Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

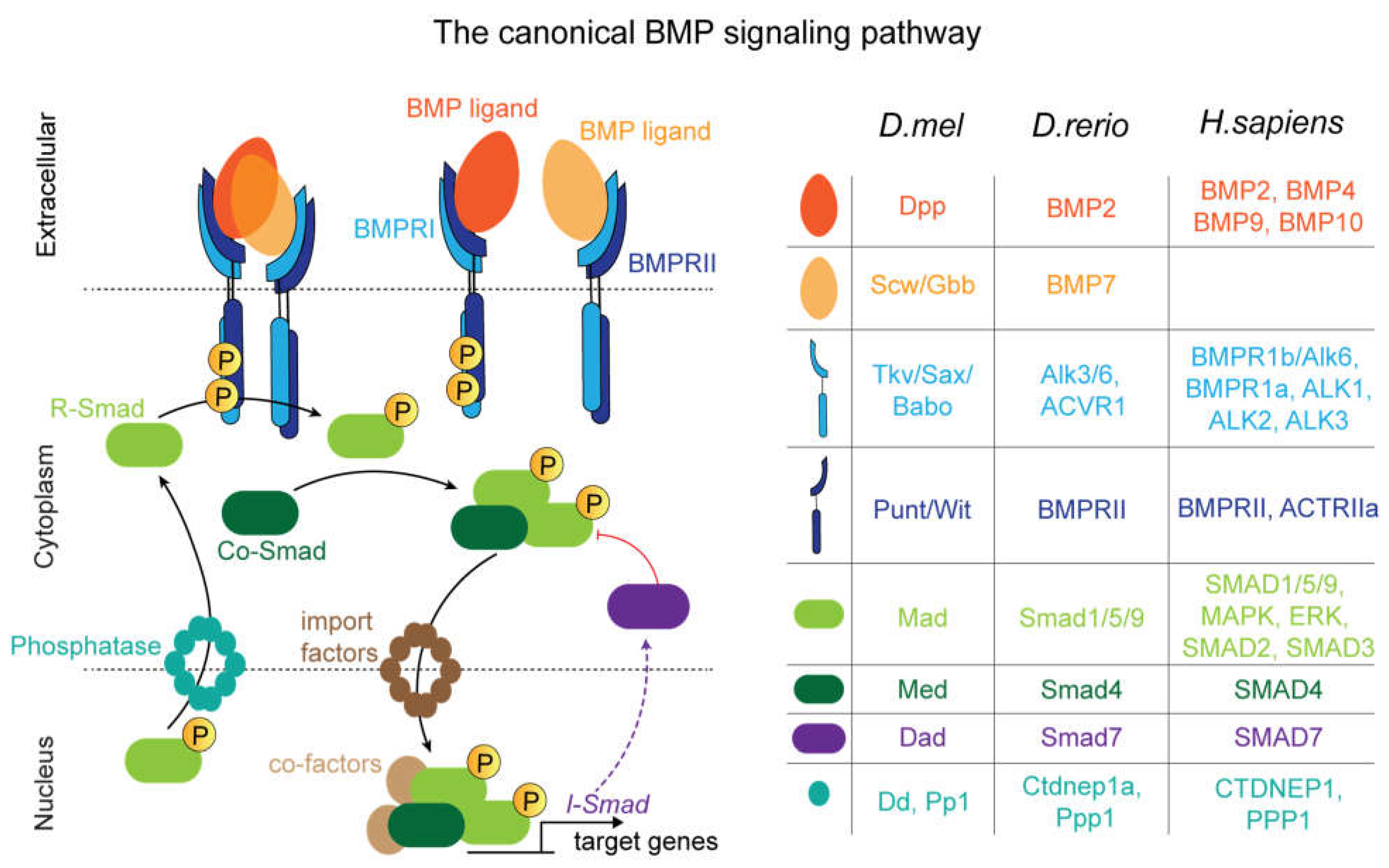

Introduction

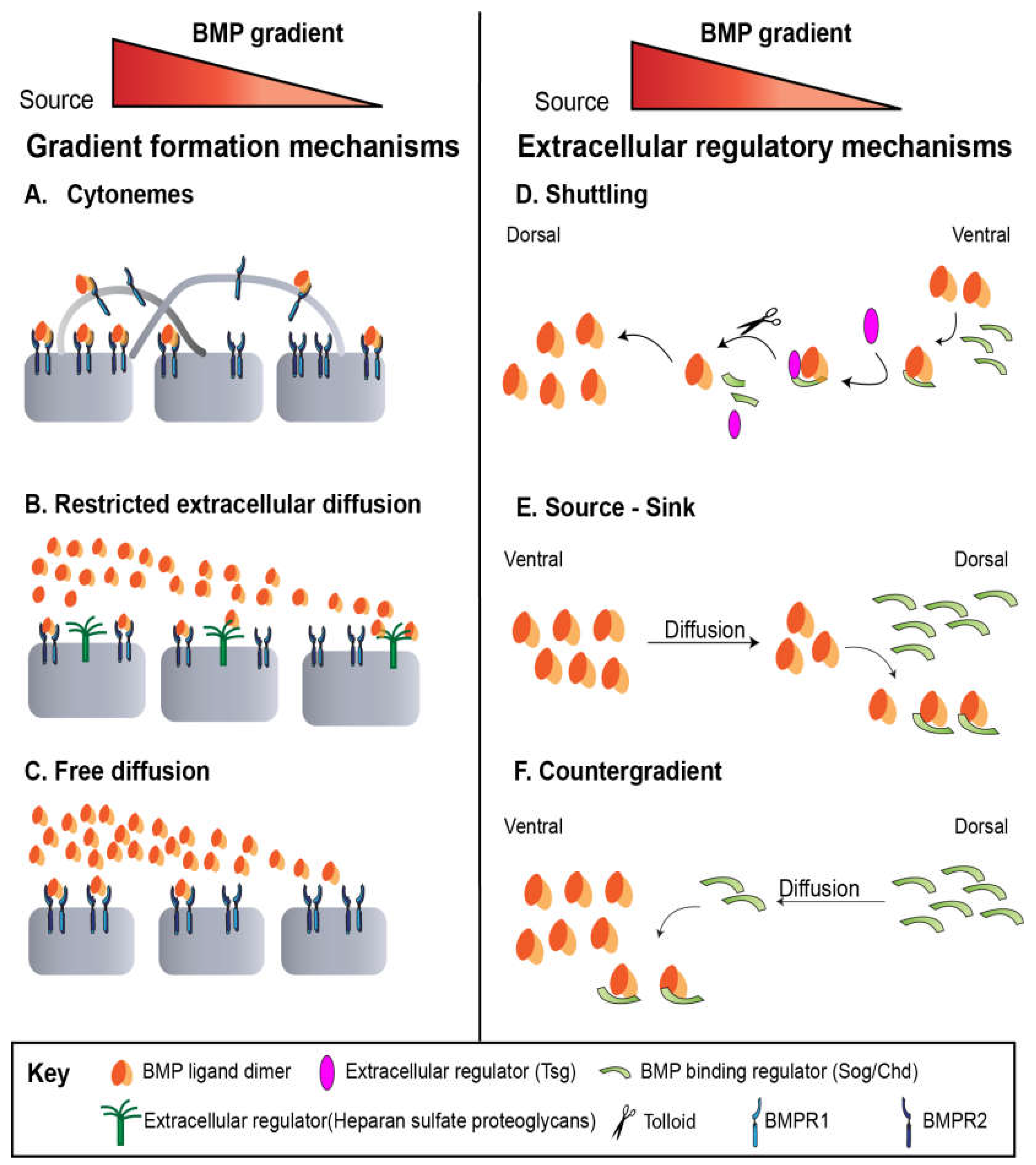

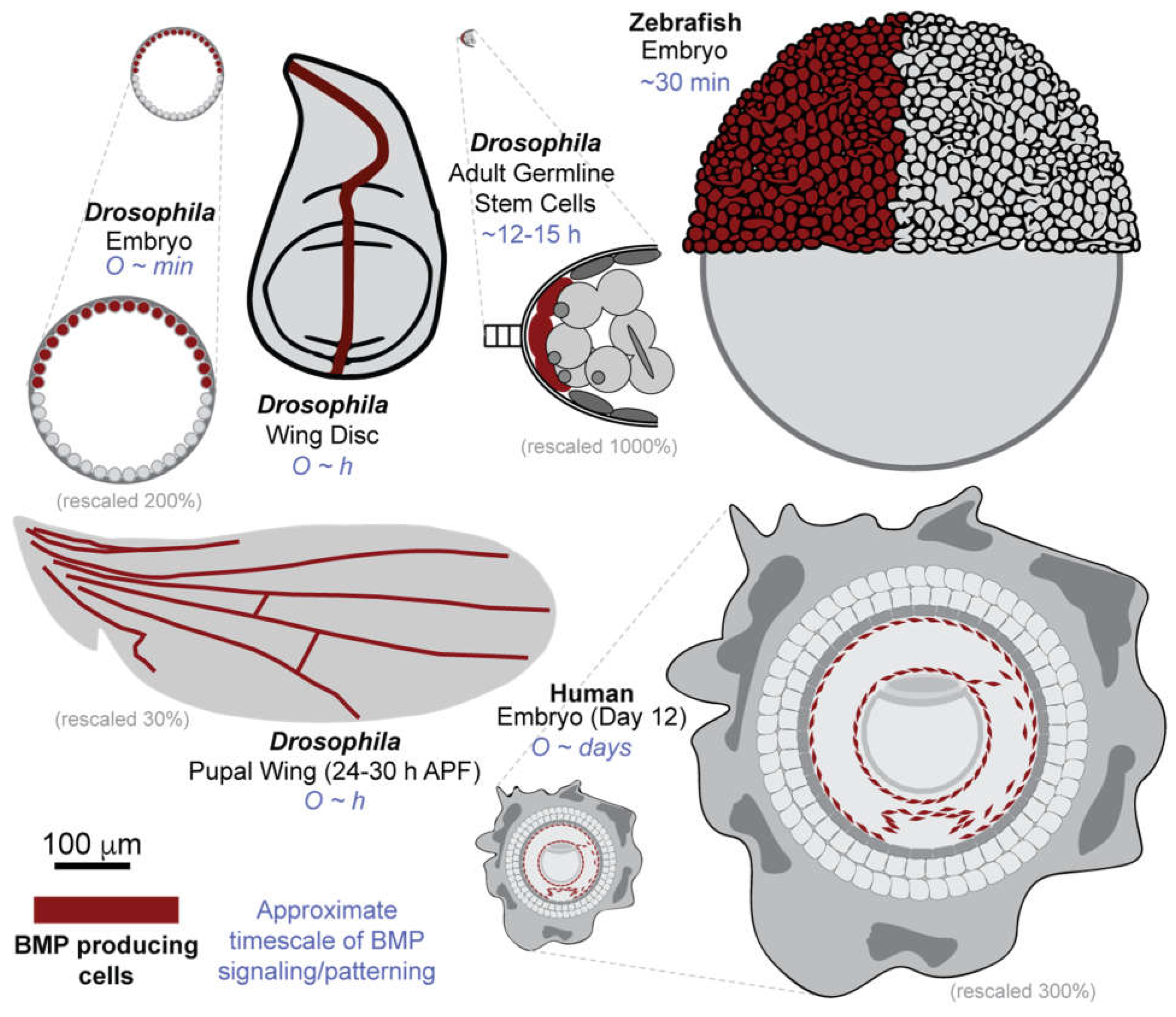

Mechanisms of Gradient Formation Across Development

Drosophila blastoderm embryo

Drosophila Larval Wing Disc

Drosophila Pupal Wing

Drosophila Germline Stem Cells

Zebrafish

Human Stem Cells

Interpretation of BMP Signals via Transcriptional Regulation

Drosophila embryo development

Drosophila Larval Wing Disc

Drosophila Pupal Wing

Drosophila Germline Stem Cells

Zebrafish

Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

Phosphorylated Smad as a Proxy for BMP Signaling Activity - Quantitative measurements

