Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

01 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

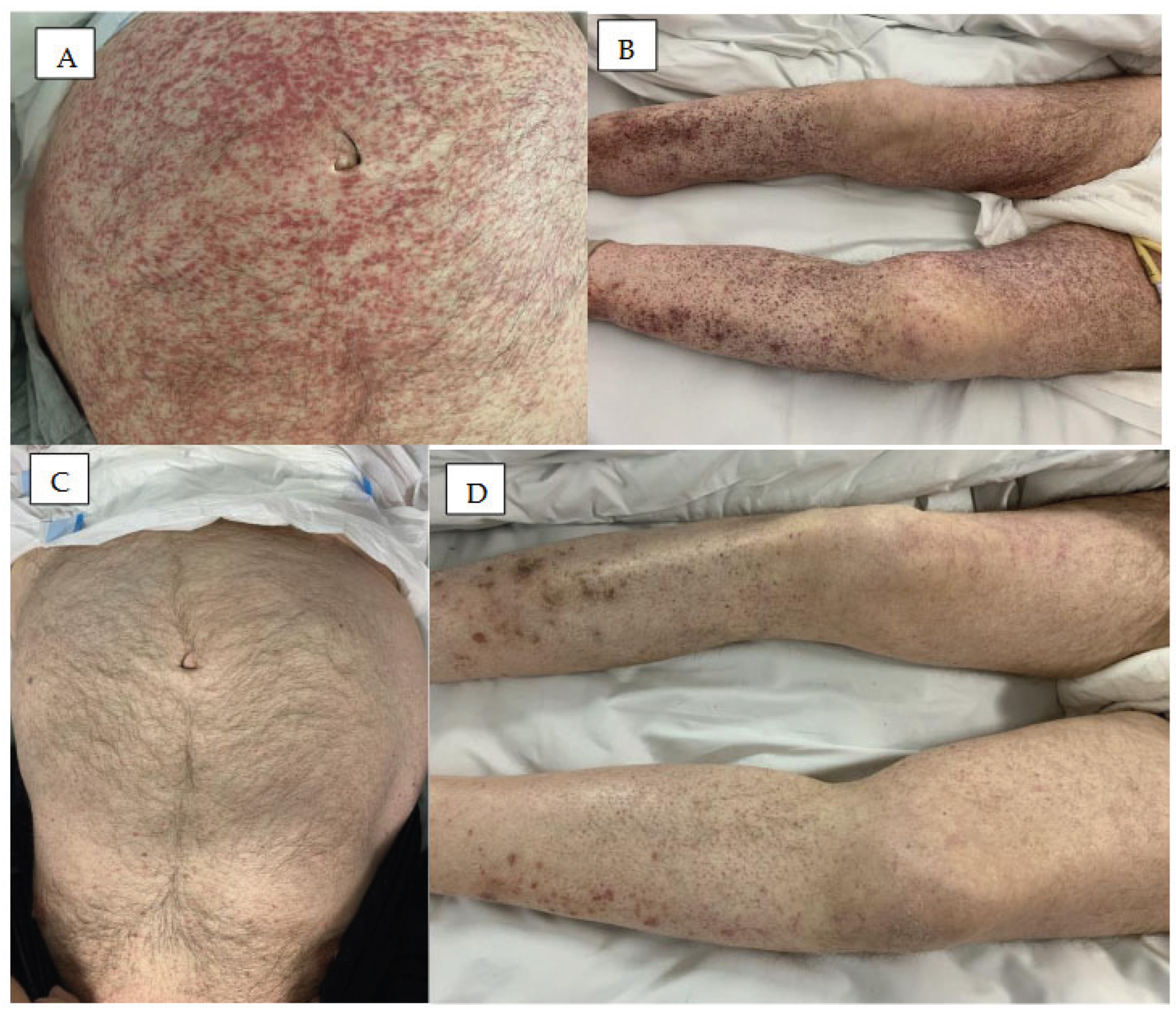

2. Hemoragic Symptoms in the Skin

3. Skin Rash

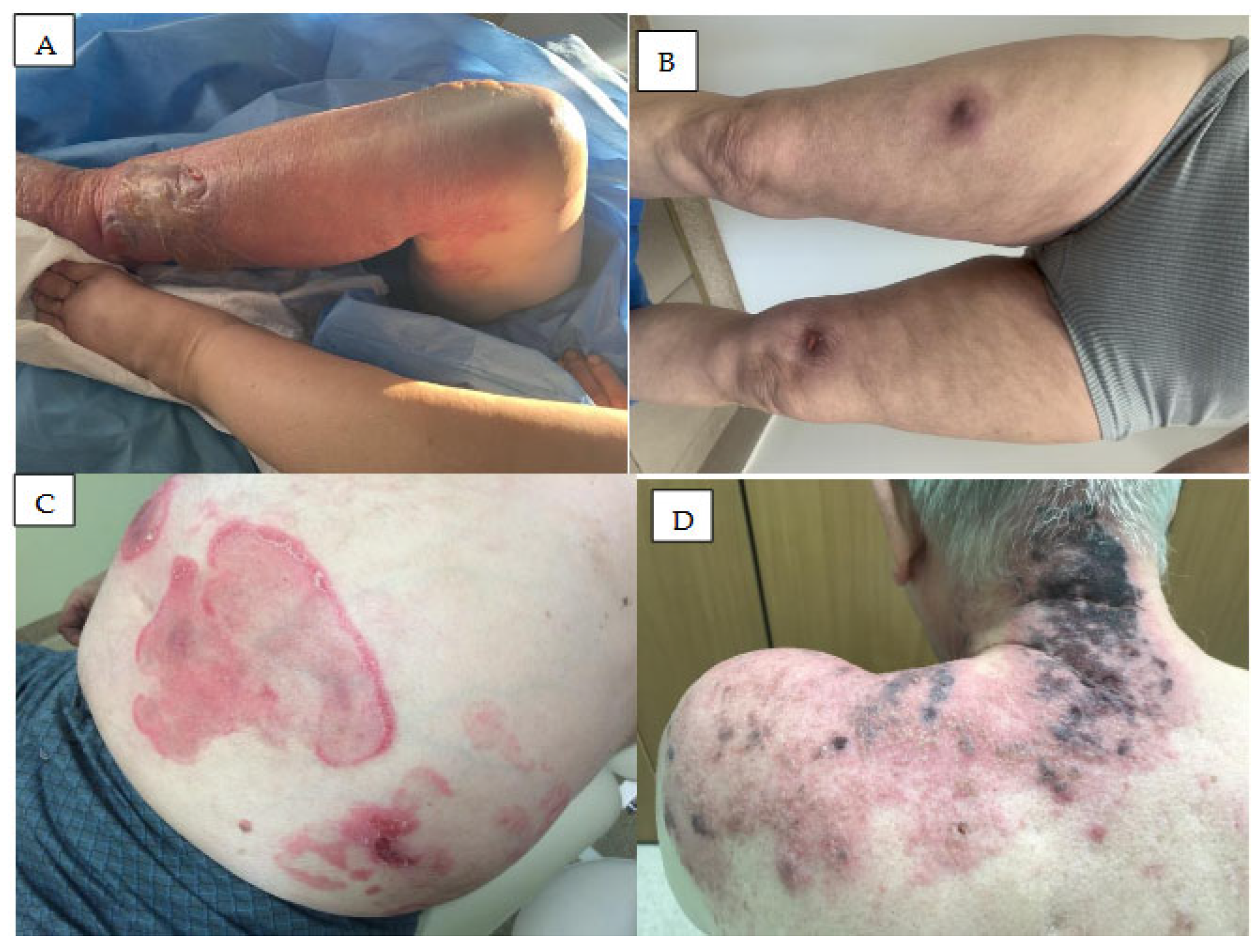

4. Vasculitis

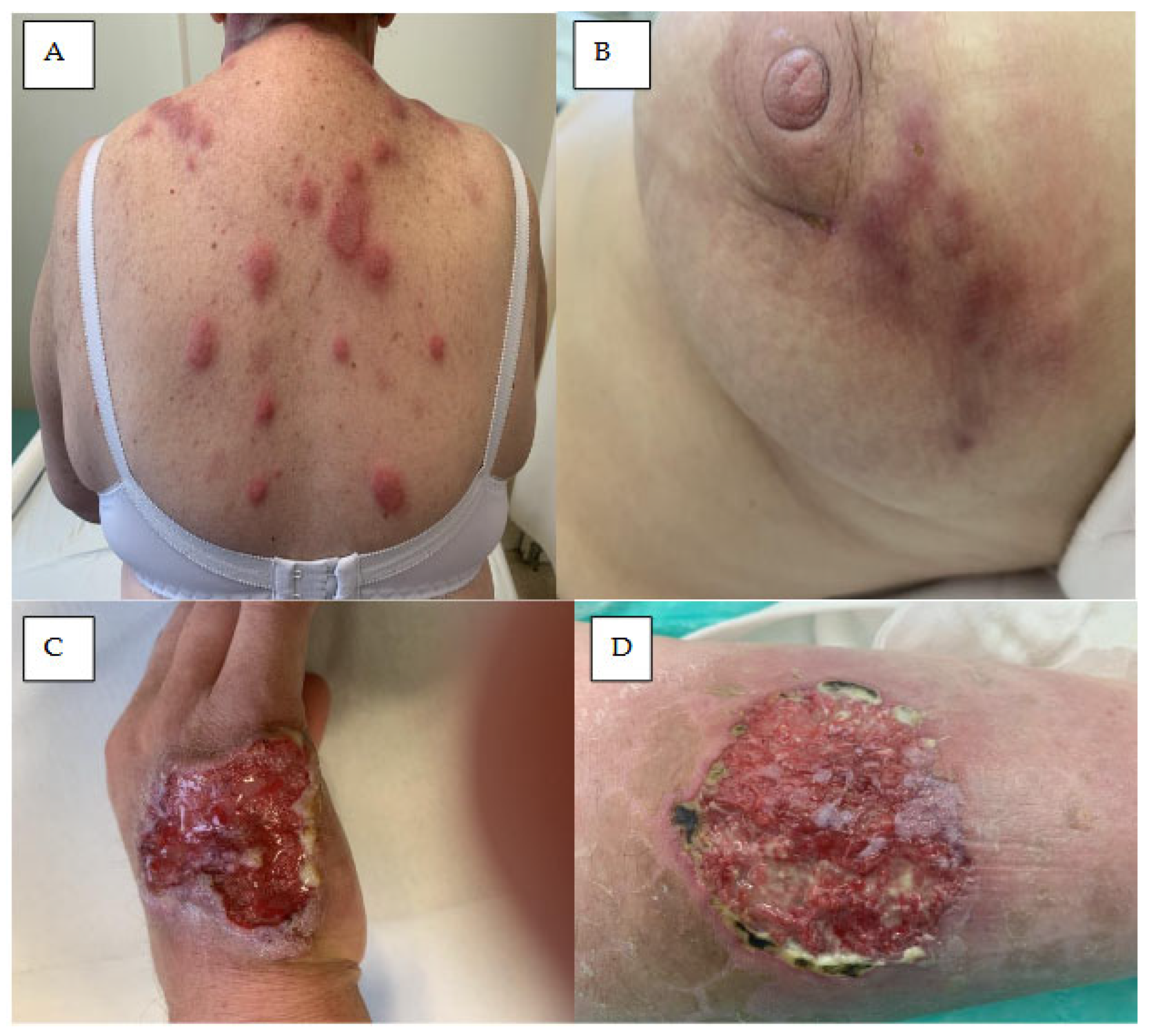

5. Neutrophilic Dermatoses

5.1. Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis

5.2. Neutrophilic Panniculitis

5.3. Pyoderma Gangrenosum

6. Skin Infections

7. Mucosal Symptoms

8. Nail Lesions and Hair Abnormalities

8.1. Nail Changes

8.2. Hair Changes

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robak, T.; Iskierka-Jażdżewska, E.; Puła, A.; Robak, P.; Puła, B. The Development of Novel Therapies for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia in the Era of Targeted Drugs. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Qian, H.; Liu, P. Inhibitors targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in cancers: drug development advances. Leukemia 2020, 35, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, T.; Witkowska, M.; Smolewski, P. The Role of Bruton’s Kinase Inhibitors in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Current Status and Future Directions. Cancers 2022, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falini, B.; Martino, G.; Lazzi, S. A comparison of the International Consensus and 5th World Health Organization classifications of mature B-cell lymphomas. Leukemia 2022, 37, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, E.; Robak, T. Bruton’s Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Immunological Diseases: Current Status and Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robak, T.; Witkowska, M.; Wolska-Washer, A.; Robak, P. BCL-2 and BTK inhibitors for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: current treatments and overcoming resistance. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2024, 17, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.B.; Ebata, K.; Randeria, H.S.; Rosendahl, M.S.; Cedervall, E.P.; Morales, T.H.; Hanson, L.M.; E Brown, N.; Gong, X.; Stephens, J.R.; et al. Pirtobrutinib preclinical characterization: a highly selective, non-covalent (reversible) BTK inhibitor. Blood 2023, 142, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puła, A.; Stawiski, K.; Braun, M.; Iskierka-Jażdżewska, E.; Robak, T. Efficacy and safety of B-cell receptor signaling pathway inhibitors in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 59, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’brien, S.M.; Brown, J.R.; Byrd, J.C.; Furman, R.R.; Ghia, P.; Sharman, J.P.; Wierda, W.G. Monitoring and Managing BTK Inhibitor Treatment-Related Adverse Events in Clinical Practice. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberri, D.J.; Kwong, B.Y.; Stevens, L.A.; Coutre, S.E.; Kim, J.; Sabile, J.M.; Advani, R.H. Ibrutinib-associated rash: a single-centre experience of clinicopathological features and management. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 180, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, J.D.; Kwong, B.Y. Cutaneous Adverse Events of Targeted Therapies for Hematolymphoid Malignancies. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017, 17, 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibaud, V.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Protin, C.; Vigarios, E.; Recher, C.; Ysebaert, L. Dermatological Toxicities of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, JP; Black-Shinn, JL; Clark, J; Bojena, B. Understanding ibrutinib treatment discontinuation patterns for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Blood 2017, 130, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mato, A.R.; Nabhan, C.; Thompson, M.C.; Lamanna, N.; Brander, D.M.; Hill, B.; Howlett, C.; Skarbnik, A.; Cheson, B.D.; Zent, C.; et al. Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica 2018, 103, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdy, M.S.; Mato, A.R.; Roeker, L.E.; Jarral, U.; Ujjani, C.S.; Shadman, M.; Skarbnik, A.; Whitaker, K.J.; Deonarine, I.; Kabel, C.C.; et al. Toxicities and Outcomes of Acalabrutinib-Treated Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Retrospective Analysis of Real World Patients. Blood 2019, 134, 4311–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, W.R. Cutaneous adverse reactions to Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Banal to brutal. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 1263–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Tan, S.Y.; Dewan, A.K.; Davids, M.; LaCasce, A.S.; Treon, S.P.; LeBoeuf, N.R. Cutaneous eruptions from ibrutinib resembling epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor–induced dermatologic adverse events. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, C.S.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Garcia-Sanz, R.; Trotman, J.; Opat, S.; Roberts, A.W.; Owen, R.G.; Song, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhu, J.; et al. Pooled safety analysis of zanubrutinib monotherapy in patients with B-cell malignancies. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tang, J.; Feng, J.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Miao, Y. Case report: Zanubrutinib-induced dermatological toxicities: A single-center experience and review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñán, H.Y.; Berglöf, A.; Zain, R.; Smith, C.I.E. Comparative Analysis of BTK Inhibitors and Mechanisms Underlying Adverse Effects. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, M.E. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocco, S.; Andriano, T.M.; Bose, A.; Chilov, M.; Godwin, K.; Dranitsaris, G.; Wu, S.; Lacouture, M.E.; Roeker, L.E.; Mato, A.R.; et al. Ibrutinib-associated dermatologic toxicities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2022, 174, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Moslehi, J.; Ewer, M.S.; O’BRien, S.M.; Ghia, P.; Cymbalista, F.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Fraser, G.; Rule, S.; Coutre, S.E.; et al. Incidence of and risk factors for major haemorrhage in patients treated with ibrutinib: An integrated analysis. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 184, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutre, S.E.; Byrd, J.C.; Hillmen, P.; Barrientos, J.C.; Barr, P.M.; Devereux, S.; Robak, T.; Kipps, T.J.; Schuh, A.; Moreno, C.; et al. Long-term safety of single-agent ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 3 pivotal studies. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shang, N.; Yan, Q.; Yue, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. Investigating bleeding adverse events associated with BTK inhibitors in the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 24, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatzel, JJ; Olson, SR; Tao, DL; McCarty, OJT; Danilov, AV; DeLoughery, TG. Ibrutinib-associated bleeding: pathogenesis, management and risk reduction strategies. J Thromb Haemost. 2017, 15(5), 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levade, M.; David, E.; Garcia, C.; Laurent, P.-A.; Cadot, S.; Michallet, A.-S.; Bordet, J.-C.; Tam, C.; Sié, P.; Ysebaert, L.; et al. Ibrutinib treatment affects collagen and von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet functions. Blood 2014, 124, 3991–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, A.H.; Farooqui, M.Z.; Tian, X.; Martyr, S.; Cullinane, A.M.; Nghiem, K.; Sun, C.; Valdez, J.; Niemann, C.U.; Herman, S.E.M.; et al. Incidence and risk factors of bleeding-related adverse events in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Haematologica 2015, 100, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mock, J.; Kunk, P.R.; Palkimas, S.; Sen, J.M.; Devitt, M.; Horton, B.; Portell, C.A.; Williams, M.E.; Maitland, H. Risk of Major Bleeding with Ibrutinib. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, C.; Pandit, Z.; Singh, H.; Al Omari, O.; Caughey, T.; Shapiro, D.S.; Lam, P. Imbruvica (Ibrutinib) induced subcutaneous hematoma: A case report. Curr. Probl. Cancer: Case Rep. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouchery, M.; Tomowiak, C.; Singier, A.; Puyade, M.; Dari, L.; Pambrun, E.; Pariente, A.; Bezin, J.; Pérault-Pochat, M.; Salvo, F. Bleeding risk with concurrent use of anticoagulants and ibrutinib: A population-based nested case-control study. Br. J. Haematol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hundelshausen, P.; Siess, W. Bleeding by Bruton Tyrosine Kinase-Inhibitors: Dependency on Drug Type and Disease. Cancers 2021, 13, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, R.R.; Byrd, J.C.; Owen, R.G.; O’bRien, S.M.; Brown, J.R.; Hillmen, P.; Stephens, D.M.; Chernyukhin, N.; Lezhava, T.; Hamdy, A.M.; et al. Pooled analysis of safety data from clinical trials evaluating acalabrutinib monotherapy in mature B-cell malignancies. Leukemia 2021, 35, 3201–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanna, N.; Tam, C.S.; Woyach, J.A.; Alencar, A.J.; Palomba, M.L.; Zinzani, P.L.; Flinn, I.W.; Fakhri, B.; Cohen, J.B.; Kontos, A.; et al. Evaluation of bleeding risk in patients who received pirtobrutinib in the presence or absence of antithrombotic therapy. eJHaem 2024, 5, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaïd, S.; Amini-Adle, M. Zanubrutinib-associated ecchymotic lesions. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e708–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samperio, V.M.; Ghonge, A.; Dasanu, C.A.; Dasanu, C. Zanubrutinib-Induced Symmetrical Soft Tissue Forearm Swelling in a Patient With Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilasi, S.M.; Luu, L.A.; Noland, M.M. Zanubrutinib-induced petechial ecchymotic reaction in a previously irradiated area in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 46, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharik, A.H.; Curkovic, N.B.; Chavez, J.C.; Tsai, K.Y.; Brohl, A.S.; Grichnik, J.M. Pseudoangiosarcoma and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a patient on a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 51, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, J.; Vecerek, N.; Worswick, S. Extensive ecchymotic patch in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 63, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Kim, J.; Wells, J. A uniquely distributed purpuric drug eruption from acalabrutinib. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2022, 63, E142–E144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbro, S.K.; Smith, S.M.; Dubovsky, J.A.; Gru, A.A.; Jones, J.A. Panniculitis in Patients Undergoing Treatment With the Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib for Lymphoid Leukemias. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberri, D.J.; Kwong, B.Y.; Stevens, L.A.; Coutre, S.E.; Kim, J.; Sabile, J.M.; Advani, R.H. Ibrutinib-associated rash: a single-centre experience of clinicopathological features and management. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 180, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirar, S.; Gogia, A.; Gupta, R.; Mallick, S. Ibrutinib-Induced Skin Rash. Turk. J. Hematol. 2021, 38, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.B.; Stausbøl-Grøn, B.; Riber-Hansen, R.; D’aMore, F. Ibrutinib-associated skin toxicity: a case of maculopapular rash in a 79-year old Caucasian male patient with relapsed Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia and review of the literature. Dermatol. Rep. 2017, 9, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awan, F.T.; Schuh, A.; Brown, J.R.; Furman, R.R.; Pagel, J.M.; Hillmen, P.; Stephens, D.M.; Woyach, J.; Bibikova, E.; Charuworn, P.; et al. Acalabrutinib monotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who are intolerant to ibrutinib. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydas, S. Management of adverse effects/toxicity of ibrutinib. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2019, 136, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, W.; Hu, N.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, H.; Gao, L. Severe atypical skin disease in two patients with CLL/SLL after BTKi treatment—a case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1467891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, T.M.P.; Dhaliwal, D.; Krishnan, B. Acalabrutinib-Related Dermal Toxicities: A Next-Generation Diagnostic Challenge. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 160, S26–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasica, M.; Tam, C.S. Management of Ibrutinib Toxicities: a Practical Guide. Curr. Hematol. Malign- Rep. 2020, 15, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, C.; Sadeghian, A.; Sullivan, L.; Murina, A. Ibrutinib-associated pityriasis rosea–like rash. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Baeza, D.; Pérez-López, E.; Román-Curto, C.; Santos-Briz, A. Cutaneous Lymphocytic Vasculitis Due to Ibrutinib Therapy. Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas 2024, 115, 1073–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyers, J.T.; Liu, L.W.; Ossowski, S.; Goddard, L.; Kamal, M.O.; Cao, H. A rash in a hairy situation: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis at presentation of hairy cell Leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 1433–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, E.; Jesionek-Kupnicka, D.; Iskierka-Jazdzewska, E.; Janus, A.; Robak, T. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis at diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia successfully treated with vemurafenib and rituximab. Leuk. Res. 2021, 104, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannis, G.; Wu, D.; Dea, T.; Mauro, T.; Hsu, G. Ibrutinib rash in a patient with 17p del chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 90, 179–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Aras, I.; Kurtgöz, P.Ö.; Çakıroğlu, U. Ibrutinib-Associated Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Turk. J. Hematol. 2024, 41, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Salafranca, M.; García-García, M.; Yangüela, B.d.E. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands related to cocaine abuse. An. Bras. de Dermatol. 2021, 96, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.R. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 34–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Rizvi, H.; Ali, F.; Lebovic, D. Sweet syndrome: a painful reality. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammel, J.A.; Roth, G.M.; Ferguson, N.; Fairley, J.A. Lower extremity ecchymotic nodules in a patient being treated with ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAAD Case Rep. 2017, 3, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Halabi, L.; Cherif-Rebai, K.; Michot, J.-M.; Ghez, D. Ibrutinib-Induced Neutrophilic Dermatosis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renuy, J.; Fizazi, A.; Girard, C.; Dereure, O. Atypical Neutrophilic Dermatosis Induced by Ibrutinib: A Dose-Dependent Cutaneous Adverse Reaction. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 65, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Bayers, S.; Vandergriff, T. Self-limiting Ibrutinib-Induced Neutrophilic Panniculitis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, e28–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, J.J.; Nuovo, G.J.; Magro, C.M. Cutaneous, Purpuric Painful Nodules Upon Addition of Ibrutinib to RCVP Therapy in a CLL Patient: A Distinctive Reaction Pattern Reflecting Iatrogenic Th2 to Th1 Milieu Reversal. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2016, 38, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R. Pyoderma gangrenosum: An update. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2012, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławińska, M.; Barańska-Rybak, W.; Sobjanek, M.; Wilkowska, A.; Mital, A.; Nowicki, R. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2016, 126, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kridin, K.; Cohen, A.D.; Amber, K.T. Underlying Systemic Diseases in Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, B.; Ibatici, A.; Sola, S.; Brunasso, A.M.G.; Massone, C. Ibrutinib and Pyoderma Gangrenosum in a Patient With B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2020, 42, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnam-Rad, N.; Gheymati, A.; Jahangard-Rafsanjani, Z. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors-associated pyoderma gangrenosum, a systematic review of published case reports. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2021, 33, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinato, D.; Sharma, R. Imatinib induced pyoderma gangrenosum. J. Postgrad. Med. 2013, 59, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Gupta, P.; Vargas, J.; Kudelka, A.; Kobe, M.; Rocca, N. Ibrutinib-Induced Perianal Rash Complicated by Bacterial Infection in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e82952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estupiñán, H.Y.; Berglöf, A.; Zain, R.; Smith, C.I.E. Comparative Analysis of BTK Inhibitors and Mechanisms Underlying Adverse Effects. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.J.; Wilz, L.; Peterson, A. The Identification and Treatment of Common Skin Infections. J. Athl. Train. 2023, 58, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasoub, R.; Albattah, A.; Elazzazy, S.; Alokka, R.; Nemir, A.; Alhijji, I.; Taha, R. Ibrutinib-associated sever skin toxicity: A case of multiple inflamed skin lesions and cellulitis in a 68-year-old male patient with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia—Case report and literature review. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pr. 2019, 26, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, B.F.; Pauff, J.M.; Satyanarayana, G.; Talbott, M.; Warner, J.L. Systematic review of infectious events with the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2018, 100, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varughese, T.; Taur, Y.; Cohen, N.; Palomba, M.L.; Seo, S.K.; Hohl, T.M.; Redelman-Sidi, G. Serious Infections in Patients Receiving Ibrutinib for Treatment of Lymphoid Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.A.; Mousa, L.; Zhao, Q.; Bhat, S.A.; Byrd, J.C.; El Boghdadly, Z.; Guerrero, T.; Levine, L.B.; Lucas, F.; Shindiapina, P.; et al. Incidence of opportunistic infections during ibrutinib treatment for B-cell malignancies. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2527–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghez, D.; Calleja, A.; Protin, C.; Baron, M.; Ledoux, M.-P.; Damaj, G.; Dupont, M.; Dreyfus, B.; Ferrant, E.; Herbaux, C.; et al. Early-onset invasive aspergillosis and other fungal infections in patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood 2018, 131, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dousa, K.M.; Babiker, A.; Van Aartsen, D.; Shah, N.; A Bonomo, R.; Johnson, J.L.; Skalweit, M.J. Ibrutinib Therapy and Mycobacterium chelonae Skin and Soft Tissue Infection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, ofy168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.K.; Karri, S.; Reynolds, J.; Owsley, J.; Wise, A.; Martin, M.G.; Zare, F. Cutaneous Mucormycosis Following a Bullous Pemphigoid Flare in a Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patient on Ibrutinib. World J. Oncol. 2018, 9, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A.; Tedeschi, A.; Barr, P.M.; Robak, T.; Owen, C.; Ghia, P.; Bairey, O.; Hillmen, P.; Bartlett, N.L.; Li, J.; et al. Ibrutinib as Initial Therapy for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treon, S.P.; Tripsas, C.K.; Meid, K.; Warren, D.; Varma, G.; Green, R.; Argyropoulos, K.V.; Yang, G.; Cao, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Ibrutinib in Previously Treated Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.C.; Harrington, B.; O’brien, S.; Jones, J.A.; Schuh, A.; Devereux, S.; Chaves, J.; Wierda, W.G.; Awan, F.T.; Brown, J.R.; et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasoub, R.; Albattah, A.; Elazzazy, S.; Alokka, R.; Nemir, A.; Alhijji, I.; Taha, R. Ibrutinib-associated sever skin toxicity: A case of multiple inflamed skin lesions and cellulitis in a 68-year-old male patient with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia—Case report and literature review. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pr. 2019, 26, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.C.; Brown, J.R.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.C.; Kay, N.E.; Reddy, N.M.; Coutre, S.; Tam, C.S.; Mulligan, S.P.; Jaeger, U.; et al. Ibrutinib versus Ofatumumab in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigarios, E.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Jegou, M.; Oberic, L.; Ysebaert, L.; Sibaud, V. Dose-limiting stomatitis associated with ibrutinib therapy: a case series. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 185, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigarios, E.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Jegou, M.; Oberic, L.; Ysebaert, L.; Sibaud, V. Dose-limiting stomatitis associated with ibrutinib therapy: a case series. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 185, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, S.; Yarom, N.; Zadik, Y.; Kuten-Shorrer, M.; Sonis, S.T. The broadening scope of oral mucositis and oral ulcerative mucosal toxicities of anticancer therapies. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 72, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, C.; Farooqui, M.Z.H.; Valdez, J.; Saba, N.S.; Soto, S.; Bray, A.; Marti, G.; Wiestner, A.; Cowen, E.W. Hair and Nail Changes During Long-term Therapy With Ibrutinib for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2016, 152, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manica, L.A.H.; Cohen, P.R. Ibrutinib-Associated Nail Plate Abnormalities: Case Reports and Review. Drug Saf.—Case Rep. 2017, 4, 15–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Kerkhof, P.C.; Pasch, M.C.; Scher, R.K.; Kerscher, M.; Gieler, U.; Haneke, E.; Fleckman, P. Brittle nail syndrome: A pathogenesis-based approach with a proposed grading system. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 53, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.; Alghamdi, Y.; Alghamdi, A.; Albogami, D.B.; Shahada, O.; AlHarbi, A. Ibrutinib-Induced Paronychia and Periungual Pyogenic Granuloma. Cureus 2022, 14, e32943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqui, M.Z.H.; Valdez, J.; Martyr, S.; Aue, G.; Saba, N.; Niemann, C.U.; Herman, S.E.M.; Tian, X.; Marti, G.; Soto, S.; et al. Ibrutinib for previously untreated and relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with TP53 aberrations: a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jr., H.L.d.A.; Sartori, D.S.; Malkoun, D.; Cunha, C.E.P. Scanning electron microscopy of ibrutinib-induced hair shaft changes. An. Bras. de Dermatol. 2023, 98, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).