1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent deficits in reciprocal social communication and interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities [

1]. The prevalence of ASD has been reported to be 2.76% among 8-year-old children in the United States [

2] and 3.22% among 5-year-old children in Japan [

3], highlighting the importance of providing appropriate support for individuals with ASD in Japan.

According to the 2021 White Paper on Occupational Therapy [

4], developmental disorders such as ASD account for 58.6% of all paediatric occupational therapy (OT) cases in Japan. As part of interventions for children and individuals with ASD, occupational therapists (OTRs) often provide sensory integration therapy (SIT).

SIT, developed by American occupational therapist A. Jean Ayres, is an OT approach that is used to assess and treat children’s learning, behavioural, emotional, and social development from the perspective of sensory integration in the brain (sensory integration theory). This theory is based on the hypothesis that the brain’s ability to process sensory information influences learning and behavioural performance [

5]. In Japan, SIT is frequently used in OT practice for children with ASD.

Regarding the effectiveness of SIT, the American Academy of Paediatrics has reported a critical lack of scientific evidence supporting its efficacy [

6]. Novak et al. classified SIT for ASD as ‘not recommended’ [

7], and systematic reviews have indicated that high-quality studies such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are limited to fewer than three publications [

8,

9]. In response to these critiques, several RCTs have since been conducted [

10,

11,

12], advancing the evidence base for SIT in children with ASD. More recent systematic reviews have reported improvements in multiple domains, including motor, cognitive, social, and communication skills, as well as in daily functioning and quality of life [

13].

However, previous studies have been primarily focused on children with ASD without intellectual disability (ID) or did not account for ID status in participant selection [

13]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have specifically targeted children with ASD and co-occurring ID.

ID is a developmental disorder characterized by deficits in both intellectual and adaptive functioning across conceptual, social, and practical domains [

1]. The comorbidity rate of ID among children with ASD has been reported as 37.9% in the United States [

2] and 36.8% in Japan [

3]. Children with ASD and co-occurring ID exhibit greater challenges and impairments across a wide range of behaviours and skills compared with those who have either [

14], making early intervention essential.

Although SIT has previously been reported to be provided at least twice per week [

13], in clinical practice in Japan, it is offered not more than once per week [

15]. The frequency of occupational therapy sessions in Japan is restricted by the medical insurance system, child disability support system, systemic reimbursement limitations, and a shortage of specialists [

4,

16], resulting in sessions typically being provided less than once per week. However, the effectiveness of SIT provided less frequently than once per week, reflecting actual practice conditions in Japan, remains uninvestigated.

Therefore, we employed a single-group pre–post design involving children with ASD and co-occurring ID, with two aims: 1) as a preliminary investigation toward a future two-group comparison, to examine the feasibility of implementing SIT in Japanese clinical settings, and 2) to explore the potential for change associated with once-weekly SIT, consistent with the typical frequency of clinical practice in Japan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted at the Nishinomiya City Child and Family Center Clinic, a core medical and developmental support facility located in Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, which has a population of approximately 480,000. The Center provides medical and rehabilitation services for children under 18 years of age residing in Nishinomiya City. Its multidisciplinary team, comprising physicians, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech language hearing therapists, and psychotherapists, provides medical care and developmental rehabilitation for children and families facing physical or mental developmental challenges.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Committee on Research Ethics, Graduate School of Comprehensive Rehabilitation, Osaka Prefecture University (Approval No. 2021-217) on March 30, 2022. The study was conducted as a preliminary investigation prior to a planned non-randomised controlled trial on the therapeutic effects of SIT (scheduled study period: March 30, 2022, to March 31, 2027). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participating children after providing both oral and written explanations of the study. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. The preliminary study was carried out between May 2023 and May 2024. Following ethical approval, coordination with the study site required additional time to address issues such as ensuring fairness between clients on the facility’s waiting list and those currently receiving services, as well as confirming the practical feasibility of implementation.

Consequently, it was determined that public registration of the clinical trial should take place after these issues had been resolved. Therefore, registration with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) was completed after conducting this feasibility-focused preliminary study (UMIN000059427). Committee on Research Ethics The Graduate School of Comprehensive Rehabilitation Osaka Prefecture University

2.2. Participants

Participants were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) Diagnosis of ASD by a paediatrician at the Nishinomiya City Child and Family Center Clinic based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).

2) Age between 2 years 0 months and 6 years 9 months of age. The study included only children who would remain preschool-aged throughout the treatment and assessment period.

3) ASD severity classified as severe (≥37 points) using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Second Edition – Standard Version (CARS2-ST).

4) Developmental Quotient (DQ) of ≤70. Because it is often difficult to administer intelligence tests to children with ASD and co-occurring ID, DQ was used as an index of intellectual ability.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) presence of an evident physical disability such as cerebral palsy; 2) medical conditions such as epilepsy or heart disease that contraindicate physical activity; 3) current or past receipt of SIT provided by an occupational therapist; and 4) difficult family circumstances (e.g., child abuse or parental illness, etc.).

