1. Introduction

Real-world data sources, such as news articles and social media posts, produce fast-changing content streams that require real-time analysis. To support such an analysis, information must be represented in structured formats, such as knowledge graphs (KGs) [

1], which rely on information extraction tasks, including entity recognition and relation extraction (RE) [

2]. However, models trained on stationary datasets struggle to identify new relation types as data distributions evolve. In practical streaming scenarios, systems must be continuously updated to detect newly emerging relations.

Figure 1 illustrates this incremental paradigm, commonly referred to as continual learning, in which a model learns new RE tasks over time and is evaluated on an expanding set of previously seen relations. Continual relation extraction (CRE) aims to address this challenge by incrementally identifying relations in dynamic environments.

Continual learning (CL), also known as lifelong or incremental learning, was first established in computer vision and later extended to natural language processing (NLP) tasks, such as RE [

3]. A central challenge in CL is

catastrophic forgetting, in which models lose their previously acquired knowledge when trained on new tasks. Existing CRE methods mitigating the catastrophic forgetting fall into three general categories: (i) architecture-based [

4,

5], (ii) memory replay–based [

6,

7], and (iii) regularization-based that constrain model updates [

4,

8,

9], as summarized in [

10]. Among these, memory replay has emerged as being particularly effective. Replay techniques, motivated by memory consolidation mechanisms in neuroscience [

11], typically use encoder models such as BERT [

12] with modules that store representative samples from previously learned tasks [

10,

13,

14,

15].

Large language models (LLMs) have recently achieved a strong performance across NLP tasks, including entity recognition [

16], question answering [

17], and traditional RE [

18]. Zhou et al. [

19] suggest that pretrained models may offer advantages in CL. However, their analysis is limited to computer vision, and the behavior of LLMs in CRE remains unexplored. Although LLMs demonstrate competitive RE performance even without task-specific fine-tuning [

18], it is unclear how they retain or transfer knowledge under incremental training. This raises the following research question:

How do LLMs influence knowledge transfer, particularly backward transfer, in continual relation extraction? Backward knowledge transfer is a critical indicator of whether the performance of previously learned tasks improves or declines [

11].

To the best of our knowledge, this work presents the first reproducible benchmarks for LLMs in CRE and provides practical insights into model stability and hallucination behavior. We focus on the decoder-only and encoder-decoder models, which naturally support instruction-guided generative relation prediction. Encoder-only models, such as BERT, require an additional classification head and operate in a discriminative setting, which is incompatible with generative continual instruction tuning. To examine whether memory replay benefits LLMs, as hypothesized by [

19], we evaluate decoder-only and encoder-decoder models (see

Section 5.1.2) using K-means–based replay sampling on TACRED [

20] and FewRel [

21].

The main findings of this work are:

The contributions of this work are as follows:

To the best of our knowledge, we present the first systematic benchmarks evaluating LLM behavior, specifically, knowledge transfer and error patterns, in CRE across multiple architectures and datasets.

We analyze the effectiveness of memory replay in mitigating forgetting and identify model-specific strengths and limitations.

We provide a comprehensive analysis of hallucinations, showing how LLMs generate undefined relations in CRE and discussing the implications for KG updates.

2. Related Work

CRE leverages three different techniques to mitigate catastrophic forgetting: (i) memory replay–based, (ii) architecture-based, and (iii) regularization-based. In this section, we describe previous works on catastrophic forgetting in CRE.

Memory replay-based methods use a memory buffer to store a limited number of samples, which are replayed after training on each new task in the context of CL. Wang et al. [

24] proposed a sentence alignment model integrated with simple memory replay for incremental task relation extraction, in a setting referred to as CRE. Building on this, Cui et al. [

10] introduced a prototypical framework to refine the sample embeddings stored in memory for replay alongside relational prototypes. Chen et al. [

14] addressed the catastrophic forgetting problem by employing a consistency learning module designed to mitigate distributional shifts between old and new tasks in a few-shot CL. In addition, Zhang et al. [

13] proposed the Knowledge-Infused Prototypes framework, which leverages multi-head scaled dot-product attention to integrate features derived from relational knowledge-infused prompts, distinguishing it from other prototype-based methods. In contrast, Ye et al. [

15] addressed the dual challenges of limited labeled data and data imbalances. Their approach employed causal inference to select and store memory samples for an effective few-shot CRE.

Regarding architecture-based methods, Duan et al. [

5] proposed a zero-shot relation representation method that uses instance prompting and prototype rectification to simultaneously refine relation instances and prototype embeddings. Additionally, Chen et al. [

4] introduced a three-phase learning strategy—preliminary learning, memory retention, and memory consolidation—enhanced by linear connectivity to balance plasticity and stability.

Regarding regularization-based methods, Shen et al. [

9] proposed a dynamic feature regularization approach that dynamically computes the loss during training to mitigate catastrophic forgetting. Similarly, Jialan et al. [

25] employed an LSTM architecture with backward projection to preserve relation type classification space. In another work, Wu et al. [

26] integrated contrastive learning with a prompt-based BERT encoder to advance the few-shot CRE. In contrast to encoder-based methods, Van et al. [

8] proposed a gradient-based sequential multi-task approach for CRE that addresses multi-objective training in CL without retraining the encoder.

Leveraging advancements in LLMs, recent efforts have explored their use in CRE. Tirsogoiu et al. [

27] evaluated generative models for relation type identification by comparing the clustering performance across zero-, one-, and few-shot settings. Xiong et al. [

28] proposed contrastive rational learning to improve CL. Additionally, in the previous works, the most commonly used benchmark datasets for CRE are TACRED [

20] and FewRel [

21].

In this work, we evaluate pretrained LLMs for task-incremental relation extraction using memory replay and instruction tuning, assessing encoder-decoder and decoder-only LLMs (see

Section 5.1.2) on the TACRED and FewRel datasets. Despite the fact that [

27,

28] utilize LLMs in either few-shot settings or contrastive rationale learning, they do not employ any continual learning approach.

3. Preliminaries

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2 present a formal definition of CRE and an overview of the pretrained language models, respectively.

3.1. Continual Relation Extraction

CRE is a task that aims to continuously train a model on data containing new relation types, preserving the knowledge of previously learned relations [

6,

7], as illustrated in

Figure 1, and can be formalized inspired by the definitions in [

29] as follows:

A relation example is defined as a tuple:

where the

sentence is a textual sequence consisting of multiple tokens, the

head is the token(s) corresponding to the head entity, and the

tail is the token(s) corresponding to the tail entity. Furthermore,

where

contains the tuples for the relations

at time

, and

t indicates the time step.

3.2. Pretrained Language Models

Pretrained language models, typically trained to predict the next token autoregressively, are categorized into three transformer-based architectures: (i) encoder-only, (ii) decoder-only, and (iii) encoder-decoder [

30].

Encoder-only models use a bidirectional transformer encoder to learn the contextual representations. One prominent example is BERT [

12] and its variants.

Decoder-only models employ autoregressive masking. Notable examples include Llama [

23], Mistral [

31], and the GPT family [

32].

Encoder-decoder models, encompassing both conventional sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) and unified architectures, include Flan-T5 [

33] and BART [

34].

In this work, we employ decoder-only and encoder-decoder architectures rather than encoder-only models such as BERT, as our goal is to evaluate instruction-based generative relation prediction in incremental task learning settings with memory replay.

4. Methodology

In this section, we present an approach used in this work, which integrates incremental task instruction tuning of LLMs with a memory replay technique (see

Section 4.1).

LLMs are tuned on instruction datasets constructed from the original datasets using an instruction format, as described in

Section 4.2.

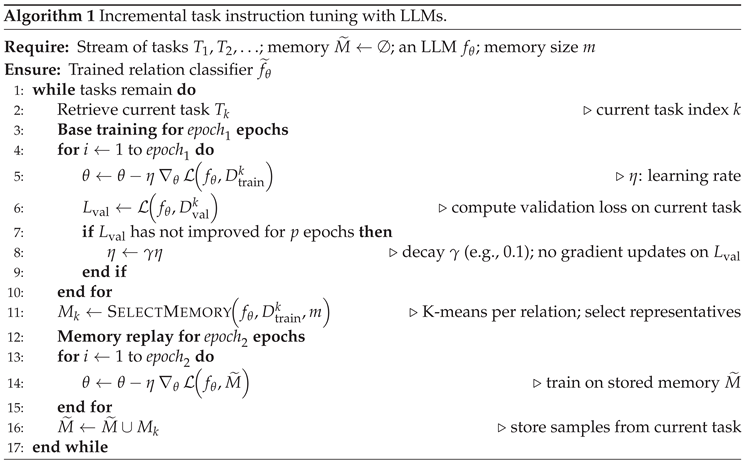

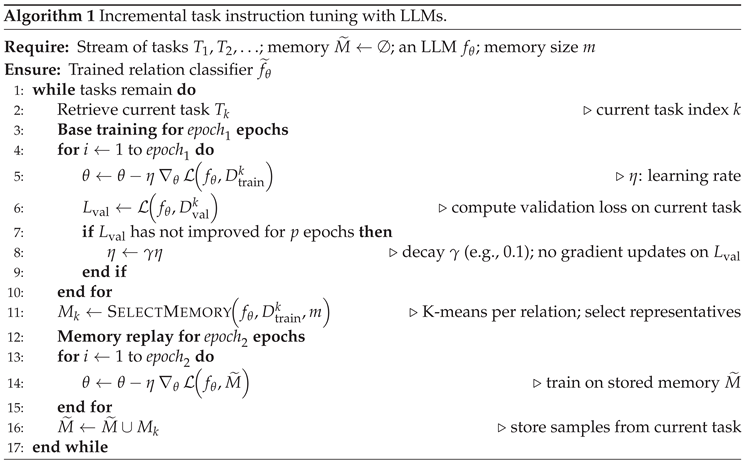

4.1. Continual Learning with LLMs

This section describes how LLMs are continuously instruction-tuned on a stream of tasks

and how forgetting is mitigated through memory replay. The process begins by tuning the model on the dataset for the initial task

. After training on each task, a validation dataset is used to optimize parameters, such as the learning rate, based on validation loss. This optimization is repeated throughout the training (Lines 4-10 in Algorithm 1). Unlike our approach, Cui et al. [

10] and Zhao et al. [

7] did not use any validation dataset during the optimization. Subsequently, a sampling strategy selects samples from the training set. Later, it is trained on samples from a memory buffer of previous tasks to preserve its performance on these tasks. Finally, the selected samples from the current task are stored in the memory buffer. The model is then instruction-tuned for each subsequent task. This continuous tuning process follows the steps outlined in Algorithm 1.

4.1.1. Memory Sample Selection

Memory replay [

7,

10] is one of the most effective strategies for mitigating catastrophic forgetting during continual learning. Furthermore, sampling strategies play a crucial role in memory replay. Uncertainty-based methods select the most complex samples by computing their uncertainty scores during incremental learning [

35]. However, replaying these complex samples during model training can result in overfitting. In contrast, diversity-based approaches such as K-means select representative samples [

36]. Although a model that relies solely on diversity-based sampling may miss complex samples, this strategy generally achieves better memory efficiency and general-purpose instruction capabilities. Moreover, because LLMs depend heavily on sample diversity for robust performance, the diversity-based approaches are particularly well-suited for LLM-focused memory replay.

K-means is a widely used method for selecting samples [

7,

10] and identifies the most representative samples from the cluster centroids. We also apply K-means to choose samples from the training data Algorithm 1. To construct the clusters, we utilize the concatenation of sentence, head, and tail vector representations in an instruction format (see further details in

Section 4.2). This process uses token-level contextual representations from either the encoder or decoder of the trained model, depending on the architecture of the LLM. Specifically, decoder-side vector representations are obtained from the decoder’s last hidden states. In contrast, encoder embeddings are used in encoder-decoder models. After receiving the token-level contextual representations, mean pooling and (2D) dimensionality conversion are applied before clustering them per relation type with K-means.

4.1.2. Incremental Instruction Tuning Algorithm

Algorithm 1 processes a stream of tasks and memory samples alongside the LLM . For each incoming task, is incrementally trained on its training dataset, , and evaluated on its validation dataset, (Lines 4–10). The memory buffer () starts empty and is progressively populated with samples selected from to support the replay after learning each new task.

After training on the current task (Lines 4–10), a set of memory samples, , is selected from using K-means clustering, given a fixed memory size m. This selection uses token-level contextual representations of , computed from either the encoder’s or decoder’s final hidden states of the trained model in Lines 4-10.

Before storing the new selected samples , which correspond to cluster centroids (Line 16), the memory samples from the previous task, , are replayed (Lines 13–15).

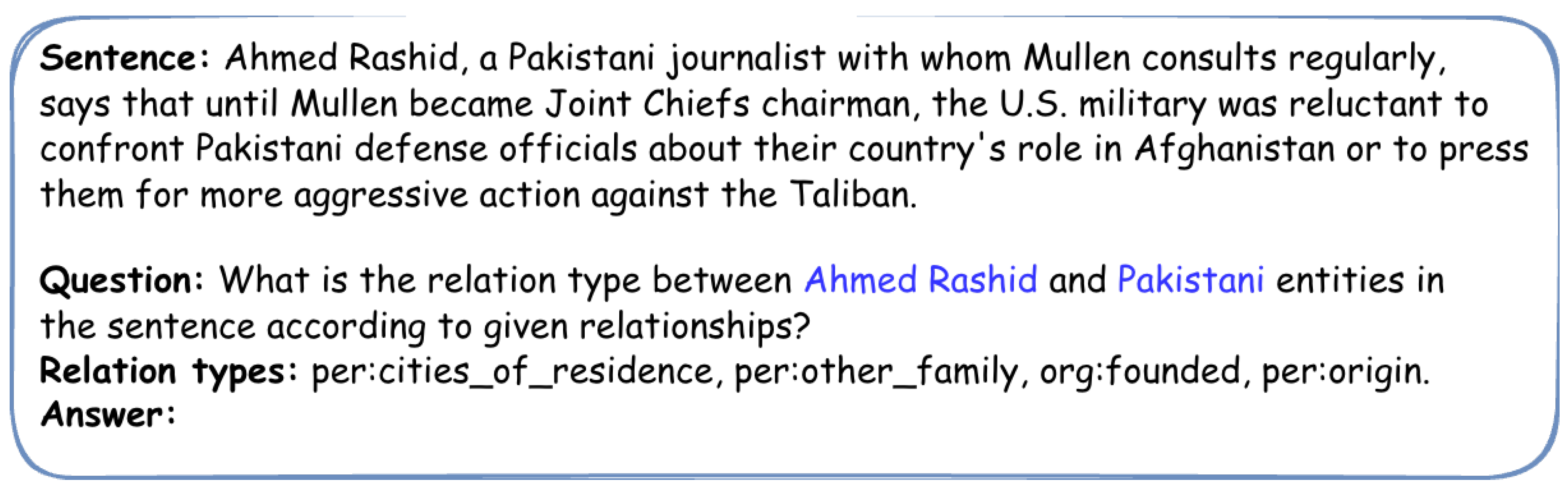

4.2. Instruction Format

We adopt the instruction shown in

Figure 2 from [

37] to tune incremental task instructions. This instruction highlights entity spans and employs conditional generation [

38]. Each task is limited to its predefined relation types in the instruction.

5. Evaluation

In this section, we first describe experimental settings in

Section 5.1. Then, we present and discuss our results in

Section 5.2 and the knowledge transfer analysis in

Section 5.3, based on the performance metrics introduced in

Section 5.1. We analyze false predictions in terms of predefined and undefined relation types in

Section 5.4.

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.1.1. Dataset

We evaluate the proposed approach on two benchmark datasets, TACRED [

20] and FewRel [

21], which are widely utilized for CRE assessment. All experiments are conducted across five independent runs, following prior works, and a memory sample size of 10 is employed to yield optimal performance [

7,

10,

13]. Independent sampling for each task is explicitly ensured, while the test sets remain fixed during incremental LLM instruction tuning.

TACRED. Since the TACRED dataset is highly imbalanced, we follow the experimental settings of prior works [

7,

10] and exclude no_relation labeled samples when constructing tasks. To mitigate data imbalance, for each of the remaining relation types (41), we randomly sample (using random seed 42) up to 320 sentences for training, 40 for validation, and 40 for testing within every task per relation type, consistent with [

7,

10]. The models are incrementally trained on TACRED using a 10-task setup, where each task contains

four relation types (further details are provided in Appendix A).

FewRel. We also adopt the experimental setup from previous works [

7,

10] for FewRel. This dataset is divided into 10 tasks, each containing

eight relation types (see Appendix A for further details). For each relation type, 420 sentences are randomly sampled for training, 140 for validation, and 140 for testing, using a random seed of 42.

