1. Introduction

A key component of reaching global sustainability goals is electrifying mobility, especially in transportation sector, which continues to be a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Policy makers, businesses, and other stakeholders need to have a solid grasp of public opinion on this change as they navigate the opportunities and challenges of implementing electrification plans. The main objective of this study is to use state-of-the-art artificial intelligence tools, specifically natural language processing (NLP), to compare and assess public opinion on electrification in mobility across two distinct cultural, economic and policy-driven environments, China and Germany.

The study aims to create a data-driven method for understanding and contrasting public opinion, themes, and issues surrounding the electrification of transportation. This study intends to identify the disparities and similarities in public opinion by concentrating on two major economies, China and Germany, both of which are crucial participants in the global drive for electrification. This could reveal important information for global electrification strategies.

Specifically, this study uses NLP approaches and LLMs to process and analyze large scale social media data to identify sentiments (positive, negative or neutral) regarding electrification in mobility. Furthermore, the study aims to classify public discourse into meaningful themes such as infrastructure readiness, environmental impact, policy and regulation, technological progress, customer acceptance, and cost and affordability. By this way, the study enables comparative analysis between two countries which can be useful for policy makers, companies and other stakeholders for their evidence-based decision making processes (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

1.1. Electrification and NLP

Electrification in mobility has been a trend for some time now. The rapid improvements in technology and concerns regarding the climate change have been the major factors in this movement. Especially, the Net Zero agenda has been an effective motivation during the process. The transportation and mobility have great importance in this matter. A vital part of the larger endeavor to attain net zero greenhouse gas emissions is the global shift toward sustainable mobility. With electrification emerging as a key strategy for decarbonizing the sector, transportation has drawn increasing attention as a major contributor to global carbon emissions. About 23% of all energy-related CO

2 emissions in 2019 came from direct emissions from the transportation sector, which were about 8.9 GtCO

2eq/yr [

1]. Therefore, it is likely that the electrification efforts will continue by the governments.

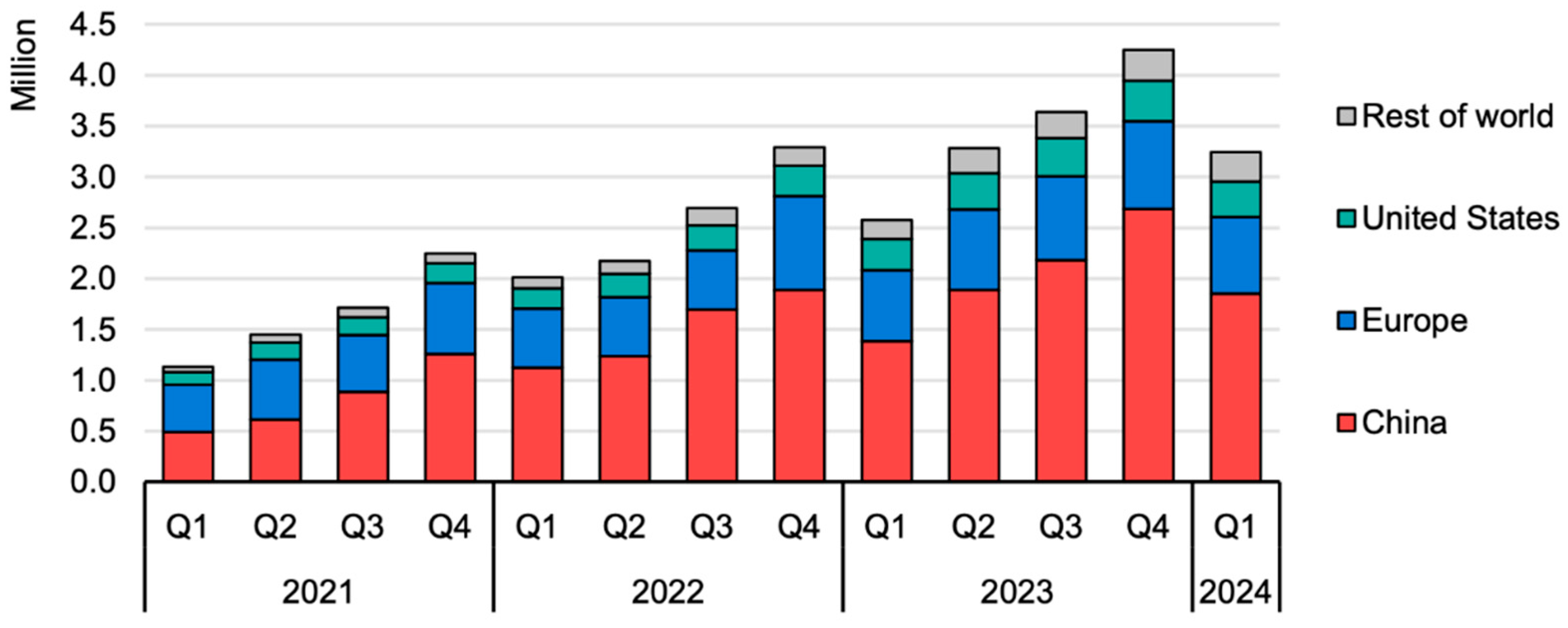

The growth in sales of electric cars in recent years, as shown in

Figure 1, suggests that China and Europe are two big players in this transition.

Furthermore, electrification in logistics, and various electrified micromobility modes of transport are reshaping the global transportation landscape, driven by concerns about climate change, energy sustainability, and technological innovation. China and Germany are two important participants in the electrification process. However, the electrification of mobility is not only a technological transition but also a societal one. Since societal resistance can stagnate progress, public engagement and acceptance are essential to the success of this transition.

Many researches have been conducted with different methods to understand the public opinion, and there is one common approach that has been widely used in order to achieve this goal, which are surveys. Survey-based studies are essential when it comes to understanding the reasoning, likings, aversions or generally the opinion of the public. However, these studies have some limitations such as sample size, homogeneity of the sample and number of responses, especially in a unique topic such as electrification in mobility which is still considered to be new in some countries. Therefore, a more comprehensive approach is required to analyze the issue, where people can honestly express their ideas and feelings and where the sample and the results can be generalized. The social media is the perfect area for this purpose. The number of users or content on any topic is enormous, the homogeneity is preserved and often, opinions that are shared publicly are genuine.

To be able to make such an analysis by using social media or online content as the data source, AI use is essential, NLP in particular. In the quickly changing world of today, developing strategic plans and adjusting to ever-evolving trends must be a continuous process of continuous monitoring, testing, assessment, implementation, and learning [

3]. The sentiment analysis (or opinion mining) and text-classification practices are capable of catching the continues processes of this evolving environment since these practices are performed by deep learning models. All areas of artificial intelligence, including text classification, have been impacted by the development of deep learning models. These techniques have become popular because they can model intricate features without requiring manual engineering, which eliminates some of the need for domain expertise [

4].

1.2. Background on Natural Language Processing

As the technology has been growing day by day, it has been rapidly changing the lives of people. The improvements and new use cases of AI models have broaden their potential. As of now, AI models are widely used for tremendous cases such as predictive operations, statistics, modern medicine, and even image or video generation since they are able to provide precise results in a short period of time. The idea of Artificial Intelligence is not new. Among his many significant scientific contributions, mathematician Alan Turing was the first to question whether machines are capable of thinking in 1950 and to propose the well-known Turing test, also known as the imitation game [

5].

NLP is one the use cases where various AI models have been training and showing promising results. Thanks to the very nature of these models where models learn continuously, they become more and more capable of communicating with people. Natural language processing is a branch of computer science, computational linguistics, and artificial intelligence that studies how computers and natural human languages interact [

6]. In essence, it makes it possible for machines to meaningfully and practically process, interpret, and produce human language. NLP has become a crucial tool for trying to gather insights from massive amounts of text as the volume of textual data generated every day keeps increasing.

There are a couple of traditional NLP tasks or concepts including but not limited to tokenization, lemmatization, Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging, and named entity recognition (NER), which NLP specialized and improved upon. The process of dividing a text into individual components, or tokens, which can be words, phrases, or even characters, is known as tokenization. Because it breaks up a continuous stream of text into digestible chunks that can be examined, this step is essential to natural language processing.

The lemmatization is basically the action of reducing the words to their base or root form as in dictionary. Because lemmatization reduces text variability, it can enhance the performance of NLP models. It's especially helpful for tasks like search algorithms, which require matching various word forms to the same base form.

POS tagging assigns each word in a text, a part of speech, such as an adjective, verb, and noun. For more complex text analysis tasks like sentiment analysis, this helps in comprehending the grammatical structure of sentences.

The NER is the process of identifying and classifying named entities in text into predefined categories like person names, organizations, locations, and dates. This helps in extracting structured information from unstructured text.

The traditional NLP models were mostly practiced on these kinds of tasks. For example, first put forth in the text retrieval domain problem for text document analysis, the bag-of-words (BoW) methodology was later modified for use in computer vision applications [

7]. Bag of Words model treats text as a collection of words without taking into account word order or grammar. Based on the frequency of words in the document in relation to the entire textual data, each document is transformed into a vector. Although BoW is simple to use and helpful for tasks like text classification, semantic information is lost because it disregards the contextual relationships between words.

The BoW model is expanded upon by Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), which weights words according to their significance. A word's importance goes up in direct proportion to how many times it occurs in the document, but it falls in direct proportion to how frequently it occurs in the textual data [

7]. By emphasizing distinctive words that are more instructive for the particular document, this method enhances text classification and retrieval task performance. But like BoW, TF-IDF is unable to record syntax or word order.

Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) reveals latent structures within the textual data by lowering the dimensionality of the BoW or TF-IDF representations. LSA captures hidden relationships that are not immediately obvious by grouping related words and documents into a lower-dimensional semantic space. However, LSA has a syntactic blindness issue, meaning it disregards sentence structure. When sentences contain words that are semantically similar but have different meanings, LSA is unable to discern between them [

8].

CNNs were initially created for image processing, but they have since been modified for text classification applications. Without considering the word order, they employ convolutional layers to identify local features in text, like phrases or patterns. Convolution is the most important feature of a CNN, it is the process of combining two other functions to create a third function [

9]. For tasks where local context is sufficient, CNNs are effective and efficient, however, they struggle to capture the overall semantic meaning, especially in longer texts.

Recurrent neural networks are appropriate for tasks like language modeling, text generation, and machine translation because they introduced the idea of memory to handle sequential data. In recurrent neural networks, the current step receives the output from the preceding step as an input. When it comes to word prediction, the inputs and outputs of other neural nets are not interdependent. The word that comes before it must be known to us beforehand [

9]. RNNs have trouble capturing long-term dependencies because of the vanishing gradient problem, even though they can handle variable-length sequences.

Although the cornerstone for text processing has been established by traditional NLP models, their shortcomings such as inability to handle context, capture long-term dependencies, and scale to large datasets have started the development of more sophisticated methods. Considering all these traditional NLP models and their different approaches, each model has one or more significant limitation. Thus, researchers and NLP enthusiasts have been developing more advanced models which are widely used today. The introduction of transformers plays a huge role in this shift, which will be presented in detail in the further. With the development of the Pre-Trained models, the NLP tasks have been improved significantly in terms of performance, flexibility and adaptability. Furthermore, new models are considerably better at handling multilingual data (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language). In today's globalized world, where comprehension of content in various languages and media is becoming more and more relevant, this ability is crucial.

A new era in natural language processing is marked by models that can comprehend and produce human language with high accuracy, thanks to the shift from conventional models to techniques like transformers. This shift is being driven by the need for models that are more context-aware, scalable and capable of handling the vast and complex volumes of data present in contemporary NLP applications. The impact of this change is demonstrated by notable performance gains on a range of NLP tasks, opening the door for further developments in the area.

1.3. Literature Review

As the aritifical intelligence has become more popular, it took the attention of many academics around the world. Various researches have been made about this intriguing technology and even more use cases had been presented where one or more AI based tools are used. On the other hand, use of these tools in sentiment analysis in mobility and transportation is rather new and still open to further studies, especially through social media.

Jena [

10] conducted a study which attempted to identify Indian consumers' attitudes, feelings, and thoughts regarding electric vehicles. This study's primary goal was to use Deep Learning techniques to extract opinions that would be useful to manufacturers, marketers, and prospective customers in order to decide which features to improve and which to advertise. The sentiment analysis of EV sentiment was conducted using a big data platform, given the nature of social media data. A couple of points were found as barriers for consumers towards the use of EVs as the result of the study.

Wandelt et al. [

11] reviews more than 130 papers regarding how LLMs can be integrated to intelligent transportation. They categorize the papers into five categories based on their primary contributions such as traffic, tourism, safety, autonomous driving, and others. In their findings, it is anticipated that LLMs will grow significantly in non-critical domains, especially in information retrieval and human–machine interaction applications. For instance, LLMs are probably going to be crucial to the tourism industry's use of virtual travel assistants and customized chatbots. Furthermore, LLMs have the ability to extract structured patterns and rules from sizable, unstructured datasets in traffic operations and management, providing insightful information for improving transportation systems.

A study carried out by Fontes et al. [

12] fills in the gaps in conventional transportation planning techniques by putting forward a deep learning framework for analyzing urban mobility using Twitter data. Three modules are integrated into the framework: preprocessing, data collection, and NLP driven analytics (using VADER for sentiment analysis, BERT for text classification with scalable travel-related dictionaries). The model showed strong performance in tests conducted in London, Melbourne, and New York, with average precisions of 0.80 for text classification and 0.77 for sentiment analysis. The framework provides actionable insights for resource management and policy evaluation by processing informal, georeferenced tweets in almost real-time, allowing for high-resolution identification of traffic events and public sentiment. This method overcomes the shortcomings of fragmented or context-specific approaches in previous studies and demonstrates the potential of social media as a dynamic, scalable data source for mobility intelligence.

Bakalos et al. [

13] examines public sentiment toward autonomous vehicles by analyzing Twitter and Reddit posts through a BERT-based machine learning framework. The results revealed predominantly positive perceptions however, the main issues causing negative sentiments were fear of mixed autonomous/human traffic environments, employment displacement, liability issues, and technophobia (e.g., cybersecurity risks). The study emphasizes how useful social media mining is for gathering broad, varied public opinions and providing policymakers with information to overcome adoption obstacles. It is recommended that future research make use of the framework's flexibility for multilingual and multi-class analyses in order to improve granularity and demographic correlation while abiding by privacy laws.

Furthermore, Metastasio et al. [

14] employs lexicometric analysis and examines Facebook and TikTok posts from 2022 to 2023 to investigate social representations of sustainable mobility. The results demonstrate social media's growing significance as a gauge of mobility culture trends, supporting the relevance of S. Moscovici's theory of social representations in this field. This demonstrates how social media analysis can be used to comprehend public opinion and new narratives during mobility transitions, offering theoretical and applied insights for further study.

Serna et al. [

15] offers a unique method for evaluating environmentally friendly transportation by employing deep learning techniques for sentiment analysis. In order to improve a large pretrained language model, XLM-RoBERTa, for sentiment classification, the authors use user-generated content from websites such as TripAdvisor to generate a manually annotated corpus of reviews pertaining to transportation. SentiWordNet is used in the study to compare the performance of this deep learning model with a conventional lexicon-based approach. It shows that the Transformer-based model performs noticeably better than the lexicon-based method, particularly when handling noisy data. The results imply that highly accurate sentiment analysis models can be produced by fine-tuning pretrained language models with a small amount of annotated data, providing policymakers with important information about how the public views sustainable transportation. By connecting sustainability analysis with advanced NLP techniques, this work advances the field and offers a solid foundation for further transportation and urban planning research.

The reviewed literature highlights the important NLP methods that is applied in this study and presents the increasing role of NLP and AI in analyzing public opinion as well as the evolving use cases of LLMs in mobility and transportation. Although NLP techniques have demonstrated effectiveness in sentiment analysis and thematic classification, there are still issues with handling regional differences, processing multilingual data, and maintaining model transparency. A comparative analysis of public opinion regarding electrification in mobility across various regions is lacking in current research, despite notable advancements. Furthermore, while sentiment analysis and thematic classification have been studied in the past, little research has used NLP to compare public discourse in a systematic way across linguistic context.

2. Methodology

The methodology begins with finding a suitable dataset to work on and preparing that dataset for an NLP based analysis. The dataset should be comprehensive enough to be able to generalize the results. In the end, the aim is to understand the opinion of the public of a nation. One important point that was considered for this study is making sure that the dataset is legal to use and there are no ethical issues. Since the subject dataset consists of social media posts, it might be copyright sensitive. However, the dataset used in this study is presented as suitable and open-source, as announced by the owner of the dataset which is presented in the appendices part of this study. The dataset is accessible through Hugging Face and it is released under MIT License [

16]. The MIT License is one of the most popular and lenient open-source licenses there is. It was initially developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and permits low-restricted use, modification, distribution, and even commercialization of software, datasets, and other intellectual property.

First, SQL console that is integrated on the Hugging Face was used to check the integrity of the dataset, in terms of the date range, total number of entries and number of entries in German and Chinese. Then, all the data preparation and analysis were carried out on Google Colab Pro version, due to the technical limitations of the free version such as limited RAM, GPU availability and disk space. Since the study is highly hardware demanding, Colab Pro was essential to be able to perform sentiment analysis and classification. The language used for the coding is Python programming language and several libraries are used in this study, such as Pandas, Torch, Transformers, Matplotlib and Seaborn.

As the next step, the suitable models were selected to carry out the analysis. Therefore, transformer-based AI models were chosen to perform sentiment analysis and thematic classification, allowing for an in-depth comparative study of public perception in both countries. The use of transformers is particularly advantageous due to their ability to process rich in context textual data and handle multilingual inputs effectively.

In the analysis step, to systematically assess public opinion regarding electrification in mobility across two nations with differences, a comparative framework is established. This study uses AI to categorize the data into major themes like infrastructure readiness, environmental impact, policy and regulation, technological progress, customer acceptance, and cost and affordability. It also analyzes sentiment polarity (positive, negative, and neutral). The study attempts to identify the commonalities and differences in public opinion regarding electric mobility by organizing the analysis around these predetermined categories. Finally, the extracted insights are visualized by graphs and tables to facilitate interpretation, highlighting key differences and similarities between two nations.

2.1. Dataset and Data Preparation

The effectiveness of an NLP study heavily relies on the quality and relevance of the dataset used. Therefore, finding or creating the best matching dataset for a specific research is one of the most important steps. The main dataset that was used as a starting point for this study was gathered from Hugging Face. Hugging Face is a new venture that was founded on the idea of using open source data and software. The democratization of NLP models built on the transformer architecture was, in fact, the catalyst for the NLP revolution. In addition to making these models publicly available, Hugging Face was a trailblazer in offering a convenient and user-friendly abstraction in the form of the Transformers library, which made it incredibly simple to consume and deduce these models [

17].

The dataset used in this study is created and shared by the company Exorde Labs, a startup founded in 2021 in Lyon, France with its primary goal being building a distributed network that can recognize and analyze the entire range of publicly available information on the Internet globally [

18]. Their large-scale dataset (total number of entries, or the rows, is 269.403.210 as shown in

Table 1) consists of social media posts from platforms such as Reddit, Twitter, BlueSky, YouTube etc. The dataset spans the period from November 14 to December 11, 2024 as in

Table 2, and includes multilingual data. It contains 122 languages in total [

16] and the number of entries in German is 4.618.554 while the number of entries in Chinese is 1.589.674 as shown in

Table 3. Given that public discourse on electrification in mobility is highly dynamic, social media provides a valuable source of real-time, unfiltered opinions, making it an ideal data source for this study.

In order to access the main dataset from Hugging Face, an access token was created from the website. Then, with the token, the dataset was retrieved using the load_dataset function from the datasets library, and the result was stored in a variable. A crucial aspect of this dataset loading process was the streaming=True argument. Enabling streaming ensured that the dataset was not loaded into memory all at once but was instead processed incrementally, piece by piece.

After the main dataset was loaded, the content was filtered by language with a lambda function which is a way to create small anonymous functions in Python, with language condition as “zh” for Chinese and “de” for German, in order to work on German and Chinese contents separately.

Then, a further filtering step was carried out which is filtering by defined keywords to be able to make an analysis regarding the electrification in mobility. A filtering function was created so that the new datasets would only include the content with defined keywords. The keywords used for filtering were split into two categories: general keywords about e-mobility and e-truck related keywords. The reason behind this was to see if the study can be done for an even more specific topic than electrification in mobility, which is electrification in heavy goods transportation. The list of the keywords is shown in

Table 4.

The aim after the filtering operation was to end up with two sub-datasets for both Germany and China, one to analyze the public opinion on general e-mobility in both countries and one for understanding the perception of the public regarding the e-trucks. However, after the dataset was filtered by the keywords, out of 4.618.554 posts in German, 7.822 rows were identified regarding electrification in mobility in the Germany dataset and there was no row, therefore no data for e-trucks. On the other hand, out of 1.589.674 posts in Chinese, 1.123 rows were gathered about e-mobility in the China dataset and 4 rows for e-trucks. Since there is not enough data to be analyzed in the topic of e-trucks, the study was only carried out for general e-mobility concept. Upon completion of data preparation operation, the datasets were set to be used for the sentiment analysis, classification and cross-analysis in the further steps.

2.2. Transformers

NLP has evolved significantly in recent years, with transformer models revolutionizing the field by offering state-of-the-art performance in various language tasks. Unlike traditional approaches, transformers leverage self-attention mechanisms to process text efficiently. Their ability to handle complex linguistic structures and multilingual text makes them particularly well suited for analyzing social media datasets. A number of important factors have contributed to transformers' success in NLP. They can effectively scale to large amounts of data because, first of all, they are highly parallelizable. Second, they are well-suited to NLP tasks where the input text's length can vary greatly because they can handle variable-length input sequences. Furthermore, transformers' efficiency in capturing long-range dependencies, scalability, and versatility have propelled them to the top of the leaderboard rankings for the majority of NLP tasks [

19].

