Submitted:

10 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

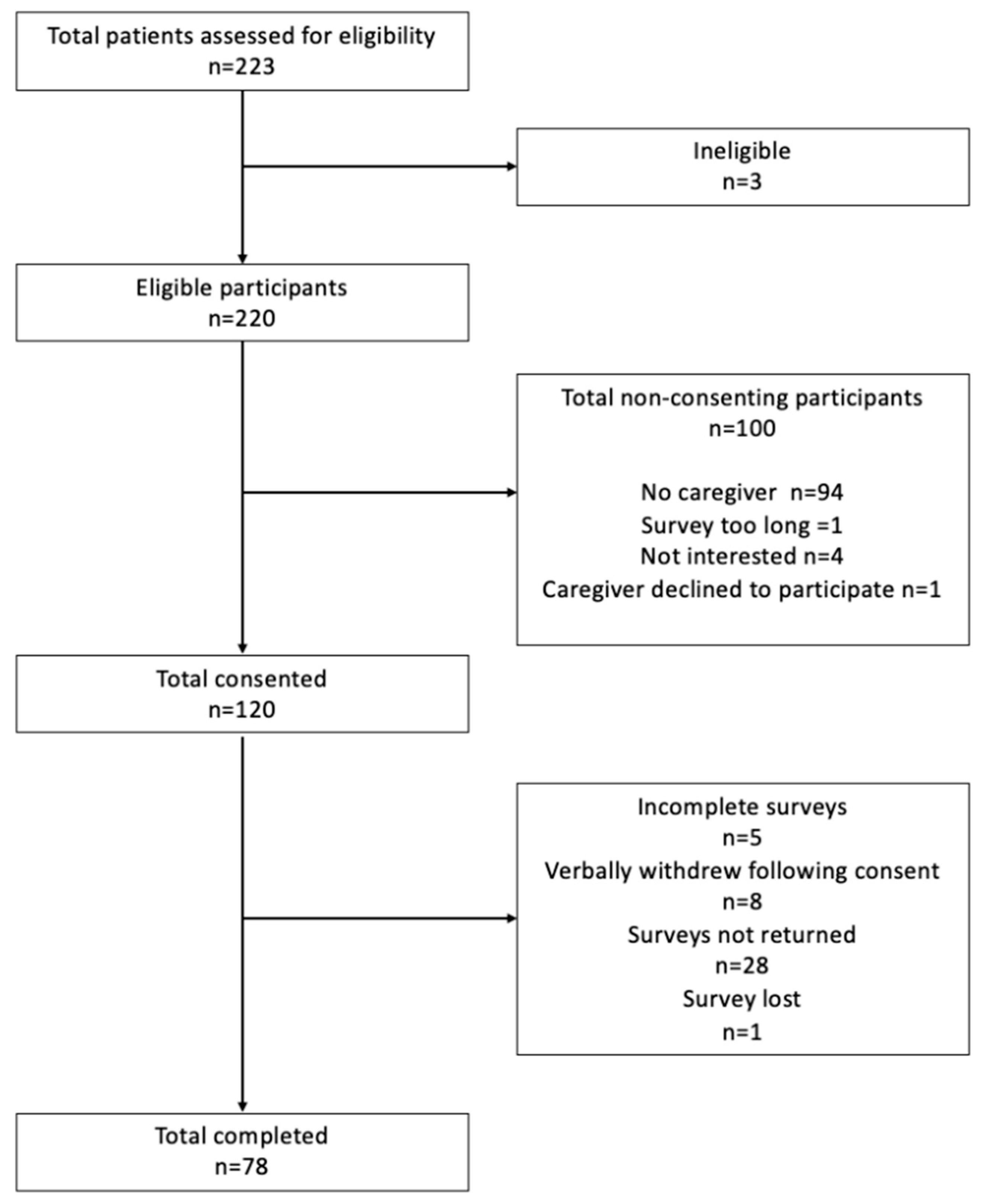

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Nutrition Knowledge

2.5. Caregiver Perception on Food Provision and Delivery of Nutrition Support

2.6. Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.6.2. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Nutrition Knowledge

| Variable | Raw score | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Overall nutrition knowledge 1 | ||

| Sub-section 1. Australian dietary guidelines | 12 (11; 13.25) | 63.2 (57.9; 69.7) a |

| Sub-section 2. Food groups and nutrients | 33.5 (28; 39) | 63.3 (52.8; 73.6) b |

| Sub-section 3. Knowledge on food choices | 7 (6; 8) | 87.5 (75.0; 100.0) c |

| Sub-section 4. Relationship between diet and disease |

25 (23; 28.0) | 71.4 (65.7; 80.0) d |

3.2.1. Correlations

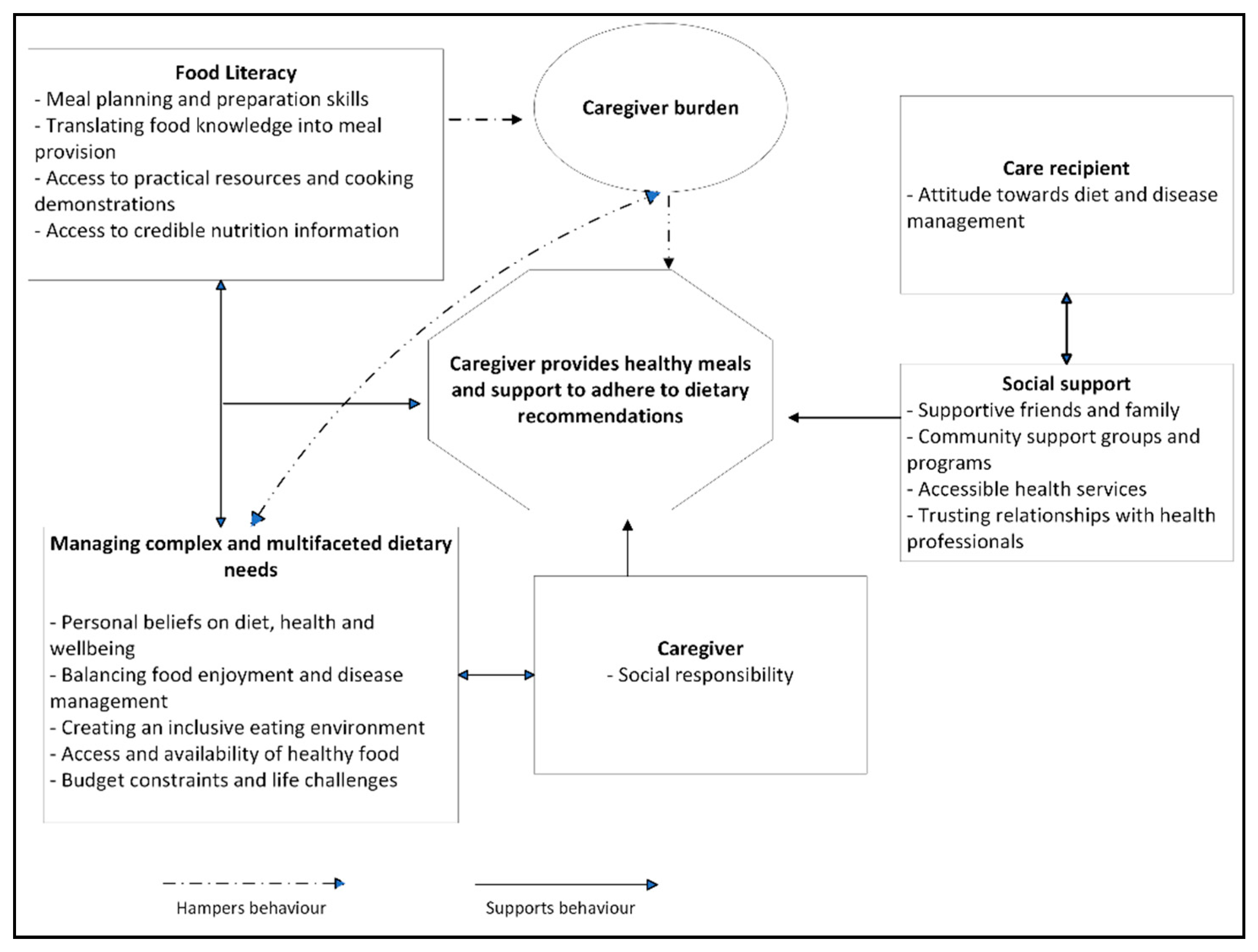

3.2. Caregiver Perception on Meal Provision and Providing Nutrition Support.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collaboration, G.C.K. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709-733. [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic kidney disease: Australian facts; AIHW: Canberra, 2023.

- Tonelli, M.; Wiebe, N.; Guthrie, B.; James, M.T.; Quan, H.; Fortin, M.; Klarenbach, S.W.; Sargious, P.; Straus, S.; Lewanczuk, R.; et al. Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2015, 88, 859-866. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.D.; Roderick, P.J.; May, C.R.; McIntyre, N.; McIntyre, C.; Fluck, R.J.; Shardlow, A.; Taal, M.W. The burden of comorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease stage 3: a cohort study. BMC nephrology 2015, 16, 193. [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2021, 398, 786-802. [CrossRef]

- Kaesler, N.; Baid-Agrawal, S.; Grams, S.; Nadal, J.; Schmid, M.; Schneider, M.P.; Eckardt, K.U.; Floege, J.; Bergmann, M.M.; Schlieper, G.; et al. Low adherence to CKD-specific dietary recommendations associates with impaired kidney function, dyslipidemia, and inflammation. Euro J Clin Nut 2021, 75, 1389-1397. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.S.; Ramos, C.I.; Nerbass, F.B.; Cuppari, L. Diet Quality of Chronic Kidney Disease Patients and the Impact of Nutritional Counseling. J Renal Nut 2018, 28, 403-410. [CrossRef]

- Bowden, K.; Gray, N.A.; Swanepoel, E.; Wright, H.H. A Mediterranean lifestyle is associated with favourable cardiometabolic markers in people with non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease. J Nutr Sci 2021, 10, e42. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.; Conley, M.; Reeves, M.M.; Campbell, K.L.; Kelly, J.T. Evaluating the Impact of Goal Setting on Improving Diet Quality in Chronic Kidney Disease. Frontiers Nut 2021, 8, 627753. [CrossRef]

- Chauveau, P.; Aparicio, M.; Bellizzi, V.; Campbell, K.; Hong, X.; Johansson, L.; Kolko, A.; Molina, P.; Sezer, S.; Wanner, C.; et al. Mediterranean diet as the diet of choice for patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018, 33, 725-735. [CrossRef]

- Dunkler, D.; Kohl, M.; Teo, K.K.; Heinze, G.; Dehghan, M.; Clase, C.M.; Gao, P.; Yusuf, S.; Mann, J.F.; Oberbauer, R. Dietary risk factors for incidence or progression of chronic kidney disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes in the European Union. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015, 30 Suppl 4, iv76-85. [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.A.; Coresh, J.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J.; Grams, M.E.; Crews, D.C.; Mills, K.T.; He, J.; Scialla, J.; Rahman, M.; et al. Adherence to Healthy Dietary Patterns and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. American J Kidney Dis 2021, 77, 235-244. [CrossRef]

- Dunkler, D.; Dehghan, M.; Teo, K.K.; Heinze, G.; Gao, P.; Kohl, M.; Clase, C.M.; Mann, J.F.; Yusuf, S.; Oberbauer, R. Diet and kidney disease in high-risk individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2013, 173, 1682-1692. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.A.; Alvarenga, M.S.; Avesani, C.M.; Cuppari, L. Strategies designed to increase the motivation for and adherence to dietary recommendations in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021, 36, 2173-2181. [CrossRef]

- Notaras, S.; Conti, J. A qualitative analysis of eating behaviour change for patients with diabetes and non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease stages 4-5. J Renal Care 2018, 44, 219-228. [CrossRef]

- Gayomali, C.; Sutherland, S.; Finkelstein, F.O. The challenge for the caregiver of the patient with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008, 23, 3749-3751. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Seo, J. Analysis of caregiver burden in palliative care: An integrated review. Nurs Forum 2019, 54, 280-290. [CrossRef]

- Donald, M.; Beanlands, H.; Straus, S.; Ronksley, P.; Tam-Tham, H.; Finlay, J.; MacKay, J.; Elliott, M.; Herrington, G.; Harwood, L.; et al. Identifying Needs for Self-management Interventions for Adults With CKD and Their Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. American J Kidney Dis 2019, 74, 474-482. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Mansfield, K.; Mullan, J. How do patients and carers make sense of renal dietary advice? A qualitative exploration. J Renal Care 2018, 44, 238-250. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Parmenter, K.; Waller, J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite 2000, 34, 269-275. [CrossRef]

- Hamzaid, N.H.; Flood, V.M.; Prvan, T.; O’Connor, H.T. General nutrition knowledge among carers at group homes for people with intellectual disability. JIDR 2018, 62, 422-430. [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, K.; Wardle, J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. EJCN 1999, 53, 298-308. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D.; Hannan-Jones, M. Validation of a revised General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Australia. Pub Health Nut 2021, 24, 1608-1618. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec Proc 1991, 50, 179-211. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 2021, 18, 328-352. [CrossRef]

- NHMRC. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, 2013. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/adg (accessed 1 August 2024).

- Nelson, M.R.; Banks, E.; Brown, A.; Chow, C.K.; Peiris, D.P.; Stocks, N.P.; Davies AO, R.; Raffoul, N.; Kalman, L.; Bradburn, E.; Jennings, G. 2023 Australian guideline for assessing and managing cardiovascular disease risk. Med J Aust 2024, 220, 482-490. [CrossRef]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Managment of type 2 diabetes: A handbook for general practice, 2020. Available online: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/diabetes/introduction (accessed 1 August 2024).

- Pérez-Torres, A.; Caverni-Muñoz, A.; González García, E. Mediterranean Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): A Practical Approach. Nutrients 2023, 15(1), 97. [CrossRef]

- Khatri, M.; Moon, Y.P.; Scarmeas, N.; Gu, Y.; Gardener, H.; Cheung, K.; Wright, C.B.; Sacco, R.L.; Nickolas, T.L.; Elkind, M.S. The association between a Mediterranean-style diet and kidney function in the Northern Manhattan Study cohort. CJASN 2014, 9, 1868-1875. [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Gavela, E.; Vizcaíno, B.; Huarte, E.; Carrero, J.J. Optimizing Diet to Slow CKD Progression. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 654250. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Carrero, J.J. Diet for the Management of Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease; It Is Not the Quantity, but the Quality That Matters. J Renal Nut 2016, 26, 279-281. [CrossRef]

- Evert, A.B.; Dennison, M.; Gardner, C.D.; Garvey, W.T.; Lau, K.H.K.; MacLeod, J.; Mitri, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Rawlings, K.; Robinson, S.; et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 731-754. [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, L.A.; Green, T.; Harrison, T.N.; Reynolds, K. Dietary approaches to prevent hypertension. Curr Hypertension Rep 2013, 15, 694-702. [CrossRef]

- Worsley, A.; Wang, W.C.; Byrne, S.; Yeatman, H. Different patterns of Australian adults’ knowledge of foods and nutrients related to metabolic disease risk. J Nutr Sci 2014, 3, e14. [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.A.; Cavanaugh, K.L. Dietary sodium in chronic kidney disease: a comprehensive approach. Sem Dialysis 2010, 23, 415-421. [CrossRef]

- Okoyo Opiyo, R.; Nyawade, S.A.; McCaul, M.; Nyasulu, P.S.; Lango, D.B.; Were, A.J.O.; Nabakwe, E.C.; Bukania, Z.N.; Olenja, J.M. Perceptions on Adherence to Dietary Prescriptions for Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease on Hemodialysis: A Qualitative Study. Diseases 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wright, H.H.; Kickbusch, H.; Swanepoel, E.; Gray, N. Factors Influencing Low Sodium Intake in People with Non-Dialysis Dependent Chronic Kidney Disease. J Renal Care 2020, 46, 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B.; Malik, V.S. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol & Behavior 2010, 100, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Chironda, G.; Bhengu, B. Contributing Factors to Non-Adherence among Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Patients: A Systematic Review of Literature. Med & Clin Rev 2016, 02. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.L.; Yates, T.; Smith, A.C.; Chilcot, J. Patient’s perceptions of chronic kidney disease and their association with psychosocial and clinical outcomes: a narrative review. Clin Kid J 2016, 9, 494-502. [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, M.A. The carer’s perception of dietitians’ advice and its impact on the management of patients receiving haemodialysis. JHND 2000, 13, 363-371. [CrossRef]

