Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Composite Fabrication via High-Temperature Oxygen-Free Rolling

2.3. Post-Rolling Heat Treatment (Annealing)

- Phase 1: Temperature screening. Representative samples from each of the four rolling passes (final thicknesses: 3.9, 2.4, 1.6, 0.9 mm) underwent broad temperature exploration at 300, 350, 400, and 450 °C, each with a 2 h isothermal hold. This phase established preliminary IMC growth kinetics and recovery/recrystallization thresholds, with furnace cooling (~3 °C/min) to ambient temperature (~ 25 °C).

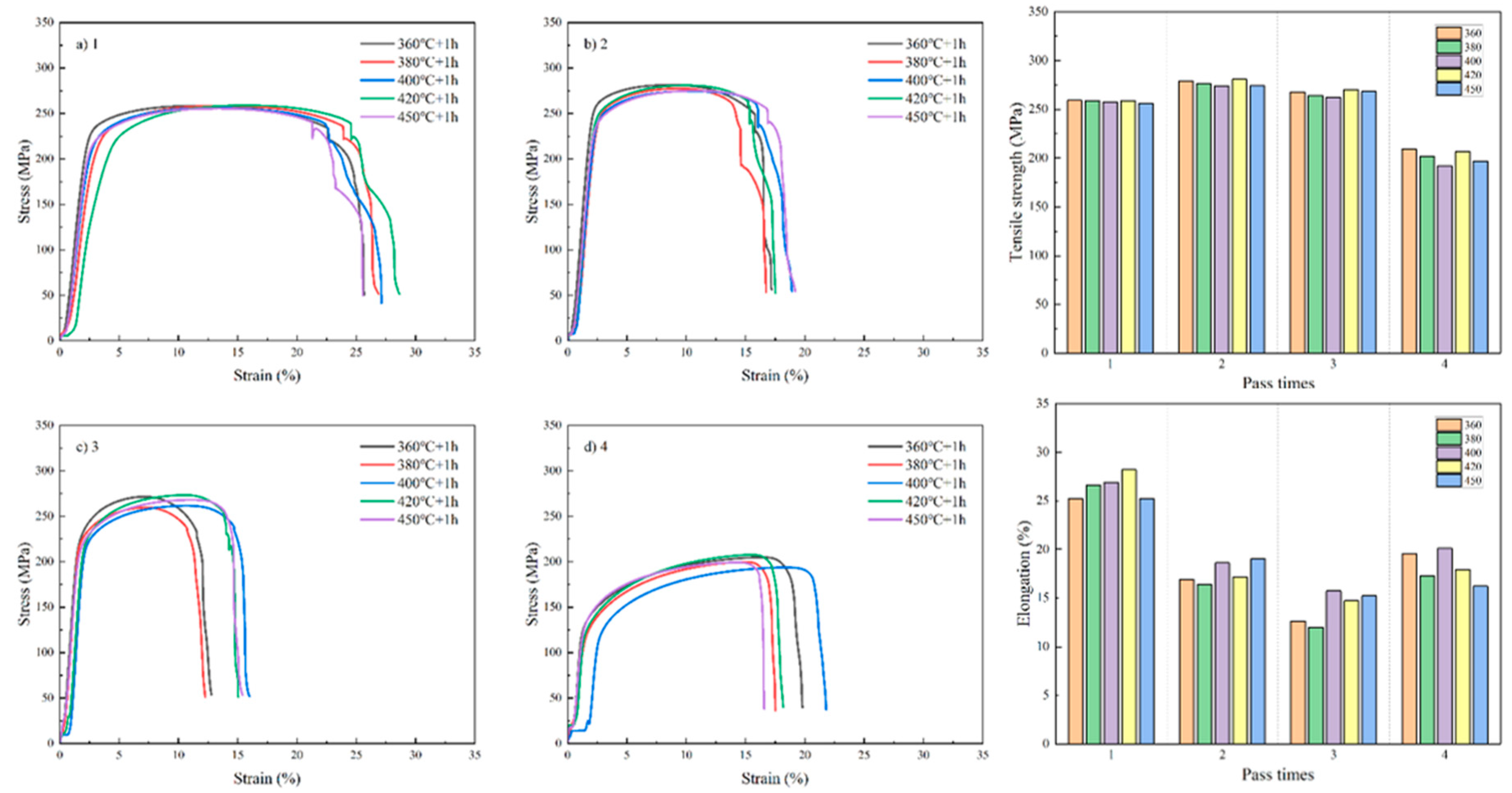

- Phase 2: Temperature refinement. Informed by Phase 1 outcomes, a narrower matrix of 360, 380, 400, 420, and 450 °C was applied to the most promising rolling condition (Pass 4, 70% cumulative reduction), using a standardized 1 h hold time. This refinement targeted the optimal window for balanced IMC thickening (1-3 µm) while preserving matrix ductility. Phase 3: Time optimization. Building on the identified optimal temperature from Phase 2, dwell times of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 h were evaluated for the selected rolling-annealing combination. This phase quantified time-dependent diffusion and phase stability.

2.4. Microstructural Characterization

2.5. Mechanical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evolution of Interfacial Microstructure

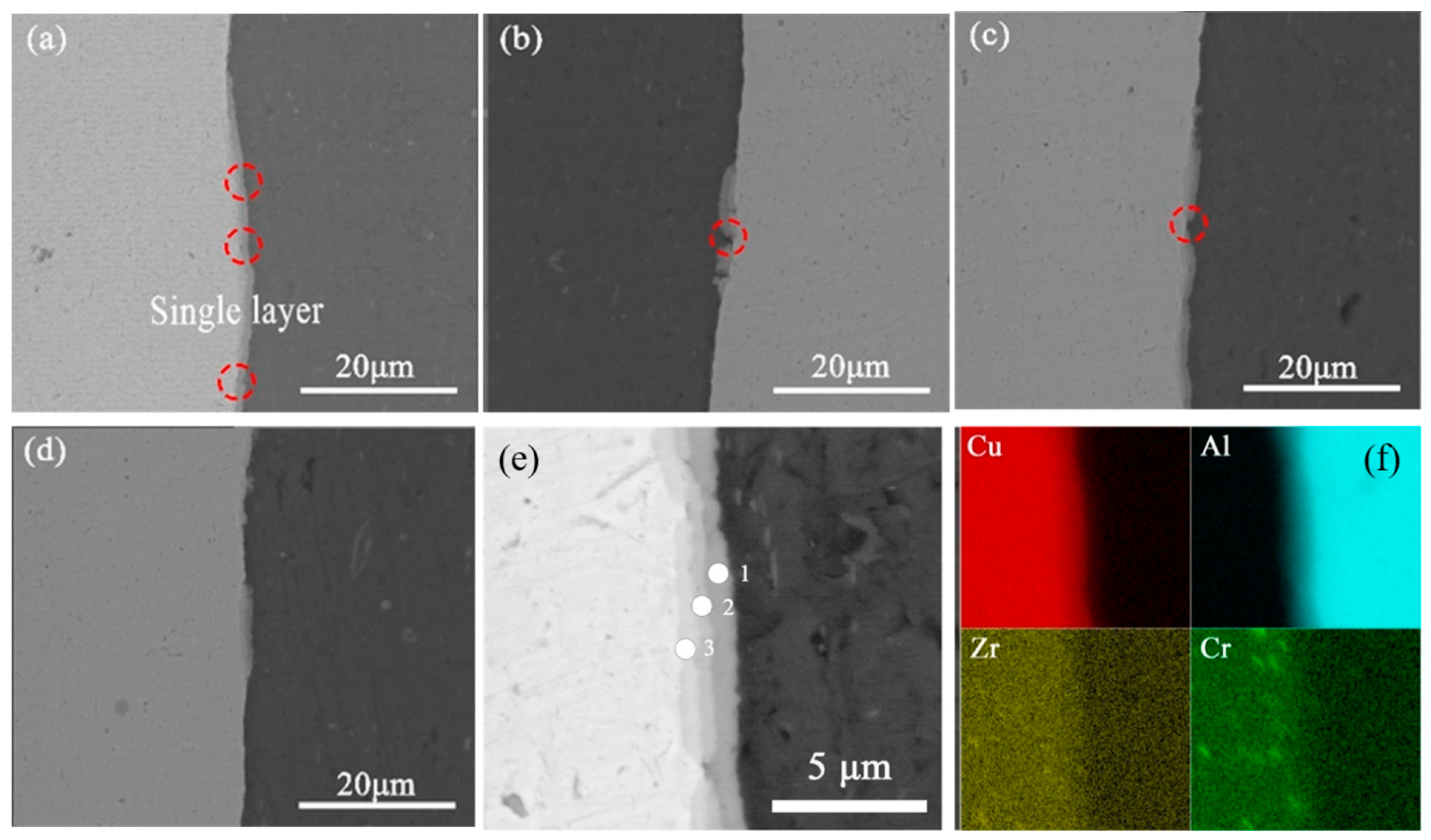

3.1.1. Effect of Rolling Pass Number

| Spot | Element | Atomic Concentration | Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al | 62.09 | Al2Cu |

| Cu | 37.91 | ||

| 2 | Al | 47.64 | AlCu |

| Cu | 52.36 | ||

| 3 | Al Cu |

37.85 62.15 |

Al4Cu9 |

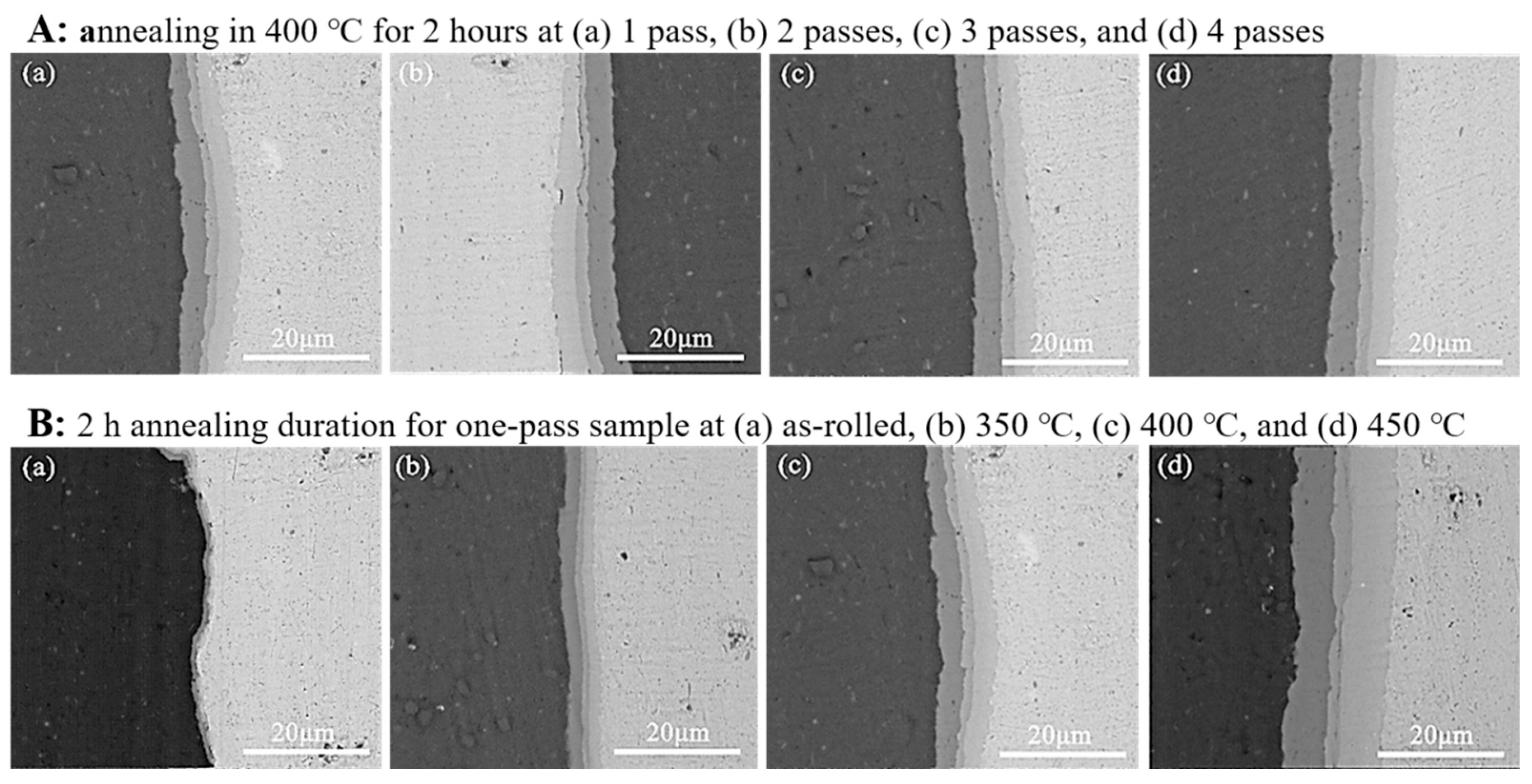

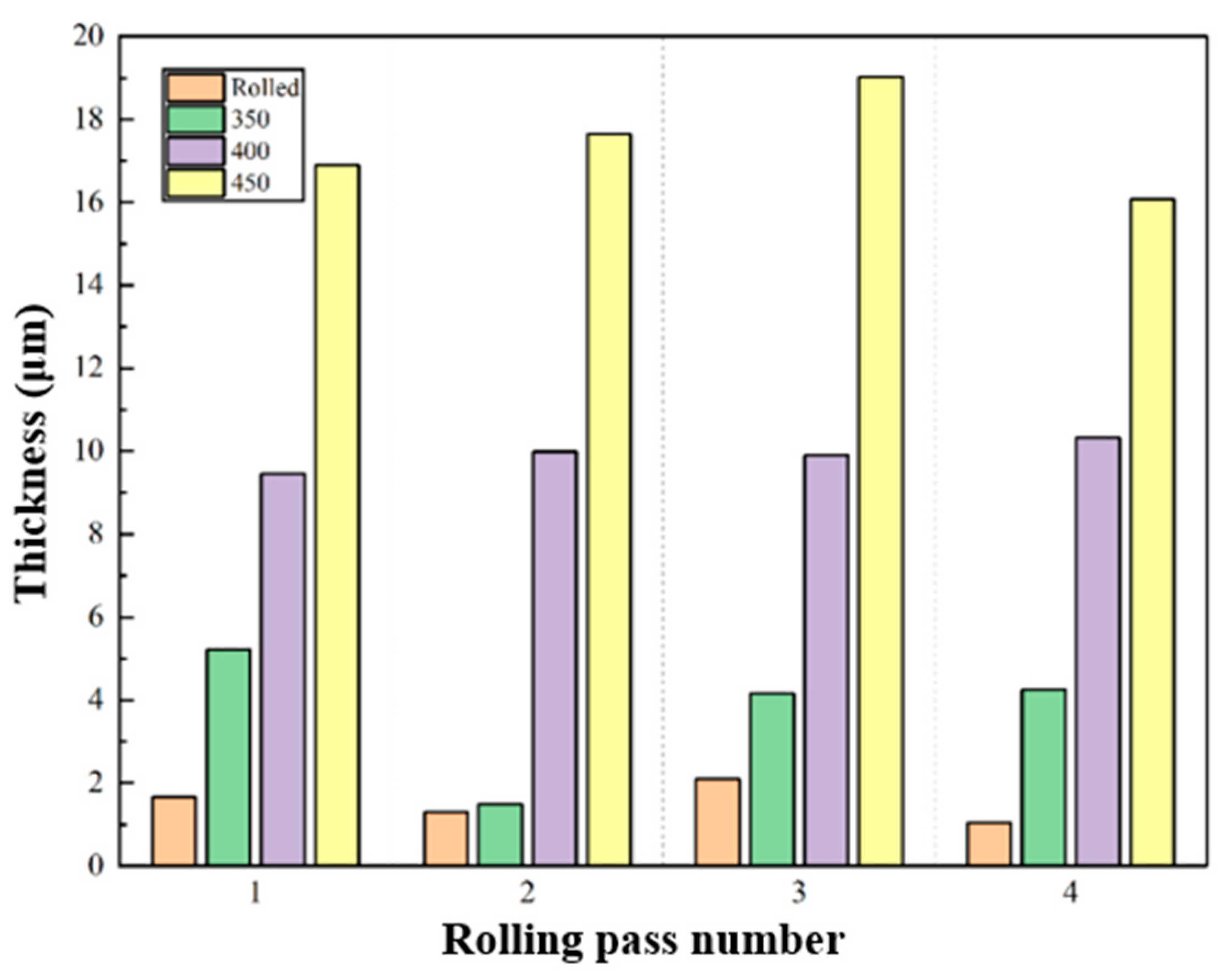

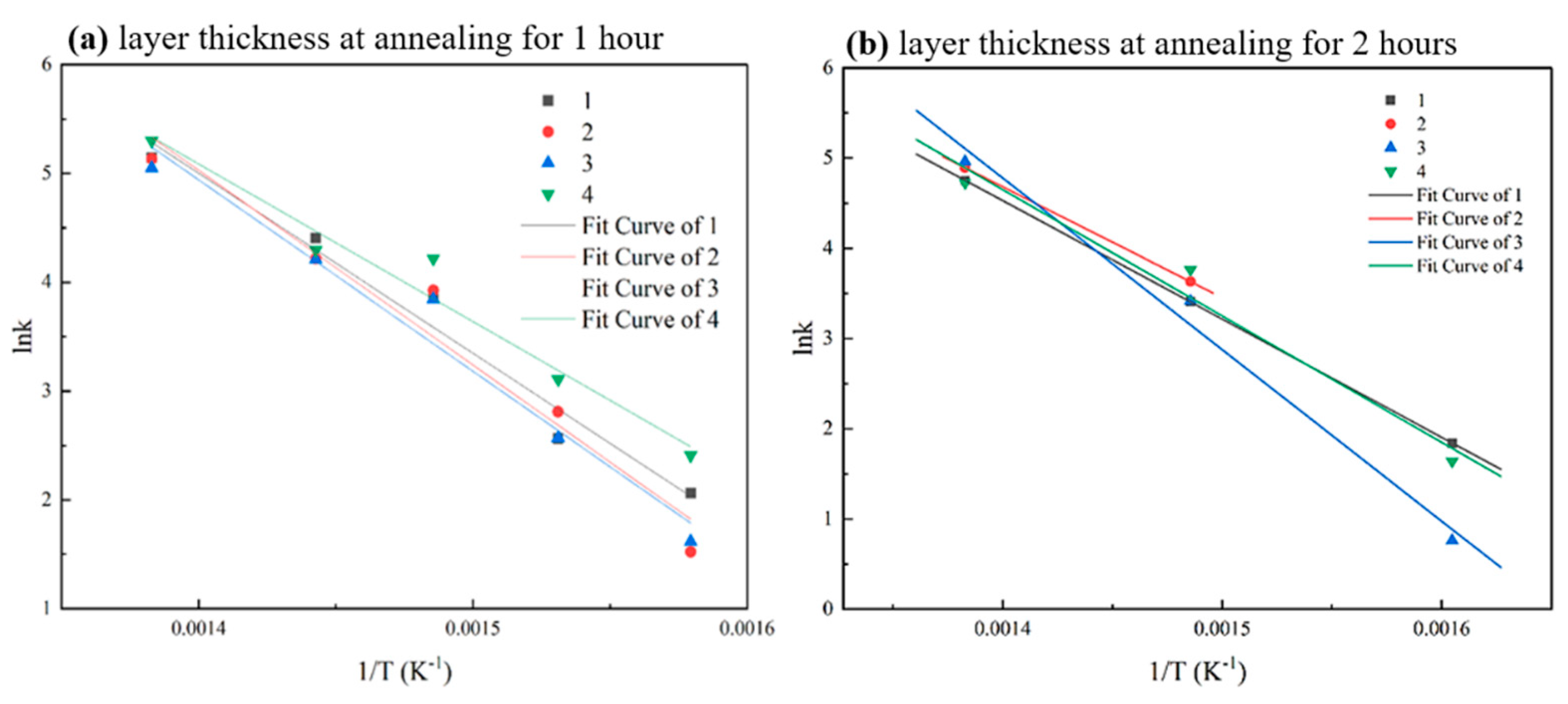

3.1.2. Effect of Post-Rolled Annealing Temperature

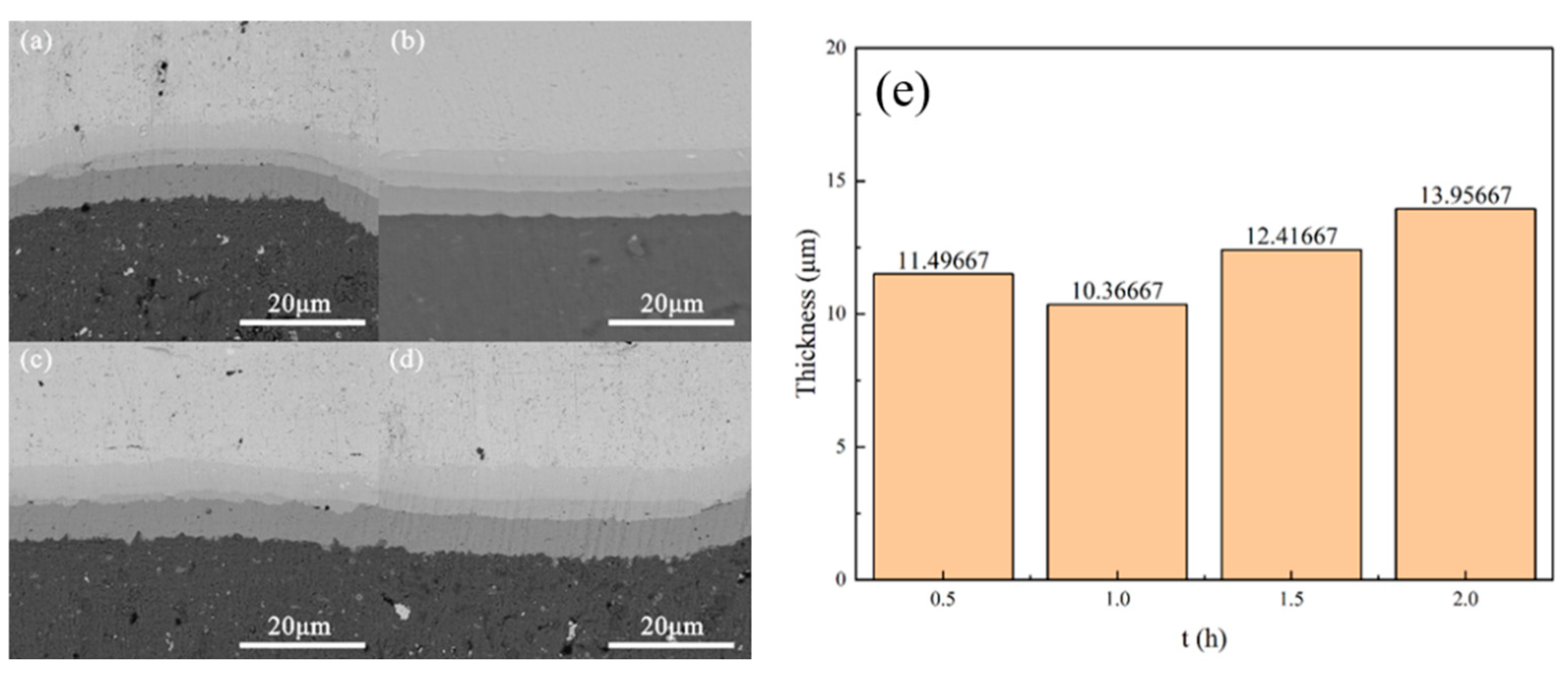

3.1.3. Effect of Post-Rolled Annealing Duration

3.2. Evolution of Mechanical Properties

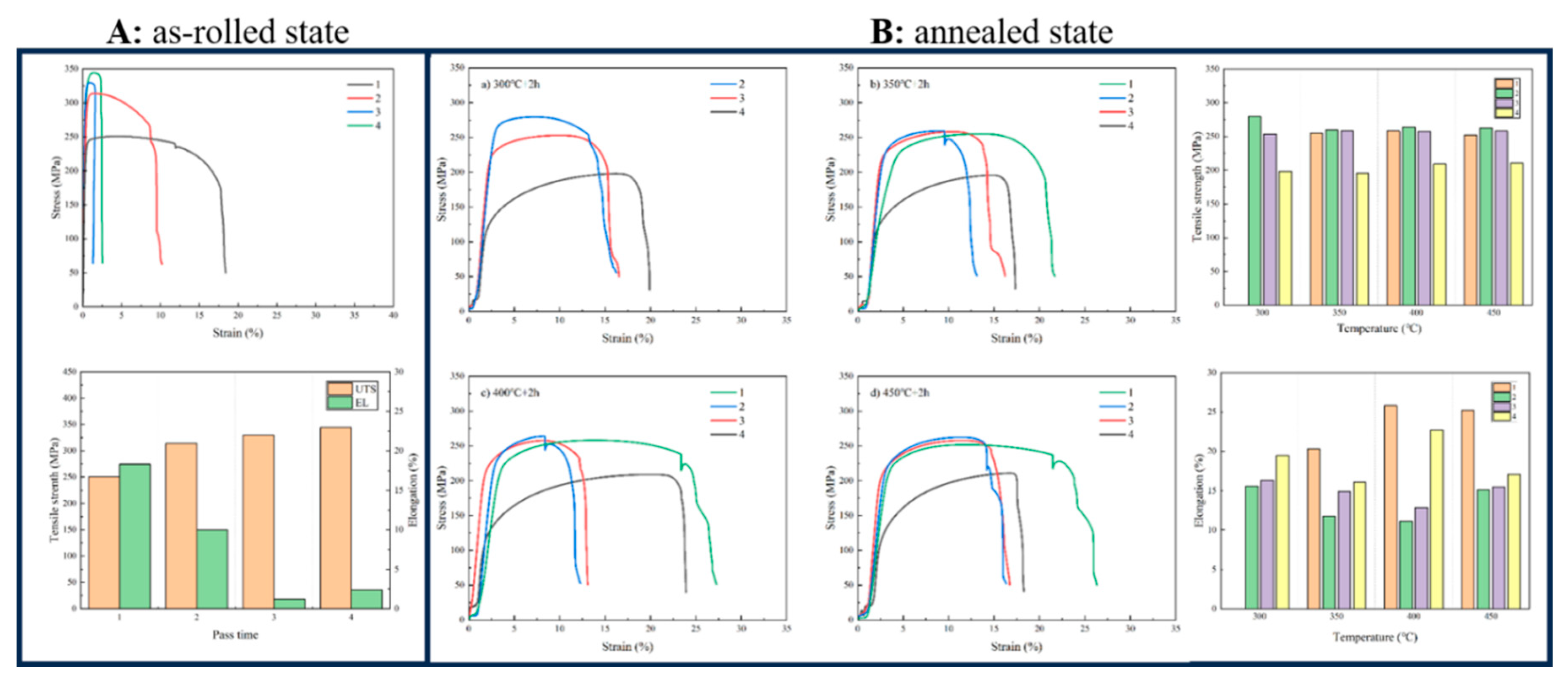

3.2.1. Effect of Rolling Pass Number

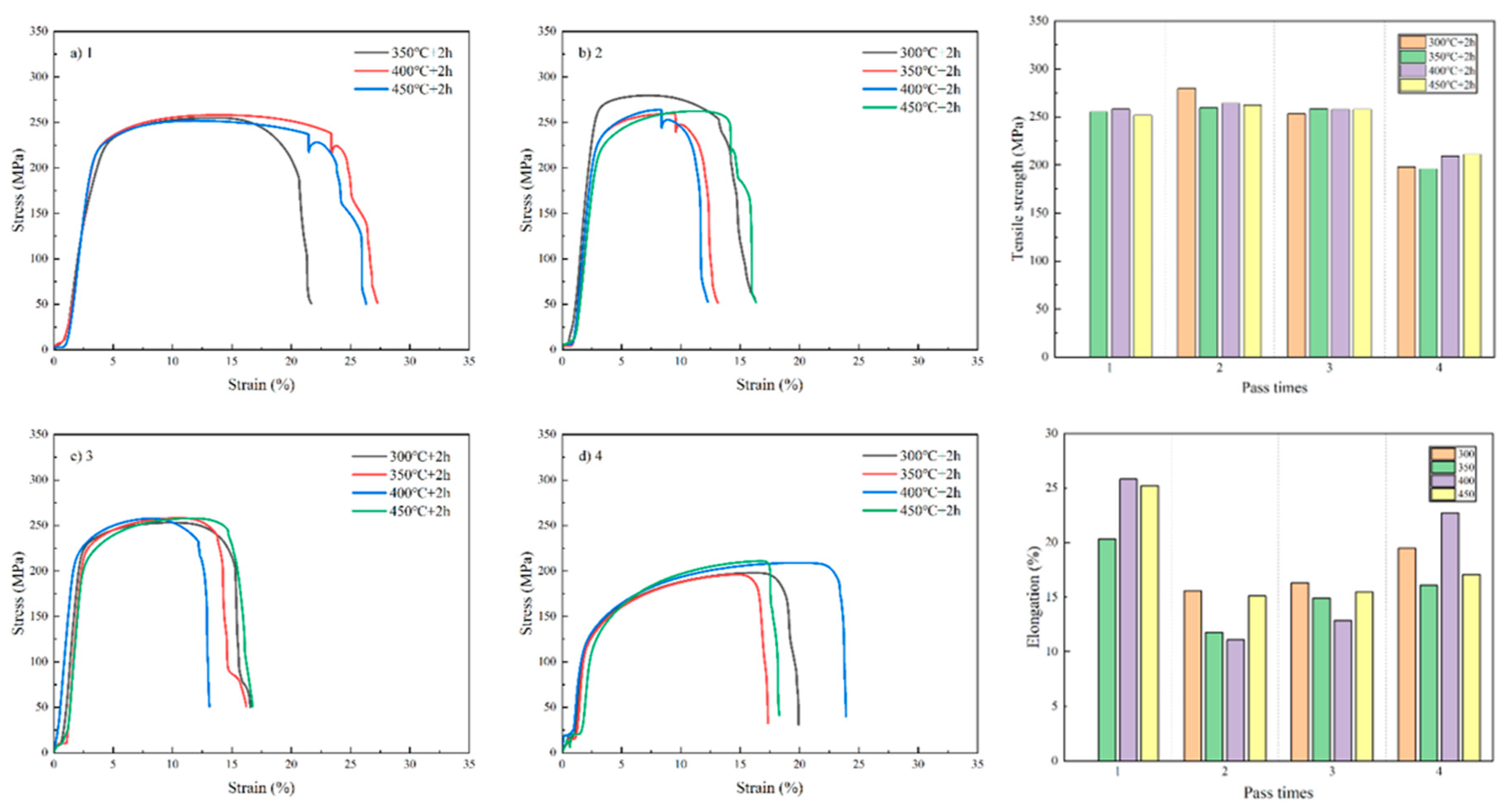

3.2.2. Effect of Post-Rolled Annealing Temperature

3.2.3. Effect of Post-Rolled Annealing Duration

3.2.4. Fractography

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebrahimi, M.; Luo, B.; Wang, Q.; Attarilar, S. High-Performance Nanoscale Metallic Multilayer Composites: Techniques, Mechanical Properties and Applications. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Li, J.; Lei, G.; Song, L.; Kong, C.; Yu, H. High Strength and Thermal Stability of Multilayered Cu/Al Composites Fabricated Through Accumulative Roll Bonding and Cryorolling. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2022, 53, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, T.; Huang, Q. Effect of Annealing Process on Interface Microstructure and Mechanical Property of the Cu/Al Corrugated Clad Sheet. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Luo, B.; Wang, Q.; Attarilar, S. Enhanced Multifaceted Properties of Nanoscale Metallic Multilayer Composites. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Mi, X.; Xie, H.; Feng, X.; Ahn, J.H. Researches for Higher Electrical Conductivity Copper-based Materials. cMat 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, T.; Nansai, K.; Nakajima, K. Major Metals Demand, Supply, and Environmental Impacts to 2100: A Critical Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, A.; Valero, A.; Calvo, G.; Ortego, A. Material Bottlenecks in the Future Development of Green Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Aluminum Alloys for Electrical Engineering: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14847–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Gao, P.; Zhang, J.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, J. Numerical Simulation of Copper-Aluminum Composite Plate Casting and Rolling Process and Composite Mechanism. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh Salout, S.; Mirbagheri, S.M.H. Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Al/Cu Interface in a Bimetallic Composite Produced by Compound Casting. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi, Y.; Oveisi, H. Development of Novel Cellular Copper–Aluminum Composite Materials: The Advantage of Powder Metallurgy and Mechanical Milling Approach for Lighter Heat Exchanger. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 279, 125742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Ebrahimi, M.; Zhao, Y. Shear Behavior of Cu / Al / Cu Trilayered Composites Prepared by High-Temperature Oxygen-Free Rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1004, 175857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhida, J.; Yangyang, X.U.; Jiaxin, Y.U.; Wencai, L.I.U.; Haowen, Z.H.U. Mechanical and Conductive Properties of Cu / 1060Al / Cu Three- Layer Composite Prepared by High-Temperature Oxygen-Free Rolling. Acta Met. Sin 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Sun, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, G.; Shang, Z.; Liu, W. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of High-Temperature Free-Oxygen Rolled Cu/1060Al Bimetallic Composite Materials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Shao, C.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Z.; Liu, H. Effect of Hot Rolling on the Microstructure and Mechanical Performance of a Mg-5Sn Alloy. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, G.; Divinski, S. Grain Boundaries and Diffusion Phenomena in Severely Deformed Materials. Mater. Trans. 2019, 60, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beke, D.L.; Kaganovskii, Y.; Katona, G.L. Interdiffusion along Grain Boundaries – Diffusion Induced Grain Boundary Migration, Low Temperature Homogenization and Reactions in Nanostructured Thin Films. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 98, 625–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.B.; Niverty, S.; Chawla, N. Four Dimensional (4D) Microstructural Evolution of Cu6Sn5 Intermetallic and Voids under Electromigration in Bi-Crystal Pure Sn Solder Joints. Acta Mater. 2020, 189, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ebrahimi, M.; Attarilar, S.; Lu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Q. Layer Thickness Effects on Residual Stress, Microstructure, and Tensile Properties of Cu18150 / Al1060 / Cu18150 Multilayered Composites : An Integrated EBSD-KAM Approach. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, Q.; Ebrahimi, M.; Liu, L.; Guo, F.; Shang, Z. Interfacial Shear Fracture Behavior of C18150Cu/1060Al/C18150Cu Trilayered Composite at Different Temperatures. Materials (Basel). 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, H.; Yu, H. Tensile Properties of Cryorolled Cu/Al Clad Sheet with an SUS304 Interlayer after Annealing at Various Temperatures. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, K.; Kwon, H. Interdiffusion and Intermetallic Compounds at Al/Cu Interfaces in Al-50vol.%Cu Composite Prepared by Solid-State Sintering. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Guo, W.; Shang, Z.; Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, X. The Growth Behavior and Kinetics of Intermetallic Compounds in Cu–Al Interface at 600°C–800 °C. Intermetallics 2024, 168, 108244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-G.; Jung, S.-B. Interfacial Reactions and Growth Kinetics for Intermetallic Compound Layer between In–48Sn Solder and Bare Cu Substrate. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 386, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, M.L.; Ma, H.T.; Dong, W. Growth Kinetics of Cu6Sn5 Intermetallic Compound at Liquid-Solid Interfaces in Cu/Sn/Cu Interconnects under Temperature Gradient. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Tu, Y.; Yuan, T.; Wang, X.; Ni, Z.; Wei, L.; Ali Raza, S.R. An Insight into the Interfacial Structure and Mechanical Properties of Al/Cu Laminated Sheets through Post-Treatment. Vacuum 2025, 240, 114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, R.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, P.; Zuo, Y. Effect of Annealing on the Interface and Mechanical Properties of Cu-Al-Cu Laminated Composite Prepared with Cold Rolling. Materials (Basel). 2020, 13, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Xie, J.; Wang, A.; Wang, W.; Ma, D.; Liu, P. Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Interfacial Microstructure and Bonding Strength of Cu/Al Clad Sheets Produced by Twin-Roll Casting and Rolling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 285, 116804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Gu, H.; Wang, S.; Xuan, Y.; Yu, H. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Interfacial Microstructure and Bonding Strength of Cu/Al Clad Sheets with a Stainless Steel Interlayer. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, G.; Jiang, Z. Effect of Annealing Holding Time on Microstructure, Interface Diffusion Behavior, and Deformation Behavior of Cu/Al Composite Foil After Secondary Micro-Rolling. Materials (Basel). 2025, 18, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, M.; Joudaki, J.; Kheder, H. Residual Stresses Due to Roll Bending of Bi-Layer Al-Cu Sheet: Experimental and Analytical Investigations. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 2017, 52, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bian, Y.; Yang, M.; Ma, R.; Fan, Y.; Du, A.; Zhao, X.; Cao, X. Investigation of Coordinated Behavior of Deformation at the Interface of Cu–Al Laminated Composite. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 6545–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEE, S.; LEE, M.-G.; LEE, S.-P.; LEE, G.-A.; KIM, Y.-B.; LEE, J.-S.; BAE, D.-S. Effect of Bonding Interface on Delamination Behavior of Drawn Cu/Al Bar Clad Material. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, s645–s649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas-Boca, I.-M.; Iluțiu-Varvara, D.-A.; Tintelecan, M.; Aciu, C.; Frunzӑ, D.I.; Popa, F. Studies on Hot-Rolling Bonding of the Al-Cu Bimetallic Composite. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Ding, W.; Su, F.; Shang, Z. Characteristic Investigation of Trilayered Cu/Al8011/Al1060 Composite: Interface Morphology, Microstructure, and in-Situ Tensile Deformation. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2021, 31, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Ding, W.; Su, F. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Cu/Al8011/Al1060 Trilayered Composite: A Comprehensive Study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14695–14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Ding, W.; Shang, Z.; Luo, L. Evaluation of Interface Structure and High-Temperature Tensile Behavior in Cu/Al8011/Al5052 Trilayered Composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 798, 140129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Q.; Kong, X.; Sun, W.; Fu, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, K. Fabrication of Cu/Al/Cu Laminated Composites Reinforced with Graphene by Hot Pressing and Evaluation of Their Electrical Conductivity. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, W. Thermal Mechanical Bending Response of Symmetrical Functionally Graded Material Plates. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Ebrahimi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, F. Shear Behavior of Cu/Al/Cu Trilayered Composites Prepared by High-Temperature Oxygen-Free Rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1004, 175857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, M.; Shin, H.-S. Review of the Advancements in Aluminum and Copper Ultrasonic Welding in Electric Vehicles and Superconductor Applications. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 307, 117691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.L.; Liu, D.Y.; Shen, Z.L.; Tao, N.R. Enhanced Precipitation Hardening in Nanograined CuCrZr Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2024, 247, 116118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Wen, H.; Bernard, B.C.; Raush, J.R.; Gradl, P.R.; Khonsari, M.; Guo, S.M. Effect of Temperature History on Thermal Properties of Additively Manufactured C-18150 Alloy Samples. Manuf. Lett. 2021, 28, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, A.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, F. Trace Zr Addition Enhances Strength and Plasticity in Cu-Zr/Al2Cu/Al Alloys via Local FCC-to-BCC Transition: Molecular Dynamics Insights on Interface-Specific Deformation and Strain Rate Effects. Materials (Basel). 2025, 18, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Yao, P. The Diffusion Behavior and Mechanical Properties of CuCrZr/AlMgSi Interaction Layer in Ultra-High Speed Sliding Electrical Contact. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1029, 180628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wei, Y.; Chang, C.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, C. Interface Optimization, Microstructural Characterization, and Mechanical Performance of CuCrZr/GH4169 Multi-Material Structures Manufactured via LPBF-LDED Integrated Additive Manufacturing. Materials (Basel). 2025, 18, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, F.; Xie, G.; Hou, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, X. Rolling Deformation Behaviour and Interface Evaluation of Cu-Al Bimetallic Composite Plates Fabricated by Horizontal Continuous Composite Casting. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 298, 117296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, H. Intermetallic Formation at Interface of Al/Cu Clad Fabricated by Hydrostatic Extrusion and Its Properties. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 8589–8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Huang, Y. Interfacial Intermetallic Compound Modification to Extend the Electromigration Lifetime of Copper Pillar Joints. Front. Mater. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, P.; Zhang, Z.; Huo, Y.; Xie, J. Study on the Phase Structure of the Interface Zone of Cu–Al Composite Plate in Cast-Rolling State and Different Heat Treatment Temperatures Based on EBSD. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, C.J.; Wang, C.Q.; Mayer, M.; Tian, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.H. Growth Behavior of Cu/Al Intermetallic Compounds and Cracks in Copper Ball Bonds during Isothermal Aging. Microelectron. Reliab. 2008, 48, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, J.; Kolednik, O. Fracture Resistance of Aluminum Multilayer Composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2013, 110, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Mehr, V.; Toroghinejad, M.R. Mode Ⅰ Fracture Analysis of Aluminum-Copper Bimetal Composite Using Finite Element Method. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, Q.; Ebrahimi, M.; Liu, L.; Guo, F.; Shang, Z. Interfacial Shear Fracture Behavior of C18150Cu/1060Al/C18150Cu Trilayered Composite at Different Temperatures. Materials (Basel). 2025, 18, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Li, J.; Song, L.; Peng, X.; Kong, C.; Yu, H. Effect of Intermetallic Compounds on the Mechanical Properties of Cu/Al Clad Sheets with an SS304 Interlayer. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 915, 147286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mypati, O.; Pal, S.K.; Srirangam, P. Tensile and Fatigue Properties of Aluminum and Copper Micro Joints for Li-Ion Battery Pack Applications. Forces Mech. 2022, 7, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, R.; Ogura, T.; Matsuda, T.; Sano, T.; Hirose, A. Relationship between Intermetallic Compound Layer Thickness with Deviation and Interfacial Strength for Dissimilar Joints of Aluminum Alloy and Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 735, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, C.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, C.; Liu, J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al/Cu-SS Hybrid Composite via Ball Milling and Friction Stir Processing. iScience 2025, 28, 114008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Mai, Y. Study on Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Layered CuCrZr/Cu-Al2O3 Composite. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Dang, S. Influence Mechanism of Ageing Parameters of Cu-Cr-Zr Alloy on Its Structure and Properties. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, X.; Liang, H.; Feng, P.; Yu, Y.; Kang, X. Investigation of Interface Characteristics and Mechanical Performances of Cu/Al Plate Fabricated by Underwater Explosive Welding Method. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0320970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Li, T.; Yu, J.; Liu, L. A Review of Bonding Immiscible Mg/Steel Dissimilar Metals. Materials (Basel). 2018, 11, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, H.; Attarilar, S.; Shang, Z.; Wang, Q. Interface Characterization of Cu18150/Al1060/Cu18150 Laminated Composite Produced by Combined Cast-Roll and Hot-Roll Technique. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 7111–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. Interface Evolution and Strengthening of Two-Step Roll Bonded Copper/Aluminum Clad Composites. Mater. Charact. 2023, 199, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Hwang, W.-S. Effect of Annealing on the Interfacial Structure of Aluminum-Copper Joints. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.; Ma, D.; Mao, Z.; Wang, J.; Liang, T.; Xie, J. Interface Evolution and Properties of C18150 Cu/1060 Al Composites in the Process of Annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cu | Cr | Zr | Zn | Al | Fe | Si | Ni | Mn | Mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu18150 | 99.081 | 0.720 | 0.102 | 0.042 | 0.023 | - | 0.0079 | 0.015 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 |

| Al1060 | 0.050 | 0.0008 | - | 0.039 | 98.9 | 0.50 | 0.460 | 0.0037 | 0.0041 | 0.0033 |

| Spot | Element | Atomic Concentration | Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al | 61.16 | Al2Cu |

| Cu | 38.84 | ||

| 2 | Al | 51.19 | AlCu |

| Cu | 48.81 | ||

| 3 | Al | 51.59 | AlCu |

| Cu | 48.41 | ||

| 4 | Al | 39.16 | Al4Cu9 |

| Cu | 60.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).