Introduction

The technology while recognizing its dual-use nature. Crafting narratives that clarify AI’s operant principles and its limits can build public and institutional trust while facilitating regulation that avoids stifling innovation [

1]. Universities and laboratories are already experimenting with ethical sandboxes, spaces where AI and brain-inspired models can be tested under scrutiny without jeopardizing living subjects or sensitive data [

2]. Simulated environments, paired with rapidly evolving neurofeedback protocols, can teach AI to respect the variable affordances of the human nervous system, resulting in safer human–AI collaboration in high-stake scenarios [

3]. Internationally, interdisciplinary consortia that include neuroethicists, policymakers, and computational neuroscientists are drafting treaties analogous to dual-use biotechnology accords, aimed at creating transparent channels for sharing brain data without compromising cognitive privacy [

4]. Furthermore, brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) that decode neural correlates of intent must be underpinned by security protocols that are themselves informed by principles of cognitive architecture, ensuring that any misalignment between human and machine objectives can be rapidly detected and resolved [

5]. Finally, by reciprocally informing one another, the fields of brain research and AI can cultivate a protective co-evolution in which technological advancement and human dignity advance in tandem.

The present article examines the ethical dimensions of employing AI to shield the brain, foregrounding the irreducible imperatives of transparency, safety, and respect for individual autonomy [

6]. By confronting these ethical challenges in advance, we can engineer a future in which AI not only accelerates extraordinary progress but also acts as a vigilant guardian of mental and psychological well-being [

7]. This forward-looking position guarantees that AI retains its role as a beneficial instrument for humanity, harmonizing technological momentum with principled guidelines and practices. Interest in what is now termed “robot ethics” is growing, fueled by the moral dilemmas arising from robotics innovation [

8]. Responsible AI must, therefore, ensure that its operations neither treat individuals inequitably, violate privacy, nor undermine human dignity, for these guarantees are foundational to cultivating societal trust. Ethical imperatives rank as the foremost concern in AI design, since the capacity for autonomous decision-making compels such systems to function in ways that prevent harm and promote fairness [

9].

Trust in AI and the fair, enduring progress of the field demand concerted effort [

10]. Psychologists are thus called upon to disentangle the psychological underpinnings of trust, revealing the factors that enable users to believe in, and rely on, AI systems [

11]. Systematic appraisal of the ethical and social ramifications of AI must continue, such that potential risks can be detected at their inception and subsequently integrated into the design of forthcoming AI generations [

12]. Models must be engineered and deployed in a manner that is ethically defensible, safeguarding rights, fostering equity, and maximizing societal gain, all while curtailing the risk of harm [

13]. To embed these principles within the field, AI ethics must occupy a central position in formal curricula, cultivating practitioners who prioritize safety, uphold ethical norms, and champion the judicious application of AI across diverse sectors[

14].

Ethical Dimensions of AI Implementation and its Ramifications on Society

As artificial intelligence continues to permeate diverse fields, the risk that its design and deployment may be colored by the very biases and limitations of its human creators also escalates, thereby obliging developers to confront the ethical ramifications of their choices [

15]. When biases, whether implicit or overt, become embedded in the training data or learning algorithms, the resulting decision-aiding systems may inadvertently fortify or dilute the ethical traditions they purport to support [

16]. Accordingly, ethical dimensions—especially those pertaining to safety, accountability, and transparency—become indispensable to the measured and principled integration of robots endowed with AI in any domain [

17].

The discipline of AI ethics aspires to align technology with normative expectations, social objectives, and legislative frameworks [

18]. Realizing this ambition requires anticipatory identification and mitigation of ethical liabilities to maximize the distributive advantages of AI for the wider public [

19]. Consensus around fundamental ethical tenets, counterbalanced by variation in operationalization, underscores the imperative of marrying guideline formulation with rigorous normative scrutiny and practical enactment [

20]. The expanding deployment of AI in policing, social services, and beyond accentuates concerns of fairness, visibility in decision-making, and the risk that technology may exacerbate pre-existing social stratifications [

21].

Healthcare providers and analysts must weigh the principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice before embedding artificial intelligence within any healthcare infrastructure [

22]. Such a deliberative process is necessary to safeguard patient rights, foster equitable care, and curtail potential harm [

23]. Ethical scaffolding for these technologies must, in tandem, guarantee transparency, uphold privacy and data security, and embrace inclusive design to counteract systemic biases [

24].