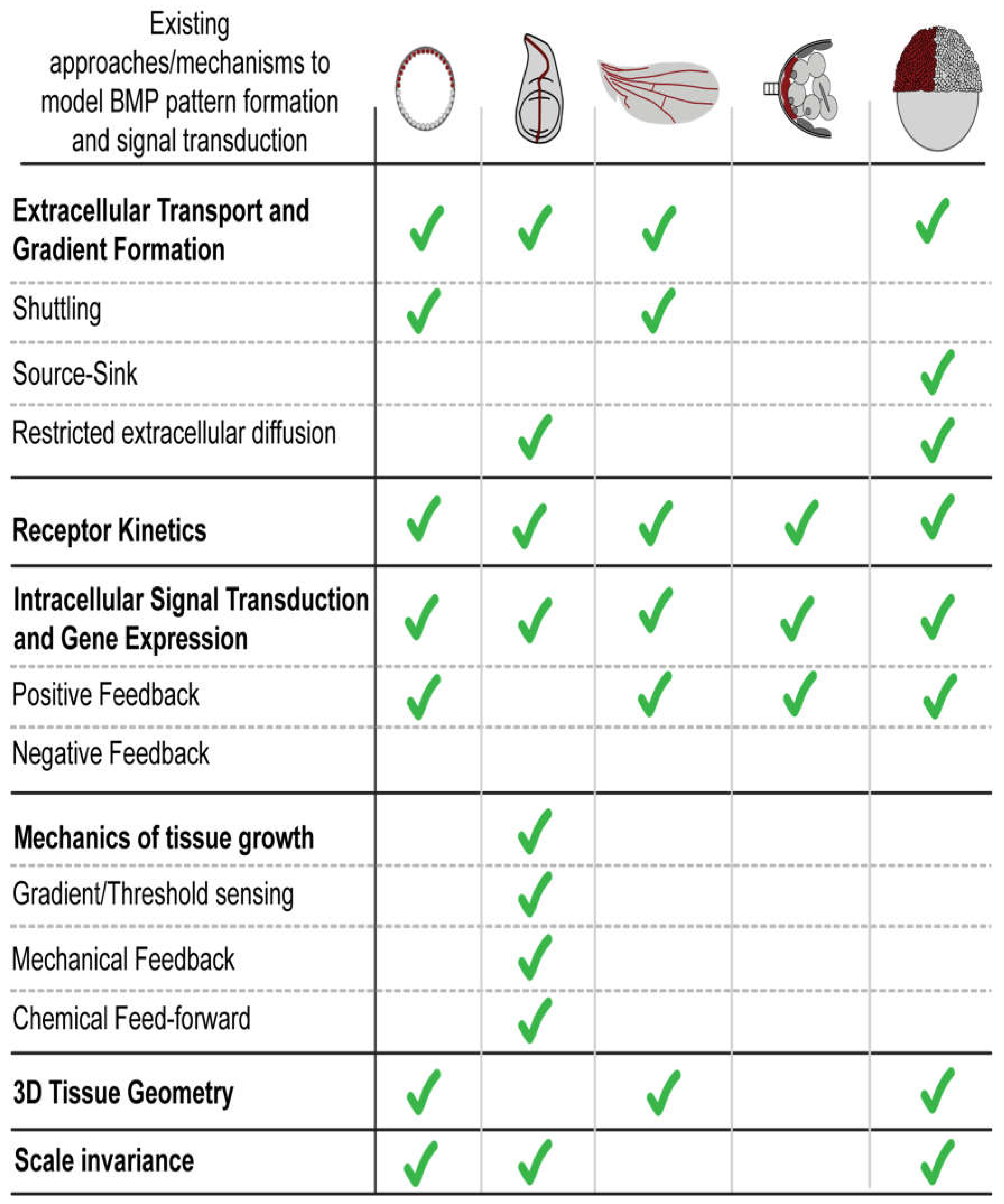

Computational Modelling Approaches that Drive Mechanical Insights and Cross-Species Insights

