Core Tip: This case illustrates a high-stakes clinical dilemma in late pregnancy: Adhering to the standard 4-6 week antiretroviral therapy (ART) delay to prevent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) vs aggressively suppressing the human immunodeficiency virus viral load to prevent perinatal transmission. We demonstrate that for a woman presenting in the third trimester with isolated antigenemia, a truncated ART delay-supported by preemptive high-dose fluconazole and vigilant monitoring-was a calculated risk that achieved viral suppression for delivery without provoking IRIS. This case argues not for a new guideline, but for nuanced, individualized decision-making in complex scenarios, highlighting a critical evidence gap and the need to better define IRIS risk in pregnant women with antigenemia.

Introduction

An estimated 6% of people with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (CD4 count < 100 cells/μL) have asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia, a precursor to fatal cryptococcal meningitis [

1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, women bear a disproportionate burden of HIV[

2], and interruptions in antiretroviral therapy (ART), particularly during pregnancy, can lead to advanced immunosuppression and opportunistic infections[

3]. The management of cryptococcal antigenemia in pregnancy is fraught with challenges[

4]. The first-line oral antifungal, fluconazole, carries teratogenic risks, especially in the first trimester[

5]. Also, the optimal timing of ART initiation must balance the crucial goal of preventing mother-to-child transmission against the risk of provoking IRIS[

6].

Current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend delaying ART for 4-6 weeks after starting antifungal treatment for cryptococcal meningitis to reduce mortality from IRIS[

7]. This is a strong recommendation based on robust evidence from non-pregnant adults. However, the application of this delay to pregnant women with isolated antigenemia is not well-defined, creating a significant evidence gap for clinicians who must also weigh the risk of in utero HIV transmission. We present a case that illustrates these dilemmas and the successful, albeit high-risk, application of a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach, providing a practical framework for managing this complex scenario.

Case Presentation

Chief Complaints

A 28-year-old primigravida at 34 weeks of gestation presented with a 3-week history of progressive headache, photophobia, and dizziness.

History of Present Illness

The headaches were temporal, progressive, and without clear aggravating or relieving factors. They were not associated with blurred vision, loss of consciousness, fever, or neck stiffness.

History of Past Illness

She had been diagnosed with HIV two years prior and initiated on tenofovir/lamivudine/dolutegravir (TLD), but self-discontinued therapy after six months due to personal reasons. She reported good adherence to hematinic supplements.

Personal and Family History

No significant family history of infectious or neurological diseases was reported. The patient had no other chronic illnesses.

Physical Examination

On admission, the patient was alert (Glasgow Coma scale 15/15) and in fair general condition. Vital signs were stable. Neurological examination revealed no nuchal rigidity, intact cranial nerves, and normal motor and sensory function. No skin lesions suggestive of Kaposi’s sarcoma were noted. Obstetric examination was consistent with a 34-week singleton pregnancy in cephalic presentation with normal fetal heart sounds.

Laboratory Examinations

Laboratory investigations revealed a positive serum cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) titer of 1:80, an HIV viral load of 41200 copies/mL, and microcytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin 9.3 g/dL). A baseline CD4 count was unavailable due to a nationwide stock-out of the testing kits, which is a recognized limitation in our setting. Lumbar puncture was performed to rule out meningeal involvement; cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed an opening pressure of 16 cm H

2O, no white blood cells, normal protein and glucose levels, and was negative for CrAg, culture, and GeneXpert MTB/Rif assay. Key laboratory parameters are summarized in

Table 1.

Imaging Examinations

Obstetric ultrasound confirmed a singleton, viable fetus at 34 weeks of gestation with normal biometry and amniotic fluid volume. No neuroimaging was performed.

Multidisciplinary Expert Consultation

A team comprising obstetrics, infectious disease, anesthesia, and critical care was convened. The consensus was to continue high-dose fluconazole for a full 8-week induction course, closely monitor for drug toxicity and clinical progression, and prepare for potential obstetric complications given her general debility. The team engaged in extensive discussion regarding the timing of ART, weighing the unequivocal WHO recommendation for a 4-6 week delay against the imminent risk of perinatal HIV transmission.

Final Diagnosis

Asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia in the context of advanced HIV disease and treatment interruption.

