1. Introduction

Execution mistakes in paid social testing routinely erode validity: moving attribution windows, premature stopping, overlapping audiences, and noisy secondary metrics produce unstable conclusions and poor reproducibility.[

1] Popular guidance is either platform-agnostic (statistics-first) or overly tactical (platform tips). Few sources integrate

statistical discipline and operational guardrails into a single protocol tailored to Meta Ads.

Contribution. We design an integrated framework that (i) locks a single decision metric (CPA) and consistent attribution, (ii) enforces integrity gates (SRM, delivery/frequency balance, tracking QA), (iii) sizes tests to decision-relevant MDEs, and (iv) codifies guardrails linking statistical significance to unit economics. We then illustrate the framework via a calibrated simulation to show end-to-end analysis and decisions. This is a methods paper with a simulated proof-of-concept, not an empirical study.

2. Glossary and Notation

| Term |

Definition |

| CPA |

Cost per Acquisition: Spend/Purchases (reporting currency INR). Primary decision metric. |

| CVR |

Purchase conversion rate: Purchases/Link Clicks. Inference metric for two-proportion tests. |

| ROAS |

Return on Ad Spend: Revenue/Spend (platform-reported). Guardrail, not a decision metric. |

| SRM |

Sample Ratio Mismatch: statistically significant deviation from planned traffic split.[4] |

| CUPED |

Controlled-experiment Using Pre-Experiment Data; variance reduction using pre-period covariates.[6] |

| Attribution |

7-day click / 1-day view window, applied uniformly across arms for optimization and reporting.[7] |

| Guardrails G1–G5 |

G1: ROAS threshold; G2: delivery 45–55%; G3: frequency parity ; G4: web vitals (LCP < 2.5 s, CLS < 0.1, INP target);[8] G5: SRM pass (). |

3. Literature Review

Best practices emphasize prospective hypotheses, mutually exclusive randomization, fixed analysis plans, adequate power, and disciplined monitoring.[

1] Always-valid or sequential procedures control error when interim looks are unavoidable.[

2,

9] SRM tests detect allocation anomalies that can invalidate inference.[

4,

5] CUPED leverages pre-period covariates to reduce variance without changing the estimand.[

6]

Meta’s delivery system introduces complexities beyond generic web testing: attribution-window drift can rerank variants; audience overlap and learning-phase dynamics threaten balance; pacing and frequency caps constrain delivery; and platform-reported conversions may diverge from causal incrementality.[

7,

10,

11,

12] Practitioner guidance highlights creative modality, CTA framing, and audience quality as high-impact levers,[

13,

14] while landing performance (LCP, CLS, INP) shapes realized lift.[

8]

Existing work is either platform-agnostic (statistics-first) or narrowly tactical. We operationalize established statistical methods (power/MDE, SRM, CUPED, multiplicity control[

15,

16]) into a protocol aligned with Meta’s split-testing mechanics[

10] and tie decisions to unit economics via guardrails—offering a reproducible template practitioners can adopt without advanced statistical tooling.

4. Framework Development

4.1. Design Principles

Each test isolates

one lever—

creative, copy/CTA, audience, or placement—while mirroring budgets, schedules, placements, and audiences to preserve interpretability.[

1] Allocation uses Meta split-tests with mutually exclusive arms (e.g., 50/50) and mirrored pacing to target balanced delivery.[

10] We predefine the decision metric (CPA), secondary diagnostics (CVR, CTR, CPC, ROAS), and a single attribution window applied uniformly across arms (7C/1V) to prevent window-induced reversals.[

7]

4.2. Measurement Plan

Primary. (INR).

Secondary. Purchase CVR, CTR, CPC, ROAS.

Guardrails (G1–G5). (

G1) ROAS threshold; (

G2) delivery 45–55%; (

G3) frequency parity

; (

G4) web vitals within targets; (

G5) SRM pass at

.[

4,

8]

Denominator standard. We compute CVR on link-click denominators to stabilize variance; CPA remains the decision variable.

