1. Introduction

The Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a severe public health issue, resulting in high blood pressure, excessive daytime sleepiness and compromised quality of life [

1].

OSA is a common breathing disorder during the sleep characterized by snoring and recurrent collapse of the pharyngeal airway while sleeping, resulting in a partial reduction (hypopnea) or complete cessation (apnea) of airflow lasting at least 10 seconds. Most breaks last between 10 and 30 seconds, but some may persist for a minute or more [

2]. This can lead to sharp reductions in oxygen saturation in the blood, with oxygen levels that can decrease by up to 40% or more in severe cases. The central nervous system responds to the lack of oxygen with an alert mechanism, causing a short awakening from sleep that restores normal breathing. This pattern can occur hundreds of times in a single night. The result is a fragmented sleep that often produces an excessive level of daytime sleepiness [

3].

The interruption of breathing during sleep has many adverse health consequences including: cardiovascular diseases, collagenopathy, metabolic disorders and diabetes, psoriasis, kidney failure, ophthalmic diseases, chronic obstructive beoncopneumopathy (COPD), epilepsy, neoplasms, dementia [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This disorder is the product of a manifold interaction between anatomical factors (round airways, length and volume of the soft palate, length of the upper airways, pharyngeal fat deposits, adeno-tonsillar hypertrophy, tongue volume, class II skeletal profile and morphological deviations of the cervical spine), sleep-related factors and central nervous system control over ventilation [

9].

The prevalence of OSA was assessed to be approximately 7 to 14% for adult men and 2 to 5% for adult women in a population-based study that used a cutoff of AHI ≥ 5 events/h (hypopneas associated with oxygen desaturations of 4%) associated with clinical symptoms to define OSA [

10]. The most represented category of patients with OSAS are male individuals, obese and aged 65 or older. Unfortunately, OSA is still an under-diagnosed medical condition and more than 85% of patients with clinically significant OSA are never diagnosed [

11].

Medical history and objective examination are the first step of clinical diagnosis. Patients should be questioned about both their nighttime and daytime symptoms, and the partner interview can provide important information about the patient's sleep. The diagnosis of OSAS is confirmed by: presence of excessive daytime drowsiness, not attributable to other conditions, in association with at least five apnoic events per hour of sleep; or two symptoms between suffocation during sleep, recurrent awakenings, unrefreshing sleep, daytime drowsiness and decrease in concentration, not attributable to other conditions, in association with five apnoic events per hour of sleep; or the presence of at least fifteen apnoic events per hour of sleep, regardless of the above symptoms [

12].

Polysomnography is the gold standard test for the diagnosis of OSA in adult patients in whom there is a concern for OSA based on a comprehensive sleep evaluation. It indicates a simultaneous recording of several physiological parameters during the night, for the evaluation of the physiological and pathological phenomena that may occur while sleeping [

11]. OSAS is classified in three degrees of severity according to the AHI index (Apnea-Hypopnea Index), corresponding to the number of episodes of apnea and/or hypopnea per hour of sleep registered by polisomnography. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is defined as:

- -

MILD if AHI is between 5 and 15 episodes per hour of sleep;

- -

MODERATE if AHI is between 15 and 30 episodes per sleep hour;

- -

SEVERE if AHI is greater than 30 episodes per hour of sleep.

OSA management requires a long-term multidisciplinary approach. Therapeutic choices include lifestyle changes, drug therapies, mechanical or surgical therapies. Mandibular advancement devices (MAD) are the gold standard therapy for mild/moderate OSA and a second-choice treatment in patients with severe OSA who do not comply or do not respond to CPAP [

13]. In particular, MADs interfere with the mandible and tongue, the pharyngeal dilator muscles and, indirectly, the soft palate. By displacing the mandible forward, these structures that constitute the lumen of the oropharynx are also stretched forward, increasing upper airway space and reducing the collapsibility of the pharynx [

14]. According to the possibility of modifying the occlusal relationship, the MAD are divided into two categories, titratable and not titratable. The titrators have a mechanism that allows to increase the degree of advancement of the jaw during the course of therapy. Therapy with advancing jaws has a beneficial effect on cardiovascular comorbidities, endothelial function and cognitive and psychomotor performance [

15,

16,

17]

Over the years, different imaging modalities were proposed to directly describes the status of upper airway and determine the risk of OSA and, on the other hand, the effectiveness of MAD to increase the airway space. Several studies in the literature have tried to define the role of cephalometric skeletal models in identifying the predisposition to generate the syndrome.

Cone Beam Computer Tomography (CBCT), with its low effective radiation dose and low scanning time (10-70 seconds), represents an effective technique for a 3D complete evaluation, using a large field of view protocol, for a comprehensive head and neck evaluation [

18]. Although CBCT does not allow to discriminate between different soft tissue structures, it is still possible to define the boundaries between soft tissue and empty spaces (i.e. air), which means that CBCT is a potential tool for analyzing and solving the problem of 3D airway analysis [

19].

