1. Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) and its more severe form, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), are life-threatening inflammatory conditions characterized by diffuse alveolar damage, pulmonary edema, and respiratory failure [

1]. Despite advances in critical care medicine, ALI remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with limited therapeutic options available [

2]. The pathogenesis of ALI involves complex inflammatory cascades triggered by various insults, including bacterial infections, where lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria plays a pivotal role in initiating and amplifying the inflammatory response [

3].

LPS activates alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells by binding to its receptor toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the cells, and triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as chemokines including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) [

4,

5]. These inflammatory mediators promote neutrophil recruitment, increase vascular permeability, and cause tissue damage, ultimately leading to impaired gas exchange and respiratory failure [

6]. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting excessive inflammatory responses represent a promising approach for ALI management. Polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) is a mixture of deoxyribonucleotide polymers included in various biological sources, typically salmon sperm [

7]. PDRN has been extensively studied for its tissue repair, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory properties, primarily through activation of adenosine A2A receptors [

8,

9]. Clinical applications of PDRN include treatment of chronic wounds, osteoarthritis, and various inflammatory conditions [

10,

11]. However, most studies have focused on PDRN derived from salmon (

Oncorhynchus spp.), and the therapeutic potential of PDRN from alternative marine sources remains largely unexplored.

Porphyra sp., commonly known as laver or nori, is a marine red algae widely consumed as a traditional food in East Asian countries [

12]. This edible seaweed is rich in bioactive compounds including polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids [

13]. Recent advances in extraction technology have enabled the isolation of PDRN from

Porphyra sp., yielding a mixture of polydeoxyribonucleotide and polynucleotide with a molecular weight range of 5–1,000 kDa [

14]. Given the abundant availability and sustainable cultivation of

Porphyra sp., this marine-derived PDRN represents a promising alternative source for therapeutic applications. In recent, we demonstrated that

Porphyra sp.-derived PDRN (Ps-PDRN) has anti-inflammatory activity to inhibit nitric oxide (NO) production from LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages by suppressing the activation of

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 [

15]

.

In this study, we investigated the inhibitory effects of Ps-PDRN on ALI in an in vivo mouse model, and analyzed the related immunological mechanisms in lung tissue. Notably, we compared two administration routes—intranasal (IN) and oral (PO)—to evaluate both local and systemic therapeutic approaches. Additionally, we examined the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Ps-PDRN using LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Our findings provide the first evidence for the protective effects of Porphyra sp.-derived PDRN against ALI, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic agent for inflammatory lung diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Ps-PDRN

Ps-PDRN were prepared according to the method previously described [

15]. Briefly,

Porphyra sp. was washed three times with tap water to remove surface epiphytes, residual salts, and sand, followed by careful rinsing with fresh water. The cleaned samples were stored at −20°C until processing, then freeze-dried and finely homogenized to obtain a dry powder. The powdered Porphyra sp. was lysed in a protein lysis buffer composed of 10 wt% soybean, 10 wt% adlay, 20 wt% green tea extract, 20 wt% soybean fatty acid, 20 wt% tocopherol, cocamidopropyl betaine, and 20 wt% olive oil carboxylate. Ribonucleases were subsequently added to separate polynucleotides and PDRN. The lysate was then subjected to centrifugation and filtration to remove insoluble residues and other impurities. The clarified filtrate was dried, washed, and centrifuged to obtain low–molecular weight Ps-PDRN. The final extract was concentrated by evaporation and lyophilized, yielding powdered Ps-PDRN, which was stored at −80°C until use. The purity of Ps-PDRN was assessed by measuring the absorbance ratio at 260 and 280 nm (A260/A280), and the DNA concentration was determined from the absorbance at 260 nm using a microplate reader (PowerWave XS2, BioTek Instruments, Inc.). The purity of isolated Ps-PDRN was ≧99%.

2.2. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Assay

RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity of Ps-PDRN was assessed using the MTT assay. Cells (5 × 104/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 8 h. Cells were then treated with various concentrations of Ps-PDRN (0–100 μg/mL) for 12 h, followed by stimulation with LPS (1 μg/mL; Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h. MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added, and cells were incubated for 2 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader.

2.3. Determination of Cytokines in Cell Culture

RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with Ps-PDRN at indicated concentrations for 12 h, followed by LPS (100 ng/mL) stimulation for 24 h. The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the culture supernatants were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from RAW 264.7 cells or lung tissues using TRIzol reagent (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Republic of Korea). cDNA was synthesized using a power cDNA synthesis kit (iNtRON Biotechnology), and quantitative real-time PCR was performed using Cfx96 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were normalized to GAPDH. The primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

2.5. Animal Experiments

Seven-week-old male BALB/c mice (19–22 g) were purchased from Raon Bio (Yongin, Republic of Korea). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Konyang University (Approval No. P-25-12-A-01). Mice were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 7 per group): (1) Normal control; (2) LPS (vehicle); (3) LPS + Dexamethasone (DEX, 5 mg/kg/mouse, positive control); (4) LPS + Ps-PDRN IN-Low (IN-L, 25 μg/mouse); (5) LPS + Ps-PDRN IN-High (IN-H, 50 μg/mouse); (6) LPS + Ps-PDRN PO-Low (PO-L, 100 μg/mouse); and (7) LPS + Ps-PDRN PO-High (PO-H, 200 μg/mouse). For intranasal administration groups, Ps-PDRN was administered intranasally once daily for three days before ALI induction. For oral administration groups, Ps-PDRN was administered by oral gavage once daily for three days before ALI induction. ALI was induced by intranasal administration of LPS (100 μg/mouse). Mice were sacrificed 18 h after LPS administration, and lung tissues, blood, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were collected for analysis.

2.6. Body Temperature and Lung Edema Assessment

Body temperature was measured using a rectal thermometer 24 h after LPS administration. For lung edema assessment, lungs were excised, weighed (wet weight), and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 48 h to obtain dry weight. The wet/dry (W/D) ratio was calculated as an indicator of pulmonary edema.

2.7. BALF and Serum Analysis

BALF was collected by lavaging the lungs three times with 1 mL of cold PBS. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and centrifuged to obtain serum. The concentrations of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and chemokines (MCP-1, RANTES, CXCL1, MIP-2) in BALF and serum were measured using ELISA kits (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

2.8. Histological Analysis

Lung tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Image-IT™ Fixative Solutions; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), dehydrated with 30% sucrose solution, and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA Inc., Torrance, CA, USA). Frozen sections were prepared using a cryosectioning machine (CM1520; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological examination. Additionally, BALF cells were cytospun onto glass slides and stained with Diff-Quik for morphological analysis of alveolar macrophages.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and SAS 9.4. Differences between groups were analyzed using Student's t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For the comparative analysis of administration routes, percent inhibition rates were calculated as [(LPS − Treatment) / (LPS − Normal)] × 100 to quantify the relative efficacy of each treatment in reversing LPS-induced changes. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d with 95% confidence intervals to assess the magnitude of treatment effects compared to the LPS control group, where |d| = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Supplementary statistical analyses and data visualizations were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Orange 3 (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia). Heatmap visualization (

Figure S1) was generated to display inhibition rates across all markers and treatment groups. Radar charts (

Figure S2) were constructed to compare efficacy profiles between intranasal and oral administration routes. Forest plots (

Figure S3) were created to present effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals. Comparative bar charts (

Figure S4) and dose-response curves (

Figure S5) were generated to illustrate route-specific patterns and dose-dependent effects. Literature review data (

Table S1) were compiled from PubMed searches using the terms "PDRN," "polydeoxyribonucleotide," and "anti-inflammatory" to contextualize the current findings within existing PDRN research.

4. Discussion

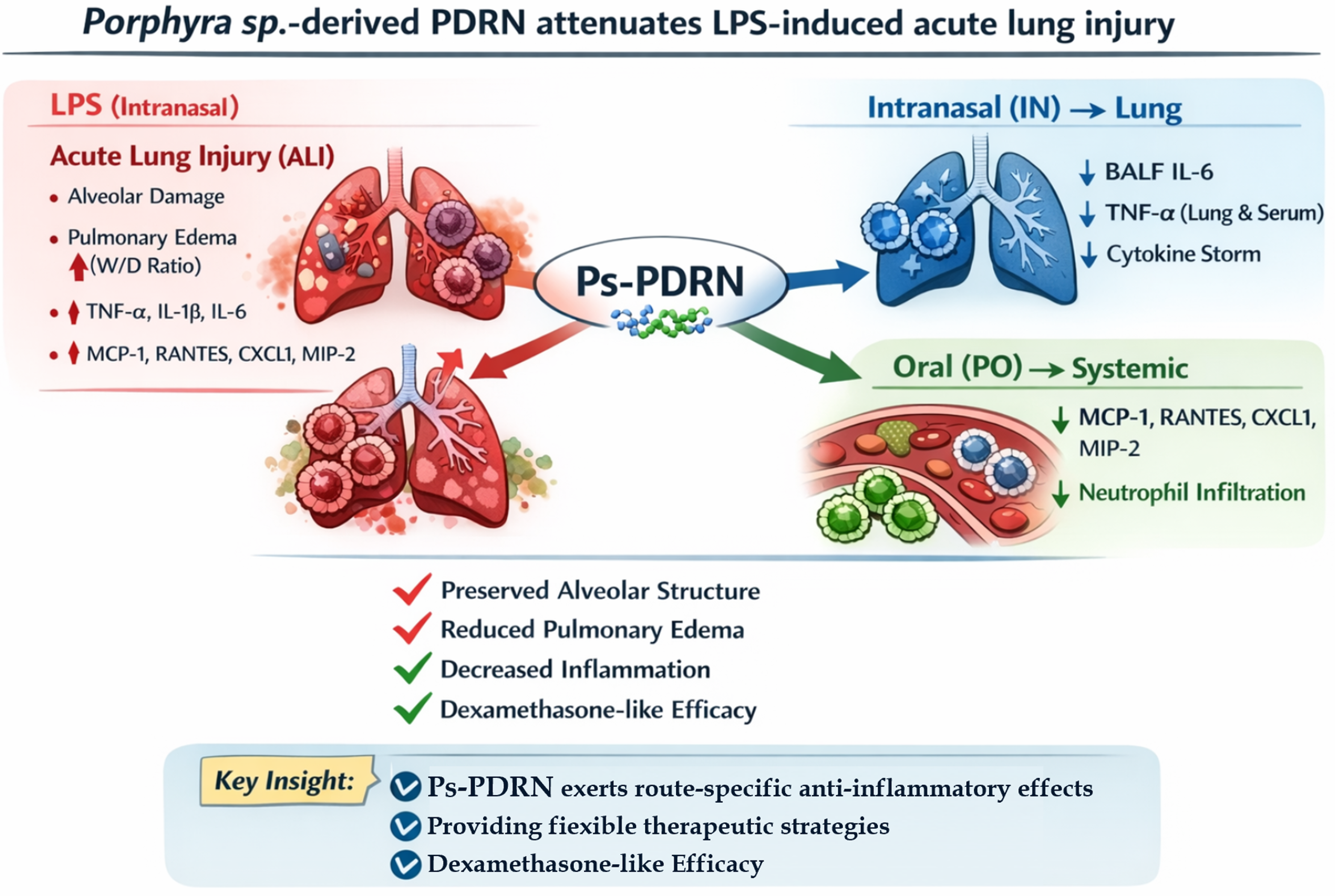

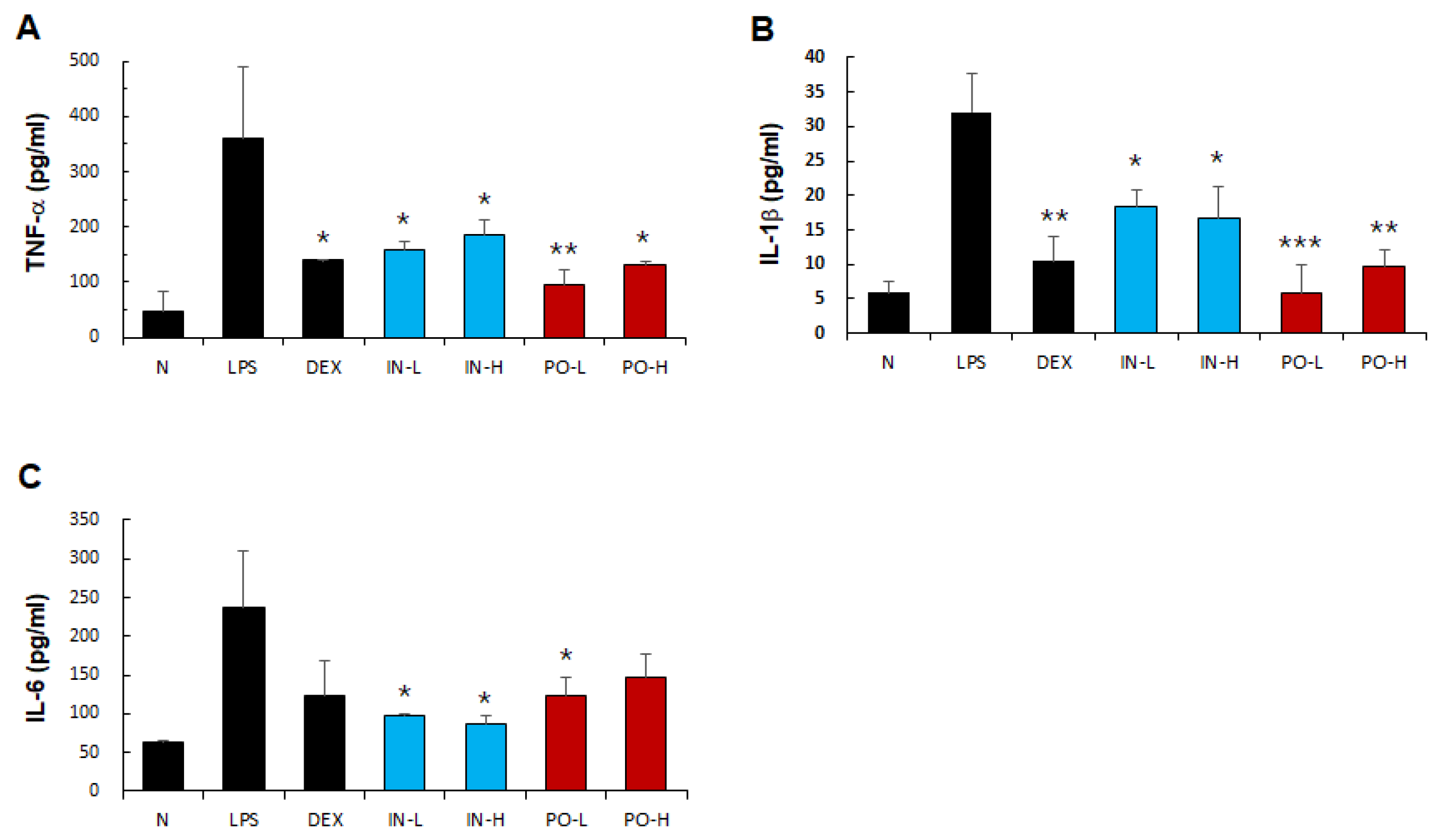

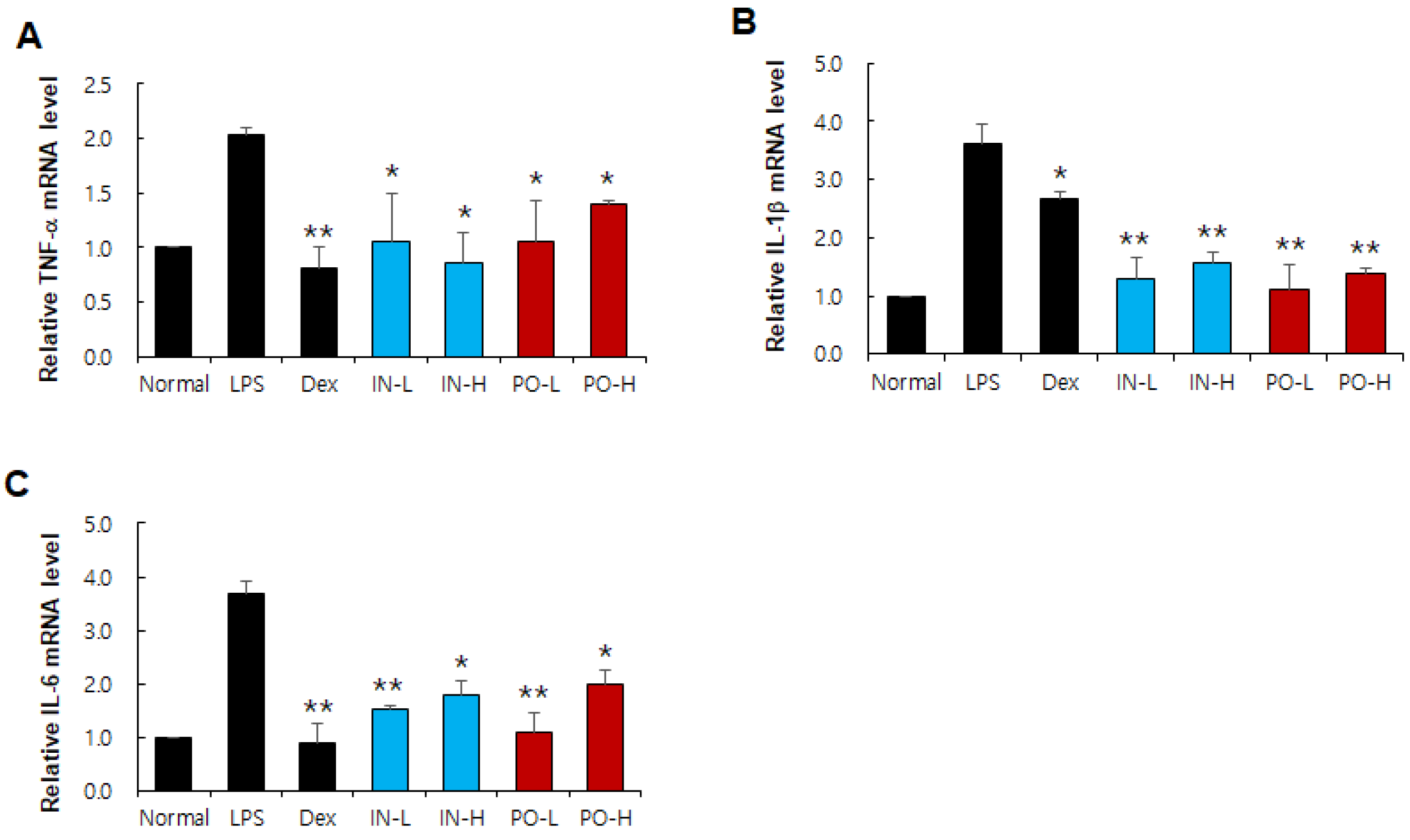

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that PDRN derived from

Porphyra sp. (Ps-PDRN) exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects against LPS-induced ALI in mice. Both intranasal and oral administration routes effectively attenuated systemic and pulmonary inflammation, suggesting versatile therapeutic applications of this marine-derived bioactive compound. ALI is characterized by excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that orchestrate the inflammatory cascade leading to lung damage [

15,

16]. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are key mediators that initiate and amplify the inflammatory response in ALI [

17]. Our results showed that Ps-PDRN significantly reduced the levels of these cytokines in both BALF and serum, as well as their mRNA expression in lung tissues. These findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating the anti-inflammatory properties of salmon-derived PDRN [

18,

19], suggesting that PDRN from different marine sources shares similar therapeutic mechanisms.

A comprehensive review of PDRN studies from various sources reveals that most investigations have utilized salmon-derived PDRN with molecular weights of 50–1,500 kDa, primarily administered via injection routes (

Supplementary Table S2). These studies have demonstrated consistent anti-inflammatory effects through adenosine A₂A receptor activation across diverse disease models, including wound healing, arthritis, and neurological injuries [

8,

9,

10,

11,

18,

19]. In particular, this study is the first to investigate PDRN derived from Porphyra sp., a sustainable marine algae resource other than salmon, and the first to compare intranasal and oral routes of administration of Ps-PDRN in an acute lung injury (ALI) model. The broader molecular weight range of Ps-PDRN (5–1,000 kDa) compared to conventional salmon-derived PDRN may contribute to its distinct pharmacokinetic properties and route-specific efficacy profiles observed in this study.

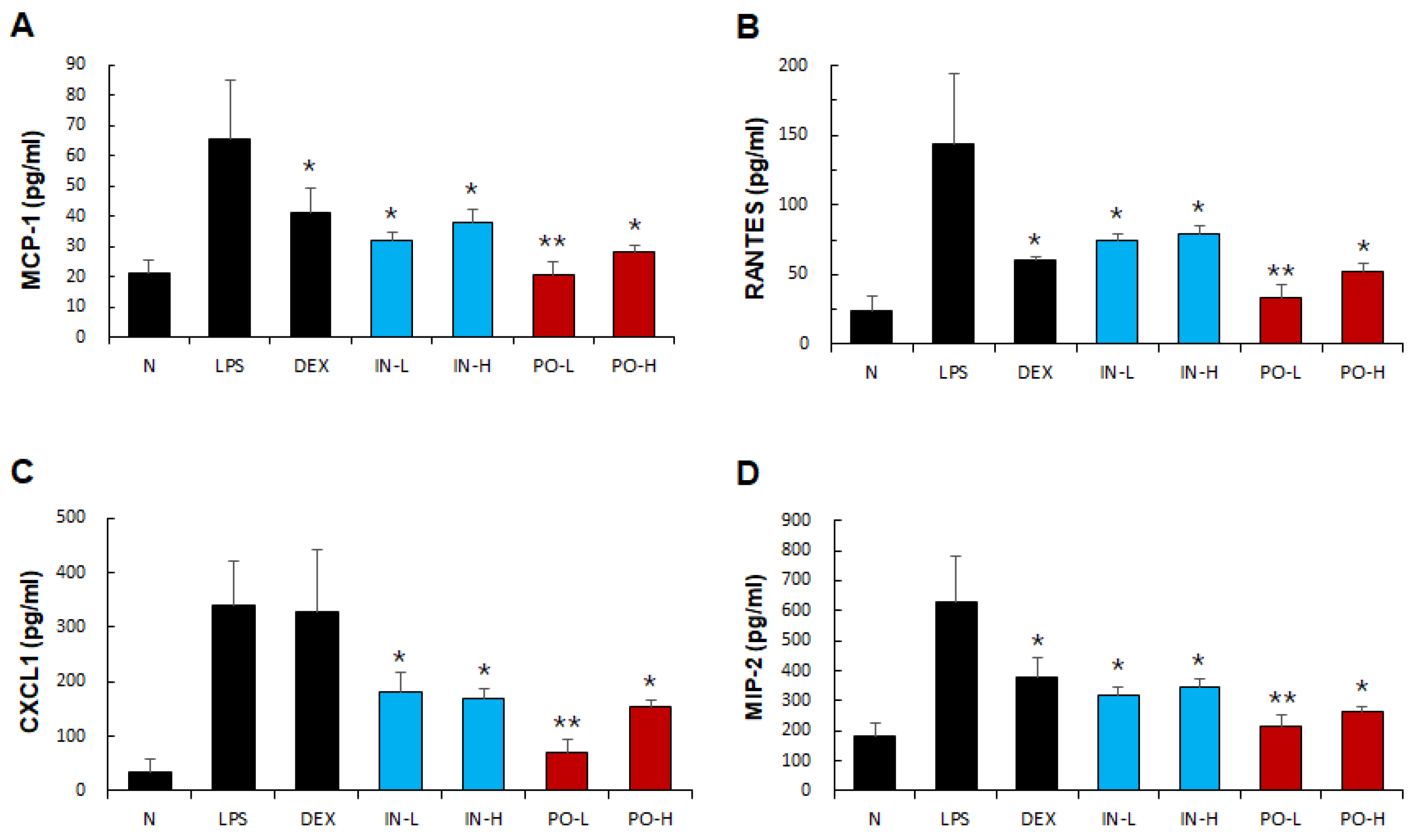

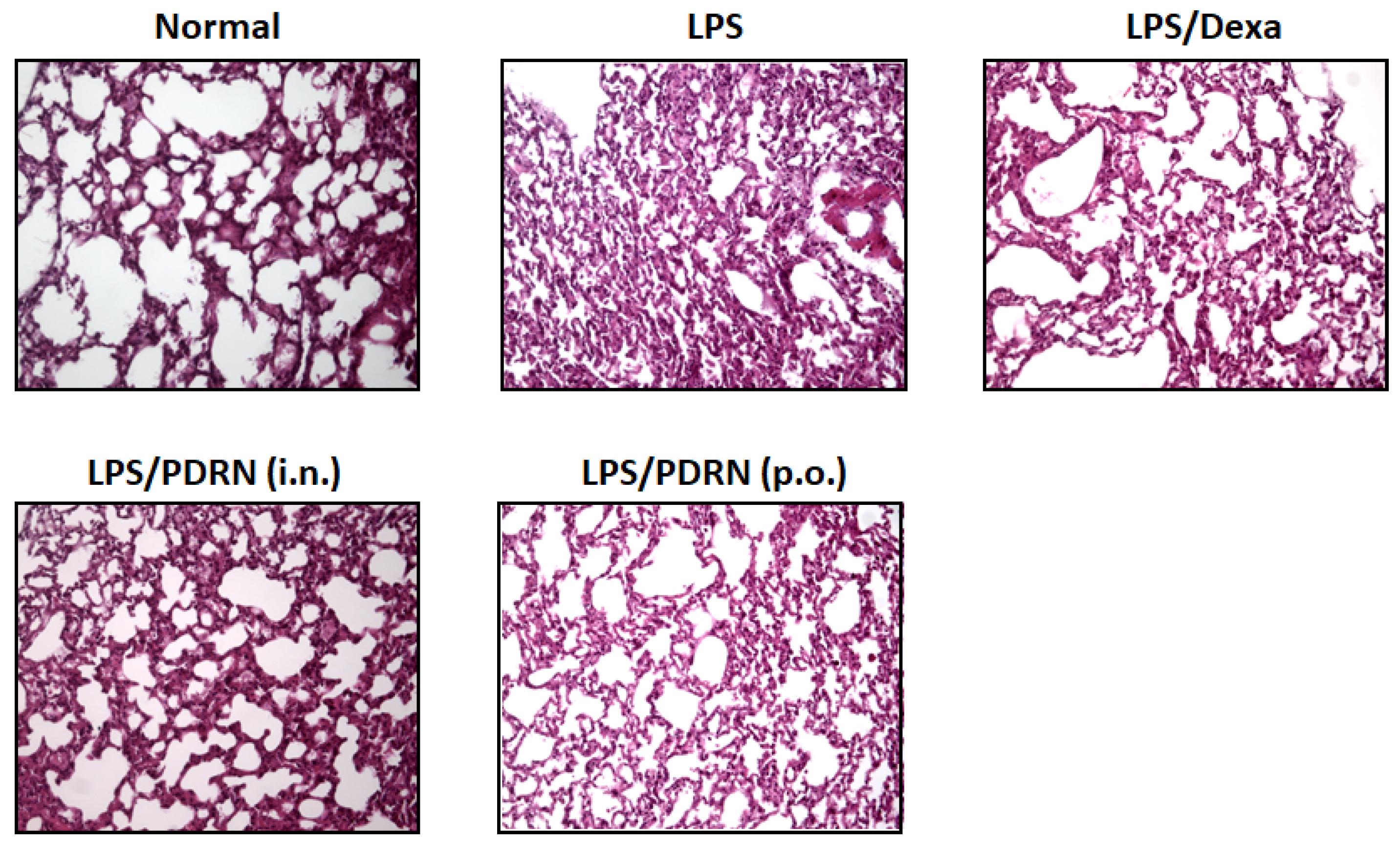

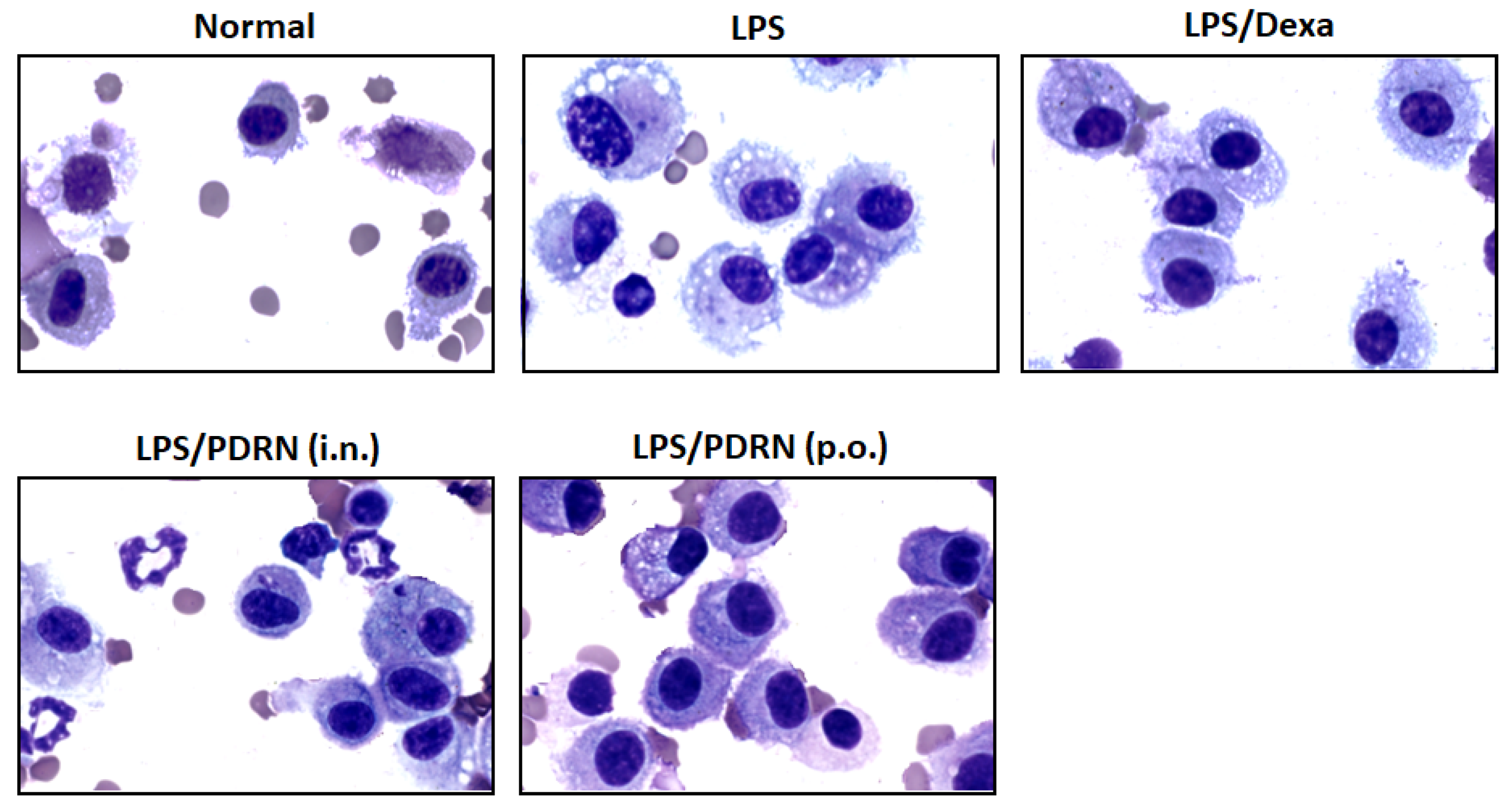

Chemokines, including not only CC chemokines (MCP-1 and RANTES) but also CXC chemokine (CXCL1 and MIP-2), play crucial roles in recruiting neutrophils and monocytes to the inflamed lungs [

20,

21]. Excessive neutrophil infiltration is a hallmark of ALI pathogenesis, contributing to tissue damage through the release of reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes [

22]. In our study, Ps-PDRN markedly suppressed the production of these chemokines, which correlated with reduced inflammatory cell infiltration observed in histological analysis. This suggests that Ps-PDRN may protect against ALI by limiting the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lungs.

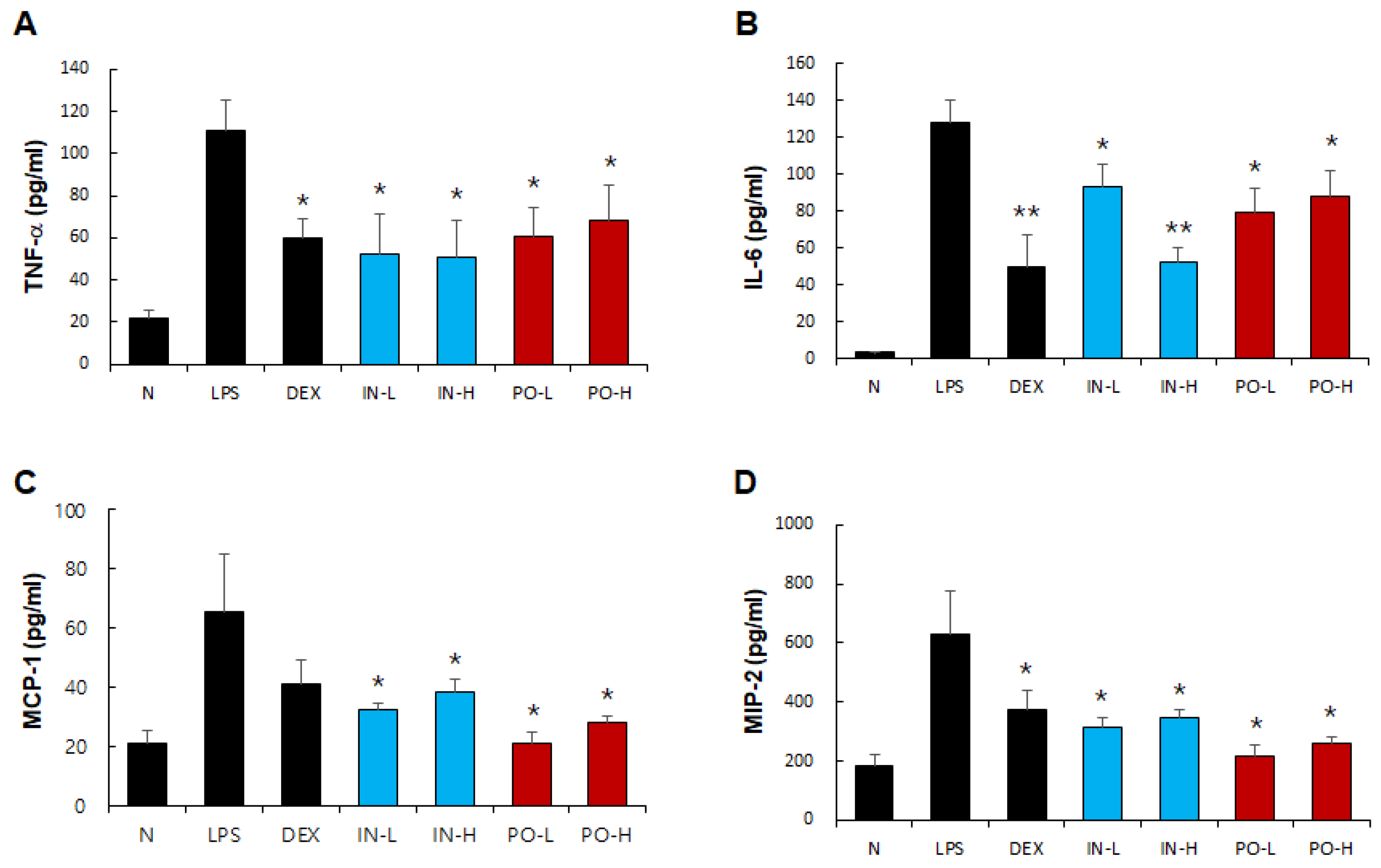

A notable finding of our study is the distinct efficacy profiles observed between intranasal and oral administration routes (Supplementary

Figures S1–S4). Comprehensive comparative analysis revealed that oral administration achieved superior overall inhibition (71.8%) compared to intranasal administration (60.7%), with particularly pronounced differences in chemokine suppression. Oral Ps-PDRN demonstrated remarkable efficacy in inhibiting MCP-1 (92.0% vs. 68.2%), RANTES (81.3% vs. 58.7%), CXCL1 (75.0% vs. 54.8%), and MIP-2 (88.9% vs. 66.7%) in BALF. Conversely, intranasal delivery showed advantages in suppressing certain cytokines, including BALF IL-6 (83.3% vs. 59.7%) and serum TNF-α (67.0% vs. 51.1%) (

Supplementary Figure S2). These distinct profiles suggest that the two administration routes may target different aspects of the inflammatory cascade, with oral delivery more effectively suppressing chemokine-mediated immune cell recruitment while intranasal administration preferentially affects local cytokine production. Interestingly, the dose-response analysis revealed unexpected patterns, particularly for oral administration. The PO-L group (100 μg/mouse) often showed comparable or superior efficacy to the PO-H group (200 μg/mouse), suggesting a potential therapeutic window beyond which additional dosing may not confer proportional benefits. This phenomenon was most evident for MCP-1 and MIP-2, where PO-L achieved near-complete inhibition (100% and 97.8%, respectively). Such findings have important implications for clinical dose optimization and suggest that lower oral doses may be sufficient for therapeutic efficacy.

Effect size analysis (Cohen's d) further quantified the magnitude of Ps-PDRN treatment effects across different markers and administration routes (

Supplementary Figure S3). All treatment groups demonstrated large effect sizes (|d| > 0.8) for most inflammatory markers, confirming the robust anti-inflammatory activity of Ps-PDRN. The forest plot visualization revealed that oral administration consistently achieved larger effect sizes for chemokines, while intranasal administration showed more pronounced effects on certain cytokines, supporting the concept of route-specific therapeutic profiles.

Intranasal delivery offers the advantage of local drug deposition directly to the respiratory tract, potentially providing faster onset of action and higher local drug concentrations [

23]. In contrast, oral administration is more convenient and suitable for chronic management. Our results suggest that Ps-PDRN can effectively reach the lungs and exert anti-inflammatory effects through both routes, offering flexibility in therapeutic applications. The route-specific efficacy profiles may guide clinical decision-making: intranasal administration may be preferred when rapid local cytokine suppression is desired, while oral administration may be advantageous for targeting chemokine-mediated inflammatory cell recruitment.

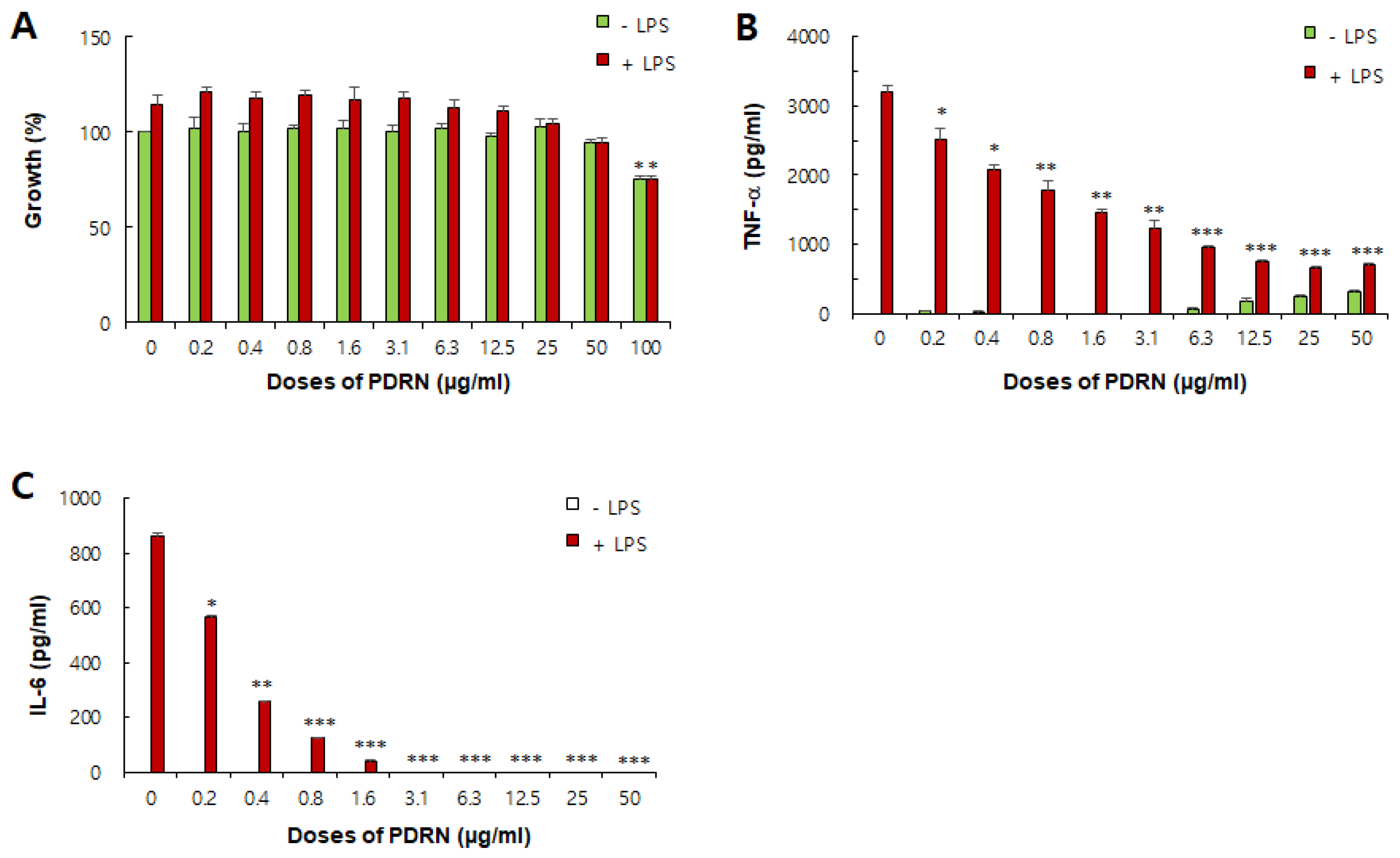

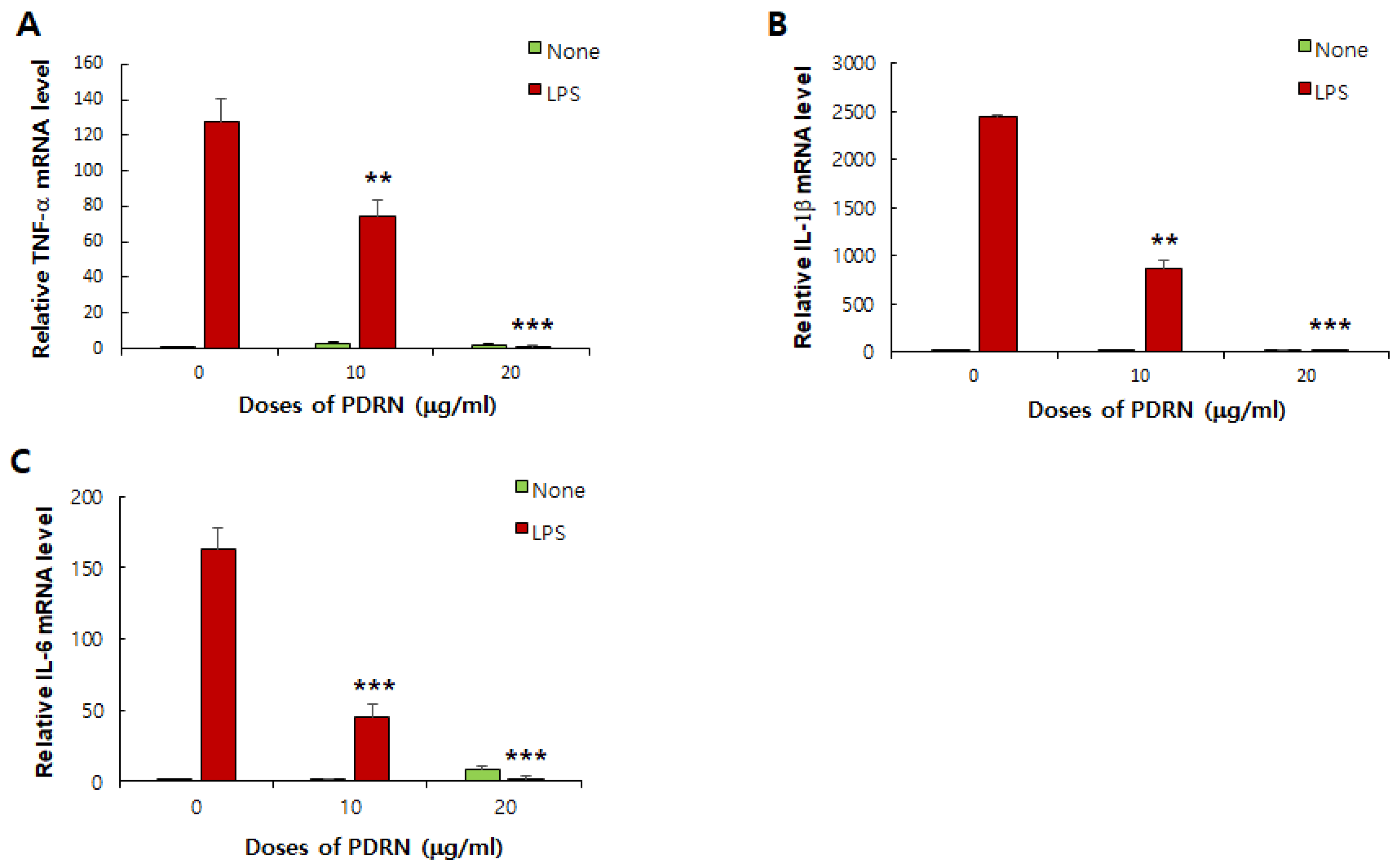

The

in vitro experiments using RAW 264.7 macrophages confirmed the direct anti-inflammatory activity of Ps-PDRN to inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production. Macrophages play a key role in the initiation and resolution of inflammation through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in acute lung injury (ALI) [

24]. Our results demonstrated that Ps-PDRN dose-dependently inhibited LPS-induced production of TNF-α and IL-6 proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages without significant cytotoxicity. Furthermore, real-time PCR analysis revealed that Ps-PDRN suppressed the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, indicating that the anti-inflammatory effects occur at the transcriptional level.

The anti-inflammatory mechanisms of PDRN have been attributed primarily to activation of adenosine A

2A receptors, which triggers intracellular signaling pathways that suppress the production of pro-inflammatory mediators [

25,

26]. Previous studies have shown that salmon-derived PDRN inhibits NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in various cell types [

27,

28]. Although we did not investigate the molecular mechanisms in the present study, it is reasonable to speculate that Ps-PDRN may exert its anti-inflammatory effects through similar signaling pathways. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of Ps-PDRN.

Porphyra sp. represents a sustainable and abundant marine resource for PDRN production. Unlike salmon-derived PDRN, which requires animal-sourced raw materials,

Porphyra sp. can be sustainably cultivated and harvested without concerns about resource depletion [

29]. Additionally,

Porphyra sp. has a long history of safe consumption as a traditional food in Asian countries, suggesting a favorable safety profile for therapeutic applications [

30]. These advantages make

Porphyra sp.-derived PDRN an attractive alternative to conventional PDRN sources.

There are several limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. First, we did not investigate the specific molecular mechanisms by which Ps-PDRN exerts its anti-inflammatory effects, including A2A receptor activation and downstream signaling pathways. Second, the study focused on a prevention model where Ps-PDRN was administered before LPS challenge; therapeutic efficacy in an established ALI model remains to be determined. Third, long-term safety and pharmacokinetic profiles of Ps-PDRN require further investigation. Despite these limitations, our findings, supported by comprehensive comparative analysis of administration routes, provide strong evidence for the therapeutic potential of Ps-PDRN in inflammatory lung diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-C.Y.; Methodology, G.-Y.L.; Y.-C.Y.; Investigation, G.-Y.L.; Validation, Y.-C.Y.; Formal analysis, Y.-C.Y.; Resources, J.-S.H.; W.S.L.; Data curation, G.-Y.L.; Y.-C.Y.; W.S.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.-C.Y.; Writing—review and editing, G.-Y.L.; Y.-C.Y.; Visualization, Y.-C.Y.; Supervision, Y.-C.Y.; Project administration, Y.-C.Y.; Funding acquisition, Y.-C.Y.; J.-S.H.

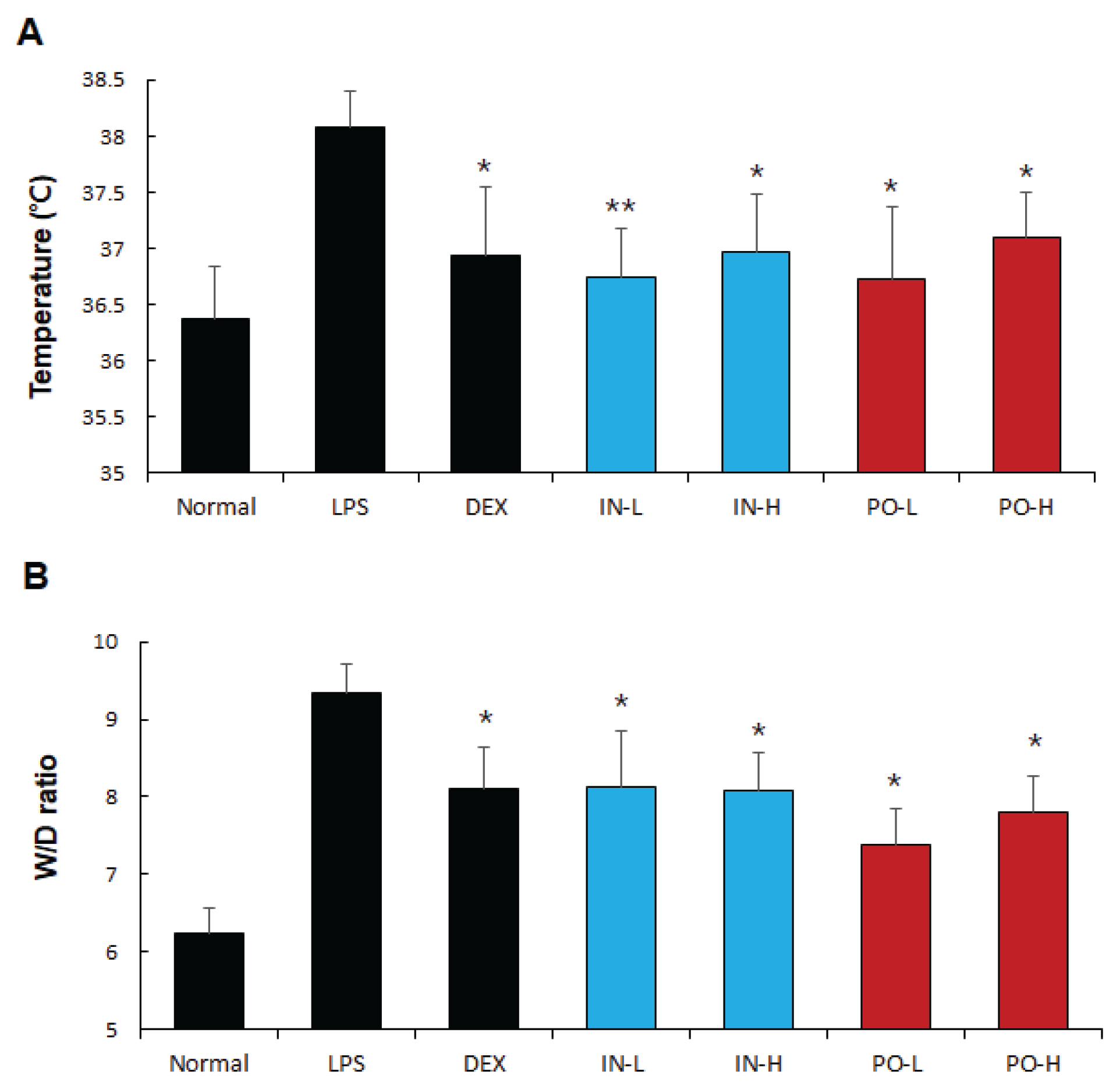

Figure 1.

Ps-PDRN attenuates LPS-induced fever and pulmonary edema. (A) Body temperature; (B) Lung wet/dry (W/D) ratio. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 1.

Ps-PDRN attenuates LPS-induced fever and pulmonary edema. (A) Body temperature; (B) Lung wet/dry (W/D) ratio. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 2.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in BALF. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Figure 2.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in BALF. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Effects of Ps-PDRN on cytokine mRNA expression in lung tissues. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Effects of Ps-PDRN on cytokine mRNA expression in lung tissues. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 4.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on chemokine levels in BALF. (A) MCP-1; (B) RANTES; (C) CXCL1; (D) MIP-2. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 4.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on chemokine levels in BALF. (A) MCP-1; (B) RANTES; (C) CXCL1; (D) MIP-2. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 5.

Histopathological analysis of lung tissues (H&E staining). Representative images showing: Normal control with intact alveolar structure; LPS group with severe inflammatory infiltration and alveolar damage; Dexamethasone (DEX) group with reduced inflammation; Ps-PDRN (IN, 50 μg/mouse) and Ps-PDRN (PO, 200 μg/mouse) groups showing preserved alveolar architecture and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration.

Figure 5.

Histopathological analysis of lung tissues (H&E staining). Representative images showing: Normal control with intact alveolar structure; LPS group with severe inflammatory infiltration and alveolar damage; Dexamethasone (DEX) group with reduced inflammation; Ps-PDRN (IN, 50 μg/mouse) and Ps-PDRN (PO, 200 μg/mouse) groups showing preserved alveolar architecture and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration.

Figure 6.

Morphological analysis of alveolar macrophages in BALF. Representative images of Diff-Quik stained BALF cells showing macrophage activation status in Normal, LPS, Dexamethasone (DEX), Ps-PDRN (IN), and Ps-PDRN (PO) groups.

Figure 6.

Morphological analysis of alveolar macrophages in BALF. Representative images of Diff-Quik stained BALF cells showing macrophage activation status in Normal, LPS, Dexamethasone (DEX), Ps-PDRN (IN), and Ps-PDRN (PO) groups.

Figure 7.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on serum cytokine and chemokine levels. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-6; (C) MCP-1; (D) MIP-2. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 7.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on serum cytokine and chemokine levels. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-6; (C) MCP-1; (D) MIP-2. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

Figure 8.

In vitro effects of Ps-PDRN on RAW 264.7 macrophages. (A) Cell viability assessed by MTT assay; (B) TNF-α production; (C) IL-6 production. Cells were pretreated with Ps-PDRN for 12 h and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Figure 8.

In vitro effects of Ps-PDRN on RAW 264.7 macrophages. (A) Cell viability assessed by MTT assay; (B) TNF-α production; (C) IL-6 production. Cells were pretreated with Ps-PDRN for 12 h and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Figure 9.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on cytokine mRNA expression in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Figure 9.

Effects of Ps-PDRN on cytokine mRNA expression in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-6. mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

| Gene |

Primer Sequence (5′→3′) |

Accession No. |

Catalog No. |

| TNF-α |

F: GGTGCCTATGTCTCAGCCTCTT

R: GCCATAGAACTGATGAGAGGGAG |

NM_013693 |

MP217748 |

| IL-1β |

F: TGGACCTTCCAGGATGAGGACA

R: GTTCATCTCGGAGCCTGTAGTG |

NM_008361 |

MP206724 |

| IL-6 |

F: TACCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGC

R: CTGCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTC |

NM_031168 |

MP206798 |

| GAPDH |

F: CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG

R: ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG |

NM_008084 |

MP205604 |