Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- show that Hamiltonian Monte Carlo can draw stable posterior samples in a correlated, high–dimensional survival setting,

- compare predictive accuracy, discrimination, and calibration against a tuned ridge Cox baseline, and

- check that the genes kept by the model contain known biology, for example the PAM50 signature first reported in Curtis et al. [14],

- and, importantly, provide theoretical justification for the BEN–Cox in which we formalize a Bayesian elastic–net grouping effect and a posterior contraction result under sparsity (see Section 2.5 and Appendix A).

2. Methodology

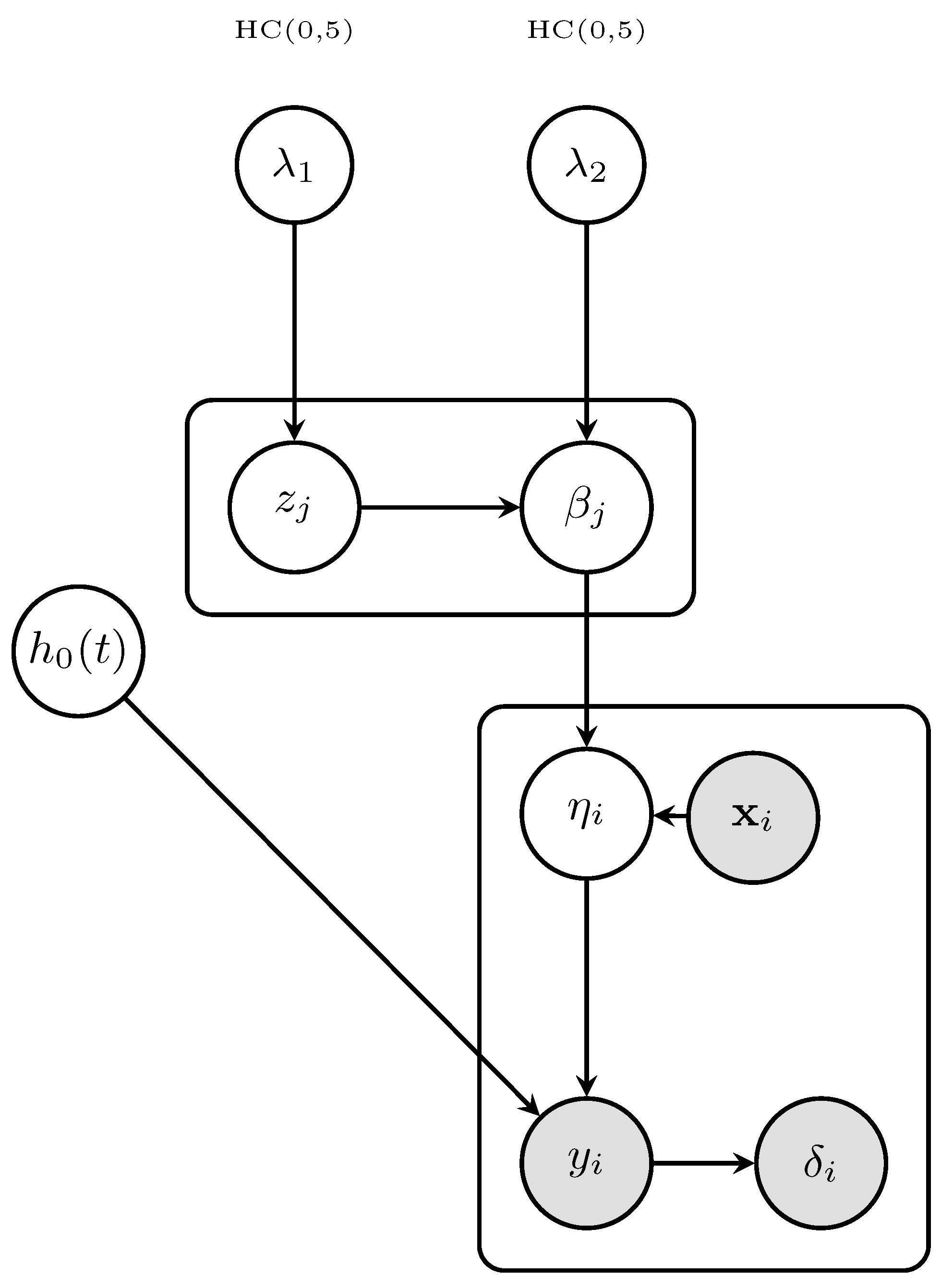

2.1. Model Specification

2.2. Bayesian Elastic–Net Prior

2.3. Posterior Distribution

2.4. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Inference

2.5. Theoretical Properties

Assumptions

- (A1)

- Columns of are z-scored on the training split; and entries are bounded.

- (A2)

- As a Cox model regularity condition, event times lie in a compact interval and the baseline hazard is locally bounded; is twice continuously differentiable (see [1]).

- (A3)

- There exists such that for all v with support S, , in a neighbourhood of .

- (A4)

- As a sparsity assumption, the truth is –sparse with .

- (A5)

3. Data

3.1. Cohort Description

3.2. Outcome

3.3. Predictors

- Gene expression : The METABRIC dataset provides Illumina HT-12 v3 micro-array measurements summarised at the gene level. In the version used here this block contains gene–expression features, indexed from the BRCA1 gene onwards. While the original METABRIC platform measures many more micro-array gene-level features, we restrict attention to this gene-level expression matrix for a more stable and reproducible design.

- Clinical covariates : age at diagnosis, tumour size, histological grade, lymph-node status and treatment indicators (hormone/chemotherapy) are also available in the downloaded dataset. These variables are not used in the present study but are retained for potential future work and for possible extensions of the BEN–Cox model.

3.4. Preprocessing

4. Application

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Baseline Models

- Null Cox: a Cox model with no gene-expression covariates, i.e., all subjects share the same baseline hazard (no covariate effects). This provides a no-information baseline for discrimination and absolute-risk calibration.

- Ridge Cox : an -penalised Cox model fitted with glmnet, where the penalty is chosen by five-fold cross-validation on the training set. This is a natural frequentist benchmark for high-dimensional survival modelling when sparsity is not enforced explicitly.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

| Algorithm 1: BEN–Cox pipeline |

| Input: gene matrix , times , events . |

| Output: posterior draws , test-set performance metrics. |

| 1. Pre-processing |

| 1.1 Remove gene-level features whose variance is below the 10th percentile [14]. |

| 1.2 z-score each column of using training-set moments. |

| 2. Train–test split |

| 2.1 Randomly split subjects 80/20 into training and test sets, stratified by . |

