Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- orthophoto or georeferenced aerial images,

- georeferenced 3D point cloud,

- digital elevation model (DEM).

Geo-Registration/Localisation with Orthophotos or Georeferenced Aerial Images.

Geo-Registration/Localisation with Georeferenced 3D Point Clouds.

DEM- Based Geo-Registration/Localisation.

Final Comments

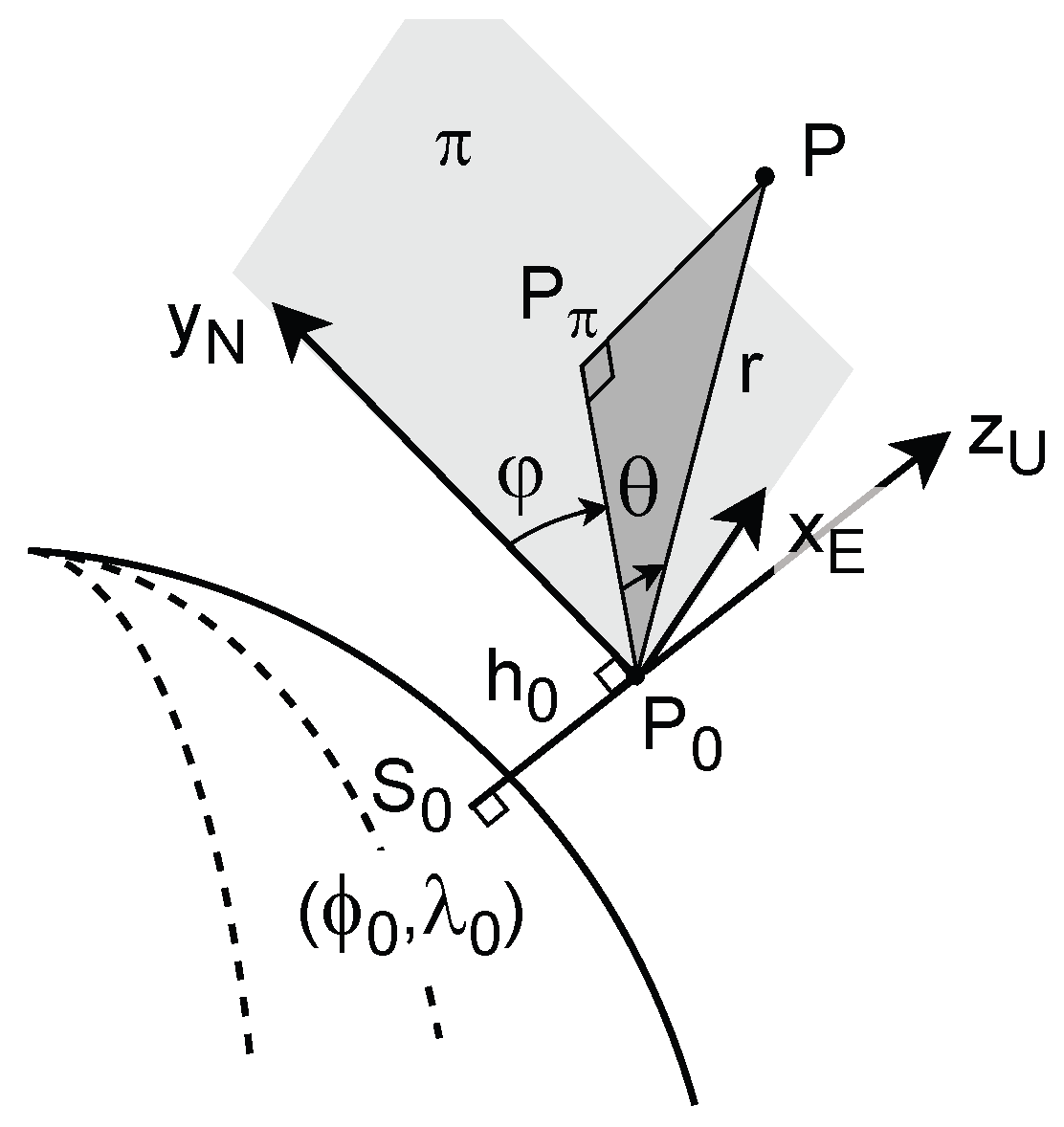

3. Local Azimuth-Elevation Map at Camera Position

3.1. Scenario

3.2. The ENU and AER Local Coordinate Systems

- Up is the direction of the vector , denoted by in Figure 2.

- North is the direction at of the meridian, i.e. the ellipse through the geodetic North. It is taken positive towards the geodetic North . In Figure 2, it is represented in the plane parallel to , and denoted by .

- East is the direction orthogonal to the two other ones and so that ENU is a right-handed system. It is denoted by in Figure 2.

- the azimuth is the clockwise angle from the axis to the direction ;

- the elevation (or altitude) is the angle between the plane and the direction , positive up, negative down;

- (slant) range r is the Euclidean distance between the points and P.

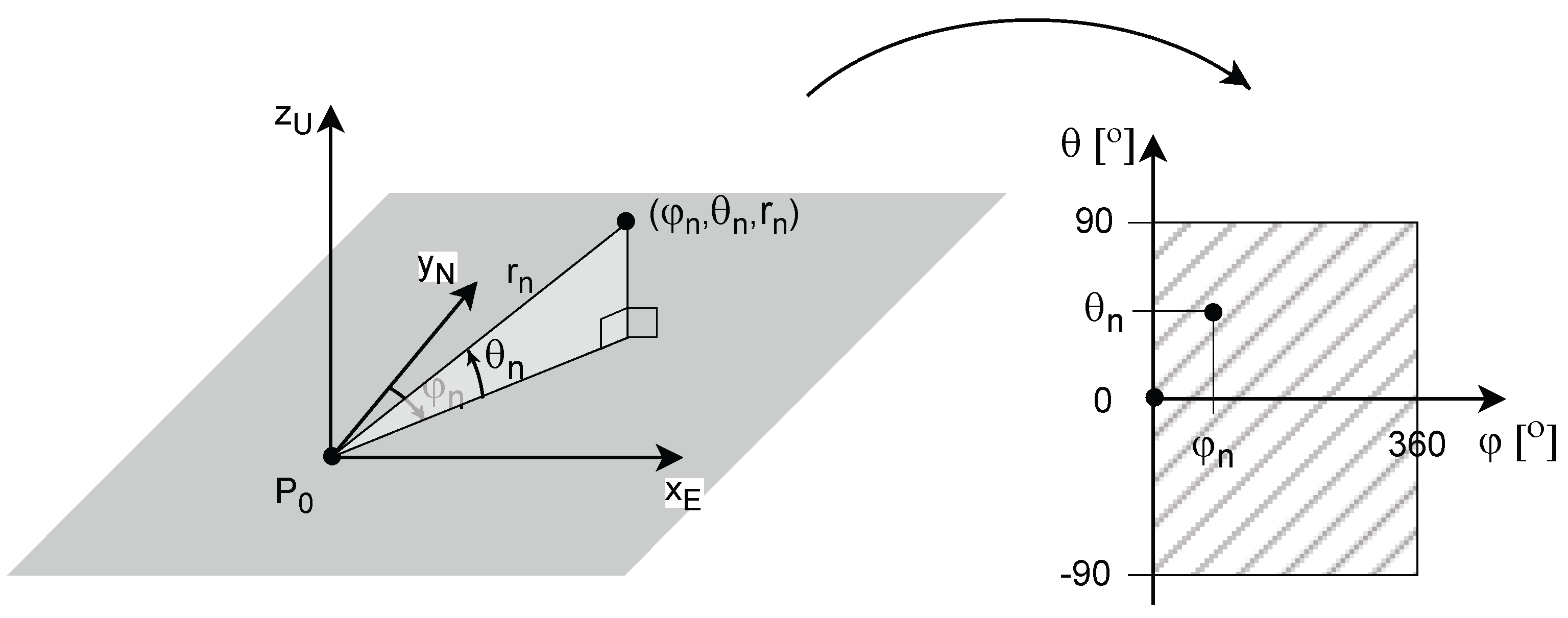

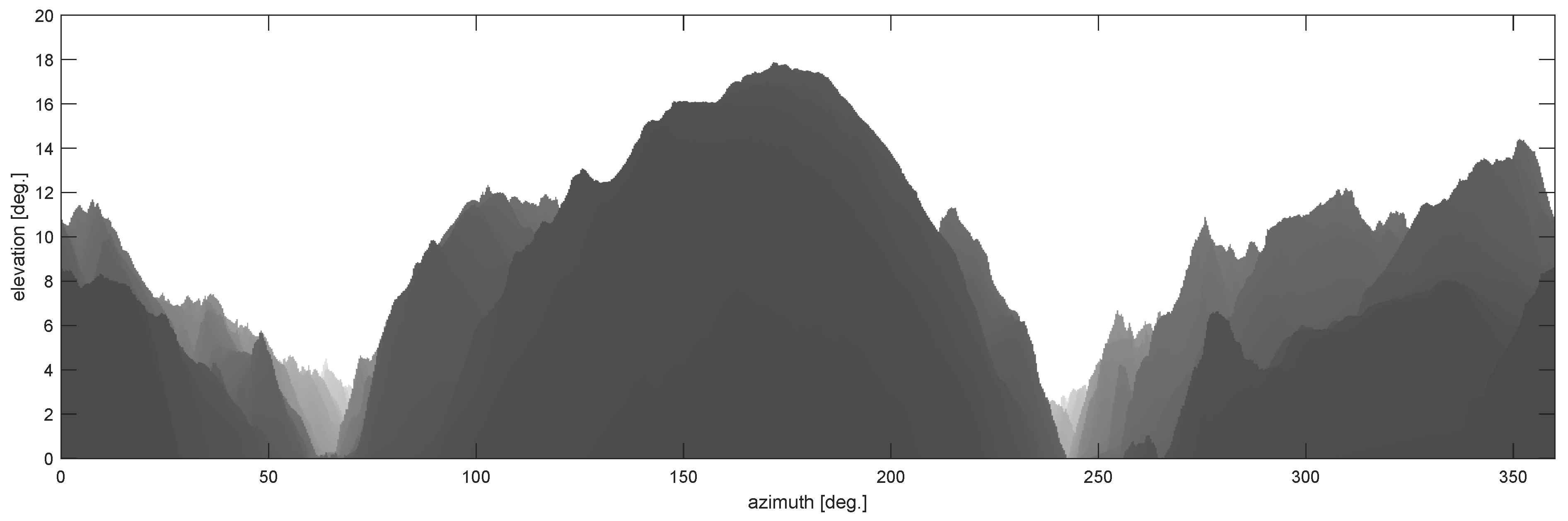

3.3. Local Azimuth-Elevation Map (LAEM)

3.3.1. Mapping to the Azimuth-Elevation Space

- the formula to derive the image coordinates from the AER coordinates of the 3D point is different from the one for deriving the normalised camera image coordinates from the camera centric Cartesian coordinates ,

- a line segment, the endpoints of which map to different points, does not map into a line segment.

