Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

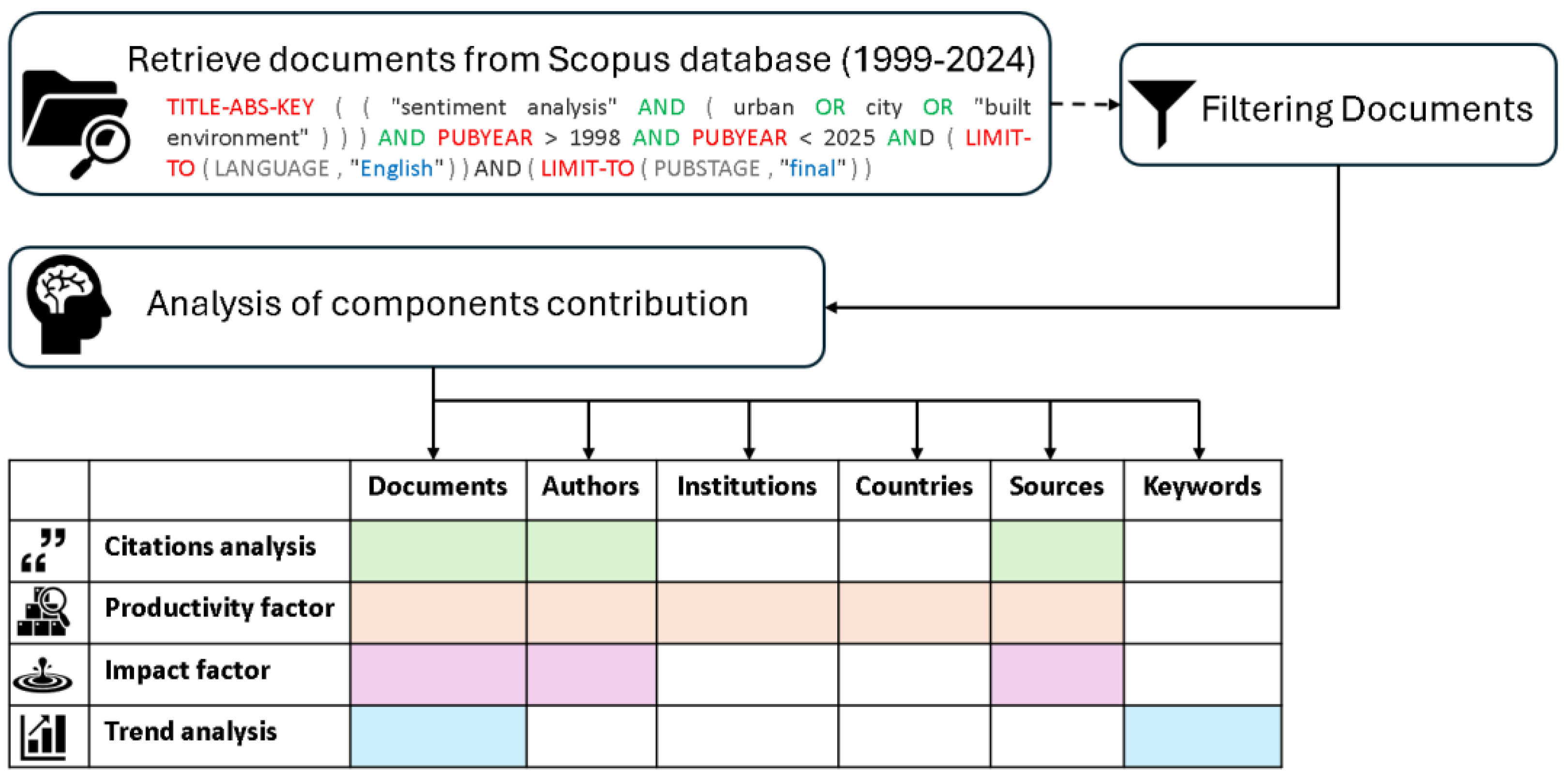

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Research Strategy

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

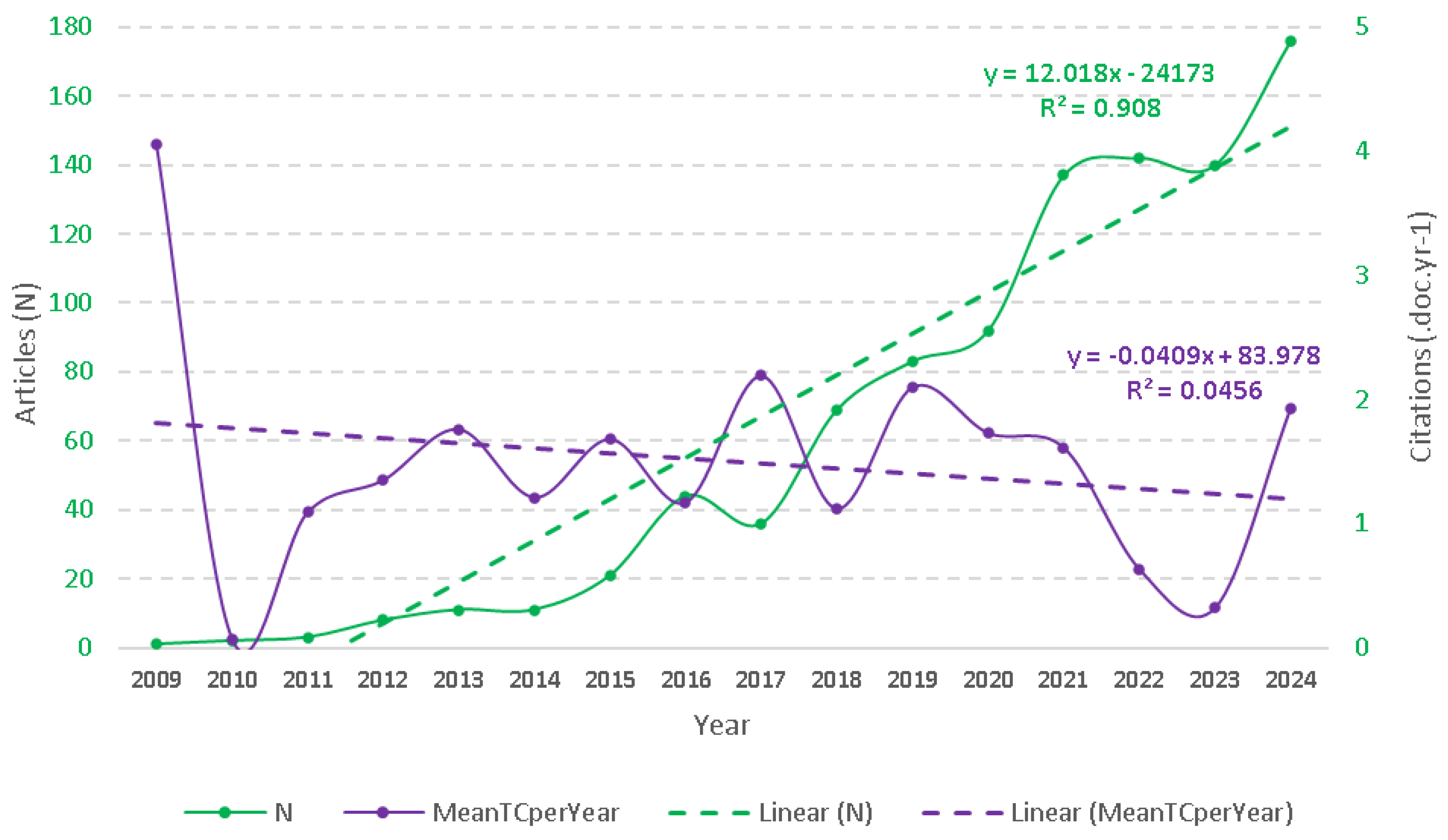

3.1. Document Characteristics, Trends, and Citations

3.1.1. Most Influential Publications on Sentiment Analysis in Urban Built Environment

3.1.2. Author Analysis

3.1.3. Influential Sources Publishing on Sentiment Analysis …

3.1.4. Funding and Authorship Affiliation Funds

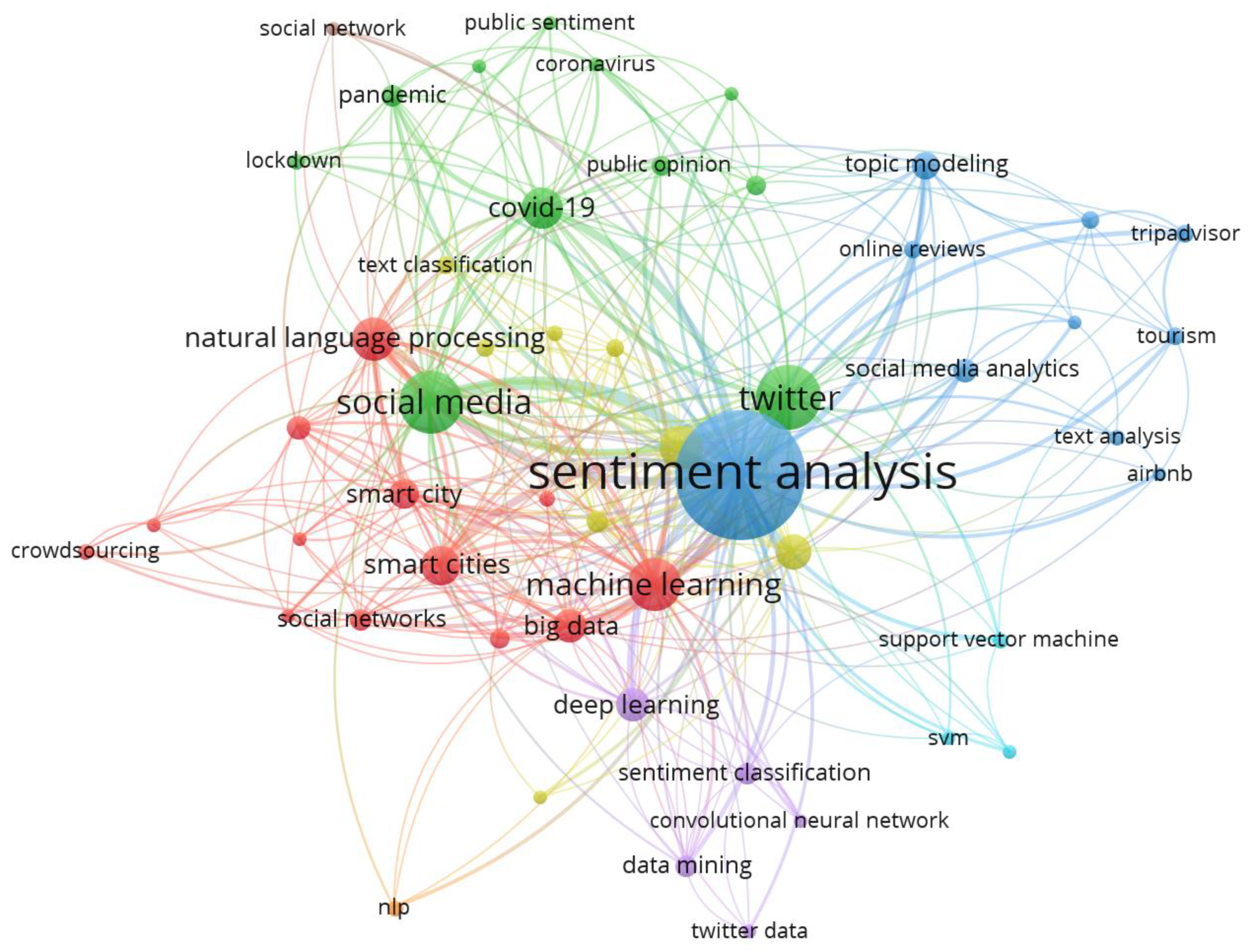

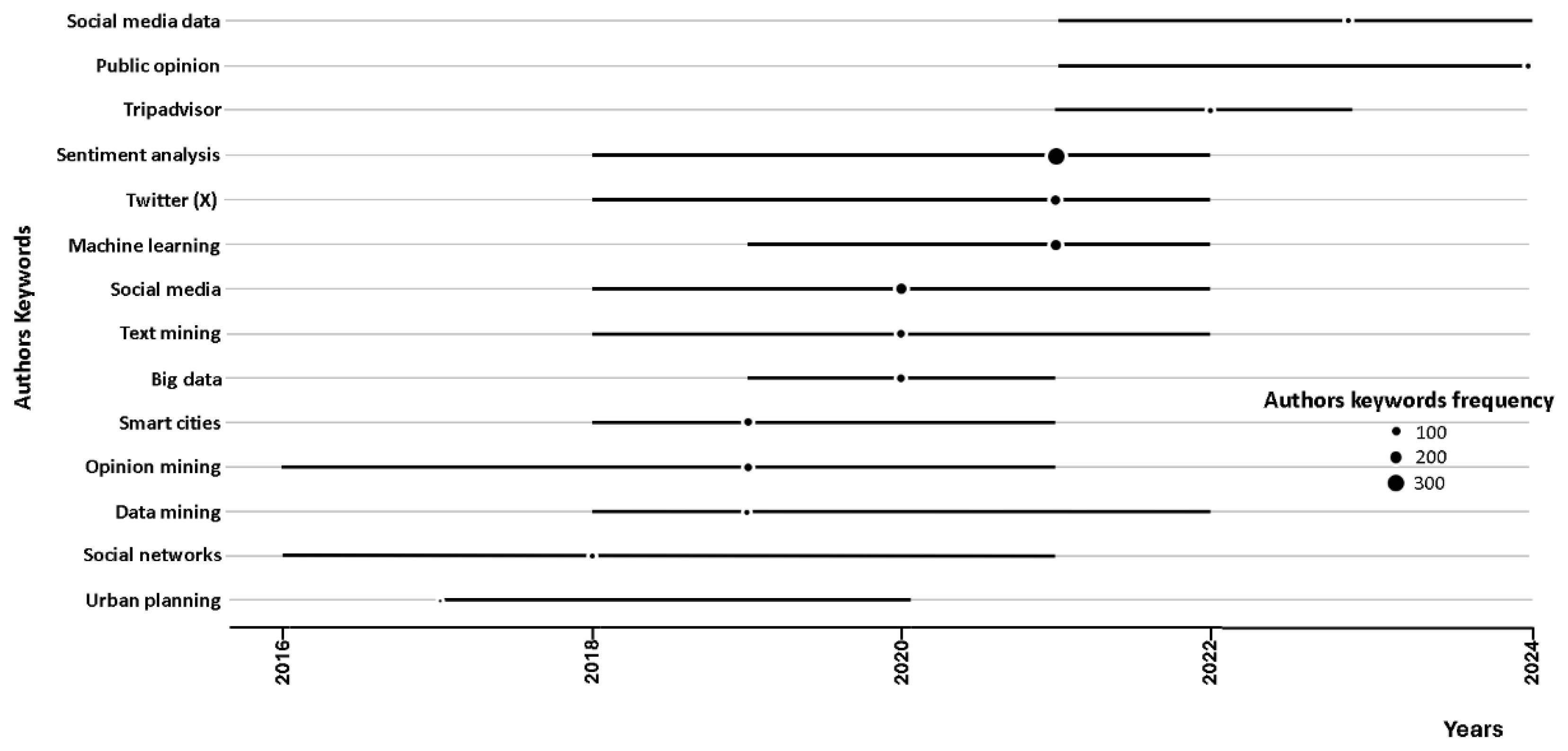

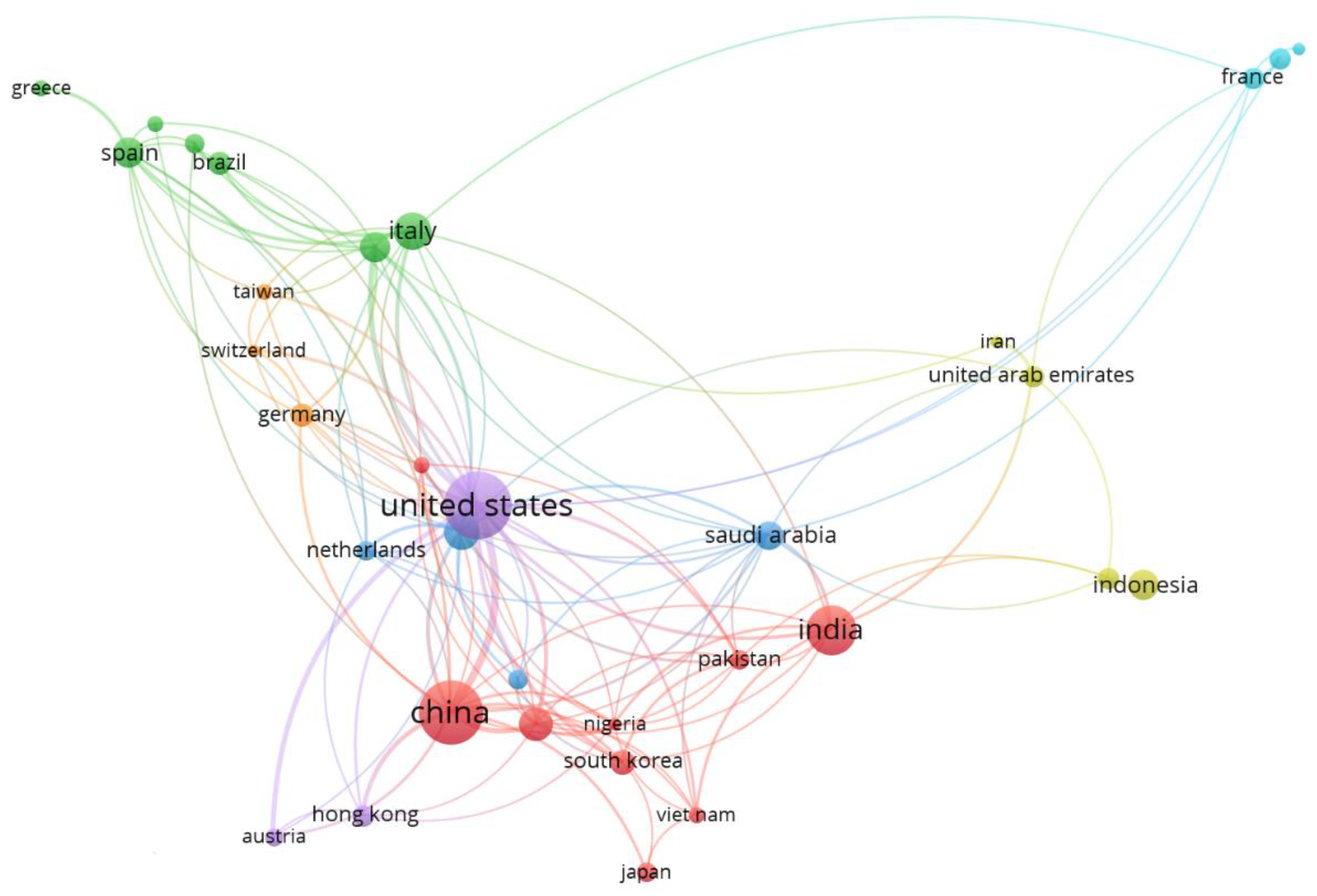

3.2. Network analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pineo, H.; Rydin, Y. Cities, Health and Well-Being. R. Inst. Chart. Surv. London, UK. 2018, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka, B.H. Depression as a Disease of Modernity: Explanations for Increasing Prevalence. Natl. Institutes Heal. 2012, 140, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, M.; Berger, M.; Brakemeier, E.L.; Engel, L.; Fingerhut, J.; Gomez-Carrillo, A.; Hehl, R.; Heinz, A.; Mayer, J.; Mehran, N.; et al. Neurourbanism: Towards a New Discipline. The Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederbogen, F.; Kirsch, P.; Haddad, L.; Streit, F.; Tost, H.; Schuch, P.; Wüst, S.; Pruessner, J.C.; Rietschel, M.; Deuschle, M.; et al. City Living and Urban Upbringing Affect Neural Social Stress Processing in Humans. Nature 2011, 474, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peen, J.; Schoevers, R.A.; Beekman, A.T.; Dekker, J. The Current Status of Urban-Rural Differences in Psychiatric Disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 121, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S. The Urban Brain: New Directions in Research Exploring the Relation between Cities and Mood–Anxiety Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.R. Biodiversity Conservation and the Extinction of Experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T. Nature Experience in Transactional Perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1993, 25, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakolis, I.; Hammoud, R.; Smythe, M.; Gibbons, J.; Davidson, N.; Tognin, S.; Mechelli, A. Urban Mind: Using Smartphone Technologies to Investigate the Impact of Nature on Mental Well-Being in Real Time. Bioscience 2018, 68, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Neighborhood Nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature. Bioscience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, R.; Tognin, S.; Burgess, L.; Bergou, N.; Smythe, M.; Gibbons, J.; Davidson, N.; Afifi, A.; Bakolis, I.; Mechelli, A. Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment Reveals Mental Health Benefits of Birdlife. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, R.; Roquette, R.; Rebecchi, A.; Matias, J.; Rocha, J.; Buffoli, M.; Capolongo, S.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Nunes, B.; Dias, C.; et al. Association between Area-Level Walkability and Glycated Haemoglobin: A Portuguese Population-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Györi, A.; Ristea, A.; Kolcsar, R.; Resch, B.; Crivellari, A.; Blaschke, T. Beyond Spatial Proximity-Classifying Parks and Their Visitors in London Based on Spatiotemporal and Sentiment Analysis of Twitter Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Györi, A.; Ristea, A.; Havas, C.; Resch, B.; Cabrera-Barona, P. #London2012: Towards Citizen-Contributed Urban Planning through Sentiment Analysis of Twitter Data. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romice, O.; Thwaites, K.; Porta, S.; Greaves, M.; Barbour, G.; Pasino, P. City Form and Wellbeing. In The Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Fleury-Bahi, Ghozlane, Pol, Enric, Navarro, O., Eds.; Springer, 2016; pp. 241–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, James; Kitchin, Rob; Leszczynski, Agnieszka. Digital Turn, Digital Geographies? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 42, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.; Hnit, H. Digital Human Rights: Legal Debates and Emerging Foundations under the International Bill of Human Rights. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, R.F. Social Media, Human Rights and Society. In Routledge Handbook of Social: Media, Law and Society; 2025; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenloasiri, N.; Yimsook, N.; Walsh, C. Understand and Find a Mechanism to Enhance the Power of App-Based Food Delivery Riders in Thailand. J. Arts Thai Stud. 2025, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arginbekova, G.; Amitov, S.; Kyndybayeva, R.; Bakbergen, K. Human Values in the Age of Digitalization. Sci. Her. Uzhhorod Univ. Ser. Phys. 2024, 2275–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, N. Facial Recognition Technology in Policing and Security—Case Studies in Regulation. Laws 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunic, A.; Corcoran, P.; Spasic, I. Sentiment Analysis in Health and Well-Being: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. informatics 2020, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhat, W.; Hassan, A.; Korashy, H. Sentiment Analysis Algorithms and Applications : A Survey. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2014, 5, 1093–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balahur, A.; Mihalcea, R.; Montoyo, A. Preface: Computational Approaches to Subjectivity and Sentiment Analysis: Present and Envisaged Methods and Applications. Comput. Speech Lang. 2014, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayaa, S.; Jaafar, N.I.; Bahri, S.; Sulaiman, A.; Wai, P.S.; Chung, Y.W.; Piprani, A.Z.; Al-garadi, M.A. Sentiment Analysis of Big Data : Methods, Applications, and Open Challenges. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 37807–37827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D.; Funk, A. Automatic Detection of Political Opinions in Tweets. In The Semantic Web: ESWC 2011 Workshops. ESWC 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; García-Castro, R., Fensel, D., Antoniou, G., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 88–99. ISBN 978-3-642-25953-1. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.; Silva, E.A. Crowdsourced Data Mining for Urban Activity: Review of Data Sources, Applications, and Methods. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, Ivan; Čater, Tomaž. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N. Forty Years of the Journal of Futures Markets: A Bibliometric Overview. J. Futur. Mark. 2021, 41, 1027–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An Approach for Detecting, Quantifying, and Visualizing the Evolution of a Research Field: A Practical Application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory Field. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodrígue, A.-R.; Ruíz-Navarro, J. Changes in the Intellectual Structure of Strategic Management Research: A Bibliometric Study of the Strategic Management Journal, 1980-2000. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 981–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Pandey, N.; Kumar, S.; Haldar, A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Board Diversity: Current Status, Development, and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunger, D.; Eulerich, M. Bibliometric Analysis of Corporate Governance Research in German-Speaking Countries: Applying Bibliometrics to Business Research Using a Custom-Made Database. Scientometrics 2018, 117, 2041–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.H.; Zamit, I.; Xu, K.; Boutouhami, K.; Qi, G. A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis on Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis Global Research Output. J. Inf. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkalbasi, N.; Bauer, K.; Glover, J.; Wang, L. Three Options for Citation Tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H.; Silva, E.R.; Lessa, M.; Proença, D.J.; Bartholo, R. VOSviewer and Bibliometrix. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busteed, M. Little Islands of Erin: Irish Settlement and Identity in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Manchester. Immigrants Minor. 1999, 18, 94–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Beverungen, D.; Räckers, M.; Becker, J. What Makes Local Governments’ Online Communications Successful? Insights from a Multi-Method Analysis of Facebook. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jeong, M.; Lee, J. Roles of Negative Emotions in Customers’ Perceived Helpfulness of Hotel Reviews on a User-Generated Review Website: A Text Mining Approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbado, R.; Araque, O.; Iglesias, C.A. A Framework for Fake Review Detection in Online Consumer Electronics Retailers. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Martínez-Torres, R.; Toral, S. Post-Visit and Pre-Visit Tourist Destination Image through EWOM Sentiment Analysis and Perceived Helpfulness. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2609–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuja, J.; Alanazi, E.; Alasmary, W.; Alashaikh, A. COVID-19 Open Source Data Sets: A Comprehensive Survey. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 1296–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavattaro, S.M.; French, P.E.; Mohanty, S.D. A Sentiment Analysis of U.S. Local Government Tweets: The Connection between Tone and Citizen Involvement. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, D.; ten Thij, M.; Bathina, K.; Rutter, L.A.; Bollen, J. Social Media Insights into US Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Lu, K.; Chow, K.P.; Zhu, Q. COVID-19 Sensing: Negative Sentiment Analysis on Social Media in China via BERT Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 138162–138169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kwak, D.; Khan, P.; Islam, S.M.R.; Kim, K.H.; Kwak, K.S. Fuzzy Ontology-Based Sentiment Analysis of Transportation and City Feature Reviews for Safe Traveling. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 77, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cho, Y.; Jang, S.Y. Crime Prediction Using Twitter Sentiment and Weather. In Proceedings of the 2015 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium, SIEDS 2015, 2015; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2008, 2, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.; Frank, M.R.; Harris, K.D.; Dodds, P.S.; Danforth, C.M. The Geography of Happiness: Connecting Twitter Sentiment and Expression, Demographics, and Objective Characteristics of Place. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, J.; Mao, H.; Zeng, X. Twitter Mood Predicts the Stock Market. J. Comput. Sci. 2011, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining; Springer Nature, 2022; ISSN ISBN 3031021452. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, L. A Survey of Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis BT - Mining Text Data; Aggarwal, C.C., Zhai, C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2012; pp. 415–463. ISBN 978-1-4614-3223-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Du, Q.; Ma, Y.; Fan, W. A Comparative Analysis of Major Online Review Platforms: Implications for Social Media Analytics in Hospitality and Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic Word-of-Mouth in Hospitality and Tourism Management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, T.; Okazaki, M.; Matsuo, Y. Earthquake Shakes Twitter Users: Real-Time Event Detection by Social Sensors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, New York, NY, USA, 2010; Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 851–860. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, R.P.; Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M.; de Jong, M. A Comparison of National Open Data Policies: Lessons Learned. Transform. Gov. People, Process Policy 2015, 9, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Khan, I.A.; Verma, A.; Sharma, S. Recent Trends in Sentiment Analysis Tools. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, 2023; Vol. 2771. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. {VOSviewer} Manual. In Leiden: Univeristeit Leiden; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Knani, M.; Echchakoui, S.; Ladhari, R. Artificial Intelligence in Tourism and Hospitality: Bibliometric Analysis and Research Agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, J.G.J.S.; Juliet, S. Deep Learning-Based Sentiment Analysis of Trip Advisor Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), 2023; pp. 560–565. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, M.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, J. Language Interpretation in Travel Guidance Platform: Text Mining and Sentiment Analysis of TripAdvisor Reviews. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramatfar, A.; Amirkhani, H. Bibliometrics of Sentiment Analysis Literature. J. Inf. Sci. 2018, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, G.; Lan, M. ECNU: Multi-Level Sentiment Analysis on Twitter Using Traditional Linguistic Features and Word Embedding Features. In Proceedings of the SemEval 2015 - 9th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, co-located with the 2015 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2015 - Proceedings; Nakov P. Zesch T., C.D.J.D., Ed.; Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 2015; pp. 