| 2.2 Fix the random seed and record the split for reproducibility. |

| 3. Model and prior |

| 3.1 Specify the Cox model (1) with elastic–net prior (3). |

| 3.2 Use the normal–exponential mixture representation (4) and |

| Half-Cauchy hyperpriors for as in (5). |

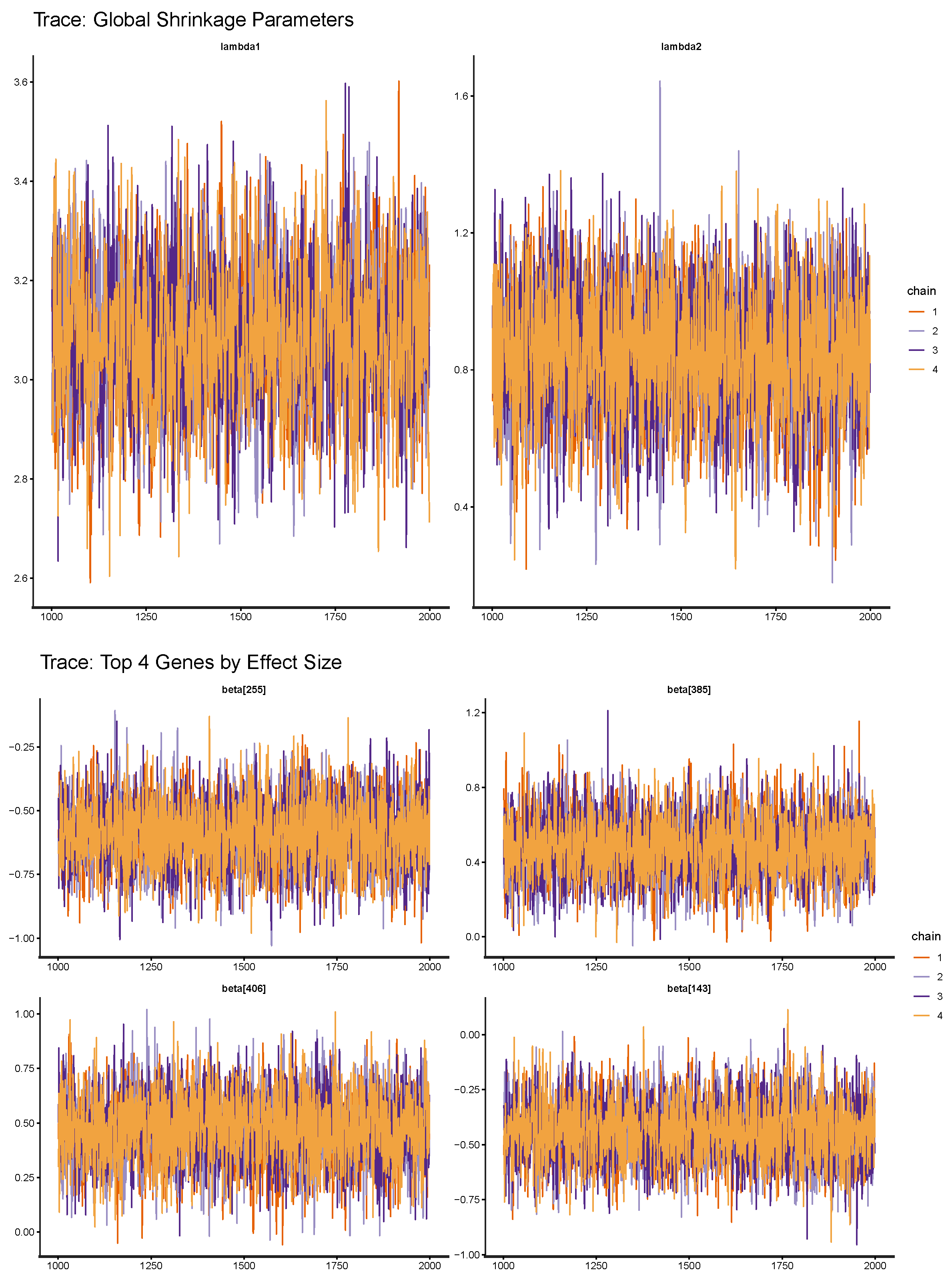

| 4. HMC sampling with Stan (training set only) |

| 4.1 Fit the model using 4 chains, warm-up + sampling. |

| 4.2 Check convergence: and ESS for all coefficients. |

| 4.3 Retain posterior draws and, for each draw, compute |

| the Breslow baseline cumulative hazard . |

| 5. Prediction on the test set |

| 5.1 For each test subject i and draw m, compute |

| linear predictor and |

| survival curve . |

| 5.2 Form posterior summaries (e.g., mean or median survival probabilities). |

| 6. Performance metrics (test set) |

| 6.1 Compute the integrated Brier score (IBS). |

| 6.2 Compute the concordance index (C-index) for discrimination. |

| 6.3 Compute calibration slope and intercept, following Demler et al. [15]. |

Integrated Brier Score:

Concordance (C) Index:

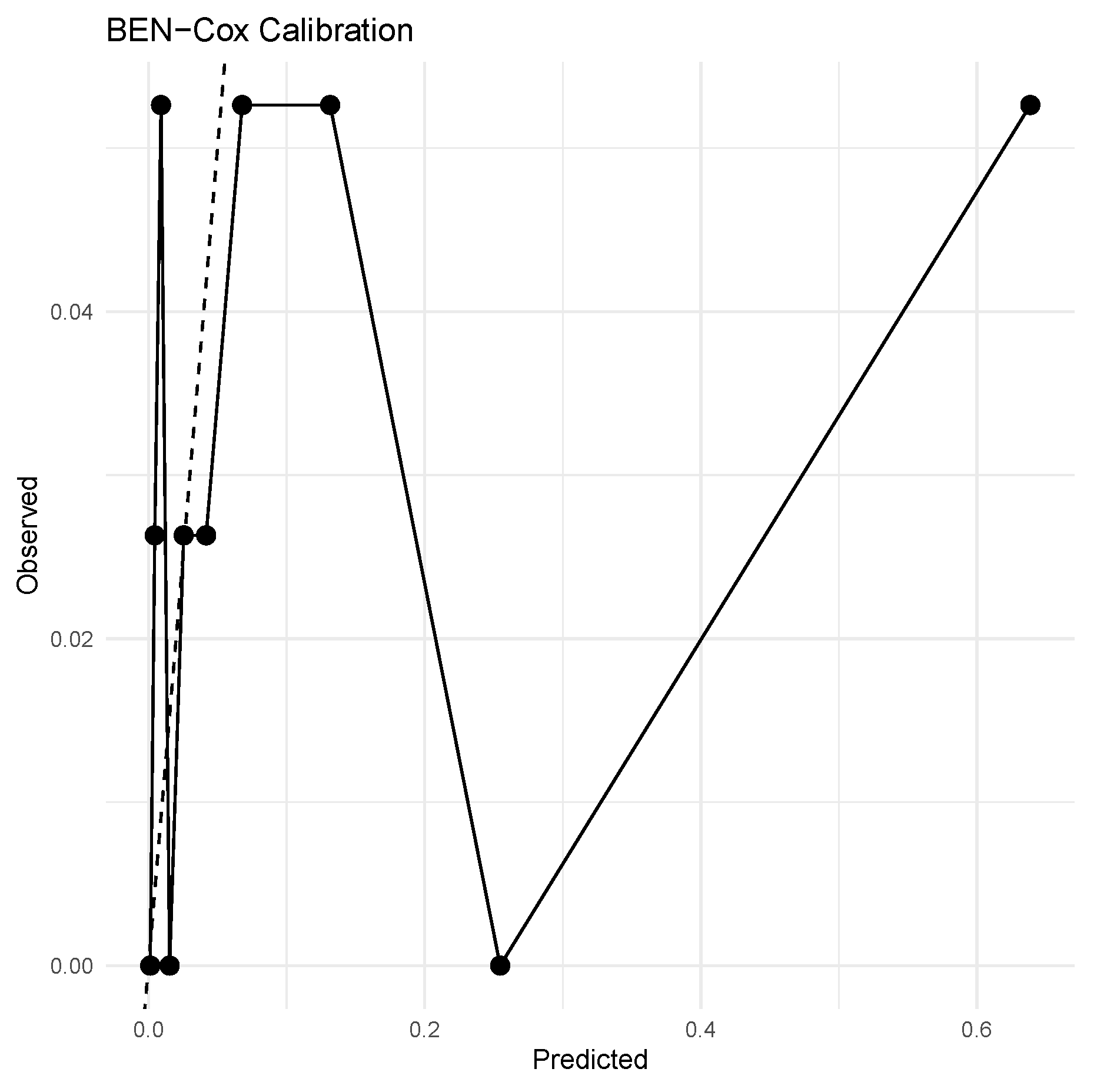

Grouped Calibration (GND ):

Calibration:

Bootstrap Uncertainty:

