Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

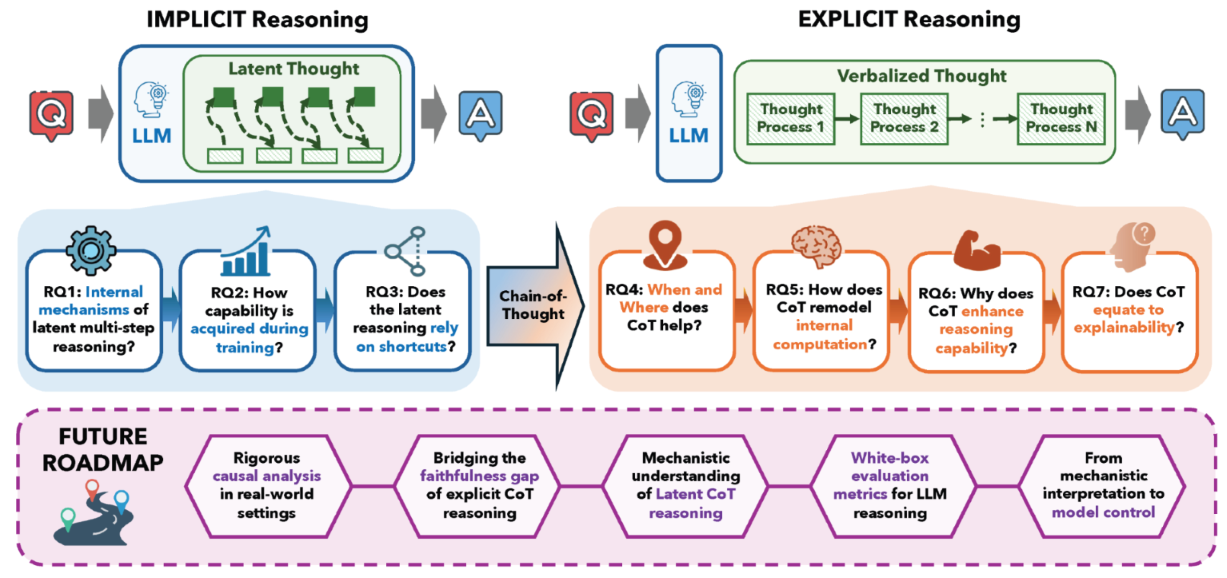

1. Introduction

2. Implicit Multi-Step Reasoning

2.1. What Are the Internal Mechanisms of Latent Multi-Step Reasoning?

- Functional specialization of layers.

- Uncovering fine-grained reasoning structures.

- Layer depth as the primary bottleneck for implicit reasoning.

- Why implicit reasoning sometimes fails.

2.2. How Latent Multi-Step Reasoning Capability Is Acquired During Training?

- Grokking marks the shift from memorization to reasoning.

- Factors influencing the emergence of reasoning.

2.3. To What Extent Does Multi-Step Reasoning Rely on Shortcuts?

- Factual shortcuts bypass intermediate reasoning.

- Shortcuts based on surface-level pattern matching.

3. Explicit Multi-Step Reasoning

3.1. Where and When Does CoT Help?

- On which tasks does CoT help?

- What factors influence the efficacy of CoT?

- Why do these factors influence CoT efficacy?

3.2. How Does Chain-of-Thought Remodel Internal Computation?

- The emergence of iteration heads.

- Evidence of state maintenance and update.

- Computational depth matters more than token semantics.

- Parallelism and reasoning shortcuts.

3.3. Why CoT Enhances Reasoning Abilities?

- CoT augments computational expressiveness.

- CoT introduces modularity that reduces sample complexity.

- CoT enables more robust reasoning.

3.4. Does Chain-of-Thought Equate to Explainability?

- Evidence of CoT unfaithfulness.

- Mechanistic understanding of CoT unfaithfulness.

4. Future Research Directions

- Rigorous causal analysis in real-world settings.

- Bridging the faithfulness gap of explicit CoT reasoning.

- Mechanistic understanding of Latent CoT reasoning.

