1. Introduction

Low-altitude remote sensing images are highly flexible, spatially-resolved, and offer strong timeliness. Thus, they are crucial in virtual geographic environments across fields [

1]. Before the popularity of artificial intelligence, the most common 3D reconstruction methods including artificial construction, oblique photogrammetry, laser scanning[

2], and multi-view stereo matching[

3,

4] represent objects by using explicit geometric models such as meshes[

5], point clouds[

6], voxels[

7] and depth[

8]. Despite the extensive application of these established methods in the industry, they still exhibit certain limitations[

9,

10,

11]. Recently, numerous neural implicit representation methods have emerged with the deep integration of neural networks and rendering[

12,

13,

14,

15]. Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) [

16], a leading technique, uses neural networks to compute spatial sampling points’ color and density. These are integrated along viewing rays to generate view pixel colors, achieving impressive photo-realistic view synthesis. However, NeRF has slow training and inference speed, mostly limited to small-scale scene and its 3D modeling quality still has room for improvement.

Introduced as an advancement on NeRF, 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) [

17] starts with Structure from Motion (SFM) to calculate the input image’s camera pose, forming a sparse point cloud. This cloud initializes a 3D Gaussian cloud, projected onto the image plane via EWA, then rasterized with alpha-blending. The result is a point cloud file containing all rendering information, representing the reconstructed scene. 3DGS outperforms NeRF in rendering speed and quality, and its storage format allows easy integration with existing explicit models like meshes and point clouds[

17,

18]. But it is a memory-intensive 3D modeling method. For large-scale 3D scene reconstruction, conventional GPU fall short in computational resources, failing to complete the task.

To achieve the research objective of efficiently reconstructing large-scale photorealistic geographic scenes, this study comprehensively analyzes the 3D scene modeling effects of NeRF and 3DGS. To mitigate the high memory demands of large scene 3D reconstruction on GPU and enhance the visualization quality, this method introduces two innovations. Firstly, based on the distribution of the input sparse point cloud, Z-score and percentile-based filter is employed to cleanse the point cloud, thereby eliminating isolated points and minimizing artifacts. Secondly, considering the 3D spatial distribution characteristic of the point cloud, the entire scene is segmented into uniform grids to mitigate the occurrence of excessively small or large segments, ensuring smooth large-scale reconstruction on normal GPU.

2. Related Work

2.1.3. D Modeling Using NeRF

Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) was first introduced in 2020[

16]. This technique enables the photo-realistic visualization of 3D scenes through neural implicit stereo representation, significantly surpassing traditional methods in terms of fidelity and detail. Consequently, it has garnered extensive attention and experienced rapid development[

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Current research hotspots can be categorized into four main areas[

30]: enhancing the robustness of source data, enabling dynamic controllable scenes, improving rendering efficiency, and optimizing visual effects.

To boost source data robustness, NeRF--[

31]enhances image pose accuracy via camera parameter optimization. Deblur-NeRF[

32]uses denoising for high-quality view synthesis from poor images. Mirror-NeRF[

33] proposes a standardized multi- iew system to improve source data quality. In dynamic scenes, D-NeRF and H-NeRF[

34,

35] enable scene editing via parameterizing the NeRF scene. Clip-NeRF[

36] integrates generative models for autonomous scene generation. For rendering efficiency improvement, three main strategies are employed: incorporating explicit model data to enhance prior knowledge such as Point-NeRF and E-NeRF[

28,

37], optimizing sampling methods to cut down invalid sampling calculations such as DONERF[

38], and decomposing scenes to improve parallel computing rates such as KiloNeRF[

39]. Among these, Instant-NGP[

40] achieve the best. In effect optimization, geometric reasoning with MVS improves accuracy. MVSNeRF[

41] simulates some physical processes like refraction, transmission, and reflection, while NeRFReN and Ref-NeRF[

42,

43] enhance the regularization terms to fully optimize reconstructed optical properties.

2.2 3D Modeling Using 3DGS

3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), introduced in 2023 as an extension of NeRF[

17], utilizes an explicit representation and a highly parallelized workflow. It projects millions of 3D Gaussians into the imaging space for alpha-blending to achieve scene representation. Compared to NeRF, 3DGS significantly enhances computational and rendering efficiency while preserving the realism of the rendering effect. Research focuses on 3DGS can be categorized into three primary areas[

18,

44]: enhancing detail rendering, extending dynamic scene modeling and compressing Gaussian storage.

To enhance detail rendering, methods such as Multi-Scale 3DGS[

45], Deblur-GS[

46], and Mip-Splatting[

47] tackle issues like low-resolution aliasing, high-frequency artifacts, blurring in training images, and color inaccuracies of 3D objects. For dynamic scene modeling, Gaussian-Flow[

48] captures and reproduces temporal changes in a scene’s 3D structure and appearance. GaussianEditor and Gaussian Grouping[

49,

50,

51] integrate semantic segmentation to segment the complete scene and then edit it based on objects’ attributes such as geometry and surface. Animatable Gaussians[

52] uses explicit face models to better simulate complex facial expressions and details. To compress Gaussian storage, LightGaussian[

53] and HiFi4G[

54] focus on optimizing memory utilization during both the training and model storage phases. They have achieved significant compression rates while largely preserving visual quality.

2.3. Large-Scale 3D Scene Reconstruction

To support geographical applications, comprehensive scene reconstruction must be conducted over large areas with high efficiency. To date, there has been some progress in utilizing NeRF and 3DGS for the 3D modeling of geographical scenes.

On the NeRF side, several approaches have been proposed. S-NeRF[

55], Sat-NeRF[

27], and GC-NeRF[

56] leverage multi-view high-resolution satellite images with known poses to achieve view synthesis, thereby obtaining more accurate digital surface models (DSMs). However, these methods still exhibit significant limitations in model generalization and handling illumination effects. Mega-NeRF[

57] and Block-NeRF[

58] divide scenes into multiple sub-blocks for parallel training, fusing information from adjacent blocks to mitigate boundary effects and ensure continuity across the entire large-scale scene.

Several 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) methodologies, including VastGaussian[

59], Octree-GS[

60], DoGaussian[

61], and Hierarchy-GS[

62], have been developed. Due to the significant memory resources required for 3DGS training, large-scale scene modeling often needs extensive computational resources, incurring high costs. To tackle this, VastGaussian, DoGaussian, and Hierarchy-GS put forward their own scene segmentation strategies to enable large-scene reconstruction using normal-level GPU. However these methods mainly focus on the XY-plane, overlooking the Z-axis distribution and causing uneven segmentation. To boost rendering speed and ease rendering pressure, Octree-GS and Hierarchy-GS adopt the Level of Detail (LOD) concept as one another basic strategy. But Octree-GS has less smooth transitions between different scene levels than Hierarchy-GS due to its limited number of levels.

After analyzing these methods, this paper proposes a grid-based strategy based on point-cloud 3D distribution for more reasonable, universal, and uniform scene segementation. It also integrates Hierarchy-GS’s LOD hierarchical rendering strategy to ensure a more complete 3D scene representation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Architecture Overview

The general architecture proposed in this article, illustrated in the accompanying

Figure 1, integrates advancements from the original 3DGS and adopts the LOD strategy from Hierarchy-GS with our own segmentation strategy.

Acquiring low-altitude remote sensing images via UAV, this method uses Colmap for sparse reconstruction to get camera poses and scene sparse point cloud. It filters the point cloud with Z-Score and percentile-based approaches to remove redundant and stray points, yielding a cleaner point cloud. Then, the point cloud is mapped to the XY-plane, for grid initialization. The scene is segmented into preset grid numbers, and undergoes iterative grid partitioning and adjacent grid merging to obtain final scene blocks. Each block is trained, then based on Hierarchy - GS’s LOD strategy, a hierarchical structure tree is built to get the complete scene rendering result.

3.2. Point Cloud Filtering

The 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) and its derivative methods heavily rely on the distribution of sparse point clouds obtained through SfM during the progress of Gaussian cloud initialization. Each point location generates a randomly initialized Gaussian. However, SfM-generated point clouds inevitably contain outlier points that deviate from the main structure, which consequently lead to redundant Gaussians. These will negatively impact optimization efficiency and rendering quality during subsequent training. To address this issue, the paper proposes a straightforward filtering approach for effective point selection and elimination.

From the

Figure 2, several characteristics of the sparse point cloud reconstructed by SfM can be analyzed: ① Overall distribution is generally uniform, concentrated within a specific space, but there are still some stray points far from the main subject; ② From the histogram distribution along the

-axis and

-axis (red and green histograms), it shows a class of normal distribution centered at the origin, gradually decreasing towards both sides, with a few stray points at the extreme edges; ③ From the

-axis perspective, apart from being concentrated near the origin, there are also a few stray points far from the main subject, often concentrated in the negative region.

Therefore, this method employs two filtering approaches for the

-axis,

-axis, and

-axis directions. The point cloud data exhibits characteristics of a normal distribution along the

and

axes, hence the Z-Score method is used for filtering, following these steps, as shown in formula (1). The point cloud data is mapped separately onto the

-axis and

-axis, and filtered directionally. For each data point

in the point cloud, calculate the difference between it and the mean value

of the dataset, then divide this difference by the standard deviation

of the dataset. This yields the Z-score

, representing the position of the data point relative to the center of the data distribution. Z-scores with absolute values exceeding 2 are considered outliers, as they deviate from the mean by more than 2 standard deviations. According to the normal distribution, this approach retains 95.45% of the data points.

The threshold value is set to 2 instead of 3 due to the characteristics of the 3DGS class method in reconstructing scene edges. Points at the scene edges play a relatively minor role during training, and the reconstructed edge areas lack ground truth for comparison, resulting in poorer performance in these regions, as shown in

Figure 3 with the Polytech edge reconstruction. Therefore, for the

-plane, the range can be appropriately reduced to concentrate the data more effectively and eliminate stray points more thoroughly.

Regarding the

-axis,, there is no need for extensive consideration. It can be observed that the majority of points in the point cloud are concentrated near the origin, with only a very small number of points being extremely distant from the center of aggregation. Therefore, a simpler percentile filtering method can be employed to remove these outlier points, as shown in Equation (2).

After mapping all point cloud data to the z-axis, sort them by size, and then select points between the 2.5th percentile and the 99th percentile. The final filtering result is shown in

Figure 4.

