1. Introduction and Objectives

Patients requiring specialized palliative care who exhibit significant global dysfunction, facemotor difficulties accessing hospital-based palliative care consultations, or do not benefit from follow-up with other specialties may be referred to community or home-based palliative care teams (1–4).

Therefore, community palliative care teams will monitor patients with greater motor and cognitive limitations, more dependent on activities of daily living, in more advanced stages of the disease and, often, with imminent loss of oral intake(1,5–7).

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement is a minimally invasive procedure that involves the endoscopic placement of an artificial tube between the stomach and the abdominal wall. This is a safe and efficient method that safeguards nutritional and water supply to patients without an oral route, or who are about to lose it and who have an expected survival of more than four weeks (8–10).

For those with sudden loss of the oral route, and with an expected survival of more than four weeks, it is permissible to guarantee nutritional and water supply through a nasogastric tube until the PEG is placed (8,9,11).

In our clinical practice, we observe a high rate of complications associated with long-term nasogastric tubes, particularly in frail patients in need of specialized palliative care.

In patients with an expected survival of less than four weeks, the assessment and decision of a multidisciplinary team must be individualized, although the most frequent and acceptable approach is the comfort feeding method, avoiding measures of futility and therapeutic intrusion (9,12,13).

There is some controversy regarding the use of PEG in patients with dementia and severe-extreme frailty (8,10). The most frequent and main indications are malignant neoplasms of the upper digestive tract, as well as those of the head and neck, along with certain neurological diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (8,10). However, for these indications, there is a gap in knowledge and there is also a lack of publications with data on follow-up by specialized palliative care, regarding the benefits of this approach.

In this context, our study aims to evaluate the impact of PEG placement on survival and quality of life in patients followed by a community palliative care team over the last four years. As secondary objectives, we intend to evaluate which are the main diseases and clinical reasons that motivated the request for PEG and the assessment using the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) before PEG placement. We also sought to know if the socioeconomic conditions have any influence on PEG’s request.

2. Methods

Study design: This is an observational, non-interventional, retrospective cohort study. The STROBE guidelines (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) were followed (14).

Selection of participants: All 1000 patients followed by a community palliative care support team in the northern region of Portugal between March 2020 and December 2023 were considered. Of these patients, 54 underwent PEG. We also considered a control group of 20 patients that had a nasogastric tube for more than 4 weeks.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (reference CE/2023/34), and the Helsinki Declaration was respected. The European General Data Protection Act was respected. All data collected were recorded and saved electronically, identifiable data was anonymized and protected by a password, to which only the researchers had access.

Measures:

Data collection: Data were obtained through the electronic clinical process and the physical clinical file in March-April/2024. The information extracted included sex, age, diagnosis, referring unit, team follow-up starting date and number of days of follow-up, life expectancy on the start date of follow-up by the team (superior or inferior to six weeks), and symptom control and quality of life assessment (with the application of Edmonton scale (15) and the Personal Outcomes Scale (16), respectively). Additional information was collected regarding the existence of a caregiver and their characteristics, the level of functionality upon admission to the team (assessed using PPSv2 (17)), date and reason for the PEG request, the team responsible for the request (community palliative care team or previous request) and PEG placement date. Finally, data about place and date of death were also collected.

Social support: The existence of basic social support was measured by evaluating whether patients have a multipurpose certificate and dependency supplement, which are the main support instruments of the Portuguese state for especially vulnerable and dependent patients.

Data analysis: Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics measures (absolute and relative frequencies, means, and respective standard deviations) and inferential statistics. In this, the Chi-square test of independence, the Fisher test, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, the Cox regression, the Student’s t-test for independent samples, the Mann-Whitney test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. The Chi-square assumption that there should be no more than 20% of cells with expected frequencies less than five was analyzed. When this assumption was not satisfied, the Chi-square test was utilized using the Monte Carlo simulation. Differences were analyzed with the support of standardized adjusted residuals. The normality of distribution was analyzed using the skewness and kurtosis of the graphical representation. The significance level to reject the null hypothesis was set at α ≤ .05. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software version 28 for Windows.

3. Results

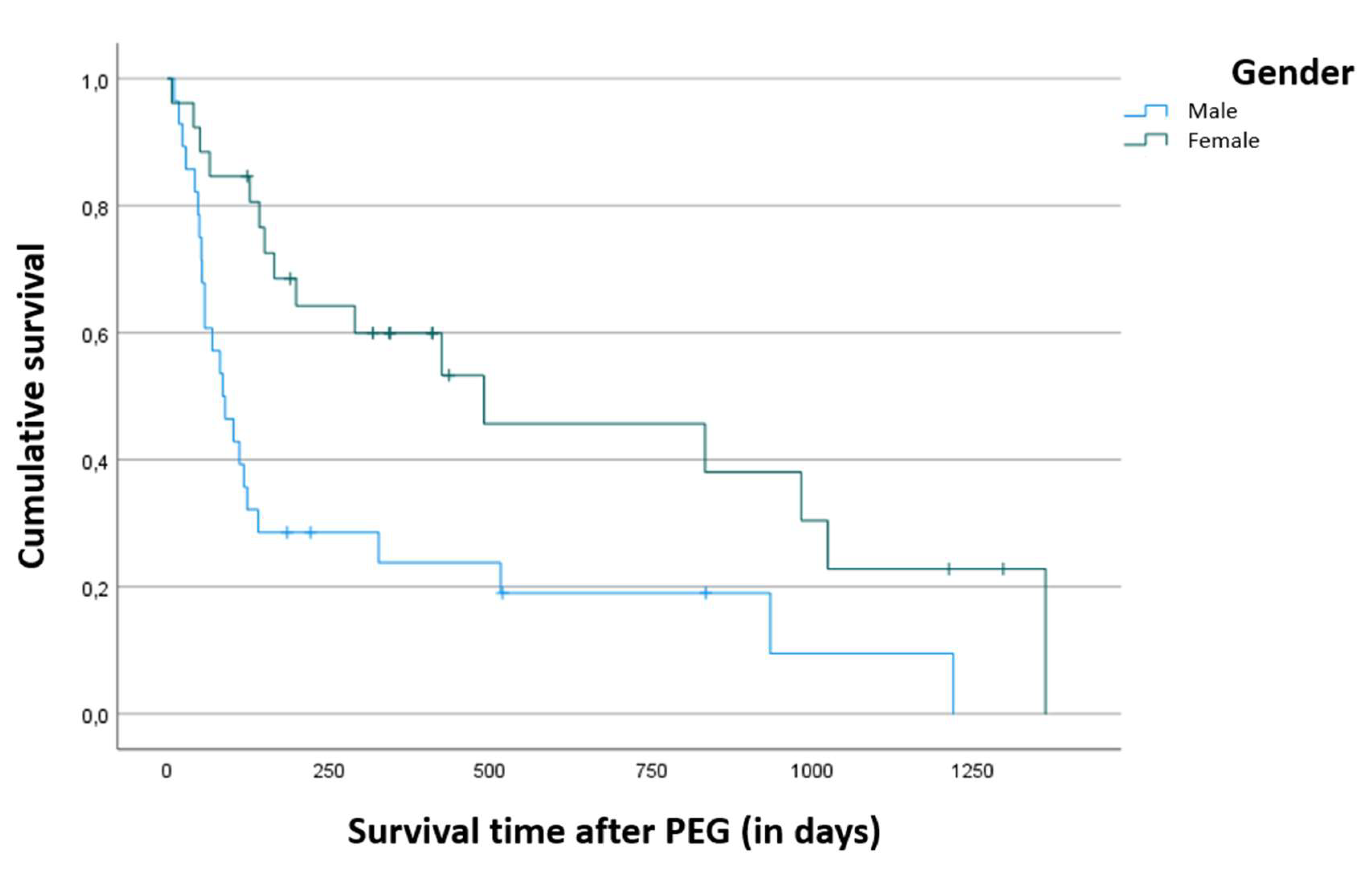

Mortality during follow-up by the community palliative care team was 74.1% (n=40) and age at admission to the team was not a predictive factor of survival time (p = 0.397). Data analysis allowed us to verify that the survival time was significantly higher in women (p = 0.003), as shown in

Figure 1, i.e. while males had an average survival after PEG placement of around 9.8 months, females had an average survival of 21.4 months.

We observed that six patients (11%) experienced minor complications after PEG placement and no patients had major complications. Among the six patients with minor complications, such as mild bleeding (n = 3), soft tissue infection (n = 2) and externalization of PEG (probably related to an episode of delirium, n = 1), there were no significant differences in survival time. Four patients had their complications resolved within one to two weeks, while two patients died during this period, but their deaths were clinically unrelated to these complications (one with externalization of PEG and one with mild soft tissue infection).

Considering the 22 patients that had nasogastric tube inserted before PEG placement (for 7 to 20 days), we observed a significant reduction in respiratory secretions (91%), signs of discomfort (59%) and delirium (22.7%), with a significant reduction in doses and number of neuroleptics.

Regarding the 20 patients (10 males and 10 females) who had nasogastric tubes when they lost their oral route and who were not subjected to peg placement, we observed a survival rate of 1.7 months (no significant statistical differences between males and females). We observed that all patients (100%) had minor complications after nasogastric tube placement during this period, such as dyspnea associated with respiratory secretions (85%), persistent cough (85%), pain and signs of discomfort (60%), and major complications such as delirium (60%) that led to self-removal of the tube (30%) and pneumonia (25%).

No correlation was observed between the patient’s age and the reason/diagnosis for which PEG was requested (p= 0.874).

