1. Introduction

The discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA marks the dawn of modern biology. DNA comaprises two strands going in opposite directions, which are connected by A/T and G/C base pairs [

1]. This structure, especially the exclusive A/T and G/C base-pair formation, allowed Professor Crick to propose the famous Central Dogma, which explained how DNA is duplicated and how genetic information dictates the amino acid sequence of proteins and, thus, their phenotype [

1,

2]. Later experiments further supported this theory [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. DNA polymerase binds to one of the DNA strands and uses it as a template to synthesize the complementary strand. DNA polymerase selects and extends a base that pairs with the corresponding base on the template DNA. For protein synthesis, messenger RNA (mRNA) is first produced similarly from one of the DNA strands by RNA polymerase. Subsequently, the ribosome binds the mRNA, selects a transfer RNA (tRNA) that forms base pairs with three consecutive nucleotides on the mRNA (codon/anticodon interactions), and polymerizes the amino acid carried by the tRNA. Base pair formation is thus essential for fundamental biological reactions comprising replication, transcription, and translation.

Base pair formation is also involved in other critical biological processes, such as the regulation of translation by small-interfering RNA (siRNA), genomic maintenance and meiosis via homologous recombination, and disruption of viral DNA in bacteria by the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Furthermore, base pairing is applied in medicine and biotechnology, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), siRNA-like drugs, CRISPR–Cas9-based gene editing, and DNA microdevices [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. PCR is based on the binding of primers complementary to parts of the target gene. Moreover, nucleic acid drugs that bind to a target mRNA via sequence complementarity and inhibit its translation into the target protein are currently in development. Homologous recombination- and CRISPR–Cas9-based gene editing involve base-pairing to target the editing site. Similarly, DNA nanomachines are constructed by the specific organization of several DNA fragments through base pair formation. For all of these applications, efficient and correct interaction between two complementary nucleotides is essential. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of recognition of the complementary base (or nucleotide sequence) is crucial.

The selection of complementary bases is frequently considered to be based on hydrogen bond formation between complementary bases (Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds). However, there is no experimental evidence to support this claim. On the contrary, several studies have demonstrated that DNA polymerase can select complementary bases in the absence of hydrogen bond formation, thereby suggesting the presence of other factors [

21,

22,

23]. This idea is supported even in the absence of any protein owing to variation in the thermal stability of double-stranded oligonucleotides, depending on the type of mismatch [

24].

Overall, this review summarizes biological reactions and applications involving base-pair formation and discusses the mechanism of complementary base (or sequence) recognition, to further the development of effective applications.

2. Biological Roles of Base Pair Formation

Base pairing is essential for replication, transcription, and translation. In addition to these fundamental biological reactions, several other biological processes involve base pairing between two complementary sequences, as described below.

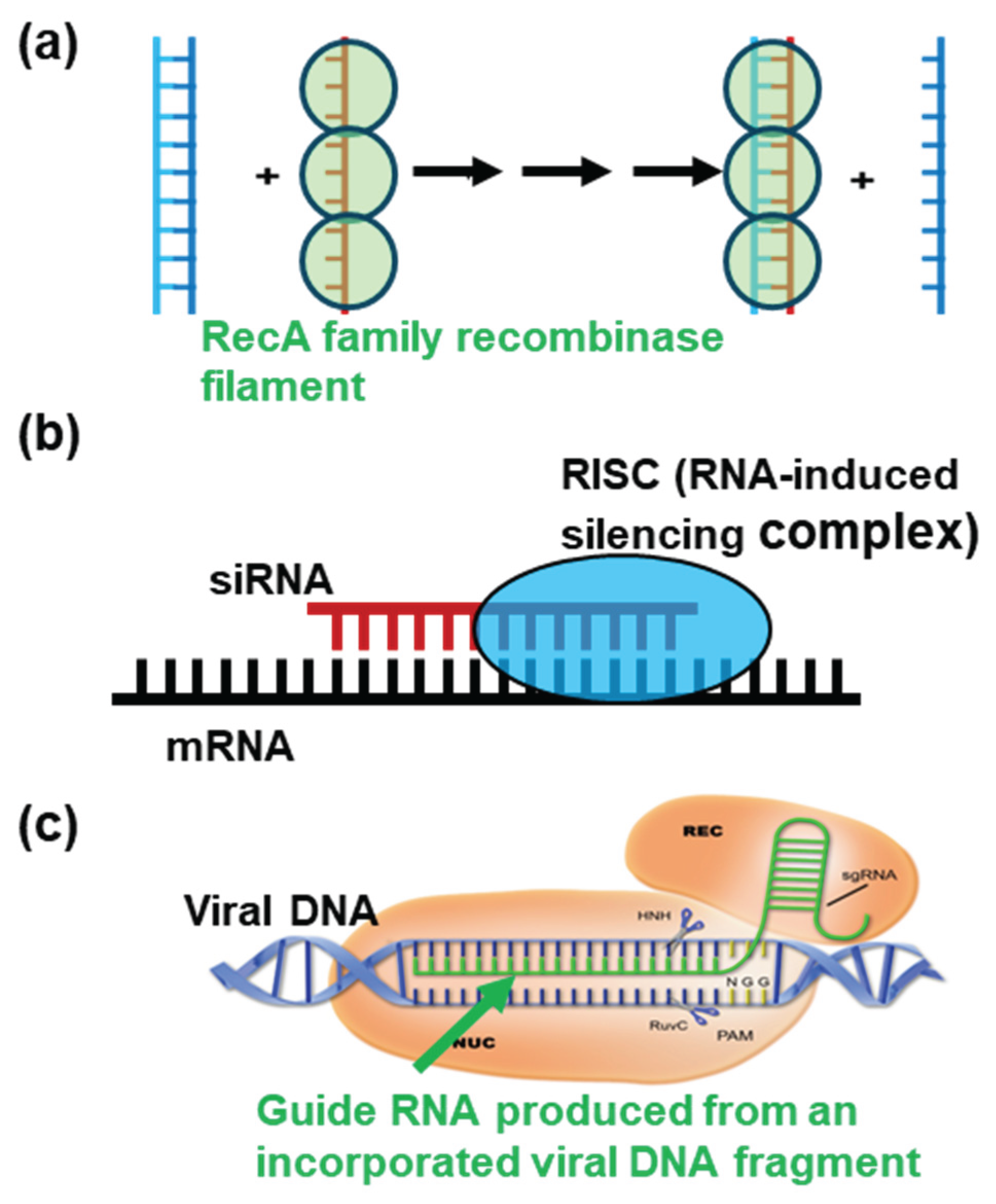

2.1. Homologous Recombination for DNA Repair and Meiosis

Homologous recombination consists of strand exchange between two DNA molecules with identical nucleotide sequences. The reaction is essential for repairing stalled replication forks and double-strand breaks [

11,

12]. It also plays a role in the formation of chromosome pairs during meiosis [

13]. The recognition of sequence homology between two DNA molecules can be achieved through base-pairing between their complementary strands (

Figure 1A).

