1. Introduction

Digital amputations have increased in recent years, not only in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) but also in high-income settings [

1,

2,

3]. This rise reflects ongoing occupational hazards, road traffic accidents, domestic injuries, and recreational trauma. Beyond the immediate physical loss, digital amputation carries a profound psychosocial burden. Given the visibility of the hand in daily interpersonal interactions, even partial digital loss may lead to social withdrawal, altered self-image, and reduced quality of life [

4]. These effects are particularly pronounced in young and working-age individuals, for whom hand appearance and function are closely tied to personal identity and professional activity.

From a functional perspective, the hand represents one of the most complex and highly specialized units of the human body. Fine motor control, strength, precision grip, and tactile sensibility depend on the integrated interaction of bone, tendon, nerve, skin, and subcutaneous tissues. Even minimal tissue loss at the fingertip may result in disproportionate impairment, affecting dexterity, endurance, and object manipulation[

5]. As a result, reconstructive planning following digital amputation must be approached with particular care, balancing durability, sensibility, contour, and aesthetic integration, as we like to say “ tailor made reconstruction” [

6].

For these reasons, reconstruction should not be guided solely by functional considerations, but should also address aesthetic restoration, which plays a critical role in patient satisfaction, social reintegration, and long-term acceptance of the reconstructed digit.[

6] The volar pulp contributes more than half of the fingertip volume and plays a fundamental role in grip stability, proprioception, tactile discrimination, and shock absorption. Loss of this specialized soft tissue compromises not only mechanical performance but also sensory feedback, underscoring the importance of restoring adequate pulp bulk and compliance during reconstruction. [

7]

Over the past decades, a wide range of reconstructive techniques has been described for fingertip and complete digital defects, including local flaps, regional flaps, distant flaps, composite grafts, and microsurgical tissue transfer [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, no single approach is universally applicable, and the choice of technique must be tailored to defect size, location, mechanism of injury, and patient-specific factors. In this context, the principle of “like-with-like” reconstruction remains central. Owing to its anatomical, histological, and biomechanical similarities to the hand, the foot—particularly the toe pulp—represents an excellent donor site for digital reconstruction [

13,

14] . Toe-based free flaps reliably restore sensibility, durability, and contour, and have become a cornerstone in modern fingertip and digital reconstruction.

While considerable attention has been devoted to flap survival, sensibility, and nail complex reconstruction, comparatively little focus has been placed on the biological behavior of subcutaneous adipose tissue within these flaps. Traditionally, adipose tissue has been regarded as a passive filler, frequently trimmed, buried, or discarded to facilitate skin closure. In contrast, emerging evidence from regenerative medicine and reconstructive surgery has demonstrated that adipose tissue is a metabolically active organ, rich in adipose-derived stromal cells, vascular networks, and paracrine mediators capable of influencing angiogenesis, inflammation, and tissue remodeling. [

15,

16,

17]

In this study, we retrospectively analyze a large consecutive series of free toe-based digital reconstructions with specific attention to the healing behavior of preserved subcutaneous fat. We aim to explore the role of adipose tissue as a biological adjunct in fingertip reconstruction, hypothesizing that viable digital fat acts as an active scaffold supporting spontaneous healing, contour optimization, and stable reconstruction while facilitating early rehabilitation and minimizing donor-site morbidity.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of consecutive digital reconstructions performed using free toe-based flaps from 2019 until 2025. Inclusion criteria were patients older than 18 years old undergoing digital reconstruction with free toe tissue for traumatic or post-traumatic defects of the fingers. Patients with incomplete clinical records or insufficient postoperative follow-up were excluded.

Reconstruction was performed using several free toe flap variations, selected according to defect characteristics and reconstructive requirements. These included the pulp toe flap, chimeric pulp toe flap, trimmed great toe flap, and chimeric pulp plus trimmed great toe flap. Flap design and composition were tailored to defect size, location, and functional demands, with particular emphasis on restoring digital contour and sensibility. Detailed descriptions of the surgical techniques have been previously published and are therefore not reiterated in the present study(13,14,18).

