1. Introduction

1.1. The Scaling Problem in AI Infrastructure

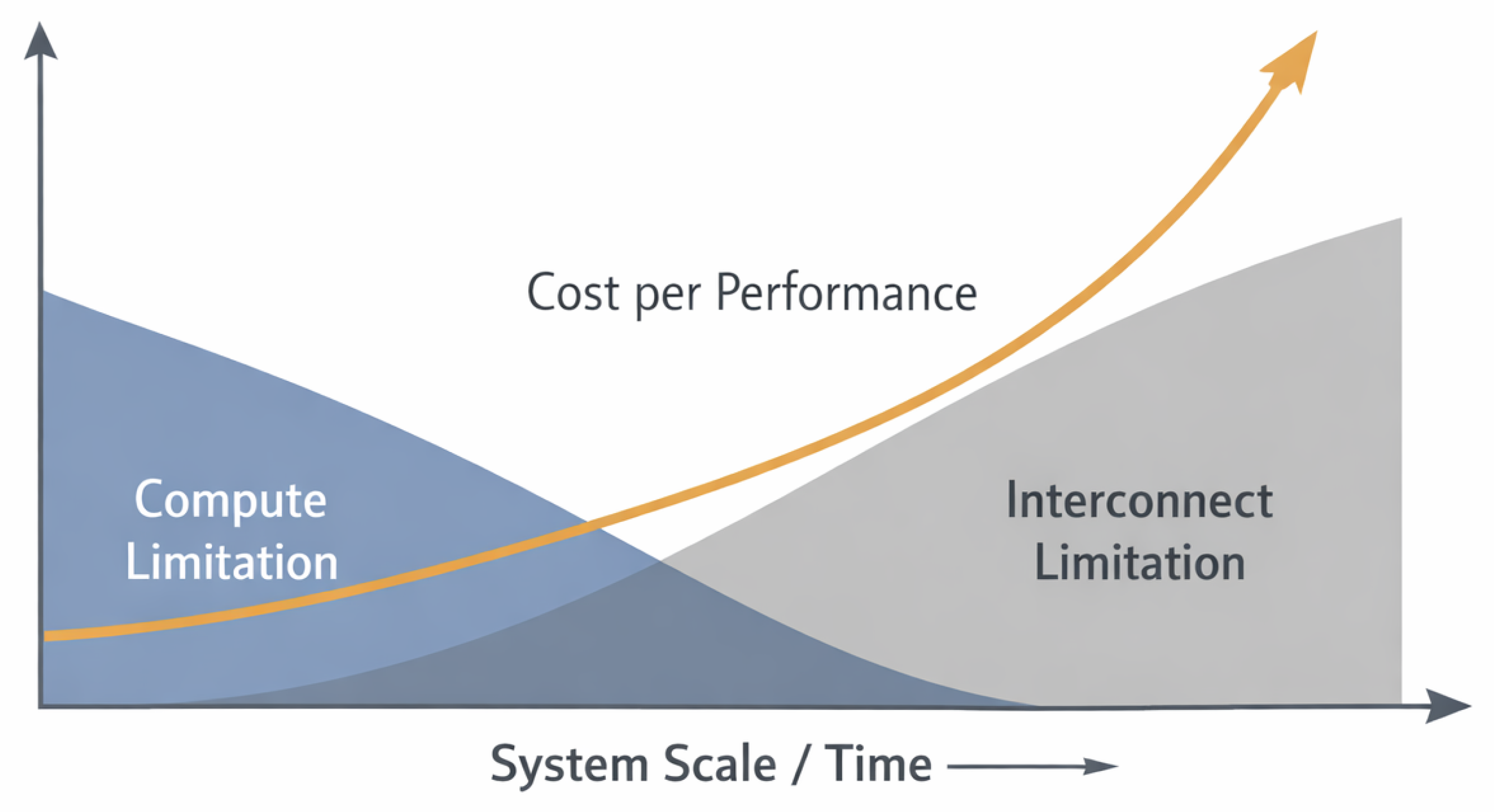

Over the past decade, the scaling of AI and HPC infrastructures has been driven primarily by increases in raw compute capacity, accelerator density, and parallelism. This strategy has delivered substantial gains in peak throughput, yet it has also revealed a growing discrepancy between nominal performance and economically effective performance. In large-scale deployments, costs increasingly grow faster than usable performance, even as additional hardware is provisioned.

A key reason for this divergence lies in the changing nature of the dominant bottleneck. In contemporary AI workloads, especially large-scale training and latency-sensitive inference, critical operations such as gradient synchronization, pipeline parallelism, and multi-accelerator coordination are no longer local to individual devices. Instead, they depend fundamentally on the behavior of interconnects that couple distributed components into a single execution fabric [

4,

5]. As system scale and heterogeneity increase, these interconnect-dependent operations become a primary determinant of end-to-end efficiency.

Importantly, many of the costs incurred in such systems do not arise within individual compute operations, but in the coordination between them. Latency accumulation, synchronization delays, and non-uniform progress across nodes introduce hidden overheads that are not adequately captured by classical metrics such as FLOPS, link bandwidth, or average latency. As a result, additional hardware investment can yield diminishing or even negative returns in terms of cost per performance, a phenomenon that is increasingly reported in large production environments [

22,

23].

This shift from compute-bound to interconnect-bound behavior motivates a re-examination of how scalability is conceptualized and evaluated in AI infrastructure. The perspective adopted in this work is consistent with prior operator-oriented frameworks for runtime structural diagnostics, including SORT-AI and related work [

1], which emphasize structural dependencies over isolated component metrics.

