Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

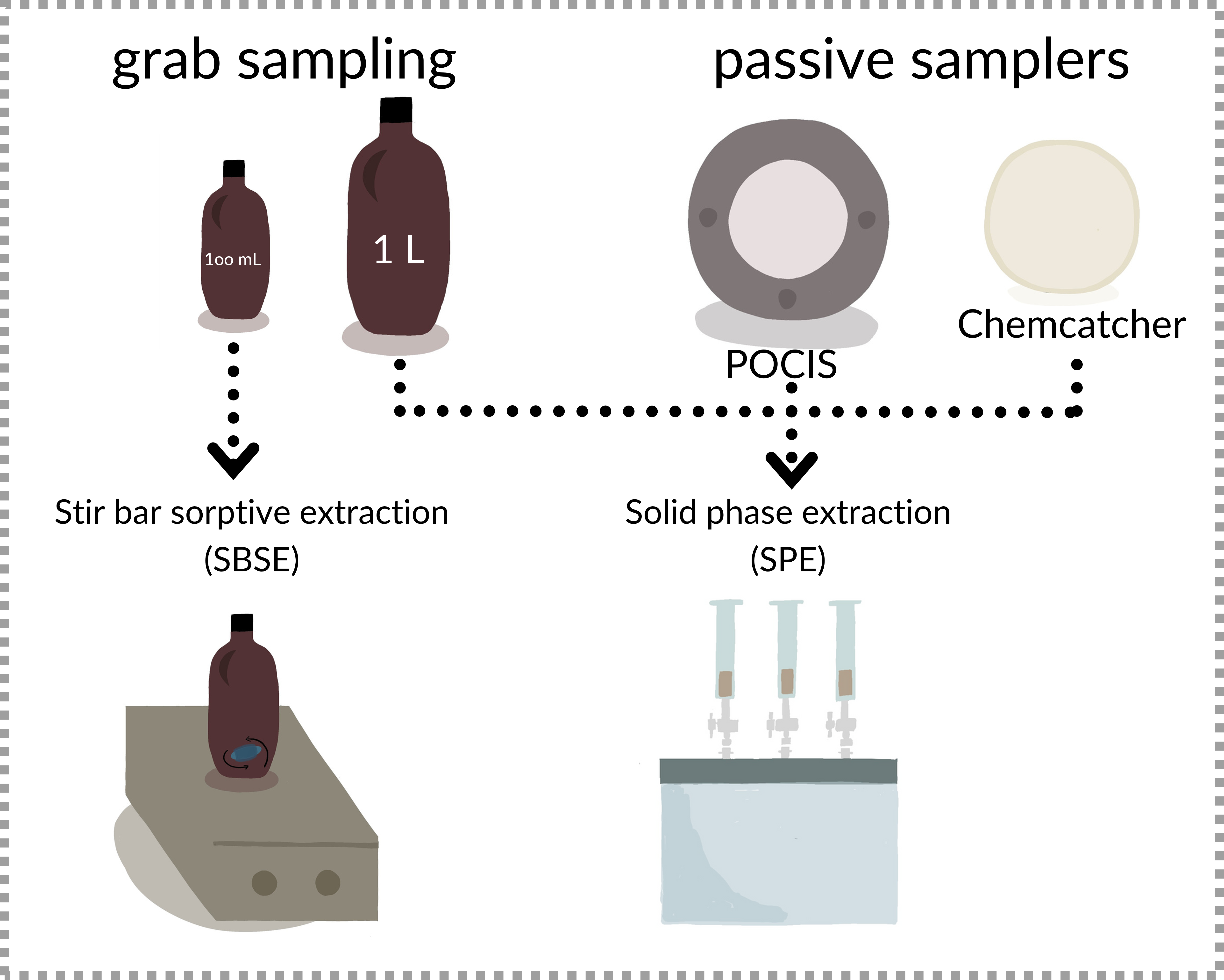

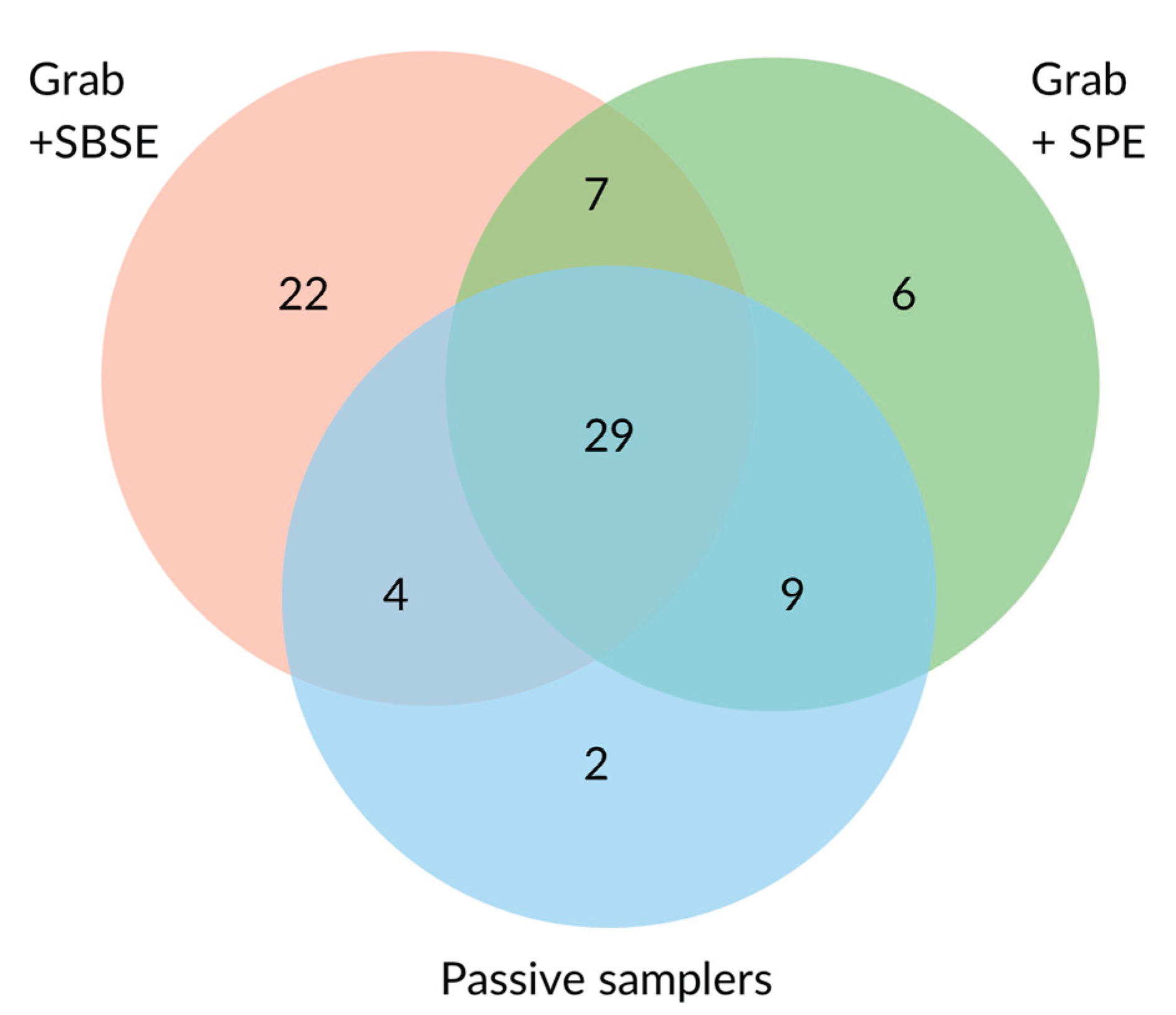

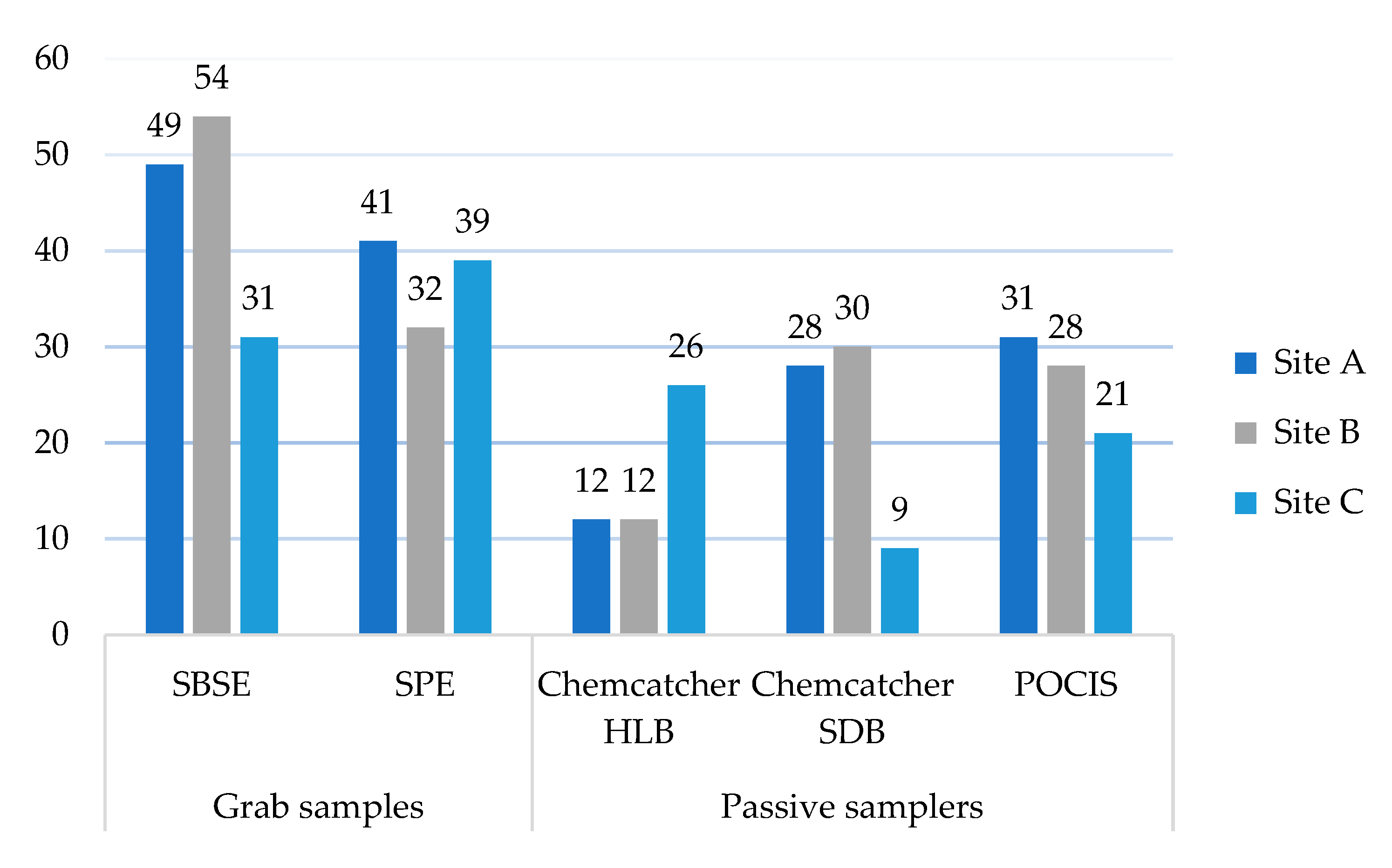

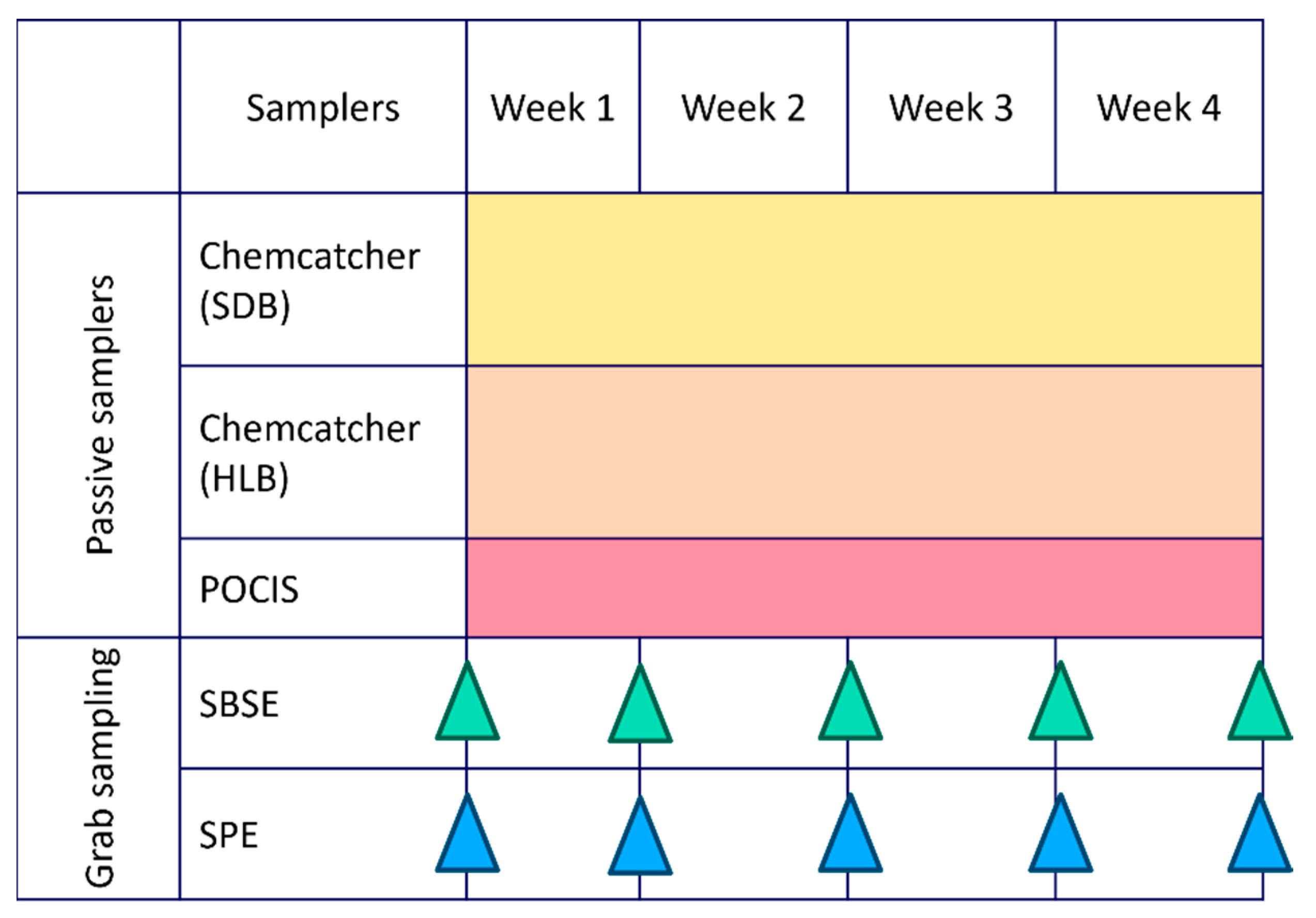

Pesticide contamination poses significant threats to both humans and the environment, with residues frequently detected in surface waters worldwide. This study compares the effectiveness of passive samplers (POCIS and Chemcatcher), and grab sampling coupled with Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction (SBSE) and Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) for monitoring pesticides in surface waters. The comparative study was conducted at three sites in Victoria, Australia, representing different land uses. A total of 230 pesticides were screened, with 79 different pesticides detected overall. SBSE extracted the highest number of pesticides from grab samples, followed by SPE and passive samplers. The study highlights the complementarity of different sampling and extraction techniques in detecting a wide range of pesticides. The study also explores the suitability of these techniques for citizen science applications, emphasizing the importance of selecting appropriate methods based on specific research objectives and available resources. The findings underscore the need for a tiered approach, combining passive samplers for initial screening and grab sampling for quantitative analysis, to develop a robust monitoring strategy for protecting water quality.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Performance of the Different Sampling and Extraction Methods in Terms of Pesticides Detected

2.2. Performance at the Different Sampling Sites

2.3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Passive Samplers and Grab Samples

2.4. Suitability for Applications in Citizen Science

3. Materials and Methods

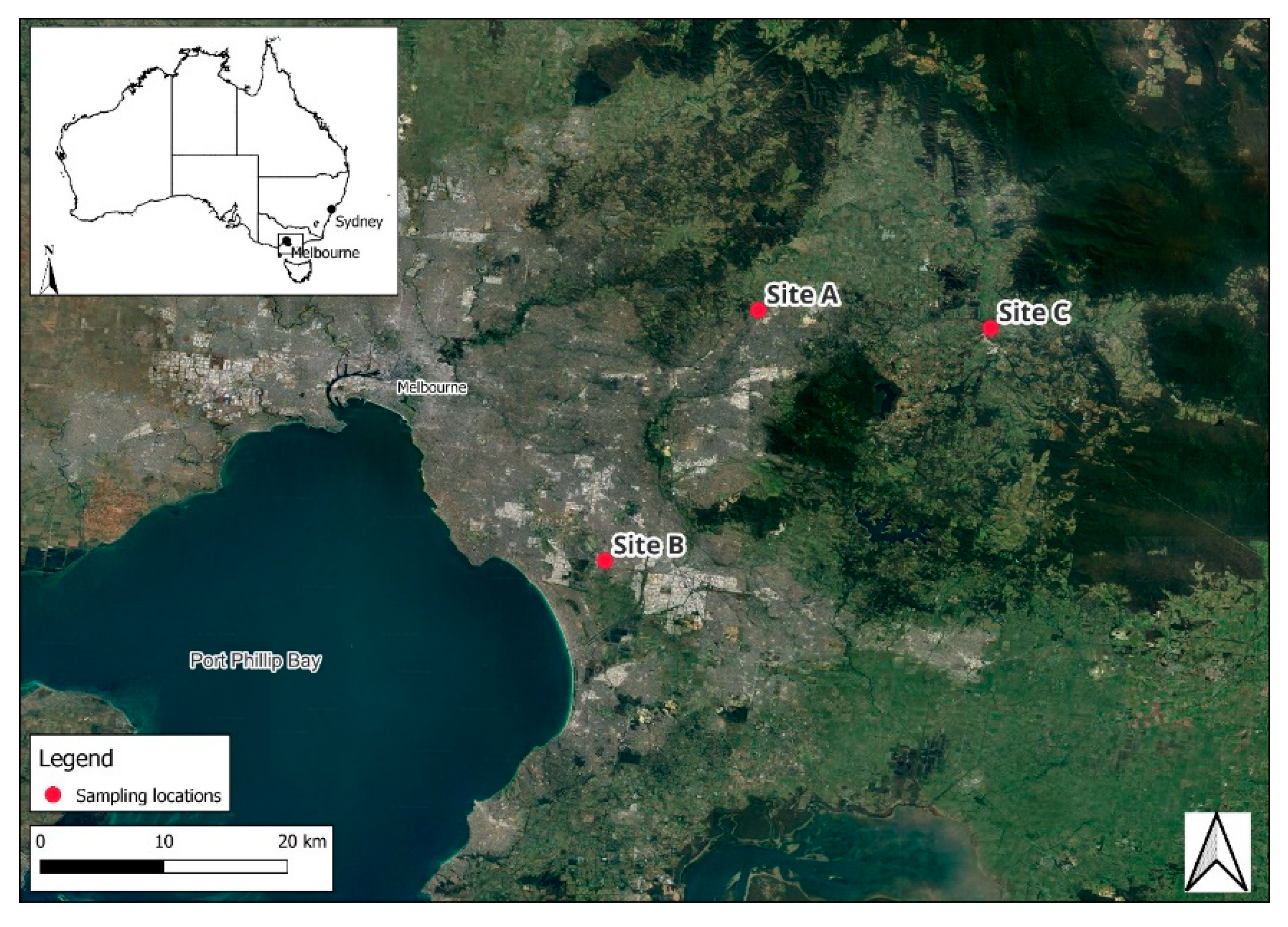

3.1. Sampling Sites

3.2. Chemicals

3.3. Samplers Preparation

3.4. Sample Processing

3.5. Chemical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POCIS | Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler |

| SBSE | Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction |

| SPE | Solid Phase Extraction |

| AUD | Australian Dollars |

| NMI | National Monitoring Institute |

| EDC | Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals |

| RMIT | Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology |

| AQUEST | Aquatic Environmental Stress Research Group |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| HLB | Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance |

| PES | Polyether Sulfone |

| SDB-XC | Polystyrene-DivinylBenzene |

| PDMS | Polydimethyl Siloxane |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| GC-QToF-HRMS | Gas Chromatography-Quadruple Time of Flight –High Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| MPS | Multi-Purpose Sampler |

| TDU2 | Thermal Desorption Unit |

References

- M. F. Ahmad et al., “Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 7, p. e29128, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Valenzuela, H. C. Menezes, and Z. L. Cardeal, “Passive and grab sampling methods to assess pesticide residues in water. A review,” Environmental Chemistry Letters, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 1019–1048, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. M. de Souza, D. Seibert, H. B. Quesada, F. de J. Bassetti, M. R. Fagundes-Klen, and R. Bergamasco, “Occurrence, impacts and general aspects of pesticides in surface water: A review,” Process Safety and Environmental Protection, vol. 135, pp. 22–37, 2020, . [CrossRef]

- FAO, Water quality in agriculture: Risks and risk mitigation. FAO; IWMI;, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A.Sharma et al., “Global trends in pesticides: A looming threat and viable alternatives,” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, vol. 201, p. 110812, 2020, . [CrossRef]

- APVMA, “Agricultural (pesticides) product sales for the 2022–23 financial year,” Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicine Authority, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.apvma.gov.au/about/accountability-and-reporting/annual-product-sales-data/publication-annual-product-sales-data-2022-23.

- 2024. Available online: https://portal.apvma.gov.au/pubcris.

- Agriculture & Environment Research Unit (AERU), “IUPAC Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB).” University of Hertfordshire, 2018. [Online]. Available: http://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru /ppdb/en/.

- P. Serasinghe, H. T. K. Nguyen, T. D. Silva, D. Nugegoda, and V. Pettigrove, “A novel approach for tailoring pesticide screens for monitoring regional aquatic ecosystems,” Environmental Advances, vol. 9, p. 100277, 2022, . [CrossRef]

- C. Campanale, C. Massarelli, D. Losacco, D. Bisaccia, M. Triozzi, and V. F. Uricchio, “The monitoring of pesticides in water matrices and the analytical criticalities: A review,” TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, vol. 144, p. 116423, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Hageman et al., “Current-use pesticides in New Zealand streams: Comparing results from grab samples and three types of passive samplers,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 254, p. 112973, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- P. Serasinghe, H. T. Nguyen, C. Hepburn, D. Nugegoda, and V. Pettigrove, “Use of passive sampling and high-resolution mass spectrometry for screening emerging pesticides of concern within surface waters,” Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, vol. 13, p. 100408, 2024, . [CrossRef]

- V. Pettigrove et al., “Catchment sourcing urban pesticide pollution using constructed wetlands in Melbourne, Australia,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 863, p. 160556, 2023, . [CrossRef]

- J. J. Grandy, V. Galpin, V. Singh, and J. Pawliszyn, “Development of a Drone-Based Thin-Film Solid-Phase Microextraction Water Sampler to Facilitate On-Site Screening of Environmental Pollutants,” Anal. Chem., vol. 92, no. 19, pp. 12917–12924, Oct. 2020, . [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, A. Hibberd, and J. L. Zhou, “Analysis of emerging contaminants in sewage effluent and river water: Comparison between spot and passive sampling,” Analytica Chimica Acta, vol. 607, no. 1, pp. 37–44, Jan. 2008, . [CrossRef]

- N. Ochiai et al., “Stir bar sorptive extraction and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry for ultra-trace analysis of organochlorine pesticides in river water,” Journal of Chromatography A, vol. 1218, no. 39, pp. 6851–6860, Sep. 2011, . [CrossRef]

- A.Prieto et al., “Stir-bar sorptive extraction: A view on method optimisation, novel applications, limitations and potential solutions,” Journal of Chromatography A, vol. 1217, no. 16, pp. 2642–2666, 2010, . [CrossRef]

- D. Fraisl et al., “Mapping citizen science contributions to the UN sustainable development goals,” Sustain Sci, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1735–1751, Nov. 2020, . [CrossRef]

- S. Fritz et al., “Citizen science and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals,” Nature Sustainability, vol. 2, no. 10, pp. 922–930, Oct. 2019, . [CrossRef]

- WWQA, “Technical Brief - The role of citizen science in improving ambient water quality.” Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Carvalho et al., “Protecting and restoring Europe’s waters: An analysis of the future development needs of the Water Framework Directive,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 658, pp. 1228–1238, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- J. von Gönner et al., “Citizen science shows that small agricultural streams in Germany are in a poor ecological status,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 922, p. 171183, 2024, . [CrossRef]

- M. J. O. Pocock, I. Hamlin, J. Christelow, H. Passmore, and M. Richardson, “The benefits of citizen science and nature-noticing activities for well-being, nature connectedness and pro-nature conservation behaviours,” People and Nature, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 591–606, Apr. 2023, . [CrossRef]

- E. Roger et al., “Open Access Research Infrastructures are Critical for Improving the Accessibility and Utility of Citizen Science: A Case Study of Australia’s National Biodiversity Infrastructure, the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA),” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 56, Sep. 2023, . [CrossRef]

- S. Warner et al., “Empowering citizen scientists to improve water quality: from monitoring to action,” Frontiers in Water, vol. 6, 2024, . [CrossRef]

- S. Hegarty, A. Hayes, F. Regan, I. Bishop, and R. Clinton, “Using citizen science to understand river water quality while filling data gaps to meet United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 objectives,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 783, p. 146953, Aug. 2021, . [CrossRef]

- M. A. Yevenes, H. Pereira, and R. Bermudez, “Citizen Science as a Co-Creative Measure to Water Quality: Chemical Data and Local Participation in a Rural Territory,” Front. Environ. Sci., vol. 10, p. 940778, Sep. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, R. Ma, M. Hu, J. Luo, J. Li, and Q. Liang, “Combining citizen science and land use data to identify drivers of eutrophication in the Huangpu River system,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 584–585, pp. 651–664, 2017, . [CrossRef]

- RMIT AQUEST, “The Pesticide Detectives: national assessment of pesticides in waters.” Accessed: Jun. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.rmit.edu.au/about/schools-colleges/science/research/research-centres-groups/aquatic-environmental-stress/pesticide-detectives.

- Deakin University, “Pesticide Watch.” Accessed: Jun. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.deakin.edu.au/pesticidewatch/.

- L. Ahrens, A. Daneshvar, A. E. Lau, and J. Kreuger, “Characterization of five passive sampling devices for monitoring of pesticides in water,” Journal of Chromatography A, vol. 1405, pp. 1–11, 2015, . [CrossRef]

- M. Grodtke, A. Paschke, J. Harzdorf, M. Krauss, and G. Schüürmann, “Calibration and field application of the Atlantic HLB Disk containing Chemcatcher® passive sampler – Quantitative monitoring of herbicides, other pesticides, and transformation products in German streams,” Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 410, p. 124538, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- A.Assoumani, S. Lissalde, C. Margoum, N. Mazzella, and M. Coquery, “In situ application of stir bar sorptive extraction as a passive sampling technique for the monitoring of agricultural pesticides in surface waters,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 463–464, pp. 829–835, Oct. 2013, . [CrossRef]

- EC JRC, “The Gems of Water: engaging citizens to monitor water quality,” European Commission The Joint Research Centre: EU Science Hub. [Online]. Available: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/projects-and-activities/gems-water-engaging-citizens-monitor-water-quality_en.

- C. Cacciatori, J. Myers, G. Mariani, H. Vu, B. M. Gawlik, and V. Pettigrove, “Comparison of Extraction Techniques for Wide Screening of 230 Pesticides in Water,” Separations, vol. 12, no. 6, 2025, . [CrossRef]

- B. Mathon et al., “Polar organic chemical integrative samplers as an effective tool for chemical monitoring of surface waters – Results from one-year monitoring in France,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 824, p. 153549, 2022, . [CrossRef]

- B. Vrana et al., “Passive sampling techniques for monitoring pollutants in water,” TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 845–868, 2005, . [CrossRef]

- Posada-Ureta et al., “Applicability of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polyethersulfone (PES) as passive samplers of more hydrophobic organic compounds in intertidal estuarine environments,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 578, Nov. 2016, . [CrossRef]

- A.Cacciatori et al., “Citizen-engaged screening of 230 pesticides in the Lake Naivasha catchment, Kenya, using stir bar sorptive extraction and GC-QToF-HRMS,” Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. Volume 13-2025, 2025, . [CrossRef]

- A.Cacciatori et al., “Stir bar sorptive extraction TDU-GC-QToF-HRMS for screening 230 pesticides in waters surrounding banana plantations in Costa Rica through community engagement,” Chemosphere, vol. 376, p. 144251, 2025, . [CrossRef]

- G. Mariani et al., “EMBLAS Plus - Joint Black Sea Survey 2019: ‘JRC Chemical Contaminant Measurements,’” no. KJ-NA-30512-EN-N (online),KJ-NA-30512-EN-C (print), 2020, doi: 10.2760/438289 (online),10.2760/946379 (print).

| Sample type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive samplers | Grab samples | ||||

| Log Kow | Chemcatcher HLB disk |

Chemcatcher SBD disk |

POCIS HLB powder |

SBSE | SPE |

| Median | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| Average | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| 1st Quartile | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| 3rd Quartile | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 4.3 |

| Material | Sampler type | Chemcatcher | Chemcatcher | POCIS | SBSE | SPE |

| Absorbent material | HLB disk | SBD disk | HLB bulk | PDMS | HLB cartridge | |

| Selectivity (Log Kow) | -5 - 8 | 2 - 6 | 0 - 4 | 3 - 7 | -5 - 8 | |

|

Sampler & sampling preparation |

Steps | (1) Cleaning of casing (2) Cleaning of PES membrane (3) Pre-cleaning and activation of disks |

(1) Cleaning of casing (2) Cleaning of PES membrane (3) Pre-cleaning and activation of disks |

(1) Cleaning of casing (2) Cleaning of PES membrane |

(1) Cleaning sampling bottles | (2) Cleaning sampling bottles |

| Estimated duration | 1 hour | 45 minutes | 45 minutes | 15 minutes | 15 minutes | |

| Solvent use (est. volume) | Methanol (1 L); MilliQ-water (350 mL); Ethyl acetate (60 mL) | Methanol (2 L); MilliQ-water (500 mL) | Methanol (1 L); MilliQ-water (300 mL); | Aceton (ca. 100) | Aceton (ca. 200 mL) | |

| Sampling | Exposure time | 4 weeks | 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Instantaneous | Instantaneous |

| Sample volume | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 100 mL | 1 L | |

| Sampling casing | 1 PES membrane PTFE casing |

1 PES membrane PTFE casing |

2 PES membranes stainless steel casing |

None | None | |

| Control over monitoring | Low | Low | Low | High | High | |

| Practicality | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | |

| Sample processing | Steps | (1) Drying of disks (2) Elution (3) Extract concentration |

(1) Drying of disks (2) Elution (3) Extract concentration |

(1) Extraction on HLB cartridges (2) Elution (3) Extract concentration |

(1) Thermal conditioning (2) Extraction by magnetic agitation |

(1) Filtering of samples (2) Extraction on HLB cartridges (3) Elution (4) Extract concentration |

| Estimated duration | 8 h | 8 h | 8 h | 10 hours | 8 h | |

| Solvent use (est. volume) | Ethyl acetate (60 mL) Acetone (1 mL) |

Ethyl acetate (20 mL) Acetone (1 mL) |

Ethyl acetate (10 mL) Acetone (1 mL) |

Acetone (1 mL) | Ethyl acetate (10 mL) Acetone (1 mL) |

|

| Contamination risk | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | |

| Analysis & results | Injected volume of sample volume | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 100 mL | 20 mL |

| Type of information | Long-term chemical exposure |

Long-term chemical exposure |

Long-term chemical exposure |

Instantaneous, concentration |

Instantaneous, concentration |

|

| Units | ng/tot | ng/tot | ng/tot | ng/L | ng/L | |

| Citizen science | Suitability | Limited (deployment and retrieval) | High (sampling and extraction, portable, laboratory safe) | Limited (sampling) | ||

| Advantages | Wide polarity range Cheap Continuous monitoring |

Wide polarity range Cheap Continuous monitoring |

Wide polarity range Cheap Continuous monitoring |

Quantitative Easy to apply |

Wide polarity range Quantitative Widely used standardized method |

|

| Disadvantages | Difficult to assemble PES membrane needs to be humid High solvent use Requires manual skills Qualitative Specialized personnel for laboratory work |

Difficult to assemble PES membrane needs to be humid High solvent use Requires manual skills Qualitative Specialized personnel for laboratory work |

Difficult to assemble Limited to polar range Sorbent loss Requires manual skills Qualitative Specialized personnel for laboratory work |

Instantaneous Limited to hydrophobic range Potential environmental contamination Expensive Destructive sample |

Instantaneous Labour intensive process Sample loss Expensive Specialized personnel for laboratory work |

|

| Suggestions | Casing needs to be adapted to thicker disks Deployment should be made easier |

Deployment should be made easier | Deployment should be made easier | Expand polarity range Investigate matrix effects |

Shorten and simplify the procedure | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).