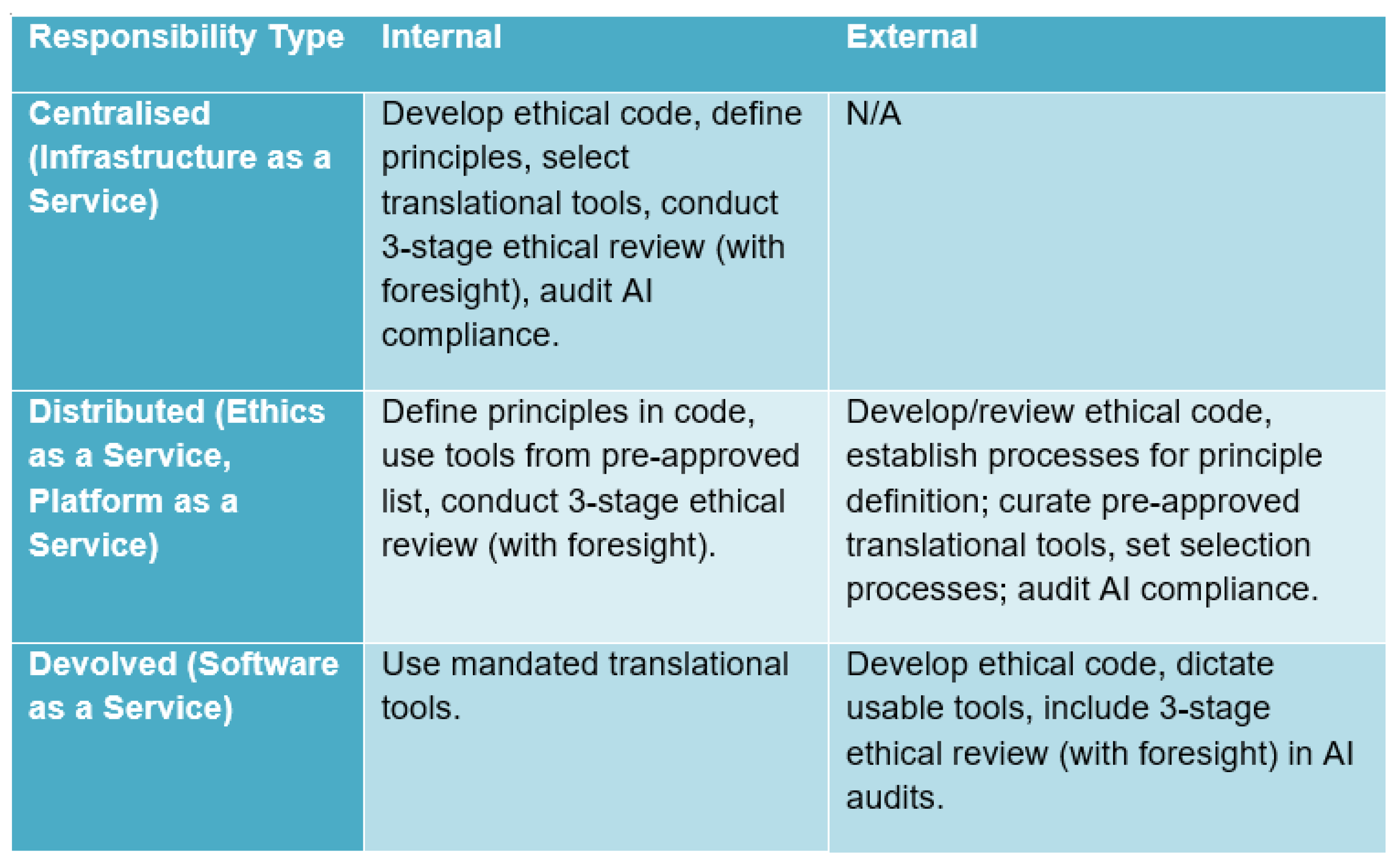

Figure 1.

Comparison of distributions of responsibility.

Figure 1.

Comparison of distributions of responsibility.

The moral incorporation of AI into healthcare is imperative because patient safety, confidentiality of sensitive data, and the imperative of public confidence are non-negotiable [

25]. Mitigating discriminatory patterns within AI algorithms, preserving confidentiality, and earning the sustained trust of both healthcare professionals and society at large are the cardinal ethical hurdles that must be surmounted for AI to add value in clinical practice [

26]. Surmounting these obstacles mandates a thorough and ongoing inquiry into the ethical and regulatory landscape surrounding AI technologies, thereby guaranteeing their accountable design and applicable deployment [

27]. Such strategic frameworks must also promote the traceability and accessibility of underlying data, in concordance with prevailing ethical directives for the use of AI in clinical contexts [

28].

The advancement of artificial intelligence must systematically incorporate data protection, privacy safeguards, and mechanisms of accountability to effectively confront the ethical and legal dilemmas it presents [

29]. A thorough exploration of the ethical dimensions is thus necessary, balancing the transformative promise of AI against the imperative to prevent its socially detrimental consequences [

30]. Embedding ethics requires confronting algorithmic biases, obtaining genuine informed consent, and fostering an environment of trust for both patients and physicians [

31]. Guiding frameworks must remain sensitive to cultural pluralism, demographic inclusivity, and the legacies of historical injustice, tailoring their prescriptions to the specific political and cultural matrices in which AI is deployed [

32]. Such design imperatives are not peripheral; they are instrumental in cultivating AI that is both dependable and congruent with the normative aspirations of diverse societies [

33].

