Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Electrode Selection

2.2. Substrate

2.3. Research Apparatus

2.4. Measurement Methodology.

3. Results and Discussion

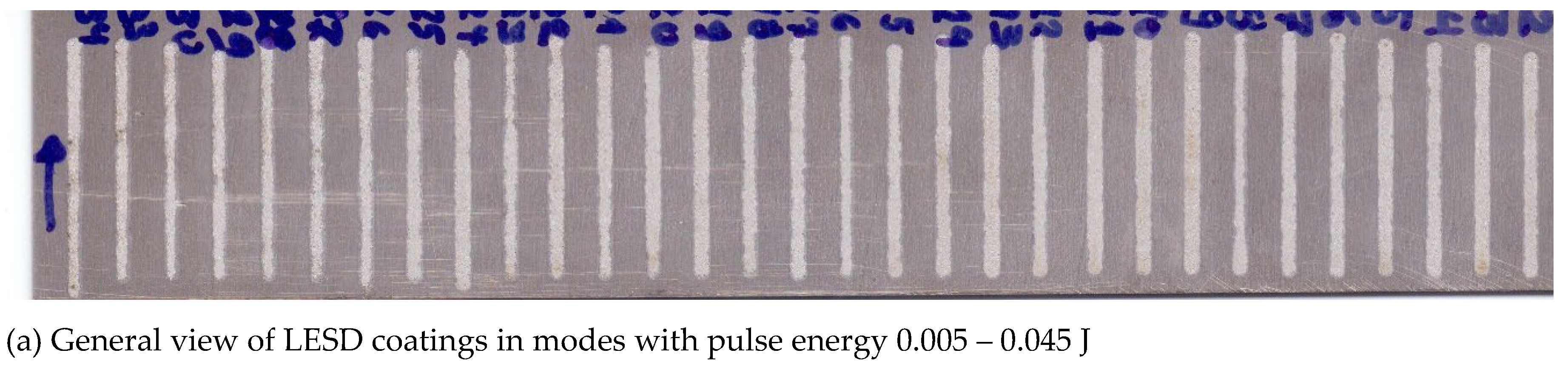

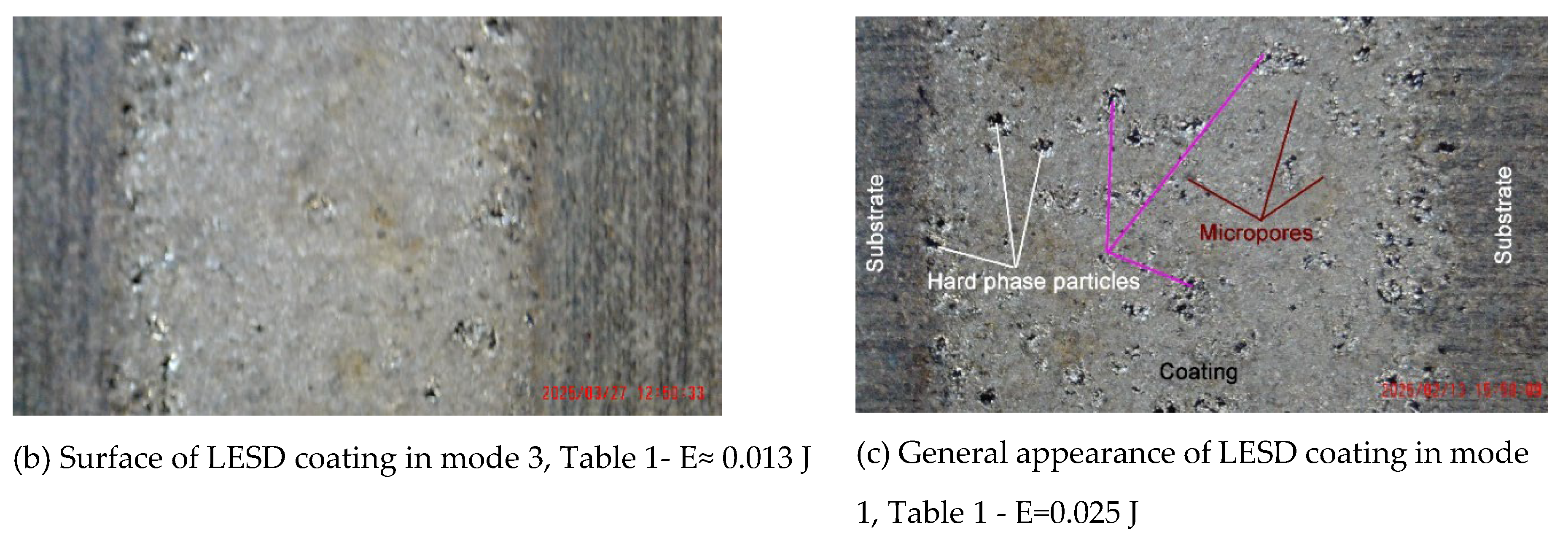

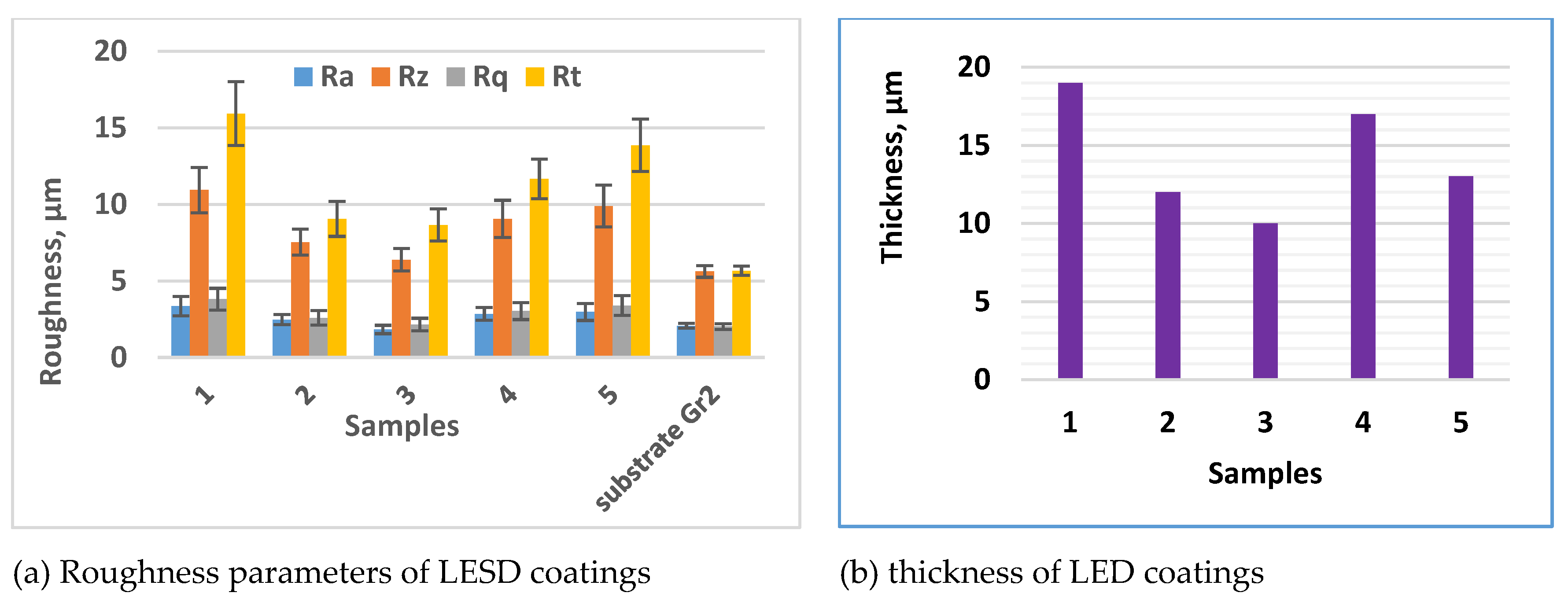

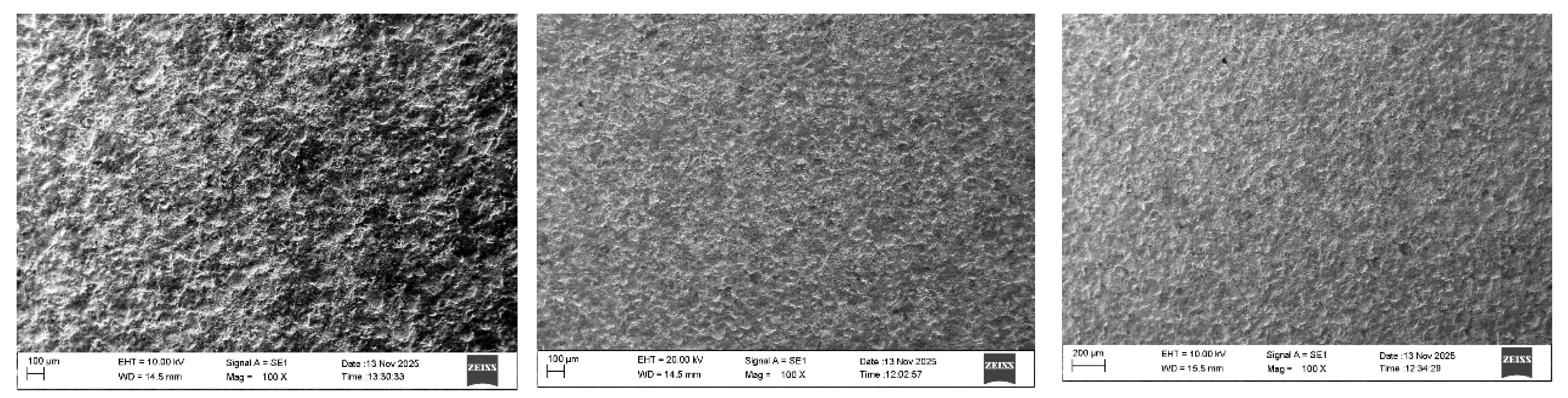

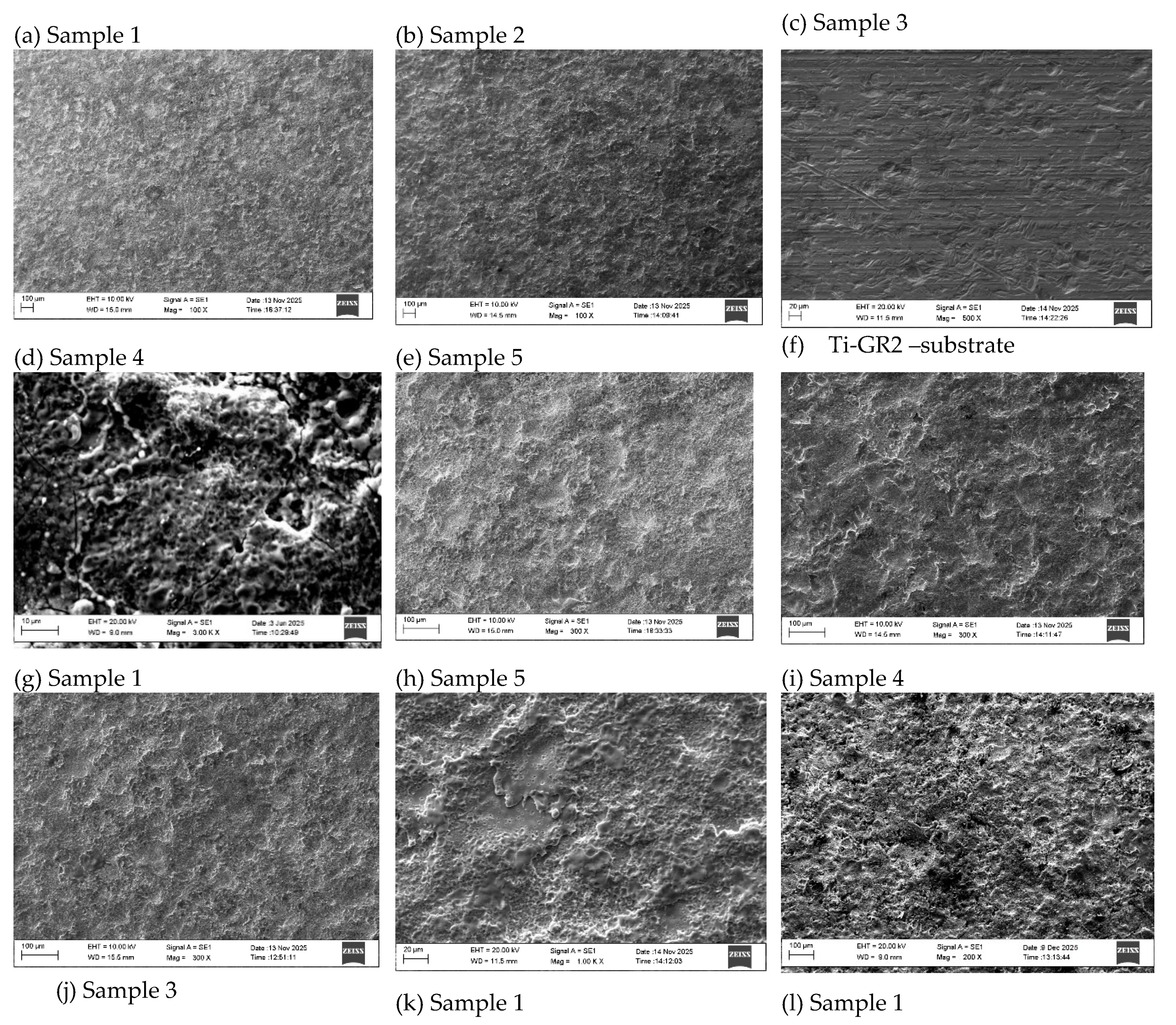

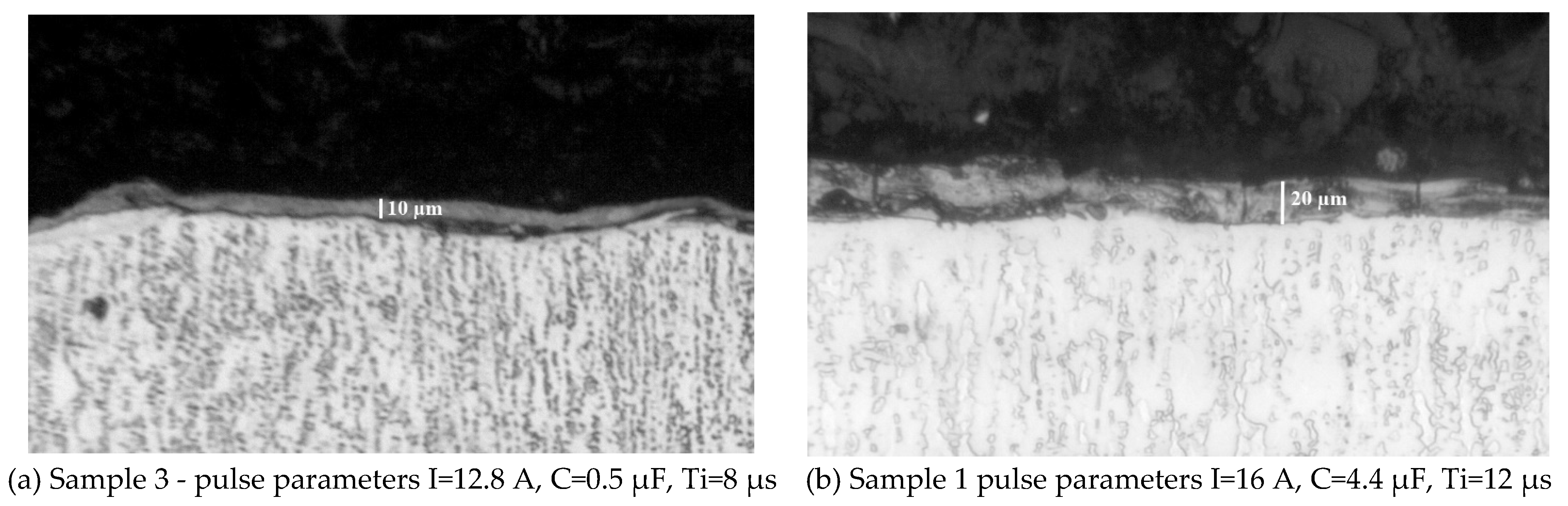

3.1. Coating Characterization – Roughness, Thickness δ, and Structure of Coatings

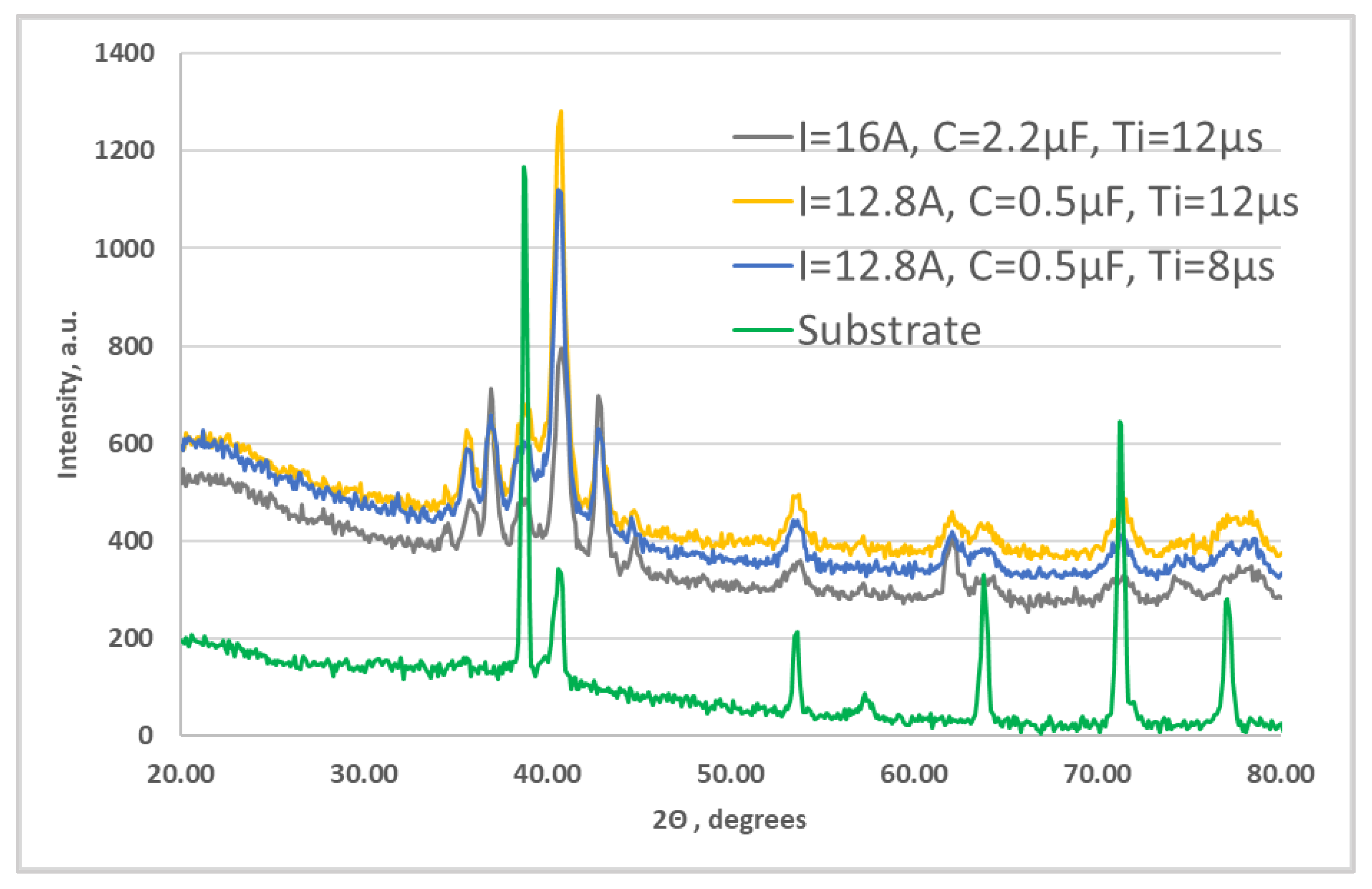

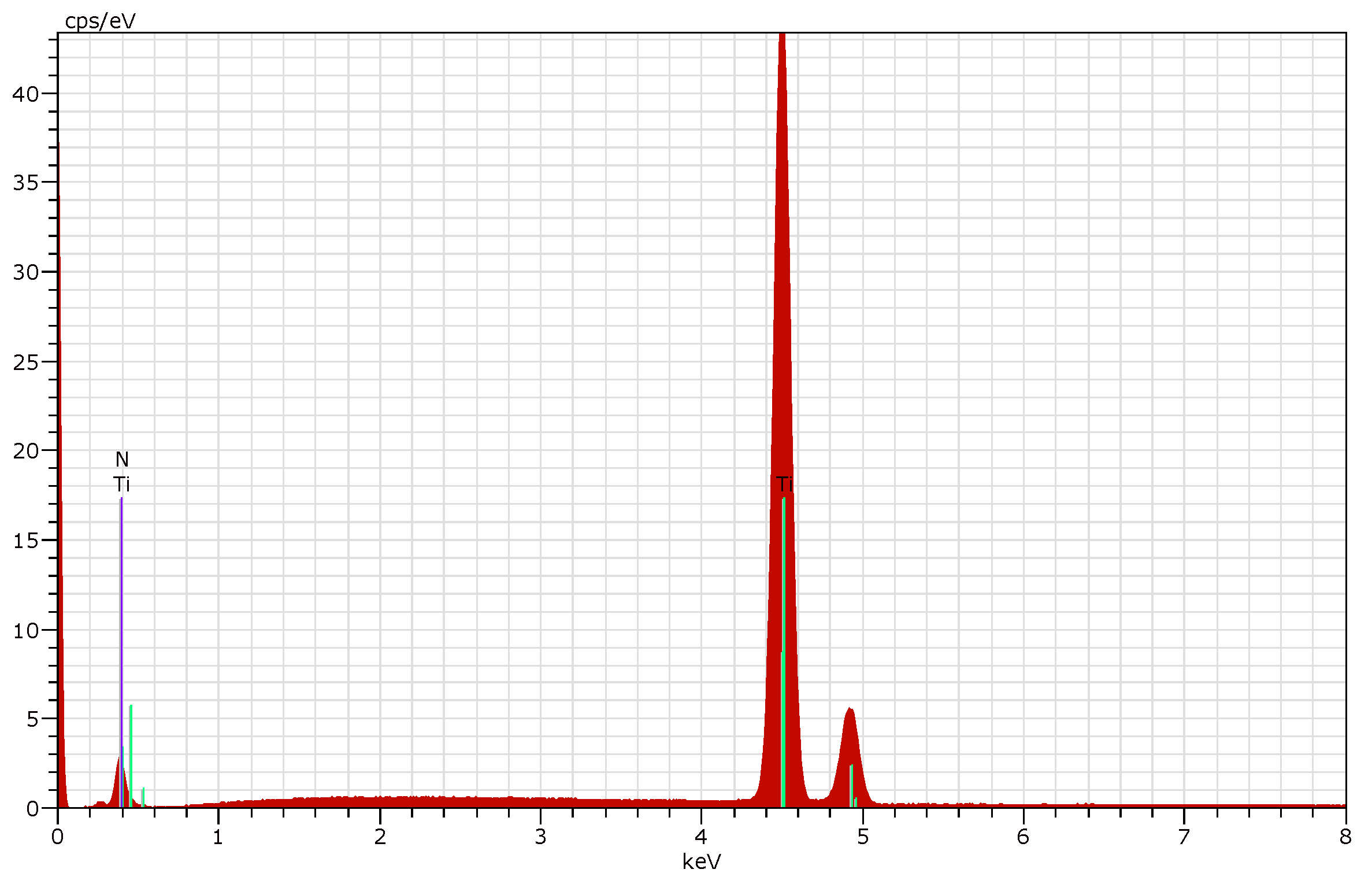

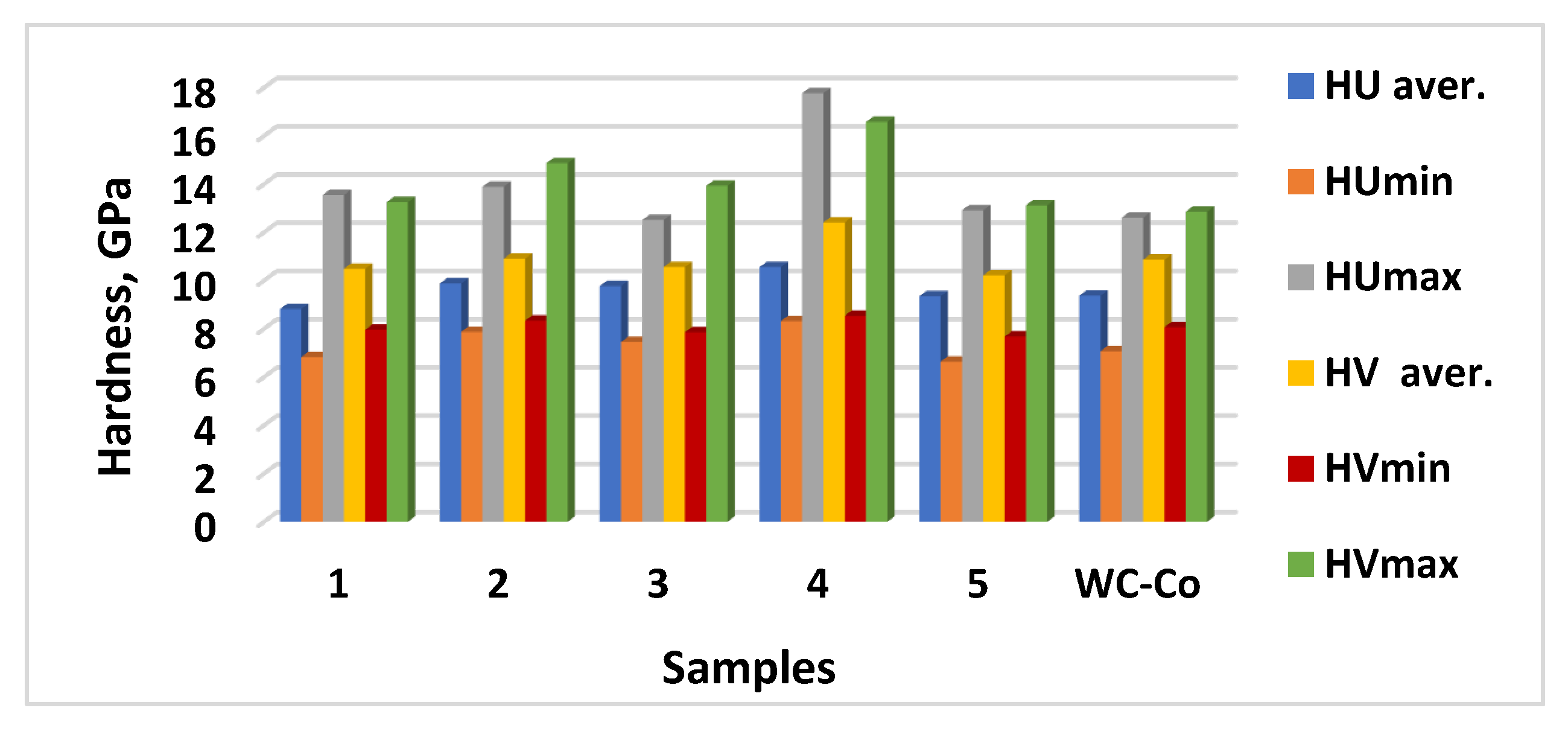

3.2. Phase Composition and Microhardness of the Coatings

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomashov, N.D. Titanium and corrosion-resistant alloys based on it; Publisher: Metallurgy, Russia, 1985. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Leyens, Ch.; Peters, M. Titanium and Titanium Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorynin, I.V.; Chechulin, B.B. Titanium in mechanical engineering; Publisher: Mashinostroenie, Moscow, 1990; in Russian. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.K.; Etri, H.E.; Korkmaz, M.E.; et al. Tribological and Surface Morphological Characteristics of Titanium Alloys: a review. Archiv Civ. Mech. Eng. 2022, 22(72). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.T.; Mathew, J.; Kuriachen, B. Tribology of Ti6Al4V: A review. Friction 2019, 7, 497–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. Tribological properties of titanium-based alloys. In Surface Engineering of Light Alloys; Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, H.; Wiecinski, P.; Ossowski, M.; Ortore, G.; Wierzcho´n, T.; Kurzydłowski, K.J. Surface engineering techniques used for improving the mechanical and tribological properties of the Ti6A14V alloy. Surface & Coating Technology 2008, 202, 2453–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Chen, L.-Y.; Wang, L. Surface Modification of Titanium and Titanium Alloys: Technologies, Developments, and Future Interests. Advanced Engineering Materials 2020, 22(5), 2070017, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarczyk, J.; Batory, D.; Kaczorowski, W.; Pązik, B.; Januszewicz, B.; Burnat, B.; Czerniak-Reczulska, M.; Makówka, M.; Niedzielski, P. Comparison of Different Thermo-Chemical Treatments Methods of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy in Terms of Tribological and Corrosion Properties. Materials 2020, 13(22), 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münz, W.-D.; Lewis, D.B.; Hovsepian, P.E.; Schonjahn, C.; Ehiasarian, A.; Smith, I.J. Industrial scale manufactured superlattice hard PVD coatings. Surf. Eng. 2001, 17(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartita, R.; Ionita, D.; Demetrescu, I. Sustainable Coatings on Metallic Alloys as a Nowadays Challenge. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, C.; Ceschini, L. A Comparative Study of the Tribological Behaviour of PVD coatings on the Ti–6Al–4V Alloy. Tribology International 2011, 44, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizureanu, Petrică; Perju, Manuela-Cristina; Achiţei, Dragoş-Cristian; Nejneru, Carmen. Advanced Electro-Spark Deposition Process on Metallic Alloys. In Advanced Surface Engineering Research; Chowdhury, Mohammad Asaduzzaman, Ed.; IntechOpen: Publisher, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengchuan, Zh.; Guanjun, L.; Konoplianchenko, I.E. : A Review of the Electro-Spark Deposition Technology. Bull. Sumy Nat Agr Univ. Ser.: Mechanization and Automation of Production Processes 2022, 2(44), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, C.; Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Renna; Pappalettera, G.; Giovanni. Advancements in electrospark deposition (ESD) technique: A short review. Coatings. 2022, 12(10), 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chang, Q. Research status and prospect of electro-spark deposition technology. Surf. Technol. 2021, 50, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Dai, S.; Zhu, L. Research Progress in Electrospark Deposition Coatings on Titanium Alloy Surfaces: A Short Review. Coatings. 2023, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, V.V.; Gitlevich, A.; Verkhoturov, A.; Mikhaylyuk, A. Electrospark alloying of titanium and its alloys, physical and technological aspects and the possibility of practical use. Short review. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2013, 49(5), 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podchernyaeva, I.; Juga, A.I.; Berezanskaya, V.I. Properties of electrospark coatings on titanium alloy. Key Eng. Mater. 1997, 132, 1507–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyashki, T.G.; Kamburov, V.V.; Kostadinov, G.D.; Kandeva, M.K.; Dimitrova, R. Possibilities and prospects for improving the tribological properties of titanium and its alloys by electrospark deposition. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2022, 58(2), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulin, Y.I.; Verkhoturov, A.D.; Vlasenko, V.D. Electrospark alloying of surfaces of titanium alloys. Perspect. Mater. 2006, 1, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tarelnyk, V.B.; Paustovskii, A.V.; Tkachenko, Y.G.; Konoplianchenko, E.V.; Martsynkovskyi, V.S.; Antoszewski, B. Electrode Materials for Composite and Multilayer Electrospark-Deposited Coatings from Ni–Cr and WC–Co Alloys and Metals. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2017, 55, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadney, S.; Goodall, G.; Kim, G.; Moran, A.; Brochu, M. The transformation of an Al based crystalline electrode material to an amorphous deposit via the electrospark welding process. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 476, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, J.; Heard, D.W.; Brochu, M. Formation of nanostructured weldments in the Al-Si system using electrospark welding. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 4009–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, A.A. The effect of discharge pulse energy in electrospark deposition of amorphous coatings. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2022, 58, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Deng, C.; Huo, L.; Wang, L.; Fang, R. Novel method to fabricate Ti–Al intermetallic compound coatings onTi–6Al–4V alloy by combined ultrasonic impact treatment and electrospark deposition. J. Alloys Compd. Interdiscip. J. Mater. Sci.Solid–State Chem. Phys. 2015, 628, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Burkov, A.A.; Chigrin, P.G. Synthesis of Ti–Al intermetallic coatings via electro spark deposition in a mixture of Ti and Al granules technique. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 387, 125550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Feng, K.; Tan, Y.F.; Wang, X.; Tan, H. Effects of process parameters on microstructure and wear resistance of TiN coatings deposited on TC11 titanium alloy by electro spark deposition. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podchernyaeva, I.A.; Lavrenko, V.A.; Berezanskaya, V.I.; Smirnov, V.P. Electrospark alloying of the titanium alloy VT6 with tungsten–free hard alloys. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 1996, 35, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, Е.А.; Kudryashov, A.E.; Pogozhev, Yu.S.; Vakaev, P.V.; Zamulaeva, Е.I.; Sviridova, Т. А. Specific features of formation of nanostructured electrospark protective coatings on the OT4-1 titanium alloy with the use of electrode materials of the TiC-Ti3AlC2 system disperse-strengthe ned by nanoparticles. Russian Journal of Non-FerrousMetals 2007, 48(5), 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, Е.А.; Zamulaeva, Е.I.; A.E. Kudryashov, A.E.; Vakaev, P.V. Materials science and technological aspects of electrospark deposition of nanostructured WC-Co coatings onto titanium substrates. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2007, 4(3), 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplenko, M.A.; Podchernyaeva, I.A.; Panasyuk, A.D. Structure and wear resistance of coatings on titanium alloy and steels obtained by electro spark alloying with AlN–ZrB2 material. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2002, 41, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, Mesut; Kayali, Yusuf; Talaş, Şükrü. The Ceramic Composite Coating (TiC+TiB2) by ESD on Ti6AL4V Alloy and Its Characterization. Ceramic Sciences and Engineering 2020, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafyei, H.; Salehi, M.; Bahrami, A. Fabrication, microstructural characterization and mechanical properties evaluation of Ti/TiB/TiB2 composite coatings deposited on Ti6Al4V alloy by electro–spark deposition method. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46(10), 15276–15284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacik, J.; Baksa, P.; Emmer, S. Electro spark deposition of TiB2 layers on Ti6A14V alloy. Acta Metallurgica Slovaca 2016, 22(1), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manakova, O.S.; Kudryashov, A.E.; Levashov, E.A. On the application of dispersion–hardened SHS electrode materials based on (Ti, Zr)C carbide using electrospark deposition. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2015, 51, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, A.E.; Levashov, E.A. Application of SHS-electrode materials in pulsed electrospark deposition technology, XV International Symposium on Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis: Book of abstracts; IPCP RAS: Сhernogolovka, 2019; pp. 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, E.A.; Vakaev, P.V.; Zamulaeva, E.I.; Kudryashov, A.E.; Kurbatkina, V.V.; Shtansky, D.V.; Voevodin, A.A.; Sanz, A. Disperse-strengthening by nanoparticles advanced tribological coatings and electrode materials for their deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201(13), 6176–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, E.A.; Vakaev, P.V.; Zamulaeva, E.I.; Kudryashov, A.E.; Pogozhev, Yu.S.; Shtansky, D.V.; Voevodin, A.A.; Sanz, A. Nanoparticle dispersion-strengthened coatings and electrode materials for electrospark deposition. Thin Solid Films 2006, 515(3), 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, E.A.; Malochkin, O.Y.; Kudryashov, A.E. Influence of nano-sized powders on combustion processes and formation of composition, structure, and properties of alloys of the system Ti-Al-B. Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals 2003, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinov, G.; Danailov, P.; Dimitrova, R.; Kandeva, M. Surface topography and roughness parameters of electrospark coatings on titanium and nickel alloys. Applied Engineering Letters 2021, 6(3), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyashki, T.G.; Kostadinov, G.D.; Dimitrova, R.B.; et al. Improving Surface Properties of Titanium Alloys by Electrospark Deposition with Low Pulse Energy. Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry 2022, 6, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G.; Kandeva, M.; et al. Study of the Influence of Coating Roughness on the Properties and Wear Resistance of Electrospark Deposited Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy. Tribology in Industry 2024, 46(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G.; Kandeva, M. Surface Characteristics, Properties and Wear Resistance OF TIB2 BASED Hard-Alloy Coatings Obtained by Electrospark Deposition at Negative Polarity on Ti6Al4V Alloy. Tribology in Industry 2023, 45(4), 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, B. Device for Local Electric-Spark Layering of Metals and Alloys by Means of Rotating Electrode. US Patent № 3,832,514. 27 ( Aug 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, B.; Hogmark, S. Hardness measurements of thin films. Thin Solid Films 1984, 114(3), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Designation | Current, I, A | Capacitance, C, μF | Pulse duration, Ti, μs | Frequency, f, kHz | Pulse energy, E, J | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample 1 | 16 | 4,4 | 12 | 8,33 | 0,025 | ||

| 2 | Sample 2 | 11,2 | 0,5 | 12 | 8,33 | 0,013 | ||

| 3 | Sample 3 | 12,8 | 0,5 | 8 | 12,5 | 0,013 | ||

| 4 | Sample 4 | 16 | 2 | 12 | 8,33 | 0,02 | ||

| 5 | Sample 5 | 12,8 | 4,4 | 8 | 12,5 | 0,02 | ||

| Main phases |

2θ0 |

Рhases in small amounts |

2θ0 |

Traces of phases |

2θ0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

α-Ti |

35.38;38.5;40.2;53;63;70.8;74;76.2;77.2 | AlTi |

38.72;45.6;65.35;66.05;70.5;78.45;79.20 | Al,≈ | 38.5;44.7;65 |

|

AlTi3 |

26.33;31.12;35.65;38.8;39.4;40.8;43.05;53.8 | Ti6O |

34.9;37;38.4;40;52.5;70.1;75.6 | TiC0.7N0.3 | 35;42;61;72.9 |

| TiN | 36.95;42.95;62.2;74.5;78.5 | Ti3O |

37.8;39.9;52.1;62.5;69.6;75.3 | AlN | 20.5;33.2;36.2;38.1;59.4;61;66;70; 71.8;72.7 |

|

TiB2 |

27.7;33.38;34.2;44.6;56.9;61.1;67.9;72;78.6 | TiC0.3N0.7 |

36.5;74.5 | AlB | 21.5;23.3;36.8 |

|

TiN0.3 |

35;37.5;39.5;52.2;62.5;69.2;75.5;77 | Al2O3 |

19.5;32.1;35.65;37.6;39.2;43.05;44.5;45.6;50;56.7;60.5;66.8;71.4;75.3;78.55 | BN | 43.1;74;76 |

|

TiB |

37.05;42.95;62.25;78.5 | Ti2O |

33.6,35.65;38.45;40.7;53;63.7;70.5;76.6;77.15;78.5 | Al2.86O3.45N0.55 | 32;37.5;45.8;66.5;69.5 |

|

Ti3.2B1.6 N2.4 (Ti4N3B2)0.8 |

33.36;37;42.95;62.25;74.5;78.5 | TiC1-x | 35.9;41.7;60.3;72.2 | Al3Ti |

25.5;33.5;39.5;42.2;46;48;55;65.8;66.6;70;75.3 |

| Рhases | α-Ti | TiN | TiN0.3 | TiC0.3N0.7 | TiB2 | TiB | Ti3.2B1.6N2.4 | Al3Ti | Ti3O | Ti2O | Al2O3 | TiC1-x | AlN | AlTi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crys tallite size, nm |

26-87 | 13-66 | 31- 46 |

6 - 51 | 15- 78 | 14-55 | 31-53 | 26- 49 |

17-44 | 33- 40 |

22- 76 | 10-44 | 14-37 | 22-49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).