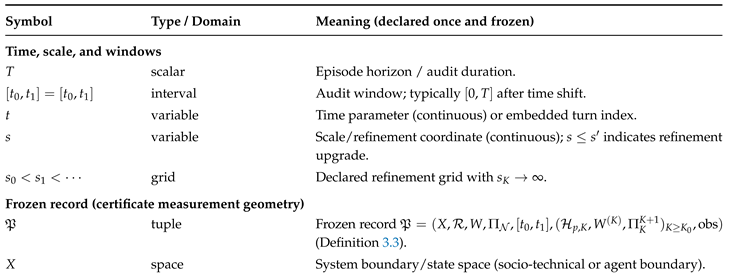

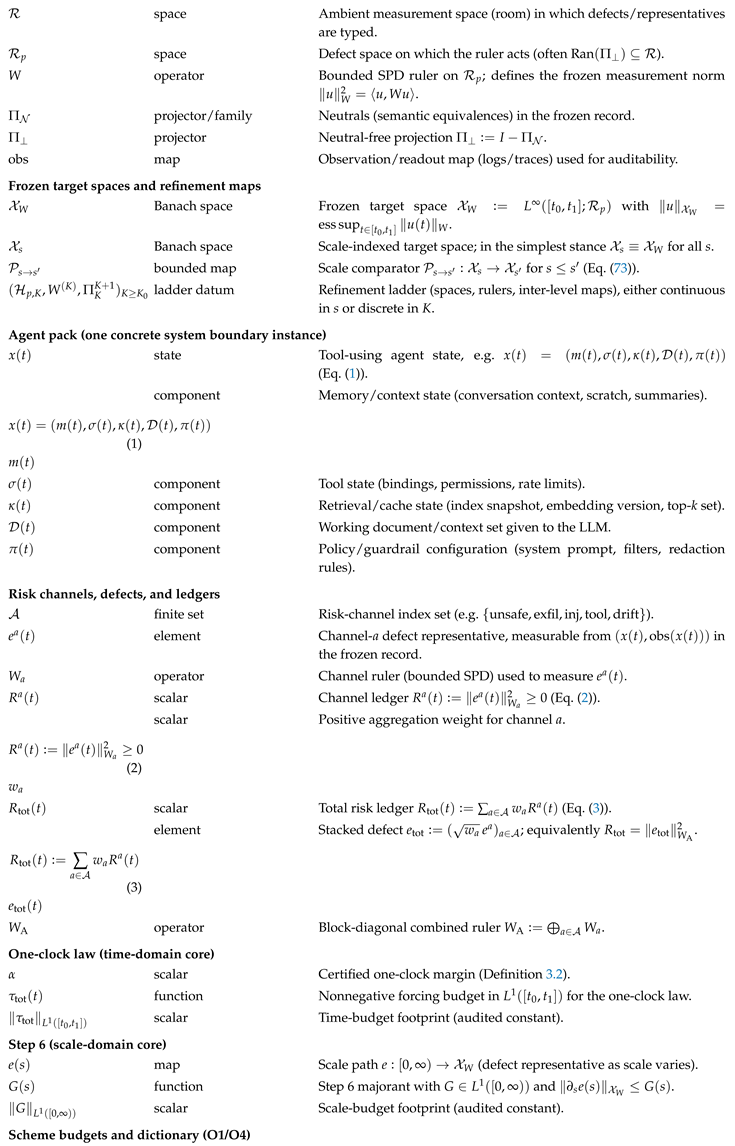

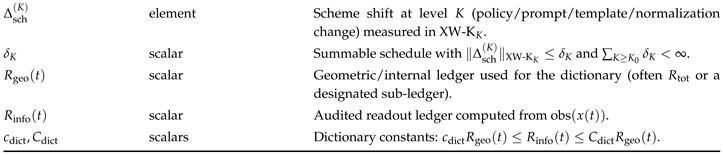

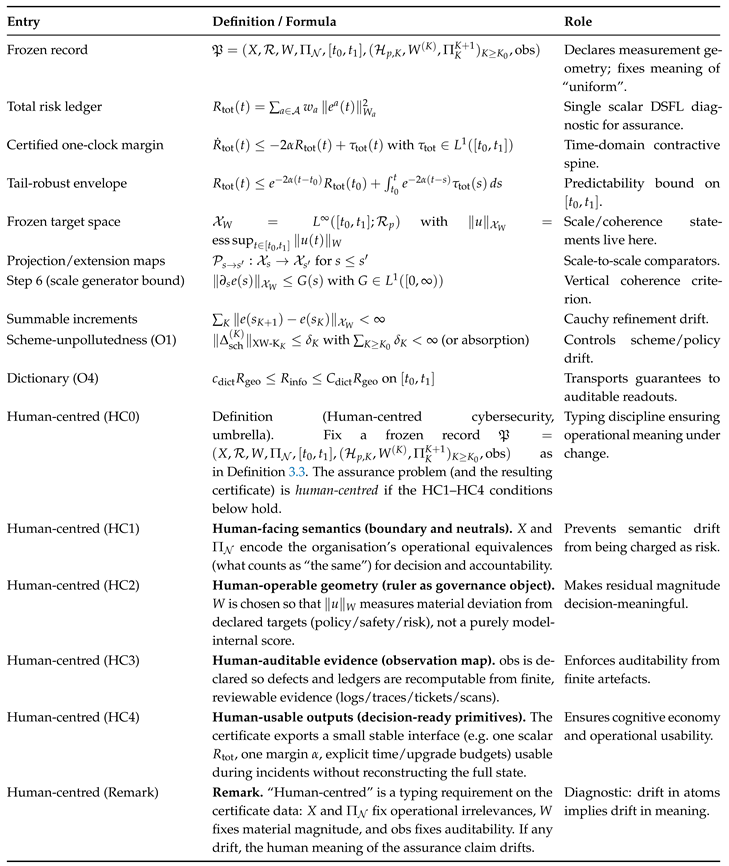

Master Definitions (Used Throughout)

1. Introduction

Modern digital systems evolve continuously: models are retrained, retrieval indices and schemas change, policy templates and guardrails are revised, scanners and severity rubrics are replaced, tool permissions are widened or narrowed, and monitoring pipelines are re-instrumented [

1,

2]. A familiar failure mode follows: even when a control or mitigation is unchanged, the

meaning of the assurance claim can drift because the

measurement geometry drifts. In practice this happens whenever the evaluation pipeline changes—a new classifier, a new log schema, a new notion of what counts as a neutral reformulation of the same behaviour, or a new definition of the score itself [

1]. Teams and regulators then face a moving-goalpost pathology: “we improved” is asserted in a new metric that is not comparable to the old one [

3,

4].

This is not merely organisational; it is a typed mathematical fact. In stability theory, an exponential decay statement is a statement about a

specific generator acting on a specific normed space [

3,

4]. If the norm changes without explicit equivalence constants, statements like “uniform across discretisations” or “uniform across parameters” cease to be invariant [

3,

4]. The same logic governs assurance under upgrades: if the ruler, neutral conventions, or observation map drift, then the semantics of “risk is decreasing” drifts as well [

3,

4].

We introduce a proof-carrying certificate layer whose purpose is to prevent that drift. The core move is to declare and freeze a single operational record—the

frozen record—so that “uniform across upgrades” has a precise, mechanically checkable meaning [

1,

2]. The frozen record fixes: (i) a system boundary, (ii) a defect typing space, (iii) a single risk ruler (a frozen SPD norm), (iv) a neutral convention, (v) an audit window, (vi) a refinement ladder, and (vii) an observation map. Once these are declared, all guarantees are stated and checked in that geometry (or transported with explicit norm-transfer constants) [

2,

3,

4].

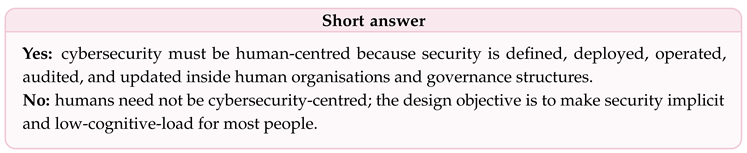

1.1. Why Cybersecurity Is Human-Centred by Construction

We use the term

human-centred (rather than merely

socio-technical) because the relevant security properties are

defined,

enforced, and

certified inside a control loop whose decision and verification operators are ultimately human-facing [

5,

6]. A security property in practice is not a free-floating predicate of a codebase or protocol; it is a property of a deployed system

as operated: policy authors declare constraints and acceptable risk; engineers implement mechanisms; operators triage and remediate; auditors demand evidence; and governance bodies revise requirements and priorities [

5,

6]. Thus the semantics of “secure” are fixed by human commitments, and the dynamics of “becoming secure” are constrained by human capacity [

6].

Formally, the deployed system closes a feedback loop

where each arrow is mediated by human practices and organisational processes [

5,

6]. Workflow structure, staffing constraints, alert fatigue, incentives, and governance cadence bound what controls can be deployed, how quickly deviations can be corrected, and what evidence can be produced and trusted [

6]. These constraints are not externalities; they determine the feasible set of implementations and therefore determine which formal guarantees remain valid after deployment [

5].

