Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental condition with heritability estimates approaching 75 %. Prevalence studies place its point estimate between 5 % and 7 % in childhood, and longitudinal work shows that clinically significant symptoms persist for many individuals into adult life. First-line pharmacotherapy relies on psychostimulants that enhance catecholaminergic transmission, yet a sizable subset of treated patients continue to experience executive and emotional difficulties. These therapeutic gaps have prompted a shift from single-transmitter explanations toward developmental circuit models. Structural MRI has been central to this transition: children with ADHD reach peak cortical thickness later than typically developing peers, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, while otherwise following the normative sequence of maturation [

1,

2]. Such right-shifted trajectories suggest a delay, rather than a deviance, in processes that sculpt cortical networks.

One way to make sense of ADHD's developmental lag is to look at synaptic pruning, the brain's normal process of trimming away extra connections as experience shapes neural circuits. If this pruning runs short, local networks stay overcrowded and noisy, making it harder for the brain to sort and sustain attention. Functional-connectivity scans point in that direction: children with ADHD linger longer in hyper-connected brain states that match up with inattentive behaviour [

3]. Post-mortem and immune studies tell a similar story, linking faulty pruning to shifts in microglial activity and complement signalling across several psychiatric conditions [

4].

Yet the genetic paperwork for a pruning problem in ADHD is still thin. The biggest genome-wide association study so far flagged 27 risk loci and 76 genes that are active early in brain development, but its pathway analysis never pulled pruning to the foreground [

5]. The alternative idea—that glutamatergic glitches underlie the disorder because NMDA and AMPA receptors steer plasticity and drugs like memantine offer modest help—hasn't found firm polygenic backing either.

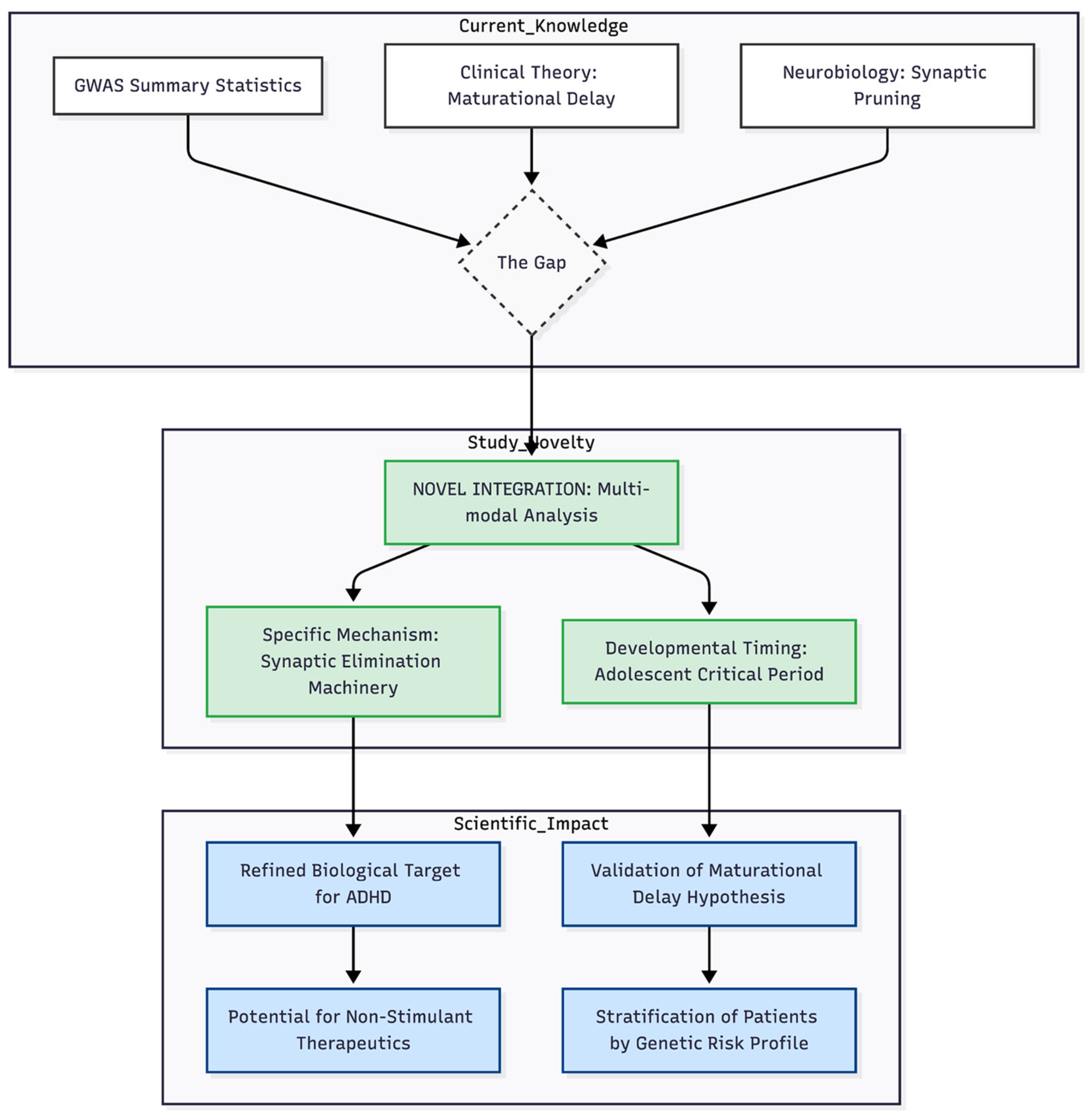

To clarify how common variation contributes to ADHD, we re-examined the 2023 GWAS summary statistics with a multi-layered analytic framework. Competitive gene- and gene-set testing (MAGMA), stratified linkage-disequilibrium-score regression, and transcriptome-wide association studies (S-PrediXcan) were combined to probe six predefined gene sets (Appendix I). Two sets captured glutamatergic signalling (a narrow receptor list of 23 genes and a broader list of 130 genes), two indexed synaptic pruning (a focused list of 38 core genes and an extended catalogue of 262 genes spanning complement activation, microglial phagocytosis, axonal guidance cues, cytoskeletal remodelling, and activity-dependent transcription), and two served as negative controls (monoaminergic and housekeeping genes). This design enables a direct test of whether pruning-related machinery carries disproportionate common-variant risk, while benchmarking signals against glutamatergic and control pathways.

The results presented below provide convergent polygenic support for widespread dysregulation of pruning genes in ADHD. Signals were consistent across analytic layers and absent from control sets, positioning delayed circuit refinement—not primary catecholaminergic or glutamatergic defects—as a central etiological theme. These findings refine current neurodevelopmental models and point toward therapeutic strategies that modulate synaptic elimination or enhance compensatory plasticity.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

Gene- and gene-set association testing was undertaken with MAGMA version 1.10 [

6]. The program collapses single-marker statistics into gene-level test scores while adjusting for linkage disequilibrium (LD), and then evaluates whether predefined collections of genes show stronger evidence of association than the genomic background. Publicly available summary statistics from the latest ADHD genome-wide association meta-analysis were supplied as input; these data comprise 38,691 diagnosed cases and 186,843 controls [

5].

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were assigned to protein-coding genes defined in the NCBI37.3 build (hg19/GRCh37). In order to capture nearby regulatory elements, the canonical gene coordinates were padded by 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream. LD estimates were taken from the European subset of the Phase 3 release of the 1000 Genomes Project [

7]. After filtering, 6,774,224 autosomal SNPs with valid p values annotated 18,220 genes.

Six hypothesis-driven gene sets were analysed with MAGMA's competitive model. Two sets targeted glutamatergic signalling: (i) a narrow panel of 23 receptor or receptor-interacting genes (CGR_Targets_Original) and (ii) an expanded panel of 130 genes representing 14 functional subcategories that included NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptors as well as BDNF-TrkB and mTOR components. Two further sets focused on synaptic pruning: (iii) a concise list of 38 pruning-related genes and (iv) a broad list of 262 genes covering 25 mechanistic categories such as complement activation, semaphorin-plexin signalling, Wnt pathways and transcriptional regulators. Finally, two negative-control collections were analysed: (v) 101 genes involved in monoaminergic neurotransmission and (vi) 182 widely expressed housekeeping genes. For each set MAGMA compared the mean gene-wise Z statistic inside the set with the genome-wide distribution, equivalent to a one-sided one-sample t test. Family-wise error control across the six tests used a Bonferroni threshold of 0.0083; false-discovery-rate (FDR) adjusted q values were also computed.

Annotation Chi-Square Enrichment and Partitioned Heritability Analysis

We evaluated whether specific biological pathways account for more of the common-variant liability to ADHD than expected by chance. Stratified linkage-disequilibrium score regression (S-LDSC) was applied in a streamlined form (without LD reference; Annotation Chi-square Enrichment) that follows the procedure introduced by Finucane and colleagues [

8]. The same analysis was repeated with LD reference (Partitioned Heritability Analysis).

Genome-wide summary statistics came from the most recent ADHD meta-analysis (38,691 cases, 186,843 controls; [

5]). Throughout, we used the effective sample size (N_eff = 128,213) recommended for unbalanced designs. Quality control retained variants with INFO ≥ 0.9 and minor-allele frequency ≥ 0.01, leaving roughly 6.7 million SNPs. LD scores for all autosomal variants were calculated from the European Phase-3 panel of the 1000 Genomes Project [

7].

Six binary annotations were created. Four corresponded to the gene collections interrogated in our earlier gene-based work: (i) 23 candidate glutamatergic receptor genes (CGR_Targets_Original), (ii) an expanded glutamatergic list of 130 genes, (iii) a concise synaptic-pruning list of 38 genes and (iv) a broad pruning list of 262 genes. Two additional sets served as negative controls: 101 monoaminergic genes and 182 housekeeping genes. Gene coordinates were taken from GRCh37/hg19 and padded by ±10 kb to capture nearby regulatory sequence; sex-chromosome genes were omitted to match the reference LD panel. Each annotation included every SNP falling within the extended boundaries of its member genes.

For each category S-LDSC compared the mean χ² statistic of SNPs inside the annotation with the mean outside. Enrichment was defined as the ratio of these means. Standard errors were obtained with a 200-block jack-knife and one-sided tests were used because prior work suggested directional expectations. Significance across the six primary annotations was controlled with Bonferroni (α ≈ 0.0083) and Benjamini–Hochberg FDR. Complementary Mann–Whitney U tests compared the full distributions of χ² values.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS)

We assessed whether genetically regulated gene expression in selected brain regions contributes to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) liability by carrying out transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) with S-PrediXcan. This approach couples genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics with pre-trained expression-prediction models so that the genetically driven component of expression (GReX) can be imputed and tested for association with the phenotype [

9,

10].

GWAS input consisted of the latest ADHD meta-analysis (38,691 cases, 186,843 controls; effective N = 128,213) described by [

5]. After harmonising alleles, positions and Z-scores, variants with missing information were removed and the cleaned summary file was converted to S-PrediXcan format. For transcriptomic reference, we used GTEx v8 elastic-net models refined with MASHR shrinkage for six brain regions implicated in ADHD: frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), hippocampus, amygdala, caudate nucleus and nucleus accumbens.

Within each tissue, S-PrediXcan calculated a Z-statistic for every gene by correlating imputed GReX with ADHD risk while accounting for linkage disequilibrium among predictor SNPs. Gene-level p values were derived from these Z-scores and adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg false-discovery rate (FDR). We then examined six predefined gene sets: (i) the original 23 glutamatergic receptor (CGR) targets, (ii) an expanded glutamatergic list (130 genes), (iii) a concise synaptic-pruning list (38 genes), (iv) an expanded pruning list (262 genes) and two negative-control sets, (v) monoaminergic genes (101) and (vi) housekeeping genes (182). For enrichment tests, absolute TWAS Z-scores of genes in each set were compared with those of all other genes by two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests.

Results

MAGMA Analysis

The gene-based scan yielded 60 genome-wide significant genes after Bonferroni correction for 18,220 tests (α = 2.74 × 10⁻⁶). A further 438 genes displayed suggestive evidence (p < 0.001) and 2,974 were nominally significant (p < 0.05). Top signals included MEF2C (p = 1.33 × 10⁻¹⁰), FOXP2 (p = 1.20 × 10⁻⁹), DCC (p = 2.31 × 10⁻¹⁰) and SORCS3 (p = 4.19 × 10⁻¹⁰), genes previously linked to activity-dependent transcription, corticostriatal development or axon guidance, all processes thought to be relevant for ADHD pathophysiology.

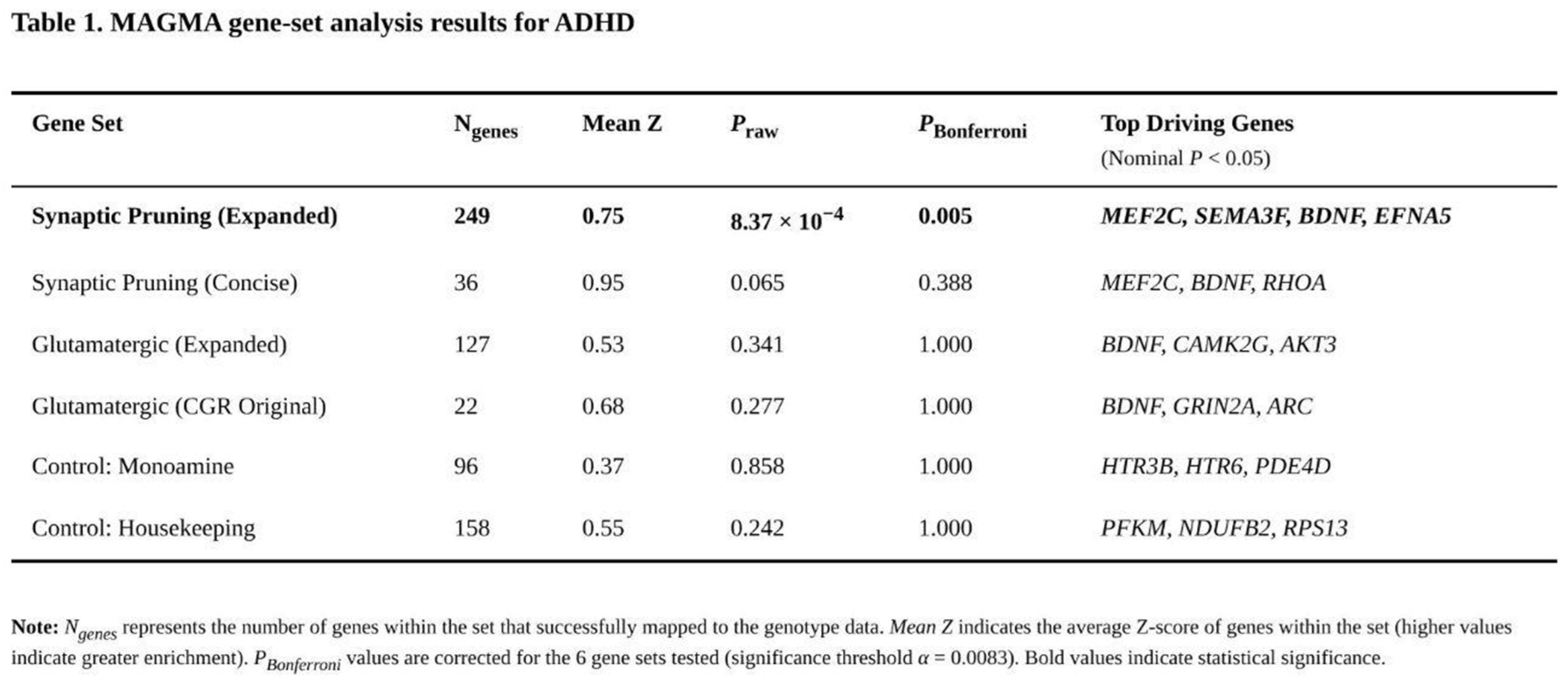

Only one of the six predefined gene sets surpassed the multiple-testing threshold (Table 1). The expanded pruning list (262 genes, 249 mapped) showed a raw enrichment p = 8.37 × 10⁻⁴, translating to Bonferroni-corrected p = 0.005 and FDR = 0.005. Fifty-seven members of this set were nominally associated with ADHD, and two—MEF2C and SEMA3F—were among the genome-wide significant hits. Post-hoc inspection of functional sub-categories pointed to transcription factors (mean Z = 1.30), semaphorin-plexin signalling (mean Z = 0.93) and cytoskeletal remodelling (mean Z = 0.87) as primary contributors. The concise pruning panel trended in the same direction (raw p = 0.065; corrected p = 0.388) with 13 nominally significant genes, again headed by MEF2C.

Neither glutamatergic collection displayed enrichment. The 22 mapped genes from the original CGR panel produced a raw p = 0.277, whereas the 127 mapped genes in the expanded glutamatergic list yielded p = 0.341. Both sets contained individual nominal signals—for example BDNF (p = 2.02 × 10⁻⁵) and GRIN2A (p = 0.002)—yet their average Z scores did not exceed genome-wide expectations. As anticipated, the monoamine (raw p = 0.858) and housekeeping (raw p = 0.242) control sets were unremarkable.

A pairwise Mann–Whitney comparison confirmed that the expanded pruning set's gene-wise Z scores were higher than those of the monoamine control (p = 0.008) and showed a non-significant tendency relative to housekeeping (p = 0.107). No analogous differences emerged for either glutamatergic set. Collectively, these results indicate reproducible polygenic enrichment of ADHD associations within broad pathways governing synaptic elimination, whereas genes involved in canonical glutamatergic signalling or monoaminergic neurotransmission do not carry disproportionate common-variant burden in the present dataset.

Annotation Chi-Square Enrichment

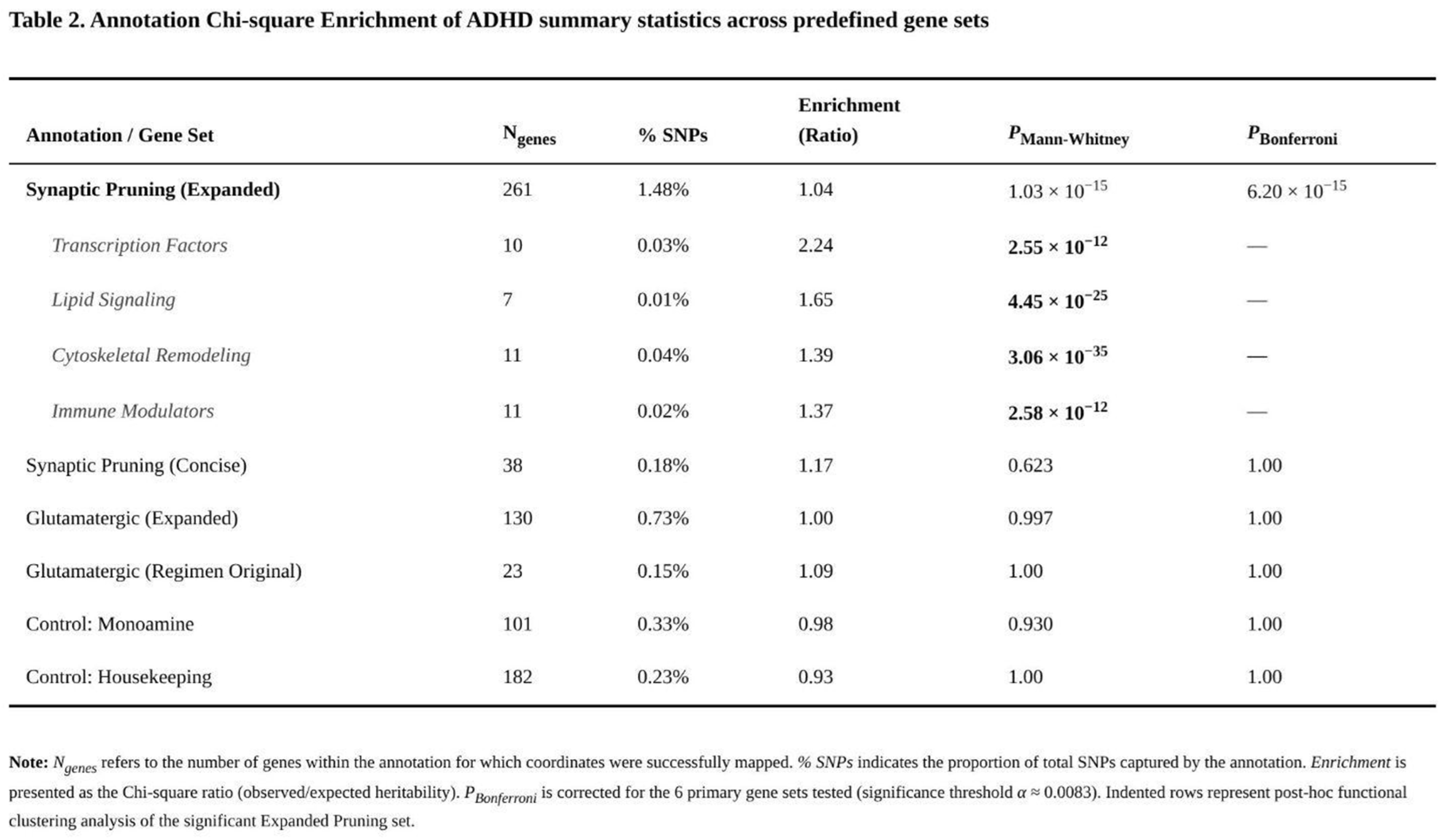

Among the six predefined annotations, only the broad synaptic-pruning list—261 autosomal genes representing 1.48 % of SNPs—captured a significantly greater share of ADHD heritability than expected (Table 2). The raw enrichment (χ² ratio = 1.04) remained after LD adjustment (1.08) and was highly significant (Mann–Whitney p = 1.03 × 10⁻¹⁵; Bonferroni-corrected p = 6.20 × 10⁻¹⁵). The smaller pruning list (36 genes; 0.18 % of SNPs) showed the same direction of effect (χ² ratio = 1.17) but wider confidence limits after LD correction (0.81) and did not survive multiple-testing control (p = 0.569).

Neither glutamatergic annotation showed convincing evidence of enrichment. The original 22-gene CGR set (0.15 % of SNPs) yielded a χ² ratio of 1.09 before LD correction and 1.26 after, yet the Mann–Whitney test was non-significant (p ≈ 1). The expanded 127-gene glutamatergic set (0.73 % of SNPs) was effectively null (raw ratio = 0.999; LD-adjusted = 1.20; p ≈ 1). The monoaminergic control set (97 genes, 0.33 % of SNPs) produced a ratio of 0.99 (LD-adjusted 1.29; p = 0.915) and the housekeeping set (175 genes, 0.23 % of SNPs) showed a slight depletion (raw ratio = 0.93; LD-adjusted 0.98; p ≈ 1).

Sub-analyses of the broad pruning annotation highlighted several functional clusters. Transcription-factor genes showed the strongest excess (χ² ratio = 2.24), followed by lipid-signalling (1.65), immune-modulatory (1.37) and cytoskeletal-remodelling genes (1.39). Many subcategories had Mann–Whitney p values below 10⁻¹⁰. Together with our earlier gene-level findings, these results indicate that pathways involved in synaptic elimination and neuronal remodelling contribute disproportionately to ADHD risk, whereas canonical glutamatergic or monoaminergic genes do not.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

Only the broad synaptic-pruning category showed clear evidence of enrichment (Table 3). This annotation comprised 253 autosomal genes, representing 1.49 % of the analysed SNPs. Its SNPs carried, on average, 4 % larger χ² statistics than background SNPs (raw ratio = 1.04), a difference that remained after LD adjustment (1.08) and was highly significant (Mann–Whitney p = 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁹; Bonferroni-corrected p = 6.0 × 10⁻¹⁹). The concise pruning list displayed the same direction of effect but lacked statistical support once LD was considered (adjusted ratio = 0.81; p = 0.57).

Neither glutamatergic annotation carried an excess of signal. The focused 23-gene set (0.15 % of SNPs) yielded an adjusted ratio of 1.26 but a non-significant Mann–Whitney test (p ≈ 1). The enlarged glutamatergic list (0.73 % of SNPs) was effectively neutral (adjusted ratio = 1.20; p ≈ 1). Control sets behaved as expected: monoaminergic genes (0.33 % of SNPs) and housekeeping genes (0.23 % of SNPs) showed no enrichment (adjusted ratios = 1.29 and 0.98, respectively; p > 0.9).

Taken together, the partitioned heritability results reinforce the gene-level findings, indicating that common ADHD risk variants accumulate preferentially within pathways governing synaptic pruning and developmental remodelling, not within canonical glutamatergic or monoaminergic gene sets.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS)

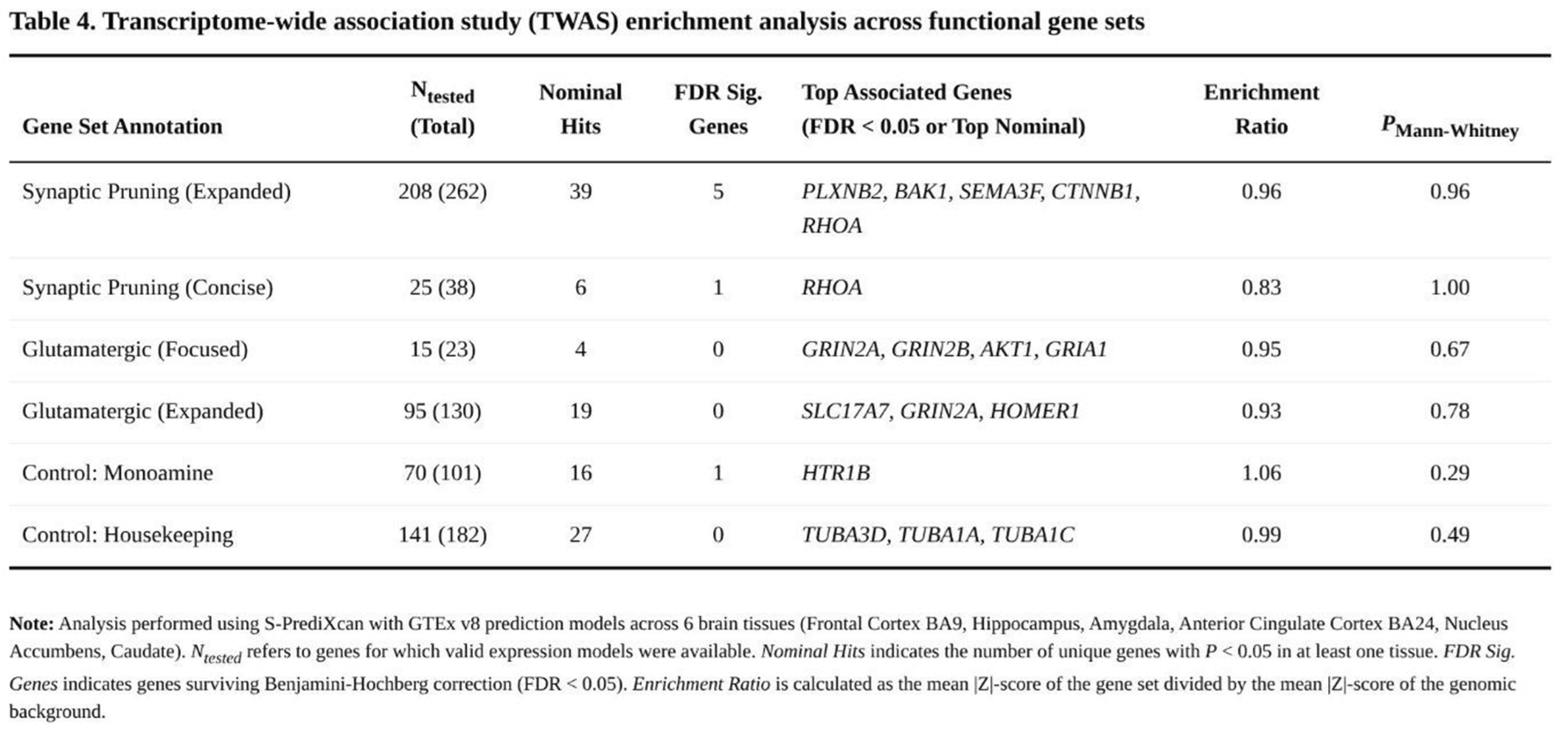

Across roughly 61,700 gene–tissue combinations (~15,400 genes per tissue), 568 associations met the FDR < 0.05 threshold, representing 253 unique genes. Significant signals were highly tissue-specific; nonetheless, none of the four hypothesised glutamatergic or pruning panels showed global enrichment when contrasted with the genomic background (Table 4).

Within the expanded pruning panel, five genes exceeded the FDR threshold—PLXNB2, BAK1, SEMA3F, CTNNB1 and RHOA—primarily in frontal cortex and caudate. The shorter pruning list yielded one significant finding (RHOA in hippocampus). By contrast, the original CGR set produced only nominal associations for GRIN2A, GRIN2B, AKT1 and GRIA1, and the larger glutamatergic list generated 19 nominal hits but none that withstood FDR correction.

Control sets displayed comparable patterns. Among monoaminergic genes, HTR1B was significant in amygdala and 16 additional genes showed nominal evidence. The housekeeping panel yielded 27 nominal associations but no FDR-significant results. Mann–Whitney analyses confirmed an absence of enrichment for the candidate pathways (all p > 0.28). Mean |Z| scores ranged from 0.83 to 0.96 for candidate panels and from 0.99 to 1.06 for control genes, indicating no systematic elevation in the focal pathways.

Overall, TWAS highlighted a limited number of brain-tissue–specific genes but did not provide broad support for transcriptional dysregulation within the predefined glutamatergic or synaptic-pruning pathways. These observations contrast with stronger pathway signals previously observed through SNP-based heritability partitioning, suggesting that common regulatory variation captured by current expression models explains only a fraction of the pathway involvement inferred from GWAS.

Discussion

Convergent Genetic Evidence for Developmental Pruning

By integrating competitive gene-set tests, stratified heritability analyses and S-PrediXcan, we demonstrate that common-variant liability for ADHD is disproportionately concentrated in genes that orchestrate synaptic pruning and circuit refinement. Roughly 260 pruning-related genes—covering complement tagging, microglial engulfment, semaphorin and ephrin cues, WNT modulators, cytoskeletal remodelers and activity-dependent transcription factors—were enriched in every analytic layer, whereas monoaminergic and housekeeping panels were uniformly null. These data extend earlier neuroimaging work showing a protracted trajectory of cortical thinning and delayed peak thickness in prefrontal cortex [

1] and support the view that ADHD reflects quantitative postponement of a normally timed maturational programme rather than a deviant sequence [

2]. Reports of persistent hyper-connectivity and noisy network states in paediatric and adult cohorts [

3,

11] can now be anchored to polygenic enrichment in pruning machinery that influences the elimination of redundant connections. Key contributors—such as MEF2C-regulated immediate early genes and semaphorin–plexin pathways—echo proposals that incompletely refined circuits underlie the maintenance of immature activity patterns in ADHD [

4,

12].

Implications for Glutamatergic Models

Contrary to long-standing hypotheses derived from animal work, glutamatergic receptor sets did not show pathway-level enrichment, despite sporadic nominal hits for genes such as GRIN2A and GRIN2B. This discrepancy suggests that NMDA and AMPA abnormalities detected in experimental models may arise secondarily from pruning inefficiency rather than constitute primary genetic drivers. Shared elements—mTOR and BDNF–TrkB signalling, for example—link the two pathways and probably account for occasional single-gene signals without yielding aggregate enrichment (

Figure 1).

Clinical Translation Across Developmental Stages

Taken together, the results support a stepwise, developmental view of ADHD. In late childhood, just as the brain's normal "pruning" surge gets underway, stimulants paired with behavioural therapy still make sense because dopaminergic drugs seem to regulate the activity-dependent trimming of synapses in the prefrontal cortex [

13]. When that pruning is still unfinished by adolescence, the brain may swing the other way and prune too aggressively, a pattern reminiscent of the stress-linked synaptic losses seen in mood disorders [

14,

15], which could help explain why teens with ADHD often develop internalising problems. At that point, treatments like ketamine or other glutamatergic regimen that gently push the system back toward building new connections might revive plasticity [

16].

Methodological Considerations

Several design features temper interpretation. Custom pruning and glutamatergic lists, although biologically motivated, require replication in independent cohorts to exclude circularity. TWAS relies on adult expression reference panels, leaving developmental isoforms and low-abundance transcripts under-represented. Heritability partitioning is sensitive to annotation width; our ±10 kb window is conservative but arbitrary. Finally, common variants capture only a portion of ADHD risk; rare coding variants and environmental moderators undoubtedly influence pruning efficiency.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. .

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Shaw, P.; Eckstrand, K.; Sharp, W.; Blumenthal, J.; Lerch, J.P.; Greenstein, D.; Clasen, L.; Evans, A.; Giedd, J.; Rapoport, J.L. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 19649–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubia, K. Neuro-anatomic evidence for the maturational delay hypothesis of ADHD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 19663–19664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shappell, H.M.; Duffy, K.A.; Rosch, K.S.; Pekar, J.J.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Lindquist, M.A.; Cohen, J.R. Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder spend more time in hyperconnected network states and less time in segregated network states as revealed by dynamic connectivity analysis. NeuroImage 2021, 229, 117753–117753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva, P.N. Do patterns of synaptic pruning underlie psychoses, autism and ADHD? BJPsych Adv. 2018, 24, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, D.; Walters, G.B.; Athanasiadis, G.; Walters, R.; Therrien, K.; Nielsen, T.T.; Farajzadeh, L.; Voloudakis, G.; Bendl, J.; Zeng, B.; et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, C.A.; Mooij, J.M.; Heskes, T.; Posthuma, D. MAGMA: Generalized Gene-Set Analysis of GWAS Data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al.; Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, H.K.; Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Gusev, A.; Trynka, G.; Reshef, Y.; Loh, P.-R.; Anttila, V.; et al.; ReproGen Consortium; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; The RACI Consortium Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamazon, E.R.; GTEx Consortium; Wheeler, H.E.; Shah, K.P.; Mozaffari, S.V.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Carroll, R.J.; Eyler, A.E.; Denny, J.C.; Nicolae, D.L.; et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, A.N.; Dickinson, S.P.; Bonazzola, R.; Zheng, J.; Wheeler, H.E.; Torres, J.M.; Torstenson, E.S.; Shah, K.P.; Garcia, T.; Edwards, T.L.; et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolonen, T.; Roine, T.; Alho, K.; Leppämäki, S.; Tani, P.; Koski, A.; Laine, M.; Salmi, J. Abnormal wiring of the structural connectome in adults with ADHD. Netw. Neurosci. 2023, 7, 1302–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakuszi, B.; Szuromi, B.; Bitter, I.; Czobor, P. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Last in, first out - delayed brain maturation with an accelerated decline? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Lin, W.-P.; Huang, L.-P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, C.-C.; Yin, D.-M. Dopamine D2 receptor regulates cortical synaptic pruning in rodents. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H.-S.; Li, H.-H.; Wang, H.-J.; Zou, R.-S.; Lu, X.-J.; Wang, J.; Nie, B.-B.; Wu, J.-F.; Li, S.; et al. Microglia-dependent excessive synaptic pruning leads to cortical underconnectivity and behavioral abnormality following chronic social defeat stress in mice. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2022, 109, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, P.K.; Johnson, S.B.; Liston, C. Synaptic Mechanisms Regulating Mood State Transitions in Depression. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 45, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. Proposing a novel glutamatergic regimen as a missing link in ADHD treatment [Preprint]. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |