1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) represents a highly heterogeneous group of hematologic malignancies characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of undifferentiated blast cells, accumulation of leukemic cells in bone marrow microenvironment (BMM) and clonal expansion in bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood. In the era of next generation sequencing (NGS), numerous somatic mutations have been identified in hematopoietic stem (HSCs) and progenitor cells, influencing disease prognosis and modifying the current risk stratification according to the European Leukemia Net (ELN) 2022. The clinical outcome and prognosis are significantly influenced by the underlying molecular and cytogenetic abnormalities along with the age of diagnosis and comorbidities. Despite this expansion in the mutational landscape of AML, the therapeutic combination of cytarabine and anthracycline, "3+7" as induction treatment, remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed and fit patients. However, relapsed or refractory AML is a common scenario and the most challenging aspect, while in younger patients’ long-term overall survival (OS) rates are only 40–50% and even worse in older adults, with median OS typically under one year.

Leukemic stem cells (LSCs), also referred to as leukemia-initiating cells (LICs), are now established as a distinct cell subpopulation in BM, acquiring distinctive properties of quiescence, self-renewal and proliferation through clonal outgrowth and continuous genetic and epigenetic modifications. Several studies revealed that the existence of a small subpopulation of LSCs in the BM niche is associated with chemotherapy resistance and thus disease relapse as they can repopulate leukemia cells. The BMM plays a crucial role not only in supporting haematopoiesis, through myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis but also in leukemogenesis, disrupting the BM niches of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells and creating a microenvironment suitable for LSCs’ survival and proliferation [

1,

2,

3].

In this state-of-the-art narrative review, we prioritize clinically actionable evidence and recent translational studies to provide(i) a translational framework for LSC identification across AML subtypes, (ii) a practical integration of LSC measurement with measurable residual disease (MRD), and (iii) a 2025-updated appraisal of LSC-directed therapies using a targetability lens that prioritizes clinical feasibility, safety, and resistance biology.

2. Biological Features of LSCs

The first in vivo experiments that demonstrated the existence and leukemogenic potential of LSCs were those carried out by Lapidot, Dick and colleagues. They showed that primitive CD34+/CD38- cells from patients with AML could engraft in mice with severe common immunodeficiency (SCID mice), self-renew, proliferate and differentiate into leukemic blasts, generating leukemia in mice, and were considered as LICs [

4,

5].

Following these discoveries, several efforts have been made to establish a theory that best explains the leukemia initiating process. Of these, the most widely accepted seems to be the hierarchical model which resembles the organization of normal haematopoiesis. In the continuous, physiological process of haematopoiesis, a rare population of multipotent HSCs differentiate into progenitor cells committed to specific blood cell lineages, while retaining self-renewal capacity, thereby preserving the HSCs pool. This organization might also be the case in AML, with rare LSCs standing at the hierarchical apex and giving rise to more committed cells, the leukemic blasts, sustaining the whole leukemic cell mass [

6,

7,

8].

However, the cell of origin in AML remains a topic of ongoing debate. According to the most widely accepted theory, at some timepoint, a first mutation of a HSC may affect epigenetic genes or genes of histone modification such as

DNMT3A or

ASXL1, but without the ability to generate leukemia. After a substantial period, another mutation (second hit) in genes regulating cell signalling or cellular proliferation may convert the pre-leukemic HSCs into actual LSCs which can, in turn, initiate leukemia [

6,

7].This multi-step process is later discussed in detail. However, Cozzio et al. showed that the

MLL fusion gene, recurrently found in AML, can provide HSCs and progenitor cells with immortality and self-renewal capacity, converting them into LICs and, hence, AML could actually arise not only from stem cells at the top of the hierarchy, but also from more mature committed myeloid progenitors [

9].

As previously mentioned, LSCs have several biological characteristics, some of which are similar to those of normal HSCs, underlying their stemness and close relation to their normal counterparts. Like normal HSCs, LSCs comprise a very rare cellular population in the BM compartment, approximately 0.1%, compared to the expanded leukemic blast population and are mainly in a quiescent state [

10]. Additionally, LSCs have self-renewal capacity, which means that they can replicate and preserve their initial population of LSCs. At the same time, LSCs can differentiate into more mature cellular stages, mainly leukemic blasts, which gradually lose their self-renewal and differentiation capacity. Furthermore, stem cells are characterized by drug resistance, which, in the case of HSCs is responsible for normal haematopoiesis restoration after chemotherapy, but it could also be the reason for AML relapse after achieving CR, when it comes to LSCs [

6]. On the other hand, LSCs have acquired genetic mutations, as previously discussed, and phenotypic characteristics such as altered metabolic properties or aberrant RNA editing, which give them survival and proliferative advantages translated into leukemogenic potential and, therefore, differentiate them from normal HSCs. Such inherent differences have been exploited by scientists to develop therapeutic strategies targeting LSCs while sparing normal HSCs. For example, in AML LSCs are characterized by low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and are highly dependent on mitochondrial catabolism of amino-acids and fatty acids and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) rather than glycolysis as in non-malignant HSCs [

11,

12].Moreover, it has been found that with alternative splicing, LSCs can enhance the expression of anti-apoptotic molecules including BCL2 and MCL1, or molecules that enable immune evasion, such as CD47 [

10]. Finally, LSCs have developed special mechanisms of crosstalk with the BMM that promote their survival, proliferation and immune evasion, as further explained in the next section.

The biological properties of LSCs are implemented through several molecular signaling pathways, the targeting of which could have therapeutic implications. Some of these multistep key-signaling pathways are aberrantly exploited by LSCs to promote their survival and clonal expansion, gaining advantage over non-malignant hematopoietic cells in the BM. For instance, the NOTCH signaling pathway, important for tissue development, is active in normal hematopoiesis, but the overexpression of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) can immortalize stem cells in the case of AML [[

13]. Another highly preserved signaling pathway consists of the binding of Wnt with its receptor, which causes the accumulation of b-catenin in the nucleus, where it promotes the expression of genes involved in the proliferation of cells, HSCs included [

8]. Overexpression of b-catenin has been documented in LSCs pointing to a possible key role of this pathway in LSC expansion [

14]. The JAK/STAT pathway also interferes with LSCs biology, since STAT5B has been shown to activate genes associated with quiescence and self-renewal in LSCs [

15]. Data has been rather conflicting regarding the role of the Hedgehog pathway in the pathogenesis of AML, since some studies found that this signaling pathway is not necessary for the maintenance of LSCs, while others support an essential role of the pathway, since overexpression of GLI1, a key-mediator of the Hedgehog pathway, has been associated with worse outcomes and increased chemo-resistance in patients with AML [

8,

16,

17,

18]. Some other signaling pathways seem to be of greater importance in specific AML subtypes. For example, LSCs in t(8;21) AML seem to aberrantly activate the VEGF/IL-5 pathway, which allows them to re-enter the cell cycle and preserve their self-renewal ability, while FoxM1 regulates cellular proliferation specifically in LSCs of

MLL-rearranged AML [

19]. Continuing research reveals many more signaling pathways involved in biological processes of LSCs, including BMI-1, PI3K-AKT, AHR and PDK1, which could provide multiple promising targets for therapeutic interventions [

17].

3. The Role of LSCs and the BMM in Leukemogenesis

In recent years, neoplastic stem cells have been categorized into two types, premalignant (preleukemic) neoplastic stem cells (pre-L-NSCs) and leukemic (malignant) neoplastic stem cells. Myeloid leukemogenesis is facilitated by numerous molecular mechanisms, including modifications in epigenetics, transcription factors, signal transduction, DNA damage control, cell cycling and the BMM. This process involves the acquisition of somatic mutations, clonal selection, interaction with the BM niche, and immune evasion [

20].

3.1. LSCs and Leukemogenesis

AML evolves through a multistep process in which sequential mutations transform normal HSCs into pre-leukemic clones and, ultimately, leukemia-initiating LSCs. Pre-LSC typically generate small clonal populations and retain many functional properties of normal HSCs, whereas fully transformed LSCs possess the capacity to initiate and sustain overt leukemia [

21]. Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) refers to the age-associated expansion of HSCs harboring somatic mutations in leukemia-associated genes and comprising a pre-leukemic state, the clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) [

22]. Another significant issue was the term of clonal hematopoiesis of oncogenic potential (CHOP), converting a non- or pre-malignant condition into an overt malignancy. The acquisition of one or more CHIP mutations is a prerequisite for the transformation of a normal stem cell into a pre-LSC, while LSCs are frequently characterized by the presence of above two CHIP mutations or one CHOP mutation [

21].

Initiating or "driver" mutations occur in epigenetic modifiers that regulate cytosine methylation, such as

DNMT3A (DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha),

IDH 1/2 (isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2), TET2 (tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2) and histone modification, such as

ASXL1 (additional sex combs-like) and

EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2). Afterwards, additional somatic mutations are necessary to promote proliferation, as preleukemic and late events, like

NPM1 (nucleophosmin 1),

FLT3-ITD (internal tandem duplication of the gene

FLT3),

KRAS/

NRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog/neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) and

CEBPA (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha) driving pre-LSCs into full LSCs (

Figure 1) [

3,

16,

23]. LSCs generate leukemic blasts possessing leukemia-associated mutations and exhibit a blockade in differentiation. In contrast, pre-LSCs carry recurrent pre-leukemic mutations but retain their ability to differentiate and mature, producing functional progenitor cells that also harbour these mutations [

3,

22].

3.2. BM Niche and Leukemogenesis

The BM is a complex hematopoietic organ comprising a dynamic microenvironment of heterogeneous cellular populations, vascular and neural networks, and non-cellular components organized into functional niches [

24]. The BM niche is the specialized microenvironment that supports HSCs and regulates self-renewal, differentiation, and proliferation to maintain hematopoietic homeostasis [

25].HSCs reside in a specialized, physiologically hypoxic milieu where their quiescence and undifferentiated state are preserved through direct cell–cell contacts and soluble factor-mediated interactions within BMM. Based on anatomical localization, BM niches are commonly categorized into the endosteal (osteoblastic) niche, located adjacent to the endosteum, and the vascular niche, associated with blood vessels and the surrounding perivascular matrix. The BMM includes stromal and immune populations (T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells), as well as osteoblasts, adipocytes, perivascular mesenchymal stem/stromal cells, endothelial cells, and neural elements [

26,

27]. Non-cellular components, including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix constituents, are also essential for controlling hematopoiesis and sustaining stem cell homeostasis. The endosteal niche has been linked to HSC maintenance and quiescence, whereas the vascular niche contributes to trafficking and release of more mature hematopoietic precursors into the circulation [

27].

In AML, a complex bidirectional interaction develops between LSCs and the BM stromal niche, supporting both disease initiation and progression. LSCs actively remodel the healthy niche, creating a permissive microenvironment that promotes leukemic dominance, expansion, and protection from cytotoxic chemotherapy [

28]. Reported AML-associated alterations of the BMM include (i) increased pro-angiogenic signaling and angiogenesis; (ii) lipolysis and reduction of BM adipose tissue; (iii) neuropathic changes involving the sympathetic nervous system; (iv) dysregulation of cytokine and chemokine networks, accompanied by upregulation of adhesion molecules that activate pro-survival signaling pathways; (v) adaptation to hypoxic conditions with suppression of endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) production; (vi) reprogramming of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to support leukemic proliferation; and (vii) escape from immune surveillance, including through immune checkpoint dysregulation [

24,

29]. A deeper mechanistic understanding of this leukemia–niche interplay may enable the development of strategies that disrupt microenvironmental protection and overcome therapy resistance in AML [

24,

29].

4. Immunophenotypic Identification of LSCs

Multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) enables immunophenotypic identification of LSC-enriched populations in AML using fluorochrome-labelled antibody panels that target defined surface antigen patterns. Most clinical and translational data derive from CD34-positive AML where LSCs are enriched within the CD34⁺CD38⁻ compartment. Because this gate is shared with normal HSCs, the practical challenge is not enrichment alone but discriminating leukemic CD34⁺CD38⁻ events from normal HSCs using aberrant or LSC-associated markers. A pragmatic approach is to first define the CD34⁺CD38⁻ compartment and then identify leukemic events using LSC-associated markers and lineage aberrancies. Zeijlemaker et al. developed and validated a single 8-color tube for efficient quantification of CD34⁺CD38⁻ LSCs at diagnosis and during follow-up. This panel combines backbone markers (CD45, CD34, CD38) with LSC-associated markers (CD45RA, CD123, CD33, CD44) and a cocktail of additional aberrancy markers, including CLL-1, TIM-3, CD7, CD11b, CD22, and CD56, within a single fluorescence channel. This design facilitates broad applicability while preserving analytical feasibility in routine laboratory workflows [

30,

31].

For more accurate identification and discrimination of LSCs from HSCs, additional markers frequently used across studies include CD123 (IL-3Rα), CD44, CD33, CLL-1 (CLEC12A/CD371), TIM-3 (CD366), CD45RA, CD96, IL1RAP, and CD200. Crucially, distinguishing LSCs from normal HSCs becomes challenging in regenerating BM (e.g., post-chemotherapy) where normal HSCs expand. In this context, CD90 (Thy-1) serves as a vital negative selection marker, as regenerating HSCs are strictly CD90-positive, whereas LSCs in most AML cases are CD90-negative. LSC-enriched compartments may also show aberrant expression of lineage-associated antigens such as CD7, CD11b, CD22, CD56, and occasionally CD19, which can be leveraged as "different-from-normal" signals to distinguish leukemic stem-like populations from normal HSCs.

Table 1 summarizes key markers reported on LSCs and HSCs [

32,

33,

34].

MRD refers to residual leukemic cells detectable below the morphological threshold of 5% blasts by conventional cytomorphology after initial therapy. MRD positivity is a strong prognostic biomarker, associated with increased relapse risk and inferior OS and disease-free survival (DFS) and it is increasingly incorporated as an efficacy-response endpoint in therapeutic development [

35]. Common MRD methodologies include MFC, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays targeting recurrent gene fusions or specific genomic alterations, and NGS, each offering distinct sensitivity and specificity profiles [

36]. According to ELN recommendations since 2017, two core strategies underpin MFC-based MRD assessment: the leukemia-associated immunophenotype (LAIP) approach and the different-from-normal (DfN) approach. These frameworks improve monitoring accuracy and support standardized reporting, with MRD positivity commonly defined at a threshold of 10⁻⁴ or higher [

37,

38]. Incorporating LSC-directed MFC assays may further enhance sensitivity and predictive accuracy by focusing on therapy-resistant subpopulations enriched for relapse-initiating capacity. ELN recommendations also highlight the prognostic significance of LSC quantification, typically defined immunophenotypically as CD34⁺CD38⁻ cells co-expressing aberrant markers not usually present on normal HSCs, such as CD45RA (PTPRC), CLL-1 (CLEC12A), or CD123 (IL3RA) [

37].

Within this framework, MRD quantifies residual leukemia burden, whereas LSC-enriched readouts provide complementary information on stemness-associated persistence and relapse biology. Combining MFC-based MRD with LSC-oriented phenotyping may therefore improve risk stratification, therapeutic monitoring, and relapse prediction beyond conventional MRD approaches alone [

35,

36]. In practice, an LSC-enriched MFC readout is best interpreted as an adjunct to MRD rather than a standalone substitute for established methodologies and is particularly valuable when it identifies a persistent CD34⁺CD38⁻ aberrant compartment despite apparent cytoreduction. Recent standardization efforts by the HOVON group emphasize the technical stringency required for LSC detection. Reuvekamp et al. demonstrated that assessing at least 1 million (and ideally up to 4 million) events is requisite for high-sensitivity LSC-MRD monitoring. Furthermore, they highlighted that combining LSC assessment with conventional MRD significantly refines risk stratification, with double-negative patients (MRD-/LSC-) achieving superior 3-year survival rates (80%) compared to double-positive cases (45%), thereby validating the clinical utility of the dual-assay approach [

39].

5. The Contribution of LSCs in Relapse and AML Progression

The emergence of relapse in the management of AML remains challenging. LSCs are responsible for the re-initiation of leukemic events, and developing more effective therapies to eliminate LSCs remains a critical unmet need. Relapse occurs when residual leukemic cells, comprising a subclone of blasts and quiescent LSCs, either evade initial treatment or remain undetected at diagnosis. The surviving LSCs adapt by undergoing phenotypic changes and acquiring additional somatic mutations, contributing to disease recurrence. Because of the unique biological characteristics and mechanisms of LSCs the conventional chemotherapy, which mainly targets rapidly proliferating leukemic blasts, often fails to completely eliminate the LSC population and leads to MRD positivity [

3].

The resistance mechanisms of LSCs are complex and involve multiple pathways. The majority of LSCs has the capacity to enter in a quiescence or dormancy state (G0), allowing them to escape the killing effects of cytotoxic agents, such as cytarabine and anthracyclines, that primarily target rapidly dividing cells. The efflux pump activity, ABC transporters (P-gp, BCRP, MRP1), is overexpressed in LSCs expelling chemotherapeutic agents and protecting them from the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy. Furthermore, LSCs exploit the BMM, remodeling the endosteal niches to survive and protect themselves from the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy. The upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g. BCL-2, MCL-1) contributes significantly to apoptosis resistance and survival of LSCs. Chemotherapeutic drugs induce DNA damage, driving cells to premature senescence, but several studies revealed that LSCs demonstrate senescent resistance and DNA repair mechanisms compared to HSCs. Hence, LSCs exhibit metabolic flexibility, depending more on OXPHOS than on aerobic glycolysis, which generates ATP using amino acids, fatty acids, and glucose as energy substrates. Because of this metabolic plasticity, the LSCs survive even in hypoxic or nutrient-poor environments such as the BM niche. Recently increasing studies have revealed that, LSCs can evade the immune surveillance by altering immune compartments and upregulating immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1) and CD47 [

40,

41,

42].

Consequently, the improvement in our understanding of LSC biology, gene expression profile, and phenotype resulted in novel therapeutic options aiming to eradicate LSCs in the BM.

6. LSCs in Other Hematological Malignancies

The role of LSCs in other haematological malignancies has also been studied by several research groups, albeit not as extensively as in the case of AML. Herein we discuss the examples of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and multiple myeloma (MM).

In CML LSCs are believed to be responsible both for disease initiation as well as resistance to therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and for the evasion and progression of the disease. This is based not only on general characteristics of LSCs as those seen in AML (such as extrinsic support from the niche microenvironment or aberrant activation of signaling pathways), but also on other disease-specific mechanisms [

43]. The chimeric BCR-ABL gene and its product are believed to disrupt several cellular processes, including cell signaling, autophagy, metabolism and apoptosis, thus resulting in LSCs survival and self-renewal. For instance, the BCR-ABL chimeric protein can promote the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins of the BCL2 family or increase aerobic glycolysis of LSCs by activating the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, hence supporting LSCs survival and stemness [

43,

44,

45]. Additionally, LSCs in CML have developed several mechanisms that allow them to overcome the effects of TKIs, some of which involve deregulated miRNA expression. Indeed, increased levels of miR-126 and miR-29a or the downregulation of the tumour suppressor miR-142 are believed to cause or enhance TKI resistance [

46,

47,

48]. Finally, LSCs have been investigated as a potential therapeutic target in CML with several agents apart from TKIs. Indeed, pharmaceutical suppression of autophagy, targeting of LSCs surface markers and inhibition of signaling pathways have been proposed as potential ways to eliminate LSCs in CML and, thus, overcome first-line treatment resistance [

43].

ALL generally shows greater heterogeneity, and a less strict hierarchical organization compared to AML [

8]. Actually, there is still uncertainty whether ALL arises from the malignant transformation of normal HSCs or from more mature lymphoid committed progenitors that have regained their stem cell properties [

49]. This is because it was originally believed that proliferation and engraftment to murine models was a capacity restricted to CD34+/CD19- immature cells, but it was later shown that stem cell properties can be found in B-ALL leukemic blasts at different maturation stages (CD19- or CD19+) [

50,

51]. Even among different genetic subtypes of B-ALL there seems to be high heterogeneity regarding the maturation stage of the cell of origin. For example, it has been demonstrated that ALL with t(12;21) as well as P190 BCR-ABL ALL originate from a committed B-cell progenitor, while p210 BCR-ABL ALL arises from the pool of less mature multipotent HSCs [

52]. Less evidence is available for T-ALL where it was shown that LICs are mainly detected in the CD7+/CD1a- subset [

53]. In any case, further research about LSCs in ALL is warranted to assess their role in disease relapse, treatment resistance or even as a therapeutic target, similarly to AML.

In case of MM, the characterization of cancer stem cells (CSCs) has been rather challenging. Theoretically, multiple myeloma stem cells (MMSCs) are described as cells with the capacity to self-renew and differentiate into the neoplastic myeloma plasma cell lineages, also exhibiting drug resistance [

54]. However, data regarding the laboratory identification and phenotypical characterization of these MMSCs has been conflicting. About two decades ago, circulating B-lymphocytes which are clonally related to neoplastic plasma cells (clonotypic B-cells) were identified in patients with MM and it was suggested that they represent CSCs, since they are able to self-renew and initiate MM in murine models, although they comprise a committed cell population without the multipotent differentiation capacity that typically characterizes stem cells. Although initially identified as CD19+CD138- (pre-PC) B-cells, later evidence indicated that CD138+ (plasmablasts/PC) also maintain tumor -initiating capacity [

54,

55,

56].Several other markers, such as CD123, aldehyde dehydrogenase and TRIMM44 have been investigated as possible identifiers of MMSCs, without consensus on a conclusive specific phenotype, suggesting that the MMSC population is phenotypically variable and heterogenous, maybe depending on the genomic events that led to tumorigenesis [

57]. Interestingly, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) which generate the stromal cellular compartment (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, endothelial cells) of the BMM have been reported to show differences in patients with MM compared to healthy individuals, such as lower proliferative capacity and abnormal cytokines expression. These MSCs in the case of MM may form a favorable microenvironment for neoplastic cells which promotes myeloma development and progression and are, hence, suggested as therapeutic targets but also as potential carriers of anti-tumor drugs against the actual myeloma plasma cells, due to their close cross-talk [

58].

7. Prognostic and Predictive Implications of LSCs in AML

Soon after the discovery of the pathophysiologic role of LSCs in terms of AML treatment resistance and relapse, efforts have been made to investigate the potential prognostic and predictive utility of these cells in clinical practice.

For more than a decade, it has been known that among patients with CD34+ AML treated with intensive chemotherapy, the load of CD34+CD38- LSCs at diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor in terms of relapse free survival (RLS) and OS [

31,

59]. LSCs also showed prognostic capacity during the follow-up period, since patients in complete remission (CR) after one or two treatment cycles with a higher percentage of neoplastic CD34+CD38- LSCs had shorter survival compared to those with a lower LSCs percentage. Furthermore, among MRD-negative patients, those with higher LSCs had worse outcomes compared to patients with lower LSCs, implying that MRD status and LSCs percentage possibly have complementary prognostic value in AML [

59,

60].Similarly, it was later confirmed that patients in morphologic CR have a dismal prognosis if they remain both MRD+ and LSCs+ and they should be treated as high-risk patients, regardless of their initial risk assessment according to traditional criteria [

31].However, in patients older than 60 years treated with HMAs, the percentage of LSCs (defined as CD34+CD38-CD123+) at diagnosis does not seem to impact prognosis, although relevant data among those treated with HMAs plus venetoclax, the current standard of care for non-fit patients, are lacking [

61].

Apart from the presence of LSCs as a prognostic biomarker, researchers have also investigated the role of these cells’ immunophenotypic markers in affecting patients’ prognosis. Darwish et al. found that the overexpression of LSC markers TIM-3, BMI-1 and CLL-1 in patients with AML, is correlated with shorter survival, with the limitation that these markers are not exclusively expressed only by LSCs [

62]. Accordingly, patients with AML treated with intensive protocols were found to have shorter 3-year OS (18.2%) if they express at least 2 of the LSC markers CD25, CD96 and CD123, compared to patients with single or no expression of these markers (3-year OS 65%) and multivariate analysis confirmed the independent negative prognostic effect of multiple LSC marker expression [

63].

Additionally, patients with high expression levels of TIM3 on CD34+CD38- LSCs at diagnosis are expected to have lower response rates to induction chemotherapy and worse OS, compared to those with lower levels, pointing to TIM3+ LSCs as a potential prognostic and predictive biomarker [

64]. Recently Huang et al. developed a risk prognostic model for patients with AML based on gene expression profiling in samples with high or low TIM3 expression, using weighted gene co-expression network analysis [

65].

In routine practice, LSC-oriented MFC is most informative when measured at diagnosis (to define the aberrant stem-like phenotype) and at response timepoints (post-induction/CR assessment and pre-transplant) to identify persistence of an aberrant CD34⁺CD38⁻ compartment. Persistently detectable LSC-enriched populations—especially when discordant with bulk MRD—should prompt closer monitoring and may support treatment intensification or trial enrolment in otherwise borderline-risk scenarios.

8. Therapeutic Targeting of LSCs in AML

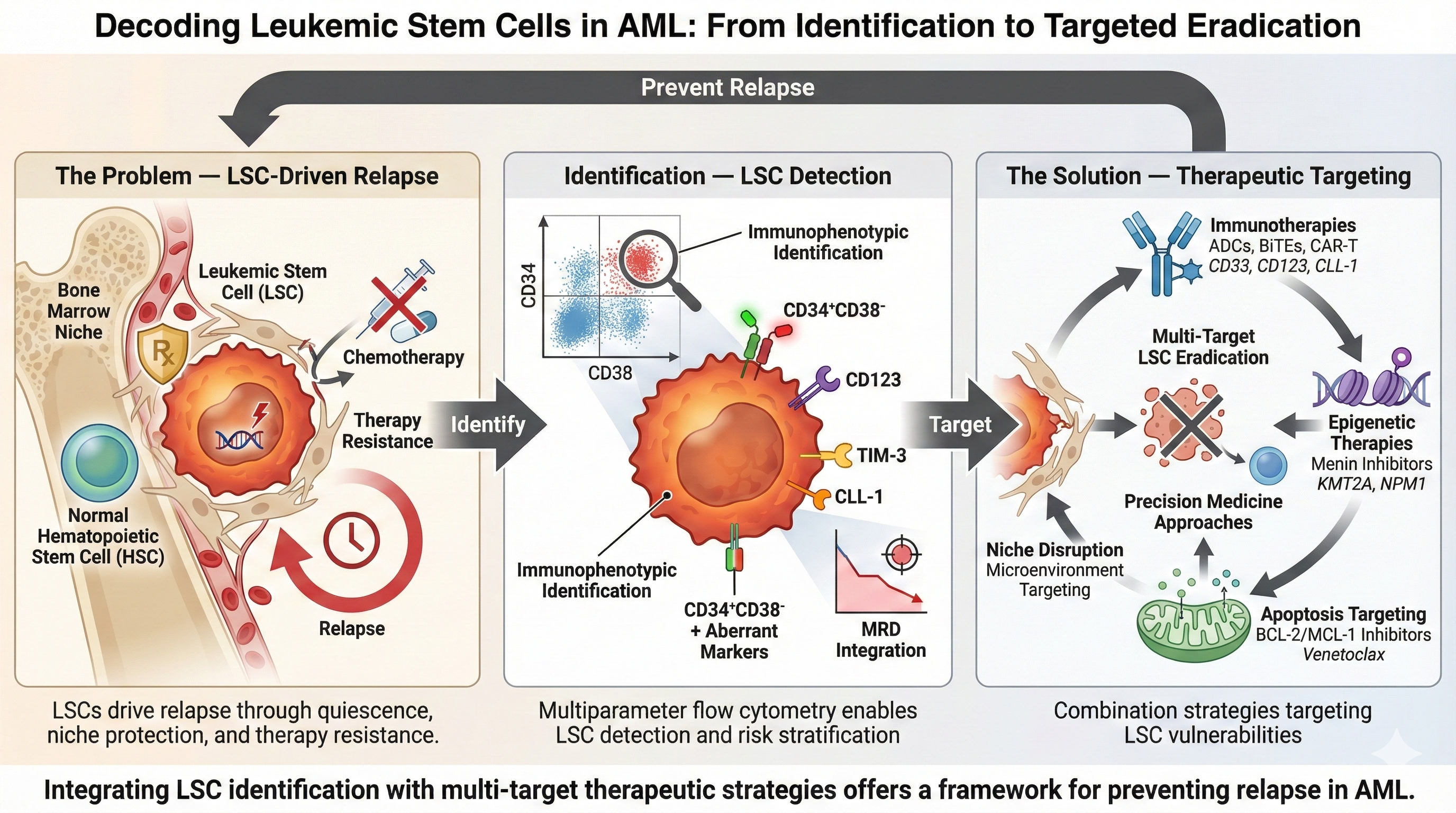

Therapeutic strategies targeting LSCs in AML are of particular interest because LSCs are implicated in chemotherapy resistance, persistence of disease, and relapse. Accordingly, LSC-directed therapy aims not only to reduce bulk blast burden but also to disrupt relapse-initiating programs and improve the depth and durability of remission. In the era of precision medicine, multiple targeted approaches are under investigation in preclinical and clinical studies, including immunotherapies, epigenetic modulators, and inhibitors of key survival and DNA repair pathways (

Figure 2).

8.1. Immunotherapies

Immunotherapeutic strategies in AML aim to eliminate therapy-resistant compartments, including LSC-enriched populations, by engaging immune effector mechanisms against leukemia-associated surface antigens such as CD33, CD123, CD47, CD70, and TIM-3 [

66,

67]. Current approaches include antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), unconjugated monoclonal antibodies, bispecific T-cell–engaging antibodies, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and cellular therapies. A central translational constraint is that many AML-relevant antigens are also expressed on normal myeloid progenitors, narrowing the therapeutic window and necessitating careful target selection and toxicity monitoring.

8.1.1. Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

ADCs deliver cytotoxic payloads to antigen-expressing leukemic cells. Examples include gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), a humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody (moAb) conjugated with calicheamicin and tagraxofusp which targets CD123 and is fused to diphtheria toxin [

67,

68]. Although these agents can induce meaningful responses, their capacity to eradicate LSC may be limited by antigen heterogeneity and by dose-limiting myelosuppression due to overlap with normal progenitor expression.

8.1.2. Unconjugated Monoclonal Antibodies

Unconjugated moAbs bind leukemia-associated antigens and mediate antibody-dependent cellular/complement-dependent cytotoxicity or induce apoptosis [

67]. Agents under clinical evaluation include lintuzumab (a humanized IgG1 anti-CD33), cusatuzumab (an anti-CD70) and talacotuzumab (a second generation anti-CD123) either as monotherapy or in combination regimens [

66].

8.1.3. Bispecific Antibodies/BiTEs

Bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) recruit T cells via CD3 and redirect them to leukemic targets such as CD33 or CD123 [

69]. Flotetuzumab (CD123/CD3) has shown activity in early-phase trials in adults with relapsed/refractory AML, while other investigational bispecifics include AMG 330 (CD33/CD3), and APVO436 (CD123/CD3) agent [

70]. Beyond antigen expression, the depth and durability of response may be constrained by baseline T-cell dysfunction, an immunosuppressive marrow microenvironment, and treatment-related cytopenias.

ICIs targeting TIM-3, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and CTLA-4 pathways are being explored in AML, most commonly in combination strategies (e.g., with epigenetic modifiers) in relapsed/refractory disease and in older/unfit AML or MDS cohorts [

67,

71]. Agents under investigation include nivolumab, pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitors) and durvalumab (PD-L1 inhibitors) [

67,

71].

The role of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in AML is investigated under several clinical trials, primarily enriched on LSCs such as CD33, CD123, CLL-1 with encouraging results but also notable challenges related to antigen overlap, toxicity, and disease heterogeneity. Additional targets under preclinical evaluation include myeloid markers (e.g., CD38, CD13, CD64) and NK-related targets (e.g., NKG2D, CD70) [

71,

72].Key barriers include antigen overlap with normal progenitors (risk of prolonged aplasia), antigen heterogeneity/escape, and logistical challenges in rapidly progressive disease.

Across immunotherapy platforms, several barriers limit clinical efficacy: antigen heterogeneity within the LSC compartment, on-target/off-tumor myelotoxicity due to shared antigen expression on normal hematopoietic progenitors, and microenvironmental protection that shields LSCs from immune-mediated killing. These factors directly impact trial design, dosing strategies, and the rationale for combination approaches.

8.2. Epigenetic Modifiers

While immunotherapies aim to eliminate LSCs via antigen-directed immune engagement, epigenetic therapies target the transcriptional dependencies that maintain LSC self-renewal and differentiation blockade—dependencies that are often genotype-defined in AML.

8.2.1. Menin Inhibitors

Menin is a scaffold nuclear protein, encoded by the tumour suppressor gene

MEN1 that—despite its tumor suppressor context—acts in AML as a critical cofactor sustaining leukemogenic transcriptional programs through interaction with

KMT2A-associated complexes [

73]. Because

HOXA/MEIS1-driven transcription is closely linked to stemness and self-renewal, menin inhibition is of particular interest as an LSC-directed strategy, aiming to disrupt relapse-initiating circuitry rather than only reducing bulk blasts [

74,

75]. In KMT2A-rearranged AML, menin binding supports maintenance of a

HOXA/MEIS1 program that preserves LSC properties and enforces differentiation arrest.

NPM1-mutated AML exhibits a related

HOX/MEIS1-high expression profile, providing a strong mechanistic rationale for menin targeting in this additional genotype-defined subgroup [

76,

77].

Mechanistically, small-molecule menin inhibitors disrupt the menin–

KMT2A interaction, leading to downregulation of

HOXA9/MEIS1-dependent programs, induction of differentiation, and reduction of LSC-enriched compartments. Clinically, the landscape changed materially in 2024–2025, with revumenib receiving FDA approval first in

KMT2A-rearranged R/R acute leukemia (including pediatric patients) [

78,

79] and later for R/R AML with a susceptible NPM1 mutations with no satisfactory alternatives, followed by FDA approval of ziftomenib for adults with R/R

NPM1-mutated AML [

80]. As a class, menin inhibitors require attention to differentiation syndrome and electrocardiographic monitoring considerations (e.g., QTc-related precautions), which has practical implications for early recognition and management pathways.

Beyond approved agents, several additional menin inhibitors (e.g., enzomenib , bleximenib, DS-1954, BMF-219) are under clinical evaluation as monotherapy and in combinations (e.g., venetoclax-based regimens, FLT3 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, and intensive chemotherapy). Their ultimate positioning will likely depend on durability of response, safety profile, and combinability across molecular subsets, as well as whether deeper stemness suppression translates into sustained MRD negativity and relapse prevention [

81,

82,

83].

8.2.2. DOT1L Inhibitors

The histone lysine methyltransferase DOT1L (Disruptor of Telomeric Silencing 1-Like) is an epigenetic regulator implicated in AML with

KMT2A rearrangements and other malignancies. Pinometostat is a first-in-class, selective, intravenously DOT1L inhibitor that demonstrated activity in early-phase clinical trials; however responses as monotherapy have been limited supporting ongoing evaluation of combination strategies [

84,

85].

8.3. Targeting Apoptosis Pathways

The intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway of apoptosis is regulated by the BCL-2 proteins family, which includes the pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak, Bim, Bid) and the anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL-2, MCL-1, BCL-W, BCL-XL) [

86]. In AML, LSCs frequently exhibit heightened dependence on anti-apoptotic programs, particularly BCL-2 and MCL-1, thereby contributing to chemoresistance and persistence of MRD.

Venetoclax, a BH3 mimetic, inhibits BCL-2 and can target LSC compartments that depend on BCL-2 and OXPHOS for survival [

86,

87]. However, despite the promising efficacy of venetoclax-based combination regimens in AML, resistance mechanisms-most commonly the upregulation of other anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 or BCL-XL- limit the durability of responses [

88]. This has driven interest in the development of MCL-1 inhibitors (e.g., S64315/MIK665, AMG 176 [tapotoclax], AZD5991), which have demonstrated preclinical activity against blasts and LSCs, although cardiotoxicity has emerged as a major limitation in clinical development [

86].

8.4. DNA Damage Response Targeting: PARP Inhibitors

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes, particularly PARP1 and PARP2, catalyze the addition of polymerized ADP-ribose onto substrates, thereby modifying their function or stability, and playing a central role in DNA damage repair. PARP inhibitors such as olaparib or talazoparib exploit compromised DNA repair mechanisms in cancer cells and demonstrate synergistic activity when combined with DNA-damaging agents, including anthracyclines and topoisomerase inhibitors. In AML, however, PARP inhibitors remain in early-stage clinical development, and definitive efficacy data are not yet available [

87].

9. Why Promising Targets Fail in AML

Despite compelling preclinical rationale and encouraging early-phase signals, many LSC-directed targets and immunotherapy platforms have not translated into durable clinical benefit in AML. Failures typically reflect a convergence of biological, microenvironmental, and clinical-trial constraints that are particularly pronounced in myeloid disease.

Absence of an “ideal” AML-specific antigen: on-target/off-tumor toxicity. The most significant barrier for antibody-based and cellular therapies in AML is the lack of a surface antigen uniformly expressed on blasts and LSCs but absent from normal hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Commonly targeted antigens—CD33, CD123, and CLL-1—are also expressed on normal myeloid progenitors, creating inherent risk for prolonged myeloablation, severe cytopenias, and infectious complications when potent targeting is achieved. This shared-antigen problem represents the central limitation for CAR-based approaches in AML and explains the tight coupling between efficacy and toxicity in this disease [

89,

90].

Antigen heterogeneity and antigen-negative escape: AML is biologically heterogeneous both across patients and within individual patients, characterized by dynamic subclonal evolution and variable antigen density. Single-antigen targeting strategies are therefore vulnerable to antigen-low subpopulations and antigen-negative relapse, particularly under therapeutic selective pressure. This limitation is well recognized in the CAR-T AML literature and has been specifically documented in the context of CD123-directed immunotherapies [

91].

LSC plasticity and clonal evolution under therapy: A key reason that promising therapeutic targets fail to deliver durable responses is that the LSC state is not static. LSCs can alter their phenotype and transcriptional programs in response to treatment, and relapse frequently reflects selection of resistant subclones rather than regrowth of the original dominant population. Current LSC-focused research highlights that stemness traits are shaped by both global and subtype-specific features, and that this heterogeneity fundamentally limits the effectiveness of single-pathway or single-marker targeting strategies [

92].

An immunosuppressive BMM: The BMM in AML undermines immune effector function through multiple mechanisms, including dysfunctional antigen presentation, suppressive myeloid populations, inhibitory cytokines, and metabolic constraints. Baseline T-cell dysfunction and the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment are increasingly recognized as key factors contributing to the limited and variable clinical activity observed with AML immunotherapies, including CD123-directed approaches [

91,

93].

High-risk disease biology can overwhelm single-agent promise (example: TP53-mutated AML): Clinical failures are often most evident in genomically adverse disease, where aggressive biology and profound treatment resistance limit the ability of any single mechanism to meaningfully improve survival. The phase 3 ENHANCE-2 trial of magrolimab plus azacitidine in previously untreated TP53-mutated AML provides a recent example: despite encouraging signals from non-randomized studies, the combination failed to improve OS compared with physician's choice [

94].

Trial-design and implementation constraints in AML: Even effective modalities face significant practical barriers in AML: patients may deteriorate rapidly, have active infections, or carry substantial prior-treatment burdens that compromise immune function and organ reserve. For cellular therapies, logistical challenges including manufacturing time, bridging therapy requirements, and toxicity management, combined with the need to avoid prolonged aplasia, can limit feasibility and confound outcome interpretation. These factors represent core obstacles to the broad applicability of CAR-based approaches in AML.

10. Discussion

AML remains a major clinical challenge, in large part because LSCs can persist despite therapy and re-initiate disease after apparent remission [

95,

96]. LSCs are rare but highly resilient, characterized by phenotypic and functional heterogeneity, quiescence, metabolic plasticity, and multiple mechanisms of treatment resistance—features that contribute to chemoresistance, MRD persistence, and ultimately relapse [

97]. Although therapeutic options have expanded substantially with the introduction of targeted agents and novel combinations, outcomes remain suboptimal, particularly in older or medically unfit patients. These observations underscore an unmet need for a more integrated understanding of AML biology that links LSC properties to clinically actionable biomarkers and rational therapeutic strategies.

The most important challenge regarding the practical utility of LSCs is the phenotypic resemblance between LSCs and normal HSCs which complicates the accurate distinction and identification [

39]. However, MFC is a significant tool in clinical routine, enabling the identification of LSCs through aberrant immunophenotypes, including LSCs specific markers such as CD34⁺CD38⁻, CD123, TIM-3, CLL-1, and CD96 [

30]. Incorporating these markers into MFC-based MRD assessments has enhanced risk stratification and early detection of relapse [

98].

Our review highlights three critical clinical scenarios that arise from this dual-monitoring approach (

Figure 3).

The Discordant "Hidden Risk" (MRD⁻/LSC⁺): Patients who achieve morphological and MRD-negative status but retain a detectable LSC compartment face significantly shorter survival [

30,

60]. Canali et al. identified this group as comprising 25.8% of their cohort, with a 3-year OS of only 52% compared to 88% in double-negative patients [

60]. In these cases, LSCs act as a "reservoir" for future clones, implying that MRD negativity alone may be insufficient to declare a durable remission [

36,

99].

The Ultra-High Risk (MRD⁺/LSC⁺): The persistence of both bulk blasts and a stem-like compartment indicate profound treatment resistance. Zeijlemaker et al. demonstrated that these patients have a hazard ratio of 3.62 for OS and 5.89 for cumulative incidence of relapse, with nearly 100% treatment failure probability [

30]. These patients should be considered for immediate treatment intensification or stem cell transplantation (SCT), regardless of their initial ELN risk category.

The Low-Risk Transition (MRD⁻/LSC⁻): This status represents the optimal therapeutic goal: a "deep" remission where the relapse-initiating programs have been effectively eradicated [

30,

60].

Biologically, LSCs exhibit several survival strategies that render them refractory to standard chemotherapy and responsible for disease relapses [

40,

42]. Their quiescent nature allows them to evade cell cycle-specific agents like cytarabine and anthracyclines [

100,

101]. Elevated efflux pump activity, particularly through ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as ABCG2 and P-glycoprotein (MDR1), reduces intracellular drug accumulation. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins like BCL-2, MCL-1, and surviving further fortifies LSCs against apoptosis [

97]. Additionally, enhanced DNA repair mechanisms [

40,

42] and a reliance on OXPHOS over glycolysis endow LSCs with superior metabolic resilience [

11,

12]. Their localization within protective bone marrow niches, which offer anti-apoptotic and immune-privileged signals [

24,

28], and the expression of immune evasion molecules such as PD-L1 and CD47 [

40,

42], further contribute to their long-term survival and escape from both therapy and immune surveillance.

These unique features of LSCs have stimulated the development of novel targeted therapies aimed at their selective eradication, while allowing normal HSCs survival. Epigenetic regulators have emerged as critical targets: menin inhibitors, such as revumenib and ziftomenib, disrupt the oncogenic MLL-fusion/menin interaction, downregulating HOXA9 and MEIS1 and impairing LSC self-renewal in

MLL-rearranged and

NPM1-mutated AML [

75,

76,

77], while DOT1L inhibitors like pinometostat block H3K79 methylation, further suppressing leukemogenic gene expression in MLL-rearranged AML [

84,

85]. Immunotherapeutic approaches offer complementary strategies for LSC elimination. Unconjugated monoclonal antibodies targeting antigens such as CD33 (lintuzumab), CD123 (talacotuzumab), and CLL-1 have shown activity in early-phase trials [

66,

67]. ADCs, such as gemtuzumab ozogamicin (anti-CD33) and pivekimab sunirine (IMGN632; anti-CD123), deliver cytotoxic agents directly to leukemic cells, enhancing efficacy while limiting systemic toxicity [

67]. Bispecific antibodies, such as flotetuzumab (CD123/CD3), recruit T cells to eliminate LSCs, representing a novel immunotherapeutic approach in AML treatments [

68,

69]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CD47 are under investigation to reverse LSC-mediated immune escape and reinvigorate anti-leukemic immunity [

67,

71]. CAR T cell therapies directed against LSC-associated antigens such as CD33, CD123, and CLL-1 are also being explored, though challenges remain regarding on-target, off-tumor toxicity and antigen escape [

72,

89,

90,

91]. Further refinement of CAR-T cell constructs and targeting strategies is essential for their safe and effective implementation in AML. Targeting metabolic and survival mechanisms of LSC has increasingly become a focus of research. BCL-2 inhibitors such as venetoclax disrupt the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, preferentially affecting LSCs due to their dependency on BCL-2 proteins [

86,

87]. However, resistance due to upregulation of MCL-1 is a frequent occurrence, prompting the development of selective MCL-1 inhibitors (e.g., S64315, AZD5991) to overcome resistance and act synergistically with venetoclax [

86,

88]. PARP inhibitors are being evaluated for their potential to exploit DNA repair vulnerabilities in LSCs, particularly in cases with defective homologous recombination repair [

87].

Despite these advances, several unmet needs persist. LSCs continue to evade current treatments through their adaptability, microenvironmental protection, and phenotypic plasticity. There is a critical need for biomarkers to dynamically track LSC burden, guide therapy, and early predict relapse. Furthermore, most novel agents remain in early-phase trials, and their long-term efficacy and safety remain to be fully established. Integrating multi-omic approaches, real-time single-cell analyses, and functional assays, probably with the use of artificial intelligence, will be key to unveiling the evolving LSC landscape and informing precision medicine strategies.

11. Conclusions

In conclusion, while the identification and targeting of LSCs have progressed significantly, achieving their complete eradication to minimize the risk of clinical relapse remains the "Holy Grail" of AML therapy. standardized LSC-enriched MFC panels for dynamic risk stratification, metabolic targeting, immunotherapy, and epigenetic modulation holds the greatest promise for transforming treatment outcomes. By bridging bench biology and clinical decision-making through continued translational research and innovative trial designs, we can shift from simply treating disease to preventing relapse at its source.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.; methodology, E.A. and V.G; writing—original draft preparation, E.A. and V.G; review and editing, L.B., E.K. and E.H.; visualization E.H.; supervision, E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT 5.1 and Claude Opus 4.5 exclusively for language refinement and grammatical editing and Gemini 3 for the graphical abstract illustration and figure generation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Găman, M.-A.; Zou, Z. The genesis and evolution of acute myeloid leukemia stem cells in the microenvironment: From biology to therapeutic targeting. Cell Death Discovery 2022, 8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urs, A.P.; Goda, C.; Kulkarni, R. Remodeling of the bone marrow microenvironment during acute myeloid leukemia progression. Ann Transl Med 2024, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelmach, P.; Trumpp, A. Leukemic stem cells and therapy resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2023, 108, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapidot, T.; Sirard, C.; Vormoor, J.; Murdoch, B.; Hoang, T.; Caceres-Cortes, J.; Minden, M.; Paterson, B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Dick, J.E. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994, 367, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nature Medicine 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I.V.; Pessoa, F.M.C.d.P.; Machado, C.B.; Pantoja, L.d.C.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Lopes, G.S.; Amaral de Moraes, M.E.; de Moraes Filho, M.O.; de Souza, L.E.B.; Burbano, R.M.R.; et al. Leukemic Stem Cell: A Mini-Review on Clinical Perspectives. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.-Y. Human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells: evolution of concept. BR 2022, 57, S67–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Q.; Bachas, C.; Smit, L.; Cloos, J. Characteristics of leukemic stem cells in acute leukemia and potential targeted therapies for their specific eradication. Cancer Drug Resistance 2022, 5, 344–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzio, A.; Passegué, E.; Ayton, P.M.; Karsunky, H.; Cleary, M.L.; Weissman, I.L. Similar MLL-associated leukemias arising from self-renewing stem cells and short-lived myeloid progenitors. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 3029–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, I.; Mondala, P.K.; Steel, S.K.; Balaian, L.; Ladel, L.; Mason, C.N.; Diep, R.H.; Pham, J.; Cloos, J.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; et al. Detection and targeting of splicing deregulation in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell Reports Medicine 2023, 4, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.B.; Nemkov, T.; D'Alessandro, A.; Welner, R.S. Deciphering Metabolic Adaptability of Leukemic Stem Cells. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 846149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattigan, K.M.; Zarou, M.M.; Helgason, G.V. Metabolism in stem cell–driven leukemia: parallels between hematopoiesis and immunity. Blood 2023, 141, 2553–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Ghosh, S.; Nath, A.; Basu, A.; Biswas, O.; Patil, C.R.; Kundu, C.N. Theragnostic strategies harnessing the self-renewal pathways of stem-like cells in the acute myeloid leukemia. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2022, 177, 103753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, J.-L. Understanding of leukemic stem cells and their clinical implications. Molecular Cancer 2017, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, S.; Grausenburger, R.; Klampfl, T.; Prchal-Murphy, M.; Bastl, K.; Pisa, H.; Knab, V.M.; Brandstoetter, T.; Doma, E.; Sperr, W.R.; et al. A STAT5B–CD9 axis determines self-renewal in hematopoietic and leukemic stem cells. Blood 2021, 138, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, K.; Zhang, L.; Breslin S.J, P.; Zhang, J. Leukemia Stem Cells in the Pathogenesis, Progression, and Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. In Leukemia Stem Cells in Hematologic Malignancies; Zhang, H., Li, S., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- Azizidoost, S.; Nasrolahi, A.; Sheykhi-Sabzehpoush, M.; Anbiyaiee, A.; Khoshnam, S.E.; Farzaneh, M.; Uddin, S. Signaling pathways governing the behaviors of leukemia stem cells. Genes & Diseases 2024, 11, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, K.C.S.; Ruela-de-Sousa, R.R.; Fuhler, G.M.; Aberson, H.L.; Ferreira, C.V.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Spek, C.A. Hedgehog signaling maintains chemoresistance in myeloid leukemic cells. Oncogene 2010, 29, 6314–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellaway, S.G.; Potluri, S.; Keane, P.; Blair, H.J.; Ames, L.; Worker, A.; Chin, P.S.; Ptasinska, A.; Derevyanko, P.K.; Adamo, A.; et al. Leukemic stem cells activate lineage inappropriate signalling pathways to promote their growth. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouligny, I.M.; Maher, K.R.; Grant, S. Augmenting Venetoclax Activity Through Signal Transduction in AML. J Cell Signal 2023, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Sadovnik, I.; Eisenwort, G.; Bauer, K.; Herrmann, H.; Gleixner, K.V.; Schulenburg, A.; Rabitsch, W.; Sperr, W.R.; Wolf, D. Immunotherapy-Based Targeting and Elimination of Leukemic Stem Cells in AML and CML. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.G.; McLoughlin, M.A.; Vassiliou, G.S. Clonal hematopoiesis and hematological malignancy. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-S.; Kim, B.S.; Yoon, S.; Oh, S.-O.; Lee, D. Leukemic Stem Cells and Hematological Malignancies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, T.; Pinho, S. Leukemic Stem Cells: From Leukemic Niche Biology to Treatment Opportunities. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasian, S.K.; Bornhäuser, M.; Rutella, S. Targeting Leukemia Stem Cells in the Bone Marrow Niche. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantanou, C.; Godavarthy, P.S.; Krause, D.S. Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2018, 59, 2535–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, C.; Caroço, R.; Almeida, A.; Cardoso, B.A. Targeting the bone marrow niche, moving towards leukemia eradication. Frontiers in Hematology 2024, 3–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.A.; Lo Celso, C.; Purton, L.E.; Frisch, B.J. From the niche to malignant hematopoiesis and back: reciprocal interactions between leukemia and the bone marrow microenvironment. JBMR Plus 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, F.; Huang, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, H. Leukemia stem cell-bone marrow microenvironment interplay in acute myeloid leukemia development. Experimental Hematology & Oncology 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeijlemaker, W.; Kelder, A.; Oussoren-Brockhoff, Y.J.; Scholten, W.J.; Snel, A.N.; Veldhuizen, D.; Cloos, J.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Schuurhuis, G.J. A simple one-tube assay for immunophenotypical quantification of leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijlemaker, W.; Grob, T.; Meijer, R.; Hanekamp, D.; Kelder, A.; Carbaat-Ham, J.C.; Oussoren-Brockhoff, Y.J.M.; Snel, A.N.; Veldhuizen, D.; Scholten, W.J.; et al. CD34+CD38− leukemic stem cell frequency to predict outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Panda, D.; Gajendra, S.; Gupta, R.; Thakral, D.; Kaur, G.; Khan, A.; Singh, V.K.; Vemprala, A.; Bakhshi, S.; et al. Immunophenotypic characterization of leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia using single tube 10-colour panel by multiparametric flow cytometry: Deciphering the spectrum, complexity and immunophenotypic heterogeneity. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2024, 46, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuvekamp, T.; Janssen, L.L.G.; Ngai, L.L.; Carbaat-Ham, J.; den Hartog, D.; Scholten, W.J.; Kelder, A.; Hanekamp, D.; Wensink, E.; van Gils, N.; et al. The role of the primitive marker CD133 in CD34-negative acute myeloid leukemia for the detection of leukemia stem cells. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry 2025, 108, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.A.; Bill, M.; Rosenberg, C.A. OMIP 072: A 15-color panel for immunophenotypic identification, quantification, and characterization of leukemic stem cells in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Cytometry Part A 2021, 99, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meddi, E.; Savi, A.; Moretti, F.; Mallegni, F.; Palmieri, R.; Paterno, G.; Buzzatti, E.; Del Principe, M.I.; Buccisano, F.; Venditti, A.; et al. Measurable Residual Disease (MRD) as a Surrogate Efficacy-Response Biomarker in AML. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, M.; Rigolot, L.; Canali, A.; Vergez, F. Minimal Residual Disease in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Old and New Concepts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, M.; Freeman, S.D.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Buccisano, F.; Hourigan, C.S.; Ngai, L.L.; Tettero, J.M.; Bachas, C.; Baer, C.; Béné, M.C.; et al. 2021 Update on MRD in acute myeloid leukemia: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood 2021, 138, 2753–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurhuis, G.J.; Heuser, M.; Freeman, S.; Béné, M.C.; Buccisano, F.; Cloos, J.; Grimwade, D.; Haferlach, T.; Hills, R.K.; Hourigan, C.S.; et al. Minimal/measurable residual disease in AML: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood 2018, 131, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuvekamp, T.; Bachas, C.; Cloos, J. Immunophenotypic features of early haematopoietic and leukaemia stem cells. Int J Lab Hematol 2024, 46, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, G. From Chemotherapy to Targeted Therapy: Unraveling Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Through Genetic and Non-Genetic Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gils, N.; Denkers, F.; Smit, L. Escape From Treatment; the Different Faces of Leukemic Stem Cells and Therapy Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, Volume 11 - 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Peng, D.; Liu, L. Drug Resistance Mechanisms of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, Volume 12 - 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, H.; Yazdanpanah, N.; Rezaei, N. Chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells: targeting therapeutic implications. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Calderon, F.; Gregory, M.A.; Pham-Danis, C.; DeRyckere, D.; Stevens, B.M.; Zaberezhnyy, V.; Hill, A.A.; Gemta, L.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibition in leukemia induces an altered metabolic state sensitive to mitochondrial perturbations. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, F.; Scott, M.T.; Helgason, G.V.; Hopcroft, L.E.; Allan, E.K.; Aspinall-O'Dea, M.; Copland, M.; Pierce, A.; Huntly, B.J.; Whetton, A.D.; et al. The antiproliferative activity of kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia cells is mediated by FOXO transcription factors. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 2324–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Nguyen, L.X.T.; Li, L.; Zhao, D.; Kumar, B.; Wu, H.; Lin, A.; Pellicano, F.; Hopcroft, L.; Su, Y.L.; et al. Bone marrow niche trafficking of miR-126 controls the self-renewal of leukemia stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med 2018, 24, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salati, S.; Salvestrini, V.; Carretta, C.; Genovese, E.; Rontauroli, S.; Zini, R.; Rossi, C.; Ruberti, S.; Bianchi, E.; Barbieri, G.; et al. Deregulated expression of miR-29a-3p, miR-494-3p and miR-660-5p affects sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in CML leukemic stem cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 49451–49469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, Y.; Lee, E.; Chu, H.T.; Yip, P.K.; Gill, H. Targeting Abnormal Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Classical Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, K.M.; Armstrong, S.A. Leukemia stem cells and human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol 2009, 46, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.V.; Evely, R.S.; Oakhill, A.; Pamphilon, D.H.; Goulden, N.J.; Blair, A. Characterization of acute lymphoblastic leukemia progenitor cells. Blood 2004, 104, 2919–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Viseur, C.; Hotfilder, M.; Bomken, S.; Wilson, K.; Röttgers, S.; Schrauder, A.; Rosemann, A.; Irving, J.; Stam, R.W.; Shultz, L.D.; et al. In childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, blasts at different stages of immunophenotypic maturation have stem cell properties. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor, A.; Nilsson, L.; Astrand-Grundström, I.; Buitenhuis, M.; Ramirez, C.; Anderson, K.; Strömbeck, B.; Garwicz, S.; Békássy, A.N.; Schmiegelow, K.; et al. Distinct patterns of hematopoietic stem cell involvement in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med 2005, 11, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.P.L.; Jiang, H.; Dick, J.E. Leukemia-initiating cells in human T-lymphoblastic leukemia exhibit glucocorticoid resistance. Blood 2010, 116, 5268–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.E.; Bøgsted, M.; Schmitz, A.; Bødker, J.S.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Johansen, P.; Valent, P.; Zojer, N.; Van Valckenborgh, E.; Vanderkerken, K.; et al. The myeloma stem cell concept, revisited: from phenomenology to operational terms. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, G.W.; Carrier, E. The search for multiple myeloma stem cells: the long and winding road. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010, 16, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.A.; Matsui, W. Multiple myeloma cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, E.G.; Gunes, M.; Yu, J.; Janakiram, M. Targeting cancer stem cells in multiple myeloma. Trends in Cancer 2024, 10, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; De Veirman, K.; De Becker, A.; Vanderkerken, K.; Van Riet, I. Mesenchymal stem cells in multiple myeloma: a therapeutical tool or target? Leukemia 2018, 32, 1500–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwijn, M.; Zeijlemaker, W.; Kelder, A.; Rutten, A.P.; Snel, A.N.; Scholten, W.J.; Pabst, T.; Verhoef, G.; Löwenberg, B.; Zweegman, S.; et al. Leukemic Stem Cell Frequency: A Strong Biomarker for Clinical Outcome in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canali, A.; Vergnolle, I.; Bertoli, S.; Largeaud, L.; Nicolau, M.L.; Rieu, J.B.; Tavitian, S.; Huguet, F.; Picard, M.; Bories, P.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Unsupervised Early Assessment of Bulk and Leukemic Stem Cell Measurable Residual Disease in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergez, F.; Nicolau-Travers, M.L.; Bertoli, S.; Rieu, J.B.; Tavitian, S.; Bories, P.; Luquet, I.; Mas, V.; Largeaud, L.; Sarry, A.; et al. CD34(+)CD38(-)CD123(+) Leukemic Stem Cell Frequency Predicts Outcome in Older Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Treated by Intensive Chemotherapy but Not Hypomethylating Agents. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, N.H.; Sudha, T.; Godugu, K.; Elbaz, O.; Abdelghaffar, H.A.; Hassan, E.E.; Mousa, S.A. Acute myeloid leukemia stem cell markers in prognosis and targeted therapy: potential impact of BMI-1, TIM-3 and CLL-1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57811–57820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabushita, T.; Satake, H.; Maruoka, H.; Morita, M.; Katoh, D.; Shimomura, Y.; Yoshioka, S.; Morimoto, T.; Ishikawa, T. Expression of multiple leukemic stem cell markers is associated with poor prognosis in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma 2018, 59, 2144–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.M.I.; Aref, S.; Agdar, M.A.; Mabed, M.; El-Sokkary, A.M.A. Leukemic Stem Cell (CD34+/CD38–/TIM3+) Frequency in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Clinical Implications. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia 2021, 21, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, N.; Long, Z. Identification and validation of a prognostic risk-scoring model based on the level of TIM-3 expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 15658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Jing, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Wu, G. Immunotherapies of acute myeloid leukemia: Rationale, clinical evidence and perspective. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 171, 116132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebinama, U.; George, B. Revolutionizing acute myeloid leukemia treatment: a systematic review of immune-based therapies. Discov Oncol 2025, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, A.; Martino, E.A.; Labanca, C.; Mendicino, F.; Lucia, E.; Olivito, V.; Neri, A.; Imovilli, A.; Morabito, F.; Vigna, E.; et al. Tagraxofusp in myeloid malignancies. Hematological Oncology 2024, 42, e3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubicka, E.; Lum, L.G.; Huang, M.; Thakur, A. Bispecific antibody-targeted T-cell therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 899468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, G.L.; Aldoss, I.; Foster, M.C.; Sayre, P.H.; Wieduwilt, M.J.; Advani, A.S.; Godwin, J.E.; Arellano, M.L.; Sweet, K.L.; Emadi, A.; et al. Flotetuzumab as salvage immunotherapy for refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2021, 137, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, D.; Tiribelli, M. Checkpoint Inhibitors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelozzi, I.M.; Kirtsios, E.; Giustacchini, A. Driving CAR T Stem Cell Targeting in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: The Roads to Success. Cancers 2021, 13, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Somervaille, T.C.; Smith, K.S.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Meyerson, M.; Cleary, M.L. The menin tumor suppressor protein is an essential oncogenic cofactor for MLL-associated leukemogenesis. Cell 2005, 123, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argiropoulos, B.; Humphries, R.K. Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6766–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkin, D.; He, S.; Miao, H.; Kempinska, K.; Pollock, J.; Chase, J.; Purohit, T.; Malik, B.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.W.; Song, E.; Feng, Z.; Sinha, A.; Chen, C.W.; Deshpande, A.J.; Cusan, M.; Farnoud, N.; Mupo, A.; Grove, C.; et al. Targeting Chromatin Regulators Inhibits Leukemogenic Gene Expression in NPM1 Mutant Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016, 6, 1166–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, L.; Gundry, M.C.; Sorcini, D.; Guzman, A.G.; Huang, Y.H.; Ramabadran, R.; Gionfriddo, I.; Mezzasoma, F.; Milano, F.; Nabet, B.; et al. Mutant NPM1 Maintains the Leukemic State through HOX Expression. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 499–512 e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (FDA); U.S.F.a.D.A. FDA approves revumenib for relapsed or refractory acute leukemia with a KMT2A. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-revumenib-relapsed-or-refractory-acute-leukemia-kmt2a-translocation (accessed on 27 Dec 2025).

- (FDA); U.S.F.a.D.A. FDA approves revumenib for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with a susceptible NPM1 mutation. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-revumenib-relapsed-or-refractory-acute-myeloid-leukemia-susceptible-npm1-mutation (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Administration; U.S.F.a.D. FDA approves ziftomenib for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with a NPM1 mutation. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ziftomenib-relapsed-or-refractory-acute-myeloid-leukemia-npm1-mutation (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Nadiminti, K.V.G.; Sahasrabudhe, K.D.; Liu, H. Menin inhibitors for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: challenges and opportunities ahead. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2024, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dali, S.A.; Al-Mashdali, A.F.; Kalfah, A.; Mohamed, S.F. Menin Inhibitors in KMT2A-Rearranged and NPM1-Mutated Acute Leukemia: A Scoping Review of Safety and Efficacy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2025, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candoni, A.; Coppola, G. A 2024 Update on Menin Inhibitors. A New Class of Target Agents against KMT2A-Rearranged and NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Hematology Reports 2024, 16, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, E.; Salvati, A.; Pecoraro, G.; Lamberti, J.; Melone, V.; Sellitto, A.; Rizzo, F.; Giurato, G.; Tarallo, R.; Nassa, G.; et al. Histone Methyltransferase DOT1L as a Promising Epigenetic Target for Treatment of Solid Tumors. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, Volume 13 - 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghrajani, K.; Cai, S.F.; Devlin, S.M.; Armstrong, S.A.; Piekarz, R.; Rudek, M.; Tallman, M.S.; Stein, E.M. A Phase Ib/II Study of the Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitor Pinometostat in Combination with Azacitidine in Patients with 11q23-Rearranged Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2019, 134, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, G.O.; Ross, D.M.; Powell, J.A.; Pitson, S.M. Venetoclax therapy and emerging resistance mechanisms in acute myeloid leukaemia. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.A.; Winters, A.C. Emerging and Future Targeted Therapies for Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Targeting the Leukemia Stem Cells. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.H.; Roberts, A.W. BCL2 Inhibition: A New Paradigm for the Treatment of AML and Beyond. Hemasphere 2023, 7, e912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugasti, I.; Espinosa-Aroca, L.; Fidyt, K.; Mulens-Arias, V.; Diaz-Beya, M.; Juan, M.; Urbano-Ispizua, A.; Esteve, J.; Velasco-Hernandez, T.; Menendez, P. CAR-T cell therapy for cancer: current challenges and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldini, B.; Varotto, E. Moving forward in target antigen discovery for immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3088–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyzin, A.; Holtzman, N.G.; Bonifant, C.L. CD123-targeting immunotherapeutic approaches in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2025, 207, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, K.; Deshpande, A.J. Therapeutic targeting of leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1204895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Wang, T.; Wei, J. Strategic innovations: Tackling challenges of immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Chin J Cancer Res 2025, 37, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, J.F.; Sallman, D.A.; Recher, C.; Daver, N.G.; Leung, A.Y.H.; Hiwase, D.K.; Subklewe, M.; Pabst, T.; Montesinos, P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Magrolimab plus azacitidine vs physician's choice for untreated TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: the ENHANCE-2 study. Blood 2025, 146, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, F.; Yoshida, S.; Saito, Y.; Hijikata, A.; Kitamura, H.; Tanaka, S.; Nakamura, R.; Tanaka, T.; Tomiyama, H.; Saito, N.; et al. Chemotherapy-resistant human AML stem cells home to and engraft within the bone-marrow endosteal region. Nat Biotechnol 2007, 25, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagadinou, E.D.; Sach, A.; Callahan, K.; Rossi, R.M.; Neering, S.J.; Minhajuddin, M.; Ashton, J.M.; Pei, S.; Grose, V.; O'Dwyer, K.M.; et al. BCL-2 inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, A.M.; Elsharkawy, N.M.; Kandeel, E.Z.; Hanafi, M.; Samra, M.; Osman, R.A. Leukemia Stem Cell Frequency at Diagnosis Correlates With Measurable/Minimal Residual Disease and Impacts Survival in Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 867684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan Rajsri, K.; Roy, N.; Chakraborty, S. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells in Minimal/Measurable Residual Disease Detection. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpp, A.; Essers, M.; Wilson, A. Awakening dormant haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2010, 10, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Uchida, N.; Tanaka, S.; Suzuki, N.; Tomizawa-Murasawa, M.; Sone, A.; Najima, Y.; Takagi, S.; Aoki, Y.; Wake, A.; et al. Induction of cell cycle entry eliminates human leukemia stem cells in a mouse model of AML. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Multistep clonal evolution from normal hematopoietic stem cell to leukemic stem cell in AML. Normal HSCs acquire initiating mutations in epigenetic modifier genes (DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1/2, ASXL1), generating pre-leukemic HSCs that expand clonally but retain differentiation capacity (CHIP). After a latency period of years to decades, acquisition of secondary mutations in proliferation-associated genes (NPM1, FLT3-ITD, KRAS/NRAS, KMT2A rearrangements) transforms pre-leukemic HSCs into LSCs capable of initiating overt leukemia. LSCs reside within protective bone marrow niches and exhibit quiescence, self-renewal, therapy resistance, and immune evasion. LSCs give rise to rapidly proliferating leukemic blasts with blocked differentiation. Aberrant surface markers (CD123, TIM-3, CLL-1) distinguish LSCs from normal HSCs and represent potential therapeutic targets; Illustration created with Gemini 3.

Figure 1.