1. Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV) is among the most rapidly expanding arthropod-borne viral pathogens and continues to pose a serious global public health challenge, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions [

1]. The virus is transmitted primarily by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, whose geographic range has expanded in recent decades due to urbanization, globalization, and climate change. As a result, dengue virus transmission has intensified worldwide, placing more than 2.5 billion people at risk and leading to an estimated 50 million infections each year. Although the majority of dengue virus infections are asymptomatic or present with mild, self-limiting febrile illness, a significant proportion progress to severe disease manifestations such as dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. These severe clinical outcomes are characterized by plasma leakage, bleeding, and organ impairment and can be fatal, with mortality rates reaching up to 10% in the absence of timely and appropriate clinical intervention [

1,

2]. Consequently, early and accurate diagnosis of dengue virus infection is critical for reducing disease severity, improving patient outcomes, informing clinical management decisions, and limiting further viral transmission within affected communities.

Dengue virus is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Flavivirus, with a genome approximately 10.7 kb in length [

3]. During the acute phase of infection, viral replication occurs rapidly, resulting in high levels of viremia. Dengue virus RNA can therefore be readily detected in whole blood, serum, or plasma during the first several days following symptom onset, typically up to one week. This temporal window makes nucleic acid–based detection approaches particularly suitable for early-stage diagnosis. Among these, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays are widely regarded as the gold standard due to their high sensitivity and specificity and their ability to distinguish between dengue virus serotypes [

4,

5,

6]. However, RT-PCR relies on enzymatic amplification and requires sophisticated instrumentation, precise temperature control, and well-trained personnel. These requirements contribute to high operational costs, extended turnaround times, and dependence on centralized laboratory facilities, which limit the accessibility of RT-PCR–based diagnostics in resource-limited settings and point-of-care environments.

In contrast, rapid diagnostic tests based on the detection of viral antigens or host antibodies are easier to perform and do not require complex instrumentation [

7,

8,

9]. Despite these advantages, such tests often suffer from suboptimal sensitivity and inconsistent performance, particularly during the early stages of infection when antibody titers are low or antigen levels fluctuate. Cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses can further compromise diagnostic accuracy [

10,

11]. As a result, there remains a pressing need for alternative molecular diagnostic strategies that combine the sensitivity and specificity of nucleic acid–based methods with operational simplicity, low cost, and suitability for decentralized testing.

To meet this need, enzyme-free nucleic acid detection technologies that operate under ambient or isothermal conditions are receiving increasing attention. Toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions (TMDRs) represent a powerful and versatile mechanism for sequence-specific nucleic acid recognition without the need for enzymes [

12,

13]. In TMDRs, a single-stranded nucleic acid target initiates a strand displacement process by binding to a complementary toehold region, triggering a predictable and programmable hybridization cascade [

14]. This mechanism has been widely used in DNA and RNA sensing platforms due to its high specificity, tunable kinetics, and compatibility with simple assay formats [

15,

16,

17,

18]. In parallel, semiconductor quantum dots (Qdots) have emerged as highly attractive fluorescent probes for bioanalytical applications [

19,

20,

21]. Qdots offer several advantages over traditional organic fluorophores, including exceptional brightness, narrow and size-tunable emission spectra, and remarkable resistance to photobleaching. These properties enable sensitive and stable fluorescence detection, even at low target concentrations, and facilitate signal amplification and multiplexing. When combined with nucleic acid–based recognition strategies, Qdots provide a powerful means of visualizing molecular interactions with high sensitivity and robustness.

In this study, we describe a quantum dot–based nucleic acid detection platform for dengue virus RNA that operates at room temperature and does not require enzymatic amplification. The assay integrates surface-immobilized capture probes with TMDR-driven hybridization to achieve selective recognition of target RNA sequences. Upon binding of the target RNA, strand displacement reactions promote the formation of specific probe–target complexes, which are subsequently visualized through Qdot-based fluorescence labeling. This design enables both molecular recognition and signal amplification under isothermal conditions, simplifying assay operation and reducing dependence on specialized equipment.

Using a conserved region of the dengue virus genome as the target sequence, we demonstrate sensitive detection of viral RNA at femtomolar concentrations. The assay exhibits high specificity and functions reliably under ambient conditions, highlighting its potential suitability for decentralized and point-of-care diagnostic applications. Importantly, the modular nature of the probe design allows straightforward adaptation of the platform to other viral RNA targets by simply modifying the sequence of the capture and displacement probes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conjugation of NH₂-Functionalized Quantum Dots with Thiolated DNA Probes (DPP/DP-SH or AP-SH)

Amine-functionalized semiconductor quantum dots (NH₂-Qdots; emission maximum 525 nm, stock concentration 8 μM; Ocean NanoTech LLC) were chemically conjugated to thiolated DNA probes using a heterobifunctional crosslinking strategy. All coupling reactions were performed using reagents provided in the Amine Quantum Dots Conjugation Kit (Ocean NanoTech LLC, Catalog #OAK) unless otherwise specified.

Briefly, 30 μL of NH₂-Qdot solution was transferred into a low-binding microcentrifuge tube and mixed with 30 μL of the supplied coupling buffer to ensure optimal reaction conditions. To activate the surface amine groups on the Qdots, 20 μL of sulfosuccinimidyl 4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (Sulfo-SMCC; 10 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide) was added to the Qdot suspension. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with continuous gentle mixing to allow efficient formation of maleimide-activated Qdots.

Following activation, unreacted crosslinker was removed by gel filtration chromatography. The entire reaction mixture was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated G-25 desalting column, and the nanoparticle solution was allowed to fully enter the resin bed. Elution was performed by adding 0.3 mL of coupling buffer, and the first 0.3 mL fraction containing activated Qdots was collected. This fraction was immediately used for subsequent DNA conjugation to minimize hydrolysis of the maleimide groups.

Activated Qdots were reacted with thiolated DNA probes (DPP/DP-SH or AP-SH; sequences provided in

Table 1) at a molar excess ranging from 3-fold to 60-fold relative to Qdots to ensure efficient conjugation. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h with continuous mixing, allowing the thiol groups on the DNA to react selectively with the maleimide-activated Qdots through stable thioether bond formation. To terminate the reaction and block any remaining reactive maleimide groups, 10 μL of quenching buffer was added, followed by incubation for an additional 30 min at room temperature with continuous mixing.

The resulting Qdot–DNA conjugates were purified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 1 h to remove unbound DNA and reaction byproducts. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet containing Qdot–DNA conjugates was washed twice with 200 μL of washing buffer. After the final wash, the conjugates were resuspended in 200 μL of storage buffer and stored at 4 °C until use. All conjugates were protected from light during storage to preserve fluorescence integrity.

2.2. Immobilization of Thiolated Capture DNA on NH₂-Functionalized Glass Slides (CPP/CP-SH)

Glass microscope slides (25 × 75 mm) were used as solid support for capture probe immobilization. Six discrete detection areas were defined on the surface of each slide using a hydrophobic barrier to confine reagents and prevent cross-contamination between spots. Surface functionalization was performed using maleimide chemistry to enable covalent attachment of thiolated capture DNA probes.

