1. Introduction

Chloroquine (CQ) is a well-established antimalarial agent that is also widely used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis [

1]. Along with its derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), CQ has been extensively studied for potential antiviral activity, with efficacy demonstrated in both cell-culture systems and animal models. Owing to these properties, CQ and HCQ were among the earliest compounds investigated as experimental therapeutic candidates during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [

2,

3].

Chloroquine is an amphiphilic weak base that exists in both charged and uncharged forms. The molecule can adopt three protonation states: the neutral species (

CQ0), the monoprotonated species (

CQ+), and the diprotonated species (

CQ2+). The two basic ionization sites have pKₐ values of 8.4 and 10.8 at 20 °C, corresponding to the aromatic nitrogen and the tertiary diethylamino nitrogen, respectively [

4]. Under acidic or neutral conditions, chloroquine is largely protonated; however, at physiological pH (7.4), approximately 18% of the molecules are already in the monoprotonated form [

5]. In its deprotonated state, chloroquine can undergo prototropic tautomerism between amino and imino forms [

6].

Pharmaceutical compounds as CQ could exist in different chemical and solid-state forms that can significantly influence the bioavailability and the overall stability of the drug product as well as impact its manufacturability and storage properties [

7]. One common approach is the formulation of active ingredient as salt which can be produce using a variety of counterions although their choice is limited by toxicity criteria. For molecules with multiple protonation sites, salts corresponding to different protonation states can be obtained for each one different distinct hydration levels are potentially possible.

Chloroquine is typically administered as diphosphate or phosphate salt, and all commercially available formulations contain the racemic mixture [

8]. Bioactivity data have also been reported for the sulphate, di sulphate, and hydrochloride salts, these products are usually for in vitro studies and are not formulated for therapeutic use although the hydrochloride form has been used for intramuscular injection in cases of malaria-induced coma [

9]. Structural characterization has been carried out exclusively for the diphosphate salt at different degrees of hydration, in which chloroquine is present in the dicationic state [

10,

11,

12]. To date, no specific information is available regarding the protonation state of chloroquine in the other available salt forms.

The title compound CQCl·H2O (7-(Chloro-4-((4-diethylamino)-1-methylbutyl)amino)quinoline hydrochloride monohydrate), constitutes the first crystallographically characterized salt with chloride as the counterion and above all featuring monoprotonated chloroquine. Accordingly, its solid-state characterization is of considerable significance.