2.3. Procedures

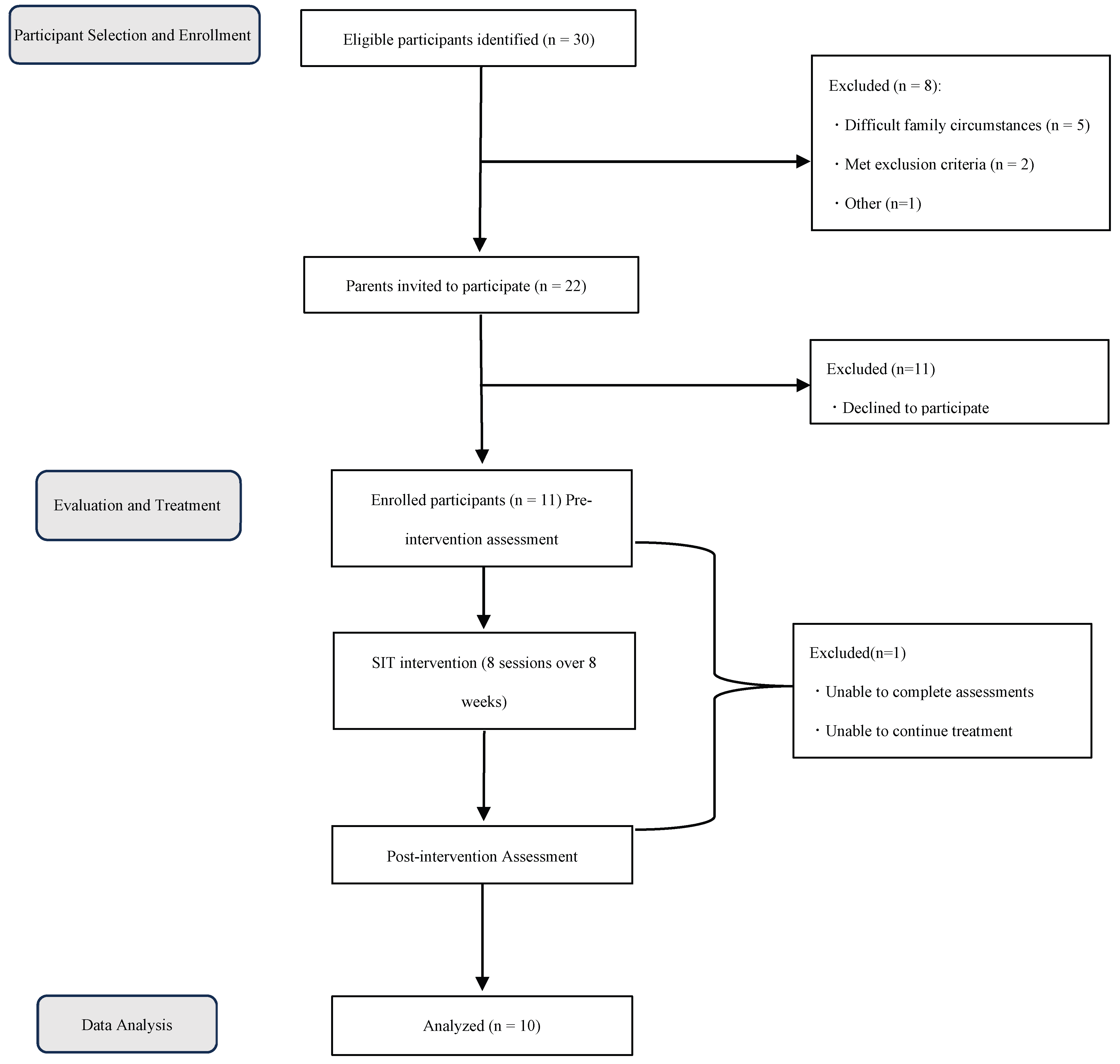

Figure 1 presents the study procedure and study population size. For participant selection, information was collected from medical records and from professionals involved in each child’s care, including paediatricians, speech language hearing therapists (STs), and nursery teachers. Initial observations were also conducted during the first OT session for evaluation purposes. Based on this information, parents or guardians of children who met the eligibility criteria were approached for recruitment. For those whose guardians consented to participate, the responsible OTR conducted pre-treatment assessments and measurements in consultation with a paediatrician and an ST. These assessments incorporated information obtained during participant selection, as well as additional data collected through parental interviews and questionnaires.

The frequency of SIT was set at once per week, reflecting actual clinical practice in Japan [

15]. The treatment period and session length were established at 8 weeks (eight sessions in total) of 40 min each, based on previous SIT studies [

17,

18,

19]. This schedule was chosen to ensure equitable treatment for users at the facilities participating in the study.

Following intervention completion, post-treatment assessments and measurements were conducted through parental interviews and questionnaires.

As the therapist served as both the SIT implementer and evaluator, this aspect of the study was not blinded.

2.4. Assessment of feasibility

Throughout the study, from recruitment to completion of assessment and treatment, the evaluator documented all processes in the medical records and the Center’s internal database. During recruitment, information obtained in advance from paediatricians, STs, and nursery teachers was recorded, along with the number of eligible children, the number of those who did not provide consent, and the reasons for non-participation. For the assessment and treatment phases, the dates and details of each session were documented to monitor study progress.

2.5. Sensory Integration Therapy

SIT was conducted by an occupational therapist with 17 years of clinical experience who held certification as a registered therapist (No. 141) from the Japanese Society for Sensory Integration. This certification is awarded to professionals in Japan who complete specialised training in the assessment and intervention methods of SIT and are accredited by the society [

20]. The intervention took place in a sensory integration room within the clinic used by OTRs, equipped with essential apparatus for SIT, including a trampoline, swing, and ball pool.

In implementing the intervention, the Ayres Sensory Integration Fidelity Measure (ASIFM) [

21], a scale developed to ensure that occupational therapists deliver SIT in accordance with the principles established by Ayres, was used as a reference.

Given the characteristics of the study participants, namely children with ASD and co-occurring ID who exhibited various behavioural difficulties [

14] and were classified as having severe ASD according to the CARS2, the intervention emphasised one of the core principles of SIT: establishing a therapeutic relationship with the child. This focus is closely related to a key characteristic of ASD, namely impaired social communication. During treatment sessions, particular attention was paid to creating opportunities for eye contact and for expressing positive emotional responses through vocal and facial interactions between the therapist and the child.

For each child, an individualized treatment plan was also developed by formulating hypotheses based on sensory integration theory to interpret the underlying causes of specific functional difficulties. For instance, if a child experiences difficulty using eating utensils, this is interpreted as a challenge in understanding the characteristics and proper use of tools. During treatment, support was provided to help the child develop their own approach in using tools through activities such as guided practice with play equipment.