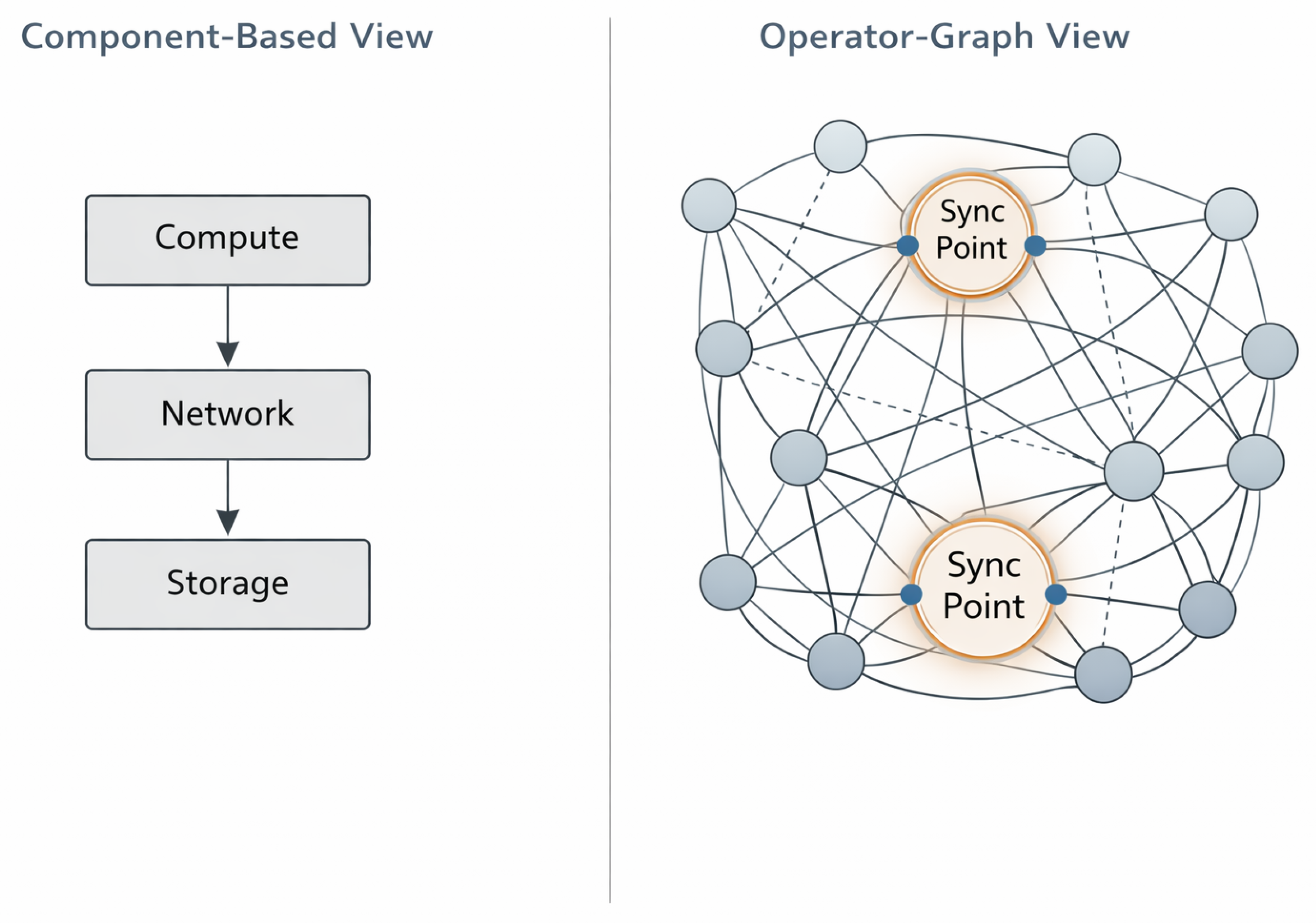

Figure 1 illustrates this transition schematically.

1.2. Scope and Limitations

The purpose of this article is to provide a structural problem analysis of interconnect-induced instability in large-scale AI and HPC systems. The focus is explicitly on problem formulation and conceptual clarification, rather than on proposing concrete solutions or implementations.

Accordingly, this work does not introduce algorithms, code, schedulers, or control mechanisms. It makes no vendor-specific assumptions and does not analyze particular hardware products, network technologies, or software stacks. The discussion remains agnostic with respect to implementation choices and avoids prescriptive architectural recommendations.

The goal of this scoped approach is to isolate the structural mechanisms by which interconnect dynamics give rise to economic inefficiencies at scale. By doing so, the article aims to establish a shared analytical vocabulary that can support informed discussion and subsequent investigation, without constraining design space or implying specific solutions.

1.3. System Class and Failure Envelope

The scaling pathologies discussed in this article are not confined to a single application or deployment model. Instead, they recur across a recognizable class of systems characterized by tight coupling, high concurrency, and strong synchronization requirements. These system classes include large-scale AI training workloads such as foundation models [

20], inference pipelines operating under strict service-level agreements, heterogeneous accelerator fabrics combining GPUs, TPUs, or custom ASICs [

21], power- and cost-constrained HPC environments, and government or defense cloud infrastructures with stringent reliability and audit requirements.

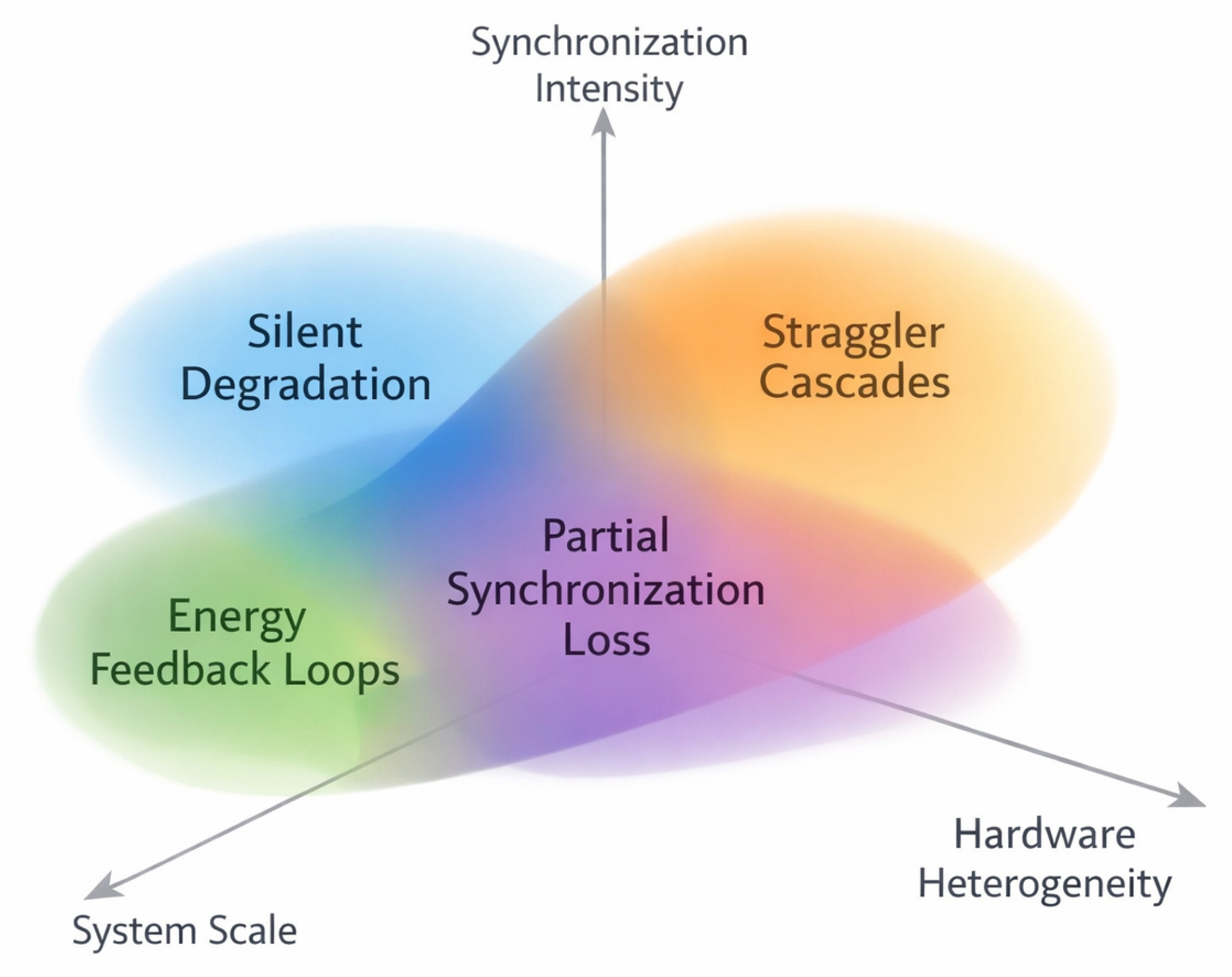

Within this system class, failures rarely manifest as immediate or catastrophic faults. Rather, they occupy a characteristic failure envelope dominated by gradual and often opaque effects. Common modes include silent degradation, in which efficiency declines without triggering explicit errors; straggler cascades, where a small number of slow nodes delay global synchronization [

8]; partial synchronization loss, resulting in drift between subsets of nodes; tail latency inflation, producing unpredictable delays at high percentiles [

4]; and energy feedback loops, where load oscillations interact with cooling and power management to amplify instability.

Figure 2 depicts this failure envelope schematically.

These failure modes give rise to observable symptoms that are familiar to practitioners but difficult to diagnose. Jobs may take significantly longer than expected without a clear error condition. Re-runs accumulate despite the absence of reproducible bugs. Cluster utilization decreases even when resources are fully allocated, and energy consumption rises disproportionately relative to delivered computational work. Together, these symptoms define a recurring risk profile that allows system operators and architects to assess whether their deployments fall within the class of concern addressed in this work.

By formalizing this system class and its associated failure envelope, the analysis in this article provides a diagnostic lens rather than a remedy. This framing is intended to support recognition and discussion of structural instability effects, setting the stage for the more detailed examination of metrics, economic consequences, and structural perspectives developed in subsequent sections (see

Section 3 and

Section 5).

2. The Shift from Compute to Interconnect

2.1. Traditional Optimization Assumptions

Historically, the optimization of AI and HPC systems has been dominated by a compute-centric perspective. Performance improvements have primarily been sought through advances in accelerator hardware, compiler technology, and kernel-level optimization [

18,

19]. This approach has been highly successful in increasing peak throughput and reducing time-to-solution for isolated workloads, and it remains a necessary foundation for efficient system design.

Within this traditional paradigm, interconnects are implicitly treated as passive infrastructure components. Networks are assumed to provide sufficient bandwidth and acceptable latency, while their behavior is largely abstracted away from the core performance model. As a consequence, optimization efforts typically decouple compute and communication concerns, analyzing them through separate metrics and tooling. FLOPS, utilization, and kernel efficiency are evaluated independently from network throughput, congestion, or synchronization behavior.

This separation has shaped both engineering practice and benchmarking culture. Widely used performance indicators emphasize average throughput and steady-state behavior, while assuming that communication overhead can be amortized or hidden through overlap and scheduling techniques [

6,

7]. While effective at moderate scales, these assumptions become increasingly fragile as system size, heterogeneity, and synchronization intensity grow. In such regimes, compute-centric metrics remain necessary but prove insufficient to explain observed performance collapse and rising costs, motivating a closer examination of the role played by interconnect dynamics.

2.2. Interconnects as Active System Components

At contemporary scales, interconnects can no longer be regarded as passive conduits for data movement. Instead, they actively shape the execution of distributed workloads by mediating synchronization, enforcing ordering constraints, and coupling the progress of otherwise independent compute elements [

15,

16]. In large AI training and inference systems, collective communication patterns and fine-grained coordination render execution inherently dependent on interconnect behavior.

Several factors contribute to this shift. Synchronization dependencies amplify small variations in latency or throughput, allowing local perturbations to propagate across the system. Thermal effects, fluctuating load conditions, and gradual drift in link characteristics further modulate interconnect performance over time [

17]. As a result, runtime behavior becomes context-dependent and history-sensitive, undermining assumptions of determinism that underpin classical optimization models.

From this perspective, non-deterministic runtimes are not exceptional events but an emergent property of tightly coupled execution fabrics. Interconnects participate directly in shaping the critical path of computation, influencing when and how operator dependencies are resolved. This observation aligns with structural views of complex systems in which behavior arises from interactions rather than isolated components [

24]. Operator-oriented and complex-systems-based analyses, including approaches developed within SORT-CX, emphasize these interaction effects and treat interconnects as integral elements of the computational structure rather than auxiliary infrastructure [

2].

Recognizing interconnects as active system components reframes scalability challenges in AI infrastructure. It suggests that performance and cost inefficiencies observed at scale are rooted not solely in insufficient hardware resources, but in the structural coupling between compute and communication. This shift sets the stage for examining why classical metrics fail to capture these effects and how economic consequences emerge from structural instability, as discussed in

Section 3.

3. Why Classical Metrics Fail

3.1. The Measurement Gap

The diagnosis of performance and efficiency problems in large-scale AI and HPC systems traditionally relies on a well-established set of metrics. Latency, bandwidth, packet loss, utilization, and error rates form the backbone of network and system monitoring [

32]. These measurements are indispensable for detecting faults, capacity constraints, and deviations from expected behavior at the component level.

However, when applied to highly coupled runtime systems, these metrics exhibit a fundamental limitation. They are typically evaluated in isolation and aggregated over time or components, without explicit reference to the structural context in which communication occurs. As a result, they describe observable symptoms rather than the mechanisms that generate them. Elevated latency or reduced throughput may be detected, yet the causal relationship to specific operator dependencies, synchronization points, or execution phases remains opaque.

This lack of contextualization becomes particularly problematic in distributed workloads dominated by collective operations and fine-grained coordination [

12]. Delays that originate in a small subset of communication paths can propagate through synchronization barriers and amplify across the execution graph. Classical metrics often register such effects only after they have manifested as global slowdowns, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnoses. Consequently, remediation efforts focus on surface-level indicators rather than the underlying structural conditions that give rise to inefficiency.

3.2. The Invisibility of Structural Effects

A central reason why interconnect-induced instability remains difficult to detect lies in the prevailing component-based view of system monitoring. Metrics are collected and analyzed at the level of individual links, devices, or nodes, each evaluated against local thresholds and expectations. While this approach is effective for identifying hardware faults or isolated congestion, it obscures interactions that span multiple components and execution phases.

Figure 3.

Contrast between component-based and operator-graph views of distributed AI systems. The component-based view (left) treats compute, network, and storage as isolated layers with sequential dependencies. The operator-graph view (right) reveals synchronization points and non-local coupling patterns that govern actual runtime behavior and determine where instability effects propagate.

Figure 3.

Contrast between component-based and operator-graph views of distributed AI systems. The component-based view (left) treats compute, network, and storage as isolated layers with sequential dependencies. The operator-graph view (right) reveals synchronization points and non-local coupling patterns that govern actual runtime behavior and determine where instability effects propagate.

Many of the most consequential effects in large-scale AI systems are emergent in nature. They arise from the interaction of otherwise healthy components whose collective behavior produces non-linear outcomes [

25,

27]. Straggler effects, synchronization drift, and cascading delays may not be visible in any single metric stream, yet they significantly influence end-to-end execution time and cost. From a local perspective, each component appears to operate within acceptable bounds, even as global performance degrades.

Structural analyses grounded in complex-systems perspectives emphasize this distinction between local observables and global behavior [

26,

29]. Approaches developed within SORT-CX and related work highlight that runtime behavior is governed by the structure of operator dependencies and their coupling through interconnects, rather than by isolated hardware characteristics alone [

2]. Monitoring frameworks that focus exclusively on hardware metrics therefore capture the state of components, but not the structure that binds them into a coherent execution. This structural invisibility explains why interconnect instability is frequently overlooked until it manifests as economically significant inefficiency, a theme that motivates the subsequent examination of cost implications in

Section 5.

4. Instability as a Structural Phenomenon

4.1. Soft Degradation vs. Hard Failure

Interconnect-induced instability in large-scale AI and HPC systems rarely presents itself as an abrupt or catastrophic failure. Instead, it typically emerges as a pattern of soft degradation that unfolds gradually over time. Observable manifestations include latency jitter, temporal drift in communication paths, and partial synchronization losses between subsets of nodes. These effects do not trigger immediate error conditions, yet they steadily erode execution efficiency and predictability.

This mode of degradation differs fundamentally from classical failure models that assume clear fault boundaries and binary system states [

30]. In practice, distributed workloads continue to execute, but with increasing inefficiency, longer tail latencies, and reduced effective utilization. Because no single component crosses an explicit failure threshold, the system appears nominally healthy even as economic performance deteriorates.

As a consequence, such behavior is frequently misclassified. Soft degradation is often attributed to transient software issues, suboptimal scheduling, or isolated hardware irregularities, leading to localized remediation efforts that fail to address the underlying cause. Structural analyses developed in the context of SORT-CX emphasize that these patterns are not incidental bugs, but emergent behaviors arising from the interaction of tightly coupled components [

2]. Recognizing the distinction between soft degradation and hard failure is therefore essential for understanding why conventional debugging and optimization approaches prove ineffective at scale.

4.2. Non-Local Coupling and Emergent Effects

The structural origin of interconnect instability lies in non-local coupling effects that span nodes, devices, and execution phases. Modern AI infrastructures exhibit high compute density combined with heterogeneous accelerator fabrics, where GPUs, TPUs, or custom ASICs are integrated through complex interconnect topologies [

21]. These systems rely on frequent synchronization across distributed components, rendering execution progress sensitive to variations that occur far from the point at which their effects are observed.

Asynchronous interconnect behavior further amplifies this sensitivity. Variations in link latency, transient congestion, or thermal conditions can introduce small timing discrepancies that propagate through synchronization barriers and collective operations [

11]. Because these dependencies extend across the operator graph, local perturbations may trigger global consequences, including straggler cascades and phase misalignment between node groups.

From the perspective of complex systems theory, such behavior is characteristic of emergent phenomena in densely coupled networks [

24,

25,

27]. System-level outcomes cannot be inferred from the properties of individual components alone, but arise from the structure of interactions between them. Within SORT-CX, this insight is formalized by treating synchronization points and operator dependencies as first-class structural elements rather than incidental implementation details [

2]. This framing clarifies why interconnect instability persists despite incremental hardware improvements and sets the stage for examining its direct economic implications in subsequent sections.

5. The Economic Dimension: Where Real Costs Arise

5.1. Direct Cost Effects

The most immediate economic consequences of interconnect-induced instability arise from its direct impact on execution reliability and runtime predictability. In large-scale AI and HPC environments, non-deterministic behavior frequently necessitates partial or complete re-runs of workloads [

31]. These re-runs are not the result of explicit software defects or hardware faults, but of execution paths that diverge due to synchronization drift or timing instability. Each repetition translates directly into additional compute time, increased energy consumption, and delayed availability of results.

A related effect is performance collapse triggered by synchronization loss. Collective operations and global barriers amplify small timing deviations, causing entire execution phases to stall while waiting for straggling components [

8,

9]. When such stalls accumulate, effective throughput can drop sharply even though nominal resources remain allocated. In production environments, this behavior often manifests as missed deadlines or violations of service-level agreements, particularly in latency-sensitive inference pipelines.

Energy waste constitutes a further direct cost [

33]. Extended runtimes, stalled accelerators, and repeated execution phases consume power without delivering proportional computational value. Because energy expenditure scales with time and load rather than with useful output, instability-induced inefficiency translates directly into higher operating costs. Taken together, re-runs, synchronization-induced slowdowns, SLA violations, and excess energy consumption establish stability loss as an immediately budget-relevant phenomenon rather than a secondary technical concern.

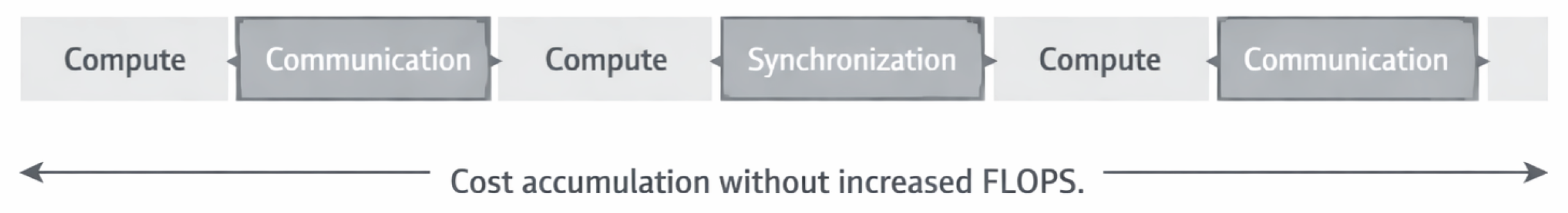

Figure 4.

Timeline view of a distributed AI job showing alternating compute and communication phases. Costs accumulate during communication and synchronization phases without corresponding increases in delivered FLOPS, illustrating how interconnect-dependent operations contribute to cost per performance collapse even when compute resources remain fully utilized.

Figure 4.

Timeline view of a distributed AI job showing alternating compute and communication phases. Costs accumulate during communication and synchronization phases without corresponding increases in delivered FLOPS, illustrating how interconnect-dependent operations contribute to cost per performance collapse even when compute resources remain fully utilized.

5.2. Hidden and Systemic Costs

Beyond these direct effects, interconnect instability generates a class of hidden and systemic costs that are more difficult to quantify yet often dominate the overall economic impact. One such cost arises from declining effective utilization. Although clusters may appear fully allocated, a growing fraction of reserved capacity is consumed by waiting, synchronization overhead, and partial progress that does not contribute to completed work [

14]. This discrepancy between nominal and effective utilization reduces the return on capital investment without necessarily triggering alarms in standard monitoring systems.

Energy and cooling costs also increase in ways that are not immediately attributable to specific failures [

33,

35]. Prolonged execution times, oscillating load patterns, and uneven resource usage stress power delivery and thermal management systems. These effects raise baseline energy consumption and cooling demand, even when aggregate workload volume remains constant. Because such increases are distributed across infrastructure subsystems, they are rarely traced back to structural instability in the execution fabric.

Crucially, many of these costs do not appear in any single dashboard or accounting metric. They emerge at the intersection of runtime behavior, infrastructure management, and economic planning, eluding attribution to specific components or events. As a result, organizations may underestimate the true cost of instability, focusing remediation efforts on visible symptoms while the underlying structural drivers persist. This gap between observable metrics and realized cost reinforces the need to treat stability as a first-order economic variable, a perspective that informs the discussion of mitigation strategies and decision relevance in subsequent sections (see

Section 6 and

Section 8).

A recurring operational pattern illustrates how these hidden costs accumulate in practice. In large-scale training and inference environments, teams frequently observe that certain workloads exhibit unexplained variability: some runs complete within expected time bounds, while others extend significantly or require re-submission, despite no identifiable hardware fault or software error. Standard monitoring shows all components operating within specification, yet tail behavior worsens over time and re-runs become normalized as part of operational routine. The resulting cost burden—additional compute hours, delayed model availability, engineering time spent on triage—does not appear as a line item attributable to instability, but is instead absorbed into baseline operational overhead. This pattern of soft degradation, hidden re-run costs, and unattributed tail latency represents precisely the class of systemic economic effects that conventional metrics fail to surface.

6. Why Over-Provisioning Is Not a Solution

A common response to declining performance and rising variability in large-scale AI infrastructures is to provision additional hardware capacity. By increasing the number of accelerators, links, or entire nodes, organizations aim to absorb inefficiencies through redundancy and headroom. While this strategy can provide short-term relief, it does not address the structural origins of interconnect-induced instability and therefore fails as a sustainable solution.

One fundamental limitation of over-provisioning is that additional hardware inevitably increases interconnect complexity. Each new node introduces further communication paths, synchronization dependencies, and coordination overhead [

10]. Rather than isolating instability, scaling out expands the surface on which timing variations, congestion, and drift can interact. As a result, the execution fabric becomes more sensitive to perturbations, not less.

This effect is compounded by the non-linear nature of synchronization. Many distributed AI workloads rely on collective operations whose cost scales with the number of participating nodes and the structure of their dependencies [

11,

13]. As system size grows, synchronization points multiply and critical paths lengthen, amplifying the impact of even minor delays. In such regimes, adding resources can paradoxically reduce effective throughput, as coordination overhead outpaces gains in raw compute capacity.

From an economic perspective, over-provisioning is equally problematic. Maintaining excess capacity to compensate for instability increases capital and operating expenditures without guaranteeing proportional returns [

34]. Safety margins embedded in scheduling, capacity planning, and service-level buffers often reflect a reaction to poorly understood instability rather than a principled mitigation strategy. These margins conceal structural inefficiencies by shifting costs into underutilized resources and inflated energy consumption.

Ultimately, over-provisioning treats instability as an external constraint to be buffered against, rather than as a property of the system that can be understood and managed. By masking symptoms instead of addressing causes, it entrenches economic inefficiency and obscures opportunities for more effective intervention. This recognition motivates the discussion of decision relevance and structural perspectives in the following section (see

Section 8), where stability is reconsidered as a variable that informs architectural and operational choices rather than a residual to be absorbed by excess hardware.

7. Toward a Structural Perspective

7.1. The Need for System-Level Analysis

The preceding sections have shown that the dominant challenges in large-scale AI and HPC infrastructures cannot be adequately explained through component-level reasoning alone. Traditional optimization strategies focus on improving the performance, reliability, or efficiency of individual elements such as accelerators, links, or schedulers. While necessary, these efforts systematically underaddress the interactions that bind components into a coherent execution fabric.

At scale, performance and cost are governed by coupling effects between compute, communication, and synchronization. Optimizing isolated components does not resolve delays that emerge from collective behavior, nor does it mitigate instability that propagates across operator dependencies. As a result, systems may exhibit nominally healthy components while suffering from degraded global efficiency, a pattern that has recurred throughout this analysis.

This observation motivates a shift in perspective. Rather than treating stability as a secondary concern or a residual outcome of performance tuning, it must be considered a primary economic variable. Stability determines whether allocated resources translate into usable results within predictable time and cost bounds. From this viewpoint, the central challenge is not merely to avoid errors, but to structurally manage efficiency under conditions of tight coupling and non-deterministic execution.

Frameworks that adopt a system-level perspective, including prior work within SORT-AI and SORT-CX, have emphasized the need to analyze distributed execution in terms of structural dependencies rather than isolated metrics [

1,

2]. Such approaches do not replace existing optimization techniques, but complement them by addressing the interaction patterns that ultimately govern scalability and economic performance.

7.2. Operator-Based Approaches

We mention operator-oriented approaches as an example class of structural formalisms, not as a prescriptive solution.

The analysis presented in this article is framework-agnostic and does not depend on any specific tooling or implementation; references to SORT-AI and SORT-CX serve solely as illustrative examples of how structural reasoning can be formalized, not as prerequisites for the conceptual argument developed here.

Throughout this discussion, the term operator graph refers to an abstraction that captures infrastructure-level coupling among compute operations, communication events, synchronization barriers, and coordination dependencies within a distributed execution. This notion is distinct from the dataflow or computation graphs employed internally by deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow or PyTorch, which primarily represent mathematical operations and tensor transformations at the software layer. The operator graph, as used here, models the structural relationships that govern how distributed hardware and runtime components interact—including timing dependencies, collective communication patterns, and cross-node synchronization—and is therefore essential for reasoning about interconnect-induced instability, which arises from coupling effects that lie outside the scope of framework-level execution representations.

A variety of structure-oriented approaches have been proposed to reason about complex, distributed systems beyond component-level descriptions. Among these, operator-based models provide a conceptual framework for representing computation as a graph of interdependent operations whose execution is coupled through communication and synchronization. In this representation, interconnect dynamics are not treated as external disturbances, but as intrinsic elements shaping the evolution of the operator graph.

Framework-based approaches such as SORT-AI have proposed treating operator dependencies and execution structure as first-class analytical objects, enabling the study of how instability propagates through distributed runtimes [

1]. Similarly, operator-oriented models developed in SORT-CX emphasize structural diagnostics that reveal coupling effects invisible to local metrics [

2]. Related perspectives in complex systems research underscore that global behavior emerges from interaction topology rather than from the properties of individual components alone [

28].

Within such formalisms, drift detection and structural diagnostics serve as conceptual tools for identifying when execution deviates from expected coordination patterns. Importantly, these notions are introduced here at an abstract level. No implementation strategies, algorithms, or control mechanisms are implied. The purpose is to demonstrate that formal reasoning about interconnect-induced instability is possible, and that such reasoning naturally operates at the level of structure rather than isolated measurements.

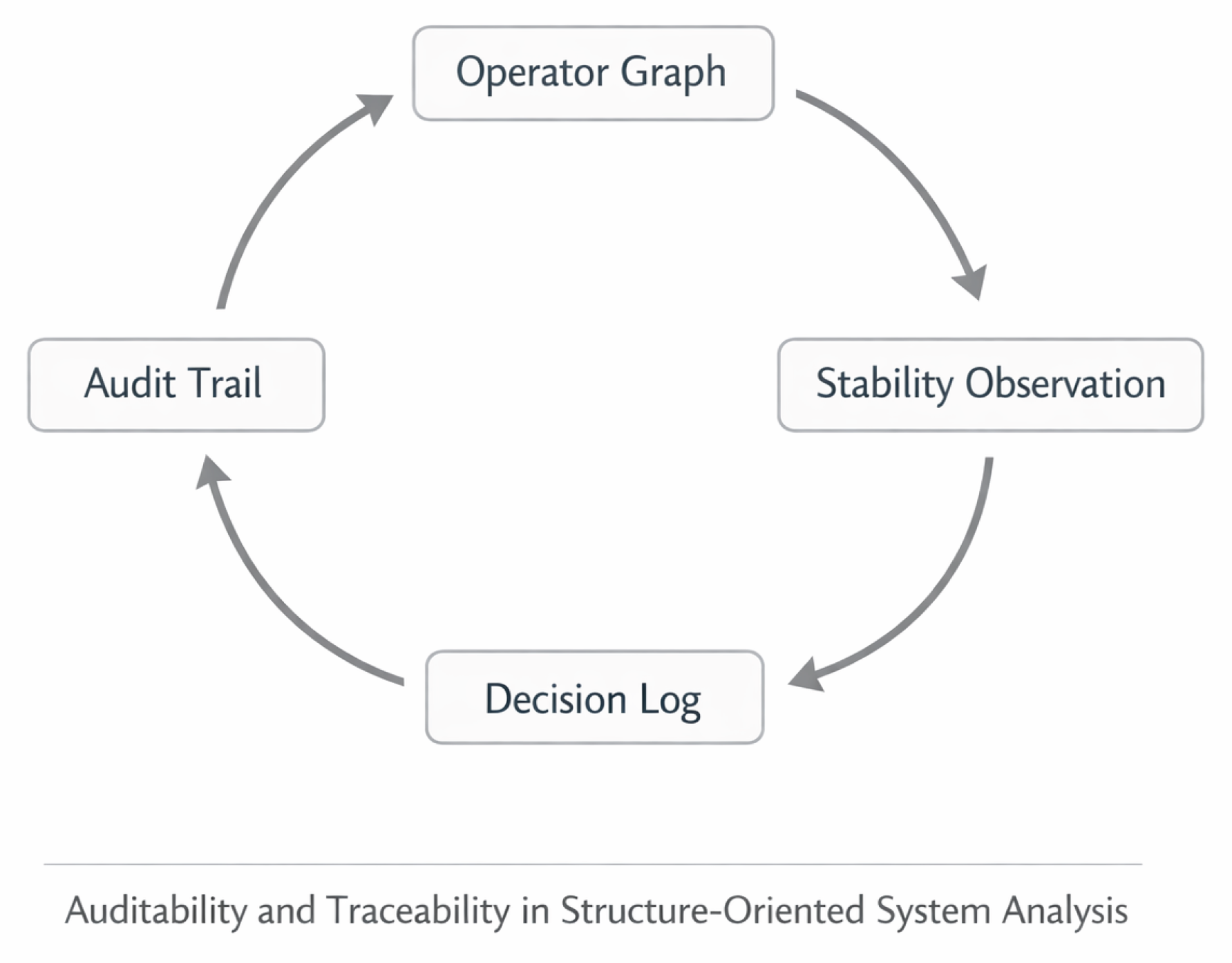

7.2.1. Auditability and Traceability of Operator Graphs

An additional implication of structure-oriented analysis is the role of auditability and traceability in assessing system stability. When execution is understood in terms of operator graphs and their evolution over time, it becomes possible to reason about stability through traceable execution protocols rather than post hoc interpretation of logs and metrics.

Figure 5.

Conceptual loop for auditability and traceability in structure-oriented system analysis. The operator graph provides the structural basis for execution; stability observations are derived from runtime behavior; decision logs capture responses to detected conditions; and an audit trail enables retrospective analysis and attribution of stability-relevant events.

Figure 5.

Conceptual loop for auditability and traceability in structure-oriented system analysis. The operator graph provides the structural basis for execution; stability observations are derived from runtime behavior; decision logs capture responses to detected conditions; and an audit trail enables retrospective analysis and attribution of stability-relevant events.

Auditability in this sense does not refer to compliance mechanisms or detailed instrumentation, but to the ability to reconstruct how structural conditions gave rise to specific outcomes. Traceable representations of operator dependencies allow instability events to be contextualized within the execution structure, supporting post-run analysis and informed decision-making. Prior work within SORT-AI has explored aspects of structural traceability and diagnostic reconstruction in related contexts [

3].

While this article does not pursue these directions further, the notion of auditability highlights an important qualitative distinction between component-level monitoring and structural analysis. Stability control, if it is to be economically meaningful, must be grounded in representations that make the consequences of coupling and coordination transparent rather than implicit.

8. Discussion

The analysis presented in this article reframes interconnect instability from a secondary performance concern into a structural and economic phenomenon with direct implications for large-scale AI and HPC systems. Rather than attributing cost overruns and performance collapse to isolated inefficiencies or transient faults, the preceding sections have argued that these effects emerge from coupling patterns inherent to modern distributed execution. This reframing has consequences both for practical system design and for future research directions.

From an architectural perspective, the findings suggest that continued scaling within existing paradigms will increasingly encounter non-linear cost regimes. As systems grow in size and heterogeneity, the space of stable operating conditions narrows, and small perturbations in synchronization or load can trigger disproportionate efficiency losses. For runtime design, this implies that traditional abstractions separating computation, communication, and coordination are becoming misaligned with observed system behavior. Runtimes that lack structural visibility into coupling effects are forced into reactive modes, relying on retries, safety margins, or conservative scheduling to compensate for instability.

At the same time, this analysis has clear limitations. It is intentionally conceptual, does not present empirical measurements, and does not propose or evaluate concrete mitigation strategies. As such, it should be read as a problem formulation and classification effort rather than a solution blueprint.

8.1. Implications for Architecture and Procurement Decisions

One of the most immediate consequences of a structural perspective on interconnect instability lies in how scaling decisions are evaluated. The analysis indicates that there exist thresholds beyond which scaling behavior changes qualitatively. Beyond these points, additional nodes or accelerators no longer yield proportional gains, and may instead amplify synchronization overheads and instability. Identifying where such thresholds lie becomes a strategic concern, even if they cannot be expressed as single numerical limits.

The discussion also clarifies why isolated interconnect upgrades are often insufficient. Increasing bandwidth or reducing nominal latency addresses individual links, but does not resolve the coupling patterns that give rise to non-local effects. When instability is driven by interaction topology rather than by raw link capacity, incremental hardware improvements risk masking symptoms while leaving structural causes intact.

A further implication is that stability considerations naturally migrate into the control plane of large-scale systems. If stability determines effective cost per performance, then models that describe and anticipate instability become relevant not only for operators, but for decision-makers. This does not imply adopting specific tools or frameworks, but it does suggest a shift in emphasis: from asking how fast or how large a system can be built, to asking under which structural conditions it remains economically viable.

For procurement and architectural planning, this perspective reframes the key questions. Instead of focusing exclusively on component specifications, decision-makers may need to ask how proposed systems expose, manage, or obscure structural coupling. What assumptions are made about synchronization behavior at scale? How is non-determinism handled when it becomes systemic rather than exceptional? And how can stability be assessed before significant capital is committed? These questions do not prescribe answers, but they open conversations that become increasingly difficult to avoid as AI and HPC infrastructures continue to scale.

8.2. Open Research Questions

The structural analysis developed in this article raises several research questions that remain open and warrant systematic investigation. These questions are not rhetorical, but point toward concrete directions for future work across systems research, complex systems theory, and infrastructure economics.

Formal characterization of structural instability: How can interconnect-induced instability be formally characterized in a manner that is independent of specific hardware configurations, software stacks, or workload types? What minimal mathematical representations are sufficient to capture coupling effects and predict instability onset without introducing prohibitive measurement or computational overhead?

Scaling thresholds and phase transitions: Are there identifiable thresholds or phase transitions in the scaling behavior of distributed AI systems beyond which instability effects qualitatively dominate system economics? If so, what system parameters—such as node count, synchronization frequency, or topology complexity—govern the location of these transitions, and can they be predicted from structural properties of the execution fabric prior to deployment?

Stability as a first-class design constraint: How can stability be incorporated as a first-class constraint in system design, capacity planning, and procurement evaluation, rather than being treated as a residual outcome of performance optimization? What design principles, architectural patterns, or evaluation methodologies would allow systems to maintain predictable cost per performance as they scale into regimes where coupling effects dominate?

Observability requirements for structural diagnostics: What forms of observability and instrumentation are required to detect and attribute structural instability in real time or near-real time? How do these requirements differ from conventional component-level monitoring, and what trade-offs exist between diagnostic depth, instrumentation cost, and runtime overhead?

Economic quantification and attribution: How can the economic impact of structural instability be quantified in a manner that supports investment, procurement, and operational decisions? What accounting frameworks or cost models would allow organizations to attribute hidden costs—such as re-runs, over-provisioning, and reduced effective utilization—to their structural origins rather than to surface-level symptoms?

These questions underscore that the problem of interconnect-induced instability is not merely technical, but intersects with architectural reasoning, economic planning, complex systems theory, and the design of future AI infrastructure at scale.

8.3. Outlook on Empirical Validation.

While the present work deliberately focuses on structural analysis rather than empirical benchmarking, it is intended as a foundation for subsequent quantitative studies. Ongoing and future work will operationalize the structural stability concepts introduced here and evaluate them empirically in controlled large-scale environments. This separation is intentional: without a prior structural model of interconnect coupling and instability, empirical measurements risk remaining descriptive rather than diagnostic. The contribution of this paper is therefore not to replace empirical evaluation, but to provide the conceptual and analytical framework required for meaningful measurement and comparison.

9. Conclusions

This article has argued that interconnect stability must be understood as a structural property of large-scale AI and HPC systems rather than as an operational anomaly to be mitigated through incremental fixes. As system scale, heterogeneity, and synchronization density increase, instability emerges not from isolated component failures but from non-local coupling effects embedded in execution structure and coordination patterns.

Within this perspective, cost per performance is no longer determined solely by compute efficiency or nominal interconnect specifications. Instead, it arises as a systemic consequence of how computation, communication, and synchronization interact across the system. Effects such as silent degradation, straggler cascades, and tail latency inflation directly translate into economic loss, even in the absence of observable faults. Treating these effects as secondary or transient obscures their role as primary cost drivers.

The analysis further motivates the need for structure-oriented approaches to system understanding. While no specific solution or framework is advocated, the discussion highlights that component-level optimization alone is insufficient once instability is driven by global interaction patterns. Conceptual models capable of representing coupling, drift, and emergent behavior become necessary to reason about stability in a meaningful way.

Importantly, this work does not propose implementations, products, or prescriptive remedies. Its contribution lies in problem formulation and reclassification: positioning interconnect instability as a first-order structural phenomenon with economic implications. By making this shift explicit, the article aims to support more informed architectural reasoning and to frame future research around the conditions under which large-scale systems remain both performant and economically viable.

Data Availability Statement

The complete SORT v6 framework, including operator definitions, validation protocols, and reproducibility manifests, is archived on Zenodo under DOI

10.5281/zenodo.18094128. The MOCK v4 validation environment is archived at

10.5281/zenodo.18050207. Source code and supplementary materials are maintained at

GitHub. Domain-specific preprints are available via the MDPI Preprints server.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the foundational architectural work developed in earlier SORT framework versions, which enabled the completion of the present architecture.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

The author confirms that no artificial intelligence tools were used in the generation of scientific content, theoretical concepts, mathematical formulations, or results. Automated tools were used exclusively for editorial language refinement and LaTEX formatting assistance.

References

- Wegener, G. H. (2025). SORT-AI: A Projection-Based Structural Framework for AI Safety—Alignment Stability, Drift Detection, and Scalable Oversight. Preprints 2024121334. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. H. (2025). SORT-CX: A Projection-Based Structural Framework for Complex Systems—Operator Geometry, Non-Local Kernels, Drift Diagnostics, and Emergent Stability. Preprints 2024121431. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. H. (2025). SORT-AI: A Structural Safety and Reliability Framework for Advanced AI Systems with Retrieval-Augmented Generation as a Diagnostic Testbed. Preprints 2024121345. [CrossRef]

- Dean, J., & Barroso, L. A. (2013). The Tail at Scale. Communications of the ACM 56(2), 74–80. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, D., et al. (2021). Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. Proceedings of SC21. [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari, S., et al. (2020). ZeRO: Memory Optimizations Toward Training Trillion Parameter Models. Proceedings of SC20. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., et al. (2019). GPipe: Efficient Training of Giant Neural Networks using Pipeline Parallelism. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32.

- Ananthanarayanan, G., et al. (2013). Effective Straggler Mitigation: Attack of the Clones. Proceedings of NSDI’13, 185–198.

- Zaharia, M., et al. (2008). Improving MapReduce Performance in Heterogeneous Environments. Proceedings of OSDI’08, 29–42.

- Hoefler, T., et al. (2010). Scalable Communication Protocols for Dynamic Sparse Data Exchange. Proceedings of PPoPP’10, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Patarasuk, P., & Yuan, X. (2009). Bandwidth Optimal All-Reduce Algorithms for Clusters of Workstations. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 69(2), 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R., Rabenseifner, R., & Gropp, W. (2005). Optimization of Collective Communication Operations in MPICH. International Journal of High Performance Computing Applications 19(1), 49–66. [CrossRef]

- Chan, E., et al. (2007). Collective Communication: Theory, Practice, and Experience. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 19(13), 1749–1783. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A., et al. (2015). Large-Scale Cluster Management at Google with Borg. Proceedings of EuroSys’15, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al. (2019). Evaluating Modern GPU Interconnect: PCIe, NVLink, NV-SLI, NVSwitch and GPUDirect. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 30(1), 94–110.

- Alizadeh, M., et al. (2010). Data Center TCP (DCTCP). Proceedings of SIGCOMM’10, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., et al. (2016). RDMA over Commodity Ethernet at Scale. Proceedings of SIGCOMM’16, 202–215. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03561-3.

- Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30.

- Brown, T. B., et al. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 1877–1901.

- Jouppi, N. P., et al. (2017). In-Datacenter Performance Analysis of a Tensor Processing Unit. Proceedings of ISCA’17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Amodei, D., et al. (2016). Concrete Problems in AI Safety. arXiv:1606.06565.

- Hubinger, E., et al. (2019). Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems. arXiv:1906.01820.

- Bar-Yam, Y. (1997). Dynamics of Complex Systems. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-55748-1.

- Newman, M. (2010). Networks: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920665-0.

- Albert, R., & Barabási, A.-L. (2002). Statistical Mechanics of Complex Networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 47–97. [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M., et al. (2009). Early-Warning Signals for Critical Transitions. Nature 461, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A Guided Tour. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512441-5.

- Strogatz, S. H. (2001). Exploring Complex Networks. Nature 410, 268–276. [CrossRef]

- Avizienis, A., et al. (2004). Basic Concepts and Taxonomy of Dependable and Secure Computing. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 1(1), 11–33. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, J., et al. (2021). CheckFreq: Frequent, Fine-Grained DNN Checkpointing. Proceedings of FAST’21, 203–216.

- Jain, R. (1991). The Art of Computer Systems Performance Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-50336-1.

- Barroso, L. A., & Hölzle, U. (2007). The Case for Energy-Proportional Computing. IEEE Computer 40(12), 33–37. [CrossRef]

- Barroso, L. A., Clidaras, J., & Hölzle, U. (2013). The Datacenter as a Computer: An Introduction to the Design of Warehouse-Scale Machines (2nd ed.). Synthesis Lectures on Computer Architecture 8(3), 1–154. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M. K. (2008). The Effect of Data Center Temperature on Energy Efficiency. Proceedings of ITHERM’08, 1167–1174. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).