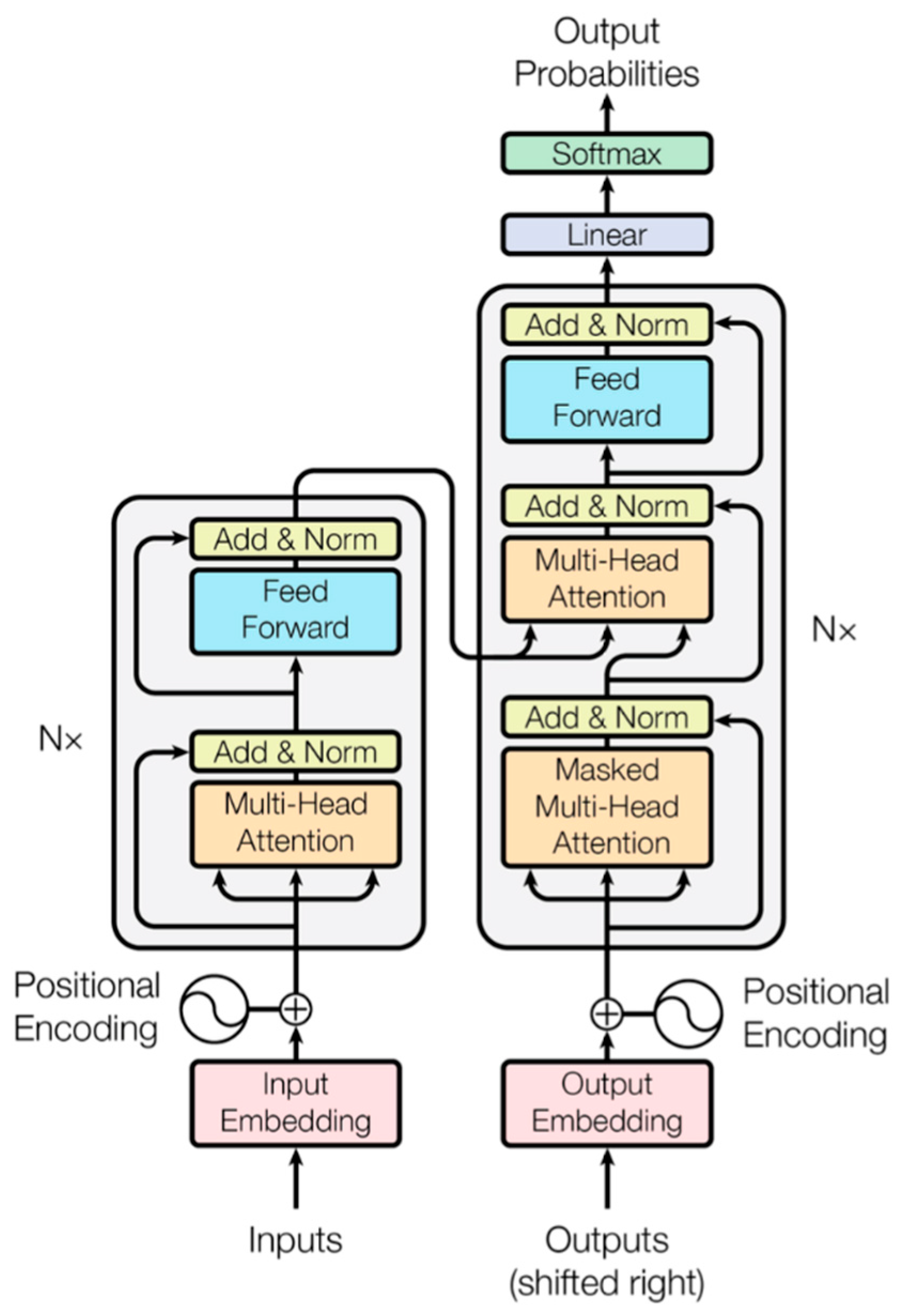

The model architecture of transformers is as shown in

Figure 2. The model is auto-regressive at every stage, using the previously produced symbols as extra input to create the subsequent one [

20]. Since its auto-regressive behavior, the first transformer models were considered as unidirectional such as GPT and GPT-2 from OpenAI. Later, the approach was improved and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) was introduced by Google. This model enables a better context extractor for reasoning tasks by fusing the left and right context of a sentence, resulting in a bidirectional representation [

21].

Despite their advantages, transformers come with high computational costs, which can be a major constraint in practical applications. To manage these computational demands efficiently, Google Colab Pro was used, providing access to high-performance GPUs that significantly improved processing speed and model execution. This allowed for smoother handling of large datasets without the need for extensive local hardware.

Another key limitation is model size and sequence length constraints. Most transformer models, including BERT, impose a maximum sequence length of 512 tokens, which means any text exceeding this length is truncated. In this study, no additional text-splitting was applied, meaning that longer posts were automatically cut off beyond the token limit.

To be able to use the transformers in the research, first they needed to be installed on the Google Colab notebooks created for both the Germany and China datasets. A line of code using pip command, which is the standard package installer for Python, was written to install a library called transformers, which is a powerful and popular open-source library developed by Hugging Face.

As the next step, two key components from the Hugging Face transformers library were imported, AutoTokenizer and AutoModelForSequenceClassification. The purpose of AutoTokenizer is to prepare text data for input to a transformer model since the transformer models do not directly understand raw text therefore, they require numerical representations of words and sentences. On the other hand, AutoModelForSquenceClassification class provides a convenient way to load and use pre-trained transformer models fine-tuned for NLP tasks such as sentiment analysis.

In summary, transformers were selected for this study due to their ability to handle long texts, capture contextual meaning, process multiple languages, and operate efficiently at scale. While computational costs and model limitations were considered, the use of pre-trained models and cloud-based resources helped address these challenges, making transformers the optimal choice for sentiment analysis and zero-shot classification in this research.

2.3. Sentiment Analysis

In the context of examining textual data from a variety of sources, such as social media, news articles, and online forums, sentiment analysis has emerged as a popular natural language processing method for determining public opinion in the recent years. Sentiment analysis helps with the identification of trends, public opinion, and emotional responses to particular subjects by classifying text into segments such as positive, negative and neutral or scaling these as numbers. Sentiment analysis is essential to this study in order to assess how Chinese and German societies view the electrification of mobility.

In this study, sentiment analysis was set up and performed on text data from Germany and China datasets separately, using a pre-trained model from Hugging Face accessed through the transformers library, which is called “tabularisai/multilingual-sentiment-analysis”. The base model of this multilingual model is Distilbert, that contains 12 heads, 6 layers, and 768 dimensions, for a total of 134M parameters (as opposed to 177M for mBERT-base). This model is twice as fast as mBERT-base on average [

22]. Tabularisai/multilingual-sentiment-analysis supports 22 languages including German and Chinese. Therefore, the same model was used during the sentiment analysis for both contents.

In order to successfully make a sentiment analysis, the coding objective was to process textual data, analyze sentiment, and return a sentiment score ranging between very negative and very positive. Therefore, a dictionary called sentiment_map was created to map the numerical outputs (ranging from 0 to 4) produced by the model to readable sentiment labels such as “Very Negative”, “Negative”, “Neutral”, “Positive”, and “Very Positive”, as instructed in the model description section on Hugging Face (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, code clarification purposes).

The first step involved importing necessary libraries. The transformers library provided AutoTokenizer and AutoModelForSequenceClassification, which facilitated text tokenization and sentiment classification using a transformer model. Additionally, the PyTorch library (torch) was imported, which enabled tensor operations and model inference.

Then, a prediction function was defined to process input texts in manageable batches, thereby optimizing memory usage and processing time. The sentiment prediction function was applied to the datasets. The predicted sentiment for each text was determined by selecting the label with the highest probability, and these predictions were then mapped to their corresponding sentiment labels using the sentiment_map dictionary. All predictions were collected into a list that was returned once the entire dataset had been processed (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, code clarification purposes).

This implementation was particularly useful for large-scale sentiment analysis of social media and online discussions, as it allowed for efficient processing of multilingual data. Additionally, the approach was scalable, as it supported batch processing, enabling the analysis of millions of text entries with high computational efficiency.

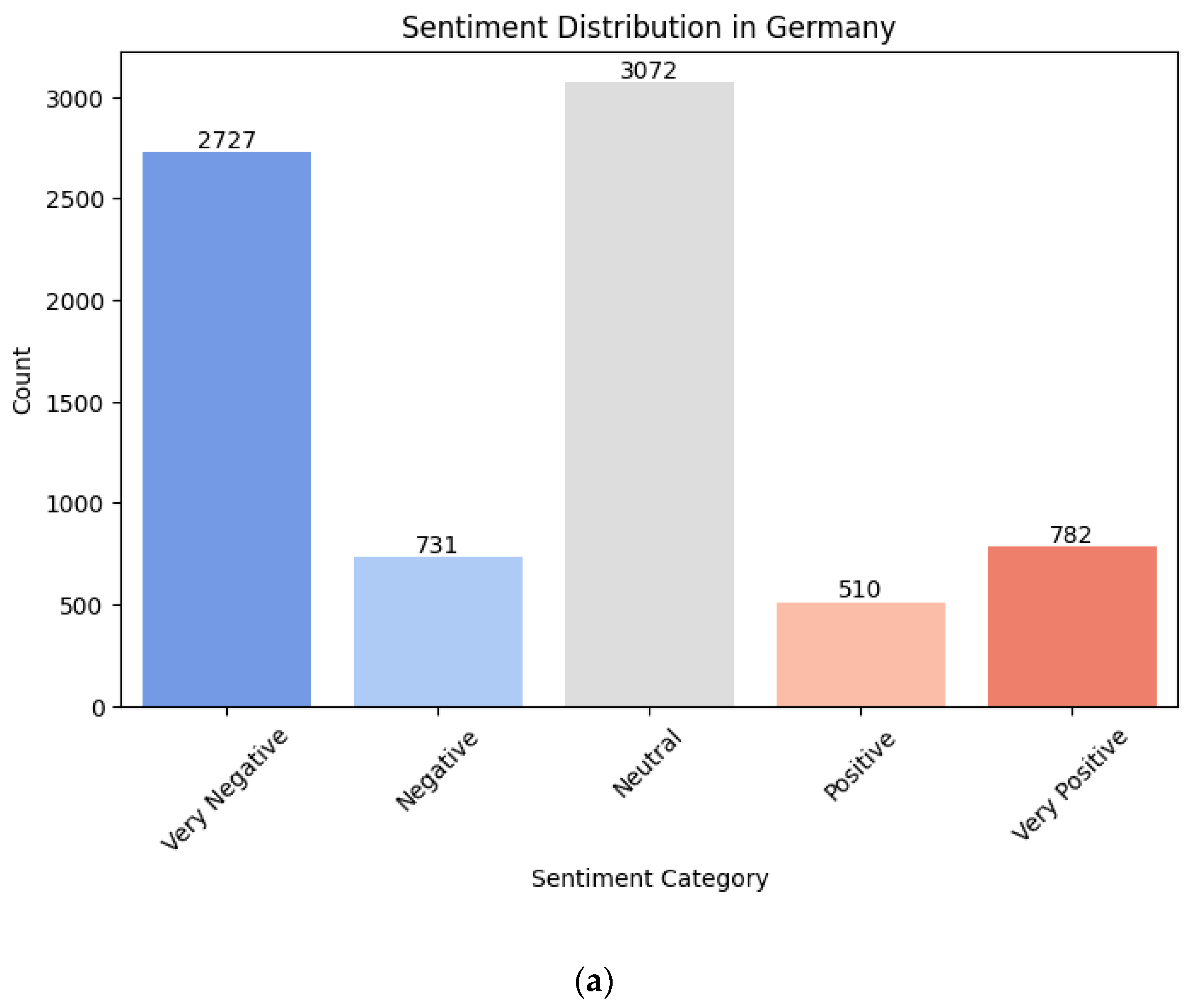

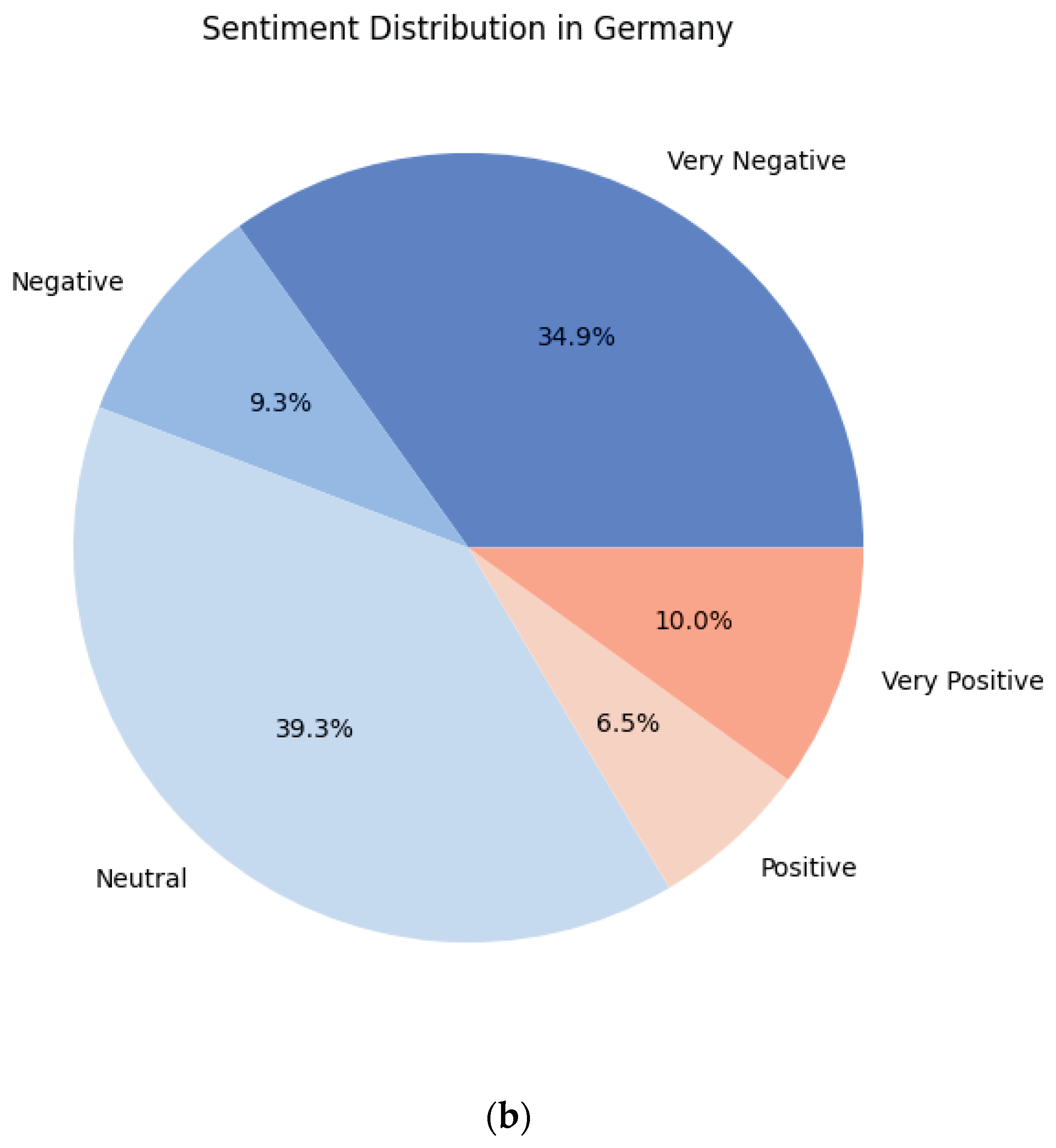

To visualize the distribution of the sentiment scores, a function was then defined that took a Pandas DataFrame as input. The function was designed to generate a bar plot representing the frequency of different sentiment categories in the dataset. Additionally, the sentiment distribution was also presented as a pie-chart to see the share of each sentiment group for better understanding (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, code clarification purposes).

Afterwards, a function named plot_sentiment_trend_normalized, was designed to visualize how sentiment varied over time within a given dataset. After grouping and counting, the function normalized the data by calculating the percentage of posts for each sentiment category on a daily basis. The normalization step was essential for comparing sentiment trends over time, regardless of fluctuations in the total number of posts per day (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, code clarification purposes). This function, which generated a visual representation of normalized sentiment trends over time, was able to provide valuable insights into how public sentiment evolved day by day, offering a nuanced view of the discussions surrounding mobility electrification. It may help to identify trends in a dataset in the case of a major event occurrence or how the public would react to that specific case.

With these insights in place, the study will move forward into the next phase of analysis, where the focus would shift towards thematic categorizations and cross-analysis to be able to make successful comparisons.

2.4. Zero-Shot Classification

Similar to topic labeling or sentiment analysis, text classification is crucial for both economics and research. In a variety of fields, such as market research, automated content moderation, and customer feedback analysis, it aids people to glean insightful information from textual data and make well-informed decisions [

23]. To train supervised models, conventional text classification techniques in natural language processing usually need major, labeled datasets. Nevertheless, obtaining labaled data can be expensive, time-consuming and domain-specific. The zero-shot classification overcomes this issue by allowing models to classify text into preset categories without requiring prior training on labeled examples. Instead, these models rely on pre-trained language representations and can make predictions based on textual descriptions of the target categories. Zero-shot classification seeks to classify data without explicit examples of particular classes during training. This provides a way around the drawbacks of text classification using data-intensive deep learning models [

24].

In this study, zero-shot classification was applied to categorize social media discussions related to Germany and China into key thematic areas, including Infrastructure Readiness, Environmental Impact, Policy and Regulation, Technological Advancement, Consumer Adoption, and Cost and Affordability. The classification results provided deeper insights into the dominant narratives and concerns surrounding electric mobility in each country.

To start the classification operation, first the necessary libraries were imported such as Pandas, Matplotlib, Torch, Transformers and Pipeline module. Then the filtered and sentiment scores added datasets for Germany and China were loaded to the Colab notebook. To carry out the classification in the datasets, two different models were used. For the Germany dataset, morit/german_xlm_xnli model [

25] was selected. This model is specifically pre-trained for zero-shot classification and German language understanding and natural language inference. Hosted on the Hugging Face Model Hub, it was suitable for identifying relationships between input text and candidate category labels, making it a suitable choice for classifying social media discourse related to electrification in mobility within Germany.

Likewise, morit/chinese_xlm_xnli model [

26] was selected for China dataset, which has the same capabilities as the previous model however specialized in Chinese language. Then the categories were defined for both languages, as shown in

Table 5.

The function “classify_theme” was defined to take a single argument, text, which represented the input that needed classification. At the core of the function, the classification process was carried out using the classifier object, which had been previously defined as a zero-shot classification pipeline. This classifier analyzed the input text and attempted to assign it to one of the predefined themes. The function called the classifier with the candidate_labels parameter set to categories, instructing the model to consider the predefined themes as possible labels for classification. If the classification was successful, the function extracted the most probable theme from the result and returned it. Then, the function was applied to the “original_text” column of the datasets and stored the classification results in a new column called “theme”.

Once the classification was completed, a bar plot was created for each dataset to visualize the distribution of different themes within. The process began with the creation of a translation dictionary named theme_translation, which served as a lookup table mapping each German and Chinese themes to their corresponding English equivalent. This dictionary ensured that all thematic labels were consistently translated before further analysis.

Following the translation, a function calculated the frequency of each unique theme, then generated a bar chart to display these counts, and finally annotated the bars for better readability. The code computed the distribution of themes, created a bar plot to represent the data visually, annotated the bars for clarity, and applied formatting adjustments to ensure the plot was easy to interpret. This visualization provided an insightful overview of the most frequently occurring themes in the dataset. With the successful visualization of the theme distribution, the analysis gained a clearer understanding of the most frequently occurring themes in the datasets.

2.5. Cross Analysis

With the sentiment analysis and theme classification completed for both Germany and China, the next phase of the study involved conducting a cross analysis to compare public discussions on electrification in mobility between the two regions. This step was essential for identifying similarities, differences, and underlying patterns in how people perceive and discuss mobility electrification in these two distinct contexts. By examining the sentimental and thematic distributions, the study aimed to uncover key insights into factors influencing public opinion in each region.

After loading the datasets on the same Colab notebook, which now have sentiment score and theme columns for both German and Chinese contents, first step was to identify the sentiments in each theme for the countries separately. The process began by grouping the datasets based on themes and sentiment scores. The groupby() function was applied to calculate the frequency of each theme-sentiment combination within the dataset.

Once the data was grouped, the unstack() function was used to restructure the grouped data into a tabular format. In this format, themes were represented as rows, sentiment labels as columns, and the cell values indicated the number of occurrences. After structuring the data, the sentiment columns were reordered using reindex() to follow a predefined order which is very negative, negative, neutral, positive and very positive.

In the next step, to be able to make a comparison side by side, a code was used to create a stacked bar chart that compared the distribution of sentiments across different themes for Germany and China. Two new DataFrames were created, one for Germany and one for China, by selecting only the theme and sentiment columns from the original datasets. A new column labeled ‘Country’ was then added to each DataFrame, assigning the value ‘Germany’ to the German data and ‘China’ to the Chinese data. These separate DataFrames were subsequently combined into a single DataFrame called df_combined using the pd.concat() function, with the index reset to ensure a continuous sequence of rows (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, code clarification purposes).

Once the data was prepared, the next step involved aggregating the data to capture the frequency of sentiment occurrences within each theme for both countries. The data was grouped by theme, country and sentiment scores using the groupby() function, and the size of each group was calculated.

Additionally, a sorted list of unique themes was extracted from the combined DataFrame, which was later used to label the x-axis of the bar chart. The code then iterated over each theme and plotted two sets of stacked bars, one for Germany and one for China, representing the sentiment distribution for each theme. For each theme, the individual sentiment counts were plotted as stacked segments on the bar, with the bottom parameter ensuring that the segments were correctly accumulated.

However, since the number of contents for German and Chinese are different from each other, it was hard to visualize the comparison. Therefore, instead of using absolute values, a new plot was created by a pivot table calculating the percentage distribution of sentiments within each (theme, country) pair. This ensured that themes with varying numbers of posts remain comparable, eliminating biases caused by differences in data volume between Germany and China.

3. Results

The results of these analyses are presented in this section. First, an overview of sentiment distribution across both countries is presented. Secondly, thematic trends are examined to determine which topics dominate discussions in each country. Finally, a comparative assessment of these findings is provided to contextualize the differences and similarities observed in the discourse.

Figure 3 shows the sentiment score distribution in Germany regarding the electrification in general mobility. As seen in the results, only a small fraction of the total content are positive or very positive, 6.5% and 10.0% respectively. The sentiment mostly shows itself as neutral and very negative in German social media contents, 39.3% and 34.9% to be specific.

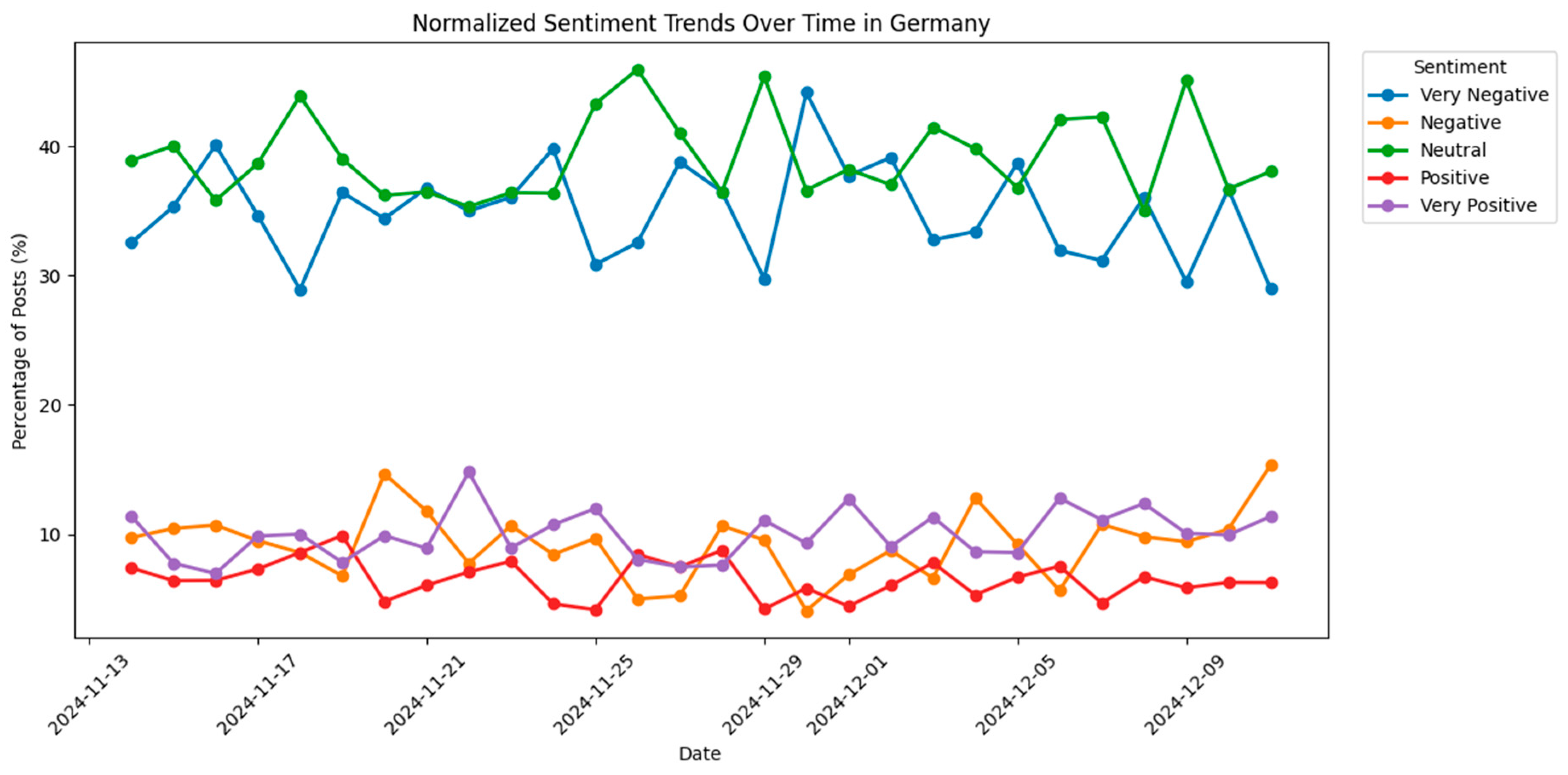

The sentiment trends over time is shown in

Figure 4. To see the trends change over time might be crucial on any topic since it may help to understand the effects of an event such as a new policy, a technological development or a new product on the market. There are some leaping points in time in the sentiment trends however no considerable effects can be identified in the limited time period such as one month.

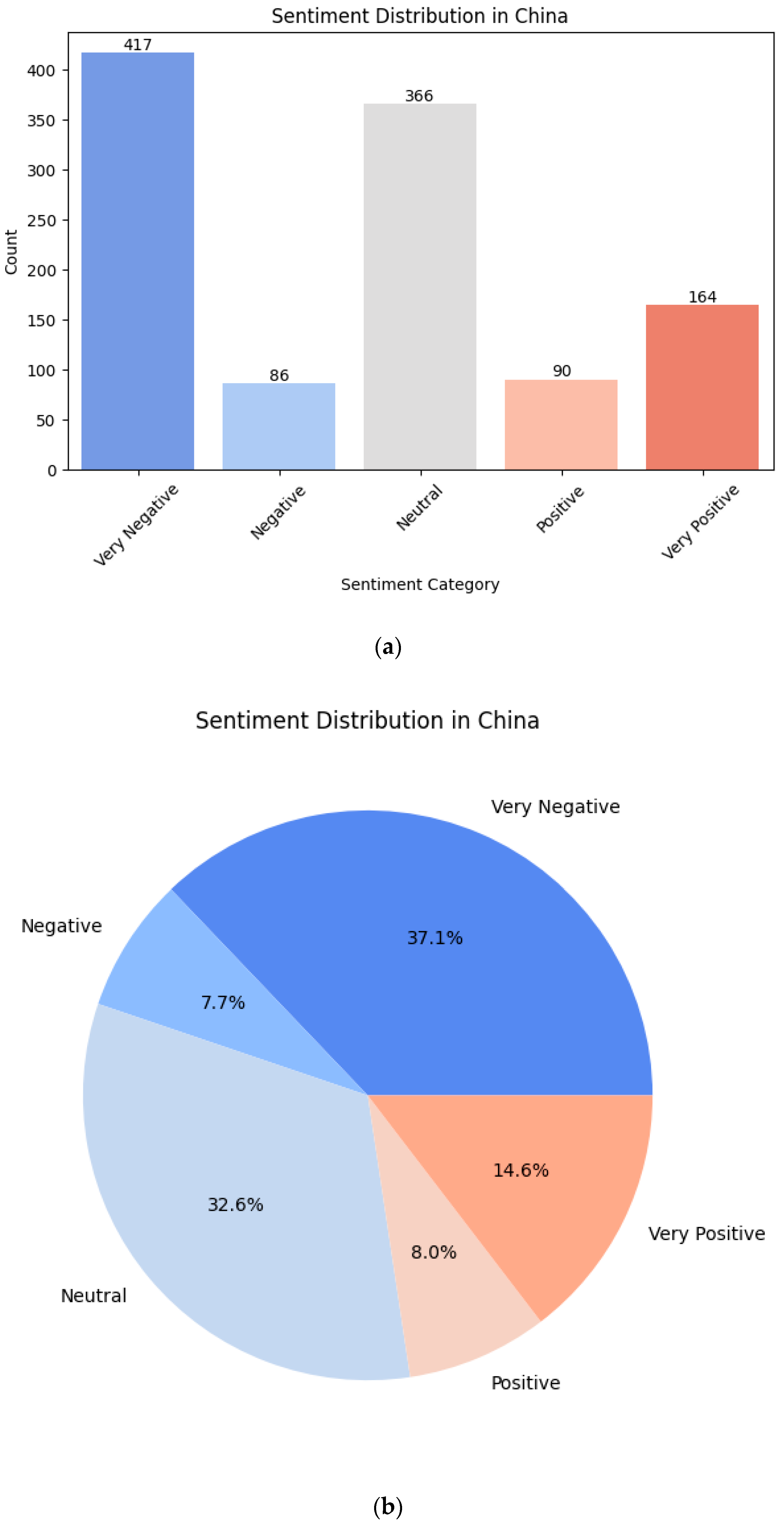

Figure 5 shows the sentiment score distribution in China regarding the electrification in general mobility. Similar to German sentiment distribution in general e-mobility dataset, the sentiment is mostly neutral or very negative for China dataset as well, 32.6% and 37.1% of total content respectively. 14.6% of the total posts are identified as very positive and 8.0% as positive.

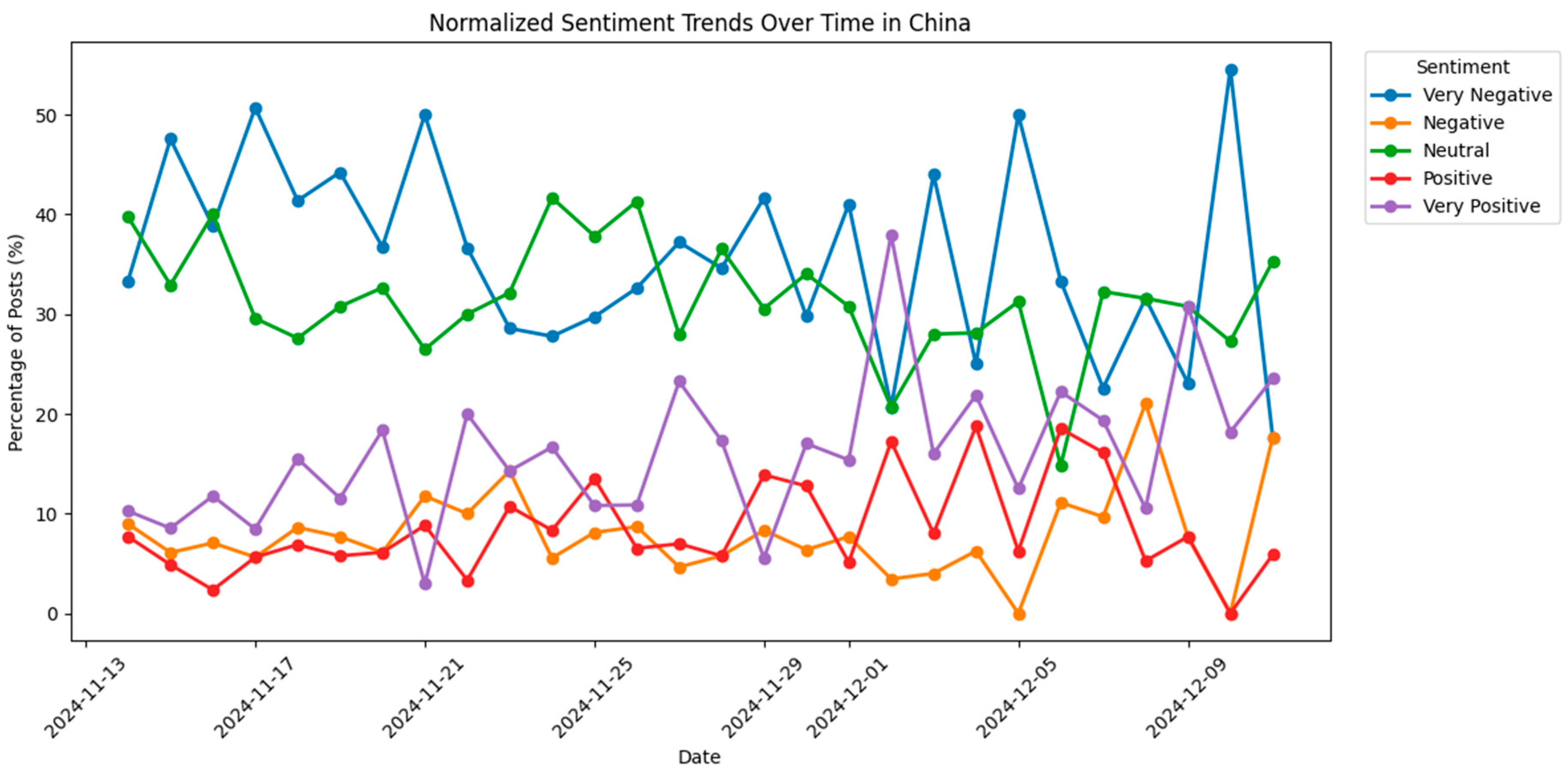

Figure 6 shows the sentiment trends over time in China about electrification in general mobility. As per the results, no clear trend can be identified however a strong increase in December in very positive perception may suggest a major event that caused a change in people opinion towards general e-mobility.

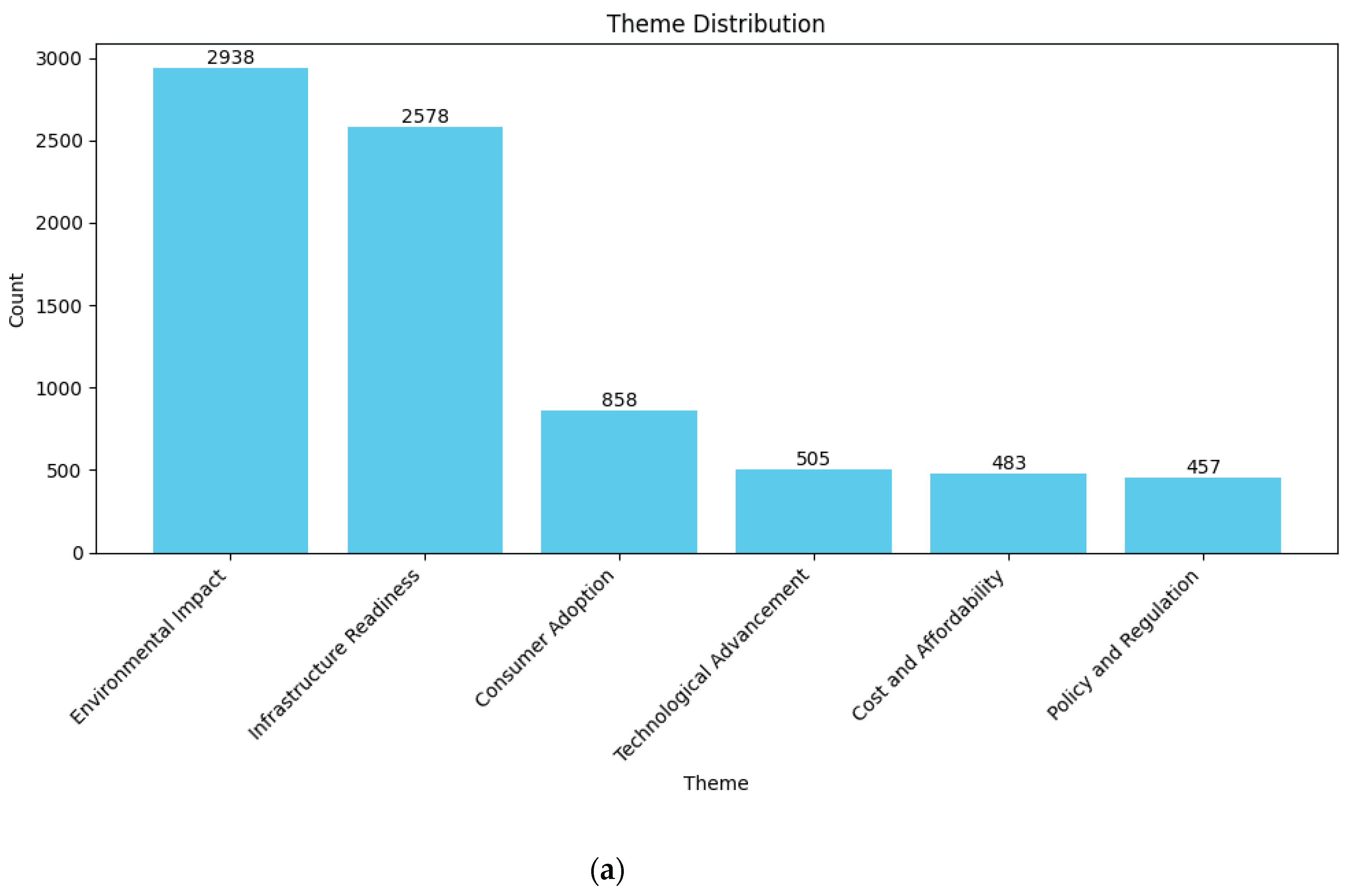

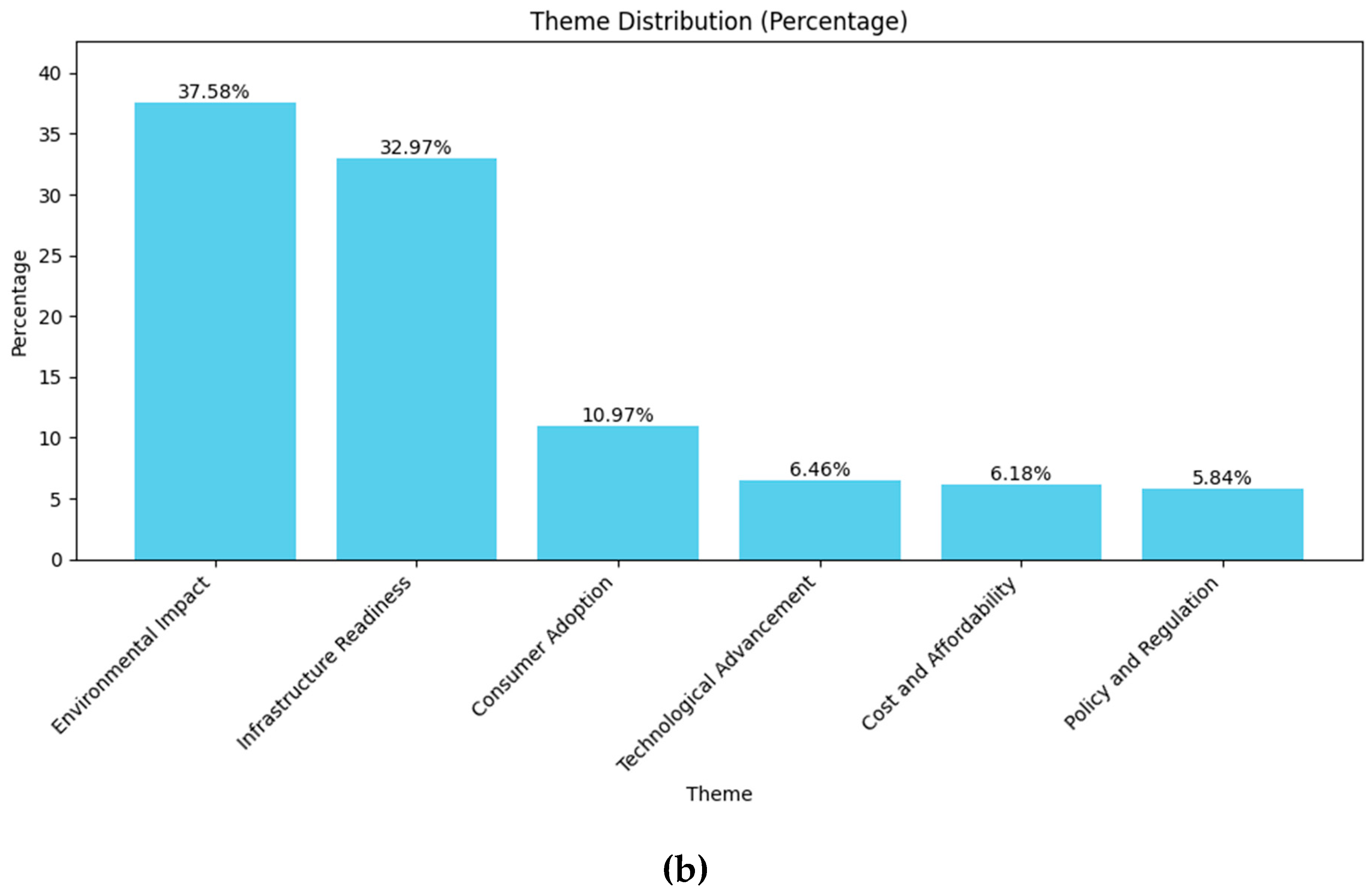

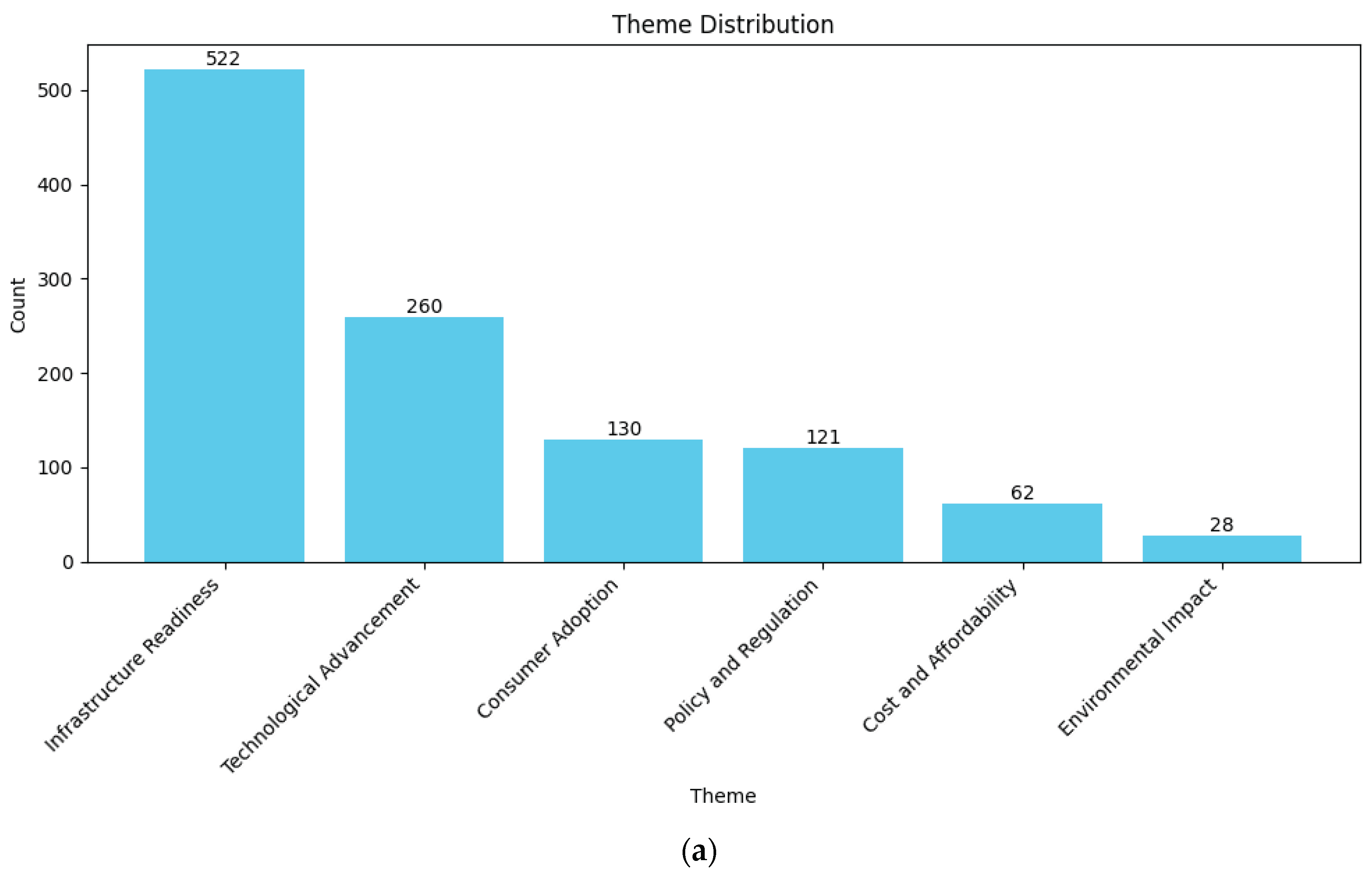

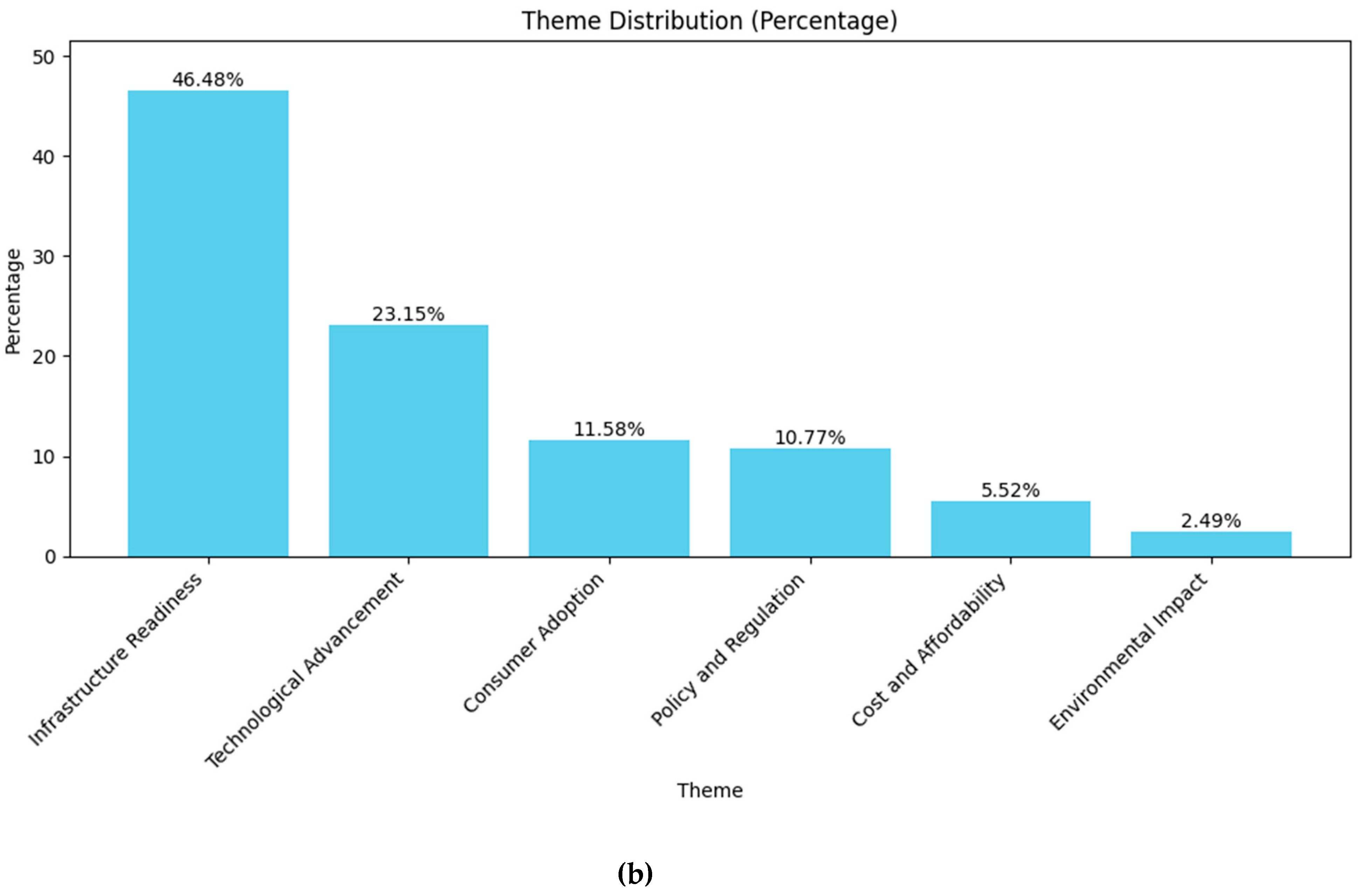

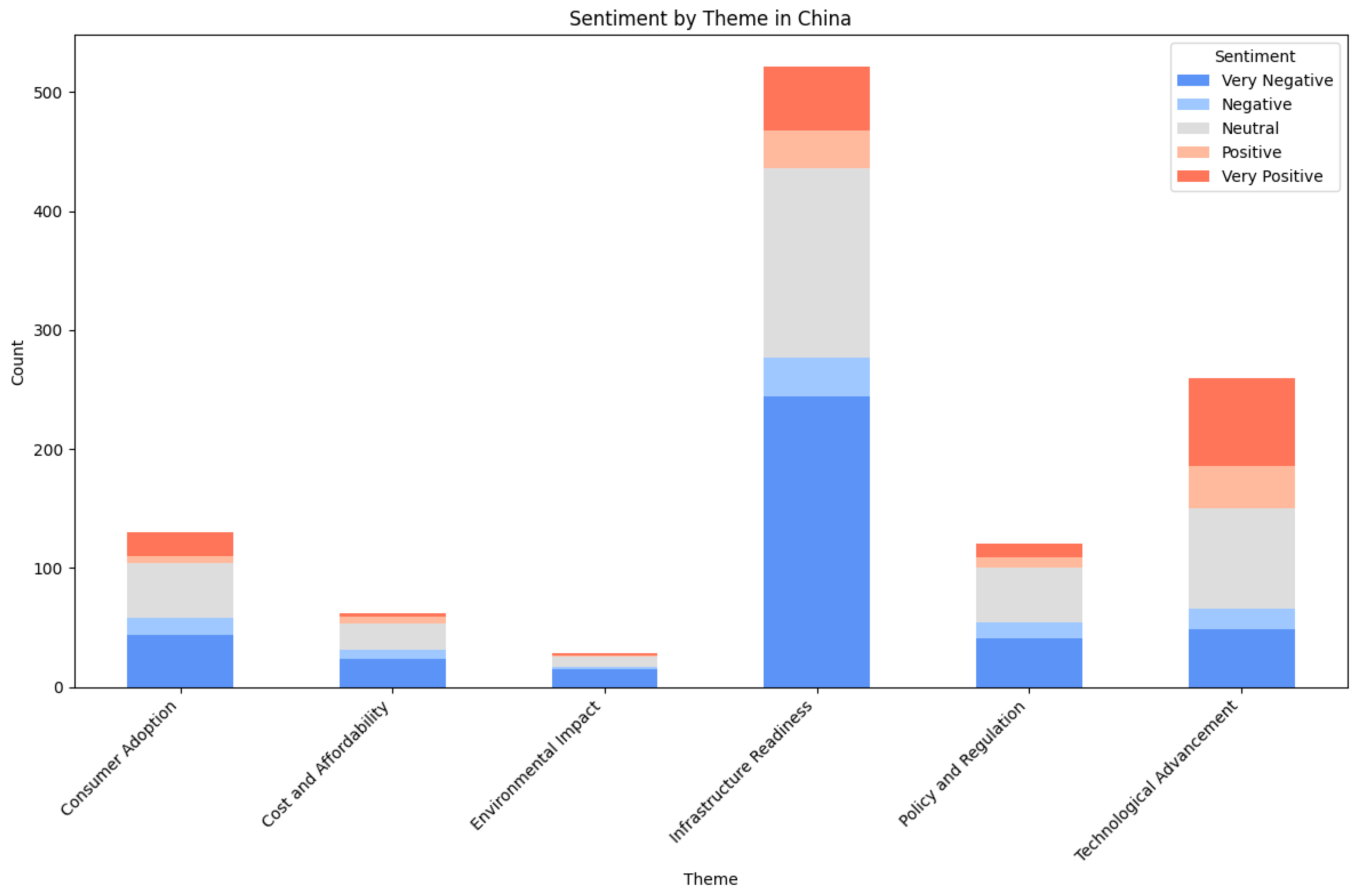

The results of categorization (zero-shot classification) for Germany and China are shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

As the results show in German dataset, environmental impact (37.58%) and infrastructure readiness (32.97%) are two major themes in German dataset. The consumer adoption (10.97%) topic follows these themes afterwards, and the remaining themes such as technological advancement (6.46%), cost and affordability (6.18%) and policy and regulation (5.84%) have almost the same relevancy level. This may suggest that e-mobility developments come with environmental concerns and the main pain point is infrastructure readiness.

On the other hand, the environmental impact category is almost none-present for China dataset, which covers only 2.49% of the contents. The infrastructure readiness category is highest in counts (46.48%) and it is followed by technological advancement theme (23.15%). The consumer adoption (11.58%) and policy and regulation (10.77%) have almost the same amount in distribution and cost and affordability theme (5.52%) is considerably low. This may suggest that the Chinese society sees the e-mobility initiatives as a fascinating technological advancement movement and their concern mostly is the infrastructure readiness as the environmental impact has low relevancy on the topic.

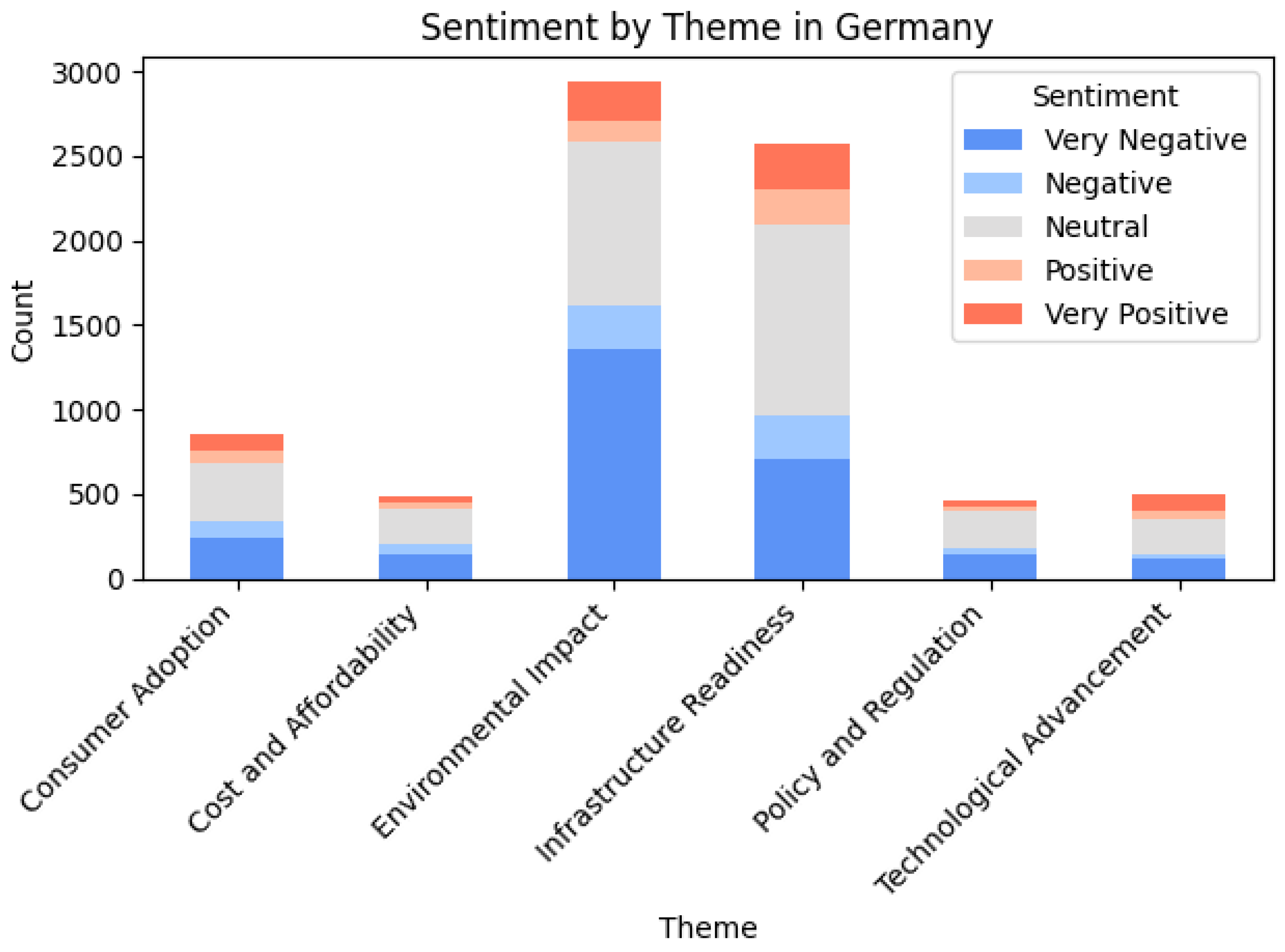

Now that the results for sentiment analysis and zero-shot classification are presented, the outcomes of cross-analysis for Germany are as in

Figure 9 and

Table 6.

The sentiment distribution in themes in Germany dataset reveals a strong polarization, particularly regarding environmental impact and infrastructure readiness. Discussions about environmental impact are overwhelmingly negative, with a high number of very negative mentions, suggesting significant concerns about the real sustainability of electric mobility. Similarly, infrastructure readiness is met with widespread criticism, though there is relatively higher portion of positive mentions, indicating some optimism about future developments. Consumer adoption and cost and affordability are also predominantly viewed through a negative lens, with affordability concerns receiving a very few positive mentions, reinforcing the perception that cost remains a major barrier to adoption. Policy and regulation is largely met with neutral or negative sentiment, suggesting a degree of dissatisfaction with government actions in this space. In contrast, technological advancement has more balanced sentiment distribution and notable share of positive mentions, indicating there is confidence in the progress of electric vehicle technology. Yet still, it is one of the least mentioned themes in the dataset.

The sentiment distribution in themes in China dataset presents a different picture compared to Germany. Infrastructure readiness stands out as the most discussed theme, with a significant number of very negative mentions, indicating concerns about the adequacy of charging networks and related infrastructure. However, it also has notable share of positive sentiment, suggesting recognition of ongoing improvements. Technological advancement is the most positively perceived theme, with a high proportion of positive and very positive mentions, reflecting strong confidence in China’s progress in electric vehicle technology. Consumer adoption and cost and affordability lean toward neutral and very negative sentiment, implying that while challenges exist, they may not be perceived as major barriers. Similar distribution can be found in policy and regulation theme, suggesting that while some policies are met with approval, there is also skepticism about their implementation. Environmental impact, in contrast to Germany, is the least contentious theme, with very few mentions overall and relatively negative sentiment distribution, which may indicate lower public concern however addressing the environmental challenges of electric mobility by the public at the same time.

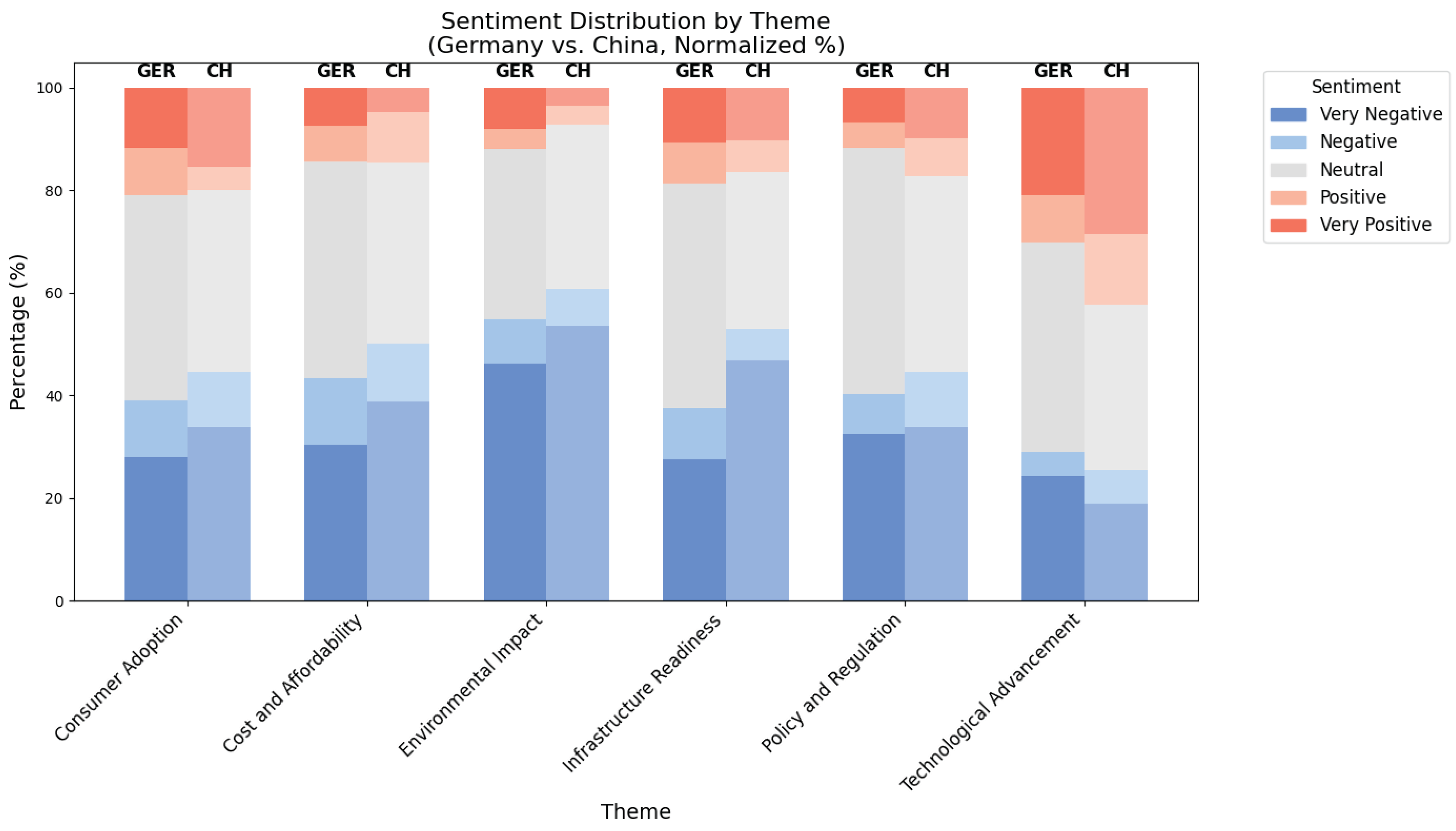

The visualization shown in

Figure 11 is presenting the percentages of the distribution, in order to eliminate the possible misinterpretations caused by the number of contents in both datasets. For the consumer adoption theme, the results seem similar, and the reason might be that the pain points of electrification in mobility are more global, rather than cultural or area specific. The cost and affordability theme shows similarities between two countries, with slight difference in negative sentiments. In the environmental impact theme, the sentiment falls mostly negative in China dataset with similar results in Germany dataset however, the percentage of positive sentiments seem lower in China dataset. More interestingly, although China is known for its well-developed e-mobility infrastructure, Germany dataset shows more neutral side in the sentiments and a negative perception is higher in China dataset. The policy and regulation shows similar results in both countries, with neutral sentiments have higher portion in Germany dataset. For the technological advancement theme, both datasets show considerably higher positive sentiment compared to other categories’ distributions.

When analyzing the sentiment distribution in

Figure 11, it is crucial to consider the relative importance of each theme within the overall dataset. While some themes may exhibit strong negative sentiment, their actual impact on public discourse depends on how frequently they are discussed. For instance, in China, the environmental impact theme has a high portion of negative sentiment. However, since it represents only a small percentage of the total discussions (2.49%), its influence on the broader conversation is limited. In contrast, in Germany, environmental concerns are not only predominantly negative but also a significant topic of discussion (37.58%).

Another pattern emerges in infrastructure readiness theme. In China, this theme accounts for a substantial portion of discussions (46.48%) and is strongly negative. This suggests that infrastructure challenges are a major barrier to electrification and a widely recognized issue among the public. In Germany, infrastructure is also frequently discussed topic (32.97%) but has a more balanced sentiment distribution. While concerns exist, they are not as overwhelmingly negative as in China, suggesting that the German public may see the infrastructure issues as challenges rather than major obstacles (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

The technological advancement theme further illustrates the differences in discourse between the two countries. In China, this theme is both widely discussed (23.15%) and highly polarized, with strong positive opinions. However, in Germany, it is discussed considerably less (6.46%) and the sentiment is more neutral, indicating that the topic is either less controversial or not a major point of public debate.

Another striking difference between the countries is the tendency toward neutrality. In Germany, a significant portion of discussions across most of the themes falls into the neutral category, indicating that people are more reserved in expressing either strong approval or disapproval of electrification related topics. On the other hand, in China, the public perception appears more polarized, as either strong support or strong opposition. This suggests that electrification is a more emotionally charged topic in China, whereas in Germany, the discussion tends to be more measured and analytical (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

4. Discussions

The findings of this study align with existing literature on mobility electrification, further reinforcing key trends observed in both Germany and China. One of the fundamental drivers behind China’s strong push toward electrification is the recognition by Chinese policy makers and firms. Chinese companies and policy makers saw the shift in technology from internal combustion engine cars to electric vehicles as a chance to catch up to and surpass the world's top automotive and related industries, which up until now had been more competitive and technologically advanced than China's sector [

27]. Rather than competing within the well-established traditional automotive market, China has leveraged this transition to position itself as a leader in EV technology, battery innovation and large-scale infrastructure development. This strategic approach explains why public discussions in China place significant emphasis on technological advancements, reflecting confidence in the nation’s ability to lead in the global electrification race. Upon checking the content of some of the posts, public perception highlights China’s progress in clean energy policies, government subsidies and large-scale production. However, there are some concerns about overproduction, economic sustainability, and government intervention in market dynamics, which shows an awareness of potential economic challenges regarding the EV growth.

In contrast, European consumers, including those in Germany, tend to approach EV adoption with more practical concerns, particularly regarding affordability and charging infrastructure. European consumers need well-positioned charging stations and a fair car price to help them make a purchase [

28]. This aligns with the sentiment analysis results of this study, where infrastructure readiness emerged as a dominant theme in German discussions. Public concerns about whether the current charging network can support the widespread EV adoption, inconsistent charging speeds and range anxiety play a significant role in shaping consumer sentiment. Additionally, environmental concerns remain an important topic as there is ongoing debate over the true sustainability of EVs. Addressing these concerns through improved charging infrastructure and open communication on environmental benefits of electrification could positively influence public perception in Germany.

From an industry perspective, the role of dealerships and manufacturers in shaping consumer perceptions is crucial. Dealerships ought to emphasize the EVs' technological innovations and advancements. This covers not only the vehicle's battery life and driving range but also intelligent features, connectivity, and autonomous driving capabilities—all of which are selling points for EVs [

29,

30,

31]. This aligns with the study’s findings where discussions in China often emphasized technological optimism, while in Germany, concerns about practical usability were more prevalent. Companies operating in both markets can tailor their strategies accordingly: in China, marketing efforts could focus on the advancements in EVs, whereas in Germany, reassurance regarding infrastructure improvements and environmental impacts might be more effective in encouraging adoption.

Overall, the results of this study reinforce the idea that public sentiments towards electrification is shaped by a combination of policy direction, infrastructure development and consumer expectations. While China’s approach has fostered optimism and confidence in technological progress, Germany’s public discourse remains more skeptical, driven by concerns about practicality and long-term effects. However, it is important to consider that negative sentiment alone does not necessarily indicate a major concern, it must be evaluated in the context of how frequently the theme is discussed. Additionally, neutral sentiment is higher in Germany, reflecting a more measured, fact-based discussions, while in China, the topic of electrification evokes stronger emotional reactions, leading to more positive and negative opinions. These insights can help guide policy makers and industry leaders in crafting targeted strategies that address the specific concerns of each market, ultimately facilitating a smoother transition toward sustainable mobility (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

4.1. Limitations

Despite its valuable insights, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. One of the primary constraints is the broad and general nature of the dataset. While social media provides a rich and dynamic source of public discourse, it does not always capture a fully representative sample of the society. Social media users tend to be younger, more tech-savvy and more engaged in online discussions, which may lead to an overpresentation of certain demographic groups while underpresenting others such as older generations or individuals less active on digital platforms. Furthermore, different social media platforms attract distinct user bases, which may introduce platform-specific biases. For example, discussions on X and Reddit may emphasize certain narratives, whereas perspecctives from professional forums, news comment sections or government consultation platforms might provide a different outlook on electrification in mobility (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

Another limitation occurs from the lack of geo-tagged data in the dataset. Since the dataset does not contain specific geographical information, country-specific content was extracted solely based on language filtering. This approach assumed that posts in German primarily reflect opinions from Germany and posts in Chinese correspond to public opinion in China, but this is not always accurate. As a result, the study may inadvertently include discussions from different cultural and regulatory contexts, which could introduce noise into the analysis.

Moreover, the NLP models used in this study were not specifically trained on the topic of electrification in mobility, which may have impacted the accuracy of sentiment analysis and zero-shot classification. While transformer-based models were employed to carry out the analyzes, these models were pre-trained on general purpose language corpora rather than mobility related discourse. As a result, the subtleties of technical discussions, policy debates and consumer sentiments related to electrification in mobility may not have been fully captured (Chat-GPT 4o, OpenAI, improving language).

Additionally, computational constraints posed a significant challenge in conducting the analysis. While the study was carried out on Google Colab, even the Pro version had limitations in terms of GPU, CPU, RAM and compute unit availability. Processing large-scale social media data and running transformer-based models required significant computational power and certain tasks had to be downsampled or optimized to fit within available sources. A high-performance computing setup or an offline analysis using dedicated hardware would have substantially improved processing efficiency, allowing for deeper and more computationally intensive analysis.

Despite these constraints, this study demonstrates the feasibility of using NLP and LLMs to analyze and compare public opinion on electrification in mobility across two countries. By acknowledging these limitations, future research can build upon these findings to create more targeted, accurate and computationally efficient analyses.

4.2. Further Research

This study provides a foundation for analyzing public perception on electrification in mobility using NLP techniques but several areas for future research could improve both the accuracy and depth of analysis. One major limitation was the reliance on social media data which, while valuable, may not fully capture the diversity of public sentiment. Future studies could integrate additional sources such as government reports and survey data to provide a more comprehensive view of public opinion.

Another key area for improvement is geographical precision. Since the dataset lacked geo-tags, country-specific analysis was conducted based on language filtering, which assumes that content in a language pertains the country. Future research could utilize geo-tagged datasets or alternative techniques such as metadata extraction, to improve the accuracy of country-specific analysis.

Moreover, future research could enhance accuracy by fine-tuning models on domain-specific datasets, such as discussions on electric vehicles, mobility policies and sustainability topics. Advanced NLP techniques could also be explored to provide deeper insights into how public discourse on electrification evolves over time.