Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

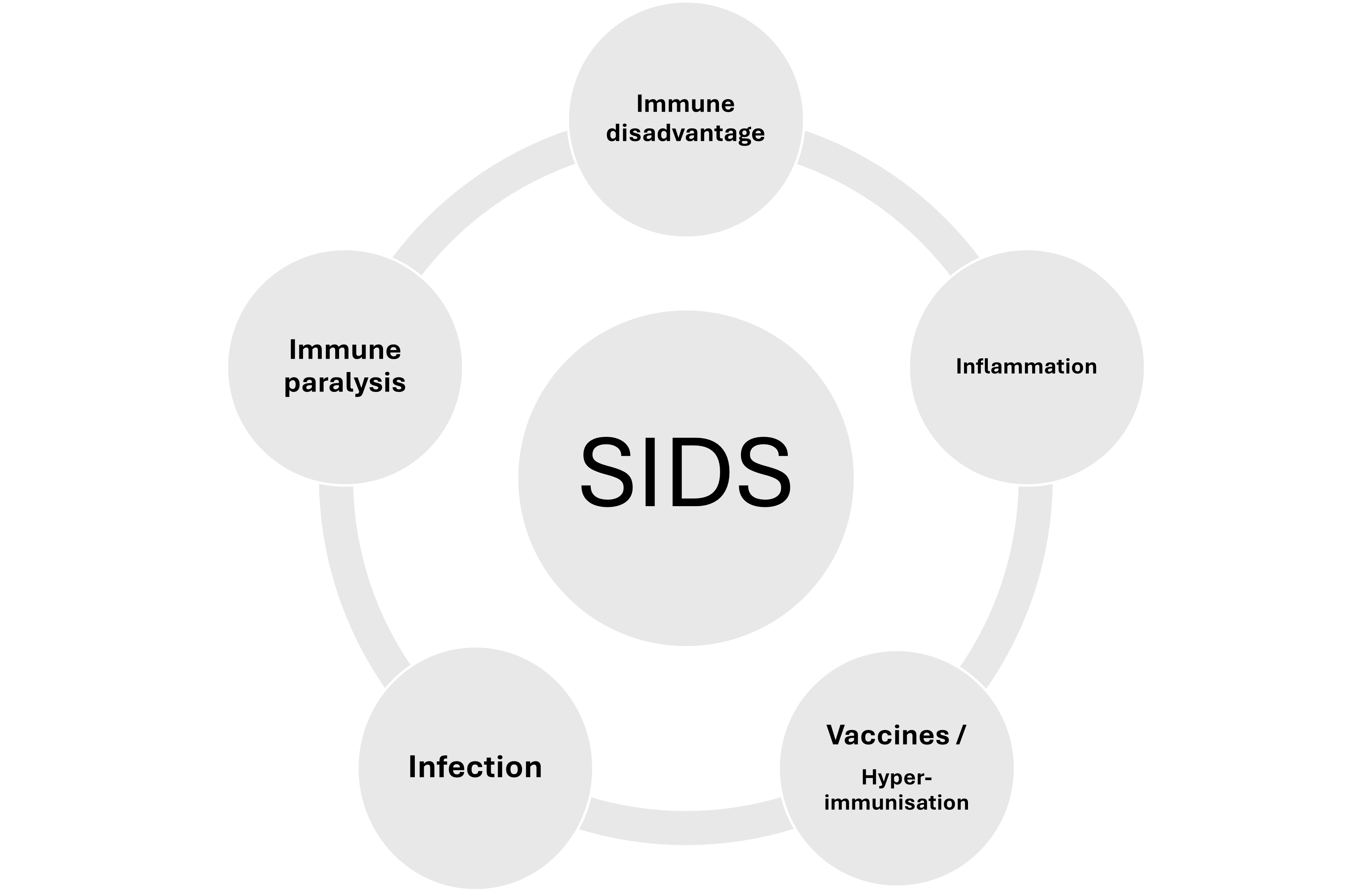

Within Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) resides several primary phenomena; these include a state of immune immaturity, susceptibility to infection, and an inflammatory state. Most SIDS risk factors pertain in some way or another to higher risk of infection (prematurity, lack of breastfeeding, low or absent transplacental antibody, ethnicity, genetics, risky gene polymorphisms, poverty, etc.). Most SIDS cases display evidence of an inflammatory state (raised inflammatory markers and inflammatory cytokines). The pattern of inflammation is very similar to that observed following vaccination, which for achieving successful levels of protective immunity requires components that induce high reactogenicity. It is this reactogenicity which, under certain circumstances can cause immune paralysis. Immune paralysis leaves a vulnerable infant open to infection and systemic inflammatory response syndrome leading to shock. Such a mechanism is explored in this rapid review in the context of the aetiopathogenesis of SIDS.

Keywords:

- Could Immune Disadvantage, Inflammation and hyperimmunization lead to SIDS?

- Most infants receive multiple (≥69) vaccine antigens and reactogenic adjuvants in the first year of life; this antigen/adjuvant load could act as hyperimmunization in vulnerable infants.

- Hyperimmunization is known to cause immune paralysis.

- Immune paralysis therefore could be a pathway to SIDS.

1. Introduction and Background

2. Extending the Infection Hypothesis

3. Hyperimmunization

4. The Role of Inflammation

5. Immune Paralysis (Immunoparalysis)

6. Mechanisms Involved in Immunoparalysis

7. Evidence of a Sepsis-Like Process in SIDS

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Krous, H.F.; Beckwith, J,B.l Byard, R.W.; Rognum, T.O.; Bajanowski, T.; Corey, T.; Cutz, E.; Hanzlick, R.; Keens, T.G. Mitchell EA. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics. 2004, 114(1), 234–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Mendoza, Carrie K.; Palusci, Vincent J.; Hoffman, Benjamin; Batra, Erich; Yester, Marc; Corey, Tracey S.; Sens, Mary Ann. Aap Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Council On Child Abuse And Neglect, Council On Injury, Violence, And Poison Prevention, Section On Child Death Review And Prevention, National Association Of Medical Examiners. "Half century since SIDS: a reappraisal of terminology. Pediatrics 2021, 148(no. 4), e2021053746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, C.; Moscovis, S.; Hall, S.; Burns, C.; Scott, R. J. Exploring the risk factors for sudden infant deaths and their role in inflammatory responses to infection. Frontiers in immunology 6, 44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blood-Siegfried, J. The role of infection and inflammation in sudden infant death syndrome. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2009, 31(4), 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N. Infection: the neglected paradigm in SIDS research. Arch Dis Child 2017, 102, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiano, J.J.; Kinney, H.C. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model. Biol. Neonate 1994, 65, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.A. The common bacterial toxins hypothesis of sudden infant death syndrome. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999, 25(1-2), 11–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, P.M. Inflammation in sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatric Research 2024, 95, 885–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.W.; Blackwell, C.C. Sudden infant death syndrome, virus infections and cytokines. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999, 25, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdal, S.H.; Stray-Pedersen, A.; Eidahl, J.M.; Vege, Å.; Ferrante, L.; Rognum, T.O. The vicious spiral in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Front Pediatr 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guare, E.G.; Zhao, R.; Ssentongo, P.; Batra, E.K.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Paules, C.I. Rates of sudden unexpected infant death before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA network open 2024, 7(9), e2435722–e2435722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro-Mendoza, C.K.; Woodworth, K.R.; Cottengim, C.R.; Erck Lambert, A.B.; Harvey, E.M.; Monsour, M.; Parks, S.E.; Barfield, W.D. Sudden unexpected infant deaths: 2015–2020. Pediatrics 2023, 151(4), e2022058820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pease, A.; Turner, N.; Ingram, J.; Fleming, P.; Patrick, K.; Williams, T.; Sleap, V.; Pitts, K.; Luyt, K.; Ali, B.; Blair, P. Changes in background characteristics and risk factors among SIDS infants in England: cohort comparisons from 1993 to 2020. BMJ open 2023, 13(10), e076751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, L.; Opdal, S.H.; Byard, R.W. Further Exploration of the Influence of Immune Proteins in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Acta Paediatrica 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.S.; Okaty, B.W.; Riehs, M.; Wapniarski, A.; Hershey, D.; Harb, H.; Zia, M.; Haas, E.A.; Alexandrescu, S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Vargas, S.O. Multiomic analysis of neuroinflammation and occult infection in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA neurology 2024, 81(3), 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, A.R.; Berry, A.M.; Bettelheim, K.A.; Goldwater, P.N. Gut microbiome in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) differs from that in healthy comparison babies and offers an explanation for the risk factor of prone position. Int J Med Microbiol 2014, 304(5-6), 735–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N. SIDS, prone sleep position and infection: An overlooked epidemiological link in current SIDS research? Key evidence for the “Infection Hypothesis”. Medical Hypotheses 2020, 144, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N. Insights from twin Sudden Infant Death Syndrome studies could reveal an aetiopathogenetic pathway to sudden infant death through immunopathology. Med Res Arch. 2025, 13(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, G.S.; Miller, N.Z. Reaffirming a Positive Correlation Between Number of Vaccine Doses and Infant Mortality Rates: A Response to Critics. Cureus 2023, 15(2), e34566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.Z. Vaccines and sudden infant death: An analysis of the VAERS database 1990–2019 and review of the medical literature. Toxicol Reports 2021, 8, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, NZ; Goldman, S. : Infant mortality rates regressed against number of vaccine doses routinely given: Is there a biochemical or synergistic toxicity? Hum Exp Toxicol 2011, 30, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonowski, K.; Hooke, r B. Adverse outcomes are increased with exposure to added combinations of infant vaccines. Int J Vaccine Theor Pract Res. 2024, 3, 1103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennemann, M.M.T.; Höffgen, M.; Bajanowski, T.; Hense, H.W.; Mitchell, E.A. Do immunisations reduce the risk for SIDS? A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2007, 25(26), 4875–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Nordhorn, J.; Hettler-Chen, C.M.; Keil, T.; Muckelbauer, R. Association between sudden infant death syndrome and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunisation: an ecological study. BMC Pediatrics 2015, 15(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, J.M.; Hull, B.P.; Hayen, A.; Gidding, H.F.; Burgess, M.A. Probability of coincident vaccination in the 24 or 48 hours preceding sudden infant death syndrome death in Australia. Pediatrics 2005, 115(6), e643–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchi, M.; Ball, H.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Robertson, N. Interpretation of vaccine associated neurological adverse events: a methodological and historical review. J Neurol 2022, 269(1), 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W. Methodological issues in research on developmental exposure to neurotoxic agents. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005, 27, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenoni, C. Toxische Amyloidosis bei der anti-diphtherischen Immunization des Pferdes. Zbl. Allg. Path 1902, 13, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.Z.; Goldman, S. Infant mortality rates regressed against number of vaccine doses routinely given: Is there a biochemical or synergistic toxicity? Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011, 30, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, B.S.; Miller, N.Z. Analysis of health outcomes in vaccinated and unvaccinated children: Developmental delays, asthma, ear infections and gastrointestinal disorders. SAGE Open Medicine 2020, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, P.; Jensen, H.; Rodrigues, A.; Garly, M.L.; Benn, C.S.; Lisse, I.M.; Simondon, F. Divergent female–male mortality ratios associated with different routine vaccinations among female–male twin pairs. Int J Epidemiol 2004, 33(2), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, P.; Jensen, H.; Gomes, J.; Fernandes, M.; Lisse, I.M. The introduction of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine and child mortality in rural Guinea-Bissau: an observational study. Int J Epidemiol 2004, 33(2), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovsky, N. Comparative Safety of Vaccine Adjuvants: A Summary of Current Evidence and Future Needs. Drug Saf. 38, 1059–1074. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovsky, N.; Aguilar, J.C. Vaccine adjuvants: current state and future trends. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004, 82(5), 488–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.S.; Andrianov, A.K.; Fusco, P.C. Polyionic vaccine adjuvants: another look at aluminum salts and polyelectrolytes. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2015, 4(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcyrous, M.; Korones, S.B.; Crouse, D.; Bada, HS. Interleukin-6, C-Reactive Protein, and Abnormal Cardiorespiratory Responses to Immunization in Premature Infants. Pediatrics 1998, 101(3), E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jmaa, W.B.; Hernandez, A.I.; Sutherland, M.R.; Cloutier, A.; Germain, N.; Lachance, C.; Martin, B.; Lebel, M.H.; Pladys, P.; Nuyt, A.M. Cardio-respiratory events and inflammatory response after primary immunization in preterm infants<32 weeks gestational age: a randomized controlled study. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2017, 36(10), 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, N.; Cao, R.G.; Bunsow, E.; Nehar-Belaid, D.; Marches, R.; Xu, Z.; Smith, B.; Heinonen, S.; Mertz, S.; Leber, A.; Smits, G. Young infants display heterogeneous serological responses and extensive but reversible transcriptional changes following initial immunizations. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcyrous, M.; Korones, S.B.; Arheart, K.L.; Bada, H.S. Primary immunization of premature infants with gestational age <35 weeks: cardiorespiratory complications and C-reactive protein responses associated with administration of single and multiple separate vaccines simultaneously. J Pediatr. 2007, 151(2), 167–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.Q.; Zhu, B.L.; Ishida, K.; Quan, L.; Oritani, S.; Maeda, H. Serum C-reactive protein levels in postmortem blood—an analysis with special reference to the cause of death and survival time. Forensic science international 2002, 130(2-3), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlin-Hansen, L. C-reactive protein (CRP), a comparison of pre- and post-mortem blood. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 124, 32–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Beer, C.; Ayele, B.T.; Dempers, J. Immune biomarkers as an adjunct diagnostic modality of infection in cases of sudden and unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) at Tygerberg Medico-legal Mortuary, Cape Town, South Africa. Human Pathology: Case Reports 2021, 23, 200477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, S.; Kamushaaga, Z.; Nash, S.B.; Elliott, A.M.; Dockrell, H.M.; Cose, S. Post-immunization leucocytosis and its implications for the management of febrile infants. Vaccine 2018, 36(20), 2870–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, A.E.; Drakesmith, H.; Frost, J.N. Adaptive immunity and vaccination–iron in the spotlight. Immunotherapy Advances 2021, 1(1), ltab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Kries, R.; Toschke, A.M.; Straßburger, K.; Kundi, M.; Kalies, H.; Nennstiel, U.; Jorch, G.; Rosenbauer, J.; Giani, G. Sudden and unexpected deaths after the administration of hexavalent vaccines (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, Haemophilius influenzae type b): is there a signal? European journal of pediatrics 2005, 164(2), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinka, B.; Rauch, E.; Buettner, A.; Rueff, F.; Penning, R. Unexplained cases of sudden infant death shortly after hexavalent vaccination. Vaccine 2006, 24(31-32), 5779–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T. An Inflammatory Response Is Essential for the Development of Adaptive Immunity-Immunogenicity Immunotoxicity. Vaccine 2016, 34(47), 5815–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T. Causal Relationship Between Immunological Responses and Adverse Reactions Following Vaccination. Vaccine 2019, 37(2), 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, Y.; Maeda, M.; Kawashima, H.; Nakayama, T. Inflammatory Responses Following Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Immunization With Aluminum-Adjuvanted or Non-Adjuvanted Vaccines. Vaccine 2014, 32(27), 3393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.M.; Porter, K.; Karlsson, E.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Proinflammatory cytokine responses correspond with subjective side effects after influenza virus vaccination. Vaccine 2015, 33(29), 3360–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.L.; Lin, Z.J.; Bi, Z.F.; Qiu, L.X.; Hu, F.F.; Liu, X.H.; Lin, B.Z.; Su, Y.Y.; Pan, H.R.; Zhang, T.Y.; Huang, S.J. Inflammation-related adverse reactions following vaccination potentially indicate a stronger immune response. Emerging microbes & infections 2021, 10(1), 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Halsey, N.A.; Omer, S.B.; Orenstein, W.A.; T O'Leary, S.; Limaye, R.J.; Salmon, D.A. The state of vaccine safety science: systematic reviews of the evidence. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020, 20(5), e80–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblatt, A.E.; Stein, S.L. Cutaneous Reactions to Vaccinations. Clinics in Dermatology 2015, 33(3), 327–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Kamoi, K.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Ocular inflammation post-vaccination. Vaccines 2023, 11(10), 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panozzo, C.A.; Pourmalek, F.; Pernus, Y.B.; Pileggi, G.S.; Woerner, A.; Bonhoeffer, J. Brighton Collaboration Aseptic Arthritis Working Group. Arthritis and arthralgia as an adverse event following immunization: a systematic literature review. Vaccine 2019, 37(2), 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakou, A.I.; Tsantes, A.G.; Routsi, E.; Agiasofitou, E.; Kalamata, M.; Bompou, E.K.; Tsante, K.A.; Vladeni, S.; Chatzidimitriou, E.; Kotsafti, O.; Samonis, G. Could Vaccination against COVID-19 Trigger Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases? Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13(16), 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukaj, S.; Sitna, M.; Sitko, K. The Impact of the mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine on the Th-Like Cytokine Profile in Individuals With No History of COVID-19: Insights Into Autoimmunity Targeting Heat Shock Proteins. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1549739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayass, M.A.; Tripathi, T.; Zhu, K.; Nair, R.R.; Melendez, K.; Zhang, J.; Fatemi, S.; Okyay, T.; Griko, N.; Ghelan, M.B.; Pashkov, V. T helper (Th) cell profiles and cytokines/chemokines in characterization, treatment, and monitoring of autoimmune diseases. Methods 2023, 220, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyeler, S.A.; Hodges, M.R. Adrianne, G.; Huxtable, A.G. Impact of inflammation on developing respiratory control networks: rhythm generation, chemoreception and plasticity. Resp PhysiolNeurobiol 2020, 274, 103357. [CrossRef]

- Jawdeh, E.G.A.; Huang, H.; Westgate, P.M.; Patwardhan, A.; Bada, H.; Bauer, J.A.; Giannone, P. Intermittent hypoxemia in preterm infants: a potential proinflammatory process. American journal of perinatology 2021, 38(12), 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, B.A.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Langereis, J.D.; Aaby, P.; van Crevel, R.; Benn, C.S.; Netea, M.G. Interacting, Nonspecific, Immunological Effects of Bacille Calmette-Guérin and Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis Inactivated Polio Vaccinations: An Explorative, Randomized Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 70(3), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, N.L.; Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The Impact of Vaccines on Heterologous Adaptive Immunity. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019, 25(12), 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmoeckel, K.; Mrochen, D.M.; Hühn, J.; Pötschke, C.; Bröker, B.M. Polymicrobial Sepsis and Non-Specific Immunization Induce Adaptive Immunosuppression to a Similar Degree. PloS One 2018, 13(2), e0192197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.A.; Henderson, A.J.; Dow, S.W. Suppression of Vaccine Immunity by Inflammatory Monocytes. J Immunol. 2012, 189(12), 5612–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.M.; Herwanto, V.; McLean, A.S. Immune Paralysis in Sepsis: Recent Insights and Future Development. In Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine; Vincent, J.-L., Ed.; Springer Chamhttps, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.W.; Greathouse, K.C.; Thakkar, R.K.; Sribnick, E.A.; Muszynski, J.A. Immunoparalysis in pediatric critical care. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2017, 64(5), 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.L.; Amaral, M.N.G.A.; da Silva, S.F.D.; Silva, I.M.M.; Laranjeira, P.M.D.S.; Pinto, C.R.D.J.; Paiva, A.A.; Dias, A.S.D.S.; Coelho, M.L.A.C.V. Immunoparalysis in critically ill children. Immunology 2023, 168(4), 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.H.; Shadley, J.D.; Halligan, N.L.; Hall, M.W.; Popova, A.P.; Quasney, M.W.; Dahmer, M.K. Differences in the Genomic Profiles of Immunoparalyzed and Nonimmunoparalyzed Children With Sepsis: A Pilot Study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2022, 23(2), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.L.; Zhang, D.; Bush, J.; Graham, K.; Starr, J.; Murray, J.; Tuluc, F.; Henrickson, S.; Deutschman, C.S.; Becker, L.; McGowan, F.X., Jr. Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with an immune paralysis phenotype in pediatric sepsis. Shock 2020, 54(3), 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Yang, Y.; Okiji, T.; Azuma, M.; Nagai, S. Polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived cells that contribute to the immune paralysis are generated in the early phase of sepsis via PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Infection and Immunity 2021, 89(6), e00771-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.C.; Khodadadi, H.; Malik, A.; Davidson, B.; Salles, É.D.S.L.; Bhatia, J.; Hale, V.L.; Baban, B. Innate immunity of neonates and infants. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M. Maternal Antibodies and Infant Immune Responses to Vaccines. Vaccine 2015, 33(47), 6469–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.C.; Grodzin, C.J.; Balk, R.A. Sepsis: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest 1997, 112, 235–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.C. Toward a theory regarding the pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: what we do and do not know about cytokine regulation. Crit Care Med. 1996, 24, 163–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muenzer, J.T.; Davis, C.G.; Chang, K.; Schmidt, R.E.; Dunne, W.M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S. Characterization and modulation of the immunosuppressive phase of sepsis. Infection and immunity 2010, 78(4), 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Nicholson, D.W. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006, 6, 813–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneret, G.; Debard, A.L.; Venet, F.; Bohe, J.; Hequet, O.; Bienvenu, J.; Lepape, A. Marked elevation of human circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. Critical care medicine 2003, 31(7), 2068–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravia, J.; Chapman, N.M.; Sun, Y.; Meng, X.; Risch, I.; Li, W.; Guy, C.; Shi, H.; Hu, H.; Dhungana, Y.; Li, J. Mitochondrial and lysosomal signaling orchestrates heterogeneous metabolic states of regulatory T cells. Science Immunology 2025, 10(112), eads9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomer, J.S.; Green, J.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S. The changing immune system in sepsis: is individualized immuno-modulatory therapy the answer? Virulence 2014, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, T.; Rosenhagen, C.; Hornig, I.; Schmidt, K.; Lichtenstern, C.; Mieth, M.; Bruckner, T.; Martin, E.; Schnitzler, P.; Hofer, S.; Weigand, M.A. Viral infections in septic shock (VISS-trial)–crosslinks between inflammation and immunosuppression. Journal of Surgical Research 2012, 176(2), 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.J.; Prescott, H.C. Sepsis and Septic Shock. The New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 391(22), 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomer, J.S.; To, K.; Chang, K.C.; Takasu, O.; Osborne, D.F.; Walton, A.H.; Bricker, T.L.; Jarman, S.D.; Kreisel, D.; Krupnick, A.S.; Srivastava, A. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. Jama 2011, 306(23), 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, L.; Rognum, T.O.; Vege, A.; Nygard, S.; Opdal, S.H. Altered gene expression and possible immunodeficiency in cases of sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2016, 80(1), 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, R.Y.; Horne, R.S.; Hauck, F.R. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Lancet 2007, 370(9598), 1578–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rognum, I.J.; Haynes, R.L.; Vege, Ǻ.; Yang, M.; Rognum, T.O.; Kinney, H.C. Interleukin-6 and the serotonergic system of the medulla oblongata in the sudden infant death syndrome. Acta neuropathologica 2009, 118(4), 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, L.; Opdal, S.H.; Byard, R.W. Understanding the Immune Profile of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome - Proteomic Perspectives. Acta Paediatrica 2024, 113(2), 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendrick, N.; Drucker, D.B.; Morris, J.A.; Telford, D.R.; Barson, A.J.; Oppenheim, B.A.; Crawley, B.A.; Gibbs, A. Bacterial toxins: a possible cause of cot death. Journal of clinical pathology 1992, 45(1), 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.A.; Klein, N.J.; Hartley, J.C.; Lock, P.E.; Malone, M.; Sebire, N.J. Infection and sudden unexpected death in infancy: a systematic retrospective case review. The Lancet 2008, 371(9627), 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N. Sterile Site Infection at Autopsy in Sudden Unexpected Deaths in Infancy. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2009, 94(4), 303–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, A.R.; Berry, A.M.; Goldwater, P.N. Novel Hypothesis for Unexplained Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI). Archi Dis Child. 2009, 94(11), 841–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Poets, C.F.; Meny, R.G.; Chobanian, M.R.; Bonofiglo, R.E. Gasping and other cardiorespiratory patterns during sudden infant deaths. Pediatric research 1999, 45(3), 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Ariagno, R.; Souquet, M.; Dement, W.C. Abnormal Polygraphic Findings in Near-Miss Sudden Infant Death. Lancet 1976, 1(7973), 1326–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.Y.; Carlin, R.F.; Hand, I. Evidence Base for 2022 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment to Reduce the Risk of Sleep-Related Infant De McGaffey aths. Pediatrics 2022, 150(1), e2022057991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaffey, H.L. Am J Clin Pathol 1968, 50, 615.

- McGaffey, H.L. Crib death: metabolic disturbances reflected in laboratory studies. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970, 54, 70. [Google Scholar]

- MacReady, N. SIDS may have a previously unsuspected pathogenesis. American Society for Clinical Pathology 2006 Annual Meeting, October 23, 2006. 5. [Google Scholar]

- McGaffey, H.L. Am J Clin Pathol Abstract 34 2006, 126, 636.

- Goldwater, P.N.; Gebien, D.J. Metabolic acidosis and sudden infant death syndrome: overlooked data provides insight into SIDS pathogenesis. World J Pediatr 2025, 21, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Normeshie, C.; Keene, K.L.; Hauck, F.R. Organ Weights and Length Anthropometry Measures at Autopsy for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Cases and Other Infant Deaths in the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Am J Hum Biol. 2024, 36(10), e24126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N.; Kelmanson, I.A.; Little, B.B. Increased Thymus Weight in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Compared to Controls: The Role of Sub-Clinical Infections. Am J Hum Biol. 2021, 33(6), e23528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.B.; Kemp, P.M.; Bost, R.O.; Snell, L.M.; Peterman, M.A. Abnormal Allometric Size of Vital Body Organs Among Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Victims. Am J Hum Biol. 2000, 12(3), 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmanson, I.A. Differences in Somatic and Organ Growth Rates in Infants Who Died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. J Perinat Med. 1992, 20(3), 183–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwater, P.N. Intrathoracic Petechial Hemorrhages in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Other Infant Deaths: Time for Re-examination? Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008, 11(6), 450–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, J.L.; Wong, H. R. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Septic Shock in Neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2010, 37(2), 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariks, J. Diaphragmatic muscle fiber necrosis in SIDS. Forensic Sci Int. 1989, 43, 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, M.M.; Denic, N.; Smith, C.R. Development of the Respiratory Diaphragm in Childhood: Diaphragmatic Contraction Band Necrosis in Sudden Death. Hum Pathol. 1996, 27(1), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.M.; Mathew, M. Autopsy-related histomorphological findings in neonatal sepsis: a narrative review. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2025, 21, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, D.; Preuss, V.; Hagemeier, L.; Radomsky, L.; Beushausen, K.; Keil, J.; Nora, S.; Vennemann, B.; Falk, C.S.; Klintschar, M. Age-related cytokine imbalance in the thymus in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Pediatric Research 2024, 95(4), 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood-Siegfried, J.; Nyska, A.; Geisenhoffer, K.; Lieder, H.; Moomaw, C.; Cobb, K.; Shelton, B.; Coombs, W.; Germolec, D. Alteration in regulation of inflammatory response to influenza a virus and endotoxin in suckling rat pups: a potential relationship to sudden infant death syndrome. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 5–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood-Siegfried, J.; Nyska, A.; Lieder, H.; Joe, M.; Vega, L.; Patterson, R.; Germolec, D. Synergistic effect of influenza a virus on endotoxin-induced mortality in rat pups: a potential model for sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatric research 2002, 52(4), 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, K.S.; Mayer, C.A.; MacFarlane, P.M. A critical postnatal period of heightened vulnerability to lipopolysaccharide. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2016, 232, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajanowski, T.; Ortmann, C.; Hernandez, M.; Freislederer, A.; Brinkmann, B. Reaction patterns in selected lymphatic tissues associated with sudden infant death (SID). Int J Leg Med. 1997, 110, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeye, R.L. Brain-stem and adrenal abnormalities in the sudden-infant-death syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976, 66(3), 526–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, F.M.; Vink, R.; Byard, R.W. Brainstem Neuropathology in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. In SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future;May. Chapter 26; Duncan, JR, Byard, RW, Eds.; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide (AU), 2018; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513396/.

- Fine, P.E.; Williams, T.N.; Aaby, P.; Källander, K.; Moulton, L.H.; Flanagan, K.L.; Smith, P.G.; Benn, C.S. Working Group on Non-specific Effects of Vaccines, Epidemiological studies of the ‘non-specific effects’ of vaccines: I–data collection in observational studies. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2009, 14(9), 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutts, F.T.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Colombo, S.; Bennett, S. Evaluation of factors influencing vaccine uptake in Mozambique. Int J Epidemiol. 1989, 18, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutts, F.T.; Diallo, S.; Zell, E.R.; Rhodes, P. Determinants of vaccination in an urban population in Conakry, Guinea. Int J Epidemiol. 1991, 20, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.E.; Chen, R.T. Confounding in studies of adverse reactions to vaccines. Am J Epidemiol. 1992, 136, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, I.; Aaby, P.; Jensen, H. Routine vaccinations and child survival: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. BMJ. 2000, 321, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, R.F.; Streatfield, P.K.; Phelan, M.; Shifa, N.; Rashid, M.; Yunus, M. Effect of infant immunisation on childhood mortality in rural Bangladesh: analysis of health and demographic surveillance data. The Lancet 2004, 364, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaugelade, J.; Pinchinat, S.; Guiella, G.; Elguero, E.; Simondon, F. Non-specific effects of vaccination on child survival: prospective cohort study in Burkina Faso. BMJ 2004, 329, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, L.H.; Rahmathullah, L.; Halsey, N.A.; Thulasiraj, R.D.; Katz, J.; Tielsch, J.M. Evaluation of non-specific effects of infant immunizations on early infant mortality in a southern Indian population. Trop Med Int Health 2005, 10, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.J.; Moulton, L.H.; Becker, S.; Munoz, A.; Black, R.E. Non-specific effects of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis vaccination on child mortality in Cebu, The Philippines. International journal of epidemiology 2007, 36(5), 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, A.; Floyd, S.; Mwinuka, V.; Mwafilaso, J.; Mwagomba, D.; Mkisi, R.E.; Katsulukuta, A.; Khunga, A.; Crampin, A.C.; Branson, K.; McGrath, N. Ascertainment of childhood vaccination histories in northern Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2008, 13, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, W.; Yang, C.; Lin, W.; Cheng, X.; He, H.; Li, X.; Yu, J. Immunogenicity, Safety, and Protective Efficacy of Mucosal Vaccines Against Respiratory Infectious Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2025, 13(8), 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, E.C.; Ward, R.W. Mucosal Vaccines - Fortifying the Frontiers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022, 22(4), 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotiwala, F.; Upadhyay, A.K. Next Generation Mucosal Vaccine Strategy for Respiratory Pathogens. Vaccines 2023, 11(10), 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mehl, F.; Zeichner, S.L. Vaccine Strategies to Elicit Mucosal Immunity. Vaccines 2024, 12(2), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B. Helicobacter pylori--a Nobel pursuit? Can J Gastroenterol 2008, 22(11), 895–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).