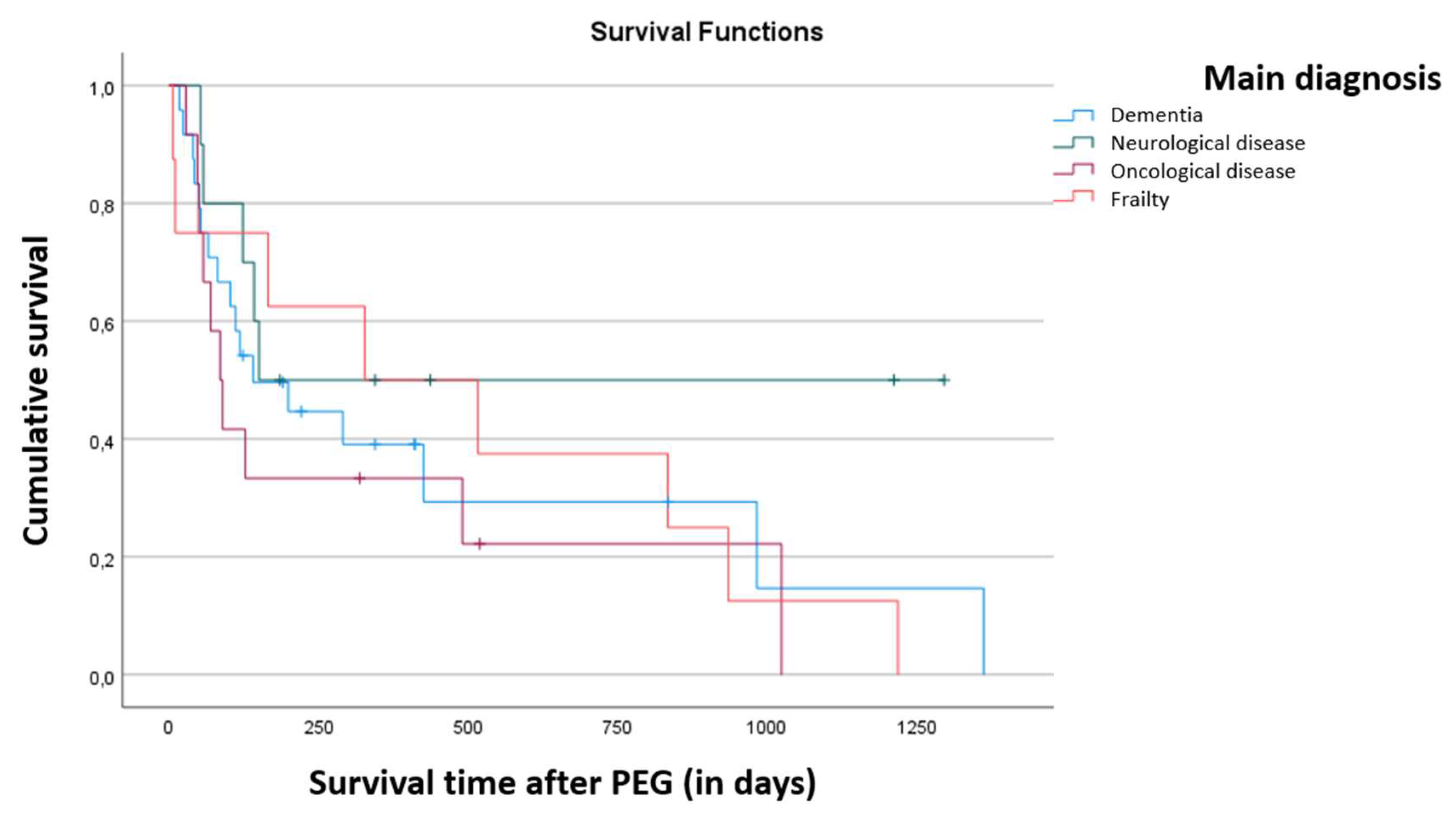

Finally, the relationship between disease and death is not statistically significant (χ

2 (3) = 6.485, p = 0.087), as shown in

Table 1. It is worth highlighting the fact that all frailty patients died during the period of follow-up by the team.

There was a significantly higher proportion of patients with dementia (χ

2 (3) = 12.647, p = 0.007), for whom the reason for the PEG request was partial or total dysphagia. Regarding patients with oncological disease, the main reason for the PEG request was dysphagia prevention, and the same was observed for patients with neurological disease. For patients with frailty the request was mainly due to established dysphagia, as seen in

Table 2.

The relationship between pathology and place of death is not statistically significant (p= 0.479). However, the age of death was significantly higher in Frailty Syndrome (χ2 KW (3) = 10.372, p = 0.016).

The age at PEG placement (χ2 KW (3) = 9.583, p = 0.022) and the age at the start of monitoring by the team (χ2 KW (3) = 9.673, p = 0.022) were significantly higher in Frailty Syndrome.

The difference in survival time between pathologies, after PEG placement, is not statistically significant (p = 0.422), as it is shown in

Figure 2.

The correlations between the results obtained by applying PPS and age (p = 0.997), age at the beginning of follow-up by the team (p = 0.999), age at PEG placement (p = 0.996), age at death (p = 0.997), place of death (p = 0.116) and follow-up time (p = 0.092) were not significant. Also, the difference in PPS values depending on the pathology was not statistically significant (p = 0.486).

PPS values were significantly higher when PEG placement was motivated by prevention (p = 0.028) and in patients who did not die (p = 0.002). However, PPS values did not show a significant predictive value for survival time (p = 0.061).

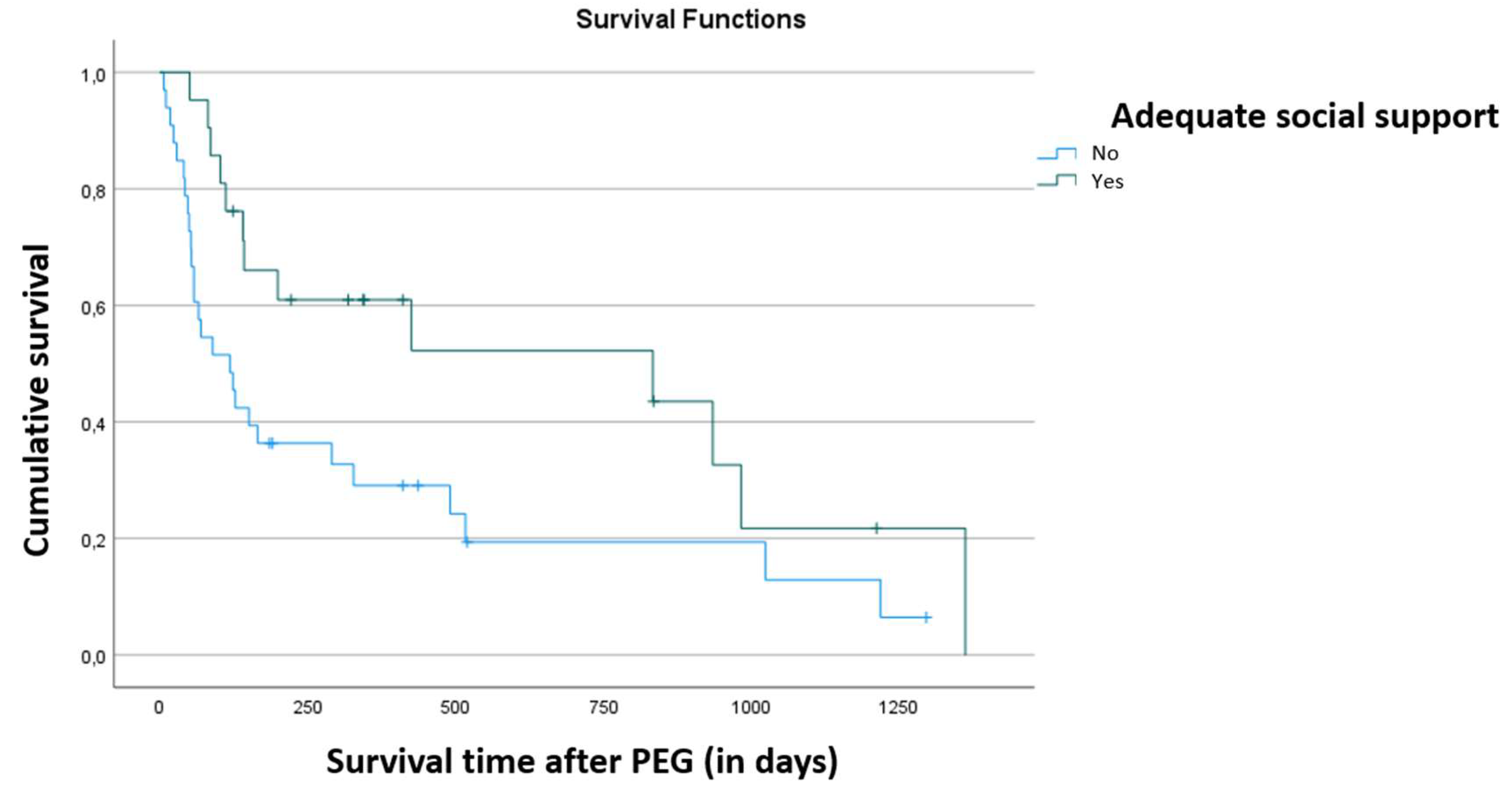

Survival was significantly higher in patients with adequate social support (p = 0.028), as shown in

Figure 3. There were no other correlations with social support, such as gender, reason for requesting PEG, place of death, main pathology, PPS, follow-up time, age at which the team started follow-up, and age at which the PEG was placed.

The correlation between follow-up time and survival time after PEG placement was statistically significant, positive and moderate (r = 0.457, p < 0.001). Thus, the longer the follow-up time, the longer the survival time after PEG placement.

There was a significantly higher proportion of deaths when the PEG was requested by others compared to when it was requested by the team involved in the study (p = 0.002). Of the 23 patients who had PEG requested by others, 22 died (95.7%) during the follow-up. In contrast, of the 31 patients who had PEG placement requested by this team, 18 died (58.1%).

Regarding survival time after PEG placement, despite not showing statistically significant differences, patients for whom the team requested PEG had longer follow-up time (166 days vs. 81 days, p=0.106) and longer survival times (563 days vs. 350 days, p=0.237).

This study found no significant differences between the various parameters analysed and the place of death.

4. Discussion

PEG is used as the preferred route of nutritional support for patients with long-term enteral nutrition needs. For patients in palliative care with actual or predictable loss of the oral route, and with an expected survival of more than four weeks, it is necessary to guarantee nutritional and water supply, with PEG placement being a good possible option.

In this study, the data suggest that women who underwent PEG placement had a longer survival time compared to men, with males having an average survival of 9.8 months, while females had an average survival of 21.4 months. This situation does not appear to be related to major complications from PEG placement or a greater disease burden. It may be related to the fact that women’s average life expectancy is higher. However, no consistent data allows us to assess the situation.

The survival rate seems to be in line with a study carried out by Akkuzu and colleagues in 2021, in which is reported an average life span after PEG insertion of 221.3±330.7 days and that half of the patients lived less than six months (180 days) and about 28% of the patients lived less than 30 days (18).

Another study by Stenberg et al. in 2022 states that mortality was around 15% at 30 days and 28% at 90 days (19). The authors noted that the main causes of death were malignancy and aspiration pneumonia. Additionally, they concluded that each year with PEG seems to increase the likelihood of death by 30 days and, differently from our study, women tendedto have a higher mortality rate than men (19).

It should be noted that those two studies were carried out in a hospital setting and without specific monitoring by a palliative care team, and our study is restricted to a community team specialized in palliative care and patients in the home context.

Regarding the age at which the PEG was placed there is no statistical significance, showing that it did not directly affect survival or complications inherent to the placement of the device. Stenberg et al. (2022) found some factors that may affect the survival rate, but without directly conditioning it, such as advanced age, diabetes, heart failure, C-reactive protein levels, and very high or very low body mass index. These factors may influence the final result of the procedure but without an impact on post-placement survival (19,20).

The mortality rate observed was 74.1%, but it is not possible to establish a relationship with the placement of the PEG since the specificity of the patients monitored by the team shows that the patient’s baseline status is already compromised. Some studies show that the mortality rate is higher in patients with oncological pathology compared with neurodegenerative diseases and organ failure (18,19,21,22). Sobani et al. (2018) conducted a study with patients over 100 years and reported a mortality rate about 9% below what is found in the literature (21). In their studies, Akkuzu et al. (2021) and Stenberg et al. (2022) revealed higher mortality rates in patients with oncological diseases. However, this is not the case in the present study, since no statistical significance was found between the pathology and survival time after PEG placement, nor with the PPS index (19,21–23).

The main causes for the placement of PEG were dysphagia already installed in the case of patients with dementia and predictable dysphagia in patients with oncological pathology. These data are in congruence with the literature. Sobani et al. (2018) reported that most patients with an indication for PEG had dysphagia and a risk of aspiration (21).

The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) does not recommend the placement of PEG in patients with a short life expectancy (30 days), regardless of the underlying pathology (24). The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) corroborates the indication (25). However, both safeguard the individualization of the decision-making process and the suitability for each patient. They also mention that the date of placement can be a relevant factor in preventing abrupt weight loss and reducing the catabolic process common in dementia and oncological diseases (25).

ESGE also states that PEG placement can play an important role in some degenerative and oncological diseases that induce marked weight loss, even with adjusted oral intakes (20,21,23,25,26).

The age at which PEG was placed was slightly higher in the elderly with frailty, just as the age at which the team started follow-up is higher in patients with frailty compared to patients with other pathologies. This fact is also corroborated by other studies that confirm the difficulty and ambivalence of the concept of frailty. It is a concept with multiple interpretations, making it difficult and delaying referral to palliative care teams. Loureiro and Carvalho (2021) summarize the frailty criteria as a clinical condition related to sarcopenia, neuroendocrine dysregulation, and immune system dysfunction, with the phenotype consisting of some characteristics such as unintentional weight loss, self-reported fatigue and/or exhaustion, decreased muscle strength, slow gait speed, and low level of physical activity (27). The concomitant presence of three or more of the aforementioned conditions confers the concept of frailty (27).

The late recognition of this condition or the devaluation of the reports from patients and family members leads to late referrals, which partly explains the age of referral to the team and the request for PEG placement. However, monitoring by differentiated teams and increased awareness of patients’ frailty seems to enhance survival time, and social and family support are strong contributors to prolonging survival.

There is a moderate and positive statistical significance between the time of PEG placement, the time of follow-up by the team, and survival time. It was observed that the longer the follow-up time, the longer the survival time. These data corroborate the empirical perception that monitoring by palliative care teams tends to increase survival time. Some studies carried out in patients with specific pathologies, such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, show that follow-up and post-PEG placement monitoring increases patient survival (18,22,26,27). Gaspar et al. (2021), Vieira et al. (2017) and Stenberg et al. (2022) show, although without specifying the type of patients, that patients with higher levels of follow-up have higher survival rates (19,22,28).

The present study shows that the proportion of deaths was higher in patients who were referred to the team already with PEG placed, than those in whom the team requests PEG. This factor can be explained by late referral and the patients’ greater symptomatic and disease burden at the time of entry into the team.

The mortality rate of patients with PEG prior to referral to the team was 95.7%, while patients with PEG placed at the request of the team and in follow-up by the team is 58.1%. The difference can be explained by the previous evaluation of the patient and family and by the window of opportunity at the time of PEG placement. Close and consistent team monitoring can facilitate the early detection of complications and mitigate their evolution (20,21,26).

Concerning the place of death, there does not seem to be any valuable relationship between the fact that the patient is a PEG carrier and the place where death takes place.

Considering the control groups (patients with nasogastric tube until death and patients with nasogastric tube until PEG was placed), we observed a significant increase in symptom control and quality of life with PEG placement and, inversely, we observed earlier death with a nasogastric tube and worse outcomes related to the patient’s quality of life, with more symptoms and associated suffering.

We can conclude that timely referrals, robust family and social support increase the survival of patients with PEG. The timing of PEG placement is important, but there are other factors as well. Monitoring by differentiated and specialized teams seems to contribute to the increase in the survival rate (1,3,27). The primary reason for the placement of PEG is dysphagia or the risk of it in oncological diseases (12,13,18,19,21). The present study shows that most PEG placements were in patients with dementia, followed by patients with oncological pathology.

We can conclude that the proximity of care after PEG placement seems particularly relevant to the survival time after the procedure. Thus, the timing of referral to differentiated teams and consistent and close patient assessments can be predictors of adjusted times for PEG placement.

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

First, the study’s observational nature may introduce confounding factors that could not be fully controlled, potentially impacting the results. Potential selection bias could have occurred, as the study relied on participants already receiving care in specific settings. Second, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the generalization of the findings to broader populations. Additionally, data collection was restricted to a single center experience, which may not fully represent the diversity of patient populations.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of PEG in specialized palliative care. The findings suggest a need for further exploration in this area. Future research should focus on larger, multicenter trials to confirm these results and explore the possible hard outcomes. Additionally, integrating methodologies like prospective registries can offer more precise predictions and treatment pathways. Expanding research to include more diverse populations and longer follow-up periods will also be crucial for fully understanding the implications of the PEG on clinical practice and patient outcomes.

6. Conclusions

The expected survival time for these patients would be less than four to six weeks if they had not placed the PEG (as presented by the control group who had a nasogastric tube until death), while with its placement, we had an observed average survival of 9.8 months in males and 21.4 months in females.

However, these patients could have had a nasogastric tube inserted, but the evidence reinforces what we observe in our daily practice: in the long term, the nasogastric tube presents clear disadvantages compared to PEG, due to the more frequent complications that affect patients’ survival and quality of life. In this study, we only observed 11% of patients with mild complications, that were resolved within one to two weeks. On the other hand, all patients with nasogastric tube had minor complications and several patients (25% to 60%) had major complications.

The main diseases and clinical reasons that motivated the PEG placement were dementia and oncological diseases, particularly in those patients with minor or severe dysphagia, and PPS were significantly higher in patients who inserted PEG for prevention. Although we did not identify a cutoff for PPS, the patients who had PEG placed to prevent oral loss all had PPS greater than 50%, while the remainder placed PEG had PPS less than 40%.

We had no correlations between our variables and the place of death, but we identified that basic social support (which we considered to be the multipurpose certificate and the dependency complement, which are additional support granted by the Portuguese state) is correlated with greater survival time.

Declarations of interest

Nothing to declare.

Funding

This research was supported by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020) and within the scope of the project RISE, Associated Laboratory (reference LA/P/0053/2020). The Centre for Innovative Biomedicine and Biotechnology (CIBB) and the Institute for Clinical and Biomedical Research (iCBR) are supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Portugal, through the Strategic Projects UIDB/04539/2020 (10.54499/UIDB/04539/2020) and UIDP/04539/2020 (10.54499/UIDP/04539/2020) and Associated Laboratory funding LA/P/0058/2020 (10.54499/LA/P/0058/2020). The present work was supported by ACIMAGO (Project 03/21).

References

- Hofmeister M, Memedovich A, Dowsett LE, Sevick L, McCarron T, Spackman E, et al. Palliative care in the home: a scoping review of study quality, primary outcomes, and thematic component analysis. BMC Palliat Care. 2018 Dec 7;17(1):41. [CrossRef]

- Hawley, P. Barriers to Access to Palliative Care. Palliative Care: Research and Treatment. 2017 Jan 1;10:117822421668888.

- Seow H, Bainbridge D. The development of specialized palliative care in the community: A qualitative study of the evolution of 15 teams. Palliat Med. 2018 Jul 8;32(7):1255–66. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. 2020. Palliative Care.

- Baik D, Russell D, Jordan L, Dooley F, Bowles KH, Masterson Creber RM. Using the Palliative Performance Scale to Estimate Survival for Patients at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Palliat Med. 2018 Nov;21(11):1651–61. [CrossRef]

- Virik K, Glare. Validation of the Palliative Performance Scale for Inpatients Admitted to a Palliative Care Unit in Sydney, Australia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002 Jun;23(6):455–7. [CrossRef]

- Olajide O, Hanson L, Usher BM, Qaqish BF, Schwartz R, Bernard S. Validation of the Palliative Performance Scale in the Acute Tertiary Care Hospital Setting. J Palliat Med. 2007 Feb;10(1):111–7. [CrossRef]

- Molina Villalba C, Vázquez Rodríguez JA, Gallardo Sánchez F. Gastrostomía endoscópica percutánea. Indicaciones, cuidados y complicaciones. Med Clin (Barc). 2019 Mar;152(6):229–36. [CrossRef]

- Tae CH, Lee JY, Joo MK, Park CH, Gong EJ, Shin CM, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. Gut Liver. 2024 Jan 15;18(1):10–26. [CrossRef]

- Lucendo A, Friginal-Ruiz A. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: An update on its indications, management, complications, and care. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2014 Dec;106(8):529–39.

- Gomes Jr CA, Andriolo RB, Bennett C, Lustosa SA, Matos D, Waisberg DR, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for adults with swallowing disturbances. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 May 22;2017(1).

- McClave SA, DiBaise JK, Mullin GE, Martindale RG. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016 Mar;111(3):315–34. [CrossRef]

- Palecek EJ, Teno JM, Casarett DJ, Hanson LC, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL. Comfort Feeding Only: A Proposal to Bring Clarity to Decision-Making Regarding Difficulty with Eating for Persons with Advanced Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Mar 11;58(3):580–4.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet. 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453–7.

- Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000 May 1;88(9):2164–71.

- Simões C, Santos S, Biscaia R. Validation of the Portuguese version of the Personal Outcomes Scale. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2016 May;16(2):186–200.

- Copyright Victoria Hospice Society. Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) version 2. Medical Care of the Dying. 2006;4thEd:121.

- Akkuzu MZ, Sezgin O, Ucbilek E, Aydin F, Rizaoglu Balci H, Yaras S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in Elderly Patients Aged Over 65: A Tertiary Center Long-term Results. Medical Bulletin of Haseki. 2021 Mar 12;59(2):128–32.

- Stenberg K, Eriksson A, Odensten C, Darehed D. Mortality and complications after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a retrospective multicentre study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022 Dec 28;22(1):361.

- Lima DL, Miranda LEC, Lima RNCL, Romero-Velez G, Chin R, Shadduck PP, et al. Factors Associated with Mortality after Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoscopic & Robotic Surgeons. 2023;27(2):e2023.00005.

- Sobani ZA, Tin K, Guttmann S, Abbasi AA, Mayer I, Tsirlin Y. Safety of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes in Centenarian Patients. Clin Endosc. 2018 Jan 31;51(1):56–60.

- Gaspar R, Ramalho R, Coelho R, Andrade P, Goncalves MR, Macedo G. Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Placement under NIV in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Severe Ventilatory Dysfunction: A Safe and Effective Procedure. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2023;30(1):61–7.

- Rahnemai-Azar, AA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Indications, technique, complications and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7739.

- Bischoff SC, Austin P, Boeykens K, Chourdakis M, Cuerda C, Jonkers-Schuitema C, et al. ESPEN guideline on home enteral nutrition. Clinical Nutrition. 2020 Jan;39(1):5–22.

- Arvanitakis M, Gkolfakis P, Despott E. Endoscopic management of enteral tubes in adult patients - Part 1: Definitions and indications. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53:81–92.

- Seyhan S, Tosun Taşar P, Karaşahin Ö, Albayrak B, Sevinç C, Şahin S. Complications and factors associated with mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Clinical Science of Nutrition. 2024 Aug 26;6(2):97–106.

- Loureiro N, Carvalho D. Doentes Crónicos e Cuidados Paliativos: Da Identificação Precoce ao Cuidado Centrado na Família, num Serviço de Medicina Interna. Med Interna (Bucur). 2021 Sep 21;28(3):277–87.

- VIEIRA J, NUNES G, SANTOS CA, FONSECA J. SERUM ELECTROLYTES AND OUTCOME IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar;55(1):41–5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).