1. Introduction and Background

Modern supply chains face increasing pressure to operate with greater flexibility, responsiveness, and intelligence. Globalization, volatile demand, and dynamic disruptions—such as pandemics or geopolitical crises—have exposed the limitations of rigid, pre-programmed logistics systems [

1,

2]. To remain competitive, organizations must integrate decision-making systems that can adapt in real time and emulate human-like reasoning in complex, uncertain environments.

Traditional supply chain management systems rely heavily on deterministic optimization models, predefined rules, or static decision trees. While effective under stable conditions, such methods often fail to capture the nuances of behavioral and contextual information needed for real-time adaptive decisions [

3]. Moreover, supply chain decisions are frequently influenced by imprecise criteria—such as urgency, trust, or perceived risk—which are difficult to encode in crisp mathematical terms.

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers new opportunities to enhance supply chain analytics by enabling machines to learn, reason, and adapt based on experience and feedback [

4]. Among various AI techniques, fuzzy logic stands out for its ability to incorporate human-like judgment into computational models. Unlike binary logic systems, fuzzy systems operate over degrees of truth, making them well-suited for interpreting vague or conflicting input conditions.

Fuzzy behavioral models—built on fuzzy inference and linguistic rules—have proven effective in domains such as robotics, control systems, and recommendation engines [

5]. In the context of supply chains, these models can be used to represent decision-maker preferences, model uncertainty, and generate context-aware actions in response to dynamic events. They offer a bridge between qualitative human reasoning and quantitative computational execution.

In this paper, we propose a hybrid AI framework that combines fuzzy logic with behavioral modeling to support adaptive decision-making in supply chain environments. Our approach simulates human decision agents using fuzzy cognitive structures, capturing their response patterns to diverse logistical scenarios. These agents interact with a simulated supply chain environment, producing actions that reflect both quantitative input (e.g., inventory levels) and qualitative context (e.g., urgency, risk perception).

A key advantage of our model is its transparency and interpretability. Unlike deep neural networks, which act as black boxes, fuzzy systems enable explicit rule representation and human-readable decisions. This is especially important in enterprise contexts, where accountability and explainability are essential for trust and adoption [

6].

We implement our decision-making agents within a discrete event simulation that mirrors a simplified supply chain with multiple nodes, transportation delays, and demand fluctuations. The fuzzy controller is responsible for triggering restocking, rerouting, and prioritization actions based on the evolving state of the system. By incorporating behavioral dimensions such as risk aversion, adaptability, and information-seeking tendencies, the model goes beyond traditional logistics optimization.

Our experiments focus on comparing decision behaviors under different fuzzy rule sets and behavioral profiles. We analyze how varying decision heuristics affect performance metrics such as stockout rate, lead time, and overall system responsiveness. The results demonstrate that behavioral AI agents can outperform static logic under uncertain and time-sensitive conditions.

The technical framing of our approach is sound and successfully bridges methodological innovation with practical application, offering both adaptive intelligence and operational relevance for modern supply chain challenges.

2. System Architecture and Simulation Environment

To evaluate the proposed fuzzy behavioral decision model, we developed a modular simulation environment that mimics a simplified multi-node supply chain. This environment allows us to observe how agent-based decision logic impacts key performance indicators such as fulfillment rate, inventory turnover, and delay responsiveness.

2.1. Simulation Overview

The simulated supply chain consists of a linear flow from a central supplier to regional distribution centers (DCs) and finally to retail outlets. Each node maintains local inventory and is subject to fluctuating demand and transportation delays. The simulation is event-driven and operates over discrete time steps, where shipments, stock updates, and decisions are processed sequentially.

Nodes interact with each other via order requests and replenishment flows. Retail demand is stochastic, modeled using a truncated normal distribution. Transport lead times between nodes are randomly sampled from a fixed interval to simulate real-world variability.

2.2. Decision Agent Architecture

Each supply chain node is controlled by a fuzzy decision agent. The agent observes local state variables and uses a fuzzy inference system to determine one of several possible actions, including:

Order: Request replenishment based on forecasted demand and current stock.

Prioritize: Flag certain orders as high urgency based on product criticality or customer segment.

Defer: Delay ordering if risk, cost, or uncertainty is high.

The agent uses linguistic variables to describe uncertain or qualitative inputs (e.g., “low stock”, “high urgency”, “moderate trust”) and maps them to crisp actions using a fuzzy rule base.

2.3. Input Variables and Sensors

Each agent collects the following state inputs:

Inventory Level: Current on-hand stock at the node.

Demand Volatility: Recent fluctuation in customer demand.

Delivery Delay: Average lag between ordering and receiving stock.

Risk Perception: Modeled as an internal trait per agent (discussed in

Section 4).

These inputs are normalized and fuzzified using trapezoidal and triangular membership functions, enabling soft boundary decisions.

2.4. Output Actions

The fuzzy agent produces a numerical urgency score that is used to modulate order size and lead time expectations. A decision threshold is applied to convert this score into discrete actions:

Low urgency: Wait or reduce order quantity.

Medium urgency: Submit standard order.

High urgency: Place expedited order with additional cost.

The action space is designed to reflect real-world decision scenarios where humans balance trade-offs between risk, cost, and responsiveness.

2.5. Simulation Parameters

The simulation operates on a rolling horizon of 100 time steps. Inventory capacity, minimum safety stock, and transportation delay ranges are configurable per scenario. To introduce variability, we simulate both low- and high-volatility environments, altering the shape of demand and transport distributions.

2.6. Implementation Details

The system was implemented in Python using SimPy for event simulation and scikit-fuzzy for fuzzy logic components. The architecture is modular, allowing for different agent types, rule bases, and behavioral models to be tested without altering core environment logic.

2.7. Summary

This simulation architecture enables controlled evaluation of adaptive decision agents in supply chain environments. By embedding fuzzy behavioral models into node-level agents, we can assess how decision logic affects system-wide efficiency under varying uncertainty and resource constraints.

3. Fuzzy Logic Foundations

Fuzzy logic provides a formal framework for reasoning with imprecise and linguistically described variables, making it well-suited for modeling human decision-making under uncertainty. In supply chain systems, where inputs such as urgency, trust, and risk are inherently subjective or vague, fuzzy logic enables more natural decision processes than crisp, binary rules.

3.1. Fuzzy Sets and Membership Functions

Unlike classical sets that assign binary inclusion (i.e., 0 or 1), fuzzy sets allow elements to belong to a set with a degree of membership between 0 and 1. Let

X be a universe of discourse (e.g., stock levels), then a fuzzy set

A over

X is defined as:

Here, is the membership function, typically represented by triangular or trapezoidal shapes in practice. These functions define the degree to which a specific input value belongs to a linguistic category such as “low inventory” or “high volatility.”

3.2. Linguistic Variables

Fuzzy systems rely on linguistic variables to encode human knowledge and preferences. A linguistic variable is defined by:

A name (e.g., Urgency)

A set of linguistic terms (e.g., Low, Medium, High)

A universe of discourse (e.g., [0, 100])

A corresponding set of membership functions

In our supply chain model, linguistic variables include stock level, delay risk, and demand volatility.

3.3. Fuzzy Inference Mechanism

Fuzzy inference is the process of mapping inputs to outputs using a set of “if-then” rules. The general form of a fuzzy rule is:

Where are input variables, are fuzzy sets (antecedents), and B is the fuzzy output set (consequent).

In our model, an example rule might be:

IF Inventory is Low AND Demand Volatility is High THEN Urgency is High

Rules are evaluated using min-max or product-sum inference methods. For each rule, the firing strength (activation degree) is computed, and the results are aggregated.

3.4. Defuzzification

To produce actionable outputs, the aggregated fuzzy output set is converted to a crisp value through defuzzification. The most common method is the centroid approach, which computes the center of gravity of the output membership function:

This crisp value is then used by the agent to select or scale actions such as order quantity or urgency flag.

3.5. Interpretability and Modularity

One of the key advantages of fuzzy logic is its transparency. Decision rules are interpretable and can be tuned by domain experts without retraining the entire system. Additionally, new rules or linguistic categories can be introduced incrementally, allowing for modular and evolving decision frameworks.

3.6. Role in Behavioral Decisioning

In the context of supply chain analytics, fuzzy logic enables agents to blend objective system variables with subjective behavioral traits. For example, an agent with high risk aversion might use a modified rule base that triggers orders earlier in response to volatility. This flexibility supports modeling of diverse decision styles and adaptive heuristics.

4. Behavior Modeling and AI Design

In real-world supply chains, human decision-makers operate under diverse behavioral biases, preferences, and heuristics. To simulate such variability, we extend our fuzzy agent model to include behavioral dimensions such as risk aversion, information preference, and adaptability. Each fuzzy agent’s decisions are guided by a unique behavioral profile that influences rule selection and parameter scaling.

4.1. Behavioral Dimensions

We define three core behavioral traits for each decision agent:

Risk Aversion (RA): Determines sensitivity to uncertainty and volatility. High RA agents issue preemptive orders; low RA agents tolerate risk for efficiency.

Adaptability (AD): Governs how quickly the agent responds to changing input patterns. Highly adaptive agents adjust thresholds dynamically based on recent performance.

Information Preference (IP): Indicates the degree of reliance on external signals versus internal states. High IP agents react strongly to peer performance or alerts.

These traits are encoded as numerical weights that modulate fuzzy membership functions or defuzzified outputs.

4.2. Agent Design

Each agent contains a behavior module that personalizes the fuzzy controller. This module adjusts rule weights or input fuzzification boundaries based on the agent’s profile. For example, a highly risk-averse agent might shift the “low stock” membership function leftward, increasing the likelihood of earlier ordering.

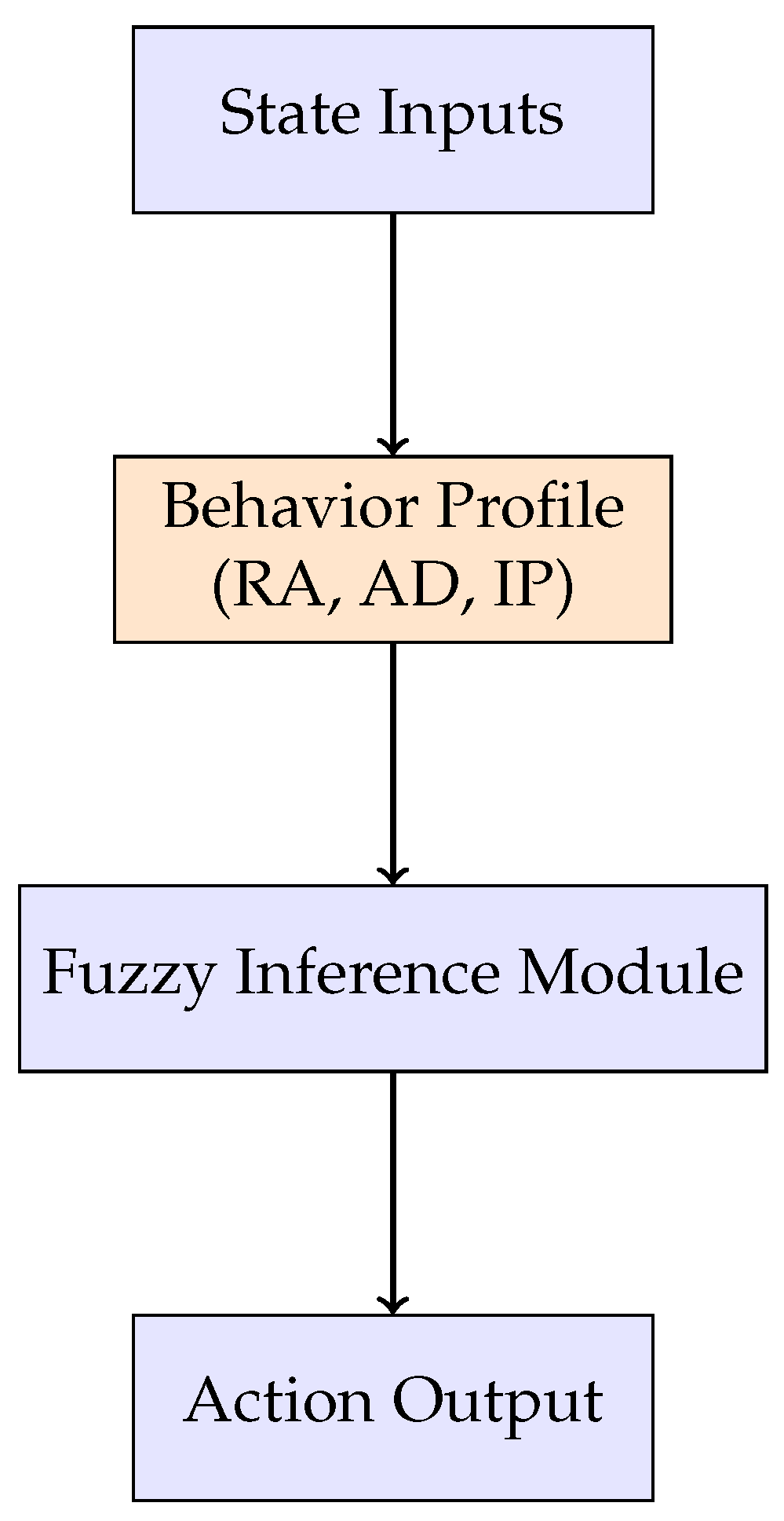

Figure 1 illustrates the internal structure of a behaviorally guided fuzzy agent.

4.3. Fuzzy Inference Pipeline

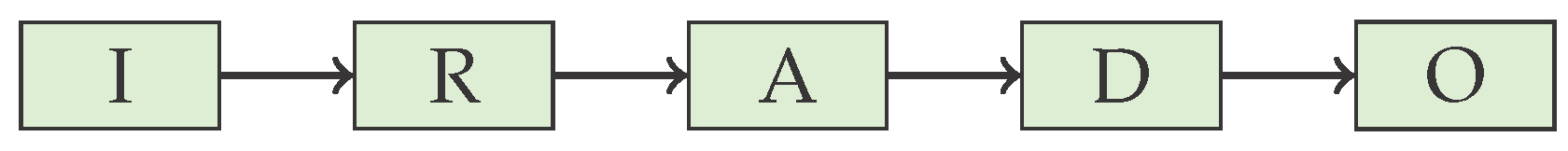

Each agent processes inputs through a fuzzy decision pipeline as illustrated in

Figure 2. The behavioral traits dynamically adjust how inputs are fuzzified and how rules are prioritized.

4.4. Modifying Inference with Behavior

Behavior profiles influence:

Membership Scaling: Alters the shape or threshold of input functions.

Rule Weights: Emphasizes or de-emphasizes certain “if-then” rules.

Output Biasing: Adds weighting to crisp output to simulate urgency preference.

By combining fuzzy reasoning with behavior modulation, agents display decision diversity that mirrors human managers in complex supply networks.

4.5. Summary

This design enables a modular and extensible AI agent framework. It allows for easy integration of psychological or operational traits, supporting simulations that not only optimize logistics outcomes but also explore decision dynamics under varied human-like conditions.

5. Rule Generation and Action Mapping

A central component of any fuzzy system is its rule base—the set of “if-then” statements that map combinations of input conditions to output actions. In this section, we describe how rules are defined, generated, and adapted in our behavioral fuzzy decision agents.

5.1. Rule Structure and Semantics

Each rule encodes a conditional decision policy based on fuzzy input variables. A typical rule follows this structure:

IF Inventory is Low AND Demand Volatility is High THEN Urgency is High

Linguistic modifiers (e.g., “Low”, “High”) correspond to fuzzy sets defined over the universe of discourse for each input variable. The output variable (e.g., Urgency) is also a fuzzy set, which is later defuzzified to produce an action scalar.

5.2. Rule Base Construction

Rules are generated using a mix of domain expertise and automated techniques:

Manual encoding: Experts define rules based on operational best practices and intuitive heuristics.

Combinatorial enumeration: All combinations of linguistic terms across inputs are exhaustively considered, and only feasible rules are retained.

Behavioral filters: Agents with specific traits (e.g., risk-averse) deactivate or modify rules that conflict with their profile.

Each rule is assigned a confidence weight that determines its influence during aggregation. These weights are adjusted during tuning or training.

5.3. Rule Prioritization with Behavior Profiles

Behavioral traits such as Risk Aversion (RA) and Information Preference (IP) are used to scale rule weights before inference. For instance:

This mechanism allows the same fuzzy rule base to produce different outcomes across agents based on individual profiles.

5.4. Output Mapping and Action Execution

After inference and defuzzification (see

Section 3), the final crisp urgency score is mapped to one of several discrete action categories:

Score < 0.3: No action (Defer)

Score 0.3–0.6: Normal order

Score > 0.6: Expedited order

This piecewise mapping converts continuous urgency estimates into operationally executable commands. Alternatively, the urgency score can be used directly to modulate order quantity, shipment size, or supplier prioritization in a continuous decision model.

5.5. Adaptation and Learning

Although our current rule base is manually curated and behaviorally adjusted, future extensions could involve:

Reinforcement learning: Use agent rewards to adjust rule weights or prune ineffective rules.

Evolutionary optimization: Apply genetic algorithms to evolve rule sets across simulation generations.

Data-driven synthesis: Generate fuzzy rules from historical supply chain datasets via clustering or supervised learning.

5.6. Summary

Rule generation and action mapping form the operational core of our fuzzy behavioral agents. By decoupling logical reasoning from execution mechanics, and layering behavioral modulation atop that, the system supports flexible, explainable, and customizable decision logic for adaptive supply chain analytics.

6. Conclusions and Future Applications

This paper has presented a fuzzy behavioral AI framework that effectively addresses the need for adaptive, interpretable decision-making in supply chain systems. The approach is academically grounded and practically significant, demonstrating how fuzzy logic can enable intelligent agents to exhibit context-aware behaviors in dynamic operational environments. By embedding these agents within a simulated supply chain environment, we demonstrated how behaviorally guided logic can improve responsiveness, explainability, and adaptability over traditional rule-based systems.

The system architecture supports modular fuzzy controllers at each node of the supply chain, incorporating real-time state inputs and qualitative traits like risk aversion, adaptability, and information preference. This integration enables diverse decision styles across agents, allowing researchers and practitioners to simulate and analyze a wide spectrum of operational behaviors.

We detailed the underlying fuzzy logic mechanisms—membership functions, rule bases, inference, and defuzzification—as well as the influence of behavioral traits on rule prioritization and output mapping. Our methodology offers a transparent and flexible platform that balances computational decision-making with human-like adaptability.

6.1. Key Contributions

The major contributions of our work are as follows:

A novel hybrid framework that integrates fuzzy logic with behavioral traits for supply chain decision agents.

A simulation environment with adjustable volatility, delays, and behavioral configurations for scenario testing.

Mechanisms for dynamically prioritizing fuzzy rules based on agent personality profiles.

Modular action mapping strategies that convert fuzzy outputs into real-world logistics decisions.

6.2. Future Work

Several promising directions emerge from this research:

Real-World Integration: Deploy the framework in digital twin systems for real-time logistics operations, enabling behavior-aware automation.

Behavioral Cloning: Learn rule profiles from actual human operator data using inverse reinforcement learning or supervised behavioral cloning.

Hybrid AI Models: Integrate fuzzy logic with reinforcement learning to allow adaptive rule tuning based on performance feedback.

Explainable AI (XAI): Further enhance the interpretability of agent decisions using visual and textual explanations derived from fuzzy trace reasoning.

Field Validation: Conduct real-world case studies to validate the practical effectiveness and operational relevance of the proposed fuzzy behavioral framework in diverse supply chain contexts.

6.3. Final Remarks

As supply chains become more complex and dynamic, the demand for AI systems that are not only intelligent but also interpretable and human-aligned continues to grow. Fuzzy behavioral models provide a viable pathway for bridging the gap between rigid optimization and flexible, human-like reasoning. Our framework lays the groundwork for future supply chain decision systems that are simultaneously adaptive, explainable, and operationally robust.

References

- Christopher, M. Logistics & supply chain management; Pearson UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffi, Y. Building a resilient supply chain. Harvard Business Review 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Simchi-Levi, D.; et al. Logic of logistics: theory, algorithms, and applications for logistics and supply chain management; Springer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, D. Artificial intelligence in supply chain management: Theory and applications. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 58, 3365–3377. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy logic = computing with words. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 1996, 4, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, D. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI); Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).