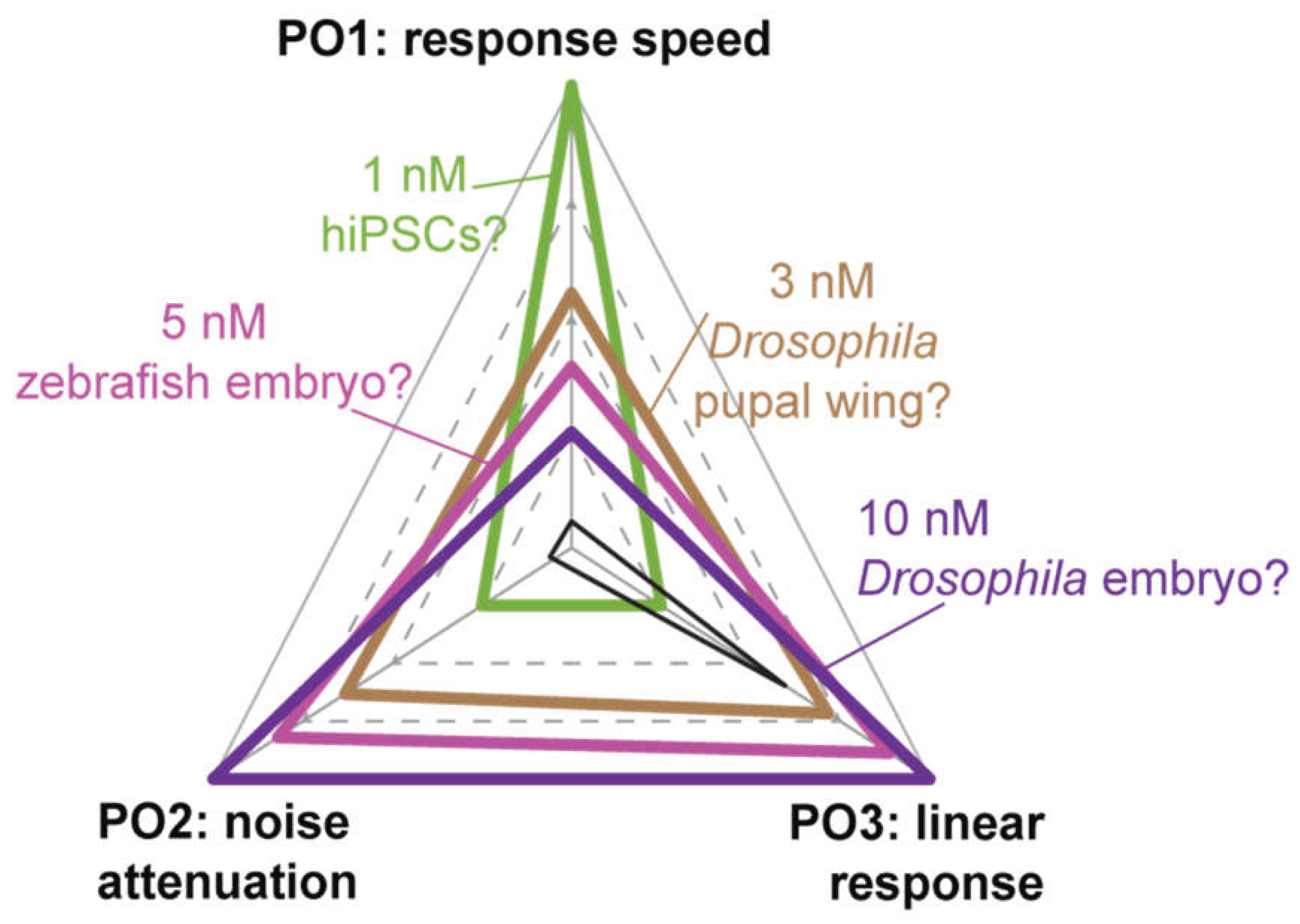

Pathway level Performance Objectives in System-Specific Contexts

Discussion & Open Questions

References

- Donovan, P.J.; Gearhart, J. The end of the beginning for pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, F.; Asao, H.; Sugamura, K.; Heldin, C.; Dijke, P.T.; Itoh, S. Promoting bone morphogenetic protein signaling through negative regulation of inhibitory Smads. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4132–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, R.W.; Wozney, J.M.; Gelbart, W.M. Human BMP sequences can confer normal dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 2905–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftery, L.A.; Sutherland, D.J. TGF-β Family Signal Transduction in Drosophila Development: From Mad to Smads. Dev. Biol. 1999, 210, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, C.; Zuñiga, A.; Hanna, P.; Hodar, C.; Gonzalez, M.; Cambiazo, V. Target genes of Dpp/BMP signaling pathway revealed by transcriptome profiling in the early D. melanogaster embryo. Gene 2016, 591, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, M.; Kinoshita, N.; Kamoshida, Y.; Tanimoto, H.; Tabata, T. brinker is a target of Dpp in Drosophila that negatively regulates Dpp-dependent genes. Nature 1999, 398, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Sturtevant, M.A.; Biehs, B.; François, V.; Padgett, R.W.; Blackman, R.K.; Bier, E. The Drosophila decapentaplegic and short gastrulation genes function antagonistically during adult wing vein development. Development 1996, 122, 4033–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, MB; Umulis, D; Othmer, HG; Blair, SS. Shaping BMP morphogen gradients in the Drosophila embryo and pupal wing. Development 2006, 133(2), 183–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Shimmi, O. Directional transport and active retention of Dpp/BMP create wing vein patterns in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2012, 366, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, S.S. Wing Vein Patterning in Drosophila and the Analysis of Intercellular Signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, J.D.; Urban, S.; Freeman, M. A family of rhomboid-like genes: Drosophila rhomboid-1 and roughoid/rhomboid-3 cooperate to activate EGF receptor signaling. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1651–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, J.; Groppe, J.; Guillemin, K.; Krasnow, M.A.; Gehring, W.J.; Affolter, M. The Drosophila Serum Response Factor gene is required for the formation of intervein tissue of the wing and is allelic to blistered. Development 1996, 122, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcockson, S.G.; Ashe, H.L. Drosophila Ovarian Germline Stem Cell Cytocensor Projections Dynamically Receive and Attenuate BMP Signaling. Dev. Cell 2019, 50, 296–312.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfeld, H.; Lin, J.; Mullins, M.C. The BMP signaling gradient is interpreted through concentration thresholds in dorsal–ventral axial patterning. PLOS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, K.W.; ElGamacy, M.; Jordan, B.M.; Müller, P. Optogenetic investigation of BMP target gene expression diversity. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duffhues, G.; Hiepen, C. Human iPSCs as Model Systems for BMP-Related Rare Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Asafen, H.; Beseli, A.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hiremath, S.; Williams, C.M.; Reeves, G.T. Dynamics of BMP signaling and stable gene expression in the early Drosophila embryo. Biol. Open 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, SE; Janssen, J; Chao, A; Vergassola, M; Blythe, SA; Di Talia, S. Rapid transcriptional response to a dynamic morphogen by time integration [Internet]. Developmental Biology. Available from. 2025. http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.06.09.658715.

- A Teleman, A.; Cohen, S.M. Dpp Gradient Formation in the Drosophila Wing Imaginal Disc. Cell 2000, 103, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, A.; Blair, S.S. Long-range Dpp signaling is regulated to restrict BMP signaling to a crossvein competent zone. Dev. Biol. 2005, 280, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Huang, Y.; Montanari, M.; Toddie-Moore, D.; Kikushima, K.; Nix, S.; Ishimoto, Y.; Shimmi, O. Coupling between dynamic 3D tissue architecture and BMP morphogen signaling during Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 4352–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Spradling, A.C. decapentaplegic Is Essential for the Maintenance and Division of Germline Stem Cells in the Drosophila Ovary. Cell 1998, 94, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madamanchi, A.; Mullins, M.C.; Umulis, D.M. Diversity and robustness of bone morphogenetic protein pattern formation. Development 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, C.M.; Nie, Q.; Wan, F.Y.; Zhang, Y.-T.; Vilmos, P.; Sousa-Neves, R.; Bier, E.; Marsh, J.L.; Lander, A.D. Formation of the BMP Activity Gradient in the Drosophila Embryo. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.M.; Chen, A.; Koh, P.W.; Deng, T.Z.; Sinha, R.; Tsai, J.M.; Barkal, A.A.; Shen, K.Y.; Jain, R.; Morganti, R.M.; et al. Mapping the Pairwise Choices Leading from Pluripotency to Human Bone, Heart, and Other Mesoderm Cell Types. Cell 2016, 166, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, N.; Ye, L.; Kobayashi, T.; Mochida, Y.; Yamauchi, M.; Kronenberg, H.M.; Feng, J.Q.; Mishina, Y. BMP signaling negatively regulates bone mass through sclerostin by inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway. Development 2008, 135, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrutia, H; Aleman, A; Eivers, E. Drosophila Dullard functions as a Mad phosphatase to terminate BMP signaling. Sci Rep. 2016, 6(1), 32269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardi, J.; Bener, M.B.; Simao, T.; Descoteaux, A.E.; Slepchenko, B.M.; Inaba, M. Mad dephosphorylation at the nuclear pore is essential for asymmetric stem cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.S.; Nakane, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.L.; Terabayashi, T.; Abe, T.; Nakao, K.; Asashima, M.; Steiner, K.A.; Tam, P.P.L.; Nishinakamura, R. Dullard/Ctdnep1 Modulates WNT Signalling Activity for the Formation of Primordial Germ Cells in the Mouse Embryo. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e57428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podos, S.D.; Hanson, K.K.; Wang, Y.-C.; Ferguson, E.L. The DSmurf Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase Restricts BMP Signaling Spatially and Temporally during Drosophila Embryogenesis. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentino, M.L.; E Bronner, M. Intracellular attenuation of BMP signaling via CKIP-1/Smurf1 is essential during neural crest induction. PLOS Biol. 2018, 16, e2004425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Etlinger, J.D. Role of SMURF1 ubiquitin ligase in BMP receptor trafficking and signaling. Cell. Signal. 2019, 54, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; A Raftery, L.; A Wharton, K. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling: the pathway and its regulation. Genetics 2023, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antebi, Y.E.; Linton, J.M.; Klumpe, H.; Bintu, B.; Gong, M.; Su, C.; McCardell, R.; Elowitz, M.B. Combinatorial Signal Perception in the BMP Pathway. Cell 2017, 170, 1184–1196.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpe, H.E.; Langley, M.A.; Linton, J.M.; Su, C.J.; Antebi, Y.E.; Elowitz, M.B. The context-dependent, combinatorial logic of BMP signaling. Cell Syst. 2022, 13, 388–407.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinski, J.; Tuazon, F.; Huang, Y.; Mullins, M.; Umulis.

- Schmierer, B.; Tournier, A.L.; Bates, P.A.; Hill, C.S. Mathematical modeling identifies Smad nucleocytoplasmic shuttling as a dynamic signal-interpreting system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 6608–6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, I.; Burt, K.; Miller, M.; Chhabra, S.; Guerra, M.C.; Liu, L.; Warmflash, A. Rapid changes in morphogen concentration control self-organized patterning in human embryonic stem cells. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.J.; Shimmi, O.; Vilmos, P.; Petryk, A.; Kim, H.; Gaudenz, K.; Hermanson, S.; Ekker, S.C.; O'COnnor, M.B.; Marsh, J.L. Twisted gastrulation is a conserved extracellular BMP antagonist. Nature 2001, 410, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, R.; Shilo, B.-Z. Biphasic activation of the BMP pathway patterns the Drosophila embryonic dorsal region. Development 2001, 128, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umulis, D.M.; Serpe, M.; O’connor, M.B.; Othmer, H.G. Robust, bistable patterning of the dorsal surface of the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 11613–11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Ferguson, E.L. Spatial bistability of Dpp–receptor interactions during Drosophila dorsal–ventral patterning. Nature 2005, 434, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umulis, D.M.; Shimmi, O.; O'COnnor, M.B.; Othmer, H.G. Organism-Scale Modeling of Early Drosophila Patterning via Bone Morphogenetic Proteins. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Affolter, M. Is Drosophila Dpp/BMP morphogen spreading required for wing patterning and growth? BioEssays 2023, 45, e2200218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwank, G.; Dalessi, S.; Yang, S.-F.; Yagi, R.; de Lachapelle, A.M.; Affolter, M.; Bergmann, S.; Basler, K. Formation of the Long Range Dpp Morphogen Gradient. PLOS Biol. 2011, 9, e1001111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, S.; Zartman, J.J.; Basler, K. Coordination of Patterning and Growth by the Morphogen DPP. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R245–R255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancher, S.; Mugler, A. Diffusion vs. direct transport in the precision of morphogen readout. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Harmansa, S.; Affolter, M. BMP morphogen gradients in flies. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 27, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zvi, D.; Barkai, N. Scaling of morphogen gradients by an expansion-repression integral feedback control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 6924–6929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, W.; Nie, Q.; Lander, A.D. Scaling a Dpp Morphogen Gradient through Feedback Control of Receptors and Co-receptors. Dev. Cell 2020, 53, 724–739.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanova-Michaelides, M.; Hadjivasiliou, Z.; Aguilar-Hidalgo, D.; Basagiannis, D.; Seum, C.; Dubois, M.; Jülicher, F.; Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. Morphogen gradient scaling by recycling of intracellular Dpp. Nature 2021, 602, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpe, M.; Umulis, D.; Ralston, A.; Chen, J.; Olson, D.J.; Avanesov, A.; Othmer, H.; O'COnnor, M.B.; Blair, S.S. The BMP-Binding Protein Crossveinless 2 Is a Short-Range, Concentration-Dependent, Biphasic Modulator of BMP Signaling in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antson, H.; Tõnissoo, T.; Shimmi, O. The developing wing crossvein of Drosophila melanogaster: a fascinating model for signaling and morphogenesis. Fly 2022, 16, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, M.; Ralston, A.; Blair, S.S.; O'Connor, M.B. Matching catalytic activity to developmental function: Tolloid-related processes Sog in order to help specify the posterior crossvein in theDrosophilawing. Development 2005, 132, 2645–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S; Schaefer, JV; Mii, Y; Hori, Y; Bieli, D; Taira, M; et al. Asymmetric requirement of Dpp/BMP morphogen dispersal in the Drosophila wing disc. Nat Commun. 2021, 12(1), 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Cai, Y. The JAK/STAT pathway positively regulates DPP signaling in the Drosophila germline stem cell niche. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 180, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Page-McCaw, A. Wnt6 maintains anterior escort cells as an integral component of the germline stem cell niche. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Jia, S.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, Y.; Kan, L.; Zheng, W.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; et al. The Fused/Smurf Complex Controls the Fate of Drosophila Germline Stem Cells by Generating a Gradient BMP Response. Cell 2010, 143, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Tao, Y.; Chen, D. The Niche-Dependent Feedback Loop Generates a BMP Activity Gradient to Determine the Germline Stem Cell Fate. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.; Larson, N.J.; Kam, J.; Hanjaya-Putra, D.; Zartman, J.; Umulis, D.M.; Li, L.; Reeves, G.T. Optimal performance objectives in the highly conserved bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2024, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, M.O.; Ferguson, E.L. Germline stem cell number in theDrosophilaovary is regulated by redundant mechanisms that control Dpp signaling. Development 2004, 131, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Zou, L.; Ji, S.; Li, C.; Liu, K.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Q.; Xiao, F.; Chen, D. Membrane targeting of inhibitory Smads through palmitoylation controls TGF-β/BMP signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 13206–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomreinke, AP; Soh, GH; Rogers, KW; Bergmann, JK; Bläßle, AJ; Müller, P. Dynamics of BMP signaling and distribution during zebrafish dorsal-ventral patterning. eLife 2017, 6, e25861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.A.; Trout, J.; Ekker, M.; Mullins, M.C. The role of tolloid/mini fin in dorsoventral pattern formation of the zebrafish embryo. Development 1999, 126, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka, O.; Shimizu, T.; Yabe, T.; Nojima, H.; Bae, Y.-K.; Hashimoto, H.; Hibi, M. Sizzled controls dorso-ventral polarity by repressing cleavage of the Chordin protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, T.; Shimizu, T.; Muraoka, O.; Bae, Y.-K.; Hirata, T.; Nojima, H.; Kawakami, A.; Hirano, T.; Hibi, M. Ogon/Secreted Frizzled functions as a negative feedback regulator of Bmp signaling. Development 2003, 130, 2705–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentzsch, F.; Zhang, J.; Kramer, C.; Sebald, W.; Hammerschmidt, M. Crossveinless 2 is an essential positive feedback regulator of Bmp signaling during zebrafish gastrulation. Development 2006, 133, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinski, J.; Bu, Y.; Wang, X.; Dou, W.; Umulis, D.; Mullins, M.C. Systems biology derived source-sink mechanism of BMP gradient formation. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.; Mullins, M.C.; Umulis, D.M. Evaluation of BMP-mediated patterning in a 3D mathematical model of the zebrafish blastula embryo. J. Math. Biol. 2019, 80, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmflash, A.; Sorre, B.; Etoc, F.; Siggia, E.D.; Brivanlou, A.H. A method to recapitulate early embryonic spatial patterning in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Townshend, R.F.; Miki, T.; Gumucio, D.L.; Fu, J. A pluripotent stem cell-based model for post-implantation human amniotic sac development. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etoc, F.; Metzger, J.; Ruzo, A.; Kirst, C.; Yoney, A.; Ozair, M.Z.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Siggia, E.D. A Balance between Secreted Inhibitors and Edge Sensing Controls Gastruloid Self-Organization. Dev. Cell 2016, 39, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, H.; Werschler, N.; Jones, R.D.; Siu, M.M.; Tewary, M.; Hagner, A.; Ostblom, J.; Aguilar-Hidalgo, D.; Zandstra, P.W. Virtual cells in a virtual microenvironment recapitulate early development-like patterns in human pluripotent stem cell colonies. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 18, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, S.; Liu, L.; Goh, R.; Kong, X.; Warmflash, A. Dissecting the dynamics of signaling events in the BMP, WNT, and NODAL cascade during self-organized fate patterning in human gastruloids. PLOS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, S.; Primavera, G.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Yao, L.; Freeburne, E.; Khan, H.; Jo, K.; Johnson, C.; Heemskerk, I. Time-integrated BMP signaling determines fate in a stem cell model for early human development. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjaya-Putra, D.; Gerecht, S. Vascular engineering using human embryonic stem cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009, 25, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, S.; Shen, Y.-I.; Hanjaya-Putra, D.; Mali, P.; Cheng, L.; Gerecht, S. Self-organized vascular networks from human pluripotent stem cells in a synthetic matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 12601–12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, H.L.; Mannervik, M.; Levine, M. Dpp signaling thresholds in the dorsal ectoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Development 2000, 127, 3305–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahda, J.S.; Ambrosi, P.; Mizutani, C.M. The nested embryonic dorsal domains of BMP-target genes are not scaled to size during the evolution of Drosophila species. J. Exp. Zoöl. Part B: Mol. Dev. Evol. 2022, 340, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, C; Bowles, JR; Minchington, TG; Sutcliffe, C; Upadhyai, P; Rattray, M; et al. Modulation of the Promoter Activation Rate Dictates the Transcriptional Response to Graded BMP Signaling Levels in the Drosophila Embryo. Dev Cell 2020, 54(6), 727–741.e7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Wong, M.D.; Kawase, E.; Xi, R.; Ding, B.C.; McCarthy, J.J.; Xie, T. Bmp signals from niche cells directly repress transcription of a differentiation-promoting gene,bag of marbles, in germline stem cells in theDrosophilaovary. Development 2004, 131, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; McKearin, D. Dpp Signaling Silences bam Transcription Directly to Establish Asymmetric Divisions of Germline Stem Cells. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargett, M.; Rundell, A.E.; Buzzard, G.T.; Umulis, D.M. Model-Based Analysis for Qualitative Data: An Application in Drosophila Germline Stem Cell Regulation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinski, J.; Tajer, B.; Mullins, M.C. TGF-β Family Signaling in Early Vertebrate Development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 10, a033274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotewold, L.; Rüther, U. The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 is regulated by Bmp signaling and c-Jun and modulates programmed cell death. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.X.; Ambrosio, A.L.; Reversade, B.; De Robertis, E. Embryonic Dorsal-Ventral Signaling: Secreted Frizzled-Related Proteins as Inhibitors of Tolloid Proteinases. Cell 2006, 124, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuazon, F.B.; Wang, X.; Andrade, J.L.; Umulis, D.; Mullins, M.C. Proteolytic Restriction of Chordin Range Underlies BMP Gradient Formation. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108039–108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramel, M.-C.; Hill, C.S. The ventral to dorsal BMP activity gradient in the early zebrafish embryo is determined by graded expression of BMP ligands. Dev. Biol. 2013, 378, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, A.; Oehlmann, V.; Heymer, J.; Rüther, U.; Nordheim, A. Id Genes Are Direct Targets of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Induction in Embryonic Stem Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19838–19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Hsiao, E.C.; Sami, S.; Lancero, M.; Schlieve, C.R.; Nguyen, T.; Yano, K.; Nagahashi, A.; Ikeya, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; et al. BMP-SMAD-ID promotes reprogramming to pluripotency by inhibiting p16/INK4A-dependent senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 13057–13062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, Y.; Weintraub, H.; Benezra, R. Overexpression of Id protein inhibits the muscle differentiation program: in vivo association of Id with E2A proteins. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 1466–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, I.N.; A Christy, B. Muscle cell differentiation is inhibited by the helix-loop-helix protein Id3. 1996, 7, 1067–79. [Google Scholar]