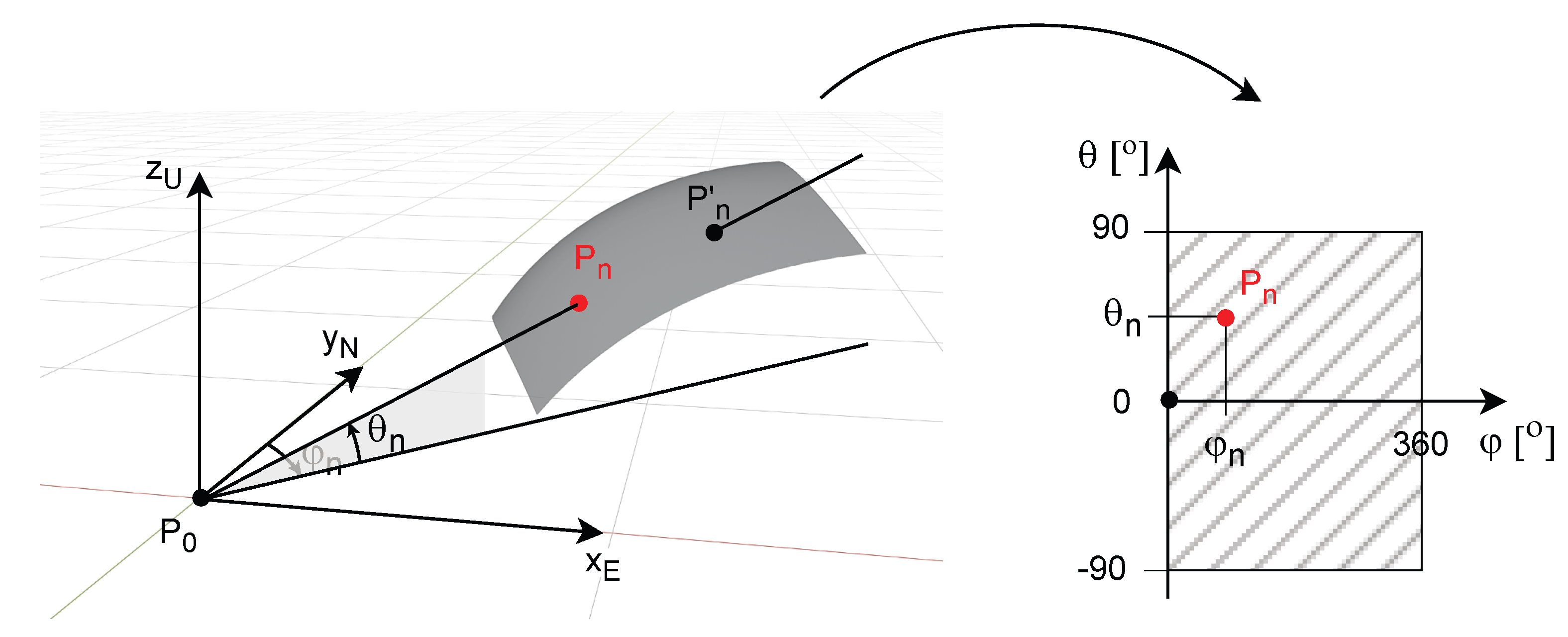

3.3.2. LAEM of a Surface

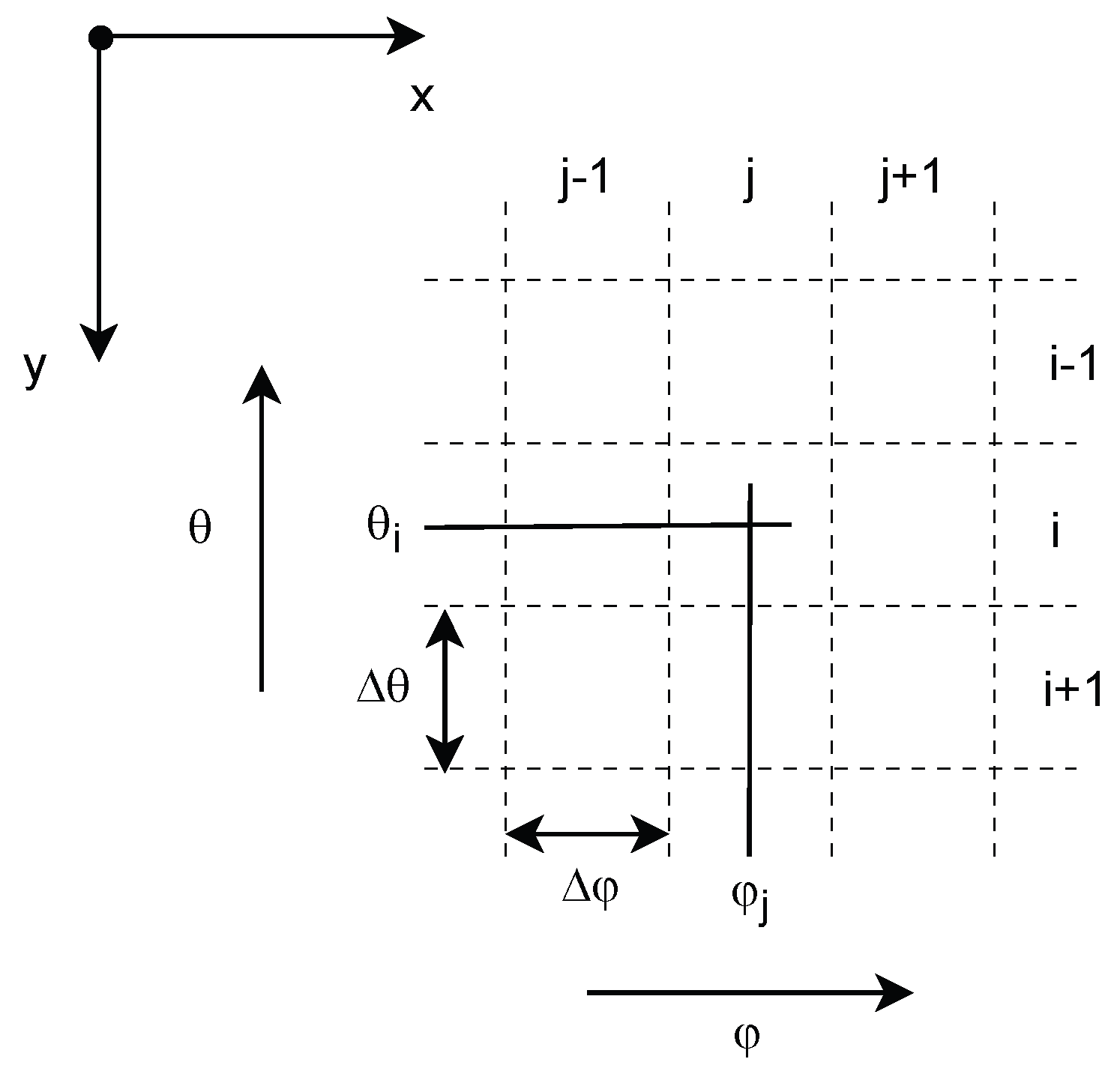

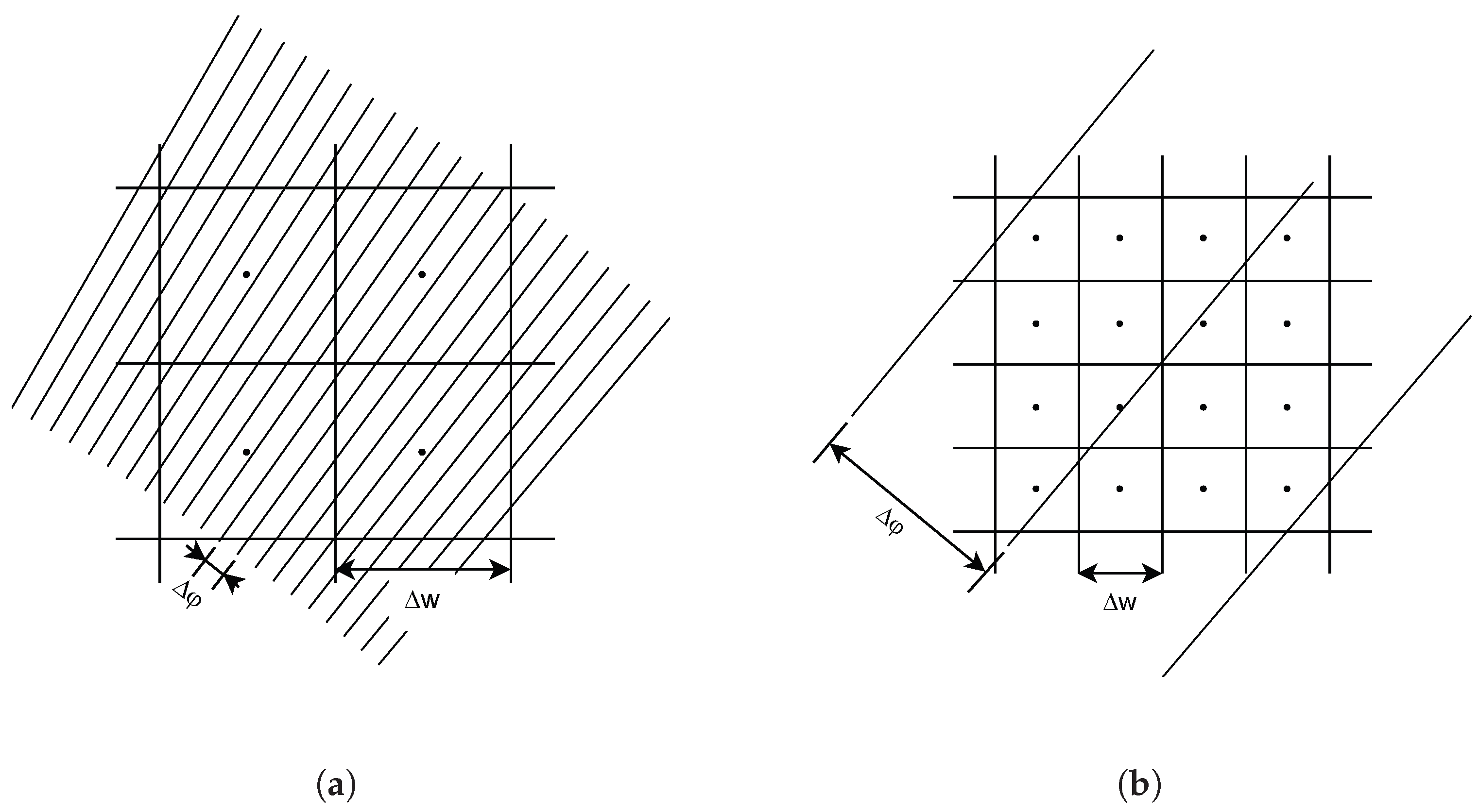

3.3.3. Discrete LAEM

3.4. Computing a Discrete LAEM of a Gridded DEM

3.4.1. Methods from Surface Rendering

