1. Introduction

In mammalian cells, hemichannels (half of gap junction channels; HCs) are constituted of six protein subunits in the case of connexins (Cxs) or seven subunits in the case of pannexins (Panxs) [

1,

2]. At the cell surface, these large-pore channels can communicate the intracellular with the extracellular compartments. These HCs can permeate ions and small molecules, metabolites and autocrine and paracrine signals (e.g., ATP, cyclic nucleotides, prostaglandin E

2, NAD

+, glutathione and glutamate) [

3].

During physiological responses, Cx and Panx1 HCs may open briefly without compromising cell survival [

4,

5]. However, diverse pathological conditions or gain-of-function mutations can induce sustained HC opening, inflammation and cell death [

6,

7,

8]. Several of the HC permeants can contribute to cell death. In this respect, one of the most important are calcium ions (Ca

2+), because they can activate Ca

2+-dependent proteases, lipases and nucleases which participate in numerous intracellular metabolic pathways [

9]. Cx26 and Cx43 HCs have been shown to be permeable to Ca

2+ [

10,

11]. In contrast, Cx39 and Panx1 HCs are impermeable to Ca

2+ [

12,

13]. However, recent work has demonstrated that Panx1 HCs become permeable to Ca

2+ and induce cell death only after C-terminal truncation of the protein [

13]. On the other hand, the permeability of Cx45 Hs to Ca

2+ remains unknown.

Although numerous reports have suggested that HCs are involved in cell death mediated by necrosis or apoptosis [

14,

15,

16], the relative importance of HCs formed by Cxs and Panx1 remains elusive. The issue may be even more complex when considering that pathological conditions may alter the relative level of expression of these proteins as occurs in mammalian skeletal muscles. Differentiated cells in this tissue normally express Panx1 but do not express Cxs. Yet, under several pathological conditions (i.e., denervation, muscle dystrophies, sepsis, diabetes and long-term glucocorticoid treatment) there is

de novo expression of three Cxs (i.e., Cx39, Cx43 and Cx45) and up-regulation of Panx1 levels [

17]. Interestingly, under the different pathological conditions skeletal muscles show increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and muscle fiber death [

18,

19,

20,

21]. ROS levels also increase in skeletal muscle after dexamethasone treatment, phenomenon that does not occur in mice lacking Cx43 and Cx45 [

22]. However, the individual contribution of each Cx HC to cell death remains unknown.

The present work was undertaken to study whether elevated HC activity leads to an increase in Ca2+ influx, generation of ROS and cell death. We found a direct correlation of these changes only in cells expressing Cx43 or Cx45 HCs.

2. Results

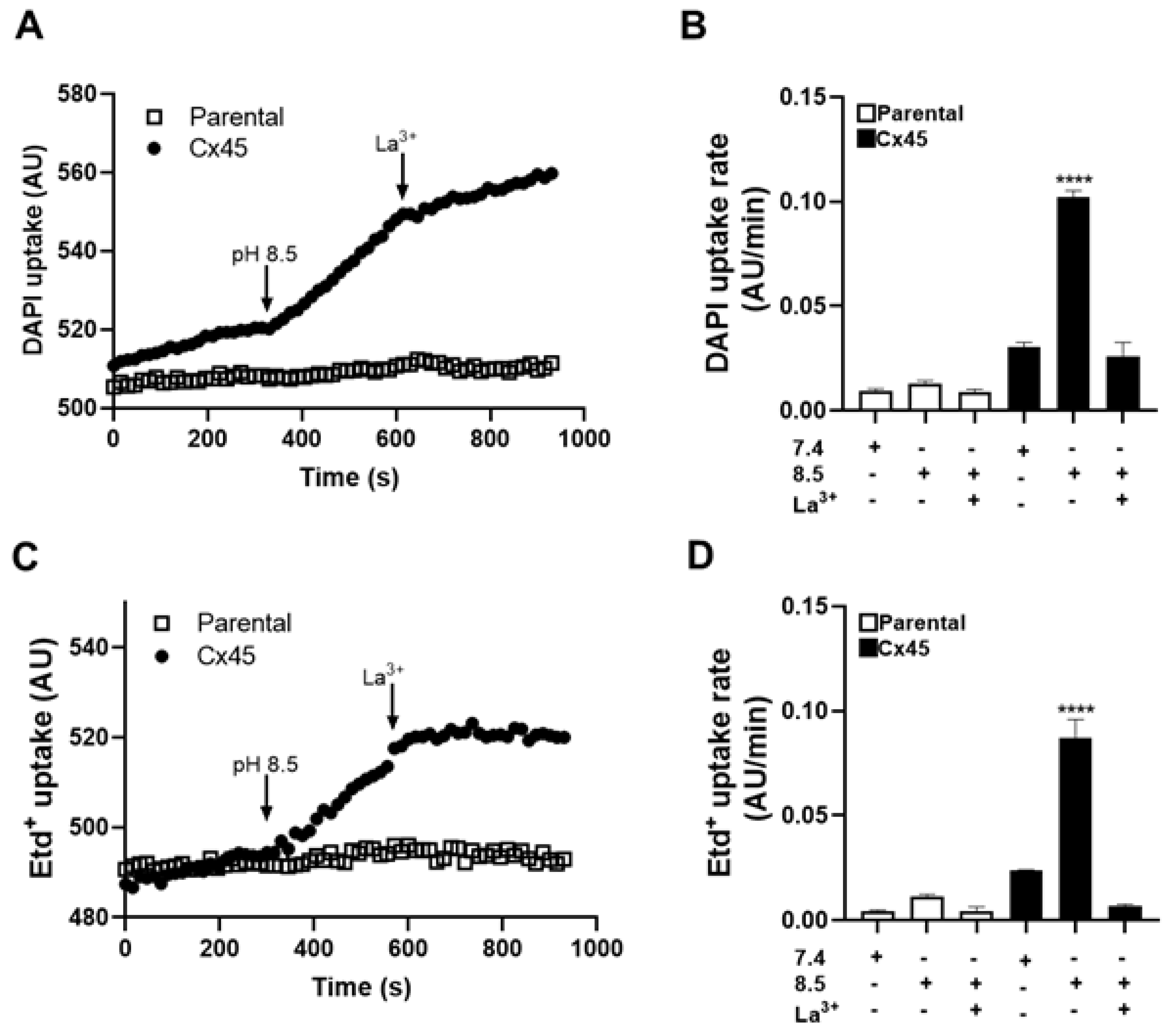

2.1. Extracellular Alkaline Solution Increases Cell Membrane Permeability Through Cx45 Hemichannels

It has been previously reported that extracellular alkaline solution increases the activity of Cx43 and Cx39 HCs leading to an increase in Etd⁺ uptake [

11,

12]. In contrast, Panx1 HCs show minimal Etd⁺ uptake under basal or alkaline conditions; their activity is more reliably detected using DAPI [

13,

23]. Among the Cx HCs expressed in pathological conditions in skeletal muscle, Cx45 HCs have not yet been characterized for its behavior under alkaline conditions.