5.1.2. Large Language Models

Five LLMs with distinct architectures are employed in this work. The instruction-tuned models in the experiments are Flan-T5 Base (250M)

2, Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2

3, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct

4, and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct

5, whereas Llama2-7B-hf

6 serves as a base (pretrained) model, meaning it was not tuned on any instruction dataset. By comparing the more recent instruction-tuned Llama variant with Llama2-7B-hf, we highlight the performance differences between them. In addition, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct support multilingual capabilities and long-context processing, whereas the other models do not. Encoder-only models, such as BERT, require an additional classification head to map representations to a predefined relation set; therefore, they do not support generative relation prediction, unlike generative LLMs, such as encoder-decoder and decoder-only models. In this work, inference is evaluated using greedy decoding (default) across all experiments.

5.1.3. Parameter Settings

The parameter configurations described in this section correspond to the best-performing models trained on an NVIDIA A100 GPU with 40 GB of memory. Note that less than 12 GB of GPU memory is sufficient to evaluate these models on the test datasets. During training, quantized low rank adaptation (QLoRA) [

39] is used to reduce GPU memory requirements while optimizing the targeted modules of the LLMs. To facilitate reproducibility, several models trained on FewRel are made publicly available on Hugging Face

7. The random seed is fixed at 42 across all experiments in PyTorch.

Model Parameters. The default configurations are used for the models, as indicated in their model cards given in

Section 5.1.2. The standard cross-entropy loss function is employed in all experiments conducted in this work.

Table A3 in Appendix C summarizes the training hyperparameters and trainers. The

AdamW optimizer is used with a

cosine_with_restart learning rate schedule and patience of one epoch. The dropout and weight decay are applied only to the LoRA adapter parameters, while the model weights remain frozen without additional regularization.

LoRA Parameters. LoRA [

40] is applied to 4-bit quantized pretrained LLMs (QLoRA [

39]), while optimizing the targeted modules of the LLMs. The LoRA rank parameters are selected based on the available GPU memory (40 GB) and the respective model sizes.

Table A4 in Appendix C summarizes the LoRA parameters.

Hardware. All models were trained using an NVIDIA A100 GPU with 40 GB of memory. The available disk storage is approximately 235.7 GB.

K-means Parameters. K-means selects the most representative samples from the centroids of the relation clusters based on the memory sample size (10) of each relation type. The random state is set to 0, and the parameter is set to `auto’.

5.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the proposed approach is evaluated based on the accuracy of the seen tasks during incremental task learning (ITL), as illustrated in

Figure 1. Additionally, we calculate the following continual learning metrics:

Whole Accuracy. is computed from the resulting model at the end of the ITL process for all test data across all tasks [

20].

Average Accuracy. is computed from the model trained on task

k, evaluated on all test sets of tasks seen up to stage

k of the ITL process [

20].

Backward Knowledge Transfer. quantifies the degree of forgetting in previously learned tasks after learning new tasks [

41]. This is an important indicator of whether backward knowledge transfer (BWT) occurs [

11]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work on CRE has reported this metric [

11]. BWT is calculated as follows:

where

represents the test accuracy of the

t-th task after sequential training for all

N tasks.

5.2. Results

We evaluate five well-known LLMs—Flan-T5 Base, Llama2-7B-hf, Llama3.1-8B-Instruct, Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct, and Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2—in incremental task learning (ITL) that utilizes memory replay for CRE. All seen accuracy metrics in

Table 1 represent the mean of five runs on two widely used benchmark datasets, TACRED and FewRel, for an optimal memory size of 10, as indicated in prior works [

7,

10,

13,

29].

The ITL-based tuned Flan-T5 Base demonstrates strong performance, achieving a mean seen task accuracy of 95.8% and 89.6% on TACRED and FewRel, respectively, as shown in

Table 1. The mean whole (

w) and average accuracy (

a) are 95.76% and 95.78% on TACRED, and 89.61% and 89.61% on FewRel, respectively, in

Table 2, indicating good performance on individual tasks with minimal forgetting on TACRED. In addition to Flan-T5 Base, we also evaluate Mistral-7B’s performance on these datasets. The mean seen task accuracies of the resulting models on TACRED and FewRel are 96.9% and 91.4%, respectively, at the end of ITL in

Table 1, with mean

w and

a of 96.89% and 96.76% for TACRED, and 94.93% and 94.93% for FewRel with this model in

Table 2, respectively. Likewise, Mistral-7B performs well on individual tasks with minimal catastrophic forgetting on TACRED when

w and

a metrics are considered. Similarly, Qwen2.5-7B is another instruction-tuned model with 7B parameters. Qwen2.5-7B achieves mean seen accuracies of 91.3% and 88.3% for TACRED and FewRel, respectively. The corresponding mean values of

w and

a are 91.27% and 91.38% on TACRED, and both are 88.25% for FewRel. These results are consistent with the performance trends observed for Flan-T5 Base and Mistral-7B.

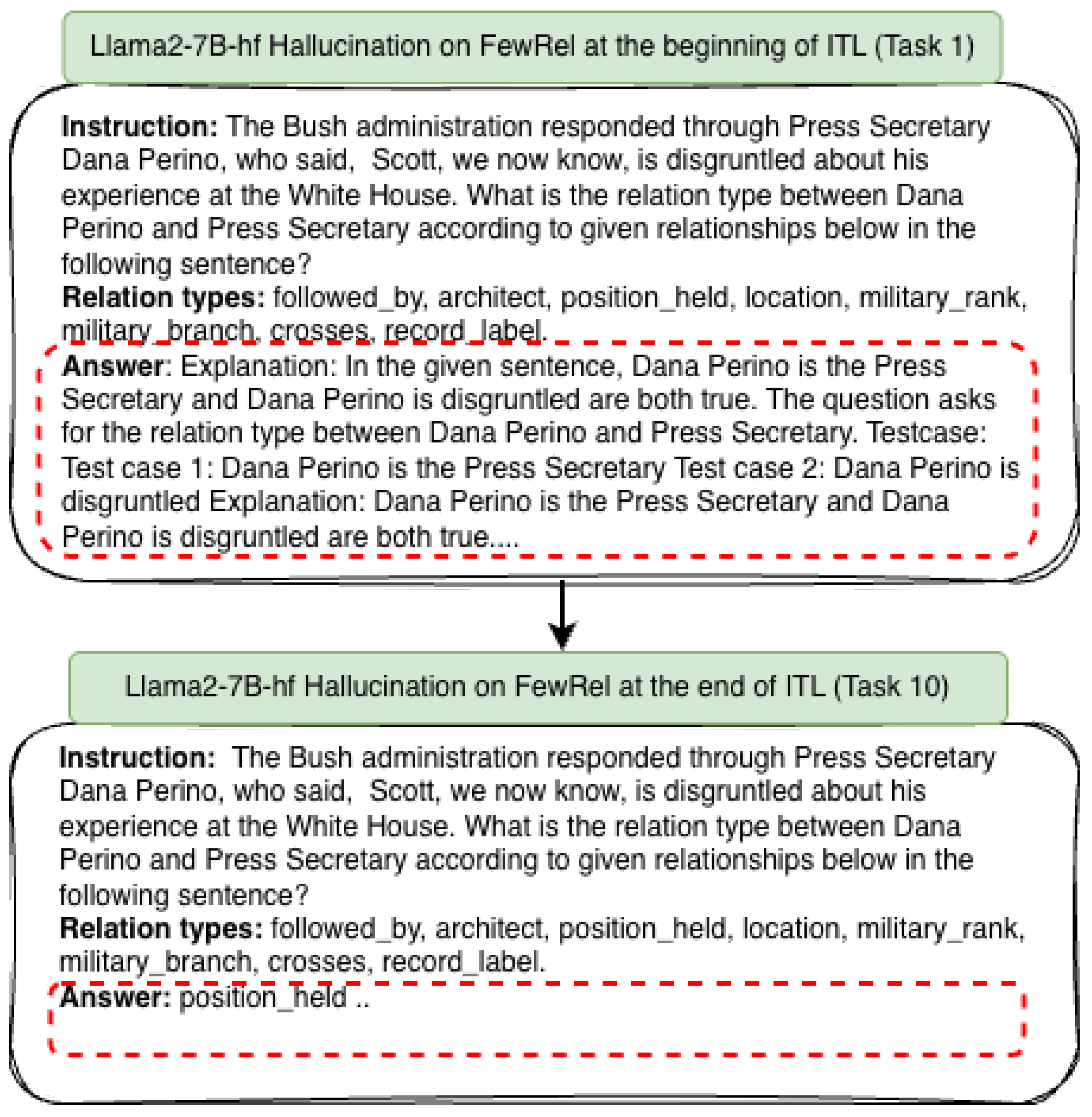

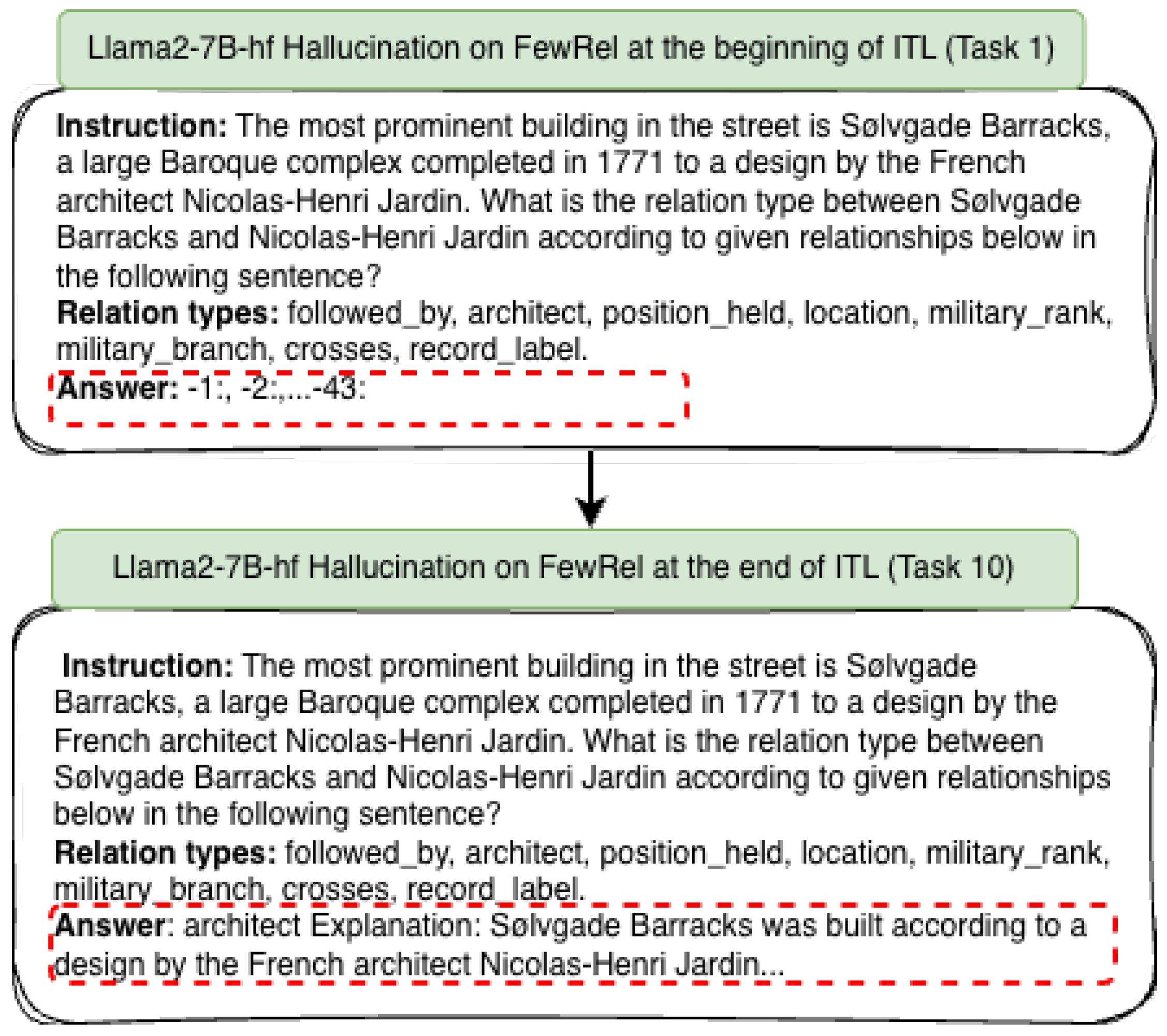

Furthermore, we evaluate Llama2-7B-hf in the ITL setting. In contrast to Flan-T5 Base, Mistral-7B, and Qwen2.5-7B, it does not achieve remarkable results on either dataset, with a mean seen task accuracy of 70.6% for TACRED and 71.3% for FewRel at the end of ITL (see

Table 1). Similar to the seen task accuracies, the mean

w and

a—71.17% and 70.86% on TACRED, and 71.29% for both metrics on FewRel—are lower than those of the other models in

Table 2, primarily due to hallucinating relation types by Llama2-7B-hf, for example, invalid relation predictions (e.g.,

per:affiliate and

per:columnist) which are not within the predefined relations, explanation without any relation prediction or repetition of the same tokens. The example in Appendix E demonstrates how Llama2 gradually adapts to the instruction format, making correct predictions for the same test samples from the initial training to the end of ITL. We further analyze these invalid predictions in

Section 5.4. We also conduct experiments with Llama-3.1-8B, an instruction-tuned model and a new version of Llama2-7B-hf. Llama-3.1-8B achieves mean seen accuracies of 78.7% and 81.1% on TACRED and FewRel datasets, respectively, indicating that it performs better on FewRel than on TACRED. The mean values of

w and

a are 78.74% and 79.20% on TACRED, and both are 81.13% for FewRel. Previously, most LLMs evaluated in

Table 1 demonstrated stronger performance on TACRED than on FewRel. Nevertheless, Llama-3.1-8B has a larger parameter size than the other models considered, which may contribute to these differences in performance.

Consequently, the instruction-tuned LLMs demonstrate superior performance compared to the base model, Llama2-7B-hf, across ITL. Even though Llama2’s performance has gradually increased from 57.7% and 15.4% to 70.6% and 71.3% on TACRED and FewRel, respectively, it still does not reach the levels of other models. This poor performance might be related to the fact that Llama2-7B-hf was not previously tuned on any instruction dataset. Furthermore, even though it seems that Mistral’s performance on both datasets is better than that of the other LLMs above, the permutation test results in

Table A7 in Appendix H state that there is no statistical difference between Flan-T5 Base and Mistral on TACRED. In contrast, Mistral outperforms Flan-T5 Base only at the end of ITL on FewRel, according to the statistical significance test results in

Table A8 in Appendix H.

5.3. Knowledge Transfer

In this section, we evaluate how LLMs transfer the knowledge learned on TACRED and FewRel across 10 tasks. [

11] states that continual learning not only focuses on preventing forgetting but also on adaptation and exploiting task similarity. Negative backward knowledge transfer (BWT) indicates forgetting or a decline in earlier task performances at the end of ITL. In contrast, positive BWT indicates successful knowledge transfer and improves earlier task performances when ITL is completed due to task similarity, with performance on previously learned tasks enhanced by ITL [

11]. The BWT metric measures the extent to which a model improves or degrades the previously learned task performance [

11].