2.2. Regulation of Translation by siRNA and microRNA

siRNA is a non-coding RNA of 20–24 bases that silences the expression of specific genes [

9,

10]. siRNA is produced as a double-stranded RNA. After entering a cell, the siRNA molecule is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and processed into a single-stranded RNA. This complex subsequently binds to the target mRNA by forming base pairs via sequence complementarity and cleaves it (

Figure 1B). This results in the repression of translation of the target genes and the production of the target protein. Consequently, this system is widely used in biological research and biomedical applications [

16,

17,

18].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, highly conserved non-coding RNA molecules that—like siRNAs—regulate the translation of specific genes [

25,

26]. miRNAs are produced endogenously from miRNA, unlike siRNAs, and are processed by the Microprocessor complex (Drosha/DGCR8) as well as Dicer. Thereafter, one strand (guide strand) of a 20 to 24-nucleotide-long miRNA duplex becomes part of the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) and binds to the target mRNAs via sequence complementarity. The complex represses protein production through mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. Furthermore, the level of complementarity between the miRNA and mRNA target determines which silencing mechanism will be employed.

2.3. Disruption of Virus DNA by the CRISPR–Cas9 System

CRISPR–Cas9 system is a bacterial defense system that functions against bacteriophage (virus) infection. Typically, bacteria and archaea conserve DNA segments of bacteriophages that have previously infected them [

14]. The guide RNA in CRISPR–Cas9 is produced from these DNA segments and incorporated into the Cas9 nuclease. With the help of the guide RNA, Cas9 detects and destroys DNA from related bacteriophages during subsequent infections (

Figure 1C). This system is used explicitly in gene editing [

19,

27,

28].

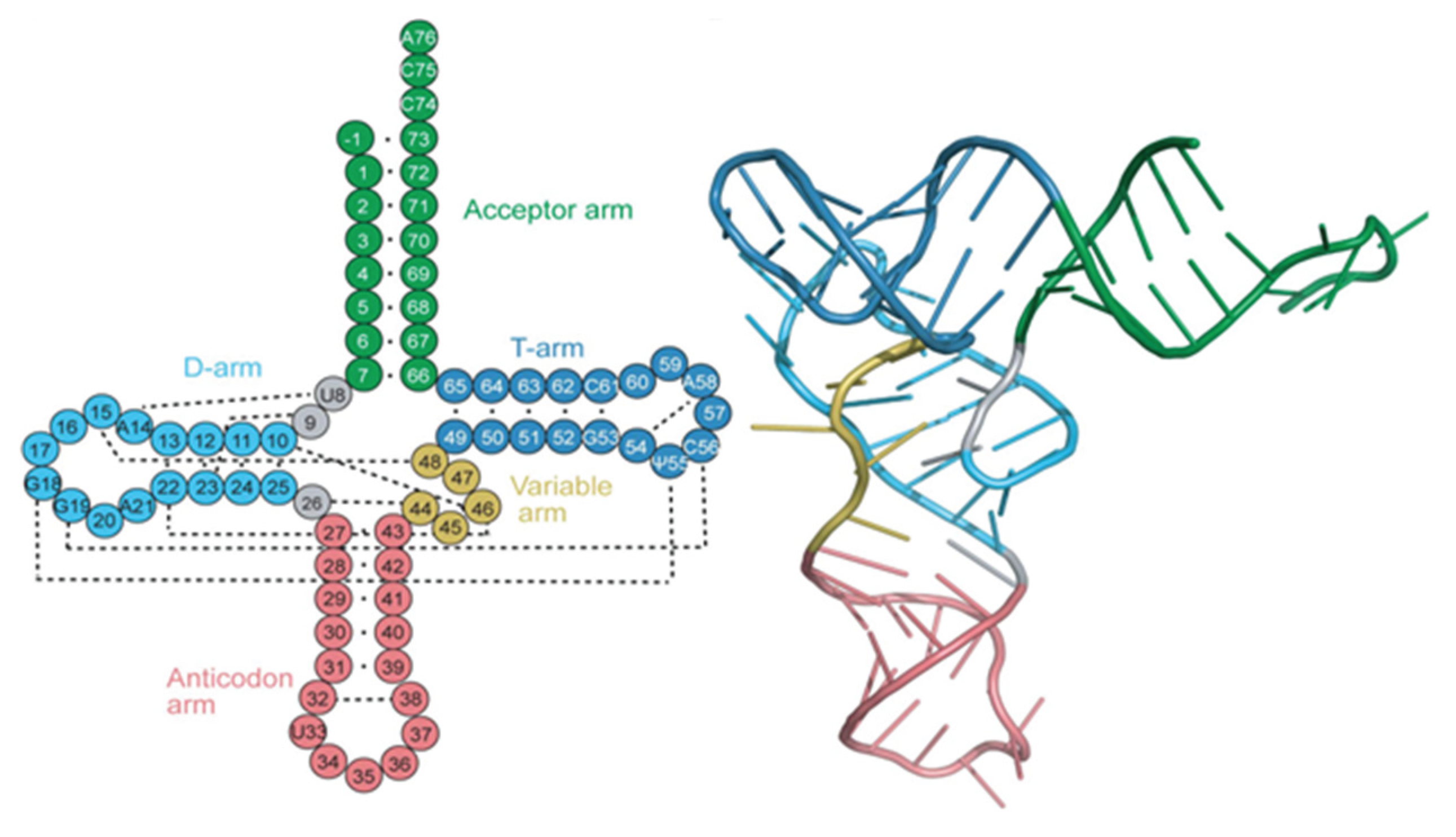

2.4. Structure of Non-Coding RNA

Some RNAs—such as tRNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and spliceosomal RNA (snRNA)—function in various biological processes without being translated into proteins. These RNAs form specific three-dimensional structures to perform their functions [

29,

30]. The RNA structure is supported by the formation of partial double-helical structures (stems) by base pairing within the RNA molecule (

Figure 2).