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, S.M.; Turney, P. NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon (Aka EmoLex). Available online: https://saifmohammad.com/WebPages/NRC-Emotion-Lexicon.htm (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. A Sentimental Education: Sentiment Analysis Using Subjectivity Summarization Based on Minimum Cuts. Proc. Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist., 2004 ; pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Afriliana, N.; Iswari, N.M.S. Suryasari Sentiment Analysis of User-Generated Content: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2022, 12, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Shen, Z.; Luo, X. Exploring the Relationship between Urban Youth Sentiment and the Built Environment Using Machine Learning and Weibo Comments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, S.; Li, W.; Qiu, W. Measuring the Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity of Helplessness Sentiment and Its Built Environment Determinants during the COVID-19 Quarantines: A Case Study in Shanghai. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashayeri, M.; Abbasabadi, N. Unraveling Energy Justice in NYC Urban Buildings through Social Media Sentiment Analysis and Transformer Deep Learning. Energy Build. 2024, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tu, H. Inconsistent Affective Reaction: Sentiment of Perception and Opinion in Urban Environments. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia 2024, Vol. 2, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Sun, R. Sentiment Variations Affected by Urban Temperature and Landscape across China. Cities 2024, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Sun, R.; Li, J.; Li, W. Urban Landscape and Climate Affect Residents’ Sentiments Based on Big Data. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 152, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mu, L.; Gong, S.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y. Measuring Urban Sentiments from Social Media Data: A Dual-Polarity Metric Approach. J. Geogr. Syst. 2022, 24, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Gai, Z.; Li, S.; Cao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhou, L. Does the Built Environment of Settlements Affect Our Sentiments? A Multi-Level and Non-Linear Analysis of Xiamen, China, Using Social Media Data. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Yu, B.; Ma, J.; Luo, K.; Chen, S.; Shen, Z. Exploring the Non-Linear Relationship and Synergistic Effect between Urban Built Environment and Public Sentiment Integrating Macro- and Micro-Level Perspective: A Case Study in San Francisco. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Gustafsson, A. Investigating the Emerging COVID-19 Research Trends in the Field of Business and Management: A Bibliometric Analysis Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betco, I.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Vale, D.S.; Encalada-Abarca, L.; Viana, C.M.; Rocha, J. Sentiment Analysis Using a Lexicon-Based Approach in Lisbon, Portugal. Geospat. Health 2025, 20, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.H.M.; Painho, M. Open Geospatial Data Contribution Towards Sentiment Analysis Within the Human Dimension of Smart Cities. Lecture Notes in Intelligent Transportation and Infrastructure 2021, Vol. Part F1384, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