Addressing AI Failures and Ensuring Responsible Development

Addressing the limitations and failures of AI technologies requires a systematic focus on accuracy, resilience, transparency, and fairness, complemented by effective human oversight and control mechanisms. Failures typically arise from an insufficient contextual grasp of the task domain, a phenomenon illustrated by the biased recruiting tool produced by Amazon that inadvertently favored male candidates because its training data consisted largely of male resumes. That problem is not isolated; similar practices at Facebook, Google, and Microsoft suggest a broader pattern of AI systems influencing human cognition and emotion. Such episodes signal that institutions must now prioritize exhaustive bias detection, prompt remediation, and the embedding of bias-aware architectures. Together, these goals necessitate continuous oversight, robust validation stages, and expansive audit trails to guarantee that automated decisions remain both equitable and impartial. Additionally, the creation of Microsoft’s AI chatbot, which began to produce offensive text after absorbing toxic comments from the web, highlights the critical importance of data provenance and the imperative of sustained oversight to avert unforeseen adverse outcomes.

Responsible deployment remains the decisive variable in harnessing the potential of any emerging technology while curtailing its unintended consequences [

34]. Broader stakeholders can facilitate the smooth integration of AI into routine clinical workflows by assuring the integrity of input data, instituting periodic software maintenance, and openly disclosing the limitations of the technology, including the risks posed by entrenched data biases [

35].

The influential scholar John Searle presents a striking account of consciousness in his most recent work, insisting that any competent sentient being is ipso facto a criterion of truth about consciousness and sentience. His exposition hinges on a distinction between strict causality, governed by natural laws, and a broader notion of coordination, in which intentionality plays a constitutive role. Searle contends that while neurobiological states of a being may be causally influenced, they are not causally exhaustively specified by natural processes, thereby leaving sentience intact in the face of mechanistic reductionism. The resulting position, termed “biological naturalism,” mandates that the properties of consciousness, while emergent, are nonetheless irreducibly tied to the causal powers of biological systems.

Critics of Searle have often seized on his insistence that explanations ever in principle must take the form of causal chains. However, the subtler force of his argument lies in the apparent persistence of epistemological contradiction: one may elaborate a complete neurobiological model of a living brain without ever corresponding the model to the living being’s own perspective. By placing constraint on neurologic states while affirming the intransitive epistemic authority of the intentional subject, Searle re-establishes a non-dual footing from which the authority of consciousness, the irreducibility of qualia, and the objectivity of a fully shown neurophysiology may be re-synthesized. The emergent properties, while histories of particular processes, are objectively given in the broader embedded world.

The practical significance of Searle’s position reverberates across both cognitive sciences and the ethics of artificial intelligence. In distinction from reductionist eliminativism, his argument inevitably permits the attribution of a conscious perspective to organisms and systems whose neural correlates are not yet fully specified, yet the criterion is not a speculative threshold but rather the practical detection of biologically imprintable intentional states. The moral and policy implications—especially in the governance of potential artificial agents that may one day biologically instantiate consciousness—retain a firm, empirically weighted anchor in the causal continuity of living organisms. Such a position, while countering ontological fragmentation, presents the methodological obligation to retain a stewardship that is neither wholly deferential to mechanistic appetite nor categorically derisive of cognitive attainment.

By aligning interventions with ethical benchmarks, the health sector can employ AI to enhance service quality, clinical outcomes, and professional satisfaction [

36]. Equally, the incorporation of AI into dental curricula requires a judicious equilibrium between harnessing technological potential and safeguarding ethical integrity [

37]. Tackling vulnerabilities in data safeguarding and financial constraints is likewise essential to realize AI’s ethical and sustainable deployment in health [

38]. By foregrounding ethical ramifications and instilling a robust grounding in AI capabilities, constraints, and pitfalls, educators empower emerging practitioners to foreground patient welfare in all AI-supported interventions [

39]. Worldwide, more than 80 ethical frameworks for AI in health have been promulgated, underscoring transparency, equity, avoidance of harm, accountability, and data protection as cardinal precepts [

40]. Regulatory agencies are charged with delineating validation and certification protocols, which must encompass systematic evaluation of precision, dependability, and safety across heterogeneous clinical scenarios [

41]. Safeguarding patient safety and advancing fairness requires concerted attention to data confidentiality, the perils of model overfitting, and the imperative for well-annotated training datasets [

42]. Uniformity in the design, evaluation, and rollout of AI applications is vital to produce dependable clinical results across differing health institutions [

43]. The ethical architecture of AI must incorporate considerations of equity, privacy, bias mitigation, and interpretability to guarantee responsible usage in patient care [

44]. Collectively, these strategies will magnify AI’s advantages while curtailing inadvertent harm [

45]. Such vigilance is particularly warranted in light of the risk that excessive dependence on AI could erode clinical reasoning and decision-making capabilities [

46]. Consequently, proficiency in AI literacy among health practitioners is a non-negotiable prerequisite for fostering both safe and ethical AI-augmented care [

47].

Algorithm of Brain Hacking

Within the emergent discipline of neuro-enhancement, sometimes informally labelled “brain hacking,” researchers apply cognitive science and neurotechnology to optimize cognitive performance and address clinical disorders[

48]. Threat characterization identifies exploitable system weaknesses and plausible trajectories of robotic and algorithmic attack, while anomaly recognition trains detectors to signal deviations from normative operational signatures[

49,

50]. Adversarial fortification specifies barrier algorithms and redundancy architectures that absorb, obscure, or counter anticipated aggressor maneuvers[

51].