- Hollingdale, R.; Sutton, D.; Hart, K. Facilitating dietary change in renal disease: investigating patients’ perspectives. J Renal Care 2008, 34, 136-142. [CrossRef]

- Cicolini, G.; Palma, E.; Simonetta, C.; Di Nicola, M. Influence of family carers on haemodialyzed patients’ adherence to dietary and fluid restrictions: an observational study. J Advan Nurs 2012, 68, 2410-2417. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Vargas, P.A.; Tong, A.; Howell, M.; Craig, J.C. Educational Interventions for Patients With CKD: A Systematic Review. American J Kidney Dis 2016, 68, 353-370. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Mansfield, K.; Mullan, J. How do patients and carers make sense of renal dietary advice? A qualitative exploration. J Renal Care 2018, 44, 238-250. [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Darmon, N. Food Choices and Diet Costs: an Economic Analysis1,2. J Nut 2005, 135, 900-904. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Mullan, J.; Mansfield, K. An integrative review of the methodology and findings regarding dietary adherence in end stage kidney disease. BMC nephrology 2017, 18, 318. [CrossRef]

- Yehle, K.S.; Chen, A.M.; Plake, K.S.; Yi, J.S.; Mobley, A.R. A qualitative analysis of coronary heart disease patient views of dietary adherence and web-based and mobile-based nutrition tools. J Cardiopulmon Rehab Prev 2012, 32, 203-209. [CrossRef]

- Wright, H.H.; Lockwood G.; Davey L.; Eqbal Y.; McFarlane C.; Gray N. Caregivers of people with chronic kidney disease: an untapped resource to improve person-centred care? Nut & Diet 2024, 81(S1), 75. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Findings 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18-44 | 6.5 (5) |

| 45-64 | 27.3 (21) | |

| 65+ | 66.3 (51) | |

| Gender | Female Male |

75.6 (59) 24.4 (19) |

| Main language spoken | English Other |

98.7 (76) 1.3 (1) |

| Education Level | Primary School Secondary/High School Trade or certificate Diploma Degree Post-graduate degree |

4 (3) 37.3 (28) 21.3 (16) 24 (18) 12 (9) 1.3 (1) |

| Income per week |

$0 - $750 $751 - $1430 $1431 - $2430 Over $2430 Prefer not to say |

42.9 (33) 29.9 (23) 10.4 (8) 1.3 (1) 15.6 (12) |

| Relationship to care recipient | Spouse/partner Daughter/son Parent Other |

87 (67) 1.3 (1) 7.8 (6) 3.9 (3) |

| Marital Status | Married/partnered Separated/divorced Single |

89.6 (69) 6.5 (5) 3.9 (3) |

| Variable | Category | Findings 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr.) | - | 74 (66; 80) |

| eGFR 2 (ml/min/1.73m2) | - | 27 (18; 42) |

| Gender | Male Female |

75.6 (59) 24.4 (19) |

| CKD Cause | Diabetes Hypertension or vascular disease Glomerulonephritis Other Polycystic kidney disease Reflux neuropathy Obstruction Hereditary |

25.6 (20) 24.4 (19) 21.8 (17) 14.1 (11) 6.4 (5) 3.8 (3) 2.6 (2) 1.3 (1) |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension Diabetes Ischaemic heart disease Cardiovascular disease Peripheral vascular disease |

76.9 (60) 42.3 (33) 29.5 (23) 16.7 (13) 11.5 (9) |

| Multimorbidity 3 | None | 10.3 (8) |

| One Two or more |

32.1 (25) 57.7 (45) |

|

| Smoking status | Smoker Non-smoker Unknown |

29.5 (23) 60.3 (47) 10.3 (8) |

| Kidney Transplant Recipient | Yes No |

15.4 (12) 84.6 (66) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).