Each detection area was treated with 15 μL of a 1 mM solution of maleimidocaproyloxysuccinimide ester (EMCS) prepared in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 8.5) containing 30% (v/v) DMSO to enhance solubility. The slides were incubated at room temperature overnight to allow efficient coupling of EMCS to surface amine groups on the glass. Following incubation, the slides were washed three times with 15 μL of 1× PBS (pH 7.4) to remove unreacted reagent.

Capture probe immobilization was then performed by incubating each spot with 15 μL of 0.2 μM thiolated capture DNA (CPP/CP-SH), which had been pre-annealed with its complementary protector strand to prevent nonspecific hybridization. The incubation was carried out at room temperature for 1 h, allowing the thiol groups on the capture DNA to react with maleimide-activated slide surfaces. After immobilization, the slides were washed three times with 15 μL of 1× PBS (pH 7.4) to remove unbound DNA. The prepared slides were used immediately or stored at 4 °C for short-term use.

2.3. Dengue DNA or RNA Detection

A conserved segment at the 3’ end of the dengue genome was selected as the target for the Qdot assay to ensure detection of all dengue serotypes and genotypes. The target was selected from an alignment of all complete or near-complete dengue virus genome sequences (>10,000bp) that were publicly available as of 20 August 2020. This region contains one degenerate base to account for difference between serotypes 1 and 3 versus 2 and 4.

For analytical detection, 10 μL of synthesized dengue DNA (AAACAGCATATTGACGCTGGGAAAGACCAGAGATCCTGCTGTCTC; Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) or dengue RNA (AAACAGCAUAUUGACGCUGGGAAAGACCAGAGAUCCUGCUGUCUC; prepared as described in the

Supporting Information) at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 pM was added to each detection area. Samples were prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl and 5% glycerol and incubated on the slide for 10 min at room temperature to allow target hybridization with immobilized capture probes.

Following incubation, the sample solution was removed, and each spot was washed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl to eliminate unbound targets. Subsequently, 10 μL of 1 nM Qdot-DP/DPP conjugate was added to each spot and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After washing three times with 20 μL of 1× PBS, fluorescence images were acquired using an Azure Imaging System with excitation at 488 nm and emission detection at 520 nm.

Next, 10 μL of 1 nM Qdot-AP conjugate was added to each spot and incubated for an additional 10 min at room temperature. After three washes with 20 μL of 1× PBS, the slide was scanned again under identical imaging conditions.

For detection of dengue viral RNA from crude total nucleic acid extracts, 10 µL of each sample containing 10 ng of RNA was analyzed using the same detection procedure described above. All experimental steps were performed at room temperature (25 oC).

3. Results

3.1. Design and Principle of an Enzyme-Free, Quantum Dot–Based RNA Detection Platform

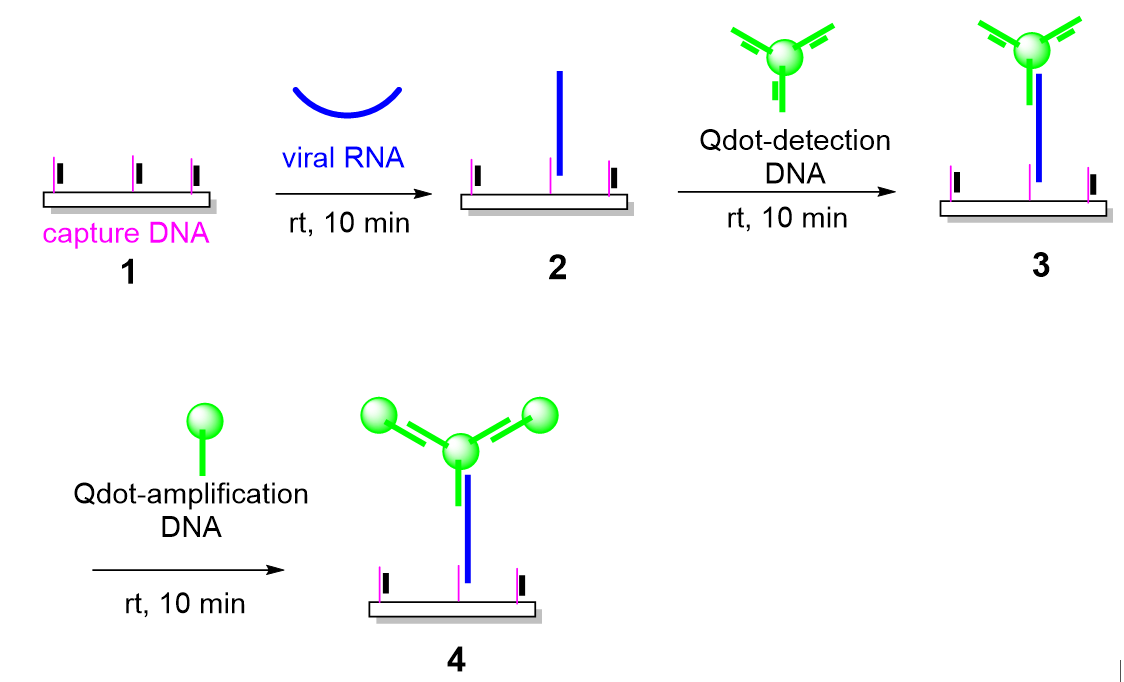

The overall strategy for enzyme-free dengue virus RNA detection is illustrated schematically in

Figure 1. The platform was designed to achieve high sensitivity and specificity under ambient conditions by integrating toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions (TMDRs) with quantum dot (Qdot)–based fluorescence generation and amplification. This hierarchical design enables stepwise target recognition and signal enhancement without the use of enzymatic amplification or thermal cycling.

The assay begins with surface functionalization of an amine-modified glass slide using a thiolated capture DNA probe. To suppress nonspecific hybridization and premature probe activation, the capture probe is initially hybridized with a complementary 15-nucleotide protector strand, forming a metastable duplex. In the absence of target RNA, this duplex remains intact and inactive. Upon introduction of the target viral RNA sequence, a single-stranded toehold region on the capture probe becomes accessible, allowing the target RNA to initiate a toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction. This process results in the displacement of the protector strand and stable hybridization of the viral RNA to the immobilized capture probe.

Following surface capture of the target RNA, signal generation is achieved through the binding of Qdot-conjugated detection probes. These detection probes are also initially protected by complementary strands and are activated only upon encountering the RNA–capture probe complex. A second TMDR mediates the hybridization of the detection probe to an adjacent region of the target RNA, bringing a fluorescent Qdot into close proximity with the surface. This step produces a measurable fluorescence signal that directly correlates with the presence of the target RNA.