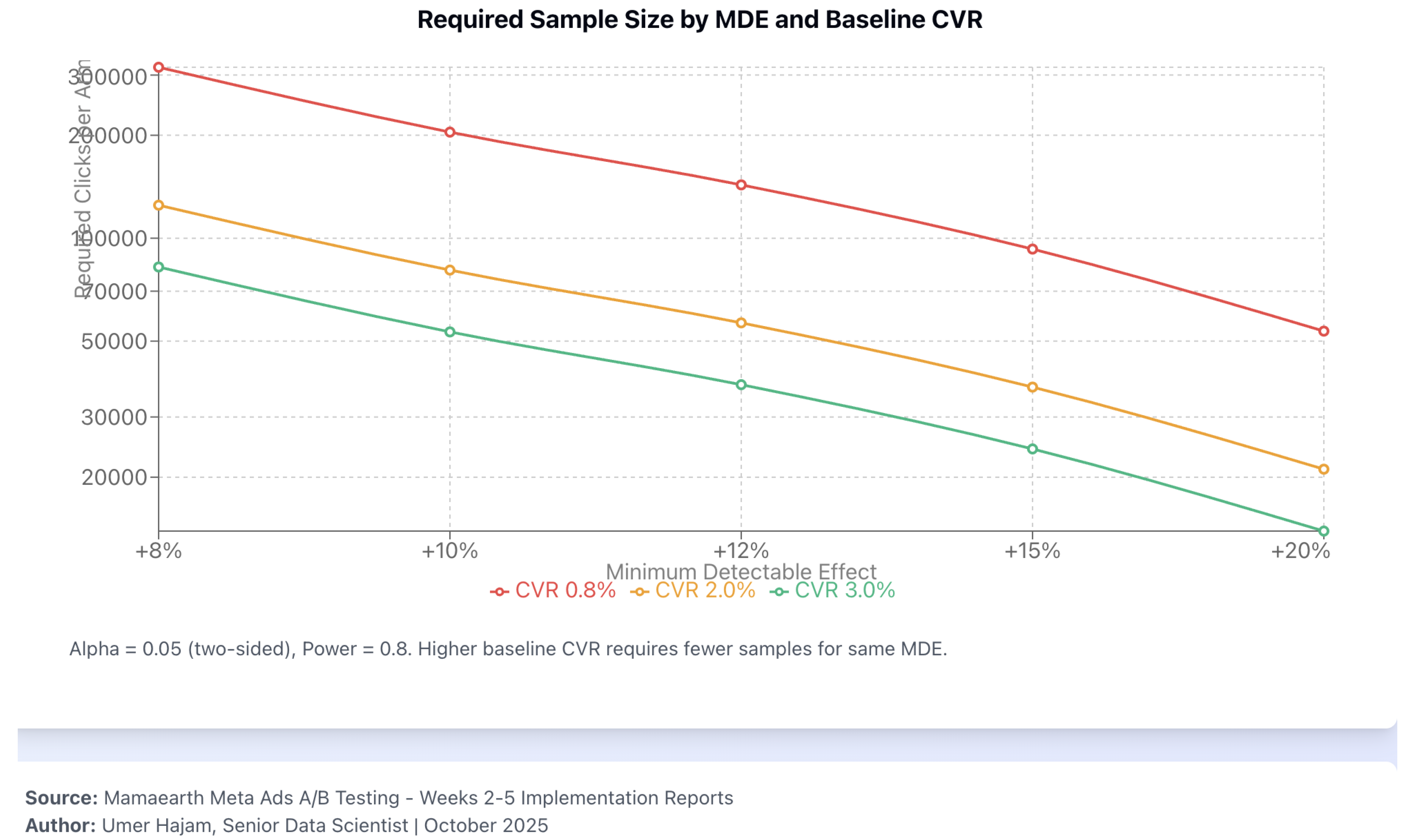

4.3. Power, Sample Size, and MDE

We determine sample size on the CVR scale via a two-proportion test with pooled standard error under

and Wilson intervals for single-arm coverage.[

17,

18] Let

be baseline CVR and

the alternative (relative MDE

). For two-sided size

and power

,

Figure 1.

Required clicks per arm vs. minimum detectable effect (MDE) and baseline CVR (, two-sided; power ). Simulated illustration; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

Figure 1.

Required clicks per arm vs. minimum detectable effect (MDE) and baseline CVR (, two-sided; power ). Simulated illustration; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

4.4. Integrity Diagnostics

SRM. Pearson’s

with

;

flags SRM and pauses inference until remediation.[

4,

5,

19]

Delivery/frequency. Monitor arm delivery share and frequency deltas; investigate deviations.

Tracking. Pixel+Conversions API dedup via shared

event_id; validate

Purchase.value/

currency=INR; GA4 UTM parameters ensure traceability.[

20,

21,

22,

23]

4.5. Variance Reduction (CUPED)

When stable pre-period covariates exist, compute

with

; report raw and adjusted estimates without changing the estimand.[

6]

4.6. Statistical Analysis and Decision Rule

Primary test. Two-proportion z-test on purchase CVR at preregistered ; report absolute/relative effects and CIs.

Decision. Decisions are made on CPA. Promotion requires: (i) CVR lift (or preregistered non-inferiority), (ii) CPA improvement consistent with the CVR/CPC profile, and (iii) guardrails satisfied.

Multiplicity/monitoring. When interim looks are necessary, use Pocock-style equal alpha spending;[

9] for multiple tests, control FWER/FDR via Holm–Bonferroni or Benjamini–Hochberg.[

15,

16]

5. Simulation Study (Illustrative, Not Empirical)

Provenance. All scenarios use simulated data calibrated to D2C beauty benchmarks; no live traffic is analyzed. The goal is to demonstrate the workflow and decision logic, not to claim real-world effects. We deliberately use modal verbs (“would”) and repeated reminders of simulation.

5.1. Overview and Uncertainty

Across seven simulated A/B tests, three scenarios

would meet significance on CVR and align economically on CPA/ROAS; one

would be harmful; three are inconclusive at

. We report

z statistics, exact

p-values, and 95% CIs for absolute CVR differences under

Section 4.6.