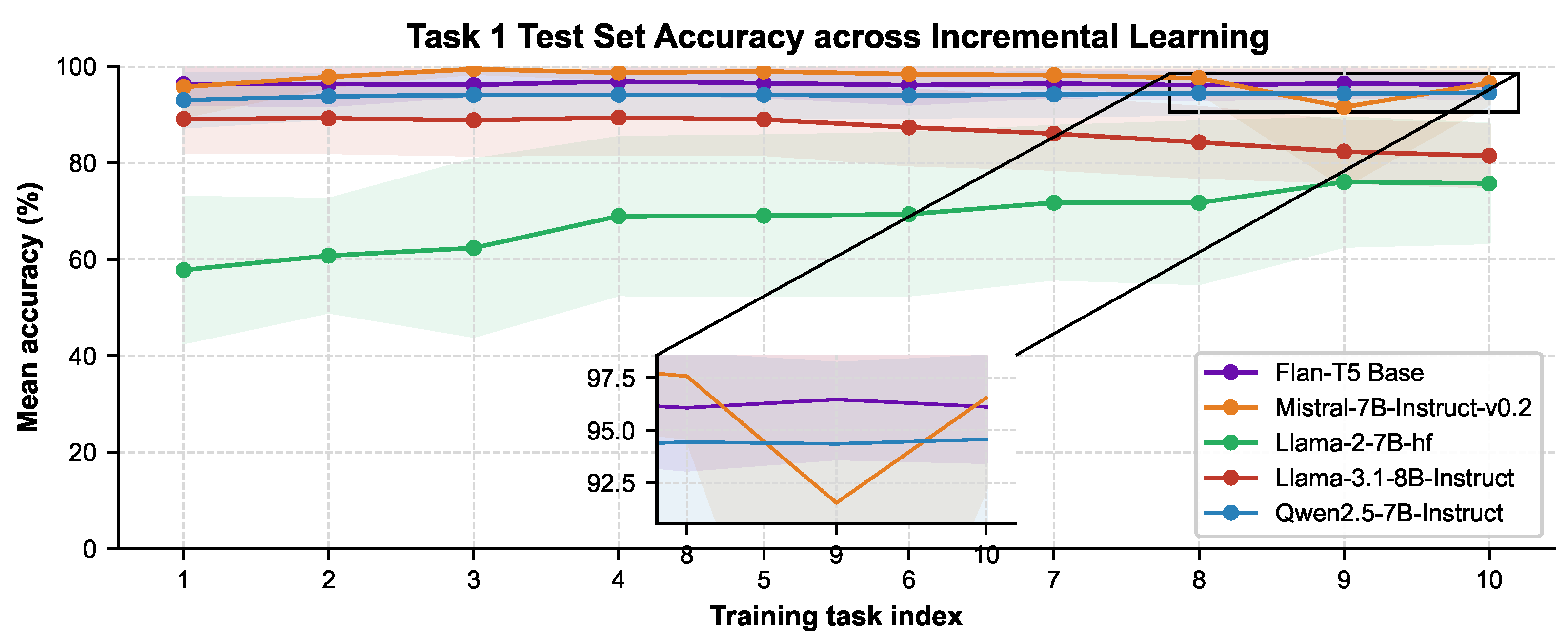

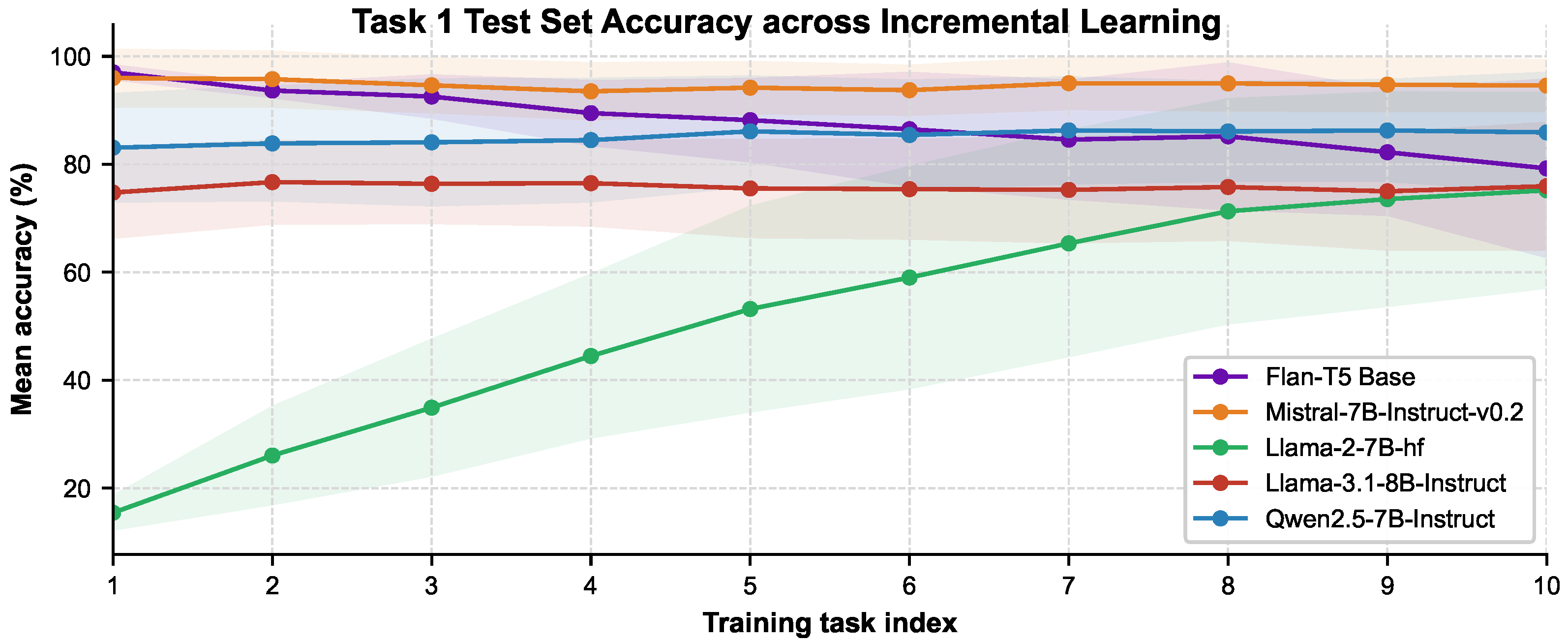

We illustrate how LLMs perform on an individual task, for example, Task 1 from TACRED and FewRel, across ITL in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Llama2-7B-hf exhibits positive BWT on both datasets, an uncommon but valuable trait, suggesting that the model improves performance on earlier tasks after learning a new one in

Table 3 because of the task similarities. Another reason for this performance improvement in Llama2-7B-hf is that it was not previously tuned on any instruction dataset. Thus, it gradually adapts to instructions with similar task contexts during incremental task learning, indicating that this positive BWT is a continued adaptation to the instruction format. Task context similarity is a primary factor in task similarity-based knowledge transfer [

11]. Likewise, Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct demonstrates a positive BWT, indicating that performance on earlier tasks improves throughout ITL, as shown in

Table 3. In contrast to Llama2-7B-hf and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct, Flan-T5 Base (250M) exhibits a BWT of -7.31% and -0.42% for FewRel and TACRED, respectively, indicating that it struggles with forgetting (

Figure A9 and

Figure A8 in Appendix G). Additionally, Mistral-7B demonstrates a BWT of 0.76% on TACRED, although it slightly forgets previously learned knowledge with a BWT of -0.58% on FewRel, as shown in

Table 3 (see further details in

Figure A10,

Figure A11 in Appendix G). The performance decline observed for Task 1 in

Figure 3 with Mistral stems from the model’s performance on Task 9, whose train and test sets include non-English terms (Appendix B). Similar to Flan-T5 Base and Mistral-7B, Llama-3.1-8B also exhibits negative BWT values of

and

on FewRel and TACRED, respectively.

Furthermore, from the model perspective, even though Llama2-7B-hf’s positive BWT mainly stems from being the base model before ITL, Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct also shows a positive BWT for both datasets. In addition,

Figure A9 and

Figure A8 in Appendix G demonstrate how Flan-T5’s performance declined per task on FewRel and TACRED across ITL as evidence of Flan-T5 Base’s BWTs. Task 1 test accuracy on FewRel with Flan-T5 Base in

Figure 4 has significantly dropped to 79.2% from 96.7. Despite Llama-3.1 having 8B parameters, it exhibits negative BWTs, whereas Qwen2.5 with 7B parameters demonstrates positive BWT on both datasets. Therefore, parameter size alone does not improve knowledge transfer; their architectures and training data may also impact their capabilities.

As a result, both Llama2-7B-hf and Qwen2.5 adapt well to instructions. They improve their performance on previously learned tasks, whereas Flan-T5 Base and Llama-3.1 tend to suffer from forgetting during ITL. In addition, Mistral demonstrates almost complete stability across ITL (Appendix G).

5.4. Error Analysis

In this section, we analyze false predictions in the results given in

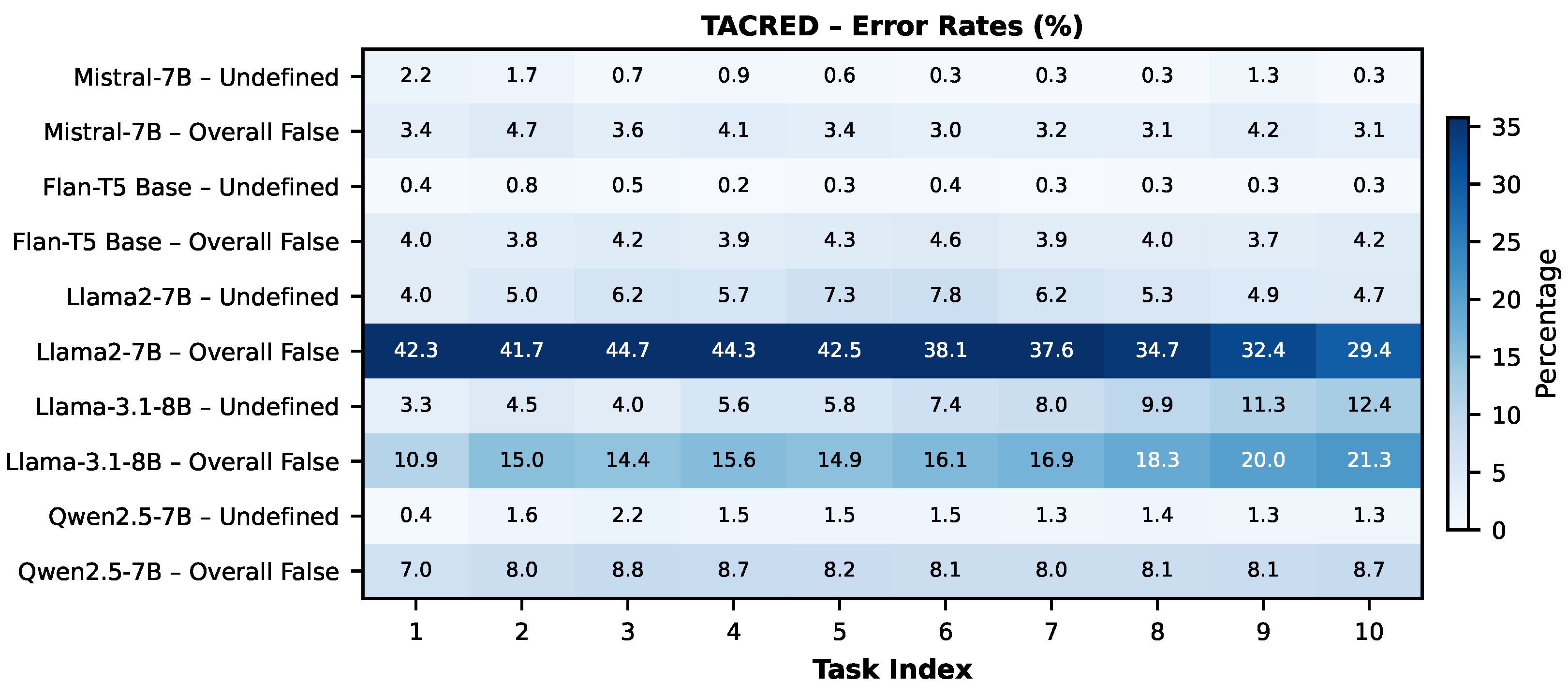

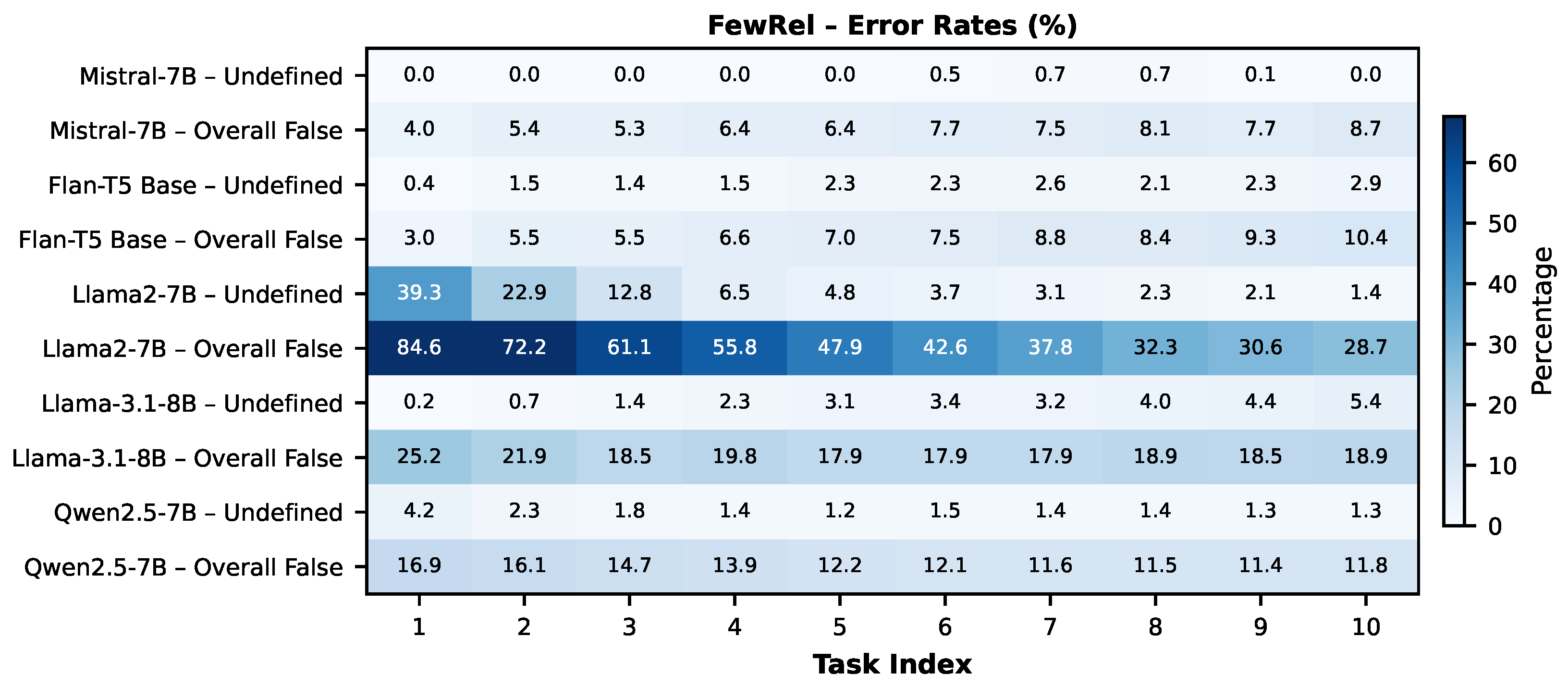

Table 1, which may correspond to either predefined relation types (e.g., valid but incorrect labels) or undefined relation types (e.g., hallucinations), owing to the next-token prediction mechanism employed by LLMs, which may lead to the generation of undefined relation types. We present the percentages of all false predictions with “Overall False” and the percentages of entirely new relation type predictions with “Undefined” in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

Regarding TACRED, Mistral-7B maintains a consistently low Undefined prediction rate (below 2.5%) and almost stable Overall False rates. Flan-T5 Base and Qwen2.5-7B similarly produce few Undefined predictions (mostly around 2%), though Qwen2.5-7B displays slightly higher Overall False rates. Llama2-7B-hf, lacking instruction tuning before ITL, shows the highest initial error rates, but these decrease substantially across ITL, indicating adaptation (see

Figure 7). In contrast, Llama-3.1-8B’s Overall False and Undefined rates steadily increase over the tasks.

With respect to FewRel, Mistral-7B produces almost no Undefined predictions and shows a gradual increase in Overall False rates. Flan-T5 Base similarly maintains low Undefined predictions (generally approximately 2%) but exhibits higher Overall False rates. Llama2-7B-hf again exhibits the highest initial error levels, although both Undefined and Overall False predictions decline substantially across ITL. By contrast, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct experiences increasing Undefined predictions over tasks despite a reduction in Overall False predictions, suggesting a growing tendency to generate undefined relation types. Qwen2.5-7B demonstrates consistent improvement, with both error types decreasing and showing only minor fluctuations across tasks.

Furthermore, we conduct a permutation test on the Task 1 test set using Llama2-7B-hf tuned on both Tasks 1 and 10 to determine whether the reduction in Undefined predictions is statistically significant, as shown in

Table A5 (Appendix D). The decrease is significant for FewRel (

p < 0.05) but not for TACRED. These results confirm that Undefined relation types for the Task 1 test set decrease significantly only for FewRel. We also categorize Undefined relation predictions into: (i) similar context, (ii) part of ground-truth, (iii) new relation type, and (iv) a fine-grained version of ground-truth in

Table A6 in Appendix E. Predictions in the first, for example, leader for head of department, and fourth, for instance, son for child, categories are semantically close to ground-truth and may be considered for potential practical applications, such as knowledge graph updates.