| Rank | Authors | Title | Year | TC | TC.yr-1 | Normalized TC | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sara Hofmann Daniel Beverungen Michael Räckers Jörg Becker |

What makes local governments’ online communications successful? Insights from a multi-method analysis of Facebook | 2013 | 170 | 14.17 | 8.03 | Government Information Quarterly[42] |

| 2 | Minwoo Lee Miyoung Jeong Jongseo Lee |

Roles of negative emotions in customers’ perceived helpfulness of hotel reviews on a user-generated review website: A text mining approach | 2017 | 146 | 18.25 | 8.33 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management[43] |

| 3 | Rodrigo Barbado Oscar Araque Carlos A. Iglesias |

A framework for fake review detection in online consumer electronics retailers | 2019 | 130 | 21.67 | 10.33 | Information Processing & Management[44] |

| 4 | M. Rosario González-Rodríguez Rocio Martínez-Torres Sergio Toral |

Post-visit and pre-visit tourist destination image through eWOM sentiment analysis and perceived helpfulness | 2016 | 118 | 13.11 | 11.17 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management [45] |

| 5 | Junaid Shuja Eisa Alanazi Waleed Alasmary Abdulaziz Alashaikh |

COVID-19 open source data sets: a comprehensive survey | 2021 | 110 | 27.50 | 17.09 | Applied Intelligence[46] |

| 6 | Staci M. Zavattaro P. Edward French Somya D. Mohanty |

A sentiment analysis of U.S. local government tweets: The connection between tone and citizen involvement | 2015 | 109 | 10.90 | 6.48 | Government Information Quarterly [47] |

| 7 | Danny Valdez Marijn ten Thij Krishna Bathina Lauren A Rutter Johan Bollen |