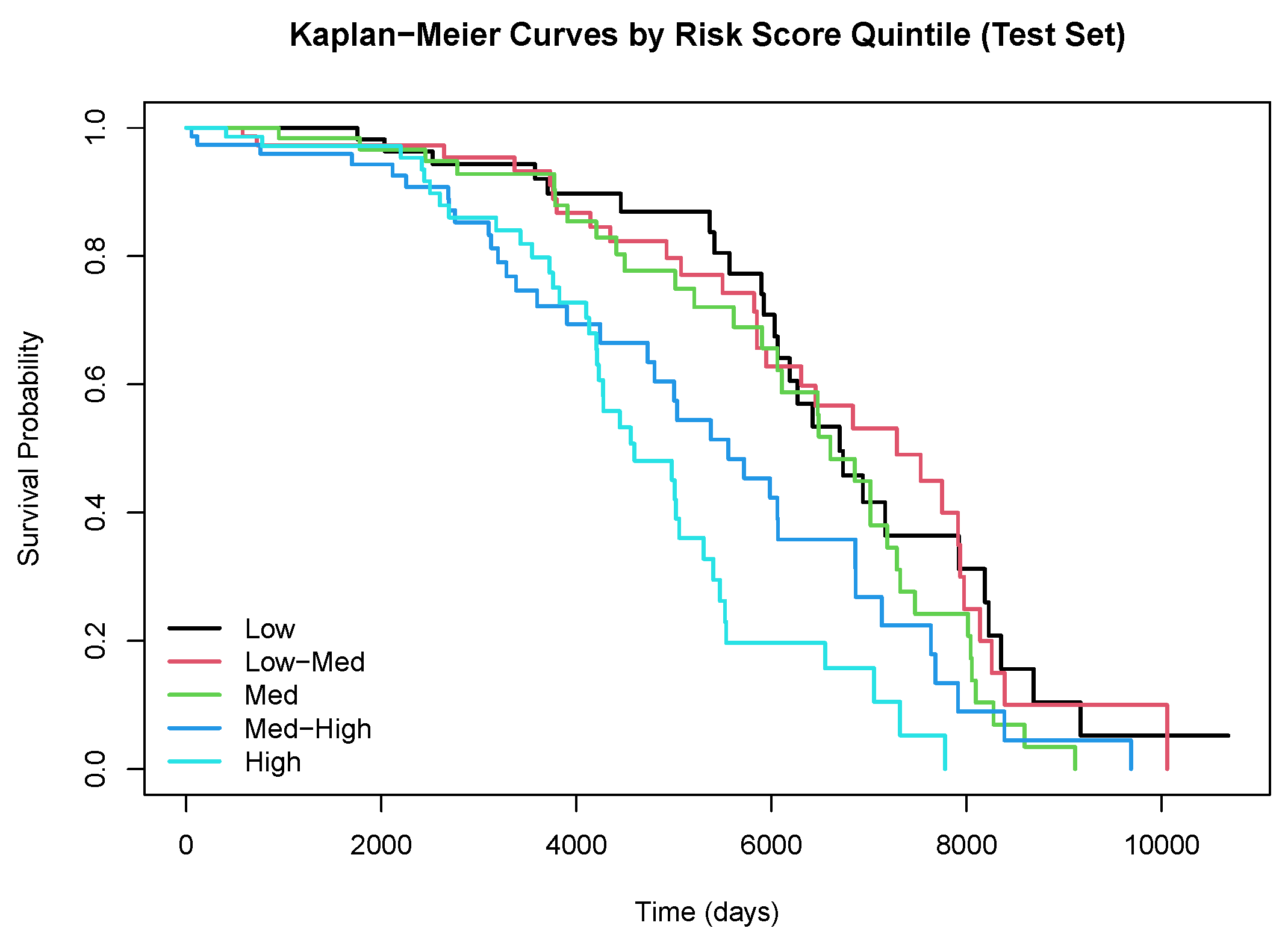

4.4. Results

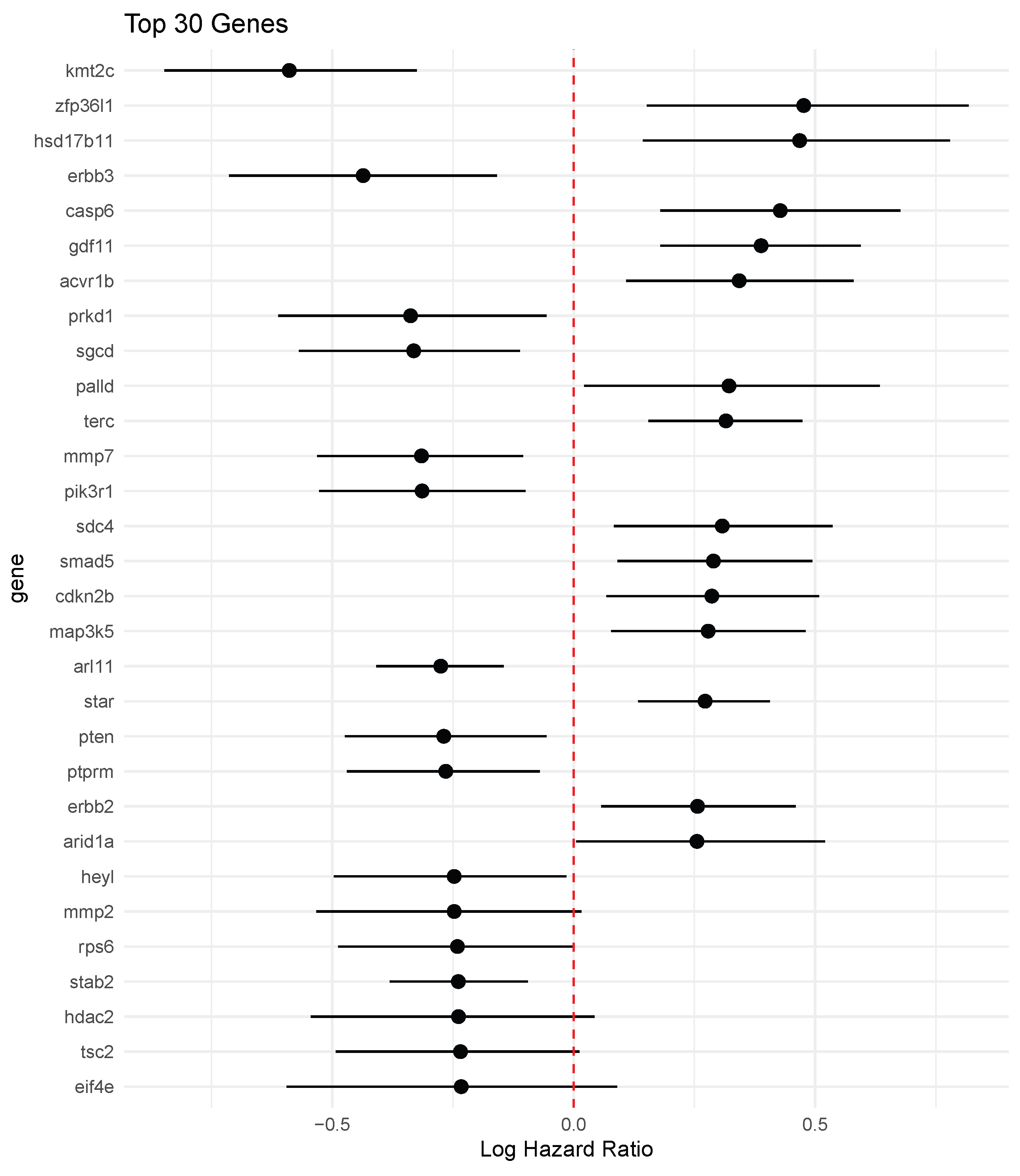

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

- BEN–Cox selects a small set of prognostic genes (48 in our analysis), with posterior credible intervals that help quantify the strength and direction of each effect, and it recovers biologically meaningful markers such as ERBB2.