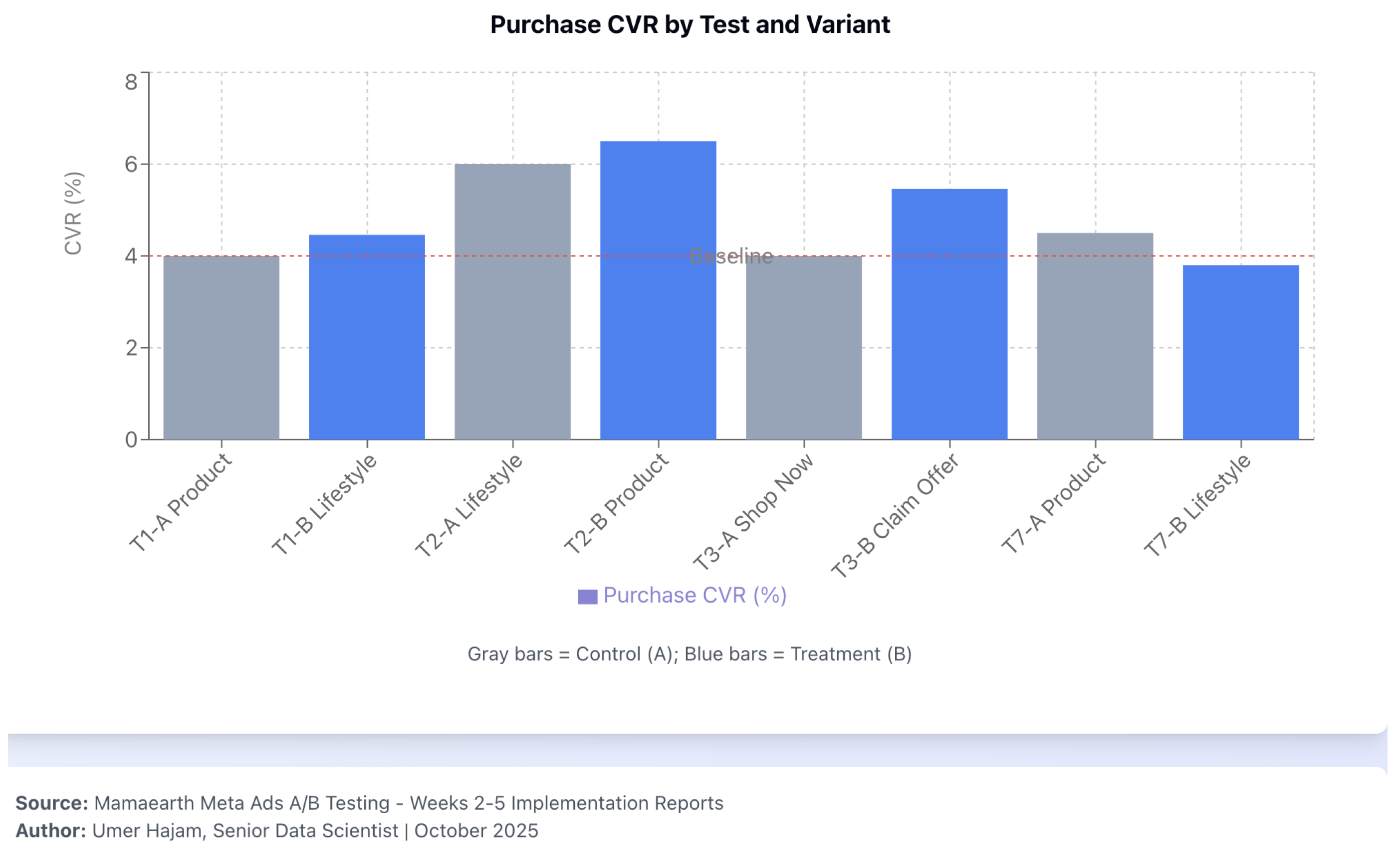

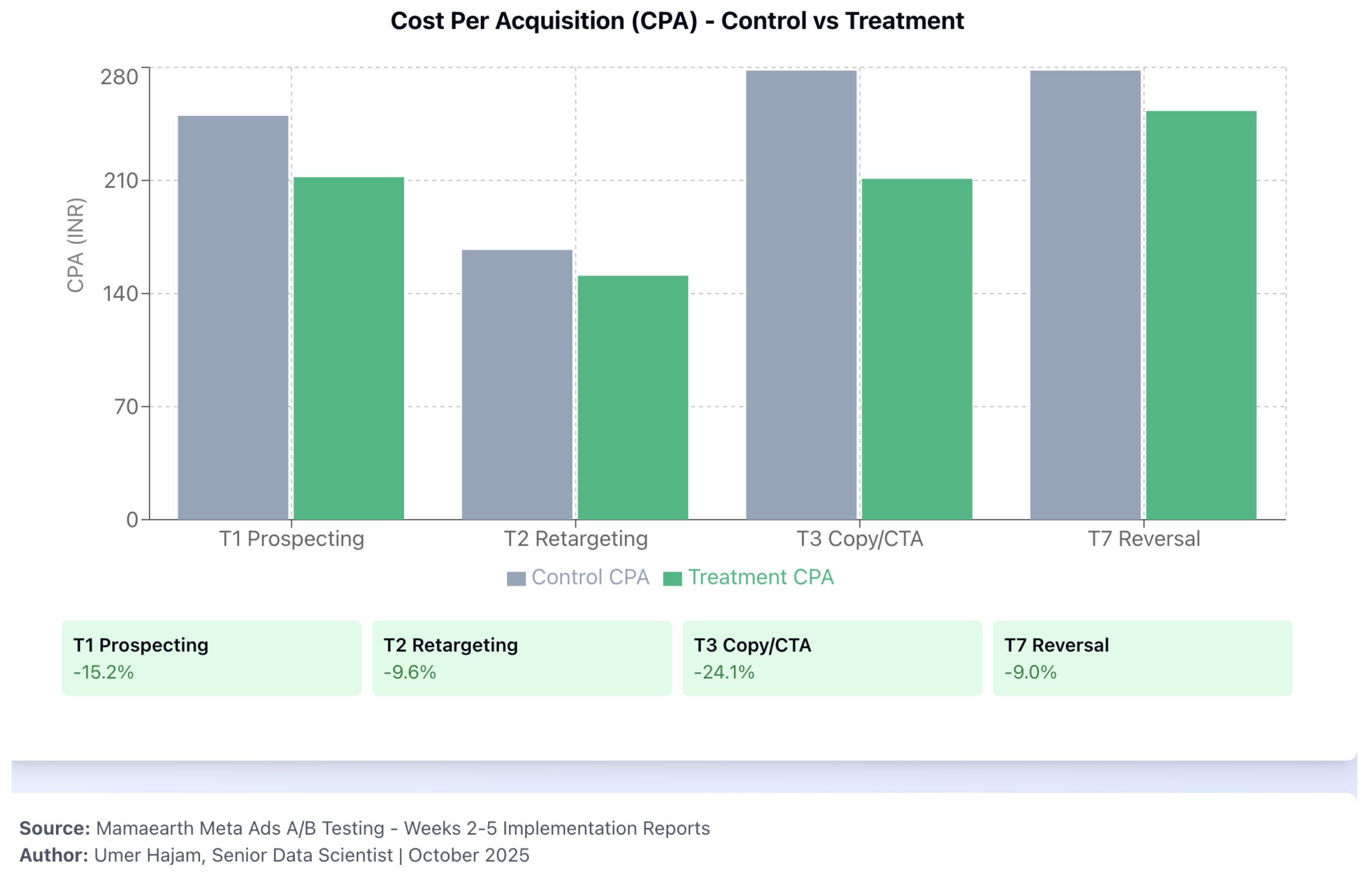

T1 (Prospecting creative). Simulated CVR difference pp (4.46% vs. 4.00%; , ; 95% CI pp) illustrates a promote decision on lower CPA (INR 212 vs. INR 250; ) assuming G1–G5 hold.

T2 (Retargeting creative). Borderline CVR lift ( pp; , ) but higher CPA for lifestyle (INR 167); retain product on the CPA rule.

T3 (Copy/CTA). Claim Offer simulated CVR lift pp () with CPA improvement () → promote.

T4–T6. Inconclusive at ; resize or extend duration.

T7 (Retargeting reverse). Harmful CVR ( pp; ) → reject, regardless of nominal CPA decrease.

Figure 2.

Purchase CVR by test and variant (control vs. treatment). Simulated data; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

Figure 2.

Purchase CVR by test and variant (control vs. treatment). Simulated data; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

Figure 3.

CPA comparison (control vs. treatment) across tests. Simulated data; primary decision metric is CPA.

Figure 3.

CPA comparison (control vs. treatment) across tests. Simulated data; primary decision metric is CPA.

