1. Introduction

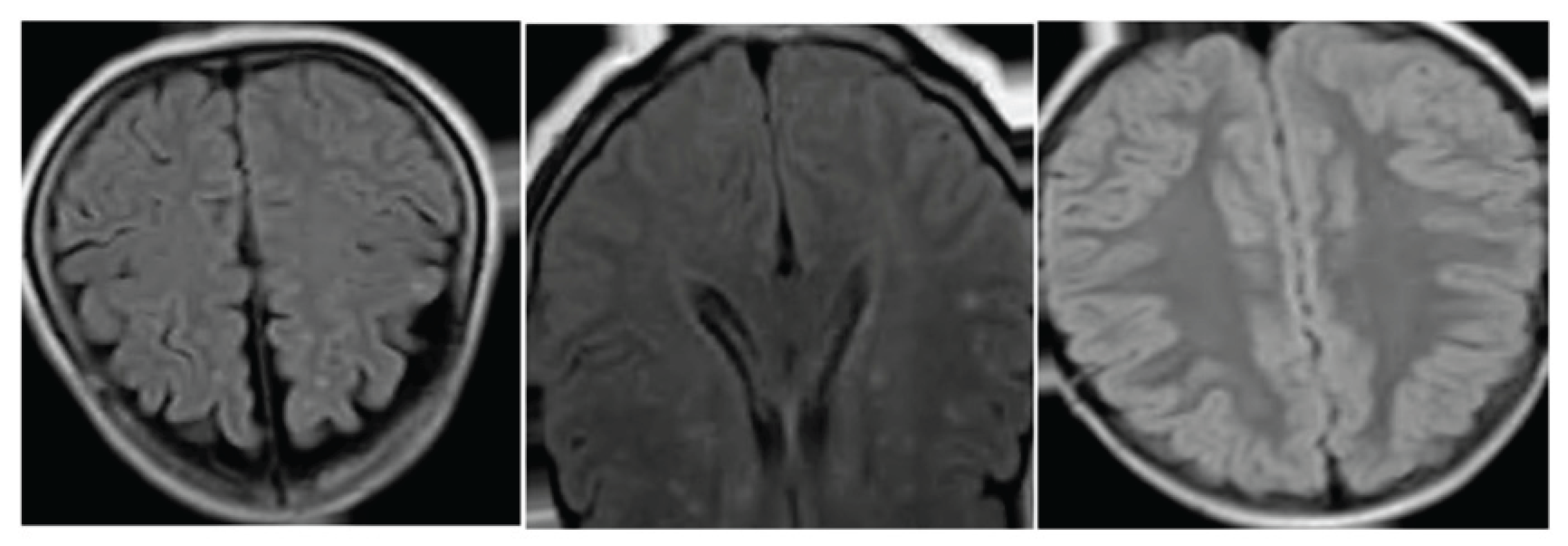

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are common findings on T2-weighted and FLAIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in ageing populations and patients with cerebral small vessel disease. They are strongly associated with cognitive decline, gait impairment, stroke risk, and dementia, and are widely used as imaging markers of vascular brain injury [

1,

2]. Both the overall WMH burden and their spatial distribution provide clinically meaningful information for risk stratification and disease monitoring. However, accurate automatic segmentation of WMH remains challenging due to substantial variability in image contrast across scanners and acquisition protocols, as well as pronounced inter-individual differences in lesion appearance. Recent studies further indicate that explicitly emphasizing lesion cores and learning structured representations can improve robustness in brain lesion segmentation under low-contrast conditions, highlighting the value of spatially informed modeling strategies [

3]. Clinically, WMH are often divided into periventricular (PV) and deep white matter regions. Although this distinction is commonly defined by the distance to the ventricular system, it also reflects underlying biological and pathological differences. PV and deep WMH exhibit distinct morphological characteristics, growth patterns, and associations with vascular risk factors. PV lesions tend to form larger, confluent clusters that expand along the ventricular border, whereas deep WMH often appear as small, isolated, and spatially scattered lesions [

4]. These differences suggest that WMH should not be treated as a single homogeneous class and that region-aware modeling may be essential for accurate segmentation and interpretation.