2.5. Size and Recognition Accuracy of Sequence Complementarity in the Reactions

A specific enzyme (or protein complex) catalyzes each of these biological reactions involving base pairing. Clarifying the mechanisms by which these enzymes recognize complementary bases or sequences is essential to understanding the high fidelity of these reactions and the maintenance of life. DNA polymerase makes only one mistake over 107 events. Interestingly, we observe that DNA polymerase does not evenly incorporate incorrect bases [

31]; some mismatches occur more frequently than others. Moreover, CRISPR–Cas9 and siRNA recognize 20-base-pair complementarity, indicating that these reactions discard DNA or RNA fragments with one mismatch over 20 bases. Consequently, these features cannot account for the recognition of target sequences solely through hydrogen bonding.

The difference in the size of the complementary sequences suggests that reaction mechanisms can vary from reaction to reaction. DNA and RNA polymerases recognize only one complementary base at each step, whereas the ribosome recognizes three base pairs. Similarly, siRNA reactions and CRISPR–Cas9 require more than 20 nucleotide complementarities, whereas miRNA reactions accept partial sequence complementarity. Homologous recombination recombinases potentially recognize approximately six nucleotide pairs to initiate the reaction [

32,

33]. The recognition accuracy also varies with the reaction. Wherein replication appears to be more accurate than transcription [

34,

35]. Moreover, the replication fidelity varies among DNA polymerases [

36].

3. Biotechnological Applications Using Base Pair Formation

3.1. Antisense- and siRNA-Based Gene Regulation and Drugs

Antisense and siRNA technologies use oligonucleotides complementary to the target mRNA, thereby regulating the production of the corresponding protein. This strategy is used in biological research to examine the cellular function of a gene by observing biological effects resulting from reduced expression of the target gene [

37]. It has led to the development of oligonucleotide-based drugs for treating infectious diseases, genetic disorders, as well as cancer by reducing the production of disease-associated proteins [

16,

17,

18,

38]. In addition to binding to the mRNA target in the cytoplasm, antisense RNA can enter the nucleus and bind to DNA or pre-mRNA, thereby affecting transcription and splicing of the target mRNA. siRNA functions only in the cytoplasm and regulates translation. These systems allow rapid drug development without requiring target characterization and complex chemical synthesis of drug candidates. The technique can also easily adapt to the drug resistance caused by mutations of the target.

Although the therapy demonstrates high selectivity, off-target effects persist. Accordingly, a partial sequence of the complementary off-target mRNA can be repressed by siRNA and antisense therapies, consequently causing secondary effects. Due to the extensive size of the human genome, several similar sequences exist [

39]. The presence of many off-targets reduces the drug's availability to the target and compromises the treatment's efficacy. Therefore, resolving this issue is essential to developing better treatment methods [

40].

3.2. Homologous Recombination- and CRISPR–Cas9-Assisted Gene Editing

Homologous recombination is used for gene editing [

41]. The system can insert a desired DNA segment into a defined position or replace a target segment with another one using sequence homology between the target segment and the corrector oligonucleotide. Gene editing is used to cure genetic diseases or to create genetically modified animals and crops. To increase homologous recombination efficacy, a double-strand break is induced at a desired position using CRISPR–Cas9 or other systems. The Cas9 enzyme cuts genomic DNA at a specific DNA sequence guided by the guide RNA, resulting in a double-stranded break.

However, homologous recombination occurs infrequently and is ineffective for treating human somatic cells. Consequently, a novel approach using only the CRISPR–Cas9 system was developed. In this system, a nucleotide-modifying enzyme—such as a deaminase—is fused to CRISPR–Cas9 and selectively "corrects" the point mutation [

26,

27].

3.3. DNA Hybridization

DNA hybridization is a simple molecular biology technique that involves the association of two complementary single strands of DNA (or RNA) via the specific base-pairing rules governing A/T (U) and G/C. The ability to detect specific DNA sequences has made hybridization a powerful technique with a wide range of applications, especially prior to the development of sequencing techniques.

This technique uses a labeled oligonucleotide to facilitate the detection of a DNA fragment containing the target segment among many pieces or the localization of the target segment within a long chromosomal DNA molecule [

42,

43,

44]. It is used to identify homologous genes across various organisms and to trace their evolution. Additionally, it can be used to detect the genetic material of pathogens—such as viruses and bacteria—in patient samples. This technique is beneficial for identifying genetic mutations, diagnosing inherited diseases, and determining a person's carrier status for specific medical conditions. It is also used for DNA fingerprinting to identify individuals based on their unique DNA profile.

3.4. PCR for Amplification of a Specific DNA Segment (or Fragment)

PCR is a technique used to rapidly obtain numerous copies of a specific segment of DNA from a small sample. This process, called DNA amplification, uses DNA polymerase enzymes to create new DNA strands, thereby yielding sufficient material for detailed study, analysis, or diagnosis [

15,

45]. Because it requires a primer that binds to a template DNA strand for DNA polymerase to initiate replication, this technique can amplify a specific segment by selecting appropriate primers. PCR tests are used for medical diagnostics, forensic analysis and genetic testing, along with the detection of infectious agents such as viruses.

3.5. DNA Nanodevices

DNA nanodevices are artificial nanoscale machines constructed by the designed association of several DNA fragments via sequence complementarity. The association creates a specific 3-D structure [

46] that can be altered by changes in the environment (pH or ion concentration) and other factors. The device can be used as a drug delivery system, a sensor, and a motor in therapeutics [

47,

48,

49]. The system is also exploited for computation (DNA computers) [

50].

3.6. Aptamers (Chemical Antibodies)

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA that are 20–80 nucleotide long. They form a specific structure through internal interactions and bind a particular target. Double-helical stems formed within the molecules—as in tRNA—support their structures [

49]. Some aptamers are developed as drugs or drug delivery systems to treat diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other forms of eye disease, cancer, and infectious diseases [

51,

52,

53].

3.7. Problems with Applications

The primary concern with these applications is the off-target effect. Owing to the enormous size of the human genome, several sequences may share similarities with the target sequence. Off-target binding reduces the amount of siRNA available to the target, thereby reducing the overall efficacy. Additionally, binding to off-targets inhibits the translation of unexpected genes and provokes unintended adverse effects. Especially in CRISPR–Cas9 applications, irreversible genome modification can occur, resulting in permanent damage. Consequently, understanding the mechanism of complementary sequence recognition and improving the design of complementary sequences are essential for the further development of these technologies [

54,

55,

56]

4. Molecular Mechanism of Complementary Base Recognition

Despite the importance of base pairing in several essential biological processes as well as in the development of biotechnological applications, the mechanism for recognizing complementary bases (or sequences) remains unknown.

