Submitted:

27 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

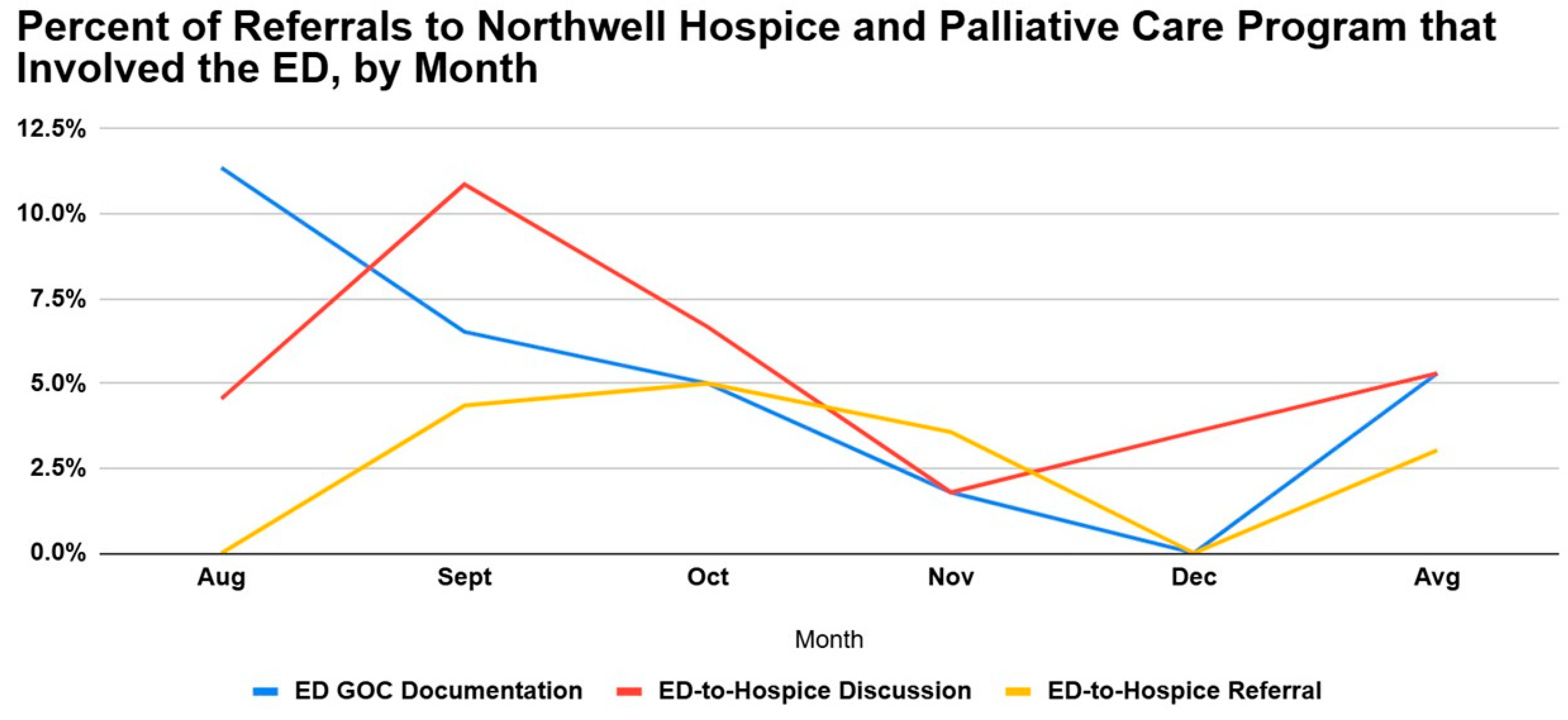

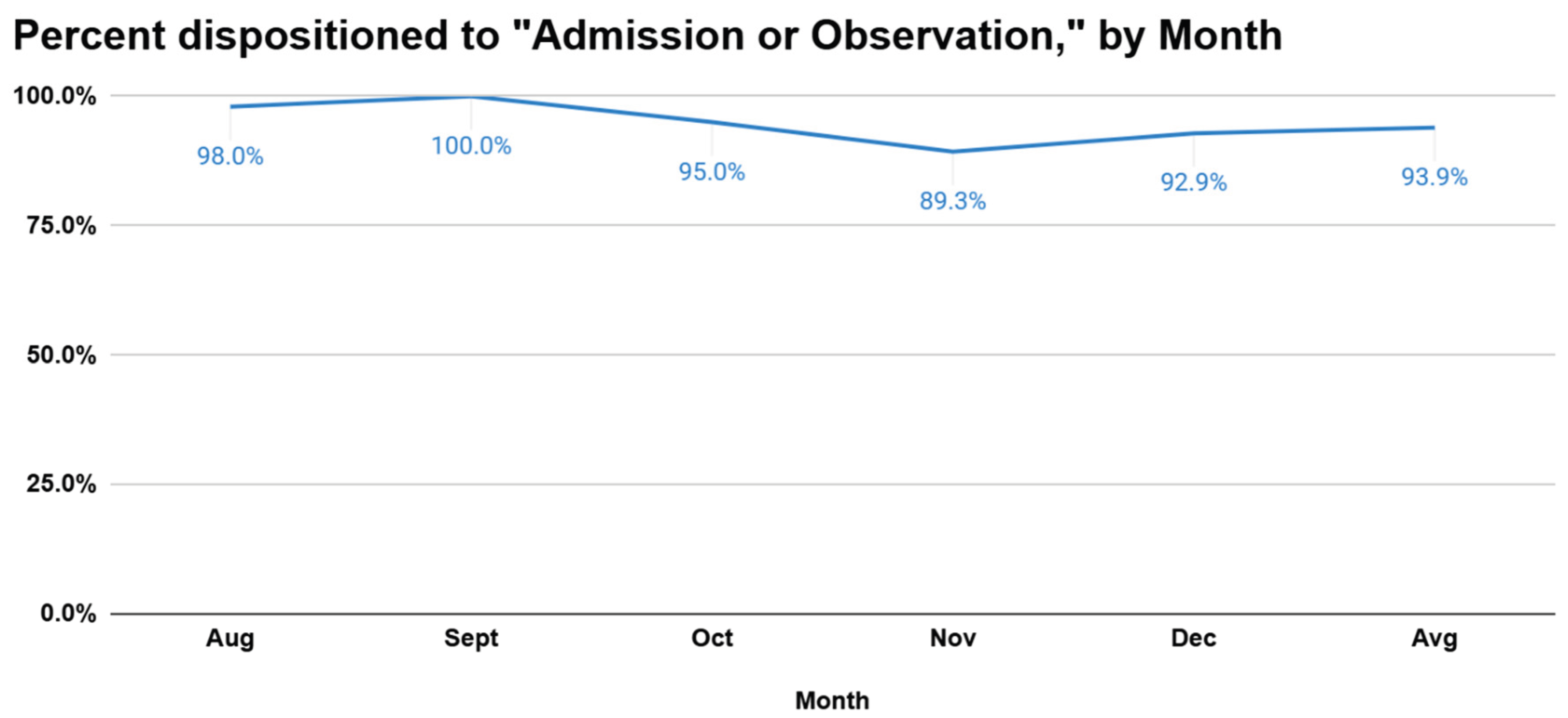

Hospice and palliative care improve quality of life for patients with advanced illness, yet referrals from emergency departments (EDs) remain limited. This study aimed to establish a baseline rate of ED-initiated referrals from the Northwell’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center to its Health’s Hospice and Palliative Care Program between August and December 2024. Using an institutional database, we reviewed 262 referrals and identified referral sources, documentation of ED goals-of-care (GOC) discussions, and patient disposition. Only 5.3% of all palliative care referrals and 3.0% of actual hospice placement referrals originated from the ED, with a decline in ED GOC discussions over the study period. Nearly all referred patients were admitted or placed in observation rather than discharged home or directly to hospice. Persistent cultural, educational, and workflow barriers may limit integration of palliative care within the ED. Improved interdisciplinary communication, provider training, and structured ED-to-hospice pathways may increase appropriate referrals, reduce unnecessary hospitalizations, and promote goal-concordant end-of-life care. Establishing this baseline provides a foundation for future quality improvement initiatives aimed at enhancing patient-centered outcomes for Northwell patients with advanced illness.

Keywords:

Introduction

- − Reduced ED length of stay: When palliative or hospice pathways are established early, patients spend less time in the ED waiting for placement or treatment decisions [10].

- − Reduced hospital length of stay: Patients identified early for hospice transition may be admitted briefly for stabilization or symptom control, then transferred to appropriate hospice care settings[11].

- − Increased multidisciplinary care: Successful ED-to-hospice transitions require close collaboration between ED physicians, palliative care specialists, and social workers, fostering a multidisciplinary approach that supports both patients and families.

Methods

- Data of referral

- Patient name

- Patient's date of birth

- Whether an ED Goals of Care Discussion (ED GOC) was documented

- Whether the referral was from LIJ’s ED, as indicated by whether an ED-to-Hospice discussion was documented

- Whether an ED-to-Hospice referral (for actual hospice placement from the ED) was made

- Disposition (admit/observation vs. discharge)

Results

Discussion

Limitations

References

- Ouchi, K.; George, N.; Schuur, J. D.; Aaronson, E. L.; Lindvall, C.; Bernstein, E.; Sudore, R. L.; Schonberg, M. A.; Block, S. D.; Tulsky, J. A. Goals-of-Care Conversations for Older Adults With Serious Illness in the Emergency Department: Challenges and Opportunities. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2019, 74(2), 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A. K.; McCarthy, E.; Weber, E.; Cenzer, I. S.; Boscardin, J.; Fisher, J.; Covinsky, K. Half Of Older Americans Seen In Emergency Department In Last Month Of Life; Most Admitted To Hospital, And Many Die There. Health Affairs 2012, 31(6), 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmer, J.; Mikati, N.; Arnold, R. M.; Wallace, D. J.; Callaway, C. W. Death and End-of-Life Care in Emergency Departments in the US. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5(11), e2240399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forero, R.; McDonnell, G.; Gallego, B.; McCarthy, S.; Mohsin, M.; Shanley, C.; Formby, F.; Hillman, K. A Literature Review on Care at the End-of-Life in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine International 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. K.; McCarthy, E.; Weber, E.; Cenzer, I. S.; Boscardin, J.; Fisher, J.; Covinsky, K. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health affairs (Project Hope) 31(6) 2012, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Espinosa, J.; Lucerna, A.; Parikh, N. Palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine 2022, 9(3), 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yang, S.-F. Hospice Care Improves Patients’ Self-Decision Making and Reduces Aggressiveness of End-of-Life Care for Advanced Cancer Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(23), 15593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.; Garrido, M. M.; Del Fabbro, E.; Noreika, D.; Normand, C.; Skoro, N.; Cassel, J. B. Evaluating Hospital Readmissions for Persons With Serious and Complex Illness: A Competing Risks Approach. Medical Care Research and Review 2019, 77(6), 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J. S.; Greer, J. A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E. R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V. A.; Dahlin, C. M.; Blinderman, C. D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W. F.; Billings, J. A.; Lynch, T. J. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic non-small-cell Lung Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363(8), 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel, S. K.; Whitcomb, M.; Solomon, A.; Swafford, A.; Youngwerth, J.; Wiler, J. L.; Bookman, K. Emergency department hospice care pathway associated with decreased ED and hospital length of stay. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2023, 76, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowski, N.; Scheu, A.; Glowacki, N.; Lindell, M.; Battle-Miller, K. Early Palliative Care Consults Reduce Patients’ Length of Stay and Overall Hospital Costs. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 2022, 39(11), 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, R. S.; Augustin, R.; Souvanna, P.; Meier, D. E. America’s Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation’s Hospitals. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2011, 14(10), 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A. A.; Keating, N. L.; Balboni, T. A.; Matulonis, U. A.; Block, S. D.; Prigerson, H. G. Place of Death: Correlations With Quality of Life of Patients With Cancer and Predictors of Bereaved Caregivers’ Mental Health. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010, 28(29), 4457–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. (1995). JAMA 274(20), 1591–1598. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7474243/. [CrossRef]

- BASOL, N. The Integration of Palliative Care into the Emergency Department. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine 2015, 15(2), 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel, S. K.; Whitcomb, M.; Solomon, A.; Swafford, A.; Youngwerth, J.; Wiler, J. L.; Bookman, K. Emergency department hospice care pathway associated with decreased ED and hospital length of stay. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2023, 76, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. K.; Fisher, J.; Schonberg, M. A.; Pallin, D. J.; Block, S. D.; Forrow, L.; Phillips, R. S.; McCarthy, E. P. Am I Doing the Right Thing? Provider Perspectives on Improving Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2009, 54(1), 86–93.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzen, C. R.; Richardson, L. D.; Hopper, S. S.; Ortiz, J. M.; Whang, C.; Morrison, R. S. Does Palliative Care Have a Future in the Emergency Department? Discussions with Attending Emergency Physicians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2012, 43(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzen, C. R.; Hwang, U.; Cohen, J. A.; Fischman, M.; Morrison, R. S. Characteristics of Emergency Department Patients Who Receive a Palliative Care Consultation. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2012, 15(4), 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, J. D.; Deb, P.; Dellenbaugh, C.; Burgess, J. F.; Zhu, C. W.; Christiansen, C. L.; Luhrs, C. A.; Cortez, T.; Livote, E.; Allen, V.; Morrison, R. S. Hospital-Based Palliative Care Consultation: Effects on Hospital Cost. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2010, 13(8), 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. M.; Newman, J. M.; Lasher, A.; Brody, A. A. Effects of Initiating Palliative Care Consultation in the Emergency Department on Inpatient Length of Stay. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2013, 16(11), 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudzen, C. R.; Stone, S. C.; Morrison, R. S. The Palliative Care Model for Emergency Department Patients with Advanced Illness. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2011, 14(8), 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forero, R.; McDonnell, G.; Gallego, B.; McCarthy, S.; Mohsin, M.; Shanley, C.; Formby, F.; Hillman, K. A Literature Review on Care at the End-of-Life in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine International 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmer, J.; Mikati, N.; Arnold, R. M.; Wallace, D. J.; Callaway, C. W. Death and End-of-Life Care in Emergency Departments in the US. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5(11), e2240399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, R.; Peyton, K.; Pajka, S. E.; Grudzen, Corita; Conroy, Mary Carol; Southerland, L. T. Arranging Hospice Care from the Emergency Department: A Single Center Retrospective Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2022, 63(3), e281–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, T.; Kozikowski, A.; Kwon, N.; Emmert, B.; Akerman, M.; Pekmezaris, R. Identifying Advanced Illness Patients in the Emergency Department and Having Goals-of-Care Discussions to Assist with Early Hospice Referral. (2018). The Journal of Emergency Medicine 54(2), 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Rege, R.; Peyton, K.; Pajka, S. E.; Grudzen, Corita; Conroy, Mary Carol; Southerland, L. T. Arranging Hospice Care from the Emergency Department: A Single Center Retrospective Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2022, 63(3), e281–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L. M.; Ruthazer, R.; Moss, A. H.; Germain, M. J. Predicting Six-Month Mortality for Patients Who Are on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2009, 5(1), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldonowicz, J. M.; Runyon, M. S.; Bullard, M. J. Palliative care in the emergency department: an educational investigation and intervention. BMC Palliative Care 2018, 17(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. G.; English, D. P.; Owyang, C. G.; Chimelski, E. A.; Grudzen, C. R.; Wong, H.; Aslakson, R. A.; Aslakson, R.; Ast, K.; Carroll, T.; Dzeng, E.; Harrison, K. L.; Kaye, E. C.; LeBlanc, T. W.; Lo, S. S.; McKenna, K.; Nageswaran, S.; Powers, J.; Rotella, J.; Ullrich, C. End-of-Life Care, Palliative Care Consultation, and Palliative Care Referral in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2020, 59(2), 372–383.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).