2. Results

2.1. Solid-State Structure

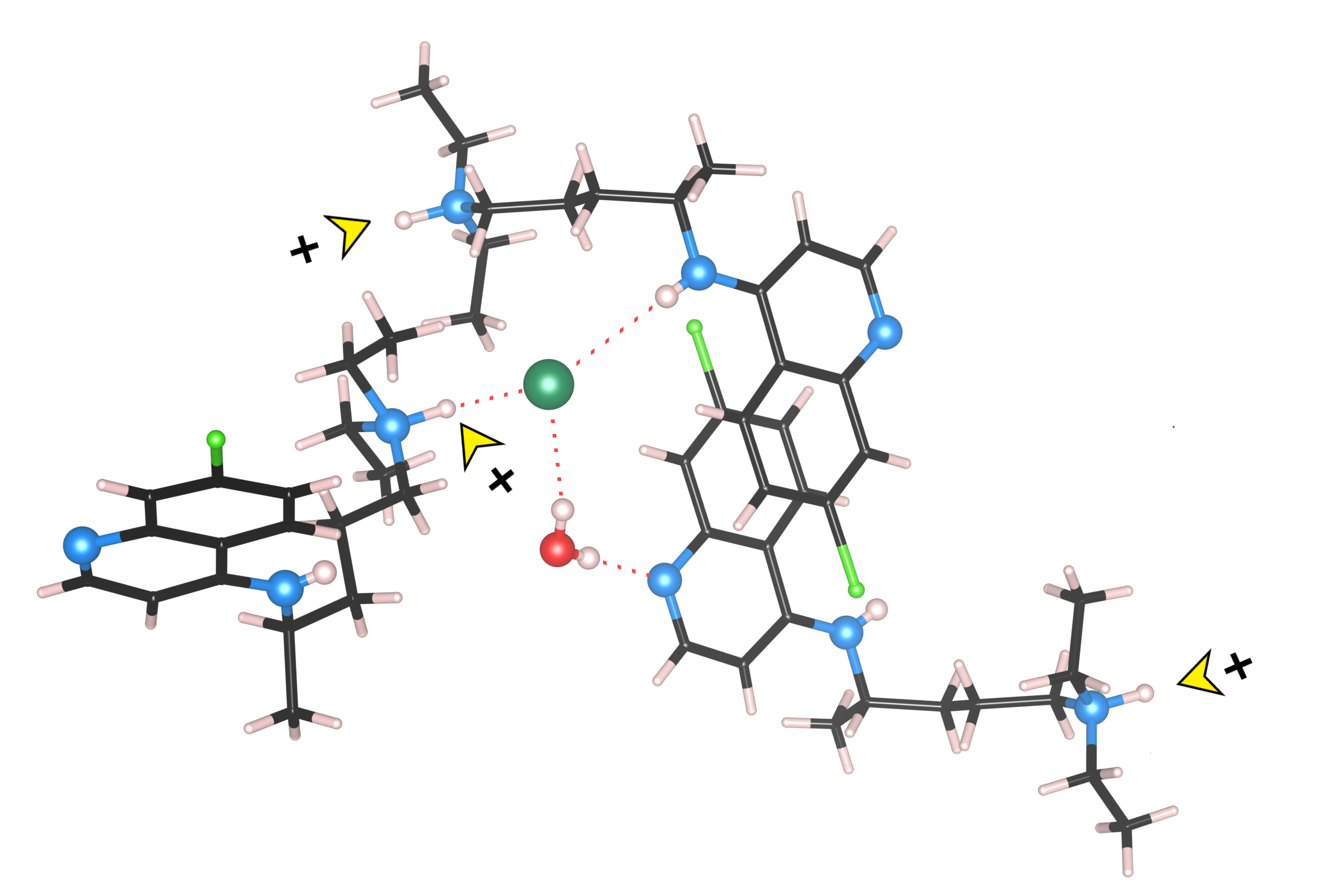

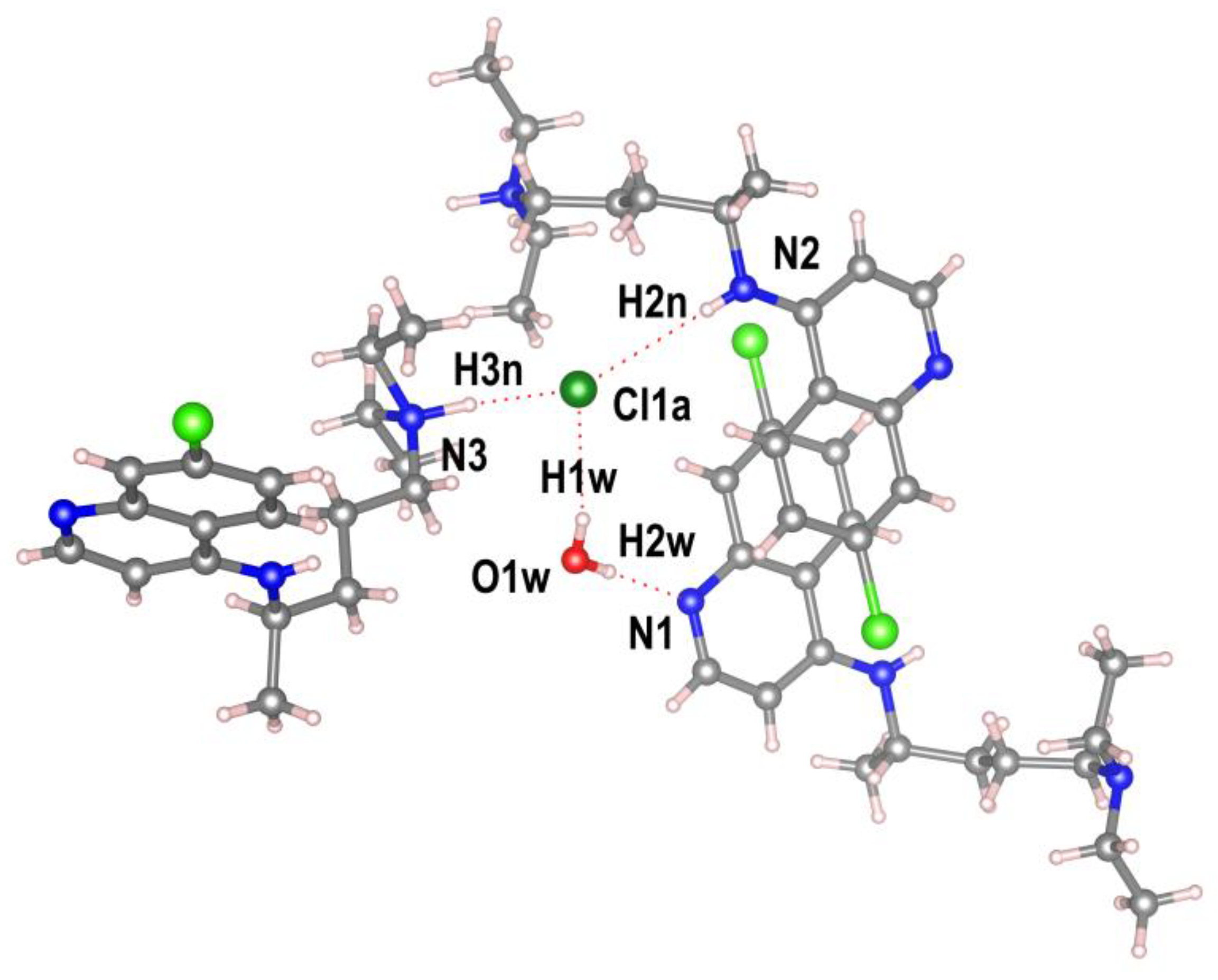

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data show that the

CQCl·H2O (7-(Chloro-4-((4-diethylamino)-1-methylbutyl)amino)quinoline hydrochloride monohydrate) compound crystallizes in the monoclinic space group

P21/c, with one mono-protonated chloroquine cation (CQH

+), one chloride anion (Cl

−), and one water molecule in the asymmetric unit (

Figure 1). In the chloroquine cation, as expected, the proton resides on the terminal diethylamino group. The chloroquine molecule adopts a condensed (folded) conformation in which the flexible diamino side chain loops back toward the aromatic core, creating a cavity (224.90 Å

3, 11.2% unit cell volume, probe 1.2 Å) that accommodates both the water molecule and the chloride anion, thereby maximizing attractive intermolecular interactions. Volumetric analysis indicates that this region forms isolated pockets within the crystal framework, lacking any detectable pathways for water molecules egress.

The quinoline double-ring shows a slight distortion from the planarity with a rms deviation from the best fit plane of 0.0348 Å and an out-of-plane deformation, measured by the torsion angle ϑ (C2-C3· · · C6-C7), of -2.81°.

The nitrogen atom of the secondary amine exhibits near-planarity, with a sum of bond angles (∑N) of 359.74°, closely approaching 360°, and an out-of-plane deviation (ΔN) of 0.032 Å relative to its bonded atoms. The N-C(pyridyl) bond length of 1.331(8) Å is significantly shorter than a typical single bond indicating partial double bond character arising from imino-type resonance. Additionally, the amino group is twisted out of the plane of the quinoline ring by an angle (φ) of 14.26°.