- Korchynskyi, O.; Dijke, P.T. Identification and Functional Characterization of Distinct Critically Important Bone Morphogenetic Protein-specific Response Elements in the Id1 Promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 4883–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, F.; Wu, M.; Wang, Z.Z. Development of Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells From Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, T.; Xia, K.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, H.; Han, J.-D.J.; et al. Genome-wide mapping of SMAD target genes reveals the role of BMP signaling in embryonic stem cell fate determination. Genome Res. 2009, 20, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Graham, F.; Knopp, J.; Patzke, C.; Hanjaya-Putra, D. Robust Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells into Lymphatic Endothelial Cells Using Transcription Factors. Cells Tissues Organs 2024, 213, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, M.; James, D.; Ding, B.-S.; Nolan, D.; Geng, F.; Butler, J.M.; Schachterle, W.; Pulijaal, V.R.; Mathew, S.; Chasen, S.T.; et al. Efficient Direct Reprogramming of Mature Amniotic Cells into Endothelial Cells by ETS Factors and TGFβ Suppression. Cell 2012, 151, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Takase, M.; Nishihara, A.; Oeda, E.; Hanai, J.-I.; Kawabata, M.; Miyazono, K. Smad6 inhibits signalling by the TGF-β superfamily. Nature 1997, 389, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, W; Hamamoto, T; Kusanagi, K; Yagi, K; Kawabata, M; Takehara, K; et al. Smad6 Is a Smad1/5-induced Smad Inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275(9), 6075–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A; Afrakhte, M; Morn, A; Nakayama, T; Christian, JL; Heuchel, R; et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFβ-inducible antagonist of TGF-β signalling. Nature 1997, 389(6651), 631–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X; Liu, Z; Chen, Y. Regulation of TGF-β signaling by Smad7. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2009, 41(4), 263–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onichtchouk, D; Chen, YG; Dosch, R; Gawantka, V; Delius, H; Massague’, J; et al. Silencing of TGF-β signalling by the pseudoreceptor BAMBI. Nature 1999, 401(6752), 480–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotewold, L.; Plum, M.; Dildrop, R.; Peters, T.; Rüther, U. Bambi is coexpressed with Bmp-4 during mouse embryogenesis. Mech. Dev. 2001, 100, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillot, N.; Kollins, D.; Gilbert, V.; Xavier, S.; Chen, J.; Gentle, M.; Reddy, A.; Bottinger, E.; Jiang, R.; Rastaldi, M.P.; et al. BAMBI Regulates Angiogenesis and Endothelial Homeostasis through Modulation of Alternative TGFβ Signaling. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e39406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, L.B.; De Jesús-Escobar, J.M.; Harland, R.M. The Spemann Organizer Signal noggin Binds and Inactivates Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4. Cell 1996, 86, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, S.; Sasai, Y.; Lu, B.; De Robertis, E.M. Dorsoventral Patterning in Xenopus: Inhibition of Ventral Signals by Direct Binding of Chordin to BMP-4. Cell 1996, 86, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainsod, A.; Deißler, K.; Yelin, R.; Marom, K.; Epstein, M.; Pillemer, G.; Steinbeisser, H.; Blum, M. The dorsalizing and neural inducing gene follistatin is an antagonist of BMP-4. Mech. Dev. 1997, 63, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzerro, E; Canalis, E. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2007, 7(1–2), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, C.C.; Mulloy, B. Bone morphogenetic protein and growth differentiation factor cytokine families and their protein antagonists. Biochem. J. 2010, 429, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, T.; Nakabayashi, J.; Yamamoto, T.S.; Mochii, M.; Ueno, N. Visualization of endogenous BMP signaling during Xenopus development. Differentiation 2001, 67, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, SE; Bird, NC; Devoto, SH. BMP regulation of myogenesis in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2010, 239(3), 806–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, S.; Mansour, S.L.; Schoenwolf, G.C. BMP/SMAD signaling regulates the cell behaviors that drive the initial dorsal-specific regional morphogenesis of the otocyst. Dev. Biol. 2010, 347, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, N.S.; Vora, M.; Padgett, R.W.; Li, Y. bantam microRNA is a negative regulator of the Drosophila decapentaplegic pathway. Fly 2018, 12, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, D.W.; Febbo, J.A.; Roman, B.L. Dynamic analysis of BMP-responsive smad activity in live zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 2011, 240, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramann, A.K.; Venkatesan, A.M.; Guerin, M.; Ceol, C.J. Regulation of zebrafish melanocyte development by ligand-dependent BMP signaling. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouillesseaux, K.P.; Wiley, D.S.; Saunders, L.; Wylie, L.A.; Kushner, E.J.; Chong, D.C.; Citrin, K.M.; Barber, A.T.; Park, Y.; Kim, J.-D.; et al. Notch regulates BMP responsiveness and lateral branching in vessel networks via SMAD6. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcockson, S.G.; Ashe, H.L. Live imaging of the Drosophila ovarian germline stem cell niche. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'KEefe, D.D.; Thomas, S.; Edgar, B.A.; Buttitta, L. Temporal regulation of Dpp signaling output in the Drosophila wing. Dev. Dyn. 2014, 243, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, NJ; Madamanchi, A; Li, L; Umulis, DM. Stochastic Modeling of BMP Heterodimer-Receptor Interactions Shows Emergence of Low-Pass Filtering Behavior [Internet]. Developmental Biology. Available from. 2025. http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.10.17.677951.

- Li, L.; Mdluli, T.; Buzzard, G.; Umulis, D. Digital cousins: Simultaneous optimization of one model for BMP signaling in distant relatives reveals essential core. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 3729–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, R.W.; Johnston, R.D.S.; Gelbart, W.M. A transcript from a Drosophila pattern gene predicts a protein homologous to the transforming growth factor-β family. Nature 1987, 325, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Levine, M.S.; O'COnnor, M.B. The screw gene encodes a ubiquitously expressed member of the TGF-beta family required for specification of dorsal cell fates in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 2588–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftery, AE; Zheng, Y. Discussion: Performance of Bayesian Model Averaging. J Am Stat Assoc. 2003, 98(464), 931–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin-Smyth, J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Butler, I.; Ferguson, E.L. A Genetic Network Conferring Canalization to a Bistable Patterning System in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2296–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Handin, R.I. Identification and Characterization of Zebrafish Tissue Factor and Its Role in Embryonic Blood Vessel Development. Blood 2007, 110, 3706–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, Y.G.; Mullins, M.C. Maternal and Zygotic Control of Zebrafish Dorsoventral Axial Patterning. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, D.; Heisenberg.

- Mullins, M.C.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Kane, D.A.; Odenthal, J.; Brand, M.; van Eeden, F.J.M.; Furutani-Seiki, M.; Granato, M.; Haffter, P.; Heisenberg, C.-P.; et al. Genes establishing dorsoventral pattern formation in the zebrafish embryo: the ventral specifying genes. Development 1996, 123, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, Y.; Lee, K.-H.; Zon, L.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Schulte-Merker, S. The molecular nature of zebrafish swirl: BMP2 function is essential during early dorsoventral patterning. Development 1997, 124, 4457–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, W.O.; Jaffray, E.; Campbell, S.G.; Takeda, S.; Bayston, L.J.; Basu, S.P.; Li, M.; Raftery, L.A.; Ashe, M.P.; Hay, R.T.; et al. Medea SUMOylation restricts the signaling range of the Dpp morphogen in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2578–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.A.; Mintzer, K.A.; Mullins, M.C. The BMP Signaling Gradient Patterns Dorsoventral Tissues in a Temporally Progressive Manner along the Anteroposterior Axis. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holford, M.; Normark, B.B. Integrating the Life Sciences to Jumpstart the Next Decade of Discovery. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attisano, L; Tuen Lee-Hoeflich, S. The Smads. Genome Biol. 2001, 2(8), reviews3010.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, S.A.; Jackson, P.D.; Sasai, Y.; Lu, B.; De Robertis, E.M.; Hoffmann, F.M.; Ferguson, E.L. A conserved system for dorsal-ventral patterning in insects and vertebrates involving sog and chordin. Nature 1995, 376, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Holley, S.; Neul, J.L.; Attisano, L.; Wrana, J.L.; Sasai, Y.; O'COnnor, M.B.; De Robertis, E.M.; Ferguson, E.L. The Xenopus Dorsalizing Factor noggin Ventralizes Drosophila Embryos by Preventing DPP from Activating Its Receptor. Cell 1996, 86, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, C.L.; Yarka, C.; Nunns, H.; Goentoro, L. Sensing relative signal in the Tgf-β/Smad pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E2975–E2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BMP pathway component and properties | Drosophila: Blastoderm Embryo |

Drosophila: Larval Wing Disc |

Drosophila: Pupal Wing |

Drosophila: Germline stem cells |

Zebrafish: Embryo |

Human: Endothelial cells differentiated from hPSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downstream target/ differentiation marker | Type I target: zen, Race,& hnt Type II target: rho, tup,& ush Type III target: pnr [5] |

Brinker (brk), optomotor-blind (omb), daughters against dpp (dad), and spalt major (sal) [6,7] |

Dad [6,7] & Crossveinless-2 (CV-2) (BMP-responsive extracellular regulator) [8,9] EGFR/MAPK outputs (vein differentiation): Rhomboid (rho), Star (s), and argos (aos) (indirect) [10,11], and blistered/Srf (bs) (repressed) [12] |

dad, Rfx, & futsch, bag of marbles (bam) [13] |

highest threshold: sizzled (szl) and tp63 Intermediate threshold: foxi1 and gata2a Low threshold: bambia [14,15] |

ID1, ID2, ID3 SMAD6/7 [16] |

| BMP Gradient Formation Time Scale | Tens of minutes after nuclear cycle 13 [17,18] | < 4 hours [19] | Hours (~18-30 h AP) [20,21] | Minutes (rapidly) [13,22] | Hours [23] | Not applicable* (uniform BMP signaling) |

| Gene expression time scale | ~30 minutes [24] | Not directly measured/TBD | Hours (Overlaps with gradient formation) [20] | Hours (not directly measured) (8) | Minutes to hours [14,15] |

≤ 24 hours (endpoint measured; onset not resolved) [25] |

| Gradient length scale | 5-6 cell diameters (35 μm) [24] |

20-40 cell diameters (100 μm) [23] | Short-range: vein restricted cell-scale, ~1-3 cell diameters (~5-15 μm) [10,20] Long-range: Transport to crossveins (~50-100 μms) [15,21] |

1-2 cell diameters (5 μm) (13,22,23) | 25+ cell diameters (~ 700 μm) [23] |

Not applicable* (uniform BMP signaling) |

| System | Modeling Approach/Type | Author(s) | Key Finding or Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila Embryo | Shuttling and receptor mediated degradation | Mizutani et al. (2005) | Showed that the sharp pMad peak requires the Sog/Tsg shuttling mechanism and Tolloid-mediated cleavage. |

| Positive feedback | Wang & Ferguson (2005) | Proposed that positive feedback and bistable dynamics reinforce and maintain sharp signaling boundaries. | |

| Receptor kinetics and feedback | Umulis et al. (2006) | Showed that slow, reversible receptor-ligand binding kinetics provide robustness against changes in receptor levels. | |

| 3D geometry | Umulis et al. (2010) | Argued that robustness must be evaluated by its effect on threshold and downstream gene expression. | |

| DrosophilaWing Disc | Restricted Diffusion | Schwank et. al. (2011) | Investigated competing hypotheses to show that Dpp transport occurs via restricted extracellular diffusion. |

| Gradient | Lawrence, P. A., & Struhl, G. (1996). | Proposes that the slope of the Dpp gradient drives cell proliferation if the slope is steeper than a certain threshold. | |

| Threshold (Gene Expression) | Schwank, G et al.(2008) | Proposes that cells proliferate if Dpp signaling is above a certain threshold level | |

| Temporal | Wartlick, O et al. (2011) | Proposed that cells respond to a relative increase (not absolute level) in Dpp to trigger uniform proliferation. | |

| Growth Equalization Model | Schwank, G. et al.(2008) & Schwank, G. et al.(2011) | Modeled how the target gene brk acts as a growth suppressor to balance proliferation across the disc. | |

| Mechanical Model | Aegerter-Wilmsen et al.(2007),Hufnagel,L. et al. (2007) | Modeled how physical tissue forces (compression/stretching) provide feedback to ensure uniform proliferation. | |

| Vg Feed-Forward Model | Zecca, M., & Struhl, G. (2021). | Modeled how Dpp, Wg, and Vg interact in a feed-forward loop to coordinate and expand the wing tissue. | |

| Expansion- Repression model | Ben-Zvi & Barkai (2010) | Modeled how Pentagone (Pent) acts as a rapidly diffusing "expander" molecule of the Dpp gradient. | |

| Pseudo source sink | Zhu et. al (2020) | Modeled how Dpp-mediated feedback downregulation of its own receptors drives scaling. | |

| Recycling | Romanova-Michaelides et al. (2021) | Modeled how Dpp gradient scaling is driven by a tunable “recycling gear” mechanism where the feedback regulator Pentagone modulates receptor binding to favor ligand re-exocytosis. | |

| Drosophila Pupal Wing | Gradient Formation | Gui et al. (2019) | Describes Dpp gradient formation mechanism during first apposition, inflation, and second apposition of pupal wing development to create the 3D architecture of the adult wing. |

| Receptor- Mediated Degradation & Shuttling | O’Connor (2006) | Discusses long-range Dpp transport through Sog/Ts2 shuttling mechanism and Tolkin protein-mediated cleavage. Proposed PCV formation is driven by Dpp/Gbb heterodimers. | |

| Positive Feedback Loop | H. Antson et al. (2022), O’Connor (2006) | Discusses positive-feedback loop of the Sog/CV-2 mediated transport and its proposed role in releasing Dpp:Gbb heterodimers in LVs to facilitate PCV formation. It also discusses the ability of this feedback loop to create sharp step-gradients for spatial bistability. | |

| DrosophilaGSC Niche | Bistability / Differentiation | Pargett et al. (2014) | Modeled the GSC/CB switch to identify Brat as a key differentiation factor that antagonizes BMP. |

| Positive Feedback Loop | Xia et al. (2012) | Modeled how Fused (Fu) dynamics create a positive feedback loop to maintain stemness (GSC) or allow differentiation (CB). | |

| Multi-compartment GSC division | Shaikh & Reeves (2024) | Modeled how Dad and Fused work synergistically to ensure robust GSC division and homeostasis. | |

| Zebrafish embryo | Mechanistic/ Gradient Formation | Zinski et. al. (2017) & Pomrienke et. al. (2017) | Tested theorized gradient models against mutant data, providing strong support for the source-sink mechanism. |

| 3D Simulation (Advection Diffusion Reaction) | Li et. al. (2019) | Developed a more geometrically accurate 3D model that also supported the source-sink mechanism. | |

| Stochastic Receptor Model | Larson et. al. (2025, preprint) | Modeled receptor combinations for signal transduction, showing emergent low-pass filter mechanism arising from heterodimer-heterotetramer requirement. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.