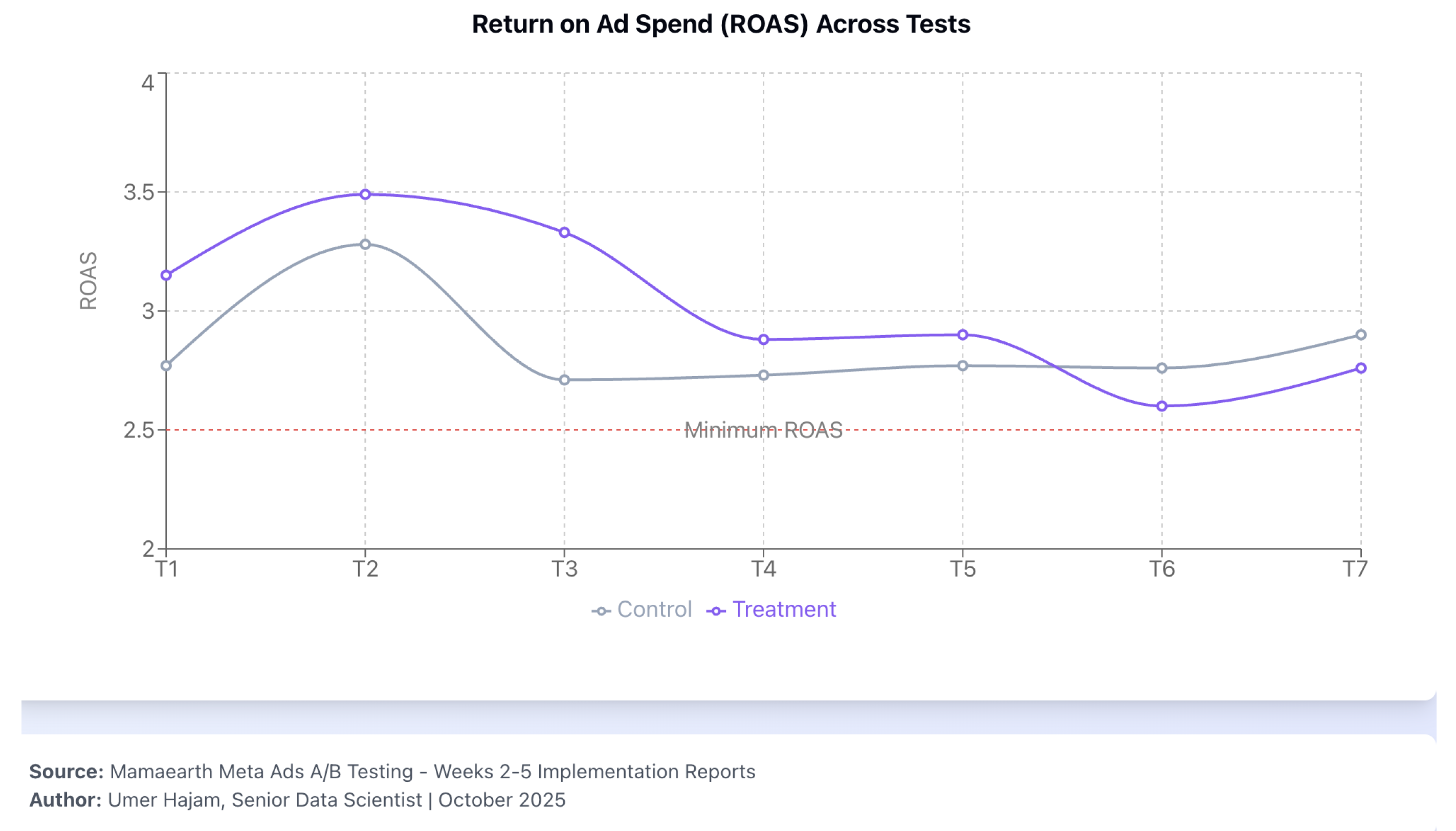

Figure 4.

ROAS across all tests with minimum-threshold reference line. Simulated data; guardrail G1 requires meeting or exceeding the reference line.

Figure 4.

ROAS across all tests with minimum-threshold reference line. Simulated data; guardrail G1 requires meeting or exceeding the reference line.

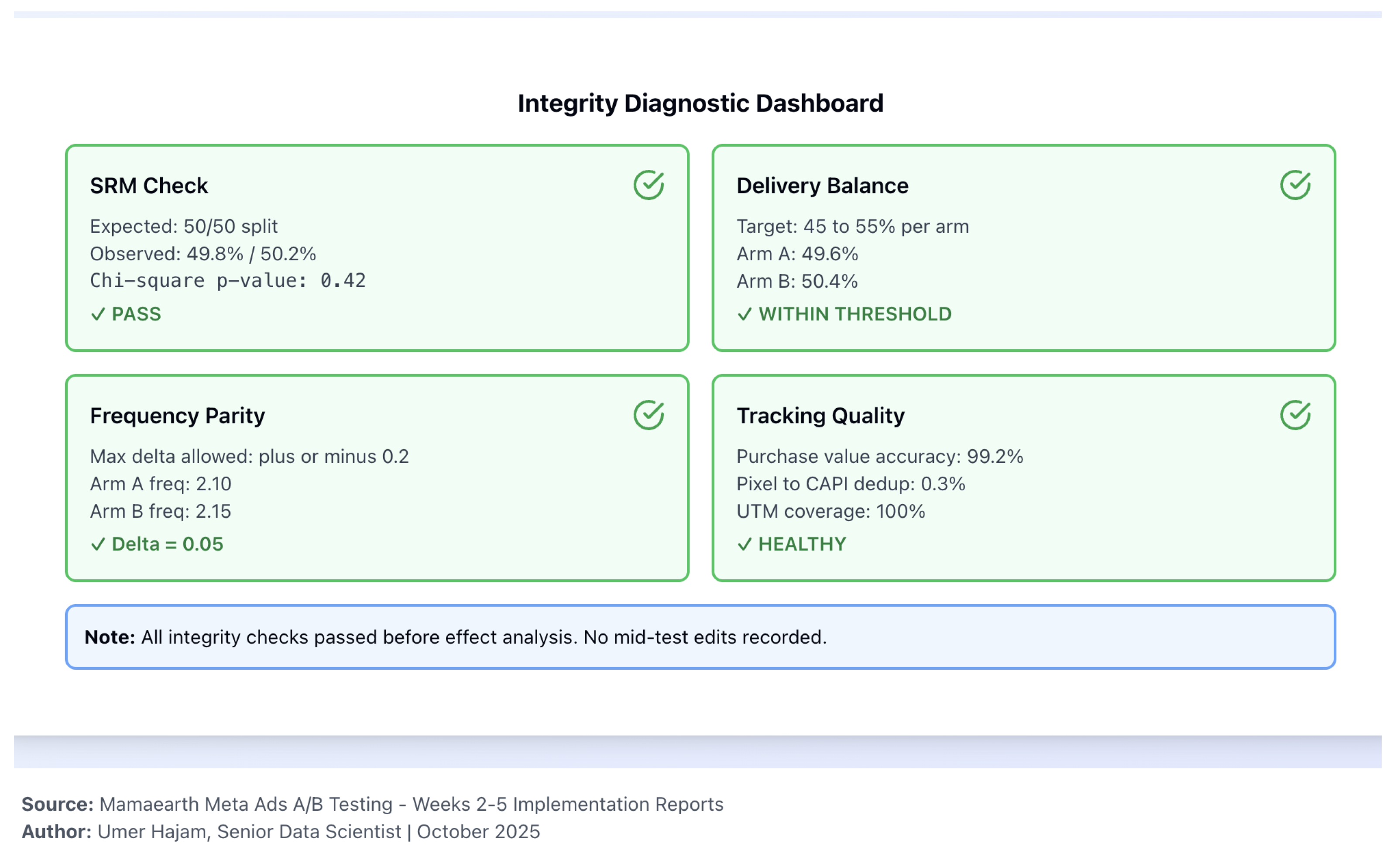

5.2. Diagnostics and Integrity

Effect computation follows integrity gates. In T1, SRM (pass); delivery 49.8%/50.2%; frequency . No mid-test edits in the incident log. Attribution windows are constant across arms; all amounts in INR.

Figure 5.

Integrity dashboard (T1 example). Simulated data: SRM () ; delivery 49.8%/50.2%; frequency ; tracking QA nominal.

Figure 5.

Integrity dashboard (T1 example). Simulated data: SRM () ; delivery 49.8%/50.2%; frequency ; tracking QA nominal.

5.3. Promotion Decisions (Hypothetical)

Under

Section 4.6 and G1–G5, the framework

would promote lifestyle for prospecting (T1) and

Claim Offer (T3); retain product for retargeting (T2) on CPA; reject the harmful variant in T7; and defer T4–T6.

Table 2.

Summary of simulated A/B outcomes (CVR, uncertainty, economics, and hypothetical decisions). Simulated data. CVR diffs are absolute %-point differences; CPA are arm means.

Table 2.

Summary of simulated A/B outcomes (CVR, uncertainty, economics, and hypothetical decisions). Simulated data. CVR diffs are absolute %-point differences; CPA are arm means.

| Test |

Lever |

CVR A |

CVR B |

|

z |

p |

CPA A |

CPA B |

Hypothetical decision & rationale |

| T1 |

Prospecting creative |

4.00% |

4.46% |

+0.46 pp |

2.62 |

0.009 |

INR 250 |

INR 212 |

Promote B (lifestyle); CVR↑, CPA , ROAS guardrail met |

| T2 |

Retargeting creative |

6.00% |

6.50% |

+0.50 pp |

1.97 |

0.049 |

INR 151 |

INR 167 |

Retain A (product); decision on CPA; A cheaper despite CVR favoring B |

| T3 |

Copy/CTA |

4.00% |

5.46% |

+1.46 pp |

6.92 |

|

INR 278 |

INR 211 |

Promote B (Claim Offer); large CVR↑, CPA

|

| T4 |

Placement/format |

4.00% |

4.27% |

+0.27 pp |

1.31 |

0.19 |

INR 278 |

INR 252 |

Inconclusive; continue or resize |

| T5 |

Message match |

4.00% |

4.00% |

+0.00 pp |

0.00 |

1.00 |

INR 227 |

INR 250 |

Inconclusive; no CVR signal |

| T6 |

Audience breadth |

4.00% |

4.20% |

+0.20 pp |

1.05 |

0.29 |

INR 250 |

INR 264 |

Inconclusive; widen sample or refine segments |

| T7 |

Retargeting (reverse) |

4.50% |

3.80% |

pp

|

|

|

INR 278 |

INR 253 |

Reject B (harmful CVR); do not promote despite nominal CPA drop |

6. Implementation Guide (Practitioner-Oriented)

6.1. Pre-Launch Checklist

Before activating any test, verify:

Hypothesis preregistered (factor, direction, MDE, guardrails, decision rule).

Sample-size calculation completed; duration ≥ 7 days (covers weekly cyclicality).

Pixel + CAPI events validated; shared

event_id deduplication confirmed.[

20,

21]

Landing-page parity checked (headline, hero, CTA alignment); web vitals targets met.[

8]

Audience exclusions applied; no overlap between arms; learning-phase expectations documented.[

10]

Attribution window locked at 7C/1V across arms for both optimization and reporting.[

7]

Incident-log template prepared (settings snapshot, timestamps, remediation path).

6.2. Daily Monitoring Dashboard

Track the following to catch issues early:

SRM watch: Cumulative

every day; flag if

(investigate),

(pause).[

4]

Delivery balance: Arm A impressions/(A+B); target 45–55%.

Frequency gap:.

Learning phase: Flag if either arm exits learning before fixed horizon.

Tracking health: Purchases (Pixel+CAPI) vs. GA4; reconcile daily.[

22,

23]

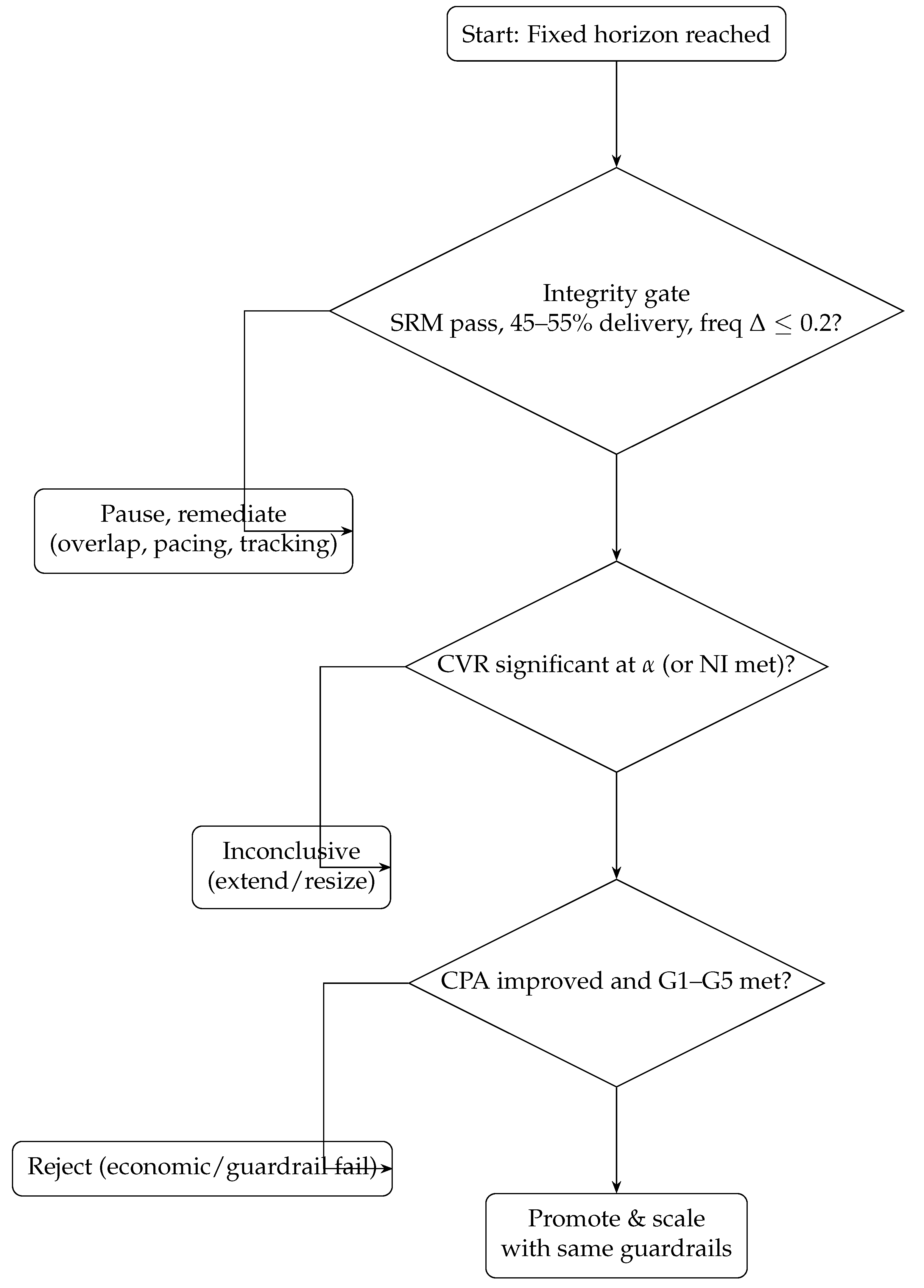

6.3. Decision Flowchart

Figure 6.

Promotion decision flow. Simulated framework logic; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

Figure 6.

Promotion decision flow. Simulated framework logic; decision metric: CPA; inference metric: CVR; guardrails G1–G5 apply.

6.4. Example Pre-Registration Template

| Field |

Entry (example) |

| Test ID |

T1_Prospecting_Creative_Nov2025 |

| Hypothesis |

Lifestyle video increases CVR by ≥12% (relative) vs. product creative |

| Primary metric |

CPA (INR); decision variable |

| Inference metric |

Purchase CVR (Purchases/Link Clicks) |

| Attribution |

7-day click / 1-day view (fixed across arms) |

| Guardrails |

G1: ROAS; G2: delivery 45–55%; G3: freq ; G4: LCP < 2.5 s, CLS < 0.1; G5: SRM pass |

| MDE (relative) |

12% (prospecting), 8% (retargeting) |

| Sample/arm |

114,327 clicks (from power curve at baseline CVR 1.0%, MDE 12%) |

| Duration |

10 days (covers weekdays/weekend) |

| Stop rule |

Fixed horizon; no interim peeking (Pocock spending if forced) |

| Multiplicity |

Holm–Bonferroni across concurrent tests; report BH-FDR as sensitivity |

| Incident protocol |

Snapshot settings; pause on SRM/delivery imbalance; relaunch with fresh ID |

7. Discussion

A coherent, reproducible framework that integrates rigorous experimental design with business guardrails for Meta Ads, plus a simulated end-to-end demonstration of analysis and decisions.

We do not assert real-world effectiveness of any creative, copy, audience, or placement; simulation cannot validate causal ordering nor guarantee profitability.

(1) A single decision metric (CPA) tied to guardrails prevents “wins” that harm economics; (2) integrity checks (SRM, delivery/frequency, tracking QA) reduce false signals; (3) power/MDE planning aligns sample with decision intent; (4) CUPED offers sensitivity gains without changing the estimand.

(1)

Creative fatigue: short-run tests may not predict long-run decay; rotation cadences are required. (2)

Incrementality: platform conversions may capture demand rather than create it; geo-experiments or conversion-lift tests complement this framework.[

11,

12] (3)

Seasonality: effects vary across peak periods; cadence-based revalidation is essential. (4)

Cross-platform spillover: conversions may attribute to search while exposure occurred on Meta.

Validate the framework in production with staged rollouts; measure decision velocity (time-to-promotion) and outcome quality (post-scale CPA/ROASstability) vs. baseline; expand to contribution-margin guardrails and multi-platform settings.