To further enhance assay sensitivity, a third layer of signal amplification is introduced using Qdot-conjugated amplification probes. These probes bind to the detection probe–Qdot complex through an additional TMDR, effectively increasing the number of fluorescent labels associated with each captured RNA molecule. This multistage, enzyme-free amplification strategy enables strong fluorescence output even at very low target concentrations. Importantly, all recognition and amplification steps occur at room temperature and rely solely on predictable nucleic acid hybridization kinetics.

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of DNA–Quantum Dot Conjugates

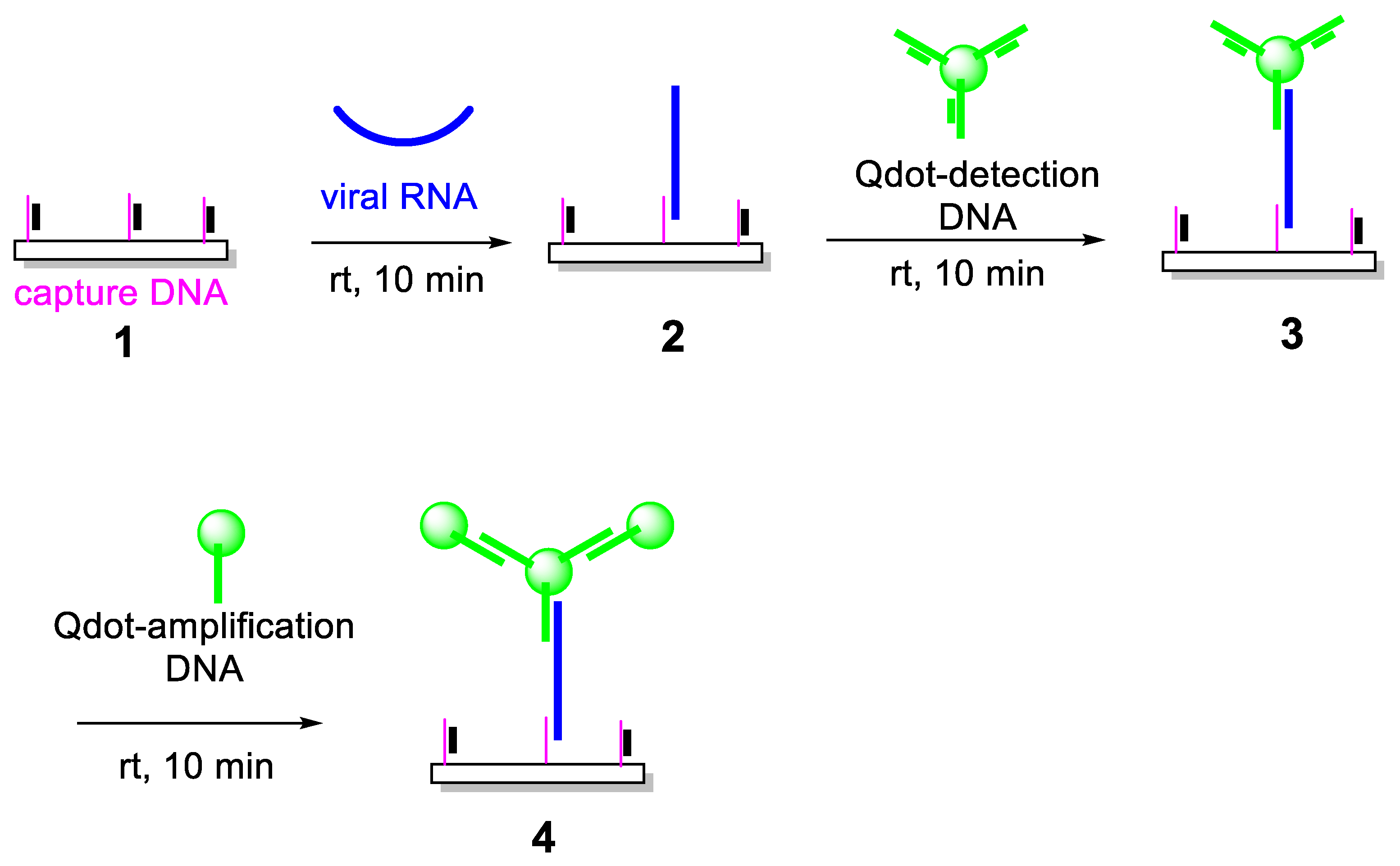

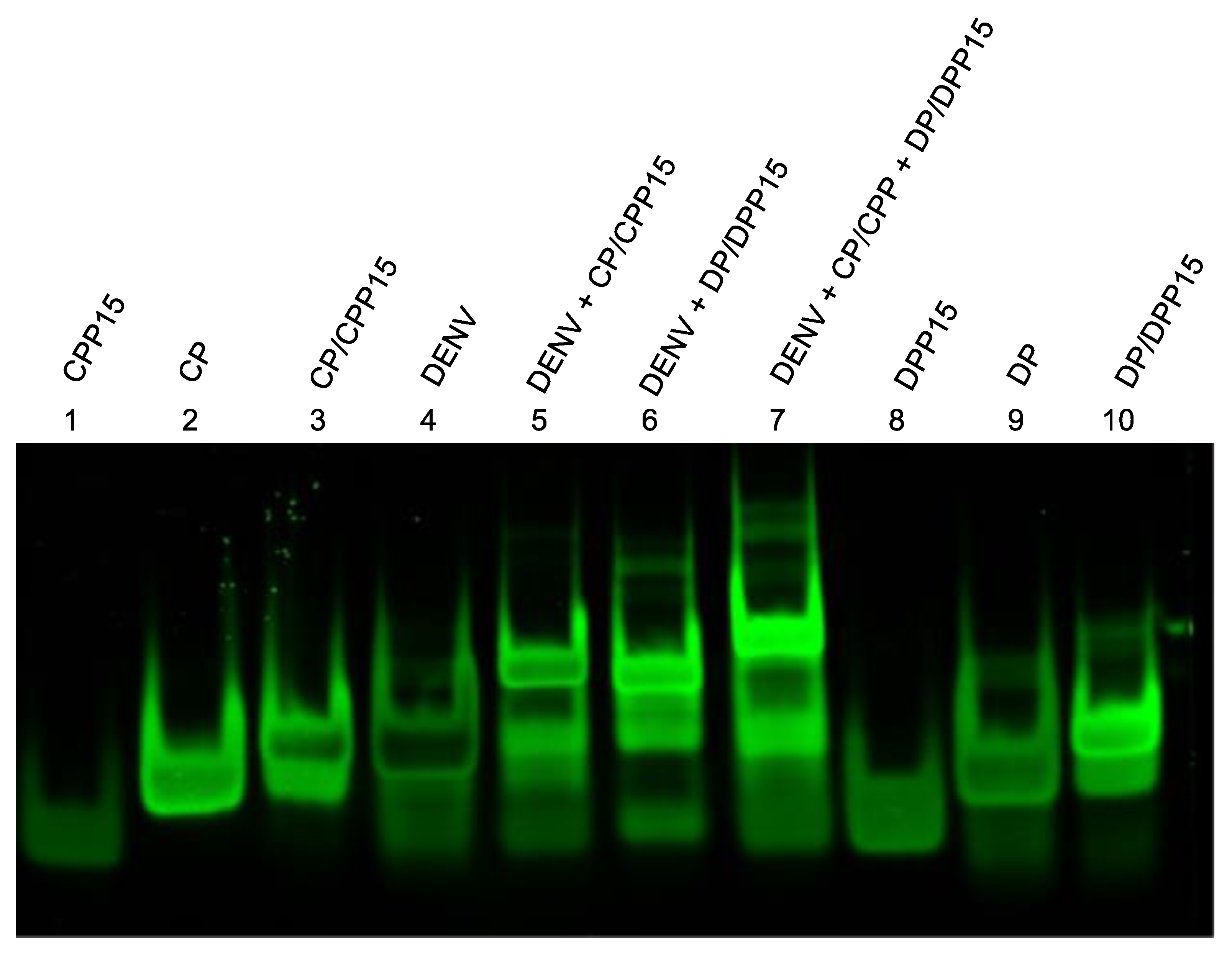

The successful implementation of the detection platform depends critically on the preparation of stable and functional DNA–Qdot conjugates. Thiolated DNA probes were conjugated to amine-functionalized Qdots using Sulfo-SMCC, a heterobifunctional crosslinker containing NHS ester and maleimide functional groups (

Figure 2). The NHS ester reacts selectively with surface amines on the Qdots, while the maleimide moiety subsequently reacts with thiol groups on the DNA probes, forming stable thioether linkages.

Following activation of NH₂-Qdots with Sulfo-SMCC and removal of excess crosslinker by gel filtration, increasing molar ratios of thiolated DNA were introduced to evaluate DNA loading efficiency. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to characterize the resulting conjugates. As the DNA-to-Qdot ratio increased, a progressive reduction in electrophoretic mobility was observed, consistent with the accumulation of negatively charged DNA on the nanoparticle surface. This mobility shift plateaued at DNA-to-Qdot ratios above approximately 30:1, indicating saturation of available binding sites on the Qdot surface.