A specific focus of this study was the management of subcutaneous adipose tissue. In all cases, healthy digital fat was intentionally preserved, incorporated and exposed with the aim of enhancing soft-tissue contour, supporting spontaneous healing, and minimizing the donor site morbility . Fat handling strategies were documented intraoperatively, including the extent of fat preservation and its relationship to final wound closure.

For each patient, we collected data on demographic characteristics, injury mechanism and pattern, defect location, flap type and design, and perioperative variables. Postoperative outcomes included complications, time to complete healing, need for secondary procedures, and subjective assessment of digital contour. Particular attention was given to the healing behavior of areas where subcutaneous fat was deliberately maintained or exposed. All patients were followed both clinically and photographically at regular intervals until complete wound healing was achieved. Serial photographic documentation was used to assess progressive epithelialization, contour evolution, and overall aesthetic outcome.

3. Results

A total of 126 patients underwent surgery for fingertip reconstruction utilized a free toe flaps and several variations, 113 males (89,7%) and 13 females ( 10,3%). Reconstruction was performed using toe-based free flaps, predominantly great toe pulp (GTP) flaps (71.4%), followed by trimmed great toe (TGT) flaps (14.3%), chimeric toe flaps (7.1%), and second toe–based reconstructions (4.0%). In all free flap reconstructions, adipose tissue harvested from the donor site was systematically preserved and used to tailor and contour the flap. To illustrate the versatility and technical nuances of flap utilization, three representative cases are presented, highlighting different reconstructive scenarios and applications of the technique.

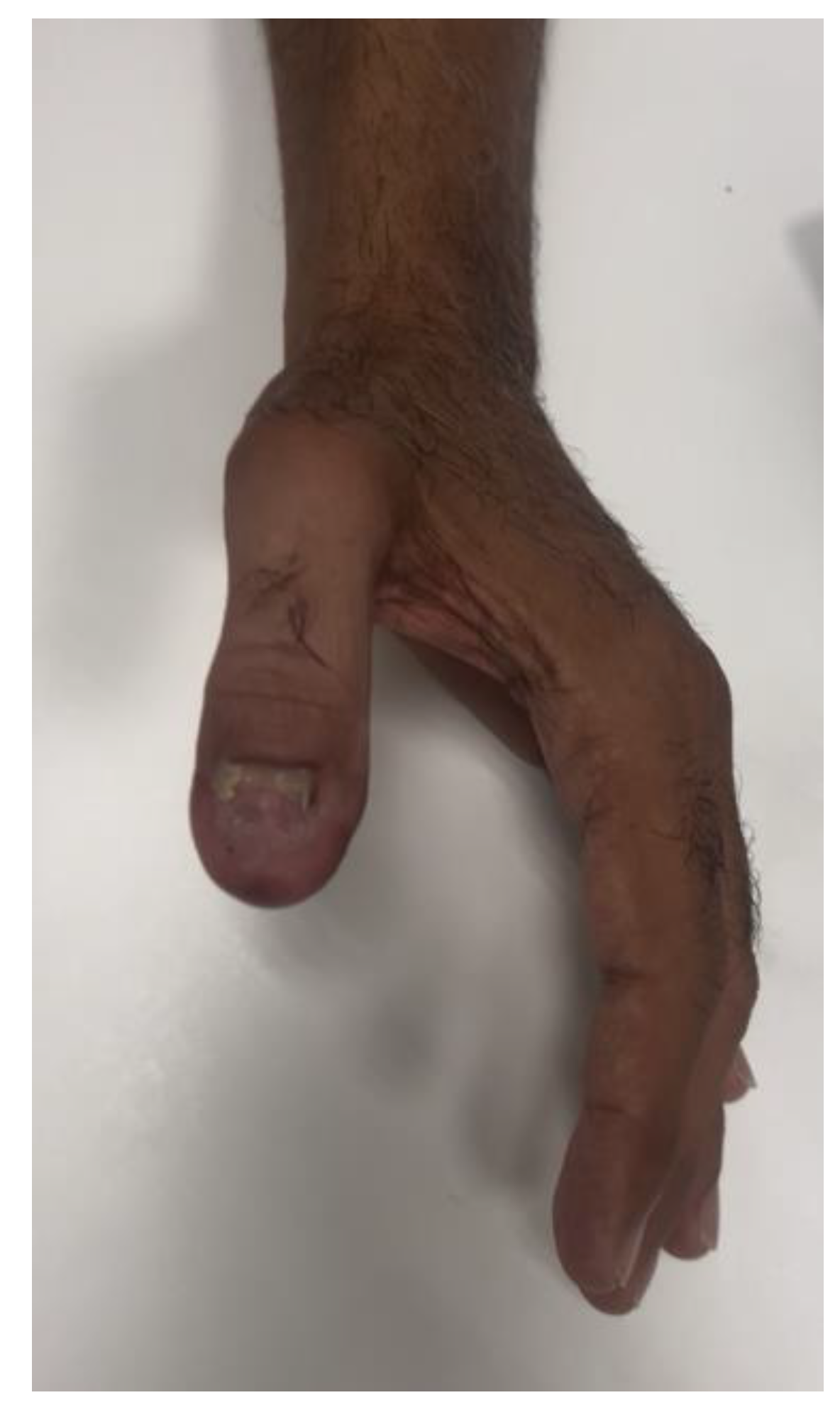

3.1. Case 1 – Use the Fat as a Nailbed

A 40-year-old male presented with a traumatic distal thumb tip amputation characterized by exposed bone and loss of the nail complex. Given the extent of soft-tissue loss and the functional importance of the thumb, reconstruction was planned using a free great toe pulp flap to restore both volar padding and dorsal contour while preserving sensibility. (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.)

The flap was harvested from the fibular aspect of the great toe and included a well-vascularized adipose component in addition to the pulp skin(

Figure 3). Particular care was taken to preserve the integrity of the subcutaneous fat during harvest, recognizing its potential role in contour restoration and secondary healing. During flap inset, the adipose tissue was intentionally positioned dorsally to recreate a compliant soft-tissue bed, serving not only to restore volume but also to function as a surrogate nailbed. The pulp component of the flap was oriented volarly to reconstruct the thumb pad(

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Postoperatively, the flap demonstrated uneventful healing with progressive integration of the adipose tissue into the dorsal aspect of the thumb. The patient was allowed to resume ambulation with the use of protective footwear, for the first 3 weeks and, then initiated hand and foot washing after, without compromising flap viability or donor-site healing.

At six weeks of follow-up, the reconstructed thumb exhibited near-complete integration of the flap, with stable soft-tissue coverage, satisfactory contour, and good tissue pliability. Nail advancement was observed after 3 month over the adipose-rich dorsal bed, and no secondary procedures were required. Both donor and recipient sites healed without complications (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

3.2. Case 2 – Using the Fat to Cover the Lateral Incisions

In all patients, arterial anastomoses were preferentially performed to the digital arteries whenever these vessels were available and demonstrated adequate inflow. Although digital arteries are frequently located close to the zone of injury and may present with small caliber or intimal damage, distal arterial anastomoses were favored when satisfactory flow was confirmed intraoperatively, in order to avoid unnecessary proximal dissection and additional surgical trauma.

During flap inset and skin closure, distal skin stiffness and limited tissue compliance occasionally precluded tension-free primary closure. In these situations, excessive closure tension was considered potentially hazardous, as it could compromise the vascular pedicle or exert pressure on the distal arterial anastomosis. Rather than forcing primary closure, the wound was intentionally left partially open and covered with a layer of well-vascularized pedicle adipose tissue. This adipose layer served as a protective biological cushion for the anastomoses while maintaining a viable wound bed.

Postoperatively, the exposed adipose tissue demonstrated predictable granulation and progressive epithelialization. Patients were allowed to initiate hand washing between three and four weeks after surgery without adverse effects on flap survival or wound healing. Complete secondary skin closure was typically achieved within six to seven weeks, resulting in stable soft-tissue coverage with satisfactory cosmetic outcomes. Notably, scars following secondary epithelialization over preserved adipose tissue were often minimal and clinically inconspicuous, and no vascular complications related to delayed closure were observed.

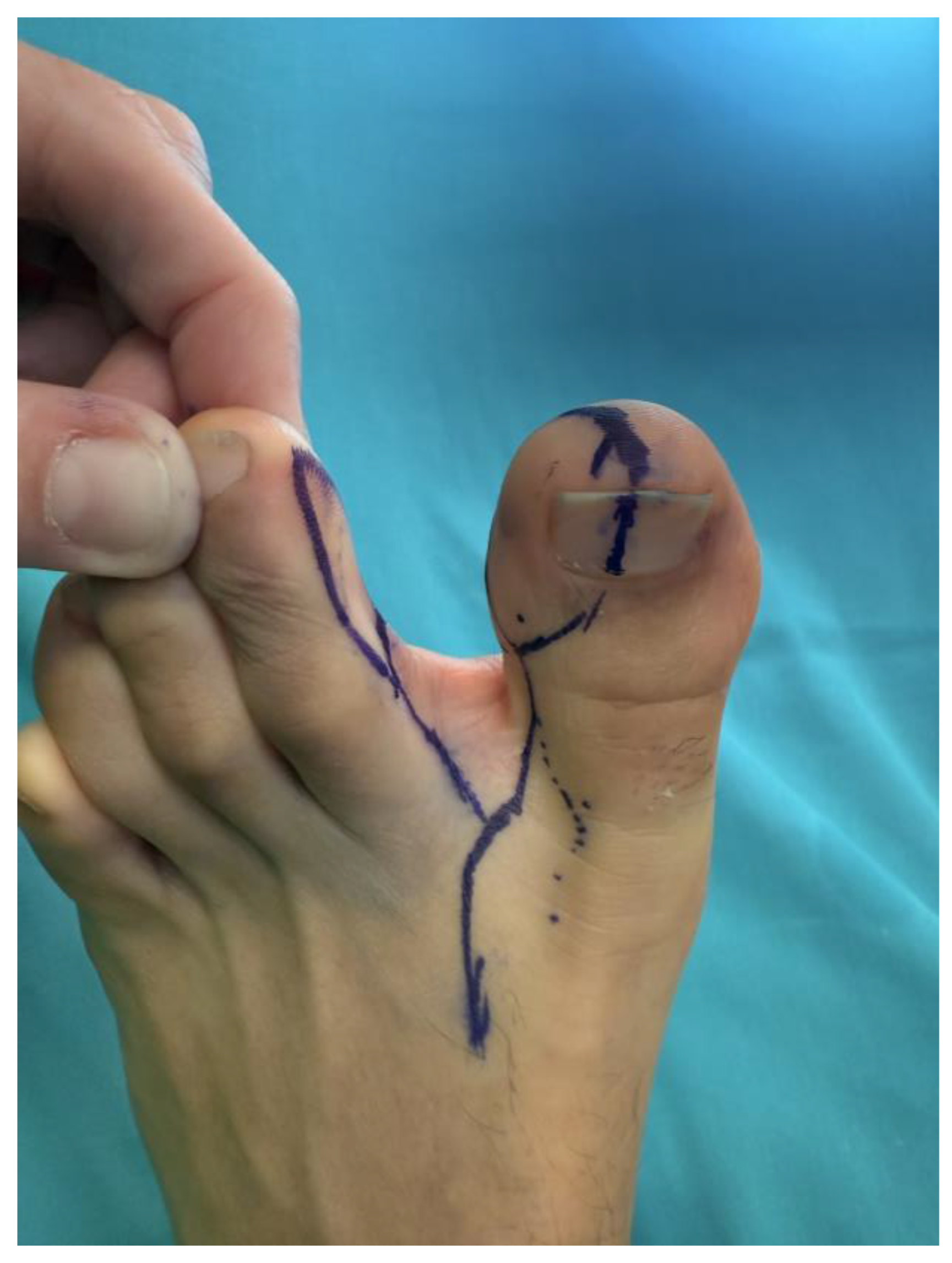

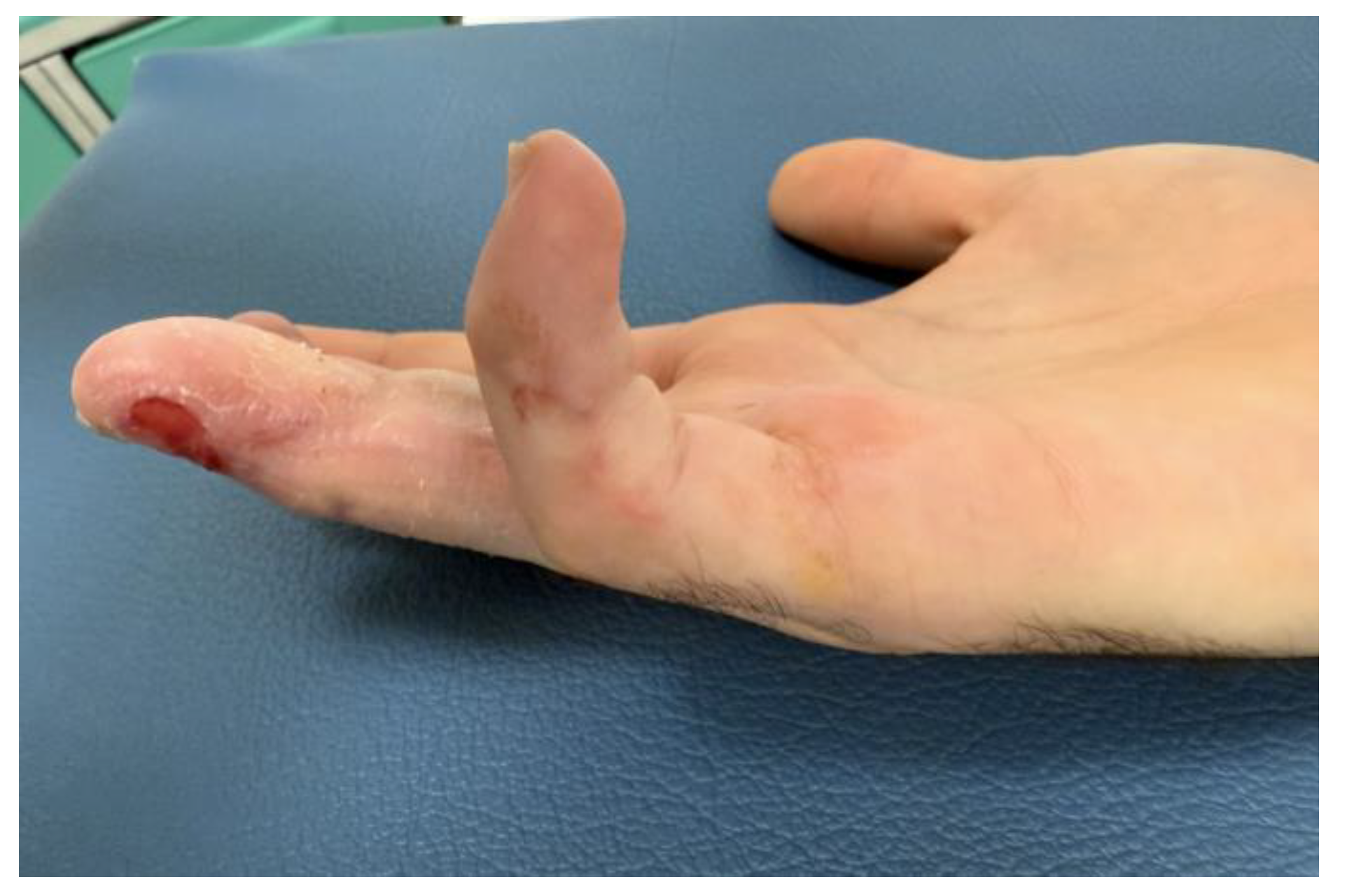

3.3. Case 3. – Using the Fat to Reconstruct an Hemi Trimmed Great Toe

An 18-year-old male sustained a severe crush-avulsion injury to the hand involving the middle, ring, and small fingers following trauma caused by an electric lawn mower. Emergency replantation of all three digits was initially attempted. While replantation of the ring finger was successful, replantation of the distal tip of the middle finger failed, resulting in exposed bone, and the small finger sustained complete loss of the distal phalanx with non-reconstructible soft-tissue damage (

Figure 8).

Given the extent and heterogeneity of the injuries, a staged reconstructive strategy was planned. Reconstruction of the small finger was performed using a trimmed great toe (TGT) flap, while a chimeric toe pulp flap was used to reconstruct the distal pulp defect of the middle finger. Particular attention was paid to donor-site preservation in order to minimize morbidity and maintain foot aesthetics and function.(

Figure 9 and

Figure 10)

To avoid complete nail harvest from the donor site and preserve as much of the great toe nail complex as possible, adipose tissue harvested from the fibular aspect of the trimmed great toe was intentionally preserved and mobilized (

Figure 11). This adipose component was rotated to reconstruct the volar pad of the small finger and sutured into the neo–nail fold, thereby restoring soft-tissue volume, contour, and padding while supporting the reconstructed nail complex. Owing to the absence of the distal phalanx and joint destruction, the small finger was stabilized with distal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis to provide a stable and functional digit.

Microvascular anastomoses were performed without difficulty, and flap perfusion was satisfactory. Postoperatively, the adipose tissue demonstrated stable integration without signs of necrosis or infection. The patient resumed ambulation at three weeks without the need for protective footwear. Due to the complexity of the injury and associated fractures of the middle phalanx of the small finger, rehabilitation of the remaining digits was initiated between three and four weeks postoperatively, while mobilization of the small finger began at six weeks.

At follow-up, both the reconstructed digits and the donor site demonstrated uneventful healing. Adequate padding and contour were achieved at the recipient site, while preservation of a significant portion of the great toe nail and volar pad resulted in minimal donor-site morbidity. No complications were observed at either the hand or foot level, illustrating the effectiveness of adipose tissue utilization in complex, multilevel digital reconstruction (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

4. Discussion

This study highlights the often-underappreciated role of preserved adipose tissue in free flap fingertip reconstruction. While toe-based free flaps are well established for restoring function, contour, and sensibility in digital defects, the biological behavior of viable subcutaneous fat—particularly when intentionally preserved or left partially uncovered—has received limited attention in reconstructive literature. Our findings suggest that adipose tissue should not be regarded merely as a passive filler, but rather as an active reconstructive component capable of supporting spontaneous healing, contour refinement, and stable soft-tissue reconstruction.

In this large retrospective series, deliberate preservation and strategic use of donor-site adipose tissue were consistently incorporated into flap design and inset. When primary skin closure was not feasible or would have generated excessive tension over the vascular pedicle, healthy adipose tissue was intentionally left exposed. In these cases, spontaneous epithelialization occurred within a predictable timeframe, with complete healing typically achieved within 6–7 weeks and without the need for skin grafting. Importantly, this approach did not increase complication rates at either the recipient or donor site, supporting its safety when flap perfusion is adequate.

These observations align with classical descriptions of secondary healing in fingertip injuries, in which preserved subcutaneous tissue plays a central role in wound contraction and epithelial migration. However, most existing literature on secondary healing focuses on conservative management of small fingertip injuries rather than microsurgical reconstruction. Our findings extend this principle to free flap reconstruction, suggesting that preserved adipose tissue within vascularized flaps can recreate a biological environment conducive to spontaneous healing even in complex reconstructions.

The biological plausibility of these findings is supported by growing evidence on the regenerative properties of adipose tissue. Adipose-derived stromal cells, together with the intrinsic vascular network of fat, are known to promote angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and epithelial migration[

15,

16,

17]. In the context of fingertip reconstruction, where soft-tissue quality, pliability, and volume are essential for both function and aesthetic, preserved fat appears to act as a biologic scaffold that facilitates secondary healing while maintaining three-dimensional contour[

19,

20].

Beyond its regenerative role, adipose tissue contributes mechanically to fingertip function. The digital pulp is a specialized fibrofatty structure organized by septa that anchor the skin to the underlying skeleton, allowing stability during pinch and grasp while dissipating load[

21]. Excessive removal of this tissue may compromise tactile discrimination and comfort. By preserving and strategically redistributing adipose tissue, the reconstructed digit may better approximate native biomechanical behavior.

The three representative cases illustrate the versatility of adipose tissue utilization across different reconstructive challenges. In Case 1, preserved adipose tissue was used not only to restore dorsal contour but also to recreate a functional nailbed, thereby supporting nail advancement following distal thumb amputation. Although demonstrated in the thumb, this concept can be extended to distal reconstructions of any finger. We believe that the presence of a compliant, well-vascularized soft-tissue bed facilitates nail growth, promotes smoother nail plate advancement, and may reduce the risk of nail deformities or secondary nail-related corrective procedures.

In Case 2, exposed pedicle adipose tissue provided effective protection of the distal vascular anastomoses in situations where primary skin closure would have risked excessive tension or pedicle compression. For this reason, our current practice is to avoid complete skin closure, beyond safeguarding the vascular pedicle, we observed that intentional preservation and exposure of adipose tissue facilitated secondary epithelialization, confirms, that after complete healing, the resulting scar was often barely perceptible. This suggests that leaving viable fat uncovered not only enhances vascular safety but may also contribute to improved aesthetic outcomes during secondary skin restoration

In Case 3, adipose tissue enabled partial reconstruction using a hemi–trimmed great toe flap, allowing preservation of a substantial portion of the toenail and volar pad at the donor site while providing adequate padding and contour in a complex multilevel digital injury. This case further illustrates how adipose tissue can be employed dynamically rather than passively, thereby expanding reconstructive options in challenging scenarios. An additional advantage of this approach is the reduction of donor-site morbidity. Preservation of portions of the toenail, minimization of skin graft requirements, and the possibility of early ambulation, typically initiated at three weeks postoperatively, collectively contribute to faster recovery and improved patient comfort. Donor-site morbidity has long been a concern in toe-based reconstruction, particularly in young and active patients. By limiting tissue harvest and leveraging preserved adipose tissue, our approach aligns with contemporary efforts to minimize functional and aesthetic impact on the foot [

22,

23].

Importantly, this strategy did not delay postoperative rehabilitation or the initiation of hand washing, both of which are often encouraged to facilitate physiological adaptation to the reconstructed digit and to support sensory re-education. Early sensory input and functional use are known to promote cortical reorganization and improve long-term sensibility following digital reconstruction. Allowing early hygiene and controlled use may therefore contribute not only to physical recovery but also to neural integration of the reconstructed digit. [

24,

25,

26]

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Its retrospective design and lack of a control group preclude direct comparison with alternative reconstructive strategies. Functional outcomes were assessed clinically rather than through validated patient-reported outcome measures, limiting quantitative evaluation of patient satisfaction and sensory quality. Additionally, while healing patterns were consistent, histological or molecular analysis of the healing process was beyond the scope of this study.

Despite these limitations, the strength of this study lies in the large number of patients, the consistency of surgical technique, and the reproducibility of healing outcomes across different flap types. The uniform observation of spontaneous epithelialization over preserved adipose tissue supports the concept that viable fat plays an active role in reconstruction rather than representing expendable tissue.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this series supports a conceptual shift in free flap fingertip reconstruction: preserved adipose tissue should be considered an active biological asset rather than tissue to be discarded or fully buried. Strategic use of donor-site fat may simplify reconstruction, reduce the need for secondary procedures, and enhance both aesthetic and functional outcomes. Recognizing adipose tissue as a regenerative adjunct, the “forgotten healer”, may refine reconstructive strategies and improve outcomes in digital reconstruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V, A.M., L.T..; methodology, M.V., A.M.; validation, L.T. and G.P.; data curation, L.T. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V..; writing—review and editing, M.V. and L.T; supervision, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures described in this manuscript were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. Formal approval from the institutional review board was not required. All patients included in the manuscript provided written consent for the publication of their images. The privacy rights of all human subjects were strictly observed.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to patient confidentiality but can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yuan, B; Hu, D; Gu, S; Xiao, S; Song, F. The global burden of traumatic amputation in 204 countries and territories. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1258853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, CS; Massenburg, BB; Morrison, SD; et al. Global trends of hand and wrist trauma: a systematic analysis of fracture and digit amputation using the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. Inj Prev. 2020, 26(Supp 1), i115–i124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbafati, C; Abbas, KM; Abbasi, M; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, SD. Psychosocial Issues after a Traumatic Hand Injury: Facilitating Adjustment. Published online. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Lo, S; Wei, FC. Toe Transfers Outperform Replantation after Digit Amputations: Outcomes of 126 Toe Transfers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025, 156, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcay, M; Pajardi, GE; Zanchetta, F; Stucchi, S; Baez, A; Troisi, L. Tailored Skin Flaps for Hand Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2022, 10, e4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, JA; Janis, JE; Rohrich, RJ. Soft-tissue injuries of the fingertip: methods of evaluation and treatment. An algorithmic approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008, 122(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongyue, Y; Yudong, G. Thumb reconstruction utilizing second toe transplantation by microvascular anastomosis: report of 78 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 92, 295–309.

- Cobbett, JR. Free Digital Transfer. Report of a Case of Transfer of a Great Toe to Replace an Amputated Thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br.

- Morrison, WA. Thumb and fingertip reconstruction by composite microvascular tissue from the toes. Hand Clin. 8, 537–550. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, WA. Thumb reconstruction: a review and philosophy of management. J Hand Surg Br. 17, 383–390. [CrossRef]

- Wei, FC. Tissue preservation in hand injury: the first step to toe-to-hand transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 102, 2497–2501. [CrossRef]

- Troisi, L; Stucchi, S; Vizcay, M; Zanchetta, F; Baez, A; Parjardi, EE. To Do or Not to Do? Neurorrhaphy in Great Toe Pulp Flap Fingertip Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022, 10, E4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, L; Mazzocconi, L; Mastroiacovo, A; et al. Beauty and Function: The Use of Trimmed Great Toe in Thumb and Finger Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022, 10, e4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendera, A; Kubis, H; Pałka, A; Banaś-Ząbczyk, A. Therapeutic and Clinical Potential of Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Secretome for Skin Regeneration. Cells. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) 2025, 14(21). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getova, VE; Orozco-García, E; Palmers, S; Krenning, G; Narvaez-Sanchez, R; Harmsen, MC. Extracellular Vesicles from Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells Stimulate Angiogenesis in a Scaffold-Dependent Fashion. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2024, 21, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brembilla, NC; El-Harane, S; Durual, S; Krause, KH; Preynat-Seauve, O. Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells Exposed to RGD Motifs Enter an Angiogenic Stage Regulating Endothelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, L; Hili, S; Mastroiacovo, A; Zanchetta, F; Vizcay, M; Pajardi, GE. The Free Chimeric Great Toe and Second Toe Pulp Flap for Reconstruction of Complex Digital Defects. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025, 13(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. J. Conservative Management of Finger Tip Injuries in Adults. Hand 1980, os-12, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, EM; Lalonde, DH. Secondary healing of fingertip amputations: a review. Hand. Springer Science and Business Media, LLC 2014, 9, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shores, JT. Anatomy and Physiology of the Fingertip. In Fingertip Injuries: Diagnosis, Management and Reconstruction; Rozmaryn, LM, Ed.; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodea, FV; Hariga, CS; Bordeanu-Diaconescu, EM; et al. Assessing Donor Site Morbidity and Impact on Quality of Life in Free Flap Microsurgery: An Overview. Life Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) 2025, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosin, M; Lin, CH; Steinberg, J; et al. Functional Donor Site Morbidity After Vascularized Toe Transfer Procedures: A Review of the Literature and Biomechanical Consideration for Surgical Site Selection. Ann Plast Surg. 2016, 76(6). Available online: https://journals.lww.com/annalsplasticsurgery/fulltext/2016/06000/functional_donor_site_morbidity_after_vascularized.25.aspx. [CrossRef]

- Rosén Birgitta, Balkeniu Christian, Lundborg Göran. Sensory Re-education Today and Tomorrow: A Review of Evolving Concepts. The British Journal of Hand Therapy 2003, 8, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Merzenich, MM; Jenkins, WM. Reorganization of Cortical Representations of the Hand Following Alterations of Skin Inputs Induced by Nerve Injury, Skin Island Transfers, and Experience. Journal of Hand Therapy 1993, 6, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosén, B; Lundborg, G. Training with a mirror in rehabilitation of the hand. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2005, 39, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).