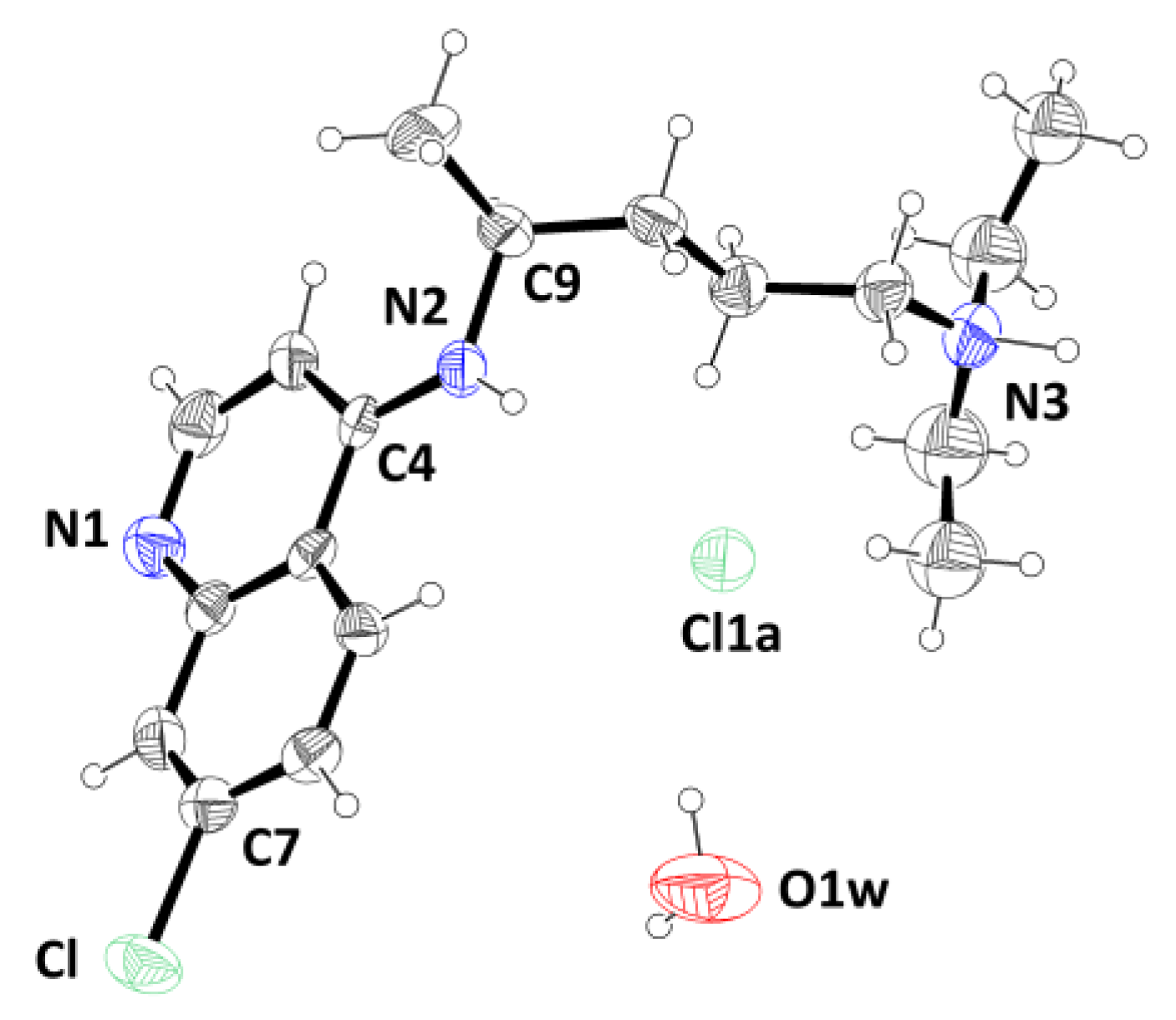

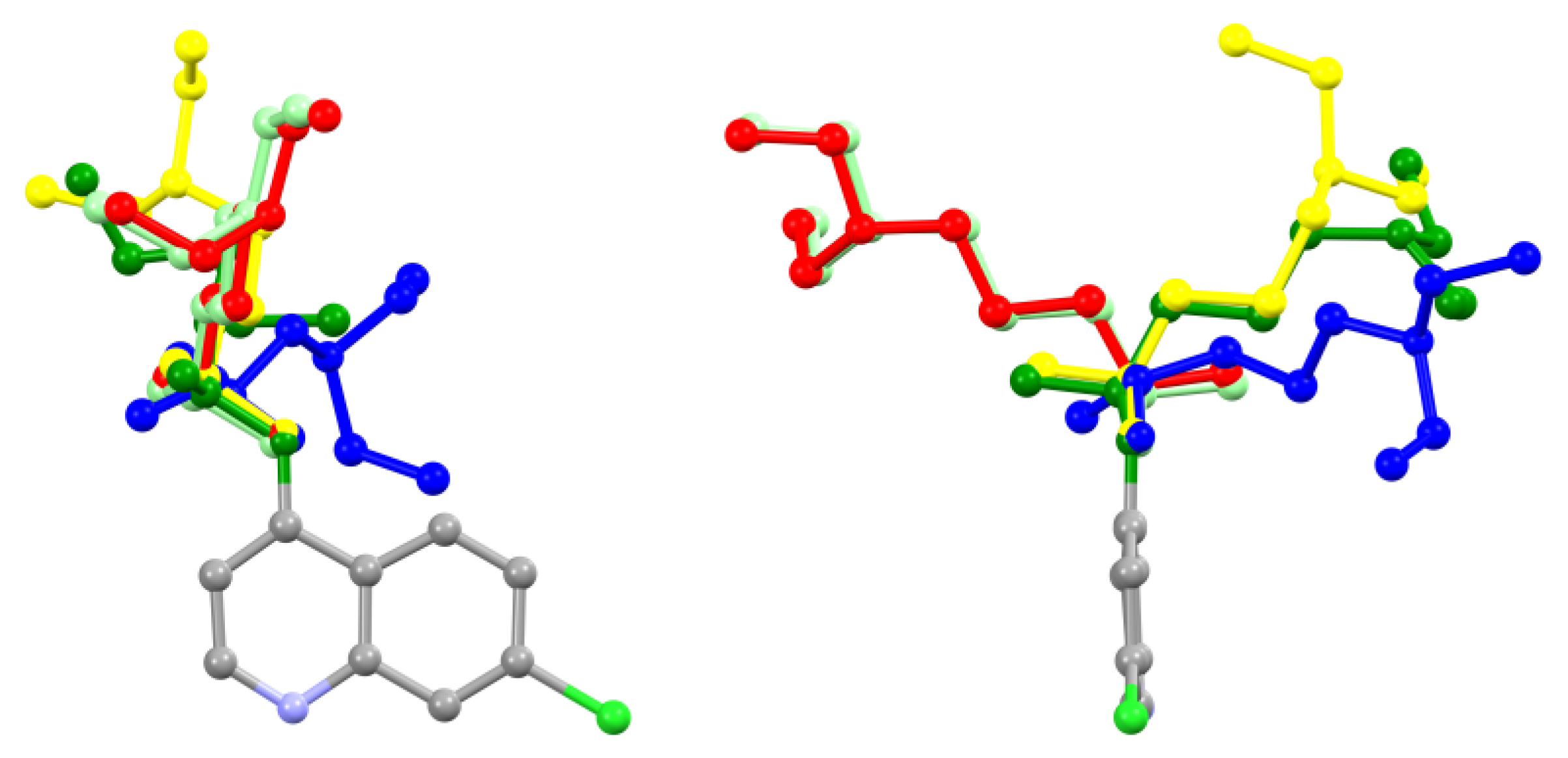

Comparison of the CQ and

CQCl·H2O crystal structures shows large conformational rearrangements upon protonation of the most basic nitrogen atom (4-diethylamino-1-methylbutyl-amino moiety). In

Figure 2 the conformations of unprotonated CQ and the doubly protonated dihydrogen phosphates of chloroquine (see caption of

Figure 2) are depicted with colour coding of the different crystal structures. Apart from the mono- and di-hydrated dihydrogen phosphate salts, which share almost the same conformation (red and light green chains in (

Figure 2) while having significantly different crystal structures, all 4-diethylamino-1-methylbutyl-amino chains adopt different conformations, both in terms of internal C—C—C—C torsional angles and rotation of the dangling group with respect to the quinoline frame. This happens due to the large number of freely rotating C—C single bonds that are adjusted for minimizing the lattice energy during crystallization, that frequently requires the presence of solvent molecules in the crystal structure. Interestingly, the conformation of the present hydrochloride partly overlaps with the neutral CQ molecule up to the last butyl carbon atom, leaving only the N(ethyl)

2 terminal moiety with different orientations (with heavy disorder of the ethyl groups in the monocation).