These results suggest that, under the conditions employed, each Qdot can be functionalized with up to ~30 DNA molecules. This high degree of multivalency is advantageous for downstream hybridization reactions, as it increases the effective local concentration of DNA probes and enhances binding kinetics. Importantly, the conjugates remained colloidally stable and retained strong fluorescence emission following functionalization.

The functional integrity of the DNA–Qdot conjugates was assessed by evaluating their ability to participate in TMDR-based hybridization reactions. Equimolar mixtures of Qdot-DP/DPP and Qdot-AP were incubated together, and complex formation was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The appearance of higher–molecular weight species with reduced electrophoretic mobility confirmed sequence-specific hybridization between complementary probes (

Figure S1, Supporting Information). These results demonstrate that DNA conjugation does not compromise probe accessibility or hybridization capability.

3.3. Validation of Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Reactions

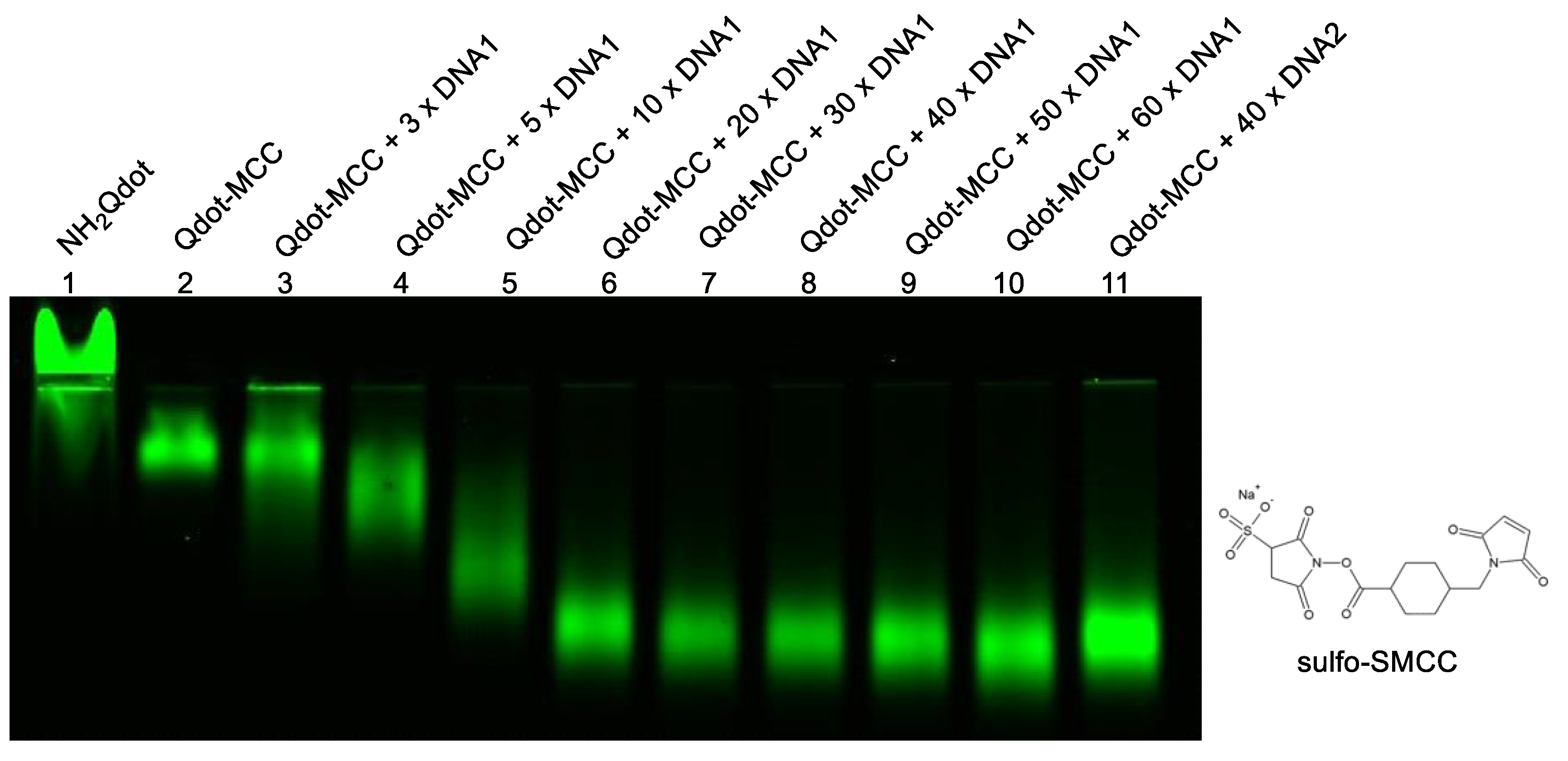

Efficient and rapid toehold-mediated strand displacement is a cornerstone of the detection strategy. To validate TMDR performance, strand displacement between the dengue virus–derived target sequence and its corresponding probe/protector duplexes was examined. Both the capture probe/protector probe (CP/CPP) and detection probe/protector probe (DP/DPP) systems were evaluated independently.