As a result, Llama2-7B-hf significantly struggles with Overall False predictions more than the others on both datasets, especially for earlier tasks, likely due to its lack of instruction tuning before ITL. Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct also produces many false predictions in earlier tasks. Mistral-7B consistently maintains low Undefined and Overall False rates across both datasets. Qwen2.5-7B’s trends depend on the dataset, showing improvements in FewRel and more fluctuating behavior in TACRED.

6. Ablation Study

In this section, we first examine how different memory sizes affect the performance of continual instruction tuning in

Section 6.1. Next, since we analyzed Llama2-7B-hf’s tendency to produce hallucinated predictions in

Section 5.4, we investigate whether alternative sampling strategies can mitigate test-time hallucinations in

Section 6.2.

6.1. Memory Size Experiments

We examine how varying memory sample sizes (e.g., 5, 10, and 15) affect incremental task tuning of LLMs on TACRED, as shown in Table 5. We choose these sample sizes rather than using a percentage of the training dataset, as prior work on TACRED [

7,

10,

13] did. We then conduct two-tailed permutation tests

8 with 10,000 iterations and a random seed of 42 to assess whether memory size significantly improves the final model performance at the end of ITL, as presented in

Table 4. P-values are computed based on the five accuracy scores obtained at the end of ITL after training the models on Task 10.

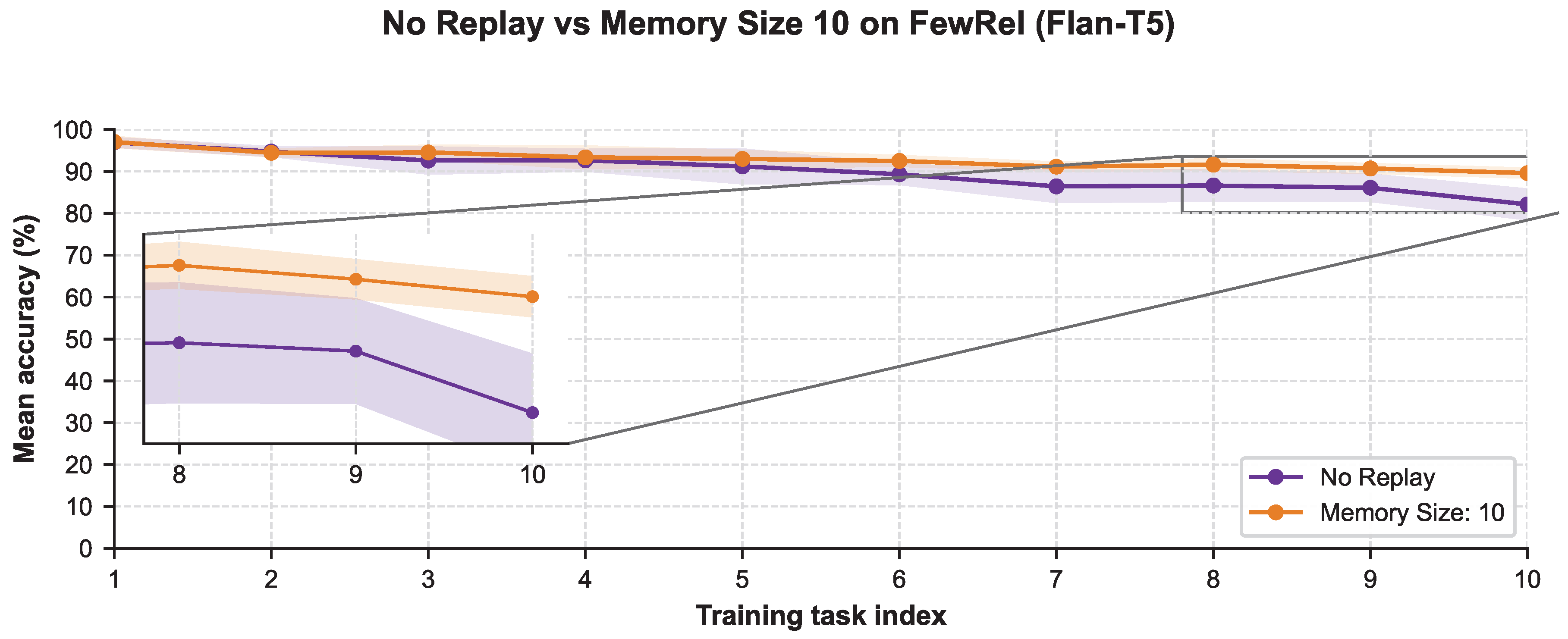

Memory replay improves the performance for Flan-T5 Base compared to the No Replay baseline, as indicated by p-value <

and p-value <

for memory sizes 10 and 15, respectively (see the FewRel comparison in

Figure A12, Appendix I). In contrast, a memory size of 5 does not significantly affect the performance, with a p-value of

; however, this should be reevaluated with a different number of iterations. Furthermore, memory replay with Mistral-7B, Llama3.1, and Qwen2.5 does not improve performance compared to No Replay, as shown in

Table 4. We also examine whether memory size (with replay) affects Llama2-7B-hf performance. Memory replay has a significant impact on the Llama2-7B-hf performance compared to the No Replay strategy when the memory size is 5 or 10.

Table 5.

Seen task accuracy (%) on TACRED for five large language models evaluated with different memory sizes. Arrows indicate the change relative to the previous memory size (↑ = increase, ↓ = decrease, = = no change).

Table 5.

Seen task accuracy (%) on TACRED for five large language models evaluated with different memory sizes. Arrows indicate the change relative to the previous memory size (↑ = increase, ↓ = decrease, = = no change).

| |

Task Index |

| Model |

Memory |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

| Flan-T5 Base |

No Replay |

96.1 |

96.5 |

95.5 |

95.7 |

95.3 |

94.4 |

93.5 |

94.1 |

94.0 |

92.7 |

| |

5 |

96.1 (=) |

96.1 (↓ 0.4) |

95.2 (↓0.3) |

95.2 (↓0.5) |

95.4 (↑ 0.1) |

94.6 (↑ 0.2) |

95.7 (↑ 2.2) |

96.2 (↑ 2.1) |

96.1 (↑ 2.1) |

95.2 (↑ 2.5) |

| |

10 |

96.1 (=) |

96.2 (↑ 0.1) |

95.7 (↑ 0.5) |

96.0 (↑ 0.8) |

95.7 (↑ 0.3) |

95.4 (↑ 0.8) |

96.1 (↑ 0.4) |

96.0 (↓ 0.2) |

96.3 (↑ 0.2) |

95.8 (↑ 0.6) |

| |

15 |

96.1 (=) |

95.8 (↓ 0.4) |

95.7 (=) |

96.0 (=) |

96.3 (↑ 0.6) |

96.3 (↑ 0.9) |

96.9 (↑ 0.8) |

96.7 (↑ 0.7) |

96.7 (↑ 0.4) |

96.3 (↑ 0.5) |

| Mistral-7B |

No Replay |

96.6 |

94.8 |

96.3 |

96.2 |

96.4 |

96.6 |

96.6 |

96.9 |

96.8 |

96.8 |

| |

5 |

96.6 (=) |

95.2 (↑ 0.4) |

96.9 (↑ 0.6) |

96.7 (↑ 0.5) |

96.9 (↑ 0.5) |

97.2 (↑ 0.6) |

96.9 (↑ 0.3) |

97.1 (↑ 0.2) |

97.2 (↑ 0.4) |

97.0 (↑ 0.2) |

| |

10 |

96.6 (=) |

95.3 (↑ 0.1) |

96.4 (↓ 0.5) |

95.9 (↓ 0.3) |

96.6 (↓ 0.3) |

97.0 (↓ 0.2) |

96.8 (↓ 0.1) |

96.9 (=) |

95.8 (↓ 1.0) |

96.9 (↓ 0.1) |

| |

15 |

96.6 (=) |

94.8 (↓ 0.5) |

95.2 (↓ 1.2) |

95.7 (↓ 0.2) |

96.5 (↓ 0.1) |

97.1 (↑ 0.1) |

97.2 (↑ 0.4) |

97.3 (↑ 0.4) |

96.8 (↑ 1.0) |

96.7 (↓ 0.2) |

| Llama2-7B-hf |

No Replay |

57.7 |

52.8 |

52.7 |

52.3 |

54.0 |

57.0 |

57.8 |

60.1 |

62.9 |

62.4 |

| |

5 |

57.7 (=) |

59.2 (↑ 6.4) |

55.5 (↑ 2.8) |

55.9 (↑ 3.6) |

56.5 (↑ 2.5) |

60.6 (↑ 3.6) |

59.5 (↑ 1.7) |

62.4 (↑ 2.3) |

64.2 (↑ 1.3) |

66.5 (↑ 4.1) |

| |

10 |

57.7 (=) |

57.6 (↓ 1.6) |

54.9 (↓ 0.6) |

55.8 (↓ 0.1) |

57.6 (↑ 1.1) |

62.0 (↑ 1.4) |

62.4 (↑ 2.9) |

65.3 (↑ 2.9) |

67.7 (↑ 3.5) |

70.6 (↑ 4.1) |

| |

15 |

57.7 (=) |

60.3 (↑ 2.7) |

58.4 (↑ 3.5) |

57.6 (↑ 1.8) |

57.2 (↓ 0.4) |

59.2 (↓ 2.8) |

59.9 (↓ 2.5) |

61.3 (↓ 4.0) |

63.1 (↓ 4.6) |

63.9 (↓ 6.7) |

| Llama3.1-8B |

No Replay |

89.1 |

86.4 |

86.9 |

85.4 |

85.7 |

85.2 |

84.7 |

84.5 |

83.8 |

83.4 |

| |

5 |

89.1 (=) |

85.6 (↓ 0.7) |

86.3 (↓ 0.5) |

85.4 (↓ 0.1) |

85.2 (↓ 0.4) |

83.7 (↓ 1.6) |

82.9 (↓ 1.8) |

81.4 (↓ 3.0) |

80.2 (↓ 3.6) |

79.1 (↓ 4.3) |

| |

10 |

89.1 (=) |

85.0 (↓ 0.6) |

85.6 (↓ 0.7) |

84.4 (↓ 1.0) |

85.1 (↓ 0.1) |

83.9 (↑ 0.3) |

83.1 (↑ 0.1) |

81.7 (↑ 0.3) |

80.0 (↓ 0.2) |

78.7 (↓ 0.3) |

| |

15 |

89.1 (=) |

85.2 (↑ 0.2) |

86.2 (↑ 0.6) |

84.9 (↑ 0.5) |

84.5 (↓ 0.6) |

83.1 (↓ 0.8) |

82.2 (↓ 0.9) |

81.3 (↓ 0.4) |

79.6 (↓ 0.4) |

78.2 (↓ 0.5) |

| Qwen2.5-7B |

No Replay |

93.0 |

91.9 |

91.3 |

91.2 |

91.4 |

91.7 |

91.7 |

91.8 |

91.8 |

91.2 |

| |

5 |

93.0 (=) |

91.8 (↓ 0.2) |

91.1 (↓ 0.2) |

91.2 (=) |

91.6 (↑ 0.1) |

91.9 (↑ 0.2) |

92.0 (↑ 0.3) |

92.0 (↑ 0.2) |

91.9 (↑ 0.2) |

91.4 (↑ 0.2) |

| |

10 |

93.0 (=) |

92.0 (↑ 0.3) |

91.2 (↑ 0.1) |

91.4 (↑ 0.2) |

91.8 (↑ 0.2) |

92.0 (↑ 0.1) |

92.0 (↑ 0.0) |

91.9 (↓ 0.1) |

91.9 (↓ 0.1) |

91.3 (↓ 0.1) |

| |

15 |

93.0 (=) |

91.6 (↓ 0.4) |

91.3 (↑ 0.1) |

91.3 (↓ 0.0) |

91.7 (↓ 0.1) |

91.9 (↓ 0.0) |

92.2 (↑ 0.1) |

92.2 (↑ 0.3) |

92.2 (↑ 0.3) |

91.6 (↑ 0.3) |

Non-incremental Training. We also tuned Flan-T5 and Mistral using the TACRED dataset without downsampling. However, we excluded the no_relation labeled samples, as defined in

Section 5.1.1. The results on the same test dataset in

Table 6 are nearly identical to the No Replay setting, as shown in

Table 5, demonstrating that memory replay improves the performance of Flan-T5 Base on the TACRED dataset. However, there is no significant improvement in Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 performance between No Replay and non-incremental training on the same dataset. We also evaluated these models on the full test dataset partition, excluding no_relation labeled samples.

Time Cost. We analyzed the time required to train each task without memory replay. For TACRED, the base training times per task are approximately 4 minutes for Flan-T5 Base, 9 minutes for Llama2-7B-hf, 7 minutes for Mistral-7B, 4 minutes for Llama-3.1-8B, and 5 minutes for Qwen2.5-7B, respectively. These durations become more significant when accumulated across all incremental tasks.

9

6.2. Hallucination Reduction Approaches

We observe Llama2-7B-hf’s tendency to hallucinate predictions in

Table 1 and

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, in which we aim to reduce hallucination rates by using sampling (decoding) methods [

47], thereby improving computational efficiency at test time. Because the results reported in

Table 1 and

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are obtained using greedy decoding, which considers the most probable token, we also examine alternative sampling strategies for test-time inference. We apply beam search (beam size = 5) and nucleus sampling (top-

p, with p =

) to generate improved responses to the given instructions. Nucleus sampling selects the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability is at least p and samples only from that set [

47]. In contrast, beam search considers the n most likely tokens, where n indicates the beam size

10 [

47].

Table 7 presents the results for Llama2-7B-hf on the Task 1 test set across five runs, corresponding to five distinct task combinations. The mean accuracy achieved with the beam search is 43.27%, compared with 39.95% for nucleus sampling. For Llama2-7B-hf in Task 1, applying beam decoding reduced the rate of Undefined predictions from 39.27% to 7.23%, indicating a substantial mitigation of hallucinated relation outputs. Beam search outperforms nucleus sampling on the Llama2-7B-hf Task 1 test set. Although we applied these decoding strategies to the Task 1 test set with Llama2-7B-hf, these results can be extended to other LLMs and may have similar trends. Alternative decoding strategies might reduce the hallucination rates when Llama2-7B-hf is used.

7. Discussion

CRE has primarily focused on incremental task learning (ITL), yet existing approaches still struggle to achieve effective forward knowledge transfer and often exhibit catastrophic forgetting. Although memory replay can mitigate forgetting, it offers limited adaptability during ITL and does not entirely prevent forgetting [

10,

24]. With recent advancements in LLMs, a central question arises:

How do LLMs influence knowledge transfer, particularly backward transfer, in continual relation extraction? To examine this, we evaluated three model categories: (i) a non-instruction-tuned model (Llama2-7B-hf), (ii) a smaller model (Flan-T5 Base, 250M), and (iii) instruction-tuned LLMs (Mistral-7B, Qwen2.5-7B, Llama-3.1-8B) within ITL settings. In this section, we discuss their behavior, compare them with state-of-the-art (SoTA) systems, and explore their potential for updating knowledge graphs (KGs).

Regarding knowledge transfer, Llama2-7B-hf gradually adapts to the instruction during ITL and exhibits a positive backward knowledge transfer. Flan-T5 Base performs consistently well across datasets, often matching the larger Mistral-7B model according to permutation tests (

Table A7 and

Table A8). Qwen2.5-7B also shows a positive backward knowledge transfer, likely due to task similarity [

11], whereas Llama-3.1-8B exhibits a negative backward knowledge transfer. Mistral-7B’s grouped-query and sliding-window attention mechanisms

11 [

22] may contribute to more stable optimization and reduce forgetting. Mistral’s relatively stable performance is evident from the task accuracies across ITL shown in

Figure A10 and

Figure A11 in Appendix G. In contrast, Flan-T5 exhibits noticeable forgetting on earlier tasks—particularly Tasks 1 through 4 in FewRel—as depicted in

Figure A8 in Appendix G. Therefore, these figures in Appendix G highlight Mistral’s stability and the tendency of the Flan-T5 Base model to forget earlier tasks. Among the evaluated LLMs, Mistral-7B remains the most stable overall, whereas Flan-T5 Base provides strong and reproducible performance at a substantially smaller scale when used with memory replay.