According with the most recent researches on OSA and 3D airway analysis upper airway area is one of the most common measurements to assess the upper airway in OSA patients, and some airway measures correlate with the presence and severity of OSA a high chance of severe OSA was noticed in patients with an upper airway area less than 52mm2 an intermediate chance with an upper airway area between 52mm2 and 110mm2, and a low chance with an upper airway area larger than 110mm2 [

20]. Furthermore, there are no studies comparing more than two different type of MAD and their effects on airway changes.

The aim of this research was to analyze the upper airway characteristics of OSA patients and the morphological changes in the oropharynx airway, inducted by four different types of mandibular advancement devices, using CBCT 3D imaging.

2. Materials and Methods

On the basis of pharynx volumetric data of a sample of 8-year-old children provided by Mostafiz et al [

20], with a power set at 0.8, an effect size at 0.5 and a significance level at 0.05, 22 subjects were enrolled.

This study followed the principles laid down by the World Medical Assembly in the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 on medical protocols and ethics and it was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Rome “Tor Vergata” (protocol number 0015966/2019). Written consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study.

Therefore the study group was composed of 22 OSA patients, aged between 30 and 70 years old. Specialists in sleep medicine referred all patients, after a nocturnal polysomnography test and a diagnosis of OSA. The diagnosis of OSA was based on recognised criteria, including an apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) of >5 per hour during sleep [

2].

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age > 18 years; first-line treatment for moderate OSA with mild to moderate daytime sleepiness and without severe cardiovascular comorbidities OR second-line treatment for moderate to severe OSA after intolerance or refusal of positive airway pressure therapy; signed informed consent. Patients with central apnoea index > 5/h; severe sleep comorbidities other than OSA; any contraindication for MAD evaluated by a dental specialist investigator (periodontal disease, less than 10 teeth in both dental arches), history of temporomandibular disorders such as pain and limited opening to less than 40 mm; a coexisting psychiatric or neuromuscular condition that could affect compliance; presence of occupational hazards such as professional drivers; and pregnant or lactating women were excluded from the study.

For each subject, the following information were recorded: age, gender, BMI and ethnicity. More over every participant responded to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Four customized and titrabled MAD, registered with the Gorge Gauge with an initial mandibular advancement of 60% maximal jaw protrusion without muscular pain for patients was used and the titration was adjusted at subsequent visits. The devices chosen are among the most used in OSA therapy.

For each patient, after establishing the diagnosis of OSAS through PSG and the therapeutic indication for the MAD, a CBCT was performed and the impressions were taken for the manufacture of the MAD. After delivery of the MAD and good adaptation of the patient to the device was established, the titration process was started. Once the titration process was accomplished, follow-up visits were planned. The same process was employed for each MAD device in order to align the level of mandibular advancement when the titration phase was completed. At the follow-up visit, a clinical examination was performed to assess OSA symptoms, compliance and side effects.

During the titration phase, of the 22 participants in this study, 3 patients had slight symptoms of TMJ. For these patients, titration was slowed down to enable slow and progressive adaptation to the device. At the end of titration and subsequent monitoring, no patients showed any signs or symptoms of TMJ. The titration phase ends when the patient shows a significant reduction in symptomatology (supported by ESS score) in the absence of TMJ signs or symptoms. A second PSG with the MAD in situ was performed at the end of the titration step.

Therapeutic effect of MAD was judged positive when showed an AHI of < 5 or a decrease of 50% in AHI in the presence of MAD when compared with AHI changes in the absence of MAD.

The MAD used for each subject were randomly chosen. All the subjects of sample reached excellent therapeutic results. After 6 months to the end of the titration phase a second CBCT scan with MAD in situ was performed. The MAD selected for the study was chosen as representative of the different types of MAD most commonly used by the clinicians and best described in the literature. These MAD, actually, differ from one another for different materials for construction, protruding mechanism, anchoring mechanism, titratable mood and vertical dimension.

The characteristics of the MAD used, were summarised in

Table 1.

The Silensor SL device is composed by two thermoformed splints covering the upper and lower arch respectively. These two plates are connected by a fixed joint, in the upper part at the level of the canine and in the lower part at the level of the lower first and second molars. Direction of the connector enables the movement of the mandibular protrusion to be defined.

The inter-incisal gap between the two plates is between 2-4 mm. This device is provided by six connectors with 1 mm increment lengths. This device additionally enables limited lateral and opening movements of the mouth. In this study, 5 subjects used Silensor SL MAD.

The TAP device that consist of two acrylic plates that cover the upper and lower arch, respectively. These two splints are joined by an anterior traction: a fixed mechanical hinge and inseparable pivot. The fixed hinge is connected with an advancer screw with allows 7 mm of maximum elongation. Screw activation allows very small and precise increments. Each complete activation produces 0.25 mm advancement. Interincisal distance between the two plates between 4-6 mm. This device also allows wide laterality movement but no mouth opening movements. Six subjects of initial sample were randomly selected for this MAD.

The TELESCOPIC ADVANCER DEVICE consists of two fitted acrylic plates joined by a lateral connectors composed of a tube and piston mechanism (called Herbst attachments) with the possibility of adjusting the protrusion very accurately; each ¼ activation produces 0.1 mm advancement with 7 mm of maximum elongation. Interincisal distance between the two plates between 6-8 mm. This device also allows wide laterality and opening movements.

From the initial sample 5 subjects were selected to use TELESCOPIC ADVANCER DEVICE.

The FORWARD device consist of two fitted acrylic plates connected by buccal flanges with a metal core angled at 70°. The screw mechanism with an in-built stop present in the upper plate allow 7 mm of maximum elongation with 0.1 mm increments. Vertical opening between the two plates between 6-8 mm. This device also allows limited opening and no mouth laterality movements.

From the initial sample 6 subjects were selected to use FORWARD MAD device.

All CBCT examinations will be performed with NewTom VGi EVO unit (NewTom 3G, QR s.r.l.; AFP Imaging, Elmsford, NY, USA). Each patient was placed upright and seated, and the head was fixed such that the Frankfurt plane was parallel to the floor, teeth into occlusion, avoid tongue movements, without swallowing or respiratory movements during inspiration at rest. All CBCT acquisitions were made by the same operator Two scans were obtained the first one (T0) before the therapy and the second after 6 months to the end of the titration phase with MAD in situ (T1)

Figure 1. The CBCT images were exported as DICOM files (.dcm) and then imported into the airway analysis software programme. A coding system was used to anonymise the data.

To check the accuracy of the measurements, 7 patients were randomly selected, whose images were re-analyzed after an interval of 14 days by the same operator; the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used for statistical analysis of the difference between the duplicate measurements. The agreement between the measurements was substantial (Kappa > 90).

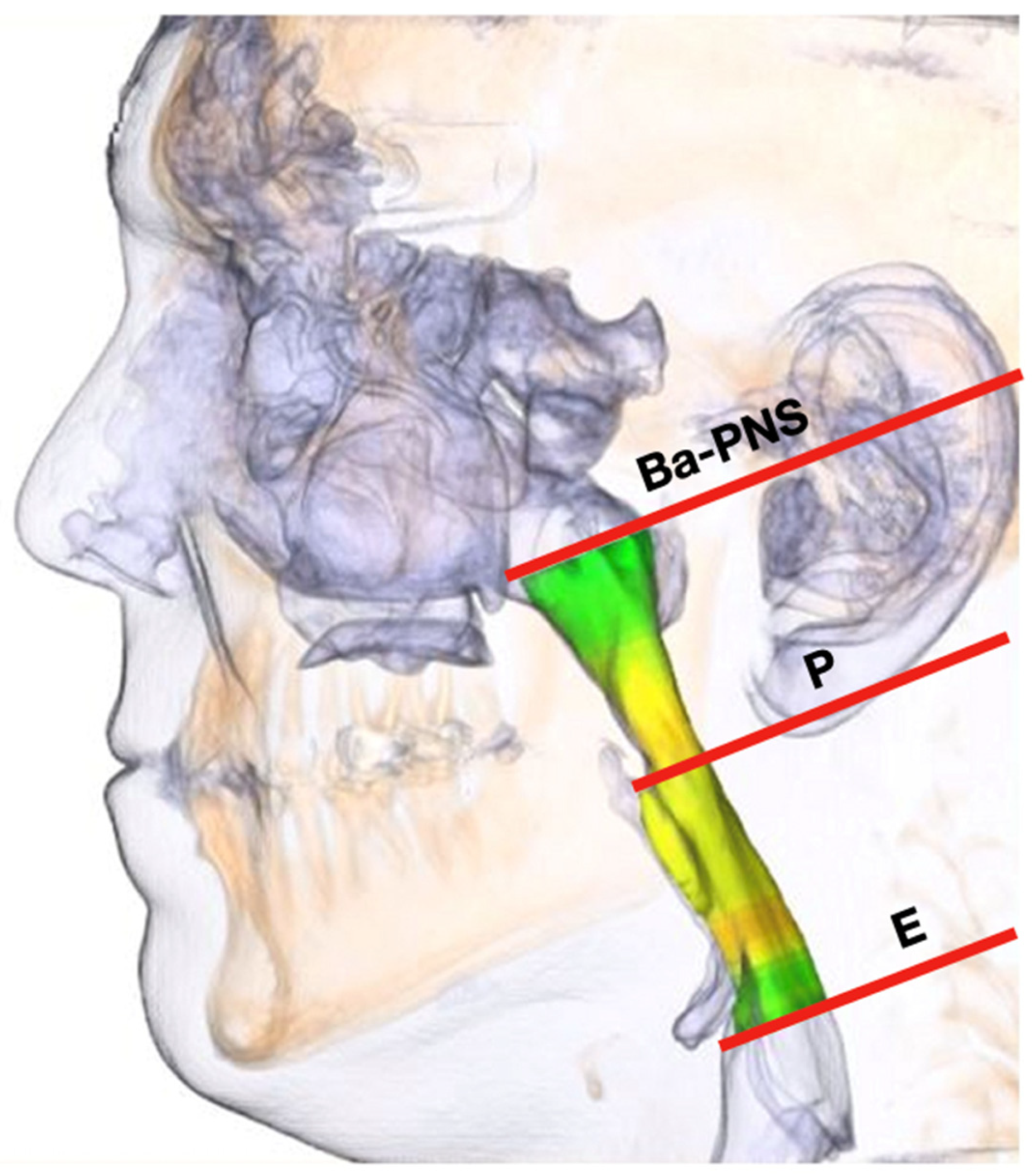

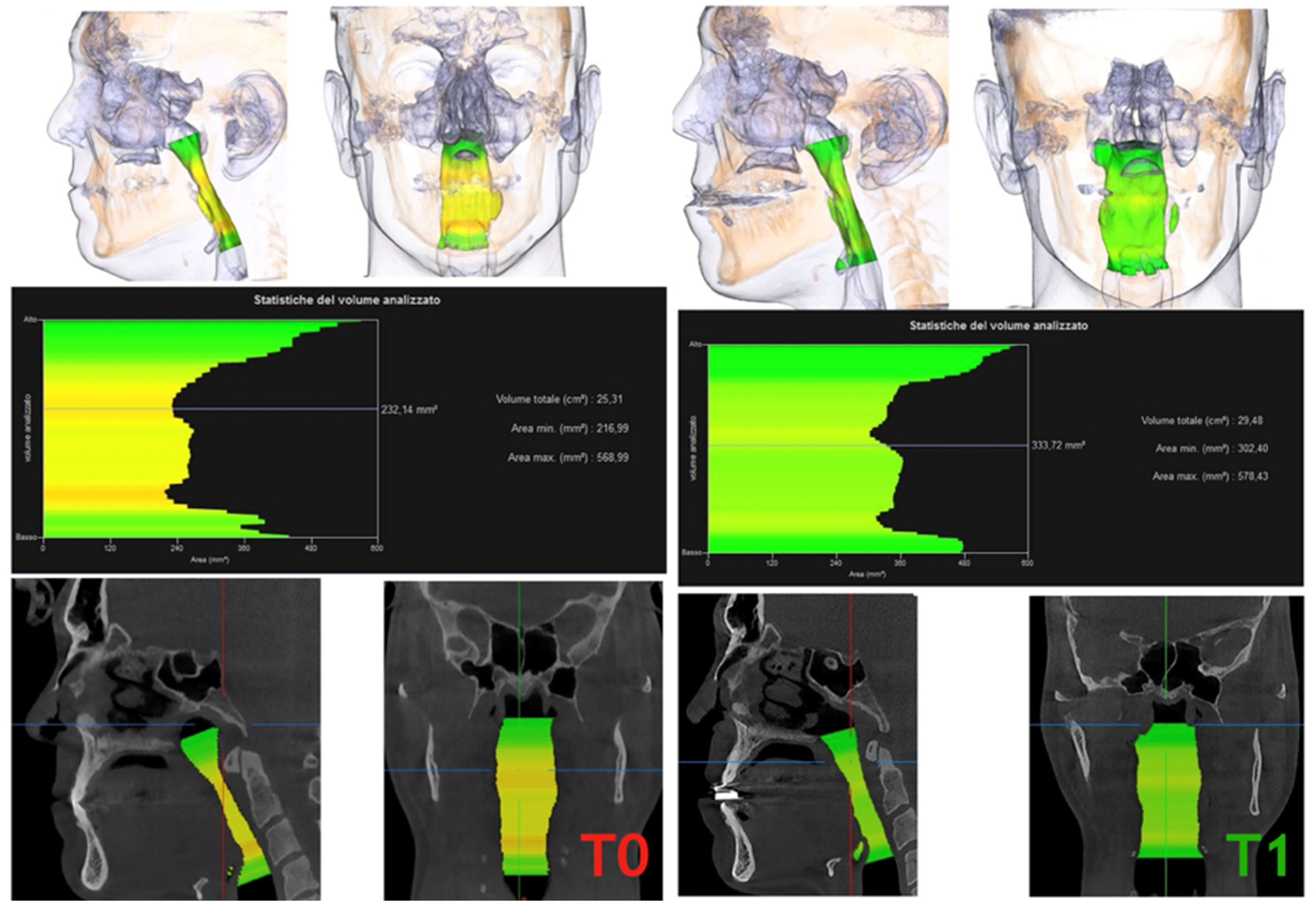

After the PAS segmentation process, the three-dimensional models were cut out. The pharyngeal area around the oropharynx, where the origin of the apneas is mainly located, was considered.

The plane between the base point (Ba) and the posterior nasal spine point (PNS) represented the cranial margin of the PAS. The caudal margin was described as a plane parallel across the tip of the epiglottis (E). All PAS models were divided into an upper and a lower part by a parallel plane passing through the lowest point of the soft palate (P).

Noise in the airway slices was minimized while airway volume was selected.

To measure the area and volume of the oropharynx with and without the device, it had to be divided into 2 parts: the posterior soft palate airway (Ba - PNS - P) and the posterior tongue oropharynx (P - E)

Figure 2.

The cross-section evaluation was carried out on the upper and lower shear surface of the three-dimensional PAS models. Once the corresponding cut surface was marked, the software calculated the exact cross-sectional area.

In addition, the volume of the imported three-dimensional PAS models (upper and lower PAS) was calculated completely automatically (

Figure 3).

All the measurements of the airway were performed by a study co-investigator, who was blinded to the subject's apnoea condition and was evaluated for reliability with repeated measurements for n =10 after 1 week under the same conditions. Inter-rater reliability was also evaluated for n =10 by a second co-investigator of the study.

2.1. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

A summary of all parameters was made in terms of averages, standard deviations and ranges. Comparison of the means of each parameter before and after treatment was conducted using paired t tests assuming the normality of the data. In addition, the relationship between AHI and different parameters was assessed using Pearson's correlation analysis. The statistical significance was evaluated at the 5% level.

3. Results

The sample was composed of 22 OSA patients (13 M, 9 F). The mean age of the patient sample was 54 (+/- 7.7) years old, with an average body mass index (BMI) of 27 (+/- 4.3) kg/m2.

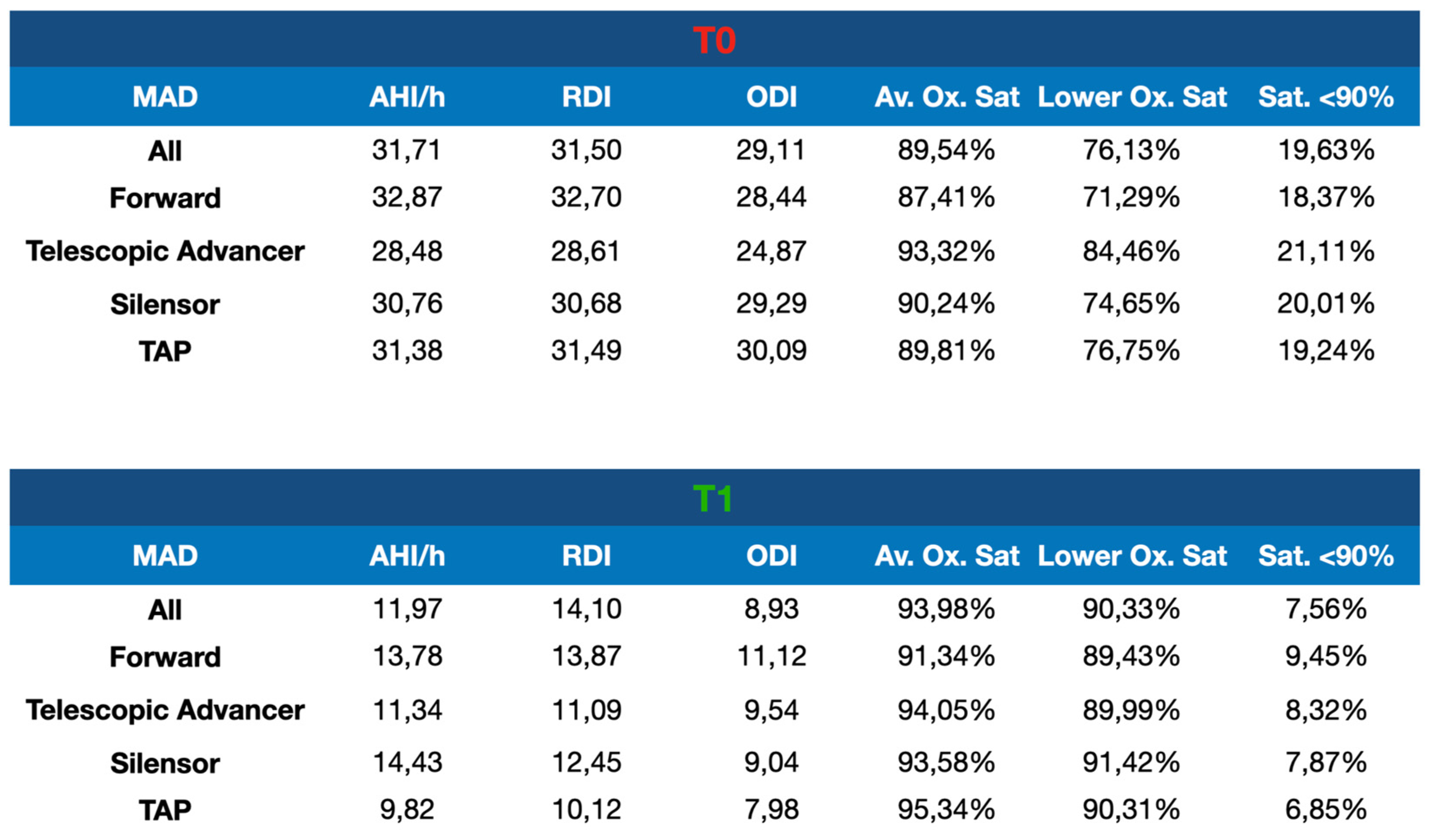

At the baseline, the average AHI/h was 31.7/h (+/- 9.8). The MAD was well tolerated by all patients. No significant differences were observed in the severity, frequency or duration of reported side effects between devices. At the end of the titration period, there were no significant differences in mandibular protrusion between the different four MAD device (mean elongation 6.3 +/- 1.3 mm). The mean AHI/h with MAD in situ was 11.97 (+/- 12.8). Concerning the different types of devices, it can be noted that, from a polysomnographic point of view, the results overlap almost with all the devices used

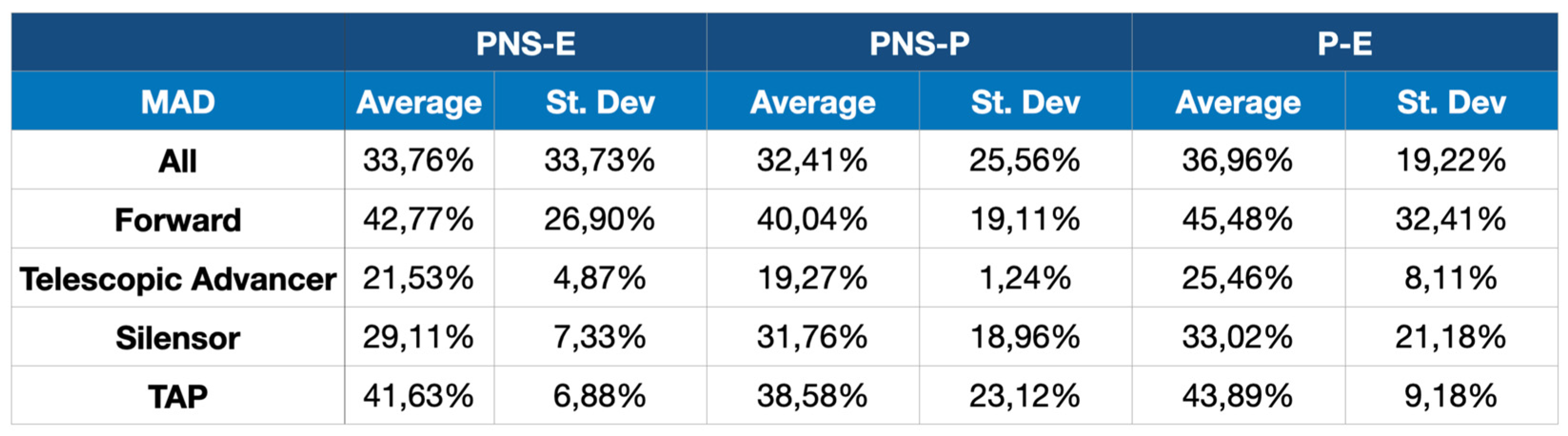

Table 2. Compared to baseline, oropharyngeal airway volume increased substantially with all devices, on average of 36.96% +/- 19.22%, p = 0.003. In relation to the different type of device it is possible to note that with the use of MAD Forward an average variation oropharyngeal airway volume of 45.48% is obtained; with the TAP the achievement of 43.89%, Silensor the mean increase was 33.02%, finally, with the Telescopic Advancer the effectiveness is lower with an average increase of 25.46%

Table 3.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to observe differences in efficacy between four types of custom-made titratable MADs. Our study, according to the most recent review, demonstrated significant results in terms of respiratory indexes and oropharyngeal airway volume with all types of MAD [

21]. The optimum vertical dimension and mandibular protrusion of an oral appliance required to achieve a successful treatment outcome in patients with OSA has been an issue of debate. Gupta et al. [

22] in his work analyzed four different non treatable MAD (60% of protrusion and 4 mm of vertical opening, 60% of protrusion and 6 mm of vertical opening, 70% of protrusion and 4 mm of vertical opening, 70% of protrusion and 6 mm of vertical opening) evaluating respiratory indexes and assumed that the best configuration was 70% of protrusion and 4 mm of vertical opening. In the present study, only titratable MAD were analyzed and even if the initial mandibular protrusion was at least 60% of the maximum protrusion, the final position of the MAD was reached by increasing the protrusion to the maximum value tolerated by the patient in the absence of muscle pain and this made it possible to obtain a clear improvement in respiratory indexes for all patients. The debate about how the vertical dimension can influence the effectiveness of MAD is even more heated.

Pitsis et al. [

23] made a comparison of the effects of two MAD setups (4 mm vs. 12 mm opening, both with similar mandibular protrusion). No significant differences in treatment efficacy were reported, but patient compliance was higher for the device with the smaller interincisal opening.

In contrast Ye Min Soe and coworkers [

24] suggest that the increased vertical distance between the maxilla and mandible due to the appliance affect the exacerbation of the respiratory status during sleep.

The vertical dimension of the devices we use, ranging from 2 to 8 mm, did not significantly affect the polysomnographic results and oropharyngeal volumes achieved at the end of the titration.

Regarding the protruding mechanism, which mainly differentiates the MADs used in this study, the results showed better polysomnographic and volumetric results for MAD Forward and TAP compared to Silensor and Telescopic advancer.

The optimal criteria for the construction of a MAD that can achieve the best therapeutic results are the subject of wide discussion in the literature. As for the mandibular protrusion in the literature, numerous studies propose a protrusive that varies between 60 and 80% of the maximum protrusive of the patient but there is no agreement on a value that can be optimal. In our study, the initial protrusive was 60% each, but the final position was achieved by progressive progression through MAD titration. We can say that, as stated in the literature, the best degree of progress is the maximum achievable in the absence of pain or discomfort muscle or joint for the patient [

25,

26].

Several studies have highlighted the superiority of bi-block MADs over mono-blocks [

27] and customized MADs over prefabricated MADs [

28] but, to our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature comparing the different types of MAD protrusion mechanism. The best results have been highlighted with the use of MAD whose protrusion mechanism allows adequate and constant support of the jaw and soft tissues even during the natural mandibular movements that can occur during the night. In particular, the Forward device, with its long buccal fins, allows the maintenance of the protruded position of the jaw even during the small movements of the mouth, avoiding a posterior mandibular rotation that would reduce the volume of the airways. The TAP, with its front hooks, prevents any opening movement of the jaw. Finally, the Telescopic advancer and the Silensor do not have any mechanism that prevents the opening and post-rotation of the jaw. It will be interesting to reassess these long-term CBCT outcomes with 5- and 10-year follow-ups. This would make it possible to understand if, with the same initial satisfactory clinical results, a greater increase in oropharyngeal volumes can reduce the incidence of recurrence of the disease by supporting soft tissues more effectively. As described in the literature from the few long-term studies present, the long-term use of MAD by patients depends on its tolerability and the dental effects that determine over the years .

In literature, only a few studies compared the effects of different MADs on upper airway volume using three-dimensional imaging. Suga et al. compared two MADs (one semi-rigid and one rigid devices) and reported no significant differences in upper airway volume with either device examined [

29]. Most studies that compared two or more MADs, have evaluated polysomnographic [

30] and cephalographic [

31] parameters as primary findings. Lateral cephalograms offer a two-dimensional assessment of upper airway anatomy. The main limitation of cephalograms is that they only allow anteroposterior comparisons of the upper airway.

By using this imaging procedure, Brown et al. found that MADs primarily increase pharyngeal lateral dimensions [

32]. Cone beam computed tomography delivers three-dimensional images and a more accurate overview of the upper airway that is [

33].

Because no scientific research study is perfect, this study has its limitations. The CBCT images were not taken in supine position but in the upright position and the patients were awake. The results are limited in some ways, first in the acquisition of images. The position of the head and the phase of respiration cannot be controlled completely. As the upper air-way is a dynamic organism, variations in respiratory artefacts, swallowing, and the position of the head may affect the measurements. Despite thorough and exact indications before the cone-beam CT scan, these biases must be taken into account. Another limitation is related to the sex of patients. A larger proportion of male to female patients can skew results. The final limitation is the small number of participants. A long-term prospective study with a large number of patients would be desirable to investigate MAD-inducted changes in the posterior airway space in more detail.

5. Conclusions

All the customised and titratable MADs analysed allowed for significant improvement of the polysomnographies indexes in patients with mild to severe OSAS. So we can affirm that customised and titrable MAD is a valid therapeutic option for the treatment of OSAS. Careful patient selection and a careful titration protocol with progressive increments, help to achieve optimal clinical outcomes while maintaining patient compliance and avoiding side effects.

The type of MAD Forward, consisting of acrylic plates supported by angled side flanges, and the type of MAD TAP, consisting of acrylic plaques joined by an anterior traction, resulted in a greater increase in the volumetric size of the oropharynx.

The vertical dimension of the MAD does not significantly influence the effectiveness of the treatment with an adequate mandibular protrusion. However, it is recommended not to exceed the 8 mm of interincisal opening to facilitate better acceptance of the device by the patient.

The results of this study show that CBCT is an important test for the diagnosis and treatment choice of OSA patients. The authors recommend the evaluation of CBCT images, including the calculation of respiratory tract measurements, as part of the overall assessment.

Future CBCT studies on the incidence of recurrence and soft tissue adaptation after prolonged use of MAD are desirable to assess whether, with the same initial satisfactory clinical results, mandibular advancement devices that leads to a greater volumetric increase of the airways are more effective in counteracting phenomena of recurrence of pathology.

Author Contributions

NV and CL performed the experimental analysis and analyzed the data, AM contributed to write the manuscript. GL supervised the project and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study followed the principles laid down by the World Medical Assembly in the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 on medical protocols and ethics and it was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Rome “Tor Vergata” (protocol number 0015966/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kuhn, E.; Schwarz, E.I.; Bratton, D.J.; Rossi, V.A.; Kohler, M. Effects of CPAP and Mandibular Advancement Devices on Health-Related Quality of Life in OSA: A Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Chest 2017, 151, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep 1999, 22, 667–689.

- Singh, A.; Meshram, H.; Srikanth, M. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Guidelines, 2018. Int J Head Neck Surg 2019, 10, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iber, C.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Chesson, A.; et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed., Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007.

- Venza, N.; Alloisio, G.; Gioia, M.; Liguori, C.; Nappi, A.; Danesi, C.; Laganà, G. Saliva Analysis of pH and Antioxidant Capacity in Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, G.; Venza, N.; Malara, A.; Liguori, C.; Cozza, P.; Pisano, C. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Palatal Morphology, and Aortic Dilatation in Marfan Syndrome Growing Subjects: A Retrospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, G.; Osmanagiq, V.; Malara, A.; Venza, N.; Cozza, P. Sleep Bruxism and SDB in Albanian Growing Subjects: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent J (Basel). 2021, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azagra-Calero, E.; Espinar-Escalona, E.; Barrera-Mora, J.M.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M.; Solano-Reina, E. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012, 17, 925–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susarla, S.M.; Thomas, R.J.; Abramson, Z.R.; Kaban, L.B. Biomechanics of the upper airway: changing concepts in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 39, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Adachi, T.; Koshino, Y.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2009, 73, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Mannarino, M.R.; Di Filippo, F.; Pirro, M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2012, 23, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lenza, M.G.; Lenza, M.M.; Cattaneo, P.M. An analysis of different approaches to the assessment of upper airway morphology: a CBCT study. Orthod Craniofac. 2010. pp. 96–105.

- Sutherland, K.; Vanderveken, O.M.; Tsuda, H.; Marklund, M.; Gagnadoux, F.; Kushida, C.A.; Cistulli, P.A. Oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: an update. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Wang, H.Y.; Chiu, C.H.; Liaw, S.F. Effect of oral appliance on endothelial function in sleep apnea. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2014, 19, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Haesendonck, G.; Dieltjens, M.; Kastoer, C.; Shivalkar, B.; Vrints, C.; Van De Heyning, C.M.; Braem, M.J.; Vanderveken, O.M. Cardiovascular beneMits of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine 2015, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Galic, T.; Bozic, J.; Pecotic, R.; Ivkovic, N.; Valic, M.; Dogas, Z. Improvement of cognitive and psychomotor performance in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea treated with mandibular advancement device: a prospective 1-year study. J Clin Sleep Med 2016, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsufyani, N.A.; Al-Saleh, M.A.; Major, P.W. CBCT assess- ment of upper airway changes and treatment outcomes of obstructive sleep apnoea: a systematic review. Sleep Breath. 2013, 17, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, U.; Cohen, J.R.; Al-Samawi, Y. Use of cone beam computed tomography imaging for airway measurement to predict obstructive sleep apnea. Cranio. 2020:1-7.

- Mostafiz, W.R.; Carley, D.W.; Viana, M.G.C.; Ma, S.; Dalci, O.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Evans, C.A.; Kusnoto, B.; Masoud, A.; Galang-Boquiren, M.T.S. Changes in sleep and airway variables in patients with obstructive sleep apnea after mandibular advancement splint treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2019, 155, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzaman, A.S.M.; Gersh, B.J.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA. 2003, 290, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Tripathi, A.; Trivedi, C.; Sharma, P.; Mishra, A. A study to evaluate the effect of different mandibular horizontal and vertical jaw positions on sleep parameters in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Pitsis, A.J.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Gotsopoulos, H.; Petocz, P.; Cistulli, P.A. Effect of vertical dimension on efficacy of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye Min Soe, K.T.; Ishiyama, H.; Nishiyama, A.; Shimada, M.; Maeda, S. Effect of Different Maxillary Oral Appliance Designs on Respiratory Variables during Sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Tripathi, A.; Trivedi, C.; Sharma, P.; Mishra, A. A study to evaluate the effect of different mandibular horizontal and vertical jaw positions on sleep parameters in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manetta, I.P.; Ettlin, D.; Sanz, P.M.; Rocha, I.; Meira ECruz, M. Mandibular advancement devices in obstructive sleep apnea: an updated review. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Ellah, M.E.; Mohamed, F.S.; Khamis, M.M.; Abdel Wahab, N.H. Modified biblock versus monoblock mandibular advancement appliances for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. J Prosthet Dent. 2022: S0022-3913(22)00144-5.

- Manetta, I.P.; Ettlin, D.; Sanz, P.M.; Rocha, I.; Meira ECruz, M. Mandibular advancement devices in obstructive sleep apnea: an updated review. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, H.; Mishima, K.; Nakano, H.; Nakano, A.; Matsumura, M.; Mano, T.; et al. Different therapeutic mechanisms of rigid and semi-rigid mandibular repositioning devices in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg 2014, 42, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, K.E.; Iseli, A.; Zhang, J.N.; Xie, X.; Kaplan, V.; Stoeckli, P.W.; et al. A randomized, con- trolled crossover trial of two oral appliances for sleep apnea treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, F.; Ahrens, A.; McGrath, C.; Heagg, U. An evaluation of two different mandibular advancement devices on craniofacial characteristics and upper airway dimensions of Chinese adult obstructive sleep apnea patients. Angle Orthodont 2015, 85, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.C.; Cheng, S.; McKenzie, D.K.; Butler, J.E.; Gandevia, S.C.; Bilston, L.E. Tongue and lateral upper airway movement with mandibular advancement. Sleep 2013, 36, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashina, A.; Tanimoto, K.; Sutthiprapaporn, P.; Hayakawa, Y. The reliability of computed tomography (CT) values and dimensional measurements of the oropharyngeal region using cone beam CT: comparison with multidetector CT. Dento Maxillo Fac Radiol 2008, 37, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).