- White-box evaluation metrics for LLM reasoning.

- From mechanistic interpretation to model control.

5. Conclusion

Limitations

References

- Hou, Yifan, Jiaoda Li, Yu Fei, Alessandro Stolfo, Wangchunshu Zhou, Guangtao Zeng, Antoine Bosselut, and Mrinmaya Sachan. 2023. Towards a mechanistic interpretation of multi-step reasoning capabilities of language models. Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 4902–4919. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jie, and Kevin Chen-Chuan Chang. 2023. Towards reasoning in large language models: A survey. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. pp. 1049–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Mingyu, Qinkai Yu, Dong Shu, Haiyan Zhao, Wenyue Hua, Yanda Meng, Yongfeng Zhang, and Mengnan Du. 2024. The impact of reasoning step length on large language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 1830–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Tianjie, Yijin Chen, Xinwei Yuan, Zhuosheng Zhang, Wei Du, Yubin Zheng, and Gongshen Liu. 2024. Investigating multi-hop factual shortcuts in knowledge editing of large language models. Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 8987–9001. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Cheongwoong, and Jaesik Choi. 2023. Impact of co-occurrence on factual knowledge of large language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 7721–7735. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Juno, and Taiji Suzuki. 2025. Transformers provably solve parity efficiently with chain of thought. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, Keito, Yoichi Aoki, Tatsuki Kuribayashi, Shusaku Sone, Masaya Taniguchi, Ana Brassard, Keisuke Sakaguchi, and Kentaro Inui. 2024. Think-to-talk or talk-to-think? when llms come up with an answer in multi-step reasoning. abs/2412.01113. [Google Scholar]

- Lanham, Tamera, Anna Chen, Ansh Radhakrishnan, Benoit Steiner, Carson Denison, Danny Hernandez, Dustin Li, Esin Durmus, Evan Hubinger, Jackson Kernion, Kamile Lukosiute, Karina Nguyen, Newton Cheng, Nicholas Joseph, Nicholas Schiefer, Oliver Rausch, Robin Larson, Sam McCandlish, Sandipan Kundu, Saurav Kadavath, Shannon Yang, Thomas Henighan, Timothy Maxwell, Timothy Telleen-Lawton, Tristan Hume, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Jared Kaplan, Jan Brauner, Samuel R. Bowman, and Ethan Perez. 2023. Measuring faithfulness in chain-of-thought reasoning. abs/2307.13702. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Lim, Samuel, Xingwei Tan, Zhixue Zhao, and Nikolaos Aletras. 2025. Analysing chain of thought dynamics: Active guidance or unfaithful post-hoc rationalisation? CoRR abs/2508.19827.

- Li, Hongkang, Songtao Lu, Pin-Yu Chen, Xiaodong Cui, and Meng Wang. 2025. Training nonlinear transformers for chain-of-thought inference: A theoretical generalization analysis. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jindong, Yali Fu, Li Fan, Jiahong Liu, Yao Shu, Chengwei Qin, Menglin Yang, Irwin King, and Rex Ying. 2025. Implicit reasoning in large language models: A comprehensive survey. abs/2509.02350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yingcong, Kartik Sreenivasan, Angeliki Giannou, Dimitris Papailiopoulos, and Samet Oymak. 2023. Dissecting chain-of-thought: Compositionality through in-context filtering and learning. Proceedings of the 2023 Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Ziyue, Chenrui Fan, and Tianyi Zhou. 2025. Where to find grokking in LLM pretraining? monitor memorization-to-generalization without test. CoRR abs/2506.21551. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhaoyi, Gangwei Jiang, Hong Xie, Linqi Song, Defu Lian, and Ying Wei. 2024. Understanding and patching compositional reasoning in llms. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 9668–9688. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhiyuan, Hong Liu, Denny Zhou, and Tengyu Ma. 2024. Chain of thought empowers transformers to solve inherently serial problems. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Tianhe, Jian Xie, Siyu Yuan, and Deqing Yang. 2025. Implicit reasoning in transformers is reasoning through shortcuts. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 9470–9487. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ryan, Jiayi Geng, Addison J. Wu, Ilia Sucholutsky, Tania Lombrozo, and Thomas L. Griffiths. 2024. Mind your step (by step): Chain-of-thought can reduce performance on tasks where thinking makes humans worse. abs/2410.21333. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, Aman, Katherine Hermann, and Amir Yazdanbakhsh. 2023. What makes chain-of-thought prompting effective? A counterfactual study. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 1448–1535. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Thomas, Matthew Rahtz, János Kramár, Vladimir Mikulik, and Shane Legg. 2023. The hydra effect: Emergent self-repair in language model computations. abs/2307.15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, William, and Ashish Sabharwal. 2023a. A logic for expressing log-precision transformers. Proceedings of the 2023 Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, William, and Ashish Sabharwal. 2023b. The parallelism tradeoff: Limitations of log-precision transformers. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 11, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, William, and Ashish Sabharwal. 2024. The expressive power of transformers with chain of thought. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, Chancharik, Brandon Huang, Trevor Darrell, and Roei Herzig. 2024. Compositional chain-of-thought prompting for large multimodal models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2024); IEEE, pp. 14420–14431. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, Neel, Josh Engels, Arthur Conmy, Senthooran Rajamanoharan, Bilal Chughtai, Callum McDougall, János Kramár, and Lewis Smith. 2025. A pragmatic vision for interpretability. In AI Alignment Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, Neel, Josh Engels, Senthooran Rajamanoharan, Arthur Conmy, Bilal Chughtai, Callum McDougall, János Kramár, and Lewis Smith. 2025. How can interpretability researchers help AGI go well? LessWrong. [Google Scholar]

- Nikankin, Yaniv, Anja Reusch, Aaron Mueller, and Yonatan Belinkov. 2025. Arithmetic without algorithms: Language models solve math with a bag of heuristics. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). [Google Scholar]

- nostalgebraist. 2020. interpreting GPT: the logit lens. August. Available online: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/AcKRB8wDpdaN6v6ru/interpreting-gpt-the-logit-lens.

- Olsson, Catherine, Nelson Elhage, Neel Nanda, Nicholas Joseph, Nova DasSarma, Tom Henighan, Ben Mann, Amanda Askell, Yuntao Bai, Anna Chen, Tom Conerly, Dawn Drain, Deep Ganguli, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Danny Hernandez, Scott Johnston, Andy Jones, Jackson Kernion, Liane Lovitt, Kamal Ndousse, Dario Amodei, Tom Brown, Jack Clark, Jared Kaplan, Sam McCandlish, and Chris Olah. 2022. In-context learning and induction heads. abs/2209.11895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. 2023. GPT-4 technical report. abs/2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, Jacob, William Merrill, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2024. Let’s think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models. CoRR abs/2404.15758.

- Power, Alethea, Yuri Burda, Harri Edwards, Igor Babuschkin, and Vedant Misra. 2022. Grokking: Generalization beyond overfitting on small algorithmic datasets. abs/2201.02177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, Akshara, Thomas L. Griffiths, and R. Thomas McCoy. 2024. Deciphering the factors influencing the efficacy of chain-of-thought: Probability, memorization, and noisy reasoning. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 3710–3724. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, Daking, and Ziyu Yao. 2024. An investigation of neuron activation as a unified lens to explain chain-of-thought eliciting arithmetic reasoning of llms. Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); pp. 7174–7193. [Google Scholar]

- Sadr, Nikta Gohari, Sangmitra Madhusudan, and Ali Emami. 2025. Think or step-by-step? unzipping the black box in zero-shot prompts. abs/2502.03418. [Google Scholar]

- Saunshi, Nikunj, Nishanth Dikkala, Zhiyuan Li, Sanjiv Kumar, and Sashank J. Reddi. 2025. Reasoning with latent thoughts: On the power of looped transformers. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, Prajit, and Islem Rekik. 2025. X-node: Self-explanation is all we need. In Reconstruction and Imaging Motion Estimation, and Graphs in Biomedical Image Analysis - First International Workshop, RIME 2025, and 7th International Workshop, GRAIL 2025. Springer: Volume 16150, pp. 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Mrinank, Meg Tong, Tomasz Korbak, David Duvenaud, Amanda Askell, Samuel R. Bowman, Esin Durmus, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Scott R. Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Timothy Maxwell, Sam McCandlish, Kamal Ndousse, Oliver Rausch, Nicholas Schiefer, Da Yan, Miranda Zhang, and Ethan Perez. 2024. Towards understanding sycophancy in language models. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Zhenyi, Hanqi Yan, Linhai Zhang, Zhanghao Hu, Yali Du, and Yulan He. 2025. CODI: compressing chain-of-thought into continuous space via self-distillation. CoRR abs/2502.21074.

- Sprague, Zayne Rea, Fangcong Yin, Juan Diego Rodriguez, Dongwei Jiang, Manya Wadhwa, Prasann Singhal, Xinyu Zhao, Xi Ye, Kyle Mahowald, and Greg Durrett. 2025. To cot or not to cot? chain-of-thought helps mainly on math and symbolic reasoning. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, Aarohi, Abhinav Rastogi, Abhishek Rao, Abu Awal Shoeb Md, Abubakar Abid, Adam Fisch, Adam R. Brown, Adam Santoro, Aditya Gupta, Adrià Garriga-Alonso, Agnieszka Kluska, Aitor Lewkowycz, Akshat Agarwal, Alethea Power, Alex Ray, Alex Warstadt, Alexander W. Kocurek, Ali Safaya, Ali Tazarv, Alice Xiang, Alicia Parrish, Allen Nie, Aman Hussain, Amanda Askell, Amanda Dsouza, Ambrose Slone, Ameet Rahane, Anantharaman S. Iyer, Anders Andreassen, Andrea Madotto, Andrea Santilli, Andreas Stuhlmüller, Andrew M. Dai, Andrew La, Andrew K. Lampinen, Andy Zou, Angela Jiang, Angelica Chen, Anh Vuong, Animesh Gupta, Anna Gottardi, Antonio Norelli, Anu Venkatesh, Arash Gholamidavoodi, Arfa Tabassum, Arul Menezes, Arun Kirubarajan, Asher Mullokandov, Ashish Sabharwal, Austin Herrick, Avia Efrat, Aykut Erdem, Ayla Karakas, B. Ryan Roberts, Bao Sheng Loe, Barret Zoph, Bartlomiej Bojanowski, Batuhan Özyurt, Behnam Hedayatnia, Behnam Neyshabur, Benjamin Inden, Benno Stein, Berk Ekmekci, Bill Yuchen Lin, Blake Howald, Bryan Orinion, Cameron Diao, Cameron Dour, Catherine Stinson, Cedrick Argueta, Cèsar Ferri Ramírez, Chandan Singh, Charles Rathkopf, Chenlin Meng, Chitta Baral, Chiyu Wu, Chris Callison-Burch, Chris Waites, Christian Voigt, Christopher D. Manning, Christopher Potts, Cindy Ramirez, Clara E. Rivera, Clemencia Siro, Colin Raffel, Courtney Ashcraft, Cristina Garbacea, Damien Sileo, Dan Garrette, Dan Hendrycks, Dan Kilman, Dan Roth, Daniel Freeman, Daniel Khashabi, Daniel Levy, Daniel Moseguí González, Danielle Perszyk, Danny Hernandez, Danqi Chen, Daphne Ippolito, and Dar Gilboa. [PubMed]

- Stechly, Kaya, Karthik Valmeekam, and Subbarao Kambhampati. 2024. Chain of thoughtlessness? an analysis of cot in planning. Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Suzgun, Mirac, Nathan Scales, Nathanael Schärli, Sebastian Gehrmann, Yi Tay, Hyung Won Chung, Aakanksha Chowdhery, Quoc V. Le, Ed H. Chi, Denny Zhou, and Jason Wei. 2023. Challenging big-bench tasks and whether chain-of-thought can solve them. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, 13003–13051. [Google Scholar]

- Tanneru, Sree Harsha, Dan Ley, Chirag Agarwal, and Himabindu Lakkaraju. 2024. On the hardness of faithful chain-of-thought reasoning in large language models. abs/2406.10625. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, Hugo, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yasmine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov, Soumya Batra, Prajjwal Bhargava, Shruti Bhosale, Dan Bikel, Lukas Blecher, Cristian Canton-Ferrer, Moya Chen, Guillem Cucurull, David Esiobu, Jude Fernandes, Jeremy Fu, Wenyin Fu, Brian Fuller, Cynthia Gao, Vedanuj Goswami, Naman Goyal, Anthony Hartshorn, Saghar Hosseini, Rui Hou, Hakan Inan, Marcin Kardas, Viktor Kerkez, Madian Khabsa, Isabel Kloumann, Artem Korenev, Punit Singh Koura, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Thibaut Lavril, Jenya Lee, Diana Liskovich, Yinghai Lu, Yuning Mao, Xavier Martinet, Todor Mihaylov, Pushkar Mishra, Igor Molybog, Yixin Nie, Andrew Poulton, Jeremy Reizenstein, Rashi Rungta, Kalyan Saladi, Alan Schelten, Ruan Silva, Eric Michael Smith, Ranjan Subramanian, Xiaoqing Ellen Tan, Binh Tang, Ross Taylor, Adina Williams, Jian Xiang Kuan, Puxin Xu, Zheng Yan, Iliyan Zarov, Yuchen Zhang, Angela Fan, Melanie Kambadur, Sharan Narang, Aurélien Rodriguez, Robert Stojnic, Sergey Edunov, and Thomas Scialom. 2023. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, Miles, Julian Michael, Ethan Perez, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2023. Language models don’t always say what they think: Unfaithful explanations in chain-of-thought prompting. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Tutunov, Rasul, Antoine Grosnit, Juliusz Ziomek, Jun Wang, and Haitham Bou-Ammar. 2023. Why can large language models generate correct chain-of-thoughts? abs/2310.13571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteri, Scott, Armand Lamparth, Pierre Chatain, and Clark Barrett. 2024. Markovian agents for informative language modeling. CoRR abs/2404.18988.

- Wang, Boshi, Sewon Min, Xiang Deng, Jiaming Shen, You Wu, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Huan Sun. 2023. Towards understanding chain-of-thought prompting: An empirical study of what matters. Proceedings of the 61nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); pp. 2717–2739. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Boshi, Xiang Yue, Yu Su, and Huan Sun. 2024. Grokked transformers are implicit reasoners: A mechanistic journey to the edge of generalization. Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiangqi, Yue Huang, Yujun Zhou, Xiaonan Luo, Kehan Guo, and Xiangliang Zhang. 2025. Causally-enhanced reinforcement policy optimization. CoRR abs/2509.23095.

- Wang, Yiming, Pei Zhang, Baosong Yang, Derek F. Wong, and Rui Wang. 2025. Latent space chain-of-embedding enables output-free LLM self-evaluation. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zijian, Yanxiang Ma, and Chang Xu. 2025. Eliciting chain-of-thought in base llms via gradient-based representation optimization. [Google Scholar]

- Wehner, Jan, Sahar Abdelnabi, Daniel Tan, David Krueger, and Mario Fritz. 2025. Taxonomy, opportunities, and challenges of representation engineering for large language models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research (TMLR). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Jason, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, Maarten Bosma, Denny Zhou, Donald Metzler, Ed H. Chi, Tatsunori Hashimoto, Oriol Vinyals, Percy Liang, Jeff Dean, and William Fedus. 2022. Emergent abilities of large language models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research (TMLR). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Jason, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Brian Ichter, Fei Xia, Ed H. Chi, Quoc V. Le, and Denny Zhou. 2022. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Kaiyue, Huaqing Zhang, Hongzhou Lin, and Jingzhao Zhang. 2025. From sparse dependence to sparse attention: Unveiling how chain-of-thought enhances transformer sample efficiency. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Skyler, Eric Meng Shen, Charumathi Badrinath, Jiaqi Ma, and Himabindu Lakkaraju. 2023. Analyzing chain-of-thought prompting in large language models via gradient-based feature attributions. abs/2307.13339. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, An, Baosong Yang, Beichen Zhang, Binyuan Hui, Bo Zheng, Bowen Yu, Chengyuan Li, Dayiheng Liu, Fei Huang, Haoran Wei, Huan Lin, Jian Yang, Jianhong Tu, Jianwei Zhang, Jianxin Yang, Jiaxi Yang, Jingren Zhou, Junyang Lin, Kai Dang, Keming Lu, Keqin Bao, Kexin Yang, Le Yu, Mei Li, Mingfeng Xue, Pei Zhang, Qin Zhu, Rui Men, Runji Lin, Tianhao Li, Tingyu Xia, Xingzhang Ren, Xuancheng Ren, Yang Fan, Yang Su, Yichang Zhang, Yu Wan, Yuqiong Liu, Zeyu Cui, Zhenru Zhang, and Zihan Qiu. 2024. Qwen2.5 technical report. CoRR abs/2412.15115.

- Yang, Chenxiao, Zhiyuan Li, and David Wipf. 2025. Chain-of-thought provably enables learning the (otherwise) unlearnable. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). OpenReview.net. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Sohee, Elena Gribovskaya, Nora Kassner, Mor Geva, and Sebastian Riedel. 2024. Do large language models latently perform multi-hop reasoning? Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 10210–10229. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Sohee, Nora Kassner, Elena Gribovskaya, Sebastian Riedel, and Mor Geva. 2025a. Do large language models perform latent multi-hop reasoning without exploiting shortcuts? Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025, 3971–3992. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Sohee, Nora Kassner, Elena Gribovskaya, Sebastian Riedel, and Mor Geva. 2025b. Do large language models perform latent multi-hop reasoning without exploiting shortcuts? In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025. Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 3971–3992. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zhipeng, Junzhuo Li, Siyu Xia, and Xuming Hu. 2025. Internal chain-of-thought: Empirical evidence for layer-wise subtask scheduling in llms. CoRR abs/2505.14530.

- Yao, Xinhao, Ruifeng Ren, Yun Liao, and Yong Liu. 2025. Unveiling the mechanisms of explicit cot training: How chain-of-thought enhances reasoning generalization. abs/2502.04667. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Yuekun, Yupei Du, Dawei Zhu, Michael Hahn, and Alexander Koller. 2025. Language models can learn implicit multi-hop reasoning, but only if they have lots of training data. CoRR abs/2505.17923.

- Ye, Jiaran, Zijun Yao, Zhidian Huang, Liangming Pan, Jinxin Liu, Yushi Bai, Amy Xin, Liu Weichuan, Xiaoyin Che, Lei Hou, and Juanzi Li. 2025. How does transformer learn implicit reasoning? Proceedings of the 2025 Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2025), San Diego, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Xi, and Greg Durrett. 2022. The unreliability of explanations in few-shot prompting for textual reasoning. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Yijiong. 2025. Do llms really think step-by-step in implicit reasoning? CoRR abs/2411.15862.

- Yu, Zeping, Yonatan Belinkov, and Sophia Ananiadou. 2025. Back attention: Understanding and enhancing multi-hop reasoning in large language models. abs/2502.10835. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jason, and Scott Viteri. 2024. Uncovering latent chain of thought vectors in language models. abs/2409.14026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yifan, Wenyu Du, Dongming Jin, Jie Fu, and Zhi Jin. 2025. Finite state automata inside transformers with chain-of-thought: A mechanistic study on state tracking. Proceedings of the 63nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 13603–13621. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuyi, Boyu Tang, Tianjie Ju, Sufeng Duan, and Gongshen Liu. 2025. Do latent tokens think? a causal and adversarial analysis of chain-of-continuous-thought. abs/2512.21711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zhongwang, Pengxiao Lin, Zhiwei Wang, Yaoyu Zhang, and Zhi-Qin John Xu. 2025. Complexity control facilitates reasoning-based compositional generalization in transformers. abs/2501.08537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.