Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) comprises a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited retinal dystrophies, affecting approximately 1 in 4,000 individuals worldwide and ~120,000 patients in the United States [

1,

2]. The disease is characterized by primary degeneration of rod photoreceptors, followed by secondary cone loss. RP patients experience night blindness (nyctalopia) and progressive constriction of the peripheral visual field. The decrease in visual field is exponential at 2.6–13.5% per year in remaining visual-field area, ultimately resulting in tunnel vision and total blindness [

1,

3]. To date, pathogenic variants in more than 100 genes have been implicated in RP [

4]. Despite significant research progress, no approved disease-modifying therapy exists to halt or slow the photoreceptor degeneration.

Rod photoreceptors are a marvel of evolution. The sensitivity of rods enables human eyes to detect a single photon [

5,

6]. This extraordinary sensitivity arises from the rod outer segment, a highly specialized light-sensing organelle containing a stack of hundreds of membrane discs densely packed with photopigment rhodopsin and the complete molecular machinery for phototransduction [

7,

8]. In mice, rod outer segment measures approximately 23.8 µm long, 1.32 µm in diameter, and contains about 810 discs [

9]. In addition to the complex structure, rod outer segments undergo continuous renewal, with the entire outer segment renewed every 10 days [

10]. The complex architecture of rod outer segments, coupled with the continuous renewal, makes rod photoreceptors particularly susceptible to mutations in genes not only specifically expressed in rods, but also in ubiquitous housekeeping genes. For example, mutations in

DHDDS (dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase) gene cause RP in patients with no other clinical manifestations [

11,

12,

13]. DHDDS is a key enzyme required for dolichol biosynthesis in every cell. Patients with RP-associated

DHDDS variants exhibit abnormal blood and urinary dolichol length profiles [

12].

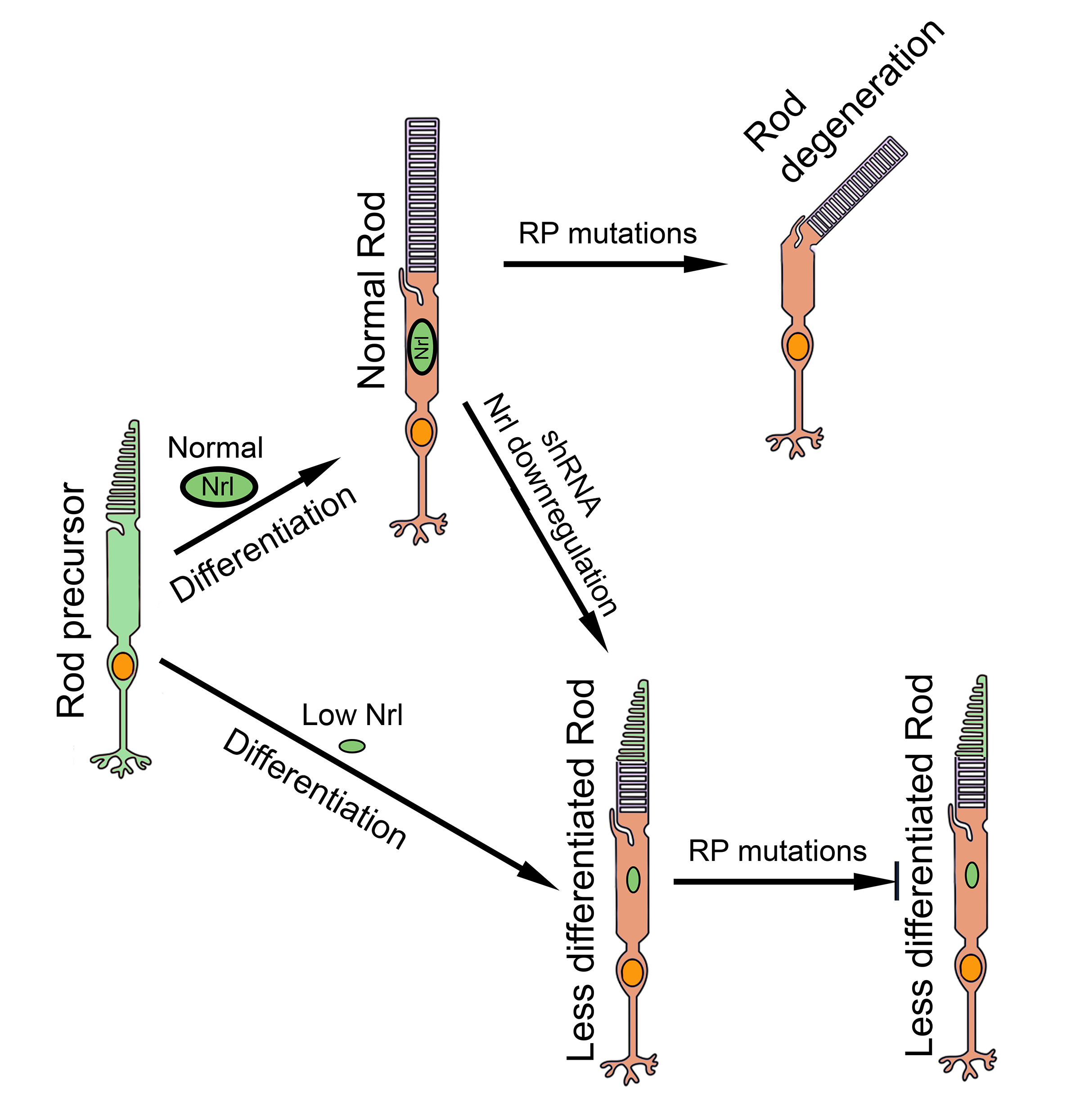

RP primarily affects rod photoreceptors thus strategies aimed at reprogramming rods to alter rod phenotype to non-rod or less-rod phenotypes could make these cells resistant to RP-associated degeneration. Nrl (neural retina leucine zipper), a master transcription factor that controls rod differentiation [

14], is the primary focus of rod reprogramming research. Genetic knockout of

Nrl prevents rod precursors from differentiating into rods thus they remain as rod precursors (i.e., S-cones) [

15,

16,

17]. Matured rods in adult animals could also be reprogrammed by conditional knockout or gene editing to neutralize

Nrl gene, and the reprogrammed cells were resistant to degeneration [

18,

19,

20,

21]. These findings support the strategy of targeting

Nrl as a promising therapeutic avenue for RP [

22].

While studies using conditional knockout and in vivo gene-editing approaches have demonstrated the principle of targeting

Nrl for rod reprogramming, the methods present significant challenges for clinical translation. Conditional knockout, for example, requires complex, multi-step engineering, including homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells to insert recombinase recognition sites (e.g., loxP sites for Cre recombinase) flanking the target sequence [

23]. Positively targeted clones must then be selected and used to generate chimeric animals. It is obvious that conditional knockout of

Nrl is not practical for direct clinical treatment in human patients. To achieve clinically viable therapy through

Nrl targeting requires a major technical breakthrough to inhibit Nrl expression safely and effectively in the adult human retina.

We hypothesized that rod photoreceptors could be reprogrammed and protected from degeneration by reducing the expression of Nrl instead of complete Nrl knockout. In a transgenic NrlN/N mouse line in which Nrl expression was markedly reduced, rod photoreceptors were successfully reprogrammed, and reprogrammed cells exhibited robust resistance to degeneration. When NrlN/N mice were crossed with two mouse models of RP, rd1 (Pde6brd1/rd1) and rhodopsin P23H knock-in (RhoP23H/P23H) mice, photoreceptor survival was significantly enhanced in the double-mutant mice. Our further investigation of a translational approach with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Nrl mRNA showed that shRNA effectively suppressed Nrl expression and conferred significant photoreceptor protection against degeneration in rd10 (Pde6brd10/rd10) mice when delivered via adeno-associated virus (AAV). The present work represents a major technical advance and establishes Nrl downregulation as a promising mutation-independent therapeutic strategy for autosomal dominant and recessive RP.

Results

Downregulation of Nrl Expression in NrlN/N Mice

We generated a transgenic

NrlN/N mouse line by inserting a

PGK-Neo cassette flanked with two FRT sites (

NrlN) into the intron between exons 3 and 4 of the

Nrl locus (

Figure 1). The

PGK-Neo cassette is known to influence the expression of genes [

24,

25]. Mice homozygous for

NrlN allele are viable, fertile, and grossly normal. Western blot analysis showed that the level of Nrl protein in retinas of

NrlN/N mice was significantly reduced, compared to that in the wild-type (WT) control mice (

Figure 2). There was also an increase in S-opsin and a decrease in rhodopsin protein in

NrlN/N mice (

Figure 2). These results confirmed that

Nrl expression was downregulated in

NrlN/N mice and rod differentiation was attenuated.

Morphologically, retinas of

NrlN/N animals (

Figure 3B, D) exhibited normal retinal layers with normal laminar organization as retinas of wild-type mice (

Figure 3A, C). Photoreceptor outer segments (OS) are shorter in

NrlN/N mice (

Figure 3B, D), especially in the inferior retina (

Figure 3D). No retinal disorganization or rosette was observed in

NrlN/N mice (

Figure 3B, D), unlike in

Nrl -/- mice in which retinal disorganization and rosettes are common [

15].

Dark-adapted ERGs (electroretinograms) from

NrlN/N mice showed a very small a-wave, and the b-wave was smaller than that from the WT mice (

Figure 3E). In light-adapted ERG, the b-wave from

NrlN/N mice was larger than that from WT mice (

Figure 3F).

Immunocytochemical staining for S-opsin showed significantly more positive cells in the retina of

NrlN/N animals (

Figure 4B, D) than in wild type mice (

Figure 4A, C), especially in the inferior retina (

Figure 4D). The average density of S-opsin positive cells in the inferior retinas of

NrlN/N mice was 8.3 times the density in the inferior retinas of WT mice (

Figure 4E,

Table 1). When the

PGK-Neo cassette was removed from

NrlN/N mice by crossing them with

R26FLPe mice, the density of S-opsin positive cells in the

Nrl -N/-N mice were not significantly different from that in WT retinas (

Figure 4E).

R26FLPe mice express FLPe (an enhanced version of flippase) [

26] in multiple organs, including the retina,

Interestingly, the density of S-opsin positive cells in the inferior retinas is significantly higher than that in the superior retinas in the WT mice, as well as in

NrlN/N, and in

Nrl -N/-N mice (

Figure 4E,

Table 1).

These results indicate that downregulation of Nrl expression reprograms rod photoreceptors, and cells in the inferior retina are more sensitive to Nrl downregulation than cells in the superior retina.

Nrl Downregulation and Photoreceptor Survival

To investigate the effects of Nrl downregulation on photoreceptor degeneration, we crossed

NrlN/N mice with two rod-degeneration models,

rd1 (

Pde6brd1/rd1) mouse and

Rho P23H knock-in mouse (

RhoP23H/P23H).

Rd1 mouse carries the

rd1 mutation in the

Pde6b gene and is a model widely used in RP research [

27]. Photoreceptors in

rd1 mice undergo rapid degeneration that by PD 30, the ONL had less than one row of nuclei in the superior and inferior retina (

Figure 5A, C). In double mutant

Pde6brd1/rd1/

NrlN/N mice, photoreceptors survived significantly. At PD 30, the ONL in the superior retina had 3 vertical rows of photoreceptor nuclei (

Figure 5B), and the ONL in the inferior retina had 5 vertical rows of nuclei (

Figure 5D). ERG from

rd1 mouse was flat at PD30, whereas the ERG b-wave from

Pde6brd1/rd1/

NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (

Figure 5E).

RhoP23H/P23H mouse is a transgenic mouse harboring the P23H mutation in

Rho gene. The

Rho P23H mutation is the most common mutation in autosomal dominant RP patients [

1,

28]. Retinal degeneration is also fast In

RhoP23H/P23H mice. By PD 30, the ONL had less than 1 row of nuclei in the superior retina and 1 row in the inferior retina (

Figure 6A, C6). In

RhoP23H/P23H/

NrlN/N mice, however, the ONL had 3-4 rows of nuclei in the superior retina (

Figure 6B) and 5-6 rows in the inferior retina (

Figure 6D) at PD 30. ERG from

RhoP23H/P23H mouse was almost flat at PD 30. In contrast, the ERG b-wave from

Pde6brd1/rd1/

NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (

Figure 6E).

These results indicate that reprogrammed photoreceptors are resistant to RP-associated degeneration.

Nrl Downregulation with shRNA Targeting Nrl mRNA

We then assessed a translational approach of downregulating

Nrl expression with shRNA. Sequences of shRNA targeting different regions of the ORF (open reading frame) of mouse

Nrl mRNA were predicted by 2 algorithms online (see Methods). Full shRNA was created by inserting an shRNA targeting sequence into the mirE backbone [

29] and fused to the 3’ UTR (untranslated region) of a small fluorescent protein CagFbFP [

30].

The capability of a given shRNA to downregulate

Nrl expression was evaluated in 293-Nrl cells that stably over expressed mouse

Nrl. A plasmid containing a given shRNA* (pRVS-CagFbFP-shRNA*) was transfected into 293-Nrl cells and transfected cells were harvested 72h later. Western blot analysis showed

Nrl expression was blocked by every shRNA tested (

Figure 7).

Two shRANs (shRNA-2 and -4) were packaged in AAV. The right eye of a

rd10 mouse was injected with 1.5 µl of either AAV-shRNA-2 or AAV-shRNA-4 to the subretinal space at PD14, and the left eye was injected with 1.5 µl of control AAV-GFP. Eyes were collected by PD 35 for morphological analysis. ERGs were recorded before eye collection. R

d10 mouse is a retinal degeneration model for experimental therapy [

27].

In the eyes treated with AAV-shRNA-2 (

Figure 8B) or AAV-shRNA-4 (

Figure 8D), the ONL in the injected area had 4-5 rows of nuclei, compared with 1 row of nuclei in the control eyes (

Figure 8A and C). The ERG b-wave amplitudes from the eyes injected with either AAV-shRNA-2 or AAV-shRNA-4 are larger than that from control eyes (

Figure 8E, 8 F).

These results confirmed that shRNA targeting Nrl mRNA effectively downregulated Nrl expression, resulting in photoreceptor protection.

Discussion

We have shown in this work that rod photoreceptor phenotype can be reprogramed by downregulating

Nrl expression. In transgenic

NrlN/N mouse,

Nrl expression was effectively downregulated by a

PGK-Neo cassette inserted into the intron between exon 3 and 4 of the

Nrl gene. The

PGK-Neo cassette is known to downregulate nearby genes [

24,

25]. The most important finding from experiments with

NrlN/N mouse is that rod photoreceptors can be reprogrammed by reducing

Nrl expression, indicating that the function of Nrl is a graded regulator of rod phenotype rather than an all-or-none determinant of rod differentiation, as previously assumed.

The discovery of reprogramming rod photoreceptors by reducing

Nrl expression also represents a major advance toward a mutation-independent therapy for retinitis pigmentosa (RP). Targeting

Nrl gene by genomic neutralizing

Nrl, as shown by previous studies [

18,

19,

20,

21], poses substantial hurdles for clinical translation. In contrast, downregulation of Nrl expression is technically straightforward and clinically feasible. Our results showed that shRNA-mediated suppression of

Nrl mRNA robustly reduces Nrl protein levels and effectively enhanced photoreceptor survival when delivered by AAV. These findings provide compelling preclinical evidence for an AAV-shRNA-based, mutation-independent therapeutic strategy for RP.

shRNA is a powerful tool for knocking down gene expressions by targeting specific mRNA sequences. A typical shRNA consists of a target-specific stem and a loop, with the full shRNA sequence usually under 100 bp. In the present work, we designed a compact all-in-one expression cassette (<2.5 kb) that includes a tissue-specific promoter, the ORF of a small fluorescent reporter (CagFbFP), the shRNA sequence embedded in the 3′UTR, and flanking AAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). This size enables efficient packaging into a double-stranded AAV (dsAAV) vector [

31]. Unlike single-stranded AAV (ssAAV), which requires rate-limiting second-strand synthesis in host cells, dsAAV delivers a transcription-ready double-stranded genome, resulting in a faster onset and higher transgene expression [

31]. Moreover, the small footprint of each shRNA allows multiple shRNAs targeting different regions of the same mRNA to be combined within a single vector, thereby enhancing the overall knockdown efficiency.

A striking feature of the retina of

NrlN/N mouse is the marked dorsoventral difference in rod photoreceptor differentiation. Photoreceptor outer segments in the inferior retina are substantially shorter (

Figure 3), and the number of S-opsin positive cells is ~9-fold higher than in the superior retina (

Figure 4,

Table 1). These findings indicate that rods in the inferior retina are considerably more sensitive to reduced

Nrl expression than those in the superior retina, and that rods in the inferior retina are less differentiated than those in the superior retina in

NrlN/N mice. In wild type mice, the density of S-opsin positive cells in the inferior retina is also significantly higher than that in the superior retina (

Figure 4,

Table 1), suggesting similar dorsoventral asymmetry in rod differentiation.

It is surprising to notice that photoreceptors in the superior retina were well preserved in both

Pde6brd1/rd1/

NrlN/N (

Figure 5B) and

RhoP23H/P23H/

NrlN/N mice (

Figure 6B), even though rod reprogramming is limited in this region in

NrlN/N background (as discussed above). Thus, a low level of rod reprogramming can result in a substantial increase in rod survival. This finding suggests that therapeutic strategies aimed at downregulating

Nrl for RP could have a broad therapeutic dose window. A successful clinical outcome may not require complete or high-level

Nrl suppression.

Results from

NrlN/N mice also indicate that Nrl is essential for maintaining normal retinal layers and the retinal laminal organization. Retinal disorganization and rosette formation are common in

Nrl knockout (

Nrl-/-) mice when

Nrl expression is absent [

15,

18]. No such structural disruption or retinal disorganization was observed in

NrlN/N mice (

Figure 3A). Thus, even at a modest level, Nrl preserves normal retinal lamination well. When considering targeting Nrl as a therapy for RP, downregulating

Nrl expression is likely a safer approach than gene knockout since the latter may have the risk of inducing retinal disorganization and rosette formation as unintended side effects.

Rod photoreceptors reprogramming would reduce their light sensitivity, thereby decreasing overall scotopic vision in treated eyes. In modern environments with ubiquitous artificial lighting, however, this is unlikely to cause meaningful functional difficulty. The benefit of halting the progressive retinal degeneration and preserving high-acuity vision by downregulating Nrl should far outweigh the modest trade-off in low-light sensitivity.

In summary, we have demonstrated that rod photoreceptor phenotype can be reprogrammed by downregulating the expression of Nrl and our AAV-shRNA experiments provide pre-clinical evidence supporting AAV-shRNA as a mutation-independent therapeutic approach for both recessive and dominant RP.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including adherence to the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines and the ARVO (Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

C57/6, Pde6brd1, RhoP23H, Pde6brd10 and R26FLPe mice were purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were kept in a 12 h light/dark cycle at an in-cage illumination of < 50 lux. The room temperature was kept at 20-22ºC.

Transgenic NrlN/N Mouse Generation

A transgenic

NrlN/N mouse line was generated in the Transgenic Mouse Facility, University of Miami School of Medicine. The transgene (

NrlN) DNA construct contained a

PGK-Neo cassette flanked by a pair of FRT sites inserted into the intron between exon 3 and 4 of the mouse

Nrl gene (

Figure 1). The DNA construct was electroporated into mouse embryonic stem cells. Correctly targeted cells were selected and used to generate chimeric animals. Transgenic chimeric mice were bred to obtain animals homozygous for

NrlN allele.

shRNA Design

Sequences of shRNA targeting different regions of mouse Nrl mRNA ORF were predicted by 2 algorithms online, the GPP Web Portal of Broad Institute [

32] and the SplashRNA of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [

33]. A full shRNA was made by placing a targeting sequence to the optimized mirE backbone [

29] and embedded in the 3’ UTR of a small fluorescent protein CagFbFP [

29,

30] to create CagFbFP-shRNA. The DNA construct was cloned into vector pRc/RSV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to create plasmid pRSV-CagFbFP-shRNA. Plasmid containing a given shRNA was tested for downregulating mouse Nrl expression in cells overexpressing mouse Nrl (see below).

Nrl Expressing Cells and shRNA Evaluation

A cell line overexpressing mouse Nrl was created for testing the capacity of a given shRNA to downregulate mouse Nrl expression. A plasmid (pcDNA-mNrl) expressing mouse Nrl was created by subcloning the mouse Nrl cDNA sequence (ORF plus a C-terminus HA-tag) into pcDNA3.1-puro (ThermoFisher, Scientific, Waltham, MA) and transfected into HEK293T cells (CRL-3211, ATCC, Manassas, VA) using jetPRIME transfection kit (Avantor, Radnor, PA). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium) with 10% fetal calf serum at 37ºC and maintained at 37ºC in 5% CO2/95% air. Stably transfected cells were selected with 1µg/ml puromycin. A cell colony expressed high level of Nrl was selected as 293-Nrl and expanded.

To evaluate capability of Nrl downregulating by a given shRNA*, a plasmid containing the shRNA (pRVS-CagFbFP-shRNA*, see above) was transfected into 293-Nrl cells. The level of mouse Nrl protein was examined 72h later. Un-transfected 293-Nrl cells and cells transfected with empty vector served as controls.

AAV-shRNA Construction

AAV-shRNA was created by subcloning the DNA construct of a given shRNA* (CagFbFP-shRNA*) into pscAAV, downstream of the human rhodopsin promoter. AAV-shRNA* was then packaged as double-stranded AAV (pscAAV-shRNA*) into serotype AAV2.7m8 for photoreceptor expression [

31,

34]. AAV-shRNA and AAV-GFP (> 2x10

13 GC/ml in PBS) were produced by Vector Builder (Chicago, IL, USA).

Subretinal Injection

To inject AAV-shRNA, a rd10 mouse was anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). AAV-shRNA was injected into the subretinal space via a 33-gauge blunt-ended needle connected to a 10-µl micro syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) under a surgical microscope. The right eye of the mouse was injected with 1.5 µl of AAV-shRNA and the left eye was injected with control viral vector AAV-GFP (1.5 µl).

Western Blotting

Retinas were harvested after animals were euthanized using CO2 overdose. Cell samples were collected after transfection. Retinal or cell samples were homogenized in the RIPA lysis buffer, and the total protein concentration of a sample was determined by the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay (Bio-Rad Labs, Hercules, CA). Western blotting was performed using primary antibodies (anti-Nrl ABN1712, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA; anti-HA 26183, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; anti-β actin sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; anti-S-opsin AB5407, MilliporeSigma; and anti-rhodopsin, B6-30, gift of Dr. Jeremy Nathans) followed by appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Antigen signals were detected with a Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and imaged on a luminescent image analyzer (ImageQuant LAS-4000, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chicago, IL).

Histology

For histological evaluation of the retinas, animals were euthanized using CO

2 overdose and immediately perfused with mixed aldehydes, as described previously [

35,

36]. Eyes were removed, semi-sectioned along the vertical meridian, and embedded in an Epon/Araldite mixture [

35,

36]. Semi-thin (1 µm thick) sections were cut to display the entire retina along the vertical meridian, or through the injected region, and stained with toluidine blue [

35,

36]. Retinal sections were examined by light microscopy.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical staining was employed to identify S-opsin positive cells in whole mount retinas. Tissue samples were prepared as described previously [

37]. Briefly, animals were perfused with PBS after euthanized using CO

2 overdose. Eyes were collected and retina-lens preparations were made by removing corneas and then the sclera-choroid-RPE. The retina-lens preparations were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, and incubated with primary anti-S-opsin antibodies (anti-S-opsin AB5407, MilliporeSigma) and then secondary antibodies conjugated with Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After antibody incubation, the lenses were removed, and the retinas were flat mounted photoreceptor-side up on slides. Stained whole mount retinas were examined by confocal microscopy and cone densities were quantified.

Electroretinogram (ERG)

ERGs were recorded with a UTAS system (LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Animals were dark adapted for more than 3 hours before ERG recording. An animal was put on the animal holder with a heat pad to maintain body temperature at 37 °C after anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). A contact lens electrode was placed on the cornea of each eye after the pupils were dilated with 0.1% atropine and 0.1% phenylephrine HCl. A differential electrode was placed under the skin of the forehead, and a ground electrode under the skin at the base of the tail. Full field ERGs were elicited by 1 ms white flashes generated by white LEDs in the Ganzfeld sphere. Inter-stimulus intervals were 10 s. Each recording was the average of 10 responses. The b-wave amplitudes of the treated eyes were compared with recordings from the control eyes.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using software Prism (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA). Data were evaluated by Student’s t-test for comparisons between two experimental groups or ANOVA (analysis of variance) followed by Tukey comparison among three or more groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.L., R.W.; Investigation: Y.L., S.J., W.T., and R.W.; Writing: Y.L., S.J., W.T., and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants R01EY015289, R01EY018586, R01EY031492, R01EY026643, Hope for Vision, grants from the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program of the State of Florida (Grant 08KN-09, 2KF02), and a private donation to Dr. Wen for Retinal Degeneration Research. It was also supported by NIH Core Grants P30EY14801 and P30EY002162 to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, and an

unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc. to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine (Protocol #23-108).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are presented in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAV |

Adeno-associated virus |

| DHDDS |

Dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase |

| dsAAV |

Double-stranded adeno-associated virus |

| ERG |

Electroretinogram |

| FLP |

Flippase recombinase |

| FRT |

Flippase recognition target |

| HA |

Hemagglutinin |

| INL |

Inner nuclear layer |

| IPL |

Inner Plexiform Layer |

| IS |

Inner segment |

| Nrl |

Neural retina leucine zipper |

| ONL |

Outer nuclear layer |

| OPL |

Outer plexiform layer |

| ORF |

Open reading frame |

| OS |

Outer segment |

| PBS |

Phosphate buffered saline |

| PGK–Neo |

Phosphoglycerate kinase I promoter-neomycin phosphotransferase gene |

| RP |

Retinitis pigmentosa |

| RPE |

Retinal pigment epithelium |

| shRNA |

short hairpin RNA |

| ssAAV |

Single-stranded adeno-associated virus |

| UTR |

Untranslated region |

| WT |

Wild type |

References

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1795-1809. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Cheung, S.; Fasso-Opie, A.; Galvin, O.; Moniz, L.S.; Earle, D.; Durham, T.; Menzo, J.; Li, N.; Duffy, S.; et al. The Impact of Inherited Retinal Diseases in the United States of America (US) and Canada from a Cost-of-Illness Perspective. Clin Ophthalmol 2021, 15, 2855-2866. [CrossRef]

- Delyfer, M.N.; Leveillard, T.; Mohand-Said, S.; Hicks, D.; Picaud, S.; Sahel, J.A. Inherited retinal degenerations: therapeutic prospects. Biol Cell 2004, 96, 261-269. [CrossRef]

- RetNet. Summaries of Genes and Loci Causing Retinal Diseases. Available online: https://retnet.org/summaries/ (accessed on.

- Tinsley, J.N.; Molodtsov, M.I.; Prevedel, R.; Wartmann, D.; Espigule-Pons, J.; Lauwers, M.; Vaziri, A. Direct detection of a single photon by humans. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12172. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, E.N., Jr. The discovery of the ability of rod photoreceptors to signal single photons. J Gen Physiol 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, V.; Cayouette, M. Development and disease of the photoreceptor cilium. Clin Genet 2009, 76, 137-145. [CrossRef]

- Yau, K.W.; Hardie, R.C. Phototransduction motifs and variations. Cell 2009, 139, 246-264. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Fotiadis, D.; Maeda, T.; Maeda, A.; Modzelewska, A.; Filipek, S.; Saperstein, D.A.; Engel, A.; Palczewski, K. Rhodopsin signaling and organization in heterozygote rhodopsin knockout mice. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 48189-48196. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.W. The renewal of photoreceptor cell outer segments. J Cell Biol 1967, 33, 61-72. [CrossRef]

- Zuchner, S.; Dallman, J.; Wen, R.; Beecham, G.; Naj, A.; Farooq, A.; Kohli, M.A.; Whitehead, P.L.; Hulme, W.; Konidari, I.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing links a variant in DHDDS to retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 2011, 88, 201-206. [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Lam, B.L.; Guan, Z. Aberrant dolichol chain lengths as biomarkers for retinitis pigmentosa caused by impaired dolichol biosynthesis. J Lipid Res 2013, 54, 3516-3522. [CrossRef]

- Kimchi, A.; Khateb, S.; Wen, R.; Guan, Z.; Obolensky, A.; Beryozkin, A.; Kurtzman, S.; Blumenfeld, A.; Pras, E.; Jacobson, S.G.; et al. Nonsyndromic Retinitis Pigmentosa in the Ashkenazi Jewish Population: Genetic and Clinical Aspects. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 725-734. [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, A.; Xu, J.Z.; Pawar, H.; Jackson, A.; Skolnick, C.; Agarwal, N. A conserved retina-specific gene encodes a basic motif/leucine zipper domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 266-270.

- Mears, A.J.; Kondo, M.; Swain, P.K.; Takada, Y.; Bush, R.A.; Saunders, T.L.; Sieving, P.A.; Swaroop, A. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet 2001, 29, 447-452. [CrossRef]

- Mustafi, D.; Engel, A.H.; Palczewski, K. Structure of cone photoreceptors. Prog Retin Eye Res 2009, 28, 289-302. [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.C.; Khan, N.; Novelli, E.; Khanna, H.; Strettoi, E.; Swaroop, A. Transformation of cone precursors to functional rod photoreceptors by bZIP transcription factor NRL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 1679-1684. [CrossRef]

- Montana, C.L.; Kolesnikov, A.V.; Shen, S.Q.; Myers, C.A.; Kefalov, V.J.; Corbo, J.C. Reprogramming of adult rod photoreceptors prevents retinal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 1732-1737. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Mookherjee, S.; Chaitankar, V.; Hiriyanna, S.; Kim, J.W.; Brooks, M.; Ataeijannati, Y.; Sun, X.; Dong, L.; Li, T.; et al. Nrl knockdown by AAV-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 prevents retinal degeneration in mice. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14716. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ming, C.; Fu, X.; Duan, Y.; Hoang, D.A.; Rutgard, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, W.; Hou, R.; Zhang, D.; et al. Gene and mutation independent therapy via CRISPR-Cas9 mediated cellular reprogramming in rod photoreceptors. Cell Res 2017, 27, 830-833. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Lo, C.H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y. All-in-one AAV-mediated Nrl gene inactivation rescues retinal degeneration in Pde6a mice. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e178159. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.M.; Skowronska-Krawczyk, D.; Chao, D.L. Targeting of the NRL Pathway as a Therapeutic Strategy to Treat Retinitis Pigmentosa. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.W.; Penninger, J.M.; Ohashi, P.S. Knockout mice: a paradigm shift in modern immunology. Nat Rev Immunol 2001, 1, 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.N.; Arnold, H.H.; Rigby, P.W.; Wold, B.J. Know your neighbors: three phenotypes in null mutants of the myogenic bHLH gene MRF4. Cell 1996, 85, 1-4.

- Pham, C.T.; MacIvor, D.M.; Hug, B.A.; Heusel, J.W.; Ley, T.J. Long-range disruption of gene expression by a selectable marker cassette. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 13090-13095. [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, F.; Angrand, P.O.; Stewart, A.F. Improved properties of FLP recombinase evolved by cycling mutagenesis. Nat Biotechnol 1998, 16, 657-662. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Hawes, N.L.; Hurd, R.E.; Davisson, M.T.; Nusinowitz, S.; Heckenlively, J.R. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res 2002, 42, 517-525. [CrossRef]

- Sakami, S.; Maeda, T.; Bereta, G.; Okano, K.; Golczak, M.; Sumaroka, A.; Roman, A.J.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Jacobson, S.G.; Palczewski, K. Probing mechanisms of photoreceptor degeneration in a new mouse model of the common form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa due to P23H opsin mutations. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 10551-10567. [CrossRef]

- Fellmann, C.; Hoffmann, T.; Sridhar, V.; Hopfgartner, B.; Muhar, M.; Roth, M.; Lai, D.Y.; Barbosa, I.A.; Kwon, J.S.; Guan, Y.; et al. An optimized microRNA backbone for effective single-copy RNAi. Cell Rep 2013, 5, 1704-1713. [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, V.V.; Remeeva, A.; Yudenko, A.; Kovalev, K.; Dubenko, A.; Goncharov, I.M.; Kuzmichev, P.; Rogachev, A.V.; Buslaev, P.; Borshchevskiy, V.; et al. A thermostable flavin-based fluorescent protein from Chloroflexus aggregans: a framework for ultra-high resolution structural studies. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2019, 18, 1793-1805. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, H.I.; Li, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X. Rapid and highly efficient transduction by double-stranded adeno-associated virus vectors in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther 2003, 10, 2105-2111. [CrossRef]

- GPP, W.P. GPP Web Portal Available online: https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/gene/search (accessed on.

- SplashRNA. SplashRNA. Available online: http://splashrna.mskcc.org/ (accessed on.

- Dalkara, D.; Byrne, L.C.; Klimczak, R.R.; Visel, M.; Yin, L.; Merigan, W.H.; Flannery, J.G.; Schaffer, D.V. In vivo-directed evolution of a new adeno-associated virus for therapeutic outer retinal gene delivery from the vitreous. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 189ra176. [CrossRef]

- LaVail, M.M.; Battelle, B.A. Influence of eye pigmentation and light deprivation on inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. Exp Eye Res 1975, 21, 167-192.

- Song, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tao, W.; Laties, A.M.; Luo, Z.; Wen, R. Photoreceptor protection by cardiotrophin-1 in transgenic rats with the rhodopsin mutation s334ter. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003, 44, 4069-4075.

- Li, Y.; Tao, W.; Luo, L.; Huang, D.; Kauper, K.; Stabila, P.; Lavail, M.M.; Laties, A.M.; Wen, R. CNTF induces regeneration of cone outer segments in a rat model of retinal degeneration. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9495. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A schematic of the NrlN DNA construct. The PGK-Neo cassette (red), flanked by two FRT sites (yellow), was inserted into the intron between exon 3 and 4 (gray) of the mouse Nrl gene. The PGK-Neo cassette is removable in the presence of recombinase flippase (FLP). Exon 4 is flanked by two loxP sites (blue).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the NrlN DNA construct. The PGK-Neo cassette (red), flanked by two FRT sites (yellow), was inserted into the intron between exon 3 and 4 (gray) of the mouse Nrl gene. The PGK-Neo cassette is removable in the presence of recombinase flippase (FLP). Exon 4 is flanked by two loxP sites (blue).

Figure 2.

Nrl downregulation in NrlN/N mice. Retinas were collected at PD 60 from NrlN/N and WT (wildtype C57) mice. Protein levels were examined by Western blot analysis. In NrlN/N mice, the level of Nrl was significantly reduced, as compared to that in the WT control. The levels of rhodopsin (Rho) were also reduced, whereas the level of S-opsin was increased in NrlN/N mice. The levels of β actin served as loading controls.

Figure 2.

Nrl downregulation in NrlN/N mice. Retinas were collected at PD 60 from NrlN/N and WT (wildtype C57) mice. Protein levels were examined by Western blot analysis. In NrlN/N mice, the level of Nrl was significantly reduced, as compared to that in the WT control. The levels of rhodopsin (Rho) were also reduced, whereas the level of S-opsin was increased in NrlN/N mice. The levels of β actin served as loading controls.

Figure 3.

Retinal morphology and ERG of NrlN/N mice. Eyes were collected from PD 60 NrlN/N and WT mice. The retina of NrlN/N mouse had normal layers in laminar organization (B, D) as that the retina of WT mouse (A, C). The rod outer segments (OS) were shorter in the NrlN/N mouse (B, D) than in the WT retina (A, C), especially in the inferior retina (D). Dark-adapted ERGs from NrlN/N mouse showed a very small a-wave, and the b-wave amplitude was smaller than the WT mouse (E, elicited by elicited by -0.402 log cd·s/m2 white flashes). The light-adapted b-wave from NrlN/N mice was larger than that from WT mice (F, elicited by 0.998 log cd·s/m2 flashes with 30 cd·s/m2 white background). Black arrowheads in E and F indicate flash onset. Retinal layers were indicated by white bars in panel A. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; OS: outer segments; IS: inner segments; ONL: outer nucleal layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer. Sup: superior; Inf: Inferior. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Figure 3.

Retinal morphology and ERG of NrlN/N mice. Eyes were collected from PD 60 NrlN/N and WT mice. The retina of NrlN/N mouse had normal layers in laminar organization (B, D) as that the retina of WT mouse (A, C). The rod outer segments (OS) were shorter in the NrlN/N mouse (B, D) than in the WT retina (A, C), especially in the inferior retina (D). Dark-adapted ERGs from NrlN/N mouse showed a very small a-wave, and the b-wave amplitude was smaller than the WT mouse (E, elicited by elicited by -0.402 log cd·s/m2 white flashes). The light-adapted b-wave from NrlN/N mice was larger than that from WT mice (F, elicited by 0.998 log cd·s/m2 flashes with 30 cd·s/m2 white background). Black arrowheads in E and F indicate flash onset. Retinal layers were indicated by white bars in panel A. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; OS: outer segments; IS: inner segments; ONL: outer nucleal layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer. Sup: superior; Inf: Inferior. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Figure 4.

Increase in S-opsin positive cells in NrlN/N mice. Eyes were collected at PD 60 from NrlN/N and WT mice. Immunocytochemical analysis in flat mounted retinas showed many S-opsin positive cells in the retina of NrlN/N mouse (B, D), especially in the inferior retina (D), compared to the superior (A) and inferior retina (C) of WT mouse. The average density of S-opsin positive cells in the superior retinas of NrlN/N mice is significantly higher than that in either WT mice (p<0.05, n=3), or in Nrl -N/-N mice in which the PGK-Neor cassette was removed (p<0.05, n=3) (E). In the inferior retina, the density of S-opsin positive cells in NrlN/N mice is much higher than in the WT and the Nrl -N/-N mice (p<0.0001, n=3) (E). The S-opsin positive cell densities in Nrl -N/-N mouse in the superior or in the inferior retina were comparable to those in WT mouse (E). In addition, the density of S-opsin positive in the inferior retina is significantly higher than in the superior retina in WT mice (p<0.005, n=3), as well as in NrlN/N mice (p<0.0001, n=3) and in Nrl -N/-N mice (p<0.05, n=3). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Increase in S-opsin positive cells in NrlN/N mice. Eyes were collected at PD 60 from NrlN/N and WT mice. Immunocytochemical analysis in flat mounted retinas showed many S-opsin positive cells in the retina of NrlN/N mouse (B, D), especially in the inferior retina (D), compared to the superior (A) and inferior retina (C) of WT mouse. The average density of S-opsin positive cells in the superior retinas of NrlN/N mice is significantly higher than that in either WT mice (p<0.05, n=3), or in Nrl -N/-N mice in which the PGK-Neor cassette was removed (p<0.05, n=3) (E). In the inferior retina, the density of S-opsin positive cells in NrlN/N mice is much higher than in the WT and the Nrl -N/-N mice (p<0.0001, n=3) (E). The S-opsin positive cell densities in Nrl -N/-N mouse in the superior or in the inferior retina were comparable to those in WT mouse (E). In addition, the density of S-opsin positive in the inferior retina is significantly higher than in the superior retina in WT mice (p<0.005, n=3), as well as in NrlN/N mice (p<0.0001, n=3) and in Nrl -N/-N mice (p<0.05, n=3). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 5.

Photoreceptor preservation in Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mice. Retinal degeneration in rd1 (Pde6brd1/rd1) mouse is rapid that by PD 30, the ONL had less than 1 row of nuclei in both the superior (A) and inferior retina (C). In Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse, photoreceptors survived well (B, D). The ONL had 3 rows of nuclei in the superior retina (b) and 5 rows in the inferior retina (D) at PD 30. ERG from Pde6brd1/rd1 mouse was flat whereas the b-wave from Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (E, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowhead indicates flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 25 µm.

Figure 5.

Photoreceptor preservation in Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mice. Retinal degeneration in rd1 (Pde6brd1/rd1) mouse is rapid that by PD 30, the ONL had less than 1 row of nuclei in both the superior (A) and inferior retina (C). In Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse, photoreceptors survived well (B, D). The ONL had 3 rows of nuclei in the superior retina (b) and 5 rows in the inferior retina (D) at PD 30. ERG from Pde6brd1/rd1 mouse was flat whereas the b-wave from Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (E, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowhead indicates flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 25 µm.

Figure 6.

Photoreceptor preservation in RhoP23H/P23H/NrlN/N mice. Retinal degeneration in RhoP23H/P23H mouse is rapid that the ONL had less than 1 row of nuclei in the superior retina (A) and 1 row of nuclei in the inferior retina (C) by PD 30. In RhoP23H/P23H/NrlN/N mouse, photoreceptors survived well (B, D). The ONL had 3-4 rows of nuclei in the superior retina (B) and 5-6 rows in the inferior retina (D) at PD 30. ERG b-wave from RhoP23H/P23H mouse was very small, whereas the b-wave from Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (E, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowhead indicates flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 25 µm.

Figure 6.

Photoreceptor preservation in RhoP23H/P23H/NrlN/N mice. Retinal degeneration in RhoP23H/P23H mouse is rapid that the ONL had less than 1 row of nuclei in the superior retina (A) and 1 row of nuclei in the inferior retina (C) by PD 30. In RhoP23H/P23H/NrlN/N mouse, photoreceptors survived well (B, D). The ONL had 3-4 rows of nuclei in the superior retina (B) and 5-6 rows in the inferior retina (D) at PD 30. ERG b-wave from RhoP23H/P23H mouse was very small, whereas the b-wave from Pde6brd1/rd1/NrlN/N mouse was significantly larger (E, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowhead indicates flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Sup: superior; Inf: inferior. Scale bar: 25 µm.

Figure 7.

Nrl downregulation by shRNA. 293-Nrl cells stably express mouse Nrl were used to evaluate the capability of downregulating Nrl expression by shRNA. Cells were transfected with a plasmid containing a given shRNA and harvested 72h after transfection. Western blots showed that each of the 4 shRNA successfully downregulated Nrl expression. Untransfected 293-Nrl cells and 293-Nrl cells transfected with empty vector served as controls. The levels of β actin each sample served as loading controls.

Figure 7.

Nrl downregulation by shRNA. 293-Nrl cells stably express mouse Nrl were used to evaluate the capability of downregulating Nrl expression by shRNA. Cells were transfected with a plasmid containing a given shRNA and harvested 72h after transfection. Western blots showed that each of the 4 shRNA successfully downregulated Nrl expression. Untransfected 293-Nrl cells and 293-Nrl cells transfected with empty vector served as controls. The levels of β actin each sample served as loading controls.

Figure 8.

Photoreceptor protection by shRNA in Pde6brd10/rd10 mice. The right eyes of rd10 mice were injected with AAV-shRNA-2 or AAV-shRNA-4 to the subretinal space at PD14, and the left eyes were injected with AAV-GFP as controls. Eyes were collected at PD 35. The retinas in the control eyes one row of nuclei in ONL (A, C). In the eyes injected with AAV-shRNA-2 (B) or AAV-shRNA-4 (D), the ONL had 4 rows of nuclei in the injected area (B, D). ERG b-waves from the control eyes were very small (E, F). In contrast, the b-waves from eyes injected with AAV-shRNA-2 (E) or AAV-shRNA-4 (F) was significantly larger (E, F, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowheads indicate flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Scale bar: 25 µm.

Figure 8.

Photoreceptor protection by shRNA in Pde6brd10/rd10 mice. The right eyes of rd10 mice were injected with AAV-shRNA-2 or AAV-shRNA-4 to the subretinal space at PD14, and the left eyes were injected with AAV-GFP as controls. Eyes were collected at PD 35. The retinas in the control eyes one row of nuclei in ONL (A, C). In the eyes injected with AAV-shRNA-2 (B) or AAV-shRNA-4 (D), the ONL had 4 rows of nuclei in the injected area (B, D). ERG b-waves from the control eyes were very small (E, F). In contrast, the b-waves from eyes injected with AAV-shRNA-2 (E) or AAV-shRNA-4 (F) was significantly larger (E, F, elicited by 0.398 log cd·s/m2 white flashes. Black arrowheads indicate flash onset). ONL in each retinal section was indicated by a vertical white bar (A-D). Scale bar: 25 µm.

Table 1.

Densities of S-opsin positive cells *.

Table 1.

Densities of S-opsin positive cells *.

| |

WT |

NrlN/N |

Nrl-N/-N |

| Superior |

57±11 |

100±23 |

52±4 |

| Inferior |

111±9 |

925±45 |

94±20 |

P-value

Inferior vs superior |

<0.005 |

<0.0001 |

<0.05 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).