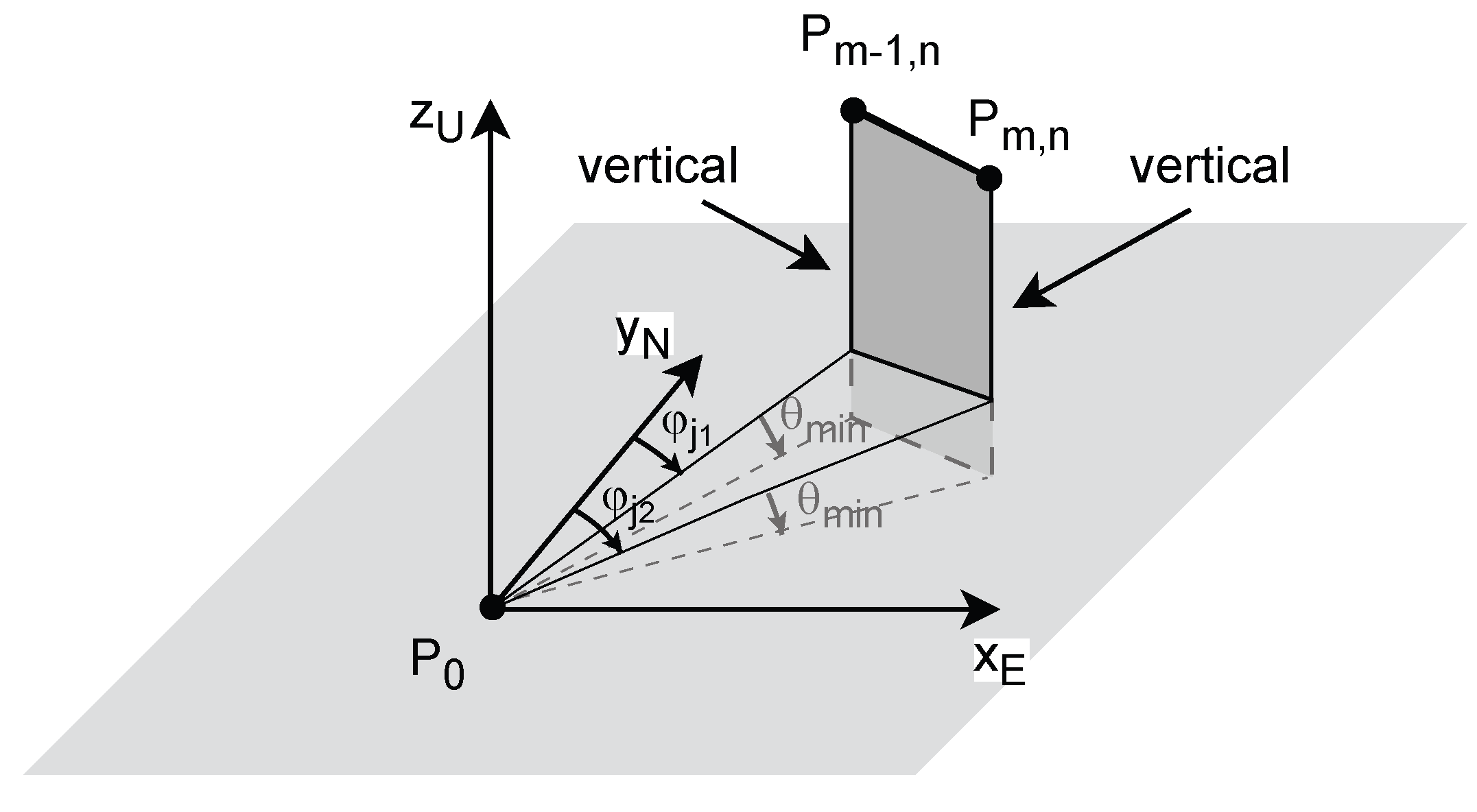

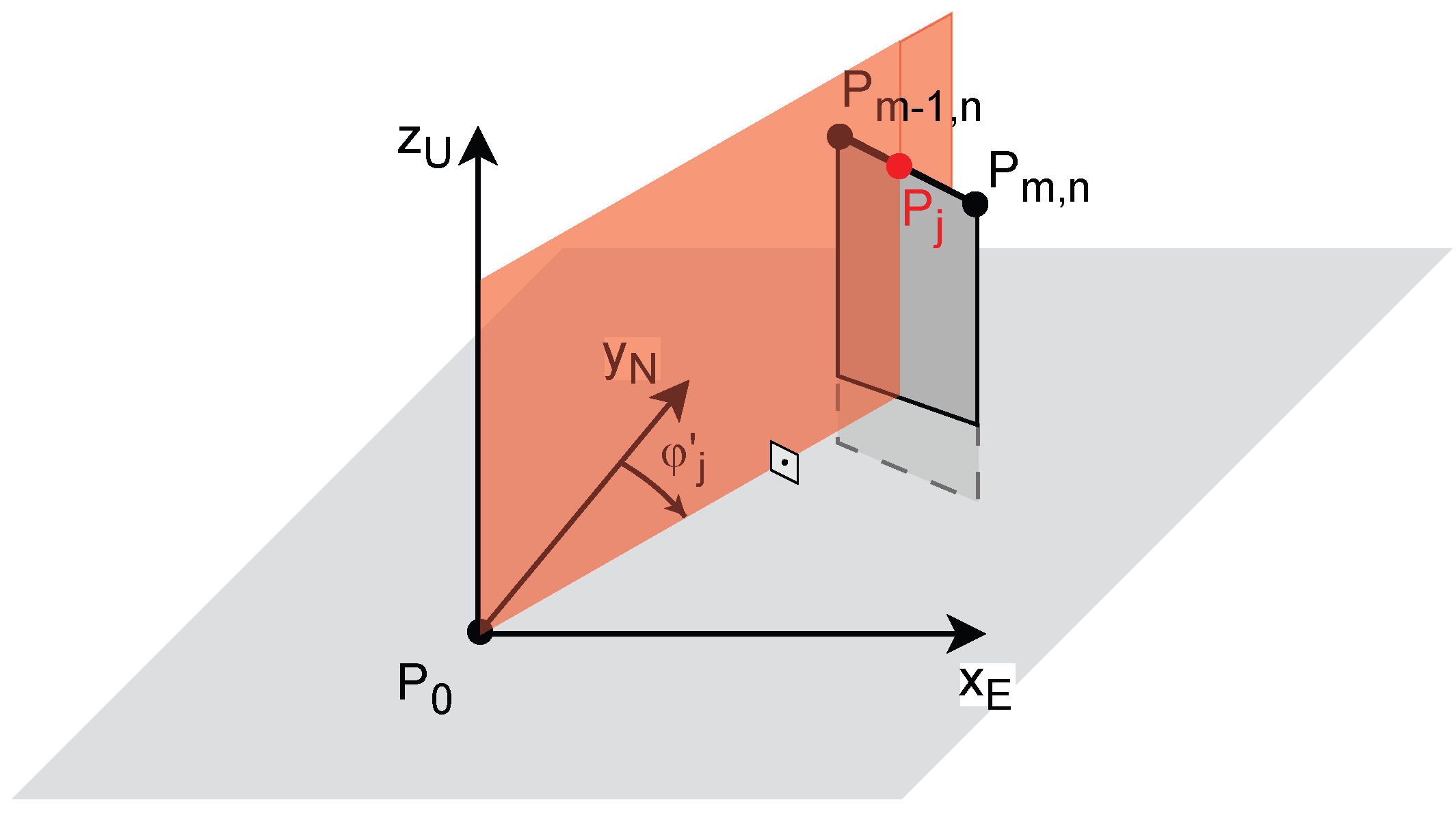

3.4.2. Proposed Method: Principle

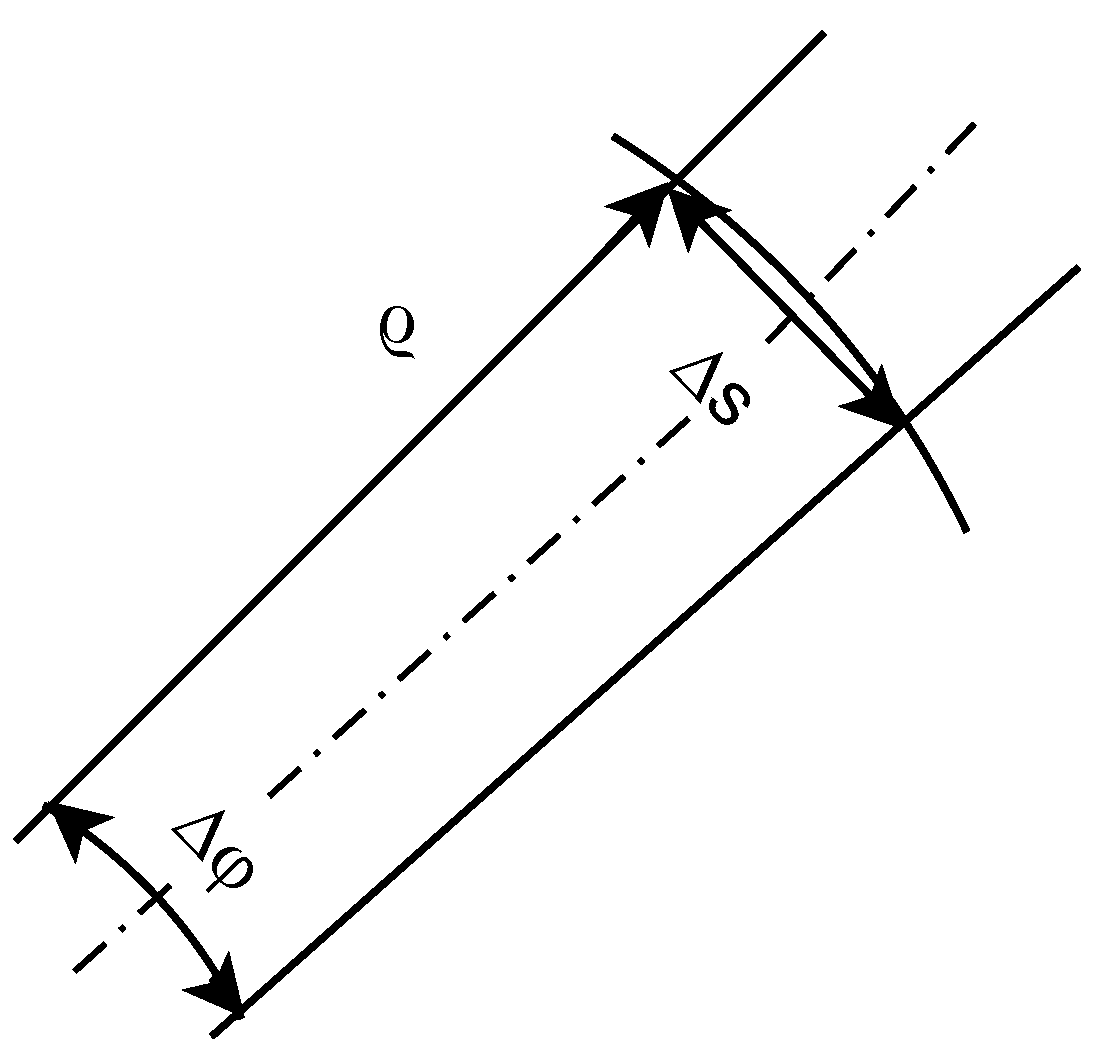

3.4.3. Computing DEM vertical lines

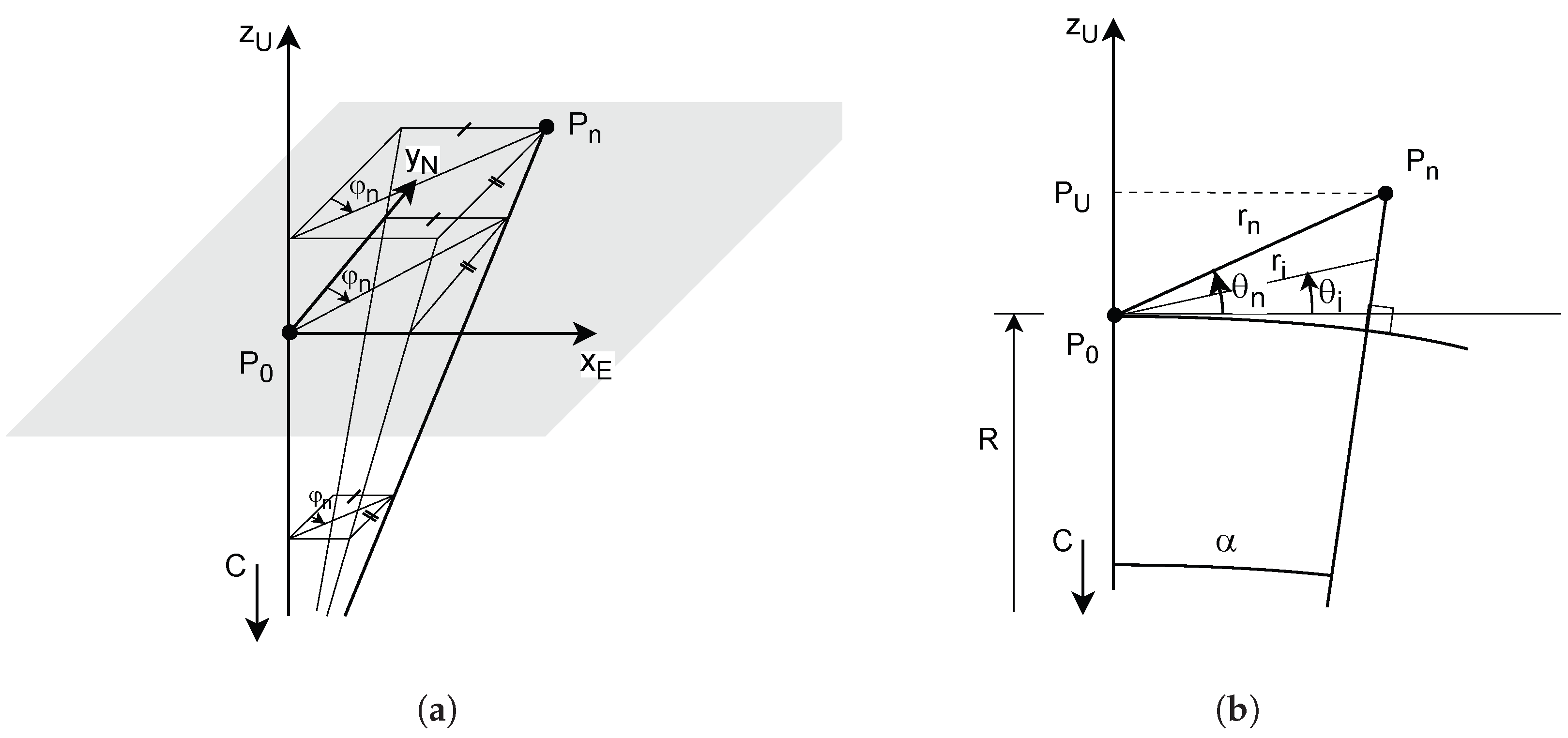

Planar Horizontal Datum

Spheric horizontal datum.

Maximal Errors in Vertical Direction

3.4.4. Detailed Method Description

| Listing 1. LAEM computation | ||

| 1 | % compute coordinates of DEM points | |

| 2 | for each : | |

| 3 | compute | |

| 4 | % add coordinates of interpolation points | |

| 5 | for each : | |

| 6 | for each and each : | |

| 7 | compute making use of (14a), (13b), (13c), and (13d) | |

| 8 | % fill the LAEM | |

| 9 | ||

| 10 | for each : | |

| 11 | if : | |

| 12 | for each : | |

| 13 | % spheric approximation | %planar approximation |

| 14 | compute with equation (19) | nop |

| 15 | ||

- line 3:

- The values , , and result directly from the representation of in the AER coordinate system. represents either the horizontal distance (planar approximation) or slant range (spheric approximation) of . and determine the position of in the LAEM. They are derived from the azimuth and the elevation of according to the choices that have been made in Section 3.3.3 for the discretisation of the space. The equations are:where is the unwrapped azimuth angle, related to the azimuth angle by:

- line 7:

- The interpolation has been explained in Section 3.4.2 and illustrated in Figure 7. j determines the discrete unwrapped azimuth angle . The explicit equations (14a), (13b), (13c), and (13d) allow to compute from the ENU coordinates of the interpolation point between and , respectively between and . From the ENU coordinates of the interpolation point, the corresponding and values are derived with the ENU to AER coordinate transform. Finally, , determining together with j the position of in the LAEM, is computed from by equation (20b). This new coordinate triplet is added to the set (or list) of coordinates that will be browsed to fill the LAEM.

- lines

- 9 and 11: According to Section 3.3.2, from the points having same LAEM position, we keep only the "visible" one, i.e. the one with smallest d value. The LAEM is hence initialised at line 9 with a specific value, larger than any possible d value, here the choice . Furthermore at line 11, the position of the currently evaluated point is only updated, if the value is smaller than the value stored in at this position.

- lines

- 12 to 15: together with determine the position of the currently evaluated DEM point. The following i values, each together with , determine the LAEM positions of 3D points located on the vertical line down from the DEM point. According to Section 3.4.3, they have the same azimuth and hence the same j value. Moreover, in the case of the planar approximation, they have the same horizontal distance value as the as the DEM point, i.e. . In the case of the spheric approximation, the point slant range is computed from by equation (19). The LAEM is updated with these respective values: and . Note that it is not necessary to test if the d value of the points on the vertical line is smaller than the value existing in the LAEM at that position, because the truth follows directly from the truth of the condition for the DEM point.