As the intervention progressed, the child’s responses during sessions were reviewed, and both the treatment content and evaluations were adjusted as needed based on written records and video reviews.

2.6. Tools Used for Participant Selection

For participant selection, the CARS2-ST was administered, and the results of the KSPD were reviewed.

The CARS2-ST is a revised version of the original CARS, developed to differentiate children with ASD from those with other developmental disorders. It is a scale used to diagnose ASD, differentiate it from other disorders, and further classify the diagnosed disease as mild, moderate, mild-to-moderate or severe.

The items incorporate the core features of autism described by Kanner, additional characteristics identified by Creak, and supplementary scales useful for evaluating symptoms in young children. The measure has also been validated as capturing the core symptoms described in previous editions of the DSM-5. To calculate the total score, scores below 30 are classified as non-ASD, scores from 30 to 36.5 are classified as mild-to-moderate ASD, and scores from 37 to 60 are classified as severe ASD [

22].

Ratings are based on observations made in various contexts, such as during psychological testing or at the child’s regular institution, along with reports from parents, comprehensive clinical records, or an integration of these sources.

In this study, assessments were conducted using clinical records, behavioural observations, and interviews with staff members at the Nishinomiya City Child and Family Center Clinic.

The KSPD is a standardised developmental assessment widely used in Japan [

23,

24]. It is most commonly employed during health checkups for infants and young children whose developmental stage makes it difficult to administer Wechsler-type intelligence tests [

25], and it is used in determining eligibility for the Ryoiku Techo (rehabilitation certificate) issued to children with ID.

This assessment evaluates three developmental domains. The Postural-Motor (P-M) domain evaluates motor function, the Cognitive-Adaptive (C-A) domain assesses cognitive abilities including nonverbal reasoning and visuospatial perception, while the Language-Social (L-S) domain examines communication encompassing interpersonal relationships, social skills, and language abilities. A developmental quotient (DQ) is calculated for each of these three domains and for an overall composite score [

26]. The DQ derived from the KSPD is considered a useful indicator for evaluating a child’s developmental level [

27].

In this study, the results of the KSPD previously administered at the Nishinomiya City Child and Family Center Clinic or at child guidance centres were reviewed.

2.7. Outcome Measures and Assessment Tools

Because OT emphasises the individuality of each child, ‘individualised treatment goals’ were included as a measurement item. As children with ASD and ID often exhibit a wide range of behavioural challenges and difficulties [

14], ‘behaviour’ was also selected. Furthermore, since children with ASD frequently experience sensory issues such as hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity in addition to their core characteristics [

1,

28], ‘sensation’ was included. Finally, as parents of children with ASD have been reported to experience significantly higher levels of child-rearing stress compared with parents of children with other disabilities or typically developing children [

29], ‘child-rearing stress’ was also assessed. Thus, four domains were measured: individualised treatment goals, behaviour, sensation, and child-rearing stress.

The corresponding assessment and measurement tools used for each are described below.

2.8. Outcome Measures

2.8.1. Evaluation of therapeutic goal attainment: Goal Attainment Scaling & Canadian Occupational Performance Measure

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) is a standardised evaluation method in which individualised rating scales are created for each client to measure the degree of goal achievement within their treatment program [

30]. It has demonstrated high reliability and responsiveness across a variety of contexts, including paediatrics and cognitive rehabilitation [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], and is also recommended for evaluating the effectiveness of OT and SIT interventions [

38].

In GAS, three to five treatment goals that are meaningful to the client are established based on information gathered from the client, family members, and professionals involved in the client’s care, such as those in medical, health, educational, or childcare settings. Each goal is rated on a five-point scale ranging from −2 to +2, where −1 represents the current performance level and 0 represents the expected level of achievement.

There are several methods for scoring GAS, but we used the method described by Gordon et al. [

33] in this study and calculated the modified GAS score. A T-score of 50 indicates that the expected outcome was achieved, scores above 50 indicate outcomes exceeding expectations, and scores below 50 indicate outcomes below expectations.

In this study, ‘goals meaningful to the client’ were identified using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). The content and gradation of each goal were determined collaboratively with two co-researchers who were OTRs with 10 or more years of clinical experience with ASD and co-occurring ID, as well as experience conducting outcome studies using GAS.

The COPM was developed to ensure the quality of occupational therapy by identifying activities that are meaningful to the client and tracking the client’s perception of performance in those activities over time. It is an individualised, client-centred outcome measure that has demonstrated high validity, reliability, usefulness, and responsiveness [

39,

40].

In this study, the COPM was used to identify activities meaningful to each client, determine their perceived importance, and incorporate this information into GAS.

2.8.2. Behavioural Assessment: Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II)

The VABS-II is an assessment tool used to evaluate adaptive behaviour and has demonstrated high validity and reliability. The Adaptive Behaviour Assessment is divided into four domains— communication, daily living skills, socialisation, and motor skills—each comprising two to three subdomains.

Composite and domain scores for adaptive behaviour are calculated as standard scores. Subdomain scores are expressed as v-scale scores (mean = 15, standard deviation [SD] = 3), which allow for detailed identification of low-level performance that significantly limit adaptive functioning in individuals with disabilities such as ASD or ID [

41].

The evaluation is conducted through semi-structured interviews with the parents of the children. To improve interview efficiency, a Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire is provided beforehand to gather preliminary information [

42].

In this study, the Adaptive Behaviour Assessment was administered to the parents of participating children. Because children with ASD and co-occurring ID often exhibit uneven developmental skills [

43,

44] and ASD-specific behavioural patterns that may not align well with standardised items, the semi-structured interviews required considerable time. Given these factors, securing sufficient time for interviews was expected to be difficult within the practical constraints of the research setting. Moreover, the Japanese version of the VABS-II does not include the Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire. Therefore, data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews supplemented with information obtained from other assessment and measurement tools. Additionally, to gather complementary information, individualised questionnaires were developed for each child and administered both before and after the intervention to support evaluation and measurement.

