1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal motility disorders (GIMD) are a common functional gastrointestinal disease primarily defined by gastrointestinal dysfunction, delayed gastric emptying and slow small intestinal propulsion (Valentin et al., 2015). GIMD is widely believed to be linked to multiple factors, including impaired gastrointestinal barrier and immune function, visceral hypersensitivity, impaired peristalsis, genetics and lifestyle (Singh et al., 2022). However, recent studies suggest that an imbalance in the gut microbiota is highly linked to the onset of GIMD (Barbara et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2021). Clinical studies have demonstrated that small intestinal bacterial overgrowth represents a common clinical syndrome in patients with impaired gastrointestinal motility (Toskes, 1993). Some clinical and animal studies indicated that a positive correlation between slowed gastrointestinal motility and higher levels of harmful bacteria, alongside a decrease of helpful bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Bacteroides (Cao et al., 2017; Khalif et al., 2005; Parthasarathy et al., 2016). Further, specific gut microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and bile acids (BAs) demonstrate significant associations with gastrointestinal motility (Alemi et al., 2013; Fukumoto et al., 2003). Research indicates SCFAs can accelerate colonic motility by stimulating the release of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 from intestinal endocrine L cells, thereby activating the enteric nervous system. Notably, different SCFAs exhibit distinct effects on the contraction frequency of colonic peristalsis (Hurst et al., 2014; Nakamori et al., 2021; Yan and Ajuwon, 2017). Additionally, Studies have revealed that BAs modulate gastrointestinal motility by integrating signals derived from microbiota within the enterohepatic circuit and trigger downstream signalling pathways via stimulation of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Camilleri and Vijayvargiya, 2020; Xiao et al., 2021a).

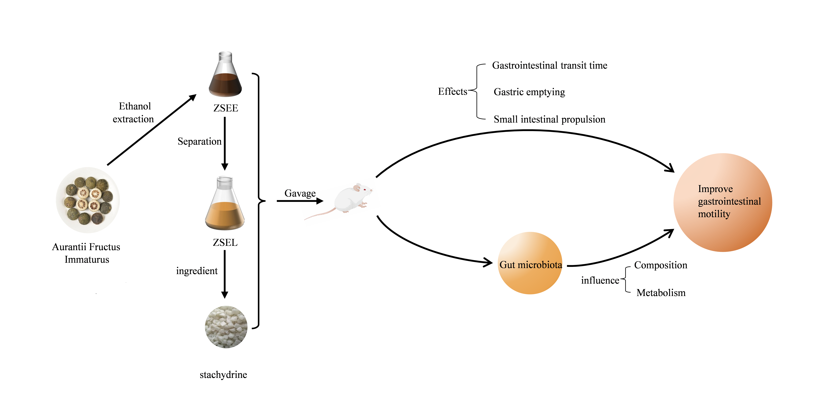

Aurantii Fructus Immaturus (AFI) is the dried young fruits of Citrus aurantium L, which is widely employed for gastrointestinal motility disorders in clinical treatment due to its excellent gastrointestinal protective effect (Sun et al., 2023). It was found that AFI enhances both tonicity and phasic contraction in small intestinal smooth muscle (Yang, 2002). Recent research has also investigated the therapeutic efficacy and mechanisms of action of AFI on GIMD (HU et al., 2017). Flavonoids in AFI are reported to be the primary effective components to promote gastrointestinal motility, which can significantly accelerate gastric emptying and small intestinal propulsion (Huang et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2017). Additionally, we found that stachydrine is one of the key bioactive ingredients identified from AFI and seems to have some cholinergic activities(Sun et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2018). Therefore, we infer that stachydrine may also be one of the bioactive ingredients of AFI to improve gastrointestinal motility. In this study, a GIMD mouse model using loperamide was utilized to explore the effects of AFI extract, its fraction and stachydrine on the physiological state and gastrointestinal motility. Subsequently, we evaluated the alterations in the composition of gut microbiota and related metabolites including SCFAs and BAs in the GIMD mice after AFI extract, its fraction and stachydrine treatment. Further, the link among the gastrointestinal motility indexes, gut microbiota and their metabolites was discussed to help exploration of the possible mechanism of AFI improving gastrointestinal motility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Chemicals and Reagents

AFI (batch no. 2010002) (Sun et al., 2023), the dried young fruits of Citrus aurantium L., was purchased from Chengdu Huichu Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China. Its pieces were extracted with 90% (v/v) ethanol solution, and the extract underwent vacuum concentration to obtain ZSEE in our laboratory. The ZSEE extract was subsequently separated by column chromatography filled with D101 macroporous adsorption resin column (Donghong Chemical Co., Ltd., Yinde, China), and the stachydrine-rich fraction was collected and concentrated under vacuum to obtain ZSEL. Stachydrine (purity, 95%) was bought from Shaanxi Ciyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shaanxi, China). Loperamide hydrochloride was obtained from TCI Shanghai Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Mosapride citrate tablet was bought from Jiangsu Haosen Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). MagPure Stool DNA Kit was supplied by Guangzhou Magen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). DNA Library Prep Kit was provided by Vazyme Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China).

The standard references of SCFAs, including propionic acid, isobutyric acid, and butyric acid (purity > 99%), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and acetic acid with a purity of 99.9% was purchased from Tan-Mo Technology Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). The analytical standards of BAs including cholic acid (CA), taurocholic acid (TCA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) with purity of more than 98% were bought from Wuhan ChemFaces Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), and deoxycholic acid (DCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), lithocholic acid (LCA), ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) with over 98% purity were bought from Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Sichuan, China). Chromatographic-grade ethanol (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Shantou, China) and methanol (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were employed for GC and HPLC-MS determination. Other analytical grade reagents were obtained from China National Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Animal Experiment

Male ICR mice, weighing 25 ± 2 g, were provided by Changsha Tianqin Biology Technology Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). These mice were maintained in an environment at 20 °C ~ 24 °C temperature, 40% ~ 60% humidity, a cycle of 12 h light/dark, and provided with unlimited access to food and water. Following a week of adaptation, the mice were separated at random into six distinct groups: (1) control group (CK) (n = 10); (2) loperamide-induced GIMD model mice group (M) (n = 10); (3) M + AFI extract ZSEE group (ZSEE) (n = 10); (4) M+ AFI extract fraction ZSEL group (ZSEL) (n = 10); (5) M + Stachydrine group (ST) (n = 9); (6) M + Mosapride citrate tablet group (P). Throughout the experimental period, the mice in the CK group were administered sterile water (10 mL/kg) by gavage. All groups except the CK group were administered 30 mg/kg bw of loperamide via gavage once daily for 14 days to develop the GIMD model. Then, the treatment of ZSEE (10 mL/kg bw, equivalent to 5.83 g dry powder per kilogram bw) and ZSEL (10 mL/kg bw, equivalent to 8.47 g dry powder per kilogram bw), ST (1000 mg/kg bw) and Mosapride solution (5 mg/kg bw) were gavaged after 1 hour of each loperamide administration for 21 days. During the animal experiment, the weight of each mouse and the total amount of food and water consumed by each cage were recorded weekly. At end of the trial, fresh fecal particles were obtained, weighed, and dried to calculate fecal moisture content. The mice were euthanised using ether anaesthesia for cervical dislocation following a 12-hour fast. The liver, spleen, and kidney were collected by using surgical scissors and weighed. All animal experiments were performed consistently with the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of Jiangxi Agricultural University, and the procedure received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Jiangxi Agricultural University with the project identification code JXAULL-2023-10-02 on 16 October 2023.

2.3. Measurement of Defecation Frequency and Gastrointestinal Transit Time

After drug administration, mice were kept individually with unlimited intake of food and defecation particles within 5 hours were recorded. After fasting for 12 hours, each mouse was intragastrically administered 0.3 mL of charcoal meal comprising 5% activated charcoal in 1.5% sodium carboxymethylcellulose, and the time at which the first black stools were observed in each mouse was recorded (Zhang et al., 2021).

2.4. Gastric Emptying and Small Intestinal Propulsion Trials

The gastric emptying rate and small intestinal propulsion rate were measured using the charcoal diet method proposed by Kimura et al. (Kimura and Sumiyoshi, 2012) and Jeon et al. (Jeon et al., 2019). The charcoal meal was prepared by mixing 5% activated carbon with 1.5% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose in purified water. After a 12-hour fast, each mouse was administered 0.3 mL of charcoal meal via gavage. All mice were euthanised after twenty-five minutes. The total and net stomach weights of mice were measured and noted. Meanwhile, the front distance of charcoal meal and the entire length of the small intestine were measured and noted. The gastric emptying and small intestinal propulsive rates were determined using the below formula:

2.5. Gut Microbiota Analysis by 16S rRNA

Total genomic DNA from fecal samples was extracted according to MagPure Stool DNA Kit. Amplification of the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed with specific primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The conditions for PCR amplification are set below: a pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 28 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s. After amplification, the final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 5 minutes to ensure DNA strand synthesis. Purified amplicons were subjected to the establishment of a sequencing library using the VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit and sequenced on Illumina PE250 platform. The raw sequencing data from sequencing underwent optimization through a series of processes including quality control, filtering, and splicing. Then sequences with a similarity level over 97% were grouped into the same operational taxonomic unit (OTU) by UCLUST software (version 7.0.1090). The taxonomy of OTUs was analyzed based on SILVA reference database. The diversity was computed using Mothur (version 1.41.0) and QIIME (version 1.9.0) respectively. The relative abundance at the level of phylum and genus among the distinct groups was compared separately. Predicted bacterial community function using PICRUSt 2 (version 2.5.0).

2.6. Quantification of Gut Microbial Metabolites SCFAs and BAs and Method Validation

The quantification method for SCFAs of gut microbial metabolites in mouse fecal samples was developed using GC. A total of 100 mg of fecal sample was thoroughly mixed with 1mL of 90% ethanol (water/ ethanol, 1:9 (v/v)) and subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was split into another centrifuge tube. The recovered supernatant was mixed together for GC analysis after this procedure was carried out three times. BAs concentration in fecal samples was detected by a validated HPLC-MS method. Briefly, 50 mg of fecal sample was combined with 1mL of methanol and then ultrasound for 20 minutes. After this, the mixture underwent centrifugation at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was moved into another separate tube. This process was carried out three times and the supernatant was mixed for HPLC-MS analysis. The quantitative analysis validation was provided in supplementary

Figure S1–S2,

Tables S1–S7, including sensitivity, linearity, precision, accuracy, and stability.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error). Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS statistics software (version 25.0). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the data conforming to the normal distribution, otherwise non-parametric test was used. A probability value p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of AFI Extract and Its Ingredient Stachydrine on the General Physiological State of Mice

The physiological state of mice serves as a crucial indicator for evaluating both therapeutic efficacy and side effects of pharmacological interventions. In our study, the effects of AFI extract, its fraction and stachydrine on gastrointestinal motility were evaluated by establishing the GIMD model mice. The schedules for animal experiments are shown in

Figure 1A. ZSEE, ZSEL and ST treatment tended to increase the body weight, daily food and water intake in mice, although no notable variance in comparison with the M group (

p >0.05) (

Figure 1B-D). Fecal moisture content, liver index, and kidney index hardly changed in all groups (

Figure 1E-G). Compared to the CK group, loperamide significantly induced an increase in the splenic index in mice (

p <0.05). However, ZSEE treatment demonstrated a decreasing trend in splenic index, though without reaching statistical significance (

p >0.05), ST intervention contributed to a notable decrease in splenic index (

p <0.05) (

Figure 1H).

3.2. AFI Extract and Its Ingredient Stachydrine Improved Gastrointestinal Motility in GIMD Mice

Recent studies have shown that some bioactive components from AFI can regulate gastrointestinal movement (Fang et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2017). Consistent with other research, we discovered that ZSEE and ZSEL can effectively improve gastrointestinal motility. Gastrointestinal transit time was significantly prolonged in GIMD mice (

p <0.05), whereas treatment with ZSEE, ZSEL and ST significantly inhibited this extension (

p <0.05) (

Figure 2A). Meanwhile, in comparison with the CK group, the M group showed a markedly decreased in defecation frequency, gastric emptying rate, and small intestinal propulsion rate (

p <0.05), and after ZSEE, ZSEL and ST treatment, these indexes were markedly increased (

p <0.05) (

Figure 2B-D). Moreover, the effects of ZSEE, ZSEL, and ST in improving gastrointestinal motility were not markedly different from the positive control drug (

p >0.05).

3.3. Effects of AFI Extract and Its Ingredient Stachydrine on the Gut Microbiota Composition in GIMD Mice

Many recent research results have demonstrated a notable correlation between altered gut microbiota composition and GIMD (Cao et al., 2017; Khalif et al., 2005). Thus, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was employed to investigate whether AFI extract and its ingredient stachydrine can modulate the gut microbiota in mice. In total, 7.9×105 optimized sequence reads, and 3.4×108 optimized base pairs (bp) were obtained after quality control filtered the low-quality data. A total of 14 phyla, 23 classes, 48 orders, 76 families, 180 genera, and 267 species were identified in all mice.

Alpha diversity values, including the Shannon and Simpson index, were compared among all experimental groups. The ZSEE group displayed a significant increase in the Shannon index than the M group (

p <0.05), whereas the ZSEL group demonstrated a not significant increasing trend (

Figure 3A). The Simpson index exhibited a notable reduction following ZSEE treatment (

p <0.05) (

Figure 3B). Therefore, ZSEE can increase the alpha diversity of gut microbiota in GIMD mice.

Microbial diversity analysis found that the gut microbiota was comprised predominantly of six phyla:

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidota,

Actinobacteriota,

Desulfobacterota,

Campylobacterota, and

Proteobacteria. Among these,

Bacteroidota and

Firmicutes were the predominant phylum, which together account for over 90% of the total abundance. Interestingly, the ZSEE, ZSEL and ST groups showed a relative increase in

Bacteroidota and

Proteobacteria than the M group. Meanwhile, the relative abundance of

Actinobacteriota decreased in both ZSEE and ZSEL groups (

Figure 3C). To further explore the gut microbial composition, we identified and analyzed differential taxa at the genus level. In comparison to the M group, the relative abundance of

Prevotellaceae_UCG-001,

Muribaculaceae_norank,

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group,

Ligilactobacillus, and

Bacteroides in the ZSEE group,

Bacteroides,

Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 and

Ligilactobacillus in the ZSEL group, and

Muribaculaceae_norank and

Bacteroides in the ST group were increased. In contrast, ZSEE, ZSEL and ST treatments reduced the relative abundance of

Turicibacter (

Figure 3D). In conclusion, administration of ZSEE, ZSEL and ST modulated the composition of gut microbiota in GIMD mice.

3.4. Difference Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Different Groups of Mice

Differential genera between experimental groups were compared using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis (

Figure 4). Two key genera were dominant in the CK group, including

Ligilactobacillus and

Lactobacillus. Ruminococcus,

Clostridia_UCG-014_norank and

Turicibacter were identified as specific genera in the M group. Furthermore, six major genera were detected in the ZSEE group, including

Ligilactobacillus,

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group,

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group,

Bacteroides,

Roseburia and

Muribaculaceae_norank. Meanwhile, four key genera were found in the ZSEL group, including

Enterococcus,

Prevotellaceae_ UCG-001,

Bacteroides and

Ligilactobacillus. Four characteristic genera were identified in the ST group, including

Parabacteroides,

Parasutterella,

Bacteroides and

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group. The relative abundance of the above-mentioned characteristic genera was also statistically analyzed. The findings indicated that ZSEE, ZSEL, and ST markedly decreased the relative abundances of

Ruminococcus,

Clostridia_UCG-014_norank and

Turicibacter, which were higher in model mice (

p <0.05). Meanwhile, ZSEE, ZSEL, and ST also markedly enhanced the relative abundance of some SCFAs-producing bacteria, such as

Bacteroides (

p <0.05) (

Figure S3 A-M in

Supplementary Materials).

3.5. AFI Extract and Its Ingredient Stachydrine Affect Predicted Microbial Metabolic Pathways in GIMD Mice

Analysis using PICRUSt 2 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) database revealed that the gene functions may be primarily categorised into six typical pathways, encompassing cellular processes, environmental information processing, genetic information processing, human diseases, metabolism, and organismal systems. The predominant metabolic pathway was metabolism in this study, which accounted for over 50% of the all pathways analyzed (

Figure 5A). Further examination of differentially expressed metabolic pathways revealed that the metabolism of cofactors and vitamins and carbohydrate metabolism in the CK group were higher than the M group (

Figure 5B). Moreover, in contrast with the M group, the ZSEE group had higher proportions in amino acid metabolism, energy metabolism and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites, and digestive system showed higher proportions in the ZSEL and ST group (

Figure 5C-E). The above findings further indicate that AFI extract and stachydrine can modulate gut microbial metabolism in GIMD mice. However, KEGG functional gene analysis is limited to predicting alterations in metabolic pathways and functional modules that gut microbiota may participate in. Further study is necessary to elucidate the specific effects of AFI extract, its fraction and stachydrine on the metabolic pathways and metabolites of gut microbiota.

3.6. AFI Extract and Its Ingredient Stachydrine Regulate Metabolites of Gut Microbiota in GIMD Mice

Researches demonstrate that many metabolites of gut microbiota can improve gastrointestinal motility, particularly SCFAs and BAs. They make significant contributions to the alleviation of GIMD through accelerating intestinal peristalsis, protecting the gastrointestinal barrier, and activating the intestinal signal pathway.(Alemi et al., 2013; Fukumoto et al., 2003). Thus, the concentrations of SCFAs and BAs in fecal samples were quantified by GC and HPLC-MS analysis, respectively. As

Figure 6A illustrates, loperamide administration induced significant decreases in acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, and butyric acid in fecal samples in contrast with the control group (

p <0.05). However, ZSEE reversed the alteration of propionic acid, and ZSEL also markedly elevated the concentrations of both acetic acid and propionic acid (

p <0.05), although it exhibited no significant influence on other SCFAs. In addition, ST also markedly raised the propionic acid concentrations (

p <0.05) and displayed a trend of increasing the concentrations of acetic acid (

p >0.05). As illustrated in

Figure 6B, the concentrations of some BAs in GIMD mice approached the level of the CK group after intervention by ZSEE, ZSEL and ST. Compared with the M group, both ZSEE and ZSEL remarkably increased the TCA concentrations, while ZSEL also reduced the levels of TCDCA and LCA (

p <0.05). Notably, ZSEE increased the level of DCA, although this increase did not reach statistical significance. Besides, TCA concentrations were markedly increased in the ST group, and DCA concentrations exhibited an upward trend as well (

p >0.05).

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated according to Spearman analysis to further investigate the relationship between the gut microbial metabolites, the differential microbial taxa at genus-level and gastrointestinal motility indexes among different groups. The correlation analysis among SCFAs, BAs and the differential gut microbiota indicated that propionic acid was adversely correlated with

Ruminococcus (

p <0.05) and positively correlated with

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and

Enterococcus (

p >0.05), butyric acid was adversely correlated with

Ruminococcus and

Clostridia_UCG-014_norank (

p >0.05), and isobutyric acid was adversely correlated with

Ruminococcus (

p <0.05), TCA shown a positive connection with

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and

Bacteroides (

p <0.05), CDCA was negatively correlated with

Ligilactobacillus (

p <0.05), LCA demonstrated a positive connection with

Muribaculaceae_norank (

p <0.05) but negatively correlated with

Enterococcus (

p >0.05). The correlation analysis between the differential gut microbiota and gastrointestinal motility indexes demonstrated that gastric emptying rate was positively associated with

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and

Bacteroides but negatively associated with

Ruminococcus (

p <0.05) (

Figure 6C). The correlation analysis between gut microbial metabolites and gastrointestinal motility indexes indicated that gastrointestinal transit time was negatively associated propionic acid, butyric acid and isobutyric acid whereas positively associated with TDCA, CDCA and TCDCA (

p <0.05), and gastric emptying rate had a positive association with TCA (

p <0.05) (

Figure 6D).

4. Discussion

GIMD is a functional gastrointestinal disease with complex pathogenesis, involving impaired gastrointestinal barrier and immune function, disordered gastrointestinal hormone secretion, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and other factors. Clinically, GIMD is primarily characterized by gastrointestinal hypomotility, delayed gastric emptying, and slowed small intestinal propulsion (Valentin et al., 2015). Current research has found that AFI can improve gastrointestinal motility, which is mainly attributed to the flavonoid components in AFI (Tan et al., 2017). In this study, AFI extract, its fraction and its ingredient stachydrine were administered to GIMD mice to analyze their effects on gastrointestinal motility and their influences on gut microbiota. The results showed that the AFI alcoholic extract and its fraction can significantly improve gastrointestinal motility through regulating gut microbial composition and metabolism. Simultaneously, stachydrine is a newly discovered bioactive ingredient of AFI extract improving gastrointestinal motility besides flavonoids, which seems to have not been reported previously.

Evidence indicates that hesperidin, a flavonoid in AFI, could improve gastrointestinal motility by increasing 5-HT4 and intracellular calcium ions, activating cAMP/PKA and p-CREB pathways (Wu, M. et al., 2020). Moreover, it has been recognized that some active components of AFI exhibit anti-inflammatory effects such as naringin in AFI reduced the expressions of pro-inflammatory mediators like cyclooxygenase-2, which may inhibit intestinal inflammation and protect the gastrointestinal barrier (Gopinath and Sudhandiran, 2012; Kaminsky et al., 2021). Our study revealed that stachydrine markedly reduced the splenic index in GIMD mice, which is possibly linked to the anti-inflammatory effect of stachydrine (Sun et al., 2023). Meanwhile, ZSEE and ZSEL and stachydrine significantly increased defecation frequency, enhanced gastric emptying and small intestine propulsion rates, while reducing gastrointestinal transit time in GIMD mice. The regulatory effects of AFI extract on gastrointestinal motility are similar to earlier research findings (Jia et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2017). The fraction ZSEL of AFI extract is known to mainly contain stachydrine and other non-flavonoid compounds, since the flavonoid components in the AFI extract were adsorbed by the chromatographic column after separation by chromatography. Our findings suggest that both ZSEL and stachydrine can significantly improve gastrointestinal motility, which indicates that stachydrine is a new bioactive ingredient in AFI extract to improve gastrointestinal motility. Current studies indicate that gut microbial dysbiosis has a close connection with the occurrence of gastrointestinal motility disorder (Singh et al., 2022). And research suggests AFI improves gastrointestinal motility mainly through regulating gastrointestinal hormone secretion, 5-HT signalling pathways, and exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties (HU et al., 2017; Wu, J. et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the impact of AFI on the gut microbiota in the alleviation of gastrointestinal motility disorders remains to be elucidated.