3.3. Grid-Based Scene Segmentation

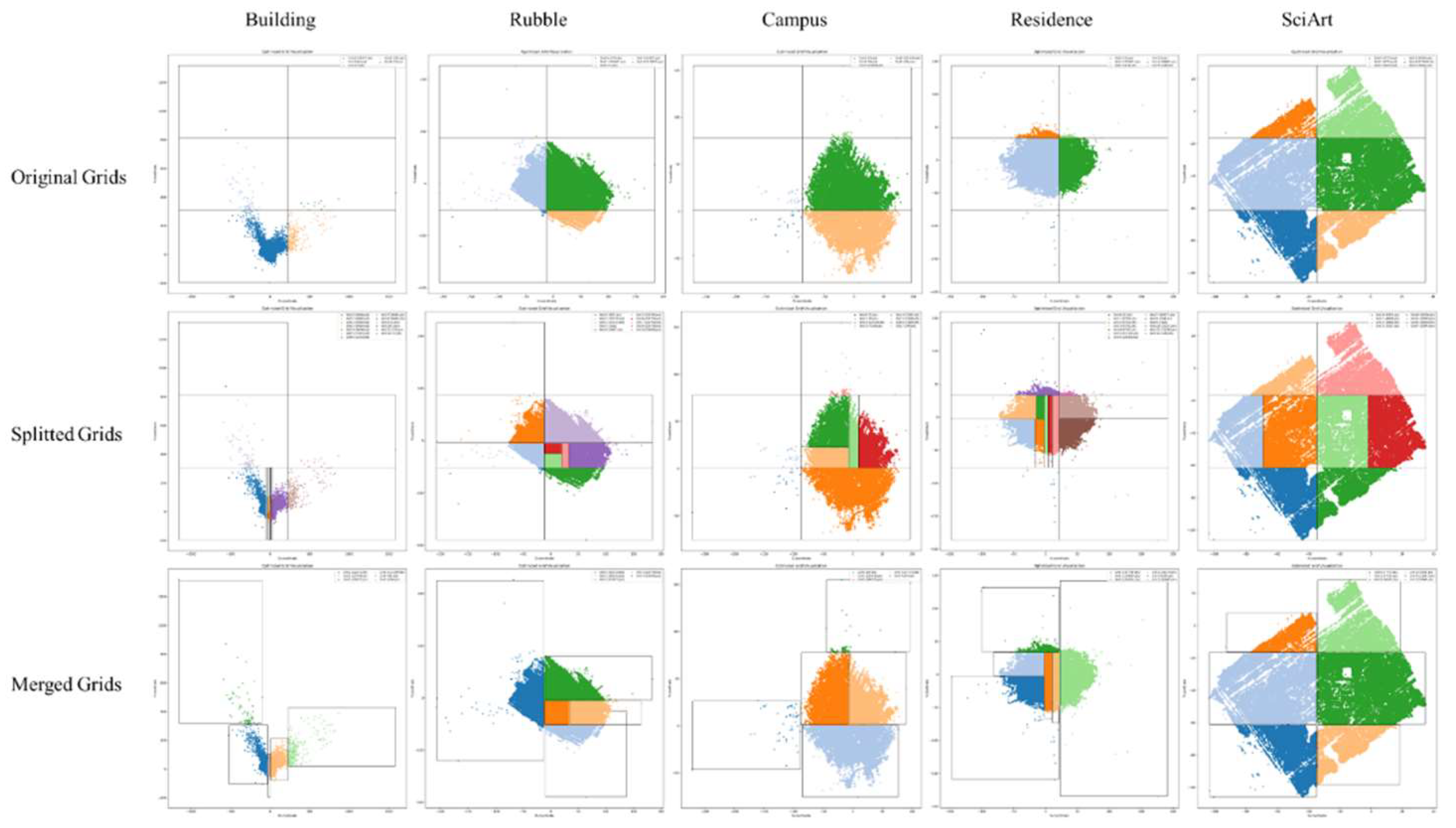

3.3.1. Create Initial Grid

The first step is to establish the initial grid by constructing a regular grid area according to the pre-specified number of blocks (

and

which is set at 2 and 3 by default) using the entire spatial range of the point set, with an optional overlap ratio. The method begins by projecting the 3D point cloud onto the

-plane to form a 2D point set

. The maximum and minimum values of the point set

in the

and

directions are determined to define the extent of the grid. Based on the preset number of blocks and the overall range, this method then determine the width

and height

of each subgrid. Given the overlap ratio

between blocks, the horizontal and vertical overlap distances

and

are computed. Following this, the lower-left corner coordinates (

) and upper-right corner coordinates (

) of each sub-grid

are calculated to define the grid boundaries. Finally, the number of 3D points within each block is counted based on the block’s boundaries. Through projection, the point set not only accurately reflects the distribution on the

-plane but also considers the distribution characteristics along the

-axis thereby completing the initialization of the point cloud grid.

Figure 5.

Point distribution of original grids.

Figure 5.

Point distribution of original grids.

Table 1 presents the grid initialization results for five datasets, revealing significant uneven distributions. On SciArt, the point count difference is 3.08 times; on Building, it is 28.9 times; on CAMPUS, 6.88 times; on RESIDENCE, 5.17 times; and on Rubble, 9.78 times. These large disparities lead to poor performance of 3DGS-class methods in sparse areas. To address the distribution differences and fully utilize all valid data, iterative partitioning and block merging were performed on the grid, resulting in more uniform scene point-cloud segmentation.

3.3.2. Grid Partitioning

The aforementioned process generated several sub-grids of equal size; however, due to the highly uneven distribution of point clouds, the number of points contained in each sub-grid varies significantly. If the point cloud distribution were uniform, the ideal scenario would be that the number of points in each sub-grid would differ only slightly. Given a total of points and sub-grid blocks, each grid should contain approximately points. This segmentation method is proposed based on this concept, with specific implementation details as follows.

If the number of points

in the current grid

exceeds the specified threshold

, it is necessary to partition this grid into two sub-grids, ensuring that the resulting sub-grids remain rectangular and have approximately equal numbers of points. A rectangle can be divided into two rectangles in two ways: along the

-axis or along the

-axis. Therefore, the first step is to choose the division direction. Calculate the variance of the points within the grid along the

and

directions, respectively, and select the direction with the larger variance for the division. Then, sort all coordinate values along the chosen axis and select the median value as the division position. Based on the division direction and position, divide the grid and construct the sub-grids. Repeat this process for each grid, including the newly divided grids, until the number of points in each grid meets the requirement or the maximum iteration count

is reached.

It is noteworthy that grid partitioning aims to alleviate the computational resource requirements for subsequent training processes while ensuring the final fused scene effect. To avoid point cloud distribution being too dense in certain areas, which may lead to grid partitioning failure and significant differences in the area of two sub-grids, or even the occurrence of extremely small sub-grids, it is necessary to make judgments during the partition process to avoid such issues. This method determines that if the difference in the number of points included in the sub-grids during the partitioning of one grid into two exceeds

, the partitioning process will be halted, and the original grid will remain unchanged, where

is set to 0.7. The results after partitioning are shown in

Figure 6, and the distribution of points within each sub-block has become relatively uniform.

3.3.3. Grid Merging

Although uniform point distribution grids were obtained through grid partitioning, each grid contains fewer points and has a smaller area, resulting in the selection of only a limited number of cameras in subsequent processes. This leads to insufficient acquisition of camera pose data, which significantly affects the modeling performance of 3DGS methods. Additionally, excessive partition increases training time substantially, indirectly raising the cost of scene modeling. Therefore, this method incorporates an additional grid merging module to consolidate overly fragmented partition grids, ultimately yielding uniformly distributed sub-grids with an appropriate number of segments.

If the number of points in a grid

is less than

, attempt to merge it with adjacent grids. Let the two grids to be merged be

and

, and the merged grid be

, with the merged point set being

. If

, then perform the merge operation; otherwise, keep the original grid unchanged. Here,

. After merging, each grid undergoes a certain degree of contraction to more tightly enclose its internal points, with a contraction rate of 99%, resulting in the final merged outcome as shown in

Table 2.

After undergoing the partitioning and merging steps, the distribution of sub-grid points for the five scenarios has significantly improved. Even for the scenario with the largest difference, Campus, the ratio between the maximum and minimum values is only 3.77 times, and the standard deviation is within a reasonable range relative to the mean. The final result is shown in

Figure 7.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

This paper uses PSNR, LPIPS, and SSIM to evaluate reconstruction results and compare with other methods. PSNR measures pixel-based image quality with higher values indicating better quality. LPIPS, using deep learning, computes feature-space distance, where lower values mean better perceptual quality. SSIM assesses structural similarity, with higher values also signifying superior quality.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Data

4.1.3. Mill19

The Mill 19 dataset, created by Carnegie Mellon University, is a large-scale scene dataset aiming to boost NeRF and 3DGS development in computer vision. The Rubble and Building data from this dataset are chosen for experiments. The Building scene consists of 1920 images, and the Rubble scene has 1657 images, both with a resolution of 4608×3456.

4.1.3. Urban Scene 3D

The UrbanScene3D dataset, developed by Shenzhen University’s Visual Computing Research Centre, promotes urban-scene awareness and reconstruction research. It contains over 128,000 images with a resolution of 5472×3648, covering 16 scenes, including real urban areas and 136 km² of synthetic urban zones. The Campus (2129 images), Residence (2582 images), and SciArt (3620 images) scenes are used in the experiments.

4.1.3. Self-Collected

The NJU and CMCC-NanjingIDC datasets are acquired via DJI Mavic 2 Pro with a resolution of 5280×3956. The NJU dataset contains images of Nanjing University’s Xianlin Campus, and the CMCC-NanjingIDC dataset includes images of China Mobile Yangtze River Delta (Nanjing) data center. In this experiment, 304 and 2520 images are used for scene reconstruction of these two datasets respectively to conduct ablation studies.

Table 3.

Basic attributes of datasets.

Table 3.

Basic attributes of datasets.

| |

Original

Resolution |

Sampling

Resolution |

Original

Images |

Colmap

Images |

| Rubble |

4608×3456 |

1152×864 |

1657 |

1657 |

| Building |

4608×3456 |

1152×864 |

1920 |

685 |

| Campus |

5472×3648 |

1368×912 |

2129 |

1290 |

| Residence |

5472×3648 |

1368×912 |

2582 |

2346 |

| SciArt |

5472×3648 |

1368×912 |

3620 |

668 |

| NJU |

5280×3956 |

1320×989 |

304 |

286 |

CMCC-

NanjingIDC |

5280×3956 |

1320×989 |

2520 |

2098 |

4.2. Preprocessing

To better compare with other methods, the paper preprocesses data in the same way. The images are downsampled to a quarter of their original resolution. During resampling, the paper uses a DOG method with a 3×3 convolution kernel and Lanczos interpolation to preserve image details.

4.3. Training Details

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, comparative experiments are conducted against NeRF-like and 3DGS-like approaches. For NeRF-like methods, nerfacto-big and Instant-NGP are reproduced using nerfstudio, each set to 100,000 iterations. For 3DGS-like methods, the original 3DGS, Octree-GS, and Hierarchy-GS are implemented, with 3DGS and Hierarchy-GS set to 30,000 iterations and Octree-GS to 40,000. The chunk size for Hierarchy-GS is uniformly set at 50.

For dataset preparation, training and test sets are selected by sampling one out of every ten images from those used in Colmap. Specifically, 90% of the images are used for training, and 10% are reserved for testing. All models are trained on the same dataset processed by Colmap to ensure a fair comparison.

The computational setup for this method consists of a single standard 4090 GPU with 24G memory.

4.4. Comparison with SOTA Implicit Methods

To demonstrate the method’s feasibility, two types of comparisons are made. One compares the reconstruction of individual blocks with 3DGS, Octree-GS, and Hierarchy-GS, demonstrating the method’s competitiveness in individual block reconstruction. The other compares the modeling of complete scenes with nerfacto-big, Instant-NGP, and Hierarchy-GS, highlighting its advantages in full-scene reconstruction. Note that VastGaussian and DoGaussian aren’t compared due to the lack of official code, and Mega-NeRF is excluded for its excessive camera - pose requirements.

4.4.1. Single Block

Table 4 presents the single-block results on the Mill 19 and Urban Scene datasets. Notably, 3DGS and Octree-GS use blocks from this paper’s partitioning method, whereas Hierarchy-GS uses its own, with the most similar selected for comparison. Our method performs well across all five datasets. It achieves the best PSNR, LPIPS, and SSIM results on Building and SciArt, with minimal gaps in some cases. On Rubble, Campus, and Residence, though slightly underperforming compared to original 3DGS, it surpasses other large - scene modeling methods. Due to VRAM overflow, 3DGS reconstruction of the SciArt block scene stops at 8,900 iterations, so the table shows results at 7,000 iterations.

As shown in

Table 5, this method achieves good single - block modeling while requiring less machine performance. 3DGS and Octree-GS can consume up to nearly 24GB of VRAM for individual scenes, the limit for a standard 4090 GPU. In contrast, both Hierarchy-GS and our method significantly reduce VRAM usage, with ours being slightly lower than Hierarchy-GS.

Figure 8 visually compares the results. In Building, 3DGS and our method better restore texture details. In Rubble, Hierarchy-GS fails to model shaded vehicles. In Campus, Octree-GS darkens shaded trees and loses details. In Residence, results are mostly consistent with minor differences on the road. In SciArt, Hierarchy-GS produces a more refined result.

4.4.2. Full Scene

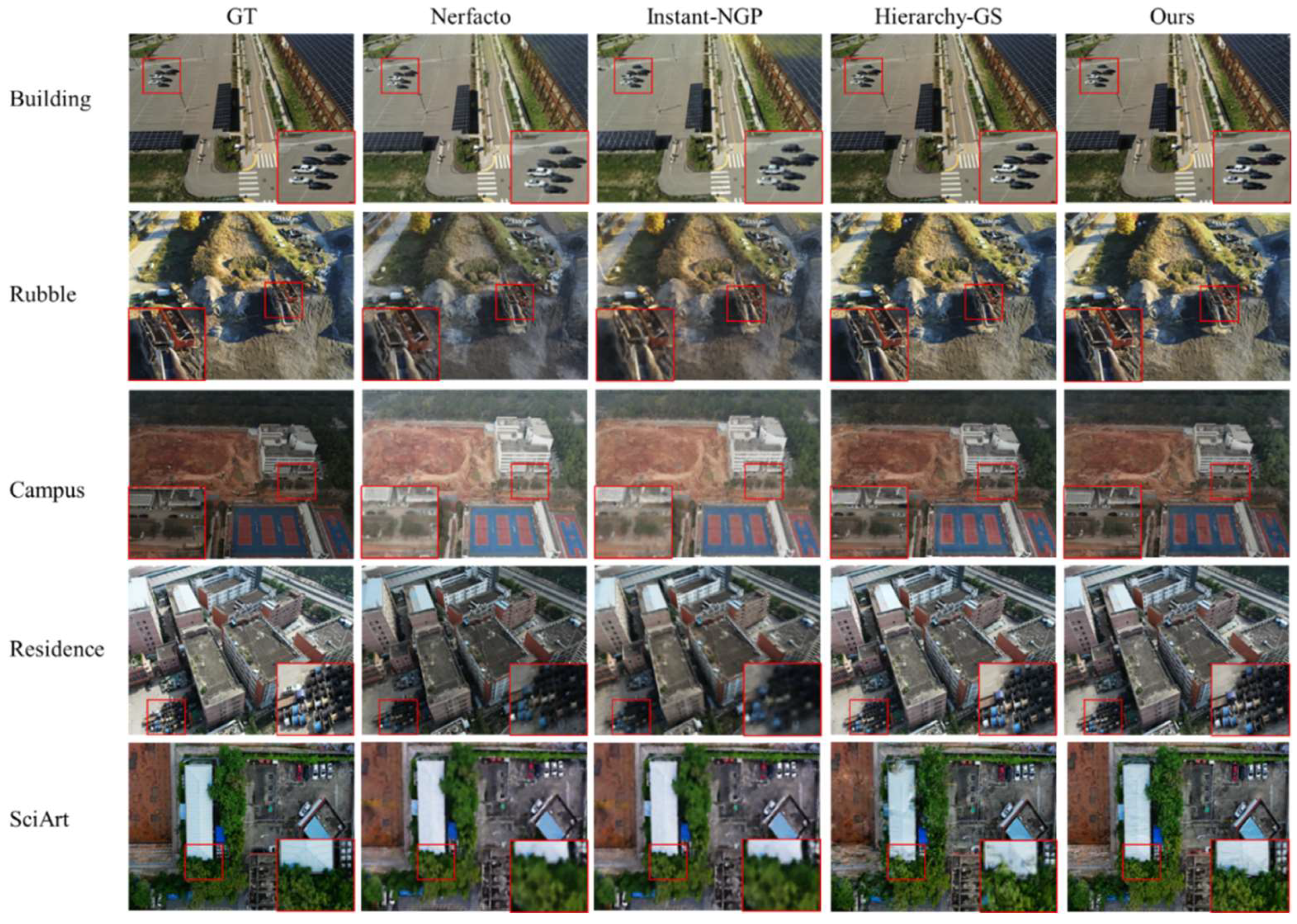

Table 6 compares the full - scene performance of our method, Nerfacto-big, Instant-NGP, and Hierarchy-GS. Our method generally achieves higher PSNR, SSIM and lower LPIPS scores, except possibly in the SciArt scene. The method achieves an average 2.45%, 6.41% and 3.77% improvement in PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS. During experiments, Nerfacto-big uses 15 - 23GB of VRAM, Instant - NGP 14 - 18GB, and both Hierarchy-GS and our method 10 - 14GB.

As shown in

Figure 9, Nerfacto and Instant-NGP have less ideal reconstruction effects. Hierarchy-GS also underperforms in some details. In the Campus scene, it produces artifacts in the vehicles and trees marked by the red box. In the Residence scene, it lacks details in the roller. In the SciArt scene, it loses the stripes on the blue roof and the surrounding green vegetation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Importance of Filter

The initial distribution of the input point cloud impacts the modeling results and our proposed region segmentation method. As our approach is point-distribution-based, noise points can greatly affect the segmentation.

Figure 10 shows the segmentation results without filtering. Stray points cause grid-range misjudgment in grid initialization, leading to extremely uneven segmentation. This affects the iterative partitioning and final grid merging, easily creating large-area blocks with few points and small-area blocks with many points. Such unreasonable partitioning is detrimental to subsequent scene modeling. The impact on Building, Rubble, Campus, and Residence is significant, while SciArt is less affected. This is because SciArt has fewer stray points, which are also close to the main body.

5.2. Ablation Analysis

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed point cloud filter and scene segementation, ablation experiments are conducted on the self-collected NJU and CMCC-NanjingIDC datasets, and the public Rubble dataset. As shown in

Table 7, on the NJU dataset, the complete scene achieves slightly higher PSNR and SSIM than removing only the segementation or filtering module, with similar LPIPS. On the CMCC-NanjingIDC and Rubble datasets, all three indicators show more significant improvements, especially on the Rubble dataset. Here, PSNR increases by 0.55 (2.05%) and 1.04 (3.95%) compared to removing partitioning or filtering; LPIPS decreases by 0.026 (10.5%) and 0.033 (12.9%); SSIM rises by 0.015 (1.81%) and 0.021 (2.55%). Notably, removing only the filtering module generally has a larger impact across all datasets. Without filtering, redundant points affect both scene reconstruction and segementation, causing double negative effects on the final results.

5.3. Shortcoming

Although this method has realized large-scale scene reconstruction and has certain advantages over other methods in both individual blocks and complete scenes, it still has its own drawbacks. To cut down GPU usage, this method trades time for space. Each scene block takes nearly an hour to train. Thus, the reconstruction time for a complete scene is directly proportional to the number of blocks, negatively affecting overall efficiency.

6. Conclusions

Low-altitude remote sensing images is one crucial data source for large-scale urban 3D reconstruction. This study introduces a novel approach to large-scale 3D scene reconstruction leveraging 3DGS. Initially, the sparse point cloud derived from indirect input data undergoes filtering to enhance data robustness, thereby can improve the final reconstruction quality. The filtered point cloud also provides a more reliable foundation for scene segmentation, minimizing erroneous segmentations. During scene segmentation, the 3D distribution characteristics of the point cloud are fully exploited to develop a grid-based three-step strategy, ensuring high generalizability and rationality. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, experiments are conducted on five public datasets and two self-collected datasets. The results demonstrate that the method yields satisfactory outcomes. Finally, the limitations of this method and potential directions for improvement are discussed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.G., and Z.W.; formal analysis, Y.G.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, Y.G.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G., S.Z, J.H, and W.W.; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, Y.G., W.Z, S.W. and Y.Z.; project administration, J.S., Z.W.; funding acquisition, J.S., Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant number 42471458, and also by Nanjing University- China Mobile Communications Group Co., Ltd. Joint Institute.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the results of this study are available from the respective authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the GraphDeco-INRIA team for their inspiring work, which provided a valuable foundation for our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Duan, H.; Ding, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yuan, J. Scene Reconstruction Techniques for Autonomous Driving: A Review of 3D Gaussian Splatting. Artif Intell Rev 2024, 58, 30. [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Tao, W.; Zhao, H. High-Precision 3D Reconstruction for Small-to-Medium-Sized Objects Utilizing Line-Structured Light Scanning: A Review. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4457. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Kang, W.; Xie, X. CostFormer:Cost Transformer for Cost Aggregation in Multi-View Stereo 2023.

- Ding, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. TransMVSNet: Global Context-Aware Multi-View Stereo Network with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 8575–8584.

- Kato, H.; Ushiku, Y.; Harada, T. Neural 3D Mesh Renderer. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: Salt Lake City, UT, June 2018; pp. 3907–3916.

- Berger, M.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Seversky, L.M.; Alliez, P.; Guennebaud, G.; Levine, J.A.; Sharf, A.; Silva, C.T. A Survey of Surface Reconstruction from Point Clouds. Computer Graphics Forum 2017, 36, 301–329. [CrossRef]

- Häne, C.; Tulsiani, S.; Malik, J. Hierarchical Surface Prediction for 3D Object Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV); October 2017; pp. 412–420.

- Izadi, S.; Kim, D.; Hilliges, O.; Molyneaux, D.; Newcombe, R.; Kohli, P.; Shotton, J.; Hodges, S.; Freeman, D.; Davison, A.; et al. KinectFusion: Real-Time 3D Reconstruction and Interaction Using a Moving Depth Camera. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology; ACM: Santa Barbara California USA, October 16 2011; pp. 559–568.

- Fuentes Reyes, M.; d’Angelo, P.; Fraundorfer, F. Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning-Based Stereo Matching and Multi-View Stereo for Urban DSM Generation. Remote Sensing 2024, 17, 1. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gan, V.J.L. Enhancing 3D Reconstruction of Textureless Indoor Scenes with IndoReal Multi-View Stereo (MVS). Automation in Construction 2024, 166, 105600. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yan, X.; Zheng, Y.; He, J.; Xu, L.; Qin, D. Multi-View Stereo Algorithms Based on Deep Learning: A Survey. Multimed Tools Appl 2024. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. DeepSDF: Learning Continuous Signed Distance Functions for Shape Representation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Long Beach, CA, USA, June 2019; pp. 165–174.

- Mescheder, L.; Oechsle, M.; Niemeyer, M.; Nowozin, S.; Geiger, A. Occupancy Networks: Learning 3D Reconstruction in Function Space. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Long Beach, CA, USA, June 2019; pp. 4455–4465.

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Learning Implicit Fields for Generative Shape Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Long Beach, CA, USA, June 2019; pp. 5932–5941.

- Michalkiewicz, M.; Pontes, J.K.; Jack, D.; Baktashmotlagh, M.; Eriksson, A. Deep Level Sets: Implicit Surface Representations for 3D Shape Inference 2019.

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis. Commun. ACM 2022, 65, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkuehler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, W. A Survey on 3D Gaussian Splatting 2024.

- Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B.; Tancik, M.; Hedman, P.; Martin-Brualla, R.; Srinivasan, P.P. Mip-NeRF: A Multiscale Representation for Anti-Aliasing Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, October 2021; pp. 5835–5844.

- Cen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Fang, J.; Yang, C.; Shen, W.; Xie, L.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. Segment Anything in 3D with NeRFs 2023.

- Chen, Z.; Funkhouser, T.; Hedman, P.; Tagliasacchi, A. MobileNeRF: Exploiting the Polygon Rasterization Pipeline for Efficient Neural Field Rendering on Mobile Architectures.; 2023; pp. 16569–16578.

- Deng, C. NeRDi: Single-View NeRF Synthesis With Language-Guided Diffusion As General Image Priors.

- Garbin, S.J.; Kowalski, M.; Johnson, M.; Shotton, J.; Valentin, J. FastNeRF: High-Fidelity Neural Rendering at 200FPS. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, October 2021; pp. 14326–14335.

- Hu, T.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, T.; Jia, J. EfficientNeRF Efficient Neural Radiance Fields.; 2022; pp. 12902–12911.

- Jia, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, C. Drone-NeRF: Efficient NeRF Based 3D Scene Reconstruction for Large-Scale Drone Survey. Image Vision Comput 2024, 143, 104920. [CrossRef]

- Johari, M.M.; Lepoittevin, Y.; Fleuret, F. GeoNeRF: Generalizing NeRF with Geometry Priors. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 18344–18347.

- Mari, R.; Facciolo, G.; Ehret, T. Sat-NeRF: Learning Multi-View Satellite Photogrammetry With Transient Objects and Shadow Modeling Using RPC Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 1310–1320.

- Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Philip, J.; Bi, S.; Shu, Z.; Sunkavalli, K.; Neumann, U. Point-NeRF: Point-Based Neural Radiance Fields.; 2022; pp. 5438–5448.

- Zhang, G.; Xue, C.; Zhang, R. SuperNeRF: High-Precision 3-D Reconstruction for Large-Scale Scenes. Ieee T Geosci Remote 2024, 62, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- 赵强; 佘江峰; 万奇峰 神经辐射场应用于大规模实景三维场景可视化研究进展评述. 遥感学报 2023, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Xie, W.; Chen, M.; Prisacariu, V.A. NeRF--: Neural Radiance Fields Without Known Camera Parameters 2022.

- Ma, L.; Li, X.; Liao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Sander, P.V. Deblur-NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields From Blurry Images.; 2022; pp. 12861–12870.

- Zeng, J.; Bao, C.; Chen, R.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, G.; Bao, H.; Cui, Z. Mirror-NeRF: Learning Neural Radiance Fields for Mirrors with Whitted-Style Ray Tracing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; ACM: Ottawa ON Canada, October 26 2023; pp. 4606–4615.

- Pumarola, A.; Corona, E.; Pons-Moll, G.; Moreno-Noguer, F. D-NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields for Dynamic Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Nashville, TN, USA, June 2021; pp. 10313–10322.

- Xu, H.; Alldieck, T.; Sminchisescu, C. H-NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields for Rendering and Temporal Reconstruction of Humans in Motion. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Vol. 34, pp. 14955–14966.

- Wang, C.; Chai, M.; He, M.; Chen, D.; Liao, J. CLIP-NeRF: Text-and-Image Driven Manipulation of Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 3825–3834.

- Low, W.F.; Lee, G.H. Robust E-NeRF: NeRF from Sparse & Noisy Events under Non-Uniform Motion. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Paris, France, October 1 2023; pp. 18289–18300.

- Neff, T.; Stadlbauer, P.; Parger, M.; Kurz, A.; Mueller, J.H.; Chaitanya, C.R.A.; Kaplanyan, A.; Steinberger, M. DONeRF: Towards Real-Time Rendering of Compact Neural Radiance Fields Using Depth Oracle Networks. Computer Graphics Forum 2021, 40, 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Reiser, C.; Peng, S.; Liao, Y.; Geiger, A. KiloNeRF: Speeding up Neural Radiance Fields with Thousands of Tiny MLPs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, October 2021; pp. 14315–14325.

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant Neural Graphics Primitives with a Multiresolution Hash Encoding. Acm T Graphic 2022, 41, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, F.; Yu, J.; Su, H. MVSNeRF: Fast Generalizable Radiance Field Reconstruction from Multi-View Stereo. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, October 2021; pp. 14104–14113.

- Verbin, D.; Hedman, P.; Mildenhall, B.; Zickler, T.; Barron, J.T.; Srinivasan, P.P. Ref-NeRF: Structured View-Dependent Appearance for Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); June 2022; pp. 5481–5490.

- Guo, Y.-C.; Kang, D.; Bao, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.-H. NeRFReN: Neural Radiance Fields with Reflections. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 18388–18397.

- Bao, Y.; Ding, T.; Huo, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Luo, J. 3D Gaussian Splatting: Survey, Technologies, Challenges, and Opportunities 2024.

- Yan, Z.; Low, W.F.; Chen, Y.; Lee, G.H. Multi-Scale 3D Gaussian Splatting for Anti-Aliased Rendering. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 16 2024; pp. 20923–20931.

- Lee, B.; Lee, H.; Sun, X.; Ali, U.; Park, E. Deblurring 3D Gaussian Splatting 2024.

- Yu, Z.; Chen, A.; Huang, B.; Sattler, T.; Geiger, A. Mip-Splatting: Alias-Free 3D Gaussian Splatting.

- Lin, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, S.; Yao, Y. Gaussian-Flow: 4D Reconstruction with Dynamic 3D Gaussian Particle 2023.

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Lin, G. GaussianEditor: Swift and Controllable 3D Editing with Gaussian Splatting 2023.

- Fang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L.; Tian, Q. GaussianEditor: Editing 3D Gaussians Delicately with Text Instructions 2023.

- Ye, M.; Danelljan, M.; Yu, F.; Ke, L. Gaussian Grouping: Segment and Edit Anything in 3D Scenes 2023.

- Li, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Animatable Gaussians: Learning Pose-Dependent Gaussian Maps for High-Fidelity Human Avatar Modeling 2023.

- Fan, Z.; Wang, K.; Wen, K.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z. LightGaussian: Unbounded 3D Gaussian Compression with 15x Reduction and 200+ FPS 2023.

- Jiang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, P.; Su, Z.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, L. HiFi4G: High-Fidelity Human Performance Rendering via Compact Gaussian Splatting 2023.

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L. S-NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields for Street Views 2023.

- Wan, Q.; Guan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, X.; She, J. Constraining the Geometry of NeRFs for Accurate DSM Generation from Multi-View Satellite Images. IJGI 2024, 13, 243. [CrossRef]

- Turki, H.; Ramanan, D.; Satyanarayanan, M. Mega-NeRF: Scalable Construction of Large-Scale NeRFs for Virtual Fly- Throughs. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 12912–12921.

- Tancik, M.; Casser, V.; Yan, X.; Pradhan, S.; Mildenhall, B.P.; Srinivasan, P.; Barron, J.T.; Kretzschmar, H. Block-NeRF: Scalable Large Scene Neural View Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 8238–8248.

- Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, S.; Yan, Y.; et al. VastGaussian: Vast 3D Gaussians for Large Scene Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 16 2024; pp. 5166–5175.

- Ren, K.; Jiang, L.; Lu, T.; Yu, M.; Xu, L.; Ni, Z.; Dai, B. Octree-GS: Towards Consistent Real-Time Rendering with LOD-Structured 3D Gaussians 2024.

- Chen, Y.; Lee, G.H. DoGaussian: Distributed-Oriented Gaussian Splatting for Large-Scale 3D Reconstruction Via Gaussian Consensus 2024.

- Kerbl, B.; Meuleman, A.; Kopanas, G.; Wimmer, M.; Lanvin, A.; Drettakis, G. A Hierarchical 3D Gaussian Representation for Real-Time Rendering of Very Large Datasets. Acm T Graphic 2024, 43, 1–15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).