2.8.3. Sensory assessment: Short Sensory Profile

The SSP is a shortened form of the Sensory Profile (SP), developed to assess sensory processing abilities and their effect on daily functioning. This questionnaire enables rapid assessment in both clinical practice and research [

45].

Both the original and Japanese versions have been confirmed to have sufficient reliability and validity [

46].

The SSP consists of nine section scores and an overall total score that is particularly important for clearly identifying a child’s sensory processing abilities. When the total score falls within the ‘much higher than others’ range (mean +2 SD or above), it may indicate difficulty adapting to the environment and a potential for self-directed or outwardly disruptive behaviours. When the score falls within the ‘higher than others’ range (mean +1 SD to +2 SD), it may suggest that sensory processing difficulties are interfering with daily life.

2.8.4. Assessment of Child-Rearing Stress: Parenting Stress Index, Short Form

The Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) is a shortened version of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) [

47], a screening tool designed to identify parents who may be at risk of difficulties in child-rearing or who have children with developmental risks.

The Japanese version of the PSI-SF consists of 19 items with a two-factor structure: ‘Child Domain’ and ‘Parent Domain’. The Child Domain comprises nine items, such as ‘My child is so active that it tires me’ and ‘My child has less concentration than other children’. The Parent Domain consists of ten items, such as ‘I enjoy being a parent’ and ‘I often feel that I cannot handle things well’. The Japanese version has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity [

48].

2.9. Statistical analysis

The effectiveness of SIT was examined using the following measures: therapeutic goal attainment was evaluated using GAS, behavioural changes using the VABS-II, sensory processing abilities using the SSP, and changes in child-rearing stress using the PSI-SF.

The Shapiro–Wilk test was first performed to assess normality. As some variables, including GAS and VABS-II, were not normally distributed, pre- and post-intervention differences were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The level of significance was set at p < .05 (two-tailed). In accordance with the properties of the Wilcoxon test, cases with a difference of zero were automatically excluded from the analysis. In this study, the effective sample size for the Wilcoxon test ranged from 7 to 10. The effect size (r) was calculated based on the total sample size (n = 10), and confidence intervals were calculated accordingly. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.1.0 (142).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

From the screening process, 30 children met the eligibility criteria. Based on information obtained in advance from staff members and medical records, eight children were excluded for the following reasons: difficult family circumstances such as abuse or parental illness (n = 5), meeting exclusion criteria (n = 2), or other reasons (n = 1). Participation was subsequently offered to 22 children, of whom 11 provided consent, while the remaining 11 declined due to difficulty attending weekly sessions. Among the 11 children who received SIT, one was unable to complete the pre- and post-intervention assessments; therefore, data from 10 participants were included in the analysis.

Among the 10 participants who completed both assessments, DQ scores indicated mild delay (70–51) in nine children and moderate delay (50–36) in one child; no participants were classified within the severe (35–21) or profound (20 or below) ranges. The mean CARS2 score was 39.6±1.7, with all participants classified as having severe ASD. Based on pre-intervention VABS-II results, the mean composite adaptive behaviour score was 52.9 ± 9.8, corresponding to below −2 SD. Among the four domains, the lowest scores were observed in socialisation (

Table 1).

No changes were planned in the children’s affiliations or individual ryoiku programmes during the intervention period.

3.2. Outcome Measure

3.2.1. Evaluation of Goal Attainment: GAS

Three to four goals were set for each participant, and GAS T-scores were calculated before and after the intervention (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Table 2 presents a summary of the GAS and COPM goals formulated based on the primary concerns of the parents, while

Table 3 provides specific examples for each goal category.

Table 4 illustrates an example of GAS implementation and scoring.

The mean post-intervention GAS T-score was 61.2, exceeding the expected outcome criterion of 50 for all participants. A significant difference was observed between pre- and post-intervention GAS T-scores (p = .005). The effect size corresponded to a large effect size (r = 0.88), with the confidence interval ranging from small (r = 0.1–0.3) to large. (

Table 5)

3.2.2. Behavioural Assessment: VABS-II

The composite adaptive behaviour score showed a significant difference between pre- and post-intervention (p = 0.005), with a large effect size (r = 0.88). The 95% confidence interval ranged from small to large.

Significant differences were observed in the domains of communication (p = 0.012), activities of daily living (p = 0.017), and socialisation (p = 0.005), all with large effect sizes. The 95% confidence intervals for these domains ranged from small to large.

At the subdomain level, significant improvements were noted in receptive language (p = 0.007), expressive language (p = 0.014), and coping skills (p = 0.010), each showing a large effect size. The 95% confidence intervals ranged from small to large, except for reading and writing, which included a range below small.

Although a significant difference was observed for reading and writing (p = 0.035), the v-scale score decreased slightly, while the raw score did not decline. (

Table 5)

3.2.3. Sensory Assessment: SSP

No significant difference was observed in the total score (p = 0.125). Regarding changes in score classification, one participant’s result shifted from ‘much higher than average’ to ‘higher than average’, whereas three participants’ results shifted from ‘higher than average’ to ‘much higher than average’, and one shifted from ‘average’ to ‘higher than average’. Overall, more participants showed an increase in sensory regulation difficulties. Among the five participants whose scores did not change, all were classified as ‘higher than average’. (

Table 5)

3.2.4. Parental Stress Assessment: PSI-SF

No significant difference was observed in the total score (p = 0.362). The mean percentile rank was approximately 87 before the intervention and 88 after, indicating little to no change. (

Table 5)

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility Considerations

The aim of this study was to ① examine the feasibility of implementing SIT in clinical settings in Japan, and ② explore the potential for change associated with once-weekly SIT based on outcome measures.

A total of 11 children met the eligibility criteria and were recruited, with 10 ultimately participating. All 10 participants successfully completed the entire process, including pre- and post-intervention assessments and the intervention itself. Although the time commitment may have posed some burden, the study design was determined to be feasible.

Regarding participant characteristics, based on DQ classification, nine of the ten children were categorised as having mild ID and one as having moderate ID. Previous studies have shown that approximately 85% of individuals with ID fall within the mild range and about 10% within the moderate range [

49,

50]. Thus, the distribution observed in this study was broadly consistent with these proportions. Although the absence of participants with severe or profound ID represents a limitation, the overall distribution was considered reasonable and comparable to typical population data.

The once-weekly frequency of SIT in this study was lower than that used in previous research and might have been expected to produce limited changes. Nevertheless, several outcome measures demonstrated statistically significant improvements. However, because participants were also receiving regular ryoiku (

Table 1), these effects may have been influenced by concurrent interventions. Therefore, the results of each outcome measure are discussed below in relation to sensory integration theory, referencing prior research on SIT for children with ASD and co-occurring ID.

4.2. Considerations Regarding the Attainment of Individual Treatment Goals

The results of this study, consistent with previous findings [

51,

52], showed positive changes.

Among the major goal categories (

Table 1), ‘communication’ was the most frequent, accounting for approximately 54% of all GAS goals. These goals were primarily related to the core features of ASD; deficits in social communication and restricted; and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities, which influence relationships with others and participation in group settings. Thus, they were likely to reflect parents’ primary concerns and become central treatment goals.

The second most frequent category, ‘activities of daily living (ADL)’, comprised approximately 19% of all GAS goals. These goals involved unacquired daily functional skills, which were considered to be influenced mainly by adaptive function impairments associated with ID.

However, the confidence interval for the effect size ranged from small to large, indicating a relatively high degree of uncertainty in the results. Furthermore, the GAS T-score may have been influenced by measurement bias due to the therapist and evaluator being the same person and the assessment method being family-participatory, potentially leading to results being overestimated compared to actual change.

4.3. Considerations Regarding Behaviour

VABS-II results showed significant improvements in the domains of communication, daily living skills, and socialisation, as well as in the subdomains of receptive language, expressive language, and coping skills. These significant domains were consistent with findings from previous research [

53]. The decline in subdomain v scores for reading and writing reflected a widening gap relative to peer norms rather than a decrease in raw scores. This pattern, where standardized scores decline due to slower developmental progress compared with peers, is consistent with previous findings in children with neurodevelopmental disorders [

54].

Regarding participant characteristics associated with the domains showing significant differences, improvements in ‘communication’ and ‘socialisation’ likely reflected changes in social communication abilities, particularly in language-related aspects, as indicated by the subdomain results. These domains correspond to the ‘communication’ goals among the individual treatment objectives (

Table 1) and are closely related to the core symptoms of ASD.

The ‘daily living skills’ domain corresponded to the ‘ADL’ goals in the individual treatment objectives (

Table 2) and was considered to reflect improvements in the acquisition of daily functional activities associated with ID-related symptoms. However, as no significant differences were observed at the subdomain level, the specific daily living activities that improved likely varied among participants.

Nevertheless, the confidence intervals for the effect sizes ranged from below small to large, indicating a high degree of uncertainty and the inclusion of ranges consistent with the absence of effect.

4.4. Considerations Regarding Sensory Function

In the pre-intervention results, seven participants were classified as ‘higher than average’ or ‘much higher than average’, indicating difficulties in sensory regulation. However, no significant differences were observed between pre- and post-intervention scores, suggesting no measurable change.

Comparison of mean scores showed an overall upward trend, indicating a tendency toward increased sensory challenges. Based on score classification changes, four of the ten participants demonstrated worsening sensory regulation difficulties.

This is likely attributable to positive changes in treatment goals and adaptive behaviour, which increased the exploratory interactions of children with their environment. Consequently, daily challenges became more visible, enhancing the awareness of parents for underlying sensory processing issues.

Although some previous studies on SIT have shown improvements in sensory processing, these involved different assessment tools [

55] or the original SP [

56] rather than the SSP. The present findings suggest that, while the SSP is useful for evaluating sensory characteristics in this population, it may be less suitable as an outcome measure for detecting therapeutic effects.

4.5. Considerations Regarding Parental Stress

Both before and after the intervention, parents exhibited high levels of stress, with no observable change.

In this study, the PSI-SF was used to assess child-rearing stress, based on the hypothesis that improvements in children through SIT would reduce parental stress. However, comparison with previous parenting stress intervention studies revealed key differences: whereas this study focused the child as the intervention target, prior research primarily targeted parents and parent-children interactions. Additionally, most previous studies used the full PSI [

57,

58,

59], with only limited use of the shortened PSI-SF [

60].

For these reasons, no change in parental stress levels was observed in this study.

4.6. Considerations Regarding the Relationship Between Evaluation and Measurement Results and SIT

The results show wide confidence intervals for effect sizes, indicating considerable uncertainty. Therefore, we focused on items with effect sizes showing at least ‘small’ confidence intervals to examine their relationship with sensory integration theory.

Analysis of individual treatment goals and behaviours suggested that SIT may influence core ASD symptoms, including social communication deficits and restricted, repetitive behavioural patterns, in children with ASD and ID, while also supporting the development of adaptive functioning, particularly in activities of daily living.

From the perspective of the mechanisms of SIT, the promotion of praxis development in participating children is considered a key factor underlying these changes. Konishi has proposed that ‘some autistic symptoms can be regarded as behavioural dysfunctions arising from sensory integration dysfunction’ [

61]. Praxis, the ability to plan and execute novel movements and actions, is essential for interacting with the physical environment [

5] (pp. 73–87).