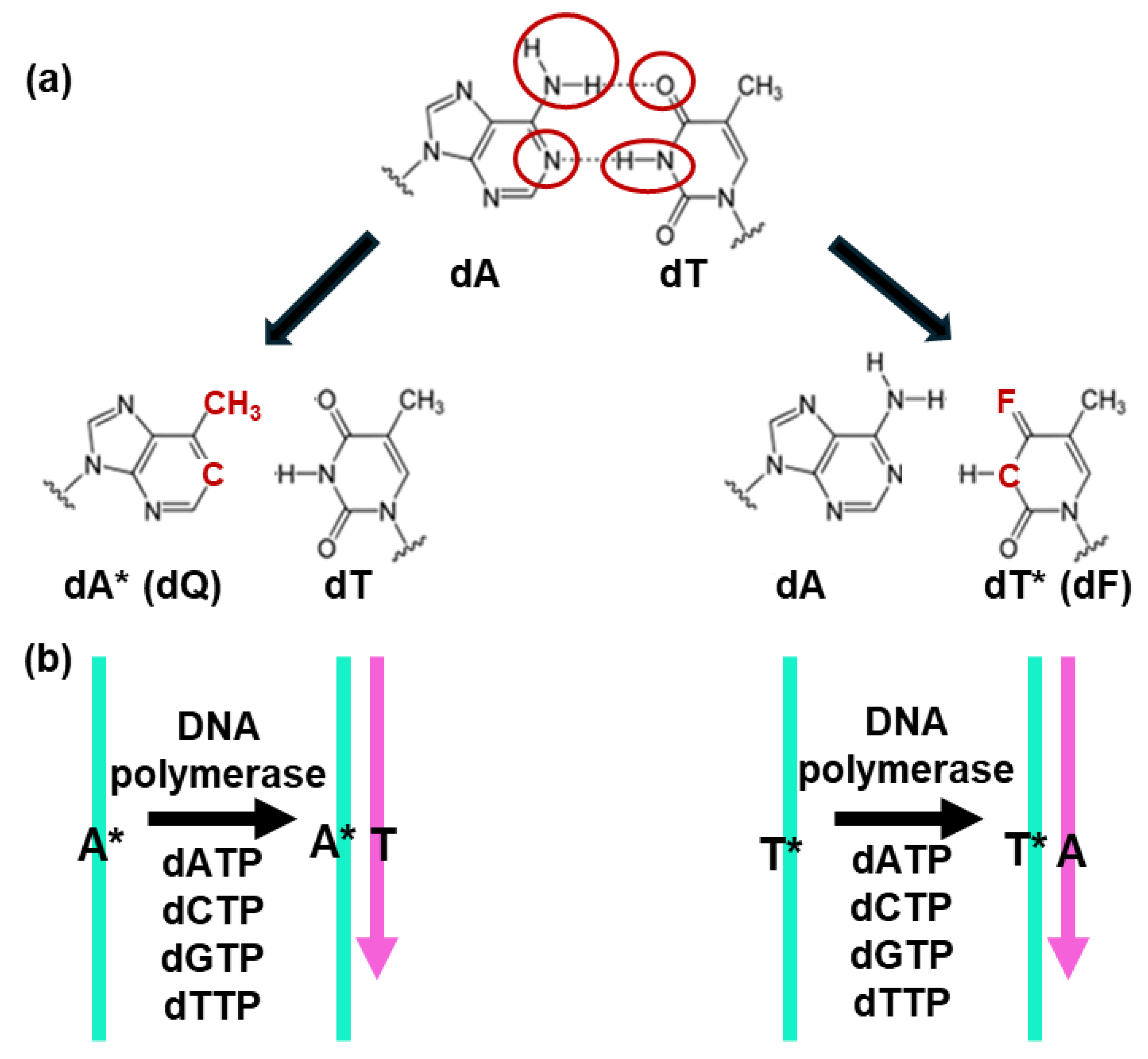

4.1. Existence of Factors Other than the Hydrogen Bond

The formation of the Watson-Crick hydrogen bond is frequently considered as a primary element in the selection of the complementary nucleobase (or nucleotide sequence). Base pairs are usually held by hydrogen bonds, which suggests that hydrogen bond formation ensures the specificity of A/T and G/C base pairing. These hydrogen bonds exist in both DNA and RNA. However, there is no experimental evidence supporting the idea that complementary bases are selected through hydrogen bond formation.

The experimental examination of whether DNA polymerase selects complementary bases solely through hydrogen bonding was addressed 40 years after the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA. Kool et al. used modified nucleobases that cannot form hydrogen bonds with any nucleobases during the replication [

22,

24]. They replaced the hydrophilic groups of T and A bases, which form hydrogen bonds, with nonpolar chemical groups (

Figure 3A). These modifications disrupt hydrogen bond formation with any base. Subsequently, these modified bases were incorporated into a template DNA strand and replicated with a DNA polymerase in vitro. It was observed that DNA polymerase incorporated A opposite the modified T and T opposite the modified A, despite the absence of hydrogen bonding (

Figure 3B). Consequently, the DNA polymerase selects the "correct" bases without forming hydrogen bonds. The results indicated the presence of another factor (or factors) for the complementary base section.

The same study also performed replication using a non-modified DNA template, but with modified A and T trinucleotides. The modified T was revealed to be incorporated opposite A, whereas the modified A was incorporated opposite T [

22,

57]. Additionally, the DNA polymerase selected "correct" complementary bases in vivo [

58]. Therefore, it was elucidated that DNA polymerase does not require hydrogen bond formation to select complementary bases.

Notably, even in the absence of any protein, the double-stranded oligonucleotide—in which the modified A pairs with T—presents higher thermal stability than other oligonucleotides in which the modified A pairs with another base [

57]. Another factor besides hydrogen bonds is the formation and stability of double-stranded DNA.

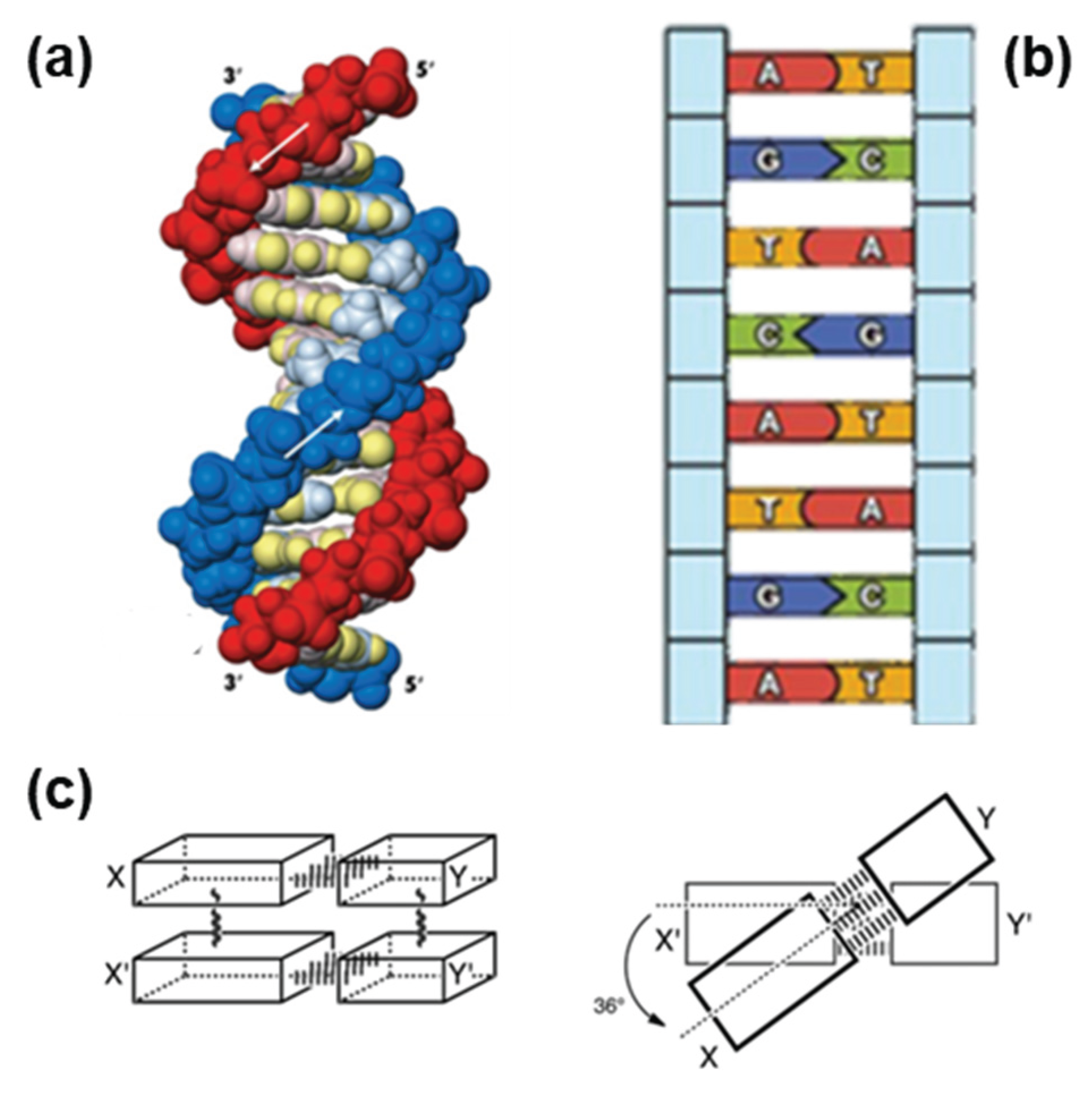

4.2. Geometry of Base Pairs

The most probable decisive factor for the selection is the geometry of the bases and base pairs. The modifications of the bases that disrupted hydrogen bond formation did not affect their shape or size. Furthermore, the size of the base pair is essential for the regular arrangement of the two strands in the DNA (

Figure 4). A/T and G/C base pairs each consist of one purine and one pyrimidine, and thus their size (the distance between the points attached to each DNA backbone) is similar: 12.0 nm for A/T and 11.9 nm for G/C pair [

58]. This size similarity ensures a regular, smooth phosphodiester backbone in B-form DNA, regardless of its nucleotide sequence (

Figure 4).

The smooth and regular helical structure of the phosphodiester backbone is also related to ordered base-pair stacking (

Figure 4). Base pairs are hydrophobic and firmly stack on top of each other, thereby stabilizing dsDNA. Interestingly, base pairs regularly rotate around the DNA filament axis (

Figure 4C). This regularity and the independence of nucleotide sequence in the base pair stacking are due to the similar orientation of bases relative to the phosphodiester backbone. The angle between a base and ribose is ≈55 degrees for any base [

59]. Collectively, the geometry and organization of base pairs (base stacking) are essential for the formation of regular double-stranded DNA and potentially contribute to its stability.

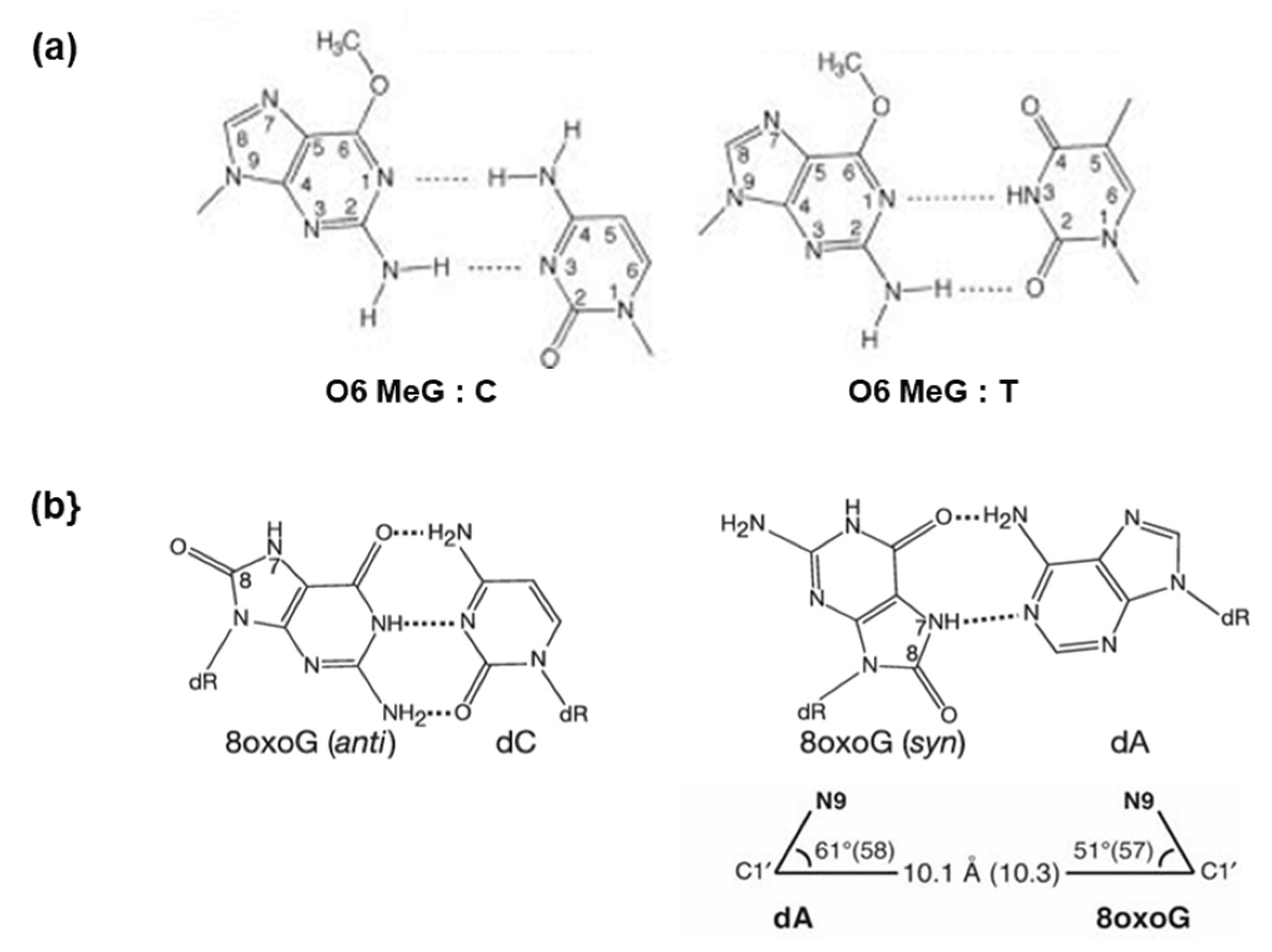

4.3. The Geometry of Base Pairs Explains the Mutagenic Effects of O6-methyl G and 8-oxo G

The importance of base-pair geometry in replication is further supported by observations of nucleotide misincorporation by DNA polymerase opposite mutagenic bases. O6 methyl G, as well as 8-oxo G are produced naturally by the modification of G and are both highly mutagenic. DNA polymerase selects A opposite O6 methyl G and T opposite 8-oxo-G instead of C. This results in mutations that can lead to cancer [

59]. Structural analysis revealed that O6-methyl G can form a pair with C via two hydrogen bonds (

Figure 5A). However, the geometry of the base pair differs from a normal G/C pair in size and orientation relative to the backbone. In contrast, the geometry of the O6 methyl G/A pair is similar to that of the regular base pairs. In vitro analysis indicated that DNA polymerase extends replication past the O6-methylated G/A pair, but disrupts replication past the O6-methylated G/C pair.

In the case of 8-oxo-G, it could form a pair with C, along with three hydrogen bonds (

Figure 5B). However, a potential steric clash between the C8 carbonyl oxygen and the O4' of the sugar moiety may prevent this base pair [

60]. 8-oxo-G can also create a base pair with T and maintain the regular base-pair geometry, although the base is in a sin configuration. This observation explains the mutagenic effect of 8-oxo-G. Thus, the base-pair geometry is an essential factor in the selection of complementary bases by DNA polymerase and in maintaining the regular structure of DNA.

4.4. Artificial Base Pairs Without Hydrogen Bond Formation

Hirata and colleagues developed an artificial base pair to enlarge the variation of aptamers [

61]. Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind to specific targets. However, the diversity of aptamers is limited, as there are only four nucleobases with similar shapes and chemical properties. More variation in bases, especially hydrophobic bases, can expand the potential of aptamers. One advantage of the aptamer strategy is the ability to select optimal aptamers via SELEX. In this approach, potential oligonucleotides are selected from a vast pool and amplified by replication for another round of selection. To use this selection method, newly designed nucleobases should be replicated by DNA polymerase with specifically pairing bases. A novel base pair design is required for this purpose. Hirata and colleagues designed hydrophobic base pairs in which two bases are complementary in shape and form a base pair that respects the regular base-pair geometry. They succeeded in obtaining such pairs that were correctly replicated in vitro and in vivo. Hydrogen bond formation does not appear to be required for base pairing during replication, underscoring the role of base geometry in the selection of "complementary" bases by DNA polymerase. NMR analysis showed that an oligonucleotide containing this artificial base pair forms a standard B-form structure [

62].

4.5. Role of Base Stacking

The above observations that hydrogen bonding is not required for the selection of complementary bases do not imply that hydrogen bonding plays no role under "normal" situations. To test the role of hydrogen bond formation in selection and confirm the importance of base-pair geometry in the recognition of complementary bases, selection of complementary bases in the absence of geometry selection should be examined. Weakening base stacking could affect the selection by geometry. In the absence of strong stacking interactions, base pairs can be accommodated more freely in DNA, and selection by geometry will be weakened.

Hydrophobic interactions mainly support base stacking. Since hydrophobic interactions occur between nonpolar (hydrophobic) molecules in a polar (hydrophilic) environment, base stacking can be weakened by either attaching hydrophilic groups to the molecules or using a less hydrophilic solvent. Nordén et al. successfully weakened base stacking using a semi-hydrophobic cosolvent, PEG [

63]. PEG destabilizes double-stranded DNA and facilitates DNA strand exchange. They claimed that weakening base stacking does not eliminate the specificity of base pair formation [

64]. Both hydrogen bonding and base stacking are involved in the selection of complementary bases.

5. Discussion

The studies indicate the interplay between hydrogen bond formation and base-pair geometry in the recognition of complementary bases or sequences. Further studies are required to clarify the exact mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

5.1. Kinetic Analyses

It is now crucial to know whether the recognition of complementary bases begins with hydrogen-bond formation or with base-pair geometry selection. More precise kinetic studies will be required to elucidate this question. Both interactions are short-distance and directional. The action of enzymes is to bring two bases close enough and in a good direction. Recombinases that catalyze DNA strand exchange bind two DNA molecules in their filament and orient DNA bases in an appropriate direction [

64]. Structural analyses of reaction intermediates will shed light on the reaction mechanism [

65].

5.2. Existence of Multiple Mechanisms

The recognition mechanism can vary from one reaction to another. The recognition accuracy and size of complementary sequences differ depending on the enzyme that catalyzes the reaction. Analysis of recognition mechanisms for each reaction may be required. However, some common aspects in the recognition mechanism should exist. The association of two complementary oligonucleotides occurs naturally without any protein. Furthermore, pairing of the modified A with T promotes more stable double-stranded DNA, and DNA polymerase selects T opposite the modified A. This coincidence suggests that DNA polymerase uses the characteristic nature of DNA stability to select complementary bases

5.3. Limitations of Perturbing Approaches

The roles of hydrogen bond formation and base stacking in base pairing have primarily been analyzed by disrupting hydrogen bonds and weakening base stacking interactions [Kool; Nordén], which poses certain limitations. The disruption of hydrogen-bond formation by replacing hydrophilic nucleobase groups with hydrophobic ones enhances hydrophobic interactions. This base modification strengthens base stacking and emphasizes selection by geometry. Weakening base stacking with PEG reduces the activity of water molecules, thereby enhancing hydrogen bonding by diminishing competition with them. Therefore, the selection by hydrogen bond formation may be exaggerated. It is necessary to quantitatively estimate the contribution of each force to the selection of complementary bases under natural conditions.

5.4. Examining the Strand Separation Step

Several biological reactions involve strand separation of double-stranded DNA prior to the formation of new base pairs. For instance, RNA polymerase promotes strand separation for transcription. Similarly, homologous recombination and CRISPR–Cas9 involve strand separation of double-stranded DNA to interact with the primary bound single-stranded DNA or guide RNA. Moreover, DNA strands can associate with wrong fragments or sites due to partial complementarity during hybridization or other reactions. Separation from such situations is crucial for the formation of the correct double-stranded structure.

In the absence of any proteins, strand separation occurs at high temperatures, thereby suggesting a requirement for significant energy. However, in biological systems, strand separation occurs under mild conditions with the help of enzymes. The mechanism of strand separation must be analyzed in more depth. Notably, semi-hydrophobic solvent PEG facilitates strand separation by weakening base stacking [

63]. Hydrophobic residues are present in the DNA-binding sites of proteins. These residues may create hydrophobic environments and weaken base stacking, thereby facilitating strand separation.

6. Conclusions

The recognition of complementary bases and sequences is involved in many fundamental biological processes and biotechnological applications. Understanding the mechanism is required for efficient applications. Various studies indicate that the selection of complementary bases and sequences involves both Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding and base-pair geometry.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

M.T. acknowledges Professor Masayuki Oda (Kyoto Prefectural University) and Professor Hiroshi Iwasaki (Institute of Science Tokyo) for discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Watson, J.; Crick, F. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. On protein synthesis. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 1958, 12, 138–163.

- Meselson, M.; Stahl, F. The replication of DNA in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1958, 44, 671–682.

- Cairns, J. The bacterial chromosome and its manner of replication as seen by autoradiography. J Mol Biol 1961, 6, 208–213.

- Lehman, I.R.; Bessman, M.J; Simms, E.S.; Kornberg, A. Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. I. Preparation of substrates and partial purification of an enzyme from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 1958, 233, 163–170.

- Weiss, S.B.; Gladstone, L.A. A mammalian system for the incorporation of cytidine triphosphate into ribonucleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 81, 4118-4119. [CrossRef]

- Chapeville, F.; Lipmann, F.; Ehrenstein, G.V.; Weisblum, B.; Ray Jr, W.J.; Benzer, S. On the role of soluble ribonucleic acid in coding for amino acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1962, 48, 1086–1092.

- Matthaei, H.J.; Jones, O.W.; Martin, R.G.; Nirenberg, M.W. Characteristics and Composition of RNA Coding Units. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1962, 48, 666–677. [CrossRef]

- Fire, A,; Xu, S. Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806-811. [CrossRef]

- Dana, H.; Chalbatani, G.M,; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Karimloo, R.; Rezaiean, O.; Moradzadeh, A.; Mehmandoost, N.; Moazzen, F.; Mazraeh, A.; Marmari, V.; Ebrahimi, M.; Rashno, M.M.; Abadi, S.J.; Gharagouzlo, E. Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions of siRNA. Int J Biomed Sci. 2017, 13, 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.D.; Shah, S.S.; Heyer, W.D. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2018, 6, 10524-10535. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Schirmeisen, K.; Lambert, S.A. The multifaceted functions of homologous recombination in dealing with replication-associated DNA damages. DNA Repair, 2023, 129, 103548. [CrossRef]

- Székvölgyi, L.; Nicolas, A. From meiosis to postmeiotic events: Homologous recombination is obligatory but flexible. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 571-589. [CrossRef]

- Mojica, F.J.; Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005, 60, 174-82. [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, K.; Ohtsuka, E.; Kleppe, R.; Molineux, I.; Khorana, H.G. Studies on polynucleotides. XCVI. Repair replications of short synthetic DNA's as catalyzed by DNA polymerases. J Mol Biol. 1971, 56 (2): 341–61. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ga, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. et al. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutic applications against viruses: principles, potential, and challenges. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 88. [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Gatti, P.; Papoian, T. Safety of antisense oligonucleotide and siRNA-based therapeutics, Drug Discovery Today, 2017, 22, 823-833. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., Ga, Y.J., Kim, S.H., et al. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutic applications against viruses: principles, potential, and challenges. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 88. [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.B.; Platt, R.J.; Zhang, F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nature Medicine. 2015, 21, 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q., Yang, L., & Chao, J. Recent Advances in Dynamic DNA Nanodevice. Chemistry, 2023, 5, 1781-1803. [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Ren, R.X.; Kool, E.T. A thymidine triphosphate shape analog lacking Watson–Crick pairing ability is replicated with high sequence selectivity Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997, 94, 10506-10511. [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.C.; Kool, E. T. Efficient replication between non-hydrogen-bonded nucleoside shape analogs. Nature Structural Biology, 1998, 5, 950-954. [CrossRef]

- Kool, E.T.; Sintim, H.O. The Difluorotoluene Debate — A Decade Later. Chemical Communications 2006, 38, 3665-75.

- Tikhomirova, A.; Beletskaya, I.V.; Chalikian, T.V. Stability of DNA Duplexes Containing GG, CC, AA, and TT Mismatches Biochemistry 2006, 45, 10563-10571. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. 2018, 173, 20–51. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018, 9, 402. [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Packer, M.S. Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature, 2016, 533, 420-424. [CrossRef]

- Li, T. ; Yang, Y. ; Qi, H. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 36. [CrossRef]

- Biela, A.; Hammermeister, A.; Kaczmarczyk, I.; Walczak, M.; Koziej, L.; Lin, T.; Glatt, S. The diverse structural modes of tRNA binding and recognition. J Biol Chem, 2023, 299, 104966. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, A. L.; Enguita, F.J.; Leitão, A.L.; Enguita, F.J. (2025). The Unpaved Road of Non-Coding RNA Structure–Function Relationships: Current Knowledge, Available Methodologies, and Future Trends. Non-Coding RNA 2025, 11, 20. [CrossRef]

- Sloane, D.L.; Goodman, M.F.; Echols, H. The fidelity of base selection by the polymerase subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 6465-75. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Beach, A.; Li, K.; Haber, J. Rad51-mediated double-strand break repair and mismatch correction of divergent substrates. Nature 2017, 453, 489–494.

- Takahashi, M. RecA kinetically selects homologous DNA by testing a five- or six-nucleotide matching sequence and deforming the second DNA. Quarterly Rev. Biophys. 2018, 51, e11. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, T.A.; Bebenek, K. DNA replication fidelity. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000; 69,497-529.

- Imashimizu, M.; Oshima, T.; Lubkowska, L.; Kashlev, M. Direct assessment of transcription fidelity by high-resolution RNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41, 9090–9104. [CrossRef]

- Fijalkowska, I.J.; Schaaper, R.M.; Jonczyk, P. DNA replication fidelity in Escherichia coli: a multi-DNA polymerase affair. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012, 36,1105-21. [CrossRef]

- Han, H. RNA Interference to Knock Down Gene Expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2018; 1706:293-302. [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, M.C. Possibilities and limitations of antisense oligonucleotide therapies for the treatment of monogenic disorders. Communications Medicine, 2024, 4, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ratilainen, T.; Lincoln, P.; Nordén, B. A simple model for gene targeting. Biophys J. 2001, 81, 2876-85. [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, J.; Meister, G. SiRNA Specificity: RNAi Mechanisms and Strategies to Reduce Off-Target Effects. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2021, 11, 526455. [CrossRef]

- Hoshijima, K.; Jurynec, M.J.; Grunwald, D.J. Precise genome editing by homologous recombination. Methods Cell Biol. 2016, 135:121-47.

- Hoheisel, J.D. Application of hybridization techniques to genome mapping and sequencing. Trends in Genetics, 1994, 10, 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Lao, A.I.K.; Su, X.; Aung, K.M.M. SPR study of DNA hybridization with DNA and PNA probes under stringent conditions. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2009, 24,1717-1722. [CrossRef]

- Furst, A.L.; Klass, S.H.; Francis, M.B. DNA Hybridization to Control Cellular Interactions. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 2019, 44, 342-350. [CrossRef]

- Bej, A.K.; Mahbubani, M.H.; Atlas, R.M. Amplification of Nucleic Acids by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Other Methods and their Applications. Critl Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 1991, 26, 301–334. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Yang, L.; Chao, J. Recent Advances in Dynamic DNA Nanodevice. Chemistry, 2023, 5, 1781-1803. [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Zhu, X.; Feng, C. DNA Nanodevice-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 1855. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Kim, S.; Wang, C.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, S.; Lee, S.; Jo, S.; Kim, T. Understanding nucleic acid sensing and its therapeutic applications. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2023, 55, 2320-2331. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.B.; Seeman, N.C. A precisely controlled DNA biped walking device Nano Letters 2004, 4, 1203–1207.

- Parker, J. Computing with DNA. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 7-10.

- Shraim, A.S.; Abdel Majeed, B.A.; Al-Binni, M.A.; Hunaiti, A. Therapeutic Potential of Aptamer-Protein Interactions. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2022, 5, 1211-1227. [CrossRef]

- Nimjee, S.M.; White, R.R.; Becker, R.C.; Sullenger, B.A. Aptamers as Therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017, 57:61-79.

- Yang, W., Ran, C., Lian, X., Wang, Z., Du, Z., Bing, T., Zhang, Y., & Tan, W. Aptamer-based targeted drug delivery and disease therapy in preclinical and clinical applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2025, 226, 115680. [CrossRef]

- Ali Zaidi, S.S.; Fatima, F., Ali Zaidi, S.A.; Zhou, D.; Deng, W.; Liu, S. Engineering siRNA therapeutics: challenges and strategies. J Nanobiotechnol 2023, 21, 381. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ma, X.; Gao, F; Guo, Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1143157. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yu, X.; Hu, S.; Yu, J. A Brief Review on the Mechanisms of miRNA Regulation. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 2009, 7, 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Ren, R.X.; Kool, E.T. A thymidine triphosphate shape analog lacking Watson–Crick pairing ability is replicated with high sequence selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997, 94,10506-10511. [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.C.; Henderson, P.T.; Helquist, S.A.; Morales, J.C.; Essigmann, J.M.; Kool, E.T. High-fidelity in vivo replication of DNA base shape mimics without Watson–Crick hydrogen bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4469-4473. [CrossRef]

- Chavarria, D.; Ramos-Serrano, A.; Hirao, I.; Berdis, A.J. Exploring the roles of nucleobase desolvation and shape complementarity during the misreplication of O6-methylguanine. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 412, 325-339. [CrossRef]

- Hsu. G.W.; Ober, M.; Carell, T.; Beese, L.S. Error-prone replication of oxidatively damaged DNA by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Nature 2004, 431, 217-221. [CrossRef]

- Yamashige, R.; Kimoto, M.; Takezawa, Y.; Sato, A.; Mitsui, T.; Yokoyama, S.; Hirao, I. Highly specific unnatural base pair systems as a third base pair for PCR amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 2793–2806. [CrossRef]

- Guckian, K.M.; Krugh, T.R.; Kool, E.T., Solution structure of a nonpolar, non-hydrogen-bonded base pair surrogate in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6841–6847. [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Sosa, R.P.; Mårtensson, A.K.F.; Jiang, K.; Tong, A.; Dorfman, K.D.; Takahashi, M.; Lincoln. P.; Bustamante, C.J.; Westerlund, F.; Nordén, B. Hydrophobic catalysis and a potential biological role of DNA unstacking induced by environment effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17169-17174. [CrossRef]

- Nordén, B.; Brown, T.; Feng, B. Mismatch detection in homologous strand exchange amplified by hydrophobic effects. Biopolymers, 2021, 112, e23426. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Ito, K.; Iwasaki, H.; Nordén, B. Linear dichroism reveals the perpendicular orientation of DNA bases in the RecA and Rad51 recombinase filaments: a possible mechanism for the strand exchange reaction. Chirality 2024, 36, e23664. [CrossRef]

- Freudenthal, B.D.; Beard, W.A.; Wilson, S.H. Structures of dNTP intermediate states during DNA polymerase active site assembly. Structure, 2012, 20, 1829-1837. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Murayama, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Iwasaki, H. Two three-strand intermediates are processed during Rad51-driven DNA strand exchange. Nature Struct. & Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 29-36. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).