Even when a technical guarantee exists in principle (e.g. a verified component, a cryptographic reduction, a formally proved invariant), it becomes a security guarantee

in the world only after it is translated into procedures, interfaces, and audit evidence that humans can operate and maintain under continual change [

5,

6]. This translation introduces additional degrees of freedom (tooling updates, logging schemas, policy templates, exception processes) that can silently alter the meaning of a claimed guarantee unless the measurement and verification geometry are fixed and made checkable [

1,

3,

4]. In this sense, the “human-centred” qualifier is a typing requirement on the guarantee: the claim must be stated in a form that survives the human-operated update loop [

6].

Credential hygiene provides a concrete illustration. The well-documented tendency to choose weak or reused passwords when policies are burdensome, together with exception handling and workarounds under time pressure, are not edge cases but primary drivers of realised security outcomes [

7,

8,

9]. Any assurance architecture that treats these behaviours as exogenous anomalies will systematically mis-estimate risk and overstate robustness [

6,

9]. A human-centred formulation instead treats such effects as first-class: they appear as explicit forcing/injection budgets and as constraints on achievable improvement margins, making feasibility and auditability part of the guarantee rather than after-the-fact explanations [

6,

8].

Accordingly, an assurance claim is meaningful only if it is (i)

deployable (compatible with constraints on time and attention), (ii)

operable (actionable through a small set of decision variables), (iii)

auditable (supported by evidence that can be checked), and (iv)

maintainable under change (stable across tool upgrades, policy revisions, and environment drift) [

1,

2,

5,

6]. This paper treats these requirements as a typing discipline: the guarantee must be expressed in a frozen measurement geometry (ruler, neutrals, observation map, and ladder), with explicit budgets for what is not modelled, so that “improvement” remains comparable across versions [

3,

4].

At the same time, good human-centred security does

not require all humans to be cybersecurity-centred. The design goal is that most people can act normally without continuous security vigilance, while a small set of roles (operators, engineers, auditors, leaders) interact with security through stable, decision-ready interfaces [

6,

9]. In DSFL terms, this means concentrating security cognition into auditable primitives (one residual, one clock, explicit budgets and slack), rather than distributing it across the entire user population [

6,

8].

The certificate layer is introduced precisely as a

human-facing interface for guarantees: it reduces drifting dashboards to a small set of typed, auditable objects (rates, budgets, slack) that can be checked and governed [

1,

2].

1.2. Problem Statement

We study a verification problem common to modern human-centered security systems, including AI-enabled ones [

5,

6].

Given a deployed system that evolves in time and across refinement scales (tool versions, policy revisions, monitoring pipelines, model and retrieval updates), can we produce a proof-carrying, refinement-invariant safety envelope that is (i) meaningful under upgrades, (ii) compositional across coupled risk channels, and (iii) auditable from a finite bundle?

Our target output is a

certificate that can be shipped with a release and checked by a third party, in the spirit of proof-carrying and runtime-verifiable claims [

1,

2]. The certificate must be explicit about its typing: what is being measured (defects), in what geometry (ruler), modulo what equivalences (neutrals), over what interval (audit window), and along what upgrade path (ladder) [

3,

4].

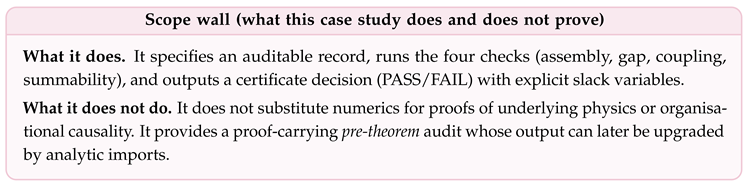

1.3. Scope and Non-Claims

Scope

We develop a proof-carrying DSFL certificate calculus for assurance under change in human-centered security systems, with a primary focus on tool-using LLM agents. The calculus fixes a frozen measurement geometry (ruler, neutrals, observation map, audit window) and treats upgrades as a refinement ladder, so that “uniform across versions” has a checkable meaning [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As an auxiliary

avatar-chain validation domain, we use quantum-computing refinement indices (code distance, concatenation level, circuit depth, decoder granularity) to stress-test the ladder semantics and the bundle-and-checker workflow in a controlled setting [

10,

11,

12].

Non-Claims

We do

not propose a new cryptographic primitive, a new intrusion-detection algorithm, or a new vulnerability scoring standard [

5]. We do

not claim to solve alignment or to give a complete semantics of natural language. We do

not claim that quantum computing and cybersecurity share physical content; the connection is methodological (typed stability under refinement), not ontological [

3,

4,

10]. Where a brick is not proved in-text (e.g. a decay/ringdown gap in a declared ruler, or a domain-specific scheme-control classification), we mark it as an explicit import and state the norm-typing requirements needed to use it [

3,

4,

13,

14,

15].

1.4. Approach: Frozen Records, One-Clock Reduction, and Vertical Coherence

The framework is a verification calculus with two orthogonal axes:

time (how risk evolves on an audit window) and

scale (how guarantees survive upgrades and refinement) [

3,

4]. The governing rule is that every claim is interpreted in a

frozen record (ruler, neutrals, observation map, ladder), so that “uniform across versions” is a checkable statement rather than a narrative [

3,

4].

Time Axis (One-Clock Safety Envelope)

We model assurance as a

vector of nonnegative ledgers capturing heterogeneous contributors to risk, including human/organisational channels (workload, exception pressure) and technical channels (misconfiguration, identity exposure, data-handling violations, unsafe tool use, prompt-injection success) [

5,

6]. Channels interact through

nonnegative injections, yielding a cooperative comparison system of Metzler type [

16,

17]. Under a Hurwitz (small-gain) margin condition, positive-systems scalarisation collapses the ledger vector to a single scalar residual

obeying a forced contraction law on the audit window:

The constants

are the certificate’s time-domain content: a single improvement margin and a single disturbance footprint, stated in the frozen ruler. This is Lyapunov/semigroup stability expressed in proof-carrying form [

3,

4,

16,

18,

19].

Scale Axis (Refinement Ladders and Step 6)

Guarantees must survive upgrades: tool versions, policy templates, monitoring pipelines, model weights, retrieval indices, and schema changes [

1]. We treat upgrades as movement along a refinement ladder with defect representatives typed in a frozen target space

Vertical coherence is enforced by a Step 6 condition: refinement drift must have finite total footprint in the frozen norm (equivalently, summable increments on a discrete ladder, or an

scale-majorant in continuous scale) [

20]. This yields a projective-limit semantics: upgrade effects do not accumulate without bound, so the defect representative converges and the meaning of the certificate cannot drift arbitrarily across versions [

20].

Proof-Carrying Posture (Bundle-and-Checker Semantics)

A release ships a finite bundle: the frozen record, the constants/budgets instantiating the time- and scale-domain inequalities, and a minimal checker that verifies the inequalities in the declared geometry. This is the assurance analogue of proof-carrying code and runtime verification: ship evidence, verify cheaply [

1,

2].

1.5. Two-Domain Positioning and Avatar-Chain Method

The paper is operationally anchored in

human-centred cybersecurity and tool-using LLM agents, where the measurement-geometry drift problem is acute and governance demands auditable non-regression under change [

6]. At the same time, we use

quantum computing as a deliberately controlled “avatar chain”: a domain with explicit refinement indices (code distance, concatenation level, circuit depth, decoder granularity) where frozen rulers, ladder uniformity, and PASS/FAIL certificate checking can be stress-tested numerically [

10,

11,

12]. References to GR/QFT-in-curved-spacetime enter only as motivating instances of the same typed pathology (norm/gauge/scheme drift) and the same cure (frozen records + ladder coherence), not as a claim of shared physical content [

13,

14,

15,

21].

1.6. Main Contributions

-

C1

Frozen-record semantics for assurance under change. We formalise the typing data required to make cross-version claims invariant: a frozen defect room, a frozen SPD ruler, a neutral convention, an audit window, a refinement ladder, and an observation map. This prevents metric drift from being mistaken for safety improvement [

3,

4].

-

C2

A one-clock certificate for coupled risk channels. Under cooperative coupling and a Hurwitz margin condition, we prove a positive weighting reduces multiple ledgers to a single scalar residual obeying (4) with explicit budgets. The resulting envelope is tail-robust and mechanically checkable [

16,

17,

18,

19].

-

C3

A refinement-ladder coherence theorem (Step 6). We show that a summable refinement drift condition (or an

scale-generator bound) implies vertical coherence in the frozen target norm: upgrade effects have finite total footprint, yielding a well-defined limiting representative and an honest meaning for “uniform across upgrades” [

20].

-

C4

A Master Certificate with auditable obligations. We package the requirements as auditable obligations (scheme/dictionary control, uniform one-clock margin, vertical coherence, and dictionary transport). Passing these checks implies a refinement-invariant safety envelope on the declared audit window [

1,

2].

1.7. What This Paper Does Not Claim

This paper does not claim to solve alignment, to provide a complete semantics of natural language, or to reduce all safety questions to a single scalar in an absolute sense. All claims are

relative to the declared frozen record [

3,

4]. The point of the framework is to make that dependence explicit: when stakeholders disagree, the disagreement must appear as a disagreement about the frozen record (ruler, neutrals, observation map, ladder) or about which obligation fails—not as an unresolvable narrative dispute [

1,

2].

1.8. Roadmap

The paper is organised to move from motivation and typing discipline to certificate-level theorems, and finally to operational and governance implications.

Section 3 fixes the problem setting and design principles. It formalises human-centred cybersecurity as a dynamical verification problem, introduces residuals as distances to declared constraints, and explains why guarantees must be stated in a frozen measurement geometry to avoid moving-goalpost assurances [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Section 4 develops the certificate-layer mathematics. It defines defect rooms, frozen rulers, neutral conventions, and nonnegative ledger vectors, and establishes the comparison inequalities used throughout the paper [

3,

4].

Section 5 proves the core technical result: the one-residual, one-clock theorem. Starting from coupled nonnegative ledgers with cooperative (Metzler) structure, it shows how a single scalar residual with a certified contraction rate and explicit disturbance budget can be constructed, yielding tail-robust envelopes that are decision-ready and auditable [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Section 6 instantiates the framework for governance and compliance. Policy–practice mismatch is formalised as a typed imbalance operator, and compliance assurance is reframed as a provable contraction margin rather than a snapshot checklist [

5].

Section 7 introduces empirical coupling budgets. It explains how cross-channel interactions enter the certificate as explicit constants, and how conservative empirical bounds populate the Metzler comparison model used by the one-clock reduction [

16,

17].

Section 8 analyses feasibility under human and organisational constraints. It proves improvement-floor results that separate sustainable recovery rates from unavoidable disturbance footprints, making explicit when improvement targets are infeasible given staffing, workflow, and incident intensity [

6,

8,

9].

Section 9 addresses assurance under upgrades. It formalises refinement ladders, contractive comparators, and the Step–6 summability condition, proving that summable refinement drift yields version-stable, projective-limit semantics in a frozen measurement geometry [

20].

Section 10 specifies the proof-carrying audit architecture. It defines the certificate bundle, checker interface, PASS/FAIL semantics with slack, and the numerical diagnostics required to instantiate constants conservatively and reproducibly [

1,

2].

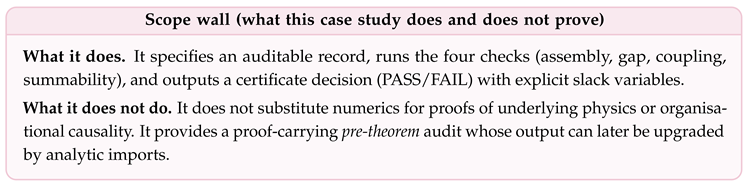

Section 11 demonstrates the workflow on a large block-structured avatar. The goal is not empirical validation of a threat model, but illustration of how frozen records, coupling budgets, gap estimates, and summability checks produce an auditable certificate decision [

3,

4].

Section 12 discusses implications for human-centred cybersecurity practice. It shows how the certificate layer yields decision-ready summaries, governance-grade non-regression guarantees, and a deployment model for adaptive AI and tool-using agents [

1,

2,

6].

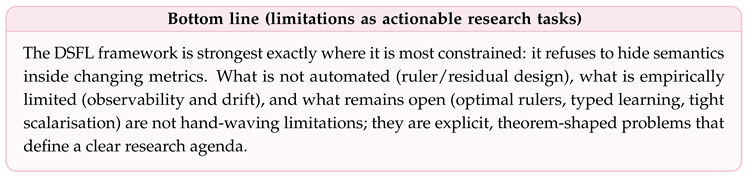

Section 13 records limitations and open problems. These include ruler and residual selection, observability constraints, empirical calibration challenges, and opportunities to tighten scalarisation bounds without losing auditability [

3,

4].

Section 14 summarises the contribution and outlines a concrete research and deployment agenda based on proof-carrying, frozen-record assurance under continual change [

1,

2].

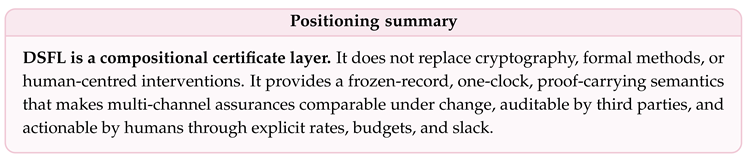

2. Positioning and State of the Art

This paper sits at an intersection where several technically mature literatures still fail to

compose into a single, upgrade-stable assurance object [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In practice, organisations operate security guarantees over long horizons while the measurement pipeline evolves: policies change, tools are replaced, monitoring is re-instrumented, models are retrained, and schemas drift [

1,

5,

6]. The consequence is a moving-goalpost failure mode: improvements can be asserted in a new metric that is not typed back to the old one [

3,

4]. Our positioning is that this failure mode is not merely managerial; it is structural. A stability claim is typed by a specific evolution operator in a specific norm, and semantics drift is a loss of typing [

3,

4]. DSFL is offered as a compositional certificate layer whose purpose is to preserve meaning under change by freezing the measurement geometry and routing residual uncertainty into explicit budgets with PASS/FAIL slack [

1,

2,

16,

17].

2.1. The Position: Cybersecurity Is Human-Centered, but Guarantees Must Be Typed

Cybersecurity outcomes are not solely technical properties of software stacks. They are embedded in human behaviour, work practices, organisational culture, incentives, and (inter)national governance [

5,

6]. In operational terms, this means that security claims are determined by:

design (interfaces, defaults, and affordances that shape operator and user behaviour),

workflow integration (how precautions compete with productivity and latency constraints),

governance (policy revision, compliance instruments, accountability, and audit evidence),

adversarial and geopolitical context (crime, conflict, regulation, and standards).

A human-centred approach therefore requires guarantees that remain legible to stakeholders and resilient to organisational change [

5,

6]. The DSFL stance is that this demand can be made mathematically precise: a guarantee is only comparable across time and versions if it is stated in a frozen measurement geometry (a ruler, a neutral convention, an observation map, and a declared upgrade path) or transported with explicit equivalence constants [

3,

4].

2.2. State of the Art: Four Literatures That Do not yet Yield One upgrade-Stable Assurance Object

(i) Stability and Semigroups in Fixed norms (Typed Meaning)

Classical stability theory makes explicit that decay and contractivity are statements about a specific generator acting on a specific normed space [

3,

4]. This fixed-norm discipline is routine in PDE stability and control, but assurance practice often violates it by changing metrics as tools and policies evolve [

3,

4]. DSFL imports the discipline as a governing rule: one frozen ruler (no moving goalposts), and cross-version comparisons must either be nonexpansive in that ruler or carry explicit norm-transfer constants [

3,

4].

(ii) Positive Systems, Small-Gain, and Compositional Closure (Coupled Channels)

Multi-channel risk dynamics are naturally modelled as cooperative systems: one channel injects risk into another (workload into misconfiguration, identity drift into policy violations, tool use into exposure), and these injections do not cancel. Positive-systems theory provides sharp stability criteria (Metzler–Hurwitz / small-gain) and a scalarisation mechanism that collapses a nonnegative ledger vector to a single rate-and-budget envelope [

16,

17,

18,

19]. DSFL adopts these tools but changes the unit of output: coupling coefficients and Hurwitz margin become auditable certificate constants rather than modelling conveniences [

16,

17].

(iii) Proof-Carrying and Runtime-Verifiable Assurance (Ship Evidence, Verify Cheaply)

Proof-carrying code formalises a producer/consumer pattern: ship a compact artifact that a small checker can validate [

2]. Runtime verification similarly emphasises monitorable properties and checkable traces [

1]. Contemporary security assurance frequently lacks an analogous artifact for

assurance under change: audits often remain narrative, or rely on dashboards whose semantics drift [

1,

5]. DSFL positions the certificate bundle (frozen record + constants + witnesses + trace commitments) as the corresponding assurance artifact: a third party can re-check the inequalities in the declared geometry and obtain PASS/FAIL with slack [

1,

2].

(iv) Human-Centred Cybersecurity and Usable Security (Why Drift and Overload Are First-Order)

Usable security and human factors research has shown that security mechanisms fail when they impose cognitive overload, misaligned incentives, and unusable workflows, and that “noncompliance” is often an adaptive response to constraints rather than irrational error [

5,

6,

8,

9]. A recurring operational symptom is metric overload with semantic drift: practitioners cannot act on dozens of signals whose meaning changes as tools and policies evolve [

6]. DSFL targets this failure mode by collapsing heterogeneous signals into one scalar residual with an explicit contraction margin, an explicit disturbance budget, and explicit coupling constants, so that decision-making can be supported by a small set of stable, auditable objects [

16,

17].

2.3. Why a Compositional Certificate Is Still Missing

Across these literatures, what is still missing is a single composable certificate that simultaneously:

- (i)

fixes the meaning of “small defect” under upgrades by freezing the measurement geometry (or proving explicit norm-transfer constants) [

3,

4];

- (ii)

closes multiple interacting channels to one decision-ready “clock” with explicit coupling budgets and Hurwitz slack [

16,

17,

18,

19];

- (iii)

separates global security state from what bounded observers can actually audit via an explicit observation map [

1];

- (iv)

yields a proof-carrying artifact (bundle + checker) that supports third-party verification and non-regression narratives as PASS/FAIL inequalities rather than interpretive reports [

1,

2].

The DSFL contribution is precisely this compositional layer: a frozen-record discipline plus one-clock routing and upgrade-coherence (Step–6) budgets, producing version-stable assurance envelopes with explicit slack [

3,

4,

16,

17,

20].

2.4. Implications: Three Interfaces That Make Guarantees Operational

To connect the mathematics to practice, we organise the implications around three linked interfaces that are legible to operators, governance bodies, and engineers [

5,

6].

2.4.1. Decision Interface: Cognitive Economy Under Metric Drift

Problem

Operators face metric overload and semantic drift: scanner scores, alert counts, compliance percentages, and ML risk scores change meaning as tooling and policies evolve [

5,

6].

DSFL Response

We replace drifting indicators by one scalar residual in a frozen ruler, together with decision-ready constants: a certified improvement margin (one clock), an

disturbance footprint, and explicit coupling constants that explain why local improvements may fail to yield global improvement. The underpinning is the fixed-norm discipline of stability theory [

3,

4] combined with positive-systems scalarisation for coupled nonnegative ledgers [

16,

17].

2.4.2. Governance Interface: Continuous Assurance as a Contract

Problem

Traditional compliance is a point-in-time snapshot and does not control drift between audits [

5].

DSFL Response

We model compliance as a typed policy–practice imbalance residual measured in a frozen geometry and certify a contraction margin with an explicit budget on each declared audit window. Auditors verify inequalities over an interval and report PASS/FAIL with slack, rather than relying on checklists whose semantics drift [

1,

2,

3,

4].

2.4.3. Engineering Interface: Non-Regression for Adaptive AI and Evolving Systems

Problem

Adaptive systems change: new prompts, tools, updated policies, model updates, retrieval/index snapshots, and telemetry schemas [

1].

DSFL Response

We require proof-carrying semantics: upgrades are admissible only if their induced drift is controlled by explicit, summable/integrable budgets (vertical coherence), so that assurance meaning remains stable across versions and can be re-checked by a minimal checker, in the spirit of proof-carrying artifacts [

1,

2,

20].

3. Problem Setting and Design Principles

This section fixes the

typed problem setting in which all later theorems live. The central claim is that human-centred cybersecurity is

necessarily a dynamical, human-centered verification problem: a guarantee must remain meaningful under (i) disturbances, (ii) interventions, and (iii) upgrades that change the measurement pipeline [

5,

6]. We therefore set up (a) a controlled-process boundary, (b) a residual-based notion of equilibrium, and (c) a frozen measurement geometry that prevents “moving-goalpost” assurances. The mathematics is standard Lyapunov/semigroup stability in fixed norms [

3,

4,

22] combined with a proof-carrying interface notion [

1,

2].

3.1. Human-Centred Cybersecurity as a Dynamical System

Cybersecurity is inherently time-dependent and human-centered: human workflows, staffing constraints, alert fatigue, organisational incentives, and tool affordances interact with technical controls [

5,

6,

8,

9]. A mathematically honest assurance claim must therefore be a statement about the evolution of a system

over a window rather than a static checklist item [

5]. This motivates Lyapunov-style reasoning: one declares a target notion of “acceptable security” (equilibrium / compliance / safe operation), defines a scalar residual measuring distance to that target, and proves that the residual contracts (up to explicit disturbance budgets). This is the stability logic of dissipative dynamical systems and semigroup theory [

3,

4,

18,

22].

3.1.1. System Boundary and State

We model a deployed security-relevant human-centered system as a state trajectory

where

X is a state space that includes both technical configuration and human/organisational state. The purpose of introducing

X is not to claim that all human variables are directly observable, but to make the system boundary explicit: security outcomes depend on internal state, external disturbances, and interventions, and must therefore be stated as properties of a dynamical evolution [

5,

6].

Setup 3.1 (human-centered security system as a controlled process). Fix a finite audit window . Let X be a (typically high-dimensional) state space, and let denote the system state. We allow:

- (i)

interventions (training, patching, policy changes, access reviews, monitoring changes);

- (ii)

disturbances (attacks, outages, user error, vendor changes, workload spikes);

- (iii)

observations produced by an observation map (logs, telemetry, tickets, scans), declared precisely in subsec:frozen-geometry.

Why this Abstraction Is Necessary

A human-centred model must explicitly admit that (i) actions are mediated by procedures and tools, (ii) disturbances are unavoidable, and (iii) the observables are not the full state but a logged readout [

1,

5,

6]. This is exactly the setting in which Lyapunov and comparison principles give robust guarantees: one proves inequalities for nonnegative quantities extracted from the trajectory, rather than solving the full dynamics [

3,

4,

18,

19].

3.1.2. Equilibria as Constraints and Residuals as Distances

The central object is a nonnegative scalar residual

that measures distance from a declared target set

(e.g. compliance set, safe configuration set, or “acceptable risk” set) [

18,

19].

Definition 3.1 (Security equilibrium set and residual). Let be the declaredequilibrium(acceptable security) set. Asecurity residualis a measurable function such that for all and for . Along a trajectory we write .

Remark 3.1 (Residuals need not be literal distances).

In practice, R is often derived from a defect map and a ruler W (see subsec:residuals-vs-metrics), so . This includes squared-distance-to-constraint as a special case (when Φ is a constraint operator and ) [18].

To connect residuals to computation and audit, it is useful to give a canonical construction.

Setup 3.2 (Constraint residual via Hilbert projection).

Let be a Hilbert space, let be nonempty, closed, and convex, and define

Proposition 3.1 (Projection characterisation of squared-distance residual).

Under Setup 3.2, for each there exists a unique projection such that

and . Moreover, is nonexpansive: for all .

Proof. This is the classical projection theorem in Hilbert spaces (existence/uniqueness for closed convex sets and nonexpansivity of metric projections). □

Human-Centred Reading

This is the cleanest semantics for “distance to compliance”:

E is the set of compliant states in the declared semantics;

is the nearest compliant configuration; and

is the squared correction distance. The nonexpansivity of

is the formal template behind “admissible remediation steps do not worsen compliance” (see Section 3.3.3) [

18,

19].

3.1.3. Lyapunov Claims as Certificate Interfaces

We will aim to prove an

inhomogeneous Lyapunov inequality on

:

where

is a certified improvement margin and

is an explicit disturbance budget [

3,

4,

18,

19].

Definition 3.2 (Certified one-clock margin). The constant in (8) is called the certified one-clock margin.

Remark 3.2 (Why “

budgets” are the right contract).

The condition on τ expresses a finite footprint on the declared window. This matches operational practice: incidents can spike, but governance cares about cumulative impact and recovery [5,6]. Analytically, is exactly what yields tail-robust envelopes by the inhomogeneous Grönwall mechanism [18,23,24].

Theorem 3.1 (Tail-robust security envelope).

Assume R is absolutely continuous on and satisfies (8). Then for all ,

Proof. Rewrite (8) as

. Multiply by

, integrate from

to

t, and divide by the integrating factor. This is the standard inhomogeneous Grönwall argument [

23,

24]. □

Human-Centred Meaning

The envelope (9) is actionable: it tells an operator and an auditor (i) how fast the residual contracts when not being hit (margin

) and (ii) how much disturbance the organisation absorbed (budget

) [

5]. This is an explicit alternative to narrative assurance [

1,

2].

3.2. Frozen Measurement Geometry (“No Moving Goalposts”)

A central design principle is the

frozen record. All claims are stated relative to a declared measurement geometry consisting of: a ruler (norm), a neutral convention (semantic equivalences), an observation map, and a refinement ladder. Freezing this geometry ensures that statements such as “risk is decreasing” have invariant meaning across tool upgrades and policy changes [

3,

4]. Without this discipline, guarantees are ill-posed in the same sense that exponential stability claims are ill-posed when the norm changes with time or with the discretization index [

3,

4].

3.2.1. Definition of a Frozen Record

Definition 3.3 (Frozen record).

Afrozen record

is a tuple

where:

- (i)

X is the system state space (human-centered boundary);

- (ii)

is an ambient measurement space in which defect representatives are typed;

- (iii)

is a bounded SPD ruler on a defect space , defining ;

- (iv)

is theneutral convention(semantic equivalences), and is the neutral-free projection;

- (v)

is the audit window;

- (vi)

is a declared refinement ladder (tool versions, policy versions, monitoring pipelines);

- (vii)

is an observation map that produces auditable readouts (logs/telemetry) from trajectories.

All residuals, norms, coupling constants, and budgets are interpreted in the same frozen record .

Why Each Component Is Necessary

The ruler

W fixes the meaning of “small defect” [

3,

4]. Neutrals encode invariances (e.g. benign renamings, harmless formatting, approved compensating controls) so the residual does not punish representational accidents [

6]. The ladder records the fact that systems evolve. The observation map makes the claim audit-friendly: guarantees must be transportable to what humans can actually see, a principle aligned with proof-carrying and runtime-verification workflows [

1,

2].

3.2.2. A Formal “No Moving Goalposts” Impossibility Statement

If the measurement geometry is allowed to change arbitrarily, then stability claims can be made true by renorming. The following proposition formalises this pathology [

3,

4].

Proposition 3.2 (Ill-posedness of decay claims under uncontrolled re-norming).

Let X be a vector space and let be any trajectory with on . There exists a time-dependent norm on X such that the function decays exponentially at any prescribed rate: for every there exists a choice of with

Proof. Fix any reference norm and define a scalar weight . Define . Then , hence . □

Interpretation

Without a frozen ruler, any improvement claim can be manufactured by changing the measurement geometry [

3,

4]. In security practice this corresponds to “dashboard illusions”: changing a scanner, severity rubric, or instrumentation can create the appearance of improvement without changing reality [

5]. Thus, freezing the measurement geometry is logically required, not stylistic.

3.2.3. Neutrals as Semantic Equivalence Classes

Humans routinely treat some differences as irrelevant: renaming roles, reordering log lines, or choosing among equivalent policy templates [

6]. If a residual penalises such differences, it creates unnecessary work and reduces trust. We therefore explicitly declare neutrals [

6,

8].

Definition 3.4 (Neutral transformations).

Aneutral family

is a set (or finite-dimensional subspace) of transformations on the defect space that represent semantic equivalences. A residual isneutral-invariant

if for all , or at minimumneutral-stable

if there exist with

Design Principle

Neutrals make guarantees human-legible: they prevent certificates from depending on representational accidents [

6]. They are the human-centered analogue of gauge/neutral mode removal in stability theory [

3,

4].

3.3. Residuals Versus Metrics

We distinguish

residuals from ad-hoc metrics. A residual measures distance to a declared constraint or target set in a declared ruler, while a metric may be an arbitrary score that is not tied to an equilibrium notion [

3,

4]. Residuals govern action: they decrease under admissible updates and increase only under explicit forcing. This distinction is essential for auditability, compositional reasoning, and for making guarantees meaningful to humans [

5,

6].

3.3.1. Residuals as Distances to Constraints

Definition 3.5 (Constraint-residual form).

Let be a declared equilibrium/constraint set and let be a defect map such that iff . Given a frozen ruler on , define the residual

Why this Matters

A constraint-residual has falsifiable semantics:

is small only if the constraint defect

is small in the declared ruler. This makes the residual suitable for proof-carrying assurance: it can be recomputed from declared observations and checked [

1,

2].

3.3.2. Metrics as Scores and the Danger of Non-Transportability

A generic metric

may correlate with security, but without a declared ruler and declared equilibrium set, a score does not support stability reasoning [

3,

4]. In particular, a score may improve under changes that do not improve the underlying system (e.g. changes in scanners, thresholds, reporting) [

5]. Residuals avoid this by being typed in a frozen record (Definition 3.3) [

3,

4].

3.3.3. Admissible Updates: Why Residuals Support Compositional Reasoning

A key property of residuals is that they can be required to be nonincreasing under admissible updates, while all other effects are budgeted [

18,

19].

Definition 3.6 (Nonexpansive (admissible) update in a frozen ruler).

Let be a defect representative and let be the frozen ruler. An update map isW-nonexpansive

if

Proposition 3.3 (Residual monotonicity under nonexpansive updates). Let be a quadratic residual in the frozen ruler and let Ψ be W-nonexpansive. Then for all u.

Proof. Immediate: . □

Human-Centred Meaning

An admissible update is a

control primitive that cannot make the situation worse in the declared ruler [

18,

19]. This turns procedures into checkable contracts: a training module, an access-hardening script, or an automated remediation is admissible only if it is nonexpansive (or if its non-admissible effects are explicitly budgeted) [

1,

2,

5]. This is how residuals compose across teams, tools, and organisational interventions.

3.3.4. From Residuals to a Decision-Ready Scalar Ledger

Even when multiple residual channels are needed (identity, patching, misconfiguration, exfiltration, unsafe tool use), one can provide a single scalar ledger by aggregating them with positive weights and proving a one-clock inequality via positive-systems (Metzler) reduction [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The design principle is: use residuals (typed distances) as primitives so aggregation preserves meaning [

3,

4].

Remark 3.3 (Design summary).

The three design principles in this section are logically linked: (i) security must be treated dynamically (Lyapunov reasoning) [18,22], (ii) guarantees must be stated in a frozen measurement geometry (no moving goalposts) [3,4], and (iii) residuals (typed distances) are the correct primitives, because they admit nonexpansive admissible updates and explicit forcing budgets [16,17]. Together, these principles create the conditions under which human-centred assurance claims can be auditable and comparable [1,2].

4. Mathematical Framework

This section states the certificate-level mathematics used throughout the paper. The goal is to formalise three objects that are routinely blurred in security practice:

(i) what is being measured (defects / residuals),

(ii) how it is being measured (the ruler / frozen measurement geometry), and

(iii) how multiple channels compose into one auditable guarantee (one-clock closure). Our stance is functional-analytic: stability and decay are statements about an evolution in a fixed normed geometry [

3,

4]. The DSFL contribution is to make this typing explicit and to provide a reusable routing theorem that turns multiple nonnegative ledgers into one contraction law with explicit budgets.

4.1. Residual Spaces and Rulers

We formalise defect representatives as elements of a Hilbert space equipped with a symmetric positive definite (SPD) operator defining the ruler. The induced norm quantifies the size of deviations. Neutral directions encode semantic equivalences (e.g. role renamings, benign configuration permutations) and are explicitly projected out.

4.1.1. Hilbert Defect Room and the Frozen Ruler

Definition 4.1 (Defect room and frozen ruler).

Adefect room

is a pair where is a real Hilbert space. Aruler

is a bounded, selfadjoint, strictly positive operator (SPD), written . The induced inner product and norm are

Afrozen recorddeclares W once, and all certificate claims are interpreted in .

Explanation. The insistence on a frozen ruler is not stylistic. In semigroup stability theory, exponential decay is a statement about a specific generator in a specific norm [

3,

4]. Changing the norm without explicit equivalence constants changes the meaning of the decay claim. The frozen ruler principle is the mechanism that prevents “metric overload” and “version drift” from becoming mathematically invisible.

4.1.2. Neutral Directions and Semantic Equivalence

In security, different configurations may be semantically equivalent even when they are not bitwise identical: renaming roles, permuting hosts, or changing identifiers may not change the risk semantics. We represent such equivalences by a finite-dimensional neutral subspace and remove it explicitly.

Definition 4.2 (Neutral subspace and projection).

Let be a closed subspace (typically finite-dimensional), called theneutral space

. Let denote the W-orthogonal projector onto , i.e. the complement with respect to . Given a raw defect , theneutral-free defect

is and the corresponding residual is

Explanation. Neutrals are part of the typing data. If one changes the neutral convention mid-argument, the residual changes meaning. Projecting neutrals out is the certificate analogue of quotienting by a semantic equivalence relation. (For the analogous role of “neutral modes” in stability statements, see standard semigroup/PDE treatments [

3,

4].)

4.1.3. Norm Transfer and “No Moving Goalposts”

Even when multiple tools produce different measurements, one can compare them only after proving norm equivalence.

Proposition 4.1 (Quantitative norm transfer between rulers).

Let be bounded SPD rulers on . Then there exist constants such that for all ,

Moreover, may be chosen as the extremal spectral values of the bounded SPD operator .

Proof.

is bounded, selfadjoint, and strictly positive, hence its spectrum lies in

with finite infimum and supremum. The Rayleigh quotient bounds

applied to

yield the claimed inequalities. □

Explanation. Proposition 4.1 is the exact mathematical statement behind “metric drift”: if you move between rulers without tracking

, you can manufacture apparent improvement or apparent degradation by changing the measuring stick. This is the same norm-typing phenomenon that governs transfer of decay estimates between energies in semigroup theory [

3,

4].

4.2. Multi-Ledger Systems

Realistic security systems involve multiple nonnegative residuals

, corresponding to different channels such as configuration drift, identity exposure, operational workload, or AI agent misuse. These ledgers interact through coupling terms and forcing budgets. This subsection formalises such systems at the certificate layer using standard cooperative/positive systems ideas [

16,

17].

4.2.1. Ledger Vector and Nonnegativity

Definition 4.3 (Nonnegative ledger vector).

Let index risk channels. Aledger vector

is a map with components

We interpret as a squared -norm of a neutral-free defect in a channel-specific defect room, and we regard the nonnegativity as the fundamental typing constraint that enables positive-systems routing [16,17].

Explanation. Working with nonnegative ledgers rather than signed metrics prevents cancellation artifacts. At the certificate layer, we only claim what can be audited: nonnegative quantities and explicit budgets.

4.2.2. Couplings and Forcing Budgets

Couplings represent how mismatch in one channel increases mismatch in another (e.g. operational overload increases misconfiguration risk; identity sprawl increases policy-violation likelihood). Forcing budgets represent exogenous injections (e.g. new vulnerabilities disclosed, business-driven policy change, staffing shocks). The cooperative comparison form below is standard in positive systems and input-to-state stability reasoning [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Definition 4.4 (Coupled ledger inequality with budgets).

We say the ledgers satisfy aDSFL comparison model

if r is absolutely continuous and

where:

- (ii)

is measurable andMetzlerfor a.e. t (off-diagonal entries );

- (ii)

is a nonnegative forcing vector with .

Explanation. The Metzler constraint encodes the principle that couplings act as

injections: they can feed risk from one channel into another but cannot cancel it. The

condition on

is the precise integrability hypothesis needed to obtain explicit envelopes (convolution bounds) for a scalar one-clock ledger [

18,

19].

4.3. One-Clock Reduction (Metzler Closure)

We introduce a comparison inequality in which the vector of ledgers is bounded by a Metzler matrix. Under a Hurwitz margin condition, the system admits a positive weighting that collapses all ledgers into a single scalar residual obeying a one-clock inequality. Intuitively, many interacting risks reduce to one certified rate of improvement. This is a classical positive-systems phenomenon [

16,

17].

4.3.1. Metzler Matrices and the Hurwitz Margin

Definition 4.5 (Metzler and Hurwitz).

A matrix isMetzler

if for all . It isHurwitz

if all eigenvalues have strictly negative real parts. Equivalently, its spectral abscissa satisfies [16,17].

Explanation. Hurwitzness is the quantitative statement “the coupled system is globally stable”. In DSFL, this is not assumed; it is certified by explicit inequalities (often LP-feasible conditions), as standard in control and positive systems [

16,

17,

18,

19].

4.3.2. One-Clock Theorem

Theorem 4.1 (One-clock reduction for Metzler-coupled ledgers).

Let be absolutely continuous and satisfy (20) with constant Metzler and . Assume M is Hurwitz. Then there exists a weight vector and a rate such that the scalar ledger

satisfies, for a.e. ,

Proof. Because

M is Metzler and Hurwitz, there exists

and

such that

(a standard positive-systems Lyapunov characterisation; see, e.g., [

16,

17]). Multiply (20) by

to obtain

using

. Set

and integrate the scalar differential inequality to obtain (23) (inhomogeneous Grönwall; cf. [

18,

19]). □

Explanation. Theorem 4.1 is the certificate kernel: once the channel couplings can be bounded so that the Metzler matrix is Hurwitz, the many-ledger system collapses to one auditable scalar inequality with explicit budgets. This is the precise sense in which “many risks reduce to one certified rate of improvement.”

4.3.3. Certificate-Friendly Feasibility Condition

The existence of with is particularly useful because it is a linear feasibility problem.

Proposition 4.2 (LP-form sufficient condition for a one-clock margin).

Let M be Metzler. If there exist and such that

then M is Hurwitz and the one-clock inequality (22) holds with .

Proof. The inequality gives a linear copositive Lyapunov witness for Metzler stability [

16,

17], implying Hurwitzness and enabling the scalarisation argument in the proof of Theorem 4.1. □

Explanation. Proposition 4.2 is the computational handle: it turns the abstract condition “system is stable” into an auditable check (feasible

w and margin

) that can be verified by linear programming on finite avatars, consistent with a proof-carrying workflow [

2].

4.3.4. Two-Channel Closed Form (for Intuition)

For two ledgers

with

Hurwitzness is equivalent to the small-gain inequality

and

is determined by the spectral abscissa of

M (equivalently the dominant eigenvalue for Metzler

M), yielding an explicit bottleneck formula (see standard treatments of

positive systems and small-gain conditions [

16,

17,

18,

19]). This is the simplest analytic avatar of the general Metzler closure.

Remark 4.1 (Why this framework is reusable).

Nothing in this section depends on the semantics of the ledgers (security, quantum computing, or quantum gravity). The only required inputs are: a frozen ruler, explicit neutral conventions, explicit coupling bounds, and integrable budgets. This is why the DSFL certificate layer can be reused across domains. In particular, the same one-clock reduction is standard in the analysis of cooperative systems and positive linear systems [16,17].

5. The One-Residual, One-Clock Theorem

This section gives the core certificate-layer result of the paper. We start from multiple nonnegative ledgers (risk channels) that interact through nonnegative couplings and external forcing. Under a standard positive-systems (Metzler) hypothesis and a Hurwitz margin condition, we prove that there exists a single scalar residual—a positive weighting of the ledger vector—that obeys a forced contraction inequality with one explicit decay rate and one explicit disturbance budget. This is the mathematically precise version of the human-centred question: “Are we improving, at what certified rate, and how much disturbance did we absorb?”

The proof is purely functional-analytic: it uses the comparison principle for cooperative systems, Perron–Frobenius theory for Metzler matrices, and the inhomogeneous Grönwall mechanism [

3,

4,

16,

17,

18,

19,

23,

24,

25].

5.1. Assumptions (Certificate Layer)

5.1.1. Ledgers, Regularity, and Forcing Budgets

Let

be a fixed audit window. We consider

m nonnegative ledgers (channels)

, collected into a vector

The certificate layer makes only minimal regularity demands: the ledgers must be absolutely continuous so that their time derivatives exist almost everywhere and can be bounded by inequalities [

18,

24].

Assumption 5.1 (A1: absolute continuity and nonnegativity). Each ledger is absolutely continuous on and satisfies for all .

External disturbances (attacks, outages, measurement noise, workload spikes) are not required to be small pointwise; they are required to have finite total footprint on the audit window. This is the correct currency for forced-stability envelopes and input-to-state style guarantees [

18,

19].

Assumption 5.2 (A2: integrable forcing). There exists a nonnegative forcing term with such that all disturbance contributions to ledger dynamics are upper-bounded by componentwise.

5.1.2. Metzler Comparison Inequality and Stability Margin

Cross-channel effects in human-centered security systems are inherently cooperative in the sense that one channel can inject risk into another but cannot cancel it. This is captured by a Metzler comparison inequality, the standard abstraction in positive-systems theory [

16,

17,

25].

Definition 5.1 (Metzler and Hurwitz). A matrix isMetzlerif for all . Its spectral abscissa is . We call MHurwitzif .

Assumption 5.3 (A3: cooperative (Metzler) comparison inequality).

There exists a constant Metzler matrix such that, for a.e. ,

Interpretation of M

Writing

and

(

), the diagonal rates

represent intrinsic dissipation/controls in channel

a, while the off-diagonals

represent injections from channel

b into channel

a. Hurwitzness is the small-gain condition: dissipation dominates injections [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Assumption 5.4 (A4: Hurwitz margin). The Metzler matrix M in Assumption 5.3 is Hurwitz: .

Why constant M Is Acceptable at the Certificate Layer

Allowing

time-dependent is possible, but the certificate layer aims for auditable constants. In practice, time dependence is either absorbed into the budget

or replaced by a conservative constant upper bound. This is consistent with certificate semantics: we prefer a slightly pessimistic but checkable bound to a sharp but unstable one [

17,

18,

19].

5.2. Main Theorem

5.2.1. Positivity and the Forced Comparison Formula

Lemma 5.1 (Positivity of the semigroup generated by a Metzler matrix). If M is Metzler, then has nonnegative entries for all .

Proof. Choose such that is entrywise nonnegative. Then is entrywise nonnegative. Hence is entrywise nonnegative. □

Lemma 5.2 (Forced comparison (Duhamel) bound).

Assume Assumptions 5.1 and 5.3. Then for all ,

Proof. Let

y solve

with

, so that Duhamel’s formula gives the right-hand side [

3,

4]. Set

. Then

and

a.e. Writing

yields

componentwise by Lemma 5.1. Hence

. □

5.2.2. One-Clock Reduction

We now construct the one scalar ledger that collapses multi-channel risk dynamics into a single certified clock. The key point is that Hurwitzness of a Metzler matrix implies the existence of a strictly positive weighting vector that turns the vector inequality into a scalar inequality with an explicit decay margin [

16,

17,

25].

Theorem 5.1 (One-residual, one-clock theorem (certificate layer)).

Assume Assumptions 5.1–5.4. Then there exist weights and a constant such that the scalar residual

satisfies, for a.e. ,

Moreover, a sufficient (and checker-friendly) witness condition is the existence of and such that

Proof. Since

M is Metzler and Hurwitz, positive-systems theory implies that there exists

with

[

16,

17,

25]. Fix any

such that (33) holds. Multiply the comparison inequality (29) on the left by

:

Since

componentwise and

componentwise, we have

which yields (32). Integrability of

follows from

and

. □

Security assurance interpretation

Theorem 5.1 provides a certificate-level contract: a single scalar ledger decreases at a certified rate

up to an explicit disturbance budget

. The weights

w encode how different risk channels contribute to the decision-ready residual. Crucially, the proof uses only inequality routing, so it remains valid even when the underlying system is complex, non-linear, or partially observed, as long as its effect on the ledgers is upper-bounded by the certificate assumptions [

18,

19].

LP-checkable certificate interface

Condition (33) is linear in

w and

. Thus a checker can validate (or produce) a one-clock margin by solving a linear feasibility problem: find

and

such that

. This makes the theorem operational for proof-carrying security bundles [

2].

5.3. Tail-Robust Envelopes

The one-clock inequality implies explicit envelopes that are robust to transient spikes. This is the mathematically precise reason the framework is human-centred: it distinguishes a persistent trend (rate

) from accumulated disturbance (budget

) [

18,

19,

23,

24].

Theorem 5.2 (Tail-robust envelope for the one-clock residual).

Assume the hypotheses of Theorem 5.1. Then for all ,

Proof. This is the inhomogeneous Grönwall argument applied to (32) [

23,

24]. □

5.3.1. Interpretation: Incidents as Budgets, Recovery as Rate

Transient Spikes

A short, intense incident produces a large

on a small time interval. The envelope (36) shows that its impact is filtered by an exponentially decaying kernel: its long-term effect is proportional to its

integrated footprint rather than its peak value [

18,

23,

24].

Recovery

When

returns to baseline, the residual returns to exponential decay at rate

. Thus the certificate separates “how hard we were hit” (

) from “how quickly we recover” (

) [

18,

19].

Human-Facing Assurance

In operational terms, Theorem 5.2 supports a minimal, interpretable assurance report:

These are the quantities a human decision-maker can use to compare interventions across versions without being misled by metric drift, provided the frozen record discipline holds (

Section 3) [

3,

4,

5,

6].

6. Compliance and Assurance as Imbalance

This section instantiates the DSFL certificate layer in a governance/compliance setting. The central move is to treat compliance not as a collection of heterogeneous checklist items, but as a typed imbalance in a frozen measurement geometry. Policy is the blueprint; operational practice is the response. The defect is the policy–practice mismatch; the residual is its squared norm in a frozen ruler; and assurance is a gap statement (a provable contraction margin with explicit budgets) rather than a binary label.

Throughout, we keep the DSFL hygiene:

every claim is stated in a declared normed space (frozen ruler), consistent with fixed-norm stability semantics [

3,

4];

semantic equivalences are encoded as neutrals and projected out (cf. the necessity of quotienting/removing neutral modes in stability statements) [

3,

4];

coupled compliance channels route through a positive-systems (Metzler) one-clock closure [

16,

17,

18,

19] (

Section 4).

6.1. Policy–Practice Imbalance Operators

We define imbalance operators for identity and access management, configuration state, data handling, and agent tool use. Each operator measures deviation between declared policy and observed practice and is designed to be compatible with auditability (finite evidence) and stability under change (frozen measurement geometry), in the proof-carrying spirit [

1,

2].

6.1.1. Typing: Blueprint Space, Practice Space, and Observation Map

Fix a regime window

(e.g. an audit period). Let

be the

policy blueprint space and

the

practice space, both Hilbert spaces, and let

be the calibration/interchangeability map that embeds a policy blueprint into the practice space. We also declare a neutral space

representing semantic equivalences (role renamings, asset relabelings, benign permutations), and a

W-orthogonal projector

onto

. Finally, we declare an observation map

(the measurement pipeline) that extracts practice evidence from logs, identity graphs, configurations, and agent traces. Making

explicit is essential for auditability: guarantees must transport to what is observable and checkable from evidence, not merely to an unobserved internal state [

1,

2].

Definition 6.1 (Policy–practice imbalance operator (abstract)).

Apolicy–practice imbalance operator

is a map

such that if and only if practice p satisfies policy s in the declared semantics. In DSFL form we take

possibly after composing p with the observation map and any declared normalisation.

Explanation. Definition 6.1 is a typed version of a common audit question: “how far is reality from policy, after quotienting away naming conventions?” The projector

enforces that only semantically meaningful mismatch is charged to the residual. The requirement that the operator be defined in a Hilbert space with a frozen ruler is exactly the fixed-norm discipline needed for meaningful contraction statements [

3,

4].

6.1.2. Concrete Imbalance Operators by Channel

We now record canonical examples. In each case, the DSFL rule is: define a typed defect that lives in a Hilbert space, then measure it in one frozen ruler. This makes compliance a candidate Lyapunov quantity rather than a checklist score.

Identity and Access Management (IAM)

Let

be the directed graph of identities, roles, entitlements, and resources at time

t. Let

be the policy blueprint (allowed edges, separation-of-duty constraints, MFA rules) and let

be the observed graph (from logs and identity systems). Define

where

is a declared feature/embedding of the graph into a Hilbert space (e.g. adjacency features, risk-weighted walk counts), and

removes neutral relabellings. Graph-to-Hilbert embeddings are a standard way to make structural constraints accessible to normed analysis; DSFL uses the embedding only as typing data (frozen in the record) so that cross-version comparisons remain meaningful.

Configuration State (Hardening Posture)

Let

denote the measured configuration vector (CIS controls, patch state, service exposure, runtime settings). Let

encode the target baseline. Define

where neutrals can encode benign reparameterisations (e.g. different but equivalent hardening profiles).

Data Handling and Governance

Let

be a measured data-flow and classification state (labels, access paths, retention). Let

encode policy constraints (e.g. retention limits, residency, encryption-at-rest). Define an imbalance

as the neutral-free distance of observed flows from the policy manifold, for example by a constraint-violation vector or by a quadratic penalty embedding. Treating governance requirements as constraints whose violation has a normed magnitude is standard in control-style assurance: it makes “how far from policy” a quantitative object suitable for Lyapunov reasoning [

18,

19].

6.2. Compliance Residuals

Compliance is quantified as a residual

in the frozen ruler. This formulation supports auditability and comparability, and it aligns directly with Lyapunov-style reasoning for controlled systems [

18,

19].

6.2.1. Frozen Ruler and the Compliance Residual

Definition 6.2 (Compliance residual in a frozen ruler).

Fix a frozen SPD ruler and define the neutral-free imbalance

Explanation. is a single scalar that aggregates heterogeneous violations by a declared measurement geometry. Because

W is frozen, statements like “compliance improved by a factor of 10” have invariant meaning over time and across tool updates (up to explicit norm-equivalence constants), mirroring the fixed-norm discipline in stability theory [

3,

4]. This is also the correctness condition for proof-carrying assurance: a third party must be able to recompute the residual in the same ruler from the declared evidence [

2].

6.2.2. Comparability Under Tool Changes

If the measurement pipeline changes (scanner upgrade, new log source), then the corresponding change of ruler must be made explicit; otherwise one can “improve” compliance by redefining the measurement geometry. This is the same pathology as ill-posed decay claims under uncontrolled renorming in fixed-norm stability theory [

3,

4].

Proposition 6.1 (Compliance comparability under ruler changes).

Let be two rulers representing two measurement pipelines. If there exist constants such that

then residual comparisons across the two pipelines are meaningful up to the explicit distortion factor . If no such equivalence constants are established, cross-version comparisons are not certificate-valid.

Proof. This is the norm-transfer fact for bounded SPD rulers; it is the same functional-analytic phenomenon that governs stability transfer between energies [

3,

4]. □

Explanation. Proposition 6.1 formalises the audit intuition: a new scanner may change the scale, so claims must carry the conversion constants. DSFL enforces this as a typing rule, consistent with the proof-carrying stance (ship explicit constants and verify them) [

2].

6.2.3. Multi-Channel Compliance as a Ledger Vector

Let

index compliance channels. Define

and assemble a residual vector

. Couplings (e.g. workload → misconfigurations) appear as nonnegative injections into the ledger inequalities, as in

Section 4; the resulting closure uses positive-systems/ISS reasoning [

16,

17,

18,

19].

6.3. Assurance as a Gap, not a Checklist

Instead of binary compliance, assurance is expressed as a rate of improvement toward policy conformance, with explicit slack. This is aligned with the control-theoretic view of safety under forcing and with the fixed-norm semantics of stability theory [

3,

4,

18,

19].

6.3.1. Assurance Means a Contraction Margin in the Frozen Ruler

A checkbox view treats compliance as static: PASS/FAIL at a time. DSFL treats assurance as dynamic: does the compliance residual contract with a certified margin under admissible operations?

Definition 6.3 (Assurance as a one-clock claim).

We say a system hasassurance with margin

on if there exists a scalar compliance ledger (typically a positive weighting of channel residuals) and a budget , , such that

Explanation. This is the typed analogue of “security is improving with provable slack, despite change.” The inequality is meaningful only in a frozen ruler, exactly as stability statements are meaningful only in fixed norms [

3,

4].

6.3.2. Metzler Closure Yields Assurance from Coupled Channels

If the channel residuals satisfy a Metzler comparison inequality (

Section 4), then assurance reduces to a Hurwitz-margin condition, as in the classical theory of positive linear systems and small-gain/ISS closure [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Theorem 6.1 (Assurance by one-clock reduction).

Assume the channel ledger vector satisfies

with M Metzler and . If M is Hurwitz, then there exist and such that satisfies the assurance inequality (49) with .

Proof. This is exactly the Metzler one-clock reduction (

Section 4), a standard positive-systems argument: Hurwitz Metzler ⇒ existence of

with

, then scalarisation yields the one-clock inequality [

16,

17,

18,

19]. □

Explanation. Theorem 6.1 is the mathematical core of “assurance as a gap”: assurance is a provable margin obtained from explicit coupling bounds, not a checklist score.

6.3.3. Slack Is the Audit Object

In a compliance programme, the most important number is not a binary label but the slack:

Positive slack means the system is contracting faster than it is being injected with mismatch; negative slack means the current policy–practice gap cannot be certified as closing under the declared operations.

Remark 6.2 (Why this improves accountability).

Slack variables are auditable: they reduce disputes about interpretation to inequalities in a frozen record. This is exactly the DSFL posture: progress is “numbers with slack,” not narrative conformance. This design aligns with proof-carrying assurance: the bundle ships constants and witnesses; the checker verifies inequalities and returns PASS/FAIL with slack [1,2].

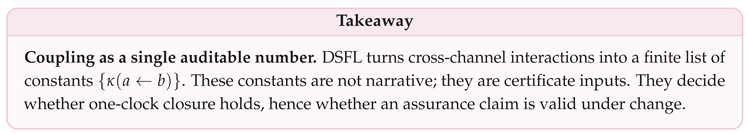

7. Empirical Coupling Budgets

This section explains how the DSFL certificate layer interfaces with empirical security operations. The core idea is simple: multi-channel assurances are only as strong as the coupling bounds that connect the channels. If workload spikes can inject risk into configuration drift, or if alert volume can inject risk into human error and policy exceptions, then a certificate that ignores these couplings is brittle. DSFL therefore treats coupling coefficients as first-class certificate constants: single numbers that must be declared, audited, and stress-tested.

Mathematically, the point is that the one-clock theorem (

Section 4Section 5) requires an explicit Metzler comparison system. Its off-diagonal entries are precisely the coupling budgets [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Hence, empirical coupling estimation is not “extra analytics”; it is the mechanism by which operational reality enters the certificate. Human factors motivate why coupling is first-order: under cognitive load and organisational constraints, interventions in one channel can amplify failures in another, so assurances that ignore coupling invite “local improvement / global regression” failure modes [

5,

6].

7.1. Why Coupling Matters in Security

Human workload, alert volume, and configuration drift influence each other. Ignoring these couplings leads to brittle assurances [

5,

6].

7.1.1. Coupling Is the Difference Between Local and Global Guarantees

Even if each ledger would decay in isolation (e.g. via automation or staffing interventions), coupling can defeat global contraction. A simple comparison model is

The coupled system contracts only if the induced Metzler matrix is Hurwitz (small-gain) and the forcing budgets are integrable, as in the stability theory of positive systems [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Thus, coupling constants are not optional: they are the difference between “each team metric improved” and “the organisation is provably safer” [

5].

7.1.2. Operational Meaning of Couplings

In practice, coupling mechanisms include:

Workload → misconfiguration: high alert load increases the probability of rushed changes and policy exceptions, inflating configuration residuals.

Misconfiguration → workload: drifting configurations create more alerts and incidents, inflating workload.

Identity sprawl ↔ policy violations: expanding entitlements increases both violation frequency and response overhead.

DSFL formalises these effects as nonnegative injections between ledgers, i.e. off-diagonal entries of a Metzler matrix. The certificate is only meaningful once these numbers are bounded in the frozen record. This is aligned with the human-centred security viewpoint that many “technical” failures are mediated by workflow and governance constraints rather than by missing primitives [

5,

6].

7.2. Model-Free Empirical Coupling Estimate

We define an empirical coupling constant

from observed time series and prove an immediate inequality bounding cross-channel injections. The goal is deliberately certificate-facing: produce conservative, auditable constants that can populate a Metzler comparison matrix and be used for one-clock closure [

16,

17].

7.2.1. From Coupled Inequalities to an Observable Injection Trace

At the certificate layer, coupling appears as a term that contributes to the derivative of a ledger. For two channels

a and

b, we write the abstract form

where

is the

injection trace measuring how channel

b feeds channel

a at time

t. In empirical settings,

is not derived from PDE identities; it is estimated from data by a declared protocol (e.g. regressions on interventions, causal models, or direct bookkeeping of change events). The DSFL requirement is not a particular statistical method; it is that the output be conservative and typed to the frozen record so that it can safely enter a Lyapunov/ISS-style inequality [

18,

19].

Remark 7.1 (Typing requirement). The injection trace must be expressed in units compatible with the residuals it couples. If and are computed in a frozen ruler, then must be derived from the same frozen data pipeline; otherwise the coupling estimate is not DSFL-typed.

7.2.2. Definition of the Empirical Coupling Constant

Definition 7.1 (Empirical coupling constant).

Fix a time grid and observed time series

with . For a small stabilisation parameter , define

Explanation. The normalisation

is certificate-friendly because it matches the Cauchy–Schwarz structure of cross terms and yields a dimensionless coupling coefficient; it is also the scaling used when routing bilinear interactions into Metzler/ISS-style scalar envelopes [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The small

prevents division by zero and is recorded as part of the frozen audit protocol.

7.2.3. Immediate Inequality (the Certificate-Ready Bound)

Proposition 7.1 (Empirical coupling inequality).

Let be as in Definition 7.1. Then for all ,

Proof. By definition, for each

,

Multiply both sides by to obtain (57). □

Explanation. Proposition 7.1 is deliberately elementary: it shows that once the time series are declared, the empirical coupling constant immediately yields a certificate-ready inequality. This is the DSFL posture: coupling claims are not interpretive; they are inequalities with explicit constants, designed to be routed into a one-clock certificate check [

1,

2].

7.2.4. From to a Metzler Comparison Form

To route coupling into the one-clock theorem we typically use the bound

so the inequality (57) yields a linear-in-ledgers injection bound of Metzler type:

Thus empirical couplings become explicit off-diagonal entries and diagonal penalties in the Metzler matrix used for one-clock closure [

16,

17,

18,

19].

7.3. Interpretation as a Certificate Constant

The coupling constant enters assurance reports as a single auditable number, with robustness under resampling. This is the empirical analogue of theorem constants in proof-carrying and runtime-verifiable workflows: ship a conservative constant plus a declared protocol, and verify the resulting inequality cheaply [

1,

2].

7.3.1. Certificate Semantics: What Means

In DSFL, is interpreted as:

The worst-case observed rate (in the declared frozen record) at which channel b can inject mismatch into channel a, normalised by the geometric mean of the two residuals.

Large

means “tight coupling” and predicts that local improvements may not yield global improvement unless diagonal gaps are large enough to dominate couplings (small-gain) [

16,

17,

18,

19].

7.3.2. Robustness Under Protocol Variation and Resampling

A single max-over-time estimate can be noisy. DSFL therefore treats robustness as part of the certificate, in the same spirit as conservative constant selection in verification and runtime monitoring [

1,

2].

Definition 7.2 (Robust empirical coupling constant (grid/seed worst case)).

Let be a finite grid of protocol settings (window choice, smoothing, downsampling, feature set) and a finite set of resampling seeds (bootstraps). Define

where is computed from the time series produced by protocol .

Explanation. is a conservative certificate constant: it is designed to be hard to “pass by luck”. It preserves the DSFL typing discipline (same ruler, same semantics) while stabilising the estimate against plausible measurement perturbations [

18,

19].

7.3.3. How Appears in an Assurance Report

In a proof-carrying assurance report, the couplings appear as explicit entries of the Metzler matrix

M used by the one-clock theorem (

Section 4). Concretely:

each off-diagonal coupling is instantiated by a conservative bound such as ;

diagonal terms include the certified gaps minus any diagonal penalties induced by coupling bounds;

the report records the slack in the Hurwitz margin condition (LP-feasible and witness ), not just the raw couplings.

This is exactly the certificate posture: coupling constants are not narrative; they are inputs to a checkable stability test [

2,

16,

17].

8. Floors and Feasibility Under Human Constraints

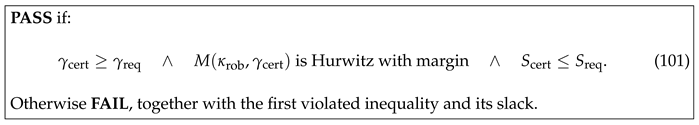

This section formalises a human-centred constraint that is routinely ignored in purely technical security models: security improvement has floors. Even when the underlying technical system is stabilisable, the achievable improvement rate is limited by human attention, staffing, organisational latency (change control, reviews), and workflow friction. From the DSFL certificate perspective, these limitations appear as bounds on (i) how large a dissipation margin can be sustained, and (ii) how large the disturbance footprint must remain. We therefore introduce mathematically precise floor quantities and prove a theorem that links persistent dissipation plus capacity-bounded forcing to a guaranteed improvement floor.