3.4.5. DEM Downsampling as Preprocessing

4. Implementation and Experimental Results

4.1. The swissALTI3D DEM

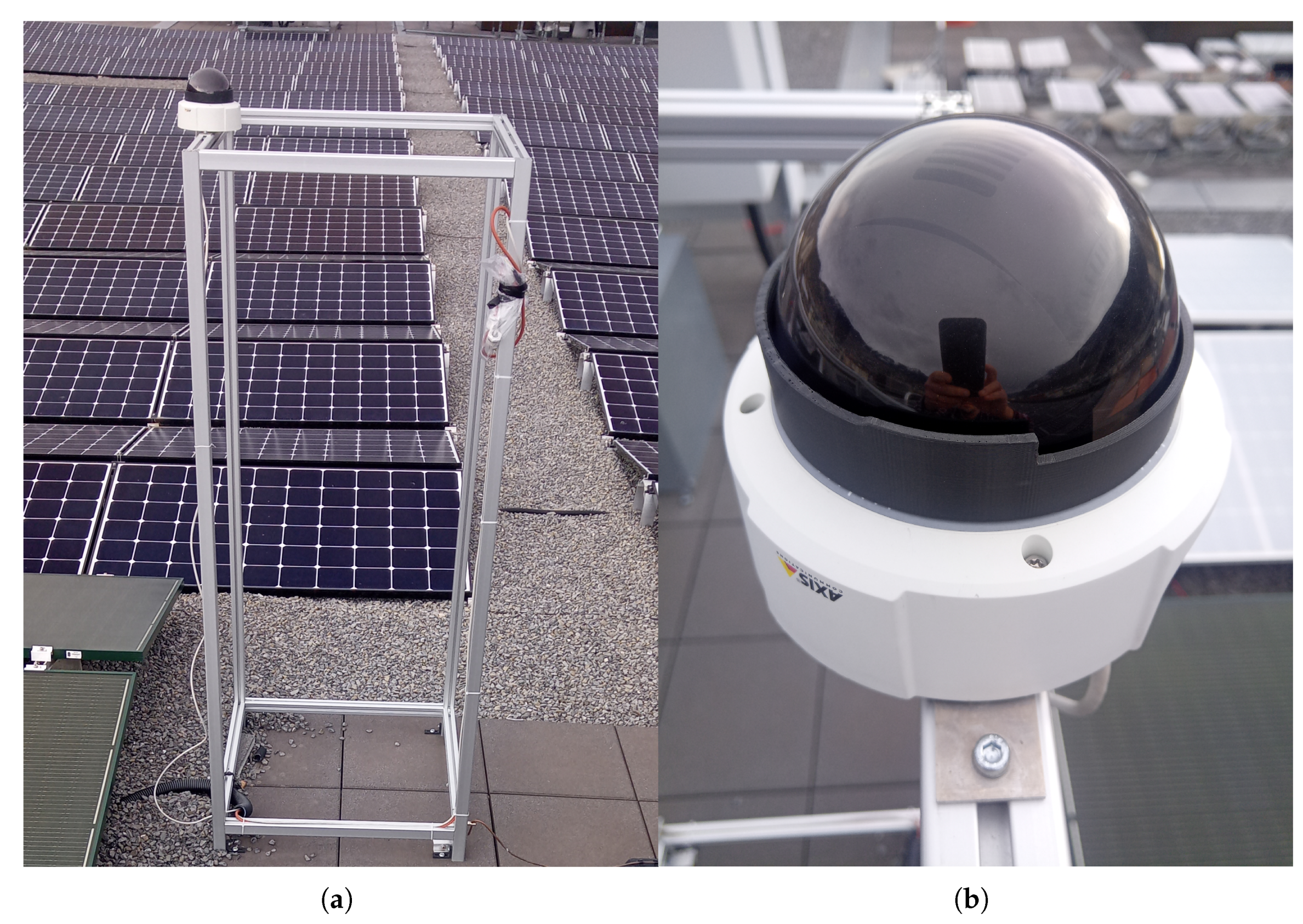

4.2. Camera Set-Up and Images

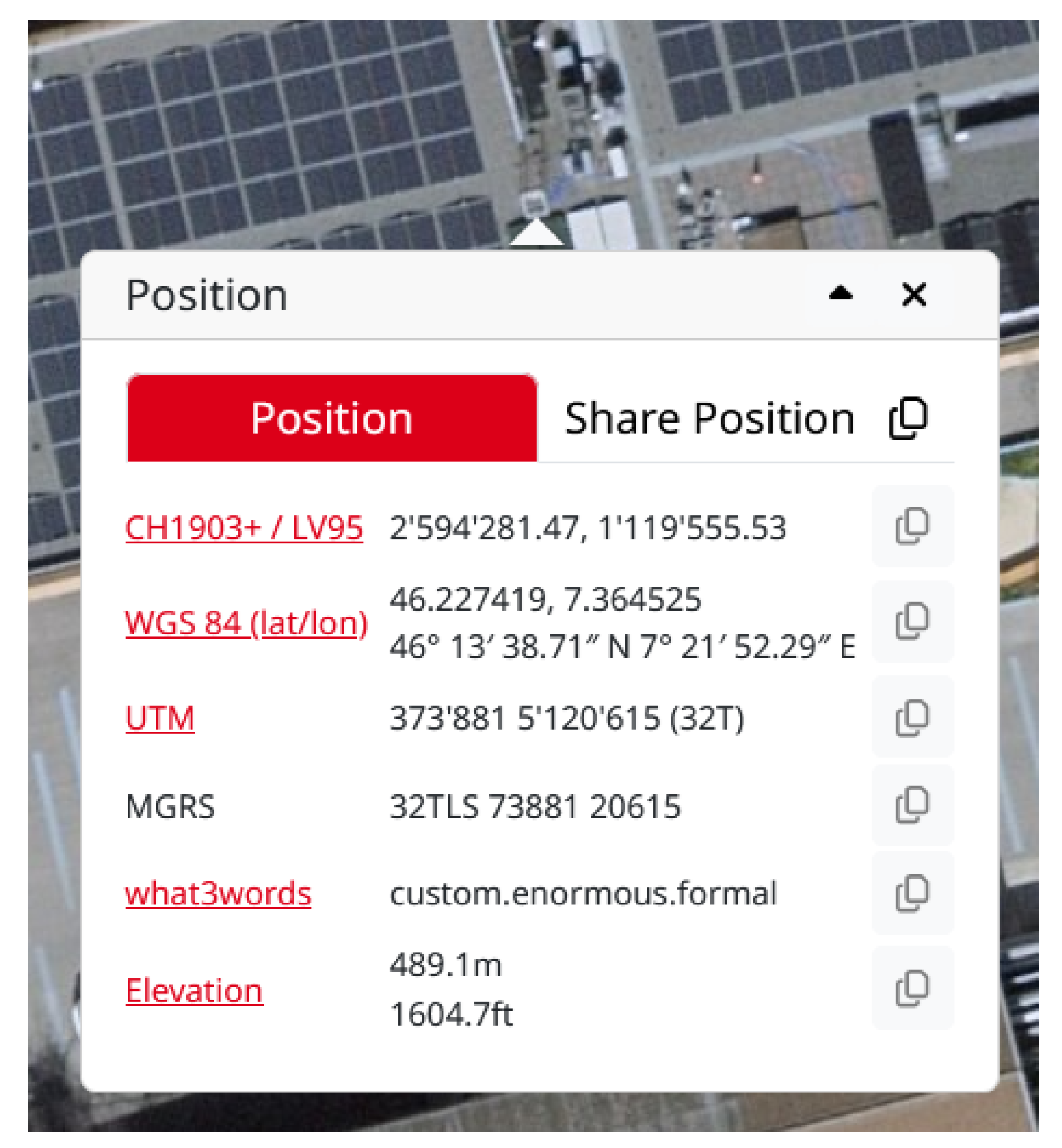

4.3. Determining the Camera Position

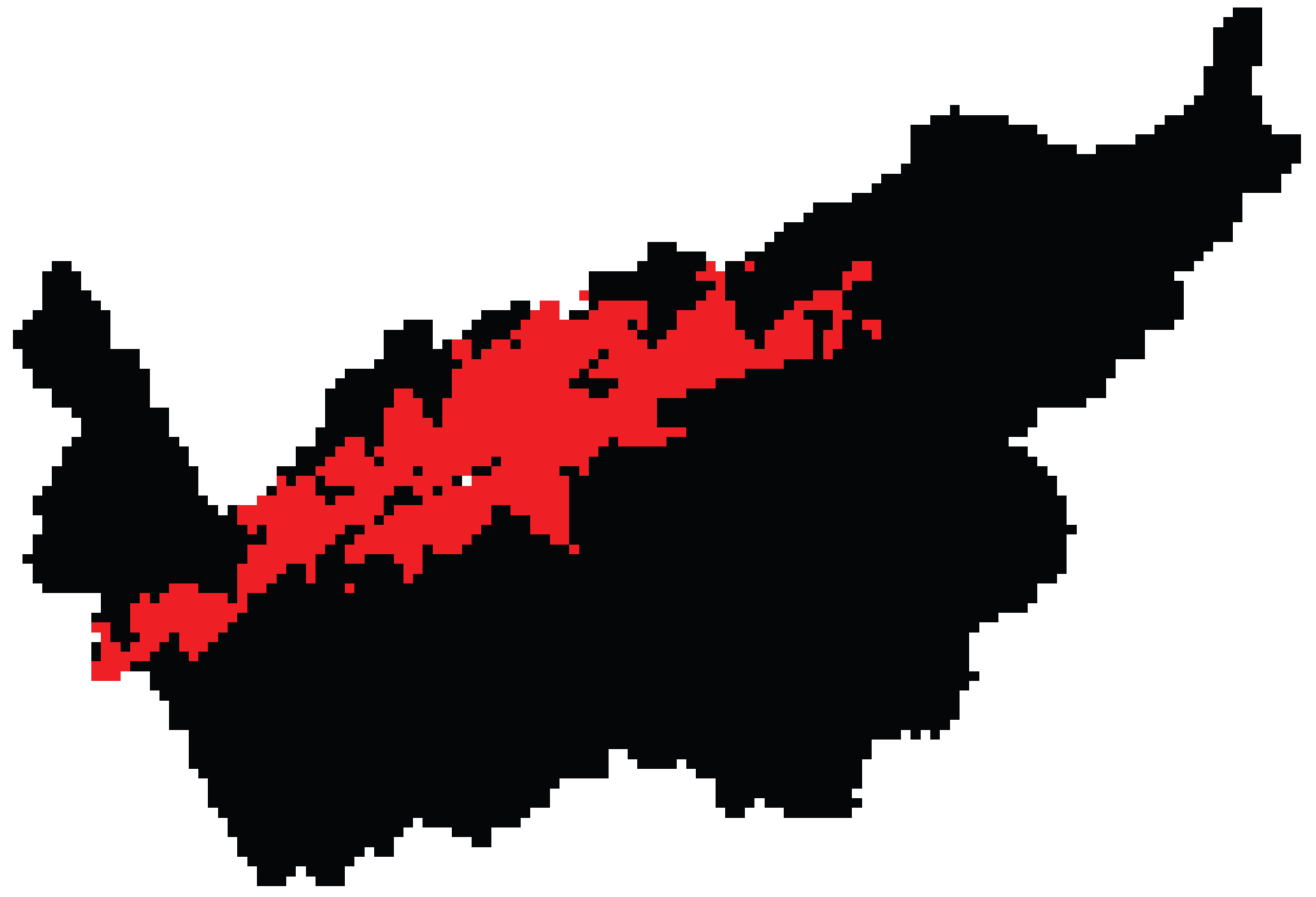

4.4. Preselection and Download of the DEM tiles

4.5. LAEM Computation

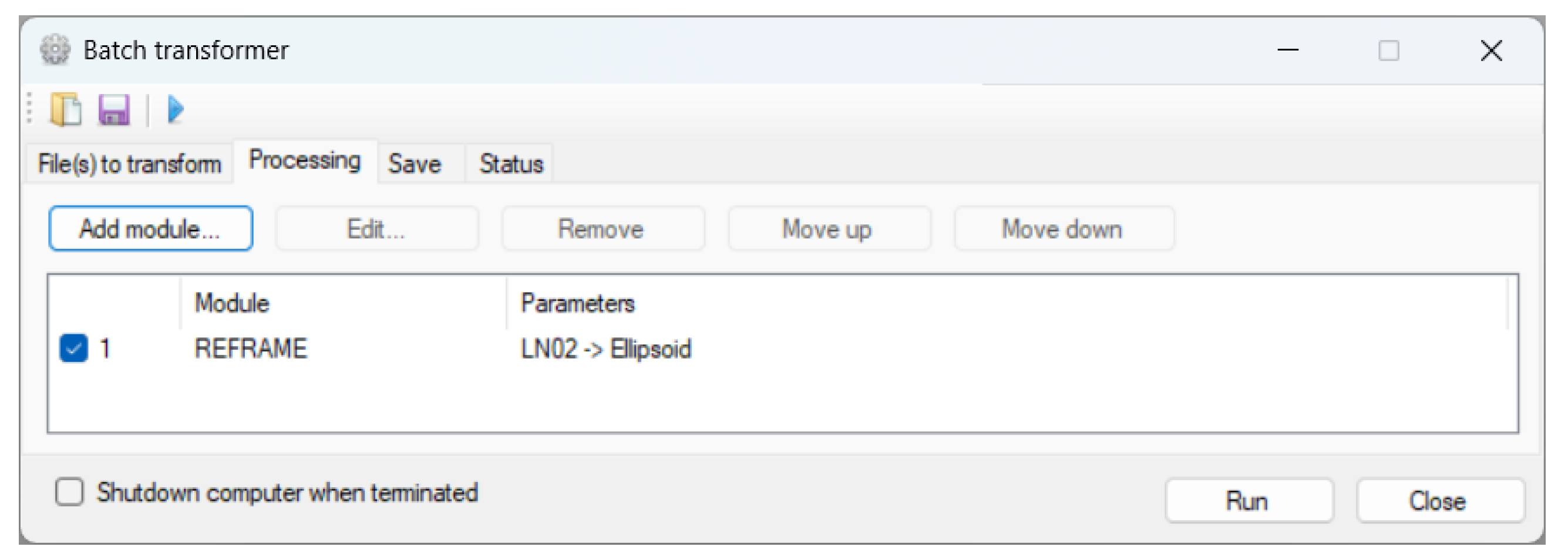

4.5.1. Computation of the Geodetic Coordinates

4.5.2. Tile-Level Processing

| Listing 2. Tile-level processing | |

| 1 | for each tile : |

| 2 | determine |

| 3 | if , current tile is |

| 4 | for each tile in : |

| 5 | determine |

| 6 | build B according to equation (23) |

| 7 | compute for each |

| 8 | compute with equation (24) |

- line 2:

- are easy to determine. If the tile format is ASCII XYZ, they can be determined directly from the file name. If the tile format is COG, they can also be found in the file metadata.

- line 3:

- If the LV95 coordinates of the camera satisfy this condition, the camera position is within the tile currently considered. This tile is denoted by . As explained hereinbefore, adjacent tiles do not have common extremal coordinates, so that the camera position cannot be in more than one tile. In contrary, it can happen that the camera position is between two adjacent tiles. In this case, is simply the empty set ∅.

- line 5:

- Extremal height values and (either LN02 or geodetic, depending on the file content) can be easily determined by scanning once the file. Performing the processing with original tiles, containing LN02 heights, we increase by a safety margin of e.g. 20 meters, in order to ensure not missing visible points when discarding a tile. Having tiles in geodetic heights, can be kept as it is.

- line 6:

- With the extremal coordinate values , and , we build a tile bounding box, which is a rectangular cuboid in the coordinate systems LV95/height. For the reason that will become clear further, we do not only use the 8 vertices of the rectangular cuboid, but also the edges. The set of coordinates is hence:

- line 7:

- The coordinates of the points belonging to B are transformed into the values , , and d of the local coordinate system, where d is the horizontal distance in the case of the plane approximation of the DEM horizontal datum and d is the slant range r in the case of the spheric approximation. Note that the height is not transformed from LN02 to geodetic. It is kept in the same height coordinate system as the tile.

- line 8:line 8:

-

Following extremal , , and d values are computed for the points belonging to B:We use T for tile in the notation in order to not confuse these and values with the extreme LAEM azimuth and elevation values introduced in Section 3.3.3.Without demonstration, we claim that the values , , and of any tile point P satisfy:Note that the statement is not true, if B is reduced to the 8 vertices of the rectangular cuboid.

4.5.3. LAEM Computation with Tile Sorting and Filtering

| Listing 3. LAEM computation with tile sorting and filtering | |

| 1 | %Initialise and |

| 2 | , |

| 3 | update and with |

| 4 | for each tile in sorted ascending according to : |

| 5 | compute |

| 6 | compute |

| 7 | if : |

| 8 | update and with |

- lines

- 3 and 8: The update of is performed in the way described in listing 1. The update of is simply performed in inserting the following instruction after the line 11 of listing 1: if .

- line 4:

- Doing the processing without sorting the tiles would give the same final LAEM but would necessitate to process more tiles.

- line 5:

- From and , the indexes of the corresponding discrete azimuth values and are computed using the equations (21) and (20a). From , the index of the corresponding discrete elevation value is computed using the equation (20b).

- line 6:

-

These are extremal values in the section going from to of the apparent horizon . is the minimal elevation in the section, formally:is the maximal LAEM value in the section, formally:

- line 7:

- This is the formal expression of the condition expressed with words at section start.

4.6. Results

5. Discussion

- It contains only and totally the portion of a DEM which is visible from a given position.

- It is not a subset in any order, but DEM points are arranged with a spatial consistency.

- The dimensionality is reduced from 3D to 2D. The LAEM is comparable to an image of the DEM but with the distance information (horizontal distance or slant range r) and another 2D coordinate system.

- The scalar value in the 2D space, the slant range r in the spheric approximation case, is rotation invariant.

- Depth

- map The LAEM is a depth map, it is similar to the output of a LiDAR. Techniques from the fusion of LiDAR and camera data [70] can be used. In particular, one could work on the similarity between discontinuities [71] of the LAEM and image edges [9]. Note that this is a generalisation of the approach used by Portenier et al. [38], who used the similarity of the apparent horizon in the image and the one in a synthetic image generated from the DEM.

- GIS

- augmented LAEM The final goal of the camera calibration is the georeferencing of the camera image to be able to enrich the image with GIS information. Changing the ordering of the procedure, i.e. starting by enriching the LAEM with GIS information, e.g. roads, public lights,…could help in finding correspondences between the camera image and the LAEM. The use of an orthophoto to complement the LAEM, the drawback of which has been discussed in Section 2, would also belong to this approach.

- Self-

- calibration In the case of a PTZ camera, a self-calibration can be performed. With it comes along a 3D point cloud. The camera pose is relative to this 3D point cloud. It is then possible to align the 3D point cloud with the LAEM and, by the way, get the pose of the camera in a geographic coordinate system. For aligning the 3D point cloud generated by the self-calibration with the LAEM, the well-known RANSAC algorithm [9] can be used. Another idea is to transform the 3D point cloud in AER coordinates and use the rotation invariance of the range component r and the LAEM value to preselect points which can correspond to each other.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| AER | azimuth-elevation-range |

| ASCII | American Standard Code for Information Interchange |

| COG | Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| ECEF | Earth-centred, Earth-fixed |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. |

| FOV | field of view |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GRS80 | Geodetic Reference System 1980 |

| LGH | Local Geodetic Horizon |

| LGHS | Local Geodetic Horizon System |

| LAEM | Local Azimuth-Elevation Map |

| LN02 | Swiss national levelling network 1902 |

| LV95 | Swiss national survey coordinate system 1995 |

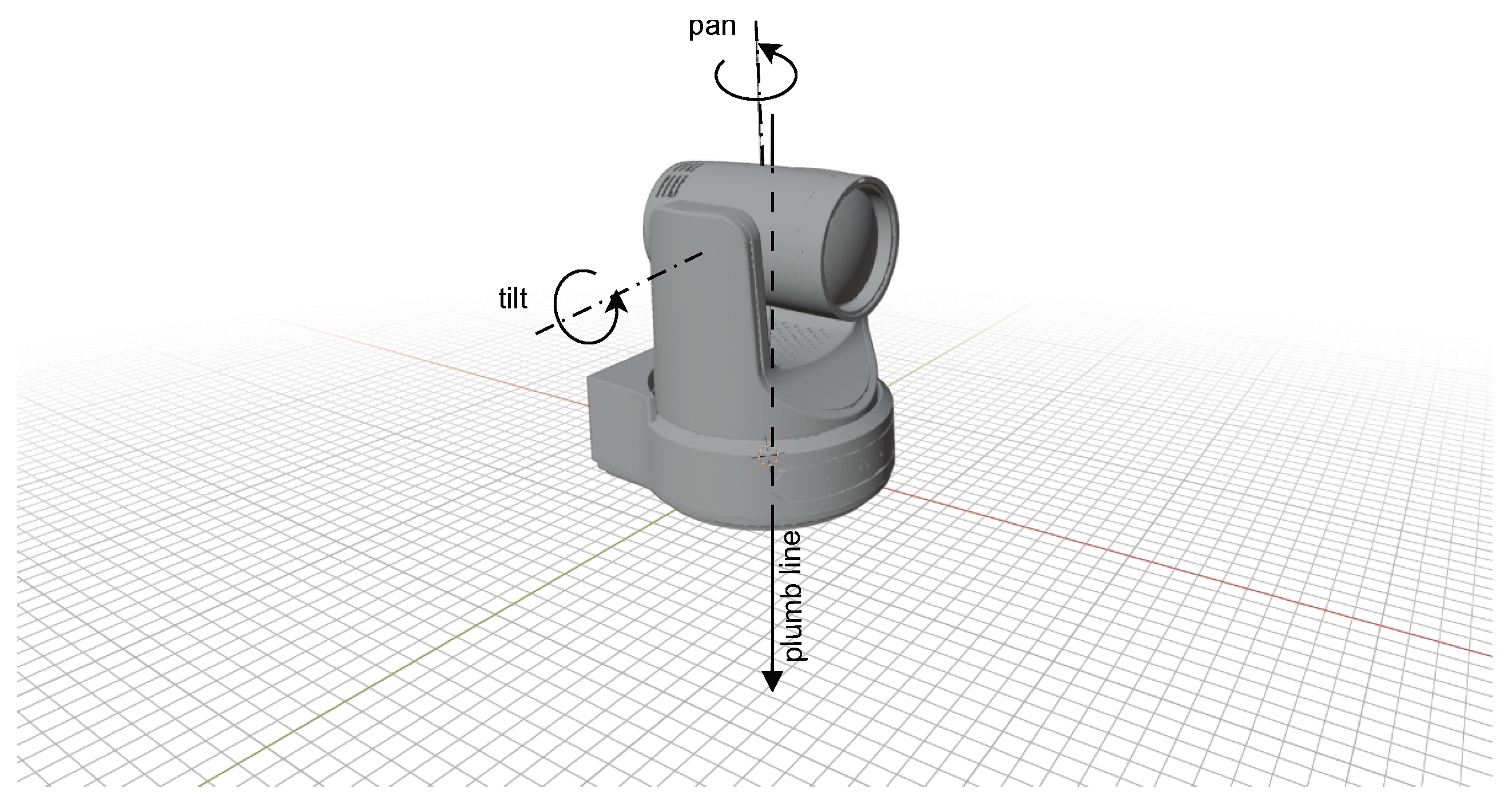

| PTZ | pan-tilt-zoom |

| ROI | region of interest |

References

- Meyer, T. Grid, ground, and globe: Distances in the GPS era. Surveying and Land Information Systems 2002, 62, 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle, J. Basic GIS coordinates, third edition ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, J.T.; Hill, L.L. Georeferencing. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems; Liu, L., Özsu, M.T., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2009; pp. 1246–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, X. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of GIS, 2 ed.; Springer Cham, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.L.; Van Niekerk, A.; Grohmann, C.H.; Muller, J.P.; Hawker, L.; Florinsky, I.V.; Gesch, D.; Reuter, H.I.; Herrera-Cruz, V.; Riazanoff, S.; et al. Digital Elevation Models: Terminology and Definitions. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. swissALTI3D. Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/height-model-swissalti3d (accessed on 2025-11-01).

- EuroGeographics AISBL. Open Maps for Europe | Eurogeographics. Available online: https://www.mapsforeurope.org/datasets/euro-dem (accessed on 2025-10-30).

- McGlone, J.C. (Ed.) Manual of photogrammetry, sixth ed.; American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing: Bethesda, Md, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Szeliski, R. Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications, 2nd ed.; 2022; Available online: https://szeliski.org/Book (accessed on 2025-11-03).

- Hartley, R.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenine-Möller, T.; Haines, E.; Hoffman, N.; Pesce, A.; Iwanicki, M.; Hillaire, S. Real-Time Rendering 4th Edition; A K Peters/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 1200. [Google Scholar]

- Huai, J.; Shao, Y.; Jozkow, G.; Wang, B.; Chen, D.; He, Y.; Yilmaz, A. Geometric Wide-Angle Camera Calibration: A Review and Comparative Study. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slama, C.C. (Ed.) Manual of photogrammetry, fourth ed.; American Society for Photogrammetry: Falls Church, Va, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bösch, J.; Goswami, P.; Pajarola, R. RASTeR: Simple and Efficient Terrain Rendering on the GPU. In Proceedings of the Eurographics 2009 - Areas Papers; Ebert, D., Krüger, J., Eds.; The Eurographics Association, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; Fraser, C. Digital camera calibration methods: considerations and comparisons. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ISPRS Commission V Symposium ’Image Engineering and Vision Metrology’; Maas, H.G., Schneider, D., Eds.; International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing: Dresden, Germany, 2006; pp. 266–272. Available online: https://www.isprs.org/proceedings/xxxvi/part5/paper/remo_616.pdf (accessed on 2025-11-08).

- Hieronymus, J. Comparison of methods for geometric camera calibration. ISPRS-Archives 2012, XXXIX-B5, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, J.; Armangué, X.; Batlle, J. A comparative review of camera calibrating methods with accuracy evaluation. Pattern Recognition 2002, 35, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Dongri, S. Review of camera calibration algorithms. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computer Communication and Computational Sciences; Bhatia, S.K., Tiwari, S., Mishra, K.K., Trivedi, M.C., Eds.; Singapore, 2019; pp. 723–732. [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel, F.; Kroo, R. Digital close-range photogrammetry using artificial targets. In Proceedings of the XVIIth ISPRS Congress Technical Commission V: Close-Range Photogrammetry and Machine Vision; Fritz, L.W., Lucas, J.R., Eds.; 1992; Vol. XXIX Part B5, pp. 222–229. Available online: https://www.isprs.org/proceedings/xxix/congress/part5/222_XXIX-part5.pdf (accessed on 2025-11-08).

- Wang, W.; Pang, Y.; Ahmat, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, A. A novel cross-circular coded target for photogrammetry. Optik 2021, 244, 167517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, T. Eccentricity in images of circular and spherical targets and its impact on spatial intersection. Photogram Rec 2014, 29, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.; Maruyama, S. Eccentricity on an image caused by projection of a circle and a sphere. ISPRS-Annals 2016, III-5, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. A Flexible New Technique for Camera Calibration. techreport MSR-TR-98-71, Microsoft Research: Redmond, Wa, 1998.

- Zhang, Z. A flexible new technique for camera calibration. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV team. OpenCV: Camera Calibration. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.12.0/dc/dbb/tutorial_py_calibration.html (accessed on 2025-11-02).

- The MathWorks; Inc. Camera Calibration - MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/vision/camera-calibration.html (accessed on 2025-11-02).

- Faugeras, O.D.; Luong, Q.T.; Maybank, S.J. Camera self-calibration: Theory and experiments. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV’92; Sandini, G., Ed.; Berlin, Heidelberg, 1992; pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, Q.T.; Faugeras, O.D. Self-Calibration of a Moving Camera from Point Correspondences and Fundamental Matrices. International Journal of Computer Vision 1997, 22, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.S. Digital camera self-calibration. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 1997, 52, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Zhang, X.; Sultani, W.; Wshah, S. Image and Object Geo-Localization. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, 132, 1350–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameau, F.; Choe, J.; Pan, F.; Lee, S.; Kweon, I. CCTV-Calib: a toolbox to calibrate surveillance cameras around the globe. Machine Vision and Applications 2023, 34, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Wu, C.; Curless, B.; Furukawa, Y.; Hernandez, C.; Seitz, S.M. Accurate Geo-Registration by Ground-to-Aerial Image Matching. In Proceedings of the 2014 2nd International Conference on 3D Vision, 2014, Vol. 1, pp. 525–532. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Snavely, N.; Huttenlocher, D.; Fua, P. Worldwide Pose Estimation Using 3D Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision - ECCV 2012; Fitzgibbon, A.; Lazebnik, S.; Perona, P.; Sato, Y.; Schmid, C., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 15–29. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Snavely, N.; Huttenlocher, D.P. Location Recognition Using Prioritized Feature Matching. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision - ECCV 2010; Daniilidis, K.; Maragos, P.; Paragios, N., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 791–804. [CrossRef]

- Sattler, T.; Leibe, B.; Kobbelt, L. Fast image-based localization using direct 2D-to-3D matching. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, 2011; pp. 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härer, S.; Bernhardt, M.; Corripio, J.G.; Schulz, K. PRACTISE - Photo Rectification And ClassificaTIon SoftwarE (V.1.0). Geoscientific Model Development 2013, 6, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljević, A.; Rančić, D.; Dimitrijević, A.; Predić, B.; Mihajlović, V. A Method for Estimating Surveillance Video Georeferences. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portenier, C.; Hüsler, F.; Härer, S.; Wunderle, S. Towards a webcam-based snow cover monitoring network: methodology and evaluation. The Cryosphere 2020, 14, 1409–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PTZOptics. CAD Line Drawings and 3D Renders - PTZOptics. Available online: https://ptzoptics.com/cad-line-drawings/ (accessed on 2025-11-25).

- Google. Google Maps. Available online: https://maps.google.com (accessed on 2025-10-30).

- The MathWorks, Inc. Comparison of 3-D Coordinate Systems - MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/choose-a-3-d-coordinate-system.html (accessed on 2025-11-19).

- The MathWorks, Inc. geodetic2enu - Transform geodetic coordinates to local east-north-up - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/geodetic2enu.html (accessed on 2025-11-19).

- pymap3d.enu API documentation. Available online: https://geospace-code.github.io/pymap3d/enu.html#pymap3d.enu.geodetic2enu (accessed on 2025-11-19).

- The MathWorks; Inc. enu2geodetic - Transform local east-north-up coordinates to geodetic - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/enu2geodetic.html (accessed on 2025-12-05).

- pymap3d.enu API documentation. Available online: https://geospace-code.github.io/pymap3d/enu.html#pymap3d.enu.enu2geodetic (accessed on 2025-12-05).

- Roy, A.E.; Clarke, D. Astronomy: principles and practice, 4th ed. ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The MathWorks; Inc. geodetic2aer - Transform geodetic coordinates to local spherical - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/geodetic2aer.html (accessed on 2025-11-19).

- pymap3d.aer API documentation. Available online: https://geospace-code.github.io/pymap3d/aer.html#pymap3d.aer.geodetic2aer (accessed on 2025-11-19).

- The MathWorks; Inc. aer2geodetic - Transform local spherical coordinates to geodetic - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/aer2geodetic.html (accessed on 2025-12-06).

- pymap3d.aer API documentation. Available online: https://geospace-code.github.io/pymap3d/aer.html#pymap3d.aer.aer2geodetic (accessed on 2025-12-06).

- The MathWorks; Inc. Image Coordinate Systems - MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/images/image-coordinate-systems.html (accessed on 2025-12-02).

- OpenCV team. OpenCV: Operations with images. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.12.0/d5/d98/tutorial_mat_operations.html#autotoc_md342 (accessed on 2025-12-02).

- Roth, S.D. Ray casting for modeling solids. Computer Graphics and Image Processing 1982, 18, 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikimedia Foundation. Extremes on Earth - Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extremes_on_Earth#Greatest_vertical_drop (accessed on 2025-12-14).

- Holton, T. Digital Signal Processing: Principles and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. The Swiss coordinates LV95. 2024). Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/the-swiss-coordinates-system (accessed on 2025-12-21).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Swiss national levelling network LN02. 2025). Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/swiss-national-levelling-network-ln02 (accessed on 2025-12-21).

- Bundesamt für Landestopographie swisstopo. swissALTI3D: Das hoch aufgelöste Terrainmodell der Schweiz. Technical report. In Bundesamt für Landestopographie swisstopo; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Office fédéral de topographie swisstopo. swissALTI3D: Le modèle de terrain à haute résolution de la Suisse. Technical report. In Office fédéral de topographie swisstopo; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Axis Communications, AB. AXIS M5525-E PTZ Network Camera - Product support | Axis Communications. Available online: https://www.axis.com/products/axis-m5525-e/support (accessed on 2025-12-17).

- Maître, G. PTZcalDB public (1.0). In EUDAT Collaborative data infrastructures; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Maps of Switzerland - Swiss Confederation - map.geo.admin.ch. https:map.geo.admin.ch (Accessed on 2025-12-18).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Geoid: The Swiss geoid model CHGeo2004. Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/geoid-en (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. REFRAME. Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/coordinate-conversion-reframe (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. REST web geoservices (REFRAME Web API). Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/rest-api-geoservices-reframe-web (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. REFRAME DLL/JAR. Available online: https://cms.geo.admin.ch/ogd/geodesy/reframedll.zip (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. GeoSuite (LTOP/REFRAME/TRANSINT). Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/geodetic-software-geosuite (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- The MathWorks; Inc. projinv - Unproject x-y map coordinates to latitude-longitude coordinates - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/projcrs.projinv.html (accessed on 2025-12-19).

- The MathWorks; Inc. readgeoraster - Read geospatial raster data file - MATLAB. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/map/ref/readgeoraster.html (accessed on 2025-12-20).

- Thakur, A.; Rajalakshmi, P. LiDAR and Camera Raw Data Sensor Fusion in Real-Time for Obstacle Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Shao, C.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Yan, Y. Discontinuity Identification from Range Data Based on Similarity Indicators. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2011, 44, 3153–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The camera CAD model used in the figure has be downloaded from [39] and rendered with Blender 4.5. |

| planar approximation | spheric approximation | |

| d | ||

| 100 m | 0.000904 | 6.054193e-06 |

| 1 km | 0.009044 | 6.054193e-05 |

| 10 km | 0.090437 | 0.000605 |

| 100 km | 0.904294 | 0.006053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).