8. Conclusion

We present a methodological framework for decision-grade experimentation on Meta Ads that combines statistical discipline (CPAas decision metric; consistent attribution; power/MDE; SRM; optional CUPED) with business guardrails (ROAS, delivery balance, frequency parity, landing health). A calibrated simulation shows how the framework would operate end-to-end. Practitioners should adapt and validate the template with live traffic before drawing substantive conclusions.

Data & Code Availability

Synthetic dataset and analysis scripts will be provided as supplementary materials; no real-world data were used.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Evidence-Pack Checklist (Simulated)

SRM & Delivery. SRM p-values; arm shares; frequency deltas.

Attribution. 7C/1V, uniform across arms.

Windows. Concurrent runtime; no mid-test edits.

Artifacts. Synthetic dataset + seeded notebook for reproduction.

Captions. Every figure/table labeled “Simulated data” when applicable.

Appendix B. Simulation Data Generation (Pseudocode)

seed = 42

for test in T1..T7:

set baseline_cvr by context (prospecting=0.040, retargeting=0.060)

set rel_effect per scenario (e.g., T1 +11.5%, T3 +36.5%, T7 -15.6%)

draw clicks per arm from planned sample size with small Poisson jitter

purchases_A ~ Binomial(clicks_A, baseline_cvr)

purchases_B ~ Binomial(clicks_B, baseline_cvr * (1 + rel_effect))

spend_A, spend_B calibrated to produce target CPA and ROAS distributions

compute metrics, SRM chi-square, integrity flags

Appendix C. Roles and Responsibilities (RACI Snapshot)

| Activity |

Data Science |

Media Buyer |

Engineering/Analytics |

Product/GM |

| Hypothesis & preregistration |

R |

C |

C |

A |

| Sample sizing & MDE |

R |

C |

C |

I |

| Split-test setup (Meta) |

C |

R |

C |

I |

| Tracking QA (Pixel+CAPI, GA4) |

C |

C |

R |

I |

| Monitoring (SRM, delivery) |

R |

R |

C |

I |

| Decision & rollout |

C |

R |

C |

A |

| Incident handling |

R |

R |

R |

I |

References

- Kohavi, R.; Tang, D.; Xu, Y. Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments: A Practical Guide to A/B Testing; Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Johari, R.; Pekelis, L.; Walsh, D. Always Valid Inference: Bringing Sequential Analysis to A/B Testing, 2017, [arXiv:stat.ME/1512.04922].

- Bakshy, E.; Eckles, D.; Bernstein, M.S. Designing and Deploying Online Field Experiments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web, 2014.

- Miller, E. Seven Pitfalls to Avoid in A/B Testing, 2015. Includes Sample Ratio Mismatch (SRM) diagnostics.

- Vermeer, L. Sample Ratio Mismatch: Why and How to Detect It. https://lukasz.cepowski.com/srm, 2019. Blog post.

- Deng, A.; Xu, Y.; Kohavi, R.; Walker, T. Improving the Sensitivity of Online Controlled Experiments by Utilizing Pre-Experiment Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2013, pp. 1239–1247. [CrossRef]

- Meta. About Attribution in Meta Ads Reporting, 2025. Accessed 1 Nov 2025.

- Google. Web Vitals, 2025. Accessed 1 Nov 2025.

- Pocock, S.J. Group Sequential Methods in the Design and Analysis of Clinical Trials. Biometrika 1977, 64, 191–199.

- Meta. A/B Tests and Experiments on Meta Ads, 2025. Accessed 1 Nov 2025.

- Gordon, B.R.; Zettelmeyer, F.; Bhargava, N.; Chapsky, D. A Comparison of Approaches to Advertising Measurement: Evidence from Big Field Experiments at Facebook. Marketing Science 2019, 38, 193–225.

- Lewis, R.A.; Rao, J.M. The Unfavorable Economics of Measuring the Returns to Advertising. Quarterly Journal of Economics 2015, 130, 1941–1973.

- Meta. Creative Best Practices for Mobile and Feed Environments, 2025. Accessed 1 Nov 2025.

- Meta. About Lookalike Audiences, 2025. Accessed 1 Nov 2025.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B 1995, 57, 289–300.

- Holm, S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1979, 6, 65–70.

- NIST/SEMATECH e-Handbook of Statistical Methods: Two-Proportion Tests. https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/prc/section3/prc33.htm. Accessed 2025-10-15.

- Brown, L.D.; Cai, T.T.; DasGupta, A. Interval Estimation for a Binomial Proportion. Statistical Science 2001, 16, 101–133.

- Analytics-Toolkit.com. Sample Ratio Mismatch (SRM) in A/B Testing. https://blog.analytics-toolkit.com/, 2019.

- Meta Developers. Deduplicate Pixel and Conversions API Events. https://developers.facebook.com/docs/marketing-api/conversions-api/deduplicate-pixel-and-server-events/, 2025. Accessed 2025-10-15.

- Meta Business Help Center. About Deduplication for Pixel and Conversions API. https://www.facebook.com/business/help/823677331451951, 2025. Accessed 2025-10-15.

- Google Support. GA4 URL Builders (UTM Parameters). https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/10917952, 2025. Accessed 2025-10-15.

- Fedorovicius, J. Guide to UTM Parameters in Google Analytics 4. https://www.analyticsmania.com/post/utm-parameters-in-google-analytics-4/, 2025. Accessed 2025-10-15.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).