To elucidate the effect of extracellular alkaline solution on Cx45 HCs, we first evaluated DAPI uptake. Representative recordings of DAPI uptake over time in HeLa parental cells and HeLa-Cx45 cells are shown in (

Figure 1A). HeLa parental cells did not exhibit significant changes in uptake independent of the experimental conditions (

Figure 1A and B). In contrast, HeLa-Cx45 displayed a marked increase in DAPI uptake at pH 8.5 compared with pH 7.4 (~4-fold increase, p < 0.0001). This response was fully inhibited by 200 μM La³⁺, indicating that the effect was mediated by Cx45 HCs (

Figure 1A and B).

We next assessed Etd⁺ uptake under the same conditions. Representative time-lapse recordings of Etd⁺ uptake are shown in (

Figure 1C). Consistent with the results obtained with DAPI, HeLa parental cells showed no significant changes in Etd

+ uptake whereas HeLa-Cx45 exhibited a significant increase at pH 8.5 compared with pH 7.4 (~4-fold increase, p < 0.0001) (

Figure 1C and D). This effect was also fully blocked by 200 μM La³⁺, supporting the involvement of elevated Cx45 HC activity.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that extracellular alkaline solution enhanced the activity of Cx45 HCs, promoting permeability to both DAPI and Etd⁺, whereas parental cells did not show significant changes.

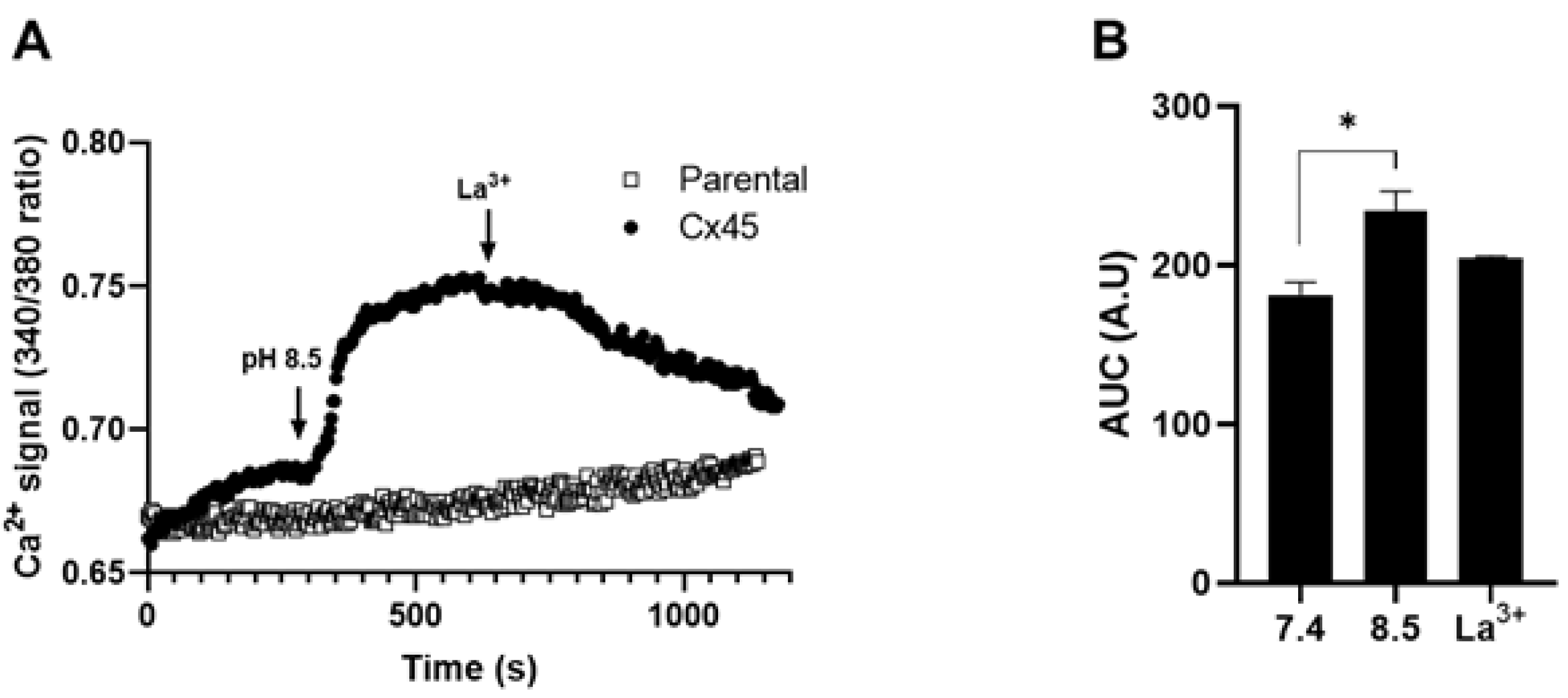

2.2. Extracellular Alkaline Solution Induces Ca2+ Influx in HeLa-Cx45 Cells

Increased permeability to Etd

+ and/or DAPI in Cx43, Cx39 and Panx1 HCs does not necessarily correlate with increased permeability to Ca²⁺ [

12,

13]. This prompted us to test whether Cx45 HCs are permeable to Ca²⁺. For this purpose, we evaluated intracellular Ca²⁺ dynamics using the ratiometric indicator Fura-2 AM in HeLa-Cx45 cells. Exposure of these cells to extracellular pH 8.5 induced a rapid and sustained increase in the 340/380 ratio of Fura-2 emitted fluorescence, consistent with Ca²⁺ influx (

Figure 2A). Quantitative analysis of the area under the curve (AUC) demonstrated a significant increase in intracellular free Ca

2+ concentration at pH 8.5 compared with pH 7.4 (p < 0.05); this effect was prevented by La³⁺ (

Figure 2B). These findings indicate that the extracellular alkalinization-induced opening of Cx45 HCs also allows Ca

2+ to permeate and enter the cells.

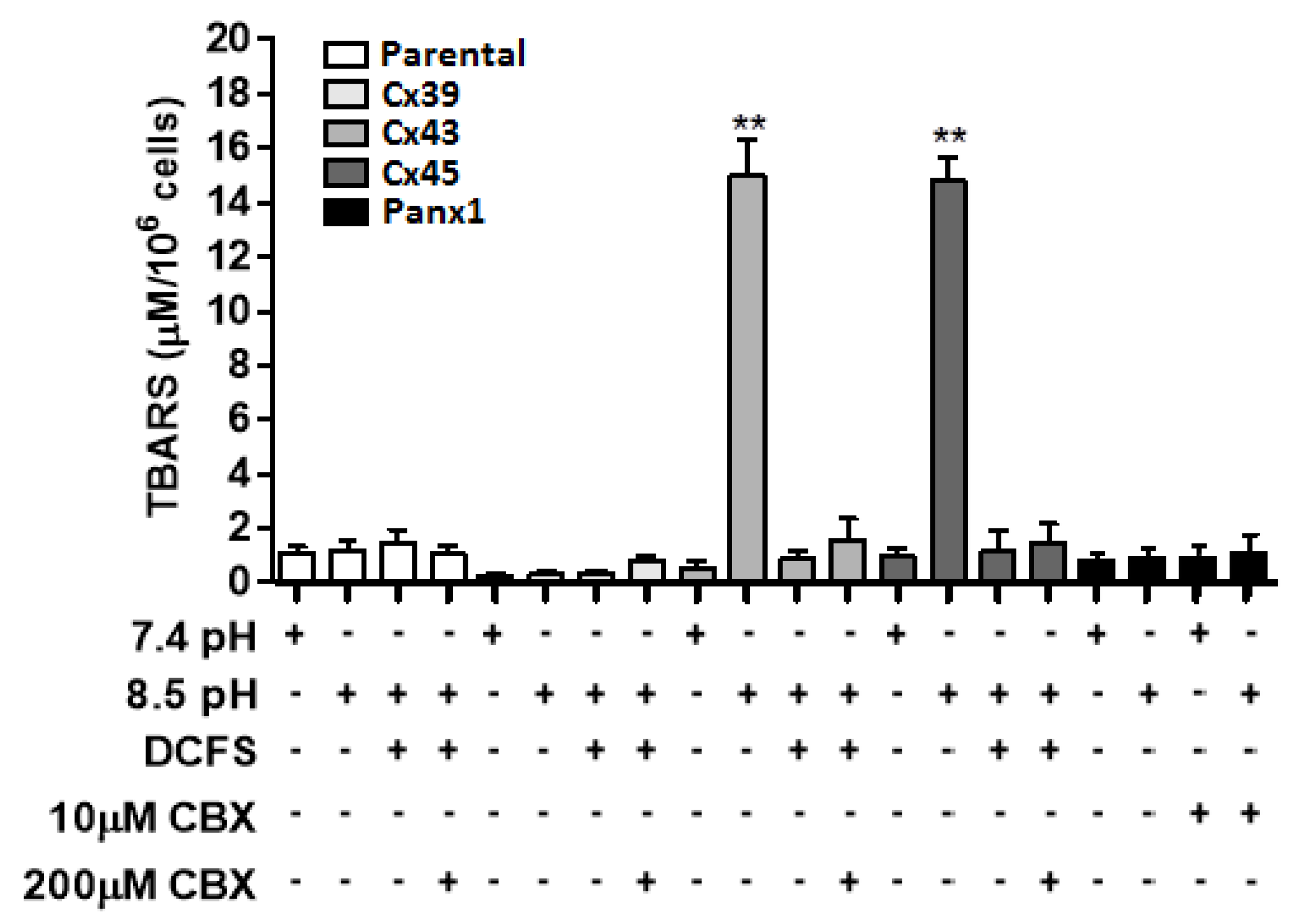

2.3. Exposure to Extracellular Alkaline Solution Induces Oxidative Stress only in HeLa-Cx43 and HeLa-Cx45 Cells

Since increases in the intracellular free Ca

2+ and/or Mg

2+ concentration are directly associated with increases in cellular oxidative state [

24,

25], we evaluated whether exposure of HeLa-Cx43 or HeLa-Cx45 cells to divalent cation-containing extracellular alkaline solutions for 1 h altered the amount of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), are commonly used as biomarkers of lipid peroxidation and reflect the degree of oxidative stress Levels of TBARS increased from 0.53 μM/10

6 cells at pH 7.4 to 15.10 μM/10

6 cells at pH 8.5 in HeLa-Cx43 cells (

Figure 3). Similarly, the amount of TBARS in HeLa-Cx45 cells increased from 0.98 μM/10

6 cells at pH 7.4 to 14.90 μM/10

6 cells at pH 8.5 (

Figure 3). These increases in TBARS levels were abrogated by 5 min pretreatment of HeLa-Cx43 or HeLa-Cx45 cells with 200 μM CBX, and they did not occur in DCFS. In contrast, the amounts of TBARS in HeLa parental, HeLa-Cx39 and HeLa-Panx1 cells were not significantly affected by changing the extracellular pH from 7.4 to 8.5 and in Panx1 HeLa cells pretreatment with 10 μM CBX was without significant effect (

Figure 3).

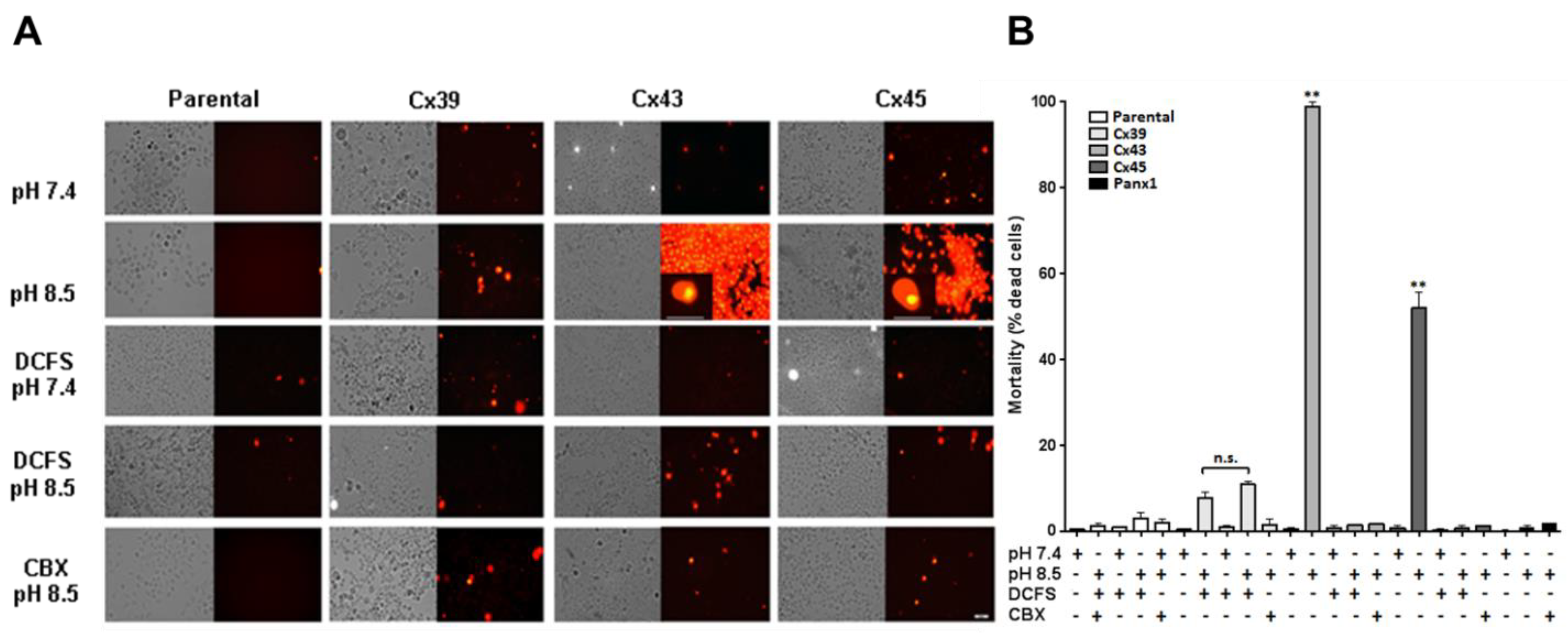

2.4. The Extracellular Alkaline Solution-Induces Cell Death of Cx43 and Cx45 HCs but not Cx39 and Panx1 HCs HeLa Transfectants

Increases in intracellular free Ca

2+ concentration and/or oxidative stress induce cell death [

26], and Ca

2+ or Mg

2+ overload leads to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by activating several intracellular pathways [

25,

27]. Because some of the HeLa transfectants showed an increase in both intracellular Ca

2+ signal and TBARS when exposed to extracellular alkaline solution, we evaluated whether these changes were associated with cell death. For this purpose, cells were exposed to alkaline (pH 8.5) or physiological (pH 7.4) Krebs-Ringer solution in the presence or absence of extracellular divalent cations for 3 h. We found that 98.9% of HeLa-Cx43 cells stained with propidium iodide at pH 8.5 compared to 5.8% extracellular pH 7.4; these cells were scored dead (

Figure 4). The same treatment caused 52.1% mortality in HeLa-Cx45 cells vs. 1.6% at pH7.4 (

Figure 4). In contrast, much lower levels of mortality were scored at pH 8.5 in HeLa parental cells (1.4%), HeLa-Cx39 cells (7.9%) and HeLa-Panx1 cells (0.9%); these values were not significantly different than those obtained at pH 7.4 (

Figure 4). In addition, no significant cell death was scored in any of the Cx transfectants after 3 h exposure to DCFS regardless of whether the pH was 7.4 or 8.5 (

Figure 4). Indeed, mortality in DCFS pH 8.5 in HeLa parental, HeLa-Cx39, HeLa-Cx43 and HeLa-Cx45 cells was 3.0%, 10.9%, 1.6% and 0.8%, respectively (

Figure 4).

The presence of 200 μM CBX prevented the increase in cell mortality induced in HeLa-Cx43 and HeLa-Cx45 cells by exposure to DCFS, pH 8.5. Under these conditions, mortality was only 1.7% in Hela-Cx43 and 1.4% in HeLa-Cx45 cells (

Figure 4). Mortality also decreased in CBX-treated HeLa-Cx39, reaching a value of 1.6% (

Figure 4). No significant changes were detected in cell mortality of Hela parental and HeLa-Panx1 exposed to 200 µM CBX (

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

In the present work, we demonstrated that extracellular alkaline solution promotes the activity of HCs formed by Panx1 and different Cxs, but only cells expressing Cx43 or Cx45 exhibited a sustained increase in cytosolic Ca²⁺, elevated TBARS levels, and reduced cell viability. These responses were inhibited by CBX and were also prevented by absence of extracellular divalent cations, indicating that the Ca2+ responsible for the rise in the intracellular Ca²⁺ concentration originate from the extracellular space. Thus, our findings identify that Cx45 forms HCs that allow Ca²⁺ influx under alkaline conditions, thereby leading to oxidative stress and cell death. We also confirmed that Cx43 HCs are permeable to Ca2+ and showed that this response promotes oxidative stress and cell death.

3.1. Activation of Connexin45 Hemichannels by Extracellular Alkaline Solution.

It has been previously reported that exposure of HeLa-Cx43 cells to extracellular alkalinization (pH 8.5) enhances Etd⁺ uptake by increasing the activity of Cx43 HC. [

11]. We found that the Cx45 HC activity was also rapidly increased by extracellular alkaline pH. This permeability profile is not shared by all HCs. For instance, Cx39 and Cx43 HCs are permeable to both DAPI and Etd⁺ [

12,

28], while full-length Panx1 HCs allow DAPI but not Etd⁺ entry unless the protein is truncated at the C-terminal domain [

13]. These observations indicate that Cx45 HCs share the dye permeability properties of other Cx HCs but differ from those of full-length Panx1 HCs.

Previous studies have shown that both Cx43 and Cx45 gap junction channels exhibit pH-dependent modulation of gating, with alkalinization favoring channel opening [

29,

30]. Our results are consistent with these findings, extending the concept to Cx45 HCs at the plasma membrane. Interestingly, pH sensitivity also appears conserved across different channel families, since HCs from zebrafish Panx1 have been shown to increase dye uptake in response to alkaline conditions [

31]. Together, these observations reinforce the idea that extracellular alkalinization promotes HC activity through a conserved mechanism of pH-dependent gating.

The effect of alkaline pH on Cx45 HCs may involve changes in gating dynamics. Previous studies have shown that extracellular Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ critically modulate HC activity by stabilizing the closed conformation [

11,

32,

33]. In the case of Cx43, reducing extracellular Ca

2+ expands the estimated pore diameter from ~1.8 nm (closed state) to ~2.5 nm (open state) [

32]. A similar regulation has been suggested for other Cxs. Our finding that activity of Cx45 HC increases under alkaline pH in the presence of physiological concentrations of Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ suggests that extracellular alkalinization acts by altering the open probability and/or open time of the HCs. Whether this involves conformational changes in the pore architecture or an increased number of active HCs at the cell surface remains to be determined.

3.2. Differential Permeability of Cx HCs to Ca2+

Differences in Ca²⁺ permeability have been reported among connexin HCs. For instance, although Cx39 HCs are permeable to DAPI and Etd⁺, they do not permeable to Ca²⁺ when activated by extracellular alkaline solution [

12]. Similarly, full-length Panx1 HCs do not allow Ca²⁺ entry under extracellular alkalinization [

13,

23], although truncation of the C-terminal domain renders them Ca²⁺-permeable [

13]. In contrast, Cx43 HCs are permeable to Ca²⁺ upon alkalinization [

11].

Here we showed that Cx45 HCs also mediated Ca

2+ influx in response to extracellular alkaline solution. This finding is consistent with previous work showing that stimulation of HeLa-Cx45 cells with FGF-1 for 7 h induced a rise in intracellular Ca

2+ [

34]. However, our results revealed that acute exposure to an alkaline extracellular solution containing physiological concentrations of Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ is sufficient to rapidly increase cytosolic Ca

2+ through Cx45 HCs. In agreement, removal of extracellular divalent cations completely abolished the alkalinization-induced rise in cytosolic Ca

2+, confirming that the observed signal arises from Ca

2+ influx rather than mobilization from intracellular stores.

3.3. Production of Reactive Oxidative Species and Cell Death of HeLa-Cx43 and HeLa-Cx45 Cells Exposed to Extracellular Alkaline pH

The induction of oxidative stress by extracellular alkalinization was restricted to cells expressing Cx43 or Cx45 whose HCs (unlike those of Cx39 and Panx1) are permeable to Ca

2+. These findings are consistent with the notion that intracellular Ca

2+ overload is a well-established trigger of oxidative stress, since it activates enzymes such as lipoxygenases, cyclooxygenases, and NADPH oxidases, and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction, all of which amplify ROS generation [

24,

35,

36]. When ROS production exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the cell, oxidative stress ensues, resulting in damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, processes that underlie numerous pathological conditions [

37]. These mechanisms provide a strong explanation for our observations, linking Ca

2+ entry through Cx43 and Cx45 HCs to ROS production and subsequent cell death. This conclusion is also consistent with the observation that

in vivo treatment with dexamethasone induces Cx39, Cx43 and Cx45 expression and increases oxidative stress in skeletal muscle, effects that do not occur in mice with muscle-specific deletion of Cx43 and Cx45 [

22]. Since Cx39 HCs are not permeable to Ca

2+, these results suggest that HC-dependent induction of oxidative stress requires HC-mediated Ca

2+ permeation.

The role of Cx43 in oxidative stress and apoptosis is supported by several independent studies. In endothelial cells, LPS stimulation increases Cx43 protein levels at the plasma membrane, which correlates with enhanced ROS generation and apoptosis. Selective inhibition of Cx43 HCs with Gap19 abolished these responses, demonstrating that Cx43 HC activity at the membrane is required for oxidative damage [

38]. Likewise, Cx43 HCs mediate the propagation of Ca

2+, ATP, ROS and NO signaling in radiation-induced bystander effects, where DNA damage in non-irradiated endothelial cells is dependent on HC activity [

39]. Together, these studies and the data presented here establish Cx43 as a central mediator of Ca

2+-dependent oxidative stress and cell death in different pathological conditions.

Our findings extend this conclusion to Cx45, which had not previously been linked to ROS production. We demonstrated that extracellular alkalinization triggers a Ca

2+ influx through Cx45 HCs, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and reduced cell viability. Both effects were prevented by carbenoxolone or by removal of extracellular Ca

2+, suggesting that Ca

2+ entry through Cx45 HCs is the initiating event. This is the first evidence that Cx45 HCs are permeable to Ca

2+ and that their elevated activity directly promotes oxidative stress and cell death. Since cell death could also be promoted by increased cytoplasmic levels of Mg

2+ or Zn

2+ [

25], and the possibility that Cx HCs permeable to Ca

2+ could be share to these two divalent cations, further studies will be required to dissect if cell death induced by alkaline pH is due only to the influx of Ca

2+, Mg

2+ or Zn

2+ or two of them or all of them. In this respect it is worth mentioning that genetic ablation of Cx45 reduced retinal cell loss by about 50% under ischemic conditions, indicating that this Cx contributes to neuronal death

in vivo [

40] reinforces the idea that Cx45 HCs can critically modulate cell fate under stress.

The concept that HC opening can contribute to oxidative stress is supported by evidence from other Cxs and Panxs. In other cellular contexts, aberrant HC activity has been shown to promote apoptosis [

41], and gain-of-function mutations in Cx31 cause excessive HC opening directly associated with ROS accumulation and necrotic cell death [

7] as well as gain of function of Cx26 mutant forming heteromeric hemichannels with Cx30 [

42]. Within this framework, our results identify Cx45 HCs as novel contributors to Ca

2+–dependent oxidative stress.

Given that aberrant expression of Cx43 and Cx45 occurs in skeletal muscle under diverse pathological conditions, including muscular diseases [

17], our results suggest that Cx45 may represent a previously unrecognized contributor to oxidative damage

in vivo and a potential pharmacological target for diseases associated with oxidative stress.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Ethidium (Etd+) bromide, and carbenoxolone (CBX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). DAPI and Fura-2 AM were obtained from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). Stably transfected clones were selected by their resistance to 0.5 mg/mL puromycin and 0.3 mg/mL geneticin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

4.2. Cell Cultures

Parental cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). HeLa cells transfected with mouse Cxs 39, 43, 45 (HeLa-Cx39, HeLa-Cx43, HeLa-Cx45, respectively) were kindly provided by Dr. Klaus Willecke, University of Bonn, Germany. HeLa cells stably transfected with mouse Panx1 (HeLa-Panx1) were obtained from Dr. Felixas Bukaukas, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA. All cells were cultured on plastic tissue culture dishes (Nunc, NY, USA) in DMEM medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and were maintained in incubators at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 98% relative humidity. Sub-confluent cultures (~70%) were used in all experiments.

4.3. Extracellular Solution

Cells were bathed with Krebs-Ringer solution (in mM: 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5.6 C6H12O6, 10 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4 or pH 8.5) or divalent cation (Ca2+ and Mg2+)-free solution (DCFS: Krebs-Ringer solution without divalent cations) (in mM: 154 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 5 C6H12O6, 10 HEPES and 0.5 EGTA, pH 7.4 or pH 8.5). The final pH of each solution was adjusted to the desired value using Tris base.

4.4. Ethidium (Etd+) and DAPI Uptake

Cells were plated on glass coverslips (25 mm in diameter; Marienfeld, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany) and maintained in tissue culture medium for 48 h. then, they were bathed with Krebs-Ringer solution (pH 7.4 or pH 8.5) or DCFS (pH 7.4 or pH 8.5) containing 5 µM ethidium (Etd

+) bromide or 5 µM DAPI. Etd

+ uptake was evaluated in HeLa-Cx39, HeLa-Cx43 and HeLa-Cx45 cells and DAPI uptake was evaluated in HeLa-Panx1 cells. Subsequently, the HC activities of Cx or Panx1 HeLa transfectants were evaluated in solutions containing, respectively, 200 µM CBX, a widely used Cx and Panx1 HC blocker [

43]. The fluorescence intensity was recorded in regions of interest corresponding to the nuclei of at least 20 cells and were viewed using an Olympus model BX41TF (Center Valley, PA, USA). All images were captured every 15 sec with a QImaging model Retiga 13001 fast cooled 12-bit monochromatic digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). The fluorescence emissions of Etd

+ and DAPI bound to nucleic acids were recorded at 595 nm and 461 nm, respectively.

4.5. Intracellular Ca2+ Signal

Cells cultured in coverslips for 48 h were loaded with 2 µM Fura-2 AM for 45 min. Cells were imaged every 3 s using a conventional Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Tokio, Japan) to record the Fura-2 fluorescence intensities emitted at 510 nm following excitation at 340 and 380 nm. The Ca2+ signals were quantified as the 340/380 ratio of the emitted fluorescence intensities.

4.6. Quantification of Cellular TBARS

Cells were exposed for 1 h at 37ºC ± 1ºC to Krebs-Ringer solution, pH 7.4 or pH 8.5, Ca

2+- and Mg

2+-free Krebs-Ringer solution, pH 8.5, or they were pretreated for 15 min with 200 μM CBX (in the case of Cx transfectants) or 10 μM CBX (in the case of Panx1 transfectants) and kept in the presence of the inhibitor during the 1 h exposure to DCFS, pH 8.5. Then, cells were harvested in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline solution using a cell scraper and lysed by three 1-second sonication events. The content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) was measured in aliquots from the whole homogenates using a lipid peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). In this kit, malondialdehyde (MDA) reacts with thiobarbituric acid to produce stable chromogenic adducts that can be quantified spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at λ = 532 nm. The amounts of TBARS in the samples were calculated by interpolation of the measured absorbance on a standard curve obtained with MDA [

44].

4.7. Quantification of Cell Death

HeLa cells were exposed to either Krebs-Ringer solution, pH 7.4 or 8.5 for 3 h. In some experiments, cells were exposed for 3 h to DCFS, pH 7.4 or pH 8.5 at 37ºC ± 1ºC or they were pretreated and kept in the presence of 10 μM CBX (for Panx1 transfectants) or 200 μM CBX (for all transfectants) during the 3 h exposure to one of the extracellular solutions. Then, cells were incubated for 5 min with Krebs-Ringer solution containing 5 µM propidium iodide (plus added CBX only for cells that had been treated with this drug). Pictures of 5 different fields were taken in an Olympus model BX41TF microscope equipped with epifluorescence illumination (λex 535 nm and λem 617 nm) using a 20X objective (Olympus UPlanFL N, NA = 0.50). The total number of cells and the number of cells stained with propidium iodide were quantified in each picture.

4.8. Image Analysis and Statistical Analysis

Fluorescence images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.64r) (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Graphs and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (San Diego, CA, EE.UU.). Statistical significance was determined by the Mann Whitney U test or using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.V., C.U. and J.C.S.;methodology, W.V., C.U., X.L., L.A.C., J.L.V., V.M.B. and J.C.S.;software, W.V., C.U., X.L., L.A.C., J.L.V. and V.M.B.;validation, W.V., C.U. and J.C.S.;formal analysis, W.V., C.U. and J.C.S.;investigation, W.V., C.U., X.L., L.A.C., J.L.V., V.M.B. and J.C.S.;resources, J.C.S.;data curation, W.V., C.U., X.L., L.A.C., J.L.V. and V.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.V., C.U. and J.C.S.;writing—review and editing, W.V., C.U., V.M.B. and J.C.S.;visualization, W.V., C.U. and J.C.S.;supervision, J.C.S.;project administration, J.C.S.;funding acquisition, J.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT), grant No. 1231523 (to J.C.S.); by the Millennium Science Initiative Program, grant ICN2025_026, Instituto Milenio Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencias de Valparaíso (CINV) (to J.C.S.); by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT), Chile (grant No. 1231325, to J.C.S.); and by a MINEDUC–Universidad de Antofagasta project, code ANT 1755 (to J.L.V.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

W.V. was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) (grant No. 21211179). X.L. was supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT), Chile. Part of the data presented in this manuscript derives from the doctoral thesis of W.V., submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Biological Sciences, with a mention in Physiological Sciences, at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBX |

Carbenoxolone |

| Cx |

Connexin |

| DCFS |

Divalent cation-free solution |

| DAPI |

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| Etd⁺ |

Ethidium |

| HC |

Hemichannel |

| Panx1 |

Pannexin 1 |

| PI |

Propidium iodide |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| FGF-1 |

Fibroblast growth factor 1 |

| TBARS |

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

References

- Beyer, E.C.; Berthoud, V.M. Gap junction gene and protein families: Connexins, innexins, and pannexins. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Orozco, I.J.; Du, J.; Lü, W. Structures of human pannexin 1 reveal ion pathways and mechanism of gating. Nature 2020, 584, 646–651. [CrossRef]

- Sáez, J.C.; Leybaert, L. Hunting for connexin hemichannels. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 1205–1211. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Soleymani, S.; Madakshire, R.; Insel, P.A. ATP released from cardiac fibroblasts via connexin hemichannels activates profibrotic P2Y 2 receptors. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 2580–2591. [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, M.A.; Cea, L.A.; Vega, J.L.; Boric, M.P.; Monyer, H.; Bennett, M.V.; Frank, M.; Willecke, K.; Sáez, J.C. The ATP required for potentiation of skeletal muscle contraction is released via pannexin hemichannels. Neuropharmacology 2013, 75, 594–603. [CrossRef]

- Orellana, J.A.; Hernández, D.E.; Ezan, P.; Velarde, V.; Bennett, M.V.L.; Giaume, C.; Sáez, J.C. Hypoxia in high glucose followed by reoxygenation in normal glucose reduces the viability of cortical astrocytes through increased permeability of connexin 43 hemichannels. Glia 2009, 58, 329–343. [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Tan, J.; Tang, C.; Pan, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z. Pathogenic Connexin-31 Forms Constitutively Active Hemichannels to Promote Necrotic Cell Death. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e32531. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Riquelme, M.A.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Nicholson, B.J.; Gu, S.; Jiang, J.X. Cataract-Causing Mutation of Human Connexin 46 Impairs Gap Junction, but Increases Hemichannel Function and Cell Death. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e74732. [CrossRef]

- Zhivotovsky, B.; Orrenius, S. Calcium and cell death mechanisms: A perspective from the cell death community. Cell Calcium 2011, 50, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Fiori, M.C.; Figueroa, V.; Zoghbi, M.E.; Saéz, J.C.; Reuss, L.; Altenberg, G.A. Permeation of Calcium through Purified Connexin 26 Hemichannels. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 40826–40834. [CrossRef]

- Schalper, K.A.; Sánchez, H.A.; Lee, S.C.; Altenberg, G.A.; Nathanson, M.H.; Sáez, J.C. Connexin 43 hemichannels mediate the Ca2+ influx induced by extracellular alkalinization. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2010, 299, C1504–C1515. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.A.; Cisterna, B.A.; Saavedra-Leiva, F.; Urrutia, C.; Cea, L.A.; Vielma, A.H.; Gutierrez-Maldonado, S.E.; Martin, A.J.M.; Pareja-Barrueto, C.; Escalona, Y.; et al. On Biophysical Properties and Sensitivity to Gap Junction Blockers of Connexin 39 Hemichannels Expressed in HeLa Cells. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 38. [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.; Márquez-Miranda, V.; Ferrada, L.; Rojas, M.; Poblete-Flores, G.; González-Nilo, F.D.; Ardiles, Á.O.; Sáez, J.C. Ca2+permeation through C-terminal cleaved, but not full-length human Pannexin1 hemichannels, mediates cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Carette, D.; Gilleron, J.; Chevallier, D.; Segretain, D.; Pointis, G. Connexin a check-point component of cell apoptosis in normal and physiopathological conditions. Biochimie 2014, 101, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Poon, I.K.H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Armstrong, A.J.; Kinchen, J.M.; Juncadella, I.J.; Bayliss, D.A.; Ravichandran, K.S. Unexpected link between an antibiotic, pannexin channels and apoptosis. Nature 2014, 507, 329–334. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.Y.; Fritton, J.C.; Morgan, S.A.; Seref-Ferlengez, Z.; Basta-Pljakic, J.; Thi, M.M.; O Suadicani, S.; Spray, D.C.; Majeska, R.J.; Schaffler, M.B. Pannexin-1 and P2X7-Receptor Are Required for Apoptotic Osteocytes in Fatigued Bone to Trigger RANKL Production in Neighboring Bystander Osteocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 31, 890–899. [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, W.; Toro, C.A.; Cardozo, C.P.; Cea, L.A.; Sáez, J.C. Pathophysiological role of connexin and pannexin hemichannels in neuromuscular disorders. J. Physiol. 2024, 603, 4213–4235. [CrossRef]

- Abruzzo, P.M.; di Tullio, S.; Marchionni, C.; Belia, S.; Fanó, G.; Zampieri, S.; Carraro, U.; Kern, H.; Sgarbi, G.; Lenaz, G.; et al. Oxidative stress in the denervated muscle. Free. Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 563–576. [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Whitehead, N.P.; Froehner, S.C. Absence of Dystrophin Disrupts Skeletal Muscle Signaling: Roles of Ca2+, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Nitric Oxide in the Development of Muscular Dystrophy. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 253–305. [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.G.; Llesuy, S.; Evelson, P.; Carreras, M.C.; Flecha, B.G.; Poderoso, J.J. Oxidative stress in skeletal muscle during sepsis in rats.. 1993, 39, 153–9.

- McClung, J.M.; Judge, A.R.; Powers, S.K.; Yan, Z. p38 MAPK links oxidative stress to autophagy-related gene expression in cachectic muscle wasting. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010, 298, C542–C549. [CrossRef]

- Balboa, E.; Saavedra, F.; Cea, L.A.; Ramírez, V.; Escamilla, R.; Vargas, A.A.; Regueira, T.; Sáez, J.C. Vitamin E Blocks Connexin Hemichannels and Prevents Deleterious Effects of Glucocorticoid Treatment on Skeletal Muscles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4094. [CrossRef]

- Harcha, P.A.; López, X.; Sáez, P.J.; Fernández, P.; Barría, I.; Martínez, A.D.; Sáez, J.C. Pannexin-1 Channels Are Essential for Mast Cell Degranulation Triggered During Type I Hypersensitivity Reactions. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2703. [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Duarte, J.; Kavazis, A.N.; Talbert, E.E. Reactive oxygen species are signalling molecules for skeletal muscle adaptation. Exp. Physiol. 2009, 95, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Su, L.-T.; González-Pagán, O.; Overton, J.D.; Runnels, L.W. A key role for Mg2+ in TRPM7's control of ROS levels during cell stress. Biochem. J. 2012, 445, 441–448. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Cho, H.; Yu, S.; Kim, S.; Yu, H.; Park, Y.; Mirkheshti, N.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, C.S.; Chatterjee, B.; et al. Interplay of reactive oxygen species, intracellular Ca2+ and mitochondrial homeostasis in the apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by deoxypodophyllotoxin. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 114, 1124–1134. [CrossRef]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 260–271. [CrossRef]

- Sáez, J.C.; Vargas, A.A.; Hernández, D.E.; Ortiz, F.C.; Giaume, C.; Orellana, J.A. Permeation of Molecules through Astroglial Connexin 43 Hemichannels Is Modulated by Cytokines with Parameters Depending on the Permeant Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3970. [CrossRef]

- Hermans, M.M.P.; Kortekaas, P.; Jongsma, H.J.; Rook, M.B. pH sensitivity of the cardiac gap junction proteins, connexin 45 and 43. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1995, 431, 138–140. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Prado, N.; Briggs, S.W.; Skeberdis, V.A.; Pranevicius, M.; Bennett, M.V.L.; Bukauskas, F.F. pH-dependent modulation of voltage gating in connexin45 homotypic and connexin45/connexin43 heterotypic gap junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 9897–9902. [CrossRef]

- Kurtenbach, S.; Prochnow, N.; Kurtenbach, S.; Klooster, J.; Zoidl, C.; Dermietzel, R.; Kamermans, M.; Zoidl, G. Pannexin1 Channel Proteins in the Zebrafish Retina Have Shared and Unique Properties. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e77722. [CrossRef]

- Contreras JE, Sáez JC, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MV. Functioning of Cx43 hemichannels demonstrated by single channel properties. Cell Commun Adhes. (2003). 10 (4-6), 245-249.

- Thimm, J.; Mechler, A.; Lin, H.; Rhee, S.; Lal, R. Calcium-dependent Open/Closed Conformations and Interfacial Energy Maps of Reconstituted Hemichannels. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10646–10654. [CrossRef]

- Schalper KA, Palacios-Prado N, Retamal MA, Shoji KF, Martínez AD, Sáez JC. Connexin hemichannel composition determines the FGF-1-induced membrane permeability and free [Ca 2+]i responses. Mol Biol Cell. (2008). 19(8), 3501-3513.

- Sáez, J.C.; A Kessler, J.; Bennett, M.V.; Spray, D.C. Superoxide dismutase protects cultured neurons against death by starvation.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987, 84, 3056–3059. [CrossRef]

- Brandes, R.P.; Weissmann, N.; Schröder, K. Nox family NADPH oxidases: Molecular mechanisms of activation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 76, 208–226. [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-W.; Ji, D.-D.; Li, Q.-Q.; Zhang, T.; Luo, L. Inhibition of connexin 43 attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hoorelbeke, D.; Decrock, E.; De Smet, M.; De Bock, M.; Descamps, B.; Van Haver, V.; Delvaeye, T.; Krysko, D.V.; Vanhove, C.; Bultynck, G.; et al. Cx43 channels and signaling via IP3/Ca2+, ATP, and ROS/NO propagate radiation-induced DNA damage to non-irradiated brain microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Akopian, A.; Atlasz, T.; Pan, F.; Wong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Völgyi, B.; Paul, D.L.; Bloomfield, S.A. Gap Junction-Mediated Death of Retinal Neurons Is Connexin and Insult Specific: A Potential Target for Neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 10582–10591. [CrossRef]

- Decrock E, Vinken M, De Vuyst E, Krysko DV, D’Herde K, Vanhaecke T, Vandenabeele P, Rogiers V, Leybaert L. Connexin-related signaling in cell death: to live or let die? Cell Death Differ. (2009). 16(4), 524-536.

- Abbott, A.C.; García, I.E.; Villanelo, F.; Flores-Muñoz, C.; Ceriani, R.; Maripillán, J.; Novoa-Molina, J.; Figueroa-Cares, C.; Pérez-Acle, T.; Sáez, J.C.; et al. Expression of KID syndromic mutation Cx26S17F produces hyperactive hemichannels in supporting cells of the organ of Corti. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 10, 1071202. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.V.L.; Garré, J.M.; A Orellana, J.; Bukauskas, F.F.; Nedergaard, M.; Sáez, J.C. Connexin and pannexin hemichannels in inflammatory responses of glia and neurons. Brain Res. 2012, 1487, 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Esterbauer, H.; Cheeseman, K.H.; Dianzani, M.U.; Poli, G.; Slater, T.F. Separation and characterization of the aldehydic products of lipid peroxidation stimulated by ADP-Fe2+ in rat liver microsomes. Biochem. J. 1982, 208, 129–140. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |