Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

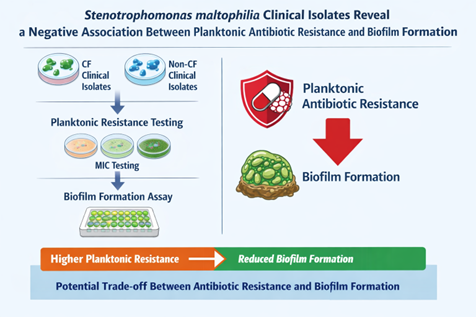

Background/Objectives: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is an emerging opportunistic pathogen associated with severe infections, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). Its intrinsic multidrug resistance and ability to form biofilms significantly complicate treatment. While biofilm growth is widely linked to antimicrobial tolerance, the relationship between biofilm-forming capacity and planktonic antibiotic resistance in S. maltophilia remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the association between antibiotic resistance profiles and biofilm formation in clinical isolates from CF and non-CF patients. Methods: A total of 86 clinical S. maltophilia isolates (40 from CF airways and 46 from non-CF patients) were analyzed. Antibiotic susceptibility to seven agents was assessed by disk diffusion, with results interpreted according to EUCAST and CLSI criteria. Multidrug resistance phenotypes were defined using standard criteria. Biofilm formation was quantified after 24 h using a crystal violet microtiter plate assay and categorized into five levels of production. Statistical analyses were performed to compare biofilm formation across resistance profiles and clinical origins and to assess correlations between biofilm biomass and multidrug resistance. Results: Overall, high resistance rates were observed, particularly to meropenem (87.2%), ciprofloxacin (80.2%), and rifampicin (72.1%). CF isolates showed significantly higher resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam and a higher prevalence of multidrug resistance. Biofilm production was detected in 94.2% of isolates, with strong and powerful biofilm producers predominating. However, isolates from CF patients formed significantly less biofilm than those from non-CF patients. Notably, resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem was associated with significantly reduced biofilm formation, as reflected in both median biomass and the proportion of high biofilm producers. Across the entire collection, the number of antibiotic resistances displayed by an isolate was negatively correlated with biofilm biomass. These trends were maintained after stratification by clinical origin, although some comparisons did not reach statistical significance. Conclusions: These findings demonstrate an unexpected inverse relationship between planktonic antibiotic resistance and biofilm-forming efficiency in S. maltophilia. Enhanced biofilm production may represent an alternative persistence strategy in more antibiotic-susceptible strains, with important implications for infection management and therapeutic failure.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antibiotic Resistance

2.2. Biofilm Formation

2.3. Correlation Between Antibiotic Resistance and Biofilm Formation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Tests

4.3. Biofilm Formation Assay

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| OD | Optical density |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| XDR | Extensively drug resistance |

| PDR | Pandrug resistance |

| EUCAST | European committee for antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| CLSI | Clinical laboratory standards institute |

References

- Brooke, JS. Advances in the Microbiology of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021, 34(3), e0003019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, AC; Waters, VJ. Opportunistic Pathogens in Cystic Fibrosis: Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Lung Infection. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022, 11 Supplement_2, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monardo, R; Mojica, MF; Ripa, M; Aitken, SL; Bonomo, RA; van Duin, D. How do I manage a patient with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infection? Clin Microbiol Infect 2025, 31(8), 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bonaventura, G; Spedicato, I; D’Antonio, D; Robuffo, I; Piccolomini, R. Biofilm formation by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: modulation by quinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ceftazidime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A; Crocetta, V; Confalone, P; Nicoletti, M; Petrucca, A; Guarnieri, S; Fiscarelli, E; Savini, V; Piccolomini, R; Di Bonaventura, G. Adhesion to and biofilm formation on IB3-1 bronchial cells by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. BMC Microbiol 2010, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E; Liang, G; Wang, L; Wei, W; Lei, M; Song, S; Han, R; Wang, Y; Qi, W. Antimicrobial susceptibility of hospital acquired Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolate biofilms. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatidou, E; Matthews, AC; Kuhlicke, U; Neu, TR; McEvoy, JP; Raymond, B. Biofilms facilitate cheating and social exploitation of β-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, HY; Prentice, EL; Webber, MA. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in biofilms. NPJ Antimicrob Resist 2024, 2(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, C; Grohmann, E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12(2), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A; Sun, J; Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høiby, N; Bjarnsholt, T; Givskov, M; Molin, S; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010, 35(4), 322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, TK; Knabel, SJ; Kwan, BW. Bacterial persister cell formation and dormancy. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79(23), 7116–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, DJ; Sader, HS; Jones, RN. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of a worldwide collection of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates tested against tigecycline and agents commonly used for S. maltophilia infections. Antimicrob Ag Chemother. 2010, 54(6), 2735–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolsma, SL; Sokolow, A; Patel, PC; Sokolow, K; Jimenez-Truque, N; Fissell, WH; Ryan, V; Kirkpatrick, CM; Nation, RL; Gu, K; Teresi, M; Fishbane, N; Kontos, M; An, G; Winokur, P; Landersdorfer, CB; Creech, CB. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Cefepime, Meropenem, and Piperacillin-Tazobactam in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2025, 231(2), e364–e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvig, RL; Sommer, LM; Molin, S; Johansen, HK. Convergent evolution and adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within patients with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2015, 47(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Garcia, F; Hernando-Amado, S; Martinez, JL. Mutation-driven evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the presence of either ceftazidime or ceftazidime/avibactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z; Qin, J; Liu, Y; Li, C; Ying, C. Molecular epidemiology and risk factors of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections in a Chinese teaching hospital. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20(1), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanghadiri, N; Ardebili, A; Ghalavand, Z; Teymouri, S; Mirzarazi, M; Goudarzi, M; Ghasemi, E; Hashemi, A. Antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and biofilm-associated genes among Stenotrophomonas maltophilia clinical isolates. BMC Res Notes 2021, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, JY; Song, JH; Ko, KS. Current Situation of Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Differences in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Complex Isolates by Multilocus Variable Number of Tandem Repeat Analysis. Infect Chemother 2016, 48(4), 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squyres, GR; Newman, DK. Biofilms as more than the sum of their parts: lessons from developmental biology. Curr Opin Microbiol 2024, 82, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A; Mitterer, F; Pombo, JP; Schild, S. Biofilms by bacterial human pathogens: Clinical relevance - development, composition and regulation - therapeutical strategies. Microb Cell 2021, 8(2), 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompilio, A; Ranalli, M; Piccirilli, A; Perilli, M; Vukovic, D; Savic, B; Krutova, M; Drevinek, P; Jonas, D; Fiscarelli, EV; Tuccio Guarna Assanti, V; Tavío, MM; Artiles, F; Di Bonaventura, G. Biofilm Formation among Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Isolates Has Clinical Relevance: The ANSELM Prospective Multicenter Study. Microorganisms 2020, 9(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailovich, V; Heydarov, R; Zimenkov, D; Chebotar, I. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia virulence: a current view. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1385631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, A; Pompilio, A; Bettua, C; Crocetta, V; Giacobazzi, E; Fiscarelli, E; Jousson, O; Di Bonaventura, G. Evolution of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Cystic Fibrosis Lung over Chronic Infection: A Genomic and Phenotypic Population Study. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L; Li, H; Zhang, C; Liang, B; Li, J; Wang, L; Du, X; Liu, X; Qiu, S; Song, H. Relationship between Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm Formation, and Biofilm-Specific Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, AS; Park, GC; Ryu, SY; Lim, DH; Lim, DY; Choi, CH; Park, Y; Lim, Y. Higher biofilm formation in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008, 32(1), 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Castillo, M; Morosini, MI; Valverde, A; Almaraz, F; Baquero, F; Cantón, R; del Campo, R. Differences in biofilm development and antibiotic susceptibility among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from cystic fibrosis samples and blood cultures. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 59(2), 301–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, SJ; Lee, YL; Hsueh, PR. Multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: roles of integrons, efflux pumps, phosphoglucomutase (SpgM), and melanin and biofilm formation. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010, 35(2), 126–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, SJ; Bowman, MC; Turner, RB. Clinical outcomes of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infection treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, or fluoroquinolone monotherapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021, 58(2), 106367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST Disk Diffusion Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Version 13.0 (January 2025). www.eucast.org.

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute - CLSI M02, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests. March 2024.

- Magiorakos, AP; Srinivasan, A; Carey, RB; Carmeli, Y; Falagas, ME; Giske, CG; Harbarth, S; Hindler, JF; Kahlmeter, G; Olsson-Liljequist, B; Paterson, DL; Rice, LB; Stelling, J; Struelens, MJ; Vatopoulos, A; Weber, JT; Monnet, DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012, 18(3), 268–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S; Vuković, D; Hola, V; Di Bonaventura, G; Djukić, S; Cirković, I; Ruzicka, F. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS 2007, 115(8), 891–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).