2.2. Intermolecular Interaction Analysis

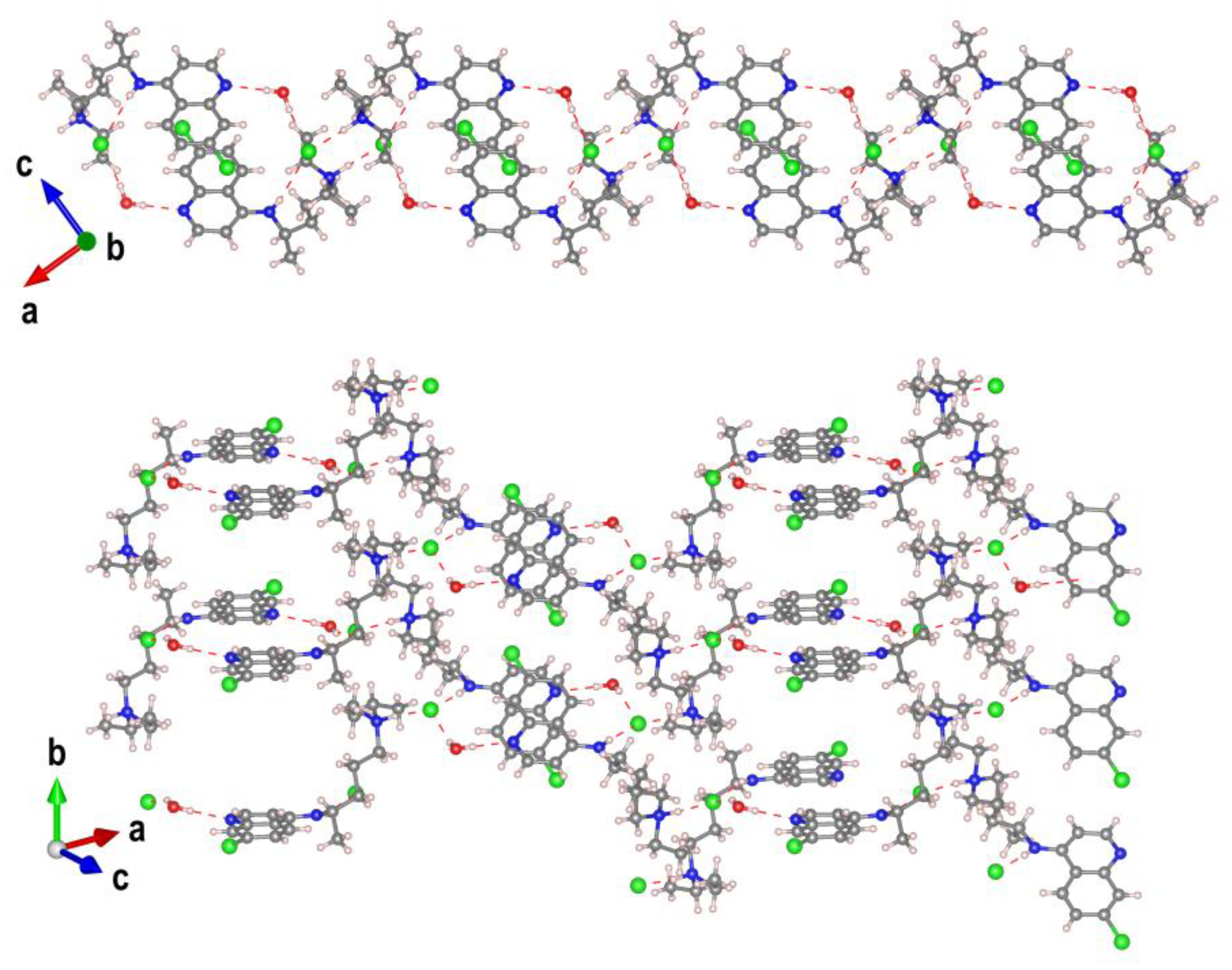

The crystal packing of

CQCl·H2O is stabilized by a large number of intermolecular O—H· · ·N, O—H· · ·Cl and N—H· · ·Cl hydrogen bonds generating an extensive bidimensional supramolecular arrangement extended along the (1 0 -2) plane (

Figure 3).

The water molecule functions as a double hydrogen-bond donor to the quinoline nitrogen atom and the chloride anion (O· · · N and Cl distance (Å), O—H· · · N and Cl angle (◦ ): 2.875(9), 179(1); 3.258(8), 156(1)) (

Table S2), and its oxygen atom serves as a hydrogen-bond acceptor in a weak intermolecular C—H· · ·O contact involving a methyl group of the pendant diethylamine (C—H· · ·O = 3.73(2) Å) (

Figure 4).

Similarly, the chloride anion acts as a proton acceptor from water molecule, the secondary aniline-type nitrogen of a chloroquine molecule and the protonated tertiary amino nitrogen of a nearby CQ

+ species (

Figure 4) (N· · · Cl distance (Å), N—H· · · Cl angle (◦ ): 3.522(9), 163(8); 3.098(8), 174(5) (