Difficulties in adaptive functioning, particularly those related to ADL, can thus be interpreted as challenges arising from impairments in praxis. The treatment goals set for participants, such as eating (

Table 1) and table activities (

Table 3), may reflect difficulties in planning motor actions involving physical tools such as utensils, crayons, or scissors, that is, challenges in effectively interacting with the physical environment.

In this study, SIT was implemented in accordance with the ASIFM [

21]. One of the fidelity conditions of the ASIFM is that ‘the child is engaged in activities that challenge praxis and the organisation of behaviour’, and many treatment activities in this study were designed to promote the development of praxis. The treatment aimed to enhance adaptive functioning through promoting behavioural changes.

Ayres [

62] described the relationship between praxis and language by stating that ‘if language pertains to the social environment, praxis pertains to the physical environment; both enable interaction and transaction’. The author further suggested that ‘praxis and language both require ideation or concept formation as cognitive functions, both depend on the integration of sensory input, and both involve planning that allows for motor expression’.

The core ASD symptoms underlying ‘communication’, the primary concern and treatment goal, reflect difficulties in social environmental interaction. Therefore, improvements in behavioural function likely facilitated interactions with both physical and social environments, particularly through language development.

In summary, although effect sizes varied widely and considerable uncertainty remains regarding the causes and correlations of observed changes, the SIT perspective suggests the following sequence: improvements in behavioural functioning led to enhanced adaptive functioning and language (which shares common foundations with behaviour), and these changes subsequently influenced core ASD symptoms.

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study suggest the potential for positive changes associated with SIT in children with ASD and co-occurring ID. However, because participants also received regular ryoiku (

Table 4), it is possible that these concurrent interventions had a greater influence than SIT itself. In addition, although the effect sizes were calculated based on the total sample to avoid overestimation, it should be noted that the effective sample size was smaller for some analyses and that the confidence intervals were relatively wide.

Regarding feasibility, the present findings indicate that the once-weekly, 8-week programme was a practical and appropriate design for clinical settings in Japan. Nonetheless, future studies should continue to examine the effects of SIT while accounting for the potential influence of regular ryoiku.

This study also has several structural limitations: it was a preliminary study with a small sample size, used a single-group pre–post design without a control group, involved the same individual as both assessor and therapist, and was conducted at a single site. These factors should be addressed in future research to strengthen the validity and generalisability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

In this exploratory study, SIT was implemented for children with ASD and co-occurring ID to examine its feasibility and potential for inducing change.

Of the 11 children who met the eligibility criteria, 10 completed all stages of assessment and intervention, suggesting that the programme was feasible. Although SIT was delivered once a week to reflect realistic clinical conditions in Japan, an infrequent schedule that may have made changes more difficult to detect, improvements were observed in individual treatment goals as measured by GAS and in adaptive behaviour as assessed using the VABS-II. However, because participants also received regular ryoiku, these effects may have been influenced by concurrent interventions. In addition, the confidence intervals for the effect sizes ranged widely, from below small to large, indicating some uncertainty in the results. In addition, SSP and PSI-SF results showed no changes in sensory regulation difficulties or child-rearing stress levels.

In preparation for larger-scale future studies, the relationship between the present findings and SIT was examined with reference to previous research. The observed changes in individual treatment goals and adaptive behaviours appeared to be associated with core ASD symptoms, including deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities, as well as with adaptive functioning difficulties related to ID. These results suggest that SIT may influence both the core symptoms of ASD and adaptive functioning. Furthermore, these effects may be mediated by interactions with the physical environment through the development of praxis, along with interactions within the social environment through language function, which is thought to share a common foundation with praxis.

This study was an exploratory investigation, and although participants also received regular ryoiku, the absence of a control group made it impossible to verify its influence. Other limitations included the small sample size and the fact that the same individual served as both assessor and therapist. Future studies should address these limitations and be conducted on a larger scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, study design, and development of research procedures, H.N., K.T., K.N., and T.K.; supervision of study implementation, K.T. and K.N.; intervention study, H.N.; development of treatment content, data analysis, and original draft preparation, H.N., K.T., and K.N.; guidance on study implementation and manuscript preparation, T.K.. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Committee on Research Ethics, Graduate School of Comprehensive Rehabilitation, Osaka Prefecture University (Approval number: 2021-217; March 30, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participating children all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Hidenori Ota, Director of the Nishinomiya City Child and Family Center Clinic, as well as to the physicians, therapists, and staff members who granted permission for and cooperated in the conduct of this study. We also extend our deepest appreciation to the 11 participating children and their parents. We would also like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| OT |

Occupational therapy |

| OTR |

Occupational Therapist Registered |

| SIT |

Sensory Integration Therapy |

| ID |

Intellectual Disability |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| CARS2 |

Childhood Autism Rating Scale Second Edition |

| CARS2-ST |

CARS2-Standard Version |

| DQ |

Developmental Quotient |

| KSPD |

Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development |

| DA |

Developmental Age |

| GAS |

Goal Attainment Scaling |

| COPM |

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure |

| VABS-II |

Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, Second Edition |

| SSP |

Short Sensory Profile |

| PSI-SF |

Parenting STRESS index short form |

| PSI |

Parenting STRESS index |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Igakushoin: Tokyo, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Baio, J.; Washington, A.; Patrick, M.; DiRienzo, M.; Christensen, D.L.; Wiggins, L.D.; Pettygrove, S.; Andrews, J.G.; Lopez, M.; Hudson, A.; Baroud, T.; Schwenk, Y.; White, T.; Rosenberg, C.R.; Lee, L-C.; Harrington, R.A.; Huston, M.; Hewitt, A.; Esler, A.; Hall-Lande, J.; Poynter, J.N.; Hallas-Muchow, L.; Constantino, J.N.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Zahorodny, W.; Shenouda, J.; Daniels, J.L.; Warren, Z.; Vehorn, A.; Salinas, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Dietz, P.M. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Hirota, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Adachi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Kaneda, A.O. Prevalence and cumulative incidence of autism spectrum disorders and the patterns of co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorders in a total population sample of 5-year-old children. Mol Autism 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japanese Association of Occupational Therapists. White Paper on Occupational Therapy 2021.; CBR Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bundy, A.C.; Lane, S.J.; Murray, E.A. Sensory Integration and Practice, 2nd ed.; Tsuchida, R; Konishi, K., Translators; Kyodo Isho Publishing: Tokyo, 2006; p. pp. 3–17, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, M.; Desch, L.; Section On Complementary And Integrative Medicine; Council on Children with Disabilities. Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders. In Pediatrics; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012; Volume 129, pp. 1186–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Honan, I. Effectiveness of pediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Aust Occup Ther J 2019, 66, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Dumont, R.L.; Arbesman, M.; May-Benson, T.A. Efficacy of occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration®: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther 2018, 72, 7201190010p1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, S.A.; Lane, S.J.; Mailloux, Z.; May-Benson, T.; Parham, L.D.; Roley, S.S.; Schaaf, R.C. A systematic review of Ayres Sensory Integration intervention for children with autism. Autism Res 2019, 12, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Benevides, T.; Mailloux, Z.; Faller, P.; Hunt, J.; van Hooydonk, E.; Freeman, R.; Leiby, B.; Sendecki, J.; Kelly, D. An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: a randomized trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2014, 44, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omairi, C.; Mailloux, Z.; Antoniuk, S.A.; Schaaf, R. Occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration®: a randomized controlled trial in Brazil. Am J Occup Ther 2022, 76, 7604205160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, E.; McNamara, R.; Busse, M.; Delport, S.; Williams-Thomas, R.; Maboshe, W.; Gillespie, D.; Milosevic, S.; Brookes-Howell, L.; Wright, M.; Hastings, R.P.; McKigney, A.M.; Glarou, E.; Ahuja, A. Exploring critical intervention features and trial processes in the evaluation of sensory integration therapy for autistic children. Trials 2024, 25, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino-Alarcón, J.; Robles-Bello, M.A.; Valencia-Naranjo, N.; Sarhani-Robles, A. A systematic review of treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder: the sensory processing and sensory integration approach. Children 2024, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Bigham, S.; Mayes, A.; Muskett, T. Recognition and language in low functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2008, 38, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Tateyama, K.; Akamatsu, M.; Arikawa, M.; Yamada, T. Basic research for effectiveness of sensory integration therapy. Jpn J Sens Integr 2015, 15, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health; Labour and Welfare. Guidelines for Child Development Support; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, B.A.; Koenig, K.; Kinnealey, M.; Sheppard, M.; Henderson, L. Effectiveness of sensory integration interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study. Am J Occup Ther 2011, 65, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharian, N.; Raji, P.; Alizadeh Zarei, M.; Baghestani, A.R. Effectiveness of a sensory play activity program with parent engagement for children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 2023, 17, e136750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, A.; May-Benson, T.A.; Aracikul Balikci, A.F.; Tarakci, E.; Dogan, Z.I.; Ilbay, G. Evaluation of Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention on sensory processing and motor function in a child with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: a case report. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 2023, 16, 11795476221148866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, R. Past and future of sensory integration theory. Jpn J Sens Integr 2020, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, L.D.; Roley, S.S.; May-Benson, T.; Koomar, J.; Brett-Green, B.; Burke, J.P.; Cohn, E.S.; Mailloux, Z.; Miller, L.J.; Schaaf, R.C. Development of a fidelity measure for research on the effectiveness of the Ayres Sensory Integration intervention. Am J Occup Ther 2011, 65, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopler, E.; Van Bourgondien, M.E.; Wellman, G.J.; Love, S.R. Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Second Edition (CARS2), Japanese version: Manual. Supervising and translating editors; Uchiyama, T, Kuroda, M, Inada, N., Eds.; Nihon Bunka Kagakusha: Tokyo, 2015; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Society for the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development Test. Shinpan K Shiki Hattatsu Kensahou 2001 Nenban [The Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development Test 2001].; Nakanishiya Shuppan: Kyoto, 2008. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta, N.; Suzuki, K.; Sugawara, T.; Nakai, K.; Hosokawa, T.; Satoh, H. Comparison of Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development and Bayley Scales of Infant Development second edition among Japanese infants. J Spec Educ Res 2013, 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health; Labour and Welfare; Japan. Heisei 24 Comprehensive Welfare Promotion Project Report: Effective Use and Training of Assessment Tools for Children and Adults with Developmental Disabilities 2013, pp. 30.

- Koyama, T.; Osada, H.; Tsujii, H.; Kurita, H. Utility of the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development in cognitive assessment of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009, 63, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y.; Mutsuzaki, H.; Nakayama, T.; Yozu, A.; Iwasaki, N. Relationship between the use of lower extremity orthoses and the developmental quotient of the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development in children with Down syndrome. J Phys Ther Sci 2018, 30, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomchek, S.D.; Dunn, W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the Short Sensory Profile. Am J Occup Ther 2007, 61, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.O.; Carter, A.S. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: associations with child characteristics. J Autism Dev Disord 2008, 38, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiresuk, T.J.; Sherman, R.E. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J 1968, 4, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malec, J.F. Goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation. Neuropsychol Rehabil 1999, 9, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B.M.; Rockwood, K.J.; Mate-Kole, C.C. Use of goal attainment scaling in brain injury in a rehabilitation hospital. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1994, 73, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E.; Powell, C.; Rockwood, K. Goal attainment scaling as a measure of clinically important change in nursing-home patients. Age Ageing 1999, 28, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolee, P.; Zaza, C.; Pedlar, A.; Myers, A.M. Clinical experience with goal attainment scaling in geriatric care. J Aging Health 1999, 11, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, P.W.; Miller, W.C. Goal attainment scaling in the rehabilitation of patients with lower-extremity amputations: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.; Turner-Stokes, L. Goal attainment for spasticity management using botulinum toxin. Physiother Res Int 2006, 11, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurn, J.; Kneebone, I.; Cropley, M. Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2006, 20, 756–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, Z.; May-Benson, T.A.; Summers, C.A.; Miller, L.J.; Brett-Green, B.; Burke, J.P.; Cohn, E.S.; Koomar, J.A.; Parham, L.D.; Roley, S.S.; Schaaf, R.C.; Schoen, S.A. Goal attainment scaling as a measure of meaningful outcomes for children with sensory integration disorders. Am J Occup Ther 2007, 61, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; McColl, M.; Opzoomer, A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther 1990, 57, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Baptiste, S.; Law, M.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: a research and clinical literature review. Can J Occup Ther 2004, 71, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.V.; Balla, D.A. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Vineland-II), Japanese Version.; Tsujii, M, Murakami, T., Eds.; Nihon Bunka Kagakusha: Tokyo, 2014; pp. 51–122. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.V.; Balla, D.A. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition: Survey Forms Manual; Pearson Assessments: Minneapolis, MN, 2005; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, R.M.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Lord, C. Cognitive profiles and social-communicative functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002, 43, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Wang, C.X.; Feng, J.Y.; Wang, B.; Li, C.L.; Jia, F.Y. A developmental profile of children with autism spectrum disorder in China using the Griffiths Mental Development Scales. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 570923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. Performance of typical children on the Sensory Profile: an item analysis. Am J Occup Ther 1994, 48, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. Japanese Sensory Profile: User Manual.; Tsujii, M., Ed.; Nihon Bunka Kagaku-sha: Tokyo, 2015; pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, B.H.; Abidin, R.R. Revision of the Parenting Stress Index. J Pediatr Psychol 1985, 10, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R.; Kanematsu, Y; Araki, A; Narama, M; Shirahata, N; Marumitsu, M; Arayashiki, R.; Japanese edition authors. Parenting Stress Index (PSI), 2nd edition: Manual, Japanese edition.; Employment Issues Research Association: Tokyo, 2012; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, D.R.; Cabral, M.D.; Ho, A.; Merrick, J. A clinical primer on intellectual disability. Transl Pediatr 2020, 9 Suppl 1), S23–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Cascella, M.; Marwaha, R. Intellectual Disability. In StatPearls [Internet].; cited; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), Jan 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Benevides, T.; Mailloux, Z.; Faller, P.; Hunt, J.; van Hooydonk, E; Freeman, R; Leiby, B; Sendecki, J; Kelly, D. An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: a randomized trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2014, 44, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omairi, C; Mailloux, Z.; Antoniuk, S.A.; Schaaf, R. Occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration®: a randomized controlled trial in Brazil. Am J Occup Ther 2022, 76, 7604205160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raditha, C.; Handryastuti, S.; Pusponegoro, H.D.; Mangunatmadja, I. Positive behavioral effect of sensory integration intervention in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Res 2023, 93, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, C.A.; Kaat, A.J.; Thurm, A.; Anselm, I.; Akshoomoff, N.; Bennett, A.; Berry, L.; Bruchey, A.; Barshop, B.A.; Berry-Kravis, E.; Bianconi, S.; Cecil, K.M.; Davis, R.J.; Ficicioglu, C.; Porter, F.D.; Wainer, A.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Leonczyk, C.; Guthrie, W.; Koeberl, D.; Love-Nichols, J.; Mamak, E.; Mercimek-Andrews, S.; Thomas, R.P.; Spiridigliozzi, G.A.; Sullivan, N.; Sutton, V.R.; Udhnani, M.D.; Waisbren, S.E.; Miller, J.S. Person Ability Scores as an alternative to norm-referenced scores as outcome measures in studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2020, 125, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuliński, W.; Nowicka, A. Effects of sensory integration therapy on selected fitness skills in autistic children. Percept Mot Skills 2020, 73, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, A.; May-Benson, T.A.; Aracikul Balikci, A.F.; Tarakci, E.; Dogan, Z.I.; Ilbay, G. Evaluation of Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention on sensory processing and motor function in a child with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: a case report. Clin Case Rep 2023, 16, 11795476221148866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlink, A.; Williams, J.; Pizzano, M.; Gulsrud, A.; Kasari, C. Parenting stress in caregiver-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism: an application of quantile regression mixed models. Autism Res 2022, 15, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhani, A.; Dehghani, M.; Gharraee, B.; Hakim Shooshtari, M. Parent training intervention for autism symptoms, functional emotional development, and parental stress in children with autism disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Asian J Psychiatr 2021, 62, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadarola, S.; Levato, L.; Harrison, B.; Smith, T.; Lecavalier, L.; Johnson, C.; Swiezy, N.; Bearss, K.; Scahill, L. Teaching parents behavioral strategies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD): effects on stress, strain, and competence. J Autism Dev Disord 2018, 48, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, V.S.K.; Fong, D.Y.T. The effects of infant abdominal massage on the parental stress level among Chinese parents in Hong Kong: a mixed clustered RCT. BMC Complement Med Ther 2024, 24, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, K. Autism and conduct disorder: application of sensory integration therapy. In Sensory Integration Research. Japanese Society for Sensory Integration Disorders; Kyodo Isho Shuppansha: Tokyo, 1992; Vol. 9, pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, A.J. Developmental Dyspraxia and Adult Onset Apraxia.; Sensory Integration International: Torrance (CA), 1985; p. pp. 85. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).