Regulatory agencies must, therefore, draft fresh statutes, operational guidelines, and forensic checklists to monitor the admissibility of algorithmic judgements in litigation and liability matches[

52]. Within such frameworks, formal verification assets and interpretive visualisers confirm that learned models satisfy constraints on safety, fairness, and robustness[

53]. These procedural, proceduralist techniques encourage accountancy, scrutiny, and anticipatory governance of algorithmic risk[

54].

A further priority is the encryption of sensitive training datasets and the disclosure of model architectures without compromising trade secrets, thereby honouring clinical privacy and informed consent mandates[

55]. Integrating such measures into the regulatory landscape is essential to patient safety and the broader legitimacy of algorithmic medicine. At the ethical level, the paramount norm in the design of artificial intelligence for health settings ought to be the preservation of human well-being, framed under legal statutes that repeatedly affirm the absence of moral status for machines, and that continue to place accountability firmly in human hands [

56].

The deliberate incorporation of explainable AI methodologies can substantially increase transparency, delivering intelligible accounts of how algorithms derive their conclusions [

57]. Such transparency, in turn, is crucial for cultivating confidence among clinicians and patients alike [

58]. Healthcare organizations, therefore, bear the duty to engage in comprehensive patient education and to maintain unambiguous channels of communication, clarifying why AI is deployed, what advantages it presents, and what specific protective measures safeguard personal data [

59]. Compliance with statutory obligations—exemplified by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act—remains non-negotiable, especially in the contexts of data protection and the mitigation of bias and discrimination within algorithmic design. Sensitizing patients to the workings of the technology, reinforced by transparency, can significantly mitigate apprehension and engender trust [

60]. Systematic training across the healthcare workforce in the principles and practices of AI is, therefore, a critical complementary action [

61]. The consolidation of AI within care delivery must proceed with a sustained emphasis on explainability and interpretability, to warrant ethical deployment and to sustain trust among all end users [

62]. By centering efforts on these dimensions, institutions can responsibly integrate sophisticated AI tools without diminishing the primacy of human health and rights.

Continued advancements in artificial intelligence present significant opportunities for the healthcare sector to enhance diagnostic precision and optimize treatment planning, contingent on robust safeguards for patient confidentiality and transparent disclosure of AI-driven reasoning [

63]. Effective strategy development requires examination of core terminology, prevailing applications, and ethical imperatives, thereby establishing a nuanced comprehension of AI’s integration into clinical practice [

64]. The ethical obligation of AI developers and system operators is foundational for the preservation of patient trust and the safeguarding of clinical safety [

65]. Comprehensive longitudinal clinical trials that assess the clinical efficacy, safety profiles, and economic impact of AI algorithms will be essential, particularly when those studies incorporate heterogeneous patient cohorts and benchmark results against established therapeutic protocols [

66].

To translate the potential of medical AI into tangible improvements, a concerted awareness of the intrinsic challenges posed by opaque algorithmic logic is indispensable for developers, healthcare practitioners, and regulatory authorities [

67]. Clinicians must assume principal responsibility for the deployment of AI technologies in patient care, thereby actively confronting misconceptions and establishing AI as a supportive and trustworthy adjunct in clinical decision-making [

68]. A thorough comprehension of algorithmic mechanics is essential for healthcare providers to avert the patient harm that can arise from inaccurate AI-driven recommendations, as flawed implementation can compromise patient safety [

69].

AI Concern to Mind Control, Manipulation, and Autonomous Weaponry

Maintaining rigorous data protection protocols remains a fundamental requirement for the ethically responsible adoption of artificial intelligence technologies. Institutions must therefore apply strict privacy regulations and establish resilient technical defenses to safeguard personally identifiable data against unauthorized access, potential security breaches, and various forms of exploitation[

70].

Concurrently, curricula across technical and health disciplines must expand to incorporate extensive AI literacy, ensuring that forthcoming professionals are equipped to design, deploy, and govern AI applications with a persistent commitment to ethical stewardship. Instruction must also tackle legitimate worries regarding diminished face-to-face engagement in clinical contexts and the probabilistic transfer of error from machine-generated to human decision processes[

71,

72].

The synthesis of AI and allied frontier technologies produces distinctive ethical conundrums warranting deliberate scrutiny. Among the gravest is the spectre of AI-guided weaponization, culminating in autonomous strike platforms that can render lethal judgments independent of human oversight[

73]. This scenario prompts severe dilemmas regarding the distribution of moral and legal accountability, the adequacy of human control, and the possibility of escalatory and unintended outcomes on the battlefield. Concurrently, the embedding of AI in everyday systems heightens the vulnerability to malign exploitation—ranging from pervasive monitoring and electoral subversion to the deliberate fracturing of informational privacy. In order to attenuate these hazards, the formulation of explicit ethical standards, robust legislative architectures, and binding multilateral accords is essential, thereby constraining the evolution and deployment of AI to ends that affirm the welfare of the global polity[

74].

