Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Redefining “Learning and Leisure Activities” in Dementia

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Cognitive Training and Learning Interventions

- (i)

- comprehension and memory;

- (ii)

- accurate task performance;

- (iii)

- continuous self-management; and

- (iv)

- tolerance for evaluation.

2. Constraints in Learning and Leisure Activity Interventions

2.1. Cognitive Constraints: Difficulties in Comprehension, Memory, and Self-Regulation

2.2. Emotional Constraints: Failure Experiences Trigger BPSD

2.3. Implementation Constraints: Care Burden and Daily Care Pathways

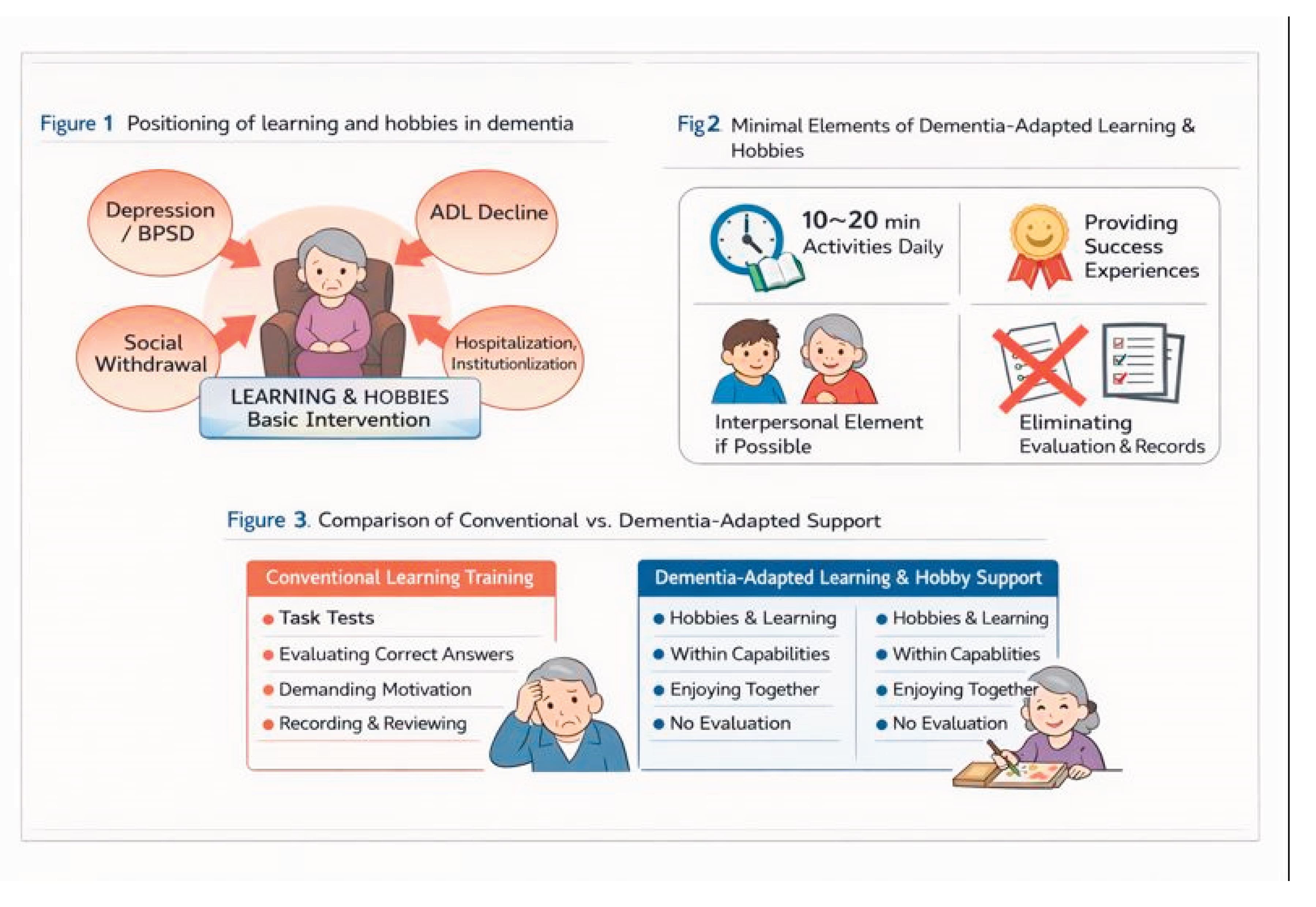

3. Distinguishing Active Ingredients from Excessive Burden

3.1. Core Active Ingredients

- Maintenance of engagement: Prevents fixation of disengagement and apathy

- Securing successful experiences (achievement/pleasure): Preserves reward systems and self-efficacy

- Addition of social context (interpersonal elements when feasible): Simultaneously promotes stimulation, arousal, and emotional stability

- Minimal repeatable units: Even short activities that can be performed “every day”

3.2. Excessive Implementation Burdens to Be Removed

- Evaluation of correct answers or achievement levels (test-like formats)

- Requiring motivation or sustained willingness from the person

- Complex rules or tasks requiring memory

- Decision-making burdens caused by offering multiple choices

- Obligatory recording, scoring, or reflection

4. Dementia-Adaptive Minimal Model of Learning and Leisure Activities

4.1. Minimal Component ①: 10–20 Minutes per Day of “Meaningful Activity” (Including Leisure)

- Leisure: coloring, origami, gardening, partial sewing tasks, arranging a shogi board, simple musical instruments, singing

- Roles: assisting with meal setup, folding towels, sorting, wiping, arranging

- Language: reading aloud, short read-aloud sessions, reminiscence using old photographs

- Sensory: keeping rhythm, hand and finger movements (focus on process rather than completion)

4.2. Minimal Component ②: Difficulty Set to Ensure Successful Experiences (“Leaning Toward Can-Do”)

- Early termination is acceptable; completion is not required

- Demonstrate and perform together rather than explaining verbally

- Do not correct mistakes; do not evaluate outcomes based on product quality

4.3. Minimal Component ③: Interpersonal Elements When Possible (One-to-One Is Sufficient)

4.4. Minimal Component ④: Removal of Evaluation and Self-Management Demands (Shifting Responsibility to the Environment)

5. Implementation Protocol (Summary)

- Frequency: Daily (short duration)

- Format: Same time, same place, same tools (predictability)

- Leader: Caregiver-led (does not assume user initiative)

- Recording: Simple ○/× check only (no evaluation)

6. Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

7. Conclusion

Appendix

- disengagement

- apathy

- activity avoidance

- emotional instability

- behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)

- care staff working in residential care facilities or home-care settings

- family caregivers supporting people with dementia

- medical and welfare professionals seeking to integrate learning and leisure activities into daily care without excessive burden

- This manual is not a clinical trial protocol, but an implementation guide for routine care.

- It does not claim therapeutic efficacy or cognitive improvement from learning or leisure activities.

- People with mild to moderate dementia

- Individuals who respond to simple verbal cues, imitation, or non-verbal guidance

- Individuals capable of engaging in short-duration activities in daily life

- Persistent severe agitation, refusal, or irritability that prevents safe implementation

- Marked exacerbation of BPSD triggered by activity-related stimulation

- Medically unstable conditions such as acute delirium, severe pain, or significant physical illness

- Final decisions should always prioritize clinical judgment.

- Even in advanced dementia, this program may be adaptively applied as presence-affirming activities when outcomes or responses are not demanded.

- Do not require comprehension, memory retention, or learning outcomes

- Do not evaluate correctness, completeness, or improvement

- Do not correct, instruct, compare, or reprimand

- Immediately reduce or stop the activity if anxiety, confusion, or refusal is observed

- Fix activity content, timing, and procedures as much as possible

- Avoid framing activities as special events

- Do not assume motivation, judgment, or self-management by the person

- Consider support successful even if the person does not actively “participate”

- Learning and leisure activities: daily, 10–20 minutes

- Interpersonal interaction (when feasible): short one-to-one engagement

- Verbal prompting and initiation: embedded within routine daily care

- Familiar living environments

- Quiet settings that avoid excessive stimulation

- Minimal preparation, movement, and choice requirements

- Prevent fixation of disengagement and apathy

- Maintain daytime activity levels and emotional stability

- Fix activities that the individual has previously enjoyed or resists least

- Do not require completion, understanding, or measurable outcomes

- Leisure: coloring, origami, knitting, gardening (watering only), singing

- Learning-like activities: reading aloud, short read-aloud sessions, simple calculation-like tasks

- Role-based activities: folding towels, sorting, arranging, wiping

- “Let’s try this together for a little while.”

- “It’s okay to stop at any time.”

- Prevent refusal or BPSD triggered by failure experiences

- Reduce difficulty to a clearly achievable level

- Treat incomplete or partial engagement as success

- Correcting mistakes

- Referring to improvement or performance outcomes

- Support attention, arousal, and emotional stability

- Engage together in a one-to-one format

- Emphasize parallel or supportive presence

- Do not force group participation

- Do not check whether the person remembers or understands

- Cognitive training or test-like learning formats

- Interventions that evaluate correctness, achievement, or outcomes

- Persuasive approaches aimed at eliciting motivation or willingness

- Interactions requiring decision-making through choice presentation

- This is not an exclusion of learning stimuli per se, but a restructuring of format.

- This manual does not constitute an intervention study designed to quantitatively verify the effectiveness of a specific learning program.

- Its primary aim is to present an implementation framework adapted to the cognitive and emotional constraints of dementia, based on existing theoretical, review, and implementation studies.

- Duration (shortening is acceptable)

- Activity content (simplification)

- Amount of interpersonal stimulation

- Clear anxiety, refusal, or agitation

- Increased fatigue or confusion

- Signs of BPSD exacerbation

- Physical risks are extremely low

- The greatest risk is accumulation of failure experiences

- Do not demand perfect implementation or consistent success

- 9. Consistency with Existing Evidence

- Associations between apathy, reduced activity, and functional decline

- Findings on apathy reduction through non-pharmacological interventions

- Relationships between social engagement and cognitive or functional decline

- Supplementary material describing intervention content

- Documentation of implementation methods and fidelity

- Simplified manuals for care staff

- Guides for family caregivers

- Shared reference materials for care policy discussions

References

- Brodaty, H.; Burns, K. Nonpharmacological management of apathy in dementia: A systematic review. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2012, 20(7), 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, R.; Leung, W. G.; Fearn, C.; John, A.; Stott, J.; Spector, A. Effectiveness of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for mild to moderate dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 97 2024, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratiglioni, L.; Paillard-Borg, S.; Winblad, B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. The Lancet Neurology 2004, 3(6), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiper, J. S.; Zuidersma, M.; Oude Voshaar, R. C.; et al. Social relationships and cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 22 2015, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, P.; Onyike, C. U.; Leentjens, A. F.; Dujardin, K.; Aalten, P.; Starkstein, S.; et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. European Psychiatry 2009, 24(2), 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).