0. Introduction

The conformal compactification of Minkowski space has long played a central role in both mathematical relativity and conformal field theory. In its standard realization, the compactified space is obtained as the projective null cone of a six-dimensional real vector space of signature

, and is often described, following Penrose, as the “Einstein universe” [

1]. Although this construction is classical and widely used, several geometric and conceptual aspects of the compactification and of its conformal infinity are still presented in a manner that can obscure their true structure. In particular, the topology of the compactified space, the role of the natural double cover, and the precise geometry of conformal infinity are sometimes treated in the literature in a way that leads to confusion or to oversimplified pictures, such as the ubiquitous but misleading “double cone at infinity”.

The first aim of this paper is to provide a detailed and explicit re-examination of the conformal compactification of Minkowski space within the framework of the null cone in

. The construction is carried out in a basis-independent manner whenever possible, with coordinates used only as a technical tool where they clarify the geometry. A central result is an explicit identification of the compactified Minkowski space

with the unitary group

by means of a diffeomorphism, which gives a clear matrix representation of points in the compactification. This identification goes back to work of Uhlmann [

2], who used the Cayley transform to relate hermitian

matrices to elements of

. Here, an explicit formula is derived that realizes this correspondence directly on the projective null cone and shows in detail how the Cayley transform fits into the general geometric picture.

A second main theme of the paper is the analysis of the full conformal group and its connected component acting on the compactified space. After recalling the standard embedding of Minkowski space into the null cone and the induced conformal structure on , several important Lie subgroups of are described explicitly in terms of their matrix representations. These include the Poincaré group, dilatations, conformal inversion, and special conformal transformations. Their action on and, in particular, on conformal infinity is analyzed in detail. It is shown that the action of on is transitive, but not effective, since the central element acts trivially on the projective null cone.

This observation leads naturally to the consideration of the double cover

of the compactified Minkowski space, obtained by quotienting the null cone by positive rescalings rather than by all nonzero real scalars. The resulting manifold can be identified with the Grassmannian of oriented null lines in

and is shown to be diffeomorphic to

. On

the action of

becomes effective, and two disjoint embeddings of Minkowski space are obtained, corresponding to two non-intersecting copies

and

. The remaining part,

, plays the role of a “doubled” conformal infinity. This point of view clarifies statements in the literature where

is directly identified with

(see, for example, [

1,

3]) and makes explicit the relationship between the simple compactification

and its double cover

.

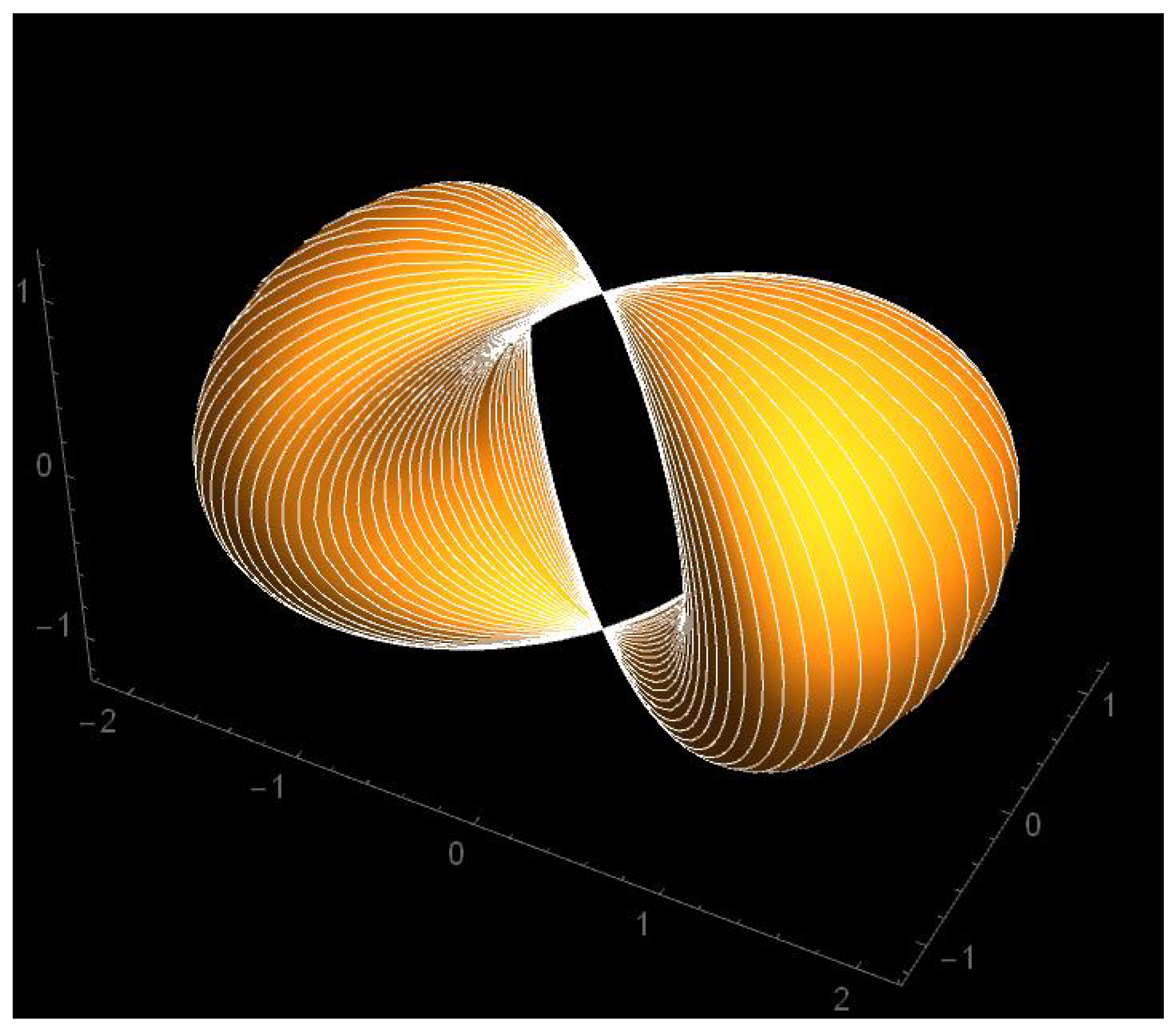

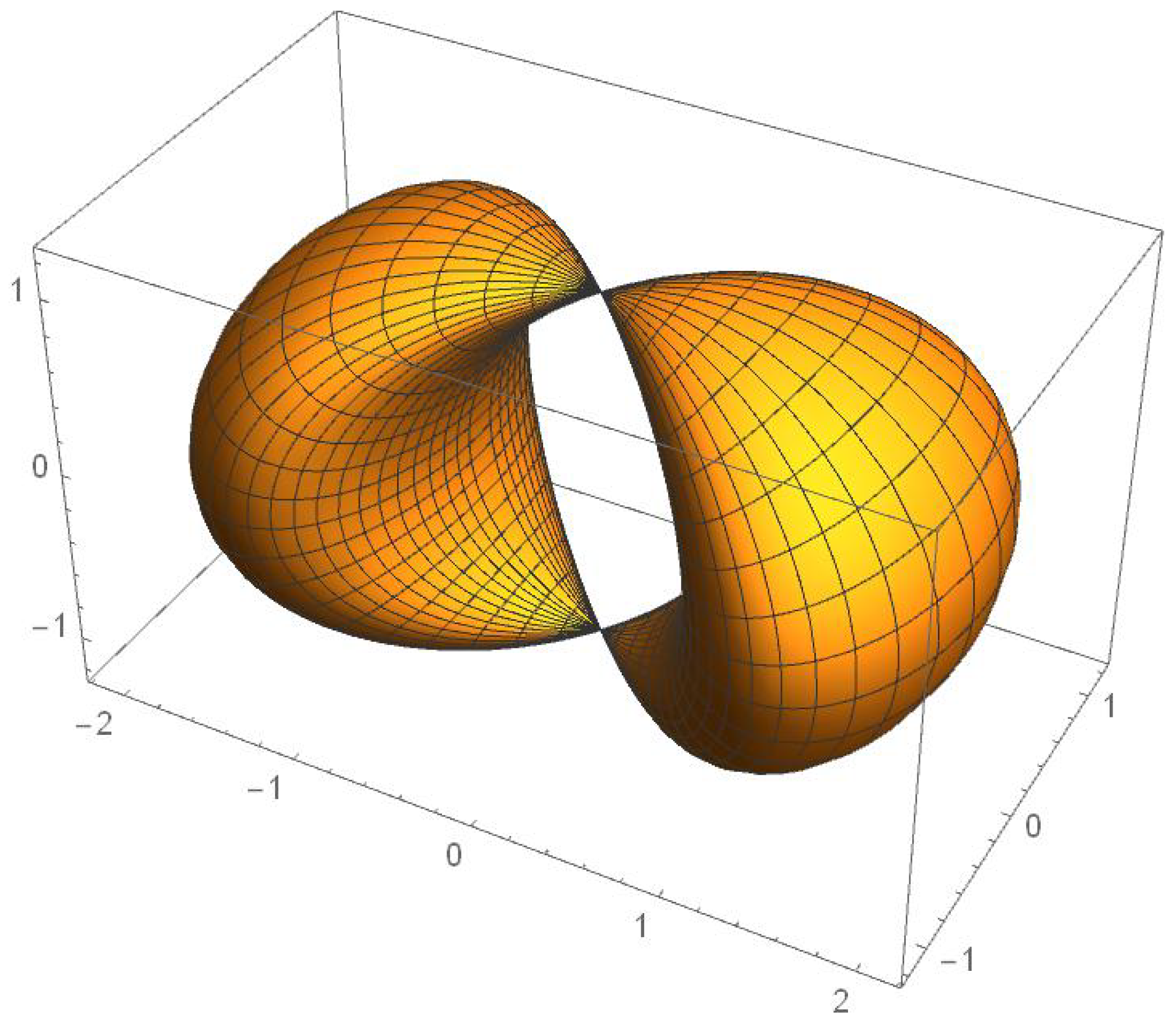

A substantial part of the paper is devoted to a precise geometric description of conformal infinity itself. Instead of the frequently drawn “double null cone”, the conformal boundary of the double cover,

, is shown to be a squeezed torus, namely a horn-type Dupin cyclide, while the conformal infinity

of the simple compactification is identified with a needle cyclide. These identifications are obtained by an explicit analysis of the intersection of appropriate quadrics in

, followed by a careful projection to three-dimensional Euclidean space. Parametric representations are derived and used to produce graphical illustrations of the resulting surfaces, which make the global structure of conformal infinity transparent and highlight, in particular, the presence of additional two-sphere components that are suppressed in the usual double-cone picture (cf. [

4,

5,

6]).

The final sections place these constructions into a broader geometric context. First, five-dimensional constant-curvature spaces are embedded so that their common boundary is the compactified Minkowski space, and the interpretation of geodesics in these ambient spaces is discussed. Second, the entire theory is reformulated in a coordinate-free language, following the approach of Kopczyński and Woronowicz [

7]. In this formulation the conformal compactification, its double cover, the conformal structure on the tangent bundle, and the null geodesics of the Einstein universe are described purely in terms of the quadratic form

Q on a six-dimensional vector space and its isotropic subspaces. This geometric reformulation not only clarifies the role of the tautological bundle and its orthogonal complement over the projective null cone, but also provides a natural setting in which to understand the conformal structure as an equivalence class of scalar products on tangent spaces and to see how null geodesics depend only on the conformal class of the metric.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 4 recalls the basic construction of the compactified Minkowski space as the projective null cone and introduces the identification with

as well as the embedding of Minkowski space by means of the map

and the Cayley transform. The conformal group

, its connected component

, and their important subgroups are then discussed, together with their action on

and on conformal infinity. The double cover

and its decomposition into two copies of Minkowski space and the doubled conformal infinity

are introduced and studied in detail, including the description of

as a horn cyclide and the corresponding structure of

. Subsequent sections address the embedding into five-dimensional constant-curvature spaces, the induced conformal structure and its relation to null geodesics, and finally the coordinate-free reformulation of the theory in terms of the projective null cone and its tautological and orthogonal bundles.

1. Definitions

We denote by

M the standard Minkowski space, that is

with coordinates

endowed with the quadratic form

Let

be

endowed with the quadratic form

defined by

We denote by

the 6–dimensional space

with coordinates

and endowed with the quadratic form

Let

be the null cone of

minus the origin:

and let

be the set of its generators, that is the set of straight lines through the origin in the directions nullifying

In other words

where, for

if and only if there exists a nonzero

such that

We denote by

the natural projection

Then with its projective topology, is a compact projective quadric. is called the compactified Minkowski space, denoted also by

A. Uhlmann [

2] used the Cayley transform to identify the compactified Minkowski space with the group

of complex unitary

matrices. The following proposition provides the identification of

with

in an explicit form.

Proposition 1.

For each the matrix

is unitary and depends only on the equivalence class of The map descends to a diffeomorphism from onto the unitary group

Proof. Let

. From the definition (

4) of

we have that

and

These two conditions are equivalent to

It follows, in particular, that

Therefore the right hand side of Eq. (

6) is well defined for all

, and is a smooth function of

A straightforward calculation gives us

where

is the

identity matrix. Taking into account the condition (

8) we deduce that, for

the matrix

is in

Notice that it follows from Eq. (

6) that for every

and

we have

therefore the function

is constant on the equivalence classes of the equivalence relation ∼ defining

and so it defines the map

from

to

We will now show that the map

is surjective.

Let

U be an arbitrary matrix in

. Since

it follows that

Let

c be one of the two (complex) square roots of

, so that

Since

we have

Then

is of determinant 1, i.e.

is in the group

, and we also have

Now, every element

of

can be uniquely written in the form

where

are complex numbers satisfying

which, by the way, gives us the well known topological identification of

with the sphere

. Defining

that is writing the complex numbers

as

one can verify that

, with

Therefore the map

from

to

is indeed surjective. Let us finally check the injectivity of the map

. Let

and

be in

, and suppose

We may assume that

and

as defined in (

8), are both equal to 1, otherwise one can rescale

X and

using property (

10) to make it so. In other words, we may assume:

Using simple algebra and taking into account Eqs. (

14) we find that the equality

leads to

which, together with

entails

From

it then immediately follows that

, therefore

□

2. Embedding of M into

Here we adapt the standard methods of Möbius geometry of Lie spheres, as discussed, for instance, in [

4] (Ch. 2, Eq. (2.6)). Consider the following smooth map between manifolds:

given by the formula:

The map

is evidently injective. Let

be the hyperplane in

defined by the formula

Lemma 1. The image of M in coincides with the intersection of the null cone with the hyperplane

Proof. It is clear that, for all

It also follows by a straightforward calculation that

thus

From Eq. (

17) we have that

is also in

Thus

is a subset of

To show that

let

be in

From

we get

But

so that, from

it follows that

Together with

it implies

or

and

It follows that

□

Remark 1. Eqs. (17) and (18) take a simpler form when, instead of orthogonal coordinates null coordinates are being used, as it is done e.g. in [6]. If we use these coordinates, and if we write X as then the quadratic form Q takes the form

We now define the embedding

by

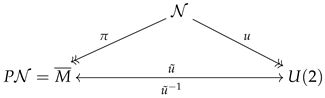

We thus have the following (commutative) diagram, where doubled arrow ends denote surjections.

2.1. The Conformal Infinity

Now, if and we can set . Then so that X and define the same point in But now It follows that the points of which are not in the image of M are equivalence classes of those for which These points define the conformal infinity. Another method of defining the same set is described in the next section

2.2. Embedding via the Cayley Transform

Denote by

the set of all complex hermitian

matrices.

is a real vector space of dimension

For

let

be defined as

Then is an isomorphism of real vector spaces M and

For every

let

denote the matrix

Then is in , and the map is injective. The map is called the Cayley transform. Composing we get an embedding of M into , but the following proposition shows that it is the same as

Proposition 2. The following diagram is commutative:

Proof. Since all the maps in the diagram are given explicitly, checking of the commutativity is a matter of a simple algebra. □

2.3. Conformal Infinity Within

Suppose we want to invert the Cayley transform

and express

A in terms of

We multiply both sides by

- it does not matter which side, since

A and

U commute. We get, after regrouping the terms:

We notice that we can express

A in terms of

U if and only if

is invertible (i.e. iff

U does not have 1 as one of its eigenvalues). The set of those matrices for which

is not in the image

We denote this set by

and call it the

conformal infinity. This is not a one-point compactification. We add to

a whole (closed) “cap” - a three -dimensional manifold

Remark 2. is not exactly a smooth manifold. As we will see it has a singular point, a `corner’. Usually it is referred in the literature as `the double cone at infinity’, but it is not a double cone at all (Cf. [5]). It is a Dupin cyclide - Cf. (Section 6.5).

3. Action of the Conformal Group

Let

G be the diagonal matrix

so that for

we have

The group

is defined as the group of all real

matrices

L satisfying

It is evident that, for every if X is in , i.e. if and , then also is in Moreover, L maps equivalence classes of ∼ into equivalence classes, therefore the action of on descends to its action on We define as the subgroup of consisting of matrices of determinant

3.1. The Group

In order to separate four space-time coordinates from additional two coordinates we have chosen the signature of

Q as

In this subsection it will be convenient to choose the signature

the two signatures being equivalent by permutation of coordinates. Formally it can be achieved by switching the coordinates

and

, that is by a similarity transformation

,

where

R is the matrix

Notice that

and that

is equivalent to

Now it is convenient to write

in a block matrix form, using matrices

of respective dimensions

:

Then the condition

translates to:

where we denoted by 1 the identity matrices of appropriate dimensions. In particular we have

which entails

and

Therefore either

or

Similarly, either

or

It can be shown (Cf. Refs. [

8,

9]) that, for

,

if and only if

We define

Then (Cf. [

10] p. 107)

is a connected subgroup (the connected component of identity) of

Proposition 3. The action of on the compactified Minkowski space is transitive.

Proof. Let and be any two points in Let us choose the representatives of the equivalence classes so that That means and The group acts transitively on the sphere therefore we can choose an orthogonal rotation from acting on the variables , and leaving the variables fixed, that transforms into Similarly the group acts transitively on the sphere therefore we can choose an orthogonal rotation from acting on the variables , and leaving the variables fixed, that transforms into The composition of these two transformations is in and maps X to □

Remark 3. Notice that the transformation is in and acts on as the identity map. Thus the action of on is not an effective action.

4. The Double Cover of

For

we define the equivalence relation

as

Definition 1. We will denote by the canonical projection

We denote by

the equivalence classes of this relation. Notice that while

we have

In fact each equivalence class of ∼ contains two equivalence classes of ≈. The projective space

is known as the Grassmannian of null lines in

We define

i.e. as the Grassmannian of

oriented null lines in

Proposition 4. is diffeomorphic to

Proof. Each equivalence class has now a unique representative X with Namely, if is arbitrary, then is this representative. Now, if , we define , , and then and . Conversely, any such pair of defines with □

Remark 4. Penrose and Rindler, in their classic monograph [1] (p. 298-299) state (Eq. (9.2.1)) that (denoted there ) is homeomorphic to For a non-expert reader this can be somewhat confusing. As we have seen can be identified with , which is a double cover of In Ref. [3] is denoted and called “the Einstein space”.

The action of

on

is defined the same way as for

We define

Proposition 5. The action of on is transitive.

Proof. The proof goes exactly the same way as for □

5. Important Subgroups of

In Eq. (

17) we have defined the embedding

of

M into

We will use this map to identify important Lie subgroups of

(and discrete transformations in

)

5.1. Translation Subgroup

We start with translations where

We have

where

is the scalar product of vectors in

and

Thus

or

But we want the transformation to be linear in

X. The trick is to multiply the right hand side by

We get this way the desired formula:

The transformation

is now implemented by the following matrix written in a block matrix form:

where

or explicitly:

One can easily check (for instance using a computer algebra software) that

and that

5.2. Lorentz Rotations Subgroup

For any Lorentz rotation

we have

therefore the way the Lorentz rotations are embedded in

(using our definition of

G) is evident. We simply set, using block matrix form,

5.3. Dilation Subgroup

This time we choose a different way. There is a natural subgroup of

similar to the Lorentz rotations case, but putting a "Lorentz rotation" in the lower right corner. This one-parameter Abelian subgroup is defined as follows:

where

Proposition 6.

For we have

Therefore the matrices implement dilations of the Minkowski space.

Proof. For

we have

where

Let

. Then

where

Now

Using also the definitions of

and

we obtain

□

5.4. The Conformal Inversion

Conformal inversion is defined in

M as the map

We assume that x is dimensionless, otherwise we would have to define it as where R is some "radius". Also notice that on M the transformation is singular on the null cone at the origin Under conformal inversion the null cone is mapped into a set of points at the conformal infinity of How? It will be clear after we derive the matrix representation of the conformal inversion, which we will do right now.

Assuming

and with

consider the following simple calculation:

But the end result is the same as acting on

with the following matrix

from the group

:

and then multiplying the resulting vector by

which is inessential when projecting on

using the projection

In other words conformal inversion is implemented on

by the reflection in the variable

Notice that

so

is in

but not in

Finally let us address the question of the image of the null cone at the origin by the conformal inversion. It follows from Eq. (

53) that this image is the `double null cone at infinity’:

But that is not yet the whole conformal infinity. What remains is the set

which is homeomorphic to the sphere

It is this sphere that connects the lower and upper branches of the null cone at infinity, and makes the conformal infinity into a compact set - Cf.

Figure 2. Many published papers on the subject omit this two-sphere and incorrectly identify the conformal infinity with the `double null cone’, as e.g. in [

6] (p. 263).

5.5. Special Conformal Transformations

This four-parameter Abelian subgroup of

is defined as:

The matrices representing

are similar to those representing

since the bracketing of any matrix

A with

results only in changing signs of the elements

in the fifth row and

in the fifth column, the element

changes sign twice, so it stays unaltered. Thus we have:

It is easy to get the action of the special conformal transformations on

From the definition we have

which simplifies to

Evidently, for a given the points x for which are transformed onto points in the conformal infinity.

5.6. Conformal Structure

Let

p be a point in

, and let

be a vector tangent to

at

A vector tangent at

p to

is a vector tangent to a smooth curve

such that

We will write it as

We will use now one of the intuitively clear important properties of projective manifolds, such as . Namely, given any there always exists a smooth curve defined for s in a neighborhood of , such that and We say that is a (local) lift of through X.

Of course such a lift is not unique. If

is any smooth function such that

then, locally,

is another lift of

through

In fact any two lifts of

through

X are related that way.

Now, in coordinates,

is described as a function

with

It is convenient to use the notation

for the scalar product

in

Since

is a null vector, we have

Taking the derivative with respect to

s at

we find that

In other words is perpendicular to

Let now

be any two tangent vectors at

and let

be two curves through

p such that

Let

and

be the coordinate expressions of lifts of

and

through the same

We define the scalar product of tangent vectors by the formula

For this definition to make sense we must show that the scalar product defined in this way does not depend on the choice of lifts through

To this end suppose

are two other lifts. Differentiating with respect to

s at

we get

Now, taking into account the fact that

and

we immediately find that

therefore the scalar product

is indeed well defined. It is now immediate that for any

,

, we have

Therefore what is defined at p is not a scalar product, but an equivalence class of scalar products, where two scalar products are considered to be equivalent if they are proportional, with a proportionality constant that is strictly positive.

We say that we have defined this way a conformal structure on To give a Riemannian (or pseudo-Riemannian) structure on a manifold is to specify a scalar product at each tangent space. When only a class of proportional scalar products is defined, we call it a conformal structure.

5.7. Calculating the Conformal Structure of Explicitly

The map

defined in Eq. (

17) defines a coordinate system on an open dense subset of

. We will now derive the expression of the

invariant conformal structure in the domain of this coordinate chart. Let

p be a point in this domain, and let

be the point in the Minkowski space

for which

So

p is represented by

Of course

p can be represented as well by

but let us concentrate on

In coordinates a tangent vector at

x has coordinates

. Let

be a curve through

In coordinates it is represented by a curve

Then

defined by

is a lift of

to

Differentiating the last equation with respect to

s at

and taking into account the explicit form of

we obtain

Let us calculate an explicit formula for

. With

from Eq. (

71) we easily get

the other two terms cancel each other.

In other words: the invariant conformal structure on in a local chart of Minkowski space coordinates consists of scalar products proportional to the standard Minkowski space scalar product.

6. The Case of the Double Covering Compactification

Here we will find out what needs to be changed and how if we replace the simple compactification with its double cover

6.1. The Action of Becomes Effective

If G is a group acting on a set we say that the action is effective (resp. free) if, for and for all (resp. for some) implies that g is the identity element of In other words the action is effective if every different from the identity element of G does something nontrivial to something (to some element of M), and free if every different from the identity element of G does something nontrivial to everything (to every point of M). Thus every free action is effective, but there exist actions which are effective but not free.

Consider the matrix

, which is in

It acts on every

replacing it with

. But

X and

are in the same equivalence class of ∼ so

- they define the same point of

. The matrix

does nothing to all points of

- the action of the group

on

is not effective - we are losing information. But, for

X and

define two different points of

Therefore

acts nontrivially on

In fact, we have an effective action of

on

1

6.2. The two Embeddings .

Eq. (

17) defines the embedding of

M into

:

Replacing

x by

and taking into account the fact that

we obtain another embedding, we call it

:

while the first embedding we call

Remark 5. We could as well define It would also work. Which definition will prove to be more convenient will be seen only after a physical interpretation will be given to these constructions. As it is above the transformation implements space and time inversion on M.

6.3. The Doubled Conformal Infinity

and are two nonintersecting copies of M embedded in Their union forms an open dense set in

Let us define

where

is as in the Definition 1,

Section 4. Then

is a sum of three disjoint sets

We have two copies of M: and , and the doubled conformal infinity

The matrix

is in

and it maps

into

and equivalence classes of ≈ into equivalence classes. Therefore it defines a unique mapping

such that:

We evidently have

Remark 6. The action of ι on is free. Or more precisely: the action of the two-element group on is free. The two-element group is isomorphic to the group - the additive group of integers modulo 2. It acts freely on can be identified with the quotient

We will now analyze the structure of

and, after skipping one space dimension, provide its graphical representation. To this end consider the two equations defining

written as

Clearly the number

is positive, it cannot be zero because that would imply

and the origin is excluded. Therefore we can always choose a unique positive scaling factor and get two equations in

and

These are two intersecting cylinders. The infinity plane

cuts this intersection effectively reducing the number of dimensions to 3. We obtain:

Notice that

therefore

Thus the whole surface in

is contained within a ball of radius

In order to arrive at a graphics representation in

we suppress one space dimension, say

so that two-spheres will be represented by circles. We are left now with four variables

and the intersection of two cylinders:

6.4. Conceptual Structure of

Let us start with considering the variable

that plays a special role - it appears in both equations (

90) and (

91). It can vary in the closed interval

Consider first the two endpoints of this interval. If

it follows from Eqs. (

90),(

91) that the remaining variables cannot vary at all, they must all have value

These will be two special “endpoints” of

Assume now that

In that case

satisfy the equation

This equation describes a circle of radius The radius of this circle first grows from 0 to 1 when varies from to 0, then the radius gets smaller and smaller when varies from 0 to It becomes a point when For each value of , the variable takes one of the two possible values

The circles (in the plane ) corresponding to positive and those corresponding to negative are disjoint, as and are always two different points in .

It follows from the above discussion that we can safely conjecture that we do not really need four dimensions spanned by The whole should have a faithful representation of (with one space dimension skipped) in We will now prove that this is indeed the case.

6.5. Graphical Representation of .

We will provide a particular implementation, using mathematical formulas, the intuition provided by the reasoning above. It is a simple matter to see that we have the following:

Proposition 7.

Let a be a real number For any satisfying Eqs. (90),(91) let be defined as

Then the mapping

is injective.

To obtain a parametrization of this two-dimensional surface embedded in

we first parametrize, using the parameter

, the circle given by Eq. (

91):

From Eq. (

90) we then have

This is a circle of radius

We will use parameter

for this circle. Thus we can set

But it is convenient to reshuffle the sub-ranges of the parameters, and get rid of the absolute value setting simply

Eqs. (

93)-(95) now become:

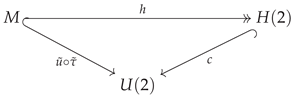

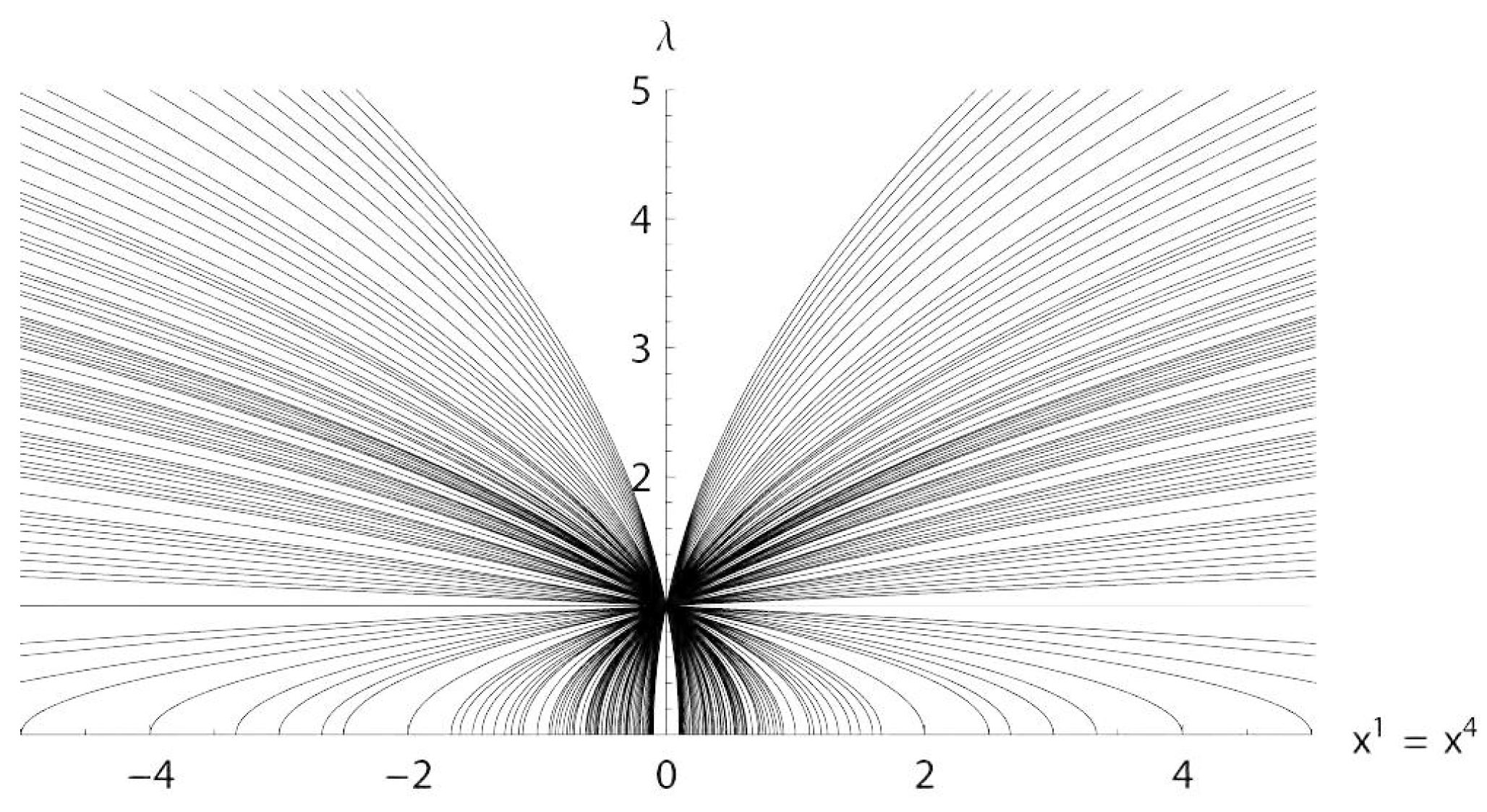

The resulting parametric surface is represented in the following picture:

Essentially, what we have here is a torus, that has been squeezed to a point at two opposite ends.

6.6. Action of the Poincaré Group and Dilations on Conformal Infinity

With the notation as in Sec. , the infinity is characterized by the condition

therefore

If

then

and we get two possibilities

, and

These are the two endpoints in

Figure 1. One can easily check that each of these two endpoints is stable under the action of translations, Lorentz transformations and dilatations. Let us remove these two points from our considerations. Assuming now that

we can chose a unique representative point of the corresponding open subset of

with

We then denote by

u the real parameter

and set

Then every point of the surface is uniquely represented in the form:

where

We obtain an infinite cylinder

If we set

, we get

, , with

Lorentz rotations, translations and dilatations are acting on the conformal infinity leaving this cylinder invariant as a set. We will now calculate the corresponding actions and vector fields corresponding to one-parameter subgroups.

6.6.1. Translations

Eq. (

45) gives us the action of translations subgroup. At the infinity

Skipping the third space coordinate, translation by

is realized by

In order to satisfy Eqs. (

90),(

91) we have to take the quotient by

. Therefore we get the following nonlinear translation transformation:

Taking partial derivatives of

with respect to

at

we get vector fields

– generators of translations:

where

These vector fields are tangent to the infinity surface defined by Eqs. (

90),(

91) and can be expressed in terms of basic vector fields

on this surface. One can easily check that the following formulas hold:

6.6.2. Lorentz Transformations

Let us first consider a pure space rotation:

while

The normalization in this case is unnecessary and differentiating with respect to

at

we obtain the vector field

of pure space rotations:

Next let us consider Lorentz boosts in the direction of the

axis:

while

This time we have to normalize as in Eq. (

108). We get

Differentiating with respect to

at

and using the fact that

, we obtain the vector field

:

Using Eqs. (

99),(100),(

96),(97) we can provide its expression in term of basic vector fields

as follows:

Using the same method we obtain the expression for the generator

D of the dilatations:

A straightforward calculation leads to the Poincaré group (extended by dilatations) commutation relations

6.7. Simple Conformal Infinity

By taking the quotient by ∼ rather than by ≈ we arrive at the same equations (

88,

89), but this time

x and

describe the same point.

Jakob Steiner has faced a similar problem when studying the method of representing the projective plane in

One possible solution was to use quadratic expressions in the coordinates - Cf [

12] and [

13]. Let us first follow a similar method. In order to represent the resulting variety graphically, we will need the following lemma:

Lemma 2.

With the notation as in Section 6.5 introduce the following variables:

Then, assuming that satisfy (90),(91), we have if and only if either or

Proof. The variables

y being quadratic in

it is clear that the ’if’ part holds. Now suppose we have

If

then

therefore from (

91) we have that

and

It follows then from (

90) that

and the same for

Therefore

and

thus

If

then

and

□

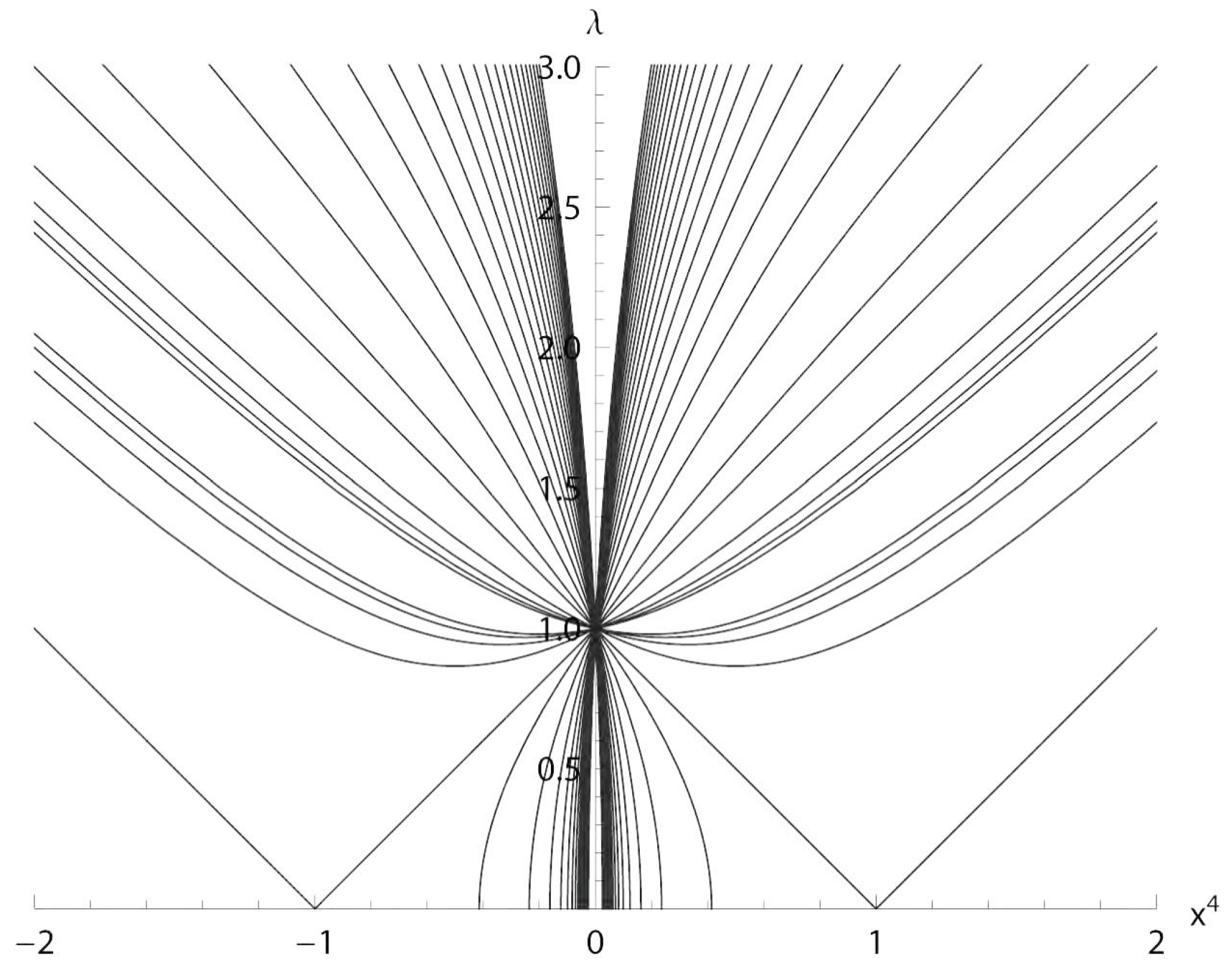

6.8. Graphic Representation of Simple Infinity

To obtain a graphic representation we proceed as before and arrive, after renaming of the variables, at the following set of parametric equations

The resulting surface has the shape of a simple elliptic supercyclide

needle (horn) cyclide as in Fig.

Figure 6 - [

14] (Fig. 6, p. 80) [

4 (Fig. 5.7, p. 156), or, in French,

croissant simple [

15]. The surface is, in fact, made of closed null geodesics, all intersecting at the point with homogeneous coordinates

Each od these geodesics is uniquely determined by a point on the 2-sphere

The geodesic is then given by the formula

Figure 2.

Pictorial representation of the simple conformal infinity with one dimension skipped - needle cyclide, made of a one parameter family of null geodesics trapped at infinity.

Figure 2.

Pictorial representation of the simple conformal infinity with one dimension skipped - needle cyclide, made of a one parameter family of null geodesics trapped at infinity.

6.9. Conformal Structure of

Let us begin with a simplified case, with a suppressed

coordinate. As it was described above, in

Section 6.5, we will use the

parametrization. We have the following equations parametrizing

:

Using this parametrization,

we calculate

Since on

we have

, the last two terms cancel, so effectively

Assuming

we easily get

Therefore the metric on our two-dimensional squeezed torus has the form

At the two squeezed points we have and the metric becomes totally degenerate. For other values of u we have a scaled ( by , standard metric on the circles: The metric along the u-lines, connecting the two end-points, is identically zero. Notice that the metric itself is defined up to a scale, since X and , , describe the same point in So, in fact, we have a conformal structure, not a metric.

Let us now return to the full case, including the

coordinate. The calculations become somewhat more complicated, but the end result is similar. Now instead of the coordinate

v we introduce spherical coordinates

and set

Calculating

we get

which is also degenerate:

The part of the metric is the standard metric on the unit sphere in

7. Geometrizing It All - Getting Rid of the Basis

In this section we will make use of the constructions in a paper [

7] by W. Kopczyński and L.S. Woronowicz. They have built a really beautiful and solid foundation. Whenever there is a need, we will adapt their methods to our purposes (for instance in [

7] the authors did not consider the double cover). We will use coordinates only when it is convenient to use them in order to prove some properties. Thus we are allowed to use a basis inside the proof, but not in definitions and in statements about the properties of objects and morphisms. Our reasonings will thus be more abstract, but it will be easier to grasp their geometrical meaning.

In a sense we will repeat all what has been done so far, rephrase it, but now, in definitions and in statements, applying only geometrical invariant concepts.

Let V be a six-dimensional real vector space endowed with a quadratic form of signature Let be the unique scalar product on V such that for all For we will write for

Let

be the null cone of

Q with removed origin:

For

we define the equivalence relation ≈ as

We denote by the equivalence class of X with respect to ≈, and denote by the natural projection.

From now on we define

as

We denote by the group of linear isometries of , i.e. the group of all linear operators for which for all We denote by its subgroup of isometries of determinant one. Notice that for all implies for all Also notice that the determinant of the matrix of a linear transformation does not depend on a choice of a basis.

Proposition 8. The group acts on transitively.

Proof. The proof has been done choosing an orthonormal basis for □

For

and

we will write

We will denote by

the transformation

It is then immediate that the two-element subgroup isomorphic to acts freely on

If p and q are two points in then the property does not depend of the choice of and This fact justifies the following definition:

Definition 2.

For we will write if For any we define as

It is then evident that for

we have

We will call the conformal infinity at p.

Exercise 1. (Why

the conformal infinity at p) Choose an orthonormal basis in V thus identifying V with Choose and Find the explicit form of Identify the points p and on Figure 1.

Exercise 2.

Suppose we want to define the operation of addition on by defining

Can we do this?

Definition 3.

Given any we define

Definition 4.

For let

Exercise 3. Show that the sets are open in (this require some knowledge of topology).

Exercise 4.

where the dot in denotes the fact that we are dealing with a union of disjoint sets.

7.1. Conformal Structure on the Tangent Bundle

The

Section 5.6 can be repeated here without any changes. We did not use coordinates there at all. However we will now discuss in some detail the tangent bundle

of

that is the (disjoint) union of all tangent spaces

As a manifold, is eight-dimensional.

7.1.1. The Tautological Bundle

Every projective manifold comes with a gratis bundle - the tautological bundle. In our case we have the bundle

with one-dimensional fibers

where, for

Thus over each point we have one-dimensional fiber - the subspace spanned by X. Notice that the zero vector of V is in each of these fibers, nevertheless the fibers over different points are disjoint, because, strictly speaking, these "zeros" are ordered pairs and if

Now, since

V is equipped with a scalar product, we also have the orthogonal bundle

where, for

, we have

The fibers of

are five-dimensional. Notice that since

we have

Therefore we can take the quotient bundle whose fibers are the quotient spaces

Using the reasoning in

Section 7.1 about the conformal structure it is clear that the tangent bundle

can be naturally identified with the quotient bundle

Let us choose any such that

Exercise 6. Show that such a q always exists.

Definition 5.

With we define as follows

Remark 7. Notice that is four-dimensional and that, in this definition, Z is assumed to be only in V, not necessarily in . In fact no such Z exists in Proving this is another good exercise.

It is clear from the definition that is a vector space. We can even easily argue that it is four-dimensional - we have two linear conditions on a vector in a six-dimensional space.

We will now construct a vector space isomorphism between and

Proposition 9.

With the notation as above the following map is a vector space isomorphism

where denotes the equivalence class defining the quotient of vector spaces

Proof. Since

Z is in

we certainly have

therefore

Z is in

Let us first see that

is injective. For this it is enough to show that if

then

Now, from the very definition of the quotient of vector spaces it follows that

means that

for some real

If

, then

which contradicts the assumption that

Z is in

Therefore

and so

To prove that

is “onto" it would be enough to bring out the fact that both the domain and the range are vector spaces of the same dimension - four. But it is easy to show it explicitly. To this end, let

be an arbitrary element of the quotient space, with

Now

is not necessarily in

since

is not necessarily zero. Let

Define

Then

and

Therefore Z is in □

Now, since we have already identified the quotient with the tangent space we have a vector space isomorphism between and - different one for different choices of

Let us now recall that, for we have defined as with removed - we remove the infinity cap at If then consists of all those for which Then splits into a disjoint union of and according to whether is positive or negative. Let us concentrate now on the positive case. Then we can always choose Y so that We can therefore construct We will now construct an embedding, which we will denote , of the vector space into the projective null cone manifold such that the image is exactly It is similar to a stereographic map when we embed the plane - the tangent plane at the South Pole p into the sphere, so that the image of this tangent plane is the sphere with removed the North Pole q - the "infinity".

Proposition 10.

Choose a point - an `origin of infinity’. Choose another point and let be its representative in such that The point will be the “origin of the visible `+’ universe". Define

by the following formula:

Then is injective, and its image is exactly

Similarly, if we chose for instance we can set , and define

we obtain an onto diffeomorhism

Before stating the proof we first note that the mapping

is non-linear. It should not be a surprise, since we are wrapping a linear 4-dimensional space

around a compact space

diffeomorphic to

Then we need to show that

is indeed in

that is that

Instead of doing just this, let us contemplate

of a more general form

and find the condition on

so that

is a null vector. Using the facts that

and

we instantly obtain

Therefore is a null vector if and only if

Next, it will be handy to use the following lemma:

Lemma 3.

Let us choose an arbitrary orthonormal basis in thus identifying V with There exists a transformation such that

Proof. Since

acts on

transitively, we can always find a group element that transforms

into

where

After this transformation

will have the form

with

and

To transform further

into

we will use transformations form

that do not affect the point

These are translations, dilatations and 3D rotations. We will use a translation, rotations and dilatations will not be needed. From Eq. (

41) it is clear that translating by

we assure that

takes the form

But then we still have the two conditions:

and

They give us two equations:

and

with a unique solution

□

We will now use this lemma to prove Proposition 8.

Proof. (of Proposition 10) Using Lemma 3 without any lose of generality we may assume that

and

But then our

is the same as

in

Section 6.2, which we already know that it is an embedding. □

7.2. Another Take on Conformal Structure - Null Geodesics

We have identified defined in the Definition 5, with the tangent space Now is a vector subspace of therefore it inherits for V a scalar product. This induces a scalar product on It can be shown that this scalar product is compatible with the conformal structure already defined on - it is a good exercise. With a fixed p but different q these scalar products must thus be proportional (another exercise).

Null geodesics in General Relativity

In this paragraph let

M be a four-dimensional manifold of general relativity. In local coordinates

let

be the metric tensor of signature

Metric tensor induces the Levi-Civita connection

Levi-Civita connection defines covariant derivative

For vector fields we have

A curve

is called a geodesic (or autoparallel) if the tangent vector

parallelly transported along the curve remains tangent to it. This condition entails the equation:

where, for a vector field

denotes the covariant derivative along the path:

One can then always choose a parameter

in such a way that

The geodesic equations become then

Such a parameter is then-called an affine parameter for the geodesic.

Let us see how the geodesic equations (

180) change when we replace

by another metric

in the same conformal class? A straightforward calculation results in

where

If

is an affine parameter for the geodesics of the metric

the equation of geodesics for the new metric become

or, using Eq. (

182):

Assume now that we dealing with a null geodesic, that is that the tangent vector is always a null vector, so that

The last term in (

185) vanishes. Setting

(

185) takes the form of Eq.(

178). Therefore we have the following result

Proposition 11. While in general geodesics for two conformally equivalent metrics are different, null geodesics are the same. They depend only on the conformal structure and not on a particular choice of the representative of this structure.

7.2.1. Coordinate Free Description of Null Geodesics in

is a compact manifold diffeomorphic to

It cannot be covered with one coordinate patch. When we describe null geodesics by geodesic equations, we usee coordinates. Suppose we find a particular solution, a path given in a coordinate system. Then the question arises: and what happens next? How this particular path is going to continue after the coordinates patch ends? In our case one can give an elegant answer to this question by providing a coordinate-free description of a null geodesic, the whole of it, without invoking differential equations. We follow here, [

7], modifying the proof to suit our needs.

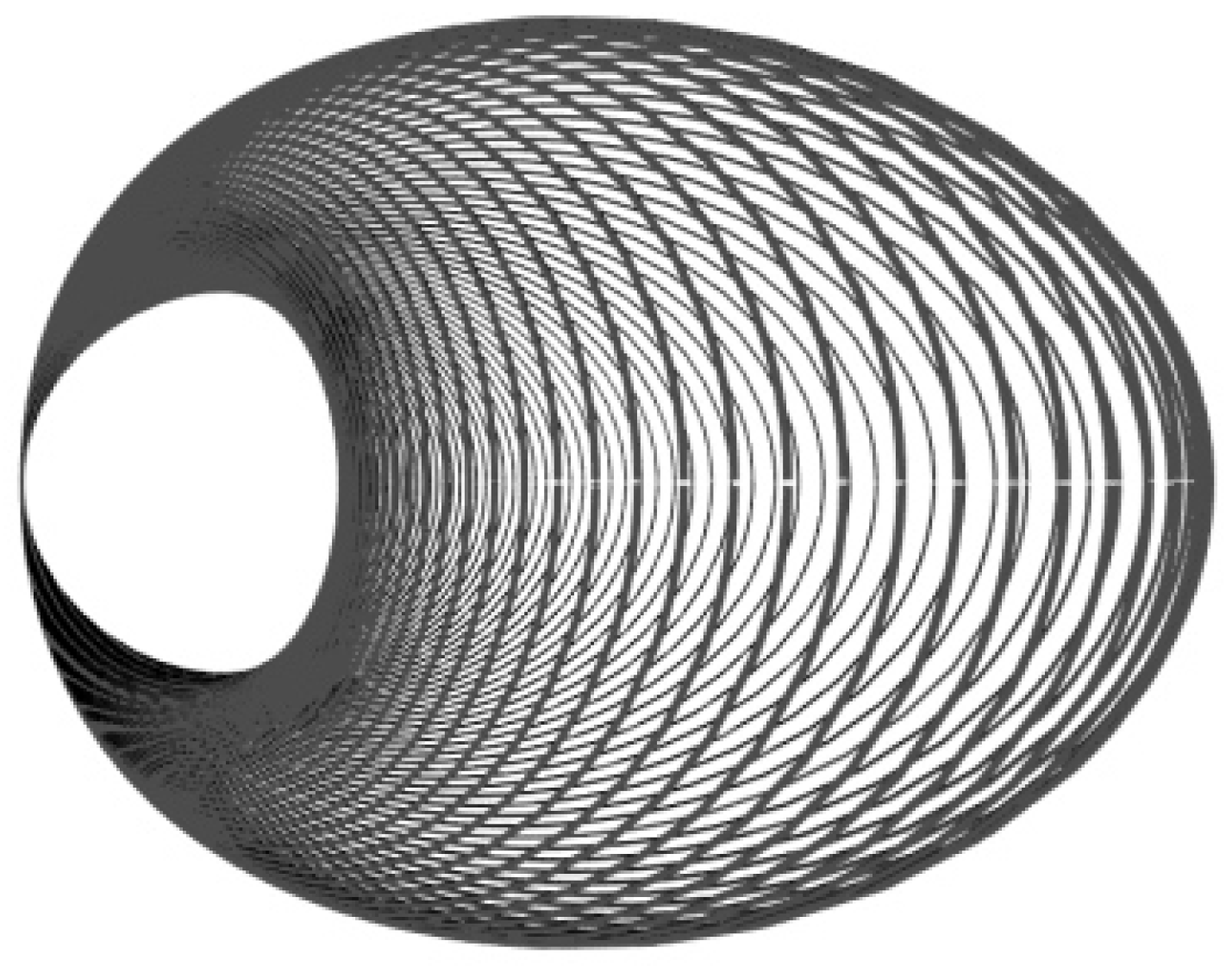

Proposition 12.

Get Γ be a two-dimensional isotropic subspace of Then the submanifold

is a null geodesic in Every null geodesic of is obtained this way. If is any point in then the set of all null geodesics through p corresponds to the set of all isotropic planes containing

Proof. In order to show that

is a null geodesic it is enough to show that

can be covered by open neighbourhood, and each of these neighbourhoods is an open segment of a null geodesic. Let

be an arbitrary point of

We will show that

is a null geodesic in a certain neighbourhood of

In order to analyze a neighborhood of

we choose a point at infinity

satisfying

We will now apply the machinery developed in Proposition 10, and use Lemma 3 to introduce an orthonormal basis in

V in which

Here, and in what follows, we will use a shortcut notation, namely we will write

as

understanding that

x is a four-vector. We have now an open neighbourhood

of

that is diffeomorphic to the Minkowski space. Since

is two-dimensional, there exists in

another null vector, linearly independent from

We call it

If we choose

close enough to

the scalar product

will still be positive, and we can scale

so that

From Eq. (

76) we know that

is of the form

where

a is Minkowski space four-vector,

The condition

immediately implies

, thus

a is a null vector in the Minkowski space, therefore

Now every nonzero vector

X in

can be uniquely represented as

Figure 3.

The pencil (sheaf) of light rays through a space-time point. Temporary illustration.

Figure 3.

The pencil (sheaf) of light rays through a space-time point. Temporary illustration.

Using expressions (

189) and (

192) we get

The scalar product

is positive for

, zero for

and

, and negative otherwise. That means the trajectory is in

for

and crosses the conformal infinity for

and

and is

for other values of

Now that we have a global picture, we concentrate on a neighborhood of the point

Here it is enough to take

which, for

t small enough, is a part of a null geodesic in Minkowski space through the origin, in the direction of the null vector

□

7.3. Light Circling Forever at Infinity and Never Entering Minkowski Space

Given

we have the conformal infinity

at

If

the image by

is contained in

Therefore every null geodesic crossing

p is totally contained in

We will now see how it can be described in coordinates. To this end we will use the parametrization of

as in

Section 6.5. We will use an adapted orthonormal basis in which

. Then any vector orthogonal to

is of the form

where

x is a null vector of the Minkowski space. As we want this vector to be linearly independent of

we must have

In such a case the vectors

and

span the same isotropic plane as

and

Now,

x being a null vector, we can choose it of the form

- it will span, with

the same isotropic plane. Now any vector in this plane is of the form

Comparing the above formula for

with Eqs. (

96), (97) we see that these are exactly the lines of the parameter

u in Eqs. (

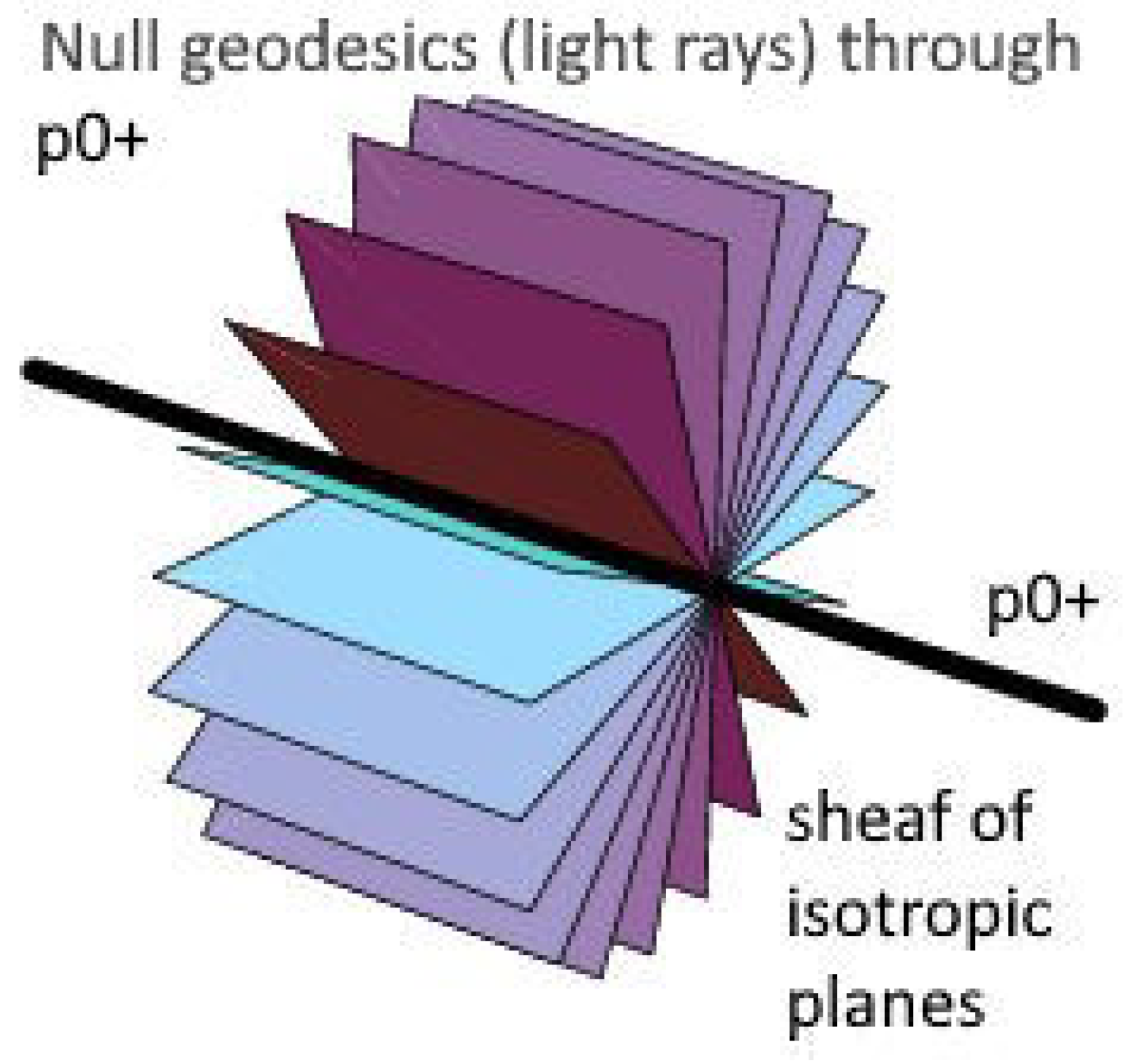

101)-(103), which entails the following graphic representation:

Figure 4.

Null geodesics at conformal infinity.

Figure 4.

Null geodesics at conformal infinity.

7.4. Segal’s `Unitime’

Segal’s `chronometric cosmology’ model [

16] differs from the standard cosmological models by the fact that it is based on a priori selected geometry, not Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, even though it uses many of the concepts of General Relativity. The main

physical idea at the foundations of Segal’s cosmology is the

postulate of existence of a distinguished cosmic

time flow - he calls it

unitime. The prefix `uni’ comes probably from the word `unitary’, as it relates to the action of a specific subgroup of the conformal group SO(4,2), a subgroup isomorphic to the one-parameter Abelian group isomorphic to the group

of complex numbers of modulus

A theoretical physicist would probably ask: “Why should it be so? What is the mechanism of such a symmetry braking? Where is the Lagrangian?" But Segal, a mathematician, has an immediate answer to these questions: "Better check if it IS really so as I say, and if it is so, then you will certainly be motivated to find answers to your questions all by yourself."

As we already know

is isomorphic to

In an orthonormal basis, identifying

V with

and

with the manifold of all

such that

The action of

corresponds to the Euclidean rotation of the

coordinates, other variables being fixed:

Notice that now we pay attention to the physical dimensions and have replaced the parameter s with and have replaced 1 on the right-hand-side of the above equations by a dimensional constant R - the `radius of the universe’.

Remark 8. In such an approach the `flow of time’ has an objective reality. Which agrees with our observations of reality - if flow of time would be entirely subjective, it would be impossible to explain why most of the people agree on the duration of time sequences of events and respect their friends’ birthday dates.

Remark 9. Speaking about `physics’: Segal allows s to be going from minus infinity to infinity, nor just from 0 to In other words we replace by its universal cover, that is by Cosmology becomes cyclic. We have an infinite number of cycles. There is still a question about what is the elementary cycle? Should we identify X with , or not? Is the Minkowski space simple or doubled? Usually it is assumed that it is a simple one, therefore already the interval is assumed to be a cycle. I see no valid reason for such a postulate.

Let us see how Segal’s `unitime’ relates to the coordinate time of the Minkowski space. To this end let us analyze the `unitime line’ through the origin of the Minkowski space in adapted coordinates. We represent Minkowski space event with coordinates

x by its image

as in Eq. (

76). The origin is then represented by

therefore, using Eqs. (

199), the unitime line becomes

In order to find

we divide

by

to obtain

The space origin

remains constant. We see that the unitime line is the same as the time line of the Minkowski space, but

the rate of time is different. Developing into the Taylor series we get

The difference between the two times becomes significant only for big enough in the R-scale.

7.5. Guessing the Metric

In this section, to simplify the notation, let us call the

coordinate simply

t (assuming units in which

). Inverting Eq. (

205) we have

Let us now try to find a metric in the conformal class of the flat Minkowski metric for which

s would be the proper time on the unitime line. We look for a metric of the form

Along the time line

therefore, for the proper time parameter

s we get

Using Eq. (

208) we obtain

8. Compactified Minkowski Space as a Boundary of Five-Dimensional Domains

The null cone

of

V separates two domains

characterized as follows:

Let us consider their projections

(resp.

) obtained by taking the quotient by the equivalence relation

For every point of

(resp.

) there is a unique point

X in

(resp.

) for which

(resp.

Therefore,

can be, respectively, identified with a five-dimensional hyperboloid

defined by

Now is a topological boundary of and of , a four-dimensional boundary that separates these two five-dimensional domains.

Let us look now at the topology of the two five–dimensional domains

For the domain

we have the defining equation

It is then clear that

and

can be arbitrary real numbers, and that introducing

we have

Therefore,

has the topology of

Proceeding the same way with

we have

that is

Therefore has the topology of

8.1. A Coordinate Description of

In

we choose an open set defined by the condition

On this set we introduce five coordinates

defined by

On the other hand, given a point in

with coordinates

we can embed it in

as follows:

Reader is encouraged to verify by a straightforward calculation that with the above definition

and that applying formula (

220) to

we indeed recover

We can now calculate a new metric. In general, when we are dealing with an embedded manifold parameterized by coordinates

its metric

is induced by a metric

on a manifold into which our manifold is embedded, and it is given by the expression

In our case,

and it is easy to calculate

using formula (

221). The result of a straightforward calculation is:

Exactly the same method applies to the region

We get a five–dimensional pseudo–Riemannian, conformally flat manifold of constant curvature and signature

We have covered by coordinates two regions corresponding to different signs of the fifth coordinate. Physicists, when discussing representations of the conformal group with applications to elementary particle physics, often restrict their attention to these regions - Cf. for instance [

22?,

23]. Yet, evidently the group

acts on this part with singularities. Like in the case of Minkowski space, in order to avoid singularities one has to add “conformal infinity”. In our case this is a region where

This conformal infinity of the five–dimensional domain has a simpler structure than the one for the Minkowski space. In fact, setting

in (

216), we get

with no scaling freedom. Therefore, the conformal infinity of our five–dimensional domain

is the Cartesian product of

(

) and the standard two-sheeted hyperboloid of the Minkowski space.

8.2. Christoffel Symbols and Geodesics

Given metric (

223) it is easy (in our coordinate patch) to calculate the Christoffel symbols

and geodesic equations - see e.g. [

24] (Mathematica Programs: Christoffel Symbols and Geodesic Equations). The metric is conformally flat and the only non–vanishing Christoffel symbols are:

The corresponding geodesic equations, when parameterized by an affine parameter

s, are:

where

and

is the flat Minkowski metric

It is interesting to notice that, for

Minkowski’s space null lines

where

is a fixed null vector, are geodesics of the five–dimensional space.

When

is non–constant, it is convenient to choose

as a (non–affine) parameter. The geodesic equations will read in such a case (adapted from [

19] (Appendix B, (B7))) as

which, in our case, reduces to:

Here, we denote by a prime the derivative with respect to

and denote

The direction of the vector

is kept constant along the geodesics. Thus, we need to consider three cases:

and

If

we can use a Lorentz rotation (in the variables

) to set the direction of

along the vector

The differential equations reduce in this case to the following ones:

which, taking into account the constraint

solve to

with

and

constant.

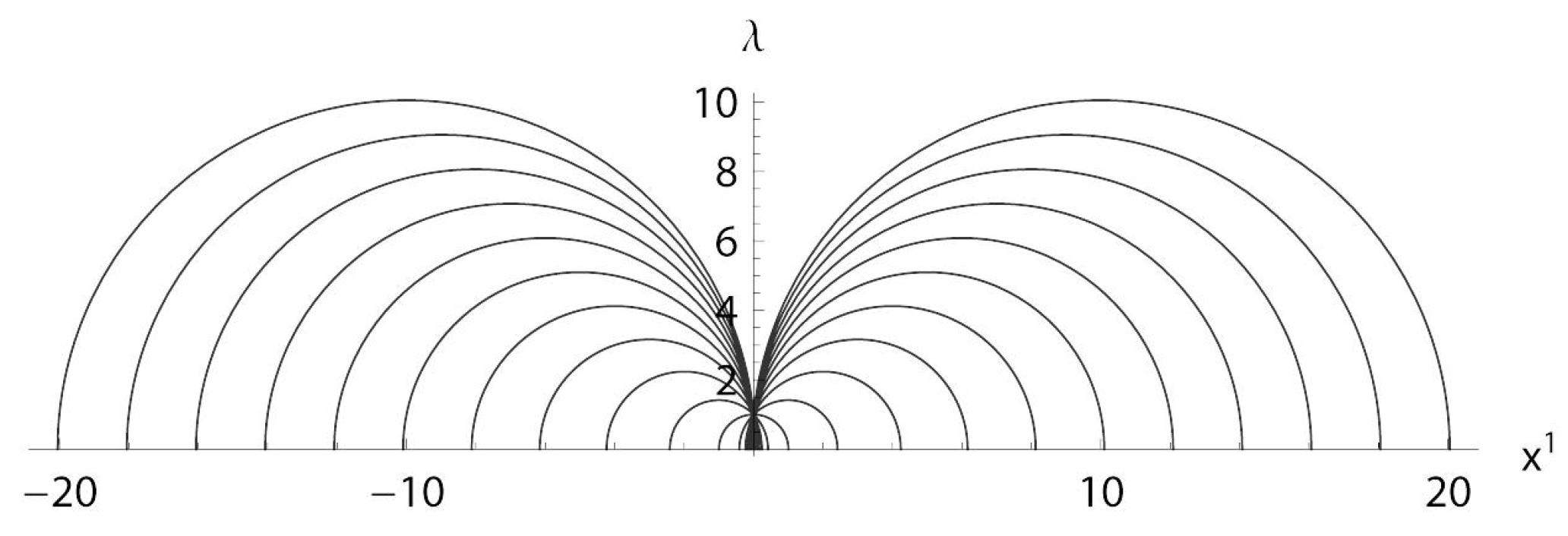

When

we can use a Lorentz rotation to rotate the geodesic into the

plane. The relevant differential equation:

solves to

- a hyperbola.

When

we can Lorentz rotate the geodesic into the

plane, and the differential equation

solves to

- a semi–circle.

Figure 5.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point

Figure 5.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point

Figure 6.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point .

Figure 6.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point .

Figure 7.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point .

Figure 7.

A family of geodesics in the plane through the point .

8.3. as the Space of Hyperboloids

The five–dimensional homogeneous space

can be interpreted as a space of (unoriented) hyperboloids in the Minkowski space along the lines of a generalized Möbius geometry (Cf. e.g., [

4] (Ch. 1.2)). Let

Y be in

with

and

Consider a set of all

for which

Normalizing

Y so that

we can write it in the form

A simple calculation shows that the condition

translates then to

For

this is a double-sheeted hyperboloid with apex at

Each geodesic line in

can thus be interpreted as a particular one–parameter family of hyperboloids in the Minkowski space.

8.4. The Case of

The same method as above applies in this case except that there is a change of signs in front of

in (

221). The resulting metric is then

with signature

As in the case of

, the conformal infinity is the Cartesian product of

and, this time, the one-sheeted hyperboloid

The Minkowski space can be embedded in our five–dimensional manifold simply by putting It follows that the direction of the vector is constant along the geodesics.

Remark 10. Following Wolf [25] we have considered in detail only the case of the equivalence relation In projective geometry one is using the weaker relation The standard projection can be discussed along the same lines as above. In that case the regions and are identified, so we can restrict our attention to 2 On the other hand, when discussing the topology - we have to additionally take the quotient by

9. Conclusions

In this work the conformal compactification of Minkowski space has been revisited in an explicit and pedagogical manner, starting from the projective null cone in and its identification with the unitary group . The role of the double cover has been clarified, with particular emphasis on the effectiveness of the action and on the detailed geometry of conformal infinity, described in terms of horn and needle Dupin cyclides. By combining concrete coordinate constructions, explicit matrix formulas for the conformal group and its subgroups, and a coordinate-free reformulation in the spirit of Kopczyński and Woronowicz, the paper aims to provide a transparent geometric picture that can serve both as a reference and as a pedagogical introduction to conformal compactification in mathematical relativity and conformal field theory.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to R. Coquereaux for his interest and for a stimulating discussion on related subjects at the early stage of this work. I wish to thank my wife, Laura, for her constant support. This work was supported by Quantum Future Group Inc.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Penrose, R.; Rindler, W. Spinors and space-time; Cambridge University Press, 1986; ISBN 0521347866. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, A. The Closure of Minkowski Space. Acta Physica Polonica 1963, Vol. XXIV, Fasc. 2(8), 295–296. [Google Scholar]

- Barbot, T.; Charette, V.; Drumm, T.; M. Goldmann, W.N.; Melnick, K. A primer on the (2+1) Einstein universe. [CrossRef]

- Cecil, Thomas E. Lie Sphere Geometry, 2nd ed.; Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morava, J. At the boundary of Minkowski space. arXiv [math-ph]. 2021, arXiv:2111.08053v3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lester, J.A. Conformal Minkowski Space-time. Il Nuovo Cimento 1982, 72 B(N. 2), 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyński, W.; Woronowicz, L.S. A Geometrical Approach to the Twistor Formalism. Reports on Mathematical Physics 1971, 2, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, J.A. Orthochronous Subgroups of O(p,q). Linear and Multilinear Algebra 1993, Vol. 36, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokov, D.S. Lectures on Clifford Algebras and Spinors. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267112376_Lectures_on_Clifford_algebras_and_spinors.

- Mneimné, R.; Testard, F. Groupes de Lie classiques; Hermann, 2009; ISBN 9782705660406. [Google Scholar]

- Werth, J.-E. Conformal Group Actions and Segal’s Cosmology. Reports on mathematical physics 1986, 23, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artmann, Benno. PICTURES of the PROJECTIVE PLANE, in Günter Törner, and Bharath Sriraman. Beliefs and Mathematics: Festschrift in Honor of Günter Törner’s 60th Birthday; Charlotte, NC, Information Age, 2008; Available online: http://www.math.umt.edu/tmme/Monograph3/Artmann_Monograph3_pp.3_16.pdf.

- Hilbert, D. S Cohn-Vossen Geometry and the Imagination; Ams Chelsea: Providence, Ri., 1999; ISBN 9780821819982. [Google Scholar]

- Schrott, M.; Odehnal, B. Ortho-Circles of Dupin Cyclides. Journal of Geometry and Graphics 2006, 1, 73–98. Available online: http://www.heldermann-verlag.de/jgg/jgg10/j10h1schr.pdf.

- Feréol, R. Cyclide de Dupin. Available online: https://www.mathcurve.com/surfaces/cycliddedupin/cyclidededupin.shtml (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Segal, I.E. Mathematical Cosmology and Extragalactic Astronomy; Academic Press, 1976; ISBN 9780080873848. [Google Scholar]

- Berestovskiĭ, V N. To the Segal Chronometric Theory. Siberian Advances in Mathematics 2023, 33(no. 3), 165–180. 165–180. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.06866. [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, R.L. Conformal Relativity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1952, 38, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Weiskopf, D. Detailed Study of Null and Timelike Geodesics in the Alcubierre Warp Spacetime. General Relativity and Gravitation [gr-qc]. 2011, arXiv:1107.565044, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, S.A.; Tod, K.P. An Introduction to Twistor Theory; Cambridge University Press, 1994; ISBN 9780521456890. [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault, A. Irving Segal’s Axiomatization of Spacetime and Its Cosmological Consequences. arXiv (Cornell University) 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham, R.L. Conformal Relativity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1952, 38, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingraham, R.L. Particle Masses and the Fifth Dimension. Annales de la fondation Louis de Broglie/Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie 2000, 29, 989–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Hartle, J.B. Cambridge University Press Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein’s General Relativity; Cambridge Cambridge University Press; ISBN 9781316517543, 2021; Available online: http://web.physics.ucsb.edu/~gravitybook/math/.

- Wolf, J.A. Spaces of Constant Curvature; American Mathematical Society, 2023; ISBN 9781470473655. [Google Scholar]

- Juergen, Elstrodt; Grunewald, F. Jens Mennicke Groups Acting on Hyperbolic Space; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013; ISBN 9783662036266. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, T.; Penrose, R. Penrose’s Weyl Curvature Hypothesis and Conformally-Cyclic Cosmology. Journal of physics 20. Penrose, R. On the Gravitization of Quantum Mechanics 2: Conformal Cyclic Cosmology. Foundations of Physics 2013, 44, 873–890. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

Ref. [ 11] (Proposition 8) ascertains the existence of the action of on . Here we have its explicit realization |

| 2 |

That is why a similar coordinatization is often referred to as the “half–space model” in literature on hyperbolic geometry - see e.g. [ 26]. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).