Wei, S; Liu, J; Tian, L; et al. Metformin ameliorates skeletal muscle insulin resistance by inhibiting miR-21 expression in a high-fat dietary rat model. Oncotarget 2017, 8(58). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNA name | Sequence 5’-3’ |

| miRNA21-5p | TAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGAAAA |

| miRNA203a-3p | GTGAAATGTTTAGGACCACTAGAA |

| miRNA214-3p | CAGGCACAGACAGGCAG |

| miRNA122-5p | TGGAGTGTGACAATGGTGTTTG |

| miRNA22-5p | AGTTCTTCAGTGGCAAGCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).