The gut microbiota is a new factor that has attracted widespread attention in the therapeutic management of many gastrointestinal diseases (Hills et al., 2019). There has been mounting evidence of essential involvement of gut microbiota in the development of GIMD, positioning it as a possible therapeutic target for the disease (Singh et al., 2021). Research has demonstrated that phenylethanoid glycosides, derived from the traditional Chinese medicine Houpo, can accelerate gastrointestinal motility by altering the relative abundance of certain gut microbiota, including the growth of Pseudomonas, Subdoligranulum, and Akkermansia (Xue et al., 2019). This research explores the effects of AFI extract and its ingredient stachydrine on gut microbial composition and metabolism in GIMD mice. Indeed, ZSEE treatment markedly increased gut microbial alpha diversity in GIMD mice. Meanwhile, ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine all modulated gut microbial community composition and increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidota, a phylum beneficial to gastrointestinal health. Previous findings have indicated that Bacteroidota play pivotal roles in gastrointestinal metabolism, catalyzing the utilization of nitrogenous compounds, fermentation of carbohydrates, and transformation of bile acids and sterols. Simultaneously, Bacteroidota maintains intestinal health by preventing the colonization of potential pathogenic bacteria (Jandhyala et al., 2015). Specific taxonomic identification revealed that ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine reversed alterations in multiple bacterial taxa at the genus level in GIMD mice. Among these bacteria, several are considered beneficial bacteria, including Muribaculaceae_norank, Bacteroides, Ligilactobacillus, Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and Prevotellaceae_UCG_001, whose relative abundance increased after both ZSEE and ZSEL treatments. Particularly, it has been demonstrated that these bacteria are linked to the production of some important gut microbial metabolites. Among them, Bacteroides participates in the production of acetic acid and propionic acid (Louis et al., 2014); Muribaculaceae_norank is associated with bile acid metabolism (Yang et al., 2022); Prevotellaceae_UCG_001, Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and Ligilactobacillus may be involved in the synthesis of SCFAs (Yang et al., 2023). Furthermore, stachydrine significantly increased the relative abundance of Parasutterella. Studies suggested that Parasutterella may contribute to the management of BA metabolism (Ju et al., 2019). However, the relative abundances of Turicibacter, Ruminococcus and Clostridia_UCG-014_norank were reduced after ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine administration in GIMD mice. Research indicates that Turicibacter and Ruminococcus may be correlated with the occurrence of intestinal inflammation (Schirmer et al., 2019; Vestergaard et al., 2024). Meanwhile, Clostridia_UCG-014 has been found to be significantly positively linked to impaired intestinal barrier function (Leibovitzh et al., 2022). A clinical study revealed that patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) exhibit a remarkable upward in Ruminococcus abundance and a marked decrease in Bacteroides in contrast to healthy individuals (Rajilić-Stojanović et al., 2011). Therefore, we propose that ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine may indirectly improve gastrointestinal motility by reducing the relative abundance of inflammation-associated gut microbiota while increasing SCFA-producing bacterial taxa.

Certain gut microbial metabolites, including SCFAs and BAs, are considered vital to the regulation of gastrointestinal motility. We analyzed alterations in the concentrations of SCFAs and BAs in mice, and further investigated their correlations with differential gut microbiota. Acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid are the primary SCFAs produced in the intestine through the gut microbiota’s fermentation of dietary fiber (Cong et al., 2022). This study revealed markedly reduced concentrations of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and isobutyric acid in GIMD mice. Conversely, propionic acid concentrations were markedly increased in the ZSEE group, while acetic and propionic acid concentrations exhibited notable rises in the ZSEL and ST groups. SCFAs have been proven to regulate intestinal motility. For instance, one study demonstrates that the injection of a solution containing acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid into the proximal colon of rats significantly promoted colonic propulsive motility (Fukumoto et al., 2003). Previous evidence indicates that SCFAs accelerate colonic peristalsis by stimulating the secretion of GLP-1 from enteroendocrine L cells, which activates the enteric nervous system. And distinct SCFAs exert varying influences on the contraction frequency of colonic motility. (Hurst et al., 2014; Nakamori et al., 2021). Moreover, SCFAs can also indirectly regulate intestinal endocrine function and peristalsis by stimulating ECs to promote 5-HT expression in the colon (Reigstad et al., 2015). Correlation analysis revealed a negative correlation between propionic acid and Ruminococcus. Currently, it has been confirmed that the synthesis of SCFAs is regulated by a variety of gut microbiota. Acetic acid biosynthesis pathways are widely distributed across microbial communities, exemplified by gut bacteria synthesising acetate via the acetyl-CoA pathway. Propionic acid is primarily produced by the lactate pathway of Firmicutes and the succinate pathway of Bacteroidota (Louis et al., 2014). Thus, ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine may impact the synthesis of SCFAs by regulating gut microbiota to improve gastrointestinal motility.

BAs are known to be important regulators of intestinal motility (Bajor et al., 2010). Evidence indicates that stool samples from IBS-C patients display significantly reduced levels of unconjugated primary BAs, whereas patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome exhibit markedly increased concentrations of unconjugated primary BAs (Mars et al., 2020). This disturbance of BA metabolism is possibly associated with changes in gut microbiota during different disease states. These determine the composition and size of the BAs pool via deconjugation, dehydroxylation, and oxidation of primary BAs (Bunnett, 2014; Xiao et al., 2021b). We found that ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine restored the content of some bile acids in GIMD mice to a level close to the healthy mice. Noteworthy, ZSEE and stachydrine displayed a trend toward increasing DCA levels, and ZSEL significantly reduced levels of TCDCA and LCA. Previous studies have found that DCA can stimulate 5-HT and calcitonin gene-related peptide release by activating TGR5 receptors in ECs and primary afferent neurons, hence enhancing colonic peristaltic contractions (Bunnett, 2014). Furthermore, DCA has been demonstrated to inhibit endotoxin-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) in macrophages. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα can increase intestinal permeability via activation of the myosin light chain kinase gene, hence promoting intestinal inflammatory processes by allowing luminal antigen penetration (Al-Sadi et al., 2016; Greve et al., 1989). Meanwhile, TCA has been found to have a potent anti-inflammatory effect, which may be mediated through upregulation of FXR signalling (Ge et al., 2023). Correlation analysis revealed that TCA had a positive association with Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and Bacteroides and LCA was positively associated with Muribaculaceae_norank. Research demonstrates that gut microbiota and BAs exhibit a bidirectional regulatory connection: the gut microbiota modulates the size and composition of the BAs pool, whereas BAs significantly affect gut microbial diversity and metabolic function (Collins et al., 2023). Based on the above, ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine may regulate BAs metabolism through gut microbiota to improve gastrointestinal motility.

The findings from this study may offer scientific evidence concerning the mechanism of AFI regulating gastrointestinal motility and establish a theoretical basis for the development of AFI-related products. It is worthy of note that the ZSEE and ZSEL exhibit certain distinctions in regulating gut microbiota and their metabolites, which may be caused by differences in their components and dosage. Furthermore, the effect of stachydrine in AFI on improving gastrointestinal motility is also an important finding. However, these findings need to be further validated by subsequent in vivo and in vitro experiments, such as fecal microbiota transplantation and in vitro fermentation of gut microbiota. This study mainly focuses on changes in gut microbiota and their metabolites from fecal samples. Future studies should encompass additional gastrointestinal segments to comprehensively explore the regulatory mechanisms of AFI on gastrointestinal motility.

5. Conclusions

The research demonstrated that the administration of ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine markedly improved the symptoms of GIMD mice, including a reduction in gastrointestinal transit time and improvement in gastric emptying rate and small intestinal propulsive rate, comparable to the positive control drug. Furthermore, ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine could modulate the composition of gut microbiota. It was discovered that ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine had beneficial effects, including decreasing the populations of pro-inflammatory bacteria such as Turicibacter, Clostridia_UCG-014_norank and Ruminococcus, while raising the abundance of beneficial bacteria like Bacteroides, Eubacterium_fissicatena_group and Muribaculaceae_norank. Meanwhile, ZSEE, ZSEL and stachydrine could also regulate the metabolism of SCFAs and BAs. Our research further demonstrates the ability of AFI extract, its fraction and its ingredient stachydrine to improve gastrointestinal motility. Therefore, we propose that AFI extract, its fraction and its ingredient stachydrine may indirectly improve gastrointestinal motility through altering gut microbial composition and metabolism to restore gastrointestinal function. However, their mechanisms of action remain unclear, which requires further research. It is noteworthy that the link between gut microbiota and its metabolites offers the scientific basis for GIMD management and thus should be further explored in subsequent studies. Exploring the therapeutic mechanism of AFI on GIMD through a perspective of gut microbiota might offer a novel direction in AFI research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Youmei Huang: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, visualization. Jianing Hu: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. Shixiang Li: Methodology, Software, Resources. Liaolongyan Luo: Investigation, Methodology. Jianping Zhu: Investigation, Methodology. Jinzhou Zhu: Investigation, visualization. Ganjun Yuan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82360691).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| AFI |

Aurantii Fructus Immaturus |

| GIMD |

gastrointestinal motility disorder |

| 5-HT |

5-hydroxytryptamine |

| SCFAs |

short-chain fatty acids |

| BAs |

bile acids |

| FXR |

farnesoid X receptor |

| CA |

cholic acid |

| TCA |

taurocholic acid |

| CDCA |

chenodeoxycholic acid |

| TUDCA |

tauroursodeoxycholic acid |

| DCA |

deoxycholic acid |

| LCA |

lithocholic acid |

| TDCA |

taurodeoxycholic acid |

| TCDCA |

taurochenodeoxycholic acid |

| UDCA |

ursodeoxycholic acid |

| GC |

Gas chromatography |

| HPLC-MS |

High performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometric |

| OTU |

operational taxonomic unit |

| FID |

flame ionization detector |

| ECs |

enterochromaffin cells |

| IBS-C |

constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome |

References

- Al-Sadi, R., Guo, S., Ye, D., Rawat, M., Ma, T.Y., 2016. TNF-α Modulation of Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability Is Mediated by NIK/IKK-α Axis Activation of the Canonical NF-κB Pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 186(5), 1151-1165. [CrossRef]

- Alemi, F., Poole, D.P., Chiu, J., Schoonjans, K., Cattaruzza, F., Grider, J.R., Bunnett, N.W., Corvera, C.U., 2013. The receptor TGR5 mediates the prokinetic actions of intestinal bile acids and is required for normal defecation in mice. Gastroenterology 144(1), 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Bajor, A., Gillberg, P.G., Abrahamsson, H., 2010. Bile acids: short and long term effects in the intestine. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 45(6), 645-664. [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G., Feinle-Bisset, C., Ghoshal, U.C., Quigley, E.M., Santos, J., Vanner, S., Vergnolle, N., Zoetendal, E.G., 2016. The Intestinal Microenvironment and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology. [CrossRef]

- Bunnett, N.W., 2014. Neuro-humoral signalling by bile acids and the TGR5 receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Physiol. 592(14), 2943-2950. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M., Vijayvargiya, P., 2020. The Role of Bile Acids in Chronic Diarrhea. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115(10), 1596-1603. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., Liu, X., An, Y., Zhou, G., Liu, Y., Xu, M., Dong, W., Wang, S., Yan, F., Jiang, K., Wang, B., 2017. Dysbiosis contributes to chronic constipation development via regulation of serotonin transporter in the intestine. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 10322. [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L., Stine, J.G., Bisanz, J.E., Okafor, C.D., Patterson, A.D., 2023. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21(4), 236-247. [CrossRef]

- Cong, J., Zhou, P., Zhang, R., 2022. Intestinal Microbiota-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids in Host Health and Disease. Nutrients 14(9). [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.S., Shan, D.M., Liu, J.W., Xu, W., Li, C.L., Wu, H.Z., Ji, G., 2009. Effect of constituents from Fructus Aurantii Immaturus and Radix Paeoniae Alba on gastrointestinal movement. Planta Med. 75(1), 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, S., Tatewaki, M., Yamada, T., Fujimiya, M., Mantyh, C., Voss, M., Eubanks, S., Harris, M., Pappas, T.N., Takahashi, T., 2003. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate colonic transit via intraluminal 5-HT release in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 284(5), R1269-1276. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X., Huang, S., Ren, C., Zhao, L., 2023. Taurocholic Acid and Glycocholic Acid Inhibit Inflammation and Activate Farnesoid X Receptor Expression in LPS-Stimulated Zebrafish and Macrophages. Molecules 28(5). [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K., Sudhandiran, G., 2012. Naringin modulates oxidative stress and inflammation in 3-nitropropionic acid-induced neurodegeneration through the activation of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 signalling pathway. Neuroscience 227, 134-143. [CrossRef]

- Greve, J.W., Gouma, D.J., Buurman, W.A., 1989. Bile acids inhibit endotoxin-induced release of tumor necrosis factor by monocytes: an in vitro study. Hepatology 10(4), 454-458. [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.D., Jr., Pontefract, B.A., Mishcon, H.R., Black, C.A., Sutton, S.C., Theberge, C.R., 2019. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 11(7). [CrossRef]

- HU, Y., Chen, H., Song, Y., Tan, S., Luo, X., Yang, W., 2017. Study on the mechanism of Aurantii Fructus Immaturus and its main active ingredients in promoting gastrointestinal motility of model rats with spleen deficiency. China Pharmacy, 1747-1750.

- Huang, A., Chi, Y., Zeng, Y., Lu, L., 2012. Influence of fructus aurantii immaturus flavonoids on gastrointestinal motility in rats with functional dyspepsia. Traditional Chinese Drug Research & Clinical Pharmacology 23(06), 612-615.

- Hurst, N.R., Kendig, D.M., Murthy, K.S., Grider, J.R., 2014. The short chain fatty acids, butyrate and propionate, have differential effects on the motility of the guinea pig colon. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 26(11), 1586-1596. [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., Nageshwar Reddy, D., 2015. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 21(29), 8787-8803. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.J., Lee, J.S., Cho, Y.R., Lee, S.B., Kim, W.Y., Roh, S.S., Joung, J.Y., Lee, H.D., Moon, S.O., Cho, J.H., Son, C.G., 2019. Banha-sasim-tang improves gastrointestinal function in loperamide-induced functional dyspepsia mouse model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 238, 111834. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q., Li, L., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Jiang, K., Yang, K., Cong, J., Cai, G., Ling, J., 2022. Hesperidin promotes gastric motility in rats with functional dyspepsia by regulating Drp1-mediated ICC mitophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 945624. [CrossRef]

- Ju, T., Kong, J.Y., Stothard, P., Willing, B.P., 2019. Defining the role of Parasutterella, a previously uncharacterized member of the core gut microbiota. ISME J. 13(6), 1520-1534. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, L.W., Al-Sadi, R., Ma, T.Y., 2021. IL-1β and the Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier. Front. Immunol. 12, 767456. [CrossRef]

- Khalif, I.L., Quigley, E.M., Konovitch, E.A., Maximova, I.D., 2005. Alterations in the colonic flora and intestinal permeability and evidence of immune activation in chronic constipation. Dig. Liver Dis. 37(11), 838-849. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y., Sumiyoshi, M., 2012. Effects of an Atractylodes lancea rhizome extract and a volatile component β-eudesmol on gastrointestinal motility in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 141(1), 530-536. [CrossRef]

- Leibovitzh, H., Lee, S.H., Xue, M., Raygoza Garay, J.A., Hernandez-Rocha, C., Madsen, K.L., Meddings, J.B., Guttman, D.S., Espin-Garcia, O., Smith, M.I., Goethel, A., Griffiths, A.M., Moayyedi, P., Steinhart, A.H., Panaccione, R., Huynh, H.Q., Jacobson, K., Aumais, G., Mack, D.R., Abreu, M.T., Bernstein, C.N., Marshall, J.K., Turner, D., Xu, W., Turpin, W., Croitoru, K., 2022. Altered Gut Microbiome Composition and Function Are Associated With Gut Barrier Dysfunction in Healthy Relatives of Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 163(5), 1364-1376.e1310. [CrossRef]

- Louis, P., Hold, G.L., Flint, H.J., 2014. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12(10), 661-672. [CrossRef]

- Mars, R.A.T., Yang, Y., Ward, T., Houtti, M., Priya, S., Lekatz, H.R., Tang, X., Sun, Z., Kalari, K.R., Korem, T., Bhattarai, Y., Zheng, T., Bar, N., Frost, G., Johnson, A.J., van Treuren, W., Han, S., Ordog, T., Grover, M., Sonnenburg, J., D’Amato, M., Camilleri, M., Elinav, E., Segal, E., Blekhman, R., Farrugia, G., Swann, J.R., Knights, D., Kashyap, P.C., 2020. Longitudinal Multi-omics Reveals Subset-Specific Mechanisms Underlying Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Cell 182(6), 1460-1473.e1417. [CrossRef]

- Nakamori, H., Iida, K., Hashitani, H., 2021. Mechanisms underlying the prokinetic effects of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 in the rat proximal colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 321(6), G617-g627. [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, G., Chen, J., Chen, X., Chia, N., O’Connor, H.M., Wolf, P.G., Gaskins, H.R., Bharucha, A.E., 2016. Relationship Between Microbiota of the Colonic Mucosa vs Feces and Symptoms, Colonic Transit, and Methane Production in Female Patients With Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 150(2), 367-379.e361. [CrossRef]

- Rajilić-Stojanović, M., Biagi, E., Heilig, H.G., Kajander, K., Kekkonen, R.A., Tims, S., de Vos, W.M., 2011. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 141(5), 1792-1801. [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, C.S., Salmonson, C.E., Rainey, J.F., 3rd, Szurszewski, J.H., Linden, D.R., Sonnenburg, J.L., Farrugia, G., Kashyap, P.C., 2015. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 29(4), 1395-1403. [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, M., Garner, A., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R.J., 2019. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17(8), 497-511. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Zogg, H., Ghoshal, U.C., Ro, S., 2022. Current Treatment Options and Therapeutic Insights for Gastrointestinal Dysmotility and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 808195. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Zogg, H., Wei, L., Bartlett, A., Ghoshal, U.C., Rajender, S., Ro, S., 2021. Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Dysmotility and Metabolic Disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 27(1), 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Xia, X., Yuan, G., Zhang, T., Deng, B., Feng, X., Wang, Q., 2023. Stachydrine, a Bioactive Equilibrist for Synephrine, Identified from Four Citrus Chinese Herbs. Molecules 28(9). [CrossRef]

- Tan, W., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, T., Zhou, Q., Wang, X., 2017. Anti-coagulative and gastrointestinal motility regulative activities of Fructus Aurantii Immaturus and its effective fractions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 90, 244-252. [CrossRef]

- Toskes, P.P., 1993. Bacterial overgrowth of the gastrointestinal tract. Adv. Intern. Med. 38, 387-407.

- Valentin, N., Acosta, A., Camilleri, M., 2015. Early investigational therapeutics for gastrointestinal motility disorders: from animal studies to Phase II trials. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 24(6), 769-779. [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, M.V., Allin, K.H., Eriksen, C., Zakerska-Banaszak, O., Arasaradnam, R.P., Alam, M.T., Kristiansen, K., Brix, S., Jess, T., 2024. Gut microbiota signatures in inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J 12(1), 22-33. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L., Singh, R., Ro, S., Ghoshal, U.C., 2021. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH open : an open access journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 5(9), 976-987. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Huang, G., Li, Y., Li, X., 2020. Flavonoids from Aurantii Fructus Immaturus and Aurantii Fructus: promising phytomedicines for the treatment of liver diseases. Chin. Med. 15, 89. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Li, Y., Gu, Y., 2020. Hesperidin Improves Colonic Motility in Loeramide-Induced Constipation Rat Model via 5-Hydroxytryptamine 4R/cAMP Signaling Pathway. Digestion 101(6), 692-705. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L., Liu, Q., Luo, M., Xiong, L., 2021a. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 729346. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L., Liu, Q., Luo, M., Xiong, L., 2021b. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 729346. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Luo, Z., Lai, B., Xiao, L., Wang, N., 2018. Stachydrine protects eNOS uncoupling and ameliorates endothelial dysfunction induced by homocysteine. Mol. Med. 24(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z., Wu, C., Wei, J., Xian, M., Wang, T., Yang, B., Chen, M., 2019. An orally administered magnoloside A ameliorates functional dyspepsia by modulating brain-gut peptides and gut microbiota. Life Sci. 233, 116749. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Ajuwon, K.M., 2017. Butyrate modifies intestinal barrier function in IPEC-J2 cells through a selective upregulation of tight junction proteins and activation of the Akt signaling pathway. PLoS One 12(6), e0179586. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Huang, S., Lin, Z., Chen, H., Xu, C., Lin, Y., Sun, H., Huang, F., Lin, D., Guo, F., 2022. Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera alleviate hypercholesterolemia via modulating the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Food Funct. 13(23), 12194-12207. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Gao, Y.-a., Wang, J.-q., Zheng, N., 2023. Research progress on the functions of short chain fatty acid.

- Yang, Y., 2002. The effects of Zhishi and Qingpi on the motivity of smooth muscle. J. Northwest Norm. Univ.(Nat. Sci.) 38, 114-117.

- Zhang, X., Zheng, J., Jiang, N., Sun, G., Bao, X., Kong, M., Cheng, X., Lin, A., Liu, H., 2021. Modulation of gut microbiota and intestinal metabolites by lactulose improves loperamide-induced constipation in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 158, 105676. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).