Traditional WMH segmentation tools, such as intensity-based or probabilistic methods that combine voxel intensity with simple spatial cues, have been widely used in clinical research [

5]. Representative examples include pipelines that rely on tissue priors or distance-based heuristics. While these approaches perform reasonably well when imaging protocols are stable, their accuracy degrades noticeably when image quality varies or when applied across centers with different scanners and acquisition settings. Reviews of the literature further note that many studies rely on relatively small datasets and lack comprehensive cross-center validation, which limits the generalizability of reported results [

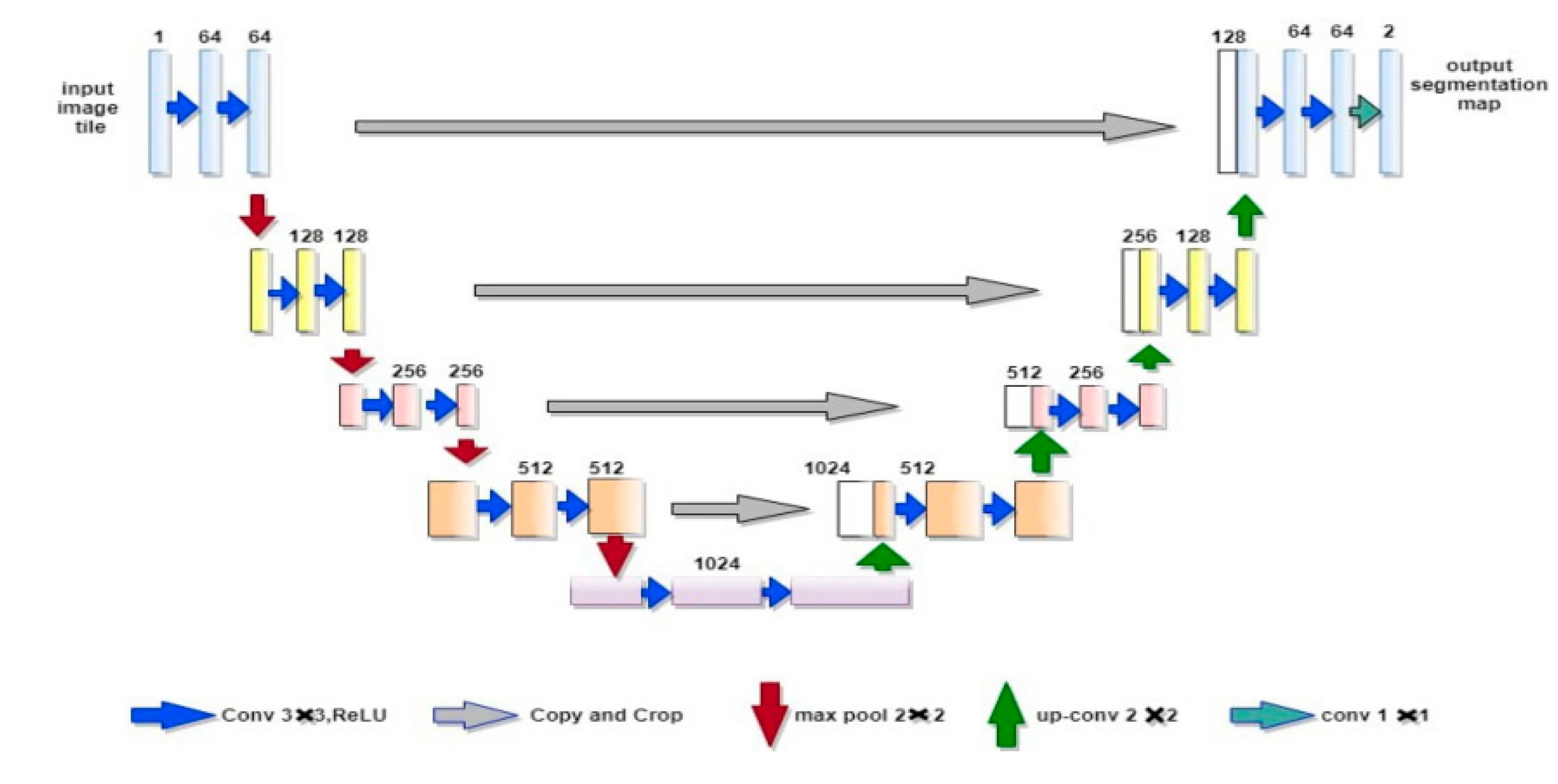

6]. Deep learning has substantially advanced WMH segmentation by enabling models to learn richer feature representations from large-scale datasets such as WMH2020. Most contemporary methods are built on U-Net–style encoder–decoder architectures and incorporate multi-scale feature extraction, auxiliary supervision, or semi-supervised learning to improve sensitivity to small lesions [

7,

8]. Despite these advances, the majority of deep learning models still rely primarily on local intensity and texture information. Spatial context is often introduced only implicitly or through simple distance-to-ventricle maps appended as additional input channels. As a result, many models do not explicitly account for the distinct spatial distributions and morphological differences between PV and deep WMH, even though these regions exhibit markedly different lesion patterns.

Several studies have attempted to integrate anatomical priors into deep learning frameworks by incorporating atlas-based probability maps, tissue masks, or handcrafted spatial features [

9,

10]. These additions can help suppress false positives in anatomically implausible regions and improve overall segmentation quality. However, most such priors are fixed and derived from relatively small cohorts, which may not adequately capture the full variability of PV and deep WMH distributions in large, heterogeneous populations. Moreover, commonly used attention mechanisms in medical image segmentation are generally data-driven and do not explicitly encode region-specific anatomical knowledge, limiting their effectiveness for WMH-specific tasks [

11]. Accurate detection of small, deep WMH remains one of the most persistent challenges. These lesions often exhibit low contrast, irregular shapes, and very small spatial extent, making them difficult to distinguish from noise or normal white matter variations. Multiple studies report substantially lower Dice and intersection-over-union scores for deep lesions compared with PV lesions [

12]. Importantly, many evaluations focus exclusively on whole-WMH performance, which can obscure poor sensitivity in deep regions and mask clinically relevant segmentation errors [

13].

This study proposes SPAN-WMH, a Structural-Prior Attention Network for region-aware WMH segmentation. The proposed framework learns probabilistic structural priors that capture the characteristic spatial distributions of WMH in periventricular and deep white matter regions. These learned priors are integrated into a spatial attention module that modulates feature responses according to anatomical context, enabling the model to adaptively emphasize region-relevant information. This design aims to improve segmentation accuracy in both PV and deep regions, reduce boundary errors, and enhance sensitivity to small deep lesions. We evaluate SPAN-WMH on a large WMH2020 cohort comprising 1100 subjects and conduct region-specific analyses for PV and deep WMH, with particular focus on Dice score, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance (HD95), and small-region intersection-over-union. The results demonstrate that incorporating learned structural priors into attention mechanisms provides a robust and effective strategy for region-aware WMH segmentation in heterogeneous clinical MRI data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Study Area

This study used MRI data from 1100 subjects in the WMH2020 dataset. Each subject had T1-weighted and FLAIR scans collected under routine clinical settings. All images were aligned to the same orientation and covered the whole brain. The dataset included subjects with different ages and vascular risk levels, ensuring a wide range of WMH patterns. Scans with missing slices or strong motion were removed to keep the data quality stable.

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Groups

The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing, with no overlap between groups. The training group was used to learn both the structural priors and the attention module. The test group was used to evaluate performance. To examine the role of structural priors, we trained a baseline model without priors or region-aware attention. This allowed us to compare the proposed method with a simpler design. Performance was assessed separately in periventricular and deep white matter to show differences between regions.

2.3. Measurement Procedures and Quality Control

All scans were checked for correct orientation, brain coverage, and intensity variation. Expert-labeled WMH masks were used as the reference. Before training, all scans were resampled to 1 mm³ resolution and normalized with a simple percentile-based scaling method to reduce scanner-related differences. A second check ensured that T1 and FLAIR images stayed aligned after preprocessing. During training, small rotations, flips, and mild intensity changes were applied to reduce overfitting while keeping lesion shapes realistic. Scans that failed alignment or showed inconsistent tissue boundaries were excluded.

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulas

T1 and FLAIR images were combined into a two-channel input for each subject. Structural priors were created by estimating the probability of WMH in periventricular and deep regions. Let

be the input and the predicted mask. The model learned a mapping

where

denotes the model parameters. Segmentation was measured using the Dice score [

14]:

Where

is the reference mask. A simple loss term encouraged the attention map

to stay close to the prior map

:

After prediction, small isolated regions were removed to reduce false detections in deep areas.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All results were reported as mean values and standard deviations. Segmentation metrics were compared between the proposed model and the baseline model using standard paired tests. Confidence intervals for Dice, HD95, and IoU were obtained through bootstrap sampling. Periventricular and deep regions were analyzed separately to examine region-specific trends. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all tests.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Performance on WMH2020

SPAN-WMH shows clear gains on the WMH2020 dataset of 1100 subjects. Deep-WMH Dice increases from 0.643 to 0.742, and periventricular Dice increases from 0.821 to 0.884. HD95 decreases by 28.3%, indicating fewer large boundary errors. These results show that adding structural priors improves detection in both regions. Similar studies based on U-Net variants report that deep lesions often have lower Dice values due to weak contrast and small size [

15]. SPAN-WMH reduces this gap and keeps performance stable across subjects with different lesion loads.

Figure 1.

Dice, HD95, and volume error for SPAN-WMH and the baseline model on the WMH2020 dataset.

Figure 1.

Dice, HD95, and volume error for SPAN-WMH and the baseline model on the WMH2020 dataset.

3.2. Region-Wise Evaluation and Detection of Small Deep Lesions

Region-wise evaluation shows that SPAN-WMH improves segmentation in both periventricular and deep areas. The larger gain in deep regions (+0.099 Dice) suggests that structural priors help the model detect small and scattered lesions that are often overlooked by intensity-based networks [

16]. Small-region IoU increases by 12.1%, which shows better retention of tiny lesions that tend to be eroded during post-processing in many U-Net-based methods.

Figure 2.

Region-wise Dice and small-region IoU, with examples of periventricular and deep WMH segmentation.

Figure 2.

Region-wise Dice and small-region IoU, with examples of periventricular and deep WMH segmentation.

3.3. Contribution of Structural Priors and Attention

Ablation tests confirm that both components—structural priors and the attention module—contribute to performance gains. Removing the priors leads to a clear drop in deep-WMH Dice and small-region IoU. Using only distance-to-ventricle maps provides some benefit, but the improvement is smaller than using cohort-derived priors, suggesting that data-driven priors capture more realistic spatial patterns [

17,

18]. We also compared two ways of using priors. Adding priors as extra channels improves periventricular Dice but has little effect on deep lesions. Using priors inside the attention block improves both regions. This indicates that modulating intermediate features with anatomical information works better than treating priors as static inputs. Similar observations have been made in other medical segmentation studies where spatial weighting improves sensitivity to small lesions and reduces false positives [

19].

3.4. Model Generalization and Limitations

Although SPAN-WMH performs well on WMH2020, several limitations should be noted. The dataset provides preprocessed scans with consistent registration and skull removal, which may not reflect the full variation seen in clinical imaging. Models trained on such data often show lower performance on external cohorts with different scanners or noise levels. Testing on real-world hospital data is therefore needed. The priors in this work are built from a single cohort and may not represent WMH patterns in populations with different ages or health conditions. The current model also focuses only on WMH and does not distinguish between other small-vessel disease markers, such as lacunes or microbleeds [

20]. Future work may include multi-center training, joint prediction of several lesion types, and uncertainty estimation to flag regions with low confidence. Despite these limitations, the results show that structural priors embedded within attention can improve both periventricular and deep WMH segmentation, especially for small deep lesions that remain difficult for many existing models.

4. Conclusions

This study presents SPAN-WMH, a model that uses simple structural priors to guide the segmentation of periventricular and deep WMH. The method improves Dice, HD95, and small-region IoU on the WMH2020 dataset, with the largest gains seen in deep lesions. These findings show that including basic anatomical information can help the network detect region-dependent lesion patterns and reduce boundary mistakes. The approach may support studies that use regional WMH measures to track cognitive changes or vascular risk. The work has several limits. All experiments were done on a preprocessed dataset, so performance on routine clinical scans remains uncertain. The priors were built from one cohort and may not match patterns in other populations or centers. The model also focuses only on WMH and does not cover other small-vessel disease findings. Future work may include testing on external cohorts, building priors from multiple datasets, and extending the design to other lesion types. Despite these limits, the results indicate that structural priors combined with attention can strengthen both global and region-wise WMH segmentation.

References

- Debette, S.; Beiser, A.; DeCarli, C.; Au, R.; Himali, J. J.; Kelly-Hayes, M.; Seshadri, S. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke 2010, 41, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, W. D.; Rosenberg, G. A.; Thiel, A.; Berlot, R.; de Reuck, J. Neuroimaging in vascular cognitive impairment: a state-of-the-art review. BMC medicine 2016, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, C.; Su, Y.; Hong, Z.; Gong, Z.; Xu, J. CenterMamba-SAM: Center-Prioritized Scanning and Temporal Prototypes for Brain Lesion Segmentation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.01243. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, D.; Gamez, J.; Ebrahimi, S. M.; Wang, Y.; Verma, N.; Poe, A. J.; Saghizadeh, M. Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijf, H. J.; Biesbroek, J. M.; De Bresser, J.; Heinen, R.; Andermatt, S.; Bento, M.; Biessels, G. J. Standardized assessment of automatic segmentation of white matter hyperintensities and results of the WMH segmentation challenge. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2019, 38, 2556–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Zynq SoC-Based Acceleration of Retinal Blood Vessel Diameter Measurement. Archives of Advanced Engineering Science 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Nabi, H.; Ali, M.; Awajan, A.; Daoud, M.; Alazrai, R.; Suganthan, P. N.; Ali, T. A comprehensive review of the deep learning-based tumor analysis approaches in histopathological images: segmentation, classification and multi-learning tasks. Cluster Computing 2023, 26, 3145–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y. Optimized Design of Medical Welded Structures for Life Enhancement. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y. S.; Yang, H.; Fu, H.; Feng, M. Teaching ai the anatomy behind the scan: Addressing anatomical flaws in medical image segmentation with learnable prior. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2025; pp. 24024–24033. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, H. Comprehensive Evaluation of GLP1 Receptor Agonists in Modulating Inflammatory Pathways and Gut Microbiota. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, P. R.; Petersen, S. E.; Ances, B. M.; Gordon, B. A.; Benzinger, T. L.; Morris, J. C.; Balota, D. A. Evaluating the sensitivity of resting-state BOLD variability to age and cognition after controlling for motion and cardiovascular influences: a network-based approach. Cerebral Cortex 2020, 30, 5686–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, T.; Huang, M.; Xu, K.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, X. LEGEND: Identifying Co-expressed Genes in Multimodal Transcriptomic Sequencing Data. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. Genetic and environmental influences on human brain changes in ageing. Doctoral dissertation, University of New South Wales (Australia)), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, D.; Mahmood, N.; Kellar, R. S.; Gluck, J. M.; King, M. W. Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. In ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, H. Precision-Engineered Nanocarriers for Targeted Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Disorders. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzakimuena, C. B. Automated analysis of retinal and choroidal OCT and OCTA images in AMD. In Ecole Polytechnique; Montreal (Canada), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Suk, J. S. A two-pronged pulmonary gene delivery strategy: a surface-modified fullerene nanoparticle and a hypotonic vehicle. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60, 15225–15229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikoula, M.; Quint, J. K.; Kallis, C.; Henry, A.; Denaxas, S. Identification of clinically meaningful, overlapping obstructive respiratory disease subtypes via data-driven approaches in a primary care population. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2025, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, A. A.; Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC medical imaging 2015, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurol, M. E.; Biessels, G. J.; Polimeni, J. R. Advanced neuroimaging to unravel mechanisms of cerebral small vessel diseases. Stroke 2020, 51, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).