Treatment

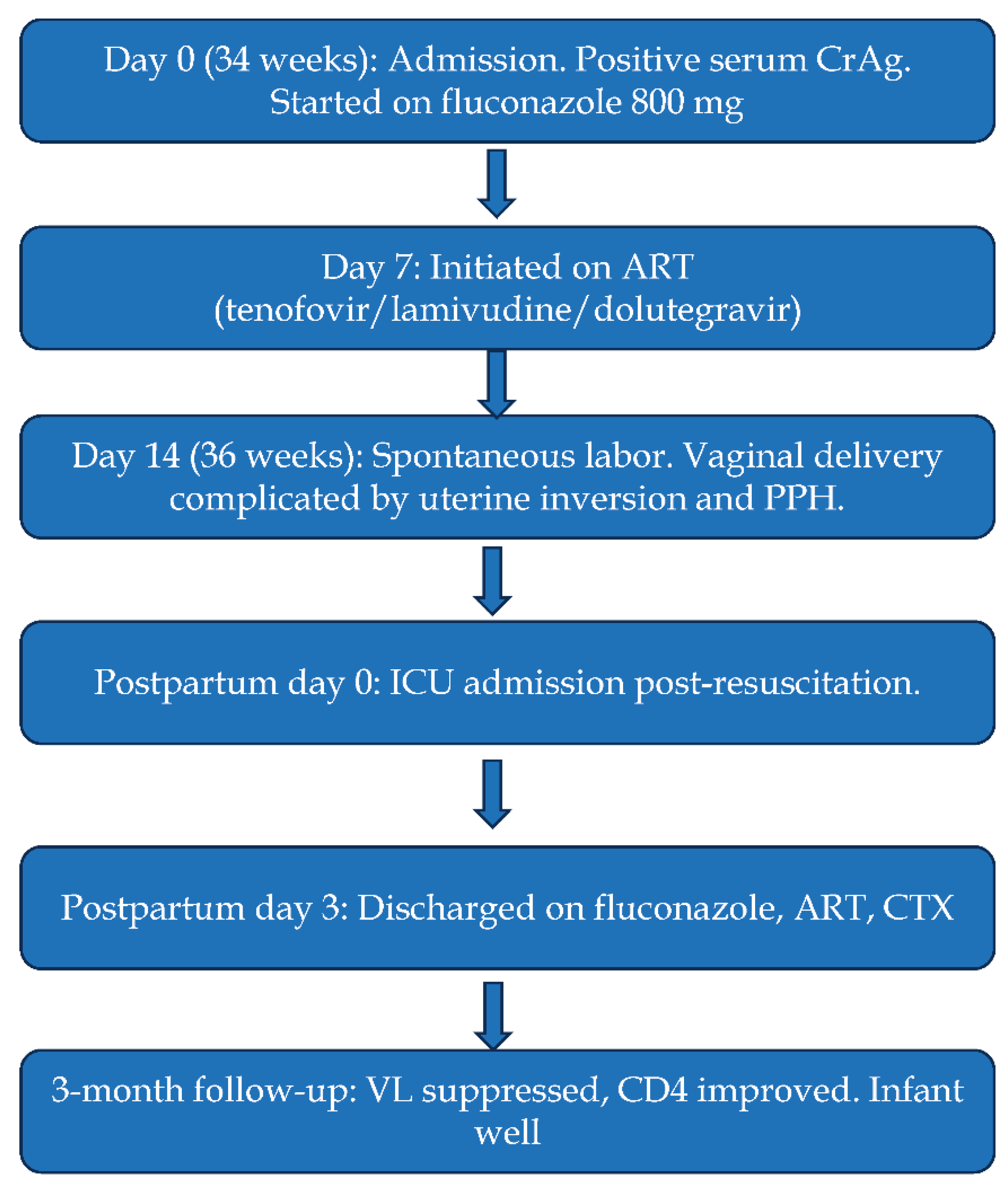

The management plan and timeline are summarized in

Figure 1. Induction therapy with high-dose fluconazole (800 mg daily) was initiated. Despite the strong WHO recommendation to delay ART for 4-6 weeks, the multidisciplinary team, after thorough risk-benefit analysis and counselling the patient, made a conscious decision to re-initiate TLD after only 7 days of antifungal therapy. This decision was driven by her advanced gestational age (34 weeks) and the paramount need to rapidly reduce the viral load to minimize the risk of perinatal HIV transmission, accepting a potential increased risk of IRIS. The patient was closely monitored as an outpatient for clinical signs of IRIS.

Obstetric Management & Complications

At 36 weeks, she presented in spontaneous labor. The delivery was complicated by acute uterine inversion and an estimated postpartum hemorrhage of 2500 mL. This was managed with active management of the third stage of labor, immediate manual replacement of the inverted uterus under ketamine anesthesia, and aggressive management of hypovolemic shock with blood products (2 units) and crystalloids.

Outcome and Follow-Up

She delivered a live female infant (birth weight 2445 g, Apgar scores 8, 9, and 10) via vaginal delivery. She was admitted to the intensive care unit for 24 hours and discharged on postpartum day 3 on consolidative fluconazole (400 mg daily), TLD, and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis. The patient did not develop cryptococcal IRIS during admission or after discharge. At the 3-month follow-up, her HIV viral load was suppressed to 51 copies/mL, and her CD4 count was 250 cells/μL. The infant received standard nevirapine and zidovudine prophylaxis. An HIV DNA polymerase chain reaction test at 6 weeks was negative, and the infant showed normal growth and developmental milestones at 6 months of age.

Discussion

This case provides critical insights into managing the complex intersection of HIV, opportunistic infection, and pregnancy. The successful outcome, achieved despite a significant deviation from standard ART timing guidelines, underscores the necessity of individualized care in specific obstetric contexts and highlights several key management principles.

First, the case underscores the life-saving potential of routine CrAg screening in high-risk pregnant populations. Asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia, defined by the presence of serum CrAg without overt meningitis, is an early marker of disseminated infection[

8] and is highly prognostic for the development of meningitis, which carries a mortality rate exceeding 50% in resource-limited settings if untreated[

9,

10]. Our patient’s significant serum CrAg titer of 1:80 indicated a high fungal burden, a risk potentiated by the immune changes of pregnancy. This aligns with WHO recommendations for CrAg screening in ART-naive individuals with CD4 counts < 100 cells/μL[

11,

12] and argues for its rigorous integration into antenatal care for all women with advanced HIV, regardless of symptoms.

The management of this patient required navigating two significant therapeutic dilemmas-the first involved antifungal selection. The use of high-dose fluconazole in the third trimester, while carrying a teratogenic warning in the first trimester, is supported by pharmacoepidemiologic data showing a significantly lower risk of birth defects later in pregnancy[

4,

5]. While global guidelines recommend amphotericin B for its superior fungicidal activity in meningitis[

10], its use was logistically challenging in our setting. Thus, fluconazole monotherapy represented a necessary, pragmatic compromise based on resource constraints.

The second and more critical dilemma was the timing of ART initiation. Randomized controlled trials have established that delaying ART for 4-6 weeks reduces IRIS and mortality in cryptococcal meningitis, forming a cornerstone of management[

7]. Our decision to initiate ART after only a 1-week delay was a significant deviation, taken with full awareness of the risks. The patient’s advanced gestational age drove this calculus; a standard delay would have meant initiating ART perilously close to, or after, delivery, virtually guaranteeing a high risk of perinatal transmission. In this unique context of isolated antigenemia, the risk of vertical transmission was deemed more immediate and certain than the risk of IRIS. The patient’s successful outcome without IRIS, while fortunate, does not negate the guideline but demonstrates that in extreme circumstances, recommendations must be adapted with multidisciplinary consensus, explicit informed consent, and vigilant monitoring.

Considering the pathophysiology of IRIS provides further context for this outcome. The overall incidence of IRIS in people living with HIV is 10%-30%[

6], with risk significantly heightened at CD4 counts below 50-100 cells/μL, particularly with dolutegravir-based regimens. Furthermore, pregnancy and the postpartum period are states of dynamic immune shift that increase the risk of unmasking IRIS[

13]. Our patient’s neurological symptoms at presentation required a high index of suspicion to rule out subclinical meningitis that could have been unmasked by rapid immune recovery.

A critical question, therefore, is why IRIS did not develop despite the truncated ART delay. The explanation is likely multifactorial. The successful preemptive reduction of the cryptococcal antigen burden with high-dose fluconazole before significant immune reconstitution occurred was a key factor. Additionally, the entity of isolated antigenemia itself may carry a different, and perhaps lower, risk of IRIS compared to established meningitis[

14]. It is also plausible that her baseline CD4 count, while low, was not in the very highest risk stratum (e.g., < 50 cells/μL).

Our case highlights the general vulnerability of this patient population. The spontaneous preterm delivery at 36 weeks, while potentially linked to multiple factors including HIV itself[

15,

16], was further complicated by severe uterine inversion and postpartum hemorrhage. This obstetric emergency, exacerbated by pre-existing anemia, reinforces the imperative for managed delivery in a facility with full resuscitation capabilities and ready multidisciplinary support.

Limitations

The lack of a baseline CD4 count, while a constraint of the setting, omits a key stratifier of risk. The positive outcome, while encouraging, represents a single experience and should not be interpreted as validating the strategy. The use of fluconazole monotherapy, while practical, is suboptimal for disseminated disease. Finally, the absence of IRIS in this case does not prove the strategy is safe, and it must be approached with extreme caution.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this report illustrates that the management of cryptococcal antigenemia in late pregnancy may necessitate a nuanced, patient-centered approach to ART timing. While standard guidelines recommend a 4-6 week delay to mitigate IRIS risk, this must be balanced against the imminent threat of vertical HIV transmission. Our experience indicates that for a select group of women with isolated antigenemia in the third trimester, a truncated ART delay, when carefully managed by a multidisciplinary team, can achieve favorable maternal and infant outcomes. This case argues for more formal research to definitively establish the optimal ART initiation timeline for this specific clinical dilemma.

Author Contributions

Mark MM contributed to conceptualization, data collection, and drafting of the manuscript; Ng’ang’a AK contributed to patient management, literature review, and critical revision; Omullo FP contributed to manuscript drafting, investigation, and resources; Bereda G contributed to supervision, validation, and manuscript review; Muchiri CT contributed to supervision, manuscript revision, and final approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinical staff of the obstetric, medical, and intensive care unit departments at Murang’a County Referral Hospital for their dedicated patient care.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

CARE Checklist (2016) Statement

The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

References

- Rajasingham, R; Smith, RM; Park, BJ; Jarvis, JN; Govender, NP; Chiller, TM; Denning, DW; Loyse, A; Boulware, DR. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharsany, AB; Karim, QA. HIV Infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Status, Challenges and Opportunities. Open AIDS J 2016, 10, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrocq, G; Rakhmanina, N. Antiretroviral therapy interruptions: impact on HIV treatment and transmission. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2018, 10, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mølgaard-Nielsen, D; Svanström, H; Melbye, M; Hviid, A; Pasternak, B. Association Between Use of Oral Fluconazole During Pregnancy and Risk of Spontaneous Abortion and Stillbirth. JAMA 2016, 315, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastick, KA; Nalintya, E; Tugume, L; Ssebambulidde, K; Stephens, N; Evans, EE; Ndyetukira, JF; Nuwagira, E; Skipper, C; Muzoora, C; Meya, DB; Rhein, J; Boulware, DR; Rajasingham, R. Cryptococcosis in pregnancy and the postpartum period: Case series and systematic review with recommendations for management. Med Mycol 2020, 58, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddow, LJ; Colebunders, R; Meintjes, G; Lawn, SD; Elliott, JH; Manabe, YC; Bohjanen, PR; Sungkanuparph, S; Easterbrook, PJ; French, MA; Boulware, DR. International Network for the Study of HIV-associated IRIS (INSHI). Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Infect Dis 2010, 10, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshun-Wilson, I; Okwen, MP; Richardson, M; Bicanic, T. Early versus delayed antiretroviral treatment in HIV-positive people with cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 7, CD009012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, XL; Zhao, T; Harypursat, V; Lu, YQ; Li, Y; Chen, YK. Asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia in HIV-infected patients: a review of recent studies. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, JN; Lawn, SD; Vogt, M; Bangani, N; Wood, R; Harrison, TS. Screening for cryptococcal antigenemia in patients accessing an antiretroviral treatment program in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 48, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaishi, T; Tarasawa, K; Fushimi, K; Yaegashi, N; Aoki, M; Fujimori, K. Demographic profiles and risk factors for mortality in acute meningitis: A nationwide population-based observational study. Acute Med Surg 2024, 11, e920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemal, M; Deress, T; Belachew, T; Adem, Y. Prevalence of Cryptococcal Antigenemia and Associated Factors among HIV/AIDS Patients at Felege-Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Microbiol 2021, 2021, 8839238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbie, A; Mekonnen, D; Woldeamanuel, Y; Abebe, T. Cryptococcal antigenemia and its predictors among HIV infected patients in resource limited settings: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X; Jin, R. Effects of postpartum hormonal changes on the immune system and their role in recovery. Acta Biochim Pol 2025, 72, 14241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, RM; Molloy, SF; Jarvis, JN; Harrison, TS; Govender, NP. Cryptococcal Antigenemia in Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, and Clinical Implications. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wastnedge, EAN; Reynolds, RM; van Boeckel, SR; Stock, SJ; Denison, FC; Maybin, JA; Critchley, HOD. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol Rev 2021, 101, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, PL; Zhou, YB; Chen, Y; Yang, MX; Song, XX; Shi, Y; Jiang, QW. Association between maternal HIV infection and low birth weight and prematurity: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).