The ethical imperatives surrounding AI deployment are thus neither ancillary nor transient; rather, they possess durable consequences that permeate the social fabric and demand anticipatory and circumspect governance. The implementation of artificial intelligence in healthcare must involve, at a minimum, ongoing surveillance, strict validation testing, and publicly accessible documentation of decision processes to verify that these technologies remain faithful to ethical norms and collective priorities [

75]. Governing frameworks must therefore confront conflicting priorities such as the preservation of free expression, the delineation of data stewardship rights, and the prevention of discriminatory outcomes, since each dimension bears considerable consequences for individuals and vulnerable populations [

76]. Remediation of algorithmic distortion, assignation of liability, and clarity of process remain essential for reducing unintentional injury caused by technology [

77]. Collectively these duties facilitate the realization of AI’s promise and the defense of inviolable human rights [

78].

It is accordingly essential to embed ethical precepts within the education of future dentists and all other practitioners anticipated to collaborate with AI technologies. Such instruction must foreground patient welfare, integrity in professional practice, and the judicious employment of AI to foster public confidence and to actualize the advantages intrinsic to these advancements. The infusion of ethical reflection into AI engineering mandates unremitting scrutiny, comprehensive validation, and transparent documentation, so as to reconvene the design and deployment of AI apparatus with prevailing moral precepts and the broader corpus of communal values.

Figure 2.

Increase in AI Dependence Symptoms Among Adolescents. The figure is plotted using data extracted from [

93].

Figure 2.

Increase in AI Dependence Symptoms Among Adolescents. The figure is plotted using data extracted from [

93].

AI Technology Is Advancing Quickly; Therefore, It Is Imperative to Ensure Moral Values Are Incorporated into AI Systems to Foster Responsible and Ethical Use

Multidimensional, interdisciplinary collaboration, sustained oversight, and an adaptable approach to emerging ethical dilemmas [

84]. Such partnerships will prompt a critical recalibration of prevailing moral norms, weighing AI-related hazards against potential societal gains, and will facilitate the integration of fairness criteria at the earliest stages of design to counter discriminatory outcomes [

85,

86]. These collaborative ventures ought to encompass the iterative formulation of ethical frameworks and ongoing dialogue that engages both AI specialists and the wider community [

87]. Ethical governance must rest on leadership that commits to transparency, fairness, and accountability, thereby counteracting bias, protecting data privacy, and reinforcing public trust. Such leaders are charged with forging a comprehensive moral canon to steer AI innovation, emphasizing justice, transparency, accountability, and the enhancement of human welfare. Effective governance of artificial intelligence demands interdisciplinary teamwork and ongoing surveillance to respond nimbly to evolving ethical dilemmas [

88]. Ethical governance thereby secures the constructive influence of AI by embedding moral vigilance and accountability throughout its lifecycle. Nevertheless, the preponderance of diverse ethical AI principles can create uncertainty, accentuating the necessity for Deliberate attention to how AI is integrated, how data is governed, and how autonomy is delegated in contexts devoid of human oversight is non-negotiable [

89].

Such stewardship is further strengthened by targeted reskilling programs that familiarize the workforce with data stewardship, AI ethical frameworks, and strategies for curtailing biased outputs, thereby lessening exposure to reputational and regulatory hazards. Proactive policy design and procedural safeguards can then limit discriminatory impacts and buffer organizations against legal repercussions stemming from algorithmic decisions [

90]. Their overarching mission should be to institutionalize ethical benchmarks compatible with AI-intensive environments [

91]. Senior decision-makers must weave together technical and socio-legal dimensions in every phase from design to deployment, thereby embedding principled norms into the fabric of corporate governance [

92].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ethical by-products of AI cannot be overlooked and ought to command the concerted vigilance of scientists, designers, legislators, and the wider citizenry alike. If we confront these questions with both foresight and shared purpose, we may convert AI’s revolutionary promise into dividends that reflect, rather than dilute, the fundamental values that bind us. A strategy robust enough to steer the ethical stakes of AI depends on the coalescence of cognitive neuroscientists, dedicated ethicists, and informed legislators, especially with regard to AI’s altering influence on mental processes, social conduct, and holistic human flourishing. As AI architectures grow more embedded—from hospitals and credit markets to transit networks and classrooms—the obligation to surveil and neutralize the concealed risks and layered complexities of their diffusion becomes non-negotiable. Embedding ethical deliberation into every phase of a system’s lifecycle is therefore no longer a discretionary enhancement; it is a protective measure against catastrophes that could threaten human survival, and it is likewise the pre-emptive remedy to the corrosion of fairness by algorithmic bias. Such foresight guarantees that AI’s boons are distributed transparently and that the architecture of society remains sufficiently resilient to certify that every demographic and every socioeconomic tier may participate equally in the fruits of these potent technologies.

Ethics declaration

not applicable.

Consent to Participate declaration

not applicable.

Consent to Publish declaration

not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. Eke, K. Wakunuma, and S. Akintoye, Responsible AI in Africa. Springer International Publishing, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Ren and F. Xia, “Brain-inspired Artificial Intelligence: A Comprehensive Review,” arXiv (Cornell University). Cornell University, Aug. 27, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Rashid, A. K. Kausik, A. A. H. Sunny, and M. H. Bappy, “Artificial Intelligence in the Military: An Overview of the Capabilities, Applications, and Challenges,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems, vol. 2023, p. 1, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Nasir, R. A. Khan, and S. Bai, “Ethical Framework for Harnessing the Power of AI in Healthcare and Beyond,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Mylrea and N. Robinson, “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Trust Framework and Maturity Model: Applying an Entropy Lens to Improve Security, Privacy, and Ethical AI,” Entropy, vol. 25, no. 10, p. 1429, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Thorat, P. Rao, N. Joshi, P. Talreja, and A. Shetty, “Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Patient Education and Communication in Dentistry,” Cureus, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Lepri, N. Oliver, and A. Pentland, “Ethical machines: The human-centric use of artificial intelligence,” iScience, vol. 24, no. 3. Cell Press, p. 102249, Mar. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. A. S. H. A. Kubaisi, “Ethics of Artificial Intelligence a Purposeful and Foundational Study in Light of the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad,” Religions, vol. 15, no. 11, p. 1300, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Singh and A. Joshi, “Ethical Considerations in AI Development,” in Advances in computational intelligence and robotics book series, IGI Global, 2024, p. 156. [CrossRef]

- A. Batool, D. Zowghi, and M. Bano, “AI governance: a systematic literature review,” AI and Ethics, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, B. Wu, Y. Huang, and S. Luan, “Developing trustworthy artificial intelligence: insights from research on interpersonal, human-automation, and human-AI trust,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 15. Frontiers Media, Apr. 17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Fiske, P. Henningsen, and A. Buyx, “Your Robot Therapist Will See You Now: Ethical Implications of Embodied Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 21, no. 5. JMIR Publications, Feb. 26, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. R. Saeidnia, S. G. H. Fotami, B. Lund, and N. Ghiasi, “Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence Interventions for Mental Health and Well-Being: Ensuring Responsible Implementation and Impact,” Social Sciences, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 381, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Harte, B. Carey, Q. J. Feng, A. Alqarni, and R. Albuquerque, “Transforming undergraduate dental education: the impact of artificial intelligence,” BDJ, vol. 238, no. 1, p. 57, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Borenstein and A. Howard, “Emerging challenges in AI and the need for AI ethics education,” AI and Ethics, vol. 1, no. 1. Springer Nature, p. 61, Sep. 13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. KARAKUŞ, K. Gedik, and S. Kazazoğlu, “Ethical Decision-Making in Education: A Comparative Study of Teachers and Artificial Intelligence in Ethical Dilemmas,” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 469, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Chopra, “Artificial Intelligence in Robotics: (Review Paper),” International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 2345, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Morley, A. Elhalal, F. Garcia, L. Kinsey, J. Mökander, and L. Floridi, “Ethics as a Service: A Pragmatic Operationalisation of AI Ethics,” Minds and Machines, vol. 31, no. 2, p. 239, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, Z. Zhang, B. Mao, and X. Yao, “An Overview of Artificial Intelligence Ethics,” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 799, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Jobin, M. Ienca, and E. Vayena, “The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 9, p. 389, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. C. Vargas, “Exploiting the margin: How capitalism fuels AI at the expense of minoritized groups,” AI and Ethics, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Farhud and S. Zokaei, “Ethical Issues of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Healthcare,” Iranian Journal of Public Health. Knowledge E, Oct. 27, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Pham, “Ethical and legal considerations in healthcare AI: innovation and policy for safe and fair use,” Royal Society Open Science, vol. 12, no. 5. Royal Society, May 01, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Abujaber and A. J. Nashwan, “Ethical framework for artificial intelligence in healthcare research: A path to integrity,” World Journal of Methodology, vol. 14, no. 3. Jun. 25, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Singh and Y. N. Keche, “Ethical Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Narrative Review of Global Challenges and Strategic Solutions,” Cureus. Cureus, Inc., May 25, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Reddy, S. Allan, S. Coghlan, and P. Cooper, “A governance model for the application of AI in health care,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 27, no. 3, p. 491, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Mennella, U. Maniscalco, G. D. Pietro, and M. Esposito, “Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4. Elsevier BV, Feb. 01, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Schwendicke, W. Samek, and J. Krois, “Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Chances and Challenges,” Journal of Dental Research, vol. 99, no. 7. SAGE Publishing, p. 769, Apr. 21, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. O. Akinrinmade et al., “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Perception and Reality,” Cureus. Cureus, Inc., Sep. 20, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Jeyaraman, S. Balaji, N. Jeyaraman, and S. Yadav, “Unraveling the Ethical Enigma: Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare,” Cureus. Cureus, Inc., Aug. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Weidener and M. Fischer, “Role of Ethics in Developing AI-Based Applications in Medicine: Insights From Expert Interviews and Discussion of Implications,” JMIR AI, vol. 3, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. J. D. Mahamadou, A. Ochasi, and R. B. Altman, “Data Ethics in the Era of Healthcare Artificial Intelligence in Africa: An Ubuntu Philosophy Perspective,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Markus, J. A. Kors, and P. R. Rijnbeek, “The role of explainability in creating trustworthy artificial intelligence for health care: A comprehensive survey of the terminology, design choices, and evaluation strategies,” Journal of Biomedical Informatics, vol. 113. Elsevier BV, p. 103655, Dec. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Muley, P. Muzumdar, G. T. Kurian, and G. P. Basyal, “Risk of AI in Healthcare: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Study Framework,” Asian Journal of Medicine and Health, vol. 21, no. 10, p. 276, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Gerke, T. Minssen, and G. Cohen, “Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligence-driven healthcare,” in Elsevier eBooks, Elsevier BV, 2020, p. 295. [CrossRef]