Error analysis further reveals that Llama2-7B-hf on both datasets and Qwen2.5-7B on TACRED reduce hallucinated relation types in earlier tasks at the end of ITL (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). In contrast, Flan-T5 Base produces more hallucinations when forgetting becomes severe (

Table 3). Unlike traditional CRE models that use classification heads, LLMs may generate relation labels that are not in the predefined set, reflecting a distinctive generative error mode (

Table A6). Although Llama2-7B-hf and Qwen2.5-7B mitigate such errors during ITL, they still trail Mistral-7B and Flan-T5 Base in final-task performance. The decoding ablation in

Table 7 shows that beam search and nucleus sampling reduce the number of undefined outputs compared with greedy decoding for Llama2-7B-hf in

Table 1.

Beyond error profiles, we next compare these models against SoTA CRE systems in

Table 1. Mistral-7B achieves strong performance on both datasets with minimal forgetting on FewRel and matches or surpasses earlier approaches such as DP-CRE. KIP achieves the best results on FewRel through prompt-based multi-head attention and memory replay, whereas our models outperform prior memory-replay baselines using the same K-means sampler (CRL, RP-CRE, and EMAR-BERT). Despite differing architectures, all evaluated LLMs outperform EMAR-BERT, underscoring the advantage of pretrained generative models (LLMs). Moreover, increasing memory sizes or even removing replay altogether still enables Mistral-7B, Flan-T5 Base, and Qwen2.5-7B to outperform previous methods (

Table 1 and

Table 5), reinforcing the benefit of pretrained initialization [

19].

These models also acquire task-specific representations of the instruction during training, meaning that the prediction quality can drop when inference-time prompts deviate from the learned pattern. Improving robustness typically requires training with paraphrased instruction signals, but integrating such instruction diversity is beyond the scope of our ITL setup.

For real-world KG construction, CRE supports incremental discovery of relation types during text-to-KG generation. However, LLMs may output undefined relation types when such labels are not explicitly included in the instructions. We mitigate this by enumerating task-specific relation types directly in the instruction (

Figure 2), enabling more controlled generation. Although Incremental Class Learning (ICL) aligns with online KG updates, ITL yields higher factual stability in our setting, particularly with smaller instruction-tuned models such as Flan-T5 Base or the inherently stable Mistral-7B. However, owing to the risk of false predictions, neither ICL nor ITL should be used for automatic KG expansion without dedicated fact-verification mechanisms [

48].

Overall, initializing CRE with LLMs, rather than randomly initialized architectures with classification heads, substantially improves the performance of the seen-task (

Table 1). This work provides the first systematic and reproducible benchmark of LLM behavior in CRE, offering practical insights into their stability and applicability.

8. Conclusion

This work presents the first systematic and reproducible benchmark of LLMs for continual relation extraction (CRE), highlighting stability and hallucination issues that have not been previously analyzed. We evaluated five LLMs—Flan-T5 Base, Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Llama2-7B-hf, Llama3.1-8B-Instruct, and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct—on FewRel and TACRED benchmarks in English under incremental task learning (ITL), focusing on knowledge transfer and catastrophic forgetting.

Mistral-7B shows slight forgetting on FewRel but achieves positive backward knowledge transfer on TACRED and surpasses prior methods in seen-task accuracy. Flan-T5 Base still suffers substantial forgetting despite memory replay. However, ablations confirm its effectiveness and identify optimal memory configurations. Additionally, memory replay does not statistically improve Mistral-7B, Llama-3.1-8B, or Qwen2.5-7B in TACRED, as these models already perform strongly without it. Llama2-7B-hf consistently exhibits strong knowledge transfer, mainly owing to reduced false predictions and its non-instruction-tuned nature. However, its overall performance remains below that of the instruction-tuned models. Interestingly, Mistral-7B, Flan-T5 Base, and Qwen2.5-7B outperform previous approaches on TACRED in terms of seen-task accuracy, even without memory replay.

These results provide practical guidance for the application of LLMs to CRE. Mistral-7B demonstrates strong stability, whereas Flan-T5 Base offers reproducibility with limited GPU memory. Memory replay benefits smaller instruction-tuned and base models (e.g., Flan-T5 Base and Llama2-7B-hf), but not larger instruction-tuned models, which already achieve high performance without it. Our findings also indicate that Llama-based models are more prone to hallucination, limiting their reliability for CRE. Additionally, Mistral’s minimal tendency to hallucination might help to continuously update knowledge graphs, whereas Flan-T5 provides reproducibility with limited resources, as discussed in

Section 7. Neither of these models can be used directly to update knowledge graphs across any domain without a fact-checking system.

Although our work is limited to five models, it offers initial, reproducible insights into LLM behavior in CRE. A key challenge is hallucinated (undefined) predictions resulting from next-token generation, with Llama2-7B-hf and Llama-3.1-8B showing the highest rates. Future work will extend these benchmarks with newer models and multilingual benchmark datasets, and explore techniques to reduce hallucinations, such as inference-time constraints and sampling, whose early results on Llama2-7B-hf are promising (

Section 6.2). In particular, we aim to mitigate hallucination on FewRel for Llama2-7B-hf and Llama-3.1-8B using test-time computation methods [

47], including beam search and nucleus sampling, as shown in our preliminary experiments in

Section 6.2.

9. Limitations

This work has the following limitations related to model coverage, computational constraints, methodological, and ethical scope, which we outline below to clarify the boundaries of our findings:

Model and Dataset Scope.

Model Coverage. Our benchmark evaluates a set of representative open-source LLMs selected for their architectural diversity and reproducibility. Although our core observations on knowledge transfer, memory replay, and hallucination behavior are expected to generalize across model families, they may not extend to substantially larger models or proprietary systems trained with undisclosed data or objectives.

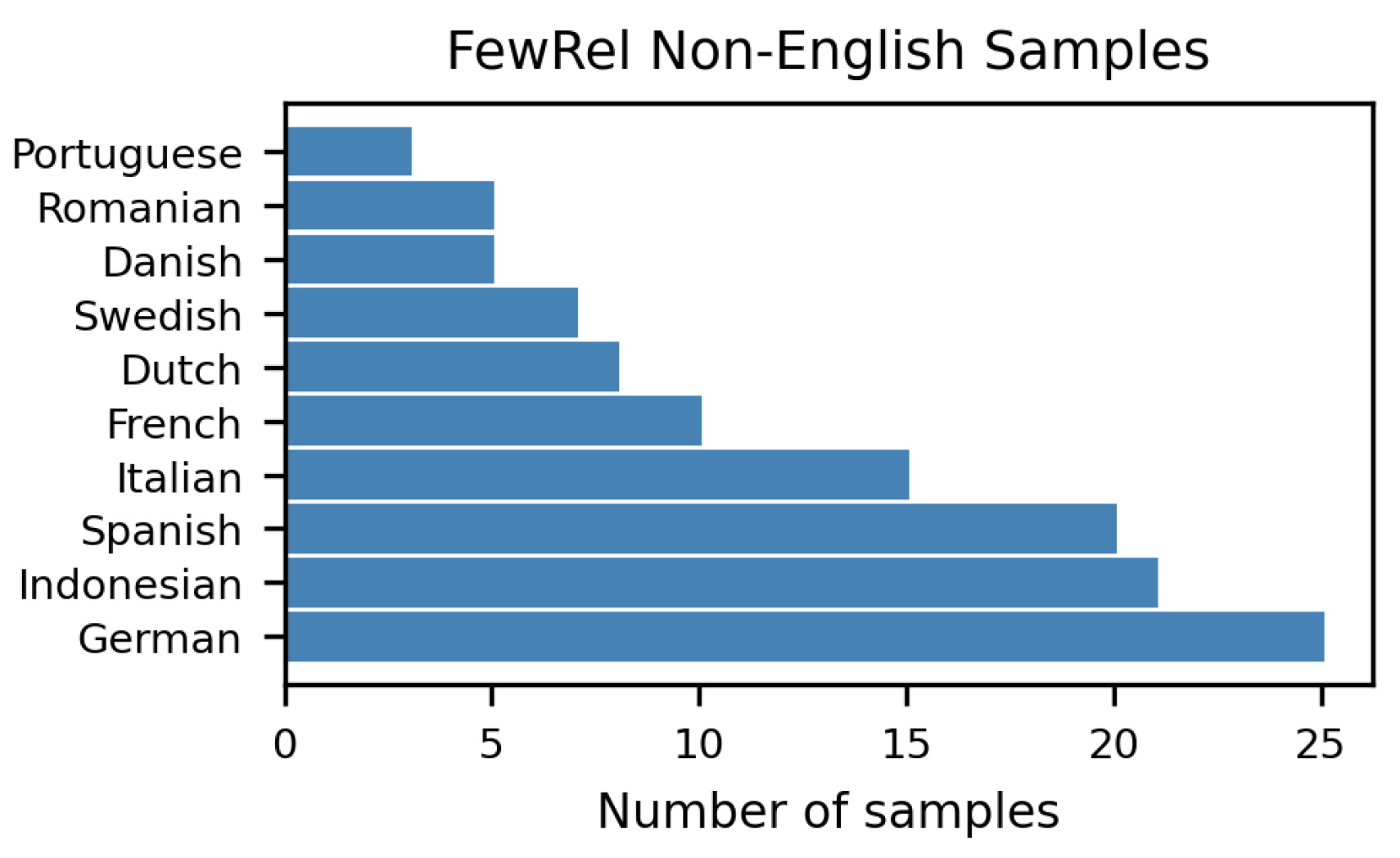

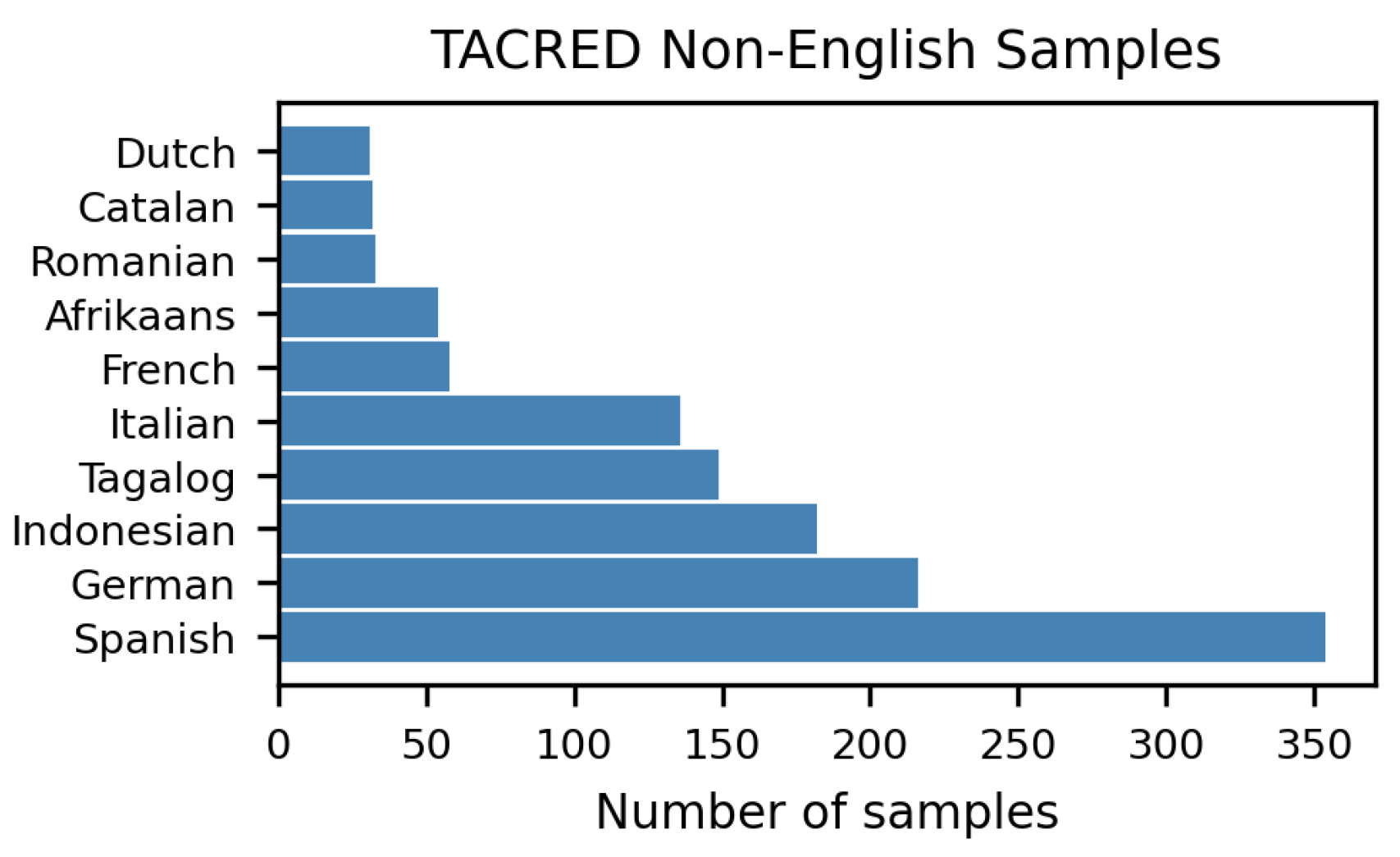

Language and Dataset Limitations. All experiments were conducted on the English benchmark datasets (TACRED and FewRel), reflecting the primary training domain of the evaluated LLMs. Although the datasets contain a small number of multilingual examples (Appendix B), our conclusions cannot be generalized to multilingual CRE. Extending the benchmark to multilingual and low-resource settings with multilingual LLMs remains an essential topic for future work.

Computational Constraints.

Memory Replay on FewRel. We did not perform memory-size ablations on FewRel due to its substantially larger task sequence, which leads to rapid growth in the replay buffer. Nevertheless, the No Replay vs. Memory Size (10) results shown in

Figure A12 (Appendix I) clearly support the findings obtained on TACRED with Flan-T5 Base, and memory replay improves the performance of Flan-T5 Base on FewRel as well.

Impact of Quantization (QLoRA). All models were tuned using a 4-bit QLoRA to ensure feasibility across multiple runs. Although this guarantees fairness, it limits our ability to isolate the effects of quantization on knowledge retention, catastrophic forgetting, and hallucination rates. Prior benchmarks (e.g., [

49]) indicate that QLoRA or LoRA can improve the performance of models such as Llama2-7B-hf; however, evaluating these effects directly remains outside the scope of this work.

Methodological Scope.

Focus on Memory Replay. Our analysis focuses on memory replay as the primary strategy for CL. A diversity-based memory sample selection algorithm, K-means, might miss complex samples. Nonetheless, LLMs depend heavily on sample diversity for robust performance.

Generality of Findings. The observed trends—e.g., replay benefiting smaller or base models, or instruction-tuned models showing limited improvement—are grounded in our empirical setting.

Ethical Scope.

Real-World Application. Although experiments were performed locally using open-source models, the ethical risks of deploying CRE systems remain unaddressed. Hallucinated relations can propagate misinformation in real-world settings, particularly in domains such as healthcare and biodiversity. Additional safeguards, such as fact-checking and human oversight, are required but beyond the scope of this work.

Bias in Models. This work does not assess potential biases in the LLMs or datasets. TACRED and FewRel include entity mentions that may introduce demographic or contextual biases (e.g., gender, age). Since such biases can lead to uneven or skewed relation predictions, the fairness implications of the models remain unexamined.

Overall, this benchmark provides initial but reproducible insights into LLM behavior during continual relation extraction.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions: Sefika Efeoglu

contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, and supervision. Adrian Paschke contributed to investigation, validation, supervision, and writing—review and editing. Sonja Schimmler contributed to writing—review and editing.

Informed Consent Statement

This work does not involve any human data, so no ethical concerns are associated with this work.

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Dataset Statistics

Appendix A.1. FewRel

Table A1 provides details of all the training, validation, and test sets for incremental task learning. Each task has eight relation types, and the training, validation, and test sets are 420, 120, and 120, respectively. The random seed is 42 for sampling, as stated in

Section 5.1, and the task splits are publicly available.

12

Table A1.

Train, validation, and test set splits for the FewRel dataset.

Table A1.

Train, validation, and test set splits for the FewRel dataset.

| Dataset |

Train |

Validation |

Test |

# of Relations |

| FewRel |

33600 |

11200 |

11200 |

80 |

Appendix A.2. TACRED

This section presents detailed statistics for the TACRED dataset in

Table A2. Because the TACRED dataset is imbalanced, we applied downsampling at the relation type level. The random seed is 42 for sampling as described in

Section 5.1. The specific task splits and their ordering follow previous works and are publicly available

13 for reproducibility.

Table A2.

Train, validation, and test set splits for incremental task learning on the TACRED dataset.

Table A2.

Train, validation, and test set splits for incremental task learning on the TACRED dataset.

| Dataset |

Train |

Validation |

Test |

# of Relations |

| TACRED |

7146 |

1452 |

1223 |

40 |

Appendix B. Languages in Datasets

This section presents samples of datasets in different languages, as detected by Python

langdetect in

Figure A1 and

Figure A2.

Figure A1.

Non-English languages in FewRel.

Figure A1.

Non-English languages in FewRel.

Figure A2.

Non-English languages in TACRED.

Figure A2.

Non-English languages in TACRED.

Appendix C. Parameters

The hyperparameters and LoRA parameters are presented in

Table A3 and

Table A4, respectively.

Table A3 lists the model hyperparameters aligned with the base model and the model cards in footnotes 1-5. In

Table A4, LoRA adapters are applied to the attention projection modules:

key (

k),

query (

q),

value (

v), and

output (

o).

Table A3.

Training hyperparameters used for TACRED and FewRel. EP, BS, and LR refer to epoch, batch size, and learning rate, respectively.

Table A3.

Training hyperparameters used for TACRED and FewRel. EP, BS, and LR refer to epoch, batch size, and learning rate, respectively.

| Model |

TACRED |

FewRel |

| |

EP |

BS |

LR |

Trainer |

EP |

BS |

LR |

Trainer |

| Flan-T5 Base |

5 |

8 |

0.001 |

Seq2Seq |

5 |

16 |

0.001 |

Seq2Seq |

| Mistral-7B |

5 |

4 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

5 |

8 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

| Llama2-7B |

5 |

4 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

5 |

8 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

| Llama-3.1-8B |

5 |

4 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

5 |

8 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

| Qwen2.5-7B |

5 |

4 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

5 |

8 |

0.0002 |

SFT |

Table A4.

Languages represented in the FewRel dataset.

Table A4.

Languages represented in the FewRel dataset.

| Model |

|

Rank |

|

Task Type |

| Flan-T5 Base |

32 |

4 |

0.01 |

Seq2SeqLM |

| Mistral-7B |

16 |

64 |

0.10 |

CausalLM |

| Llama2-7B |

16 |

64 |

0.10 |

CausalLM |

| Llama-3.1-8B |

16 |

64 |

0.10 |

CausalLM |

| Qwen2.5-7B |

16 |

64 |

0.10 |

CausalLM |

Appendix D. Permutation Test for Undefined Predictions

As shown in

Table A5, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of undefined relation types between tasks 1 and 10 in the TACRED dataset with Llama2-7B-hf. This evaluation was conducted on the test set for Task 1 to assess whether the drop was significant when the model was trained for the final task (Task 10). By contrast, for the FewRel dataset, the reduction in undefined relation types is statistically significant across multiple training iterations, with p-values below 0.05. Random seeds were set to 42 for all experiments.

Table A5.

Permutation test comparing Task 1 test set after training on Task 1 train and Task 10 train on Llama2-7B-hf for hallucination evaluation.

Table A5.

Permutation test comparing Task 1 test set after training on Task 1 train and Task 10 train on Llama2-7B-hf for hallucination evaluation.

| Iteration |

TACRED |

FewRel |

| |

Diff (%) |

p-value |

Diff (%) |

p-value |

| 100 |

2.40 |

0.2000 |

433.00 |

0.0300 |

| 1000 |

2.40 |

0.2510 |

433.00 |

0.0250 |

| 10000 |

2.40 |

0.2642 |

433.00 |

0.0305 |

Appendix E. Examples Predictions

Appendix E.1. Llama2 Hallucinations

The following hallucinated prediction was identified in the Task 1 test dataset, at the beginning of the Llama2-7B-hf incremental tuning, and the projection was normalized at the end of training for the same test sample, as shown below.

Figure A3.

Sample prediction across incremental task learning with Llama2-7B-hf.

Figure A3.

Sample prediction across incremental task learning with Llama2-7B-hf.

Appendix E.2. Categories of Undefined Relations

Table A6.

Examples of invalid relation predictions across different error categories.

Table A6.

Examples of invalid relation predictions across different error categories.

| Category |

Similar Context |

Part of Ground-Truth |

New Relation |

Fine-Grained Version of Ground-Truth |

| Ground-Truth |

head of government, screenwriter, has part |

country, location |

– |

child, sibling, spouse |

| Prediction |

leader, author, component of |

country of, located in |

Japanese cargoer, Christmas, rail |

son or daughter, sister or brother, wife or husband |

| Models |

Flan-T5, Llama-3.1, Qwen2.5 |

Flan-T5, Llama2, Llama-3.1, Qwen2.5 |

all models |

Flan-T5, Llama-3.1, Qwen2.5 |

Appendix F. Confusion Matrices on FewRel Dataset

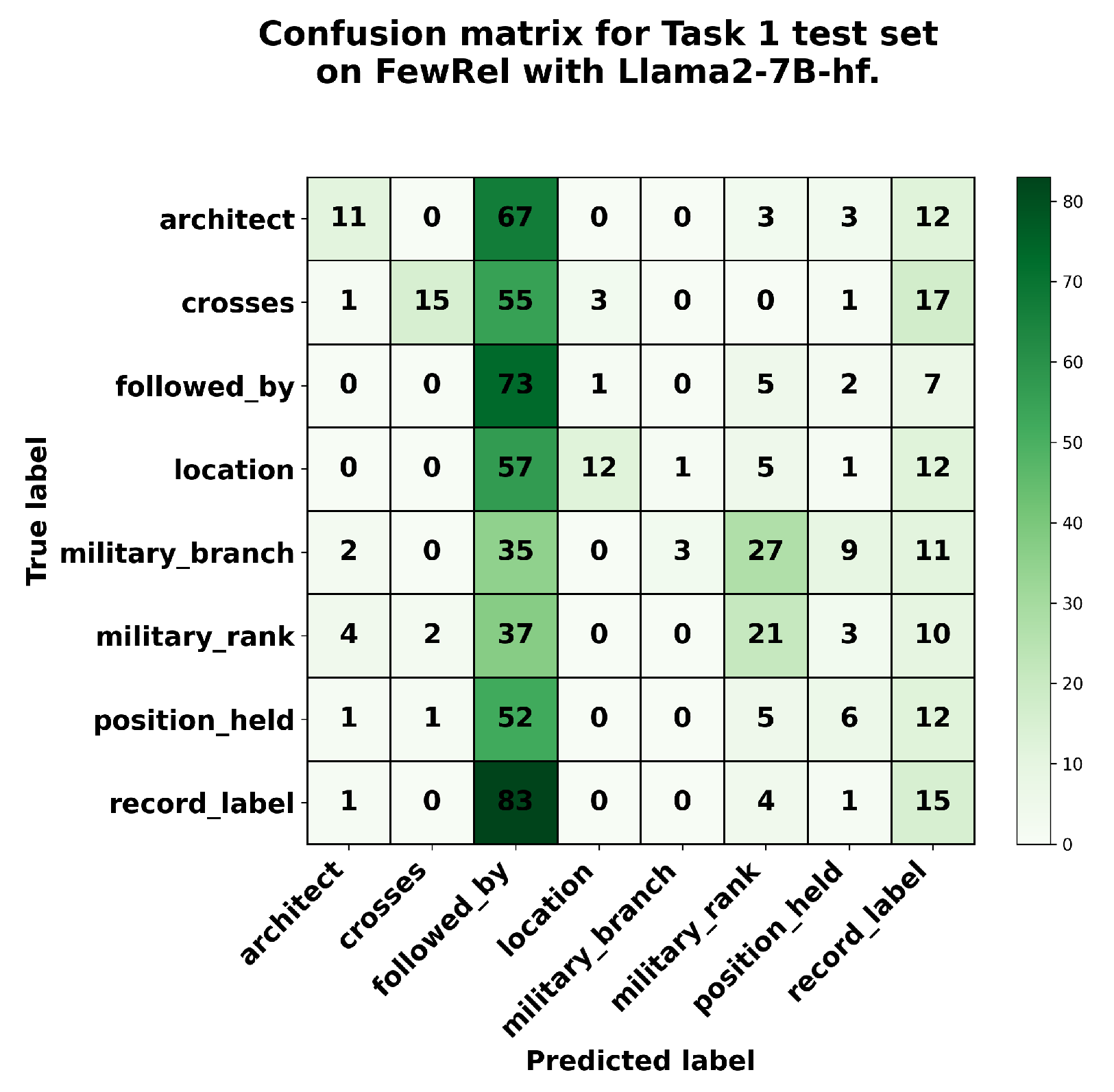

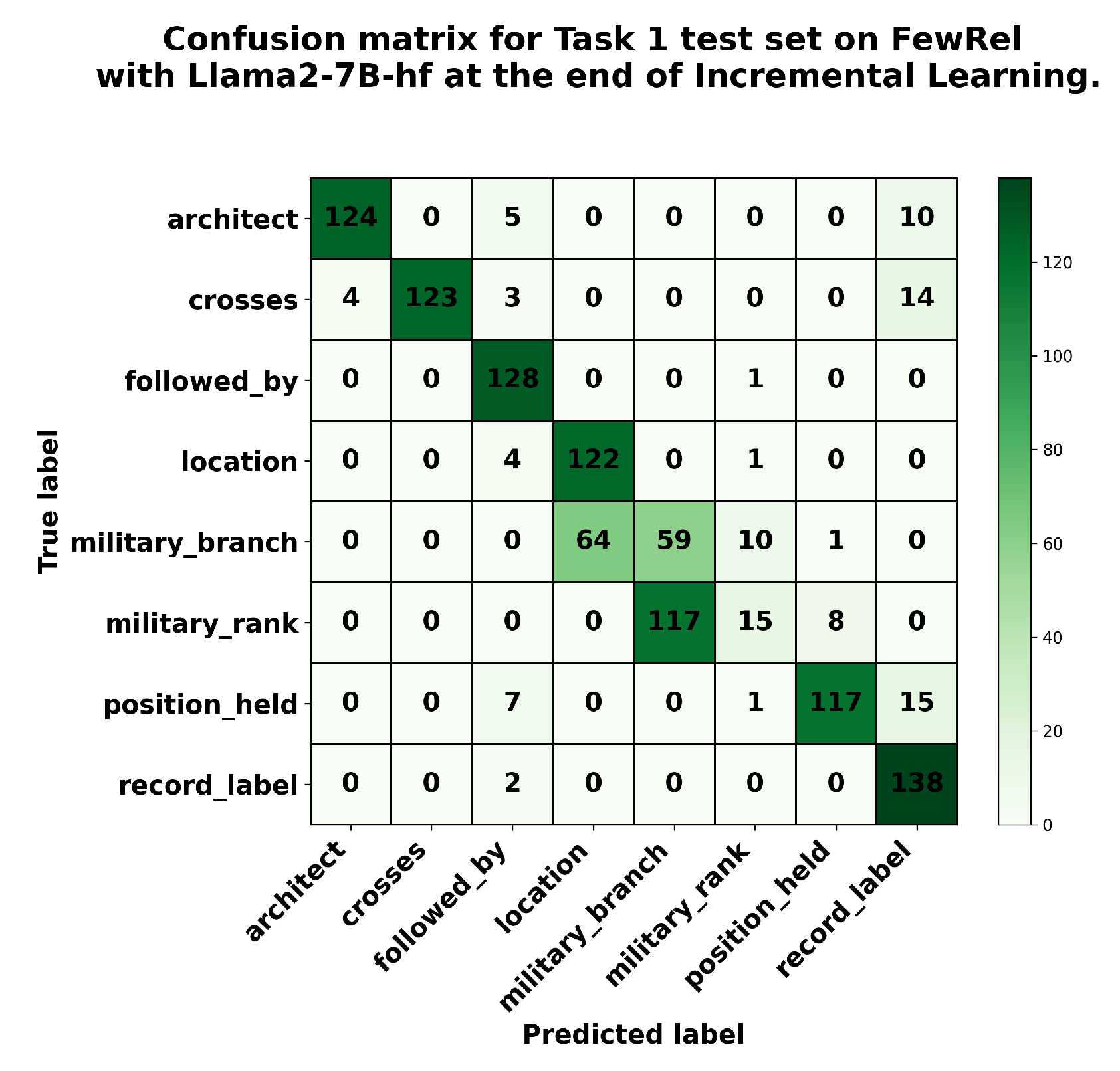

We also analyzed the performance of these language models on the FewRel dataset. Llama2-7B-hf demonstrates comparable positive backward knowledge transfer on FewRel (see

Figure 4)—while reducing hallucinated predictions by the completion of ITL. This reduction is evident from the decrease in false predictions throughout ITL, as shown in

Figure A4 and

Figure A5. In conclusion, language models can generate hallucinated predictions when they fail to transfer previously learned knowledge. Additionally, the number of hallucinated predictions decreased when backward knowledge transfer occurred, as observed in Llama2-7B-hf.

Figure A4.

Confusion matrix for the Task 1 test set after initial training on FewRel (run 1) with Llama2-7B-hf.

Figure A4.

Confusion matrix for the Task 1 test set after initial training on FewRel (run 1) with Llama2-7B-hf.

Figure A5.

Confusion matrix for the Task 1 test set at the end of incremental task learning in FewRel (run 1) with Llama2-7B-hf.

Figure A5.

Confusion matrix for the Task 1 test set at the end of incremental task learning in FewRel (run 1) with Llama2-7B-hf.

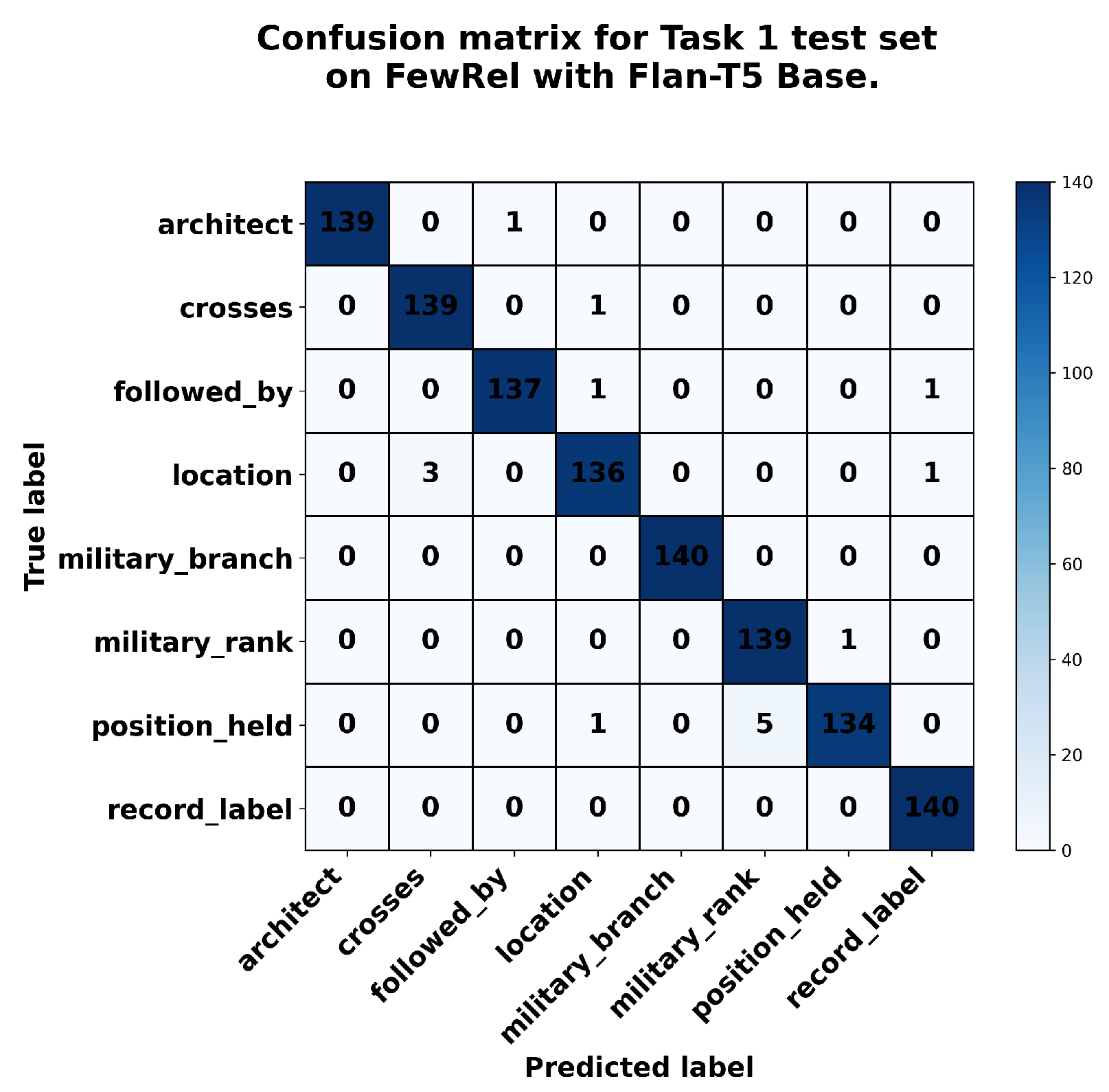

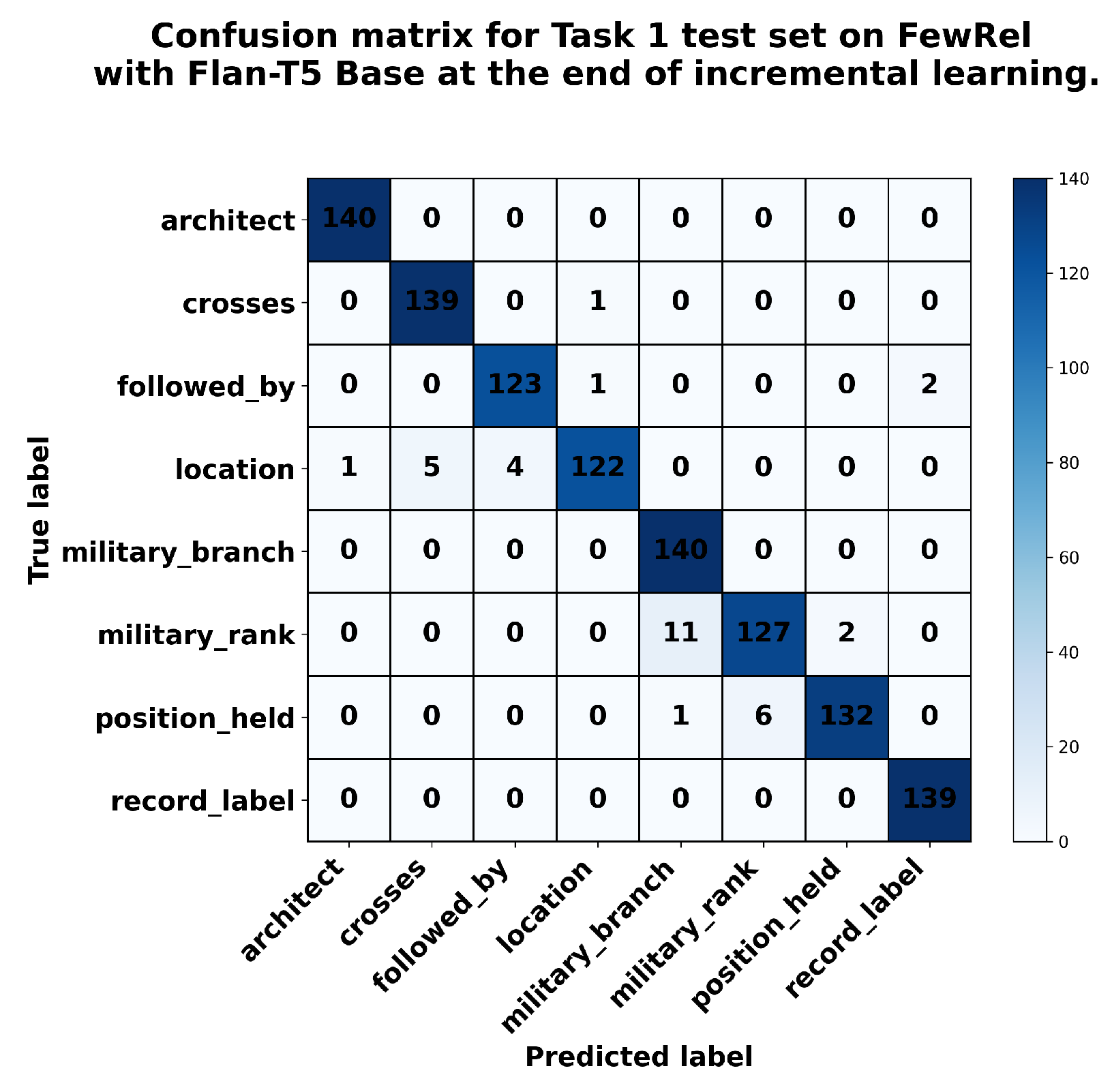

Moreover, we illustrate Flan T5 Base’s behavior using a confusion matrix, which shows how the test dataset for Task 1 performs during ITL. The Flan-T5 Base performs better on Task 1’s test dataset after training on Task 1 train set (see

Figure A6); however, it generates hallucinated prediction responses that are not among the predefined relation types—when catastrophic forgetting occurs, as shown in

Figure A7. Note that the FewRel test dataset contained 140 samples per relation type. When calculating the number of predictions in the confusion matrices below, we excluded the hallucination statistics.

Figure A6.

Confusion matrix for Task 1 in FewRel during incremental task learning (run 1) with Flan-T5 Base.

Figure A6.

Confusion matrix for Task 1 in FewRel during incremental task learning (run 1) with Flan-T5 Base.

Figure A7.

Confusion matrix for Task 10 in FewRel during incremental task learning (run 1) with Flan-T5 Base.

Figure A7.

Confusion matrix for Task 10 in FewRel during incremental task learning (run 1) with Flan-T5 Base.

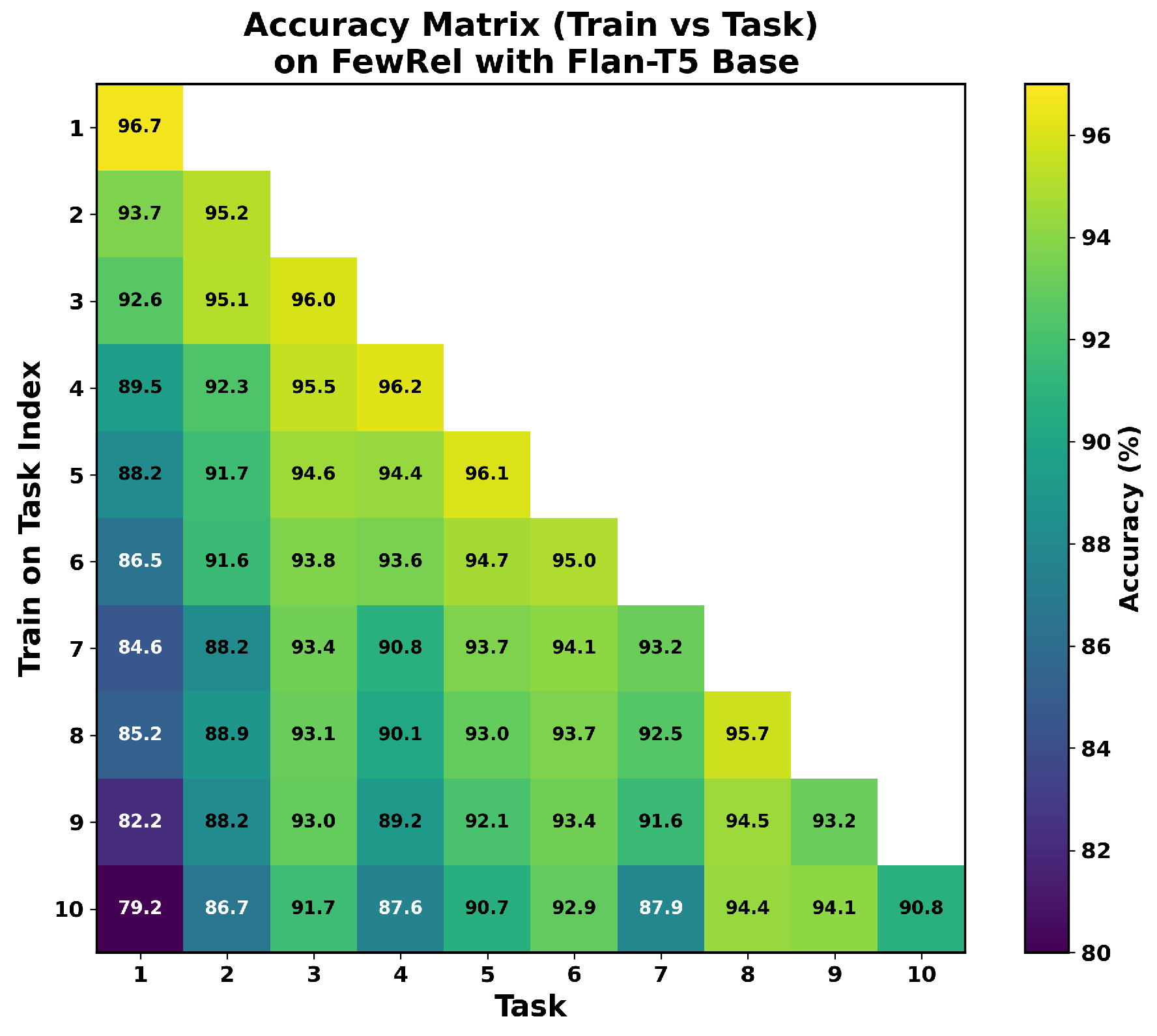

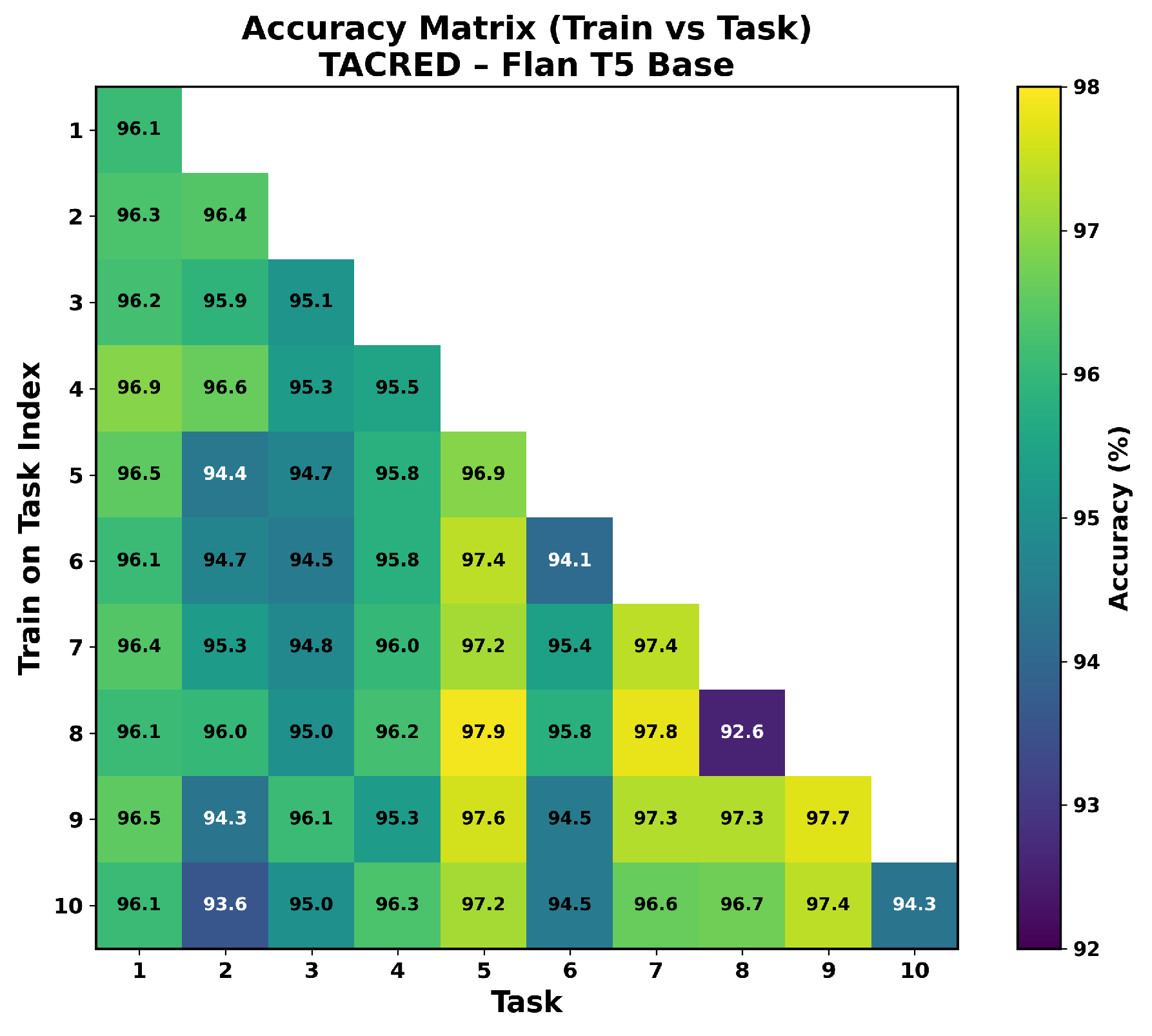

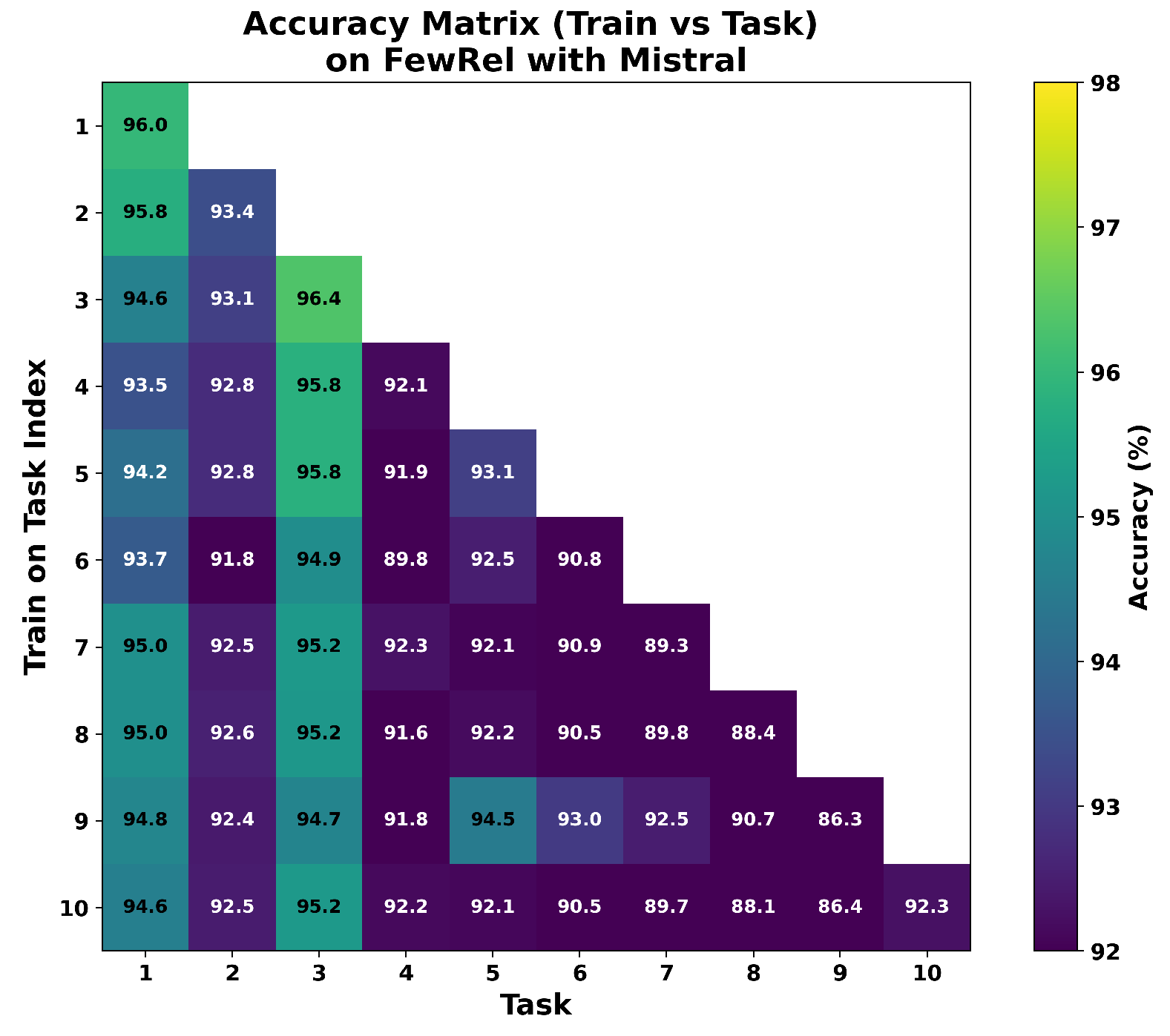

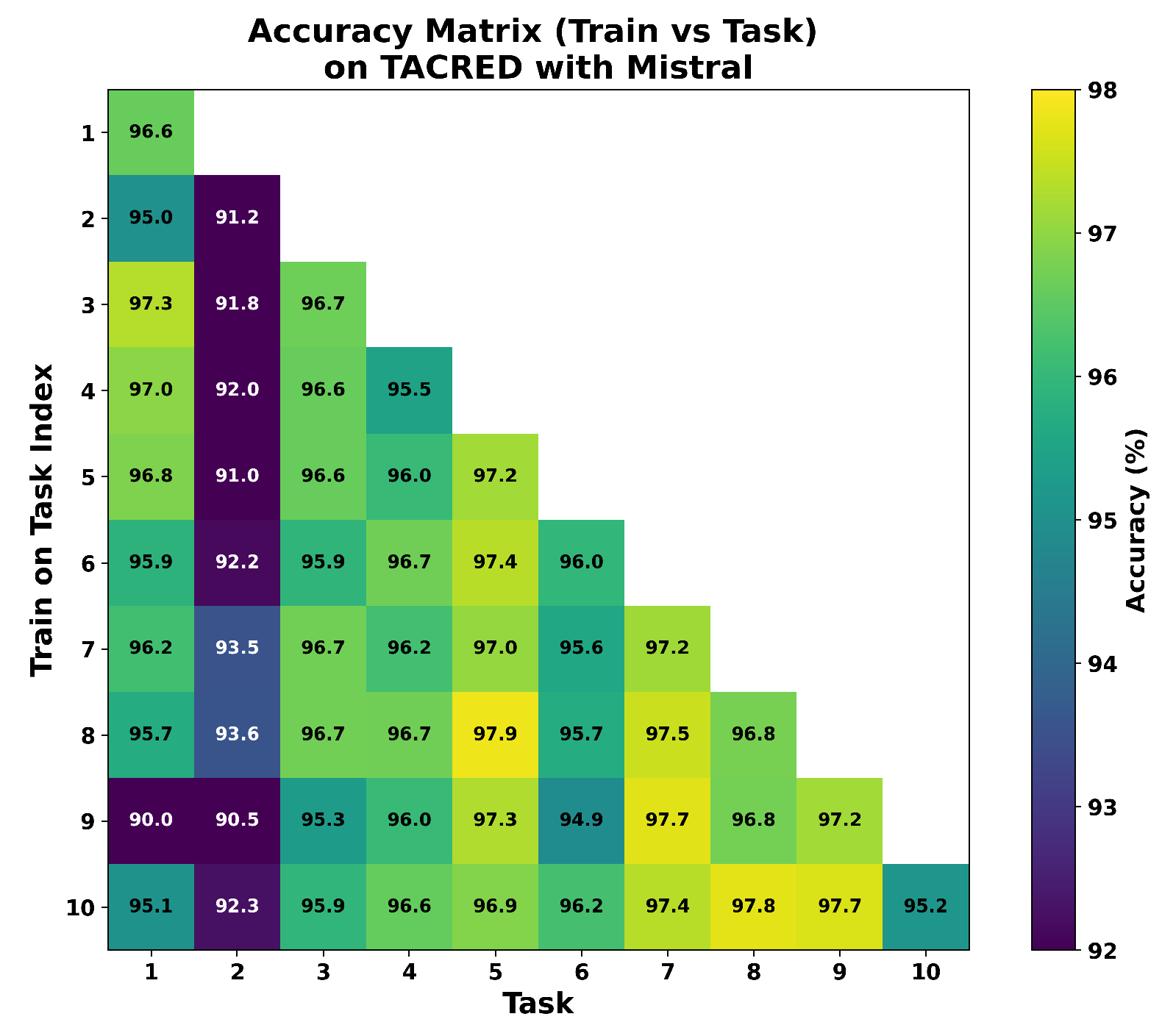

Appendix G. Accuracy Matrices

We provide accuracy matrices corresponding to the results in

Table 1. The matrices shown in

Figure A8,

Figure A9,

Figure A10 and

Figure A11 are consistent with the BWT results reported in

Table 3. These figures illustrate the Test accuracy of the corresponding task across task incremental training. Even though Flan-T5 achieves high accuracy on the Task 1 test set of FewRel at the beginning, its accuracy has since declined to 79.2% from 96.7% (

Figure A8). In contrast, Task 1 test set accuracy has slightly decreased to 94.6% from 86.0% with Mistral in FewRel (

Figure A10). However, for small datasets or fewer relation types in the task of TACRED, Flan-T5 demonstrated less forgetting as shown in

Figure A9, and Mistral is still almost stable as given in

Figure A11.

Figure A8.

Accuracy matrix on FewRel with Flan-T5.

Figure A8.

Accuracy matrix on FewRel with Flan-T5.

Figure A9.

Accuracy matrix on TACRED with Flan-T5.

Figure A9.

Accuracy matrix on TACRED with Flan-T5.

Figure A10.

Accuracy matrix on FewRel with Mistral.

Figure A10.

Accuracy matrix on FewRel with Mistral.

Figure A11.

Accuracy matrix on TACRED with Mistral.

Figure A11.

Accuracy matrix on TACRED with Mistral.

Appendix H. Permutation Test on Main Results

Table A7 and

Table A8 present the permutation test results comparing Mistral and Flan-T5 in

Table 1 using a fixed random seed (42) and reporting 95% confidence intervals and

p-values (10,000 shuffles) over five runs with fixed task orders.

Table A7.

Mistral vs. Flan-T5 across tasks. Values are mean scores over runs (seed 42) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and nonparametric permutation p-values (10,000 shuffles) on TACRED. Tasks are evaluated in a fixed task order (1–10).

Table A7.

Mistral vs. Flan-T5 across tasks. Values are mean scores over runs (seed 42) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and nonparametric permutation p-values (10,000 shuffles) on TACRED. Tasks are evaluated in a fixed task order (1–10).

| Task |

Mean (Flan-T5) |

Mean (Mistral) |

(Mistral-Flan-T5) |

95% CI [low, high] |

p-value |

| 1 |

0.961 |

0.966 |

0.005 |

[0.902, 0.992] |

0.817 |

| 2 |

0.962 |

0.948 |

-0.014 |

[0.908, 0.976] |

0.595 |

| 3 |

0.957 |

0.964 |

0.007 |

[0.951, 0.977] |

0.405 |

| 4 |

0.960 |

0.960 |

-0.001 |

[0.947, 0.970] |

0.913 |

| 5 |

0.956 |

0.966 |

0.009 |

[0.957, 0.974] |

0.468 |

| 6 |

0.954 |

0.970 |

0.016 |

[0.960, 0.979] |

0.135 |

| 7 |

0.961 |

0.968 |

0.007 |

[0.958, 0.977] |

0.357 |

| 8 |

0.960 |

0.969 |

0.009 |

[0.962, 0.977] |

0.278 |

| 9 |

0.963 |

0.958 |

-0.005 |

[0.931, 0.977] |

0.889 |

| 10 |

0.958 |

0.969 |

0.011 |

[0.962, 0.977] |

0.246 |

Table A8.

Comparison of Mistral vs. Flan-T5 across tasks. Values are mean accuracies over runs (seed ) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and nonparametric permutation p-values (10,000 shuffles) on FewRel. Tasks are evaluated in fixed task order (1–10). Significant results () are in bold.

Table A8.

Comparison of Mistral vs. Flan-T5 across tasks. Values are mean accuracies over runs (seed ) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and nonparametric permutation p-values (10,000 shuffles) on FewRel. Tasks are evaluated in fixed task order (1–10). Significant results () are in bold.

| Task |

Mean (Flan-T5) |

Mean (Mistral) |

(Mistral-Flan-T5) |

95% CI [low, high] |

p-value |

| 1 |

0.967 |

0.960 |

-0.007 |

[0.910, 0.988] |

0.937 |

| 2 |

0.945 |

0.946 |

0.002 |

[0.899, 0.983] |

0.952 |

| 3 |

0.946 |

0.947 |

0.002 |

[0.919, 0.974] |

0.929 |

| 4 |

0.934 |

0.936 |

0.002 |

[0.890, 0.970] |

0.976 |

| 5 |

0.930 |

0.936 |

0.006 |

[0.907, 0.959] |

0.722 |

| 6 |

0.925 |

0.923 |

-0.003 |

[0.905, 0.938] |

0.841 |

| 7 |

0.912 |

0.925 |

0.013 |

[0.915, 0.934] |

0.127 |

| 8 |

0.916 |

0.919 |

0.003 |

[0.914, 0.923] |

0.714 |

| 9 |

0.907 |

0.923 |

0.016 |

[0.906, 0.950] |

0.373 |

| 10 |

0.896 |

0.914 |

0.017 |

[0.912, 0.915] |

0.024 |

Appendix I. No Replay vs Memory Replay on FewRel

Figure A12.

No Replay vs memory size 10 results with Flan-T5 Base on FewRel.

Figure A12.

No Replay vs memory size 10 results with Flan-T5 Base on FewRel.

References

- Sheth, A.; Padhee, S.; Gyrard, A. Knowledge Graphs and Knowledge Networks: The Story in Brief. IEEE Internet Computing 2019, 23, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Grishman, R. Information Extraction. IEEE Intelligent Systems 2015, 30, 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Biesialska, M.; Biesialska, K.; Costa-jussà, M.R. Continual Lifelong Learning in Natural Language Processing: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; Scott, D.; Bel, N.; Zong, C., Eds., Barcelona, Spain (Online), 12 2020; pp. 6523–6541. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, J.; Palade, V.; Yu, Z. Continual Relation Extraction via Linear Mode Connectivity and Interval Cross Training. Knowledge-Based Systems 2023, 264, 110288. [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, B. Relational Representation Learning for Zero-Shot Relation Extraction with Instance Prompting and Prototype Rectification. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2023, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, T.; Lin, B.; Cao, Y.; Sui, Z. Enhancing Continual Relation Extraction via Classifier Decomposition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Okazaki, N., Eds., Toronto, Canada, 7 2023; pp. 10053–10062. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Gao, K. Consistent Representation Learning for Continual Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; Muresan, S.; Nakov, P.; Villavicencio, A., Eds., Dublin, Ireland, 5 2022; pp. 3402–3411. [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ngo Van, L.; Nguyen, T.H. Continual Relation Extraction via Sequential Multi-Task Learning. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 18444–18452. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ju, S.; Sun, J.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y. Efficient Lifelong Relation Extraction with Dynamic Regularization. In Proceedings of the Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing; Zhu, X.; Zhang, M.; Hong, Y.; He, R., Eds., Cham, 2020; pp. 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yang, D.; Yu, J.; Hu, C.; Cheng, J.; Yi, J.; Xiao, Y. Refining Sample Embeddings with Relation Prototypes to Enhance Continual Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); Zong, C.; Xia, F.; Li, W.; Navigli, R., Eds., Online, 8 2021; pp. 232–243. [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, G.M.; Soures, N.; Kudithipudi, D. 1.09 - Continual learning and catastrophic forgetting. In Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference; Wixted, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2025; pp. 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 6 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, B.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, R. Prompt-Based Prototypical Framework for Continual Relation Extraction. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2022, 30, 2801–2813. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Shi, X. Consistent Prototype Learning for Few-Shot Continual Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Okazaki, N., Eds., Toronto, Canada, 7 2023; pp. 7409–7422. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, M. Distilling Causal Effect of Data in Continual Few-Shot Relation Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024); Calzolari, N.; Kan, M.Y.; Hoste, V.; Lenci, A.; Sakti, S.; Xue, N., Eds., Torino, Italia, 5 2024; pp. 5041–5051.

- Shlyk, D.; Groza, T.; Mesiti, M.; Montanelli, S.; Cavalleri, E. REAL: A Retrieval-Augmented Entity Linking Approach for Biomedical Concept Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing, 2024, pp. 380–389. [CrossRef]

- Taffa, T.A.; Usbeck, R. Bridge-Generate: Scholarly Hybrid Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, New York, NY, USA, 2025; WWW ’25, pp. 1321–1325. [CrossRef]

- Efeoglu, S.; Paschke, A. Retrieval-Augmented Generation-Based Relation Extraction. Semantic Web 2025, 16, 22104968251385519, [. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.W.; Sun, H.L.; Ning, J.; Ye, H.J.; Zhan, D.C. Continual Learning with Pre-Trained Models: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-24; Larson, K., Ed. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 8 2024, pp. 8363–8371. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, V.; Chen, D.; Angeli, G.; Manning, C.D. Position-aware Attention and Supervised Data Improve Slot Filling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Palmer, M.; Hwa, R.; Riedel, S., Eds., Copenhagen, Denmark, 9 2017; pp. 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhu, H.; Yu, P.; Wang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. FewRel: A Large-Scale Supervised Few-Shot Relation Classification Dataset with State-of-the-Art Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E.; Chiang, D.; Hockenmaier, J.; Tsujii, J., Eds., Brussels, Belgium, 10 2018; pp. 4803–4809. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2310.06825]. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2307.09288]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Yu, M.; Guo, X.; Chang, S.; Wang, W.Y. Sentence Embedding Alignment for Lifelong Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 6 2019; pp. 796–806. [CrossRef]

- Jialan, L.; Weishan, K.; Lixi, C.; Hua, Y. Improving Continual Relation Extraction with LSTM and Back Forward Projection. In Proceedings of the 2023 20th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), 2023, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, C.; Tan, Z.; Xu, H.; Ge, B. Continual Few-Shot Relation Extraction with Prompt-Based Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the Web and Big Data; Song, X.; Feng, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Min, G., Eds., Singapore, 2024; pp. 312–327. [CrossRef]

- Tirsogoiu, D.M.; Marginean, A. From learned to new relations through generative models combined with relations clustering and few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 381–388. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Song, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, S. Rationale-Enhanced Language Models are Better Continual Relation Learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Bouamor, H.; Pino, J.; Bali, K., Eds., Singapore, 12 2023; pp. 15489–15497. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. FPrompt-PLM: Flexible-Prompt on Pretrained Language Model for Continual Few-Shot Relation Extraction. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2024, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Hovy, E.; Sun, Y. Pre-Trained Language Models and Their Applications. Engineering 2023, 25, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.l.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06825 2023. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. OpenAI 2019. Accessed: 2024-11-15.

- Chung, H.W.; Hou, L.; Longpre, S.; Zoph, B.; Tay, Y.; Fedus, W.; Li, E.; Wang, X.; Dehghani, M.; Brahma, S.; et al. Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 7 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hwang, J.N.; Rose, C.; Wallace, F. Uncertainty sampling based active learning with diversity constraint by sparse selection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 19th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yan, Z.; Li, C. Class Incremental Learning with Important and Diverse Memory. In Proceedings of the Image and Graphics; Lu, H.; Ouyang, W.; Huang, H.; Lu, J.; Liu, R.; Dong, J.; Xu, M., Eds., Cham, 2023; pp. 164–175. [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.; Thanh, N.X.; Anh, N.H.; Hai, N.L.; Le, T.; Ngo, L.V.; Nguyen, T.H. Preserving Generalization of Language Models in Few-Shot Continual Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA, 11 2024; pp. 13771–13784. [CrossRef]

- Madaan, A.; Rajagopal, D.; Tandon, N.; Yang, Y.; Bosselut, A. Conditional Set Generation Using Seq2seq Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Goldberg, Y.; Kozareva, Z.; Zhang, Y., Eds., Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12 2022; pp. 4874–4896. [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs, 2023, [arXiv:cs.LG/2305.14314]. [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CL/2106.09685]. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, D.; Wang, N.; Liu, T.; Gao, X. Task-Aware Orthogonal Sparse Network for Exploring Shared Knowledge in Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning; Salakhutdinov, R.; Kolter, Z.; Heller, K.; Weller, A.; Oliver, N.; Scarlett, J.; Berkenkamp, F., Eds. PMLR, 7 2024, Vol. 235, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 19153–19164. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, X.; Li, Y.F.; Haffari, G.; Qi, G.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, G. Curriculum-Meta Learning for Order-Robust Continual Relation Extraction. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 35, 10363–10369. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Dai, Y.; Gao, T.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Sun, M.; Zhou, J. Continual Relation Learning via Episodic Memory Activation and Reconsolidation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 7 2020; pp. 6429–6440. [CrossRef]