Social Media Insights into US Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analysis of Twitter Data | 2020 | 106 | 21.20 | 12.28 | Journal Of Medical Internet Research [48] |

| 8 | Tianyi Wang Ke Lu Kam Pui Chow Qing Zhu |

COVID-19 Sensing: Negative Sentiment Analysis on social media in China via BERT Model | 2020 | 101 | 20.20 | 11.70 | IEEE Access [49] |

| 9 | Farman Ali Daehan Kwak Pervez Khan S.M. Riazul Islam Kye Hyun Kim K.S. Kwak |

Fuzzy ontology-based sentiment analysis of transportation and city feature reviews for safe traveling | 2017 | 101 | 12.63 | 5.76 | Transportation Research Part C [50] |

| 10 | Xinyu Chen Youngwoon Cho Suk young Jang |

Crime Prediction Using Twitter Sentiment and Weather | 2015 | 90 | 9.00 | 5.35 | 2015 Systems & Information Engineering Design Symposium [51] |

| T | Authors | Article | Year | TC | TC.yr-1 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bo Pang Lillian Lee |

Opinion mining and sentiment analysis | 2008 | 21 | 1.24 | Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval [52] |

| 2 | Lewis Mitchell Morgan R. Frank Kameron Decker Harris Peter Sheridan Dodds Christopher M. Danforth |

The geography of happiness: Connecting twitter sentiment and expression, demographics, and objective characteristics of place | 2013 | 14 | 1.17 | PLOS ONE [53] |

| 3 | David M. Blei Andrew Y. Ng Michael I. Jordan |

Latent Dirichlet Allocation | 2003 | 13 | 0.59 | Journal of Machine Learning Research [54] |

| 4 |

Johan Bollen Huina Mao Xiaojun Zeng |

Twitter mood predicts the stock market | 2011 | 11 | 0.79 | Journal of Computational Science [55] |

| 5 | Bing Liu | Sentiment analysis and opinion mining | 2022 | 11 | 3.67 | Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies [56] |

| 6 | Bing Liu Lei Zhang |

A Survey of Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis | 2012 | 10 | 0.77 | Mining Text Data [57] |

| 7 | Walaa Medhat Ahmed Hassan Hoda Korashy |

Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: A survey |

2014 | 10 | 0.91 | Ain Shams Engineering Journal [24] |

| 8 | Zheng Xiang Qianzhou Du Yufeng Ma Weiguo Fan |

A comparative analysis of major online review platforms: Implications for social media analytics in hospitality and tourism | 2017 | 9 | 1.13 | Tourism Management [58] |

| 9 | Stephen W. Litvin Ronald E. Goldsmith Bing Pan |

Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management | 2008 | 8 | 0.47 | Tourism Management [59] |

| 10 | Takeshi Sakaki Makoto Okazaki Yutaka Matsuo |

Earthquake shakes Twitter users: real-time event detection by social sensors | 2010 | 8 | 0.53 | WWW’10: Proceedings of the 19th international conference on World wide web [60] |

| Rank | Author | g-index | h-index | TC | NP | PY_start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alkhatib, Manar | 6 | 3 | 45 | 7 | 2019 |

| 2 | Wang, Yan | 4 | 4 | 93 | 4 | 2019 |

| 3 | El Barachi, May | 4 | 3 | 41 | 4 | 2020 |

| 4 | Resch, Bernd | 4 | 3 | 119 | 4 | 2018 |

| 5 | Hollander, Justin B. | 4 | 2 | 20 | 5 | 2017 |

| 6 | Mathew, Sujith | 4 | 2 | 28 | 4 | 2020 |

| 7 | Oroumchian, Farhad | 4 | 2 | 40 | 4 | 2019 |

| 8 | Sykora, Martin | 3 | 3 | 97 | 3 | 2017 |

| 9 | Varde, Aparna S. | 3 | 3 | 44 | 3 | 2018 |

| 10 | Shankardass, Ketan | 3 | 3 | 97 | 3 | 2017 |

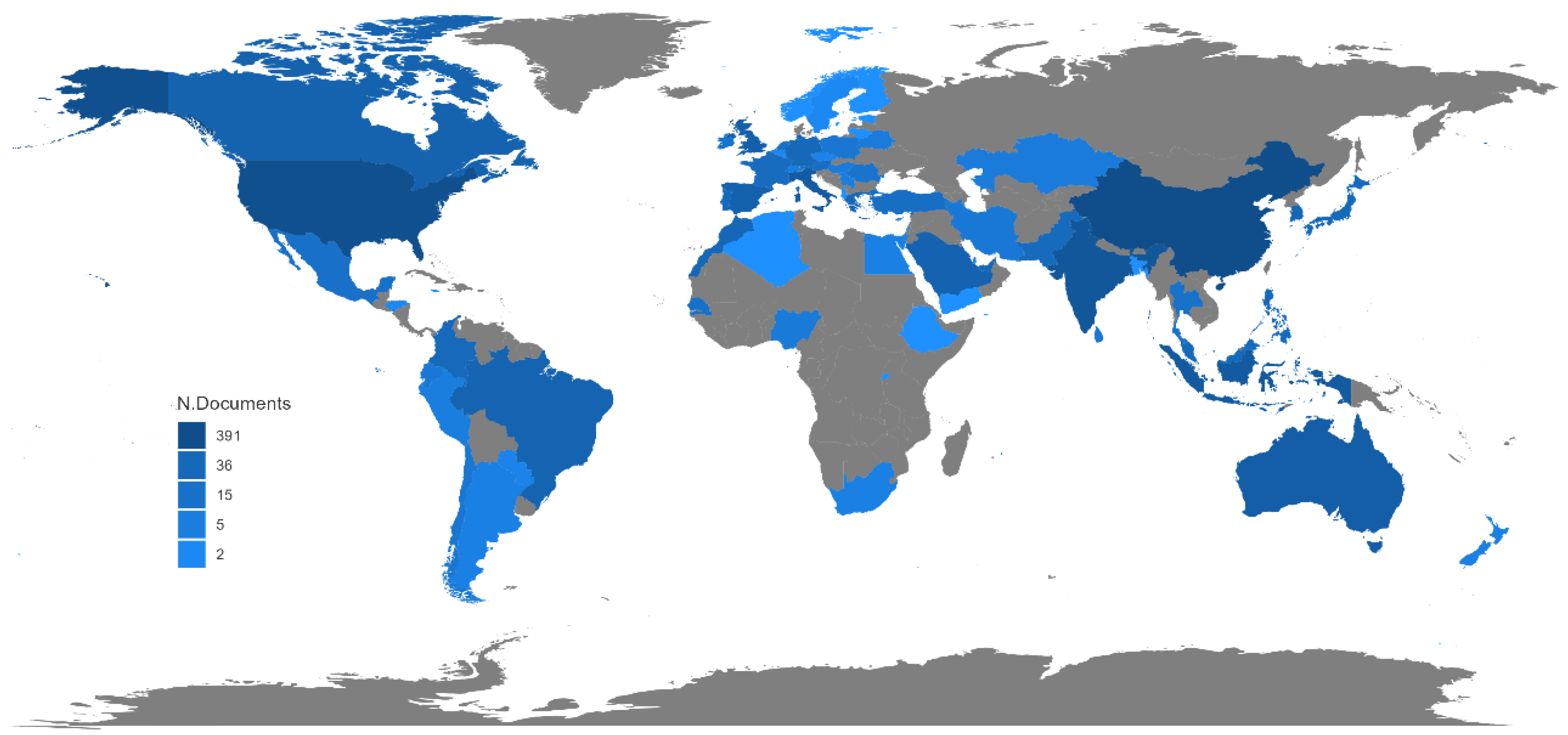

| Rank | Country (n = 58) | NA | SCP | MCP | Frequence | MCP Ratio | TC | AAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 80 | 57 | 23 | 0.110 | 0.287 | 322 | 4 |

| 2 | USA | 55 | 39 | 16 | 0.076 | 0.291 | 1060 | 19.3 |

| 3 | India | 26 | 25 | 1 | 0.036 | 0.038 | 70 | 2.7 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 15 | 8 | 7 | 0.021 | 0.467 | 158 | 10.5 |

| 5 | Australia | 13 | 11 | 2 | 0.018 | 0.154 | 97 | 7.5 |

| 6 | Spain | 13 | 7 | 6 | 0.018 | 0.462 | 374 | 28.8 |

| 7 | Italy | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 73 | 6.6 |

| 8 | Canada | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0.014 | 0.600 | 91 | 9.1 |

| 9 | Indonesia | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 35 | 3.5 |

| 10 | South Corea | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0.014 | 0.500 | 234 | 23.4 |

| Rank | Source | g-index | h-index | TC | NP | PY_start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 12 | 6 | 147 | 15 | 2018 |

| 2 | Cities | 10 | 6 | 146 | 10 | 2017 |

| 3 | Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) | 10 | 6 | 136 | 44 | 2012 |

| 4 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 7 | 4 | 55 | 14 | 2019 |

| 5 | Sustainable Cities and Society | 6 | 6 | 150 | 6 | 2019 |

| 6 | Journal of Medical Internet Research | 6 | 4 | 154 | 6 | 2019 |

| 7 | IEEE Access | 6 | 3 | 182 | 6 | 2017 |

| 8 | 2018 IEEE SmartWorld | 6 | 2 | 65 | 6 | 2018 |

| 9 | CEUR Workshop Proceedings | 5 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 2013 |

| 10 | ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information | 5 | 2 | 59 | 5 | 2018 |

| rank | Funding sponsor (n = 159) | NP | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Natural Science Foundation of China | 42 | 5.07 |

| 2 | National Science Foundation | 13 | 1.57 |

| 3 | Horizon 2020 Framework Program | 9 | 1.09 |

| 4 | European Commission | 8 | 0.97 |

| 5 | Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities | 7 | 0.84 |

| 6 | National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences | 7 | 0.84 |

| 7 | Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior | 6 | 0.72 |

| 8 | Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia | 6 | 0.72 |

| 9 | China Scholarship Council | 5 | 0.60 |

| 10 | Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council | 5 | 0.60 |

| T | Institution (n = 160) | Country | NP | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chinese Academy of Sciences | China | 9 | 1.96 |

| 2 | British University in Dubai | United Arab Emirates | 8 | 1.74 |

| 3 | University of Melbourne | Australia | 7 | 1.53 |

| 4 | Tongji University | China | 7 | 1.53 |

| 5 | University of Florida | USA | 6 | 1.31 |

| 6 | University of Toronto | Canada | 6 | 1.31 |

| 7 | Wuhan University | China | 6 | 1.31 |

| 8 | University of Wollongong in Dubai | United Arab Emirates | 6 | 1.31 |

| 9 | Ministry of Education China | China | 5 | 1.09 |

| 10 | The University of Hong Kong | China | 5 | 1.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.