In the presence of the synthetic dengue DNA target, complete displacement of the protector strands was observed for both probe systems within 10 minutes at room temperature (

Figure 3). In contrast, no displacement occurred in the absence of the target, indicating high specificity and minimal background activation. These findings confirm that the probe designs enable fast and efficient TMDR under isothermal conditions without the need for enzymes or elevated temperatures.

The rapid kinetics observed here are particularly relevant for point-of-care applications, where assay time and simplicity are critical considerations. The ability to achieve complete strand displacement within minutes at ambient temperature highlights the practicality of the TMDR approach for decentralized diagnostic settings.

3.4. Sensitive Detection of DNA Targets

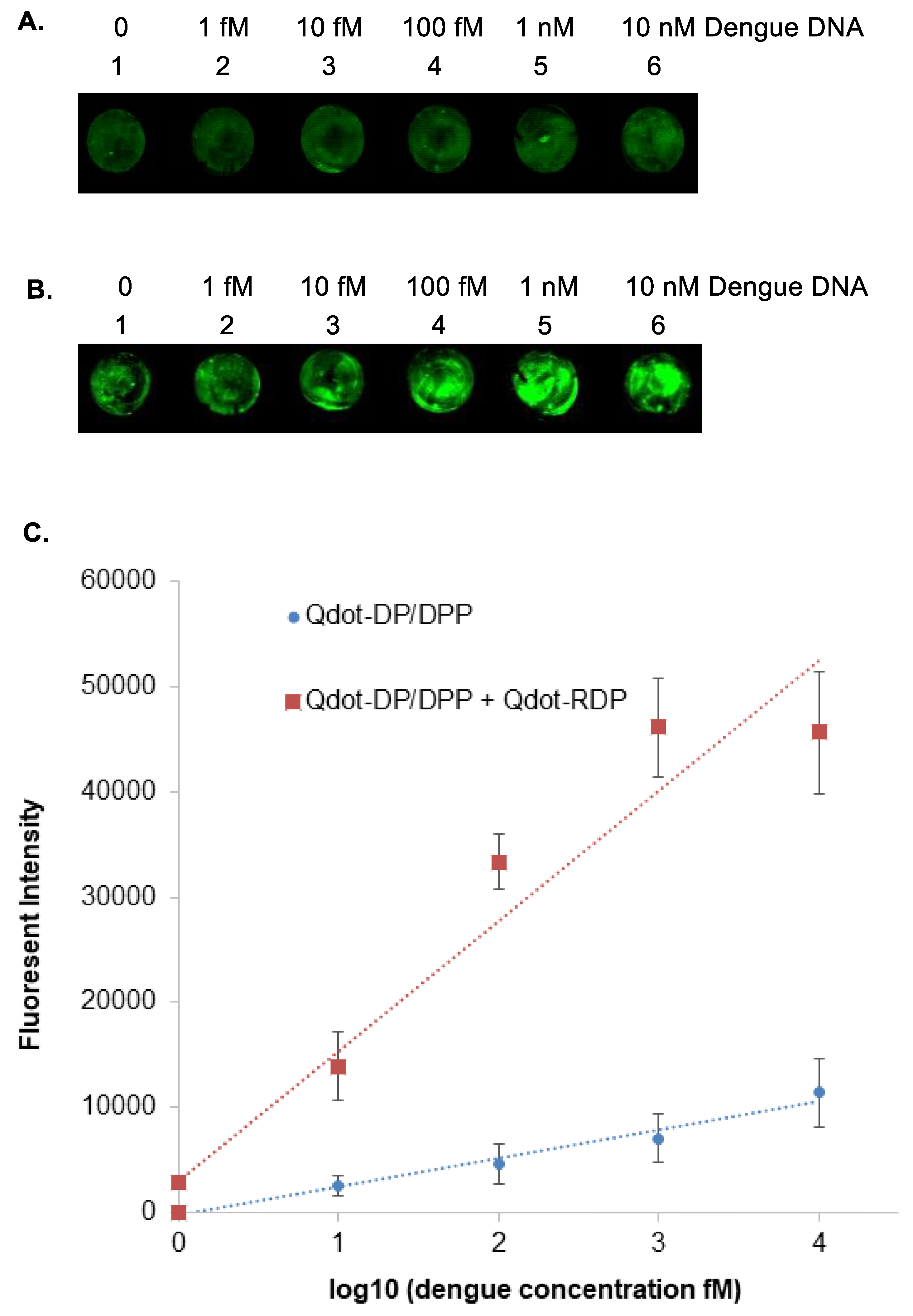

To establish the analytical sensitivity of the platform, serial dilutions of a synthetic dengue DNA sequence were tested. The DNA sequence corresponded to the conserved dengue target region and was selected for enhanced chemical stability relative to RNA. Concentrations ranging from 10 nM down to sub-femtomolar levels were applied to capture probe–modified glass slides.

Following incubation with Qdot-DP/DPP conjugates and washing to remove unbound probes, fluorescence imaging revealed clear signal detection at concentrations between 1 and 10 fM (

Figure 4A). Incorporation of the amplification step using Qdot-AP conjugates produced a marked increase in fluorescence intensity across all concentrations tested. With amplification, the limit of detection was improved to approximately 1 fM, corresponding to ~600 genome copies per microliter (

Figure 4B).

Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity demonstrated a concentration-dependent response over the tested range (

Figure 4C). The low background signal observed in negative controls further confirms the specificity of the assay. These results establish the platform’s ability to detect extremely low levels of nucleic acid targets without enzymatic amplification.

3.5. Preparation and Detection of Dengue RNA Targets

After validating DNA detection, the platform was extended to RNA targets to more closely mimic clinical dengue virus detection. A 45-nucleotide RNA corresponding to a conserved region of the dengue genome was synthesized in vitro using a T7 promoter–driven transcription system. Time-course analysis confirmed efficient RNA transcription (

Figure S2), and purification by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography yielded RNA of high purity and integrity (

Figure S3).

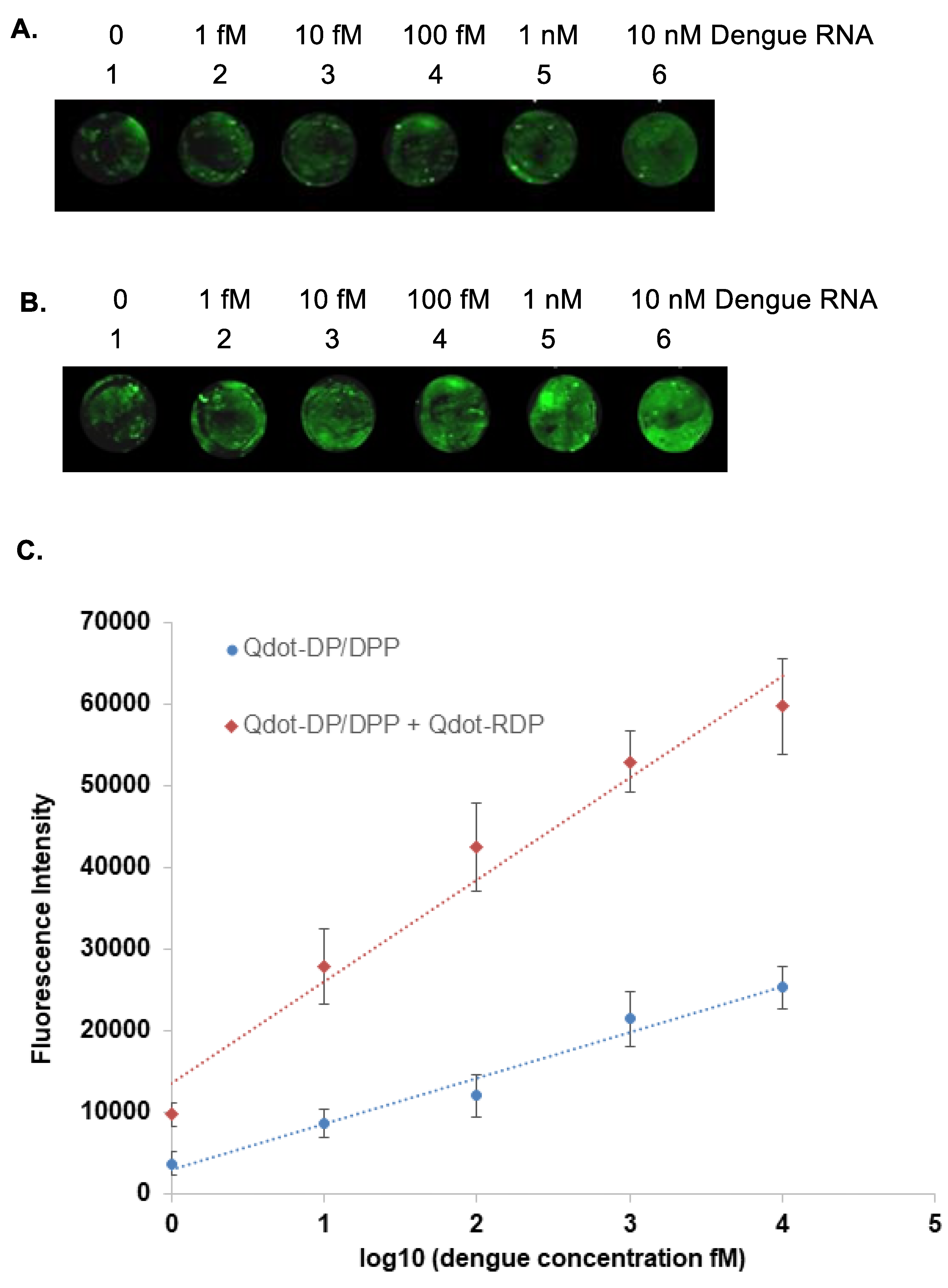

The purified dengue RNA was then evaluated using the Qdot-based detection platform. Similar to the DNA target, dengue RNA was efficiently captured on the glass slide surface through TMDR-mediated displacement of the capture probe protector strand. Subsequent binding of Qdot-DP/DPP conjugates generated a fluorescence signal that was readily detectable.

Importantly, femtomolar sensitivity was retained for RNA targets, with detection observed at concentrations as low as 1 fM (

Figure 5). The amplification probe–Qdot step again produced a substantial enhancement in fluorescence intensity, demonstrating the robustness and reproducibility of the amplification strategy across different nucleic acid types. These findings confirm that the platform is equally effective for DNA and RNA detection.

3.6. Detection of Dengue RNA in Contrived Clinical Samples

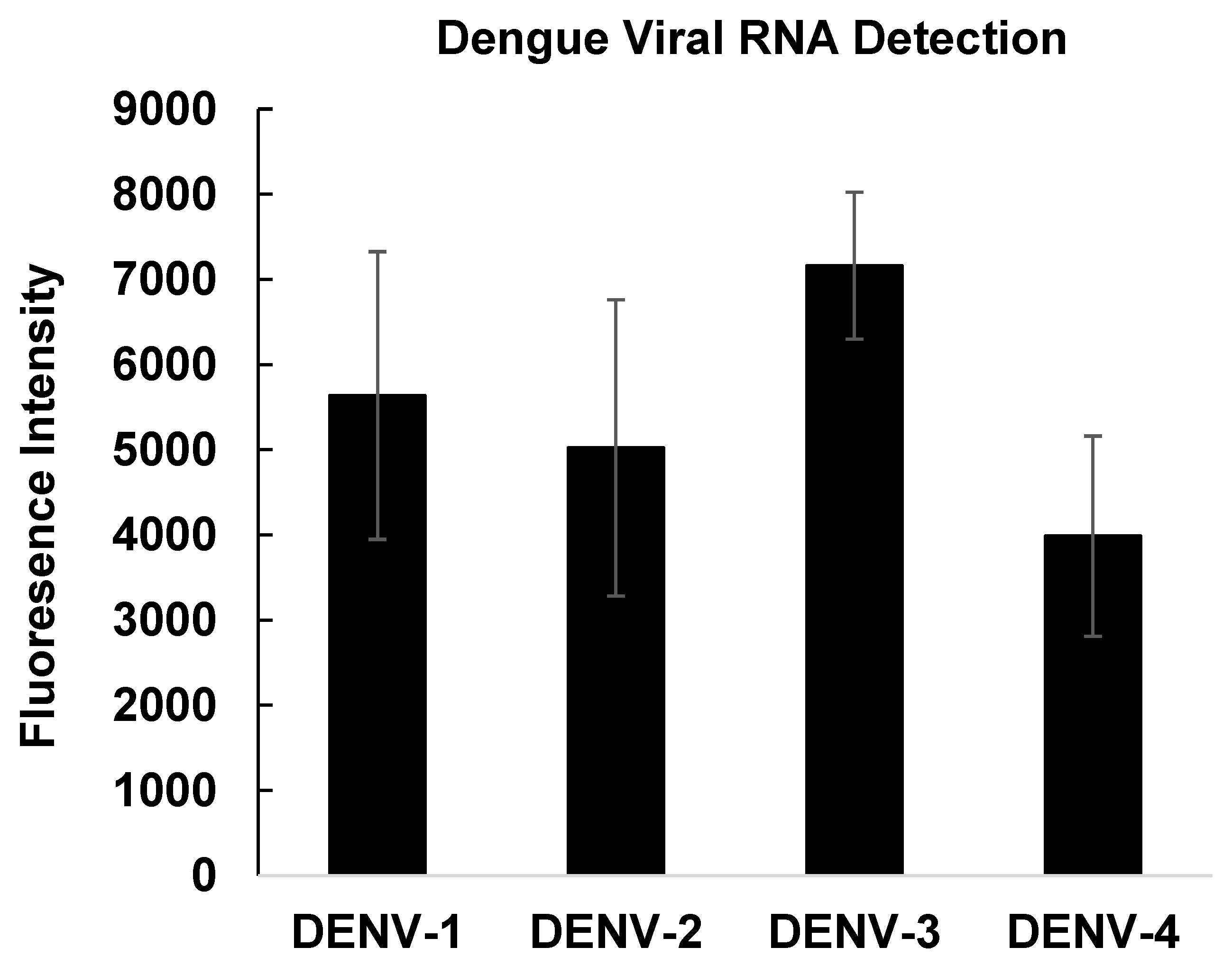

To assess applicability in biologically relevant matrices, the detection platform was tested using contrived clinical samples. Dengue virus–negative whole blood was spiked with culture supernatants from each of the four dengue virus serotypes to approximate viral loads observed during acute infection. Total nucleic acids were extracted using an instrument-free RNA extraction and stabilization protocol [

22]. The cycle threshold (Ct) for each serotype ranged from 25 to 30 using a validated, laboratory developed real-time RT-PCR [

23]. RNA was extracted at Emory University and stabilized for ambient temperature storage and shipment to Arizona State for testing. 10 ng of crude RNA from each sample was analyzed using the Qdot-DP/DPP detection step followed by Qdot-AP amplification.

All four contrived clinical samples produced strong and distinguishable fluorescence signals (

Figure 6), demonstrating that the assay is compatible with complex biological samples and capable of detecting dengue viral RNA without enzymatic amplification. Collectively, these results establish the feasibility of this Qdot-based, TMDR-driven platform as a sensitive and versatile approach for room-temperature detection of viral RNA.

4. Discussion

Early, sensitive, and accessible detection of viral RNA remains a fundamental challenge in the clinical management and public health control of dengue virus infection, particularly in low- and middle-income regions where laboratory infrastructure and trained personnel are limited. Dengue is endemic in many tropical and subtropical areas, where timely diagnosis is critical for patient triage, clinical decision-making, and outbreak control. However, the diagnostic tools most commonly used for early detection are often poorly suited to these settings. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which is widely regarded as the gold standard for viral RNA detection, relies on enzyme-mediated nucleic acid amplification, precise thermal cycling, and sophisticated instrumentation. These requirements increase assay cost, extend turnaround time, and necessitate stable electricity, cold-chain reagent storage, and highly trained operators, collectively restricting the use of RT-PCR to centralized laboratories [

4,

5,

6]. As a result, access to early and accurate dengue diagnosis remains limited in many regions where the disease burden is highest.

To address some of these challenges, alternative signal amplification strategies that avoid enzymatic reactions have been investigated. Chemical chain reaction–based approaches, including radical polymerization systems for biomolecular detection, have demonstrated the feasibility of enzyme-free signal amplification. However, many of these systems require relatively high target concentrations—often in the nanomolar range—to initiate and sustain a detectable signal, limiting their utility for early-stage viral detection when target RNA levels may be low [

24,

25]. Consequently, there remains a significant unmet need for molecular diagnostic platforms that combine high analytical sensitivity with operational simplicity and low resource requirements.

In response to this need, we developed a low-cost, rapid, and highly sensitive nucleic acid detection platform that operates at room temperature without enzymatic amplification. In this study, we present an enzyme-free, quantum dot (Qdot)–based nucleic acid detection strategy that achieves femtomolar sensitivity for dengue virus RNA targets under isothermal conditions. The sensitivity achieved by this platform corresponds to levels of dengue viremia that are typically observed during the first four to five days following symptom onset, a critical window for early diagnosis and clinical intervention [

26]. These results demonstrate that the combination of toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions (TMDRs) with modular Qdot-based signal generation and amplification offers a compelling alternative to conventional enzymatic amplification–based assays.

A central strength of the proposed platform lies in its use of TMDRs for sequence-specific nucleic acid recognition. TMDR is a well-established mechanism in which a single-stranded nucleic acid initiates strand displacement by binding to a complementary toehold region, triggering a predictable and programmable hybridization cascade. This process proceeds rapidly and efficiently under isothermal conditions and does not require enzymes or thermal cycling. In the context of the present assay, TMDR enables highly selective recognition of dengue virus RNA using rationally designed DNA probes that target a conserved viral sequence. The rapid strand displacement observed within minutes at ambient temperature highlights the practicality of this approach for point-of-care or near-patient testing, where speed and simplicity are essential [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Moreover, because the assay relies on short, sequence-specific DNA probes, it can be readily reconfigured to detect other RNA viruses by modifying probe sequences alone, without altering the overall assay architecture.

Quantum dots play a pivotal role in enhancing both the sensitivity and robustness of the detection platform. Compared with conventional organic fluorophores, Qdots offer several advantageous optical properties, including exceptional brightness, narrow emission spectra, high quantum yield, and remarkable resistance to photobleaching [

19,

20,

21]. These characteristics are particularly valuable in surface-based detection systems, where signal stability and intensity directly influence assay performance. In addition, the ability to conjugate approximately 30 DNA molecules to a single Qdot enables multivalent interactions between probes and target nucleic acids. This multivalency increases the effective local concentration of probes, improves hybridization efficiency, and amplifies the resulting fluorescence signal.

Importantly, the platform incorporates a hierarchical, enzyme-free signal amplification strategy that further enhances detection sensitivity. After initial target recognition and binding of Qdot-conjugated detection probes, additional amplification is achieved by introducing Qdot-conjugated amplification probes that bind to the detection probe–Qdot complex via a secondary TMDR. This step effectively increases the number of fluorescent reporters associated with each captured RNA molecule without introducing enzymatic complexity or additional reaction steps. The combined effects of Qdot brightness, multivalency, and TMDR-driven amplification contribute directly to the observed femtomolar detection limits.

The analytical sensitivity achieved with this platform compares favorably with many reported enzyme-free nucleic acid detection methods, as well as with chemical amplification–based approaches that typically require nanomolar target concentrations to generate a measurable signal. While RT-PCR remains the benchmark for sensitivity and quantitative accuracy, its operational complexity and cost present significant barriers to widespread use in decentralized settings. From a clinical perspective, the modest difference in analytical sensitivity between the Qdot-based assay and conventional real-time RT-PCR could be mitigated by expanding access to early testing. By enabling simple, rapid, and low-cost detection at the point of care, the platform described here has the potential to identify infections earlier in the disease course, when viral loads are still within the detectable range and clinical interventions are most effective.

The translational potential of this approach is further supported by its successful application to dengue genomic RNA extracted from complex biological matrices. Using a low-cost, instrument-free extraction and stabilization protocol, viral RNA was isolated from spiked whole blood and detected using the Qdot-based assay [

22,

23]. The ability to detect dengue RNA in crude extracts demonstrates compatibility with biologically relevant samples and indicates tolerance to background nucleic acids and potential inhibitors that often compromise assay performance. This capability is particularly noteworthy because the assay targets the 3′ region of the dengue genome, which is known to form stable secondary structures that can hinder hybridization-based detection. The successful detection of RNA from a field-ready extraction protocol that eliminates the need for instrumentation or ultra-cold storage underscores the suitability of this platform for use in clinics or austere environments where such infrastructure is unavailable.

Looking forward, integration of this detection strategy with microfluidic devices, paper-based platforms, or portable fluorescence readers could further enhance its usability in field and point-of-care settings. Such adaptations could enable sample-to-answer workflows and reduce user intervention, bringing the technology closer to real-world deployment. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. At present, the assay is primarily qualitative to semi-quantitative, relying on fluorescence intensity measurements rather than absolute quantification. Incorporation of internal standards, calibration curves, or ratiometric detection strategies may improve quantitative performance. Additionally, while contrived clinical samples provide an important proof of concept, comprehensive validation using authentic patient specimens will be essential to establish clinical sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. Finally, although Qdots offer excellent optical properties, considerations related to their long-term stability, manufacturing cost, and regulatory approval will need to be addressed as part of any large-scale diagnostic implementation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate a sensitive, modular, and enzyme-free platform for dengue virus RNA detection that integrates toehold-mediated strand displacement with quantum dot–based signal amplification. The assay operates at room temperature without enzymatic amplification or thermal cycling, addressing major cost and infrastructure barriers associated with conventional molecular diagnostics while retaining high analytical sensitivity. The modular probe design enables straightforward adaptation to other RNA targets. With continued optimization and validation using clinical specimens, this strategy has strong potential as a broadly applicable and accessible diagnostic framework for dengue virus and other RNA pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/xxxx, Figure S1: A toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction (TMDR) between Q-dot-DNA1 and Q-dot-DNA2, Figure S2: Time-dependent RNA synthesis of a 45-nt dengue RNA, Figure S3: Preparation of 45-nt dengue RNA and purified with DEAE-Sepharose column.

Author Contributions

Y.S., and N.A.: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. J.A.K: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. A.J., J.J.W., S.M.H. and S.C.: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Atlanta Center for Microsystems Engineered Point-of-Care Technologies (ACME-POCT), grant number A473111. The preparation of contrived dengue virus samples, extraction, storage and shipment was supported by the Georgia Research Alliance based in Atlanta, Georgia under award GRA.26.030.EU.02.b and Biolocity, a joint program of Georgia Tech and Emory University that accelerates early-stage medical technologies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DENV |

Dengue virus |

| EMCS |

Maleimidocaproyloxysuccinimide ester |

| Qdot |

Quantum dot |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction |

| TMDR |

Toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions |

References

- World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, S.B. Pathogenesis of dengue: Challenges to molecular biology. Science 1988, 239, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, P.Y.; Huang, J.H. Current advances in dengue diagnosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2004, 11, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, R.S.; Calisher, C.H.; Gubler, D.J.; Chang, G.J.; Vorndam, A.V. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples using reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J.D.; Wu, S.J.; Dion-Schultz, A.; et al. Development and evaluation of serotype- and group-specific fluorogenic reverse transcriptase PCR (TaqMan) assays for dengue virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Lee, E.M.; Putvatana, R.; et al. Detection of dengue viral RNA using a nucleic acid sequence-based amplification assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2794–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Emary, K.R.; Moore, C.E.; et al. Rapid diagnostic tests for dengue virus infection in febrile Cambodian children: Diagnostic accuracy and incorporation into diagnostic algorithms. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blacksell, S.D. Commercial dengue rapid diagnostic tests for point-of-care application: Recent evaluations and future needs. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 151967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yow, K.S.; Aik, J.; Tan, E.Y.; Ng, L.C.; Lai, Y.L. Rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of recent dengue infections: An evaluation of six kits on clinical specimens. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sufi Aiman Sabrina, R.; Muhammad Azami, N.A.; Yap, W.B. Dengue and flavivirus co-infections: Challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and disease management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeki, T.; Tajima, S.; Ando, N.; et al. Analysis of cross-reactivity among flaviviruses using sera of patients with dengue showed the importance of neutralization tests with paired serum samples for correct interpretation of serological test results for dengue. J. Infect. Chemother. 2023, 29, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Waggoner, J.J.; Hecht, S.M.; Chen, S. Selective detection of dengue virus serotypes using tandem toehold-mediated displacement reactions. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Daniel, D.; Zou, H.; Chen, S. Rapid detection of a dengue virus RNA sequence with single-molecule sensitivity using tandem toehold-mediated displacement reactions. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, F.C. Nucleic acid strand displacement—From DNA nanotechnology to translational regulation. RNA Biol. 2023, 20, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Xu, B.; Wu, J.; Xie, G. Series or parallel toehold-mediated strand displacement and its application in circular RNA detection and logic gates. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 241, 115677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walbrun, A.; Wang, T.; Matthies, M.; Šulc, P.; Simmel, F.C.; Rief, M. Single-molecule force spectroscopy of toehold-mediated strand displacement. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapadia, J.B.; Kharma, N.; Davis, A.N.; Kamel, N.; Perreault, J. Toehold-mediated strand displacement to measure released product from self-cleaving ribozymes. RNA 2022, 28, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.T.; Landon, P.B.; Lee, J.; et al. Highly specific SNP detection using 2D graphene electronics and DNA strand displacement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7088–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Guo, A.X.; Luo, T.; Cai, T.; Mirkin, C.A. Biomineralization of semiconductor quantum dots using DNA-functionalized protein nanoreactors. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Pons, T.; Lequeux, N.; Dubertret, B. Quantum dots–DNA bioconjugates: Synthesis to applications. Interface Focus 2016, 6, 20160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeneman, K.; Deschamps, J.R.; Buckhout-White, S.; et al. Quantum dot–DNA bioconjugates: Attachment chemistry strongly influences the resulting composite architecture. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 7253–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Cardozo, F.; Myers, D.R.; Rojas, A.; Waggoner, J.J. Simple and economical extraction of viral RNA and storage at ambient temperature. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0085922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waggoner, J.J.; Abeynayake, J.; Sahoo, M.K.; et al. Single-reaction, multiplex, real-time RT-PCR for the detection, quantitation, and serotyping of dengue viruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikes, H.D.; Hansen, R.R.; Johnson, L.M.; Jenison, R.; Birks, J.W.; Rowlen, K.L.; Bowman, C.N. Using polymeric materials to generate an amplified response to molecular recognition events. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; He, L. Polymeric macroinitiators for signal amplification in AGET ATRP-based DNA detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 150, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricou, V.; Minh, N.N.; Farrar, J.; Tran, H.T.; Simmons, C.P. Kinetics of viremia and NS1 antigenemia are shaped by immune status and virus serotype in adults with dengue. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |