1. Introduction

Forage-based diets underpin ruminant production systems by supplying most nutrients required for animal maintenance, growth, and production. In most ruminant systems, forages contribute between 40 and 90% of total feed intake, highlighting their central role in livestock productivity and sustainability [

1,

2]. In semi-arid and seasonally variable regions, such as Southern Africa, the preservation of surplus forage during the rainy season is critical to mitigate feed shortages during dry periods and recurrent droughts [

3].

Among forage conservation strategies, ensiling has gained prominence over haymaking due to its ability to preserve large quantities of forage rapidly, with reduced reliance on favourable weather conditions and improved palatability resulting from earlier harvest stages [

4]. Silage preservation is driven by anaerobic fermentation, during which lactic acid bacteria (LAB) convert water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) into organic acids, primarily lactic acid, resulting in a rapid decline in pH that stabilises the ensiled biomass [

5]. However, the success of this process depends on crop characteristics, microbial dynamics, and management interventions.

Maize (

Zea mays L.) is the dominant silage crop in Southern Africa, with South Africa being the principal producer in the region [

6]. Its high WSC concentration and favourable fermentability make maize particularly suitable for ensiling and widely adopted in intensive and semi-intensive livestock systems [

7]. Nevertheless, maize silage presents inherent limitations. High lactic acid concentrations and residual sugars, although indicative of efficient primary fermentation, have been strongly associated with poor aerobic stability during feed-out due to rapid proliferation of yeasts and moulds [

8]. This challenge is exacerbated under warm climatic conditions, where spoilage microorganisms thrive at temperatures between 20 and 30 °C [

9].

In addition to stability concerns, maize silage is intrinsically low in crude protein (CP), typically containing less than 100 g CP/kg DM [

10]. This necessitates supplementation with external protein sources to meet ruminant nutritional requirements, particularly in production systems where protein-rich forages are scarce. While soybean meal (SBM) is widely used for this purpose, its increasing cost and reliance on imports have driven interest in alternative plant-based protein supplements. The use of urea has also been explored; however, its narrow safety margin and risk of toxicity limit its practical application.

Microbial inoculants are commonly employed to improve silage fermentation efficiency and aerobic stability. Homofermentative LAB are primarily used to enhance lactic acid production and accelerate pH decline, thereby suppressing undesirable microorganisms [

11,

12]. In contrast, heterofermentative LAB convert lactic acid to acetic acid and other metabolites that inhibit yeasts and moulds, improving aerobic stability but sometimes at the expense of dry matter (DM) recovery [

13]. The relative merits of these inoculants remain debated, particularly when silage composition is altered through nutrient supplementation, as conflicting results have been reported regarding fermentation efficiency, nutrient preservation, and stability.

Agro-industrial by-products with moderate to high CP content have emerged as potential alternatives to conventional protein supplements. Marula oilcake (MOC), a by-product of marula oil extraction, contains 340–370 g CP/kg DM and is comparable to other commercial oilseed meals such as canola and sunflower oilcakes [

14,

15,

16]. Despite its nutritional potential, limited information exists on how MOC interacts with maize silage fermentation, particularly when combined with microbial inoculants. The effects of such supplementation on fermentation pathways, aerobic stability, and nutrient degradability remain poorly understood.

The present study therefore aimed to evaluate the effects of protein supplementation and microbial inoculation on the fermentation characteristics, aerobic stability, and in vitro nutrient degradability of maize silage. By integrating established fermentation theory with emerging alternative protein strategies, this work provides new insight into how silage additives and supplements interact to shape fermentation outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Agricultural Research Council–Animal Production (ARC-AP), Irene Campus (APIEC 26/08), and the Tshwane University of Technology Animal Ethics Committee (PO24/04).

2.2. Study Site and Experimental Design

Silage production was conducted at the ARC–Animal Production, Irene Campus, South Africa, while chemical analyses and in vitro digestibility assays were performed at the University of Pretoria, Nutrilab. The experiment followed a 2 × 3 factorial design to evaluate the effects of protein source (SBM or MOC) and microbial inoculation on maize silage fermentation, nutrient composition, and aerobic stability.

2.3. Silage Preparation and Treatments

Whole-crop maize (Zea mays L.: Senkuil, Sensako, Brits, South Africa) was grown at ARC-AP and harvested at <38% dry matter using a precision forage harvester (5 mm chop length). Chopped maize was supplemented with either SBM or MOC and treated with either a heterofermentative inoculant (Lactobacillus buchneri; Lalsil Fresh) or a homofermentative inoculant (Sil-All 4x4®), with untreated controls included. Inoculants were applied according to manufacturers’ recommendations. Treated materials were compacted into 1.5 L anaerobic jars and ensiled for 90 days, with triplicate jars also opened at 7, 14 and 21 days for pH determination.

2.4. Chemical Composition and Fermentation Analysis

Samples collected before and after ensiling were analysed for dry matter, crude protein, ether extract, gross energy, organic matter, and fibre fractions (aNDF, ADF, ADL) using AOAC procedures [

17,

18,

19]. Fermentation characteristics were assessed by measuring pH, WSC [

20], lactic acid (LA) [

21]as modified by [

22], ammonia-nitrogen (NH

3-N) [

17,

23], microbial populations, and volatile fatty acids (VFA) using gas chromatography [

24].

2.5. Aerobic Stability

Aerobic stability was evaluated by exposing silage samples to air at 28 °C for five days. Temperature rise, pH changes, and carbon dioxide (CO

2) production were monitored, and aerobic stability was defined as the time required for silage temperature to increase by ≥2 °C above ambient [

25].

2.6. In Vitro Digestibility and Gas Production

In vitro organic matter digestibility (IVOMD) was determined using the two-stage technique of [

26] with rumen fluid collected from cannulated sheep. Incubations were conducted at 39 °C for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. Gas production was measured using calibrated glass syringes and expressed as cumulative gas volume following [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of MOC and SBM is presented in

Table 3.1. Marula oilcake contained significantly higher DM, ether extract (EE), gross energy (GE), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) compared with SBM (P<0.05), indicating a more energy-dense but fibrous supplement. In contrast, SBM exhibited significantly greater CP and ash contents and a higher IVOMD (P<0.05), reflecting its superior protein quality and digestibility. Acid detergent fibre (ADF) and neutral detergent fibre (NDF) concentrations did not differ between protein sources (P>0.05).

Table 3.1.

Chemical composition (% unless otherwise stated) of protein sources (SBM) and (MOC)] (n=3).

Table 3.1.

Chemical composition (% unless otherwise stated) of protein sources (SBM) and (MOC)] (n=3).

| Parameters |

Protein sources |

SEM |

P-value |

| SBM |

MOC |

Treatment |

Linear |

| DM |

92.32b

|

95.69a

|

0.106 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Ash |

6.14a

|

4.65b

|

0.067 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| CP |

51.18a

|

39.10b

|

0.294 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| EE |

1.98b

|

41.13a

|

0.829 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| GE |

19.02b

|

24.49a

|

0.041 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| aNDF |

7.00a

|

14.50a

|

6.940 |

0.340 |

0.340 |

| ADF |

4.90a

|

7.80a

|

2.870 |

0.368 |

0.368 |

| ADL |

5.45b

|

10.92a

|

0.513 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| IVOMD |

94.83a

|

81.97b

|

1.950 |

0.003 |

0.003 |

The chemical composition of pre-ensiled whole-crop maize treatment diets is shown in

Table 3.2. Diets supplemented with SBM contained higher (P<0.05) CP, WSC, and LA concentrations than MOC-based diets, suggesting greater availability of fermentable substrates prior to ensiling. Conversely, EE content and microbial counts, including lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as well as yeast and mould populations, were higher (P<0.05) in MOC-based treatments. The highest (P<0.05) EE content and LAB population were observed in the non-inoculated MOC treatment (treatment 4), indicating that residual oil in MOC may have influenced microbial proliferation prior to ensiling.

Table 3.2.

Chemical composition (% unless otherwise stated) of pre-ensiled chopped whole crop maize with bacterial inoculants (n = 3).

Table 3.2.

Chemical composition (% unless otherwise stated) of pre-ensiled chopped whole crop maize with bacterial inoculants (n = 3).

| Parameters |

Treatments |

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T5 |

T6 |

| DM |

36.11 |

31.68 |

35.53 |

35.72 |

37.98 |

31.34 |

| Ash |

5.06 |

6.93 |

5.03 |

4.90 |

4.19 |

4.51 |

| CP |

22.40 |

18.92 |

21.21 |

18.12 |

11.56 |

15.86 |

| EE |

3.29 |

3.83 |

3.05 |

36.33 |

12.70 |

10.58 |

| aNDF |

33.97 |

37.27 |

39.62 |

30.71 |

38.22 |

31.64 |

| ADF |

19.99 |

20.24 |

21.75 |

18.18 |

20.00 |

18.37 |

| ADL |

2.99 |

2.46 |

3.71 |

4.63 |

9.60 |

4.01 |

| WSC |

0.15 |

0.14 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

| pH |

5.57 |

5.70 |

5.77 |

5.73 |

5.73 |

4.90 |

| LAB log cfu/g |

6.20 |

7.52 |

6.42 |

8.31 |

8.22 |

7.91 |

| LA log cfu/g |

3.90 |

1.16 |

2.98 |

1.64 |

0.09 |

1.10 |

| Y & M log cfu/g |

2.32 |

3.69 |

6.14 |

6.02 |

5.12 |

4.90 |

3.2. Silage Fermentation, Nutrient Composition, and Aerobic Stability

Table 3.3 presents the fermentation characteristics, nutrient composition, and aerobic stability of whole crop maize silage. Results indicate that treatment 2 and 6 were significantly higher (P<0.05) in WSC content than other treatments. The LAB population was highest (P<0.05) in the control treatments (treatments 1 and 4) than the treated silages, while LA concentration was dominant (P<0.05) only in treatment 1 than other treatments. Inoculation reduced (P<0.05) yeast and mould population in treatments 2 and 3 that were comparable to the yeast and mould in positive control.

The DM content of treatments was improved (P< 0.05) by bacterial inoculation except for treatment 6. Treatment 3 CP content was increased (P<0.05) by bacterial inoculation. In contrast, OM, NDF and ADF contents in treatment 2 were enhanced (P<0.05) by bacterial inoculation, while the GE, NDF, ADF and ADL were highest (P<0.05) in treatment 4. Bacterial inoculation increased (P<0.05) IVOMD of treatment 3, which was similar to that of control. The inoculation decreased (P<0.05) (NH

3)-N in all treatments with the lowest concentration observed in treatment 3 and highest in positive control (

Table 3.3). While production of CO

2 during fermentation was similar (P>0.05) across treatments, pH was lowest in treatments 3, while LAB and yeast and mould were highest (P<0.05) in treatments 4 and 6 than other treatments.

Table 3.3.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on the fermentation characteristics, nutrient composition, and aerobic stability (%, unless otherwise stated) of chopped whole crop maize silage (n = 3).

Table 3.3.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on the fermentation characteristics, nutrient composition, and aerobic stability (%, unless otherwise stated) of chopped whole crop maize silage (n = 3).

| Parameters |

Treatments |

SEM |

P-value |

| T 1 |

T2 |

T 3 |

T 4 |

T5 |

T 6 |

Treatment |

Linear |

Quadratic |

| Fermentation characteristics |

|

| WSC |

0.42b

|

2.05a

|

0.07b

|

0.17b

|

0.90ab

|

2.28a

|

0.447 |

<0.001 |

0.043 |

0.006 |

| LAB log10 cfu/g |

7.02a

|

6.04b

|

6.03b

|

6.98a

|

5.91b

|

6.55ab

|

0.258 |

<0.001 |

0.260 |

0.041 |

| LA |

0.24a

|

0.19b

|

0.08d

|

0.11c

|

0.05e

|

0.03f

|

0.003 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Y & M log10 cfu/g |

3.10c

|

3.26c

|

3.13c

|

4.34b

|

5.17a

|

4.27b

|

0.113 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.074 |

| Nutrient composition |

|

| DM |

40.97ab

|

41.95ab

|

41.24ab

|

39.13b

|

45.55a

|

28.87c

|

1.897 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| CP |

26.94a

|

23.54b

|

26.94a

|

9.04e

|

11.55d

|

17.68c

|

0.439 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| GE |

20.12c

|

18.58d

|

21.12b

|

24.82a

|

21.85b

|

24.57a

|

0.284 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.425 |

| OM |

3.44b

|

10.56a

|

3.90b

|

4.61b

|

4.60b

|

4.85b

|

0.614 |

<0.001 |

0.005 |

0.035 |

| aNDF |

39.02b

|

59.15a

|

43.76b

|

63.95a

|

39.53b

|

43.13b

|

2.121 |

<0.001 |

0.102 |

<0.001 |

| ADF |

22.53c

|

39.34a

|

25.13bc

|

37.36a

|

2385c

|

27.29b

|

1.146 |

<0.001 |

0.084 |

<0.001 |

| ADL |

7.92c

|

17.70b

|

8.06c

|

24.77a

|

10.26c

|

16.62b

|

1.169 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| IVOMD |

83.75a

|

68.28b

|

79.02a

|

40.01d

|

56.02c

|

51.75c

|

1.172 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| (NH3)-N as % of TN |

45.15a

|

23.80b

|

6.26f

|

9.49e

|

13.61d

|

15.58c

|

0.528 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Aerobic stability |

|

| pH |

3.73d

|

4.10c

|

4.30ab

|

3.87d

|

4.47a

|

4.27bc

|

0.077 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.292 |

| CO2

|

3.56b

|

16.53ab

|

12.05ab

|

39.46a

|

1.81b

|

24.17ab

|

1.12 |

0.012 |

0.134 |

0.171 |

| LAB log10 cfu/g |

0.92bc

|

1.52ab

|

1.42ab

|

1.96a

|

0.58c

|

1.89a

|

0.232 |

<0.001 |

0.040 |

0.230 |

| Y & M log10 cfu/g |

0.53bc

|

1.14ab

|

1.03ab

|

1.55a

|

0.24c

|

1.35a

|

0.226 |

<0.001 |

0.106 |

0.080 |

3.3. In Vitro Nutrient Digestibility

Table 3.4 presents the in vitro nutrient digestibility of whole-crop maize silage. Dry matter digestibility differed (P<0.05) among treatments at 0 h of incubation, but no differences (P<0.05) were observed from 3 to 48 h. Gross energy digestibility was consistently highest (P<0.05) in treatments 4 and 6 across all incubation times. Organic matter digestibility did not differ (P>0.05) among treatments at 3 h or from 24 to 48 h; however, it was higher (P<0.05) in treatment 6 at 6 h and in treatment 2 at 12 h.

Neutral detergent fibre (NDF) digestibility was higher (P<0.05) in treatment 2 at 6 h compared with other treatments but did not differ (P>0.05) from 12 to 48 h of incubation. Acid detergent fibre (ADF) digestibility differed (P<0.05) among treatments from 0 to 6 h but was similar thereafter (P>0.05). Acid detergent lignin (ADL) digestibility did not differ (P>0.05) among treatments from 0 to 12 h; however, it increased in treatment 5 after 6 h and in treatment 6 after 24 h (P<0.05). At 48 h, ADL digestibility increased (P<0.05) in all treatments except treatment 5.

Table 3.4.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on nutrient digestibility (% unless otherwise stated) of chopped whole crop maize silage. (n = 10).

Table 3.4.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on nutrient digestibility (% unless otherwise stated) of chopped whole crop maize silage. (n = 10).

| Parameters |

Incubation time (h.) |

Treatments |

SEM |

P-value |

| T1 |

T2 |

T 3 |

T4 |

T5 |

T6 |

Treatment |

Linear |

Quadratic |

| DM |

0 |

90.79b

|

93.00a

|

91.17b

|

91.11b

|

91.84ab

|

88.75c

|

0.566 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| 3 |

97.92a

|

98.30a

|

98.65a

|

98.86a

|

98.51a

|

98.30a

|

0.700 |

0.525 |

0.364 |

0.092 |

| 6 |

97.58a

|

97.95a

|

97.16a

|

97.64a

|

98.08a

|

98.18a

|

0.675 |

0.310 |

0.182 |

0.260 |

| 12 |

93.83a

|

98.06a

|

97.45a

|

96.41a

|

95.99a

|

96.45a

|

1.887 |

0.079 |

0.469 |

0.051 |

| 24 |

96.52ab

|

97.80a

|

96.81ab

|

97.71a

|

96.19ab

|

95.77b

|

0.816 |

0.013 |

0.038 |

0.011 |

| 48 |

98.03a

|

98.29a

|

98.19a

|

97.31a

|

97.87a

|

96.81a

|

0.865 |

0.171 |

0.035 |

0.331 |

| CP |

0 |

15.42b

|

31.01a

|

2.33c

|

12.05bc

|

14.88b

|

32.05a

|

3.067 |

<0.001 |

0.031 |

<0.001 |

| |

3 |

18.80c

|

34.89b

|

6.07d

|

16.13c

|

32.48b

|

40.20a

|

1.078 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| |

6 |

23.33d

|

38.88b

|

19.94d

|

32.59c

|

35.99bc

|

47.01a

|

1.406 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| |

12 |

28.30d

|

48.07b

|

26.85d

|

35.90c

|

45.13b

|

57.43a

|

1.563 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| |

24 |

34.26e

|

51.28b

|

33.45e

|

41.73d

|

47.49c

|

58.77a

|

1.088 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| |

48 |

35.59e

|

54.52b

|

35.73e

|

43.48d

|

50.66c

|

60.38a

|

1.147 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| GE |

0 |

19.99c

|

18.41d

|

21.07bc

|

24.80a

|

21.85b

|

24.60a

|

0.361 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.747 |

| 3 |

18.03c

|

17.36c

|

18.46c

|

23.41a

|

20.73b

|

21.38b

|

0.323 |

<0.01 |

<0.001 |

0.007 |

| 6 |

18.34c

|

17.93c

|

18.43c

|

23.50a

|

20.84b

|

21.95b

|

0.281 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.032 |

| 12 |

19.83bcd

|

18.24d

|

18.87cd

|

22.62ab

|

21.73abc

|

24.46a

|

0.791 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.023 |

| 24 |

19.90b

|

17.71b

|

19.77b

|

22.81a

|

22.43a

|

23.84a

|

0.575 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.070 |

| 48 |

19.38c

|

18.77c

|

19.55c

|

25.41a

|

22.74b

|

24.08ab

|

0.346 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.122 |

| OM |

0 |

3.38b

|

10.55a

|

3.71b

|

4.61b

|

4.53b

|

4.79b

|

0.840 |

0.001 |

0.089 |

0.219 |

| 3 |

2.70b

|

7.43a

|

3.99b

|

4.16b

|

2.90b

|

5.13ab

|

0.652 |

0.003 |

0.758 |

0.408 |

| 6 |

5.21b

|

7.74a

|

1.33c

|

2.60c

|

4.42b

|

6.54b

|

0.840 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| 12 |

3.72b

|

7.59a

|

4.74b

|

4.21b

|

3.52b

|

3.73b

|

0.597 |

0.003 |

0.011 |

0.047 |

| 24 |

4.63ab

|

7.40a

|

3.33b

|

4.22ab

|

4.03ab

|

4.05ab

|

0.970 |

0.051 |

0.079 |

0.782 |

| 48 |

0.69b

|

9.39a

|

5.02ab

|

4.29ab

|

2.73b

|

3.62ab

|

1.614 |

0.020 |

0.549 |

0.038 |

| NDF |

0 |

39.09c

|

58.45b

|

43.12c

|

65.19a

|

39.95c

|

43.67c

|

2.112 |

<0.001 |

0.250 |

<0.001 |

| 3 |

45.77c

|

69.00a

|

46.16c

|

56.72b

|

42.52c

|

40.93c

|

2.750 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| 6 |

43.79c

|

74.91a

|

48.41b

|

49.17b

|

45.95bc

|

43.10c

|

2.055 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| 12 |

51.67a

|

57.30a

|

56.05a

|

61.99a

|

45.74a

|

51.78a

|

15.93 |

0.775 |

0.677 |

0.438 |

| 24 |

58.86a

|

70.98a

|

60.83a

|

43.86a

|

51.95a

|

55.38a

|

12.22 |

0.097 |

0.090 |

0.604 |

| 48 |

68.44a

|

67.22a

|

68.60a

|

61.36bc

|

56.89c

|

63.96ab

|

2.463 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.126 |

| ADF |

0 |

22.45c

|

38.80a

|

24.80c

|

34.20ab

|

24.26c

|

30.37bc

|

3.596 |

<0.001 |

0.727 |

0.048 |

| 3 |

26.52b

|

46.91a

|

26.20b

|

31.56b

|

25.73b

|

19.65b

|

5.480 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.010 |

| 6 |

24.58e

|

50.85a

|

27.30cd

|

30.02b

|

28.84bc

|

26.59d

|

0.783 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| 12 |

23.06a

|

39.63a

|

35.20a

|

37.16a

|

26.69a

|

34.32a

|

12.83 |

0.446 |

0.722 |

0. 257 |

| 24 |

35.56ab

|

49.66a

|

37.01ab

|

27.41b

|

32.05b

|

37.02ab

|

7.540 |

0.014 |

0.098 |

0.504 |

| 48 |

44.27a

|

47.73a

|

45.02a

|

32.33a

|

34.26a

|

44.25a

|

9.040 |

0.130 |

0.177 |

0.232 |

| ADL |

0 |

21.95cd

|

31.70bc

|

19.81d

|

42.20a

|

25.60cd

|

36.34ab

|

4.572 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.514 |

| 3 |

7.72b

|

7.77b

|

7.89b

|

21.99a

|

16.74ab

|

15.29ab

|

6.200 |

0.016 |

0.007 |

0.321 |

| 6 |

-0.950c

|

8.110b

|

-1.885c

|

10.880b

|

16.580a

|

11.920b

|

2.058 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.545 |

| 12 |

8.43bc

|

12.57abc

|

16.83abc

|

20.15ab

|

4.05c

|

24.06a

|

6.370 |

0.003 |

0.051 |

0.944 |

| 24 |

5.61c

|

9.09bc

|

7.54bc

|

17.82a

|

10.74b

|

18.38a

|

1.803 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.875 |

| 48 |

19.93a

|

18.26a

|

19.55a

|

24.98a

|

9.18b

|

25.86a

|

3.724 |

<0.001 |

0.622 |

0.186 |

3.4. Volatile Fatty Acids of Whole Crop Maize Silage

Table 3.5 presents the volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles of whole-crop maize silage. Acetic acid concentrations differed (P<0.05) among treatments, with the highest values observed in treatment 2 and the lowest in treatment 4. Butyric acid concentrations also varied significantly (P<0.05), being elevated in treatments 1 and 3 and markedly lower in treatments 4 and 6. Iso-butyric acid concentration was highest in treatment 2 and lowest in treatment 4 (P<0.05).

Propionic acid concentration differed among treatments (P<0.05), with treatment 2 showing the highest values, followed by treatments 1 and 3, while treatments 4 and 6 recorded the lowest concentrations. Valeric acid levels varied (P<0.05) significantly across treatments, with the greatest concentrations observed in treatments 2 and 3, and very low levels (<0.25%) in treatments 1, 4, and 6. Iso-valeric acid concentrations were also treatment-dependent (P<0.05), with the highest values in treatments 1 and 2 and the lowest in treatments 4 and 6.

Table 3.5.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on volatile fatty acids of whole crop maize silage expressed in percent (% unless otherwise stated) (n = 3).

Table 3.5.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on volatile fatty acids of whole crop maize silage expressed in percent (% unless otherwise stated) (n = 3).

| Parameters |

Treatments |

SEM |

P-value |

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T5 |

T6 |

Treatment |

Linear |

Quadratic |

| Acetic |

3.010b

|

3.877a

|

2.960bc

|

2.558d

|

2.612cd

|

3.300b

|

0.167 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

| Butyric |

3.715a

|

2.855b

|

3.567a

|

0.745c

|

2.790b

|

1.237c

|

0.233 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.097 |

| Iso-butyric |

0.443ab

|

0.518a

|

0.438ab

|

0.128c

|

0.353b

|

0.183c

|

0.041 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.979 |

| Propionic |

2.607b

|

3.125a

|

2.585b

|

1.125d

|

1.915c

|

1.343d

|

0.141 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.843 |

| Valeric |

0.242c

|

1.045a

|

0.978a

|

0.190c

|

0.745b

|

0.250c

|

0.061 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Iso-valeric |

1.135ab

|

1.292a

|

1.105b

|

0.262d

|

0.907c

|

0.348d

|

0.079 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.486 |

3.5. pH of Whole Crop Maize Silage

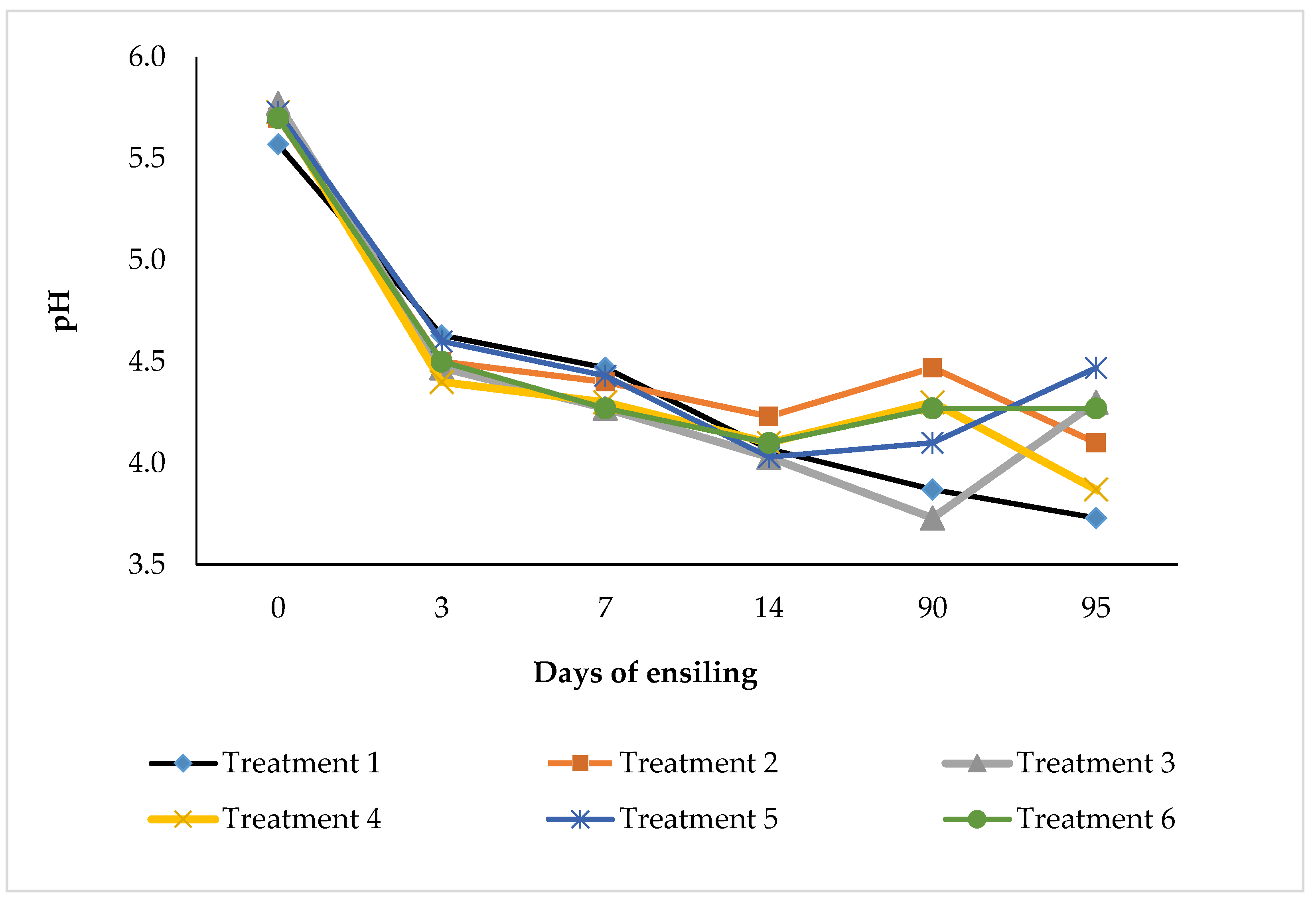

Figure 3.1 illustrates the pH changes of chopped whole-crop maize silage during ensiling and aerobic exposure. In treatment 1, pH decreased (P<0.05)with ensiling time. From 3 to 14 days of ensiling, pH did not differ (P>0.05) among treatments. After 90 days of ensiling, pH values in treatments 2 and 4 remained unchanged (P>0.05), whereas treatments 3 and 5 showed a further decline (P<0.05). During aerobic exposure, pH increased in treatments 3 and 5 but declined in the other treatments, with significant changes occurring only during the 5-day aerobic phase (P<0.05).

Figure 3.1.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on pH of chopped whole crop maize silage during 90 days of ensiling and after 5 days of aerobic exposure.

Figure 3.1.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on pH of chopped whole crop maize silage during 90 days of ensiling and after 5 days of aerobic exposure.

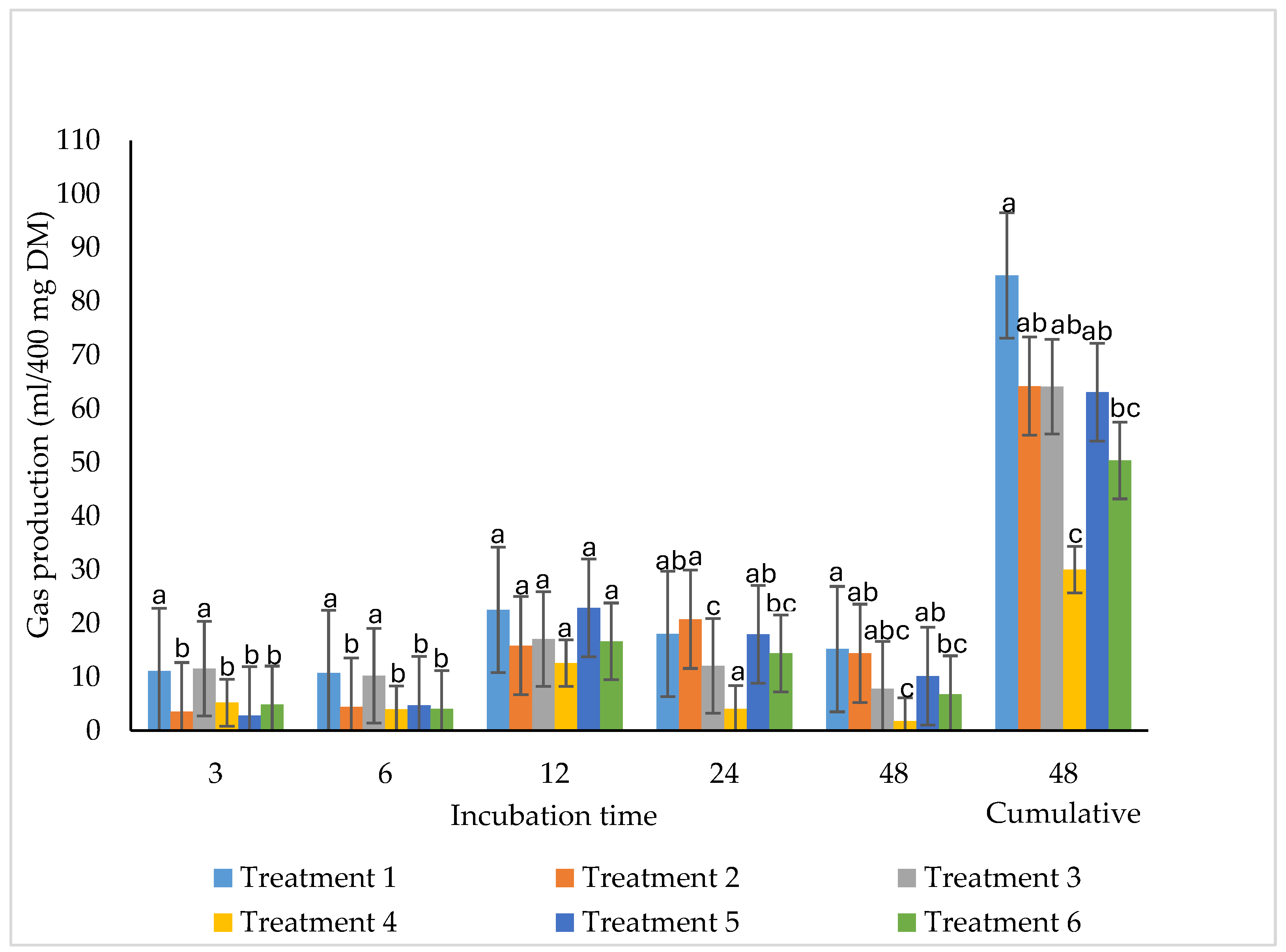

3.6. Whole Crop Maize Gas Production

Figure 3. 2 shows cumulative gas production from whole-crop maize silage during 48 h of incubation. Bacterial inoculation increased (P<0.05) gas production in treatment 3 between 3 and 6 h of incubation. At 12 h, gas production did not differ (P>0.05) among treatments. At 24 h, inoculation resulted in higher (P<0.05) gas production in treatment 2 compared to treatment 3. After 48 h, bacterial inoculation increased (P<0.05) gas production in all treatments except treatment 4. Cumulative gas production at 48 h was highest in treatment 1 and lowest in treatment 4 (P<0.05).

Figure 3.2.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on total gas production in chopped whole crop. maize silage incubated for 48 hours (n= 3).

Figure 3.2.

Effect of bacterial inoculant on total gas production in chopped whole crop. maize silage incubated for 48 hours (n= 3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Chemical Composition

The exploitation of alternative feed resources remains a viable strategy to mitigate feed shortages in South African livestock systems. Chemical composition is a primary determinant of the suitability of novel feedstuffs, as nutrient composition directs dietary inclusion rates and animal performance [

28,

29].

Compared with soybean meal (SBM), marula oilcake (MOC) contained higher dry DM, EE, GE, and ADL (

Table 3.1). The elevated EE and GE indicate that MOC has substantial potential as an energy source in livestock diets. Although CP concentration in MOC (391 g/kg DM) was lower than that of SBM, it was comparable to commonly used oilseed meals such as canola, cottonseed, and sunflower meals [

30,

31], supporting its classification as a viable protein supplement. Slightly higher CP and EE values for MOC have been reported elsewhere [

32], suggesting some variability related to processing or cultivar differences.

The high ADL concentration in MOC was associated with reduced

in vitro organic matter digestibility (IVOMD), consistent with lignin acting as an indigestible barrier to microbial degradation. Similar relationships between elevated ADL and reduced IVOMD have been reported in macadamia oilcake [

33]. Despite this limitation, IVOMD values for both SBM and MOC exceeded 50%, the minimum threshold considered suitable for ruminant feeds [

34], confirming their nutritional adequacy. The lack of significant differences in NDF and ADF suggests comparable rumen fill potential, although

in vivo validation remains necessary.

In fresh maize mixtures, SBM-based treatments exhibited higher CP, WSC, and LA, reflecting the higher protein and fermentable carbohydrate supply. In contrast, MOC-based treatments showed higher EE, microbial counts, and GE. The unexpectedly low fibre fractions in the MOC-based negative control may be explained by interference of residual oil with detergent fibre extraction, as previously described by [

19]. Elevated ADL and DM in some treatments may also reflect lignin–polyphenol complex formation in plant cell walls [

35].

4.2. Silage Fermentation, Nutrient Composition, and Aerobic Stability

Silage inoculants are widely applied to enhance fermentation consistency, accelerate pH decline, and improve nutrient retention [

36,

37]. However, their effectiveness depends on interactions among inoculated strains, epiphytic microbiota, and forage chemistry [

38]. In the present study, high WSC availability in several treatments supported fermentation even in non-inoculated silages, consistent with reports that fermentable substrate supply is a key driver of silage quality [

39].

Reduced LA concentrations in MOC-based treatments were likely caused by residual oil limiting microbial access to substrates or inhibiting LAB activity. Similar inhibitory effects of lipid coatings on microbial metabolism have been reported previously [

40,

41]. In treatment 3, lower LA production was likely linked to higher pre-ensiling fibre concentrations and elevated initial pH, which can delay fermentation. Enzymatic activity within the inoculant may also have been preferentially directed toward fibre hydrolysis rather than lactic acid production (

Table 3.3).

Although inoculation reduced pH over ensiling time, significant declines were only observed in treatments 1 and 3 after 90 days. Final pH values (3.73–4.47) were within ranges reported for acceptable maize silage [

42,

43] Higher pH in some treatments was associated with increased acetic acid production, reducing the lactic-to-acetic acid ratio, a pattern typical of heterofermentative pathways [

44].

Dry matter losses varied among treatments and appeared to be influenced more by substrate availability and microbial activity than by inoculant type alone. Lower DM in Sil-All–treated MOC silage may indicate secondary fermentation, potentially involving clostridial metabolism of sugars and lactic acid. While inoculation improved GE in some treatments, reductions in CP suggest ongoing proteolysis, particularly in oil-rich substrates where microbial efficiency may be constrained.

Measured fibre fractions generally fell within recommended ranges for maize silage [

45,

46], although ADL concentrations were unusually low in several treatments. This pattern suggests enzymatic degradation of lignin-associated structures, particularly in SBM-based silages, where the absence of residual oil may have enhanced enzyme accessibility (

Table 3.3).

4.3. In Vitro Nutrient Digestibility

In vitro techniques provide cost-effective estimates of feed digestibility and energy value [

47]. Microbial inoculation did not significantly affect DM digestibility, indicating that structural constraints rather than microbial efficiency governed DM utilization. Organic matter digestibility, however, was transiently improved in one inoculated SBM-based treatment (treatment 2), reflecting enhanced availability of fermentable substrates early in incubation (

Table 3. 4).

Improved GE digestibility in MOC-based treatments suggests that oil-rich substrates contributed rapidly digestible energy fractions. The observed digestibility kinetics, with early plateaus followed by slower fibre fermentation, are consistent with sequential utilization of soluble and structural carbohydrates [

48]. Crude protein digestibility was notably enhanced by Sil-All inoculation in MOC-based treatment (treatment 6), indicating that inoculants can partially offset lipid-related constraints on ruminal protein degradation [

49].

Enhanced fibre digestibility in SBM-based inoculated silage during early incubation likely resulted from rapid acidification and increased microbial colonization, improving access to hemicellulose and cellulose [

50,

51]. Improvements in ADL digestibility at extended incubation times suggest gradual disruption of lignin–carbohydrate complexes, facilitated by enzymatic activity [

52].

4.4. Volatile Fatty Acids

Volatile fatty acid profiles provided clear insights into fermentation quality. Elevated butyric acid and branched chain VFAs in treatments 1 and 3 indicate clostridial fermentation and extensive proteolysis, despite relatively high lactic acid concentrations [

53]. In contrast, Lalsil-treated SBM silage showed a shift toward acetic and propionic acid production, consistent with heterofermentative activity associated with improved aerobic stability [

54].

MOC-based treatments exhibited low concentrations of butyric acid and BCVFAs, suggesting reduced proteolysis and microbial stability. These findings support the hypothesis that oil-rich substrates may limit clostridial activity, even when total lactic acid production is comparatively low [

43,

55].

4.5. pH Dynamics During Ensiling and Aerobic Exposure

Silage pH is a primary indicator of fermentation efficiency and preservation quality, reflecting the extent of organic acid production and inhibition of undesirable microorganisms [

43,

56]. The progressive decline in pH observed during ensiling, particularly in the positive control (treatment 1), confirms active fermentation driven by adequate WSC and LA production. The similarity in pH across treatments during the early ensiling phase (3–14 days) suggests that initial fermentation was largely governed by substrate availability rather than inoculation, consistent with reports that epiphytic lactic acid bacteria can dominate fermentation when fermentable sugars are sufficient [

55].

The further pH reduction observed in treatment 3 after 90 days indicates that Sil-All inoculation enhanced acidification in SBM–supplemented silage, achieving pH values comparable to the uninoculated control. This supports previous findings that homofermentative inoculants can accelerate or sustain LA production under favourable substrate conditions [

38]. In contrast, the relatively stable pH in treatments 2 and 4 at 90 days suggests limited additional acid production, possibly due to a shift toward heterofermentative pathways or inhibition of LAB activity, particularly in MOC–based silages where residual oil may restrict microbial access to substrates.

During aerobic exposure, pH changes were more distinct, reflecting renewed microbial activity following oxygen ingress. The increase in pH in treatments 3 and 5 during this phase indicates LA utilisation by yeasts and other aerobic microorganisms, a process commonly associated with aerobic deterioration [

57]. Conversely, the decline in pH observed in other treatments (1, 2 and 4) suggests continued production or persistence of organic acids, contributing to short-term stability.

4.6. Total Gas Production

In vitro gas production reflects the extent and rate of microbial fermentation of silage substrates and is commonly used as an indirect indicator of fermentable carbohydrate availability and energy release [

27,

58]. The higher gas production observed in the positive control (treatment 1) throughout incubation, particularly at 48 h, suggests greater availability of fermentable substrates and higher overall degradability, consistent with its higher WSC content and LA concentration. Similar trends have been reported in maize silages supplemented with readily fermentable protein sources, where increased substrate availability enhances microbial activity and gas production [

59].

The early increase in gas production (3–6 h) in Sil-All–inoculated SBM-based silage (treatment 3) indicates accelerated initial fermentation, likely driven by improved accessibility of soluble carbohydrates and early microbial colonisation. However, the lack of sustained differences beyond 12 h suggests rapid depletion of readily fermentable fractions, after which fermentation kinetics became similar across treatments. This aligns with the concept that early gas production reflects soluble substrate fermentation, whereas later stages are dominated by fibre degradation [

60].

At 24 h, higher gas production in the Lalsil-inoculated SBM treatment (treatment 2) relative to treatment 3 indicates a shift towards heterofermentative activity, which may have enhanced secondary fermentation of structural carbohydrates. Heterofermentative

Lactobacillus buchneri has been reported to alter fermentation pathways and extend substrate utilisation over time, resulting in increased gas production at later incubation stages [

61].

The consistently lower gas production in the MOC-based negative control (treatment 4), particularly at 48 h, suggests reduced fermentability, likely due to higher lignin content and residual oil limiting microbial access to carbohydrates. High lipid concentrations are known to suppress rumen microbial activity and reduce gas production by coating feed particles and inhibiting fiber-degrading microbes [

41,

42]. Despite this, inoculation partially improved gas production in MOC-based treatments, indicating that microbial additives may mitigate, but not fully overcome, lipid-associated constraints.

5. Conclusions

Marula oilcake (MOC) demonstrated substantial potential as an alternative protein-energy supplement in maize silage, with nutrient composition and digestibility comparable to SBM despite higher lignin content. While residual oil in MOC moderated LA production and influenced fermentation dynamics, it also appeared to limit clostridial activity and protein degradation. Microbial inoculation improved specific aspects of fermentation and nutrient utilization, although responses varied with substrate composition and inoculant type. Overall, the findings support the feasibility of incorporating MOC into ruminant feeding systems, highlighting its value for diversifying feed resources in South African livestock production, while emphasizing the need for in vivo validation and optimization of inoculation strategies.

Moreover, further processing of MOC, particularly complete oil extraction, is recommended to reduce lipid-related inhibition of lactic acid fermentation and potentially improve silage fermentation efficiency and nutrient utilisation. Future studies should evaluate defatted MOC in combination with targeted microbial inoculants under in vivo conditions to optimize its inclusion in maize silage-based ruminant diets.

Author Contributions

M.: investigation and writing of the original draft, M.M., supervision and formal analysis, J.T., resources., T., data curation, B.D., supervision and validation, I.M.M., conceptualization, methodology and writing: review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa, grant number TTK190402426559.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Agricultural Research Council-Animal Production (APIEC 26/08 and 24/08) and Tshwane University of Technology (PO24/04 and 24/04). .

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restricted company policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cynthia Ngwane for her assistance with the statistical analysis of the study data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADF |

Acid detergent fiber. |

| ADL |

Acid detergent lignin. |

| aNDF |

Neutral detergent fiber (amylase-treated). |

| ARC-AP |

Agricultural Research Council–Animal Production. |

| BCVFA |

Branched-chain volatile fatty acids. |

| CFU |

Colony-forming units |

| CO₂ |

Carbon dioxide |

| CP |

Crude protein |

| DM |

Dry matter |

| EE |

Ether extract |

| GE |

Gross energy |

| GP |

Gas production |

| IVOMD |

In vitro organic matter digestibility |

| LAB |

Lactic acid bacteria |

| LA |

Lactic acid |

| MOC |

Marula oilcake |

| NH₃-N |

Ammonia nitrogen |

| OM |

Organic matter |

| SBM |

Soybean meal |

| SEM |

Standard error of the mean |

| TN |

Total nitrogen |

| VFA |

Volatile fatty acids |

| WSC |

Water-soluble carbohydrates |

| Y & M |

Yeast and mould |

References

- Charmley, E. Towards improved silage quality—A review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 81, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M.; Isselstein, J. Potentials of improving nitrogen utilisation from forages in ruminant nutrition. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 126, 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Vyver, W. F. J.; Beukes, J. A.; Meeske, R. Maize silage as a finisher feed for Merino lambs. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 43, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balehegn, M.; Ayantunde, A.; Amole, T.; Njarui, D.; Nkosi, B. D.; Müller, F. L.; Meeske, R.; Tjelele, T. J.; Malebana, I. M.; Madibela, O. R.; Boitumelo, W. S.; Adesogan, A. T. Forage conservation in sub-Saharan Africa: Review of experiences, challenges, and opportunities. Agronomy 2022, 114, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R. E. Silage microbiology and its control through additives. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). Market value chain profile, 2010–2011; Pretoria, 2011.

- Nkosi, B. D.; Meeske, R.; Muya, M. C.; Langa, T.; Thomas, R. S.; Malebana, I. M. M.; Motiang, M. D.; Van Niekerk, J. A. Microbial additives affect silage quality and ruminal dry matter degradability of avocado (Persia americana) pulp silage. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 49, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. J.; Kung, L., Jr. The effects of Lactobacillus buchneri with or without a homolactic bacterium on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silages made at different locations. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbell, G.; Weinberg, Z. G.; Hen, Y.; Fily, A. The effects of temperature on the aerobic stability of wheat and corn silages. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 28, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Govea, F. E.; Muck, R. E.; Armstrong, K. L.; Albrecht, K. A. Nutritive value of corn silage in mixture with climbing beans. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 150, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.; Edwards, R. A.; Greenhalgh, J. F. D.; Morgan, C. A.; Sinclair, L. A.; Wilkinson, R. G. Animal Nutrition, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zahiroddini, H.; Baah, J.; McAllister, T. A. Effects of microbial inoculants on the fermentation, nutrient retention, and aerobic stability of barley silage. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 19, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, F.; Wilkinson, J. M.; Jiang, Y.; Ogun Ade, I.; Adesogan, A. T. Silage review: animal and human health risks from silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4093–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, I. M.; Nkosi, B. D.; Erlwanger, K. H.; Chivandi, E. A comparison of the proximate, fiber, mineral content, amino acid and fatty acid profile of Marula (Sclerocarya birrea caffra) nut and soyabean (Glycine max) meals. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, D. M. N.; Mhlanga, B. S. The nutritive value of marula (Sclerocarya birrea) seed cake for broiler chickens: nutritional composition, performance, carcass characteristics and oxidative and mycotoxin status. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Langyan, S.; Sangwan, S.; Rohtagi, B.; Khandelwal, A.; Shivastava, M. Protein for human consumption from oilseed cakes: a review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 856401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Vol. II, 15th ed.; The Association: Arlington, VA, 1990; p. Sec. 985.29. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P. V.; Robertson, J. B.; Lewis, B. A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K. A.; Hamilton, J. K.; Rebers, P. A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S. B.; Summerson, W. H. The colorimetric determination of lactic acid in biological material. J. Biol. Chem. 1941, 138, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, J. D. A modification of the Barker-Summerson method for the determination of lactic acid. Analyst 1969, 94, 1151–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Muslemuddin, M. The accurate determination of volatile nitrogen in meat and fish. J. Assoc. Public Analysts 1968, 6, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M.; Lund, C. W. Improved gas-liquid chromatography for simultaneous determination of volatile fatty acids and lactic acids in silage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1980, 28, 1040–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbell, G.; Weinberg, Z. G.; Azrieli, A.; Hen, Y.; Horev, B. A simple system to study the aerobic determination of silages. Can. Agric. Eng. 1991, 33, 391–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, J. M. A.; Terry, D. R. A two-stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. Grass Forage Sci. 1963, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Makkar, H. P. S.; Becker, K. In vitro gas production: a technique revisited. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 1997, 77, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caisîn, L.; Harea, V.; Bivol, L. Using enterosorbent Praimix Alfasob in feeding growing piglets. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2011, 54, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. U.; Khan, M. N.; Ayaz, M.; Khan, M. I.; Khan, F. Z.; Khan, I. U.; Gul, N.; Nawaz, A.; Khan, M. I.; Ullah, R.; Sultan, S. Economic comparison of sunflower, canola, and soybean meals in dairy cow diets and their impact on milk yield and composition. J. Anim. Plant Res. 2025, 2, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudha, C.; Sarla, L. Nutritional quality analysis of sunflower seed cake (SSC). Pharma Innov. J. 2021, 10, 720–728. [Google Scholar]

- Świątkiewicz, S.; Arczewska-Włosek, A.; Józefiak, D. The use of cottonseed meal as a protein source for poultry: an updated review. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2016, 72, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdziniso, P. M.; Dlamini, A. M.; Khumalo, G. Z.; Mupangwa, J. F. Nutritional evaluation of marula (Sclerocarya birrea) seed cake as a protein supplement in dairy meal. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2016, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong-Boateng, O.; Bakare, A. G.; Nkosi, D. B.; Mbatha, K. R. Effects of different dietary inclusion levels of macadamia oil cake on growth performance and carcass characteristics in South African mutton merino lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, S.; Tolera, A.; Betsha, S.; Dickhöfer, U. Feeding values of indigenous browse species and forage legumes for the feeding of ruminants in Ethiopia: a meta-analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. G.; Allen, M. S. Characteristics of plant cell walls affecting intake and digestibility of forages by ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2774–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L., Jr.; Ranjit, N. K. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri and other additives on the fermentation and aerobic stability of barley silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filya, I. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri, with or without homofermentative lactic acid bacteria, on the fermentation, aerobic stability and ruminal degradability of wheat, sorghum and maize silages. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T. A.; Hristov, A. N. The fundamentals of making good quality silage. Adv. Dairy Technol. 2000, 12, 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A.; Hill, J.; Leaver, J. D. Effect of stage of growth on the chemical composition, nutritive value and ensilability of whole-crop barley. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 152, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J. E.; Andrés, S.; López-Ferreras, L.; Snelling, T. J.; Yáñez-Ruíz, D. R.; García-Estrada, C.; López, S. Dietary supplemental plant oils reduce methanogenesis from anaerobic microbial fermentation in the rumen. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongmun, P.; Wanapat, M.; Pakdee, P.; Navanukraw, C.; Yu, Z. Manipulation of rumen fermentation and ecology of swamp buffalo by coconut oil and garlic powder supplementation. Livest. Sci. 2011, 135, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Shaver, R. Interpretation, and use of silage fermentation analysis reports. Focus Forage 2001, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Addah, W. Microbial approach to improving aerobic stability of silage. Niger. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 24, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Oude Elferink, S. J.; Krooneman, J.; Gottschal, J. C.; Spoelstra, S. F.; Faber, F.; Driehuis, F. Anaerobic conversion of lactic acid to acetic acid and 1,2-propanediol by Lactobacillus buchneri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Saun, R. What is forage quality and how does it effect a feeding program. Lamalink.com 2016, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal, S.; Pamukcu, M.; Curek, M.; Kocaturk, M.; Dogu, O. Y. Silage yield and quality of row intercropped maize and soybean in a crop rotation following winter wheat. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2016, 62, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Prestløkken, E.; Nielsen, N. I.; Volden, H.; Klemetsdal, G.; Weisbjerg, M. R. Precision and additivity of organic matter digestibility obtained via in vitro multi-enzymatic method. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 4880–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Ferreira, R.; de Souza Valente, C.; Rosa Silva, L. C.; Costa de Sousa, N.; Mauerwerk, M. T.; Cupertino Ballester, E. L. Apparent digestibility coefficients of nutrients and energy from animal-origin proteins for Macrobrachium rosenbergii juveniles. Fishes 2024, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agle, M.; Hristov, A. N.; Zaman, S.; Schneider, C.; Ndegwa, P.; Vaddella, V. K. The effects of ruminally degraded protein on rumen fermentation and ammonia losses from manure in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. Soybean meal accelerates fiber degradation by rumen microbiota. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 271, 114792. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y. LAB inoculation enhances fiber degradation in silage by disrupting lignocellulose matrix. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 3201–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Yun, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z. Nutritional quality and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics of silage prepared with lucerne, sweet maize stalk, and their mixtures. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Torres, N.; Garde, S.; Peirotén, A.; Ávila, M. Impact of Clostridium spp. on cheese characteristics: Microbiology, color, formation of volatile compounds and off-flavors. Food Control 2015, 56, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.; Edwards, R. A.; Greenhalgh, J. F. D.; Morgan, C. A.; Sinclair, L. A.; Wilkinson, R. G. Animal Nutrition, 7th ed.; Benjamin Cummings: MUA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.; Novinski, C. O.; Zopollatto, M. Carbon absorption in silages: A novel approach in silage microbiology. In Proceedings of the XVIII International Silage Conference; Bonn, Germany, 24-26 July 2018, Gerlach, K., Südekum, K.-H., Eds.; The University of Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, S.; Alimon, A. R.; Iman, M. N. Effect of Gliricidia sepium leaves and molasses inclusion on aerobic stability, value and digestibility of Napier grass silage. Malays. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Driehuis, F.; Oude Elferink, S. O. The impact of the quality of silage on animal health and food safety: A review. Vet. Q. 2000, 22, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, K. H.; Raab, L.; Salewski, A.; Steingass, H.; Fritz, D.; Schneider, W. The estimation of the digestibility and metabolizable energy content of ruminant feeding stuffs from the gas production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 93, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagadi, S.; Herrero, M.; Jessop, N. S. The influence of diet of the donor animal on the initial bacterial concentration of ruminal fluid and in vitro gas production degradability parameters. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2000, 87, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, Z. G.; Shatz, O.; Chen, Y.; Yosef, E.; Nikbahat, M.; Ben-Ghedalia, D.; Miron, J. Effect of lactic acid bacteria inoculants on in vitro digestibility of wheat and corn silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4754–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschmit, D. H.; Kung, L., Jr. A meta-analysis of the effects of Lactobacillus buchneri on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn, grass and small-grain silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).