Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Research Question

- Identify the surgical techniques and approaches used in MMA for this patient group.

- Examine the clinical considerations influencing treatment selection.

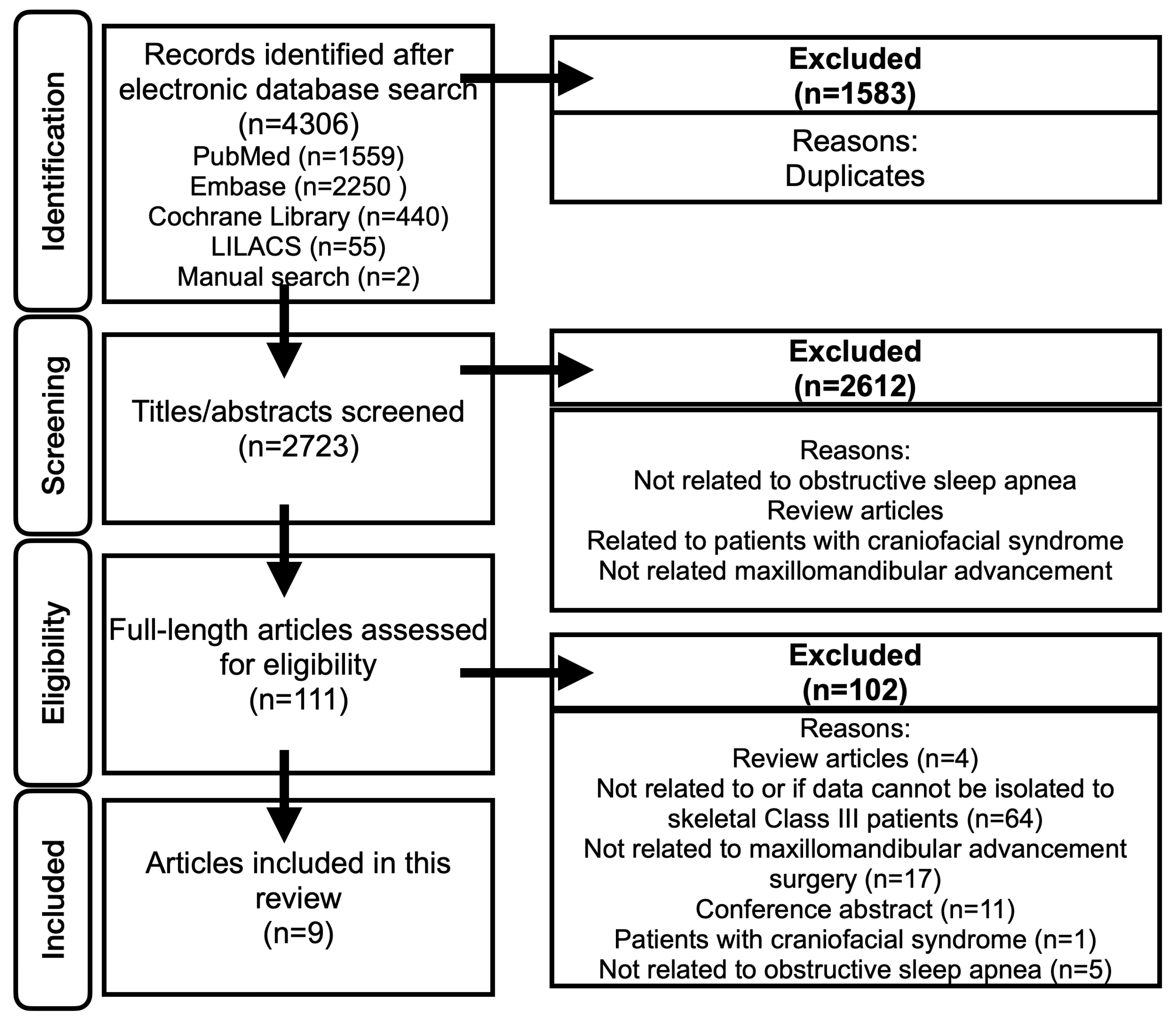

Search Strategy

Study Selection

- Primary research articles

- Patients with skeletal Class III deformities

- Use of MMA or skeletal advancement surgery specifically for the treatment of OSA

- Patients diagnosed with OSA

Exclusion Criteria Were:

- Review articles

- Absence of skeletal Class III patients with OSA

- Inability to isolate data specific to Class III patients

- No skeletal advancement or MMA performed

- Lack of full-text availability

- Presence of craniofacial syndromes

Data Extraction

Analysis and Synthesis of Results

Results

Patient Demographics

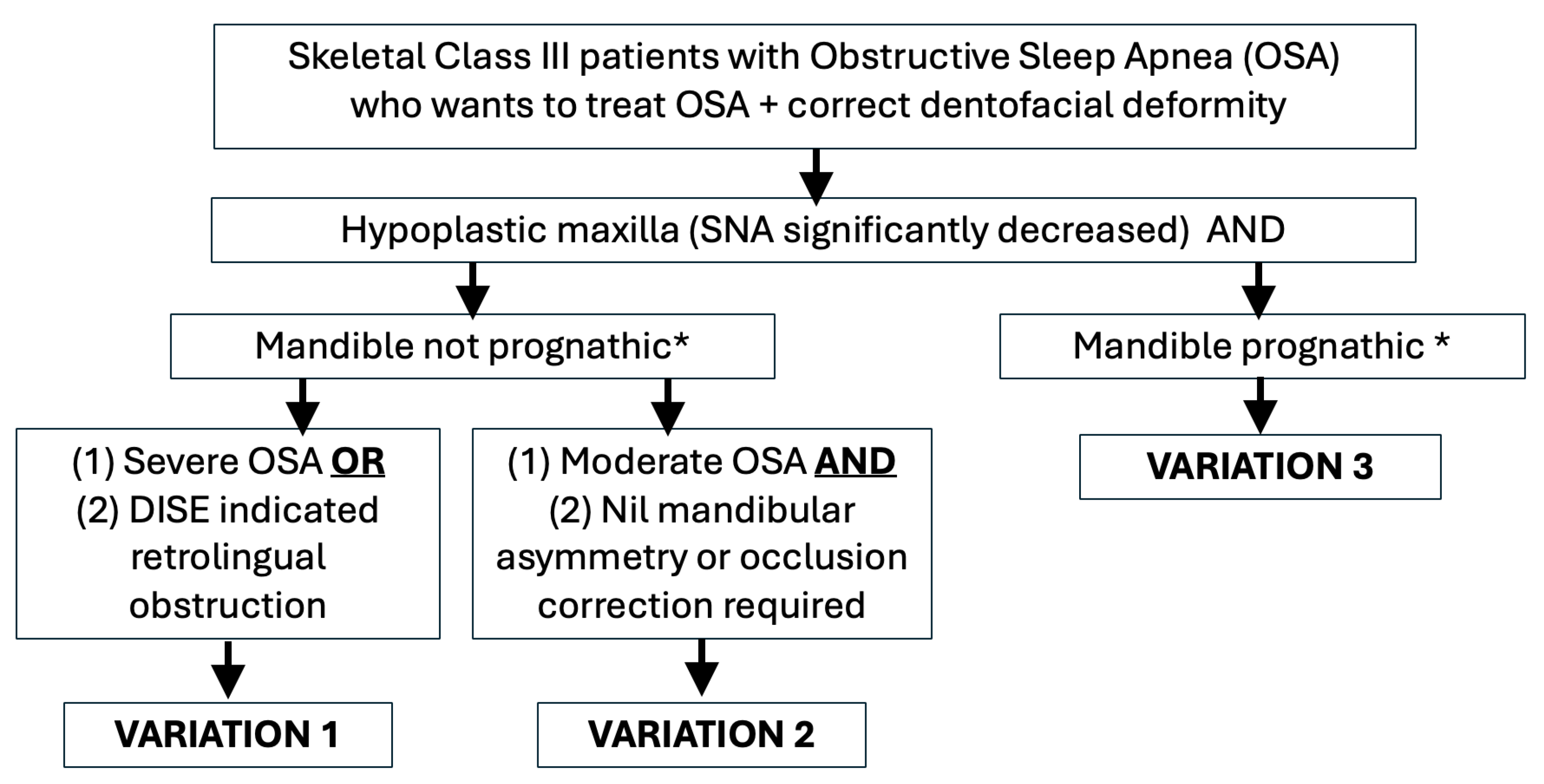

Description of the Variations of MMA

Discussion

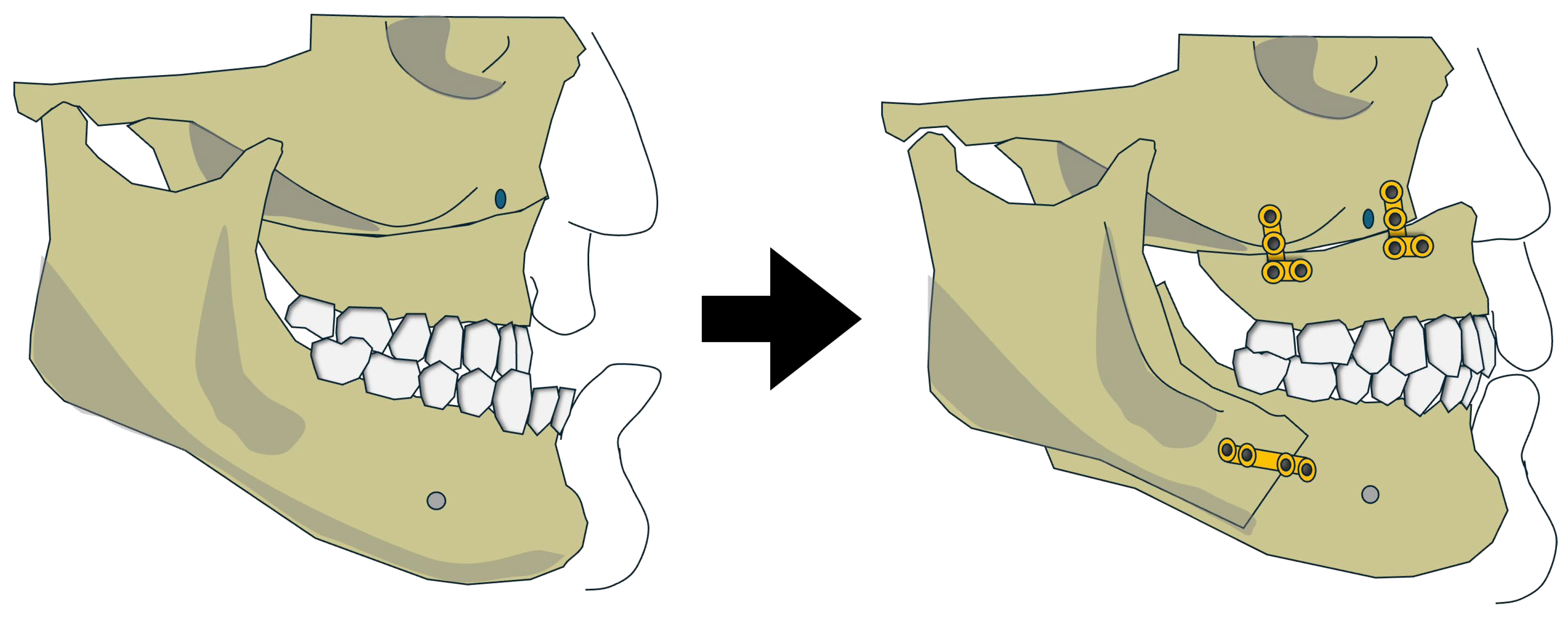

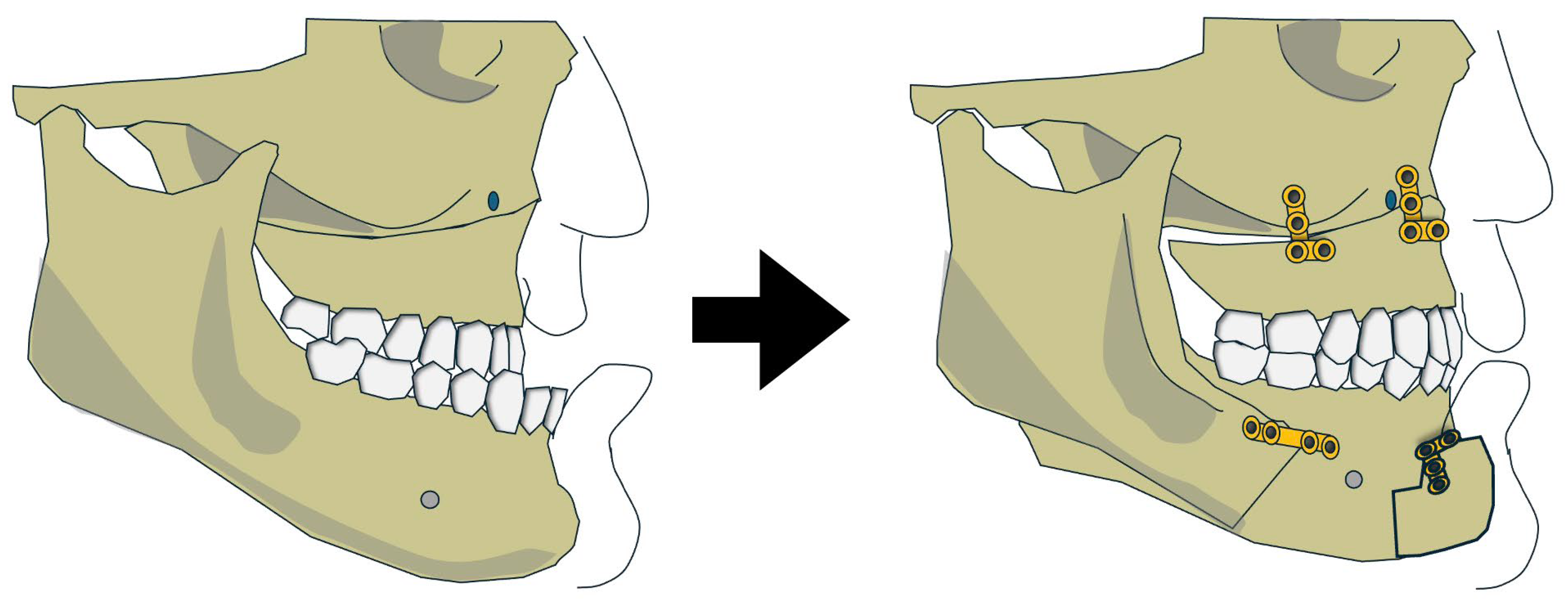

Variation 1: Bimaxillary Advancement

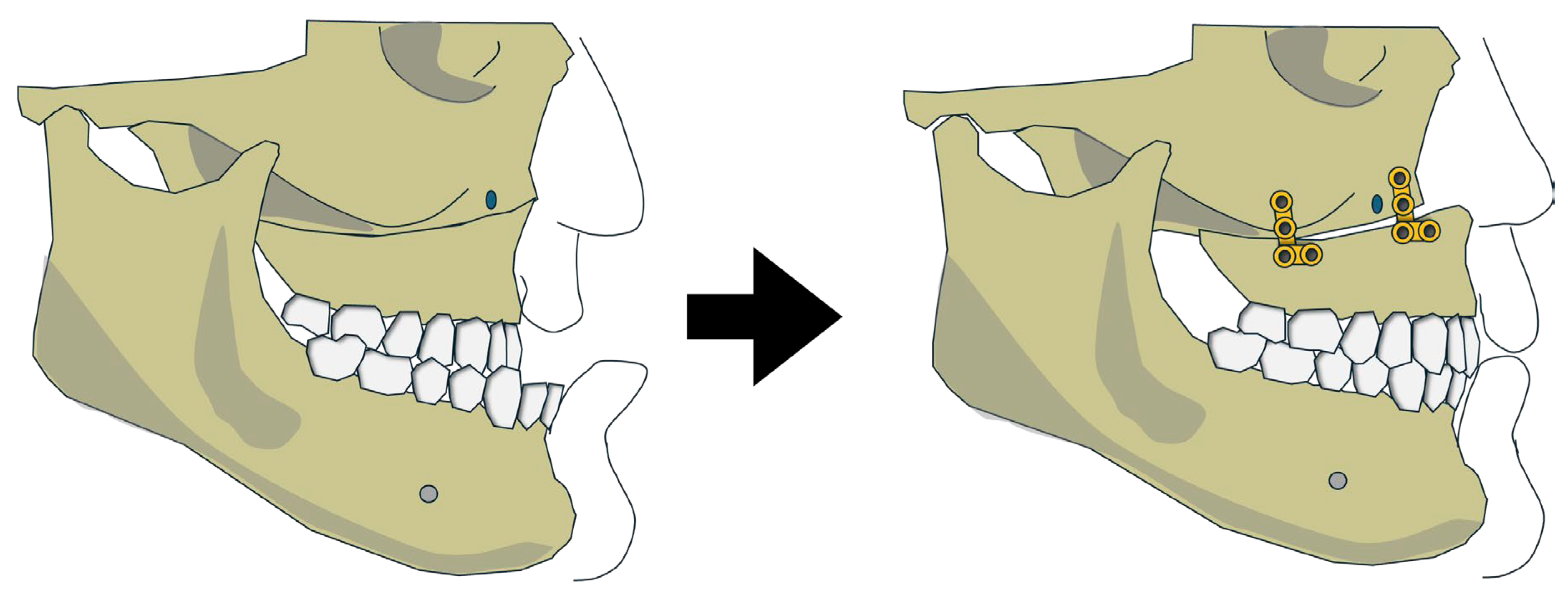

Variation 2: Isolated Maxillary Advancement with Mandibular Auto-Rotation

Variation 3: Maxillary Advancement with Mandibular Setback

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval and Patient Consent

References

- Liu, SY; Awad, M; Riley, R; Capasso, R. The Role of the Revised Stanford Protocol in Today's Precision Medicine. Sleep Med Clin. 2019, 14, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quah, B; Sng, TJH; Yong, CW; Wen Wong, RC. Orthognathic Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2023, 35, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghi, S; Holty, JE; Certal, V; et al. Maxillomandibular Advancement for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, CW; Ng, WH; Quah, B; Sng, TJH; Loy, RCH; Wong, RCW. Modified maxillomandibular advancement surgery for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea: a scoping review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024, 53, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, CW; Quah, B; Colpani, JT; Lee, FKF; Loh, EE; Wong, RCW. Effectiveness of mandibular advancement devices in obstructive sleep apnea therapy for East Asian patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, YY; Leung, JKC; Li, ATC; et al. Accuracy and safety of in-house surgeon-designed three-dimensional-printed patient-specific implants for wafer-less Le Fort I osteotomy. Clin Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, YY; Wan, JCC; Fu, HL; Chen, WC; Chung, JHZ. Segmental mandibular advancement for moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnoea: a pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023, 52, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, CKJ; Yong, CW; Saigo, L; Ren, YJ; Chew, MT. Virtual surgical planning in orthognathic surgery: a dental hospital's 10-year experience. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024, 28, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanakorn Kaewja NS, Kanich Tripuwabhrut. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Prevalence, Upper Airway Dimensions, and Sleep Parameters in Skeletal Class III Malocclusion Patients Undergoing Orthognathic Surgery with Different Vertical Skeletal Patterns. Thai Journal of Orthodontics. 2024:14:6-16.

- Kim, SJ; Ahn, HW; Hwang, KJ; Kim, SW. Respiratory and sleep characteristics based on frequency distribution of craniofacial skeletal patterns in Korean adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0236284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F; Terada, K; Hua, Y; Saito, I. Effects of bimaxillary surgery and mandibular setback surgery on pharyngeal airway measurements in patients with Class III skeletal deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007, 131, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, MD; Godfrey, CM; McInerney, P; Soares, CB; Khalil, H; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, AC; Lillie, E; Zarin, W; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, DS; Romano, M; Sweed, AH; Baj, A; Gianni, AB; Beltramini, GA. Use of CAD-CAM technology to improve orthognathic surgery outcomes in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019, 47, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevi, BC; Toma, L; Pau, M; Sesenna, E. Counterclockwise rotation of the occlusal plane in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSaty, G; Burns, M; Ngan, P. Effects of maxillomandibular advancement surgery on a skeletal Class III patient with obstructive sleep apnea: A case report. APOS Trends Orthod. 2021, 11(2), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, KK; Powell, NB; Riley, RW; Zonato, A; Gervacio, L; Guilleminault, C. Morbidly obese patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea: is airway reconstructive surgery a viable treatment option? Laryngoscope 2000, 110, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchi, P; Novelli, G; Colombo, L; et al. Effectiveness of maxillo-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea patients with and without skeletal anomalies. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010, 39, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T; Manabe, A; Yang, SS; Watakabe, K; Abe, Y; Ono, T. An orthodontic-orthognathic patient with obstructive sleep apnea treated with Le Fort I osteotomy advancement and alar cinch suture combined with a muco-musculo-periosteal V-Y closure to minimize nose deformity. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshijima, M; Honjo, T; Moritani, N; Iida, S; Yamashiro, T; Kamioka, H. Maxillary Advancement for Unilateral Crossbite in a Patient with Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Acta Med Okayama 2015, 69, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C; Chen, Y; Tseng, Y. A Case of Class III Malocclusion with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treated by Orthodontic Treatment Combined Two-jaw Orthognathic Surgery. Taiwanese Journal of Orthodontics 2024, 35, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, M; Taheri, N; Eltahir, L; Erdogan, C; Lee, K; Liu, SY. Maxillomandibular Advancement Efficacy in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients With Class 2 Versus 3 Dentofacial Deformity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023, 169, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, P; Hägg, U; Yiu, C; Merwin, D; Wei, SH. Cephalometric comparisons of Chinese and Caucasian surgical Class III patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. Published. 1997, 12, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y; Niddam, J; Noel, W; Hersant, B; Meningaud, JP. Comparison of aesthetic facial criteria between Caucasian and East Asian female populations: An esthetic surgeon's perspective. Asian J Surg. 2018, 41, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T; Yang, X; Xue, C; Bai, D; Xu, H. Harmonizing soft tissue subnasale and chin position in a forehead-based framework: interracial commonalities and differences between Asian and Caucasian females. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, HD; de Oliveira, BG; Pompeo, DD; de Freitas, PH; Paranhos, LR. Surgical Maxillary Advancement Increases Upper Airway Volume in Skeletal Class III Patients: A Cone Beam Computed Tomography-Based Study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steegman, R; Hogeveen, F; Schoeman, A; Ren, Y. Cone beam computed tomography volumetric airway changes after orthognathic surgery: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023, 52, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, DJ; White, DP; Jordan, AS; Malhotra, A; Wellman, A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 188, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandedkar, NH; Chng, CK; Por, YC; Yeow, VKL; Ow, ATC; Seah, TE. Influence of Bimaxillary Surgery on Pharyngeal Airway in Class III Deformities and Effect on Sleep Apnea: A STOP-BANG Questionnaire and Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 75, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassing GJ, The V, Shaheen E, Politis C, de Llano-Pérula MC. Long-term three-dimensional effects of orthognathic surgery on the pharyngeal airways: a prospective study in 128 healthy patients. Clin Oral Investig. 2022:26:3131-3139. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S; Sutton, SR; Nguyen, SA; et al. Outcomes of maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) by dentofacial class: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025, 63, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K; Lee, RWW; Chan, TO; Ng, S; Hui, DS; Cistulli, PA. Craniofacial Phenotyping in Chinese and Caucasian Patients With Sleep Apnea: Influence of Ethnicity and Sex. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y; Yu, M; Gao, X. Role of craniofacial phenotypes in the response to oral appliance therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. J Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogisawa, S; Shinozuka, K; Aoki, J; et al. Computational fluid dynamics analysis for the preoperative prediction of airway changes after maxillomandibular advancement surgery. J Oral Sci. 2019, 61, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongsong, W; Waite, PD; Sittitavornwong, S; Schibler, M; Alshahrani, F. The correlation of maxillomandibular advancement and airway volume change in obstructive sleep apnea using cone beam computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 50, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author & Year | Study Type | Sample Size | Mean Age (years) | Gender | BMI (kg/m2) | SNA, SNB and Surgical movements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation 1: Maxillary and mandibular advancement | ||||||

|

Rossi et al 2019 (Patient 6) |

Retrospective Cohort | 1 | 47 | M | 30 | SNA: 75.9° → 81.6°, (Dx + 5.7°) SNB 79.3° →84.9°, (Dx +5.6°) Maxilla advancement not noted in mm, Mandible advancement 13.2mm |

|

Ronchi et al 2010 (Patients No.5 from group 1, No.5 and 6 from group 2) |

Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 26 | M | 24 | SNA: 73° → 89°, (Dx + 16°) SNB 79° →85°, (Dx +6°) |

| 62 | M | 27.1 | SNA: 80° → 85°, (Dx + 5°) SNB 80° → 84°, (Dx +4°) |

|||

| 54 | M | 31 | SNA: 82° → 91°, (Dx + 9°) SNB 82 → 88, (Dx +6°) |

|||

|

Brevi et al 2011 (Patients No. 1,6) |

Retrospective Cohort | 2 | 67 | M | 25.7 | SNA 79° → 86°, (Dx +7°) SNB 84° → 88° (Dx +4°) Movements not recorded in mm |

| 45 | M | 30 | SNA 75° → 85°, (Dx +10°) SNB 78° → 82°, (Dx +4°) |

|||

| Alsaty et al 2020 | Case Report | 1 | 55 | M | 25.6 | SNA 78.5° → 83.7°,(Dx +5.2°) SNB 78.8° →81.3°, (Dx +2.5°) Maxilla advancement 9mm, Mandible advancement 5mm |

|

Li et al. 2000 (Patients No.7,13,21) |

Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 47 | F | 56.0 | SNA 83° → 96°, (Dx +13°) SNB 83° → 88° (Dx +5°) |

| 17 | M | 41.5 | SNA 83° → 88°, (Dx+5°) SNB 84° → 87°, (Dx +3°) |

|||

| 48 | M | 42.1 | SNA 81° → 96° (Dx +15°) SNB 82°→ 93° (Dx + 11°) |

|||

| Variation 2: Maxillary advancement with mandible auto-rotation | ||||||

| Hoshijima et al 2015 | Case Report | 1 | 44 | M | NA | SNA 80.5° → 84.5°, (Dx+4.0°) SNB 80.5° → 82.0°, (Dx +1.5°) 3.0mm forward at ANS |

| Ishida et al 2019 | Case Report | 1 | 23 | M | 18.6 | SNA 74.6° → 77.8° (Dx +3.2°), SNB 77.1° → 77.1° (Dx 0) 4.5mm forward at ANS |

| Variation 3: Maxillary advancement and mandibular setback | ||||||

| Abdelwahab et al 2023 | Retrospective Cohort | 14 | 33.9 ± 10.2 | 13M, 1F | 26.9 ± 3.7 | Post-op SNA 80.69° Post-op SNB 82.72° Surgical movements not defined |

| Lu et al 2025 | Case Report | 1 | 24 | 1 M | 21.7 | SNA 86.1° → 88.6°(Dx +2.5°), SNB 88.6° → 88.1°(Dx -0.5°), Maxilla advancement 4mm & counterclockwise rotation of 5°, mandible setback 4mm & counterclockwise rotation of 6.5°, genioplasty advancement 7mm |

| Author & Year | AHI/RDI (Events/hr) | ESS | ODI (Events/Hr) | PAS (mm) | Complications | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Dx | Pre | Post | Dx | Pre | Post | Dx | Pre | Post | Dx | |||

| Variation 1: Maxillary and mandibular advancement | ||||||||||||||

| Rossi et al 2019 | 33.5 | 11.9 | -21.6 (64.48%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.21 | 16.5 | +7.29 | Nil | |

| Brevi et al 2011 | 24.2 | 7 | -17.7 (73.14%) |

8 | 8 | 0 | 32 | 5 | -28 | 7 | 10 | +3 | NA | |

| 87 | 14 | -73 (83.90%) |

13 | 0 | -13 | 84 | 9 | -75 | 8 | 15 | +7 | NA | ||

| Ronchi et al 2010 | 70 | 1 | -69 | 16 | 0 | -16 | NA | NA | NA | 8 | 14 | +6 | Worsened aesthetics | |

| 60 | 15 | -45 | 13 | 1 | -12 | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 10 | +6 | NA | ||

| 71 | 10 | -61 | 12 | 2 | -10 | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 12 | +7 | NA | ||

| Alsaty et al 2020 | 21.2 | 0.7 | -20.5 (96.70%) |

12 | 3 | -9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nil | |

|

Li et al 2000 |

44^ | 1^ | -43 (97.72%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 9 | +4 | Re-operation due to insufficient fixation | |

| 90^ | 9^ | -81 (90%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 8 | +5 | Nil | ||

| 77^ | 10^ | -67 (87.01%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 | 13 | +4 | Removal of mandibular implants due to localized irritation | ||

| Variation 2: Maxillary advancement with mandible auto-rotation | ||||||||||||||

| Hoshijima et al 2015 | 18.8 | 7.6 | 11.2 (59.6%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Ishida et al 2019 | 15.3 | 2.8 | 12.5 (81.70%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Variation 3: Maxillary advancement and mandibular setback | ||||||||||||||

| Abdelwahab et al 2023 | 37.17 ±35.77 |

11.81 ±15.74 | 25.36 (68.23%) p=0.41 |

10.23 ±4.38 | 4.22 ±3.07 | 6.01 P=0.006 |

11.43 ±11.40 | 5.44 ±7.96 | 5.99 P=0.828 |

NA | NA | NA | Nil | |

| Lu et al 2025 | 22.8 | 10.1 | 12.7 (55.7%) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nil | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).