Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

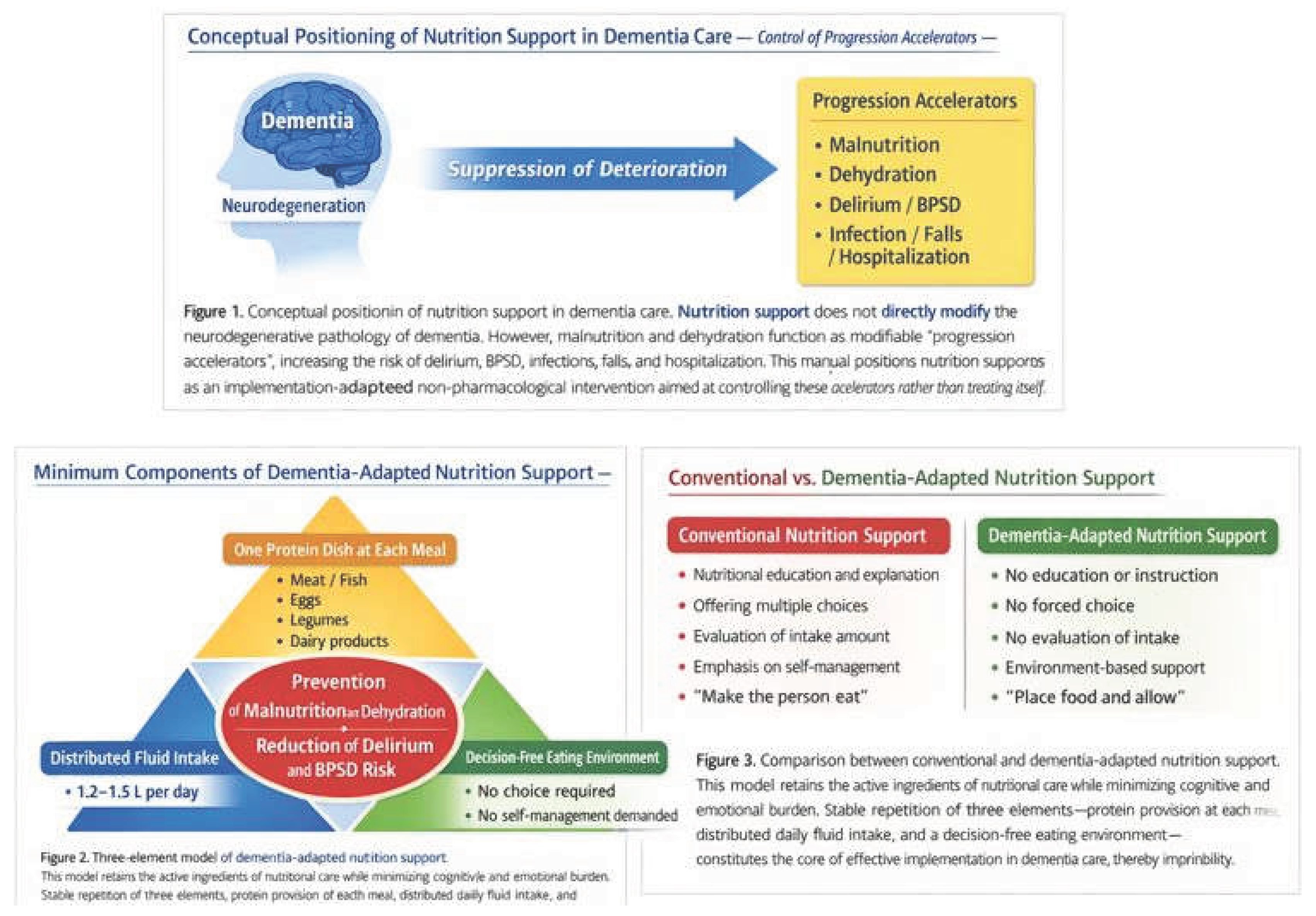

1.1. Malnutrition, Dehydration, and Outcomes in Dementia

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Nutrition Education and Dietary Interventions

2. Constraints in Dietary and Nutritional Interventions

2.1. Cognitive Constraints: Difficulties in Judgment, Choice, and Self-Management

2.2. Behavioral and Environmental Constraints: Instability of Eating Behavior

2.3. Nutritional Interventions as Implementation Failure

3. Separating Active Ingredients from Excessive Burden

3.1. Core Active Ingredients in Dietary and Nutritional Interventions

- Securing adequate energy and protein

- Sustained fluid intake

- Prevention of acute deterioration due to malnutrition and dehydration

3.2. Excessive Implementation Burdens to Be Removed

- Detailed management at the level of individual nutrients

- Judgment and choice at every meal

- Self-recording of food intake

- Evaluation of achievement or intake levels

4. Dementia-Adapted Dietary and Nutrition Intervention Model

4.1. Minimal Component ①: One Protein Item at Each Meal

4.2. Minimal Component ②: Daily Fluid Intake of 1.2–1.5 L

4.3. Minimal Component ③: A Decision-Free Eating Environment

5. Implementation Protocol (Summary)

- Duration: Continuous

- Decision-maker: Caregivers and environment

- Recording: Simple checklist only

- Progression: Do not increase complexity

6. Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

7. Conclusion

Appendix

- Purpose and Positioning

- Malnutrition

- Dehydration

- Delirium and BPSD

- Infection, falls, and hospitalization

- Care staff working in long-term care facilities or home care settings

- Family caregivers supporting people with dementia

- Medical and welfare professionals who wish to integrate dietary and hydration management into daily care

- This manual is not a clinical trial protocol, but an implementation guide for routine care.

- It does not claim therapeutic effects of specific nutritional therapies or foods.

- 2.

- Target Population

- People with mild to moderate dementia

- Individuals capable of oral intake

- Individuals for whom eating and drinking support can be provided in daily life

- Severe dysphagia requiring specialized nutritional management

- Medically unstable acute conditions (e.g., severe infection, acute delirium)

- Cases in which specific food-related stimuli provoke marked refusal or agitation

- Final decisions should always prioritize clinical judgment.

- Even in advanced dementia, this approach may be flexibly applied as supportive eating care that respects the individual’s presence, without evaluating intake volume or reactions.

- 3.

- Fundamental Design Principles

- Do not require nutritional knowledge or understanding

- Do not ask the individual to judge intake quantity or nutritional balance

- Do not require food selection by the individual

- Do not evaluate meal quantity or eating behavior

- Do not reprimand, correct, or persuade

- If anxiety, confusion, or refusal is observed, immediately pause or scale down support

- Fix meal content, timing, and provision method as much as possible

- Avoid making meals “special events”

- Reduce statements such as “Today is special”

- Do not assume motivation, judgment, or self-management by the individual

- Value support that “remains valid even if the person cannot eat”

- 4.

- Overall Structure of Implementation

- Meals: Three meals per day (frequency may be adjusted according to lifestyle)

- Fluid intake: Approximately 1.2–1.5 L per day, divided across time

- Verbal prompting and monitoring: As needed at each meal

- Familiar daily living environment

- Calm locations (avoid excessive stimulation and noise)

- Minimize movement, preparation, and choice requirements

- 5.

- Core Support Components (Three Mandatory Elements)

- Prevention of malnutrition

- Suppression of muscle weakness and susceptibility to infection

- Meat or fish

- Eggs

- Legumes or soy products

- Dairy products

- Quantity, cooking method, and nutritional calculations are not required.

- Failure to finish the meal is not considered failure.

- “I’ll just leave a little here for you.”

- “It’s okay to eat as much as you can.”

- Prevention of dehydration

- Suppression of delirium, constipation, and infection

- Use water, tea, soup, jelly drinks, etc.

- Do not request large volumes at once

- Provide fluids divided across meals and between meals

- Do not assume awareness of thirst.

- Accurate recording of intake volume is not mandatory.

- “Shall we take just a little sip?”

- “I’ll leave this here for you.”

- Prevention of food refusal and confusion

- Prevention of BPSD triggers

- Standardize menus

- Do not present choices

- Keep meal time and location as consistent as possible

- Asking “Which would you like?”

- Presenting intake targets

- Instructing how to eat

- 6.

- Explicitly Excluded Interventions

- Nutrition education or explanatory guidance

- Interventions aimed at evaluating intake volume or nutritional balance

- Treating meals as “rehabilitation tasks”

- Engagement aimed at achieving meal completion or independent eating

- 7.

- Adjustment and Discontinuation Criteria

- Meal quantity (reduction is acceptable)

- Number of meals

- Provision method (texture, temperature, etc.)

- Clear anxiety, refusal, or agitation

- Worsening of BPSD during meal situations

- Increased risk of aspiration

- 8.

- Safety and Burden Management

- Physical risks are relatively low

- The greatest risk is over-intervention

- Minimize caregiver guilt

- A day without eating is not considered failure

- 9.

- Consistency with Existing Evidence

- Associations between malnutrition/dehydration and mortality, hospitalization, and functional decline

- Nutrition and hydration management guidelines for people with dementia

- Evidence that dehydration triggers delirium and BPSD

- 10.

- Use in Research and Practice

- Supplementary materials describing intervention content

- Clarification of implementation methods and fidelity

- Simplified manuals for care staff

- Handout materials for family caregivers

- Shared policy documents for dietary support

References

- El-Sharkawy, A. M.; Watson, P.; Neal, K. R.; Ljungqvist, O.; Maughan, R. J.; Lobo, D. N. Hydration and outcome in older patients admitted to hospital (The HOOP study). Age and Ageing 2015, 44(6), 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet 2020, 396(10248), 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, E. S.; Fong, T. G. Delirium in older persons: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 2017, 318(12), 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, E.; Crichton, M.; Horne, R.; et al. Low-intake dehydration and clinical outcomes in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition 2023, 42(4), 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, H.; Solomon, A.; Visser, P. J.; Hendrix, S. B.; Blennow, K.; Kivipelto, M.; LipiDiDiet Clinical Study Group. 24-month intervention with a specific multinutrient in people with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease (LipiDiDiet): A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology 2017, 16(12), 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soininen, H.; Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; et al. Long-term effects of the LipiDiDiet intervention in people with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2021, 17(4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A. M.; Cederholm, T.; Cereda, E.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Bischoff, S. C. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38(1), 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkert, D.; Chourdakis, M.; Faxen-Irving, G.; Frühwald, T.; Landi, F.; Suominen, M. H.; ESPEN. ESPEN guideline on nutrition and hydration in dementia. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43(2), 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).