Table S2). A more detailed analysis further uncovers an array of weak intramolecular C—H

⋅⋅⋅Cl interactions that engage residues from both the side chain and the aryl ring of three adjacent chloroquine molecules. An empirical evaluation of the H-bond strengths in terms of the acid-base parameters has been performed and reported in ESI.

Around the inversion centres at (½, ½, ½) and (½, 0, 0), pairs of cations are arranged in a parallel fashion (

Figure S1), with a separation of 3.431 Å between their least-squares quinoline planes and a relative orientation angle of 0°. The interring distance and the degree of molecular overlap indicate substantial π–π interactions, further reinforced by face-on contacts involving the aromatic chlorine atom. The “

Aromatics Analyser” tool in CSD-Materials [

14] classify these aromatic interactions as strong π–π contacts, with a score of 7 (see ESI).

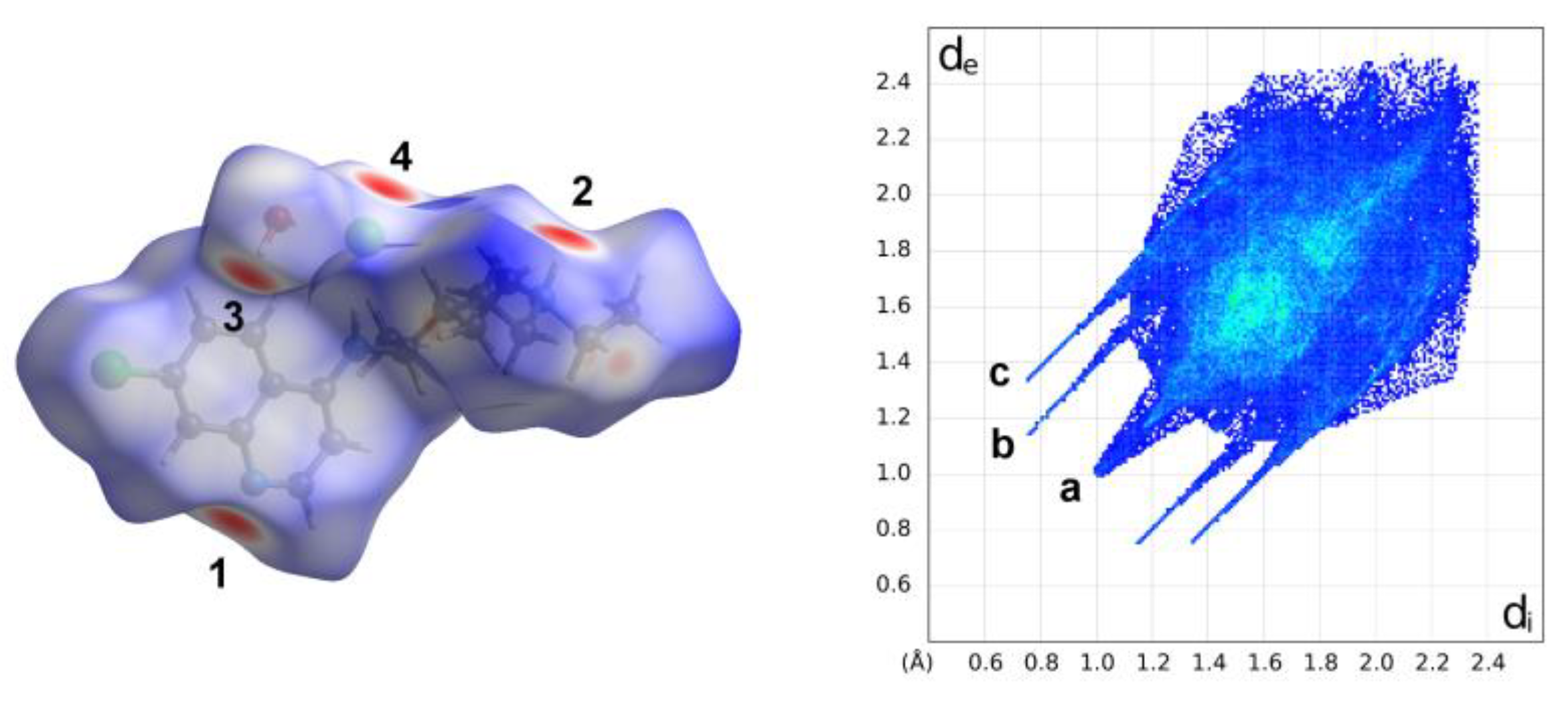

The analysis of the Hirshfeld Surface (HS) and 2D fingerprints (FP) performed using

CrystalExplorer [

15] to study and evaluate intermolecular interactions within the crystal packing of the compound under examination (

Figure 5,

Figures S2 and S3) confirmed the above description. The greatest contribution to the HS comes from the H· · ·H contacts (57.8%), due to the large hydrogen content of the molecule, including the presence of very close contacts between the terminal methyl H atoms at a shortest distance of ca. 2.0 Å (the pointed feature

a on the diagonal in

Figure 5). The FP displays two distinct pairs of sharp spikes corresponding to the hydrogen bonds contacts. The outer and shorter spikes ending at (d

e, d

i)

≅ (1.3, 0.7) Å (and vice versa) correspond to the N–H· · ·Cl hydrogen bonds while the inner longer ones correspond to the O

water—H· · ·N

pyridinic hydrogen bond with their tips at d

e + d

i ∼1.8 Å.

A careful inspection of the decomposed fingerprint plots, depicted in

Figure S3, pointed out that there weak π· · ·π interactions within the crystals, equivalent to C· · ·C contacts, that represent only 2.5% of surface area and appear as an arrow-shaped distribution at 1.8 Å < (d

i + d

e) < 2.1 Å. Furthermore, the role of the oxygen atom of water as an acceptor in a weak intermolecular hydrogen bond C—H· · ·O, with a pendant methyl group, is highlighted by the hidden pair of large peaks with d

e + d

i peaks at

≅ 2.6 Å.

A detailed discussion and rationalization of the close molecular contacts in the crystal structure, based on the electrostatic potential, is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Comparison of these results with the Hirshfeld surface analyses conducted separately on CQ+, chloride anion and water molecule, reveals that hydrogen bonding dominates both the interactions between the component and the supramolecular assembly together with other short contacts, involving all components.

3. Discussion

For the first time, a chloroquine salt, CQCl·H2O, containing exclusively monoprotonated chloroquine has been obtained via heterogeneous crystallization and fully characterized crystallographically. X-ray diffraction reveals protonation of CQ at the tertiary aliphatic nitrogen, along with an extensive hydrogen-bond network involving all components of the crystal. Crystallization was achieved by mixing equimolar solutions of neutral CQ in dichloromethane and iron (II) dichloride in methanol. During this process, the chloroquine molecule underwent protonation through proton transfer from the solvent environment, which, in the presence of an appropriate counterion, can favours stabilization of the salt rather than the neutral molecular species.

Spontaneous protonation of the tertiary amine of CQ in methanol in the presence of metal halides has previously been observed in the synthesis of the zwitterionic complexes [M(CQH

+)Cl

3] (M = Zn, Cd), in which the metal cation coordinates to the aromatic N-atom of a chloroquinium ligand [

16,

17,

18]. The isolation of chloroquine as a simple salt, rather than as a metal complex, is likely governed by the intrinsic reactivity of CQ toward the metal used and by the relative solubilities of the species present in solution. Analogous behaviour has also been observed for piperaquine (PIP), for which both a complex containing a monoprotonated PIP ligand as ligand and a halide salt of protonated PIP molecules have been isolated in the presence of metal salts and methanol [

19].

Beyond direct protonation, the presence of salts can influence the crystallization environment throughout the entire process, generating alternative solid forms [

19]. This phenomenon can be rationalized in terms of changes in ionic strength, which modulate compound solubility. A notable example is the selective production of a new dihydrate form of the dihydrochloride salt of amodiaquine (AQ), another well-known antimalaria, from a mixture containing magnesium chloride and the previously known form of the AQ salt [

20].

Overall, this work highlights the importance of evaluating the effects of excipients on the resulting solid forms and demonstrates that heterogeneous crystallization can serve both as a powerful strategy for the discovery of new crystalline phases as an effective alternative for systems that are otherwise difficult to crystallize [

21]. Comparable approaches have been successfully employed in both pharmaceutical and agrochemical research [

22,

23].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The Sigma-Aldrich products Chloroquine Diphosphate salt, CQDP, CAS number 50-63-5 (C18H26ClN3·2H3PO4, 98.5-101.0% EP), Iron (II) Chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2∙4H2O, ≥ 99.0%) and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH, ACS reagent, ≥97.0%, pellets) was purchased from Merk Life Science S.r.l., Milano, Italy. All the solvents (dichloromethane, methanol, n-hexane) were purchased from commercial suppliers (Merck) and were ACS or HPLC grade with mass purities higher than 99%. The materials were used as received, without any further purification.

4.2. Synthesis

4.2.1. Free Base CQ

A well-defined procedure was established to obtain highly crystalline chloroquine (CQ) powder from its salt form. Commercially available chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP, 4.5 to 5 g) was dissolved in 100 mL of water in a 250 mL beaker under stirring. A 1 M sodium hydroxide solution (60 mL) was then added very slowly over approximately one hour with continuous stirring until CQ precipitated as a gel-like substance at the bottom of the beaker. The alkaline supernatant (pH ~9) was removed. The gel was converted into a powder by adding approximately 100 mL of hexane under vigorous manual and magnetic stirring. The suspension was subsequently stirred for at least 3 hours. The resulting white solid was recovered by vacuum filtration or by allowing the solvent to evaporate to dryness and then dried in an oven at 40 °C for 12 hours. The process yielded the product with an average yield of 80%. To confirm the purity and crystalline nature of the material, all samples were ground and characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (

Figure S6).

4.2.2. Salt Crystallization

Single crystals of CQCl·H2O were obtained by heterogeneous diffusion crystallization. A methanolic solution of FeCl2∙4H2O (8.0 mg, 0.042 mmol in 2.5 mL MeOH) was carefully layered over a dichloromethane solution (2.5 mL) of CQ (23.9 mg, 0.0747 mmol in 2.5 mL CH2Cl2) in a glass vial. A small amount of brown precipitate formed immediately. The vial was stoppered and the solutions were allowed to diffuse slowly. After several days, the vial was opened and the mixture was allowed to evaporate at ambient temperature. Slow solvent evaporation to approximately one-third of the initial volume afforded pale-yellow single crystals suitable for analysis. Partial oxidation of Fe(II) during the crystallization process resulted in the formation of a brown precipitate.

4.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

The single-crystal X-ray data collection for

CQCl·H2O was performed at ambient temperature on an air-stable single crystal mounted on a glass fibre at a random orientation on a Bruker SMART three–circle diffractometer [

24] equipped with an Apex II CCD detector. Graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at a nominal power of 50 kV x 30 mA was used in conjunction with an ω–scan collection strategy (width of 0.5° frame

−1, exposure time of 50 sec. per frame) within the limits 1.5°< θ < 20.8°. Cell parameters were retrieved and refined using SAINT software v8.34A [

25] on 1393 reflections (16% of the collected reflections). SAINT and SADABS [

25] programs were employed, respectively, to perform data processing and an empirical absorption correction applying a multi-scan method. The structures were solved by direct methods (SIR2019) and refined within the spherical atom approximation refined by full-matrix least squares on

F2 (SHELX 2018) [

26] with the WINGX (2023.1) interface [

27]. The structure pictures were generated using the ORTEPIII (v1.0.3)[

27] and VESTA (v3.5.8) programs [

28].

The amino and water H-atoms were located in the difference Fourier map and refined with fixed individual displacement parameters, using a riding model with Uiso(H) = 1.2 Ueq (O) and Uiso(H) = 1.5 Ueq (N). All the other hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions (HFIX 43 for aromatic rings, HFIX 13 for methine group, HFIX 23 for methylene groups, HFIX 33 for methyl groups) and were included in the refinement in the riding model approximation, with Uiso values set to 1.5 Ueq (parent atom) for CH3 and 1.2 Ueq (parent atom) for CH and CH2 groups. All non-H atoms were refined with full occupancies and anisotropic displacement parameters except for those corresponding to disordered entities. The two pendant ethyl groups of the protonated tertiary amine moiety exhibit positional disorder over two sites, with refined occupancy ratios of 54 ∶ 46% and 72 ∶ 28% respectively. All disordered N—CH2— and CH3—CH2— distances were restrained to be equal within errors using the SADI instruction.

Crystal data and refinement details for CQCl·H2O: C18H29Cl2N3O, Mr = 374.34, T = 296(2) K, λ = 0.71073 Å, Monoclinic, space group P21/c, a = 14.577(4), b = 8.523(2), c = 17.593(5) Å, β = 112.863(3)°, V = 2014.0(9) Å3, Z = 4, ρcalc = 1.235 g·cm−3, µcalc = 0.332 mm−1, F(000) = 800, θ range = 1.5-20.8°, 8476 reflections collected, 2107 reflections unique, Rint = 0.1394, observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)] 1105, 1 restraints, 227 parameters, R1 (all data) = 0.1523, wR2 (all data) = 0.1504, R1 (observed) = 0.0767, wR2 (observed) = 0.1303, ∆ρmax = 0.224 eÅ−3, and ∆ρmin = −0.223 eÅ−3.

4.4. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

Ambient X-ray Powder Diffraction measurements were performed using a Miniflex-600 diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) with Cu Kα (

λ = 1.540598 Å) radiation, at a formal power of 50 kV x 40 mA, over an angular range of 3°– 40° (2

θ), with an incremental step size of 0.02° (2

θ) and a counting time of 1.5 s∙step

−1. Phase identification was performed by comparing the experimental powder pattern with that simulated from single-crystal data (CDMQUI from the Cambridge Structural Database) [

13]. The analysis of PXRD data was carried out by using

FullProf suite software [

29].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: π-π interactions in quinoline dimer; Table S1: Aromatic analyser score in CQCl·H2O (distances and angles of π···π and C–H···π stacking with X as the centre of the aromatics); Table S2: Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for CQCl·H2O; Empirical evaluation of the Hydrogen Bond strength; Figure S2: Relative contributions of various intermolecular interactions to the Hirshfeld surface area in CQCl·H2O; Figure S3: The decomposed fingerprint plots (atom–atom interactions) of the Hirshfeld surface for CQCl·H2O; Molecular Electrostatic Potential Analysis; Figure S4: Plots of total electron density isosurfaces mapped with electrostatic potential values; Figure S5. Packing diagram of CQCl·H2O structure down the [010] direction; Figure S6: The comparison between the experimental data for deprotonated CQ powder and the simulated PXRD pattern from the single-crystal X-ray data of neutral chloroquine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis, S.R.; investigation, S.R. and M.M.; resources, S.R.; data curation, S.R. and M.M.; writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, S.R. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

Università degli Studi di Milano is acknowledged for funding this work through the Research Support Plan 2025 (Piano di Sostegno alla Ricerca 2025), grant number PSR2025_DIP_005_SRIZZ.

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2518893 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via

www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures (accessed on 26th December 2025).

Acknowledgments

Università degli Studi di Milano is acknowledged for funding this research through the program PSR2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CQ |

Chloroquine |

| CQCl·H2O |

Chloroquine hydrochloride monohydrate |

| CQDP |

Chloroquine diphosphate |

| AQ |

Amodiaquine |

| PIP |

Piperaquine |

| HCQ |

Hydroxychloroquine |

| PXRD |

X-ray Powder Diffraction |

| HS |

Hirshfeld Surface |

| FP |

2D Fingerprints Plot |

References

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zou, C.; Zhang, J. Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bari, M.A.A. Chloroquine Analogues in Drug Discovery: New Directions of Uses, Mechanisms of Actions and Toxic Manifestations from Malaria to Multifarious Diseases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1608–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.A.; Rasheed, T.; Rizwan, K.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Rasool, N.; Toma, S.; Marceanu, L.G.; Bobescu, E. Risk. Management Strategies and Therapeutic Modalities to Tackle COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeeck, R.K.; Junginger, H.E.; Midha, K.K.; Shah, V.P.; Barends, D.M. Biowaiver Monographs for Immediate Release Solid Oral Dosage Forms Based on Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Literature Data: Chloroquine Phosphate, Chloroquine Sulfate, and Chloroquine hydrochloride. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, D.J. Pharmacology of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. In Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine Retinopathy; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; pp. 35–63. ISBN 978-1-4939-0597-3. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Santos, M.; De Morais Del Lama, M.P.F.; Siuiti Ito, A.; Zumstein Georgetto Naal, R.M. Binding of Chloroquine to Ionic Micelles: Effect of pH and Micellar Surface Charge. J. Lumin. 2014, 147, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeau, P. Special Issue Pharmaceutical Solid Forms: From Crystal Structure to Formulation. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iredale, J.; Fieger, H.; Wainer, I.W. Determination of the Stereoisomers of Hydroxychloroquine and Its Major Metabolites in Plasma and Urine Following a Single Oral Administration of Racemic Hydroxychloroquine. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 23, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Dutz, J.P. New Concepts in Antimalarial Use and Mode of Action in Dermatology. Dermatol. Ther. 2007, 20, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albesa-Jové, D.; Pan, Z.; Harris, K.D.M.; Uekusa, H. A Solid-State Dehydration Process Associated with a Significant Change in the Topology of Dihydrogen Phosphate Chains, Established from Powder X-Ray Diffraction. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 3641–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuseth, S.; Karlsen, J.; Mostad, A.; Romming, C.A.; Salmén, R.; Tønnesen, H.H.; Tokii, T. N4-(7-Chloro-4-Quinolinyl)-N1,N1-Diethyl-1,4-Pentanediamine. An X-Ray Diffraction Study of Chloroquine Diphosphate Hydrate. Acta Chem. Scand. 1990, 44, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macetti, G.; Loconte, L.; Rizzato, S.; Gatti, C.; Presti, L.L. Intermolecular Recognition of the Antimalarial Drug Chloroquine: A Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules-Density Functional Theory Investigation of the Hydrated Dihydrogen Phosphate Salt from the 103 K X-Ray Structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 6043–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courseille, C.; Busetta, B.; Hospital, M. 7-Chloro-4(4-Diethylamino-1-Methylbutyl-Amino) Quinoline. Cryst.Struct.Commun. 1973, 2, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From Visualization to Analysis, Design and Prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, P.R.; Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer: A Program for Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, Visualization and Quantitative Analysis of Molecular Crystals. J Appl Crystallogr 2021, 54, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soave, Raffaella. CCDC 2130150: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination.

- Paulikat, M.; Vitone, D.; Schackert, F.K.; Schuth, N.; Barbanente, A.; Piccini, G.; Ippoliti, E.; Rossetti, G.; Clark, A.H.; Nachtegaal, M.; et al. Molecular Dynamics and Structural Studies of Zinc Chloroquine Complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarcina, A.; Franke, A.; Senft, L.; Onderka, C.; Langer, J.; Vignane, T.; Filipovic, M.R.; Grill, P.; Michalke, B.; Ivanović-Burmazović, I. Zinc Complexes of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine versus the Mixtures of Their Components: Structures, Solution Equilibria/Speciation and Cellular Zinc Uptake. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 252, 112478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, S. Unpublished results (Manuscript in Preparation).

- Cotting, G.; Urquidi, O.; Besnard, C.; Brazard, J.; Adachi, T.B.M. The Effect of Salt Additives on the Glycine Crystallization Pathway Revealed by Studying One Crystal Nucleation at a Time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122, e2419638122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, O.D.; Pettersen, A.; Nilsson Lill, S.O.; Umeda, D.; Yonemochi, E.; Nugraha, Y.P.; Uekusa, H. Capturing a New Hydrate Polymorph of Amodiaquine Dihydrochloride Dihydrate via Heterogeneous Crystallisation. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, H.; Kawashima, Y.; Lin, S.Y. Polymorphism of Spray-Dried Microencapsulated Sulfamethoxazole with Cellulose Acetate Phthalate and Colloidal Silica, Montmorillonite, or Talc. J. Pharm. Sci. 1981, 70, 1256–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipduangta, P.; Takieddin, K.; Fábián, L.; Belton, P.; Qi, S. A New Low Melting-Point Polymorph of Fenofibrate Prepared via Talc Induced Heterogeneous Nucleation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5011–5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, D.; Grepioni, F.; Chelazzi, L.; Nanna, S.; Rubini, K.; Curzi, M.; Giaffreda, S.L.; Saxell, H.E.; Bratz, M.; Chiodo, T. Bentazon: Effect of Additives on the Crystallization of Pure and Mixed Polymorphic Forms of a Commercial Herbicide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 5729–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker APEX2 V2014.1-1. Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2015.

- Bruker SAINT v8.34A, XPREP V2013/3, SADABS. Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2013.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. FULLPROF: A Program for Rietveld Refinement and Pattern-Matching Analysis. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the meeting Powder Diffraction, Toulouse, France, 1990; pp. 127–128. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).