- A. Shuaib, “Transforming Healthcare with AI: Promises, Pitfalls, and Pathways Forward,” International Journal of General Medicine, p. 1765, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. D’Souza, M. Mathew, V. Mishra, and K. M. Surapaneni, “Twelve tips for addressing ethical concerns in the implementation of artificial intelligence in medical education,” Medical Education Online, vol. 29, no. 1, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Md. Faiyazuddin et al., “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of Advancements in Diagnostics, Treatment, and Operational Efficiency,” Health Science Reports, vol. 8, no. 1. Wiley, Jan. 01, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Jha et al., “Ensuring Trustworthy Medical Artificial Intelligence through Ethical and Philosophical Principles,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Elendu et al., “Ethical implications of AI and robotics in healthcare: A review,” Medicine, vol. 102, no. 50. Wolters Kluwer, Dec. 15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Varghese, E. M. Harrison, G. O’Grady, and E. J. Topol, “Artificial intelligence in surgery,” Nature Medicine, vol. 30, no. 5, p. 1257, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. B. Akhtar, “Artificial intelligence within medical diagnostics: A multi-disease perspective,” Deleted Journal, vol., no., p. 5173, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Lal, A. Nooruddin, and F. Umer, “Concerns regarding deployment of AI-based applications in dentistry – a review,” BDJ Open, vol. 11, no. 1. Springer Nature, Mar. 25, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. B. Emdad, S. M. Ho, B. Ravuri, and S. Hussain, “Towards A Unified Utilitarian Ethics Framework for Healthcare Artificial Intelligence,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Grunhut, O. Marques, and A. T. M. Wyatt, “Needs, Challenges, and Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education Curriculum,” JMIR Medical Education, vol. 8, no. 2, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarfaraz, Z. Khurshid, and M. S. Zafar, “Use of artificial intelligence in medical education: A strength or an infirmity,” Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, vol. 18, no. 6. Elsevier BV, p. 1553, Jul. 08, 2023. [CrossRef]

- [47]Y. Ma et al., “Promoting AI Competencies for Medical Students: A Scoping Review on Frameworks, Programs, and Tools,” arXiv (Cornell University). Cornell University, Jul. 10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Jangwan et al., “Brain augmentation and neuroscience technologies: current applications, challenges, ethics and future prospects,” Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, vol. 16. Frontiers Media, Sep. 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Bonny, W. Al Nassan, K. Obaideen, M. N. Al Mallahi, Y. Mohammad, and H. M. El-damanhoury, “REVIEW Contemporary Role and Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry.” Sep. 20, 2023.

- N. C. Amedior, “Ethical Implications of Artificial Intelligence in the Healthcare Sector,” Advances in Multidisciplinary & Scientific Research Journal Publication, vol. 36, p. 1, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Morone et al., “Artificial intelligence in clinical medicine: a state-of-the-art overview of systematic reviews with methodological recommendations for improved reporting,” Frontiers in Digital Health, vol. 7. Frontiers Media, Mar. 05, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Esmaeilzadeh, “Use of AI-based tools for healthcare purposes: a survey study from consumers’ perspectives,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 20, no. 1, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma et al., “Towards Trustworthy AI in Dentistry,” Journal of Dental Research, vol. 101, no. 11, p. 1263, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Lu, A. D’Agostino, S. L. Rudman, D. Ouyang, and D. E. Ho, “Designing Accountable Health Care Algorithms: Lessons from Covid-19 Contact Tracing,” NEJM Catalyst, vol. 3, no. 4, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Dehbozorgi et al., “The application of artificial intelligence in the field of mental health: a systematic review,” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 25, no. 1. BioMed Central, Feb. 14, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang and Z. Zhang, “Ethics and governance of trustworthy medical artificial intelligence,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Savulescu, A. Giubilini, R. Vandersluis, and A. Mishra, “Ethics of artificial intelligence in medicine,” Singapore Medical Journal, vol. 65, no. 3. Medknow, p. 150, Mar. 01, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Davenport and R. Kalakota, “The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare,” Future Healthcare Journal, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 94, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Yelne, M. Chaudhary, K. Dod, A. Sayyad, and R. Sharma, “Harnessing the Power of AI: A Comprehensive Review of Its Impact and Challenges in Nursing Science and Healthcare,” Cureus. Cureus, Inc., Nov. 22, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Li, Y. Li, M.-Y. Wei, and G. Li, “Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1. Nature Portfolio, Aug. 16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Bajpai and M. Wadhwa, “Artificial Intelligence and Healthcare in India,” Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Nasir, R. A. Khan, and S. Bai, “Ethical Framework for Harnessing the Power of AI in Healthcare and Beyond,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, p. 31014, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Yekaterina, “Challenges and Opportunities for AI in Healthcare,” International Journal of Law and Policy, vol. 2, no. 7, p. 11, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Nazer et al., “Bias in artificial intelligence algorithms and recommendations for mitigation,” PLOS Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 6. Public Library of Science, Jun. 22, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Richardson et al., “A framework for examining patient attitudes regarding applications of artificial intelligence in healthcare,” Digital Health, vol. 8, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Dhopte and H. Bagde, “Smart Smile: Revolutionizing Dentistry With Artificial Intelligence,” Cureus. Cureus, Inc., Jun. 30, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Amann, A. Blasimme, E. Vayena, D. Frey, and V. I. Madai, “Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 20, no. 1, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Y. Hamd, W. Elshami, S. A. Kawas, H. Aljuaid, and M. Abuzaid, “A closer look at the current knowledge and prospects of artificial intelligence integration in dentistry practice: A cross-sectional study,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 6, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Aboalshamat et al., “Medical and Dental Professionals Readiness for Artificial Intelligence for Saudi Arabia Vision 2030,” International Journal Of Pharmaceutical Research And Allied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 52, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Urbani, C. Ferreira, and J. Lam, “Managerial framework for evaluating AI chatbot integration: Bridging organizational readiness and technological challenges,” Business Horizons, vol. 67, no. 5, p. 595, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Rahim et al., “Artificial intelligence-powered dentistry: Probing the potential, challenges, and ethicality of artificial intelligence in dentistry,” Digital Health, vol. 10. SAGE Publishing, Jan. 01, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Halat, R. Shami, A. Daud, W. Sami, A. Soltani, and A. Malki, “Artificial Intelligence Readiness, Perceptions, and Educational Needs Among Dental Students: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Clinical and Experimental Dental Research, vol. 10, no. 4, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Dresp, “The weaponization of artificial intelligence: What the public needs to be aware of,” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Sebastian, “Privacy and Data Protection in ChatGPT and Other AI Chatbots: Strategies for Securing User Information,” SSRN Electronic Journal, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Cremer and D. Narayanan, “How AI tools can—and cannot—help organizations become more ethical,” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 6. Frontiers Media, Jun. 22, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Schultz and P. Seele, “Towards AI ethics’ institutionalization: knowledge bridges from business ethics to advance organizational AI ethics,” AI and Ethics, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 99, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- U. C. Kandasamy, “Ethical Leadership in the Age of AI Challenges, Opportunities and Framework for Ethical Leadership,” arXiv (Cornell University), Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Stahl and D. Eke, “The ethics of ChatGPT – Exploring the ethical issues of an emerging technology,” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 74, p. 102700, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Germani, G. Spitale, and N. Biller-Andorno, “The Dual Nature of AI in Information Dissemination: Ethical Considerations,” JMIR AI, vol. 3, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Thelma, Z. H. Sain, Y. O. Shogbesan, E. V. Phiri, and W. M. Akpan, “Ethical Implications of AI and Machine Learning in Education: A Systematic Analysis,” vol. 3, no. 1, p. 1, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Roshanaei, H. Olivares, and R. R. Lopez, “Harnessing AI to Foster Equity in Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Emerging Strategies,” Journal of Intelligent Learning Systems and Applications, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 123, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Y. Chan, “A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 20, no. 1, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Y. Chan, “A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 20, no. 1, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Diantama, “Pemanfaatan Artificial Intelegent (AI) Dalam Dunia Pendidikan,” DEWANTECH Jurnal Teknologi Pendidikan, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Ferrer, T. van Nuenen, J. M. Such, M. Coté, and N. Criado, “Bias and Discrimination in AI: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective,” IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, vol. 40, no. 2, p. 72, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Mehrabi, F. Morstatter, N. A. Saxena, K. Lerman, and A. Galstyan, “A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. X. Sun, Y. Miao, H. Jiang, M. D. Ding, and J. Zhang, “From Principles to Practice: A Deep Dive into AI Ethics and Regulations,” arXiv (Cornell University), Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. S. M. A. Uddin, “The Era of AI: Upholding Ethical Leadership,” Open Journal of Leadership, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 400, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Elliott et al., “Towards an Equitable Digital Society: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR),” Society, vol. 58, no. 3, p. 179, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Jöhnk, M. Weißert, and K. Wyrtki, “Ready or Not, AI Comes— An Interview Study of Organizational AI Readiness Factors,” Business & Information Systems Engineering, vol. 63, no. 1, p. 5, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Barocas and A. D. Selbst, “Big Data’s Disparate Impact,” California Law Review, vol. 104, no. 3, p. 671, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. J. London, “Accountability for Responsible AI Practices: Ethical Responsibilities of Senior Leadership,” SSRN Electronic Journal, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Lai X, Ke L, Li Y, Wang H, Zhao X, Dai X, Wang Y. AI Technology panic-is AI Dependence Bad for Mental Health? A Cross-Lagged Panel Model and the Mediating Roles of Motivations for AI Use Among Adolescents. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024 Mar 12;17:1087-1102. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |