Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Media

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Hgt13p with HGTs

2.3. RNA Extraction

2.4. cDNA Synthesis

2.4.1. DNase I Treatment

2.4.2. cDNA Synthesis

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR and Analysis

2.6. Construction of HGTs Gene Deletion

Transformation of C. auris

2.7. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.8. 3H-FLC Accumulation Assay

2.9. Membrane Permeability Assay by Using NPN-Based Assay

2.10. Glucose Accumulation Assay

2.11. Homology Modelling and Docking

2.12. MD Simulation Setup

2.13. Trajectory Analysis

2.14. MM-GBSA Free Energy Calculation

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification, Homology and Phylogenetic Analysis of HGT Genes in C. auris

3.2. HGTs Exhibit Conserved Sugar-Transporter Domains with Variable Numbers of Transmembrane Helices

3.3. HGT Genes Show Distinct Expression Patterns under Basal and Fluconazole-Induced Conditions

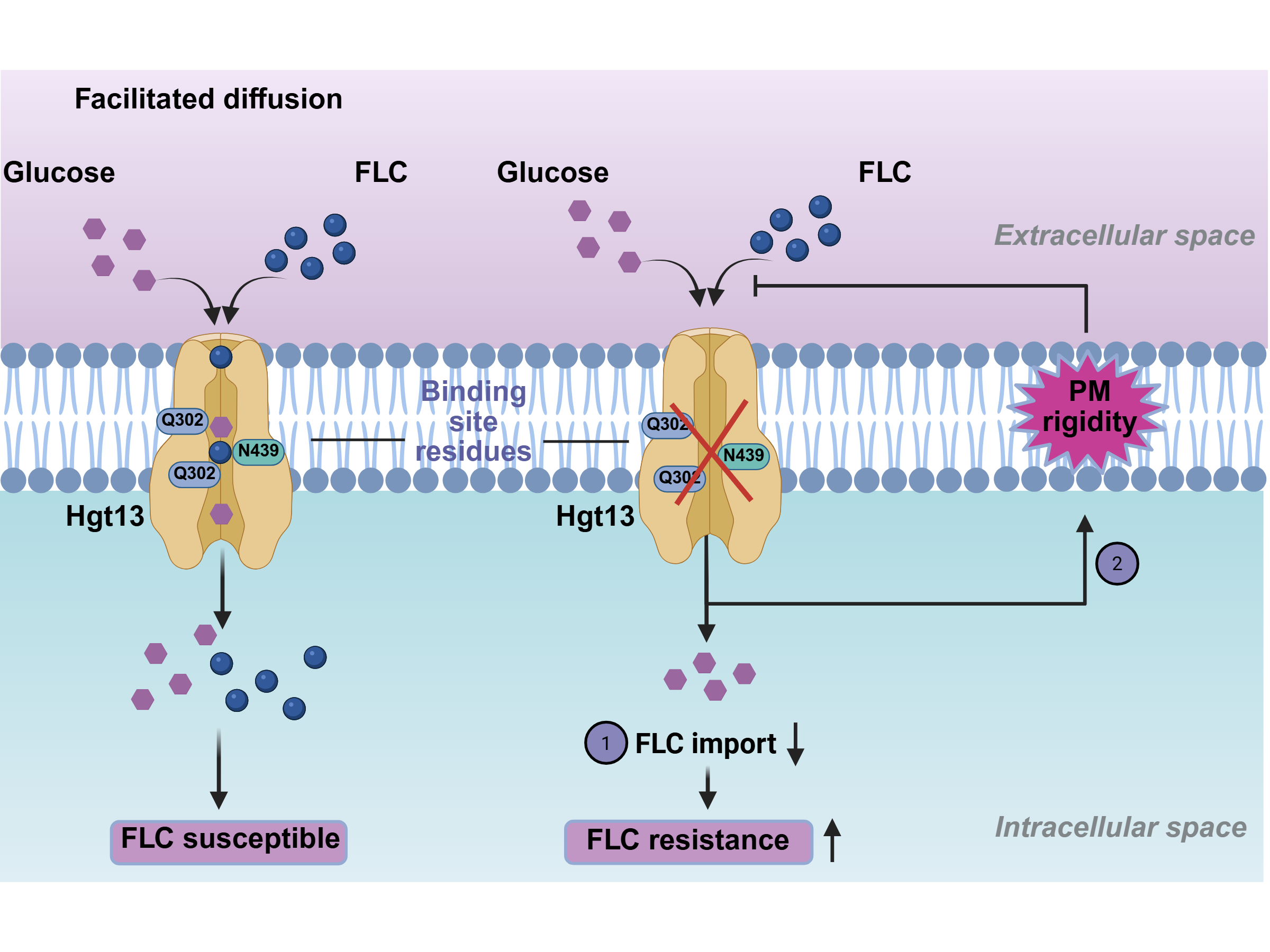

3.4. Δhgt13 Exhibits Enhanced FLC Resistance and Reduced Intracellular Drug Accumulation

3.5. Δhgt13 Elevates Membrane Rigidity Independently of Glucose Uptake

3.6. Molecular Modelling and Docking of Hgt13p

3.7. MD Simulations Indicate a High-Affinity Interaction Between Hgt13p and FLC, Supported by Conserved Active-Site Residues

3.7.1. Structural Stability of Hgt13p and Docked Complexes

3.7.2. Spatial Stability of Ligands within the Active Site of Hgt13p

3.7.3. Free Energy Landscape of Hgt13p and Docked Complexes

3.7.4. Binding Free Energy of Ligands

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.-Y. Human Fungal Pathogens: Why Should We Learn? J Microbiol 2016, 54, 145–148. [CrossRef]

- Schelenz, S.; Hagen, F.; Rhodes, J.L.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Hall, A.; Ryan, L.; Shackleton, J.; Trimlett, R.; Meis, J.F.; et al. First Hospital Outbreak of the Globally Emerging Candida Auris in a European Hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2016, 5, 35. [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, K.; Woodworth, K.; Walters, M.; Berkow, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Chiller, T.; Vallabhaneni, S. Candida Auris: The Recent Emergence of a Multidrug-Resistant Fungal Pathogen. Med Mycol 2019, 57, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Anuradha Chowdhary, A.C.; Anupam Prakash, A.P.; Cheshta Sharma, C.S.; Kordalewska, M.; Anil Kumar, A.K.; Smita Sarma, S.S.; Bansidhar Tarai, B.T.; Ashutosh Singh, A.S.; Gargi Upadhyaya, G.U.; Shalini Upadhyay, S.U. A Multicentre Study of Antifungal Susceptibility Patterns among 350 Candida Auris Isolates (2009-17) in India: Role of the ERG11 and FKS1 Genes in Azole and Echinocandin Resistance. 2018.

- Jacobs, S.E.; Jacobs, J.L.; Dennis, E.K.; Taimur, S.; Rana, M.; Patel, D.; Gitman, M.; Patel, G.; Schaefer, S.; Iyer, K.; et al. Candida Auris Pan-Drug-Resistant to Four Classes of Antifungal Agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e00053-22. [CrossRef]

- Carolus, H.; Pierson, S.; Muñoz, J.F.; Subotic, A.; Cruz, R.B.; Cuomo, C.A.; Dijck, P. Genome-Wide Analysis of Experimentally Evolved Candida Auris Reveals Multiple Novel Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance. mBio 2021, 12, 03333–20. [CrossRef]

- Wasi, M.; Kumar Khandelwal, N.; Moorhouse, A.J.; Nair, R.; Vishwakarma, P.; Bravo Ruiz, G.; Ross, Z.K.; Lorenz, A.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. ABC Transporter Genes Show Upregulated Expression in Drug-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Candida Auris: A Genome- Wide Characterization of ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Genes. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Yan, W.; Jiang, S.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Qiao, D.; Li, N. A Comparative Transcriptome between Anti-Drug Sensitive and Resistant Candida Auris in China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 708009.

- Narayanan, A. Directed Evolution Detects Supernumerary Centric Chromosomes Conferring Resistance to Azoles in Candida Auris. MBio 2022, 13, 03052–22.

- Shivarathri, R.; Jenull, S.; Chauhan, M.; Singh, A.; Mazumdar, R.; Chowdhary, A.; Kuchler, K.; Chauhan, N. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveal Possible Mechanisms of Amphotericin B Resistance in Candida Auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e02276-21. [CrossRef]

- Massic, L.; Doorley, L.A.; Jones, S.J.; Richardson, I.; Siao, D.D.; Siao, L.; Dykema, P.; Hua, C.; Schneider, E.; Cuomo, C.A.; et al. Acquired Amphotericin B Resistance Attributed to a Mutated ERG3 in Candidozyma Auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2025, 69, e0060125. [CrossRef]

- Rybak, J.M.; Barker, K.S.; Muñoz, J.F.; Parker, J.E.; Ahmad, S.; Mokaddas, E.; Abdullah, A.; Elhagracy, R.S.; Kelly, S.L.; Cuomo, C.A.; et al. In Vivo Emergence of High-Level Resistance during Treatment Reveals the First Identified Mechanism of Amphotericin B Resistance in Candida Auris. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022, 28, 838–843. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Carolus, H.; Sofras, D.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, P.; Nair, R.; Narayanan, A.; Yadav, K.; Ali, B.; Biriukov, V.; et al. Multi-Omics Analysis of Experimentally Evolved Candida Auris Isolates Reveals Modulation of Sterols, Sphingolipids, and Oxidative Stress in Acquired Amphotericin B Resistance. Molecular Microbiology 2025, 124, 154–172. [CrossRef]

- Phan-Canh, T.; Nguyen-Le, D.-M.; Luu, P.-L.; Khunweeraphong, N.; Kuchler, K. Rapid in Vitro Evolution of Flucytosine Resistance in Candida Auris. mSphere 2025, 10, e0097724. [CrossRef]

- LaFleur, M.D.; Kumamoto, C.A.; Lewis, K. Candida Albicans Biofilms Produce Antifungal-Tolerant Persister Cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 3839–3846. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.R.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. The Role of Candida Albicans Stress Response Pathways in Antifungal Tolerance and Resistance. iScience 2022, 25, 103953. [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Raney, M.; Pareek, A.; Kaur, R. Epigenetic Regulation of Antifungal Drug Resistance. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 875. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, L.E.; Sanglard, D.; Howard, S.J.; Rogers, P.D.; Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2015, 5, a019752.

- Perlin, D.S.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A. The Global Problem of Antifungal Resistance: Prevalence, Mechanisms, and Management. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2017, 17, e383–e392. [CrossRef]

- Rybak, J.M.; Doorley, L.A.; Nishimoto, A.T.; Barker, K.S.; Palmer, G.E.; Rogers, P.D. Abrogation of Triazole Resistance upon Deletion of CDR1 in a Clinical Isolate of Candida Auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63:e00057-19. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Novel Gene of Candida Albicans, CDR1, Conferring Multiple Resistance to Drugs and Antifungals. Current genetics 1995, 27, 320–329.

- Sun, N.; Li, D.; Fonzi, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Calderone, R. Multidrug-Resistant Transporter Mdr1p-Mediated Uptake of a Novel Antifungal Compound. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 5931–5939. [CrossRef]

- Rybak, J.M.; Muñoz, J.F.; Barker, K.S.; Parker, J.E.; Esquivel, B.D.; Berkow, E.L.; Lockhart, S.R.; Gade, L.; Palmer, G.E.; White, T.C.; et al. Mutations in TAC1B : A Novel Genetic Determinant of Clinical Fluconazole Resistance in Candida Auris. mBio 2020, 11, e00365-20. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh-Khanna, D.-S.; Piña Páez, C.G.; He, S.; Dolan, E.G.; Mirpuri, K.S.; Stajich, J.E.; Hogan, D.A. Coordinated Regulation of Mdr1- and Cdr1-Mediated Protection from Antifungals by the Mrr1 Transcription Factor in Emerging Candida Spp. mBio 2025, 16, e0132325. [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B.E. Azole Drugs Are Imported by Facilitated Diffusion in Candida Albicans and Other Pathogenic Fungi. PLoS pathogens 2010, 6, 1001126.

- Esquivel, B.D.; Smith, A.R.; Zavrel, M.; White, T.C. Azole Drug Import into the Pathogenic Fungus Aspergillus Fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 3390–3398. [CrossRef]

- Galocha, M.; Costa, I.V.; Teixeira, M.C. Carrier-mediated drug uptake in fungal pathogens. Genes 2020, 11, 1324.

- Galocha, M. Genomic Evolution towards Azole Resistance in Candida Glabrata Clinical Isolates Unveils the Importance of CgHxt4/6/7 in Azole Accumulation. Communications Biology 2022, 5, 1118.

- Yasin, R.; Usman, S.; Qin, Q.; Gong, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Jin, C.; Fang, W. Key Sugar Transporters Drive Development and Pathogenicity in Aspergillus Flavus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2025, 15, 1661799. [CrossRef]

- Donzella, L.; Sousa, M.J.; Morrissey, J.P. Evolution and Functional Diversification of Yeast Sugar Transporters. Essays Biochem 2023, 67, 811–827. [CrossRef]

- K Redhu, A.; Shah, A.H.; Prasad, R. MFS Transporters of Candida Species and Their Role in Clinical Drug Resistance. FEMS Yeast Res 2016, 16, fow043. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Texeira, M.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Voordeckers, K.; Thevelein, J.M. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Plasma Membrane Nutrient Sensors and Their Role in PKA Signaling. FEMS Yeast Research 2010, 10, 134–149.

- Biswas, C. Functional Characterization of the Hexose Transporter Hxt13p: An Efflux Pump That Mediates Resistance to Miltefosine in Yeast. Fungal genetics and biology 2013, 61, 23–32.

- Nourani, A.; Wesolowski-Louvel, M.; Delaveau, T.; Jacq, C.; Delahodde, A. Multiple-Drug-Resistance Phenomenon in the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae : Involvement of Two Hexose Transporters. Molecular and Cellular Biology 1997, 17, 5453–5460. [CrossRef]

- Zamith-Miranda, D.; Heyman, H.M.; Cleare, L.G.; Couvillion, S.P.; Clair, G.C.; Bredeweg, E.L.; Gacser, A.; Nimrichter, L.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Multi-Omics Signature of Candida Auris , an Emerging and Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen. mSystems 2019, 4, e00257-19. [CrossRef]

- Gietz, D.; Jean, A.St.; Woods, R.A.; Schiestl, R.H. Improved Method for High Efficiency Transformation of Intact Yeast Cells. Nucl Acids Res 1992, 20, 1425–1425. [CrossRef]

- Clinical; Institute, L.S. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard 2002.

- Esquivel, B.D.; White, T.C. Accumulation of Azole Drugs in the Fungal Plant Pathogen Magnaporthe Oryzae Is the Result of Facilitated Diffusion Influx. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1320. [CrossRef]

- Niemirowicz, K.; Durnaś, B.; Tokajuk, G.; Piktel, E.; Michalak, G.; Gu, X.; Kułakowska, A.; Savage, P.B.; Bucki, R. Formulation and Candidacidal Activity of Magnetic Nanoparticles Coated with Cathelicidin LL-37 and Ceragenin CSA-13., Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 4610. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zeng, X.; Yan, C.; Sun, X.; Gong, X.; Rao, Y.; Yan, N. Crystal Structure of a Bacterial Homologue of Glucose Transporters GLUT1–4. Nature 2012, 490, 361–366.

- Bugnon, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Goullieux, M.; Perez, M.A.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissDock 2024: Major Enhancements for Small-Molecule Docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic acids research 2024, 52, W324–W332.

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, Flexible, and Free. J Comput Chem 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.M.; MacKerell, A.D.; Reuter, N. Cation-π Interactions between Methylated Ammonium Groups and Tryptophan in the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) I: Bond Perception and Atom Typing. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 3144–3154. [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Park, S.; Choi, Y.K.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder : Past, Current, and Future Developments and Applications. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 2161–2185. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, C.B.; Pandey, P.; Sharma, R.D.; Malik, M.Z.; Mongre, R.K.; Lynn, A.M.; Prasad, R.; Jeon, R.; Prakash, A. Identifying the Natural Polyphenol Catechin as a Multi-Targeted Agent against SARS-CoV-2 for the Plausible Therapy of COVID-19: An Integrated Computational Approach. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22, 1346–1360.

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [CrossRef]

- Cauldron, N.C.; Shea, T.; Cuomo, C.A. Improved Genome Assembly of Candida Auris Strain B8441 and Annotation of B11205. Microbiol Resour Announc 2024, 13, e00512-24. [CrossRef]

- Structural Advances for the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) Transporters - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23403214/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Quistgaard, E.M.; Löw, C.; Guettou, F.; Nordlund, P. Understanding Transport by the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS): Structures Pave the Way. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500.

- Karplus, M.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Biomolecules. Nature structural biology 2002, 9, 646–652.

- Gorelov, S.; Titov, A.; Tolicheva, O.; Konevega, A.; Shvetsov, A. DSSP in GROMACS: Tool for Defining Secondary Structures of Proteins in Trajectories. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3593–3598. [CrossRef]

- Moritsugu, K.; Terada, T.; Kidera, A. Free-Energy Landscape of Protein–Ligand Interactions Coupled with Protein Structural Changes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Stenström, O.; Diehl, C.; Modig, K.; Akke, M. Ligand-Induced Protein Transition State Stabilization Switches the Binding Pathway from Conformational Selection to Induced Fit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2024, 121, e2317747121. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Naiyer, A.; Kumar, P.; Parkash, A. Mechanism of Folding and Stability of Met80Gly Mutant of Cytochrome-c. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2024, 408, 125131.

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2015, 10, 449–461. [CrossRef]

- Sanglard, D.; Coste, A.T. Activity of Isavuconazole and Other Azoles against Candida Clinical Isolates and Yeast Model Systems with Known Azole Resistance Mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Rasmussen, M.D.; Lin, M.F.; Santos, M.A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Munro, C.A.; Rheinbay, E.; Grabherr, M.; Forche, A.; Reedy, J.L. Evolution of Pathogenicity and Sexual Reproduction in Eight Candida Genomes. Nature 2009, 459, 657–662.

- Jackson, A.P.; Gamble, J.A.; Yeomans, T.; Moran, G.P.; Saunders, D.; Harris, D.; Aslett, M.; Barrell, J.F.; Butler, G.; Citiulo, F. Comparative Genomics of the Fungal Pathogens Candida Dubliniensis and Candida Albicans. Genome research 2009, 19, 2231–2244.

- Qadri, H.; Qureshi, M.F.; Mir, M.A.; Shah, A.H. Glucose - The X Factor for the Survival of Human Fungal Pathogens and Disease Progression in the Host. Microbiological Research 2021, 247, 126725. [CrossRef]

- Van Ende, M.; Wijnants, S.; Van Dijck, P. Sugar Sensing and Signaling in Candida Albicans and Candida Glabrata. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 99. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Singh, R.; Das, A.K.; Maiti, M.K. Characterization of Two Sugar Transporters Responsible for Efficient Xylose Uptake in an Oleaginous Yeast Candida Tropicalis SY005. Arch Biochem Biophys 2020, 695, 108645. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, J.C.; Bahn, Y.-S.; van den Berg, B.; Heitman, J.; Xue, C. Nutrient and Stress Sensing in Pathogenic Yeasts. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 442. [CrossRef]

- Rodaki, A.; Bohovych, I.M.; Enjalbert, B.; Young, T.; Odds, F.C.; Gow, N.A.R.; Brown, A.J.P. Glucose Promotes Stress Resistance in the Fungal Pathogen Candida Albicans. Mol Biol Cell 2009, 20, 4845–4855. [CrossRef]

- Leandro, M.J.; Gonçalves, P.; Spencer-Martins, I. Two Glucose/Xylose Transporter Genes from the Yeast Candida Intermedia: First Molecular Characterization of a Yeast Xylose–H+ Symporter. Biochemical Journal 2006, 395, 543–549.

| Strains/Mutants | Genes name and ID |

| CBS10913T (wild type) | |

| CBS10913T_Δhgt2 | HGT2 (B9J08_005568) |

| CBS10913T_Δhgt12 | HGT12 (B9J08_002250) |

| CBS10913T_Δhgt13 | HGT13 (B9J08_001015) |

| CBS10913T_Δhgt19 | HGT19 (B9J08_005025) |

| CBS10913T_Δhxt5 | HXT5 (B9J08_002646) |

| CBS10913T_Δhgt4 | HGT4 (B9J08_002259) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).