1. Introduction

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) is considered as a key technology for future secure optical communications. The main reason is that the security of the present classical cryptography is based on mathematical algoritms, which will no longer be guaranteed when quantum computers become available. QKD, a branch of optical quantum communications, is a technology based on the properties of the quantum light that allows the exchange of secure information between two users, Alice and Bob, who share a random bit series or key transported by quantum light states. Such quantum states can not be cloned by an eavesdropper.

There are several QKD approachs which can be classified into Discrete Variable (DV) and Continuous Variable (CV) QKD [

1,

2,

3]. DV-QKD is based on the measurement of quantum states by projective measurements, and CV-QKD is based on the measurement of the quadratures of the optical field by using, for example, a balanced homodyne detection. Furthermore, there are several types of DV-QKD protocols based on the use of one photon as BB84 [

4], B92 [

5] and so on, and on the other hand there are protocols with two photons as BBM92 [

6], MDI-QKD [

7] and so on. It is important to indicate that in the above cases with two photons, both Alice and Bob only possess one photon. Moreover many of the above protocols have been generalized to high-dimensional protocols by using freedom degrees of the single photons that can be implemented in both multimode optical fibers [

8,

9,

10] and/or free-space [

1,

3]. Likewise, the use of more than two sparticles has atracted the attention, as for example the use of entanglement of product states (three photons) of single photon states to implement a long-distance MDI-QKD protocol (with Bell states) [

11] or the proposal of multi-user protocols (with GHZ entangled states) [

12].

It is well known that security is increased by using high-dimensional QKD, which is obtained as commented above by taking into account some degree of freedom of a single photon in a multimode optical fiber such as: different linear optical momentum (LOM) in few modes optical fibers (FMF), different paths in multicore optical fibers (MCF), different polarization, different orbital angular momentum (OAM) [

13] an so on, that is, with 1-qudits. In this work we present a high-dimensional (HD) DV-QKD protocol in optical fibers by using a number

N of photons. In particular, we use

N-dimensional product states formed by

N single photon states. Each photon can in turn be in a superposition state, therefore we will have

states, that is,

N-qudits, and accordingly a HD-DV-QKD protocol will be implemented, achieving thus both a greater security and larger secure key rate. As a clarification, we will consider that spatial channels , such as cores of a MCF, are not coupled, and importantly the protocol is independent of the relative phase between the single photon states. It is interesting to note that recently a continuous variable QKD protocol based on product states of weak coherent states has also been proposed [

14].

On the other hand, some requirements to produce and detect product states are necessary. One of them is the use of sources of several single photons. There are several possibilities to achieve these states. For example, a series of SPDC (spontaneous parametric down conversion) sources which emit biphotons [

15] or a series of SFWM (spontaneous four-wave mixing) sources also emitting biphotons [

16], and then using one of the photons as a heralding signal to obtain states of

N photons when

N coincidences be detected. Another possibility is to use spatial demultiplexation of single photons from a single photons source [

17]. Therefore, there are enough technological possibilities to produce these kind of product states. Likewise, the measurements of quantum states have to be made by standard projective measurements along with photon coincidences, although this last requirement of coincidences detecting would not be strictly necessary.

The plan of the paper is as follows: in

Section 2 the QKD protocol with

N-qudits in optical fibers is presented by taking account a realistic scenario (perturbations, losses, ...). In

Section 3 different physical implementations of

N-qudits in optical fibers are analysed. In

Section 4 a detailed study of the quantum bit error rate (QBER) and secure key rates (SKR) is presented where an exhaustive analysis is made for an intercept and resend attack with losses and optical fiber perturbations. Finally, in

Section 5 a discussion of results is presented.

2. QKD Protocol with -Qudits in Optical Fibers

In this section we present the QKD protocol with

N-qudits in optical fibers. Let us consider

N photons excited, each of them in quantum superpositions implemented in

d optical modes of optical fibers. These quantum superpositions are generated in two mutually unbiased bases (MUBs), that is, with coefficients

in the

Basis a and

and the

Basis b, where

indicates the base vector,

indicates the component of the vector, and consequently the following superpositions are obtained

If

N photons are considered, then the following product states are obtained in the two bases, that is,

where

and

, with

, indicate some of the superpositions of basis states, given by Eq.(

1), for each photon. It is obvious that we obtain a number

of product states in each basis and therefore a dimension

is obtained.

Alice sends

N-qudit states, that is,

N photons in a product state of

N states of 1-qudit and, more importantly, all 1-qudits (chosen in a random way) are in the same base, that is, she sends states

or

. On the other hand Bob randomly chooses the measurement base of the 1-qudits and then the state of each photon is detected by a projective measurement. Each measurement in the right basis provides a string of

bits, where

. Besides, if an intercept-resend attack is performed by Eve the QBER is related to the error of detecting the right state, that is, since the number of product states in each basis is

then the QBER is given by

It is important to stress that the existence of a relative phase between states of a product state does not change the state, up to a global phase. This property provides a great robustness to these states. Obviously each photon is excited in a superposition states where perturbations on the relative phases and amplitudes are possible, and therefore some compensation technique would be required. This problem has been extensively studied in the past by usign both passive (plug&play) and active methods.

On the other hand, we take into account that the current optical fibers have a certain attenuation loss, that means that some photons will be lost, and therefore the

N-qudits convert in

-qudits, that is,

N−1-qudits,

N−2-qudits ..., 1-qudit. For that reason, we will also have to consider this most realistic scenario. Thus, in an optical fiber the probability

P to detect a photon at a distance

L is related to the attenuation, that is,

where

is the attenuation coefficient in the optical fiber in dB/km. Typical values are

−

dB/km for conventional fibers, however, in this analysis we will make use of an attenuation coefficient value

which takes into account the new advances in fiber design technologies [

18]. This value is chosen to emphasize that this protocol is feasible even without employing hollow core fibers whose coefficient is

[

19] . Note that if we have product states of

N photons then we obtain several effective

-qudits under attenuation. For example if we have

we obtain in the base

a (the same for the base

b)

therefore the probability to detect product states with three photons is given by

, with

, however the probability to detect product states with two photons is

, and the probability to detect product states with one photon is given by

. This result can be generalized to

N photons of which

are detected, that is,

In short, the attenuation will introduce limitations to the total secure key rate and the maximum distances allowed. However, by using several photons we overcome this problem increasing the security significantly. For example, let us consider the case of 1-ququart (d=4), then the error produced by Eve is 37.5%, however if we use 2 or 3 photons, that is, 2 and 3-ququart respectively, we obtain an error 46.875% or 49.92%, that is, close to the maximum error of 50%.

3. Implementations in Optical Fibers

Different kinds of optical fibers can be used to implement the above protocol. Since non spatial modal coupling is required, the most interesting cases correspond to the use of a set of single mode fibers (SMF) or a multicore optical fiber (MCF) with N cores. A first approximation would be to use two polarization modes in each core and then N-qubit states can be implemented, that is, N photons are distributed into the N cores and, therefore, polarization qubits are implemented in each core resulting in a QKD of dimension .

Alternatively, we may employ

N subsets of

M cores in a MCF supporting

spatial modes, where each photon is simultaneously excited across

M cores. By exploiting polarization modes, each subset encodes a single qudit of dimension

. Consequently, the system represents states of

N-qudits, spanning a quantum space of dimension

The last expresion shows us that for a given number of cores

, the highest dimension

is achieved for

(qubits) or

(ququarts).

A key aspect of optical fibers is that the polarization state of the quantum states is changed during their propagation, which supposes a critical caveat in the real implementation of these QKD protocols. As a consequence, we have to deal with perturbations to ensure the stability of the polarization state. To compensate the perturbations in the polarization when the states are send from Alice to Bob, active compensation [

20,

21] or passive compensation (autocompensation) [

10,

22] techniques represent a plausible and suitable solution.

3.1. Product States with N-Qubits with Spatial and Polarization Modes

We start with the implementation of

N-qubits, that is, we have

N spatial modes

of a MCF or

N SMFs and, in each spatial mode, we excite a single photon and therefore

N-qubits by using the polarization modes in each spatial mode. We choose, for example, the bases:

Basis a: X (or diagonal) and

Basis b: Y (or circular) basis (MUBs):

As an example, let us consider three photons (

) then we can use a three-core MCF or three SMFs. Therefore the product states in the bases X and Y are

The bits corresponding to the states can be, for example,

: 0,

: 1,

: 0 and

: 1. Note that with one photon we would need a space with eight optical modes. If we use an additional photon (four photons) we would obtain sixteen product states (with one photon we would need a space with sixteen optical modes) and so on.

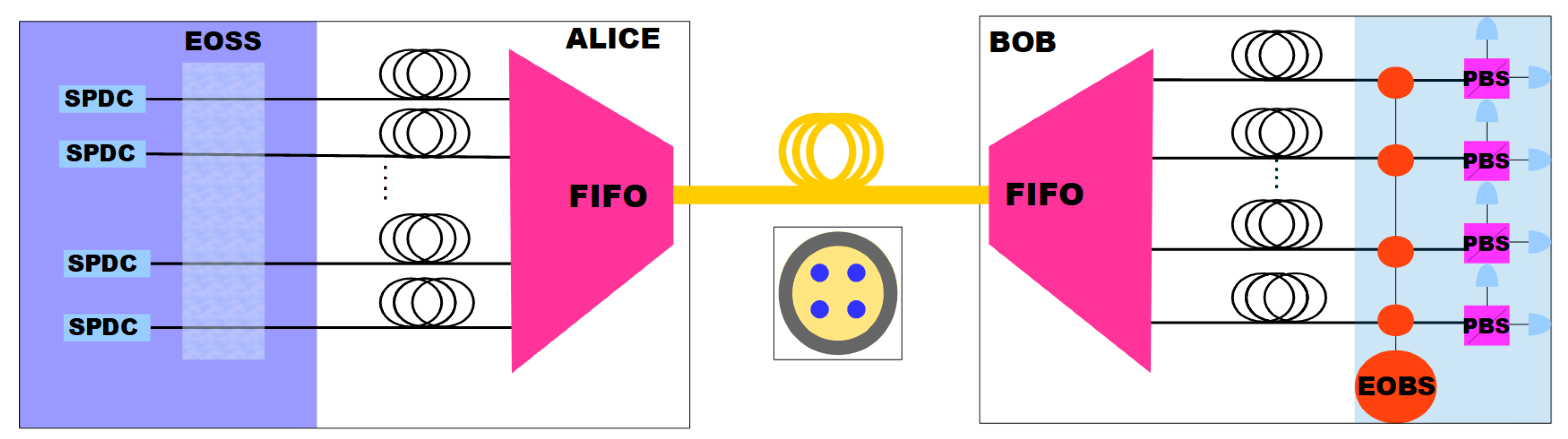

In

Figure 1 there is a depiction of a HD-DV-QKD system for polarization qubits. First of all, Alice uses

N SPDC sources to generate a pair of photons for each mode: one of them will be used as a signal and the other one as a heralding photon to obtain

N-qubits by detecting coincidences. After, by using electrooptical devices, Alice chooses a state for each signal photon, all of them in the same basis, for example, X or Y. The photons are coupled to SMFs, and by means of a fan-in (FI) are coupled to a MCF. The quantum states travel along the MCF to Bob system where by using a fan-out (FO) the photons are coupled to

N single core fibers at Bob’s system. Finally, at Bob’s quantum projective measurement system, the same base is selected with an electrooptical device. Finally, the quantum states are measured using a polarization beam splitter (PBS) for each qubit.

3.2. Product States with N-Qudits with Spatial and Polarization Modes

We make clear the case of

N-qudits with

N-ququarts states. The ququarts states

are generated by using two spatial modes 1 and 2 (two non-copled cores of a MCF, or two SMFs) and the polarization modes

H and

V, that is, they are given by the following quantum superposition

where the coefficients are the vectors of the two MUBs. For example, the above diagonal and circular polarization basis can be used to obtain two MUBs for 1-ququarts, that is,

If we have a second photons then we need a second pair of spatial modes cores of MCF or SMFs) 3 and 4, and so on for

N-ququarts. The states in each pair of modes are again given by Eq.(). Examples of states 2-ququarts of the first and second pairs of modes would be:

,

,

,

, and so on up to sixteen states. This can be implemented by using a MCF with four cores (two cores for each photon). A similar procedure can be followed for 3-ququarts, that is, sixty-four states. It is clear the large dimension that can be achieved. Note that with a single photon we would need to use and manipulate quantum superposition states excited in sixteen or sixty-four optical modes respectively to achieve the same QKD dimension.

3.3. Product States with N-Qudits with Spatial and Other Optical Modes

There are other degrees of freedom for a single photon, that is, other optical modes to construct

N-qudits. For example, we could use the modes of a few-mode optical fiber (FMF) [

23], that is, with different Linear Optical Moment (LOM), or even to consider a MCF optical fiber where each core is a few-mode optical core, with LOMs

, where

are the mode propagation constants. Likewise, we could consider an optical fiber with a few modes with different Orbital Angular Momentum (OAM) [

24], or a MCF where each core has a few modes with different OAM, that is, with OAMs

, where

. It is important to underline the possibility of using polarization maintenance optical fibers [

25] because it can sometimes have certain advantages. A single example would be

N optical fibers (or cores) with the first three modes with OAMs

, then we will obtain

N-qutrits, and therefore dimension

.

4. Study of Secure Key Rates

In this section a detailed study is presented about secure key rates with the proposed protocol. We will focus our study on product states of N-qubits and N-ququarts although more general N-qudits could be also considered. Obvioulsy qudits with could be also considered but qubits and ququarts provide sufficient possibilities to implement HD-QKD. In order to evaluate the security properties of the protocol with product states we will assume the following realistic scenario: an eaversdropper attack under imperfect channel having both losses and optical perturbations which produce unpredictable polarization coupling and phase changes. We also assume the existence of phase and polarization compensation systems, which greatly will reduce these random perturbations but do not fully eliminate them. Next, we will model the QBER model including the aforementioned optical perturbations and the Eve’s presence under an intercept and resend attack. Finally, we present secure key rates with losses, that is, we will take into account the fact that quantum states can suffer from photon losses and we present new secure key rate curves under an intercept-resend attack. In particular, we prove that secure key rates are notably improved by using detections of -qudits, that is, employing additional detections where some photons have been lost due to fiber losses.

4.1. Optical Perturbations Model

A model for the optical perturbations is needed to calculate the perturbation error for N-qudits, in particular, for the product of N-qubits and N-ququarts states. We calculate the effect of polarization modal coupling and phase perturbations, that is, the changes of a quantum state that experiences such perturbations under propagation along optical fibers.

Let us consider a polarization 1-qubit state propagating through a core

j of a multicore optical fiber (or a single mode optical fiber

j), as for example, an initial state

given by Eq.(

8) which is excited in a linear polarization diagonal mode (

). It becomes the following perturbated state

due to polarization modal coupling described by

between diagonal (

D) and anti-diagonal (

A) linear modes, and phase perturbations described by

. From now on we assume statistical independence in

and

, and the same statistical behaviour in all cores, then we choose

and

. Therefore, the probability of remaining in the initial state for an N-qubit state is given by

where

represents an stadistical average over the posible values of

. Note that Eq.(

14) does not depend on the phase perturbation pertubation

.

Analogously, let us consider 1-ququart

excited in the pair of cores

j and

, then under perturbation becomes the following perturbated state

. By asssuming again statistical independence in

,

and

and the same statistical behaviour (

), it can be easily obtained that the probability of an initial N-ququart state

to remain unperturbed is given by

Next we calculate the statistical average, of the previously obtained functions, that is,

and

in Eqs.(

14) and (

15), over a normalized gaussian probability densities of variance

(polarization modal coupling) and

(phase) respectively, where

L is the length and

and

are the coefficients characterizing the strength of the residual (non compensated) perturbations.Therefore we write

where we use the interval (

,

∞) because we assume that

and

can take values over the entire real line (unwrapped angles), although in our case it is also justified due to the small variances obtained under compensation methods of these perturbations. Finally we get for

N-qubits and

N-ququarts

It is remarkable that Eq.(

19) depends on

and

, therefeore,

N-qubits technology would be more easily implemented in practical systems because they only depend on the polarization coupling pertubation, however, the proposed 1-ququarts also have phase perturbations, although obviously

N-ququarts with a high performance could be also implemented. We could claim, from a technological point of view, that the use of qudits with

would have greater implementation difficulties due to the fragility of these states to optical perturbations. Thus for

we could use 3-qubits states (three photons), which would be most robust to optical perturbations since would be insensitive to phase perturbations.

4.2. QBER with Perturbations

In order to calculate the QBER, we have to take into account the sources of errors due to Eve’s attack and the before mentioned optical perturbations. The first one of them can be written as

where

a is the fraction of attack, that is, the rate of bits intercepted by Eve and

is Eve’s QBER. It is known that intercept-resend attack is the most direct QKD attack. We use this attack to describe the security properties of the QKD protocol with product states. As usual, Eve has to choose a measurement basis and, because she makes a wrong choices, the QBER is given by Eq.(

3), that is,

.

Next, we will calculate Bob’s QBER

equations for N-qbits and N-ququarts. If we consider errors due to optical perturbations

, then we can define an error

, with

if we send qubit states or

for ququarts. It represents the probability of getting a mistaken bit due to perturbations.

A and

B are constants to be determined by the following boundary conditions:

, where

is the error due to the Eve’s attack, and

, therefore we obtain for the expression

Note that for qubits

and for ququarts

. Using this results we write down the expressions for Bob’s QBER

For sake of illustrative purpose we choose a value

which can be achieved by compesating techniques [

26]. Moreover, we consider that the coefficient

can takes values equal to several times

because of the larger technological difficulty to compensate phase perturbations, in particular we take

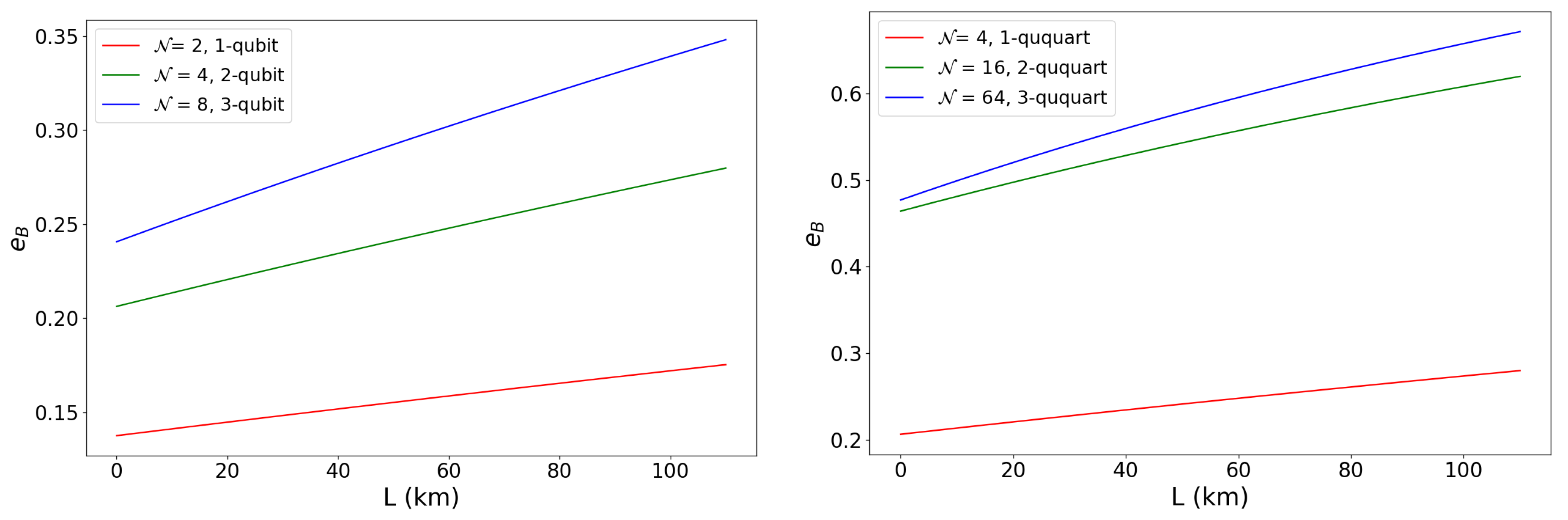

and therefore both perturbations provide similar statatistical properties. In

Figure 2 we show two examples of the QBER

L for diferent product of qubits (left) and ququarts (right) states. It is clear that we gain more resilience to Eve when we increase dimension. We remind that although the security is higher for ququarts, their implementation is harder due to the phase parameter, on the contrary qubits are more implementable because they only depend on polarization modal coupling. In short, when the phase perturbation is important then the high-dimensional QKD could be implemented with N-qubits that do not present phase perturbation.

4.3. Secure Key Rate with -Qudits Under Attack in Line

As commented, we will consider that Eve is present and that the channel has an optical attenuation (attenuation coefficient

≈

). The secure key rate

R by using

N-qudits can be calculated by taking into account the GLLP security analysis [

27] and therefore by using the mutual information

between A and B with

=

states where the information lost during error correction is

, with

the Shannon entropy,

x the total QBER and

f the reconciliation efficiency. Therefore, under a fraction of attack

a, the rate

R can be written as follows

where the second term term on the right side represents the information loss by Bob due to the channel error and the presence of Eve, and the third term is the mutual information

[

28] multiplied by the attack fraction

a, where as usual it is assumed that Eve has all the technology to eliminate the classical errors. From now on we will use an acceptable value

[

29].

As commented above we have to take into account the possible lost photons and therefore not detected by Bob, which means that despite the channel losses, the remaining photons, that is, remaining qudits of lower

dimension can still be employed to produce a secret key. By means of the probabilities given in

Section 2, we can weight the secret key rates given by Eq.(

22) according to the number of lost photons:

, that is,

=

,

=

, ... ,

=

,

=

. Consequently, the total secure key rate

is the sum of these ponderated secure key rates, that is,

Next we present a detailed analysis without and with attack in line for some

N-qudits with a certain practical interest. We calculate, for the purpose of illustration, examples of secure key rates for the case of 1, 2 and 3-qubits (dimensions

), that is,

and 1-ququart (dimension

), that is,

. The ponderated sums of these secure keys rates are given by the following expressions for 1-qubit, 2-qubits and 3-qubits,

and the following expression for the total secure key rate when 1-ququart, 2-ququarts and 3-ququarts are used

Note, for example, that the total secure key rate

for 3-qubits consists of the weighted contribution of the secure key rates from a tri-photon channel, three bi-photon channels and another three single photon channels, which is equivalent to detect one triple coincidence (tri-photon-channel), three double coincidences (bi-photon channels) and three single detections (single photon channels). Analogously, similar considerations can be made for the rest of the cases. On the other hand, we must note that the losses in the optical fiber give rise to a small amount of

N photon coincidences, what suggests that such coincidences could be used to check whether Eve is tapping. The main argument is that, although the

N photons coincidences are very unlikely in longer distances and therefore their contribution to the total secure key is very small, they can detect quickly the presence of Eve because of the greater contribution to Bob’s quantum bit error rate (QBER) that increases with dimension.

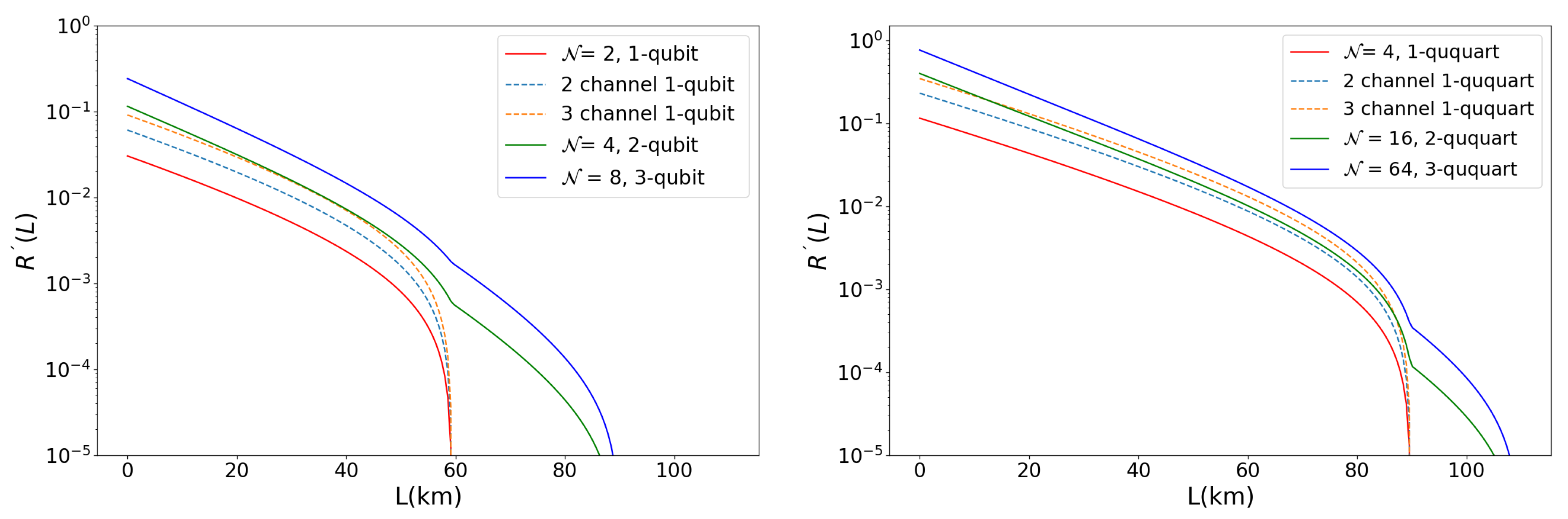

Moreover, dimensionality implies a longer distance reached and secure key gain for the protocol. In

Figure 3, two SKR curves

vs L are depicted for qubits (left) and ququarts (right) for a rate of attack

a = 0.55 (left). As expected, it is also interesting to indicate that a simple inspection shows that parallel single photon channels provide lower secure key rates, that is,

,

for qubits and

,

for ququarts. Finally, the SKRs sums results in the small down spikes in higher dimension curves. They are ocated at the distances where multiple photons coincidences become less probable than coincidences of lower number of photons.

5. Discussion

In this work, a high-dimensional discrete variable QKD protocol based on product states has been proposed, that is, by using N-qudits states formed by the product states of N photons each in 1-qudit states. Examples of N-qubits, N-ququarts have been presented and analyzed. The QKD states measurement combine projective measurements with photon coincidences, although such coincidences would not be strictly necessary. For the two products states technologies analysed in detail, that is, N-qubits and N-ququarts,the results show that security key rates improve notably when compared to the paralellization of N single photon channels. For this, we can obtain a total secure key rate as the weighted sum of secure key rates for -qudits ) . Moreover, the states with a maximum number of N photons, that is, the least probable states, can be used for checking the security of the quantum channel. Finally, if only compensation of polarization is achieved, then N-qubits high dimensional protocol is a suitable choice for implentation; if polarization and phase compensation is available then N-ququarts are also an adecuate proposal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; methodology, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; validation, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; formal analysis, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; investigation, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; writing—review and editing, J.L., X.P-B. and A.V-M.; supervision, J.L. and X.P-B.; project administration, J.L., X.P-B.; funding acquisition, J.L. and X.P-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the MICIN, European Union NextGenerationEU under Grant PRTR-C17.I1, and in part by the Galician Regional Government through Planes Complementarios de I+D+I con las Comunidades Autónomas in Quantum Communication. It was also funded by MCIU/ AEI / 10.13039/501100011033 / FEDER, UE under project PID2023-152607NB-I00.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QKD |

Quantum Key Distribution |

| DV |

Discrete variable |

| CV |

Continuous variable |

| DV-QKD |

Discrete variable Quantum Key Distribution |

| CV-QKD |

Continuous variable Quantum Key Distribution |

| BB84 |

Bennet Brassard 1984 protocol |

| B92 |

Bennet 1992 protocol |

| BBM92 |

Bennet Brassard Mermin 1992 protocol |

| MDI-QKD |

Measurement-Device-Independent Quantum Key Distribution |

| GHZ |

Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state |

| LOM |

Linear optical momentum |

| FMF |

Few modes optical fibers |

| MCF |

Multicore optical fibers |

| OAM |

Orbital angular momentum |

| HD |

High dimensional |

| HD-DV-QKD |

High dimensional Discrete variable Quantum Key Distribution |

| SPDC |

Spontaneous parametric down conversion |

| SFWM |

Spontaneous four-wave mixing |

| MUB |

Mutually unbiased bases |

| QBER |

Quantum bit error rate |

| SMF |

Single mode fibers |

| PL |

Photonic lantern |

| EOSS |

Electrooptical states selector |

| EOBS |

Electrooptical basis selector |

| PBS |

Polarization beam splitter |

| GLLP |

Gottesman-Lo-Lutkenhaus-Preskill |

References

- Gisin, N.; Ribordy, G.; Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 145–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy-Hejamadi, A.; Pathak, A.; Radhakrishna, S. Quantum Cryptography: Key Distribution and Beyond. Quanta 2017, 6, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirandola, S.; Andersen, U.L.; Banchi, L.; Berta, M.; Bunandar, D.; Colbeck, R.; Englund, D.; Gehring, T.; Lupo, C.; Ottaviani, C.; et al. Advances in quantum cryptography. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2020, 12, 1012–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, C.H.; Brassard, G. Quantum Cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing. In Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computers, Systems and Signal Processing; 1984; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H. Quantum cryptography using any two nonorthogonal states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3121–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Mermin, N.D. Quantum cryptography without Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.K.; Curty, M.; Qi, B. Measurement-Device-Independent Quantum Key Distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 130503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañas, G.; Vera, N.; Cariñe, J.; González, P.; Cardenas, J.; Connolly, P.W.R.; Przysiezna, A.; Gómez, E.S.; Figueroa, M.; Vallone, G.; et al. High-dimensional decoy-state quantum key distribution over multicore telecommunication fibers. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 022317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Bacco, D.; Dalgaard, K.; Cai, X.; Zhou, X.; Rottwitt, K.; Oxenlowe, L. High-dimensional quantum key distribution based on multicore fiber using silicon photonic integrated circuits. npj Quantum Inf 2017, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balado, D.; Liñares, J.; Prieto-Blanco, X.; Barral, D. Phase and polarization autocompensating N-dimensional quantum cryptography in multicore optical fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2019, 36, 2793–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Qi, B.; Liao, Z.; Lo, H.K. Long distance measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution with entangled photon sources. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 103, 061101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Hu, M.; Guo, B. Multi-User Measurement-Device-Independent Quantum Key Distribution Based on GHZ Entangled State. Entropy 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Milione, G.; Lavery, M.P.J.; Xie, G.; Ren, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ahmed, N.; An Nguyen, T.; Nolan, D.A.; Li, M.J.; et al. Mode division multiplexing using an orbital angular momentum mode sorter and MIMO-DSP over a graded-index few-mode optical fibre. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 14931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Martínez, A.; Prieto-Blanco, X.; Mateo, E.; Liñares, J. 2N-dimensional autocompensating discrete

modulation CV-QKD protocol in optical fibers. arXiv: 6707418 [quant-ph] 2025.

- Collins, M.J.; Xiong, C.; Rey, I.H.; Vo, T.D.; He, J.; Shahnia, S.; Reardon, C.; Krauss, T.F.; Steel, M.J.; Clark, A.S.; et al. Integrated spatial multiplexing of heralded single-photon sources. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koefoed, J.G.; Friis, S.M.M.; Christensen, J.B.; Rottwitt, K. Spectrally pure heralded single photons by spontaneous four-wave mixing in a fiber: reducing impact of dispersion fluctuations. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 20835–20849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzberg, J.; Draxl, F.; Covre da Silva, S.F.; Karli, Y.; Manna, S.; Rastelli, A.; Weihs, G.; Keil, R. Fast and efficient demultiplexing of single photons from a quantum dot with resonantly enhanced electro-optic modulators. APL Photonics 2022, 7, 070802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Tamura, Y.; Sakuma, H.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Koyano, Y. The first 0.14-dB/km ultra-low loss optical fiber. SEI Tech. Rev 2018, 86, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich, M.; Fokoua, E.; Chen, Y.; Sakr, H.; Adamu, A.; Hassan, R.; Wu, D.; Ando, R.; Papadimopoulos, A.; Sandoghchi, S.; et al. Broadband optical fibre with an attenuation lower than 0.1 decibel per kilometre. Nature Photonics 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Han, Z.; Mo, X.; Xu, F.; Wei, G.; Guo, G. Active phase compensation of quantum key distribution system. Chinese Science Bulletin 2008, 53, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Shields, A. One-way quantum key distribution system with active phase compensation. In Proceedings of the 2005 European Quantum Electronics Conference, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2005; p. 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, D.S.; Risk, W.P. Autocompensating quantum cryptography. New Journal of Physics 2002, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillard, P.; Bigot-Astruc, M.; Molin, D. Few-Mode Fibers for Mode-Division-Multiplexed Systems. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2014, 32, 2824–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Orbital Angular Momentum in Fibers. J. Lightwave Technol. 2023, 41, 1934–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J.; Mo, Q.; Chen, X.; Chen, B.; Tang, M.; Liu, D. Panda Type Few-Mode Fiber Capable of Both Mode Profile and Polarization Maintenance. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2018, 36, 5780–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñares, J.; Prieto-Blanco, X.; Balado, D.; Carral, G.M. Fully autocompensating high-dimensional quantum cryptography by quantum degenerate four-wave mixing. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 043710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D.; Lo, H.K.; Lutkenhaus, N.; Preskill, J. Security of quantum key distribution with imperfect devices. In Proceedings of the International Symposium onInformation Theory, 2004. ISIT 2004. Proceedings, 2004; p. 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourennane, M.; Karlsson, A.; Björk, G.; Gisin, N.; Cerf, N.J. Quantum key distribution using multilevel encoding: security analysis. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 2002, 35, 10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkouss, D.; Martinez-Mateo, J.; Martin, V. Information reconciliation for quantum key distribution. Quantum Info. Comput. 2011, 11, 226–238. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).