- In terms of predictive performance, compared with a tuned ridge Cox model, BEN–Cox shows slightly better integrated Brier score, slightly higher C–index, and noticeably better global calibration as measured by the GND statistic, while both models clearly outperform the null Cox baseline.

- The Stan HMC implementation delivers full posterior distributions for regression coefficients and survival curves, offering coherent uncertainty quantification at both the gene and patient level.

- Despite the Bayesian formulation and MCMC, the complete pipeline (fitting, bootstrap evaluation, and plotting) remains computationally feasible on standard hardware for a cohort of this size.

- Here it can be said that the introduced theoretical results emphasize the theoretical contribution of the paper which is the Bayesian grouping property explains stable behavior under strong gene correlations, and the posterior contraction result provides an asymptotic guarantee that the BEN–Cox posterior concentrates around sparse truth at the usual high-dimensional rate in the Cox partial-likelihood setting.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Code availability

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 2

References

- Cox, D.R. Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 1972, 34, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.; Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for Cox’s proportional hazards model via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software 2011, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, D.M.; Tibshirani, R. Survival analysis with high-dimensional covariates. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 2010, 19, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Arabi Belaghi, R.; Hussein, A.A. Efficient post-shrinkage estimation strategies in high-dimensional Cox’s proportional hazards models. Entropy 2025, 27, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Ahmed, S.E.; Feng, Y. Post-selection shrinkage estimation for high-dimensional data analysis. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry 2017, 33, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Ahmed, S.E. Penalized and shrinkage estimation in the Cox proportional hazards model. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 2014, 43, 1026–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Hossain, S.; Doksum, K.A. LASSO and shrinkage estimation in Weibull censored regression models. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 2012, 142, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Ahmed, F.; Yüzbaşı, B. Post-shrinkage strategies in statistical and machine learning for high dimensional data; Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Casella, G. The Bayesian lasso. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2008, 103, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, N. The Bayesian elastic net. Bayesian Analysis 2010, 5, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, C. Elastic net regression modelling with the orthant normal prior. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2011, 106, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; van der Vaart, A.W. Convergence rates of posterior distributions for non-iid observations. The Annals of Statistics 2007, 35, 192–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Shah, S.P.; Chin, S.F.; Turashvili, G.; Rueda, O.M.; Dunning, M.J.; et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 2012, 486, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demler, O.V.; Paynter, N.P.; Cook, N.R. Tests of calibration and goodness-of-fit in the survival setting. Statistics in Medicine 2015, 34, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.D.; Gelman, A. The no-u-turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 1593–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, M. A conceptual introduction to Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.02434. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A. Prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models. Bayesian Analysis 2006, 1, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, N.E. Covariance analysis of censored survival data. Biometrics 1974, 30, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, B.; Chin, S.F.; Rueda, O.M.; et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refine their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discovery 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients (after QC) | 1903 |

| Number of events (deaths) | 800 (42.0%) |

| Median follow-up (years) | 16.4 |

| Gene-level features before filtering | 489 |

| Gene-level features after 10% variance filter | 440 |

| Training set size | 1522 subjects |

| Test set size | 381 subjects |

| Parameter | ESS | |

|---|---|---|

| Beta (median over coefficients) | 0.9997 | 4714 |

| Lambda1 | 1.0006 | 2288 |

| Lambda2 | 1.0008 | 4431 |

| Model | IBS ↓ | C-index ↑ | GND ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Cox | 0.222 ± 0.014 | 0.500 ± 0.000 | 04.5 ± 1.0 |

| Ridge Cox | 0.224 ± 0.013 | 0.647 ± 0.026 | 89.4 ± 38.8 |

| BEN Cox | 0.216 ± 0.013 | 0.655 ± 0.027 | 18.9 ± 4.1 |

| Model | Genes retained | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ridge Cox | 440 | 100.0 |

| BEN Cox | 48 | 33.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).